www.revportcardiol.org

Revista

Portuguesa

de

Cardiologia

Portuguese

Journal

of

Cardiology

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Cardiovascular

risk

in

HIV-infected

individuals:

A

comparison

of

three

risk

prediction

algorithms

Sara

Policarpo

a,b,∗,

Teresa

Rodrigues

c,

Ana

Catarina

Moreira

d,

Emília

Valadas

eaServic¸odeDietéticaeNutric¸ão,HospitaldeSantaMaria,Lisboa,Portugal

bUniversidadedeLisboa,FaculdadedeMedicina,LaboratóriodeNutric¸ão,Lisboa,Portugal cUniversidadedeLisboa,FaculdadedeMedicina,LaboratóriodeBiomatemática,Lisboa,Portugal

dEscolaSuperiordeTecnologiadaSaúdedeLisboa,InstitutoPolitécnicodeLisboa,PortugalH&TRC---CentrodeInvestigac¸ão

emSaúdeeTecnologia,Portugal

eUniversidadedeLisboa,FaculdadedeMedicina,ClinicaUniversitáriadeDoenc¸asInfecciosas,Lisboa,Portugal

Received27December2017;accepted21October2018 Availableonline12September2019

KEYWORDS Cardiovascularrisk; Metabolicsyndrome; HIV/Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; Portugal Abstract

Introduction:Cardiovascular(CV)riskisknowntobeincreasedinHIV-infectedindividuals.Our aimwastoassessCVriskinHIV-infectedadults.

Methods:CVriskwasestimatedforeachpatientusingthreedifferentriskalgorithms:SCORE, theFraminghamriskscore(FRS),andDAD.Patientswereclassifiedasatlow,moderateorhigh CVrisk.Clinicalandanthropometricdatawerecollected.

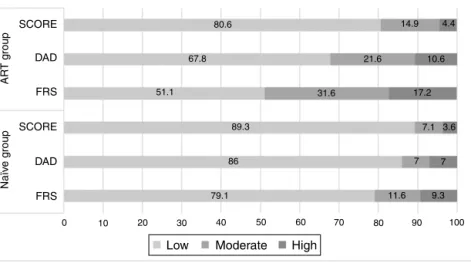

Results:Weincluded571HIV-infectedindividuals,mostlymale(67.1%;n=383).Patientswere dividedintotwogroupsaccordingtoantiretroviraltherapy(ART):naïve(7.5%;n=43)orunder ART(92.5%;n=528).ThemeantimesinceHIVdiagnosiswas6.7±6.5yearsinthenaivegroupand 13.3±6.1yearsintheARTgroup.Metabolicsyndrome(MS)wasidentifiedin33.9%(n=179)and 16.3%(n=7)ofparticipantsintheARTandnaïvegroups,respectively.MSwasassociatedwithART (OR=2.7;p=0.018).Triglycerides≥150mg/dl(OR=13.643,p<0.001)wasoneofthemajorfactors contributingtoMS.Overall,highCVriskwasfoundin4.4%(n=23)ofpatientswhentheSCORE toolwasused,in20.5%(n=117)usingtheFRS,andin10.3%(n=59)usingtheDADscore.The observed agreement between the FRS and SCORE was 55.4% (k=0.183, p<0.001), between the FRS andDAD 70.5% (k=0.465,p<0.001), and between SCORE and DAD 72.3% (k=0.347, p<0.001).

Conclusion: On thebasisofthethree algorithms, wedetected ahigh rateofhighCV risk, particularlyinpatientsunderART.TheFRSwasthealgorithmthatclassifiedmostpatientsin thehighCVriskcategory(20.5%).Inaddition,ahighprevalenceofMSwasidentifiedinthis patientgroup.

©2019PublishedbyElsevierEspa˜na,S.L.U.onbehalfofSociedadePortuguesadeCardiologia.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:sara.policarpo@chln.min-saude.pt(S.Policarpo).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.repc.2019.08.002

0870-2551/©2019PublishedbyElsevierEspa˜na,S.L.U.onbehalfofSociedadePortuguesadeCardiologia.

This is an open access article under CC BY-NC-ND license. (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

This is an open access article under CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Riscodedoenc¸a cardiovascular;

Síndromemetabólica;

VIH/SIDA; Portugal

RiscocardiovasculareminfetadosporVIH:comparac¸ãodetrêsferramentasde avaliac¸ão

Resumo

Introduc¸ão:Oriscocardiovascular(RCV)podeestaraumentadoemindivíduoscominfec¸ãopor VírusImunodeficiênciaHumana(VIH).OobjetivodestetrabalhofoiavaliaroRCVemadultos infetadosporVIH.

Métodos: ORCV foiestimadoutilizando trêsalgoritmosdiferentes,Score,FraminghamRisk Score(FRSs-CVD)eDAD;osparticipantesforamclassificadosapresentandoRCVbaixo,moderado ouelevado.Recolheram-sedadosclínicoseantropométricos.

Resultados: Incluíram-se571indivíduos,maioritariamentedogéneromasculino(67,1%;n=383). Dividiram-seosparticipantesem doisgrupos,come semterapêutica antirretroviral(cTAR): naïve(7,5%;n=43)versuscTAR(92,5%;n=528).Otempomédiodesdeodiagnósticodainfec¸ão porVIHfoi6,7±6,5anosnogruponaïvee13,3±6,1anosnogrupocART.Asíndromemetabólica (SM)foiidentificadaem33,9%(n=179)eem16,3%(n=7)dosparticipantes,respetivamenteno grupocARTenogruponaïve.Verificou-seumRCVelevadoem4,4%(n=23)dosparticipantes,com recursoàferramentaScore,em20,5%(n=117)utilizandoaFRSseem10,3%dosparticipantes (n=59)utilizando aferramenta DAD.A concordânciaobservadaentreFRSs eScorefoi55,4% (k=0,183;p<0,001), entreFRSs e DAD70,5% (k=0,465;p<0,001)e entreScore eDAD 72,3% (k=0,347;p<0,001).

Conclusão:Comrecursoaosalgoritmosutilizados,identificou-seumapresenc¸asignificativade elevado RCV, sendo a ferramenta FRSs-CVD a que classificou mais indivíduos na categoria deRCVelevado(20,5%),esimultaneamenteverificou-seumaprevalênciaelevadadeSM. ©2019PublicadoporElsevierEspa˜na,S.L.U.emnomedeSociedadePortuguesadeCardiologia. Este ´e um artigo Open Access sobuma licenc¸a CC BY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

InEuropean countries in recent years,cardiovascular

dis-ease(CVD)hasbeenidentifiedasamajorcauseofmortality

inhumanimmunodeficiencyvirus(HIV)-infectedindividuals,

accountingfor15%ofalldeathsinthispopulation.1---3In

Por-tugal,CVDisthemajorcauseofdeathoverall,butmortality

fromCVDinthegeneralpopulationis stilllowerthanthat

reportedintheHIVpopulation.Also,themeanageofdeath

inpatientswithHIVinPortugalissignificantlylowerthanin

thegeneralpopulation(52vs.81years).4

Cardiovascular (CV) risk in theHIV-infected population

hasbeenshowntobehigh,anestimated50%higherthanin

uninfectedindividuals,althoughsomeofthedataarestill

controversial.6---11 Traditionalrisk factors such assmoking,

which are particularly prevalent in this population,

con-tributetothisincreasedrisk.1,2,6,11---16Otherfactorsinclude

substance abuse6 and changes in lipid profile1,8,12,15,17

andglucosemetabolism, withincreased insulinresistance

and/orimpairedinsulinsecretion.8,18HIVinfectionitself,as

wellasinflammation andantiretroviraltherapy (ART),are

furthercontributingfactorsinthispopulation.11

Overall,obesityandhigherwaistcircumference(WC)are

knowncauses ofincreasedCVrisk, andinsulinresistance,

changes in lipid profile and increased WC19,20 have been

associatedwithHIVinfectionandtreatment.19,20

While increased WC is the key factor for defining the

presenceof metabolic syndrome (MS)in the non-infected

population,19 in HIV-infected individuals MS is better

identified by increased triglycerides (TG) and decreased

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). It should be

alsonotedthatcardiovasculareventsoccuratmuchyounger

agesintheHIVpopulation.20

AsinthegeneralEuropeanpopulation,obesityisonthe

riseamongHIV-infectedindividuals.17---24InPortugal,obesity

andCVDarehighlyprevalentandcardiovasculareventsare

oneoftheleadingcausesofdeath.5

Cardiovascularriskpredictionalgorithmsweredeveloped

innon-HIV-infectedpopulationsandmaynotaccurately

pre-dict riskfor HIV-infectedindividuals,sincetheetiology of

CVD inthispopulation maybedifferent.The Framingham

riskscore(FRS)calculatesCVDriskandpredictsfuture

coro-nary heart disease events at 10 years. However, the FRS

may wrongly estimate the risk in populations other than

theUSpopulation,andtheEuropeanSociety ofCardiology

accordinglydevelopedandrecommendstheuseofthe

Sys-tematic CoronaryRisk Evaluation (SCORE) tool25 to assess

CVDriskinthegeneralpopulation.TheDataCollectionon

AdverseEvents ofAnti-HIVDrugs(DAD) groupdevelopeda

CVD risk equation specificallydesigned for the HIV

popu-lation, which includes exposure toHIV treatment (use of

indinavir,lopinavir/ritonavirandabacavir),aswellas

tradi-tionalCVriskfactors.26

This study aims to estimate the risk of CVD in

HIV-infected adults, to assess the agreement between the

FRS, SCOREandDAD algorithms,tostudy therelationship

between CV risk and MS in HIV-infected individuals, and

to compare the prevalence of traditional cardiovascular

factorswiththenon-infectedpopulation.Giventheburden

identificationofpatientsathighCVriskcouldleadtomore

tailoredlifestylecounselingandmoreaggressivetreatment

ofcomorbidities.27---29

Methods

Across-sectionalstudywascarriedoutat theDepartment

ofInfectiousDiseases,SantaMariaUniversityHospital,

Lis-bon, Portugal, from December 2013 to May 2014. During

the study period, at least five consecutive HIV-infected

adultswere interviewedper day, randomly selected from

thescheduledappointmentsofthatday. Weaimedto

col-lectasampleofmorethan490patientstoensurethatthe

studypopulation wasrepresentative.Ages rangedfrom18

to65years,andtheinterviewwasperformedonthesame

dayasthehospitalappointment.Exclusioncriteriaincluded

pregnancy, hospitalization in the previous three months,

presenceofopportunisticinfections,kidneyorliverfailure,

institutionalization,residenceoutsidePortugal,orinability

tounderstandandsigntheinformedconsentform.Patients

withknownCVD(coronaryarterydisease,myocardial

infarc-tion,angina,ischemicstroke,hemorrhagicstroke,transient

ischemic attack, peripheral arterial disease and/or heart

failure)werealsoexcluded.Demographicinformation(age,

gender,race),clinicaldata(smokingstatus,familyhistoryof

cardiovascularevents,diagnosisofdiabetesand/or

hyper-tension,timeofHIVdiagnosis),totaltimeandtypeofART,

antihypertensiveorlipid-loweringtherapy,laboratory

mark-ers (CD4+lymphocytecount andviral load,blood glucose,

totalcholesterol,HDL-C,LDLcholesterol,TG)andsystolic

anddiastolicblood pressure(SBPandDBP)werecollected

frommedicalrecords.

CVrisk wasestimated foreach patientusingthree

dif-ferentrisk algorithms: SCOREandthe FRS30,31 for 10-year

riskestimation,andtheDADriskequationforfive-yearrisk

estimation.32

SCORE estimates the risk over a 10-year period of a

firstfatalatheroscleroticevent(suchasmyocardial

infarc-tion, cerebrovascular disease, or other occlusive arterial

disease,andincludingsuddencardiacdeath).Thealgorithm

includesgender,age,totalcholesterol,SBPandsmoking

sta-tus.TheFRSestimates absoluteriskovera10-yearperiod

of cardiovascular events (defined as coronary artery

dis-ease,myocardialinfarction,coronaryinsufficiency,angina,

ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, transient ischemic

attack, peripheral arterial disease, or heart failure). The

adapted algorithm,developedonthe basisof theoriginal

FraminghamscaletobeapplicableinHIV,encompasses

gen-der,age,smokingstatus,presenceofdiabetes,presenceof

leftventricular hypertrophy, totalcholesterol, HDL-C and

SBP. DAD estimates the risk of developing coronaryheart

diseaseandmyocardialinfarctionwithinafive-yearperiod.

The algorithmincludesthefollowing factors:gender, age,

SBP,smokinghabits,familyhistoryofCVD,presenceof

dia-betes,totalcholesterol,HDL-C,andexposure toARTwith

indinavir,lopinavirandabacavir.

IndividualswereclassifiedaspresentinglowCVriskwith

SCORE<4%,FRS<10%orDAD<5%;moderatetohighCVrisk

with SCORE 5-10%, FRS 10-20% or DAD 5-10%; or high CV

risk withSCOREor DAD ≥10%and FRS ≥20%.The original

algorithm for each tool was used and individual risk was

determinedusingIBMSPSS®.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed

usingall factors significantly (p<0.1) associated withhigh

CVrisk(age,gender,smokingstatus,familyhistoryofCVD,

bloodglucose,totalcholesterol,LDL,HDL-C,TG,bodymass

index[BMI],WCandART).

Weight and height were measured with participants

wearinglightclothesandbarefoot,usingacalibratedscale.

These parameters were used to calculate BMI.33 WC was

measuredhalfway betweenthelowest point ofthecostal

margin and the top of the iliac crest. Male patients with

WC≥94cmandfemalepatientswithWC≥80cmwere

con-sideredtohave high WC.34 MS wasdefined inaccordance

withthestandardsoftheInternationalDiabetesFederation,

bythepresenceofatleastthreeofthefollowingcriteria:

increasedWC, TG≥150 mg/dl, HDL-C<40 mg/dlfor men

and <50 mg/dl for women, SBP ≥130 mmHg and/or DBP

≥85mmHgandfastingbloodglucose≥100mg/dl.

Pharma-cologicaltherapyforanyoftheseconditionswasconsidered

analternativecriterion.34

Statistical

analysis

Demographicandclinicalvariableswereanalyzedbyoverall

groupandbygender.Continuousvariablesweresummarized

asmeanandstandarddeviationandcategoricalvariablesas

frequencyandpercentage.Thechi-squaretestwasusedto

determine the independence of categorical variables and

theStudent’s ttest or analysis ofvariance, withmultiple

comparisonsadjustedwiththeBonferronicorrection,were

usedforcontinuousvariables.Unadjustedandadjustedodds

ratios(OR)andthecorresponding95%confidenceintervals

(CI)andp-valueswerereportedforeachanalysis.The

for-wardstepwisemethodwasusedforthemultivariatelogistic

regressionanalysis.Themodel’sgoodnessoffitwasassessed

by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (at least 80% of expected

valueswere≥5).Thesignificancelevelwassetat5%.All

sta-tisticalanalyseswereperformedwithIBMSPSS® software,

version22.0.

ThestudywasapprovedbytheEthicsCommitteeofSanta

Maria Hospital and authorized by the hospital’s Board of

Directors.Allsubjectsprovidedwritteninformedconsent.

Results

Fromthe 3000HIV-infectedadultpatientsfollowed inthe

DepartmentofInfectiousDiseases,719 wererecruitedfor

participation during the study period. Thirty-five did not

consenttoparticipateand113didnotmeettheeligibility

criteria.

Overall, 571 patients were included. Most were male

(n=383; 67.1%) and Caucasian (n=524; 91.3%). Mean age

was46.4±8.9 years; time since HIV diagnosis was 12.8±

6.4 years and only 12 patients had been diagnosed in

theprevious year. Mostpatients(92.5%) hadbeen onART

for 10.4±6.1years.Patientswith aCD4+count >500/mm3

at the time of the study had a longer mean time since

HIV diagnosis than patients with a CD4+count <200/mm3

(13.2±6.2vs. 10.4±7.0 years;p=0.026) and had been on

Table1 Characteristicsofthestudypopulation,overallandbyage.

Overall Age>40years(n=445) Age≤40years(n=126) pb

FamilyhistoryofCVD 52.9(302) 55.3(246) 44.4(56) 0.031 Currentsmoker 53.1(303) 51.9(231) 57.1(72) >0.05 SBP,mmHga 132.4±16.2(86-199) 133.5±16.5 128.1±14.2 0.004 DBP,mmHga 78.2±11.1(52-118) 78.8±11.1 76.0±10.7 0.014 HBP 19.6(112) 24.0(107) 4.0(5) <0.001 Bloodglucose,mg/dla 95.4±20.9(56-300) 96.9±22.0 90.1±15.1 0.001 Diabetes 5.1(29) 6.1(27) 1.6(2) 0.040 TC,mg/dla 191.2±40.7(94-347) 196.6±40.1 172.3±33.9 <0.001 TC≥200mg/dl 38.0(217) 44.0(196) 16.7(21) <0.001 HDL-C,mg/dla 50.9±15.3(22-131) 51.8±15.9 47.8±12.6 0.01 HDL-C<40(M)or<50(F)mg/dl 27.5(157) 26.7(119) 30.2(38) >0.05

HIVdiagnosis,years 12.8±6.4(0-29) 13.9±6.1 8.7±5.6 <0.001

CD4+count,/mm3

Mean 688.7±346.8(22-2269) 702.6±357 639.3±301 >0.05

<200 5.1(29) 5.8(26) 2.4(3) >0.05

200-499 17.9(162) 26.7(119) 34.1(43)

≥500 66.7(380) 67.4(300) 63.5(80)

Viralload(<50copies) 83.9(474) 87.5(384) 71.4(90) <0.001

ART,years 10.4±6.1 11.7±5.8 6.0±4.9 <0.001 Weight,kga 70.8±14.3(39.6-122.1) 71.1±14.4 69.5±13.8 >0.05 BMI,kg/m2a 24.7±4.5(15.4-43.3) 24.9±4.5 23.7±4.1 0.004 Underweight 4.9(28) 3.8(17) 8.7(11) 0.006 Normalweight 54.8(313) 52.6(234) 62.7(79) Pre-obesity 28.9(165) 31.0(138) 21.4(27) Obesity 11.4(65) 12.6(56) 7.1(9) WC,cma 88.5±12.8(60.1-129.0) 90.1±12.7 83.1±11.4 <0.001 WCabovecut-off 41.9(239) 46.7(207) 25.4(32) <0.001

ART:antiretroviraltherapy;BMI:bodymassindex;DBP:diastolicbloodpressure;F:female;HBP:highbloodpressure;M:male;SBP: systolicbloodpressure;TC:totalcholesterol;WC:waistcircumference.

aMean±standarddeviation(minimum-maximum)or%(n). b chi-squareorStudent’sttest.

(11.0±5.9 vs. 8.2±7.0 years; p=0.002). Male participants

presented higher blood glucose and SBP levels. Although

more than half of the participants had normal weight as

definedbyBMI(n=313;54.8%),40.3%(n=230)presentedBMI

≥25kg/m2,whichindicatesexcessweight.Femalepatients

presented a higher prevalence of WC above the defined

cut-off(35.2%vs.36.3%inmales;p<0.001).Regarding

tra-ditionalCVriskfactors,52.9%(n=302)hadafamilyhistory

ofcardiovascularevents,53.1%(n=303) weresmokersand

5.1%(n=29) werediabetic.Almostonethird hadahistory

ofsubstanceabuse(n=166,29.1%).Table1presentspatient

characteristicsandprevalenceofCVDriskfactors.No

signif-icantdifferenceswerefoundbetweengenders,apartfrom

higherHDL-Cinfemalepatients(58.0±16.7mg/dlvs.47.5±

13.3mg/dlinmalepatients;p<0.001)andhigherSBPinmale

patients(134.2±15.4mmHgvs.128.8±17.1mmHginfemale

patients;p<0.001).

Metabolic

syndrome

Of the 571 individuals assessed, 186 (32.6%) had

clini-calcriteriafor MS. Those withMSwere mostlyCaucasian

(n=172; 92.5%) and were older (48.7±8.5 vs. 44.4±

8.8years;p<0.001),hadHIVinfectionforlonger(13.7±6.3

vs.12.4±6.4years;p=0.019)andwereexposedtoARTfor

longer(11.6±5.9vs.9.8±6.2years;p<0.001)than

partici-pantswithout MS. An association wasfound between ART

andthepresenceofMS(OR=2.6[95%CI:1.1-6.0];p=0.018).

IntheMSgroup,96.2%(n=179)wereunderART.

TG≥150mg/dlandahighWCwerefoundtobethemajor

diagnosticfactorsofMS(OR=13.6[95%CI:8.9-20.7];p<0.001

andOR=13.1[95%CI:8.5-20.1];p<0.001,respectively).

Regardinganthropometricparameters,participantswith

MS had higher mean weight (79.5±13.3 vs. 66.5±12.8

kg; p<0.001) and a higher BMI (27.5±4.2 vs. 23.3±

3.9kg/m2,p<0.001)thanparticipantswithoutMS.

Cardiovascular

risk

assessment

Overall,CVrisk showedwidevariationandcalculatedrisk

variedaccordingtothealgorithmused.AhighCVriskwas

found in 4.4% (n=23) of patients when the SCORE tool

was used,in 20.5% (n=117) when FRS wasapplied and in

10.3%(n=59)ofpatientsusingtheDADscore.Patientsunder

ART(n=528)hadasignificantlyhigherCVriskthanART-naïve

patients(n=43)withallthreetoolsused(Figure1).Forthis

reason,furtheranalysiswasperformed intwogroups: the

AR T g roup Naïv e g roup SCORE DAD DAD FRS FRS 0 10 20 30 40 79.1 86 89.3 51.1 67.8 80.6 31.6 17.2 7.1 3.6 7 7 11.6 9.3 10.6 14.9 4.4 21.6 50 60 70 80 90 100 SCORE

Low Moderate High

Figure1 Cardiovascularriskinthestudy populationestimatedbytheSystematicCoronaryRiskEvaluation(SCORE),theData CollectiononAdverseEventsofAnti-HIVDrugs(DAD)riskequationandtheFraminghamriskscore(FRS).ART:antiretroviraltherapy.

Table2 Characteristicsofthestudypopulationbytreatmentgroup.

ARTgroup(n=528) Naïvegroup(n=43) pb

Age,years 47.0±8.5 39.9±11.7 <0.001 FamilyhistoryofCVD 52.3(276) 60.5(26) 0.381 Currentsmoker 53.4(282) 48.8(21) 0.563 SBP,mmHga 132.5±16.5 131.7±11.7 0.564 DBP,mmHga 78.1±11.3 78.6±8.1 0.779 HBP 20.6(109) 7.0(3) 0.003 Bloodglucose,mg/dla 95.9±21.2 90.1±14.3 0.081 Diabetes 5.1(27) 4.7(2) 0.894 TC,mg/dla 191.7±41.3 184.8±31.7 0.289 TC≥200mg/dl 39.2(207) 23.3(10) 0.038 TG,mg/dla 144.0±93.6 118.2±70.7 0.077 TG≥150mg/dl 35.8(189) 25.6(11) 0.177 HDL-C,mg/dla 51.3±15.6 46.3±10.4 0.039 HDL-C<40(M)or<50(F)mg/dl 26.3(139) 41.9(18) 0.028

HIVdiagnosis,years 13.3±6.1 6.7±6.6 <0.001

CD4+count,/mm3

Mean 697.4±348.1 581.1±315.4 0.034

<200 4.4(23) 14.0(6) 0.018

200-499 28.2(149) 30.2(13)

≥500 67.4(356) 55.8(24)

Viralload<50copies 89.5(469) 12.2(5) 0.001

Weight,kga 70.8±14.4 69.8±13.4 0.664 BMI,kg/m2a 24.7±4.4 24.3±5.2 0.582 Underweight 4.2(22) 14(6) 0.202 Normalweight 54.9(290) 53.5(23) Pre-obesity 29.7(157) 18.6(8) Obesity 11.2(59) 14.0(6) WC,cma 88.9±12.9 83.6±10.8 0.009 WCabovecut-off 43.3(228) 25.6(11) 0.023

ART:antiretroviraltherapy;BMI:bodymassindex;DBP:diastolicbloodpressure;F:female;HBP:highbloodpressure;M:male;SBP: systolicbloodpressure;TC:totalcholesterol;WC:waistcircumference.

a Mean±standarddeviation(minimum-maximum)or%(n). b chi-squareorStudent’sttest.

Moderate to very high

Metabolic syndrome

SCORE

Low Low Moderate to very high Low Moderate to very high

DAD FRS 100% 80% 60% 40% 20% 0% 89% 66% 11% 34% 76% 51% 24% 49% 62% 30% 38% 70% No Yes

Figure2 PrevalenceofmetabolicsyndromeinthestudypopulationaccordingtocardiovascularriskasestimatedbytheSystematic CoronaryRiskEvaluation(SCORE),theDataCollectiononAdverseEventsofAnti-HIVDrugs(DAD)riskequationandtheFramingham riskscore(FRS).

Among the 528 patients on ART, almost half (47.2%,

n=249)wereonaprotease inhibitor-basedregimen.Naïve

participants(n=43)wereyounger,hadashortertimesince

HIV diagnosis, had a lower mean CD4+count than the

ARTgroup andwere mostlyin thecategory of CD4+count

<200/mm3. Table 2 presents patient characteristics and

comparisonbytreatmentgroup.

RegardingCVriskfactors,therewerenosignificant

dif-ferences in cholesterol (total or LDL) or smoking status

betweentheART groupandthe naïvegroup.A trendwas

foundfornaïvepatientstopresentlowerTGandblood

glu-coselevels,although this wasnotstatistically significant.

NaïvepatientshadasmallermeanWCthantheARTgroup

(p=0.009).

ThepresenceofMSwasassociatedwithincreasedCVrisk

intheARTgroupwhenallthreetoolswereused(p<0.001)

(Figure 2). In the naïve group the same association was

found, although without statistical significance (data not

shown).

Independentlyofthetoolused,increasedmeanBMIand

WCwerestronglyassociatedwithhigherCVrisk(Figure3).

TheobservedagreementbetweentheFRSandSCOREwas

55.4% (k=0.183, p<0.001),while between FRS and DAD it

CV risk algorithm SCORE (10-year risk) DAD (5-year risk) FRS (10-year risk) BMI WC 5.00 4.00 3.00 2.00 1.00

Figure3 Oddsratiosand95%confidenceintervalsassociated withincreasedbodymassindex(BMI)andwaistcircumference (WC)accordingtocardiovascularriskscore(Systematic Coro-naryRiskEvaluation (SCORE),theDataCollectiononAdverse EventsofAnti-HIVDrugs(DAD)riskequationandthe Framing-hamriskscore(FRS).

was70.5%(k=0.465,p<0.001)andbetweenSCOREandDAD,

72.3%(k=0.347,p<0.001),whichrepresentsfairtomoderate

agreement.35 The observed agreement between the

algo-rithmsdidnotimprovesignificantlywhenonlypatientsaged

over40yearswereanalyzed(datanotshown).

In the final logistic regression model, the factors that

were stillassociatedwithhigherCV riskdiffered

depend-ing on the tool used.When SCORE wasused, the factors

associatedwithhigherCVriskwereolderage(OR=14.4[95%

CI:6.8-30.7];p<0.001)andincreasedTG(OR=2.5[95%CI:

1.5-4.1];p<0.001).UsingtheDADestimator,theassociated

factors were age (OR=21.4 [95% CI: 12.3-37.1]; p<0.001),

increasedTG(OR=3.8[95%CI:2.4-6.0];p<0.001),and

smok-ing(OR=3.8[95%CI:2.2-6.2];p<0.001).UsingtheFRS,the

factors were age (OR=20.6 [95% CI: 12.2-34.8]; p<0.001),

increasedTG(OR=3.9[95%CI:2.5-6.2];p<0.001)and

smok-ing(OR=5.5[95%CI:3.3-9.4];p<0.001).Interestingly,after

applyinglogisticregressiontoourdata,ARTwasonly

associ-atedwithincreasedCVriskwhentheFRSwasused(OR=3.2

[95%CI:1.2-8.5];p=0.002).

Discussion

The present study was conducted in a population of

HIV-infected individuals in Lisbon, mainly composed

of adult Caucasian males. In this sample, traditional CV

risk factors15,26,36---40 were associated with higher CV risk,

in agreementwithprevious studies. However,we found a

much higher prevalence of smoking (53.1%) compared to

thegeneralpopulationinPortugal(20%).41Interestingly,the

prevalenceoflowHDL-C(27.5%)foundinourstudywasless

than in other studies (37.2-36.3%),probably becauseof a

largeproportionofblackpatientsinourstudy(8.7%).

As expected,older patientshad higherCV risk

regard-lessofARTstatus.43Theinclusionofyoungerpatients(<30

years)inthisstudymeanscautionshouldbeexercisedwhen

interpretingthedataonCVrisk,sinceforsomealgorithms,

theriskismostlyrelative.However,dataonmortalityfrom

CVD in the HIV population indicate that evenat younger

ages,thesepatients present non-negligible cardiovascular

mortality,andthiswastheprimaryreasontoincludethese

patientsintheanalysis.44Inaddition,previousstudieshave

reportedtheapplicationofthesealgorithmstoyoungerHIV

IncreasedTGwasthemajorfactorassociatedwithMS.

LowHDL-C,identifiedinpreviousstudiesasthesecondmost

commonfactorassociatedwithMS,waslessstrongly

associ-atedthanincreasedWC.36UnlikeMalobertietal.,45 inthis

study we found that patients with MS presented a longer

meantimesinceHIVdiagnosisandlongerexposuretoART.

The prevalence of MSwas lowerin thisstudy than in the

generalnon-infectedPortuguesepopulation(43.1%).46

The useandclinicalbenefitsofCVriskalgorithmshave

beenmuchdiscussedinrecentyearsanddebatecontinuesas

towhichalgorithmisthemostaccuratefortheHIV-infected

population.Inourstudy,theprevalenceofpatients

classi-fiedasmoderatetohighCVriskusingtheSCOREtoolwas

lower than that found by others39 in which patients with

a knownhistoryof CVD werealso included. However,the

prevalenceinthisstudywashigherthanthatfoundinother

studies,whichcouldbeduetodifferencesinpatients’age.42

Usingthe DAD algorithm,theprevalence of infected

indi-viduals onART with high CV risk wasmuch higher in our

study(10.6vs.2.1%),38whichcouldbeexplainedbythefact

thatourpatientswereonaverage10yearsolderandwere

moreoftensmokers.Finally,usingtheFRS,theprevalence

ofmoderatetohighCVrisk(46.8%)wasmuchhigherthan

thatreportedinotherstudies(6-23.4%).14,38,39,42Again,the

differencesfoundcouldbeduetothehigherprevalenceof

hypertriglyceridemiaandsmokingandolderageinourstudy.

Comparingmoderatetohigh CVrisk bygender,the

preva-lencefoundwassimilartootherstudies,10,16,47highlighting

the increased CV risk seen in males, which is consistent

withdata onuninfected patients. Apart fromSCORE, the

algorithmsshowedthathigherCVriskwasassociatedwith

durationofARTexposure,asreportedbyothers.48Although

somestudies48,49describeahigherincidenceofCVDin

HIV-infectedpatientswithlowerCD4+lymphocytecounts,inthis

study therewere morepatients inthehigher CVrisk

cat-egories witha CD4+count over 500/mm3 than <200/mm3,

whichmaybeduetolongerARTexposureandhencemore

alterationsinlipidprofile.50

Overall,ourresultsindicatethattheDADandFRStools

appear to be more sensitive in detecting high CV risk

patients. Of note, we found that anthropometric

param-eters, although not contributing directly to the CV risk

algorithms, werepositivelyassociatedwithcardiovascular

risk, suggestingthat anynewtooldeveloped toassess CV

risk shouldinclude anthropometricparameters.Given the

resultsofthedifferenttoolsusedinthisstudy,a

longitudi-nal studyis necessarytodetermine theaccuracyof these

estimations.

Regardless of the algorithmused,measuringCV riskin

HIV-infectedpatientsshouldbeconsideredapriority,since

ourresultsdemonstratethatthereisahighprevalenceof

at-riskpatients.DeterminationofCVrisk,usingtoolstailored

tothispopulation,shouldbeseenasroutineforallpatients.

Portugal has a well-established HIV control program, and

prevention has been the primary focus. However, with

the increased survival rate witnessed in the HIV-infected

populationwithART,guidelinesshouldalsoincorporate

rec-ommendations to tackle unhealthy lifestyles, as already

seenforsmoking,particularlypromotionofhealthierdietary

habitsandexercisetoamelioratetheburdenofobesityand

CVD.

Disclosures

Nofinancialsupport.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorshavenoconflictsofinteresttodeclare.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients participating in our

study,as well as the hospital staffat the Department of

InfectiousDiseases,for theirsupportduring the

investiga-tion.

Partiallypresentedatthe12thInternationalCongresson

DrugTherapy in HIV Infection, November 2014, Glasgow,

Scotland(PP195)andatthe36thCongressoftheEuropean

Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, September

2014,Geneva,Switzerland(SUN-PP219).

References

1.Boccara F. Cardiovascular complications and atherosclerotic manifestations in the HIV-infected population: type, inci-dence and associated risk factors. AIDS. 2008;22 Suppl. 3: S19---26.

2.PalellaFJJr,PhairJP.CardiovasculardiseaseinHIVinfection. CurrOpinHIVAIDS.2011;6:266---71.

3.BavingerC,BendavidE,NiehausK,etal.Riskofcardiovascular diseasefromantiretroviraltherapyforHIV:asystematicreview. PLOSONE.2013;8:e59551.

4.INSA.Infec¸ãoVIH/SIDA:asituac¸ãoemPortugala31de dezem-brode2016.Documenton◦148;2017.

5.DGS.PortugalDoenc¸as Cérebro-Cardiovascularesem números --- 2015. Programa Nacional para as Doenc¸as Cérebro-Cardiovasculares;2016.

6.EscárcegaRO, FrancoJJ,ManiBC,et al.Cardiovascular dis-ease inpatientswithchronic humanimmunodeficiency virus infection.IntJCardiol.2014;175:1---7.

7.IslamFM,WuJ,JanssonJ,etal.Relativeriskofcardiovascular diseaseamongpeoplelivingwithHIV:asystematicreviewand meta-analysis.HIVMed.2012;13:453---68.

8.KaminDS,GrinspoonSK.CardiovasculardiseaseinHIV-positive patients.AIDS.2005;19:641---52.

9.Triant VA. Cardiovascular disease and HIV infection. Curr HIV/AIDSRep.2013;10:199---206.

10.LakeJE,WohlD,ScherzerR,etal.Regionalfatdepositionand cardiovascularriskinHIVinfection:theFRAMstudy.AIDSCare. 2011;23:929---38.

11.ShahbazS,ManicardiM,GuaraldiG,etal.Cardiovascular dis-easeinhumanimmunodeficiencyvirusinfectedpatients:atrue orperceivedrisk?WorldJCardiol.2015;7:633---44.

12.HemkensLG,BucherHC.HIVinfectionandcardiovascular dis-ease.EurHeartJ.2014;35:1373---81.

13.FedeleF,BrunoN,ManconeM.Cardiovascularriskfactorsand HIVdisease.AIDSRev.2011;13:119---29.

14.De Socio GV, Parruti G, Quirino T, et al. Identifying HIV patientswithanunfavorablecardiovascularriskprofileinthe clinical practice: results from the SIMONE study. J Infect. 2008;57:33---40.

15.ReinschN,NeuhausK,EsserS,etal.AreHIVpatients under-treated? Cardiovascular risk factors in HIV: results of the HIV-HEARTstudy.EurJPreventCardiol.2012;19:267---74.

16.ShahmaneshM,SchultzeA,BurnsF,etal.Thecardiovascular riskmanagementforpeoplelivingwithHIVinEurope:howwell arewedoing?AIDS.2016;30:2505---18.

17.Mankal PK, Kotler DP. From wasting to obesity, changes in nutritionalconcernsinHIV/AIDS.EndocrinolMetabClinNAm. 2014;43:647---63.

18.Willig AL, Overton ET. Metabolic consequences of HIV: pathogenicinsights.CurrHIV/AIDSRep.2014;11:35---44. 19.WormSW,LundgrenJD. ThemetabolicsyndromeinHIV.Best

practice&research.ClinEndocrinolMetab.2011;25:479---86. 20.JarrettOD,WankeCA,RuthazerR,etal.Metabolicsyndrome

predictsall-causemortalityinpersonswithhuman immunode-ficiencyvirus.AIDSPatCareSTDs.2013;27:266---71.

21.TateT, WilligAL,WilligJH,etal. HIVinfectionandobesity: wheredidallthewastinggo?AntivirTherapy.2012;17:1281---9. 22.Crum-CianfloneN,TejidorR, MedinaS, etal.Obesityamong patients withHIV: thelatestepidemic. AIDS Pat CareSTDs. 2008;22:925---30.

23.LakeJE,CurrierJS.MetabolicdiseaseinHIVinfection.Lancet InfectDis.2013;13:964---75.

24.KimDJ,WestfallAO,ChamotE,etal.Multimorbiditypatterns inHIV-infectedpatients:theroleofobesityinchronicdisease clustering.JAcquirImmuneDeficSyndr.2012;61:600---5. 25.PiepoliMF,HoesAW, AgewallS,etal.2016 European

Guide-linesoncardiovasculardiseasepreventioninclinicalpractice: TheSixthJointTaskForceoftheEuropeanSocietyof Cardiol-ogyandOtherSocietiesonCardiovascularDiseasePreventionin ClinicalPractice(constitutedbyrepresentativesof10societies and byinvitedexperts) Developedwiththespecial contribu-tionoftheEuropeanAssociationforCardiovascularPrevention &Rehabilitation(EACPR).EurHeartJ.2016;37:2315---81. 26.Friis-MollerN,WeberR,ReissP,etal.Cardiovasculardiseaserisk

factorsinHIVpatients---associationwithantiretroviraltherapy. ResultsfromtheDADstudy.AIDS.2003;17:1179---93.

27.CooneyMT,DudinaA,D’AgostinoR,etal.Cardiovascular risk-estimationsystemsinprimaryprevention:dotheydiffer?Do theymakeadifference? Canweseethefuture?Circulation. 2010;122:300---10.

28.Authors/TaskForceM,PiepoliMF,HoesAW,etal.2016 Euro-peanGuidelinesoncardiovasculardiseasepreventioninclinical practice:TheSixthJointTaskForceoftheEuropeanSocietyof CardiologyandOtherSocietiesonCardiovascularDisease Pre-ventioninClinicalPractice(constitutedbyrepresentativesof 10societiesandbyinvitedexperts):developedwiththe spe-cialcontributionoftheEuropeanAssociationforCardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur J Prevent Cardiol. 2016;23:NP1---96.

29.Ladapo JA,RichardsAK, DeWittCM,et al.Disparitiesinthe qualityofcardiovascularcarebetweenHIV-infectedversus HIV-uninfectedadultsintheUnitedStates:across-sectionalstudy. JAmHeartAssoc.2017;6.

30.D’AgostinoRBSr.Cardiovascularriskestimationin2012:lessons learnedandapplicability totheHIV population.JInfectDis. 2012;205Suppl.3:S362---7.

31.DeWitS,BattegayM,D’ArminioMonforteA,etal.European AIDSClinicalSocietySecondStandardofCareMeetingBrussels 16-17November2016:asummary.HIVMed.2018;19:77---80. 32.Friis-MollerN,ThiebautR,ReissP,etal.Predictingtheriskof

cardiovasculardiseaseinHIV-infectedpatients:thedata collec-tiononadverseeffectsofanti-HIVdrugsstudy.EurJCardiovasc PrevRehabilit:OffJEurSocCardiolWorkingGroupsEpidemiol PreventCardiacRehabilitExercPhysiol.2010;17:491---501. 33.WHOExpertCommitteeonPhysicalStatus:theuseand

inter-pretation of anthropometry. Physical status: the use and

interpretationofanthropometry:reportofaWHOExpert Com-mittee,x.Geneva:WorldHealthOrganization;1995.p.452. 34.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the

metabolic syndrome:ajoint interim statementofthe Inter-nationalDiabetesFederationTaskForceonEpidemiologyand Prevention;NationalHeartLung,and BloodInstitute; Ameri-canHeartAssociation;World HeartFederation;International AtherosclerosisSociety;and InternationalAssociationfor the StudyofObesity.Circulation.2009;120:1640---5.

35.LandisJR,KochGG.Themeasurementofobserveragreement forcategoricaldata.Biometrics.1977;33:159---74.

36.SignoriniDJ,MonteiroMC,AndradeMdeF,etal.Whatshould weknowaboutmetabolicsyndromeandlipodystrophyinAIDS? RevAssocMedBrasil.2012;58:70---5.

37.SmithCJ,LevyI,SabinCA,etal.Cardiovasculardiseaserisk fac-torsandantiretroviraltherapyinanHIV-positiveUKpopulation. HIVMed.2004;5:88---92.

38.NeryMW,Martelli CM,Silveira EA, etal. Cardiovascular risk assessment: a comparison of the FraminghamPROCAM, and DADequationsinHIV-infectedpersons.ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:969281.

39.Knobel H,Jerico C,MonteroM, et al.Global cardiovascular riskinpatientswithHIVinfection:concordanceanddifferences in estimates according to three risk equations (Framing-ham SCORE, and PROCAM). AIDS Pat Care STDs. 2007;21: 452---7.

40.GlassTR,UngsedhapandC,WolbersM,etal.Prevalenceofrisk factorsforcardiovasculardiseaseinHIV-infectedpatientsover time:theSwissHIVCohortStudy.HIVMed.2006;7:404---10. 41.DGS.ProgramaNacionalparaaPrevenc¸ãoeControlodo

Tabag-ismo2017;2017.

42.Masia M, Perez-Cachafeiro S, Leyes M, et al. Cardiovascu-lar risk in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in Spain CoRIS cohort, 2011. Enferm Infec Microbiol Clin. 2012;30:517---27.

43.HsuePY,DeeksSG,HuntPW.Immunologicbasisof cardiovascu-lardiseaseinHIV-infectedadults.JInfectDis.2012;205Suppl. 3:S375---82.

44.Croxford S, Kitching A, Desai S, et al. Mortality and causes of deathin people diagnosed with HIV in the era of highly activeantiretroviraltherapycomparedwiththegeneral pop-ulation:ananalysisofanationalobservationalcohort.Lancet PublHealth.2017;2:e35---46.

45.MalobertiA,GiannattasioC,DozioD,etal.Metabolicsyndrome in human immunodeficiency virus-positive subjects: preva-lence,phenotype,andrelatedalterationsinarterialstructure andfunction.MetabSyndrRelDisord.2013;11:403---11. 46.RaposoL, SeveroM, BarrosH, et al.The prevalence ofthe

metabolicsyndromeinPortugal:thePORMETSstudy.BMCPubl Health.2017;17:555.

47.AboudM,ElgalibA,PomeroyL,etal.Cardiovascularrisk eval-uation and antiretroviral therapy effects in an HIV cohort: implicationsforclinicalmanagement:theCREATE1study.IntJ ClinPract.2010;64:1252---9.

48.LichtensteinKA,ArmonC,BuchaczK, etal. LowCD4+Tcell countisariskfactorforcardiovasculardiseaseeventsinthe HIVoutpatientstudy.ClininfectDis:OffPubl Infect DisSoc Am.2010;51:435---47.

49.GrinspoonS,CarrA. Cardiovascularriskand body-fat abnor-malities in HIV-infected adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352: 48---62.

50.HesterEK.HIVmedications:anupdateandreviewofmetabolic complications.NutrClinPract:OffPublAmSocParentEnteral Nutr.2012;27:51---64.