D

ETERMINANTS OFC

ROSS-B

ORDERM

ERGERS ANDA

CQUISITIONSA

NE

CONOMETRICS

TUDY OFT

RANSACTIONS IN THEEURO

Z

ONEB

ETWEEN2001

AND2010

P

ORB

RUNOM

IGUELF

ERRAZM

ONTEIROA

LUNO Nº110487002

T

ESE DEM

ESTRADO EMF

INANÇAS EF

ISCALIDADE2011/12

O

RIENTAÇÃO:

P

ROFESSORD

OUTORS

AMUELC

RUZA

LVESP

EREIRAP

ROFESSORD

OUTORE

LÍSIOF

ERNANDOM

OREIRAB

RANDÃOI

Index

Index 0I

Tables and Figures Index 0 II

Biographic note 0 III

Acknowledgements IV

Portuguese Abstract 0 V

English Abstract 0 VI

I. Introduction 01

II. Previous literature review 04

III. Data and methodology 07

IV. Empirical analysis and main results 16

V. Conclusions 27

II

Tables and Figures Index

Table I 08

Panel A from Table I 09

Figure I 09 Figure II 10 Table II 17 Table II I 19 Table IV 21 Table V 24 Table VI 27

III

Biographic notes

Percurso académico

Bruno Miguel Ferraz Monteiro é licenciado em Direito pela Faculdade de Direito da Universidade do Porto (FDUP), no plano pré-Bolonha, tendo obtido o grau académico em Julho de 2007.

Entre Setembro de 2009 e Julho de 2010, frequentou, com sucesso, a Pós-Graduação em Finanças e Fiscalidade da Porto Business School.

Em Setembro de 2011, ingressou no curso de Mestrado em Finanças e Fiscalidade da Faculdade de Economia da Universidade do Porto (FEP).

Percurso profissional

Após a licenciatura em 2007, integrou a equipa de profissionais de Consultoria Fiscal da Deloitte, onde desempenha, desde Setembro de 2009, funções de Senior Consultant.

A partir de Julho de 2012, assumiu, inclusivamente, as funções de Top Senior, respeitantes ao Senior Consultant com maior senioridade e experiência, com um papel relevante ao nível da gestão da carteira de clientes, mas também da formação interna e da gestão e coordenação de equipas, projectos e definição de budgets.

Esteve envolvido em diversos projectos de auditoria financeira e fiscal e due diligence, no âmbito de operações de M&A, participando já na gestão de alguns clientes recorrentes em matéria de consultoria fiscal regular (em regime de conta corrente) e pontual (em projectos de reorganização societária), entre os quais empresas cotadas no PSI-20 na área dos media, telecomunicações e pasta do papel, bem como a clientes internacionais com presença em Portugal na área do entretenimento (consolas de jogos), logística e comercialização de electrodomésticos.

Adicionalmente, participou, enquanto formando e formador, em inúmeras sessões de formação interna (para colaboradores da rede Deloitte) – a nível nacional e internacional –, e formação externa (destinadas a clientes).

IV

Acknowledgments

Não poderia deixar de aproveitar a oportunidade para deixar uma palavra de agradecimento a alguns contributos sem os quais não teria sido possível concluir esta tarefa.

Desde logo, ao Professor Samuel Pereira pela orientação, disponibilidade e apoio (e paciência) ao longo da elaboração da dissertação, e ao Professor Elísio Brandão pelo constante estabelecimento de objectivos ambiciosos e pelo acompanhamento permanente (que inclusivamente remonta aos tempos da minha frequência da Pós-Graduação em Finanças e Fiscalidade). Sem a sua disponibilidade para me auxiliar na tarefa de suprir a inexistência de bases económicas e financeiras na formação académica anterior, certamente teria sido muito mais complicado concluir esta etapa com sucesso. Gostaria de agradecer a todos os colegas e amigos cujo contributo de revisão, sugestão de alterações e de abordagens foi precioso na fase final da dissertação.

Não posso deixar ainda de reconhecer o papel que a equipa de profissionais de Tax da Deloitte teve na minha evolução como profissional, em particular, pelo método de trabalho, de resiliência e determinação que me incutiram desde o primeiro momento na empresa.

Por fim e a um título mais pessoal, à minha família (Pais, Pedro, Filipa, Elisabete e Margarida) por serem a base de toda a minha vida, o mais tudo, o importante, o suporte para tudo o que consegui até hoje.

VI

Determinants of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions:

An Econometric Study of Transactions in the EURO Zone Between 2001 and 2010

Abstract

Na sequência de estudos anteriores, esta dissertação pretende estudar os principais factores que podem influenciar positiva ou negativamente a ocorrência de operações de fusão e aquisição internacionais, entre empresas de países da Zona EURO. Para o efeito, é analisada uma amostra de 980 operações concretizadas entre 2001 e 2010 nos 13 membros originários da Zona EURO, 218 das quais são transfronteiriças, i.e., entre empresas de países diferentes entre si.

Não obstante, e na medida em que os estudos anteriores identificaram, como os mais importantes proxies deste tipo de operações, as diferenças cambiais e a maior ou menor proximidade geográfica, é nossa intenção analisar mais detalhadamente outros factores, em particular as diferenças de valor, quer ao nível dos países, quer ao nível das empresas envolvidas, bem como questões relacionadas com a tributação internacional (designadamente as diferenças entre os níveis de tributação existentes), as quais poderão influenciar a probabilidade de ocorrência de operações desta natureza.

Os resultados do modelo de regressão em Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) sugerem que a arbitragem de taxas efectivas de imposto e uma menor complexidade da legislação fiscal do país target, a qualidade do relato financeiro e o nível burocrático de cada país, bem como os standards de Corporate Governance e o volume de trocas comerciais aumentam a probabilidade de fusão entre duas empresas de países diferentes.

De modo consistente face a estudos anteriores, as diferenças de valor apresentam um papel fulcral na motivação destas operações: empresas de países cujos mercados de capitais se valorizaram relativamente a outros tendem a ser adquirentes, enquanto empresas de países cujo desempenho da economia é menos positivo tendem a ser targets.

Keywords: International Factor Movements, Valuation differences, Corporate

Governance, Accounting Disclosure, International Tax

VI

Determinants of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions:

An Econometric Study of Transactions in the EURO Zone Between 2001 and 2010

Bruno Miguel Ferraz Monteiro*, Samuel Cruz Alves Pereira † and Elísio Fernando Moreira Brandão ♣1

Abstract

Following to the previous literature, this paper intends to study the main determinants that lead to cross-border mergers and acquisitions in the EURO zone, by analysing a total sample of 980 transactions occurred between 2001 and 2010 in the 13 EURO zone original member countries, 218 of which are cross-border operations.

Nevertheless, and unlike the previous literature, which identified the currency differences and geographical proximity as the most important proxies of this kind of transactions, it is our intention to analyse thoroughly other factors, namely valuation differences and international taxation issues, that may influence the likelihood of cross-border operations.

The Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression results suggest that some issues such as international tax arbitrage and a lower complexity of the target country’s fiscal rules, the quality of accounting disclosure, the level of each country’s bureaucracy, the standards of corporate governance, and bilateral trade increase the likelihood of mergers between two countries.

Similarly to previous literature, valuation appears to play a key role in motivating this specific type of transactions: firms in countries whose stock market has increased its value and that present, at some point, a relatively high market-to-book value tend to be acquirers, while firms from economies with a lower performance tend to be targets.

Keywords: International Factor Movements, Valuation differences, Corporate

Governance, Accounting Disclosure, International Tax

JEL Classification: F23, F29

*

Faculdade de Economia, Universidade do Porto, 110487002@fep.up.pt † Faculdade de Economia, Universidade do Porto, samuel@fep.up.pt ♣Faculdade de Economia, Universidade do Porto, ebrandao@fep.up.pt

1

1. INTRODUCTION

Preliminary remarks

Previous studies have pointed out that the volume of cross-border acquisitions has been growing worldwide. From a conceptual point of view, cross-border mergers should occur for the same reasons as domestic ones: two firms will be keen to merge when there is a perception that their combination will lead to an increase of the global value (or utility). It is important, however, to acknowledge that national borders represent an additional element on the equation of domestic transactions, since they imply an additional set of frictions that can difficult or enable mergers.

For example, corporate governance-related and international taxation differences across countries can motivate a merger if the combined firm has better protection for target-firm shareholders because of higher governance standards in the country of the acquiring firm, or cause, when the difference in the effective tax rates (“ETR”) are substantial, a pure international tax arbitrage effect. On the other hand – but perhaps more importantly –, an imperfect integration of capital markets across countries, in a particular moment of time, can lead to a merger in which a higher-valued acquirer purchases a relatively inexpensive target following changes in stock market valuations.

It is important to refer that, despite we generally follow the methodology of the study “Determinants of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions”, by Erel, Liao and Weisbach (2011), our objective of selecting a sample of transactions occurred in ten years within the EURO member countries, is to deepen the analysis of the valuation differences, by disregarding the effect of currency exchange rates, and, simultaneously, assuming the inexistence of significant cultural or geographical differences (for this purpose) between each country-pair.

We believe that the selected approach will not only allow us to perform a more thorough analysis of the valuation differences, but also undertake a more comprehensive study of the impact of taxation, corporate governance, bureaucracy, and accounting disclosure issues as proxies to the international nature of these operations.

In this paper we intend to evaluate the extent to which these international factors influence the decision of firms to merge.

2

Focus, motivation and contribution

Following Erel, Liao and Weisbach, our analysis will focus, with particular interest, on the impact of the differences in valuation, which can vary substantially over time for any pair of countries through fluctuations in stock market movements, as well as macroeconomic changes.

We will apply an identical empiric methodology to a different sample of deals, with some circumstances that allow us to eliminate the effect of most important finding of those authors’ analysis (i.e., the currency valuation differences).

In this sense, we will not analyse the effect of currency valuation differences, but we will perform, in opposition to previous studies, a more deeper examination of all the other factors that potentially affect cross-border mergers but are not present to the same extent in domestic mergers, such as country-level governance and business environment differences, and – perhaps the most relevant contribution of our study – international taxation issues, either at the complexity of the fiscal rules level or at the ETR differences level.

Key aspects of the empiric study

Our sample reflects the universe of global mergers announced in the EURO zone original member countries, with a special focus on the cross-border transactions, the majority of which involve private firms. In our sample, the majority of cross-border mergers involve private firms as either bidder or target: 63% of the deals involve a private target, 33% involve a private acquirer, and 71% have either a private acquirer or target.

The study begins to document the manner in which international factors affect the cross-sectional pattern of mergers.

According to the methodology followed by Erel, Liao and Weisbach (2011), we next examine the idea that firms’ values change because of both firm-specific and country-specific factors, and these valuation changes are a potential source of mergers. To do so, we first use country-level measures of valuation, since the vast majority of mergers involve at least one private firm for which firm-specific measures are unavailable.

In this context, we firstly estimate multivariate models which intend to predict the number of cross-border deals for particular country pairs.

Then, we also try to examine factors that affect the relation between the intensity of cross-border mergers and valuation differences.

3

Finally, we examine at the deal level whether valuation differences affect the likelihood of cross-border mergers.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows:

Section 2. discusses previous literature on cross-country mergers; Section 3. describes the data and the methodology followed; Section 4. presents the results;

4

2. PREVIOUS LITERATURE REVIEW

The previous studies’ main focus on domestic mergers

Most of the previous studies on this matter focus primarily on domestic deals between publicly traded firms in the U.S.. Despite its relevance to understand the factors that can influence international mergers, most of this literature did not examine the impact of a significant number of factors related to country-based differences between firms, such as international taxation and/or the quality of the economic environment, or factors associated with the economy of the firm’s home country.

Following Erel, Liao and Weisbach, we agree that national boundaries are likely to be associated with many frictions that determine additional firm costs or benefits.

In general, a merger occurs when the managers of an acquiring firm perceive that the value of the combined firm is greater than the sum of the values of the separate firms1.

This change in value can occur for a number of reasons. For instance, a merger can create production efficiencies in combining firms. On the other hand, mergers can also create market power since it is legal for post-merger combined firms to charge profit-maximizing prices but not for the pre-merger separate firms to collude to do so collectively. Mergers can further lower the combined tax liability of the two firms if they allow one firm to use tax shields that another firm possesses but cannot use. Finally, agency considerations can lead managers to make value-decreasing acquisitions that nonetheless increase managers’ individual utilities. All of these factors are relevant both domestically and internationally.

Main cross-country factors

Firstly, we must point out that national borders are also associated with factors that are likely to affect the costs and benefits of a merger.

Cultural differences and geographic distance are factors that should decrease the likelihood that, holding other factors constant, two firms in different countries choose to merge (see Ahern, Daminelli, and Fracassi (2010)).

1

5

Coeurdacier, DeSantis, and Aviat (2009) use a database on bilateral cross-border mergers and acquisitions at the sector level (in manufacturing and services) over the period 1985 to 2004, and find that institutional and financial developments, especially the European Integration process, promote cross-border mergers and acquisitions.

Another work on cross-border mergers and acquisitions includes Ferreira, Massa, and Matos (2009), who find that foreign institutional ownership is positively associated with the intensity of cross-border mergers and acquisitions activity worldwide.

This relation could occur for a number of reasons, including foreign ownership facilitating the transfer of assets or shares, foreign ownership being correlated with more professionally managed companies, or foreign owners being more likely to sell to foreign buyers than local owners.

Simultaneously, corporate governance considerations can also affect cross-border mergers. If a merger increases the legal protection of minority shareholders in target firms by providing them some of the rights of acquiring firms’ shareholders, then value can be created through the acquisition.

In general, corporate governance arguments predict that firms in countries that promote governance through better legal or accounting standards will tend to acquire firms in countries with lower-quality governance (Rossi and Volpin (2004) provide support for this argument using samples of publicly traded firms).

Valuation differences

A potentially factor of extreme importance in international mergers is valuation. Given that markets in different countries are not perfectly integrated, valuation differences across markets can act as a proxy to motivate cross-border mergers.

However, it must be stated that the logic by which valuation differences can lead to cross-border mergers depends on whether participants believe that these movements are temporary or permanent. If the valuation differences are temporary, then cross-border mergers effectively arbitrage these differences, leading to expected profits for the acquirers.

6

The most important study regarding this issue is the behavioural model proposed by Shleifer and Vishny (2003), in which firm values tend to deviate from their fundamentals. Managers of an overvalued acquirer consequently, having access to privileged information (Rhodes-Kropf and Viswanathan (2004)), have incentives to issue shares at inflated prices to buy assets of an undervalued or at least a less overvalued target, and, consequently, value shall be transferred to the shareholders of the acquiring firm by arbitraging the price difference between the firms’ stock prices.

On the contrary, Baker, Foley, and Wurgler (2009) argue that it is not likely that one particular firm’s managers have superior information about the valuation of the overall market.

In this sense, cross-border deals could similarly occur either because of stock mispricing from fluctuations in local investors’ risk-aversion or from irrational expectations about a market’s value (each cause duly accompanied by a limited level of arbitrage). These considerations imply that managers of the target company would be, at a precise moment in time, willing to accept an offer of payment in a temporarily depreciated or overvalued stock.

On the other hand, previous studies predict that if the dominant perspective is that valuation differences are permanent, the attractiveness of mergers would be unaffected by the valuation movements.

Notwithstanding, we must refer that, under certain circumstances, even permanent valuation differences can affect merger propensities. As Kindleberger (1969) originally examines, cross-border mergers can also occur because, under foreign control, either expected earnings are higher or the cost of capital is lower.

Alternatively, it is possible to verify that when a foreign firm’s value increases relatively to a domestic one, for instance, through stock market fluctuations, its cost of capital declines relative to that of a domestic firm. In fact, according to the study from Froot and Stein (1991), permanent changes in valuation allow potential foreign acquirers to bid more aggressively for domestic assets than domestic rival bidders. Consequently, these permanent valuation differences can definitely lead to cross-border mergers because the value changes lead to a lower cost of capital under foreign control.

7

Since this explanation of correlation between market fluctuation movements and cross-border mergers is based on the asymmetry of information, this finding is more likely to be particularly relevant in the case of private targets, for which asymmetric information tends to be higher relative to otherwise similar public targets.

To sum up the above, we expect to observe cross-border mergers following changes in the relative valuation in two countries, regardless of whether they occur through currency or stock price movements, and regardless of whether they are temporary or permanent.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

Finally, we would like to approach FDI. FDI includes cross-border mergers plus other investments in a particular country, as well as retained earnings by foreign subsidiaries and loans from parent companies to their foreign subsidiaries. In fact, using data on FDI, which also includes mergers, would be a possible alternative to use merger data.

However, we follow Erel, Liao and Weisbach and we focus our empirical work on mergers and acquisitions rather than all FDI due to data quality. FDI contains components other than investment such as inter-company loans and retained earnings. In addition, the non-merger component of FDI is measured differently across countries, making cross-country comparisons problematic.

Nevertheless, we still find it useful to mention a previous work by Krugman (1998), which introduced the notion of “Fire-Sale FDI”, capturing the extent to which, during a financial crisis, firms from crisis countries are sold to firms from more developed economies at prices lower than fundamental values.

Notwithstanding the above, our paper tries a more comprehensive approach and considers the issue more generally by looking at the extent to which market movements affect the magnitude of cross-border merger activity.

8

3. DATA AND METHODOLOGY

Sample

Our merger sample was taken from Thomson Reuters’ Security Data Corporation Platinum Corporate M&A database (SDC Platinum), and is constituted by the deals announced and completed between 2001 and 2010. We excluded LBOs, spin-offs, recapitalizations, self-tender offers, exchange offers, repurchases, partial equity stake purchases, acquisitions of remaining interest, and privatizations, as well as deals in which the target or the acquirer is a government agency or in the financial or utilities industry. After excluding these deals, we end up with a sample of 980 mergers covering the 13 original EURO zone member countries, with a total transaction value of $2.78 trillion, 218 of which are cross-border mergers with a total transaction value of $0.6 trillion, as presented below on Table I (including Panel A) and Figures 1 and 2.

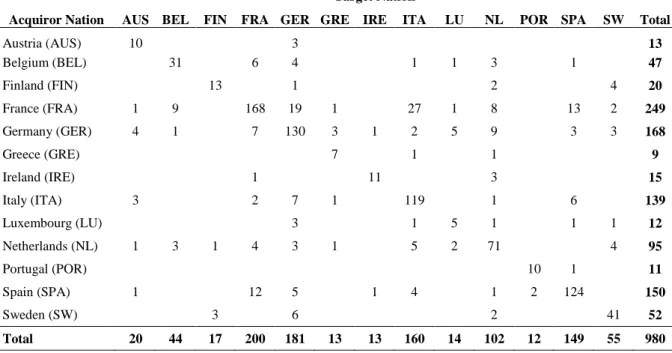

Table I: Total number of mergers and acquisition by country pair.

The columns represent the countries of the acquiring companies while the rows represent those of the target companies. The diagonal entries of the matrix are therefore the number of domestic mergers for a particular country and the off-diagonal entries are the number of deals in a particular country pair. Panel A represents graphically the information presented on this table. Our sample period is from 2001 to 2010.

Acquiror Nation

Target Nation

Total AUS BEL FIN FRA GER GRE IRE ITA LU NL POR SPA SW

Austria (AUS) 10 3 13 Belgium (BEL) 31 6 4 1 1 3 1 47 Finland (FIN) 13 1 2 4 20 France (FRA) 1 9 168 19 1 27 1 8 13 2 249 Germany (GER) 4 1 7 130 3 1 2 5 9 3 3 168 Greece (GRE) 7 1 1 9 Ireland (IRE) 1 11 3 15 Italy (ITA) 3 2 7 1 119 1 6 139 Luxembourg (LU) 3 1 5 1 1 1 12 Netherlands (NL) 1 3 1 4 3 1 5 2 71 4 95 Portugal (POR) 10 1 11 Spain (SPA) 1 12 5 1 4 1 2 124 150 Sweden (SW) 3 6 2 41 52 Total 20 44 17 200 181 13 13 160 14 102 12 149 55 980

9 0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 20.000 40.000 60.000 80.000 100.000 120.000 140.000 160.000 180.000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 % o f to ta l v a lu e fo r a ll d ea ls T o ta l v a lu e o f C ro ss -b o rd er d ea ls (i n 2 0 0 1 $ m il )

Panel A from Table I

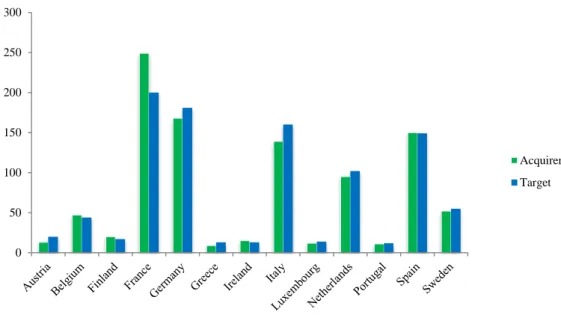

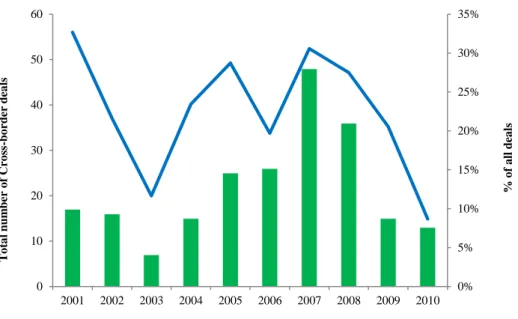

It is important to refer that mergers involving acquirers and targets from different countries are quite substantial, both in terms of absolute numbers, and as a fraction of European mergers activity. Figures 1 and 2 plot the value and number of cross-border deals over our sample period. Both panels show relatively similar patterns.

Figure 1: Total value of cross-border mergers and acquisitions.

This figure plots the value (ratio) of cross-border deals between 2001 and 2010. Bars represent numbers or values while the solid line represents the ratio of cross-border mergers in terms of total number or deal value. All values are in 2001 dollars.

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 Acquirer Target

10 0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 % o f a ll d ea ls T o ta l n u m b er o f C ro ss -b o rd er d ea ls

Figure 2: Total number of cross-border mergers and acquisitions.

This figure plots the number (ratio) of cross-border deals between 2001 and 2010. Bars represent numbers or values while the solid line represents the ratio of cross-border mergers in terms of total number or deal value. All values are in 2001 dollars.

The volume of cross-border mergers decreases after the stock market crash of 2000/2001 until the lowest results on 2003, increases from 2004 until 2007 and then decreases again from 2008 onwards.

As a fraction of the total value of worldwide mergers, cross-border mergers typically amount to between 10% and 30%. The fraction of cross-border deals follows the overall level of the stock market: the fraction drops until 2003, then increases with the stock market again between 2004 and 2007. From 2008 onwards, and with an exception of 2009 for deal values, the fraction generally decreases.

Variables and data

In Table II, we consider as dependent variable the total number of cross-border deals (Xij) in which the target is from country i and the acquirer is from country j (where i≠j) scaled by the sum of the number of domestic deals in target country i (Xii) and that of cross-border deals between country i and country j (Xij).

11

In Tables III to V, our dependent variable is the total number of cross-border deals in year t (Xijt) in which the target is from country i and the acquirer is from country j (where i≠j) scaled by the sum of the number of domestic deals in target country i (Xiit) and that of cross-border deals between country i and country j (Xij).

In fact, for both estimations, including domestic deals in the denominator allows us to implicitly control, for each country/country-pair and year the effects that can influence the volume of both domestic deals and cross-border deals.

In Table VI, the dependent variable for our logit model equals 1 for cross-border deals and 0 for domestic ones.

We also collected a number of data items from SDC Platinum, including the announcement and completion dates, the target’s name and its public status, country of domicile, as well as the acquirer’s name, public status and country of domicile, besides the deal value in U.S. dollars and the fraction of the target firms owned by the acquirer after the acquisition.

Afterwards, concerning the independent variables, we acquired monthly firm-level and country-level stock returns both in EURO and in U.S. dollars from Datastream.

To calculate real stock market returns and real exchange rate returns, we obtained from Datastream the monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI) for each country in each month and convert all nominal returns to the 2001 price level.

Following the procedure performed by Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer (2008) – see also Bekaert et al. (2007) –, we obtained ratings on the quality of accounting disclosure, on the complexity of the procedures to start a business, on the level of protection of the investors, on the ease of getting credit and the rank of resolving insolvency time and cost, and, finally, ratings on corporate governance standards from the World Bank’s annual Doing Business Report, in order to assemble an ad hoc Doing Business Index, as a proxy to each country’s business environment and the quality of its institutions.

On the other hand, we collected country-level and deal-level data on the GAAP Effective Tax Rate (ETR) from Datastream and Eurostat, computed as the average corporate income tax expense in each country normalized by the pre-tax income.

12

Also related to taxation matters, we used the European Commission’s Fiscal Rules Index, a comprehensive time-varying fiscal rule index for each Member State, which is considered as a proxy to the complexity, enforceability and effectiveness of the tax domestic legislation of each country.

We obtain annual Gross Domestic Product (in EURO at 2001 prices) normalized by population and the annual real growth rate of Gross Domestic Product from Eurostat.

Similarly to Erel, Liao and Weisbach, to control for the volume of business between a country pair, we include bilateral trade flows, calculated as the value of imports (exports) by the target country from (to) the acquirer country as a percentage of total imports (exports) by the target country, all of which are from the United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics database (see Ferreira, Massa, and Matos (2009)).

For the public firms in our mergers sample, we obtain accounting information from Worldscope/Datastream.

In particular, we use firm size (book value of total assets), equity ratio (shareholder’s equity divided by total assets), as well as the market-to-book ratio.

To calculate country-level market-to-book ratios, we follow Fama and French (1998) and sum the market value of equity for all public firms in a country and then divide this figure by the sum of all public firms’ book values.

The details on the definitions of the variables used in the empiric study can be found in the following table.

Variable Description

Panel A: Country-level variables Cross-border

M&A

country-pairs (xji)

The total number of cross-border deals (Xij) in which the target is from country i and the acquirer is from country j (where i≠j) scaled by the sum of the number of domestic deals in target country i (Xii) and that of cross-border deals between country i and country j (Xij).

(Source: SDC Platinum Mergers and Corporate Transactions database) Annual

cross-border M&A country pairs (xjit)

The total number of cross-border deals in year t (Xijt) in which the target is from country i and the acquirer is from country j (where i≠j) scaled by the sum of the number of domestic deals in target country i (Xiit) and that of cross-border deals between country i and country j (Xij).

(Source: SDC Platinum Mergers and Corporate Transactions database) (Country MTB)

j-i

The difference between acquirer (j) and target (i) countries of domicile in value-weighted market-to-book equity ratio.

13

(Country R12) j-i

The (average) difference between the annual local real stock market (previous) 12 months return of the acquirer country (j) and target country (i), deflated using the 2001 Consumer Price Index (CPI) in each country to calculate real stock returns.

(Source: Datastream) (Country FR12)

j-i

The (average) difference between the annual local real stock market return of the acquirer country (j) and target country (i) after the deal, deflated using the 2001 CPI in each country to calculate real stock returns.

(Source: Datastream) Doing Business

Index

Dummy variable equals 1 if the position of the target country in the assembled Index is higher than the acquirer country or 0 if it is lower (Source: Annual Doing Business Report from World Bank)

ETR Dummy variable equals 1 if the average GAAP ETR of the target country is lower than the acquirer country’s or 0 if it is higher (Source: Eurostat)

Fiscal Rules Index Dummy variable equals 1 if the position of the target country in the European Commission’s National

Fiscal Rules Index is higher than the acquirer country or 0 if it is lower (Source: European Commission) (log GDP per

capita) j-i

The (average) difference between acquirer (j) and target (i) countries of domicile in the logarithm of annual Gross Domestic Product (GDP, in Euro) divided by each country’s population

(Source: Eurostat)

(GDP Growth) j-i

The (average) difference between acquirer (j) and target (i) countries of domicile in the annual real growth rate of the GDP

(Source: Eurostat)

Bilateral flows

The maximum of bilateral import and export between a country pair. Bilateral import (export) is calculated as the value of imports (exports) by the target country from (to) the acquirer country as a percentage of total imports (exports) by the target country, based on the Harmonized System definition (Source: UN commodity trade database)

Panel B: Deal-level variables

(Firm Stock Return 12m) j-i

The difference between acquirer (j) and target (i) in annual real stock market returns. We obtain total return indices for all public firms and deflate these indices using the 2001 CPI to calculate real stock returns. (Source: Datastream)

Firm Size (log) Book value of total assets in millions of constant 2001 Euro.

(Source: Datastream)

Equity ratio Equity value scaled by the value of total assets in millions of constant 2001 Euro.

(Source: Datastream)

ETR j-i The average difference between acquirer and target companies’ GAAP ETR

(Source: Datastream)

This table describes all variables used in the paper. Country-level data items are measured at the annual frequency. Deal-level items are measured in the year-end prior to the deal announcement date.

Methodology

Using the sample exhaustively described above, our empirical study begins (Table II below) to document the manner in which international factors affect the cross-sectional pattern of mergers, for the whole period under analysis (2001-2010), by estimating with an OLS regression 2.

2

We also experimented other approaches (e.g., fixed and random effects, Generalized Linear Models, Auto Regressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity), but in all cases the variable coefficients lose or lower its statistical significance.

14

However, considering that standard estimation by OLS implies that all observations are homogeneous regarding the variance of disturbances or “errors” – homoskedasticity –, so they have equal weight in estimation, heteroskedasticity becomes a common problem to cross-sectional data analysis on a linear regression.

In this sense, we find it prudent to include an estimator for heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors. On the other hand, all regressions also include country-specific dummy variables.

According to the methodology proposed by Erel, Liao and Weisbach (2011), we next examine the idea that firms’ values change because of both firm-specific and country-specific factors, and these valuation changes are a potential source of mergers.

We rely on a multivariate framework that intends to control for other potentially relevant factors in order to formally evaluate the possibility that relative valuation can influence the likelihood of merger.

Similarly to the mentioned authors, and as explained above, we begin by using country-level data in Tables III to V. In fact, despite this approach does not consider firm-level information, it has the merit of analyzing a broader sample of deals and allowing to test the most important hypotheses such as country-level stock market return movements and fluctuations or international taxation issues, which are more thoroughly testable using country-level data.

Nevertheless, since we recognize the importance of approaching firm-specific factors, we find it worthwhile to try to mitigate the disadvantage described above by analyzing firm-level data on Table VI.

In this context, we first use country-level variables, i.e., measures of valuation (as described above), since the vast majority of mergers involve at least one private firm for which firm-specific measures are unavailable.

In Table III we estimate OLS multivariate models with the intention of predicting the number of cross-border deals for particular country pairs, considering the influence of the variables listed above.

15

We also try to examine factors that affect the relation between the intensity of cross-border mergers and valuation differences.

Similarly to Table II, not only we considered an estimator for heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors, all regressions also include country-specific dummy variables.

We propose to perform clustering of observations in order to examine 4 subsamples of deals, in which various combinations of public/private status of each company involved in the deals are selected and then aggregated to the country level.

Table IV performs robustness check to the results obtained in Table III. Therefore, we carry out identical estimations to Table III, but with a different set of subsamples, according to the fraction of the target’s share capital acquired.

In Table V, with the same methodology as in Table III, we try to examine the two potential (but not mutually exclusive) explanations for the pre-acquisition stock return differences between acquirer and targets proposed by the previous literature: either due to the fact that a) returns can affect the relative wealth of the two countries, leading firms in the wealthier countries to purchase firms in the poorer countries (Froot and Stein (1991)), or b) either overpricing of the acquiring firm or underpricing of the target firm.

In this particular, we follow Erel, Liao and Weisbach and perform a test to distinguish between the two explanations based on the implication that following acquisitions due to mispricing, valuations will tend to revert to their true values, an approach proposed by Baker, Foley, and Wurgler (2009).

Finally, in Table VI, we consider the smaller sample of all public (i.e., public acquirers and targets) deals, including domestic mergers and estimate the characteristics of the firms that lead to a particular merger or acquisition to be either domestic or cross-border.

As Erel, Liao and Weisbach, we then estimate logit models that predict whether an observed deal is domestic or cross-border as a function of the respective characteristics.

In fact, this approach suggests the domestic mergers would be a valuable benchmark in order to fully understand the nature and the factors that may lead to cross-border transactions.

16

4. EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS AND MAIN RESULTS

Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Determinants of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions

To analyze the cross-sectional patterns among acquirers and targets more formally, we use a multivariate OLS regression framework in Table II. Our goal is to measure the factors affecting the propensity of firms of one country to acquire firms of another country. Our dependent variable measures the typical proportion of cross-border mergers for a particular country pair over the entire sample period.

For each ordered country pair, the fraction is determined by a numerator equal to the number of cross-border acquisitions of firms in a target country by firms in an acquirer country, normalized by the sum of the number of domestic acquisitions in the target country and the numerator, so that the fraction is bounded above by one. Including domestic deals in the denominator allows us to implicitly control for factors that can influence the volume of both domestic deals and cross-border deals.

We estimate equations explaining the above variable as a function of country characteristics. Since each observation is a “country pair” and we have 13 countries, the total number of potential observations is 156 (13×12).12 However, we impose the requirement that a country pair have at least one deal during the sample period, which reduces the total number of observations to 62.3

1 22

3 We also estimated our equations without this requirement. The results from these alternative specifications are

17

Table II.

Columns 1 through 6 examine the entire sample of cross-border deals. Refer to the Section 3 for the variable definitions. Acquirer country fixed effects are included in all regressions. Heteroskedasticity-corrected t-statistics are in parentheses. The symbols ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

All Acquirer – All target

Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6

Average (Country MTB) j-i 0.322 **

(1.092)

0.195 ** (0.582)

Average (Country R12m) j-i -0.052 *

(0.350)

-0.034 * (0.243)

Doing Business Index 0.026 **

(1.089) 0.013 * (0.538) ETR 0.014 ** (0.636) 0.021 ** (0.884)

Fiscal Rules Index 0.002 ***

(0.051)

0.047 ** (2.137)

(log GDP per capita) j-i 0.074 * 0.081 * 0.077 * 0.075 * 0.090 ** 0.077 ***

(1.728) (1.876) (1.924) (1.714) (2.284) (2.658) (GDP Growth) j-i -2.870 *** -2.943 * -3.222 *** -2.753 ** -3.428*** -3.350 *** (-2.867) (-2.668) (-2.828) (-2.378) (-3.569) (-2.908) Bilateral flows 0.247 ** 0.180 * 0.198 ** 0.211 * 0.125 0.182 ** (1.945) (1.724) (1.813) (1.858) (1.221) (1.051) Constant 0.096 *** 0.091*** 0.081 *** 0.101 *** 0.062 *** 0.073 *** (7.339) (7.756) (6.450) (5.426) (4.801) (3.201) Number of Observations 62 62 62 62 62 62 R-squared 0.373 0.364 0.380 0.367 0.428 0.446 Adjusted R-squared 0.329 0.319 0.336 0.322 0.388 0.362

A first impression on this cross-sectional analysis is that some patterns characteristics of the identity of acquirers and targets seem to appear.

First, and similarly to Erel, Liao and Weisbach (2011), the coefficient on the average stock market return difference is negative and statistically significant but this effect seems to be opposed by the average country-level market-to-book ratio, which shows a significantly positive coefficient.

Second, consistent with the results obtained by Rossi and Volpin (2004) regarding accounting disclosure quality, a higher rating in the newly-assembled Doing Business Index increases the likelihood that firms from the given country will be purchasers of firms from another country.

18

Third, our results show that tax-related issues are an important determinant for this type of international deals. In fact, our analysis suggests that either a lower ETR or a lower degree of complexity of the fiscal law in the target country have a positive and statistically significant role in the attraction of foreign investment.

On the other hand, our GDP growth variable is both negative and significant, suggesting that firms from a country with a higher GDP Growth tend to be acquirers while firms from a country with a lower GDP Growth are more likely to be targets than purchasers.

Finally, we would like to also point out that, consistently with Erel, Liao and Weisbach, the higher the volume of bilateral trade flows between two countries, the largest the likelihood of two firms of both countries will be.

Panel Data Analysis of the Determinants of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions

In this matter, we follow Erel, Liao and Weisbach (2011), we rely on a multivariate framework that intends to control other potentially relevant factors in order to formally evaluate the possibility that relative valuation can influence the likelihood of merger, using country-level data.

We estimate a specification in which the dependent variable is the number of deals between an ordered country pair, normalized by the sum of the total number of domestic deals in the target country and the number of cross-border deals between these countries in a given year.

In this sense, country-pair and year fixed effects are included in all regressions, in order to control for the cross-sectional factors and long-term trends that affect merger propensities (Table II). This specification will allow us to exploit time-series variations in relative valuation while controlling for cross-country differences.

Our sample consists of country pairs with at least one observation per year for each pair, for a total of 150 observations. We report these estimates in Table III.

19

Table III.

Columns 1 and 2 examine the entire sample of cross-border deals. Columns 3 through 10 examine subsamples of deals, in which various combinations of public status of the parties are selected and then aggregated to the country level. Refer to Section 3 for variable definitions. Country pair and year fixed effects are included in all regressions. Standard errors are corrected for clustering of observations at the country pair level and associated t-statistics are in parentheses. The symbols ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively. All Acquirer All target Private Acquirer Private Target Private Acquirer Public Target Public Acquirer Private Target Public Acquirer Public Target Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 (Country MTB) j-i 0.076** 0.142*** -0.052 0.155 *** 0.127*** (1.992) (3.246) (-0.733) (-3.280) (-2.171) (Country R12m) j-i 0.028** 0.061* 1.457 0.189** 0.041** (0.229) (0.219) (0.879) (-1.163) (-0.166)

Doing Business Index -0.103** -0.088* -0.149

*** -0.191*** -0.522 -0.905** -0.134** -0.062 -0.050 -1.141 (-2.040) (-1.713) (-2.957) (-1.937) (-1.599) (-3.225) (-1.965) (-0.906) (-0.384) (0.001)

ETR 0.065* 0.082* 0.011 -0.003 0.108 0.225* 0.108 0.112 0.043 0.175*

(1.776) (1.876) (0.174) (-0.039) (1.026) (1.132) (1.683) (1.244) (0.423) (0.182) Fiscal Rules Index 0.067** 0.074*** 0.143*** 0.145*** 0.092 0.124 0.009 -0.001 0.074** 0.109***

(3.514) (3.616) (4.706) (3.409) (1.412) (1.519) (0.270) (-0.017) (1.872) (2.843) (log GDP per capita) j-i 0.030 0.036 0.071 0.207 0.043 0.151* -0.156** -0.151** 0.069 0.127

(0.418) (0.478) (0.505) (1.539) (0.203) (0.602) (-1.948) (-2.456) (0.688) (0.014) (GDP Growth) j-i 0.273** 0.284** 0.633*** 0.700*** 0.206 -0.467 0.114 0.225 0.277 0.108 (2.475) (2.312) (3.288) (3.182) (1.112) (-0.631) (0.616) (0.976) (1.039) (0.464) Bilateral flows -0.178** -0.135 *** -0.045 -0.182*** -0.098 -0.268*** -0.199*** -0.110*** -0.263*** -0.160** (-4.552) (-4.925) (-0.835) (-2.595) (-0.571) (-0.817) (-4.057) (-3.081) (-3.486) (-2.244) Constant 0.455*** 0.395*** 0.445*** 0.605*** 0.748** 1.150** 0.444*** 0.314*** 0.486*** 0.291** (7.630) (6.739) (6.409) (4.441) (3.724) (3.158) (0.583) (5.140) (3.578) (2.216) Observations 150 150 37 37 12 12 58 58 43 43 R-squared 0.402 0.364 0.732 0.635 0.950 0.960 0.544 0.380 0.508 0.447 Adjusted R-squared 0.373 0.333 0.668 0.547 0.863 0.890 0.480 0.293 0.409 0.337

As described above, the stock return differences are measured over the 12 months prior to the year in question, so that (Market R12m)j-i is the difference in the past 12-month real stock market return between acquirer and target countries, and (Country MTB)j-i is the difference in the country-level value-weighted market-to-book ratios between acquirer and target countries.

20

All equations also include the volume of bilateral trade between the two countries, dummy variables related to the GAAP ETR, Doing Business Index and the National Fiscal Rules index, as well as macroeconomic variables such as the difference in log GDP per capita and the difference in GDP growth rate between the two countries. In all equations, standard errors are calculated correcting for clustering of observations at the country-pair level.

Columns 1 and 2 present the estimates including all deals while Columns 3 to 10 report estimates for subsamples based on whether deals involve a private or public acquirer and target.

The coefficients on stock return and market-to-book differences have a positive and statistically significant coefficient in all equations except for those estimated on private acquirer - public target subsample (Columns 5 and 6). These positive coefficients on the valuation differences suggest that if the valuations are higher in country j than in country i, the expected number of acquisitions by firms of country j of firms of the country i is more likely to increase.

Additionally, it must also be pointed out that the larger effect for private targets than for public targets is consistent with the Froot and Stein (1991) arguments, since asymmetric information about the target’s true value is likely to be higher when the target is private.

These results suggest that while valuation differences can be important drivers of mergers in situations where there are other reasons for firms to merge, they are not as important in situations in which a valuation difference is the only reason for the merger.

Determinants of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions: Robustness check

To perform the analysis presented above, we had to make a number of choices about the sample and specification. Table IV contains estimates of equations similar to those reported in Table III to examine the robustness of the results to alternative specifications and subsamples.

The sample used to estimate the equations in Tables III includes all deals.

An important issue is the extent to which the results and conclusions about valuation differences and international taxation as drivers for merger propensity hold in cases in which an acquirer purchases a minority stake (0% to 49%), and whether the results for majority (50% to 99%) acquisitions are different from the results for 100% acquisitions.

21

In Columns 2, 3, and 4 of Table IV, we provide estimates of the equation reported in Table III for deals that lead to minority ownership (5% to 49%), for majority but incomplete acquisitions (50% to 99%), and for 100% acquisitions.

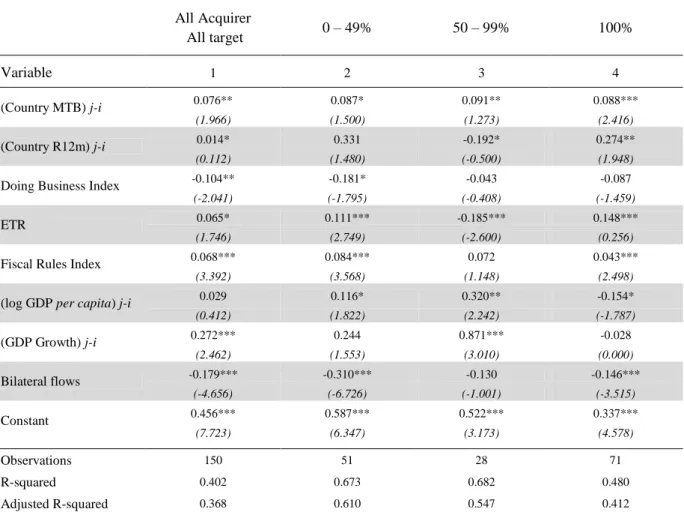

Table IV.

Column 1 examines the entire sample of border deals. Columns 2 through 4 examine subsamples of cross-border deals based on the ownership stake the acquiring firm obtains. Refer to Section 3 for variable definitions. Country pair and year fixed effects are included in all regressions. Standard errors are corrected for clustering of observations at the country pair level and associated t-statistics are in parentheses. The symbols ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

All Acquirer All target 0 – 49% 50 – 99% 100% Variable 1 2 3 4 (Country MTB) j-i 0.076** 0.087* 0.091** 0.088*** (1.966) (1.500) (1.273) (2.416) (Country R12m) j-i 0.014* 0.331 -0.192* 0.274** (0.112) (1.480) (-0.500) (1.948)

Doing Business Index -0.104** -0.181* -0.043 -0.087

(-2.041) (-1.795) (-0.408) (-1.459)

ETR 0.065* 0.111*** -0.185*** 0.148***

(1.746) (2.749) (-2.600) (0.256)

Fiscal Rules Index 0.068*** 0.084*** 0.072 0.043***

(3.392) (3.568) (1.148) (2.498)

(log GDP per capita) j-i 0.029 0.116* 0.320** -0.154*

(0.412) (1.822) (2.242) (-1.787) (GDP Growth) j-i 0.272*** 0.244 0.871*** -0.028 (2.462) (1.553) (3.010) (0.000) Bilateral flows -0.179*** -0.310*** -0.130 -0.146*** (-4.656) (-6.726) (-1.001) (-3.515) Constant 0.456*** 0.587*** 0.522*** 0.337*** (7.723) (6.347) (3.173) (4.578) Observations 150 51 28 71 R-squared 0.402 0.673 0.682 0.480 Adjusted R-squared 0.368 0.610 0.547 0.412

The coefficient on the market-to-book difference between the acquirer and target countries remain generally positive and statistically significant, while the coefficient on the country-level stock return difference is not statistically significant in Column 2. It must be pointed out that, in Column 3, the coefficients on both country-level stock return difference and ETR are not positive, while the coefficient of the Fiscal Rules Index dummy is not, in this case, statistically significant at the 10% level.

22

Despite these somewhat ambiguous results (which however do not contradict the global conclusions of Table III), it is still possible to assume that the global results suggest that the conclusions on either the valuation effect or on the international taxation issues appear to be robust regardless of the fraction of stock purchased by the acquirer.

Deepening the Analysis of Valuation Differences on Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions

In the previous Sections, we have discussed some possible explanations for the influence between valuation and merger propensities. Either an increase in relative valuation through stock price fluctuation could reflect real increases in wealth (e.g., Froot and Stein (1991)) or a larger difference in terms of comparative effective tax rates, could enhance firms’ abilities to finance acquisitions.

Alternatively, another possible explanation has been proposed by Shleifer and Vishny (2003), according to which the mentioned changes in relative valuation could reflect errors in valuation. In this case, firms should rationally and intentionally take advantage of this misevaluation to purchase relatively (and temporarily) cheap assets, i.e., firms in another country who are not as overvalued. The overvaluation argument would perhaps be mainly applicable to public acquirers who can either issue equity or make stock acquisitions to take advantage of the referred high valuation, but as Baker, Foley, and Wurgler (2009) argue, it could potentially apply to private acquirers as well if the overvalued equity market reflects itself in decreasing the cost of capital in a certain country for private firms.

A prediction made by the previous literature regarding the incorrect relative valuation argument is that, after acquisitions made by relatively overvalued firms, acquirers should underperform relative to targets and, therefore, there should be an effect that could be named as price reversal.

In fact, the overvaluation argument implies that if an acquirer purchases a target to arbitrage differences across countries, it is likely that differences should narrow subsequent to the acquisition.

Following Erel, Liao and Weisbach, we reestimate our regression from Table III, including future return differences to evaluate this possibility.

The results are presented in Column 1 of Table V for all mergers and in Columns 3, 5, 7, and 9 for the subsamples based on whether the acquirer and the target are public or private firms.

23

Additionally, we also follow a methodology proposed by Baker, Foley, and Wurgler (2009), which consists of decomposing the market-to-book ratio of each country using future stock market returns, in order to deepen the analysis regarding the identification of the main reasons and factors that could explain these valuation differences across countries.

These authors argue that the market-to-book ratio can be divided into two different components: the component due to real expected wealth and the component due to the market’s over-reaction or under-reaction to news.

To estimate the extent of each component, Baker, Foley, and Wurgler (2009) estimate equations in which the market-to-book ratio is a function of future stock returns. To the extent that the market-to-book ratio reflects overvaluation at the time of acquisitions, periods of high acquisition activity should be followed by periods of poor returns. The “fitted” component of market-to-book should represent that component arising from overvaluation while the “residual” component should come from real wealth effects.

The results of these equations are presented in Column 2 of Table V for all mergers and in Columns 4, 6, 8, and 10 for the subsamples based on whether the acquirer and the target are public or private firms.

24

Table V.

Columns 1 and 2 examine the entire sample of cross-border deals. Columns 3 through 10 examine subsamples of deals, in which various combinations of public status of the parties are selected and then aggregated to the country level. Refer to Section 3 for variable definitions. Country pair and year fixed effects are included in all regressions. Standard errors are corrected for clustering of observations at the country pair level and associated t-statistics are in parentheses. The symbols ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively. All Acquirer All target Private Acquirer Private Target Private Acquirer Public Target Public Acquirer Private Target Public Acquirer Public Target Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 (Country FR12m) j-i 0.129** 0.082** -0.177 -0.171** 0.366** (1.125) (0.608) (0.693) (0.801) (1.165) (Country Fitted MTB) j-i 0.134** -0.091** -0.170 -0.123** 0.427** (1.132) (-0.650) (-0.377) (-0.615) (1.166) (Country Residual MTB) j-i 0.072* 0.146*** 0.022 0.157*** 0.113* (1.737) (3.219) (0.159) (3.021) (1.704) Doing Business Index -0.098** -0.107** -0.194** -0.148*** -0.833*** -0.720 -0.094 -0.131** -0.013* -0.052* (-1.957) (-2.156) (-2.091) (-2.913) (-5.203) (-0.880) (-1.232) (-1.933) (-0.102) (-0.412) ETR 0.086** 0.067* -0.003* 0.012* 0.120 0.123 0.123*** 0.105* 0.126** 0.024* (2.011) (3.518) (-0.041) (0.180) (1.051) (0.958) (1.354) (1.770) (1.083) (0.212) Fiscal Rules Index 0.073*** 0.067** 0.142*** 0.144*** 0.035 0.054 0.001 0.009* 0.107*** 0.076** (3.720) (1.901) (3.432) (4.746) (0.764) (0.358) (0.039) (0.272) (2.974) (1.961) (log

GDP per capita) j-i

-0.031 -0.028 -0.222* -0.064 -0.194 -0.144 0.142*** 0.158* -0.069 -0.032* (-0.421) (-0.389) (-1.723) (-0.435) (-0.737) (-0.363) (2.276) (1.927) (-0.459) (-0.255) (GDP Growth) j-i -0.285*** -0.273*** -0.700*** -0.636*** -0.046 -0.097 -0.197 -0.117 -0.191** -0.322*** (-2.337) (-2.446) (-3.212) (-3.235) (-0.362) (-0.227) (-0.916) (-0.664) (-0.657) (-1.126) Bilateral flows -0.131*** -0.175*** -0.182*** -0.039 0.022 -0.029 -0.121*** -0.200*** -0.147*** -0.241*** (-4.697) (-4.118) (-2.917) (-0.687) (0.516) (-0.089) (-3.067) (-3.939) (-2.601) (-2.841) Constant 0.396*** 0.453*** 0.607*** 0.438*** 0.920*** 0.859 0.341*** 0.444*** 0.305*** 0.470*** (6.842) (7.404) (4.597) (6.592) (8.488) (1.844) (5.325) (5.784) (2.758) (3.248) Observations 150 150 37 37 12 12 58 58 43 43 R-squared 0.371 0.403 0.637 0.733 0.951 0.952 0.384 0.544 0.480 0.526 Adjusted R-squared 0.340 0.370 0.550 0.657 0.866 0.823 0.298 0.470 0.376 0.415

Likewise the study of Erel, Liao and Weisbach, the results are somewhat ambiguous, but indicate that the difference in country-level stock returns tends to persist following the acquisition, which could give a first impression of inconsistency with the notion that overvaluation explains the impact of valuation on merger decisions.

Nevertheless, it is possible that the future returns tests are not particularly powerful since they only make use of the component of overvaluation that can be explained by future returns over a pre-specified interval.

25

To test this hypothesis formally, as referred above, we follow Erel, Liao and Weisbach and use an approach introduced by Baker, Foley, and Wurgler (2009).

In the first-stage equation, country-level market-to-book ratios are regressed on future returns and the coefficient results on future returns are negative, a finding that is consistent with the previous literature that found a negative relation between future stock returns and country-level market-to-book ratios in a given country.

However, when we decompose the differences in market-to-book between countries into their “fitted” and “residual” components (see Columns 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 of Table V), for most specifications only the residual is, in every regression, positively and significantly related to the ratio of cross-border mergers, as predicted by the wealth effect hypothesis.

Only in the sample of acquisitions of public firms by private acquirers, for which stock market misvaluation is least likely to affect acquisitions, the differences either of the fitted values or the residual components are not statistically significant.

Consistently with Erel, Liao and Weisbach, these results suggest that the valuation effect is more likely to occur because of the wealth effect described by Froot and Stein (1991) rather than the mispricing effect discussed by Shleifer and Vishny (2003).

On the other hand, and consistently with the conclusions of Tables III and IV, international taxation variables, the business environment and the volume of bilateral trade flows remain, from a global point of view, as statistically significant factors that influence the likelihood of firms from a particular country-pair to merge.

Analysing Valuation Differences on Cross-Border Deals Using Deal-Level Panel Data

According to the results obtained and described above, valuation appears to play an important role in determining which firms are likely to merge, especially if they are from different countries. Acquirers tend to be valued relatively highly compared to targets, using prior returns or market-to-book ratios as measures of valuation. The difference in valuation between acquirers and targets appears to occur mainly because to stock market fluctuation effects.

Notwithstanding, the results already presented only consider country-level data. Consequently, the data analyzed in the previous regressions do not control for firm-level factors that are likely to affect the decision to merge.

26

In fact, if the underlying reason for the transaction is to take advantage of valuation differences, then it would be possible to predict which firms will be acquirers or targets using measures of valuation.

Consequently, we consider the sample consisting of all firms involved in a public-to-public cross-border merger and estimate equations predicting whether a particular firm is a target or acquirer.

In this context, we consider, to control for firm-level factors, the subsample of firms for which we have public data on both acquirers and targets. Unfortunately, the subsample is relatively unrepresentative of the overall sample of mergers and acquisitions

Of the 980 cross-border mergers in our sample, only 102 have both public acquirers and targets as well as have data available on firm-level variables that we use to control for other factors that potentially affect mergers. Nonetheless its interest de per si, these deals are not the most typical kind of cross-border mergers and acquisitions.

To estimate the factors that affect the likelihood of a merger, the ideal approach would consider every possible pair of firms that could conceivably merge and estimate the likelihood that any two of them actually do merge. Unfortunately, as the number of possible combinations would be extremely large relative to the number of actual mergers, this approach would not be feasible.

Instead, like Erel, Liao and Weisbach, we adopt two alternative approaches, each of which allows us to infer some conclusions about the factors that could lead one firm to buy another.

Unlike in country-level data, we now consider a sample that includes domestic deals and, therefore, consists of all mergers of publicly traded firms throughout the period under analysis (2001-2010), and then estimate the characteristics of the firms involved with the merger that lead a particular merger to be either cross-border or domestic.

Because the dependent variable is dichotomous, we use logit estimation models that predict whether an observed merger is domestic or cross-border as a function of some deal characteristics. Intuitively, this approach assumes that domestic mergers can be considered as a valid benchmark for understanding the nature of cross-border deals.

27

A different approach, as opposed to country-level data, is that, since at firm-level it was feasible to obtain data on the GAAP ETR of each firm, we used the real GAAP ETR difference between both firms instead of the dummy variable used in the previous tables. All regressions include country-specific dummy variables and standard errors are corrected for clustering of observations at the country level.

The marginal effects of these logit models are presented in Table VI.

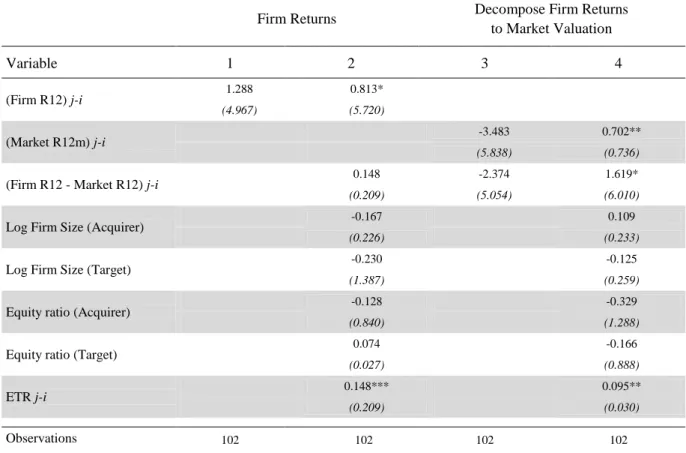

Table VI. Deal-level analysis

Columns 1 and 2 use the difference in the previous year’s firm-level stock returns (Firm R12) between the acquirer (j) and the target (i). Columns 3 and 4 decompose the difference in firm-level stock returns into two components: market returns (Market R12) j-i and firm residual stock returns (Firm R12 - Market R12) j-i. Refer to Section 3 for variable definitions. Country and year fixed effects are included in all regressions. Standard errors are corrected for clustering of observations at the country level and associated t-statistics are in parentheses. The symbols ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

Firm Returns Decompose Firm Returns to Market Valuation Variable 1 2 3 4 (Firm R12) j-i 1.288 0.813* (4.967) (5.720) (Market R12m) j-i -3.483 0.702** (5.838) (0.736)

(Firm R12 - Market R12) j-i 0.148 -2.374 1.619*

(0.209) (5.054) (6.010)

Log Firm Size (Acquirer) -0.167 0.109

(0.226) (0.233)

Log Firm Size (Target) -0.230 -0.125

(1.387) (0.259)

Equity ratio (Acquirer) -0.128 -0.329

(0.840) (1.288)

Equity ratio (Target) 0.074 -0.166

(0.027) (0.888)

ETR j-i 0.148*** 0.095**

(0.209) (0.030)