M

ASTER

O

F

S

CIENCE IN

F

INANCE

M

ASTERS

F

INAL

W

ORK

D

ISSERTATION

B

ASEL

III

L

IQUIDITY

R

ULES

:

A

N

E

MPIRICAL

S

TUDY ON

S

MALL

B

ANKS IN

P

ORTUGAL

MUHAMMAD MHD RADWAN AL SOUFANI

S

UPERVISOR

:

PROF. JOSÈ MANUEL DIAS LOPES

i

Abstract

In 2009-10, the LCR and NSFR standards were lately introduced by Basel III Accord for improving banks’ liquidity management. When full implementation takes place, the LCR and NSFR are expected to bring the banking sector into a developed system that guarantees resilient standing against severe liquidity shocks. This research paper is going to elaborate on the theory behind the LCR and NSFR, and will point out major repercussions accompanying the employment of the two standards. The paper complements the theory with an empirical study on six representative small banks operating in the Portuguese banking sector, with a study period of eight years starting from 2005. In the end, useful conclusions, regarding the sample banks’ activities with respect to the LCR and NSFR, will be presented based on both theory and research.

Keywords: Basel III Accord, Liquidity Standards, Banking Liquidity Management,

ii

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Prof. José Lopes, my academic supervisor, for his great guidance, sincere advices, and showing high level of availability and wonderful cooperation throughout the work. You always made sure that I’m following the right path to get satisfactory results for which I’m very thankful to you, and for the opportunity granted to perform the work under your appreciated supervision.

Much appreciation and gratitude to all my professors at ISEG, our outstanding and remarkable school. It was a wonderful experience to be a student in your classes, where I had the education required to advance smoothly in my academic career.

To my loving, caring and supportive parents, Mr. Radwan and Mrs. Ebtisam: you have always been the persons behind my every step forward in life, thank you for being my inspiration. My heartfelt thanks to my mother not only for all her continued encouragement, but also for crossing long distances to be present beside me in Lisbon while proceeding with the writing of this work.

I’m also grateful to my dear uncle, Mr. Nizar: your incredible support, advices, and attention during my study period are much appreciated.

Finally, to my dear brothers, Hani and Sami, and my wonderful sisters, Rasha, Dima, Lina and Lamis: many thanks to you all for your concerns about my performance, and for always being close to help and providing relief whenever needed despite distances.

iii

List of Abbreviations

ABS: Asset-Backed SecurityASF: Available Stable Funding AUA: Available Unencumbered Asset APB: Portuguese Banking Association

BCBS: Basel Committee on Banking Supervision BIS: Bank for International Settlements

CFP: Contingency Funding Plan EBA: European Banking Authority ECB: European Central Bank HQLA: High-Quality Liquid Asset IMF: International Monetary Fund LB: Liquidity Balance

LCR: Liquidity Coverage Ratio

LTRO: Long-term Refinancing Operation

MiFID: Markets in Financial Instruments Directive MRO: Main Refinancing Operation

NSFR: Net Stable Funding Ratio OBS: Off-Balance Sheet Asset(s) OMO: Open Market Operation PSE: Public Sector Entity Repo: Repurchase Agreement

RMBS: Residential Mortgage-Backed Security RSF: Required Stable Funding

iv

Contents

Abstract ... i

Acknowledgements ... ii

List of Abbreviations ... iii

1. Introduction ... 5

2. Literature Review ... 7

3. Principles for Sound Liquidity Risk Management ... 10

4. Liquidity Coverage Ratio ... 12

4.1. The Standard ... 12 4.2. Assumptions ... 13 4.3. Mechanism ... 16 4.3.1. Supervisory Role ... 19 4.4. Application ... 20 4.4.1. Monitoring Metrics ... 21 4.5. Implications ... 23

5. Net Stable Funding Ratio ... 24

5.1. The Standard ... 25 5.2. Assumptions ... 26 5.3. Mechanism ... 26 5.4. Application ... 28 5.5. Implications ... 29 6. Empirical Study ... 30 6.1. Objective ... 30 6.2. Sampling ... 31 6.3. Procedures ... 32

6.3.1. Annual Stock of HQLA ... 33

6.3.1.1. Annual Stock of HQLA: Levels Approach ... 33

6.3.1.2. Annual Stock of HQLA: Average Approach ... 34

6.4. Graphs Reading ... 36 6.5. Research Findings ... 37 7. Conclusion ... 39 Bibliography ... 41 Appendix 1 ... 43 Appendix 2 ... 50

5

1. Introduction

Banks are arteries of international economies through which money at financial institutions circulates, similar to blood circulating in the human body. The stronger regulations governing the banking system, the higher level of efficiency, prosperity, and sustainability an economy attains.

Mostly through cash and cash-equivalents among other current assets, what defines the liquidity degree of a financial institution is meeting cash outflows on a timely manner without incurring substantial losses (Quingnon, 2014). But what if an institution fails to get cash on time? Or what if unexpected expenses were suffered at the time of raising cash? Therefore, among other practices, liquidity management is a basic practice at banks that has always been subject to study and enhancement.

Shortly after the subprime crisis of 2007-08, the BCBS has introduced Basel III Accord. Important advancement in modern financial regulations is believed to be achieved through the third Accord. Besides vital amendments to the classical capital requirements directive, Basel III has come up with a brand new liquidity regulations framework (ECB, 2013).

Increasing banks liquidity buffers, lowering maturity transformation gaps, harmonized international liquidity management, and mitigating systemic liquidity risk are among the objectives of the liquidity regulations framework. Regulating banks’ liquidity management is also aimed at reducing information asymmetries concerning liquidity risk exposure, and liquidity risk-bearing capacity and therefore, improving the overall performance of the money market as well as the real economy (Ruozi & Ferrari, 2013).

6

For these objectives, two separate but complementary minimum standards were set out for banks’ funding risk. One of which is a short-term requirement known as the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR). The second standard is of longer-term concentration and known as the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR). Internationally active banks are required to comply with these standards following the timeframe specified by regulators (BIS, 2013).

Several challenges banks will have to go through in order to meet the LCR and NSFR. Key impacts associated to the application of these standards are anticipated to be: (1) higher demand to liquid assets; (2) changes to the composition and the size of banks’ balance sheets; (3) shifts in assets funding strategies and thus, shifts in the structure of major accounts; and (4) major influences over the monetary policy implementation (Doran, Kirrane, & Masterson, 2014).

This paper will briefly stresses conclusions of four major research papers regarding the LCR and NSFR liquidity standards, to be presented in the “Literature Review” section. Then the paper continues with a brief elaboration regarding the 2008 liquidity management directive - that is known as the “Sound Principles” - under “Principles for Sound Liquidity Risk Management” section.

Full research concerning the two new liquidity standards are then presented separately under “Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR)” and “Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR)” sections. Main areas of the research are the standards’: (1) definitions; (2) assumptions; (3) mechanisms; (4) applications; and (5) implications.

In relation to the theory that would be presented at first, the paper later advances with a study on six relatively small banks operating in Portugal under “Empirical Study” section. The time horizon considered in the study is eight years starting from 2005. Before

7

and during the transitioning period, the objective of the study is discovering key changes to the sample banks’ activities, as well as testing the annual level of liquid assets holdings of the sample banks.

In the end, based on the theory and the conducted empirical study in this paper, useful conclusions are pointed out under “Conclusion” section.

For illustration, two appendices are included in the end of the paper. “Appendix 1” section is concerned with presenting graphs, while “Appendix 2” is devoted for listing tables.

2. Literature Review

Major conclusions of four studies regarding Basel III Accord liquidity rules will briefly be presented in this section.

In 2010, the BIS released a report that studies the long-term economic impact of stronger capital and liquidity requirements. Results are drawn based on studied data from the US and the Euro area. The analysis considers that banks have fully completed the adaptation to Basel III liquidity and capital rules.

According to the report, the BIS mainly pointed out that improving banks’ capital and liquidity aggregate levels would reward as follows: (1) lower probability of examining a banking crisis at any given year; (2) less severe outputs in case of a banking crisis takes place; and (3) strong banks would be insulated from strains caused by weak troubled banks (BIS, 2010).

In 2011, Giordana and Schumacher have conducted a study regarding the impact of Basel III liquidity regulations (LCR & NSFR) on the bank lending channel given a

8

contractionary monetary policy in the economy. The case under study was Luxembourg. However, authors have also drawn useful conclusions that apply to other European states.

The study states that the LCR and NSFR are vehicles of relevant information for identifying the bank lending channel. In addition, adherence to the new liquidity rules requires deep balance sheet restructuring authors have found—small banks are more drawn to wholesale funding sources, whereas big banks are more attracted to compete on retail deposits. Moreover, regardless of the size, banks that are compliant with the LCR and NSFR are constrained or less able to sustain the bank lending channel given a monetary policy shock in the economy (Giordana & Schumacher, 2011).

In 2013, a research paper regarding the liquidity management, maturity ladder and regulations was introduced by Haan and End. The case study considered 62 Dutch banks, and a study period of almost six years ranging from 2004 to 2010. Back then, Dutch banks were subject to a liquidity-related rule - the liquidity balance (LB) - that resembles the LCR standard proposed by Basel III.

Authors stated in their conclusions that there is a positive correlation between the size of liquid assets holdings with respect to: (1) the volume of liquid liabilities; and (2) cash outflows of different maturities. In this regard, authors elaborated that most of the banks are mapping their cash flows position over a period extending to one year ahead and therefore, regulators should take this into account while applying the LCR standard that considers duration of only one month (Haan & End, 2013).

Another major conclusion referred to by authors is that complying with the LCR standard would require banks to invest more in liquid assets in comparison to the volume of holdings required by the LB and thus, banks will be subject to further balance sheet restructuring. Furthermore, authors lastly found that well-capitalized banks are relatively

9

less relying on liquid assets as a buffer against liquid liabilities compared to other less sizeable banks. Accordingly, authors suggest also to regulators to account for the interaction between capital and liquidity in the formulas of the new liquidity standards to be advised through Basel III Accord (Haan & End, 2013).

In 2013, the ECB published an article regarding liquidity regulations and monetary policy implementation. The article explains Basel III liquidity standards, and illustrates the interaction between the application of these standards and monetary policy operations through a study conducted in the Euro area.

According to the article, the study shows that the LCR and NSFR would influence bank’s management of their business activities. In detail, the ECB argues that liquidity regulations will positively affect the functioning of the money market through: (1) reducing information asymmetries in the market concerning liquidity risk exposure and liquidity risk-bearing capacity; and (2) reducing the market risk premium (ECB, 2013).

Possible appealing strategy for banks to comply with the LCR is through increasing the reliance on central bank funding with non-HQLA posted collateral the ECB has pointed out. However, this conclusion seems to be more literature than truth based on a research that has been done by the ECB in this regard—variations in using HQLA1 for collateral postings to central banks funding are roughly increasing since the subprime crisis of 2007-08 until 2012 as observed in the research2 (ECB, 2013).

1 All classes of the stock of HQLA are to be taken into consideration including Level 1, Level 2A, and

Level 2B. For illustration, review figure number “3” in “Appendix 1” section.

10

3. Principles for Sound Liquidity Risk Management

This section will briefly discuss the BIS report “Principles for Sound Liquidity Risk Management”, that is also known as the “Sound Principles3” guidance, revised and published in 2008.

The financial crisis of 2007-08 revealed many pitfalls in the liquidity risk management of the banking sector. The reversal in market conditions had proven how liquidity can quickly fade away for an extended period of time, showing that even well capitalized banks are not immune against liquidity shocks (Ruozi & Ferrari, 2013).

In this regard, regulators pointed out crucial areas that were not accounted for in troubled banks prior to the market turmoil. Exposed regulatory areas included the failure of accounting for: (1) contingent obligations; (2) individual products and business lines; and (3) effective stress testing among others (BIS, 2008).

In response, the BCBS Committee introduced in 2008 a newer version of the 2000 guidance regarding liquidity risk management, the “Sound Principles”. According to these revised principles, effective internal procedures including regular reviews and evaluations are in fact the remedy to tackle exposures to liquidity risk (Ruozi & Ferrari, 2013). Many key areas have been highlighted and brought under study, adding three new principles to the previous list of fourteen in the Sound Principles (BIS, 2008).

Major areas that have been reconsidered and discussed in the Sound Principles directive of 2008 are as follows (BIS, 2008):

Establishing liquidity risk tolerance plans;

Maintaining sufficient level of liquidity through cushion of liquid assets;

3 The Sound Principles guidance is available through the following link:

11

Allocating liquidity costs, benefits, and risks to all significant business activities;

Identifying and measuring the full range of liquidity risks, including contingent liquidity risks;

Conducting severe stress testing scenarios;

Setting up robust and operational contingency funding plans4 (CFP);

Managing intraday liquidity risk and collateral; and

Promoting public disclosure to enhance the market discipline.

The guidance for supervisors has also been taken into consideration and augmented substantially. The Sound Principles stresses the importance of the supervisory role in terms of assessing the adequacy of the liquidity risk management framework, and illustrated steps to be taken if deemed necessary to address deficiencies (Ruozi & Ferrari, 2013).

The implementation of the Sound Principles extends to cover all types of operating banks. Regulators had set the revised guidance into effect promptly after its publication in 2008. Nevertheless, the application will be function of the size, the nature and complexity of business of any bank wishing to comply with the directive (BIS, 2008).

Major implications of the Sound Principles in the banking system would include: (1) harmonized approach to supervision of liquidity related risks; (2) more stable banking environment; (3) reducing heterogeneity in the treatment of liquidity-related issues (Doran, Kirrane, & Masterson, 2014).

4 Contingency funding plans (CFPs) define strategies for addressing liquidity shortfalls due to both firm and market-specific stressed conditions (BIS, 2013).

12

4. Liquidity Coverage Ratio

This section is devoted to elaborate on the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) standard, its assumptions, mechanism, application procedures, and implications. Please be noted that the section is mainly based on the BIS report: “Liquidity Coverage Ratio and Liquidity Risk Monitoring Tools5”, released in January 2013.

The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) is an essential product of Basel III Accord among a number of newly-born measures. It is a key reform that has been mainly introduced to establish a minimum level of liquidity for internationally active banks in particular, as well as locally operating retail banks (BIS, 2013).

The supervisory approach to liquidity risk extended to include the LCR standard. In essence, LCR is a ratio that promotes for short-term resilience of banks’ liquidity risk profile. Therefore, the likelihood of banks to fail or to call on rescue programs during financial crises will remarkably decrease (BIS, 2013).

4.1. The Standard

According to the LCR standard, banks are required to keep a sufficient level of unencumbered high-quality liquid assets (HQLAs) to meet cash outflows demand for 30 days stress scenario. The objective is to build a firewall against shocks resulted from financial and economic disruptions and thus, reducing the likelihood of examining contagion-effects between the financial sector and the real economy. Nevertheless, it is important to know that the LCR - on its own - is insufficient to cover all aspects of a bank’s liquidity risk profile (BIS, 2013).

13

The LCR standard is based on two main components: (1) the value of the stock of HQLA given the stress scenario; and (2) the total net stressed cash outflows calculated in accordance with the stress scenario liquidity needs. Consequently, the value of the stock of HQLA will have to amount to at least 100% against the net cash outflow (Quingnon, 2014).

In keeping with the definition of the standard, LCR has been introduced as follows (BIS, 2013):

𝑳𝑪𝑹 = 𝑺𝒕𝒐𝒄𝒌 𝒐𝒇 𝑯𝑸𝑳𝑨

𝑻𝒐𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝒔𝒕𝒓𝒆𝒔𝒔𝒆𝒅 𝒏𝒆𝒕 𝒄𝒂𝒔𝒉 𝒐𝒖𝒕𝒇𝒍𝒐𝒘𝒔 𝒐𝒗𝒆𝒓 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝒏𝒆𝒙𝒕 𝟑𝟎 𝒄𝒂𝒍𝒆𝒏𝒅𝒂𝒓 𝒅𝒂𝒚𝒔≥ 𝟏𝟎𝟎%

(1)

The nominator of equation number “1” is the market value of the stock of HQLA, whereas the denominator represents the net stressed cash outflows anticipated to be drawn out over the subsequent 30 calendar days (BIS, 2013). Clearly, the major drive of the LCR standard is the denominator and thus, the size of liquidity reserve requirement is function of: (1) the size of cash outflows; and (2) the time horizon involved in the calculation (30 subsequent calendar days) (BIS, 2013).

In principle, banks are also required to reflect any cash inflows and outflows mismatches in their calculations for the minimum level of the stock of HQLA they need to keep. Therefore, the minimum level of HQLA holdings is subject to daily adjustment in line with the risk profile of the bank, and the market value of the stock of HQLA (Schmitz, 2013).

4.2. Assumptions

During the subprime crisis of 2007-08, financial markets suffered of severe shocks at many levels. For that reason, regulators of the banking system have come to realize the

14

nature of possible consequences under such hard market conditions. Consequently, the work on developing the stress scenario extended to incorporate almost all aspects of practicalities that a bank would need to go through for a period of a whole month. The defined scenario assumes major outcomes resulted from firm-specific and market-wide shocks, and does not represent the worst scenario possible (BIS, 2013).

Main underlying assumptions regarding outcomes defined by the stress scenario are as follows (BIS, 2013):

Bank run on retail deposits;

Partial loss of unsecured and wholesale funding6 capacity;

Partial loss of secured short-term financing with certain collateral and counterparties;

Additional contractual outflows due to downgrade in the bank’s public credit rating, including collateral posting requirements;

Increased market volatility that would impact the positions in derivatives, and thereby collateral haircuts or additional postings will be required increasing the liquidity needs;

Draws on committed but unused credit and liquidity facilities the bank has provided to its clients; and

Possible buying back of debt or non-contractual obligations in the interest of mitigating reputational risk.

15

Besides the stress scenario assumption, in order to assure a minimum level of HQLA holdings, regulators have also introduced a constraint to be applied to the amount of cash inflows of banks, so that negative net cash outflows is guaranteed (BIS, 2013).

𝑻𝒐𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝒄𝒂𝒔𝒉 𝒊𝒏𝒇𝒍𝒐𝒘𝒔

𝑻𝒐𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝒄𝒂𝒔𝒉 𝒐𝒖𝒕𝒇𝒍𝒐𝒘𝒔≤ 𝟕𝟓%

(2)

𝑻𝒐𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝒔𝒕𝒓𝒆𝒔𝒔𝒆𝒅 𝒏𝒆𝒕 𝒄𝒂𝒔𝒉 𝒐𝒖𝒕𝒇𝒍𝒐𝒘𝒔 = 𝑻𝒐𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝒔𝒕𝒓𝒆𝒔𝒔𝒆𝒅 𝒄𝒂𝒔𝒉 𝒐𝒖𝒕𝒇𝒍𝒐𝒘𝒔 − 𝑻𝒐𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝒓𝒆𝒔𝒕𝒓𝒊𝒄𝒕𝒆𝒅 𝒄𝒂𝒔𝒉 𝒊𝒏𝒇𝒍𝒐𝒘𝒔

(3)

As shown above in formulas number “2” and “3”, total cash inflows should not cover more than 75% of the exposure of total stressed cash outflows (only for the LCR standard calculation).

For an asset to be classified among the basket of HQLAs, a number of qualifications must be verified. Essential qualifying properties of assets include: (1) high marketability in private markets (even during stress periods); and (2) defined as eligible by the central bank (EBA, 2013).

Main characteristics of HQLAs are as follows (BIS, 2013):

Low risk: high credit rating and low degree of subordination of the issuer;

Accurate valuation: standardization, homogeneity, and simplicity of structures;

Low correlation with risky assets;

Listed on a recognizable exchange;

Availability at active and sizable market(s): including repo7 markets;

Low volatility;

16

High quality: demonstrating marketability even under unfavorable market conditions; and

Unencumbered: free of legal, regulatory, contractual or other restrictions that might constrain trading, transferring or assigning the asset.

4.3. Mechanism

Similar to the traditional “coverage ratio” methodology in banks, the LCR is an internal tool to assess liquidity risk exposure. Total cash outflows during a period of stressed conditions lasting for one month should be calculated on a daily basis. Hence, a stock of HQLA should be raised as a buffer against that liquidity exposure8 (BIS, 2013).

In absence of a financial stress, the LCR standard requires at least 100% level of the stock of HQLA—the market value of the holdings of HQLA must be equal to the total net cash outflow on an ongoing basis (Vahey & Oppenheimer, 2014). Banks, however, are permitted to fall below 100% level only during periods of financial stress. Therefore, if deemed necessary, a bank may call on its stock of HQLA to meet liquidity needs (BIS, 2013).

Even though disruption periods grant exceptions, unbalanced LCR levels will still be subject to supervisory assessment and judgment which might impose further restrictive standards in line with circumstances, the bank’s risk profile, and other macroeconomic and macro-financial implications (BIS, 2013).

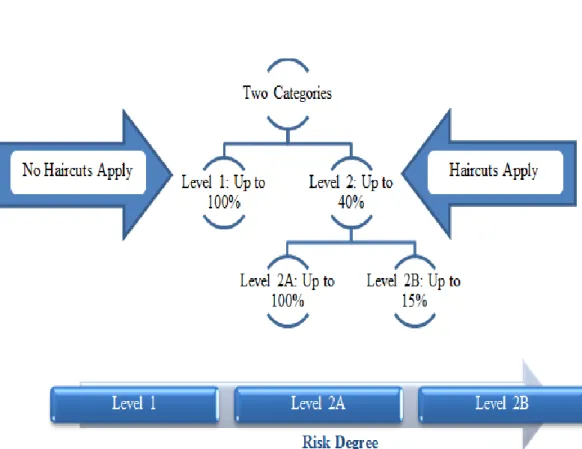

In compliance with the LCR standard, two categories of assets are allowed to participate in the composition of the stock of HQLA. These two categories have been defined in terms of the risk degree associated to their corresponding assets. Furthermore,

17

pre-stated haircuts will apply to the market value of liquid assets (only for the LCR calculation) with respect to the degree of risk of each asset (BIS, 2013). However, the degree of participation of each category’s assets is also subject to restrictions while comprising the stock of HQLA9 (Ruozi & Ferrari, 2013).

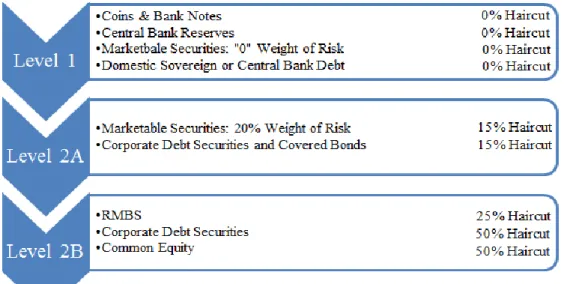

The first category is referred to as “Level 1” assets. Category Level 1 assets are not only exempted of any preliminary haircuts on their market value, but also allowed to comprise 100% of the stock of the HQLA. Level 1 assets include: (1) coins and banknotes; (2) central bank reserve; (3) marketable securities10; and (4) sovereign and/or central banks debt (BIS, 2013).

On the other hand, the second category is referred to as “Level 2”. Level 2 assets are subject to a cap of only 40% as a degree of participation in the stock of HQLA composition, and to be calculated after applying haircuts on its current market value. In addition, the second category has a classification of Level 2A and Level 2B. For each classification, there is an inclusive predefined restriction on the degree of participation in the composition of the stock of HQLA—Level 2A is allowed to comprise the whole 40%, whereas Level 2B is subject to 15% cap inclusively (BIS, 2013).

As for Level 2A assets, 15% haircuts apply to their current market value. Level 2A assets include: (1) marketable securities11; and (2) corporate debt securities and covered bonds (BIS, 2013).

9 For illustration, review figures number “2” and “3” in “Appendix 1” section.

10 Including bonds issued by sovereigns, central banks, PSEs, BIS, IMF, ECB and European Community

with 0 weight of risk according to Basel II methodology (BIS, 2013).

11 Including bonds issued by sovereigns, central banks, PSEs, BIS, IMF, ECB and European Community

18

Higher degree of risk is associating Level 2B assets which include: (1) RMBS—25% haircut; (2) corporate debt securities—50% haircut; and (3) common equity shares—50% haircut (EBA, 2013).

Regulators have further imposed several operational requirements on the stock of HQLA. These requirements shall ensure and demonstrate a bank’s ability for immediate outright sale or repo. In this context, banks must periodically trade a representative portion of the stock of HQLA in order to test accessibility to the market, liquidity-generating capacity, availability of the assets, and to prevent negative signaling during periods of real stress in the economy (BIS, 2013).

In addition, banks are prohibited to pledge any asset belongs to the stock of HQLA for securitization, collateralization or credit-enhancing purposes. Likewise, the stock of HQLA should not be partially or entirely designated to cover operational costs (BIS, 2013).

For better application, banks are also required to run their own stress tests to assess the level of liquidity they probably would need it beyond the minimum level required by the LCR with time horizons longer than a month. In this regard, internal customizable stress scenarios are required; such tests are expected to be more compatible and aligned with the bank’s major business activities (BIS, 2013). Furthermore, stress testing should incorporate scenario and sensitivity analyses to hedge against any anticipated extreme and adverse conditions (Wiszniowski, 2010). It is also important to know that these internal stress testing procedures are subject to periodic supervisory control (BIS, 2013).

Taking into consideration intraday liquidity needs, the LCR standard does not cover such expenses, nor account for it. Therefore, banks should maintain an active

19

management over intraday liquidity positions and their associated risk regularly12 (BIS, 2013).

Other considerations include the basket of currencies involved in a bank’s transactions. The bank should be aware of the composition of its stock of HQLA—it must meet its liquidity needs in each currency. Under stressed conditions, currency swaps arrangement tend to be harder to manage at the expense of urgent needs. Through timely reporting mechanism, the bank and its supervisors can keep track of any currency mismatches at an early stage and thus, reducing the exchange rate risk related to the LCR standard (BIS, 2013).

Regulators have also introduced the concept of diversification, and recommended the stock of HQLA to be well-diversified. Although the stock of HQLA is assumed to be highly marketable, an unexpected shock might incur tolls on an asset class more than others. Accordingly, dynamic diversification among available categories is of importance while comprising the stock of HQLA (BIS, 2013).

4.3.1. Supervisory Role

According to the LCR standard, supervisors are responsible to govern situations of disruptions in which their response will define the extent of flexibility allowed regarding the LCR level. In specific, supervisors are required to judge, assess, and count for macroeconomic and macro-financial repercussions in their decisions. Therefore, the supervisory role is of great sensitivity taking into consideration procyclicality within an economy. It should also be noted that supervisory responses should be consistent with prudential framework of the Basel III Accord (BIS, 2013).

12 For further information regarding intraday liquidity risk management, review the Sound Principles

guidance of 2008, published by the BIS and available through the following link:

20

Main responsibilities of supervisors are as follows (BIS, 2013):

Assessing conditions of financial disruptions at an early stage to address potential liquidity risk;

Planning responses proportionally to drivers, magnitude, duration, and frequency of any reported shortfall in the LCR standard;

Taking into considerations firm and market-specific factors, as well as domestic and global frameworks and conditions to determine possible response;

Demanding certain actions by a bank to reduce its liquidity risk exposure, strengthen its overall liquidity risk management, and/or to improve its contingency funding plan; and

Discussing measures that can restore liquidity levels with respect to a defined timeframe to mitigate the stress on the bank.

4.4. Application

The frequency of reporting the LCR is flexible given regular market conditions yet, it becomes highly stringent during periods of stress in the economy. For a bank to be compliant with the LCR standard, at least a monthly report regarding the LCR level has to be submitted to supervisors. However, authorities encourage and recommend reporting on a weekly basis, or even daily if possible. Nevertheless, the LCR standard oblige banks to daily reporting during stressed periods. Banks are also required to notify supervisors regarding any recognized or anticipated shortfalls in the LCR standard regardless of market conditions (BIS, 2013).

Due to strains in the banking system, coupled with major implementation requirements and implications, regulators decided to carefully introduce the LCR

21

following a phase-in approach13. As planned, the LCR should take effect on 1 January 2015 with a minimum requirement of 60%. From 2015 onward, the LCR minimum requirement will grow gradually 10% each year until it is fully implemented by the start of 2019 (Schuster, Kövener, & Matthes, 2013).

4.4.1. Monitoring Metrics

Although the LCR standard is sufficient to identify relevant factors of short-term liquidity risk, yet, it does not mirror and account for other available factors. For that reason, and in order to maintain a sound workflow of the LCR, regulators have also introduced a number of metrics as monitoring and complementary tools (BIS, 2013).

According to the BCBS Committee, the metrics are as follows: (1) contractual maturity mismatch; (2) concentration of funding; (3) available unencumbered assets; (4) LCR by significant currency; and (5) market-related monitoring tools (BIS, 2013).

Essentially, and along with the LCR, these metrics should provide assistance to supervisors in assessing the liquidity risk profile of a given bank. They should be considered as a supplement to the framework of the LCR standard, which will promote for better capturing and understanding of all relevant information related to the LCR standard (BIS, 2013).

As for the “contractual maturity mismatch” metric, it is developed to highlight the realized gaps between cash inflows and cash outflows due to duration mismatching of contractual commitments. All gaps should be defined with respect to a pre-stated frequency, and within a specified timeframe. In principle, the metric accounts for the fund

22

that would have to be raised in case all cash outflows will be realized at the earliest date possible (BIS, 2013).

Considering difficulties regarding the access to major sources of fund, regulators did introduce “concentration of funding” as the second metric. This metric is devoted to identify main wholesale sources of fund. The reason why behind such a measure is the exposure to liquidity issues in situations where access to these sources of fund is no longer available. In response, this metric encourages banks to diversify their funding sources, and to test accessibility to such sources regularly with respect to a periodic plan to be set for that purpose (BIS, 2013).

The third metric is concerned with quantifying and providing relevant information regarding “available unencumbered assets (AUAs)” at banks’ disposal. Such information should include characteristics, currency denomination, and location of these AUAs. However, the importance of AUAs comes from the possibility of using them as collateral to raise additional HQLA if deemed necessary (BIS, 2013).

The “LCR by significant currency” is the fourth metric, and has been designed to promote better currency matching related to the LCR standard. In spite that the LCR is required to be computed in a one single currency, this metric will permit tracking down the value of the LCR against major international currencies. Accordingly, this metric would facilitate the supervisory role regarding foreign exchange risk related to the LCR standard (BIS, 2013).

The last metric is the “market-related monitoring tools”. Through screening the market data, supervisors would be able to anticipate potential liquidity difficulties at the earliest possible. Such technique allows for precaution procedures to take place prior to an escalation in the market conditions. Information that should be taken into consideration

23

includes: (1) market-wide level; (2) financial sector level; and (3) bank-specific level (BIS, 2013).

4.5. Implications

It is necessary for a bank to define a feasible strategy in order to meet the LCR standard. Banks would have to choose among three main approaches to fund acquisitions of HQLA: (1) deleveraging14; (2) borrowings; and (3) deposits. Banks may choose one or a combination of these strategies. However, the decision to determine which approach to adopt is difficult, knowing that each technique has its pros and cons. It must be noted that from “the least costly” point of view, the last option seems appealing—competing for retail demand deposits (Hartlage, 2013).

Accordingly, it is conceivable that the implementation of the LCR standard will require several adjustments to the composition of banks’ balance sheets. Through looking at the assets side, the LCR implies investing heavier in HQLAs in order to satisfy the standard. Hence, the demand of Level 1, Level 2A, and Level 2B assets would significantly increase and thus, prices of these assets will be subject to upward pressure. Similarly, the increased demand to HQLA holdings will have an influence over the supply of these assets and thus, increasing the volatility in the repo markets (Doran, Kirrane, & Masterson, 2014).

Following conclusions stated above, the employment of the LCR standard will certainly have major influences over the monetary policy implementation; the size and participation in the money market in particular. Such repercussions resulted from the LCR can briefly be indicated as follows: (1) discouraging banks to lend and/or borrow in the

24

unsecured money market—shifting the demand from MROs to LTROs15; (2) increasing the participation of banks in OMOs—banks under pressure will bid more aggressively; and (3) increasing the spread between interest rates of the secured and the unsecured money markets (Schmitz, 2013).

Therefore, during stressed periods, the binding regulatory LCR requirement has a negative effect on the interbank money market. Nevertheless, the LCR promotes to stability and less vulnerability in the banking system (BIS, 2013). Moreover, to some extent, the negative impact of the LCR on the unsecured money market is intentional. The reason why is aligned with the nature of this market which was a major source of contingent liquidity risk during the crisis of 2007-08 (Bonner & Eijffinger, 2013).

In the same regard, regulators have introduced in January 2014 a number of amendments to mitigate consequences resulted from the LCR over the monetary policy. These amendments included the introduction of committed liquidity facilities by central banks in the definition of Level 2B assets and therefore, increasing the basket of defined liquid assets that are supposed to be considered eligible at national central banks (Doran, Kirrane, & Masterson, 2014).

5. Net Stable Funding Ratio

This section studies the Net Stable Funding Ratio standard, its assumptions, mechanism, application, and implications. Please be noted that the section is mainly based on the following report “Basel III: The Net Stable Funding Ratio16”, published by the BIS

in January 2014.

15 Banks would have to collateralize their LTROs with “liquid assets” of less quality in comparison to

HQLAs and thus, increasing the risk exposure (Schmitz, 2013).

25

Among others, the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) is a key reform introduced by the BCBS Committee in its recent contribution of Basel III Accord. Essentially, the NSFR is a complementary standard to LCR, and its objective is achieving a sufficient liquidity standing in the long-run with a time horizon of one year (Dietrich, Hess, & Wanzenried, 2014).

Taking the composition of assets and off-balance sheet activities into consideration, the NSFR aims at securing stable funding sources in order to mitigate the risk of potential future funding stress. Accordingly, in case of a disruption in the economy, the influence of the funding sources over the liquidity position would significantly be minimized (Ruozi & Ferrari, 2013).

5.1. The Standard

The NSFR is function of two major components: (1) the available stable funding (ASF); and (2) the required stable funding (RSF). Regulators have defined the NSFR standard minimum requirement as follows (BIS, 2014):

𝑨𝒗𝒂𝒊𝒍𝒂𝒃𝒍𝒆 𝒂𝒎𝒐𝒖𝒏𝒕 𝒐𝒇 𝒔𝒕𝒂𝒃𝒍𝒆 𝒇𝒖𝒏𝒅𝒊𝒏𝒈

𝑹𝒆𝒒𝒖𝒊𝒓𝒆𝒅 𝒂𝒎𝒐𝒖𝒏𝒕 𝒐𝒇 𝒔𝒕𝒂𝒃𝒍𝒆 𝒇𝒖𝒏𝒅𝒊𝒏𝒈≥ 𝟏𝟎𝟎%

(4)

To comply with the standard, and with respect to its time horizon of one year, banks’ ASF would need to sum up to at least 100% vis-à-vis their corresponding RSF on an ongoing basis. Therefore, the NSFR would push banks toward enhancing the mapping of their cash streams (BIS, 2014).

As shown above in formula number “4”, the larger the denominator (RSF), the harder the task becomes for a bank to meet the NSFR standard. On contrary, large share of ASF of a bank in comparison to its RSF grants stronger liquidity standing (BIS, 2014).

26

5.2. Assumptions

Regulators have standardized the NSFR based on the degree of stability of the funding sources and the liquidity of assets (BIS, 2014).

Considering liabilities side, the NSFR standard assumes that the longer the term of a liability, the more stable it is. Likewise, looking at short-term liabilities (less or equal to one year), core deposits are assumed to be more stable than wholesale funding operations (BIS, 2014).

On the other hand, considering assets, there are four main criteria would have to be taken into consideration: (1) some proportions of credit should be kept available to be loaned and circulated into the real economy; (2) significant portion of loans with maturity exceeding one year could be rolled over to preserve major customers; (3) short-term assets with maturity less or equal to one year are assumed not to be extended; and (4) high quality assets do not require 100% stable funding (BIS, 2014).

5.3. Mechanism

Basically, regulators have designed the NSFR standard in an attempt to create better maturity matching between bank’s cash inflows (from liabilities and equities) and cash outflows (for assets and OBS items) and thus, improving the funding risk profiles of banks. Two main concepts are therefore introduced in the formation of the NSFR17: (1) the available stable funding (ASF); and (2) the required stable funding (RSF) (BIS, 2014).

What does the ASF represent? ASF of a financial institution is its stock of capital and liabilities put together, which are in fact the institution’s sources of funding. According to the definition of the NSFR standard, the stock of capital and liabilities mostly refers to

27

the following financial instruments18: (1) equity; (2) hybrid and debt instruments; (3) deposits; and (4) wholesale funding. It should be noted that ASF of a bank is function of the degree of stability of that source of fund (BIS, 2014).

The amount of the ASF to be calculated is not only based on the carrying value of capital and liabilities, but also on their corresponding degree of relative stability. The term “relative stability” takes into consideration the maturity of the funding sources, as well as the tendency of the fund providers to claim their money back. For that reason, regulators have defined ASF percentage factors. Accordingly, all funding sources were distributed among lists of five categories19 to simplify the stability factoring process. It should be noted that the higher the ASF factor of an item, the greater the stability of the item under study (BIS, 2014).

As a result, the sum of the weighted amounts of each funding source carrying value multiplied by its corresponding ASF factor is the NSFR nominator—available amount of stable funding (ASF) (BIS, 2014).

Moving to RSF, it implies that each asset and off-balance sheet (OBS) item should be boosted through defining an amount of stable funding that is required to back it up. Nevertheless, the amount of RSF is to be determined based on the degree of liquidity of the various types of assets and OBS activities (BIS, 2014).

Following the same rationale of ASF, regulators have also introduced RSF percentage factors to quantify the amount of a particular asset that would have to be funded for three main reasons: (1) the asset is assumed to be rolled over at maturity; (2) the asset is assumed to be non-collateralizable in secured borrowing transactions; and (3) the asset is

18 For illustration, review figure number “5” in “Appendix 1” section. 19 For illustration, review table number “2” in “Appendix 2” section.

28

either partially or entirely illiquid20. As the RSF factor increases, the liquidity risk of the asset under study increases (BIS, 2014).

Major assets are therefore distributed among seven categories to standardize the factoring process21. Considering OBS exposures, they have been categorized with respect

to whether they are credit facilities granted by the bank, or on the other hand they are contingent funding plans22 (BIS, 2014).

Consequently, the RSF is calculated through taking the sum of the product of each asset carrying value times its corresponding RSF factor, plus the sum of the product of each OBS commitment carrying value times its corresponding RSF factor (BIS, 2014).

Similar to the LCR standard, the NSFR is also subject to supervisory assessment. In line with the degree of compliance, supervisors may impose further restrictive measures to reflect the bank’s funding risk profile more thoroughly (BIS, 2014).

5.4. Application

The NSFR would have to be calculated in the main currency of reference to the bank applying the standard. Moreover, all banks are obligated to report the level of the NSFR at least quarterly unless another frequency of reporting has been advised by supervisors (Ruozi & Ferrari, 2013).

Because the implementation of the NSFR standard carries significant liquidity structuring changes to the banking system, it has been determined to be valid as a minimum requirement by January 1, 2018 (BIS, 2014). Extended period of time for

20 An asset is illiquid when it could not be monetized through sale at a time of need without incurring

significant expense.

21 For illustration, review table number “4” in “Appendix 2” section. 22 For illustration, review table number “3” in “Appendix 2” section.

29

testing and observation is therefore still available to regulators to introduce revisions and reforms if any deemed necessary (Ruozi & Ferrari, 2013).

5.5. Implications

Fitting the requirements of the NSFR standard will require banks to go through several structural changes to the composition of their balance sheets in order to meet and to optimize the standard23—maximizing the amount of ASF and minimizing the amount of RSF (King, 2013). Consequently, banks’ new orientations would consider: (1) increasing reliance on medium to long-term funding sources; and (2) reducing long-term assets. It should be noted that medium to long-term liabilities are more costly, but at the same time assumed to be highly stable. Moreover, medium to short-term assets are less profitable, but on the other hand they are perceived to have higher degrees of liquidity (Ruozi & Ferrari, 2013).

Banks’ traditional function of maturity transformation is therefore no longer as flexible as it has been prior to the adoption of the NSFR standard. Maturity gaps between assets and liabilities are expected to be remarkably reduced (Dietrich, Hess, & Wanzenried, 2014).

In this regard, many banks may consider shrinking their balance sheet in an attempt to modify the composition and/or maturity of their assets (loans in particular) and thus, reducing banks’ net interest margin (King, 2013). On the other hand, stable medium to long-term funding will require lower risk premiums. As a result, benefits of lower borrowing costs are assumed to be offsetting if not outweighing the reduced profitability in the long-run (Ruozi & Ferrari, 2013).

30

In addition, due to the lack of experience with liquidity regulations, it is likely that banks may involve in abnormal risky activities. Engagement in riskier activities would result in less credit creation and market making in the real economy (King, 2013).

6. Empirical Study

In this section, and in line to the liquidity standards presented earlier, an empirical study on small banks operating in the Portuguese banking sector is going to be presented.

6.1. Objective

Objectives of the study are as follows:

Testing major changes to the composition of the sample banks’ balance sheets (assets, liabilities and capital);

Testing variations of the demand level for liquid assets;

Studying annual variations in the level of HQLA for the sample banks; and

Observing shifts in the sample banks’ funding strategies over the study period.

This study does not achieve the goal of calculating the LCR and NSFR standards for the sample banks, as such computations require confidential data from the sample banks that are not for shared with students, nor available at the Source Database (APB).

However, through the aforementioned objectives, the research findings are going to be projected to: (1) major implications of the LCR and NSFR standards indicated earlier in their theoretical parts; and (2) main conclusions presented in the “Literature Review” section.

31

6.2. Sampling

The sampling has included six relatively small banks operating in Portugal based on data retrieved from the Portuguese Banking Association (APB)24. The year of selection is 2005, and the selection criterion is a capital ranging from €75 to €200 million.

Primarily, data that has been retrieved are the non-consolidated balance sheets of the sample banks, and it has been studied over a time horizon of eight years extending from 2005 to 2012.

It is important to note that the study covers five years before the announcement of Basel III, and three years during the transitioning period (after the announcement of Basel III) until later in 2018-2019 full implementation of the new liquidity standards would take place.

According to the selection condition, several banks were excluded due to lack of fully available financial reports at the Source Database over the entire study period.

The list of selected banks is as follows:

Banif SGPS;

BBVA;

BII;

CBI;

FINI Banco; and

Popular.

32

6.3. Procedures

Published financial reports retrieved from the Source (APB) followed different layouts in presenting major accounts details. Therefore, the first step was to consolidate and harmonize the design of all reports into one common layout. The non-consolidated template of the sample banks’ balance sheets presented in the Excel file demonstrates the common layout.

The second procedure was preparing common size balance sheets of the sample banks that would help studying major accounts tendencies and evolution over the study period. This has been done through standardizing all line items of balance sheets as a percentage of each bank’s total assets over the study period.

Based on common size balance sheets, evolution and tendencies of major accounts were studied to draw conclusions on the sample banks’ balance sheets structural changes. Major accounts studied included current assets, fixed assets, current liabilities, long-term liabilities, and capital. In addition, two liquidity-related ratios had been computed to test changes over the study period.

For the NSFR objective of reducing structural mismatches between assets and liabilities, the “current ratio” was introduced to check whether the sample banks were able to improve their exposure after the introduction of Basel III. The current ratio is calculated as follows:

𝑪𝒖𝒓𝒓𝒆𝒏𝒕 𝑹𝒂𝒕𝒊𝒐 = 𝑪𝒖𝒓𝒓𝒆𝒏𝒕 𝑨𝒔𝒔𝒆𝒕𝒔 𝑪𝒖𝒓𝒓𝒆𝒏𝒕 𝑳𝒊𝒂𝒃𝒊𝒍𝒊𝒕𝒊𝒆𝒔

33

It was mentioned in the “LCR” section, deleveraging is a strategy among others to finance HQLA’s holdings. To test whether the sample banks’ have relied on deleveraging, “total debt ratio” analysis was applied. The total debt ratio is calculated as follows:

𝑻𝒐𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝑫𝒆𝒃𝒕 =𝑻𝒐𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝑨𝒔𝒔𝒆𝒕𝒔 − 𝑻𝒐𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝑬𝒒𝒖𝒊𝒕𝒚 𝑻𝒐𝒕𝒂𝒍 𝑨𝒔𝒔𝒆𝒕𝒔

(6)

Please be noted that most accounts balances were studied based on their gross values and not the net values (disregarding provisions and/or impairments). Therefore, it is expected to observe figures growing above 100% in terms of the corresponding bank’s total assets at some periods.

6.3.1. Annual Stock of HQLA

The stock of HQLA has been computed for the sample banks over the study period on a yearly basis. For the analysis robustness, HQLA computation tracked down two approaches in approximating the annual level. Net value of annual HQLA has then been presented in percentage of total assets for the two approaches.

Please be noted that most liquid assets balances were studied based on their gross values and not net values (disregarding provisions and/or impairments). Therefore, it is expected to observe figures growing above 100% in terms of the corresponding bank’s total assets at some periods.

6.3.1.1. Annual Stock of HQLA: Levels Approach

In the first approach, the multi-level asset types of the stock of HQLA defined by Basel III Accord has been taken into consideration, in addition to the corresponding haircuts related to each level25. However, due to lack of such full classifications of

34

reported data from the Source Database, it was necessary to draw assumptions regarding current assets classifications.

Assumptions regarding liquid assets’ classes are as follows:

“Cash and deposits at central banks” are equivalent to “cash” and “central bank reserve” of “Level 1” assets;

“Financial assets held for trading” and “assets with repurchase agreements” are equivalent to “marketable securities with 20% weight of risk” that belong to “Level 2A” assets;

“Held to maturity investments” are equivalent to “bonds & corporate debt securities” of “Level 2B” assets;

“Financial assets held for sale” are equivalent to “common equity” belongs to “Level 2B” assets; and

“Hedging derivatives” are equivalent to “RMBS” that are part of “Level 2B” assets.

The yearly net HQLA level is then calculated through taking the sum of all assets stated above after subtracting corresponding haircuts26 that vary with respect to the asset class according to Basel III LCR standard.

For simplification, the yearly level of HQLA have been standardized in terms of the sample banks’ total assets to test variations over the study period.

6.3.1.2. Annual Stock of HQLA: Average Approach

In this approach, and also due to lack of full classifications of reported data from the Source Database, the sum of the gross values of all liquid assets - that belong to the basket

35

of HQLA defined by Basel III LCR standard - will be subject to a common average haircut. The annual HQLA level is then standardized against total assets of the sample banks to study variations.

Following the same assumptions of the “Level” approach, studied liquid assets are as follows:

Cash and deposits at central banks;

Financial assets held for trading;

Assets with repurchase agreements;

Held to maturity investments;

Financial assets held for sale; and

Hedging Derivatives.

Based on haircuts introduced by the LCR standard, the average haircut is to be determined through taking the weighted average value of all haircuts percentages applied to the three different categories of liquid assets27.

The average haircut is calculated as follows:

𝑨𝒗𝒆𝒓𝒂𝒈𝒆 𝑯𝒂𝒊𝒓𝒄𝒖𝒕 = (𝟏𝟓% + 𝟏𝟓%

𝟐 ) + (

𝟓𝟎% + 𝟓𝟎% + 𝟐𝟓%

𝟑 ) = 𝟓𝟕%

(7)

The yearly net HQLA level is then calculated through deducting the average common haircut from each bank’s sum of its liquid assets.

36

6.4. Graphs Reading

Please be noted that all graphs produced through the empirical study are listed in “Appendix 1” section.

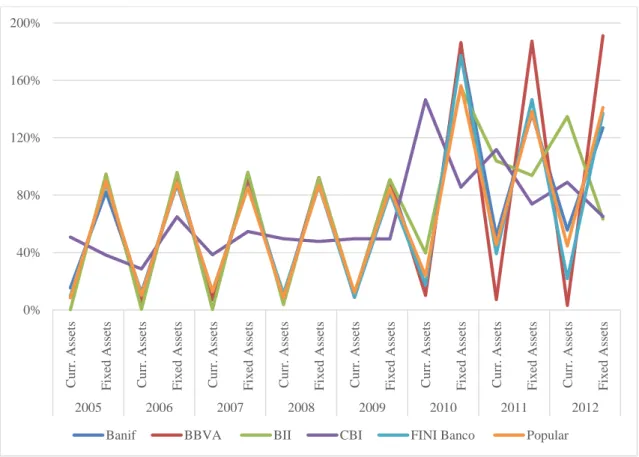

Taking figure number “8” into consideration, it is observable that there is an upward shift in current assets accounts starting from 2009 until 2012, following nearly steady movement from 2005 until 2008. On the other hand, fixed assets seem to follow a constant movement until 2009, where it showed some upward fluctuations in the last three years until 2012.

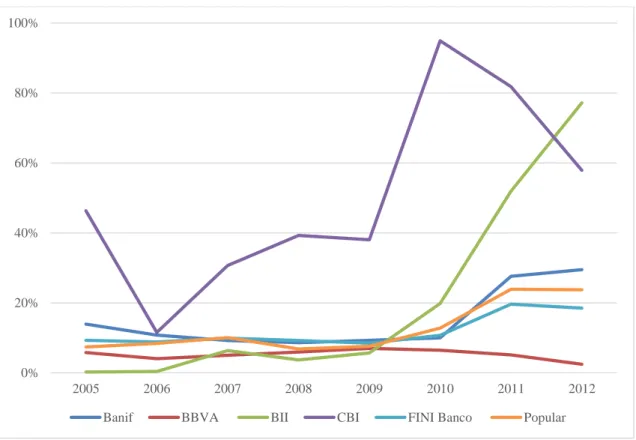

For liabilities and capital compositions, figure number “9” shows no significant changes within the structure of liabilities, nor in the equity participation over the study period.

A closer look into liabilities, figure number “14” shows that, in total, there is a growing trend in the level of “Deposits from other credit institutions” and “Deposits from central banks” starting from 2008 until 2012.

Current ratio analysis of the sample banks demonstrates a steady behavior until 2009, where a significant upward shift is noted in the last three years. This is shown in figure number “10” in “Appendix 1” section.

Except for FINI bank, total debt ratio analysis displays unchanging behavior over the entire study period, which is confirmed through figure number “11”.

Based on figures number “13” and “14”, HQLA annual level following the two approaches showed no volatility until 2001, where it started fluctuating in the last three years demonstrating an upward shift in the general level.

37

6.5. Research Findings

Concerning changes to the composition of the sample banks’ balance sheets, it is quite clear that there has been a steady proportional relationship between current and fixed accounts until 2009, where Basel III has been introduced driving banks into a transitioning phase until the new measures later in 2018-19 are fully implemented.

In the last three years until 2012, the growing tendency in assets’ current accounts is strictly attributable to the adaptation to the liquidity newly-born standards, the LCR in particular. LCR requires banks to invest more in liquid assets and to keep a minimum level of HQLA.

Looking at liabilities side, variations almost did not exist between current and longer liable commitments over the entire study period. However, figure number “14” verifies that there are two main changes within the composition of current liable accounts of the sample banks following the introduction of Basel III: (1) increased reliance on central banks borrowings; and (2) higher levels of credit institution deposits.

With reference to the NSFR standard, it is also noted that the sample banks are not yet oriented at enlarging terms of their liable commitments, but it has been proportionally compensated through expanding their holdings of short-term assets. Current ratio analysis (shown in figure number “10”) reflected the reduced structural mismatches between assets and liabilities. However, this not very ideal performance would impose higher pressure on the sample banks in the years to come to comply with the NSFR when it becomes a minimum requirement in January of 2018.

These findings are compatible with conclusions drawn by Giordana and Schumacher study that was presented in “Literature Review” section. Authors indicated that adaptation

38

to the new liquidity rules would require crucial balance sheet restructuring among other useful conclusions.

Considering the demand for liquid assets, the sample banks showed increased appetite on liquid assets following the introduction of Basel III in 2009. That was confirmed through the current ratio analysis, variations of assets in total, and more importantly variations of major liquid assets demonstrated in figure number “15”.

Figure number “15” verifies that the demand for three major liquid assets was tremendously increased since 2009: (1) Financial assets held for trading; (2) Financial assets available for sale; and (3) Held-to-maturity investments.

The annual stock of HQLA study - following the two approaches tested - shows positive prompt reaction toward the adaptation to Basel III liquidity framework. The sample banks started expanding their HQLA holdings since 2009.

However, annual stressed net cash outflows are necessary to be available to determine to what extent the sample banks could strengthen their standing in terms of the LCR standard during the transitioning period from 2009 to 2012. Therefore, findings do not provide fully clear and accurate conclusion in this regard.

Referring to the sample banks’ updates in their funding plans, and based on figure number “14” and “total debt” ratio analysis, it is noted that the adapted strategy is a mix of: (1) borrowings through debt securities; and (2) higher levels of deposits. However, deleveraging does not seem to be appealing to none of the sample banks. Total debt ratio analysis clearly shows that the capital participation level has never changed over the course of the study period.

39

Based also on figure number “14”, it is important to note that, the proportional increase in deposits outweighs the increase in debt securities borrowings. Therefore, the sample banks are found to be attracting larger volume of deposits (from central banks and other financial institutions in particular) to finance their assets since the introduction of Basel III in 2009-10.

The above mentioned findings are in harmony with the ECB study – presented in “Literature Review” section - that referred to an increase in the demand for central banks funds by banks in order to comply with the new liquidity rules.

7. Conclusion

Since the introduction of Basel III Accord in 2009-10, banks are undergoing a transitioning period in adaptation to the new liquidity regulatory requirements that are intended to take full effect later in 2018-19. Banks ever since have reconsidered their liquidity management frameworks in order to improve the fitting of their business models with the LCR and NSFR newly-born standards.

Through the conducted empirical study, it was noted that activities of small banks were directly impacted by the LCR and NSFR liquidity standards. The adaptation process have led to: (1) major changes in the composition of balance sheets; (2) increased volume of liquid assets holdings; (3) shifts in assets’ funding strategies; and (4) reduced structural maturity mismatches between assets and liabilities.

In my opinion, the regulatory primary goal of reducing the likelihood of witnessing other new severe financial crises in the future was well achieved. The addition of the LCR and NSFR standards to liquidity management turned out to be truly effective in improving banks’ risk profiles, and protecting the financial system of sudden liquidity scarcity.

40

But I think, up to 2012, the transitioning period was moderately enough to show initial repercussions of the new liquidity standards in the banking activities. Nevertheless, until the LCR and NSFR are fully implemented, the full range of their implications would remain restricted.

41

Bibliography

BIS. (2008). Principles for Sound Liquidity Risk Management and Supervision. Basel: Bank for International Settlements.

BIS. (2010). An Assessment of the Long-term Economic Impact of Stronger Capital and Liquidity

Requirements. Basel: Bank for International Settlements.

BIS. (2013). Basel III: The Liquidity Coverage Ratio & Liquidity Risk Monitoring. Basel: Bank for International Settlements.

BIS. (2013). Financial Crises and Bank Funding: Recent Experience in the Euro Area. Basel: Bank for International Settlements.

BIS. (2013). Liquidity Regulation and the Implementation of Monetary Policy. Basel: Bank for International Settlements.

BIS. (2014). Basel III: The Net Stable Funding Ratio. Basel: Bank for International Settlements. Bonner, C., & Eijffinger, S. (2013). Impact of the LCR on the Interbank Money Market. Frankfurt:

ECB.

Dietrich, A., Hess, K., & Wanzenried, G. (2014). The Good and Bad News About the New Liquidity Rules of Basel III in Western European Countries. Journal of Banking &

Finance.

Doran, D., Kirrane, C., & Masterson, M. (2014). Some Implications of New Regulatory Measures

for Euro Area Money Markets. Dublin: Central Bank of Ireland.

EBA. (2013). Definition of HQLA. London: EBA.

42

Giordana, G., & Schumacher, I. (2011). The Impact of the BASEL III Liqudiity Regulations on the Bank Lending Channel: a Luxembourg Case Study. Central Bank of Luxembourg, 19-24.

Haan, L., & End, J. W. (2013). Bank Liquidity, the Maturity Ladder and Regulation. Journal of

Banking & Finance.

Hartlage, A. W. (2013). The Basel III Liquidity Coverage Ratio and Financial Stability. Michigan

Law Review.

King, M. R. (2013). The Basel III Net Stable Funding Ratio and Bank Net Interest Margins.

Journal of Banking & Finance.

Quingnon, L. (2014). From Basel II to Basel III: Considerable Quantitative Impacts. BNP Paribas .

Ruozi, R., & Ferrari, P. (2013). Liquidity Risk Management in Banks: Economic and Regulatory

Issues. Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London.

Schmitz, S. W. (2013). The Impact of the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) on the Implementation of Monetary Policy. Economic Notes, 135–170.

Schuster, T., Kövener, F., & Matthes, J. (2013). New Bank Equity Capital Rules in the European

Union. Cologne: Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Köln.

Vahey, J., & Oppenheimer, L. (2014). A Liquid Bank is a Solid Bank. Third Way: Financial

Services .

Wiszniowski, E. (2010). Stress Testing As a Tool for Simulating the Effects of Crisis in Banks.

43

Appendix 1

Figure 1: LCR Standard Mechanism

44

Figure 3: LCR—HQLA Asset Classes and Haircuts Related to Them (BIS, 2013)

Figure 4: NSFR Standard Mechanism

45

Figure 6: Optimization Structure of the NSFR Standard (King, 2013)

46

Figure 8: Empirical Study—Assets Composition (Gross Values)

Figure 9: Empirical Study—Liabilities & Capital Composition (Gross Values) 0% 40% 80% 120% 160% 200% Cu rr . A ss e ts F ix ed As se ts Cu rr . As se ts F ix ed As se ts Cu rr . As se ts F ix ed As se ts Cu rr . As se ts F ix ed As se ts Cu rr . As se ts F ix ed As se ts Cu rr . As se ts F ix ed As se ts Cu rr . As se ts F ix ed As se ts Cu rr . As se ts F ix ed As se ts 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Banif BBVA BII CBI FINI Banco Popular

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% Cu rr . Li ab . Lo n g -term Li ab . Ca p it al Cu rr . Li ab . Lo n g -term Li ab . Ca p it al Cu rr . Li ab . Lo n g -term Li ab . Ca p it al Cu rr . Li ab . Lo n g -term Li ab . Ca p it al Cu rr . Li ab . Lo n g -term Li ab . Ca p it al Cu rr . Lia b . Lo n g -term Li ab . Ca p it al Cu rr . Li ab . Lo n g -term Li ab . Ca p it al Cu rr . Li ab . Lo n g -term Li ab . Ca p it al 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012