Toward Universal Learning

What Every Child Should Learn

1

Toward Universal Learning

Toward Universal Learning: What Every Child Should Learn is the first in a series of three reports from the Learning Metrics Task Force. Subsequent reports will address how learning should be measured within the global frame

-work of learning domains proposed herein, and how measurement of learning can be implemented to improve

education quality.

This report represents the collaborative work of the Learning Metrics Task Force’s members and their organiza

-tions, a technical working group convened by the task force’s Secretariat, and more than 500 individuals around the world who provided feedback on the recommendations. Members of the Standards Working Group who wrote the report are listed on page iii.

About the Learning Metrics Task Force

The UNESCO Institute for Statistics and the Center for Universal Education at Brookings have joined efforts to convene the Learning Metrics Task Force. The overarching objective of the project is to catalyze a shift in the global conversation on education from a focus on access to access plus learning. Based on recommendations from technical working groups and input from broad global consultations, the task force works to ensure learning becomes a central component of the global development agenda and make recommendations for common learn

-ing goals to improve learn-ing opportunities and outcomes for children and youth worldwide. Visit www.brook-ings. edu/learningmetrics to learn more.

This is a joint publication of the UNESCO Institute for Statistics and the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution.

The UNESCO Institute for Statistics

The UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) is the statistical office of UNESCO and is the UN depository for global statistics in the fields of education, science and technology, culture and communication. The UIS was established in 1999. It was created to improve UNESCO’s statistical program and to develop and deliver the timely, accurate and policy-relevant statistics needed in today’s increasingly complex and rapidly changing social, political and eco

-nomic environments. The UIS is based in Montreal, Canada.

The Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution

The Center for Universal Education (CUE) at the Brookings Institution is one of the leading policy centers focused on universal quality education in the developing world. CUE develops and disseminates effective solutions to achieve equitable learning, and plays a critical role in influencing the development of new international education policies and in transforming them into actionable strategies for governments, civil society and private enterprise.

The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined or influenced by any donation.

The Learning Metrics Task Force

Cochairs

Rukmini Banerji, Director of Programs Pratham Sir Michael Barber, Chief Education Advisor Pearson Geeta Rao Gupta, Deputy Director UNICEF

Member Organizations and Representatives*

ActionAid and GPE Board Representative for Northern Civil

Society David Archer, Head of Programme Development

African Union (AU) H.E. Jean Pierre O. Ezin, Commissioner Arab League of Educational, Cultural, and Scientific

Organization (ALECSO) Mohamed-El Aziz Ben Achour, Director General Association for Education Development in Africa (ADEA) Jean-Marie Ahlin Byll-Cataria, Executive Secretary Campaign for Female Education in Zambia (Camfed) and

GPE Board Representative for Southern Civil Society Barbara Chilangwa, Executive Director

City of Buenos Aires, Argentina Mercedes Miguel, General Director of Education Planning Dubai Cares / United Arab Emirates (UAE) H.E. Reem Al-Hashimy, Chair and Minister of State Education International (EI) Fred van Leeuwen, General Secretary

Agence Française de Développement (AFD) Jean-Claude Balmes, Senior Advisor Global Partnership for Education (GPE) Carol Bellamy, Chair of the Board Government of Assam, India Dhir Jhingran, Principal Secretary International Education Funders Group (IEFG) Chloe O’Gara, Co-chair

Kenyan Ministry of Education George Godia, Permanent Secretary Korean Educational Development Institute (KEDI) Tae-Wan Kim, President

Office of the UN Secretary General Itai Madamombe, Global Education Advisor Organización de Estados Iberoamericanos (OEI) Álvaro Marchesi, Secretary-General

Queen Rania Teacher Academy Tayseer Al Noiami, President and former Minister of Education of Jordan South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) Saleem Ahmed, Secretary-General

Southeast Asian Minister of Education Organization

(SEAMEO) Witaya Jeradechakul, Director

U.K. Department for International Development (DFID) Jo Bourne, Head of Education

United Nations Development Program (UNDP) Selim Jahan, Director of Poverty Practice

UNESCO Olav Seim, Director, EFA Global Partnerships Team

United States Agency for International Development (USAID) John Comings, Education Advisor

World Bank Beth King, Director of Education

*as of September 2012

Secretariat

UNESCO Institute for Statistics

Hendrik van der Pol Director

Albert Motivans Head of Education Indicators and Data Analysis Section

Maya Prince Research Assistant

Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution

Rebecca Winthrop Senior Fellow and Director

Xanthe Ackerman Associate Director

Early Childhood Subgroup Members

Rokhaya Diawara UNESCO Regional Bureau for Education in Africa (BREDA), Senegal Mariana Hi Fong Universidad Casa Grande/Blossom Centro Familiar, Guayaquil, Ecuador Mihaela Ionescu International Step by Step Association, Hungary

Magdalena Janus Offord Centre for Child Studies, McMaster University, Canada Joan Lombardi Bernard van Leer Foundation, USA

Nino Meladze-Zullo Early Childhood Education Consultant, USA Mary A. Moran ChildFund International, USA

Emily Morris Education Development Center, USA Linda M. Platas Heising-Simons Foundation, USA Abbie Raikes UNESCO, France

Amima Sayeed Pakistan Coalition for Education, Pakistan Pablo A. Stansbery Save the Children, USA

Primary Subgroup Members

Taghreed Barakat International Rescue Committee, Iraq David Chard Southern Methodist University, USA Jeff Davis School-to-School International, USA Latif Armel Dramani Université de Thiès, Senegal Julia R. Frazier International Rescue Committee, USA

Charles Oduor Kado Kenya Primary Schools Headteachers Association, Kenya Kathleen Letshabo UNICEF, USA

Heikki Lyytinen University of Jyväskylä, Finland Li-Ann Kuan American Institutes for Research, USA Sylvia Linan-Thompson University of Texas at Austin, USA Everlyn Kemunto Oiruria Aga Khan Foundation, Kenya

Postprimary Subgroup Members

Marina L. Anselme The Refugee Education Trust, Switzerland

Shila Bajracharya National Resource Center for Non-Formal Education and Center for Education for All, Nepal William G. Brozo George Mason University, USA

Peter J. Foley International Rescue Committee, Pakistan Pauline Greaves Commonwealth Secretariat, UK

Maha A. Halim FHI 360, Egypt

Ross Hall Pearson, UK

Maria Langworthy Innovative Teaching and Learning Research, USA Cynthia Lloyd Population Council, USA

Moses Waithanji Ngware African Population and Health Research Center, Kenya Mariam Orkodashvili Georgian-American University, Tbilisi, Georgia Benjamin A. Ogwo State University of New York—Oswego, USA Anjlee Prakash Learning Links Foundation, India

Ralf St. Clair McGill University, Canada

Standards Working Group Members

Standards Working Group Chair: Seamus Hegarty, International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA)

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations and Acronyms

ASER Annual Status of Education Report

CONFEMEN Conférence des ministres de l’Éducation des pays ayant le français en partage CRC UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

CUE Center for Universal Education

EDI Early Development Instrument

EFA Education for All

EGMA Early Grade Math Assessment

EGRA Early Grade Reading Assessment

GER Gross Enrollment Ratio

GPE Global Partnership for Education

HECDI Holistic Early Childhood Development Index

IEA International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement

INEE Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies

ISCED International Standard Classification of Education IUHPE International Union of Health Promotion and Education LAMP Literacy Assessment and Monitoring Programme

LLECE Laboratorio Latinoamericano de Evaluación de la Calidad de la Educación

LMTF Learning Metrics Task Force

MDG Millennium Development Goals

MICS Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey

OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development PASEC Programme d’Analyse des Systèmes Éducatifs de la CONFEMEN PIAAC Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies PIRLS Progress in International Reading Literacy Study

PISA Programme for International Student Assessment

SACMEQ Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality

TIMSS Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study

UIS UNESCO Institute for Statistics

Contents

Introduction . . . 1

What Learning Is Important for All Children and Youth? . . . 2

When Are Children Learning? . . . .3

A Global Framework of Learning Domains . . . 4

Considerations Related to the Seven Domains . . . .5

Children with Disabilities . . . .5

Gender . . . .5

Conflict and Emergencies . . . .6

Countries Demonstrating Low Levels of Learning . . . .6

Sources of Evidence . . . .6

Description of the Seven Domains . . . 8

Physical Well-Being . . . 11

Physical Well-Being: Early Childhood Level . . . 11

Physical Well-Being: Primary Level. . . 12

Physical Well-Being: Postprimary Level . . . .13

Social and Emotional . . . .15

Social and Emotional: Early Childhood Level . . . .16

Social and Emotional: Primary Level . . . 18

Social and Emotional: Postprimary Level . . . 19

Culture and the Arts . . . 21

Culture and the Arts: Early Childhood Level . . . 22

Culture and the Arts: Primary Level . . . 24

Culture and the Arts: Postprimary Level . . . .26

Literacy and Communication . . . 27

Literacy and Communication: Early Childhood Level . . . 28

Literacy and Communication: Primary Level . . . 29

Literacy and Communication: Postprimary Level . . . .32

Learning Approaches and Cognition . . . .33

Learning Approaches and Cognition: Early Childhood Level . . . .34

Learning Approaches and Cognition: Primary Level . . . .36

Numeracy and Mathematics . . . .40

Numeracy and Mathematics: Early Childhood Level . . . .40

Numeracy and Mathematics: Primary Level . . . 42

Numeracy and Mathematics: Postprimary Level . . . .43

Science and Technology . . . .45

Science and Technology: Early Childhood Level . . . .46

Science and Technology: Primary Level . . . 47

Science and Technology: Postprimary Level . . . 48

Overarching Considerations . . . .50

Conclusion . . . .52

References . . . .53

Annex A: Individuals Contributing to the Phase I Public Consultation Period . . . .64

Annex B: Selected Global Dialogues and Frameworks on Learning Outcomes . . . .75

Education for All . . . .75

UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) . . . .75

The DeLors Report . . . .76

Rio +20: The Future We Want . . . .76

GPE Indicators . . . 77

Education First . . . 77

Annex C: International, Regional and Cross-National Initiatives to Measure Learning . . . 78

Annex D: Methodology . . . 81

Establishment of the Learning Metrics Task Force . . . 81

First Working Group on Learning Standards . . . .83

First Public Consultation Period . . . 84

First In-Person Task Force Meeting . . . .86

Annex E: First Public Consultation Document . . . 94

Background . . . 94

Proposed Competencies for Early Childhood . . . .96

Proposed Competencies for the Primary Level . . . 98

Proposed Competencies for the Postprimary Level . . . .100

The benefits of education—for national development, individual prosperity, health and social stability—are well known, but for these benefits to accrue children in school have to be learning. Despite commitments and progress in improving access to education at the global level, including Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 2 on universal primary education and the Education for All (EFA) Goals, levels of learning are still too low. According to estimations in the 2012 EFA Global Monitoring Report, at least 250 million primary-school-age children around the world are not able to read, write or count well enough to meet minimum learning standards, including those who have spent at least four years in school (UNESCO 2012). Worse still, we may not know the full scale of the crisis and this figure is likely to be an underestimate because measurement of learning outcomes among children and youth is limited and, relative to the measurement of access, more dif

-ficult to assess at the global level.

To advance progress for children and youth around the world, it is critical that learning is recognized as essential for human development. As EFA and the MDGs sunset in 2015, and the UN Secretary-General promotes the Global Education First initiative, the edu

-cation sector has a unique window of opportunity to raise the profile of international education goals and ensure that learning becomes a central component of the global development agenda. To do this, the global education community must work collectively to define global ambition on improving learning and propose practical actions to deliver and measure progress.

In response to this need, UNESCO, through its

Universal Education (CUE) at the Brookings Institution have co-convened the Learning Metrics Task Force (LMTF). The overarching objective of the project is to catalyze a shift in the global conversation on education from a focus on access to access plus learning. Based on recommendations of technical working groups and input from broad global consultations, the task force aims to make recommendations to help countries and international organizations measure and improve learning outcomes for children and youth worldwide. Rather than focusing just on developing countries, the task force decided that its recommendations should be truly global and address all countries. It was also agreed that equity within countries should be empha

-sized in addition to overall national learning levels.

The task force—which is made up of representatives of national and regional governments, EFA-convening agencies, regional political bodies, civil society, and donor agencies1—is engaged in an 18-month-long global consultation process to build a consensus around the answers to three questions:

• What learning is important for all children and youth?

• How should learning outcomes be measured?

• How can measurement of learning improve educa

-tion quality?

In Phase I of the project, the LMTF’s Standards Working Group convened from May to October 2012 to make recommendations on what learning is impor

from more than 500 individuals in 57 countries. A draft framework was presented to the task force at an in-person meeting in September 2012. Over two days, the LMTF finalized a framework to be used by the subsequent working group on measures and methods to investigate the measurement of learning outcomes.

The Standards Working Group was tasked with devel

-oping a framework for learning outcomes that would not be restricted to those outcomes that lend them

-selves easily to measurement and are, as a result, currently prioritized. As one consultation respondent stated, “The seductive charm of numbers may well mean we evaluate whatever aspects of learning we are able to measure best and sideline those elements that are more intuitive and difficult to express numerically.” The subsequent working group on measures and methods will examine how the competencies may be measured, looking beyond the most commonly mea

-sured domains of literacy and numeracy.

This report presents the results of a collaborative pro

-cess to identify what domains of learning are important for children and youth to master in order to succeed in school and life. As such, the report’s primary purpose is to document the process and describe the rationale for the proposed framework. Subsequent reports, to be released in 2013, will provide actionable recom

-mendations for stakeholders in the global education community.

What Learning Is Important for All

Children and Youth?

The first phase of the Learning Metrics Task Force project addressed the overarching question of what learning is important globally. The Standards Working Group was charged with investigating whether cer

-tain standards, competencies, knowledge or areas of

ing should be measured only in schools or whether all children should be assessed, regardless of whether

they are or ever have been in school. To address this

issue, it is important to examine the various contexts in which children are learning around the world.

Globally, 164 million children are enrolled in preschool programs, and the preprimary gross enrollment ratio (GER) is 48 percent (UNESCO 2012). However, ac

-cess to preprimary programs is unevenly distributed, with a GER of only 15 percent in low-income countries. The children least likely to be enrolled in preschool are those belonging to minority ethnic groups, those with less educated mothers, and those who speak a home language different from the language used in school (UNESCO 2012). These are also the children most likely to benefit from high-quality preprimary programs. While many children, especially in high-income coun

-tries, attend formal, regulated preprimary programs, the majority of the world’s young children only learn in nonformal contexts through unstructured or informal processes. For these children, learning typically oc

-curs in the home and community through interactions with parents, siblings and other family members. Even when children are enrolled in preprimary programs, they may not be exposed to quality formal early learn

-ing opportunities.

Partially due to a global focus on universal primary education, the majority (89 percent) of primary age children are now enrolled in school (UNESCO 2012). Free, compulsory primary education is recognized as a fundamental human right (United Nations 1948), and primary education is compulsory in almost ev

-ery country, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS 2012). Still, there are nearly 61 million out-of-school children of primary-school age, a num

However, the degree to which formal processes are good enough to ensure children’s right to a decent education depends in large part on the quality of the teachers, curriculum and materials found in the school. In schools where there are enough qualified teach

-ers and materials to respond to each individual child’s learning needs, academic learning occurs through formal processes. In schools where teachers are not properly qualified, are overextended or do not come to work regularly, learning still occurs through peer-to-peer interactions—but not necessarily the types of learning intended by the school system.

The category of postprimary refers to the various con

-texts in which children learn beyond primary schooling. For most children, “postprimary” refers to secondary education. The task force decided that the recommen

-dations of the LMTF should focus on lower secondary for this level, given the diverse areas of specialization students experience after this schooling level. The UIS reports that in 2010, lower secondary education was part of compulsory education in three out of four coun

-tries reporting data, and upper secondary was included in compulsory education in approximately one in four countries (UIS 2012). It is estimated that globally, 91 percent of children who entered school stay there un

-til the end of primary school, and 95 percent of those

students transition to secondary school. However, for children in low-income countries, only 59 percent make it to the last year of primary school and 72 percent of those students successfully transition to secondary school (UIS 2012). For children who do not attend sec

-ondary school, learning occurs mainly through work, family and community experiences (i.e., nonformal, unstructured contexts).

When Are Children Learning?

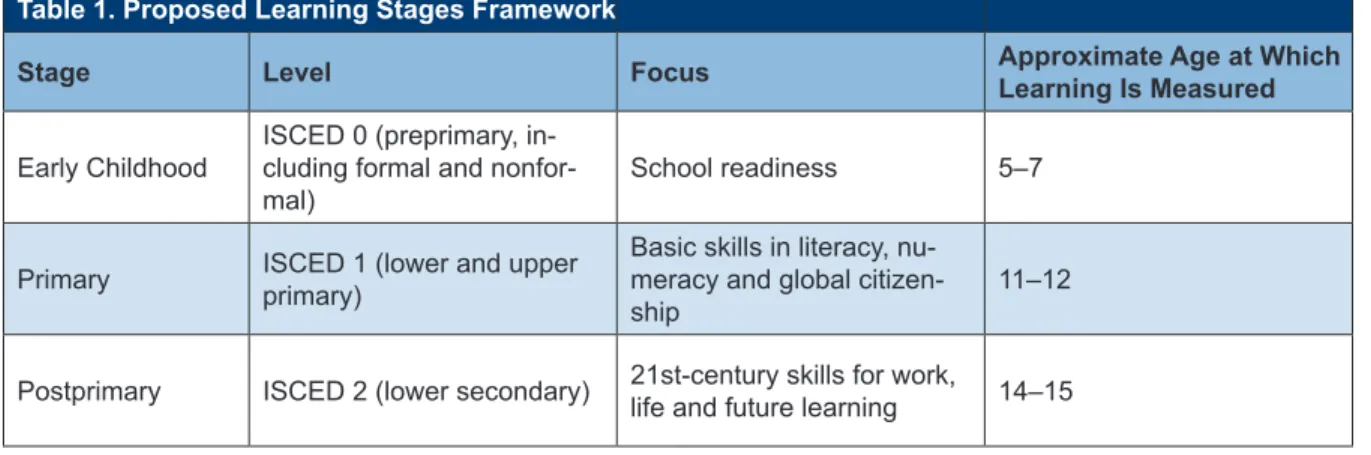

The times when children learn can be described through stages (early childhood, primary and postpri

-mary), schooling levels, and/or age groups. How these groupings correspond to one another varies across countries and even across individual children. The fol

-lowing table attempts to define the stages, schooling levels and approximate age spans for these groups. The schooling levels are based on the 1997 revision of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) (UNESCO 1997). Note that the age spans overlap intentionally to account for wide variations in when children begin and end school. The ages in the final column, “approximate milestone at which learn

-ing might be measured at a global level,” correspond to key points of primary school entry, end of primary cycle, and end of lower-secondary cycle.

Table 1. Stages, Schooling Levels and Approximate Age Spans for Measuring

Learning Outcomes

Stage Schooling Level Approximate Age Spans for Stage and Schooling Level

Approximate Milestone at Which Learning Might Be Measured at a Global Level

Early childhood

Birth through school entry, including ISCED 0 (preprimary, including formal and nonformal)

0–8 School entry

Primary ISCED 1 (lower and upper primary) 5–15 End of primary cycle

Given the various structures, places and times at which humans learn, it is difficult to define what outcomes re

-lated to learning are important, especially at a global level. However, based on (1) research, (2) global poli

-cies and dialogues and (3) the real-life experience of those working in education, the working group and task force identified certain outcomes as important for all children and youth to develop. Based on the recom

-mendations of the 39 working group members, input from global consultations and task force deliberation, seven domains and corresponding subdomains of out

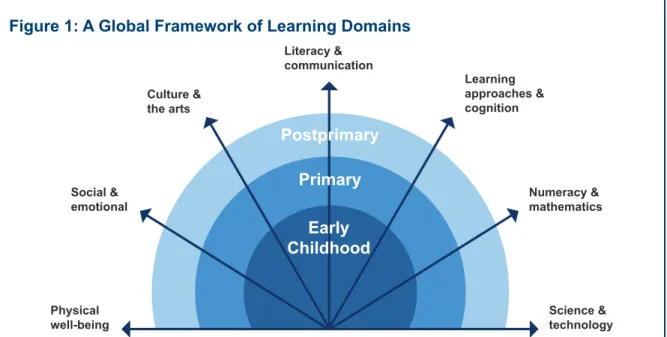

-comes related to learning are proposed as important for all children and youth (see Figure 1 and annex D for a detailed description of the methodology used in determining these domains):

• Physical well-being • Social and emotional

• Culture and the arts

• Literacy and communication • Learning approaches and cognition • Numeracy and mathematics • Science and technology

Each arrow in Figure 1 represents one domain of learning, radiating outward as a child expands his or her development or competency in a given area. The half circles represent three stages in which the task force will concentrate its recommendations: early childhood (birth through primary school entry); primary and postprimary (end of primary through end of lower secondary). The arrows extend outward beyond the diagram to indicate that an individual may continue learning more deeply in a given area at the upper sec

-ondary, tertiary, or technical/vocational level or through nonformal learning opportunities.

Figure 1: A Global Framework of Learning Domains

Early

Childhood

Primary

Postprimary

Physical Science &

Numeracy & mathematics Social &

emotional

Culture & the arts

Literacy & communication

Learning approaches & cognition

Global Framework of Learning Domains

The task force noted several considerations for vari

-ous populations and contexts related to the seven domains. The following subsections describe these aspects.

Children with Disabilities

An estimated 15-20 percent of students worldwide have special learning needs, and children with disabili

-ties are less likely to enroll in and complete school than their nondisabled peers (World Health Organization and World Bank 2011). In low-income countries, their exclusion from education can be very significant and result in lifelong discrimination.

The LMTF framework covers a broad set of learning outcomes so that children who struggle with traditional academic or cognitive tasks have an opportunity to demonstrate strengths in a variety of domains. With targeted instructional support and accommodations, children with disabilities can make progress toward learning goals in all seven domains. When assessing learning for children with disabilities, as with all chil

-dren, a focus on individual progress can be more rel

-evant in measuring and improving learning outcomes than a focus on absolute learning levels. More frequent and fine-grained monitoring of progress may be neces

-sary to capture improvements in learning for children with disabilities.

Gender

Gender may be more important in discussing the de

-terminants of learning in the classroom than in making choices about outcome measures. Gender issues may be important across all domains, but especially in the physical well-being, social and emotional, and learning approaches and cognition domains. For example, in physical well-being the fact that girls can get pregnant and boys cannot, compounded with a social and cul

-tural context of male power and female subservience, make necessary learning outcomes in this area quite different for boys and girls.

There is an implicit assumption in the LMTF frame

-work that as the arrows radiate out, from level to level, children are developing and learning at a similar and steady rate. However, in many settings this is not al

-ways the case given delayed school entry ages as well as repetition rates. Thus particularly when looking at the physical well-being domain and the social and emotional domain, one needs to recognize that physi

-cal and emotional development may also be affected by age as well as by level. This is compounded by the fact that girls tend to reach puberty about two years before boys do. While one can reasonably assume that all postprimary students are older adolescents or young adults, one cannot assume that all primary stu

-dents are preadolescent.

Conflict and Emergencies

War and natural disasters can significantly disrupt a child’s education and learning trajectory. When chil

-dren are displaced due to these circumstances, they often are excluded from school for years, sometimes even generations. However, a high-quality education in emergency situations can provide physical, psycho

-social and cognitive protection that can sustain and save lives (INEE 2010). In the domains of physical well-being and social and emotional, education can provide children with critical survival skills and coping mechanisms through learning about landmine safety, HIV/AIDS prevention and conflict resolution strategies. Learning may occur in formal schooling settings, but very often it occurs in informal ways during conflict and emergencies. Therefore, efforts to assess children’s learning must take into account where school-age children are, what is being taught, mother tongue and language of instruction, and a variety of other factors (INEE 2010).

Countries Demonstrating Low Levels of

Learning

The current international capacity for measuring learn

-ing is concentrated most strongly in the domains of literacy and communication, numeracy and mathemat

-ics, and science and technology. While these studies do not provide a complete picture of what children and youth have learned, they are the basis for analysis of learning levels globally. Beatty and Pritchett (2012) argue that any leaning goals proposed as part of the post-2015 development agenda should be “based on feasibility, not wishful thinking.” Goals are only suc

-cessful in accelerating progress if they are perceived as achievable. In many developing countries, learning progress in the areas of literacy, mathematics, and sci

-ence is stagnant or even declining based on results

thors estimate that given current trends, it would take Colombia 30 years and Turkey 194 years to reach mean Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) levels of learning as measured by Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), and that countries such as Indonesia, Iran, Jordan, Malaysia, Thailand and Tunisia will never catch up as learning levels have actually declined from one testing period to the next. Among countries participating in the SACMEQ (Anglophone countries in Southern and Eastern Africa), it could take four to five generations (150 years, on average) to catch up to mean OECD learning levels in reading, given cur -rent trends.

In another report, Pritchett and Beatty (2012) find that having an overambitious curriculum in countries where achievement levels are low can lead to a “curriculum gap,” whereby more children are excluded from learn

-ing and never catch up. These countries end up be-ing farther behind than ones in which the curriculum is appropriate for children’s learning levels. Given these complexities, it appears that setting one-size-fits-all standards is unlikely to be useful at a global level. The LMTF must determine whether a framework can be developed that allows countries to set achievable goals based on current learning levels, understanding that a tiered system could send a message that high standards are achievable by some children and youth

but not others.

Sources of Evidence

The LMTF considered the following three main sources of evidence to develop its recommendations:

• Policies, including global goals, dialogue and frame

• Research linking the domains to well-being, aca

-demic achievement, life skills, etc.; and

• Feedback from global consultations.

Policies and Global Dialogues

The major global frameworks and dialogues referenc

-ing goals of education and/or learn-ing outcomes are the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), the DeLors Report (1996), Education for All (EFA) goals and the Dakar Framework for Action (2000), and Education First—An Initiative of the UN Secretary General (2012). The Global Partnership for Education (GPE) has engaged in a consultative process to develop indicators for GPE countries, among them basic literacy and numeracy. There is also a brief men

-tion of learning outcomes in the Rio +20 Outcomes Document, “The Future We Want” (2012). A summary of the global frameworks is below, and a more detailed description is given in annex B.

• UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (1989)

• Article 24 encourages education of children and parents on “basic knowledge of child health and nutrition, the advantages of breastfeeding, hy

-giene and environmental sanitation and the pre

-vention of accidents.”

• Article 28 calls for international cooperation in education with regard to “the elimination of ig

-norance and illiteracy throughout the world and facilitating access to scientific and technical knowledge . . .”

• Article 29 refers to the direction of a child’s edu

-cation and includes elements related to personal

-ity, talents, mental and physical abilities; respect for human rights; respect for own and others’ cultures; tolerance; and respect for the natural environment.

• The DeLors Report (1996): Identifies four types of knowledge: learning to know, learning to do, learning to live together and learning to be.

• EFA Goal 1 (2000): Comprehensive early childhood education that “should focus on all of a child’s needs including health, nutrition and hygiene, cognitive, and social development.”

• EFA Goal 6 (2000): Quality education “so that mea

-sureable learning outcomes are achieved by all, especially in literacy, numeracy and essential life skills.”

• Rio +20, The Future We Want (2012): Calls for in

-creased capacity of education to prepare for sus

-tainable development and “more effective use of information and communications technologies to enhance learning outcomes.”

• GPE Indicators (2012): Basic literacy and numeracy in the early grades have been proposed as indica

-tors for Strategic Goal 2, Learning for All.

• Education First (2012): Improving the quality of learning is one of the three focus areas, with specific targets identified.

The existing frameworks for measuring learning at the multicountry level (cross-national, regional and inter

-national) are also indicative of consensus on learning outcomes. (For a description of these frameworks, see annex C and the LMTF background paper, “Multi-Country Assessments of Learning.”2)

Research

has been conducted primarily in North America and Western Europe, the research findings are presented along with results from the global consultation, in which 3 out of 4 participants were in the Global South, primar

-ily in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

Global Consultation Results

The document “Draft Competencies for Learning Outcomes: Early Childhood, Primary, and Post-Primary” (see annex E) was circulated for public com

-ment on August 2, 2012. More than 500 people in at least 57 countries provided feedback by participating in in-person consultations and/or sending feedback via e-mail.

Several overarching themes emerged from the con

-sultations:

• Respondents were pleased that learning was de

-fined more broadly than literacy and numeracy. However, there was disagreement on how compre

-hensive the LMTF’s recommendations can be at the global level. The competencies were at the same time considered not comprehensive enough for ap

-plicability at the country level, and too comprehen

-sive to be applicable at the global level. In particular, teachers and other practitioners advocated a more comprehensive framework while academics and others working at the global level favored a more succinct set of domains.

• There was a request for alignment of terminology and domains across the age groups. In particular, science, critical thinking and physical well-being were perceived to be absent from the primary and

postprimary levels. Based on this input, the working groups decided upon the seven domains described above, with the understanding that the capacity and demand for measuring them may vary greatly across age groups.

• A set of “illustrative indicators” were proposed as examples of how learning may be demonstrated within a domain. These indicators were considered too specific and in some cases confusing, and there was a lack of consensus about which illustrative in

-dicators could be applied across language groups and contexts. Therefore, the Secretariat is collecting these comments and will be providing them to the Measures and Methods Working Group, but it has not put them forth in this document. We focus on domains and potential subdomains in this working paper.

• There was much discussion about where the stan

-dards should be set. Some felt the competencies were too ambitious for the majority of countries and worried about setting standards where there were not sufficient material and human resources avail

-able to meet them. Others felt that the competencies were at the right level.

Description of the Seven Domains

The seven domains for learning identified by the LMTF are all applicable from early childhood through postprimary schooling, although some domains are more relevant at different learning stages. This section provides a brief description of the domains and subdo

-mains identified by the task force and working groups and then goes into detail on the domains and subdo

Table 2: Domains and Subdomains of the Global Learning Domains Framework

Domain Subdomains

Early Childhood Level Primary Level Postprimary Level

Physical well-being

• Physical health and nutri -tion

• Health knowledge and practice

• Safety knowledge and practice

• Gross, fine, and percep

-tual motor

• Physical health and hy

-giene

• Food and nutrition

• Physical activity • Sexual health

• Health and hygiene • Sexual and reproductive

health

• Illness and disease pre -vention

Social and emotional

• Self-regulation • Emotional awareness • Self-concept and

self-efficacy • Empathy

• Social relationships and

behaviors

• Conflict resolution • Moral values

• Social and community

values

• Civic values

• Mental health and well-being

• Social awareness • Leadership • Civic engagement • Positive view of self and

others

• Resilience/“grit” • Moral and ethical values

• Social sciences

Culture and the arts

• Creative arts

• Self- and

community-identity

• Awareness of and respect for diversity

• Creative arts

• Cultural knowledge • • Creative artsCultural studies

Literacy and communication

• Receptive language • Expressive language • Vocabulary

• Print awareness

• Oral fluency • Oral comprehension • Reading fluency • Reading comprehension • Receptive vocabulary • Expressive vocabulary • Written expression/ com

-position

• Speaking and listening • Writing

• Reading

Learning approaches and cognition

• Curiosity and engagement • Persistence and attention • Autonomy and initiative • Cooperation

• Creativity

• Reasoning and problem solving

• Early critical thinking skills • Symbolic representation

• Persistence and attention • Cooperation

• Autonomy • Knowledge • Comprehension • Application • Critical thinking

• Collaboration

• Self-direction • Learning orientation • Persistence • Problem Solving • Critical decisionmaking • Flexibility

The following sections describe the research, policy and consultation evidence for using these seven domains to develop a global learning outcomes framework.

Domain Subdomains

Early Childhood Level Primary Level Postprimary Level

Numeracy and mathematics

• Number sense and opera -tions

• Spatial sense and geom -etry

• Patterns and classification • Measurement and com

-parison

• Number concepts and operations

• Geometry and patterns • Mathematics application

• Number • Algebra • Geometry

• Everyday calculations

• Personal finance • Informed consumer • Data and statistics

Science and technology

• Inquiry skills

• Awareness of the natural and physical world • Technology awareness

• Scientific inquiry • Life science • Physical science • Earth science

• Awareness and use of digital technology

• Biology • Chemistry • Physics • Earth science

Description: Physical well-being describes how children and youth use their bodies, develop motor control, and understand and exhibit appropriate nutri

-tion, exercise, hygiene and safety practices. For older children and adolescents, the domain of physical well-being refers to the knowledge that individuals need to learn to ensure their own health and well-being, as well as that of their families and communities.

Policy Rationale: The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) Article 24.1.e affirms that states should take measures “to ensure that all segments of society, in particular parents and children, are informed, have access to education and are supported in the use of basic knowledge of child health and nutrition, the ad

-vantages of breastfeeding, hygiene and environmental sanitation and the prevention of accidents.” Currently, health and physical well-being indicators (under-five mortality rate and stunting) are used to monitor prog

-ress toward EFA Goal 1 (UNESCO 2011). Current ef

-forts to assess physical well-being in early childhood at the global level are conducted through UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS4) Early Child Development Index (ECDI) and the Early Development Instrument (EDI).

EFA Goal 6 lists life skills as an area for measurable learning outcomes. UNICEF and UIS include health knowledge and skills in their respective definitions of life skills. There are also many country-level poli

-cies that promote outcomes in this domain, such as England’s Every Child Matters agenda, which identi

-fies five outcomes for children in the health domain: physically healthy; mentally and emotionally healthy;

sexually healthy; healthy lifestyles; and choosing not to take illegal drugs.

Recent policy initiatives have recognized the need for individuals to take increasing responsibility for the management of their own well-being—there is recogni

-tion that health services must complement the choices and actions of individuals. It is important to note that, while health outcomes are directly and strongly related to income and income distribution (Deaton 2002), many aspects of health and well-being are still in the control of individuals. The ability of individuals to make informed choices can be a significant contribu

-tion to raising the general well-being of the popula-tion while reducing the fiscal cost of health care systems. Current measurement efforts tend to emphasize health behaviors rather than ensure that people have the information they need to make choices conducive to well-being. It is necessary to understand the knowl

-edge that people possess before it is possible to make sense of their choices and the consequences.

Physical Well-Being: Early Childhood

Level

Research Rationale: An estimated 200 million chil

-dren younger than age five are not fulfilling their devel

under five globally suffer from moderate to severe stunting, with the majority residing in low-income coun

-tries and in the Sub-Saharan Africa and South and West Asia regions. Grissmer and colleagues (2010) found that motor skills in early childhood were signifi

-cant predictors of achievement in reading and math

-ematics in primary school.

Consultation Rationale: The consultation results

showed strong support for including physical health and well-being. Several consultation respondents felt that the outcomes related to this domain were con

-sidered developmental outcomes and not learning

outcomes, but that they still were important indicators of well-being and predictors of later learning ability. Contributors requested a variety of domains to be added that are linked to cognitive development but are actually inputs and not learning or developmental outcomes. Some of these indicators—such as child protection policies, clean water and sanitation—are in

-cluded in other efforts designed to address early child

-hood development, including UNESCO’s Holistic Early Childhood Development Index (HECDI). The LMTF will continue to explore partnerships to help address criti

-cal questions around inputs and context.

Subdomains of the Physical Well-Being Domain for Early Childhood

Subdomains Description

Physical health and nutrition

Physical health and nutritional status can be considered more a developmental domain than a learning domain. It refers to children being free from disease and adequately nourished, and may refer to understanding the dangers and benefits of specific foods.

Health knowledge and practice

Health knowledge and practice refers to habits related to health and hygiene as appropriate to the child’s context, including elimination (toileting), eating, hand washing and brushing teeth.

Safety knowledge and practice

For young children, safety refers to their ability to recognize and avoid threats in the environment. This varies widely by context, but includes recognizing threats related to conflict, roads, water, animals, strangers, etc.

Gross, fine and

perceptual motor skills

Gross motor skills are large movements of the body used in activities such as run

-ning, jumping, crawling and climbing. Fine motor skills are small movements used in activities, such as picking up and manipulating objects, drawing, writing and us

-ing a keyboard. Perceptual motor skills are related to how the brain, eyes and body work together (e.g., hand-eye coordination).

Physical Well-Being: Primary Level

Research Rationale: Healthy behaviors such as hand washing and other measures to prevent disease have

-Subdomains for the Physical Well-Being Domain of the Primary Level

Subdomains Description

Physical health and hygiene

Understanding how disease is acquired is important at this level. Children learn how to prevent infectious diseases through hygiene, water and sanitation practices and noninfectious diseases through health and behavioral choices.

Food and nutrition

Outcomes for food and nutrition can vary widely by context. This domain involves recognizing how food has an impact on mind and body functions. In some contexts the focus is on making sure children get enough nutrients, while in others the focus is on eating the right amount of food to maintain a healthy weight.

Physical activity Physical activity includes exercise and developing individual talents through sports and games.

Sexual health Sexual health at the primary level varies by context, but includes understanding basic concepts of human reproduction. cessful outcomes on student behaviors: mental and

emotional health; substance use and misuse; hygiene, sexual health and relationships; healthy eating and nu

-trition; and physical activity (St. Leger et al. 2010). The authors reported that while current research examines topic-specific health interventions, a holistic approach to health that integrates multiple topics could be more effective in achieving measurable health and behav

-ioral outcomes.

Consultation Rationale: Physical well-being was not included in the draft competencies for the primary level, and many consultees requested that it be added, as healthy habits that are established early in life can endure throughout the lifetime. One consultee stated, “Physical well-being and motor development is also important, given the growing level of obesity. A term such as ‘exercise as foundation for healthy living’ might indicate the need to lay the foundations creatively for lifelong exercise habits.”

Physical Well-Being: Postprimary Level

Research Rationale: Recent years have seen the emergence of a new concept that captures the impor

-tance of information related to physical well-being— health literacy (Nutbeam 1999). While the concept originally referred to literacy skills having implications for health, the term has broadened to be used as a metaphor for the knowledge and behaviors that un

-derpin self-management of health. This knowledge in

-cludes nutrition, hygiene, disease prevention and child

care, but also goes further to include mental health (Jorm 2000).

Research indicates that adolescence is a key time for people to form health behaviors and make decisions with a potential long term impact upon their health. One study argues that this is particularly difficult for youth in developing countries: “The role of the ado

-Subdomains of the Physical Well-Being Domain for the Postprimary Level

Subdomains Description

Health and hygiene Health and hygiene includes knowing and applying healthy behaviors and hygiene practices, including those that are related to positive mental health outcomes.

Sexual and

reproductive health

Sexual and reproductive health refers to understanding basic concepts of sexual health, family planning, pregnancy and childbirth.

Illness and disease prevention

Illness and disease prevention involves knowing how health conditions are ac

-quired or transmitted and implementing strategies for prevention, including nutri

-tion and exercise choices. gent and comprehensive review is necessary by all sections of society if the health of this group is to im

-prove” (Balmer et al. 1997). A further factor emphasiz

-ing the importance of consider-ing health and physical well-being as a learning outcome is the flow of health care workers from poorer to rich countries, creating a difference in available expertise that can have a nega

-tive effect on health outcomes in the less-advantaged nations (Packer, Labonté, and Spitzer 2007).

Consultation Rationale: There were a considerable number of comments in the consultation calling for an expanded role for health information and behaviors within the competencies. As one consultee pointed out, the postprimary period is “a time when adolescent relationships and life skills can have huge health impli

-cations.” Another response underlining the importance of this domain indicated that the respondents “did feel that some were missing, in particular health, nutrition and safety awareness, personal hygiene, diet, fit

-ness, HIV/AIDS aware-ness, responsibility of self care etc., especially in postprimary.” There were also very consistent calls for “a much stronger emphasis on im

-portant outcomes in the fields of health and nutrition.” Several responses specifically called for the inclusion of reproductive health. While there is a need to main

-tain a clear distinction around the aspects of health that are learned and enacted individually, as opposed to being a result of living conditions or epidemics, the support for the inclusion of physical well-being as a do

Description: Social development refers to how chil

-dren and youth foster and maintain relationships with adults and peers. It also encompasses how they per

-ceive themselves in relation to others. Emotional de

-velopment is closely linked and refers to how children and youth understand and regulate their behavior and emotions. This domain also includes aspects of per

-sonality and other social skills, including communica

-tion and development of acceptable values that are important as children and youth develop both cognitive and noncognitive skills.

Policy Rationale: The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) Article 29 makes numerous refer

-ences to social and emotional outcomes as directions for a child’s education, including:

(a) The development of the child’s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential;

(b) The development of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, and for the principles enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations;

(c) The development of respect for the child’s parents, his or her own cultural identity, lan

-guage and values, for the national values of the country in which the child is living, the country from which he or she may originate, and for civi

-lizations different from his or her own;

(d) The preparation of the child for responsible life in a free society, in the spirit of understand

-ing, peace, tolerance, equality of sexes, and friendship among all peoples, ethnic, national and religious groups and persons of indigenous origin.

The DeLors Report, published by UNESCO and the International Commission on 21st Century Education (1996), lists learning to live together as one of the four types of knowledge relevant at the global level. Learning to live together encompasses empathy, curiosity and strong interpersonal skills. As part of UNESCO’s HECDI, a review of indicators for measur

-ing progress toward EFA Goal 1, found that “social competence, responsibility, respect, readiness to ex

-plore new things, pro-social and helping behaviour, capacity to follow directions, capacity to participate in individual and group work, ability to function in groups and wait for a turn, behaviour management, self-reg

-ulatory abilities, capacity to inhibit an initial response, social perception (of thoughts and feelings) and ca

-pacity to play alone or with other children” were widely regarded as important for school readiness in children age three to five (Tinajero and Loizillon 2012, 9). While this is not considered UNESCO policy, it represents the best thinking to date on the definitions of school readi

-ness at the global level.

quality education, are defined by several organiza

-tions in these terms. UNICEF includes “personal skills for developing personal agency and managing one

-self, and inter-personal skills for communicating and interacting effectively with others” in its definition of life skills. UIS includes “working in teams, network

-ing, communicat-ing, negotiat-ing, etc.” in its definition. Another example is growing global interest in social capital, which can be taken as a measure of a person’s embeddedness within a society and has emerging im

-plications for policy (Policy Research Initiative Project 2005).

Social and Emotional: Early Childhood

Level

Research Rationale: The development of social and emotional competence is critical to a child’s experi

-ence in their home, school and the larger community. Social and emotional development is important not only for relationships but also for cognitive develop

-ment and academic achieve-ment in the early school years (Romano et al. 2010), school completion, early school leaving and social adjustment in later years (Parker and Asher 1987). If a minimal level of social competence is not achieved by the age of six, it is probable that the child will be at risk for any number of social challenges and obstacles for the remainder

of his or her life (Copple and Bredekamp 2009; Ladd and Dinella 2009). Early childhood socioemotional dif

-ficulties are often precursors to diagnosable mental health problems in adolescence (Essex et al. 2009). A gradient in composite measure of child socioemotional competence in early childhood (self-control) predicted children’s socioeconomic status, health, marital sta

-tus and criminal conviction in adulthood (Moffitt et al. 2011). Although the indicators for social and emotional development may vary depending on the age group or the cultural context, a number of general domains can be adapted globally. The subdomains listed below are

research- and evidence-based and have been used in

various international contexts and curricula.

Consultation Rationale: Most contributors were strongly supportive of the social and emotional domain in early childhood. They suggested a variety of subdo

Subdomains of the Social and Emotional Domain for Early Childhood

Subdomains Description

Self-regulation

Self-regulation refers to the ability to regulate and control one’s emotions, behav

-iors, impulses and attention according to the corresponding developmental stage and cultural or social environment. In older children, this may refer to the ability to follow simple rules, directions and routines as well as the capacity to move through transitions between activities with minimal adult direction.

Emotional awareness

Emotional awareness involves understanding how emotions affect personal be

-havior and relationships with others. Emotional expression is the way in which one displays or experiences states of emotions. Emotional regulation is the capacity or ability to identify and control emotions.

Self-concept and

self-efficacy

Self-concept and self-efficacy refer to a child’s awareness of his or her prefer

-ences, feelings, thoughts and abilities. Self-efficacy means developing confidence in one’s competence and ability to accomplish tasks, which includes acknowledg

-ment of one’s limitations without loss of self-esteem. This also includes starting to demonstrate age-appropriate independence in activities and tasks.

Empathy Empathy refers to the ability to understand the feelings of others by relating them to one’s own emotions.

Social relationships and behaviors

Social relationships and behaviors refers to how a child interacts and communi

-cates with familiar adults and peers. Ideally, children establish age-appropriate, secure attachments to trusted adults and friendships with peers. They respond to emotional cues and use age- and socially appropriate behavior when interacting with adults and peers. Social relationships at this age may also include cooperat

-ing and work-ing together, shar-ing, tak-ing turns and help-ing. Children begin to rec

-ognize the need to compromise and negotiate.

Conflict resolution Conflict resolution refers to the extent to which a child uses nonaggressive and appropriate strategies to resolve interpersonal challenges and differences. Conflict -can be resolved alone or with the intervention of an adult, an older child or a peer.

Moral values

Moral values refers to a child’s framework for moral behavior by developing moral

-ity, or a system for assessing human conduct, and moral ident-ity, how moral values influence decisionmaking. Children reflect on the deeds and misdeeds conducted individually and by others (i.e., right or wrong behavior), consider motivation be

Social and Emotional: Primary Level

Research Rationale: Research shows that social and emotional development is important for relation

-ships, cognitive development and academic achieve

-ment in the early school years (Romano et al. 2010), and predicts school completion, early school leaving and social adjustment in later years (Epstein 2009; Parker and Asher 1987). According to CONFEMEN (1995), alongside the acquisition of academic knowl

-edge (reading, writing, numeracy and problem solv

-ing), schools must help students develop social skills, including interpersonal skills, the ability to change, the acquisition of ethical values and cultural norms, and the ability to resolve conflicts and coexist with others. These skills are both cognitive acquisitions and trans

-ferable skills to other life situations.

Social skills and abilities form a foundation for how well one succeeds in life and uses skills in other do

-mains. Such skills are in most instances acquired through a socialization process that happens in social organizations and institutions, such as the family, the household, religious institutions, schools and the work

-place. In addition to being learned naturally in these environments, these skills can also be taught and learned (Ross and Spielmacher 2005; Thompson and Goodman 2009).

Consultation Rationale: There was agreement among those consulted that social and emotional com

-petence was critical in its own right and also in how it is related to other aspects of learning. One consultee stated the importance of integrating social and emo

-tional learning with other content areas: “The mate

-rial taught must be meaningful, understandable, and relevant to the child’s life outside the school fences. This will make education more meaningful to the life of the graduates. The skills imparted should help our fu

-ture graduates function more effectively in tomorrow’s world. Democracy is gaining mileage in most of the countries of the world. Citizens of a democratic world need the ability to make sound, moral judgments, to think critically and to defend one’s position rationally. All these reinforce the importance of the scholastic and ethical aspects of teaching thinking within the educa

-tion system.”

Subdomains of the Social and Emotional Domain for the Primary Level

Subdomains Description

Social and community values

Social and community values refers to knowledge and use of life skills, including communication, decisionmaking, assertiveness, peer resistance, self-awareness, negotiation, friendship, self-esteem, advocacy for inclusiveness and nondiscrimi

-nation, and emotional intelligence.

Civic values

Civic values refers to knowledge and understanding of social and political con

-cepts, such as democracy, justice, equality and citizenship. It may also include the ability to defend respect for rules and guidelines and propose modification appro

-priate to contexts in school, home and community.

Mental health and well-being

Social and Emotional: Postprimary Level

Research Rationale: There is an increasing rec

-ognition of the roles of social as well as emotional competencies for career success, fulfillment of civic responsibilities and effective family living. However, owing in part to ease of measurement, the cognitive domain has continued to attract more research efforts. The fluidity and complexity of the affective domain present significant measurement challenges in work

-place, civic and leadership studies, with the result that it remains a weak link in the education of the whole person. There is a demonstrable complexity of varied influences on the development of civic competencies across countries (Hoskins et al. 2011) and prerequi

-site soft skills for different work/social settings (Harris and Rogers 2008). These complexities and measure

-ment challenges lend credence to multidisciplinary approaches and mixed research methods to pursuing studies of social and emotional issues.

Globalization and the use of the Internet have high

-lighted the diversity in social/emotional relationships among the world’s peoples and concurrently promote acculturation of the population exposed to the Internet. There is abundant evidence to show the influence of social networks on the socialization process, civic en

-gagement (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, LinkedIn, etc.) and workplace networking (Coulby 2011; Blais et al. 2008; Ono 1996). The more accessible the Internet be

-comes globally, the more important it will be to conduct research to determine how communities will respond to a heavy dose of social exchanges among different cultures, since it is usually the privileged and the lead

-ership of most communities that experience external contacts. In this case, the leaders will have to decide how social issues—such as gender in the workplace, changing family structure and emotional intelligence for career success—will play out in the struggle for or

-ganizational, communal and global identity.

As complex as social and emotional issues are in rela

-tion to any global standards, Gardner’s theory of mul

-tiple types of intelligence (Williams 2007), especially intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligence, will help educators and researchers conceptualize how best to train for these competencies. In a world of increasing social intricacy and knowledge explosion, training the workforce as well as the citizenry on how to develop social and emotional maturity/intelligence has never been so imperative for career success and sustainable family life.

Consultation Rationale: There was strong support in the consultation for the view that people need to under

-stand their place within, and responsibility to, society. This responsibility will sometimes include exercising leadership. One respondent included a considerable list of potential subdomains, including “critical thinking and decisionmaking, ethical values and cultural norms, human rights and responsibilities and humanitarian norms and respect for diversity/coexistence.” There was a great deal of interest in finding a way to include the management of human and social relationships as a significant learning outcome, though there was also a cautionary note that “social and civic awareness com

-petencies may be particularly difficult areas in which to develop consensus on measures.”

A number of respondents made the point that indi

-vidual engagement is an important precursor of social engagement, and that people need to have a mature and positive view of the self. Accompanying this idea is the notion of aspiration for a better quality of life for the individual and more broadly, which can help to provide a basis for social and emotional interactions. Overall, consultation underlined the importance of this domain very clearly, while recognizing the difficulty of concep

Subdomains of the Social and Emotional Domain for the Postprimary Level

Subdomains Description

Social awareness Social awareness is the ability to understand and respond appropriately to the social environment.

Leadership Leadership is the ability to make decisions and act on those decisions autonomously or collaboratively as appropriate.

-Civic engagement Civic engagement is taking a responsible role in the management of society at the community level and beyond.

Positive view of self and others

Positive view of self and others reflects the aspiration to a high quality of life for individuals, their families and their community.

Resilience and grit

Resilience and grit refer to the ability to overcome failures and persist, even when it is difficult to do so. It refers to having a positive attitude and understanding that one can learn from failures and mistakes.

Moral and ethical values

Moral values are attributed to a system of beliefs, either political, religious or cul

-tural. Ethical values refers to the actions one takes in response to his or her values.

Social sciences

Social science is the understanding of society and the manner in which people behave and influence the world around them. It refers to the ability to analyze our

Description: The arts in the realm of education are often described as creative arts expression, and can include activities from the areas of music, theater, dance or creative movement, and the visual, media and literary arts. The foundation for learning in history and social science is built on children’s cultural experi

-ences in their families, school, community and country.

Policy Rationale: Although the arts are critical to education strategies, the frameworks and policies,

research and resources devoted to arts education

and integration have received less attention as com

-pared with other domains. UNESCO’s Road Map of Arts Education, formed at the World Conference on Arts Education in Lisbon, March 6–9, 2006, was an international attempt to integrate creative and cultural development into global education policies and to draw attention to arts education. The domain of arts and culture is critical to other global education initiatives, as can be seen through direct references in policies and frameworks from EFA to the CRC framework, to UNESCO’s Declaration on Cultural Diversity (2001). These documents recognize that the arts provide a means for improving the quality of teaching and learn

-ing, as well as supporting increased access through participation and retention of learners.

Cultural and artistic content and approaches in learn

-ing are critical to achiev-ing global education policies such as the EFA and CRC frameworks, as well as UNESCO’s Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity (2001). EFA Goal 6—Improving every aspect of

qual-ity education, and ensuring their excellence so that recognized and measurable learning outcomes are achieved by all, especially in literacy and numeracy and essential lifeskills—is supported by a number of requirements that are well aligned with arts education’s evidence-based outcomes, including: motivating stu

-dents (requirement 1), providing teachers with active learning techniques and approaches (requirement 2), enhancing the quality and relevance of teaching and learning materials and environments (requirement 3), building on the experience of local cultures and ex

-periences of teachers and learners (requirement 4), promoting an environment that is culturally sensitive and safe (requirement 6), and fostering respect and a means of engaging local communities and cultures in the education community and process (requirement 8) (UNESCO 2000).

Cultural and arts education programming also sup

-ports CRC’s Articles 29 and 31 (United Nations 1989).

Article 29: (a) The development of the child’s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential;

(c) The development of respect for the child’s parents, his or her own cultural identity, lan

-guage and values, for the national values of the country in which the child is living, the country from which he or she may originate, and for civi