Clinical

Paper

Oral

Surgery

Effect

of

pre-emptive

analgesia

on

clinical

parameters

and

tissue

levels

of

TNF-

a

and

IL-1

b

in

third

molar

surgery:

a

triple-blind,

randomized,

placebo-controlled

study

A.F.M.Albuquerque,C.S.R.Fonteles,D.R.doVal,H.V.Chaves,M.M.Bezerra,K. M.A.Pereira,P.G.deBarrosSilva,B.B.deLima,E.C.S.Soares,T.R.Ribeiro,F.W. G.Costa:Effectofpre-emptiveanalgesiaonclinicalparametersandtissuelevelsof TNF-

a

andIL-1b

inthirdmolarsurgery:atriple-blind,randomized, placebo-controlledstudy. Int.J.OralMaxillofac.Surg.2017;xxx:xxx–xxx. ã 2017 InternationalAssociationofOralandMaxillofacialSurgeons.PublishedbyElsevier Ltd.Allrightsreserved.A.F.M.Albuquerque1,2,

C.S.R.Fonteles3,D.R.doVal4, H.V.Chaves5,M.M.Bezerra5, K.M.A.Pereira3,

P.G.deBarrosSilva6,

B.B.deLima7,E.C.S.Soares3, T.R.Ribeiro3,F.W.G.Costa1 1

Post-graduatePrograminDentistry,School ofDentistry,FederalUniversityofCeara´, Ceara´,Fortaleza,Brazil;2DivisionofOral Surgery,SchoolofDentistry,Fortaleza University(UNIFOR),Ceara´,Fortaleza, Brazil;3Post-graduatePrograminDentistry, SchoolofDentistry,FederalUniversityof Ceara´,Ceara´,Fortaleza,Brazil;4Renorbio Post-graduateProgram,FederalUniversityof Pernambuco,Recife,Pernambuco,Brazil; 5Post-graduatePrograminHealthScience, MedicalSchool,FederalUniversityofCeara´, Sobral,Ceara´,Brazil;6DivisionofOral Surgery,SchoolofDentistry,Fortaleza University(UNIFOR),Ceara´,Fortaleza, Brazil;7DivisionofOralSurgery,Walter Cantı´dioUniversityHospital,Ceara´, Fortaleza,Brazil

Abstract. Thisstudyaimedtoevaluatewhetherpre-emptiveanalgesiamodifiesthe tissueexpressionoftumournecrosisfactoralpha(TNF-a)andinterleukin1beta (IL-1b),andwhetherthereisanassociationwithpostoperativesurgicaloutcomes. Atriple-blind,randomized,placebo-controlledstudyofpatientsundergoing mandibularthirdmolarremovalwasperformed.Volunteerswereallocated randomlytoreceiveetoricoxib120mg,ibuprofen400mg,orplacebo1hbefore surgery.Twenty-foursurgicalsitespergroupwererequired(95%confidencelevel and80%statisticalpower).Pain scoresdifferedsignificantly betweengroups (P<0.001).Etoricoxibandibuprofenreducedpainscorescomparedtoplacebo

(P<0.05).Painscorespeakedat4hpostoperativeintheexperimentalgroups,but

at2hpostoperativeintheplacebogroup(P<0.05).Asignificantreductionin

TNF-aconcentrationfromtime00totime300wasseenforibuprofen(P=0.001) andetoricoxib(P=0.016).Theibuprofengroupshowedasignificantreductionin IL-1blevelsfromtime00totime300(P=0.038).Inconclusion,TNF-aandIL-1b levelsandtheinflammatoryeventsinthirdmolarsurgerywereinverselyassociated withthe degreeofcyclooxygenase2selectivityofthenon-steroidal anti-inflammatorydrugsusedpre-emptively.Patientsgivenpre-emptiveanalgesia showedsignificantreductionsintheclinicalparameterspain,trismus,andoedema whencomparedtothe placebogroup.

Key words: thirdmolar; inflammatoryevents; TNF-a;IL-1b;non-steroidalanti-inflammatory drugs.

Acceptedforpublication

Int.J.OralMaxillofac.Surg.2017;xxx:xxx–xxx

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2017.05.007,availableonlineathttp://www.sciencedirect.com

Thesurgicalremovalofmandibularthird molarsisoneofthemostcommonly per-formeddentalproceduresintheoutpatient setting.Thelevelofdentalimpactionmay beexplainedbythelackofphysicalspace foreruption.Thisis usuallytheresultof thesizeofthemaxillarybonebeing insuf-ficienttoproperlyaccommodateallteeth presentwithinthearch.Thus,thirdmolar extractionisaprocedurecommonly relat-ed tolocal tissueinjury,associatedwith varyingdegreesofpostoperativepain1–3. Fromaclinicalperspective,theremoval ofsuchteethcanaffectthepatient’s qual-ity of life postoperatively, particularly duringthefirst3days,duetotheintensity ofpainandinflammationarisingfromthe surgical procedure. Approximately 40– 60%ofthesepatientsexperiencemoderate toseverepain,requiringtheuseofrescue analgesics4–6.Inthiscontext,pre-emptive analgesia is used as a pharmacological strategy for the management, reduction, oreven preventionofpostoperativepain relatedtodentalprocedures.Thisstrategy ofpaincontrolhasbeenstudiedwidelyin recentdecades7.

Inadditiontopain,oedemaandlimited mouthopening(trismus)arethe postoper-ativecomplicationsmostcommonly asso-ciated with the removal of mandibular third molars. These clinical signs and symptomsresultfromalocal inflammato-ryprocessgeneratedbytheactivationof the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway and thesubsequentincreaseinlevelsof pros-taglandinswithintheinjuredsite.Bothof theseplayimportantrolesinthereleaseof proinflammatory cytokines (tumour ne-crosis factor alpha (TNF-

a

), interleukin 1(IL-1),andinterleukin6(IL-6))related tothepathophysiologyofpainand inflam-mation8,9.Clinicalandexperimentalstudies eval-uating the pathogenesis of inflammation resultingfromthirdmolarsurgery,aswell astheroleoftheinflammatorymediators implicatedinthesubsequentprocessesof painandinflammation,areextremely rel-evant and currently warranted. Certain mechanisms have been proposed to ex-plain the inflammation that occurs as a resultofsurgicalprocedures,buta com-plete understanding of howthese events arefullytriggeredremainsunclear. Proin-flammatorycytokinessuchasTNF-

a

and interleukin1beta(IL-1b

)haveoftenbeen described as importantmediators in this process10–13.Experimentalstudies involv-ingacutepainmodelssuggestthatIL-1b

sensitizes nociceptorsand causes hyper-algesia,thereforeworkingactivelyinthe pathophysiologyofthistypeofpain14–16.On the other hand, it is recognized

that TNF-

a

exerts remarkable effects, includingactivatinglymphocytes, stimu-lating the synthesis of other proinflam-matorycytokinessuchasIL-1b

andIL-6,and triggering the production of

prostaglandins17–21.

Althoughclinicalstudies have investi-gated the effectiveness of pre-emptive analgesia in third molar surgery22–26, it is currently highly relevant to publish translational studies aimed at assessing theinfluenceofthepreoperative adminis-trationofnon-steroidalanti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)on thepathophysiology ofinflammatoryeventsestablishedwithin theseclinicalsituations.Anotherquestion thathasyettobeanswerediswhetheror not the selectivity of NSAIDs to COX isoforms may render different effects in the expression ofproinflammatory cyto-kinessuchasTNF-

a

andIL-1b

inthese surgicalsituations.Therefore,thisstudyaimedtotest the hypothesis that preemptive analgesia, through the administration of NSAIDs prior totheremoval ofmandibularthird molars,canquantitativelychangethe tis-sue expression of TNF

a

and IL1b

, andthatthesechangesmayberelatedto clinical effects (pain, oedema, and tris-mus)postoperatively.Materialsandmethods

Studydesignandsample

This study was approved by the Ethics CommitteeofWalterCantı´dioUniversity Hospitalandwasperformedinaccordance with the Helsinki statements. A tri-pleblind,randomized, crossover, place-bocontrolledstudyofpatientsundergoing mandibular third molar extractions was performed. These patientswererecruited from the Division of Oral and Maxil-lofacialSurgeryofWalterCantı´dio Uni-versityHospitalattheFederalUniversity of Ceara´ (Brazil). The volunteers were

recruited between March 2014 and

December 2015 according to the

CON-SORT protocol27.

Thesampleunitusedinthisstudywas the surgical site. Healthy individuals (American Society of Anesthesiologists, ASA 1)of bothsexes,aged between 18 and 35 years, requiring the removal of bothmandibularthirdmolars,were invit-edtoparticipateinthisstudy.

The following inclusion criteria were adopted tostandardize the levelof trau-matic injury generated by surgery: (1) patientswiththirdmolarsrequiring ostect-omy, with or without associated tooth sectioning;(2)patientswiththirdmolars

thatshowed similarpatternsofroot for-mation,position,anddegreeofimpaction. Patientswereexcludediftheymetanyof thefollowingcriteria:smokers,pregnant orbreastfeeding,usersofmedicationsthat couldinteractwiththedrugsusedinthis study,patientswithorthodonticbandson themandibularsecondmolars,confirmed historyofallergytoNSAIDs,signsofany preoperative inflammatory or infectious condition, systemic chronic disease, use ofNSAIDswithinthepast21days,orthe presenceofperiodontaldisease,swelling, fever,ortrismuspriortosurgery.Patients whodidnotfollowtherecommendations prescribed,who underwent surgical pro-cedures that exceeded 2h, who had an intolerance to the pharmacological regi-men,whopresentedapostoperative infec-tion, and those who did not return for postoperative assessment consultations wereremovedfromthestudy.

Allrecruitedindividualswereinformed abouttheobjectivesandstudydesign,and thosewhoconsentedtoparticipatesigned awritteninformedconsentagreement.

Samplesizecalculation

Thesamplesizecalculationwasbasedon thatdescribedinthestudyconductedby Al-Shukun et al.26. These authors ob-servedanegativeresponsetothe pharma-cological treatmentinstituted of 58% in thecontrolgroupand18%inthe experi-mentalgroups.Thus,24samplesof gin-gival tissue per group were required to conductthisclinicaltrialandstatistically rejectthenullhypothesiswith80%power and a 95% confidence interval. For this samplecalculation,thetype1error asso-ciatedwiththetestwas0.05;the

x

2test without correction was used to evaluate thenullhypothesis.Interventions

Thefollowing data were collected prior tosurgery:sex,age,generalhealthstatus, periodontal condition, and intraoral and extraoralaspectsofthedentalimpaction.

A panoramic radiograph was acquired

and the tooth position according to the classificationsofPellandGregory28 and Winter29, degree of tooth development, andlevelofimpactionwererecorded.

The surgical procedures were

scheduled1weeklater.Hence,thesecond surgery was performed28days afterthe first(wash-outperiod).

Inordertoexcludeapossible confound-ing factor, it was established that both surgical sites in the same patient could notbeallocatedtoasingleexperimental group. Each treatment was coded as a differentgroup,andgroupswereidentified withthelettersA,B,orC.Basedonthe nomenclatureoftheblindedgroups previ-ously provided to the statistician, six

blocks of combinations were created

(AB, BA, BC, CB, AC,and CA). Each

blockrepresentedthetreatmentthatwould beadministeredpriortotheremovalofthe right and left mandibular third molars,

respectively. They were randomized

throughacomputer-generated randomiza-tioncodeinMicrosoftExcel,confirming that each patient received two different medications.Thedrugsusedinthisstudy

were etoricoxib 120 mg, ibuprofen

400mg, and placebo (without active

drug).Themedicationswereadministered 1hbeforesurgery.Noantibiotic prophy-laxiswasadministeredtothevolunteers.

Allpatients underwent a standardized surgical technique, performedinan out-patientsetting,followingastrictbiosafety protocol. A surgeon with experience in oral andmaxillofacial surgeryperformed all ofthe surgical procedures. The same surgicalprotocolwasadoptedforbothsides of the mouth, with the aim of reducing differences in the level ofintraoperative trauma.Thethirdmolarremovalwas per-formedunder localanaesthesia with me-pivacaine 2% andepinephrine1:100,000 (DFL,RiodeJaneiro,Brazil),usinga max-imumofthree1.8-mlcartridges.

A triangular full-thickness flap was raised,followedbyperipheralostectomy usingahigh-speedhandpieceunder irri-gationwithcooleddouble-distilledwater. One sample of softtissue was collected from theregion distaltothe thirdmolar before thesurgical flapwas raised(time 00)and a second soft tissuesample was obtained30minafterthesurgical proce-dure(time300)forthelaboratoryanalysis of cytokines. The surgical wound was closedwitha4–0silksuture.

After surgery, ibuprofen 300mg was prescribed as rescue analgesic, to be taken at intervals of 8h. Postoperative instructionswerealso carefullyreadand explained to the patients. They were instructed to maintain a liquid and soft diet and to avoid hot liquids and/or foodsduringthefirst24h,andtoperform careful oral hygiene without vigorous mouthwashes in order to prevent post-surgical bleeding. The patients were

instructedtocontactthesurgeonby tele-phoneinthecaseofpersistentbleeding,or if theydeemed itnecessary. Inaddition, thepatientswerealsoaskedtoreportany physical symptoms experienced during thepostoperativeperiodofthestudy,such asnausea,vomiting,dizziness,headache, insomnia,andsignsofinfection.

Outcomemeasures

Theprimaryoutcomeofthestudywasthe occurrenceofpostoperativeinflammatory events(pain,facialoedema,andtrismus). The intensity of postoperative pain was measured using a visual analogue scale (VAS)of10cm,with0representingthe absence of pain or discomfort and 10 representing the maximum pain or dis-comfort. After the surgical procedure, eachpatientreceivedastandardizedform withtheVAStoreportpostoperativepain values. Study participantswere askedto marktheintensityoftheirpainat0,2,4,6, 8,10,12,24,48,and72h,aswellason days 5 and 7 after surgery. In addition, data werecollectedonthe useofrescue

medication, including: (1) the time

elapsed between the end of the surgical procedure andtheingestionofthe medi-cinebythepatient;(2)numberofrescue analgesicconsumed.

Postoperative oedema was measured

using lines drawn between facial points (Fig.1).Thesewerethedistancesfromthe mandibular angle (MA) to: (1) tragus (MA–Trdistance),(2)externalcornerof the eye (MA–ECE distance), (3) nasal border(MA–NBdistance),(4)labial com-missure (MA–LC distance),and (5) soft pogonion (MA–SPdistance).The preop-erativevaluesandthoseobtainedat24h, 72h,and 7days after surgerywere ana-lyzed.

Furthermore, to estimate the degree

of mouth opening, the maximum mouth

opening was measured in the pre- and postoperative periods (after 24h, 72h, and 7 days) by measuring the distance inmillimetresbetweentheupperand low-ercentralincisorsusingacalibratedruler. The secondary outcome of this study wastheoccurrenceofchangesinthetissue levelsofTNF-

a

andIL-1b

ineachstudy group.The gingivaltissuesamples were storedat80CinEppendorftubes con-tainingRadio-ImmunoprecipitationAssay solution(SantaCruzBiotechnology,Santa Cruz, CA,USA) until required for each assay. Thecollectedtissuewas homoge-nized and followed by centrifugation (10,000rpm/10min/4C). The superna-tantwasusedtodeterminetheexpression levels of TNF-a

and IL-1b

by ELISAmethod, using commercial kits

(Quanti-kine Human TNF-

a

Kit (catalogueDY210) and Quantikine Human IL-1

b

/IL-1f2Kit (catalogueDY201); R&Dsystem, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The

assayswereperformedinaccordancewith themanufacturer’sinstructions.Thelevels of TNF-

a

and IL-1b

were recorded in picogramspermillilitre(pg/ml).Randomization

Themethodusedtogeneratetherandom allocation sequence was the function ‘randbetween’ in MicrosoftExcel, 2010 version.Therandomizationwasbasedon simpletype, withoutanyrestriction.The mechanismusedtoimplementtherandom allocation sequence was envelopes that stated the numbers ofrandomization on the outside. These envelopes contained informationspecifyingthegrouptowhich thepatientwouldbelong.Acollaborating researcherwhodidnotparticipateinthe surgical procedures was responsible for generating the random allocation se-quence, as well as for organizing and distributingtheparticipantsineachgroup.

Blinding

Through the blinding protocol used in this study, the patient, researcher, and statistician didnotknowtowhichgroup eachpatientbelonged.Beforethesurgical

Fig.1. Linearmeasurementsforthe

assess-ment of postoperative oedema: mandibular

angle(MA)to:(1)tragus(MA–Trdistance),

(2) external corner of the eye (MA–ECE

distance),(3)nasalborder(MA–NBdistance),

(4)labialcommissure(MA–LCdistance),and

procedures, a list containing the random distributionofallsurgicalsitesand respec-tivemedicinestobeadministeredwaskept inasealedenvelopebyanexternal collab-oratorwhoremainedunawareofthestudy protocoluntilthedataanalysis.The statis-ticalanalysiswasinitiallyperformedwith groups encodedwiththeletters ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’,which represented the different groupsstudied.Thesecodeswererevealed attheendofthestudy.

Statisticalanalysis

Thedatawereexpressedasthemeanand standard deviation and submitted to the

Kolmogorov–Smirnovnormalitytestprior tofurtheranalysisbyKruskal–Wallistest followedbytheDunnorWilcoxon post-hoctest(non-parametricdata),orone-or two-way analysisofvariance (ANOVA) forrepeated(ornot)measuresfollowedby the Bonferronipost-hoc test (parametric data). Pearson’scorrelation analysiswas used to assess the correlation between the sum ofthepain scoresandthe total

consumption of rescue medication

(parametricdata), andSpearman’s corre-lation analysis was used to assess the correlation with the levels of cytokines (non-parametric data). Categorical data wereanalyzedby

x

2test.Allanalyseswereperformedin Graph-PadPrism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego,CA,USA)adoptinga95% confi-dence interval; P<0.05 was considered

statisticallysignificant.

Results

Samplecharacterization

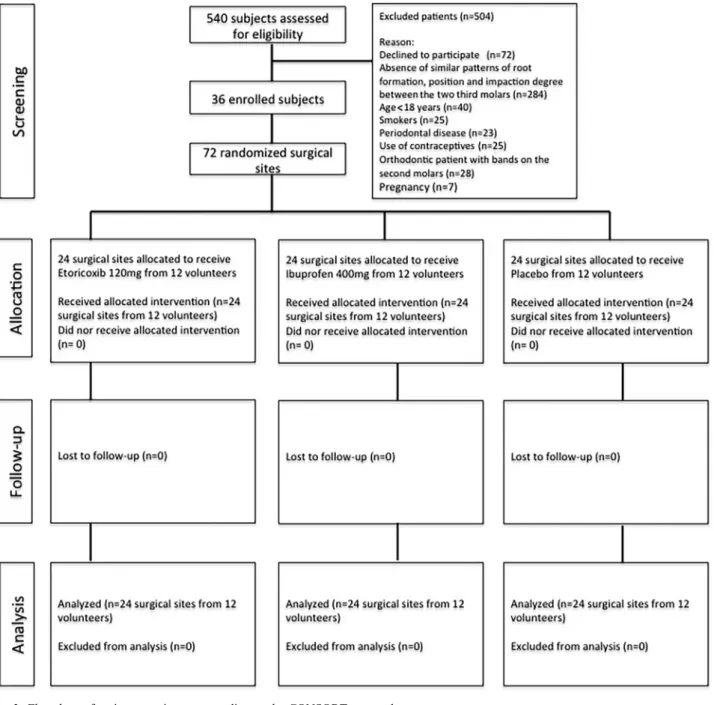

Atotalof540patientswerescreenedfor studyeligibility(Fig.2).Fromthistotal, 504 individuals were excluded because theydidnotmeetthestudycriteria.The finalsample wascomposedof36 volun-teers(16male,44.4%;20female,55.6%),

foratotalof72surgicalsites,dividedinto 24procedurespergroup.

There were no statistically significant differences in clinical, radiographic, or surgical characteristics between the groups(P>0.05);thelevelofoperative

difficulty wassimilaracrossthe surgical procedures. The distribution of surgical sitesdidnotdifferbetweenmales(9 pla-cebo, 11 ibuprofen, 12 etoricoxib) and females (15 placebo, 13 ibuprofen, 12 etoricoxib)(P=0.590).Therewasno sta-tistically significant difference in age group distribution between the groups (P=0.436):<20years(4placebo,1

ibu-profen, 5 etoricoxib), 20–30 years (19 placebo, 21 ibuprofen, 16 etoricoxib),

>30 years (1 placebo, 2 ibuprofen, 3

etoricoxib).Therewasalsonostatistically significantdifference betweenteeth with totalboneinclusion(5placebo,7 ibupro-fen, 8etoricoxib), partialbone inclusion (11 placebo, 6 ibuprofen, 7 etoricoxib), andsemiinclusion(8placebo,11 ibupro-fen,9etoricoxib)(P=0.490).

WhenconsideringthePellandGregory classification regarding the amount of tooth covered by the anterior border of theramus,nodifferenceswereidentified between thegroups(P=0.817):placebo (12classI,11classII,1classIII), ibupro-fen(15classI,9classII,0classIII),and etoricoxib (14 classI, 9classII,1 class III).Inaddition,therewerenodifferences betweenthegroupsregardingthe impac-tiondepthrelative totheadjacent tooth: placebo(11classA,12classB,1classC), ibuprofen(15classA,8classB,1classC), andetoricoxib(10classA, 13classB,1 class C) (P=0.787). Tooth position accordingtotheWinterclassificationdid notdifferbetweentheplacebo(11vertical, 8mesioangular,1distoangular,4 horizon-tal),ibuprofen(13vertical,5mesioangular, 1 distoangular, 5 horizontal), and etori-coxib (9vertical,8 mesioangular, 0 dis-toangular,7horizontal)groups(P=0.614).

The need for tooth sectioning during surgerydidnotdifferbetweenthegroups: placebo (12 presence, 12 absence), ibu-profen (11 presence, 13 absence), and etoricoxib (12 presence, 12 absence) (P=0.829). The total number of anaes-theticcartridgesusedrangedfrom1.5to2, with no difference between the groups (P>0.05). Furthermore, the time

re-quired for third molar removal (range 10–40min) did not differ between the groups(P=0.875).

Analysisofpain

The mean time to the need for rescue medication was significantly reduced intheetoricoxib(2.01.8h)and ibupro-fen(2.61.1h)groups,whencompared

to the placebo group (4.51.7h)

(P<0.001),buttherangeofmouth

open-ing did not differ between the groups (P=0.682).

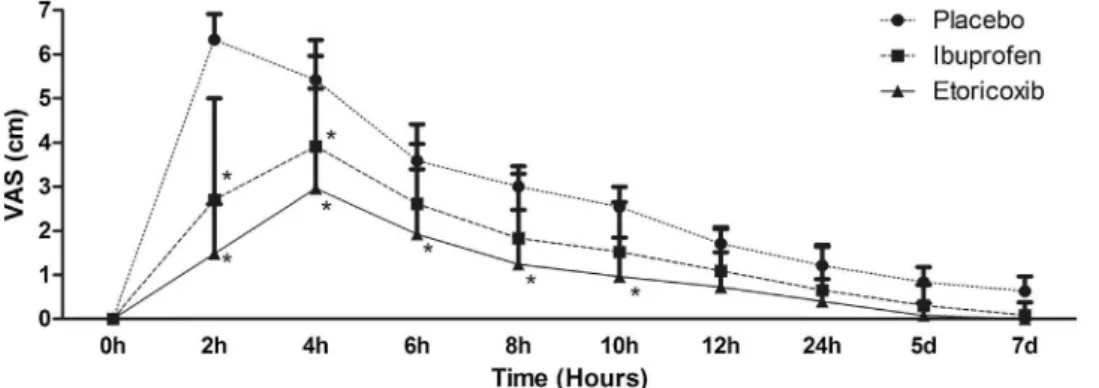

Theplacebogrouppresenteda signifi-cantlyelevatedpainpeakafter2h(VAS 6.32.9), and the groups treated with ibuprofen andetoricoxib showed signifi-cantly elevated pain peaks at 4h after the surgical procedure (3.92.4 and 3.02.3,respectively)(Fig.3).Thepain peakreducedsignificantlyinbothgroups at6haftertheendofsurgery(3.61.9in

the placebo group, and 2.61.8 and

1.91.5fortheibuprofenandetoricoxib groups, respectively) (P<0.001). The

grouptreatedwithibuprofenshowed sig-nificantlylesspainthantheplacebogroup at2hand4haftersurgery,andthegroup treated with etoricoxib showed signifi-cantly less pain than the placebo group at 2h, 4h, 6h, 8h, and 10h following surgery (P<0.001). The cumulative

effect of all scores up to 6h and

12h postoperatively was significantly lower in the ibuprofen group (2.32.3 and 1.51.8, respectively) and

etori-coxib group (1.61.8 and 1.01.4,

respectively), when compared to the

placebo group (3.83.2 and 2.52.8, respectively)(P<0.001).Thegroup

trea-ted with etoricoxib showed a lower

meanaccumulatedpainduring12hwhen compared tothe group treatedwith ibu-profen(P<0.001).

Thetotalconsumptionofrescue analge-sicsshowedastatisticallysignificant cor-relationwiththesumofthepainscoresin allgroups(placebo:P=0.019,r=0.495; ibuprofen: P=0.027, r=0.492; etori-coxib:P=0.011,r=0.509).

Analysisofoedema

MeasurementofMA–Trshoweda

signifi-cant increase in the placebo (65.7

9.4mm), ibuprofen (61.67.3mm),

and etoricoxib groups (58.35.1mm) at24haftersurgery,followedbya signif-icant reduction in the placebo group

after 7 days (60.065.0mm), while

the ibuprofen and etoricoxib groups

showed asignificantreduction after72h

(59.55.0mm and 57.24.5mm,

re-spectively) (P<0.001). ThemeanMA–

Trdistancewassignificantlylowerinthe grouptreatedwithetoricoxibwhen com-pared to the placebo at 24h and 72h postoperatively(P<0.001).The

cumula-tive effect of all the mean MA–Tr dis-tances within the different postoperative

times in the placebo group (61.9

8.0mm) showedahigher valuethan the

ibuprofen group (59.65.7mm) and

etoricoxib group (57.24.7mm), while the etoricoxib group had a lower value thantheibuprofengroup(P<0.001).

TheMA–ECEpeak measurementwas

significantly increased at 24h after the

surgical procedure in the placebo

(107.88.2mm), ibuprofen (105.7

6.9mm),andetoricoxibgroups(105.4

7.0mm), and demonstrated a significant reduction inthe ibuprofengroup after 7 days(103.26.2mm)andintheplacebo

Fig.3. Painintensitymeasuredonavisualanaloguescale(VAS,cm)accordingtothestudygroupsandspecificpostoperativetimeintervals.Data

andetoricoxibgroupsafter72h(105.6

6.0mm and 104.26.2mm,

respec-tively). The etoricoxib group (103.4

6.2mm)expressedsignificantlyless oede-maat7daysaftersurgerywhencompared to the placebo group (104.05.6mm) (P=0.004). However, the cumulative effect of the MA–ECE distance did not differ between the three study groups (P=0.568).

The peak MA–NB measurement was

significantly increased at 24h after the

surgical procedure in the placebo

(118.38.7mm), ibuprofen (114.0

6.8mm),andetoricoxibgroups(113.5

8.5mm),andreducedsignificantlyinthe placebogroupafter72h(115.37.0mm) andintheibuprofen(108.67.5mm)and etoricoxibgroups (110.27.7mm)after 7 days. The cumulative effect of all theMA–NBmeasurementswas

significant-ly reduced in the ibuprofen group

(110.97.3mm) and etoricoxib group

(111.67.9mm) when compared to

the placebo group (114.37.9mm)

(P=0.007).

The peak MA–LC measurement was

significantly increased 24hafter surgery intheplacebo(101.89.3mm),

ibupro-fen (94.47.1mm), and etoricoxib

groups (94.28.5mm) (P<0.001).

These peakswere significantly lower in

the ibuprofen and etoricoxib groups

(P<0.001). Theoedema peaks reduced

significantly in all groups after the first

72h (95.55.3mm, 92.76.7mm,

and92.97.8mm,respectively).The cu-mulative effect ofall MA–LC measure-ments was significantly reduced in the ibuprofen(91.17.0mm)andetoricoxib

groups (92.07.8mm) when compared

to the placebo group (94.38.1mm)

(P=0.014).

ThepeakMA–SPdistancewas signifi-cantlyincreasedat24hafterthesurgeryin the placebo(122.09.1mm),ibuprofen (116.26.8mm),and etoricoxibgroups (116.08.6mm) (P<0.001), and the

peaks were significantly reduced in

the ibuprofen and etoricoxib groups

(P<0.001). There was a significant

re-duction in oedema in the placebo

(117.77.0mm) and etoricoxib groups (114.47.4mm)after48h.The ibupro-fengroup(111.37.3mm)demonstrated a reduction inoedema after 7days.The cumulativeeffectofalltheMA–SP mea-surements was lower in the ibuprofen

group (113.27.6mm) compared to

the placebogroup(116.08.1mm).No difference in the cumulative effect of all oedema measurements was observed when comparing the three study groups (P=0.108).

Analysisofmouthopening

Thegrouptreatedwithplaceboshoweda maximummouthopeningvalueof32.1

7.0mmafter24h,witha significant im-provementafter72h(37.18.3mm)and at 7days postoperative (43.18.0mm) (P<0.001).Theibuprofenandetoricoxib

groupsshowedmaximummouthopening

values after 24h of 34.48.7mm and 39.28.4mm,respectively,with signifi-cant improvements after 7days (49.2

8.9mmand49.98.0mm,respectively) (P<0.001). Mouthopeningwas

signifi-cantly greater in the group treated with ibuprofen onday 7postoperativeand in thegrouptreatedwithetoricoxibat24h, 72h,and7daysaftersurgery,when com-pared to the placebo group (P=0.040).

The group treated with etoricoxib

(46.59.5mm) demonstrated greater

mean mouthopeningmeasurementsthan

the placebo group (40.810.0mm)

(P=0.001).

Cytokineprofiles

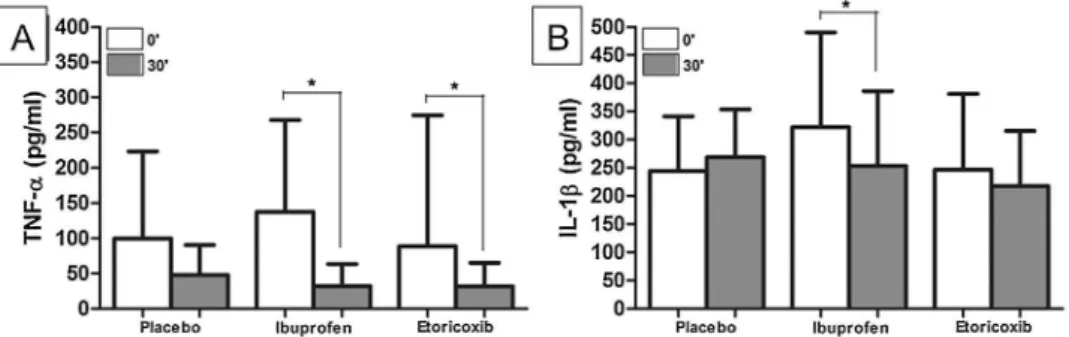

ThelevelofTNF-

a

intheplacebogroup showed nostatisticallysignificant differ-encefromtime00(99.8123.3pg/ml)to time 300 (47.742.7pg/ml, P=0.127); however, the ibuprofen (137.4130.2to 32.131.6pg/ml, P=0.001) and

etoricoxib groups (88.51.0 to 31.7

33.47pg/ml,P=0.016)showed statisti-cally significant reductions in TNF-

a

from0 to30minafter the beginning of thesurgicalprocedure(Fig.4).Therewas nosignificantdifferencebetweenthethree groupsattime00(P=0.274)ortime300 (P=0.230).Nosignificantvariations(

D

)inthelevels of IL-1b

were observed in the placebo (244.399.7to268.585.1pg/ml;P= 0.487) and etoricoxib groups (246.5134.3to 217.597.9pg/ml; P=0.593); however,therewasasignificantreduction in the levels of IL-1

b

in the ibuprofen groupfromtime00(322.0168.8pg/ml) to time 300 (253.1132.9pg/ml; P= 0.038).Therewasnosignificantdifference inthelevelsofIL-1b

betweenthethree groupsattime00 (P=0.354) ortime 300 (P=0.500).Analysisofthecorrelationbetween clinicalparametersandcytokinelevels

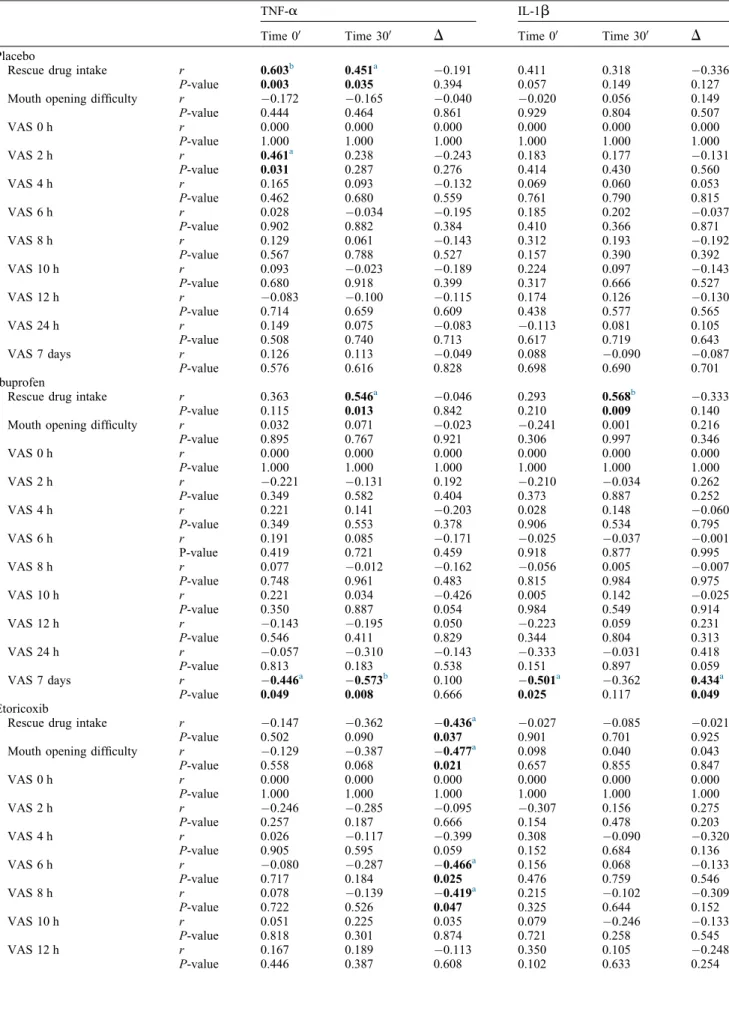

LevelsofTNF-

a

attime00(r=0.603)and at time 300 (r=0.451) were positively correlatedwiththeamountofrescue med-ication consumed in the placebo group (Table 1).The levels ofTNF-a

at time 00 also showed a positive correlation with the VAS at 2h (r=0.461). In the ibuprofengroup,theconsumptionof res-cuemedicationswaspositivelycorrelatedwith levels of TNF-

a

at time 300(r=0.546) and the levels of IL-1

b

at time 300 (r=0.568). The level of pain at7days aftersurgeryshoweda signifi-cantnegativecorrelationwith thelevels ofTNF-a

at time 300 (r=0.573) andthe levels of IL-1

b

at time 300(r=0.501),whereasthe reduction(

D

) inIL-1b

levelsshowedasignificant pos-itivecorrelation withpainlevels after7 days(r=0.434).Intheetoricoxibgroup, thevariation(D

)inTNF-a

levels corre-latedsignificantly with theconsumption ofrescuemedication (r=0.436), diffi-culty in mouth opening (r=0.477),Fig.4. Assessmentofthelevelsof(A)TNF-

a

and(B)IL-1b

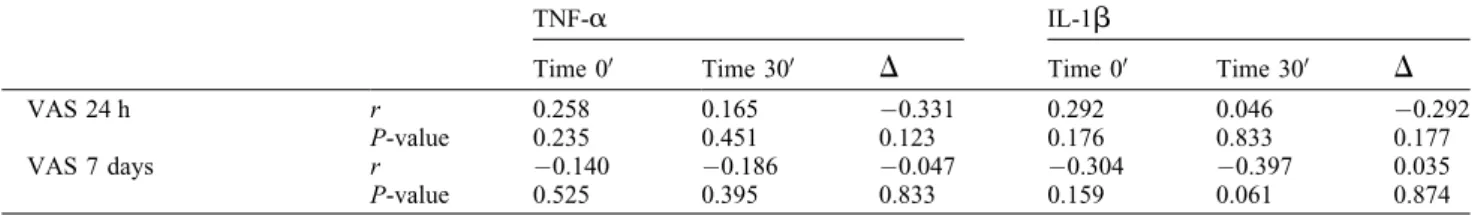

intheplacebo,ibuprofen,andetoricoxibgroupsatpostoperativetimes00and300.Table1. Analysisofthecorrelationbetweencytokineprofilesandtheirvariations(finaldosageminusinitialdosage)andclinicaldataforpain.

TNF-

a

IL-1b

Time00 Time300

D

Time00 Time300D

Placebo

Rescuedrugintake r 0.603b 0.451a 0.191 0.411 0.318 0.336

P-value 0.003 0.035 0.394 0.057 0.149 0.127

Mouthopeningdifficulty r 0.172 0.165 0.040 0.020 0.056 0.149

P-value 0.444 0.464 0.861 0.929 0.804 0.507

VAS0h r 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000

P-value 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000

VAS2h r 0.461a 0.238 0.243 0.183 0.177 0.131

P-value 0.031 0.287 0.276 0.414 0.430 0.560

VAS4h r 0.165 0.093 0.132 0.069 0.060 0.053

P-value 0.462 0.680 0.559 0.761 0.790 0.815

VAS6h r 0.028 0.034 0.195 0.185 0.202 0.037

P-value 0.902 0.882 0.384 0.410 0.366 0.871

VAS8h r 0.129 0.061 0.143 0.312 0.193 0.192

P-value 0.567 0.788 0.527 0.157 0.390 0.392

VAS10h r 0.093 0.023 0.189 0.224 0.097 0.143

P-value 0.680 0.918 0.399 0.317 0.666 0.527

VAS12h r 0.083 0.100 0.115 0.174 0.126 0.130

P-value 0.714 0.659 0.609 0.438 0.577 0.565

VAS24h r 0.149 0.075 0.083 0.113 0.081 0.105

P-value 0.508 0.740 0.713 0.617 0.719 0.643

VAS7days r 0.126 0.113 0.049 0.088 0.090 0.087

P-value 0.576 0.616 0.828 0.698 0.690 0.701

Ibuprofen

Rescuedrugintake r 0.363 0.546a 0.046 0.293 0.568b 0.333

P-value 0.115 0.013 0.842 0.210 0.009 0.140

Mouthopeningdifficulty r 0.032 0.071 0.023 0.241 0.001 0.216

P-value 0.895 0.767 0.921 0.306 0.997 0.346

VAS0h r 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000

P-value 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000

VAS2h r 0.221 0.131 0.192 0.210 0.034 0.262

P-value 0.349 0.582 0.404 0.373 0.887 0.252

VAS4h r 0.221 0.141 0.203 0.028 0.148 0.060

P-value 0.349 0.553 0.378 0.906 0.534 0.795

VAS6h r 0.191 0.085 0.171 0.025 0.037 0.001

P-value 0.419 0.721 0.459 0.918 0.877 0.995

VAS8h r 0.077 0.012 0.162 0.056 0.005 0.007

P-value 0.748 0.961 0.483 0.815 0.984 0.975

VAS10h r 0.221 0.034 0.426 0.005 0.142 0.025

P-value 0.350 0.887 0.054 0.984 0.549 0.914

VAS12h r 0.143 0.195 0.050 0.223 0.059 0.231

P-value 0.546 0.411 0.829 0.344 0.804 0.313

VAS24h r 0.057 0.310 0.143 0.333 0.031 0.418

P-value 0.813 0.183 0.538 0.151 0.897 0.059

VAS7days r 0.446a 0.573b 0.100 0.501a 0.362 0.434a

P-value 0.049 0.008 0.666 0.025 0.117 0.049

Etoricoxib

Rescuedrugintake r 0.147 0.362 0.436a 0.027 0.085 0.021

P-value 0.502 0.090 0.037 0.901 0.701 0.925

Mouthopeningdifficulty r 0.129 0.387 0.477a 0.098 0.040 0.043

P-value 0.558 0.068 0.021 0.657 0.855 0.847

VAS0h r 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000

P-value 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000

VAS2h r 0.246 0.285 0.095 0.307 0.156 0.275

P-value 0.257 0.187 0.666 0.154 0.478 0.203

VAS4h r 0.026 0.117 0.399 0.308 0.090 0.320

P-value 0.905 0.595 0.059 0.152 0.684 0.136

VAS6h r 0.080 0.287 0.466a 0.156 0.068 0.133

P-value 0.717 0.184 0.025 0.476 0.759 0.546

VAS8h r 0.078 0.139 0.419a 0.215 0.102 0.309

P-value 0.722 0.526 0.047 0.325 0.644 0.152

VAS10h r 0.051 0.225 0.035 0.079 0.246 0.133

P-value 0.818 0.301 0.874 0.721 0.258 0.545

VAS12h r 0.167 0.189 0.113 0.350 0.105 0.248

VASat6h(r=0.466),andVASat8h (r=0.419).

Severalsignificantpositivecorrelations betweentheoedemadataandthelevelsof TNF-

a

andIL-1b

(attime00andattime 300)werefound:17intheplacebogroup and 0 (none) inthe ibuprofen and etor-icoxibgroups(TablesS1–S5).The num-ber of significant negative correlations between the oedema data and thelevels ofTNF-a

andIL-1b

(attime00andtime 300)was0intheplacebogroup,1inthe ibuprofen group,and3 intheetoricoxib group.Thenumberofsignificantnegative variations(D

)betweenthelevelsofTNF-a

andIL-1b

andtheoedemavalueswas5 in theplacebo group,2inthe ibuprofen group,and1intheetoricoxibgroup.Thenumber ofsignificantpositive variations (

D

)betweenthelevelsofTNF-a

and IL-1b

and theoedema values was 0in the placebo group,6intheibuprofengroup, and0intheetoricoxibgroup.Therewas asignificantpositive corre-lationbetweenthelevelofIL-1

b

attime 300andmaximummouthopeningat24h (r=0.503) and 72h (r=0.511) in the placebo group. The levels ofTNF-a

at time 300 showed a negative correlation withmaximummouthopeningatthe ini-tialtimepoint(r=0.440).Thelevelsof TNF-a

attime00showedapositive cor-relationwithmaximummouthopeningat 7 days postoperative (r=0.449). There was no significant correlation between the levels ofTNF-a

orlevels of IL-1b

andthemaximum mouthopeningvalues in the groups treated with ibuprofen or etoricoxib(Table2).

Discussion

Thisstudy assessed the effectiveness of theuseofpre-emptiveanalgesiausingtwo orallyadministeredNSAIDsthatare com-monlyprescribedforthecontrolof post-operative pain following oral surgery proceduresofmandibularthirdmolar re-moval. Third molar surgery is usually associatedwithmoderate(40%)tosevere pain (60%); thus, this pharmacological modelhasbecomethemostusedin clini-cal trials involving acute pain21,30,31. In addition,thissurgicalprocedureisoneof

Table1(Continued)

TNF-

a

IL-1b

Time00 Time300

D

Time00 Time300D

VAS24h r 0.258 0.165 0.331 0.292 0.046 0.292

P-value 0.235 0.451 0.123 0.176 0.833 0.177

VAS7days r 0.140 0.186 0.047 0.304 0.397 0.035

P-value 0.525 0.395 0.833 0.159 0.061 0.874

TNF-

a

,tumournecrosisfactoralpha;IL-1b

,interleukin1beta;VAS,visualanaloguescale.aP<0.05.

b

P<0.01,Spearmancorrelation.

Table2. Analysisofthecorrelationbetweencytokineprofilesandtheirvariations(finaldosageminusinitialdosage)andclinicaldataformouth

openingcapability.

TNF-

a

IL-1b

Time00 Time300

D

Time00 Time300D

Placebo

Initial r 0.186 0.440a 0.258 0.110 0.313 0.135

P-value 0.406 0.040 0.246 0.626 0.156 0.550

24h r 0.004 0.090 0.067 0.002 0.503a 0.087

P-value 0.985 0.691 0.767 0.994 0.017 0.700

72h r 0.307 0.364 0.048 0.303 0.511a 0.250

P-value 0.165 0.096 0.833 0.171 0.015 0.261

7days r 0.449a 0.161 0.403 0.328 0.145 0.311

P-value 0.036 0.473 0.063 0.136 0.521 0.158

Ibuprofen

Initial r 0.032 0.082 0.000 0.023 0.050 0.082

P-value 0.892 0.731 1.000 0.922 0.834 0.725

24h r 0.036 0.003 0.020 0.067 0.125 0.003

P-value 0.881 0.989 0.932 0.779 0.601 0.989

72h r 0.110 0.159 0.120 0.125 0.253 0.085

P-value 0.643 0.504 0.606 0.599 0.281 0.713

7days r 0.028 0.034 0.092 0.103 0.132 0.164

P-value 0.907 0.887 0.692 0.667 0.578 0.478

Etoricoxib

Initial r 0.201 0.386 0.331 0.015 0.001 0.011

P-value 0.357 0.069 0.122 0.944 0.995 0.961

24h r 0.041 0.261 0.139 0.197 0.165 0.067

P-value 0.852 0.230 0.527 0.368 0.452 0.761

72h r 0.258 0.309 0.146 0.134 0.123 0.111

P-value 0.235 0.151 0.506 0.543 0.577 0.616

7days r 0.193 0.004 0.277 0.211 0.010 0.146

P-value 0.379 0.985 0.200 0.333 0.963 0.506

TNF-

a

,tumournecrosisfactoralpha;IL-1b

,interleukin1beta.a

the best clinical models to study pain becauseitpresentspredictable inflamma-tory features, andthe populationstudied

can be considered more homogeneous

becauseitisusuallycomposedofyoung, healthyindividualswhofully understand alloftheinformation provided.The sur-gicaltechniqueemployedisstandardized amongpatients,thesurgicaltime general-ly doesnot exceed40min,and the

pro-cedure is commonly performed under

local anaesthesia. Such aspects permit the administration of study medications withaminimalriskofpostoperative com-plications30. The present study supports thesepremises,allowingamoreaccurate evaluationofthemedicationsstudied.

Pharmacologically,NSAIDsactby re-ducingperipheralandcentralnociception. The NSAID etoricoxib is considered a selective COX-2 inhibitor. Boonriong et al. showed that when etoricoxib was usedpre-emptivelyinpatientsundergoing arthroscopic shoulder surgery, it signifi-cantly reduced postoperative pain32. Others have also demonstrated that the pre-emptiveuseofetoricoxib120mg pro-videsadequatepaincontrolfollowing oth-ertypesofsurgicalprocedure32–34.Costa et al.evaluated theclinicaleffectiveness ofetoricoxib120mgusingasimilar meth-odology and the same type of surgical procedure as employed in the present study7.Thecomparisonofthepre-emptive use ofthis selectiveCOX-2 inhibitor to placebo allowedtheauthorstoshowthe effectiveness ofetoricoxib120mginthe controlofpostoperativepain.Theresults obtainedinthepresentstudysupportthis findingandothersreportedintheliterature by confirmingtheeffectiveness of etori-coxibwhenusedaspre-emptiveanalgesia in third molar extraction procedures. In addition, the comparison of the experi-mentalgroupstotheplacebogroupinthis studyshowedthatthehigherthe selectivi-tyofthemedication,thebetterthe

anal-gesia, oedema, and trismus observed

duringthepostoperativeperiod.

Inthisstudy,patientstreatedwith

etor-icoxib 120mg showed the greatest

improvements in pain intensity, extent ofmouthopening,andoedemawhen com-paredtothosetreatedwithibuprofen400

mg. In addition, these two groups

expressedbetteroutcomesthanthe place-bogroup.Inagreementwiththeseresults, tworecentreviewsthatmeasuredthe post-operative effectiveness of etoricoxib 120mgshowed that72% ofparticipants from five different studies experienced significant painrelief at 4–6h after sur-gery35,36. Based on the results found in previousclinicaltrials,thelevelsof

pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-

a

and IL-1b

were quantified in this study as a means to measure the clinical outcome. Interestingly,theextentofmouthopening wasfoundnottocorrelatewiththelevels ofcytokinesamongpatientstreatedwith NSAIDs, while the higher the levels of these cytokines,the higher wasthe con-sumptionofrescuemedicationandlevel of postoperativepain, and thelowerthe painscores,thelowerwerethe concentra-tionsofcytokines,andasaresulttheuse of rescue medication was less reported amongtheseindividualsinthe postopera-tiveperiod.Apreviousstudyscreenedpericoronal tissuefragmentsobtainedfromthirdmolar surgicalsitesfor thepresence of inflam-matorymediatorsandidentifiedadistinct productionofCOX-1productsand pros-taglandinE2(PGE2),mediatedbyCOX-1 and COX-29. Another study evaluating celecoxib, a selective COX-2 inhibitor, was unable to detect any alterations in the levels of thromboxane B2 following thirdmolarsurgery.However,theirresults showed suppression of PGE2 levels be-tween 120min and 240min after third molar removal37. According to a study byKhanetal.,onecanexpectagradual increase in COX-2 at 30min after the completion of third molar extractions, suggesting that an increase inthe levels ofprostanoidscancontributetothe devel-opment of postoperative pain and the acute inflammatory process38. Thus, the assessmentofthese inflammatory media-tors asthey correlatewith postoperative pain in patients undergoing pre-emptive analgesiawithNSAIDsmayallowabetter

understanding of the mechanisms

in-volvedintheseinflammatoryprocesses.

COX-2 is an enzyme commonly

expressed in tissues once inflammation occursandisalsoconstitutivelyexpressed in some tissues. In vitro studies have shown apositivefeedbackloopbetween the expression of COX-2 and increased levelsofproinflammatorycytokinessuch as TNF-

a

and IL-1b

in various cell types39.Infibroblasts(themaincelltype presentintissuesamplesusedtomeasure cytokines), the expression of COX-2 is directly proportional to the levels ofTNF-

a

and IL-1b

, and COX-2 alsoinducesPGE2production.Thus,agreater inhibitionoftheCOX-2pathwaythrough the pre-emptive administration of etori-coxib should result in a reduction in TNF-

a

andIL-1b

40.In this study, the use of a selective COX-2 inhibitor (etoricoxib) resulted in areductioninTNF-

a

withaninsignificant changenotedinthelevelsofIL-1b

fromtime00totime300postoperative.Sincean increase in COX-2 raises the levels of TNF-

a

,whichinturninducesthe forma-tionofIL-1b

,anearlydecreaseinTNF-a

generatedbyCOX-2inhibitionshould precede detectable changes in IL-1b

, explaining the present findings. TNF-a

isalsodirectlyrelatedtothehyperalgesia generatedbyinflammatorystates,actingby two mechanisms: (1) induction

of COX-2 and subsequent synthesis of eicosanoids byreleaseofIL-1

b

,(2) in-duction ofsympathomimeticaminepro-duction via IL-8. Depending on the

intensity and nature of the stimuli, the release of TNF-

a

is preceded by theformationofbradykinin41.The pres-ent study observed that the greater the reduction in the levels of TNF-a

from time00totime300,thelessdifficultwas mouth openingand the lower were the consumption of rescue medication and pain scoresat6hand8h.ThelevelsofTNF-

a

and IL-1b

were reducedinthegrouptreatedwithibupro-fen. Ibuprofen is an NSAID with low

COX-2 selectivity, or a lack thereof. Hence, the relative increase in COX-1 selectivity expressed by ibuprofen may be responsible inpartfor the significant decreaseinthelevels ofthesetwo cyto-kines.COX-1isaconstitutiveenzymeand as such does not need to be induced; hence,thepresenceofacute inflammato-ry processesdoesnot modify the levels of COX-1 gene expression40. The pre-emptive administration of ibuprofen (a drug withpartialCOX-2 selectivity)led toareductioninthelevelsofTNF-

a

and IL-1b

from time 00 to time 300, a rela-tively short time for such an intensereduction in COX-2 gene expression,

butlongenoughtoinhibitthe inflamma-tory process generated by this constitu-tiveenzyme.However,thesestudieswere performed withlungfibroblastsand fur-ther studiesare neededtoconfirmthese hypotheses.

Inconclusion,tissueconcentrationsof TNF-

a

andIL-1b

andthefindingsofpain and oedema in mandibular third molar surgeries were inversely associated with the level of COX-2 selectivity of the NSAID used pre-emptively. In addition, patientssubjectedtopre-emptive analge-sia showeda significantreduction inthe clinical parameters ofpain, trismus, andoedema when compared to the placebo

group.

Funding

fromtheConselhoNacionalde Desenvol-vimento Cientı´ficoeTecnolo´gico(MTC/ CNPqNo.14/2013).

Competinginterests

None.

Ethicalapproval

This study was approved by the Ethics CommitteeofWalterCantı´dioUniversity Hospital(No.44058715.4.0000.5045)and was performed in accordance with the Helsinkistatements.

Patientconsent

Written patient consent was obtained to publishtheclinicalphotograph.

AppendixA. Supplementarydata

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. ijom.2017.05.007.

References

1. MartinMV,KanatasAN,HardyP.Antibiotic

prophylaxisandthird-molarsurgery.BrDent

J2005;198:327–30.

2. Benediktsdottir IS,Wenzel A,PetersenJK,

Hintze H.Mandibularthirdmolarremoval:

risk indicatorsforextended operationtime,

postoperative pain,and complications.Oral

Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol

Endod2004;97:438–46.

3. MollerPL,Sindet-PedersenS,PettersenCT,

Juhl GI, Dillenschneider A, Skoglund LA.

Onsetofacetaminophenanalgesia:

compari-sonoforalintravenousroutesafterthirdmolar

surgery.BrJAnaesth2005;94:642–8.

4. Forbes JA. Oral surgery, advances in pain

researchandtherapy:thedesignofanalgesic

clinicaltrials.In:MaxMB,PortenoyR,Laska

EM,editors.Advancesinpainresearchand

therapy: the design of analgesic clinical

trials. New York: Raven Press; 1991 . p.

347–74.

5. Saito K, Kaneko A, Machii K, Ohta H,

Ohkura M, Suzuki M. Efficacy and safety

of additional 200-mg dose of celecoxib in

adultpatientswithpostoperativepain

follow-ingextractionofimpactedthirdmandibular

molar: a multicenter, randomized,

double-blind,placebo-controlled, phaseII studyin

Japan.ClinTher2012;34:314–28.

6. AverbuchM,KatzperM.Severityofbaseline

painanddegreeofanalgesiainthethirdmolar

post-extraction dental pain model. Anesth

Analg2003;97:163–7.

7. Costa FW,SoaresEC,Esses DF,SilvaPG,

Bezerra TP, Scarparo HC, Ribeiro TR,

Fonteles CSR. A split-mouth, randomized,

triple-blind,placebo-controlledstudyto

ana-lyzethepre-emptiveeffectofetoricoxib120

mgoninflammatoryeventsfollowingremoval

ofuneruptedmandibularthirdmolars.IntJ

OralMaxillofacSurg2015;44:1166–74.

8. Van Gool AV, Ten Bosch JJ, Boering G.

Clinical consequences andcomplaints after

removalofthemandibularthirdmolar.IntJ

OralSurg1977;6:29–37.

9. KhanAA,IadarolaM,YangHY,DionneRA.

Expression of COX-1 and -2 in a clinical

modelof acuteinflammation.J Pain2007;

8:349–54.

10. Kyrkanides K, FiorentinoPM, Miller JH,

GanY,LaiY,ShaftelSS,PuzasJE,Piancino

MG,O’BanionMK,TallentsRH.

Ameliora-tionofpainandhistopathologicjoint

abnor-malitiesintheCol1-IL-1XATmousemodel

of arthritis by intraarticular induction of

m-opioidreceptorintothe

temporomandib-ularjoint.ArthritRheum2007;56:2038–48.

11. VernalR,Vela´squezE,GamonalJ,

Garcia-Sanz JA,Silva A,SanzM.Expression of

proinflammatory cytokinesinosteoarthritis

ofthetemporomandibularjoint.ArchOral

Biol2008;53:910–5.

12. Chicre-Alcaˆntara TC, Torres-Cha´vez KE,

Fischer L, Clemente-Napimoga JT, Melo

V, Parada CA,Tambeli RH. Local kappa

opioidreceptoractivationdecreases

tempo-romandibularjointinflammation.

Inflamma-tion2012;35:371–6.

13. QuinteiroMS,NapimogaMH,MesquitaKP,

Clemente-NapimogaJT. Theindirect

anti-nociceptive mechanism of 15d-PGJ(2) on

rheumatoidarthritis-inducedTMJ

inflamma-tory pain in rats. Eur J Pain 2012;16:

1106–15.

14. Watkins LR, Wiertelak EP, Goehler LE,

SmithKP,MartinD,MaierSF.

Characteri-zation of cytokine-induced hyperalgesia.

BrainRes1994;654:15–26.

15. Alstergren P, Ernberg M, Kvarnstro¨m M,

Kopp S. Interleukin 1b in synovial fluid

from thearthritictemporomandibular joint

anditsrelationtopain,mobility,andanterior

openbite.J OralMaxillofacSurg1998;6:

1059–65.

16. Alstergren P,BenaventeC,Kopp S.

Inter-leukin1b,Interleukin1receptorantagonist,

and Interleukin 1 soluble receptor II in

temporomandibularjointsynovialfluidfrom

patientswithchronicpolyarthritides.JOral

MaxillofacSurg2003;61:1171–8.

17. CunhaFQ,PooleS,LorenzettiBB,Ferreira

SH. The pivotal role of tumour necrosis

factoralphainthedevelopmentof

inflam-matoryhyperalgesia.BrJPharmacol1992;

107:660–4.

18. AlstergrenP.Cytokinesin

temporomandib-ularjointarthritis.OralDis2000;6:331–4.

19. EmshoffR,PufferP,RudischA,GabnerR.

Temporomandibularjointpain:relationship

tointernalderangementtype,osteoarthrosis,

andsynovial fluidmediatorleveloftumor

necrosisfactor-alpha.OralSurgOralMed

Oral Pathol OralRadiol Endod 2000;90:

442–9.

20.OguraN,TobeM,SakamakiH,NaguraH,

AbikoY,KondohT.Tumornecrosis

factor-alphaincreaseschemokinegeneexpression

andproductioninsynovialfibroblastsfrom

human temporomandibular joint. J Oral

PatholMed2005;34:357–63.

21.KeJ,LongX,LiuY,ZhangYF,LiJ,FangW,

Meng QG. Role of NF-kappaB in

TNF-alpha-inducedCOX-2expressioninsynovial

fibroblasts from human TMJ.J Dent Res

2007;86:363–7.

22.KaczmarzykT,WichlinskiJ,Stypulkowska

J,ZaleskaM,WoronJ.Preemptiveeffectof

ketoprofenonpostoperativepainfollowing

thirdmolarsurgery.Aprospective,

random-ized,double-blindedclinicaltrial.IntJOral

MaxillofacSurg2010;39:647–52.

23.Isiordia-Espinoza MA, Pozos-Guille´n AJ,

Martinez-Rider R, Herrera-Abarca JE,

Pe´rez-UrizarJ.Preemptiveanalgesic

effec-tivenessoforalketorolacpluslocaltramadol

afterimpactedmandibularthirdmolar

sur-gery.MedOralPatolOralCirBucal2011;

16:776–80.

24.LustenbergerFD,Gra¨tzKW,MutzbauerTS.

Efficacy of ibuprofen versus lornoxicam

after third molar surgery: a randomized,

double-blind, crossover pilot study. Oral

MaxillofacSurg2011;15:57–62.

25.Sotto-MaiorBS,SennaPM,deSouza

Picor-elliAssisNM.Corticosteroidsor

cyclooxy-genase2-selectiveinhibitor medicationfor

themanagementofpainandswellingafter

third-molarsurgery.JCraniofacSurg2011;

22:758–62.

26.Al-Sukhun J, Al-Sukhun S, Penttila¨ H,

AshammakhiN,Al-Sukhun R.Preemptive

analgesiceffectoflowdosesofcelecoxibis

superiortolowdosesoftraditional

nonste-roidalanti-inflammatorydrugs.JCraniofac

Surg2012;23:526–9.

27.MoherD,HopewellS,SchulzKF,Montori

V,GøtzschePC,DevereauxPJ,ElbourneD,

Egger M,AltmanDG. CONSORT,

CON-SORT 2010 explanation and elaboration:

updated guidelines for reporting parallel

group randomisedtrials. Int JSurg2012;

10:28–55.

28.PellGJ,GregoryBT.Impactedmandibular

third molars: classification and modified

techniquesforremoval.DentDigest1933;

39:330–8.

29.WinterGB.Principlesofexodontiaapplied

to the impacted mandibular third molar.

SaintLouis:AmericanBooks;1926.

30.LustenbergerFD,Gra¨tzKW,MutzbauerTS.

Efficacy of ibuprofen versus lornoxicam

after third molar surgery: a randomized,

double-blind, crossover pilot study. Oral

MaxillofacSurg2011;15:57–62.

31.SavageMG,HenryMA.Preoperative

oftheliterature.OralSurgOralMedOral

PatholOralRadiolEndod2004;98:146–52.

32. BoonriongT,TangtrakulwanichB,Glabglay

P,NimmaanratS.Comparingetoricoxiband

celecoxibforpreemptiveanalgesiaforacute

postoperative pain in patients undergoing

arthroscopic anterior cruciateligament

re-construction:arandomizedcontrolledtrial.

BMCMusculoskeletDisord2010;11:246.

33. LiuW,LooCC,ChiuJW,TanHM,RenHZ,

LimY.Analgesicefficacyofpre-operative

etoricoxibforterminationofpregnancyinan

ambulatorycenter.SingaporeMedJ2005;246:

397–400.

34. PuuraA,PuolakkaP,RorariusM,Salmelin

R, Lindgren L. Etoricoxib pre-medication

for post-operative pain after laparoscopic

cholecystectomy. ActaAnaesthesiol Scand

2006;50:688–93.

35. ClarkeR,DerryS,MooreRA.Singledose

oraletoricoxibforacutepostoperativepain

in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2012;(4):CD004309.

36. ClarkeR,DerryS,MooreRA.Singledose

oral etoricoxib for acute postoperative

pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev2014;(5):CD004309.

37. Khan AA,Brahim JS, RowanJS,Dionne

RA.Invivoselectivityofaselective

cyclo-oxygenase 2 inhibitor in the oral surgery

model.ClinPharmacolTher2002;72:44–9.

38. KhanAA,IadarolaM,YangHY,DionneRA.

Expression ofCOX-1and-2 ina clinical

model of acute inflammation. J Pain

2007;8:349–54.

39. CroffordLJ.COX-1andCOX-2tissue

ex-pression: implications and predictions. J

RheumatolSuppl1997;49:15–9.

40. DiazA,ChepenikKP,Korn JH,Reginato

AM,JimenezSA.Differentialregulationof

cyclooxygenases1and2byinterleukin-1b,

tumornecrosisfactor-alpha,and

transform-inggrowthfactor-beta1inhumanlung

fibro-blasts.ExpCellRes1998;241:222–9.

41. RibeiroRA,ValeML,FerreiraSH,Cunha

FQ.Analgesiceffectofthalidomideon

in-flammatory pain. Eur J Pharmacol 2000;

391:97–103.

Address:

Fa´bioWildsonGurgelCosta FederalUniversityofCeara´ DepartmentofDentalClinic SchoolofDentistry

RuaAlexandreBarau´na 949

RodolfoTeofilo 60430-160Fortaleza Ceara´

Brazil