ABSTRACT: The objective of this study was to examine the association between individual satisfaction with social and physical surroundings and the habit of smoking cigarettes. Data from the Health Survey of Adults from the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, were used. Based on a probability sample, participants (n = 12,299) were selected among residents aged 20 years old or more. The response variable was the smoking habit and the explanatory variable of interest was the neighborhood perception. Potential confounding variables included demographic characteristics, health behaviors and other indicators of socioeconomic position. The prevalence of current smokers, former smokers and never smokers were 20.8, 14.1 and 65.1%, respectively; 74.4 and 25.5% of the participants were categorized as being more satisied and less satisied with the neighborhood, respectively. Compared to those who never smoked, former smokers (adjusted odds ratio = 1.40, 95% conidence interval 1.20 – 1.62) and current smokers (adjusted odds ratio = 1.17, 95% conidence interval 1.03 – 1.34) were less satisied with the neighborhood compared to those who never smoked. The results of this study indicate there is an independent association between the smoking habit and a less satisfying neighborhood perception in the metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte, which does not depend on individual characteristics, traditionally reported as being associated with smoking.

Keywords: Smoking. Housing. Residence characteristics. Health survey. Perception. Social perception.

Satisfaction with physical and social

surroundings and the habit of smoking

cigarettes in the metropolitan area of Belo

Horizonte, Brazil

A satisfação com o entorno físico e social e o hábito de fumar cigarros na

região metropolitana de Belo Horizonte

Ricardo Alexandre de SouzaI, Cláudia Di Lorenzo OliveiraI, Maria Fernanda Lima-CostaII, Fernando Augusto ProiettiIII

ORIGINAL ARTICLE / ARTIGO ORIGINAL

IUniversidade Federal de São João Del-Rei/Campus CCO – Divinópolis (MG), Brazil. IIResearch Center René Rachou, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz – Belo Horizonte (MG), Brazil. IIISchool of Health and Human Ecology – Vespasiano (MG), Brazil.

Corresponding author: Ricardo Alexandre de Souza. Universidade Federal de São João Del-Rei, Campus Centro-Oeste. Avenida Sebastião Gonçalves Coelho, 400, Xanadu, CEP: 35501-296, Divinópolis, MG, Brasil. E-mail: ricardosouza@ufsj.edu.br

INTRODUCTION

The smoking habit is a risk factor for ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, lower respiratory tract infections, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, respiratory system cancer and tuberculosis, among others1. Nowadays, tobacco is the most used

drug in the world, responsible for approximately 5.4 million deaths a year, out of which 50% occur in mid and low-income countries2. The habit of smoking cigarettes can be

associated with 25% of cerebrovascular diseases, 30% of deaths caused by malignant neoplasms, 45% of heart diseases and 85% of respiratory diseases3. Additionally, passive

smoking is the 3rd major preventable cause of death in the world, after the habit of

smoking cigarettes and excessive alcohol consumption4. In Brazil, it is estimated that

about 200 thousand deaths a year are associated with the smoking habit5.

In 2008, approximately 3.3 billion individuals, that is, more than half of the world population, lived in cities. In 2030, it is estimated that around 5 billion people will live in urban areas. Therefore, globally, the future population growth will take place in the cities, which are already densely populated6. In Brazil, the proportion of people living

in urban areas increased from 31.3%, in 1940, to 84.3%, in 20117; consequently, urban

centers will have most of the smokers in the country.

RESUMO: O objetivo do trabalho foi examinar a associação entre a satisfação com o entorno físico e social da vizinhança e o hábito de fumar cigarros. Foram utilizados dados do Inquérito de Saúde dos Adultos da Região Metropolitana de Belo Horizonte. Os participantes do estudo (n = 12.299) foram selecionados por meio de amostra probabilística entre os residentes com 20 anos ou mais de idade. A variável resposta foi o hábito de fumar e a variável explicativa de interesse foi a percepção da vizinhança. Potenciais variáveis de confusão incluíram características demográicas, outros comportamentos em saúde e indicadores de posição socioeconômica. As prevalências de fumantes atuais, ex-fumantes e dos que nunca fumaram foram 20,8; 14,1 e 65,1%, respectivamente; 74,4% e 25,5% dos participantes foram categorizados como mais satisfeitos e menos satisfeitos com a vizinhança, respectivamente. Em comparação aos que jamais fumaram, os ex-fumantes (odds ratio ajustado = 1,40; intervalo de coniança de 95% 1,20 – 1,62) e os fumantes atuais (odds ratio ajustado = 1,17; intervalo de coniança de 95% 1,03 – 1,34) eram menos satisfeitos com a vizinhança em comparação aos que nunca fumaram. Os resultados deste trabalho mostraram que existe associação independente entre o hábito de fumar e pior percepção da vizinhança na região metropolitana de Belo Horizonte, que independe de características individuais, tradicionalmente reportadas como associadas ao hábito de fumar.

Recent studies have shown that the physical and social surroundings (PSS) of the household are associated with the smoking habit8,9. Some of these studies suggest that

such an association can be independent from individual socioeconomic status10-13. In Brazil,

the influence of PSS of the neighborhood and the habit of smoking cigarettes has been little analyzed, and, to our knowledge, there are no population-based epidemiological studies in major urban centers on the subject.

This study aims at examining and quantifying the association between perception of the neighborhood and smoking habit among adults living in the metropolitan rea of Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais.

METHODS

DATA SOURCE AND POPULATION

The data source for this study was the Health Survey from the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte (RMBH), conducted from May to July, 2003. The survey sample was designed to produce estimates of the non-institutionalized population aged 10 years old or more, living in the 20 cities that composed the RMBH. This is a two-stage probability cluster sample. The census sectors from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) were used as the primary selection unit, and the sampling unit was the household. The estimated loss in the sampling calculation accounted for 20%. All of the people living in the household aged 10 years old or more were eligible for a face to face interview. Out of the 7,500 sample households, 5,922 (79%) participated in the survey. More details are demonstrated in another publication14. For this study, all of the participants in the health survey aged 20 years

old or more were selected.

RESPONSE VARIABLE

EXPLANATORY VARIABLES

The main explanatory variable was the perception of the neighborhood, categorized as satisfactory and unsatisfactory. These categories were built based on the responses (yes/no) to the following questions: (1) “Do you feel comfortable in the neighborhood where you live, that is, do you feel at home?”, (2) “Are you satisied about how the block where you live is taken care of ?”; (3) “Is your neighborhood a good place to live?”; (4) “Are you proud to tell others about the place where you live?”; (5) “Do your neighbors help each other?”; (6)“Do children and teenagers in your neighborhood treat adults with respect?”; and (7) “Is your neighborhood a good place for children to play and to raise adolescents?”. More than three positive responses (yes) were deined as a satisfactory perception of the neighborhood. Three or fewer positive responses were deined as a less pleasant perception of the neighborhood. This variable was built by the authors for being the mean point of the seven possible responses, after factorial analysis.

Other explanatory variables constituted four domains: (1) socioeconomic and demographic characteristics (age, sex, marital status, time of household in RMBH, schooling years, iliation to a private health insurance plan and current job); (2) health behaviors (excessive alcohol consumption, physical activities at leisure times and daily intake of fruits, vegetables or greens in the past 30 days); (3) history of medical diagnosis for diseases and chronic conditions. Excessive alcohol consumption was deined by the intake of 5 or more doses in a single occasion in the past 30 days16. Physical activities during leisure time were deined by

the weekly frequency, in the past 90 days, of activities of any intensity for 20 to 30 minutes. The consumption of greens, fruits and vegetables was deined by the daily intake, regardless of the amount, in the past 30 days. The condition of having one or more chronic diseases was deined by the question “Has any doctor ever said you have”, considering the following diseases or chronic conditions: arthritis, cancer, hypertension, asthma/bronchitis, diabetes, angina, infarction, another heart disease, stroke, chronic kidney disease and depression.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The non-adjusted data analysis was based on the χ2 test for comparisons between

the software Stata 10.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas). The survey (svy) procedure was used for population surveys with complex samples, which considers the design effect17, the weight of the individuals in the sample and the household cluster.

The Health Survey in the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte was approved by the Ethics Committee from the Research Institute René Rachou, in Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais (Report n. 011, from 20/12/2001).

RESULTS

Out of the 13,636 participants of the Heath Survey in the RMBH aged 20 years old or more, 12,129 (88.9%) had complete information for all of the study variables and were included in this analysis. Participants and non-participants were similar (p < 0.05) with regard to sex, age, schooling years, smoking habit and perception of the neighborhood. Concerning the habit of smoking cigarettes, 65.1% of the participants had never smoked, 14.1% were former smokers and 20.8% were current smokers. Satisfaction about the neighborhood was prevalent in the studied population (74.5%).

Among participants, mean age was of 40.5 years old, and the age group between 20 and 29 years old was prevalent (29.9%), as well as the female gender (54.3%) with lower schooling (44.4% had not completed elementary school or were illiterate); as observed in Table 1.

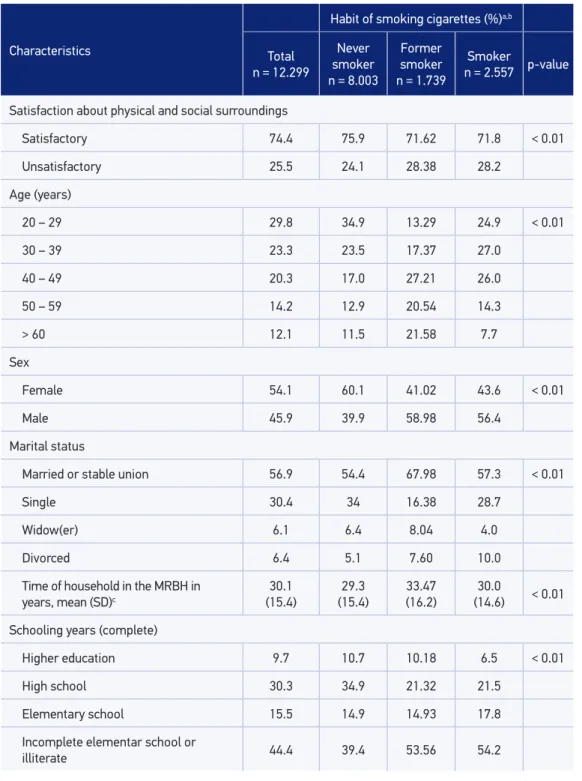

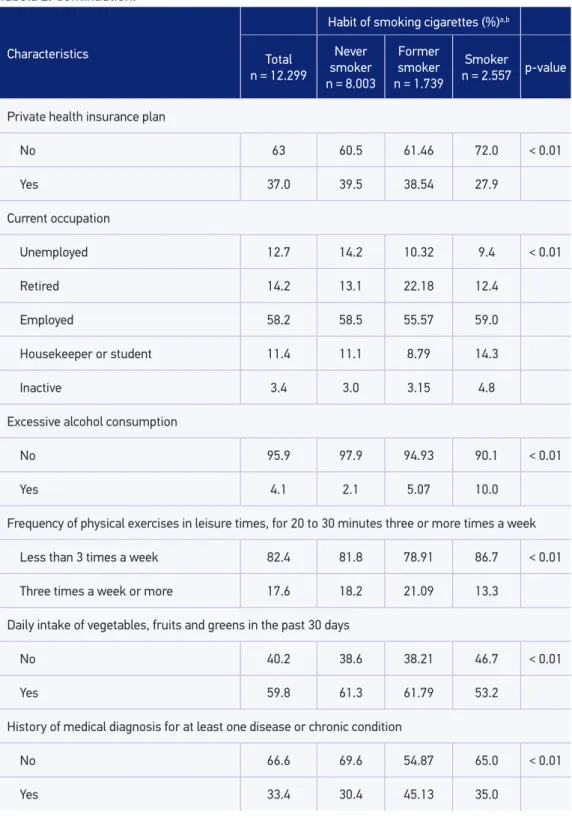

Table 2 shows the results of the univariate analysis of the association between perception of the neighborhood and socioeconomic and demographic characteristics with the smoking habit. The perception of the neighborhood, age, sex, marital status, time of household in the RMBH, schooling years, filiation to a private health insurance plan and current job presented statistically significant associations with the smoking habit. The excessive alcohol consumption, physical activities during leisure time, the daily intake of vegetables, fruits and greens and the condition of having at least one chronic disease presented statistically significant associations with the smoking habit.

The final results of the multivariate analysis (Table 3) show that the perception of the neighborhood, age group and sex presented statistically significant associations with the smoking habit. In comparison to those who never smoked, former smokers were less satisfied about their neighborhood, mostly older men. In comparison to those who never smoked, current smokers were less satisfied about their neighborhood, mostly men aged between 30 and 59 years old.

DISCUSSION

persisted even after adjustments by socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, health-related behaviors and self-reported health conditions.

In general, these results are in accordance with studies conducted in cities from high-income countries, like Amsterdam, in the Netherlands, and Minneapolis, in the United States18,19. Some studies are conclusive with regard to the importance of the

neighborhood for the habit of smoking cigarettes. An analysis conducted in London, England, used a multilevel model and reported that living in more vulnerable areas, in relation to the characteristics of the physical and social surroundings, would be related to the higher frequency of cigarette use and the habit of smoking cigarettes20. Besides,

in Manchester, England, living in more vulnerable places with regard to physical and social surroundings was a predictive factor for the number of cigarettes smoked by the participants21. More recently, a study conducted in several cities of France showed that

the risk of being a smoker was comparatively higher in areas with lower income, even after individual factors were controlled (education, income, occupation)22. In Austin, in

the United States, a study involving the afro-descendants showed that physical and social surroundings were more strongly associated with the habit of smoking cigarettes than

Table 1. Distribution of frequency according to the selected variables for 12,299 participants. Health Survey of Adults, metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. 2003.

Characteristics %

Smoker 20.8

Positive perception of the neighborhood 73.8

Aged between 20 and 29 years old 29.6

Female 54.1

Married or stable union 56.5

At least higher education 8.0

Private health insurance plan 34.9

Unemployed 12.5

Consumption of more than ive doses of alcohol in the past week 4.4

Frequency of less than three times a week for physical activities lasting

from 20 to 30 minutes during leisure time, in the past 90 days 82.7

Chronic diseases 34.2

Daily intake of fruits, vegetables and greens in the past 30 days 58.8

Time of household in the metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte, years

Continue...

Table 2. Univariate analysis of the association between satisfaction concerning physical and social surroundings, sociodemographic characteristics and the habit of smoking cigarettes. Health Survey of the metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. 2003.

Characteristics

Habit of smoking cigarettes (%)a,b

Total

n = 12.299

Never smoker

n = 8.003

Former smoker

n = 1.739

Smoker

n = 2.557 p-value

Satisfaction about physical and social surroundings

Satisfactory 74.4 75.9 71.62 71.8 < 0.01

Unsatisfactory 25.5 24.1 28.38 28.2

Age (years)

20 – 29 29.8 34.9 13.29 24.9 < 0.01

30 – 39 23.3 23.5 17.37 27.0

40 – 49 20.3 17.0 27.21 26.0

50 – 59 14.2 12.9 20.54 14.3

> 60 12.1 11.5 21.58 7.7

Sex

Female 54.1 60.1 41.02 43.6 < 0.01

Male 45.9 39.9 58.98 56.4

Marital status

Married or stable union 56.9 54.4 67.98 57.3 < 0.01

Single 30.4 34 16.38 28.7

Widow(er) 6.1 6.4 8.04 4.0

Divorced 6.4 5.1 7.60 10.0

Time of household in the MRBH in years, mean (SD)c

30.1 (15.4)

29.3 (15.4)

33.47

(16.2) (14.6)30.0 < 0.01

Schooling years (complete)

Higher education 9.7 10.7 10.18 6.5 < 0.01

High school 30.3 34.9 21.32 21.5

Elementary school 15.5 14.9 14.93 17.8

Incomplete elementar school or

Tabela 2. Continuation.

Characteristics

Habit of smoking cigarettes (%)a,b

Total

n = 12.299

Never smoker

n = 8.003

Former smoker

n = 1.739

Smoker

n = 2.557 p-value

Private health insurance plan

No 63 60.5 61.46 72.0 < 0.01

Yes 37.0 39.5 38.54 27.9

Current occupation

Unemployed 12.7 14.2 10.32 9.4 < 0.01

Retired 14.2 13.1 22.18 12.4

Employed 58.2 58.5 55.57 59.0

Housekeeper or student 11.4 11.1 8.79 14.3

Inactive 3.4 3.0 3.15 4.8

Excessive alcohol consumption

No 95.9 97.9 94.93 90.1 < 0.01

Yes 4.1 2.1 5.07 10.0

Frequency of physical exercises in leisure times, for 20 to 30 minutes three or more times a week

Less than 3 times a week 82.4 81.8 78.91 86.7 < 0.01

Three times a week or more 17.6 18.2 21.09 13.3

Daily intake of vegetables, fruits and greens in the past 30 days

No 40.2 38.6 38.21 46.7 < 0.01

Yes 59.8 61.3 61.79 53.2

History of medical diagnosis for at least one disease or chronic condition

No 66.6 69.6 54.87 65.0 < 0.01

Yes 33.4 30.4 45.13 35.0

ap value: Pearson’s χ2 test for diferences between frequencies and analysis of variance for diferences between means;

the individual characteristics of the people living there23. A multilevel study conducted

in cities from the count of Norfolk, in England, demonstrated that the higher the level of social vulnerability (worst socioeconomic status of the individuals and lower schooling), the higher the chances of these individuals being smokers24. In another

study, men living in Minneapolis, United States, who assessed their neighborhood as having more social cohesion, had less chances of being smokers19. A multilevel

study conducted in Adelaide, Australia, showed that aggregated features (indicator of relative socioeconomic disadvantage, obesity and quality of life) to the household area contribute with smoking, regardless of individual factors9. A recent study conducted in

the Netherlands showed that people who live in more vulnerable areas presented less chances of abandoning the use of tobacco20.

There are some limitations in this study. In sectional studies, it is not possible to establish temporal relationships or to ensure the asymmetry between exposure and

Table 3. Multinomial logistic regression for the habit of smoking cigarettes according to the satis -faction concerning physical and social surroundings, age and sex, for 12,299 participants. Health Survey of Adults, metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. 2003

Characteristics

Habit of smoking cigarettes

(non-adjusted value)

Habit of smoking cigarettes (OR; 95%CI)

Smoker Former

smoker Smoker

Former smoker

Satisfaction about physical and social surroundings

Satisfactory 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

Less satisfactory 1.2 (1.1 – 1.4) 1.2 (1.1 – 1.4) 1.4 (1.2 – 1.6) 1.2 (1.0 – 1.3)

Age (years)

20 – 29 1.0 1.00

30 – 39 1.7 (1.3 – 2.1) 1.5 (1.3 – 1.8)

40 – 49 3.6 (2.8 – 4.6) 1.9 (1.5 – 2.3)

50 – 59 3.5 (2.7 – 4.6) 1.3 (1.1 – 1.6)

> 60 4.4 (3.2 – 6.1) 0.8 (0.6 – 1.1)

Sex

Female 1.0 1.00

Male 2.5 (2.2 – 2.9) 1.9 (1.6 – 2.1)

OR: odds ratio; 95%CI: 95% conidence interval adjusted for all of the variables listed in the table and type of

respondent, marital status, sex, age, time of household, schooling years, health plan, occupation, alcohol

event of interest. With regard to the response variable, our study did not measure the duration of cigarette use. Therefore, among smokers, some individuals have used cigarettes for very different periods of time. Yet, potential participants of this study, who would be the “inveterate smokers”, may not have participated in the survey for having died or for being very ill and hospitalized. Also, a possible reason for the higher magnitude of the association for former smokers found in our study can be related to its cross-sectional design; therefore, it is possible that the group of former smokers is composed of individuals who recently abandoned the smoking habit, and others who did so a long time ago.

On the other hand, there are some positive aspects in this study, such as the sample size, the geographic scope of the third largest metropolitan region in the country and, in a recent literature review, the absence of a similar study in Brazil.

Our results suggest that programs against smoking should consider the importance of the physical and social surroundings of the neighborhood, which is an often neglected health determinant. Interventions on the physical and social surroundings of the neighborhood, which are not traditionally associated with the health field, may have a positive impact on the habit of smoking cigarettes25,26.

CONCLUSION

The results can be associated with the unfavorable conditions of the most vulnerable physical and social surroundings of the neighborhood. Further studies should take place in Brazil to investigate other factors associated with the use of cigarettes, other than individual ones5, in order to better understand this and other public health problems.

Besides, public programs against smoking should consider the importance of the physical and social surroundings (PSS) of the neighborhood, which is an often neglected health determinant. Therefore, interventions on the physical and social surroundings of the neighborhood, which are not traditionally associated with the health field, may have a positive impact on behaviors and lifestyles, such as the habit of smoking cigarettes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To Victor Camargos, for helping to elaborate the data base.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Oice on Smoking and Health. The health consequences smoking – 50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Government Printing Oice; 2014.

2. World Health Organization (WHO). Tobacco Control: Country Proiles. Genebra: WHO; 2003.

3. BRASIL. Instituto Nacional do Ĉncer. Programa Nacional de Controle do Tabagismo [Internet]. Disponível em: http://www1.inca.gov.br/tabagismo/ frameset.asp?item=programa&link=introducao.htm. (Acessado em 12 de fevereiro de 2014)

4. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: why is it important? Genebra; 2012. [Internet] Disponível em: http://www. who.int/features/qa/34/en/. (Acessado em 12 de fevereiro de 2014)

5. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Ĉncer. O cigarro brasileiro: análises e propostas para redução do consumo. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2000.

6. The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations (DESA). World urbanization prospects. The 2007 revision. New York: DESA; 2008.

7. Brito F, Souza J. Expansão urbana nas grandes metrópoles: o signiicado das migrações intrametropolitanas e da mobilidade pendular na reprodução da pobreza. São Paulo Perspec 2005; 4: 48-63.

8. Chuang YC, Li YS, Wu YH, Chao HJ. A multilevel analysis of neighborhood and individual efects on individual smoking and drinking in Taiwan. BMC Public Health; 2007; 7: 151.

9. Adams RJ, Howard N, Tucker G, Appleton S, Taylor AW, Chittleborough C, et al. Efects of area deprivation on health risks and outcomes: a multilevel, cross-sectional, Australian population study. Int J Public Health 2009; 54(3): 183-92.

10. Ahern J, Galea S, Hubbard S, Syme S. Neighborhood smoking norms modify the relation between collective eicacy and smoking behavior. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009; 100(1-2): 138-45.

11. Cubbin C, Sundquist K, Ahlén H, Johansson SE, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Neighborhood deprivation and cardiovascular disease risk factors: protective and harmful efects. Scand J Public Health 2006; 34(3): 228-37.

12. Datta G, Subramanian SV, Colditz GA, Kawachi I, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Individual, neighborhood, and state-level predictors of smoking among US Black women: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med 2006; 63(4): 1034-44.

13. Diez-Roux AV, Nieto FJ, Mutaner C, Tyroler HA, Comstock GW, Shahar E, et al. Neighborhood environments and coronary heart disease: a multilevel analysis. Am J Epidemiol 1997; 146(1): 48-63.

14. Lima-Costa MFF. A saúde dos adultos na Região Metropolitana de Belo Horizonte: um estudo epidemiológico de base populacional. Belo Horizonte: Núcleo de Estudos em Saúde Pública e Envelhecimento, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais; 2004.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Plan and operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Series 1: programs and collection procedures. Washington: NCHS; 1994.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System [Internet]. 2001. Disponível em: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/. (Acessado em 15 de fevereiro de 2014).

17. Lê TN, Verma VK. Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). DHS Analytical Reports. An Analysis of Sampling Designs and Sampling Errors of the Demographic and Health Surveys. Calverton: Macro International Inc; 1997.

18. Reijneveld SA. The impact of individual and area characteristics on urban socioeconomic diferences in health and smoking. Int J Epidemiol 1998; 27(1): 33-40.

19. Patterson JM, Eberly L, Ding Y, Hargreaves M. Associations of smoking prevalence with individual and area level social cohesion. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004; 58(8): 692-7.

20. Giskes K, van Lenthe FJ, Turrell G, Brug J, Mackenbach JP. Smokers living in deprived areas are less likely to quit: a longitudinal follow-up. Tob Control 2006; 15(6): 485-8.

21. Duncan C, Jones K, Moon G. Smoking and deprivation: are there neighbourhood efects? Soc Sci Med 1999; 48(4): 497-505.

22. Chaix B, Chauvin P. Tobacco and alcohol consumption, sedentary lifestyle and overweightness in France: a multilevel analysis of individual and area-level determinants. Eur J Epidemiol 2003; 18(6): 531-8.

23. Reitzel LR, Vidrine JI, Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, Cao Y, Mazas CA, et al. Neighborhood perceptions are associated with tobacco dependence among African American smokers. Nicotine Tob Res 2012; 14(7): 786-93.

24. Shohaimi S, Luben R, Wareham N, Day N, Bingham S, Welch A, et al. Residential area deprivation predicts smoking habit independently of individual educational level and occupational social class. A cross sectional study in the Norfolk cohort of the European Investigation into Cancer (EPIC-Norfolk). J Epidemiol Community Health 2003; 57(4): 270-6.

25. Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. p. 465-86.

26. Sundquist J, Malmström M, Johansson SE. Cardiovascular risk factors and the neighbourhood environment: a multilevel analysis. Int J Epidemiol 1999; 28(5): 841-5.

Received on: 07/11/2013