FUNDAÇÃO

GETUUO VARGAS

EPGE

Escola de Pós-Graduaçãoem Economia

S~:l\lIN;\RIOS

Dl'

PLSQll\ S!\

ECONÔMICA

Rent- Sharing in Brazi1:

Using Trade Liberalization as

a Natural Experiment

Prof. Jorge Saba Arbache

(Universidade de Brasília)

LOCAL

Fundação Getulio Vargas

Praia de Botafogo, 190 - 1 Cf' andar - Auditório Eugênio Gudin

DATA

28/09/2000 (53 feira)

HORÁUIO

16:00h .

Rent-Sharing in Brazil:

Using Trade Liberalization as a Natural Experiment

Jorge Saba Arbache

Universidade de Brasília

Naercio Menezes-Filho

Universidade de São Paulo

Version 9/00

Abstract

This paper examines the extent of rent-sharing in Brazil, between 1988 and 1995, combining two different data sets: annual industrial surveys (pIA) and annual household surveys (PNADs). The aim is to use the trade liberalization policies that took place in Brazil in the early 1990s as a "natural experiment" to examine the impact ofproduct market rents on wages. We first estimate inter-industry wage differentials in Brazil, using the household surveys, afier controlling for various observable workers' characteristics. In a reduced form fixed effects equation, these controlled inter-industry differentials are seen to depend on the industries' rate of effective tariff. We also find that LSDV estimates of the effect of value-added per worker (computed using the industrial surveys) on the wage differentials are positive, but somewhat small. However, we find that instrumenting the valued-added with the effective tariffs more than doubles the estimated rent-sharing coefficient. The paper concludes that rent-sharing is prevalent in the Brazilian manufacturing sector, and this mechanism transferred part of the productivity gains due to trade liberalization to manufacturing workers in the form ofhigher (controlled) wage premium.

JELnumber: J31, J51, F16

Key-words: rent-sharing, wage determination, trade liberalization, Brazil

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank, without implicating, Francis Green, Andy Dickerson and Francisco Carneiro for useful comments and suggestions. Arbache gratefully acknowledges financiaI support from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, grant No. 300146/1000-0, and Economic and Social Research Council, grant No. R000223184.

1. Introduction

This paper aims at combining two different strands of the economlCS literature to

investigate the impact of trade liberalization on a developing country labor market. On the one

hand, economists have always been concemed about the extent to which wages are determined

by factors inside the firms vis-à-vis competitive forces. Many papers focused on the impacts of

product market rents (measured as profits, quasi-rents or value-added per employee) on wages

in different countries (see Nickell 1998, for a criticaI review). An obvious problem with these

studies is endogeneity, since wages and rents are likely to be simultaneously determined.

Some studies have tried to get around this problem by instrumenting or lagging the

product market rents. Using average industry profits and wages for the U.S., Blanchflower et aI

(1996) find that the effects of lagged profitability on wages are much higher than that of current

profits. Van Reenen (1996) uses lagged innovations as instruments for quasi-rents and finds that

this doubles the effects of these rents on wages. In a paper similar in approach to the one

adopted here, Abowd and Lemieux (1993) use foreign competition shocks as instruments and

also find that the standard O.L.S. estimates are downward biased. However, these papers are

also subject to some criticisms related to the choice of instruments. As Nickell (1998) points

out, improvements in the skilllevel of the workforce will tend to increase both quasi-rents and

wages so that they may well be correlated for spurious reasons.

The second line of the literature has been concemed about the relationship between

product market competition and performance. Again, Nickell (1998) reviews many theoretical

and empirical mo deis and conc1udes that "there is some theoretical foundation for the view that

product market power lowers productivity performance. However it is by no means strong and

there are results pointing in the opposite direction" (p.23). Moreover, "the balance of the

evidence suggests a negative relationship between product market power and productivity

performance. The force of the evidence is not, as yet, overwhelming" (p.24). In a similar vein,

many economists have been looking at the macro side of the story, by examining the effects of

trade liberalization on growth, inequality and welfare of developing countries that were

subjected to rapid and intense drop in trade barriers. Examples include Revenga (1992),

Robbins (1996, 1999), Hay (1998), Krueger (1997) and Edwards (1997), and these studies tend

to find that economic openness is good for growth but bad for inequality.

This paper combines these two strands of the literature by investigating the impact of

trade liberalization on wages in Brazilian manufacturing industries in the late 1980s and early

the impact of rents (measured as profitability or value-added per employee) on wages in an

instrumental variables framework. We use the rapid trade liberalization that took place in Brazil

in this period to identify the effect of product market rents on wages. However, contrary to these

papers (but similarly to Blanchflower et aI, 1996), we control for various observed workers

characteristics that may be changing simultaneously with trade liberalization.l We find that

instrumenting the quasi-rents leads to the doubling of the coefficient of rent-sharing in the

controlled wage premium equations, afier taking into account industry and year effects.

Our reduced-form equations show that, confirming previous evidence for the Brazilian

manufacturing industry (see Hay, 1998 and Rossi and Perreira, 1999), the falI in effective tariffs

provoked an increase in productivity and profitability, even afier controlling for industry fixed

effects. Moreover, and for the first time in the developing economies literature, we show that

the inter-industry wage differentials also depend on effective tariffs, with a decrease in effective

tariffs leading to increasing industry wage premiums, even afier controlling for workers

characteristics and industry fixed effects. Pinally, once we condition on product market rents,

there is no additional role for effective tariffs to increase wages.

The investigation ofthe case of Brazil seems to be an ideal opportunity to test the impact

of trade liberalization on wages because of its recent history. By the end of the 1980s, Brazil

was a very closed economy as a result of the import-substitution industrialization strategy

pursued for several decades. In 1990, Brazil under the Collor govemment, introduced a

reasonably rapid program of trade liberalization. The import penetration ratio in manufacturing

industry doubled in few years and the index of quantum of imports has tripled in the same

period. These factors make the Brazilian case an interesting 'natural experiment' which can

provide useful insights relating to debates over the impact oftrade on the labor market.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section presents some theoretical issues.

Section 3 documents the trade liberalization in Brazil. Section 4 describes the data and the

methodology. Section 5 presents and discusses our empirical results. Section 6 concludes.

2. Theoreticallssues

In the standard competitive mo dei, firms are wage-takers and therefore, there is no role

for profitability or quasi-rents to affect the wages received by their employees. This implies that

different industries will pay similar wages to similar workers, independent1y of their

profitability. However, as pointed out by Carruth and Oswald (1989) and Blanchflower et aI

(1996), it is possible to think of several ways through which the wage rates may depend on

product market rents. This could occur in bargaining models, where employees and finns

engage in a bargain, and the resulting wages will depend on the leveI of profitability or

quasi-rents per worker. As emphasized by Nickell (1998), this result is independent of the type of

bargaining that takes place, whether it is over wages and employment ("efficient bargaining"),

or over wages only ("right to manage''). Thefinal expression in both mo deIs will be something

like:

(1)

or

(2)

where wages (W;) depend on the altemative option (A), and a share (fi) of the profits per

employee (1) or quasi-rents (2), which depend on employment (N) and the firms' real revenue

(R(N».

In the framework proposed here, trade liberalization would increase competition, which

would modify the firm's production function, increasing its real revenue per worker. Part ofthis

increase would then be passed on to workers in the form of higher wages.2 Yet, the contrary

could happen if trade liberalization reduces monopoly power and rents. This could have a

negative effect on wage differentials. The literature on unions and intemational trade, for

example, shows that increasing imports and the removal oftrade barriers have a negative impact

on union wages (Driffill and van der Poeg, 1995, Freeman and Katz, 1991, MacPherson and

Stewart, 1990, Gaston and Tefler, 1995). Coumot and Dixit-Stiglitz type models can be used to

show that imports and exports influence union wages through the industry' s product market.

Greater imports (exports) increase (decrease) the product demand elasticity and reduce

(increase) profits, leading to wage concessions by unions. Our empirical model will, however,

be able to discriminate between the two hypothesis.

But how would trade liberalization affect productivity? One model that predicts exactly

this was developed by Hom et aI, (1995). In that paper the authors show that intemational trade

2 Profits and wages could also be positively correlated due to temporary frictions in the labor

- - - .

can yield welfare gains by reducing internaI slack, in a carefully crafted general equilibrium

trade model. The mo dei is based on the idea that firms are X-inefficient, in the sense that the

manager's effort levei induced by the optimal contract is too low, and production costs are too

high. In this setting, increasing externaI competition will lead to higher leveIs of managerial

effort, since demand becomes more elastic at the firm leveI, which leads to higher leveIs of

output per firmo Moreover, under full employment, the higher leveIs of output will tend to

increase labor market wages. Since managerial effort depends on wages and output leveIs, these

two effects willlead to higher leveIs of effort, which will reduce X-inefficiency.

3. Trade Liberalization in Brazil

Prior to 1990, the Brazilian economy was high1y protected and regulated, and public

sector companies dominated a variety of infra-structure activities, among other industries.

Successive administrations followed a vigorous import substitution industrialization strategy

expanding trade barriers not only through tariffs, but especially through import licenses,

different exchange rate regimes for imports and exports, among other measures such as taxes

and subsidies, aimed at protecting the domestic market. More than 50% of industrial products

were in the "Anexo C", a list of items that could not be imported. This large range of policy

instruments gave the govemment the discretion to impose barriers in order to protect sectors at

will.

The govemment decided to change the trade policy in 1988 lowering modestly the

tariffs and lifting some redundant barriers, but it did not affect significantly the international

trade. Kume (1989) argues that the reforms of the time were limited due to strong opposition

from producer interest groups. It was from 1990, under the president Collor administration,

when the efforts to contain inflation were combined with a drastic trade liberalization

constituting a major break with the import substitution strategy. The new govemment

introduced a four-year schedule to reduce the protection, but in practice it was completed in the

third year. Up to the middle of 1993, most of the complex and bureaucratic set of non-tariff

barriers was removed, and a new tariff structure was imposed, which substantially reduced the

degree of protectionism.

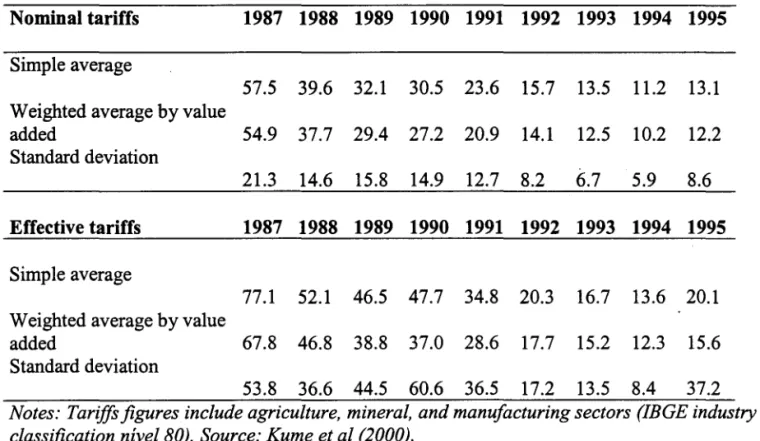

Table 1 shows that the nominal tariffs and effective tariffs dropped very rapidly in a few

years. In 1987, the national weighted average nominal tariffwas 55 percent; by 1992 it had been

reduced to 14 percent. This was accompanied by a sharp reduction in the modal tariff, bringing

tariff, which remained fair1y unchanged in the 1980s, dropped from 68 percent in 1987, to 18

percent in 1992, while the standard deviation dec1ined from 54 percent to 17 percent (Kume et

aI, 2000). As a result of the new economic policy and the overvaluation of exchange rate from

1990 to 1996, imports increased by 257 percent, while exports increased by 151 percent. By

1995, trade balance started to have increasing deficits.

Table 1 - Nominal and effective tariffs, 1987-1995

Nominal tariffs 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995

Simple average

57.5 39.6 32.1 30.5 23.6 15.7 13.5 11.2 13.1

Weighted average by value

added 54.9 37.7 29.4 27.2 20.9 14.1 12.5 10.2 12.2

Standard deviation

21.3 14.6 15.8 14.9 12.7 8.2 6.7 5.9 8.6

Effective tariffs 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995

Simple average

77.1 52.1 46.5 47.7 34.8 20.3 16.7 13.6 20.1

Weighted average by value

added 67.8 46.8 38.8 37.0 28.6 17.7 15.2 12.3 15.6

Standard deviation

53.8 36.6 44.5 60.6 36.5 17.2 13.5 8.4 37.2

Notes: Tariffsfigures inc/ude agriculture, mineral, and manufacturing sectors (IBGE industry c/assification nível 80). Source: Kume et aI (2000).

Contrary to what occurred in many other developing countries in which trade reforms

were gradually introduced and had a moderate impact (Adriamananjara and Nash, 1997), the

change in trade policy in Brazil seems to have impacted the economy in a more radical manner.

The tariff reduction itself was not strong by intemational standards, however, but it was the

removal of the non-tariff barriers that definitely shifted the pattem of protection. Considering

that the Brazilian economy was large1y c10sed to trade, the new policy was a significant move,

especially for the manufacturing sector, signaling that the long period of protectionism was

coming to an end.

The impacts of the trade liberalization can be depicted by the very rapid rise in the

import penetration ratio in the manufacturing sector, and by the index of quantum of aggregate

imports illustrated, respectively, in figures 1 and 2. There is a c1ear shift in the import pattem

from 1990 onwards. By 1996, the import penetration ratio had reached 11.5 - more than twice

the figure for 1990, and the quantum of imports had increased almost three times. These

evidences suggest significant allocative changes in the economy with potential effects in the labor market. 12 10 8 6 4 2 O

Figure 1: Import penetration ratio - manufacturing sector

~

/

r--. /

...-1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996

Figure 2: Index of quantum of aggregate imports

120.---, 100

+---/....,...

80+---~~~

60+---~~--~

40

t:;;:;:;;::;:~~~:!::===~

20 """""

0+-~--~~--~--~_r--~~--~~__4

V'l 00

0'1

r-- 00

00 00

0'1 0'1

0'1 o - N

('f')

00 0'1 0'1 0'1 0'1

0'1 0'1 0'1 0'1 0'1

4. Data and Econometric Methodology

The data used in this paper come from two sources. One is the National Household

Survey (PNAD), and the other is the Annual Industrial Survey (PIA), both conducted yearly by

the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Each PNAD contains data on about a

hundred thousand randomly selected households throughout the country,. fully describing a

substantial number of individual and household characteristics for labor market analyses. The

sample data we analyze were filtered in the following way: non-employers between the ages of

18 and 65, earning positive salary and affiliated to any of the 18 industries that comprise the

manufacturing sector. This cIassification corresponds to the 2-digit SIC. The reported wages are

monthly wages in the main occupation that individuaIs held during the period of interview. In

order to obtain hourly wages, we divided the monthly wage by the product of usual weekly

and transfonned to naturallogarithms. The PIA is a panel based survey of about 7.7 thousand

randomly selected finns aimed at collecting data on employment, wages, profits, value added,

investment, sales, output, intennediate consume, among other finn leveI variables. We combine

PNAD and PIA through the workers' industry affiliation.

In this study, we intend to firstly run individual leveI wage equations, as in Blanchflower

et aI (1996), to compute the inter-industry wage differentials, after controlling for the workers

observable characteristics. The strategy we adopt to estimate the inter-industry differentials is

through the approach proposed by Haisken-DeNew and Schmidt (1997), which improves the

standard procedure popularized by Krueger and Summers (1988). The wage equations are

estimated in the following fonn:

(3)

where lnwij is the natural logarithm of the hourly real wage of worker i in industry j,

J4

is avector of personal characteristics, 'Zj is a vector of industry dummies which includes ali

industries, a is the intercept tenn, Eij is a random disturbance tenn reflecting unobserved

characteristics and the inherent randomness of earnings statistics, and

f3

and cp are the vectorsof parameters to be estimated. Since in this model the cross-product matrix of the regressors is

not offull rank, a linear restriction is imposed on the cps as follows,

(4)

where nj is the employment share in industry j. The reported coefficients can then be interpreted

as the proportionate difference in wages between a worker in industry j and the average worker

from the whole of manufacturing industry, after controlling for the other factors which

detennine wages. The fonnulation given by (3) and (4) provides both economically sensible

coefficients and their correct standard errors in a single regression step (see Haisken-DeNew

and Schmidt, 1997 for further details).

In the second step, these estimated inter-industry wage differentials will fonn the

dependent variable in the industry leveI wage premium equations. In the reduced fonn, these

differentials will be explained by effective protection tariffs, as computed by Kume et aI

(2000).3 Finally, a structural equation is estimated, whereby the wage differentials will be

explained by proxies of industries' product market rents. This variable will be instrumented

with the effective tariffs, in a Two-Stages Least Squares framework. Both in the first and in the

To proxy for product market rents, we focus on three different measures. The first and

preferred one is a measure of value-added divided by the total number of employees. Value

added is measured as total sales plus variation in inventories, minus all direct and indirect costs

related to the consumption of raw-materials, energy and capital depreciation. The second one

divides value-added by the number of blue collar employees. Finally, the third one is

profitability per employee, measured as total sales' revenue minus total costs, which inc1ude

raw materiaIs costs, wages and benefits, all measured in real 1996 values. We take logs of the

productivity measures and of the effective tariffs, but profitability is inc1uded in leveIs due to

some existing negative values.

We preferred to run fixed effects rather than first-differences equations, because of

missing data for 1991 and 1994 for wages,4 and because of the chaotic macroeconomic

environment in Brazil in the data period. The difficulty of measuring our economic variables in

periods of high inflation impregnates the data with measurement error that are magnified in

first-differences specifications (see Griliches and Hausman, 1986 and Hay, 1998).

5. Results

5.1 Wage Differentials

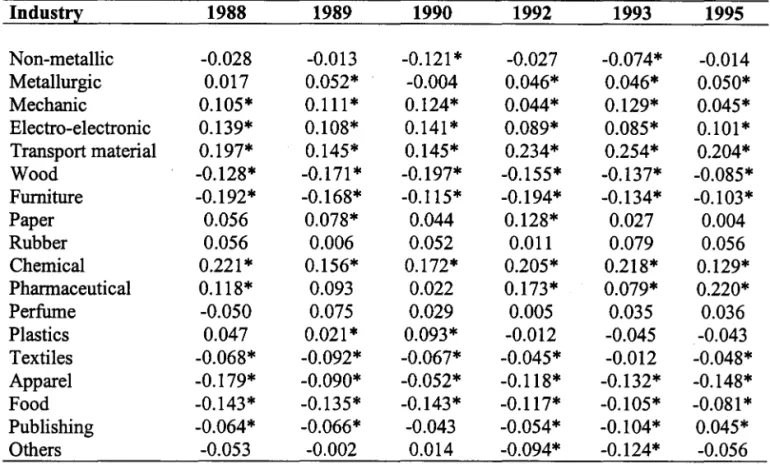

The coefficients in table 2 show the proportionate difference in wages between an

employee in a given industry and the weighted average worker in manufacturing. The figures

indicate that, for instance, in 1988 a worker in the non-metallic industry eamed about 3 percent

less than the average manufacturing wage, while a worker in the transport material industry

eamed about 22 percent above the mean wage. The wage equation used to estimate the

inter-industry wage differentials were controlled for education, experience, experience square,

gender, race, head of family, metropolitan area, urban-rural area, regions and work card.5

3 The effective tariff is defined as the percentage increase of the domestic value added due to the tariff and non-tariffbarriers related to the value added obtained in free trade.

4 There were no PNAD for 1991 and 1994 due to population census and shortage of funds,

respectively. .

~----~---...,

Thus, the estimated coefficients may capture not only unrneasured abilities, but also all other

factors affecting the industry affiliation, such as market structure, profitability and technology.6

Table 2 - Inter-Industry Wage Differentials

Industry 1988 1989 1990 1992 1993 1995

Non-metallic -0.028 -0.013 -0.121* -0.027 -0.074* -0.014

Metallurgic 0.017 0.052* -0.004 0.046* 0.046* 0.050*

Mechanic 0.105* 0.111 * 0.124* 0.044* 0.129* 0.045*

Electro-electronic 0.139* 0.108* 0.141 * 0.089* 0.085* 0.101 *

Transport material 0.197* 0.145* 0.145* 0.234* 0.254* 0.204*

Wood -0.128* -0.171* -0.197* -0.155* -0.137* -0.085*

Furniture -0.192* -0.168* -0.115* -0.194* -0.134* -0.103*

Paper 0.056 0.078* 0.044 0.128* 0.027 0.004

Rubber 0.056 0.006 0.052 0.011 0.079 0.056

Chemical 0.221 * 0.156* 0.172* 0.205* 0.218* 0.129*

Pharmaceutical 0.118* 0.093 0.022 0.173* 0.079* 0.220*

Perfume -0.050 0.075 0.029 0.005 0.035 0.036

Plastics 0.047 0.021 * 0.093* -0.012 -0.045 -0.043

Textiles -0.068* -0.092* -0.067* -0.045* -0.012 -0.048*

Apparel -0.179* -0.090* -0.052* -0.118* -0.132* -0.148*

Food -0.143* -0.135* -0.143* -0.117* -0.105* -0.081*

Publishing -0.064* -0.066* -0.043 -0.054* -0.104* 0.045*

Others -0.053 -0.002 0.014 -0.094* -0.124* -0.056

Note: * Significant at the 5% leveI.

5.2 Effects of Product Market Rents on Wages

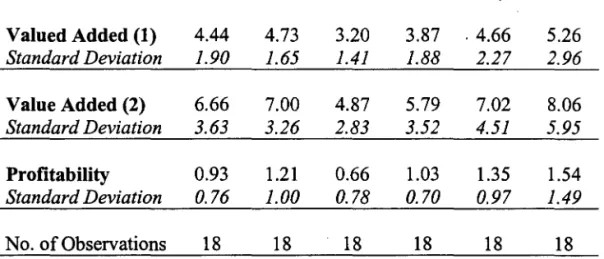

The results of estimating the impact of value-added on wages are set out in tables 3 to 6.

In table 3, we describe the evolution of our measures of product market rents over the sample

period. It is possible to distinguish at least two different trends. In the first period, between 1988

and 1990, all measures dropped substantially, possibly due to the deep recession that took place

in 1990. Then, productivity tends to rise continuously until the end ofthe period. To what extent

this was due to the threat of foreign competition (trade liberalization effect) 'or to the c1eansing

effect ofrecession is something we investigate below.

Table 3- Value Added per Employee and Profits per Employee Over Time

1988 1989 1990 1992 1993 1995

Valued Added (1) 4.44 4.73 3.20 3.87 .4.66 5.26

Standard Deviation 1.90 1.65 1.41 1.88 2.27 2.96

Value Added (2) 6.66 7.00 4.87 5.79 7.02 8.06

Standard Deviation 3.63 3.26 2.83 3.52 4.51 5.95

Profitability 0.93 1.21 0.66 1.03 1.35 1.54

Standard Deviation 0.76 1.00 0.78 0.70 0.97 1.49

No. of Observations 18 18 18 18 18 18

Notes: All variables measured in R$ 10,000 of 1996

In table 4 we investigate the basie eorrelations between wage differentials and rents. We

do so by regressing the wage differentials estimated in seetion 5.1 on our three measures of

product market rents separately (eaeh row presents the results of a separate regression). We ean

see in the first eolumn, where no controls are inc1uded, that the relationship between our first

normalized value added measure and the wage premium is estimated to be positive and

signifieantly different from zero. Furthermore, it remains so even afier time dummies (eolumn

2) and industry dummies (eolumn 3) are inc1uded. Finally, similar results are obtained when we

divide value added by the number ofproduetion workers only (value added 2), and when we use

profits per employee altematively as regressors.

Table 4 - Industry Wage Differentials and Product Market Rents

Wage Differentials (1) (2) (3)

Value Added (1) 0.177 0.196 0.084

Standard Error 0.010 0.011 0.026

Value Added (2) 0.137 0.145 0.087

Standard Error 0.008 0.009 0.025

Profitability 0.042 0.046 0.013

Standard Error 0.008 0.010 0.006

Time Dummies No Yes Yes

Industry Fixed Effeets No No Yes

No. Of Observations 108 108 108

Table 5 sets out our reduced form equations. It shows that, although the controlIed wage

differentials are positively correlated to effective tariffs in leveIs (column 1), this seems to be

due to correlated industry effects, since when industry dummies are inc1uded (column 2), the

sign is reversed and one can see that more protected industries tend to pay lower wages. The

basic positive correlation seems to be driven by the fact that more protected industries had some

form of managerial slack, so that they paid higher wages because of inefficiency. It is

interesting to note that when import penetration is inc1uded in the equation together with tariffs

(results not shown) , the tariffs effect dominates and the import penetration variable enters

insignificant1y.

In columns 3 and 4 we present the results of regressing (the log oi) value added per

employee on (the log oi) effective protection. Valued-added per employee is not correlated with

protection in the leveIs specification, and profits per employee are negatively so. After

controlling for industry effects, however, one can see that productivity tends to increase when

trade liberalization takes place. It is important to stress that these effects are conditional on year

effects, that control for macroeconomic conditions and for the downward trend in protection

that affects alI industries at the same time. This means that we are looking at the effects of

inter-industry variation over time in effective protection on performance. Columns (5) and (6) show

that the results are maintained when we use a different measure of rents, that is, profits per

employee.

Table 5 - Reduced-Forms Wage Differentials and Quasi-rents

De endent Variable

Effective Tariffs 0.048 -0.023 0.000 -0.135 -0.531 -0.979

Standard Errar 0.019 0.014 0.075 0.046 0.158 0.200

Time Dummies Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Industry Fixed Effects No Yes No yes No Yes

No. Of Observations 108 108 108 108 108 108

FinalIy, in Table 6 we present the main results of this paper. In the first column, we

reproduce the results from table 4 (column 3), for comparison. In .the second column, we

instrument the different proxies for product market rents with the effective tariffs. One can see

in the first row that the estimated coefficient on value added per employee basicalIy doubles

· encountered for the other measures of rents, like valued-added divided by the number of blue

collar workers and profits per employee, meaning that this result is very robust.

Table 6 - Two-Stages Least Squares Estimations of Rent-Sharing

Wage Differentials (1) (2)

Value Added (1) 0.084 0.170

Standard Error 0.026 0.103

Value Added (2) 0.087 0.151

Standard Error 0.025 0.092

Profitability 0.013 0.028

Standard Error 0.006 0.016

NO.ofObservations 108 108

Notes: Equations estimated by OLS in column(1) and and by 2SLS in column(2)

6. Conclusions

In this paper we examined whether workers tend to share the good times with the finns

in Brazil. The answer is yes. We reported results showing that the inter-industry wage

differentials, controlled for skill and other observed characteristics, is positively correlated with

product market rents, even conditionally on time and industry effects. However, wages and

profits are simultaneously detennined, and this means that we could be underestimating the true

effect. The fact that a rapid trade liberalization process took place in Brazil in our sample period

means that, if this episode affected industries' rents as it seems likely, we would have a natural

instrument to identify the effect of rents on wages. Therefore, we used the leveI of effective

tariffs as an instrument for valued added per employee (and other measures on rents) in industry

leveI wage regressions. The results showed that the product market rents were strongly affected

by trade liberalization, and that part of this effect was carried out to the labor market in the fonn

ofhigher wage premium paid by positively affected finns.

Taken as a whole, the results suggest that there were a number of sectors in the Brazilian

manufacturing industry that had their productivity increased as the result of trade liberalization.

ones that remained employed shared this increasing productivity with their firms in the form of

higher wages.

In terms of the country's welfare, the overall results will depend on whether the

unemployment generated is only a short-term phenomenon, or will persist over the long run.

References

Abowd, J. and Lemieux, T. (1993). "The Effects ofProduct Market Competition on Collective

Bargaining Agreements: The Case of Foreign Competition in Canada", Quarterly

JournalofEconomics, 108,983-1014.

Adriamananjara, S and Nash, J. (1997). "Have Trade Policy Reforms Led to Greater Openness

in Developing Countries?". Policy Research Working Paper No. 1730, World Bank.

Berman, E. and Machin, S. (1999). "Skill-Biased Technology Transfer: Evidence of Factor

Biased Technological Change in Developing Countries", Boston University, mimeo.

Blanchflower, D., Oswald, A and Sanfey, P. (1996). "Wages, Profits and Rent-Sharing",

QuarterlyJournalofEconomics, 111,227-51.

Carruth, A.A. and Oswald, A.J. (1989), "Pay determination and Industrial Prosperity", Oxford:

Clarendon Press.

Driffill, J. and van der Poeg, F. (1995). "Trade Liberalisation with Imperfect Competition in

Goods and Labour Markets", Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 97, 223-243.

Edwards, S. (1997). "Openness, Productivity and Growth: What do we Really Know?", NBER

Working Paper 5978.

Freeman, R.B. and Katz, L.F. (1991). "Industrial Wage and Employment Determination in an

Open Economy", in J.M. Abowd and R.B. Freeman (edits.), Immigration, Trade, and the

Labor Market, Clllcago: University of Chicago Press.

Gaston, N. and Tefler, D. (1995). "Union Wage Sensitivity to Trade and Protection: Theory and

Evidence", Journal ofInternational Economics, 39, 1-25.

Griliches, Z. and Hausman, J. (1986). "Errors in Variables m Panel Data" Journal of

Econometrics, 31, 93-118.

Haisken-DeNew, J. and Schmidt, C. (1997). "Inter-Industry and Inter-Region Wage

Differentials: Mechanics and Interpretation: Review of Economics and Statistics, 79,

Hay, D. (1998). "The Post 1990 Brazilian Trade Liberalization and the Perfonnance of Large

Manufacturing Firms: Productivity Market Share and Profits", Institute of Economics

and Statistics, Applied Economics Discussion Papers Series No. 196, University of

Oxford.

Hom, H., Lang, H. and Lundgren, S. (1995). "Managerial Effort Incentives, X-Inefficiency and

Intemational Trade", European Economic Review, 39, 117-138.

K.rueger, A and Summers, L. (1988). "Efficiency Wages and the Inter-Industry Wage

Structure", Econometrica, 56, 159-193.

K.rueger, A (1997) " Trade Policy and Economic Development: How We Leam", American

Economic Review, 87, 1-22.

Kume, H. (1989). "A Refonna Tarifária de 1988 e a Nova Política de Importação", Texto para

Discussão No. 20, Fundação Centro de Estudos do Comércio Exterior.

Kume, H., Piani, G. and Souza, C.F. (2000). "Instrumentos de Política Comercial no Período

1987-1998", mimeo, Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada.

MacPherson, D.A. and Stewart, J.B. (1990). "The Effect oflntemational Competition on Union

and Nonunion Wages", Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 43, 435-446.

Nickell, S. (1998). "Product Market and Labour Markets", mimeo, Institute of Economics and

Statistics, University of Oxford.

Revenga, A. (1992). "Exporting Jobs? The Impact of Import Competition on Employment and

Wages in US Manufacturing", Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107,255-84.

Robbins, D. (1996) "HOS Hits Facts: Facts Win: Evidence on Trade and Wages in the

Developing World", Development Discussion Paper No. 557, Harvard Institute for

Intemational Development, Harvard University.

Robbins, D.J. e Gindling, T.H. (1999). "Trade Liberalization and the Relative Wages for

More-Skilled Workers in Costa Rica", Review ofDevelopment Economics, 3, 140-154.

Rossi, J. and Ferreira, P. (1999). "Trade Barriers and Productivity Growth: Cross-Industry

Evidence", mimeo Fundação Getúlio Vargas.

Van Reenen, J. (1996) "The Creation and Capture ofRents: Wages and Innovation in a Panel of

UK Companies", Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111, 195-226.

Wood, A. (1994). North-South Trade, Employment and Inequality: Changing Fortunes in a

Appendix

In order to estimate the inter-industry wage dispersion, we computed the following

expresslOn:

SD(rp) =

~n'(H(rp)rpj

-n'D(V(rp).SD(rp) gives the weighted and adjusted standard deviation of coefficients, H(.) transforms a

column vector into a diagonal matrix whose diagonal is given by the column vector itself, D

denotes the column vector formed by the diagonal elements of a matrix, and V is the

variance-covariance matrix.

The figures below show that the inclusion of control variables in the model could reduce

about 51 percent ofthe wage dispersion for the whole years, except for 1995, when the controls

reduced 58 percent ofthe dispersion. This result suggests that the model could better explain the

wage determination in 1995, when the trade liberalization had already been introduced.

Weighted and adjusted inter-industry wage dispersion

1988 1989 1990 1992 1993 1995

No Control 0.2618 0.2285 0.2274 0.2358 0.2463 0.2352

Control 0.1280 0.1056 0.1095 0.1186 0.1253 0.0985

000304416