pISSN 1899-5241 eISSN 1899-5772

2(36) 2015, 353–361

prof. Yumei Xie, Department of Finance, School of Business, Jiangnan University, NO. 1800 Lihu Avenue, Wuxi, Jiangsu

Province, 214122, China, e-mail: xieym66@jiangnan.edu.cn Abstract. The aim of the paper. The aim of the paper is to

evaluate the impact of factors determining the transition to organic farming and provide some recommendations for gov-ernment’s policy relating to organic farming. Material and research method. An analysis was based on questionnaire sur-vey on the willingness of organic farming by small farmers in the province of Jiangsu. Binary logistic regression model was used in the research. Concluding remarks. Żive factors affecting organic agricultural production were discoveredŚ farmers’ age, risk preferences, labour costs, expected benefi ts and the environment. On this ground, the authors suggest, that Chinese government should adopt policies assisting farmers in the transition to organic farming for the sustainable devel-opment of China’s organic agriculture. Cooperation of farm-ers’ cooperatives and research institutions to improve organic farming techniques should also be promoted.

Key words: organic agriculture, infl uential factors in

organ-ic farming, government polorgan-icy

INTRODUCTION

In order to regulate the production and certifi cation of organic agriculture, China formulated a wide range of relevant laws and standards at the beginning of the 2ńst

century, which have greatly contributed to the develop-ment of organic farming. At the end of 2Ńń2 China’s or-ganic agricultural land stretched over an area of ń.ř mil-lion hectares. It was ranked as the fourth in the world, represented Ń.36% of the total area of agricultural pro-duction. As of the fi rst quarter of 2Ńń3, 24 organic cer-tifi cation bodies granted organic accreditation to 8262 products (China’s Żood…, 2Ńń4). In 2Ńń2, 685 food manufacturing companies (including ń2 foreign compa-nies) and 2762 products received organic accreditations (The →orld of Organic Agriculture…, 2Ńń4).

In view of factors affecting organic farming, this pa-per analysed the willingness of farmers to run organic farming on the basis of the survey of farmers in Jiangsu, a leading province in organic agriculture. The aim of this paper is to evaluate the impact of those infl uential factors and provide some recommendations for govern-ment’s policy relating to organic farming. The article consists of three parts and a summary. The fi rst part pre-sents the stages of development of organic agriculture in China. The second part describes the research project and shows the survey results. The third part discusses the main factors affecting organic production. Some suggestions for policy supporting organic agriculture in China are given in the summary.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF ORGANIC AGRICULTURE

IN CHINA AND THE FACTORS AFFECTING ORGANIC

FARMING

*Yumei Xie

1, Hailei Zhao

1, Karolina Pawlak

2, Yun Gao

11Jiangnan University

2Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy w Poznaniu

THE STATUS QUO OF ORGANIC AGRICULTURE IN CHINA

In the early ńř8Ńs China began to develop organic farm-ing. In ńř8ř the Rural źcological Research Centre of the Nanjing Institute of źnvironmental Sciences, a branch of the State źnvironmental Protection Agency, joined the The International Żederation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IŻOAM) and became its fi rst member in China. In the ńřřŃs organic farming was growing very slowly in China.

At the beginning of the 2ńst century, the State źnvi-ronmental Protection Administration offi cially released the Organic Food Certifi cationRegulation, followed by the Organic Product Certifi cation Regulations and the Organic Product Certifi cation Implementation Rules. These acts defi ne organic certifi cation and organic prod-ucts, set standards for organic certifi cation bodies and certifi ers, basic principles for organic certifi cation, or-ganic labels, import requirements, international cooper-ation and regulatory initiativesś as well as specify goals of organic certifi cation, scope of applications, standards of certifi cation, procedures of certifi cation, postcertifi -cation management, credentials, certifi -cation labels and certifi cation fees.

In 2ŃŃ3 the State Council of the People’s Republic of China issued Certifi cation and Accreditation Regu-lations of the People’s Republic of China. All certifi ca-tion bodies including organic certifi caca-tion bodies must meet these regulations. On ńř January 2ŃŃ5 the Orga-nic Product Certifi cation Implementation Rules andthe Chinese National Organic Standards żB/Tńř63Ń-2ŃŃ5 were offi cially released. In 2Ńń2 the abovementioned Chinese organic standards and rules were revised, and the organic product certifi cation directory was enacted, establishing more stringent requirements for organic production, processing, marketing standards and certifi -cation procedures. In 2Ńń4, new Organic Product Certi-fi cation Regulations were adopted to further strengthen the complete supervision. Those standardizations of or-ganic product certifi cation have substantially promoted the development of organic farming in the countryside.

As far as the regional distribution of organic agri-culture China is concerned, the vast majority of organic plant production is concentrated in eastern coastal re-gions and north-eastern provinces, while organic animal husbandry is focused in western areas. The northeast region, including Heilongjiang Province, Jilin Province,

Liaoning Province and Inner Mongolia, has the great-est variety and yield of organic agricultural production, as well as the largest area of certifi ed organic agricul-tural products, where cereals and soybeans are the main types. The eastern region, including Beijing, Shanghai, Shandong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Jiangxi and Żujian prov-inces, is dominated by the production of organic fruit and vegetables, tea and processed organic products.

In 2ŃńŃ the total sales of organic products was ń5.ńř billion yuan (2.3Ń billion USŹ), including 8.ńń billion yuan (ń.23 billion USŹ) of plant origin products sales, followed by 2.řń billion yuan (Ń.44 billion USŹ) of pro-cessed products sales. →ild collection, animal husband-ry and fi shehusband-ry products had relatively smaller sales, i.e. ń.33 billion yuan (Ń.2Ń billion USŹ), ń.ń4 billion yuan (Ń.ń7 billion USŹ) and 82Ń million yuan (ń24 million USŹ), respectively. On the provincial level, Shandong, Jiangxi and Jiangsu are the top three provinces in or-ganic sales, amounting to ń.62 billion yuan (Ń.25 billion USŹ), ń.ń6 billion yuan (Ń.ń8 billion USŹ), and ř8Ń million yuan (ń4ř million USŹ), respectively (Statisti-cal Yearbook…, 2ŃńŃ).

In 2ŃńŃ China’s export of organic products to more than 2Ń countries reached 6.5 billion yuan (Ń.řř billion USŹ). źurope, North America and Japan were the main destinations. According to statistics, the exports of or-ganic products ranging from the highest to the lowest are as followsŚ planting, fi shery products, wild collec-tion, processed goods, and animal husbandry. In terms of products varieties, beans are the product with the highest exports, making 42% of China’s total exports of organic agricultural products. They are followed by grains, nuts, vegetables and tea. In organic products ex-ports, Shandong, Żujian and Jiangsu are the top three provinces, amounting to 2.64 billion yuan (Ń.4Ń billion USŹ), ń.ń6 billion yuan (Ń.ń8 billion USŹ) and ř8Ń million yuan (ń4ř million USŹ) respectively (Statistical Yearbook…, 2ŃńŃ).

FACTORS TAKEN INTO CONSIDERATION WHEN DECIDING FOR TRANSITION TO ORGANIC FARMING

production and the USA provides fi nancing, insurance and technology, which have greatly contributed to the development of organic farming in this country. A lot of papers have discussed those infl uential factors in organ-ic farming, including farmers’ age and education, prorgan-ice of organic products, expected income, the environment benefi ts and food quality.

Żor example, Burton et al. (ńřřř), Läpple and van Rensburg (2Ńńń), żenius et al. (2ŃŃ6), as well as Zhu (2ŃŃ7) used a binary logistic model and found that age of farmers had signifi cant negative impact on the adop-tion of organic producadop-tion, while Cheng et al. (2ŃŃř) and →ang (2Ńń2) drew the opposite conclusion. Anderson et al. (2ŃŃ5) discovered that age did not have signifi -cant impact on organic farming.

Burton et al. (ńřřř), Läpple and van Rensburg (2Ńńń), żenius et al. (2ŃŃ6) and Ceylan et al. (2ŃńŃ) observed that the environmental factors were one of the most important factors affecting farmers’ decisions on organic production. Additionally, according to local farmers’ characteristics and various research purposes other variables were also chosen by them, including family size, income level, the area of arable land, sales methods, sources of information, types of land owner-ship, farm machinery, membership in rural or environ-mental organisations, sponsorship by government or non-government groups, experience of receiving rel-evant training, satisfaction about the price of organic products, difference between organic products and or-dinary products, etc.

Besides, Żairweather (ńřřř) applied the game theo-ry and the decision tree to analyse different motivations and constraints when households made decisions for or against transition to organic farming. Läpple and Kel-ley (2Ńń3) surveyed Irish farmers, applying planned actions theory, clustering methodology and principle component analysis to fi nd that changes in economic incentives and technical barriers, as well as social ac-ceptance of organic agriculture would constrain farm-ers’ selection of organic farming. Chen et al. (2ŃŃř) built a quality investment model of food producers and found that the main factors affecting the behaviour of organic producers were the prices of organic food, coeffi cient of productivity variation, capital adequacy of producers, costs of investment and government support.

However, due to the high costs of transition to or-ganic farming and because of uncertainty on the market,

instead of complete reliance on market mechanism two methods must be supplemented to induce farm-ers’ preference to organic farming, including farmfarm-ers’ environmental responsibility and government subsidies. Zhang (2Ńńń) found that organic products have to secure relatively high market prices to maintain sustained pro-duction. Therefore, government should step up support policy to develop organic farming.

To sum up, the abovementioned studies primarily fo-cused on farmers’ own endowments and market factors affecting organic farming. But the authors assume that a number of factors including funding, risks, and barriers to transition to organic farming are also variables of vi-tal importance in farmers’ decisions concerning organic production. Therefore, the authors focused on Jiangsu, the top organic province in China, and used the binary logistic model to discuss the transition barriers and ex-pected revenue from organic farming.

THE RESEARCH DESIGN AND SAMPLE DESCRIPTION

The Research Design

Jiangsu is one of China’s fastest growing organic farm-ing provinces in terms of the number of companies mak-ing organic products, the amount of processed organic products, domestic sales and exports. Local govern-ments have introduced many policies to support and en-courage farmers to switch to organic farming. Initially, the authors chose peach farmers in their research facility and had a small talk with them. They interviewed ń6Ń farmers, but the effective sample was ń4Ń. The survey was conducted from ń March to May 2Ńń3.

The contents of the questionnaire was as followsŚ a) general characteristics of rural households, in-cluding age, educational status of householder, the num-ber of family memnum-bers, the numnum-ber of farm workers, the average annual household income, etc.ś

b) data on production of orchardists, including plant-ing varieties, entitlement to agricultural preferential policies, farm loan history, and agricultural insurance experience, etc.ś

The sample description

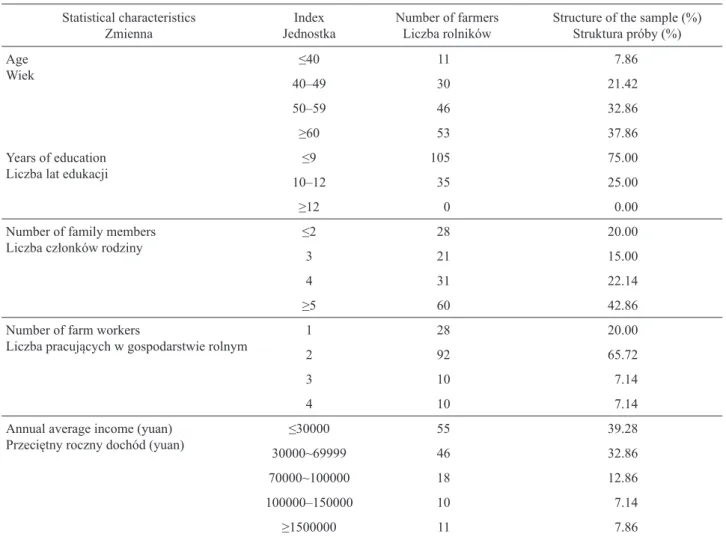

The study showed that 7Ń.7% of the respondents were aged over 5Ń years. 75% of them completed less than nine years of education. About 42.ř% households had more than 5 members, whereas households with ń or 2 farm workers made up 85.7% of the sample. In addi-tion, 3ř.3% of surveyed households earned annual in-come less than 3Ń ŃŃŃ yuanń, 32.ř% had annual income between 3Ń ŃŃŃ and 7Ń ŃŃŃ yuan, and 27.ř% house-holds reached annual income exceeding 7Ń ŃŃŃ yuan

ń ń USŹ = 6,ń3 yuan (according to the exchange rate of the

NBP on May 3ń, 2Ńń3, when the survey was completed).

(Table ń). →hat is important, ń5% of the respondents said that agricultural income made over 7Ń% of the total income in their households.

Knowledge about organic farming among the sur-veyed farmers can be described as followsŚ

a) Answering the questionŚ Have you ever heard about organic farming?, 36.43% of the farmers said that they had heard about organic farming beforeś

b) As far as understanding the organic production standards, technologies, certifi cation system, and trace-ability system of organic food is concerned, 74.3% of the farmers had no idea about production standards and technologies of organic farming, while none of surveyed Table 1. Źescription of the sample of farmers

Tabela 1. Charakterystyka próby rolników

Statistical characteristics

Zmienna JednostkaIndex Number of farmersLiczba rolników Structure of the sample (%)Struktura próby (%) Age

→iek 4Ń–4ř ≤4Ń ńń3Ń 2ń.427.86

5Ń–5ř 46 32.86

≥6Ń 53 37.86

Years of education

Liczba lat edukacji ńŃ–ń2≤ř ńŃ535 75.ŃŃ25.ŃŃ

≥ń2 Ń Ń.ŃŃ

Number of family members

Liczba członków rodziny ≤2 3 282ń 2Ń.ŃŃń5.ŃŃ

4 3ń 22.ń4

≥5 6Ń 42.86

Number of farm workers

Liczba pracujących w gospodarstwie rolnym ń 2 28ř2 2Ń.ŃŃ65.72

3 ńŃ 7.ń4

4 ńŃ 7.ń4

Annual average income (yuan)

Przeciętny roczny dochód (yuan) 3ŃŃŃŃ~6řřřř≤3ŃŃŃŃ 5546 3ř.2832.86

7ŃŃŃŃ~ńŃŃŃŃŃ ń8 ń2.86

ńŃŃŃŃŃ–ń5ŃŃŃŃ ńŃ 7.ń4

≥ń5ŃŃŃŃŃ ńń 7.86

SourceŚ own elaboration based on the questionnaire survey (n = ń4Ń).

farmers did not understand organic farming thoroughly. Moreover, 84.3% and 83.6% of the surveyed farmers showed a total lack of understanding the organic cer-tifi cation system and organic food traceability system, respectively (Table 2)ś

c) Żarmers’ experience of receiving organic produc-tion training or guidance was also investigated. The study showed that only ń.43% of the farmers had ever taken part in trainings or received guidance on organic production. These data suggest that the farmers’ know-ledge about organic farming was very limited.

THE EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

Model selection

To implement the logistic regression, which is well de-veloped in model diagnosis in recent years, the depend-ent variable has to be binary and the independdepend-ent varia-ble can be of various types. Those demands on variavaria-bles just serve the purpose of our analysis. Therefore, authors chose the binary logistic regression method (Binary Lo-gistic Regression, BLR) as the empirical research meth-od to assess the factors affecting farmers’ willingness to engage in organic agricultural production.

The logistic regression model consisting of n inde-pendent variables can be described asŚ

logit(P) = βŃ + βńXń + β2X2 + ··· + βnXn

logit(P) = ln(P(Yń)/P(YŃ)) logit(P) = ln(P(Yń)/P(YŃ)) = = βŃ + βńXń + β2X2 + ··· + βnXn

In the equation above, Yń means the farmer is willing to engage in organic production, YŃ means the farmer is reluctant to engage in organic production. The left side of the equation denotes the natural logarithm of likeli-hood which corresponds to the ratio of the occurrence and non-occurrence of events. The independent vari-ables Xń to Xn on the right side of the equation represent

various possible infl uential factors affecting the farm-ers’ willingness to conduct organic agricultural produc-tion. βŃ is the constant (intercept), and βń to βn are the

regression coeffi cients (sloaps), which are the estimated parameters measuring the resultant change in log likeli-hood for a one-unit change in the independent variable. Therefore, this model can refl ect the infl uence and sig-nifi cance of each independent variable on the dependent variable.

The selection and defi nition of the variables According to the purpose of this study, combined with the abovementioned theory of planned behaviour, as well as domestic and foreign research results and the reality of Chinese countryside, this article classifi es the factors affecting farmers’ decision to engage in or-ganic agricultural production into the following three Table 2. Żarmers’ cognition in organic agriculture (%)

Tabela 2. Stopie znajomo ci systemu rolnictwa ekologicznego (%)

źvaluation Ocena

Organic production standards and technologies Standardy i technologie produkcji

ekologicznej

Organic certifi cation system System certyfi kacji produkcji

ekologicznej

Organic food traceability system System identyfi kacji i ledzenia pochodzenia ywno ci ekologicznej

No idea

aden 74.28 84.2ř 83.58

Some

Znikomy ńř.2ř ń3.57 ń5.7ń

A little

Niski 6.43 2.ń4 Ń.7ń

Żamiliar

Źobry Ń.ŃŃ Ń.ŃŃ Ń.ŃŃ

SourceŚ own elaboration based on the questionnaire survey (n = ń4Ń).

categories. The fi rst category denotes farmers’ charac-teristics, including age of the householder (Xń) and risk preferences (X2)ś the second category concerns expected obstacles in organic production, including the availabil-ity of suffi cient funds for the transition to organic pro-duction (X3), and the adequacy of labour (X4)ś the third category involves farmers’ expected benefi ts from or-ganic production, including the opinion whether oror-ganic production can increase revenue (X5) and improve the environment (X6), as well as whether organic products are more safety and benefi cial to health (X7).

The analysis and interpretation of the results of regression

After the identifi cation of the dependent variable and in-dependent variables, the binary regression analysis with SPSS ń7.Ń was conducted adopting forced entry method

for the introduction of independent variables. The esti-mated results are shown in Table 4.

The overall effect of the model fi ts in good condition. The χ2 value of 7ř.32Ń and its signifi cance level of Ń.ŃŃŃ in chi-squared test suggest good fi tting. The small –2 Log ńikelihood value of ńń2.ř28 from the likelihood ratio test manifest the satisfactory fi tness. Both the high Cox & Snell R square value of Ń.433 and the high Nagelkerke R Square value of Ń.57ř indicate the soundness of the model. The χ2 value of ńŃ.76Ń and its signifi cance level of Ń.2ń6, well beyond the Ń.Ń5 threshold, in the Hosmer-Lemeshow test lead to the acceptance of the null hy-pothesis that no signifi cant differences exist between the observed data and forecasted data. The overall predict-ability of the model was 84.3%, showing the relipredict-ability of the regression model for accurately describing the reality. Therefore, the authors use this as the fi nal model.

According to the results of the model, the following conclusions were drawn. Żirstly, age has a positive ef-fect on farmers’ willingness to engage in organic farm-ing at 5% signifi cance level. →hen the other conditions remain unchanged, farmers are more likely to conduct organic farming when they get elder. The possible rea-son is that elder farmers in China pay more attention to health issues.

Secondly, risk preference demonstrates a positive in-fl uence at ń% signifi cance level. This shows that risky farmers prefer organic farming more than risk-averse ones, probably because they can bear higher input costs and greater market price fl uctuations in contrast to con-ventional farmers.

Thirdly, labour has a positive effect at 5% signifi -cance level, indicating that the more abundant labour is, the stronger farmers’ willingness to conduct organic production is. This is because organic farming prohibits chemical fertilisers and pesticides and requires manual weeding, and therefore it demands more labour than conventional farming. Hence labour-abundant family enjoy greater advantage.

Żourthly, expected income exhibits positive infl u-ence at ń% signifi cance level, suggesting that the higher farmers’ income from organic production is expected, the more willing farmers are to turn to organic produc-tion. This conclusion is consistent with the assumption that in business it is a rational choice to maximise one’s own economic interests. Żarmers will likewise pursue maximum profi ts when deciding on production methods and techniques.

Table 3. Źefi nition and assignment of variables

Tabela 3. Źefi nicja zmiennych wykorzystanych w modelu

↑ariables

Zmienne Źefi nitionŹefi nicja

X1 <4Ń = ń,4Ń–4ř = 2, 5Ń-6Ń = 3, >6Ń = 4

X2 6 ranks from preference to aversionŚ complete risk preference = ń, strong risk preference = 2, ordinary risk preference = 3, medium risk prefer-ence = 4, risk aversion = 5, complete risk aver-sion = 6

6 kategoriiŚ pełna skłonno ć do ryzyka = ń, silna skłonno ć do ryzyka = 2, zwykła skłonno ć do ry-zyka = 3, rednia skłonno ć do ryry-zyka = 4, awer-sja do ryzyka = 5, pełna awerawer-sja do ryzyka = 6

X3 yes =ń,no = Ń tak = ń,nie = Ń

X4 yes = ń,no = Ń tak = ń,nie = Ń

X5 yes = ń,no = Ń tak = ń,nie = Ń

X6 yes = ń,no = Ń tak = ń,nie = Ń

X7 yes = ń,no = Ń tak = ń,nie = Ń

Żifthly, environment has a positive effect at ńŃ% signifi cance level, showing that organic farmers see considerable environmental benefi ts and are more will-ing to switch to organic production. The reason may be that frequent incidents of environmental pollution have raised farmers’ awareness of environmental protection. The expected environmental benefi ts are one of the most important factors determining the selection of agricul-tural production methods.

CONCLUDING REMARKS AND SUGGESTIONS

The empirical results suggest that such factors as age, risk preferences, labour abundance, expected income and environment can signifi cantly affect farmers’

willingness to engage in organic agricultural production. The study showed the strong willingness of farmers to switch to organic agriculture, but restricted by limited government’s support and inadequate understanding of organic farming by farmers. To promote the rapid progress of organic agriculture in China, the following policy suggestions are recommendedŚ

ń) żovernment should strengthen policy support in organic farming. żovernment subsidises to organic farmers at all levels, reductions in the organic agricul-ture tax and certifi cation fees, and technical guidance for farmers will greatly improve farmers’ willingness to switch to organic production and upscale organic agricultural production. żovernment propaganda on laws, certifi cations and production processes concern-ing organic agriculture can enhance farmers’ awareness Table 4. źstimation result of logistic model

Tabela 4. źstymacja parametrów modelu regresji logistycznej

Specifi cation

→yszczególnienie →spółczynnikB

Std. źrr. Błąd standardowy

→ald Statystyka →alda

df Liczba stopni

swobody

Sig.

Istotno ć Iloraz szansźxp(B)

X1 Ń.588** Ń.264 4.ř57 ń Ń.Ń26 ń.8ŃŃ

X2 Ń.645*** Ń.ń6Ń ń6.282 ń Ń.ŃŃŃ ń.řŃ6

X3 Ń.263 Ń.527 Ń.24ř ń Ń.6ń8 ń.3Ńń

X4 ń.272** Ń.547 5.4Ń5 ń Ń.Ń2Ń 3.56ř

X5 2.76ř*** Ń.527 27.64ř ń Ń.ŃŃŃ ń5.ř5Ń

X6 2.ńń8* ń.2Ń5 3.Ń8ř ń Ń.Ń7ř 8.3ń4

X7 –3.ńń8 2.378 ń.7ńř ń Ń.ńřŃ Ń.Ń44

Constant

Stała –3.753 2.3ń3 2.633 ń Ń.ńŃ5 Ń.Ń23

Model as whole

Razem Chi-square (χ

2) = 7ř.32Ń.ń26, Sig = Ń.ŃŃŃ,

-2 Log likelihood = ńń2.ř28, Cox&Snell R Square = Ń.433,

Nagelkerke R Square = Ń.57ř, Hosmer-Lemeshow-square = ńŃ.76Ń, Sig = Ń.2ń6 Chi-kwadrat (χ2) = 7ř.32Ń.ń26,

p = Ń.ŃŃŃ,

-2 logarytm wiarygodno ci = ńń2.ř28, Coxa i Snella R kwadrat = Ń.433, Nagelkerke’a R-kwadrat = Ń.57ř,

Chi-kwadrat Hosmera-Lemeshowa = ńŃ.76Ń, p = Ń.2ń6

NoteŚ * indicates the Ń.ń signifi cance level, ** indicates the Ń.Ń5 signifi cance level, *** indicates the Ń.Ńń signifi cance levelś lack of * indicates the signifi cance level higher than p > Ń.ń.

SourceŚ own elaboration based on the questionnaire survey (n = ń4Ń).

Obja nienieŚ * oznacza istotno ć parametru na poziomie Ń,ńś ** oznacza istotno ć parametru na poziomie Ń,Ń5ś *** oznacza istotno ć parametru na poziomie Ń,Ńńś brak * oznacza, e ocena parametru jest statystycznie istotna na poziomie p > Ń,ń.

of organic farming and provide assistance in their decision-makingś

2) żovernment should encourage local transfer of surplus rural labour into organic agricultural produc-tion. Compared with conventional farming, organic farming is more labour-intensive, demanding higher quantity and quality of labour. Therefore, government can achieve the purpose of absorbing surplus rural la-bour, encouraging highly educated farmers to engage in organic farming, and creating more opportunities for organic farming development through improvement in farmers’ welfare standards, strengthening in rural social security systems and fi nancial services, and reinforce-ment in rural infrastructure constructionsś

3) żovernment should support the establishment of organic agricultural cooperatives. Rural cooperatives are consistent with the realities in the Chinese country-side, therefore effectively overcoming the weakness of decentralized individual farming, strengthening farm-ers’ negotiation power, reducing their transaction costs, raising their income, and facilitating their access to mar-ket information and technical services are vital to enable them to better react to market changes.

4) żovernment should expand cooperation with uni-versities and research institutions in organic R&Ź. Źue to the backwardness of organic farming techniques and research, organic farming centres can cooperate with universities to develop new technology and seeds, help-ing organic crops better resist various risks. Those cen-tres can also introduce new management and marketing practices to provide professional guidance and services for the stable and sustained development of organic farming.

REFERENCES

Anderson, J.B., Jolly, Ź.A., żreen, R. (2ŃŃ5). Źeterminants of farmer adoption of organic production methods in the fresh-market produce sector in CaliforniaŚ A logis-tic regression analysis. →estern Agricultural źconomics Association. 2ŃŃ5 Annual Meeting, July 6-8, 2ŃŃ5, San

Żrancisco, California. Retrieved from httpŚ//ageconsearch. umn.edu/handle/363ńř.

Burton, M., Rigby, Ź., Young, T. (ńřřř). Analysis of the de-terminants of adoption of organic horticultural techniques in the UK. J. Agric. źcon., 5Ń(ń)Ś 47-63.

Certifi cation and Accreditation Administration of People’s Republic of China (2Ńń4). China’s Żood and Agricultural Products Certifi cation Information System. BeijingŚ CNCA. Ceylan, I.C., Olhan, ź., Köksal, Ö. (2ŃńŃ). Źetermination of

the effective factors on organic olive cultivation decision. Afr. J. Agric. Res., 5(23), 3ń64-3ń68.

Chen, Y. S., Zhao, J. J. (2ŃŃř). An empirical analysis of fac-tors affecting organic vegetable farm production – Case Study of Beijing. J. Chin. Rural źcon., 7, 2Ń-3Ń.

Żairweather, J.R. (ńřřř). Understanding how farmers choose between organic and conventional productionŚ Results from New Zealand and policy implications. Agric. Human ↑alues ń6(ń), 5ń-63.

żenius, M., Pantzios, C.J., Tzouvelekas, ↑. (2ŃŃ6). Informa-tion acquisiInforma-tion and adopInforma-tion of organic farming practices. J. Agric. Resour. źcon. 3ń(ń), ř3-ńń3.

żreen Żood Źevelopment Center of China (2ŃńŃ). Statistical Yearbook żreen Żood of China. BeijingŚ CżŻŹC. Läpple, Ź., Kelley, H. (2Ńń3). Spatial dependence in the

adoption of organic drystock farming in Ireland. źur. Rev. Agric. źcon. Żirst published onlineŚ June 3Ń, 2Ńń4, ŹOIŚ ńŃ.ńŃř3/erae/jbuŃ24.

Läpple, Ź., van Rensburg, T. (2Ńńń). Adoption of organic farmingŚ Are there differences between early and late adoption? źcol. źcon., 7Ń(7), ń4Ń6-ń4ń4.

The →orld of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and źmerging Trends 2Ńń3 (2Ńń4). BonnŚ ŻIBL-IŻOAM.

→ang, Q. (2Ńń2). →ill farmers adopt organic farming tech-niques willingly? – Based in Beijing and Shandong Prov-ince. Survey of 25Ń farmers. J. Chin. Rural źcon., 2Ńń2 (2), řř-ńŃ3.

Zhang, ↓. (2Ńńń). źnvironmental benefi ts of organic agricul-ture – Żarmers cognitive perspective based on empirical analysis. J. Soft Science 25(7), ř2-ř5, ńŃń.

ROZWÓJ ROLNICTWA EKOLOGICZNEGO W CHINACH I CZYNNIKI

WP

Ł

YWAJ

Ą

CE NA ROLNICTWO EKOLOGICZNE

Streszczenie. Cel artykułu. Celem artykułu jest zidentyfi kowanie czynników determinujących podjęcie i rozwój

produk-cji ekologicznej w chi skich gospodarstwach rolnych oraz sformułowanie zalece dla polityki gospodarczej mającej na celu wsparcie tego systemu produkcji.

Materiał i metoda badań. Materiał ródłowy stanowiły wyniki bada ankietowych przeprowadzonych w ród rolników

podejmujących produkcję metodami ekologicznymi w małych gospodarstwach rolnych prowincji Jiangsu. → badaniach wyko-rzystano model binarnej regresji logistycznej.

Wnioski. Źowiedziono, e istotny wpływ na podejmowanie produkcji ekologicznej miałyŚ wiek rolników, skłonno ć do

ry-zyka, koszty pracy, spodziewane korzy ci i względy rodowiskowe. Źalszemu rozwojowi rolnictwa ekologicznego w Chinach mogłyby sprzyjać polityka wsparcia ze strony pa stwa adresowana do rolników podejmujących decyzję o konwersji na pro-dukcję ekologiczną oraz promowanie współpracy spółdzielni rolniczych i instytucji badawczych w celu doskonalenia technik produkcji ekologicznej.

Słowa kluczowe: rolnictwo ekologiczne, czynniki determinujące podjęcie i rozwój produkcji ekologicznej, polityka

gospodarcza

Zaakceptowano do druku – Accepted for print: 30.04.2015

Do cytowania – For citation