Large

barchanoid

dunes

in

the

Amazon

River

and

the

rock

record:

Implications

for

interpreting

large

river

systems

Renato

Paes

de Almeida

a,

b,

∗

,

Cristiano

Padalino Galeazzi

a,

Bernardo

Tavares Freitas

c,

Liliane Janikian

d,

Marco Ianniruberto

e,

André Marconato

a,

faInstitutodeGeociências,UniversidadedeSãoPaulo,RuadoLago,562,CidadeUniversitária,SãoPaulo,SP,CEP05508-900,Brazil

bInstitutodeEnergiaeAmbiente,UniversidadedeSãoPaulo,Av.Prof.LucianoGualberto,1289,CidadeUniversitária,SãoPaulo,SP,CEP05508-900,Brazil cFaculdadedeTecnologia,UniversidadeEstadualdeCampinas,R.PaschoalMarmo,1888,Limeira,SP,13484-332,Brazil

dUniversidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo,CampusBaixadaSantista,Av.AlmiranteSaldanhadaGama,89,PontadaPraia,Santos,SP,CEP11030-400,Brazil eUniversidadedeBrasília,InstitutodeGeociências,CampusUniversitárioDarcyRibeiro,71900-000Brasília,DF,Brazil

fUniversidadeFederaldeOuroPreto,EscoladeMinas,MorrodoCruzeiro,OuroPreto,MG,CEP35400-000,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Articlehistory:

Received2March2016

Receivedinrevisedform17July2016 Accepted20August2016

Availableonline10September2016 Editor:M.Frank

Keywords:

largerivers thalwegbedforms sedimentarystructures MultibeamEchosounder

The interpretation of large river deposits fromthe rock record ishampered bythe scarcity ofdirect observationsofactivelargeriversystems.Thatisparticularlytruefordeep-channelenvironments,where tens ofmeters deep flows dominate.Theseconditions are extremelydifferent fromwhat is foundin smaller systems, from whichcurrentfacies models werederived. MBES and shallow seismicsurveys in a selected area of the Upper Amazonas River in Northern Brazil revealed the presence of large compound barchanoid dunes along the channel thalweg. The dunes are characterized by V-shaped, concave-downstream crest lines and convex-up longitudinal profiles,hundreds of meters wide,up to 300minwavelengthandseveralmetershigh.Basedonthemorphologyofcompounddunes,expected preserved sedimentarystructuresarebroad,large-scale,low-angle,concaveupanddownstream cross-strata,passinglaterallyanddownstreamtoinclinedcosets.Examplesofsuchstructuresfromlargeriver deposits inthe rock recordare described intheSilurian SerraGrande Groupand theCretaceous São Sebastiãoand MarizalformationsinNortheasternBrazil,aswell asinTriassicHawkesburrySandstone in Southeastern Australia and the Plio–Pleistocene Içá Formation in the western Amazon. All these sedimentary structures are found near channel base surfaces and are somewhat coarser than the overlying fluvialdeposits, favoringtheinterpretation ofthalwegdepositional settings. The recognition oflargebarchanoiddunesasbedformsrestrictedtoriverthalwegsandprobablytolargeriversystems brings the possibility ofestablishingnew criteriafor theinterpretation of fluvialsystem scale inthe rockrecord.Sedimentarystructurescompatiblewiththemorphologicalcharacteristicsofthesebedforms seem to be relatively common inlarge river deposits, given theirinitial recognition infive different fluvialsuccessionsinBrazilandAustralia,potentiallyenablingsubstantialimprovementsinfaciesmodels forlargerivers.

2016ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved.

1. Introduction

Largeriversystems are definedon thebasis of drainagearea, channellength, aswell aswaterandsedimentdischarge (Hovius, 1998), andare the most importantagents ofsediment transport on Earth(e.g. Potter, 1978; Tandon and Sinha, 2007), accounting for approximately 35% of the sediments delivered to the oceans (Miall,2006).Althoughconcretecriteriafortherecognitionoflarge

*

Correspondingauthorat:InstitutodeGeociências,UniversidadedeSãoPaulo, RuadoLago,562,CidadeUniversitária,SãoPaulo,SP,CEP05508-080,Brazil.E-mailaddress:rpalmeid@usp.br(R.P.deAlmeida).

rivers in the rock record have been proposed (e.g. Miall, 2006; Fielding, 2007),detaileddescriptionsofsuch depositionalsystems are rare in the literature. Additionally, the scarcity of studies on sedimentary processes and products in large river channels hin-derstherecognitionandinterpretationofthesesystems,impacting regionalpaleogeographicalreconstructions,outcrop-scale sedimen-tologicalstudiesandhydrocarbonreservoirgeology.

In this way, establishing direct criteria for the recognition of large river deposits is of major importance. Approaches based on relating bedform size and cross-strata set thickness to river scale (e.g. Paola and Borgman, 1991; Leclair and Bridge, 2001; Leclair,2011)donotdirectlyleadtoreliableinterpretationofriver

size(e.g.Reesinketal.,2015).Ontheotherhand,difficultiesto dis-tinguishbetweenunitbarandlargedunedepositsbringadditional complexity to theinterpretation of riverscale based on the rock record. Theproblem isamplified by thescarcity of observational dataondeepchannel bedformmorphology,particularlyof Multi-beamEchosound (MBES) data, that could be used as a base for comparisonofbedformscaledistributionindifferentchannels,and potentiallyrevealdetailed3Dbedformmorphologiesthatcouldbe usedtorefineinterpretationsoftherockrecord.

The presenceof large-scale cross-strata in fluvial sedimentary successionshasbeenconsideredbyseveralauthorsasindicativeof largeriversystems(e.g.Miall,2006; Fielding,2007),andestimates ofchannel depth based on preserved thicknesses of dune cross-strataareoftenusedtoconstrainriversize(e.g.Luntetal.,2013; SambrookSmithetal.,2013,butseeReesinketal.,2015for alter-nativeviews).

Onemain problemwiththis approachis the difficulty in dis-tinguishing between deposits of large dunes, which thickness is a small fraction of the water depth (Paola and Borgman, 1991; LeclairandBridge, 2001), anddepositsof unit barforests, which originalthicknesses canbe similarto thewaterdepth(Sambrook Smithetal., 2006; Reesinkand Bridge, 2007). Additionally, com-pound dunes reported in severalactive large river channels(e.g. Parsonsetal.,2005; Carlingetal.,2000; AbrahamandPratt,2002) canformcross-stratifiedcosetslaterallyrelatedtolarge-scale fore-setsinthesamewayasunitbars.

Compounddunesarecommonfeaturesinthethalwegsof chan-nel systems, which include river channels and tidal inlets (e.g. Dalrymple,1984; Ashley,1990; Parsonsetal.,2005; Svensonetal., 2009; Lefebvre etal., 2011), whereas unit bars are common fea-turesinthethalwegofsmallriversystems,butuncommoninthe deeperpartsoflargeriverchannels(Ashworthetal.,2008).Inbig riversystemssuchastheBrahmaputraunit barscan beobserved throughsatelliteimageryandhavebeendescribedinbartops(e.g. Ashworthetal.,2000).

Morphologically,unit bars are usually regarded aslobate, non orquasi-periodic andrelatively unmodifiedforms (e.g. Sambrook Smith et al., 2006; Reesink and Bridge, 2007), whereas com-pounddunesareperiodic(Ashley,1990) andhavebeencommonly reported as straight and sinuous-crested (e.g. Dalrymple, 1984; Carling et al., 2000). More recently, barchanoid compound dune formshavebeenrecognized (e.g.Carling etal., 2000; Ernstsenet al.,2005; AbrahamandPratt,2002).

Fluvial barchanoid dunes are crescentic shaped bedforms (in plan-view) with arms pointing down-current, being morphologi-callysimilartoaeolianbarchanoiddunesandalsoascribedto lim-itedsediment supply(Carlingetal., 2000; Kleinhansetal.,2002). Fluvial barchanoid dunes are distinguished from 3D or undulat-ing dunes in having simple curved crestlines that are higher in the center and tapering toward the arm tips. Fluvialbarchanoid dunesarescarcely recordedintheliterature,probablyduetothe lackof3D bathymetric surveysofriverandcoastal channel thal-wegs. These bedforms were first described in an active fluvial environmentasisolated smallscale dunes (McCulloch andJanda, 1964). Onlyrecently they havebeen reportedagainin the deep-est areas of large channels in the Rhine (Carling et al., 2000; Kleinhans et al., 2002) and the Mississippi rivers (Abraham and Pratt, 2002), as well as in the smaller Allier River in France (Kleinhansetal.,2002).

Barchanoid forms may present a symmetric or asymmetric form, with an arm longer than the other (Svenson et al., 2009; Carling et al., 2000). In longitudinal sections, they are usually wedge-shaped, withstossangles of up to5◦ andlee angles that

canvary fromangle-of-repose tolow angles, below8◦, inwhich

casesuperposedsmallerdunesmayclimbdowntheleeface. Com-pound dunes in different environments are documented to have

smallerleeanglesthansmalldunes(DalrympleandRhodes,1995; Carlingetal.,2000).Thelengthtoheightratioisveryvariable, al-though maximumheightsare observedforgivenlengths(Ashley, 1990).

Compound barchanoiddunes up to 1 m high were described by Carlingetal. (2000) in theRhineRiver. The authorsproposed a modelfortheformationoftheobserved morphology, consider-ingthatthedunesgrowinheightduringtherisingriverstageand thendiminishduring steadyandfalling stages,when lee-side de-positionisincreasedbyrapidlymovingsecondarydunes.

Similarbarchanoidcompoundduneswereobservedinthe Mis-sissippiRiver byAbraham andPratt (2002).Althoughthe authors did not describe thebedforms indetail, MBES image and bathy-metricprofilesrevealduneheightsrangingfrom0.6to1.5 mand dunelengthsupto60m,withabundant superposedsmalldunes ontheirstosssides.

Compound dunesin tidalinletsystems,described by Ernstsen etal.(2005,2006)arecharacterized bycentralpartsofthecrests higherthanthearms.Superposedbedformsarelargerand coarser-grained,presentingsteeperleeanglesinthecentralcrest.Celerity ishigheronthesidesofthecompounddunes,whatcouldexplain theirbarchanoidshape.

Thepresentworkisaimedattheinvestigationondeep-channel bedsurveysinaselectedareaoftheAmazonRiver(Fig. 1),which reveals that large, up to 12 m tall, barchanoid dunes are con-spicuous features in the thalweg of thislarge river. This type of bedform is not found in shallow deposits in the region and is not described forsmall riversystemselsewhere.The main objec-tive was toprovidenewcriteriafortherecognitionof largeriver thalwegdeposits,presentingdetaileddescriptionandamodelfor theinternalstructure ofbarchanoiddunes.Additionally,examples ofpreservedstructuresfromthe rockrecord arepresented, illus-trating theimportanceofestablishing criteriatodistinguishlarge compounddunesfromunitbardeposits(seebelow).

2. Investigatedarea

The fluvial systemsof theAmazon standout asimportant el-ementsinEarthsurface dynamics,contributingwithasignificant proportionoftheglobalsedimentflux totheoceans. Largerivers with catchments in the Andes, such as the Solimões–Amazonas andMadeira,areresponsibleforthebulkofthesedimenttransport in theregion. Theserivers, together withrivers withlarge water dischargebutlowersediment flux,suchastheNegro,Tapajósand Xingu, exertimportantcontrolsonthedistributionofanimaland plantspeciesintheregion.

The investigated area in the Amazon River is located in the main channel, northofthe CareiroIsland,33 km downstream of the confluence between the Solimões and the Negro rivers. The CareiroIslandseparatesthemainchannel fromalocalanabranch (Paraná do Careiro, Fig. 1), which has an average minimum low stage discharge of 5100 m3

/

s and average maximum high stagedischargeof25,900 m3

/

s,accordingtotheBrazilianNationalWa-ter Agency (AGÊNCIA NACIONAL DE ÁGUAS – ANA). In the main channel minimumdischargesoccur betweenOctoberand Decem-ber,withaverageminimumannualdischargeof74,100 m3

/

ssince1977,varying between51,500 m3

/

sand102,400 m3/

s.Maximumdischarges occur between May and July, withaverage maximum annualdischarge of178,000 m3

/

s,varyingbetween121,400 m3/

sand233,000 m3

/

s.Dischargevariationinoneyearrangesfrom50%of peak discharge (1980 record) to 70% of peak discharge (2009 record). Total suspended sediment discharge at the Manacapuru gaugestation,approximately130 kmupstreamofthestudiedarea, isaround400 Mt yr−1 (FilizolaandGuyot,2009).

Fig. 1.Surveyed area (white rectangle) in the Amazon River.

(Nordin et al., 1980; Mertes and Meade, 1985; Strasser, 2008), withaveragegrain-sizevaryingbetween0.25and0.40 mm. Depth-related grain-size variation at one section in Óbidos (Strasser, 2008) presents greater magnitude, witha medianof 0.16mm at nearly40mdepthandof0.57atnearly60mdepth.Inthe inves-tigatedarea,previousstudyofbedloadgrain-sizeshowsamedian of 0.40 mm, with60% of the grainsbetween 0.30 and 0.50 mm (Strasser, 2008). Inthestudiedreach theAmazonRiver, themain channelhasa localmaximumdepthof78 m.Thethalweg is ap-proximately800mwide,withdepthsbelow50m,flankedtothe south by the submerged lateral extension of the Careiro Island, dippingnearly3.5◦.Tothenorth,themainthalwegisboundedby

asteep erosionalsurfaceon Cretaceoussedimentary rocks.A few isolatedpinnaclesofthesameCretaceousrocksoccurinthemain channel.

3. Methods

Bathymetric and seismic profiling systems were used to de-scribe channel morphology and shallow stratigraphy. Swath bathymetry sonar systems have been used in the last decades to map and study seafloormorphology, asdescribed in the pio-neer work of Hughes-Clarke et al. (1996) and, more recently, to remotelyestimateseafloorphysicalproperties(FonsecaandMayer, 2007). Due to the centimetric depth resolution and overall sub-metricspatialaccuracy,high-frequencysonarshavebeenalsoused to study 3D morphological features ofactive river channels (e.g. Parsonsetal.,2005).

Bedformmorphologyandhigh-resolutionbathymetryinareach oftheUpperAmazonaswasstudiedwithMultibeamEchosounder (Teledyne-ResonSeabat 7101system),operatingatafrequencyof 240 kHz, with511 beamachieving a resolution of12,5 mm. In-ternalstructureanddistancetochannel bedrockwereinterpreted from seismic images,obtained with a Meridata sub-bottom pro-filing systemusinga Boomer profileroperating inthe 0.7–2 kHz frequencyband,resultinginaresolutionofabout0.5m.

Bedmaterial was collected in12 sites during the dryseason, 3 months after the MBES survey, with a 10 kg Van Veen grab sampler.GrainsizeanalyseswereperformedwithaMalvern Mas-tersizer2000(fractionssmallerthan1mm). Fractionswithlarger grain-sizewereestimatedbasedonnormalizedweightproportion inrelationtothewholesample.

4. Results

4.1. Morphologyofcompoundbarchanoiddunes

Deep channel areas in the investigated reach, from 42 m to 66 m belowhighstage waterlevel,are dominatedby large-scale compound barchanoid dunes, contrasting with shallower areas, 5 to 32 mdeep,wherestraight- tosinuous-crested simpledunes dominate (Fig. 2). In a transitional domain, from 34 to 57 m

depth, following the slope of the subaqueous extension of the CareiroIsland bar, large-scale,straight-crested, flow-oblique com-pound dunesare found. Large-scalecompound barchanoid dunes are characterized by arched to V-shaped crestlines, with angles from 70◦ to 106◦, onaverage, betweenthe nearly straight arms.

Despite the apparent lateral continuity of crestlines into straight to lobate dunes, those actually form separate trains with differ-entwavelengths,onlyrandomlyconnectedtothebarchanoidcrests (Fig. 2). Distances betweenarm tips of each dune vary between 84–156 m(average of136m) forthesmalltrainand270–471 m (average384m)forthelargetrain.Crestlinesdonotsystematically varyinheightbetweencentralandexternalpartsofeachbedform, butseemtofollowtheinclinationofthesurfaceonwhichthe bed-formsmigrate.Barchanoidduneswavelengthhaslittlevariationon each individualdunetrain (standarddeviation/meanfrom0.20 to 0.36),withameanof150mforthelargerdunestrainand61m forthesmallestdunestrain.Duneheightfollowsthesamepattern, withmeanduneheightofapproximately5mforthelargerdune train andof 2.2 m forthe smaller one. The smallest barchanoid dune is 0.6 m tall, whereas the larger is 8.2 m tall. The dunes areasymmetricinlongitudinalprofiles,withtheproportionof lee-side lengthtototallengthaveraging35%.Stossanglesrangefrom 2.2◦ to8.0◦,witha meanof4.4◦,and70% ofthevaluesbetween

2.9◦ and6.2◦.Leeangles are stronglydependent onthe position

oftheconsideredlongitudinalprofileofagivenbarchanoiddune: while steeperprofiles are foundatthe centralpartsofindividual barchanoids,verylowdippingsurfaces(afewdegrees)characterize thedowncurrentarmsofeachbarchanoiddune.Interestingly,even the centralparts rarelyshow angle-of-reposeleefaces, withonly 10%ofthedunesshowingleefacedipssteeperthan20◦.Leefaces

areoftenconvexupward,displayingplanar,higheranglepartsnear thebaseoftheleeside,andlowanglesurfacesdominatingthe up-per,convexpartofleefaces.Themeandipvalueforplanar,steeper partsoftheleefacesis11.8◦,with50%ofthevaluesbetween7.4◦

and16.2◦.Thesteeperlowerpartoftheleefacerepresents20%to

94%oftheduneheight,averaging61%.

Superposed bedforms are often found on the stoss of the barchanoiddunes.Thoseare morefrequentandhigherinthe ex-ternal arms of each barchanoid dune, commonly showing 0.1 to 0.5 m inheight and 2to 10 m inwavelength. Superposeddune heightstendtobe largernearthecrestofhostbarchanoiddunes. Superposeddunes arealso foundon theleefaces, mainlyon the armsofhostbarchanoiddunes.

Fig. 2.MultibeamEchosounder(MBES)3Dbathymetricmodelofthestudiedreachshowingdistributionofdifferenttypesofbedformsinthestudiedarea.Locationofseismic surveyisshownintheA–A′ line.Locationofgrainsizeanalysissamplesareplotted.Symbolsrepresentmaximumgrainsizesobservedatspecifiedlocations:triangles–

granule;diamonds–coarsesand;circles–mediumsand.Notecorrelationofmaximumgrainsizewithdepth.

Fig. 3.A)Cumulativegrain-sizedistributionsofsamplesfromthalwegbarchanoid dunesandothertypesofbedformsintheinvestigatedarea.B)Correlationbetween averagegrain-sizeofindividualsamplesandwaterdepthintheinvestigatedarea. Notethatgrainsizefromsedimentstarvedthalwegdomainwasnotconsideredfor theconstructionoftheregressionline.

SubsurfaceBoomer images reveal that atsome points several compounddunesarestacked,mostprobablyformingcosets, sum-ming up at least 18 m of sediments on top of the interpreted Cretaceousrocks(Fig. 4),whereaselsewhereonlythethicknessof oneindividualdunecanberecognized.Successivelargecompound dunesclimbevidenceacleardifferencefromtruebarchans migrat-ingonbedrockorpebblelags(e.g.Kleinhansetal.,2002).

4.2. Internalstructureandfaciesmodelofcompoundbarchanoiddunes

The characteristic morphology of the large compound dunes which dominate the thalweg of the investigated area, integrated toshallowsubsurfaceseismicimages,provideelementsforthe in-terpretationofthesedimentarystructuresthatwouldbepreserved insimilardepositsintherockrecord.

Considering that these thalweg bedformsmay not leave long term deposits where erosion rate equals deposition rate during bedformmigration,theirpreservationrequireseithergradualshift or abandonmentof the main channel, with progressiveburial of the thalweg bedforms by channel fill orbar migration. The long termpreservationofthesebedformswouldbecontrolledbyscour depthvariation (Paola andBorgman,1991), leadingto the poten-tialerosionoftheupperpartofthestructure.

Inthisway,low angletangential lee-faces inthecentralparts ofthebarchanoidduneswouldbepreservedaslow-angleforesets dippingparalleltothecurrentdirection,whereastowardsthedune arms, preserved foresetorientations would tend to shifttowards the central part of the dune,leading to a low angle concave up anddownstreamcross-stratificationpattern.Theabundanceof su-perimposedsmallerbedformsonthebarchanoiddunearmswould resultincompoundcross-strata.

Therefore, the observed morphology would result in two dif-ferenttypesofcross-stratasetsinthesedimentaryrecord,namely large-scaleforesetsandinclinedcosets,reflectingdifferentprofiles inthesamebedform(Fig. 5A):

Fig. 4.A)Shallowboomersub-bottomprofile(A–A′,seeFig. 2forlocation)paralleltoriverflow.ReflectorsascribedtotheCretaceoussubstrate(blackarrows)layseveral

metersbelowthesurfaceofthestudiedbarchanoiddunes.B)Seismicprofileinterpretation.ReflectorsbetweentheCretaceoussubstrateandtheriverbedareinterpretedas sub-horizontaltolow-angledippingcross-stratasetboundingsurfaces,aswellaslocalpreservedcross-strata.

in some cases withinclined cosets showing smaller individ-ual cross-stratasets recordingthedown-climbingsuperposed bedforms(Fig. 5A,A–A′ andB–B′sections).

(2) Longitudinalprofilesofthelargebarchanoiddunearmswould bedominatedbyinclinedcosetswithinternalcross-stratasets afew decimetersthick (Fig. 5A,C–C′section).Cross-strataset

boundingsurfaceswouldbeinclined afewdegrees,andtheir dip directionwould be controlled by the localorientation of the lee face of the host bedform and the angle of climb of the smallerbedforms(Almeidaetal., 2016). Thicknessofthe whole coset wouldbe nearly the sameof therelatedforeset atthecentralpartofthehostbedform.

(3) Profiles orthogonal to the current direction would show a broad (hundreds of meters wide) trough cross-stratification, withthesteeper partoftheforesetsintheinnertrough tran-sitioning outward and upward to lower angle foresets and inclinedcosets(Fig. 5A,E–E′section).Dipdirections

measure-ments of hostduneforesets show adispersion ofmore than 120◦, with higher angles in the direction of flow and lower

anglesinobliquedirections.

Lateralvariationsbetweenbothtypesofpreservedcross-strata are expected in profiles oblique to the current direction, there-fore cutting through both the central and lateral parts of the bedform (e.g. Fig. 5A, D–D′ section). Additionally, an increase in

thefrequency ofsuperposed smallerbedform is expected during low stages, whereas a dominance of steeper foreset is expected athighstages,potentially leadingto temporalvariations between avalancheforesetsanddown-climbingcosetobservablein longitu-dinalprofiles.

Potential preservation of large barchanoid dunes in the rock recordcanbe expectedwherethesethalwegelements areburied beneath migrating bars or abandoned channel fills. Climbing of barchanoiddunesisstronglysuggestedbytheseismicprofilefrom bar fronts, where downstream migrating barchanoid dunes stack formingtens of meters highmacroforms(Fig. 4). Additionally, in most of the Solimões and the Amazon rivers, mid-channel and bank-attachedbars frequentlygrowormigrateover thethalwegs, thus potentially covering the barchanoid dunes. Finally, several kilometerslongabandonedchannelreachesinbothriverspointto thepotentiallongtermpreservation ofcomplete channelfill suc-cessions,withlargebarchanoiddunesatthebottom.

4.2.1. Criteriaforthedistinctionoflargecompounddunefromunitbar

deposits

Unitbarshavebeeninterpretedfromsimilarlarge-scale cross-strata, and the distinction of large compound dunes and unit bar deposits in the rock record is not straightforward. Unit bars may have a similar architecture to large compound dunes, de-finedby superposedsmaller bedformsclimbing upthestoss,and by variable geometries on the lee side of the host bedform, in-cluding large simple, often angle of repose, lee faces and local lowanglesurfaceswithsuperposeddownclimbingbedforms. Cur-rentknowledge about theoccurrence, depositional processes, in-ternalstructuresandpreservationofbothtypesofbedformsisnot enough to establish universal criteria for the discrimination be-tweenunit barandlarge compound dunedeposits.Nevertheless, some striking morphological differences may be used to distin-guishpreserveddepositsofunitbarsfromtheheredescribedlarge compound barchanoid dunes. Unit bars are usually lobate, con-trasting with barchanoid large dunes. The position of the large compound barchanoid dunes in the thalweg of the main chan-nel is also a marked characteristic, often related to distinctively coarsergrainedsedimentthan theothersub-environmentsinthe samesystem. Additionally, whereas dunes are periodic bedforms, unit bars are quasi- ornon-periodic bedforms(e.g. Smith, 1978;

SambrookSmithetal.,2006)withlengthsproportionaltotheflow widthandheightscomparabletobankfulldepth(e.g.Reesinkand Bridge,2007).

Inthisway,largebarchanoiddunescan bedistinguished from unitbardepositsintherockrecordbasedonthefollowingcriteria:

(1) Large barchanoiddunes occur in thalwegs andtherefore are preservedatthebaseofchannel elements,coveringerosional surfacesandfrequentlybeingcoarsergrainedthanthe overly-ingsuccession.Unitbarswithlarge-scaleforesetsarecommon in shallow parts of the fluvial system (e.g. Ashworth et al., 2008)andhavenotbeenobservedonlargeriverthalwegs. (2) Large barchanoid dunes result in cross-strata slightly

con-cave upandslightlyto stronglyconcave downstream(locally V-shaped), with a tendency to preserve large-scale simple foresetson thecentral partof thestructure passing,towards theexternalpartofthestructure,tolowangleinclinedcosets composed ofsmaller scale cross-stratasets (Fig. 5B). Tempo-ralvariations betweensimpleforesetsandinclinedcosetsare alsoexpected. Althoughlocalpreservationofconcaveunitbar foresetsispossible,thecommonlobategeometryofunitbars impliesa morefrequentpreservationofapparently tabularor evenconvexupanddownstreamcross-stratification.

The periodicity of the large barchanoid dunes contrasts with unit bars, and the presence of local climbing surfaces between large-scale cross-strata can be used as criteriato distinguish be-tweendunesandunitbars.

5. Validationoffaciesmodelfromthegeologicalrecord

5.1. CretaceousfluvialdepositsintheTucanoBasin

Early Cretaceous fluvial successions in the Tucano Basin, São SebastiãoandMarizalformations,areinterpretedastherecord of aregionalscalefluvialsysteminfillingadeepriftbasinduringthe initialstagesoftheopeningoftheSouthAtlantic(e.g.Costaetal., 2007; Figueiredo,2013; Freitas,2014; Figueiredoetal.,2016).

Severalmetersthick inclinedcosetsarethedominantelement in the architecture of both units, and the preservation of out-sizedcross-stratasetsupto5mthickhavebeenpreviously inter-pretedmostlyasunitbardeposits(Figueiredo,2013; Freitas,2014; Figueiredoetal.,2016; Almeidaetal.,2016),withlocalsuggestion ofcompounddunes(Figueiredo,2013).

Some oftheselarge-scale cross-strata sets andinclined cosets match the here proposed criteria for the interpretation of large compoundbarchanoiddunedeposits,indicatingthatatleastsome ofthe depositspreviously interpreted asunitbar products might reflectbedformsdevelopedinchannelthalwegsmuchdeeperthan thepreservedthicknessofindividualbedforms.

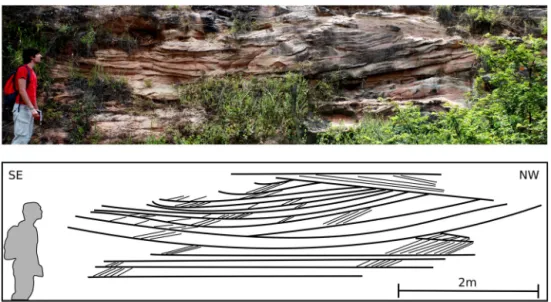

IntheSãoSebastiãoFormation,localcosetswithtrough-shaped setboundingsurfacesindicateconcave-downstreamleefacesofa larger host bedform with down-climbing smaller dunes (Fig. 6). Largecosetsare up to 5 m thickandthe internal inclined cross-strata sets are15 to35 cm thick, suggestingseveralmeters high compound dunes. The position of such cosets near the base of channelelements corroboratestheinterpretationofthalweg com-poundbarchanoiddunes.

Fig. 6.Trough-shapedcross-stratasetboundingsurfacesintheSãoSebastiãoFormationinterpretedasdepositsoflargebarchanoiddunes.EarlyCretaceous,TucanoBasin, NE-Brazil.

Fig. 7.Large-scale cross-strata and laterally related inclined cross-strata sets in the Marizal Formation. Early Cretaceous, Tucano Basin, NE-Brazil.

facies, bar accretion elements and finally aggradational bar tops (Freitas,2014; Figueiredoetal.,2016; Almeidaetal.,2016).

At several locations, up to 5 m thick cross-strata sets, with 15◦ to 25◦ dipping foresets ingranule-bearing coarse sandstone,

arefoundnearthebaseoftheinterpretedchannelfillsuccession, passinglaterallytocross-stratacosetscomposedofdecimetric tab-ularcross-strata sets(Fig. 7). The positionator nearthebase of fining-upward cycles,ontop ofmajor erosionalsurfaces,andthe compatible structure to the here proposed facies model strongly suggest theseare the depositsof large-scale compound dunesin fluvialthalwegs.

5.2. SilurianfluvialdepositsintheParnaíbaBasin

Sandstone-dominated fluvial successions of the Serra Grande Group (Silurian, Parnaíba Basin, northeastern Brazil) were de-posited in a broad sag basin covering different elements of the LateNeoproterozoicBrasiliano orogeny(e.g.Pedreiraetal., 2003). The lowermost unit in the Serra Grande Group (Ipu Formation) as exposed in the northeastern part of the basin, is dominated by erosional-based 10 to 15 m thick fining-upward sandstone successions, capped by centimetric to decimetric mudstone de-posits (Fig. 8). Near the lower erosionalsurfaces, abundant 1 to 2.5mthicktrough cross-stratapasslaterallytoandfrom trough-shaped cross-strata setscomposed of 0.1to 0.35m thick tabular andtrough cross-strata (Fig. 8). Local superposition oftwo

indi-vidual large-scale cross-strata sets suggests periodical bedforms. Finer-grained (mediumtofine sandstone)laterallycontinuous in-clined cosetsof trough andtabular cross-strata form meter-scale elements covering thelower succession dominated by large-scale cross-strata sets. Both the position and the overall structure of these lower successions are compatible to the here proposed modelforlarge-scalebarchanoidcompounddunedeposits.

5.3. TriassicHawkesburySandstone,southeasternAustralia

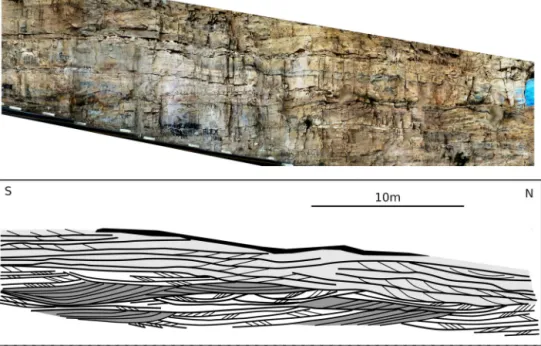

The Hawkesbury Sandstone, deposited during the Triassic in the Sydney Basin and currently exposed in southeastern Aus-tralia, isinterpreted as the geological record ofa large-scale flu-vialsystem(e.g.Miall,2006; Fielding,2007).Thisinterpretationis mainly ascribed to the commonoccurrence of large-scale (up to 8 m thick, commonly 2 to 3 m thick) cross-strata within cross-stratacoset-dominated,mediumtocoarse-grained,sandstone suc-cessions (ConaghanandJones, 1975; RustandJones, 1987; Miall andJones,2003),superblyexposedoncoastalcliffsnearSydney.

Fig. 8.Large-scaletroughcross-strataandtrough-shapedcross-stratasetsintheSerraGrandeFormationinterpretedasdepositsoflargebarchanoiddunes.Silurian,Paraíba Basin,NE-Brazil.

Fig. 9.ExamplesfromtheHawkesburySandstone.A)Concavedownstreamlarge-scalecross-strata.Notethelateraltransitionfromlarge-scalecross-stratatocompound cross-stratification(redarrow).B)andC)Large-scalecross-stratadisplayingsmallerpreservedcross-stratificationsfromsuperposedbedformsmigratingnearthehostdune brinkpoint.

sedimentarystructures,ConaghanandJones (1975)envisagedthe occurrence of lunate or catenary forms in the thalwegs of the BrahmaputraRiver,inferringthesebedformgeometriesfrom “pat-ternsofsurfaceturbulenceabovethecompletelysubmerged flood-stagesandwaves”.

The occurrenceof large-scale tangential foresets, slightly con-cave up and slightly to strongly concave downstream (Fig. 9A), above channel baseerosional surfaces,point to an origin on mi-grating barchanoiddunes. Large-scaleforesets laterally relatedto cosetsandseparatedby large-scalecross-strataset bounding sur-facesindicateperiodicityoftheformativebedforms,corroborating theaboveinterpretation.

Lateraltransitions betweenlarge-scale foresetsand cosetscan be observed both in plan view and in vertical sections (Fig. 9A, red arrow, and C), reflecting spatial relationships between these twotypesofcross-stratacharacteristicofbarchanoiddunes.Local preservationofbedformtopssuggesttransitionsfromsuperposed bedform cross-strata to large-scale foresets at the brink point of compounddunes(Fig. 9C).

5.4. NeogenedepositsinthewesternBrazilianAmazon

Exposures of Plio–Pleistocenesand-dominatedsuccessions, in-cluding the Içá Formation and possibly younger Pleistocene de-posits are found at the margins of the Solimões River, in the western Brazilian Amazon(e.g. Rossettietal., 2005; Horbe etal., 2013). These comprise more than 15 m thick fining-upward cy-cles,beginning aterosionalsurfacescutting throughtheMiocene to Pliocene Solimões Formation,and composed of lower granule andintraclast-richcoarse sandstone, passing upward to veryfine cross-laminatedsandstone,heterolithicbedsandmudstonelenses. Thesuccession isdominatedby0.6to1.5mthickinclined cosets oftroughandtabular cross-strata,withisolated meter-scalethick troughcross-strataoccurringlocally,overlyingmajorerosional sur-faces(Fig. 10).

super-Fig. 10.Large-scale,concave-upcross-strataadjacenttoinclinedcosets,aboveandbelow,intheIçáFormation,interpretedasdepositsoflargebarchanoiddunes.Neogene, WesternAmazon,Brazil.

posedbedforms.The relativesmallsizeofthesestructures, upto 1 mthick and3to5 mwide,differsfromwhatisexpectedtobe therecordoflarge-scalebarchanoiddunesobservedinthemodern thalweg,suggestingasmallerchannel.

6. Discussion

Theparticularmorphologyoflargebarchanoiddunes,their oc-currence exclusively on the thalweg of major channels and the distinctive characteristics of the examples from the rock record pointtomarkeddifferencesfromotherlarge-scalecross-strata sys-temsdescribedintheliterature.Thiscouldjustifythedefinitionof anewarchitecturalelement,helpingthedescriptionand interpre-tationofChannelThalwegBedforms.

The observed dune morphology seems to indicate reworking of large barchanoid dunes by the migration of superposed bed-forms,withthe supposedlyoriginal angle-of reposelee sides be-ingprogressivelymodifiedbylateraccumulationofsediment (e.g. KostaschukandVillard,1996)derived fromsmallerdunes migrat-ing up the stoss of the larger bedform (e.g. Reesinkand Bridge, 2007). In thisway, low angle lees wouldresult fromchanges in flowconditions,when thelarger bedformsceasetobe active, al-thoughadditionaldataonactualflowvelocitiesandtemporal evo-lution of these large barchanoid dunes is necessary to elucidate thispoint.

Recognizingthedepositsoflargecompoundbarchanoiddunes in the rock record can be usefulin the characterization of large riverdeposits.Thesebedformshavebeen reportedinlargerivers thalwegs in the Rhine and the Mississippi rivers (Carling et al., 2000; Abraham and Pratt, 2002). In the presentstudy, the char-acterization ofthemorphology andinterpreted internal structure oflargecompound barchanoiddunes inthethalweg ofthe Ama-zonRiverenabledtheinterpretationofsimilardepositsintherock record,bringing the possibilityofinterpretationof deepchannels that could otherwise be mistaken for unit bar deposits of much shallowerchannels, since unit bars tendto reach thewaterlevel whereas thalwegdunes are oneorder ofmagnitudesmallerthan theformativewaterflowdepth.

In all above presented examples of possible barchanoid com-pound dunes from the rock record, the deposits are found at or near the base of fining-upward elements which are three to fivetimesthickerthantheindividuallarge-scalecross-strata.Such scale relationship corroborates the interpretation of those cross-stratifieddepositsasproductsofthemigrationofdunesinsteadof unitbars.

Even smaller barchanoid compound dunes, in the range of a few tensofmeterswideandapproximatelyonemeterhigh, such asthose found inthe RhineandtheMississippi rivers andthose interpreted for the Plio–PleistoceneofWestern Amazon, seem to be absent in small rivers, andcan be used to interpret regional scale fluvial systems. Larger structuressuch as those recognized inthe ParnaíbaandTucanobasins, aswell asin theHawkesbury Sandstone,indicategreaterwaterdepths.

The apparent relationship between large rivers and thalweg barchanoid dunesis probablydue tothe combined effectoftwo factors: (i)greater localshearstressesindeepcurrentscompared toshallowerones,resultingingreatertransportefficiencyand con-sequently leading to relatively starved sediment domains in the deepest thalwegs; (ii) lack of water-depth control over bedform height (due to thedeep watercolumn),enabling hugevariations in dune crest height along crest lines, and consequently causing such mobilitydifferencesthat thegreater celerityof thesmallest parts resultsintheformationofnearly currentparallelarms dis-ruptedfromthecentralpartofthesebedforms(e.g.Ernstsenetal., 2005).

Although no method for the estimation of formative water depthbasedonpreservedbarchanoidcompounddunecross-strata set thickness can be proposed atthe moment, future studies on modernlargeriverscanbeusedtobuildadatabasethatcould elu-cidate such matter,considering variations onflow conditionsand bedform grain-size in different systems. Discriminating thalweg bedformdepositsandtheirpropertiesintherockrecordwill prob-ablyleadtobettercorrelationwithwater-depththanthatachieved instudiesconsidering alltypesofdunes(e.g.Paola andBorgman, 1991; Leclair and Bridge, 2001; Jerolmack and Mohrig, 2005; Bartholdyetal.,2005).

Fornow,acomparisonofthemorphologyofthalwegbedforms in Amazon rivers with the preserved structures in Neogene de-posits in the Western Amazon can be useful in the qualitative determination oftherelative sizeoffluvial systemsinthe region andtheirspatialandtemporaldistributions,withimportant impli-cations formodels considering the role oflarge river systems in theevolutionofthebiodiversityintheregion.

7. Conclusions

havebeenrecognizedonlyinthalwegsoflargerivers,suchasthe Rhineandthe Mississippi.Therefore,theinterpretation ofsimilar bedformsfromtherockrecordbringsthepossibilityofrecognizing ancientlargeriverdeposits.

The two trainsof barchanoiddunes described in the Amazon Riverarerestrictedtothedeepestareasofthechannel.Thedunes arecharacterizedby V-shapedcrest linesandconvexlongitudinal profiles. Thesedunes present133 to 471m between the tipsof eacharm;meanwavelengthof150mforthelargesttrain,andof 61mforthesmallest;meanduneheightrespectivelyof5mand 2.2m.Leesideanglesarecharacteristicallylow:afewdegreeson thedunearmsandlessthan20◦degreesatthedunecenter.Lower

leeangles are relatedto superimposition by secondary dunes on thestossside.

Basedon morphologyofcompound dunes,expected sedimen-tarystructuresresultingfromthepreservationoflargebarchanoid compounddunedepositsarebroad,large-scale,low-angle,concave upanddownstreamcross-strata,passinglaterallyanddownstream toinclinedcosets.Examplesofsuchstructuresfromlargeriver de-positsin the rock record are found in the Silurian Serra Grande GroupandtheCretaceousSãoSebastiãoandMarizalformationsin NortheasternBrazil, aswell asin theTriassicHawkesburry Sand-stone inSoutheastern Australia andthe Plio–PleistoceneIçá For-mationintheAmazon. Allthesedepositsarefound nearchannel basesurfacesandaresomewhatcoarserthantheoverlyingfluvial deposits,favoringtheinterpretationofathalwegdepositional set-ting.

The recognition of large barchanoid dunes as bedforms re-stricted to river thalwegs and probably to large river systems brings the possibility of establishing new criteria for the inter-pretationof fluvial systemscale in the rock record. Sedimentary structures compatible with the morphological characteristics of thesebedforms seemto be relatively commonin large river de-posits,giventheirinitialrecognitioninfivedifferentfluvial succes-sionsinBrazilandAustralia.Inthisway,furtherstudiesonactive barchanoid dunes and their deposits are neededto test the hy-pothesisof their relationship withriver scale, andmay resultin substantialimprovementsinfaciesmodelsforlargerivers.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the careful assessment of the manuscript by the EPSL Editor Martin Frank and thoughtful re-view andsuggestions fromAndrew Miall and an anonymous re-viewer.Sub-bottomseismicprofilingwasprovidedbySALTSeaand LimnoTechnology.Thisresearch wasfundedbytheSãoPaulo Re-search Foundation (FAPESP)through scholarships #2010/51103-6, #2010/51559-0, #2013/02114-3, #2014/09800-2 and Research Grants #2013/01825-3, #2014/16739-8, #12/50260-6 (FAPESP-NSF-NASABiota/DimensionsofBiodiversity).WealsothankCAPES (PROEX-558/2011)andPRFH-PETROBRASforstudentscholarships, and CNPq for researcher scholarships (302905/2015-4, 301775/ 2012-5). This study is a NAP GEO-SEDEX contribution, with the institutionalsupportoftheUniversityofSãoPaulo(PrPesq).

References

Abraham,D.,Pratt,T.,2002.Quantificationofbed-loadtransportontheupper Mis-sissippiRiverusingmultibeamsurveydataandtraditionalmethods.USArmy EngineerResearchandDevelopmentCenter(ERDC)/CostalandHydraulics Lab-oratory(CHL),CoastalandHydraulicsEngineeringTechnicalNote(CHETN),9 p. http://chl.wes.army.mil/library/publications/chetn.

AGÊNCIANACIONALDEÁGUAS(Brazil)(ANA).HidroWeb:sistemasdeinformações hidrológicas.At: http://hidroweb.ana.gov.br/HidroWeb. AccessedAugust 23rd, 2015.

Almeida,R.P., Freitas,B.T., Turra,B.B.,Figueiredo,F.T.,Marconato,A.,Janikian,L., 2016.Reconstructingfluvialbarsurfacesfromcompoundcross-strataandthe interpretationofbaraccretiondirectioninlargeriverdeposits.Sedimentology. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/sed.12230.

Ashley,G.M.,1990.Classificationoflarge-scalesubaqueousbedforms:anewlookat anoldproblem.J.Sediment.Petrol. 60,160–172.

Ashworth,P.J.,Best,J.L.,Roden,J.E.,Bristow,C.S.,Klaassen,G.J.,2000.Morphological evolutionand dynamicsofalarge,sandbraid-bar,JamunaRiver,Bangladesh. Sedimentology 47,533–555.

Ashworth,P.J.,Amsler,M.L.,Best,J.L.,Hardy,R.J.,Lane,S.N.,Nicholas,A.P.,Orfeo,O., Parker,N.O.,Parsons,D.R.,Reesink,A.J.H.,SambrookSmith,G.H.,Simmons,S., Szupiany,R.N.,2008.Dounitbarsco-existwithdunesinbigsand-bedbraided rivers?In:BritishSocietyforGeomorphology(BSG)AnnualConference. Univer-sityofExeter.

Bartholdy,J.,Flemming,B.W.,Bartholomä,A.,Ernstsen,V.B.,2005.Flowandgrain sizecontrolofdepth-independentsimplesubaqueousdunes.J.Geophys.Res., EarthSurf. 110,F04S16,1–12.

Carling,P.A.,Gölz,E.,Orr,H.G.,Radecki-Pawlik,A.,2000.Themorphodynamicsof fluvialsanddunesintheRiverRhine,nearMainz,Germany.I. Sedimentology andmorphology.Sedimentology 47,227–252.

Conaghan,P.J.,Jones,J.G.,1975.TheHawkesburySandstoneandtheBrahmaputra: adepositionalmodelforcontinental sheetsandstones.J.Geol.Soc. Aust. 22, 275–283.

Costa,I.P.,Milhomem,P.S.,Bueno,G.V.,Silva,H.S.R.L.,Kosin,M.D.,2007.Subbacias deTucanoSuleCentral.Bol.Geociênc.Petrobras 15,433–443.

Dalrymple,R.W.,1984.MorphologyandinternalstructureofsandwavesintheBay ofFundy.Sedimentology 31,365–382.

Dalrymple,R.W.,Rhodes,R.W.,1995.Estuarinedunesandbarforms.In:Perillo,G.M. (Ed.),GeomorphologyandSedimentologyofEstuaries.Developmentsin Sedi-mentology.Elsevier,Amsterdam,pp. 359–422.

Ernstsen,V.B.,Noormets,R.,Winter,C.,Hebbeln,D.,Bartholomä,A.,Flemming,B.W., Bartholdy,J.,2005.Developmentofsubaqueousbarchanoid-shapeddunesdue tolateralgrainsizevariabilityinatidalinletchanneloftheDanishWadden Sea.J.Geophys.Res. 110,F04S08,13 p.

Ernstsen,V.B.,Noormets,R.,Winter,C.,Hebbeln,D.,Bartholomä,A.,Flemming,B.W., Bartholdy,J.,2006.Quantificationofdunedynamicsduringatidalcycleinan inletchanneloftheDanishWaddenSea.GeoMar.Lett. 26,151–163. Fielding,C.R.,2007.SedimentologyandstratigraphyofLargeRiverDeposits:

recog-nitionintheancientrecord,anddistinctionfrom‘IncisedValleyFills’.In:Gupta, A.(Ed.),LargeRivers:GeomorphologyandManagement.JohnWileyandSons, pp. 97–113.Chapter 7.

Figueiredo,F.T.,2013.ProveniênciaearquiteturadedepósitosfluviaisdasSub-Bacias TucanoNorteeCentral,Cretáceo(BA).Tesededoutorado.UniversidadedeSão Paulo,Brasil,161 pp.

Figueiredo,F.T.,Almeida,R.P.,Freitas,B.T.,Marconato,A.,Carrera,S.C.,Turra,B.B., 2016.Tectonicactivation,sourceareastratigraphyandprovenancechangesina riftbasin:theEarlyCretaceousTucanoBasin(NE-Brazil).BasinRes. 28,433–445. Filizola,N.,Guyot,J.L.,2009.SuspendedsedimentyieldsintheAmazonbasin:an as-sessmentusingtheBraziliannationaldataset.Hydrol.Process. 23,3207–3215. Fonseca, L., Mayer, L., 2007. Remote estimation of surficial seafloor properties

throughtheapplicationofangularrangeanalysistomultibeamsonardata.Mar. Geophys.Res. 28,119–126.

Freitas,B.T., 2014.A FormaçãoMarizal(Aptiano) naBacia doTucano(BA): con-tribuiçõesàanálisedaarquiteturadedepósitosfluviaiseimplicações paleobio-geográficas.Tesededoutorado.UniversidadedeSãoPaulo,Brasil,175 pp. Horbe,A.M.C.,Motta,M.B.,Almeida,C.M.,Dantas,E.L.,Vieira,L.C.,2013.Provenance

ofPlioceneandrecentsedimentarydepositsinwesternAmazônia,Brazil: con-sequencesfor the paleodrainageofthe Solimões–Amazonas River. Sediment. Geol. 296,9–20.

Hovius,N.,1998.Controlsofsedimentssupplybylargerivers.In:Shanley,K., Mc-Cabe,P.(Eds.),RelativeRole ofEustasyClimateand Tectonismin Continen-tal Rocks. In:Societyfor Sedimentary PetrologySpecialPublication, vol. 59, pp. 3–16.

Hughes-Clarke,J.E.,Mayer,L.A.,Wells,D.E.,1996.Shallow-waterimagingmultibeam sonars:a newtoolforinvestigatingseafloorprocessesinthecoastalzoneand onthecontinentalshelf.Mar.Geophys.Res. 18,607–629.

Jerolmack,D.J.,Mohrig, D.,2005. Frozen dynamicsofmigratingbedforms. Geol-ogy 33,57–60.

Kleinhans,M.G.,Wilbers,A.S.,Vanden Berg,J.H.,2002.Sedimentsupply-limited bedformsinsand-gravelbedrivers.J.Sediment.Res. 72,629–640.

Kostaschuk,R.,Villard,P.,1996.Flowandsedimenttransportoverlargesubaqueous dunes:FraserRiver,Canada.Sedimentology 43,849–863.

Leclair,S.F.,Bridge,J.S.,2001.Quantitativeinterpretationofsedimentarystructures formedbyriverdunes.J.Sediment.Res. 71,713–716.

Leclair,S.F.,2011.Interpretingfluvialhydromorphologyfromtherockrecord: large-riverpeakflows leaveno clearsignature.In:Davidson,S.K.,Leleu,S., North, C.P.(Eds.),FromRivertoRockRecord:the PreservationofFluvial Sediments and Their Subsequent Interpretation. In: SEPMSpecial Publications, vol. 97, pp. 113–123.

Lefebvre,A.,Ernstsen,V.B.,Winter,C.,2011.Bedformcharacterizationthrough2D spectralanalysis.J.Coast.Res. 64,781–785.

Sedimentology 38,553–565.

Parsons,D.R.,Best,J.L.,Orfeo,O.,Hardy,R.J.,Kostaschuk,R.,Lane,S.N.,2005. Mor-phologyandflowfieldsofthree-dimensionaldunes,RioParaná,Argentina: re-sultsfromsimultaneousmultibeamechosoundingandacousticDopplercurrent profiling.J.Geophys.Res. 110,F04S03.http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2004JF000231. Pedreira,A.J.,Lopes,R.C.,Vasconcelos,A.M.,Bahia,R.B.C.,2003.Bacias

sedimenta-resPaleozóicaseMeso–Cenozóicasinteriores.In:Bizzi,L.A.,Schobbenhaus,C., Vidotti,R.M.,Gonçalvez,J.H.(Eds.),Geologia,TectônicaeRecursosMineraisdo Brasil.CPRM,Brasília.

Potter,P.E.,1978.Significanceandoriginofbigrivers.J.Geol. 86,13–33. Reesink, A.J.H., Bridge, J.S., 2007. Influenceofsuperimposed bedformsand flow

unsteadinessonformation ofcross-strata indunesand unitbars.Sediment. Geol. 202,281–296.

scaleinsitumappingofmoderncross-beddeddunedepositsusingparametric echosounding:anewmethodfor linkingriverprocessesandtheirdeposits. Geophys.Res.Lett. 40,3883–3887.

Smith,N.D.,1978.Somecommentsonterminologyforbarsinshallowrivers.In: Miall,A.D.(Ed.),FluvialSedimentology.In:CanadianSocietyofPetroleum Geol-ogyMemorial,vol. 5,pp. 85–88.

Strasser,M.A.,2008.DunasfluviaisnorioSolimões–Amazonas–dinâmicae trans-portedesedimentos.Tesededoutorado.COPPE/UFRJ,148 p.

Svenson,C.,Ernstsen,V.B.,Winter,C.,Bartholomä,A.,Hebbeln,D.,2009.Tide-driven sedimentvariationsonalargecompoundduneintheJadeTidalInletChannel, SoutheasternNorthSea.J.Coast.Res. 56,361–365.