1

DETERMINANTS OF PRIVATE EQUITY BUYOUTS OPERATING

PERFORMANCE: AN EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION IN PORTUGAL

Paulo Jorge Costa da SilvaInternship report Master’s in finance

Supervised by

Professor Miguel Augusto Sousa, PhD

i Acknowledgements

To Rita, for enduring the absences, for the support, patience, comfort and loving care, without her presence this journey would not be the same.

To my family, who always support me during my academic journey, I am deeply grateful for their eternal care.

To my friends and professors, who I had the pleasure to meet and contributed to this step of my academic life, without you this work would not be possible.

To my coleagues and friends at Inter-Risco, Isabel Coelho, João Amaro, Rui Branquinho, Isabel Martins, José Leite, Ana Verde, Sílvia Almeida and Isabel Ferreira, for the amazing opportunity and experience.

Last, but not least, to Professor Miguel Sousa, for all the support, invaluable ideas and suggestions, availability and quickness in replying to my doubts. Thank you, Professor Miguel, for guiding me through this process.

ii Abstract

Despite the consistent increase of private equity (PE) activity in recent years, the bulk of research done have focused on few developed countries, mainly in the United States (US), in United Kingdom (UK), and in France. Nevertheless, PE are also present in less explored markets, a real growth of this phenomenon has been observed in Portugal.

Moreover, despite the strong empirical evidence of post-buyout improvements in operating performance for the first buyout wave, particularly in the US, the results for the second buyout wave are less clear. The different results are partially explained by the differences among the two waves, regarding geographic dispersion, leverage levels, and transaction type.

Therefore, we examine whether, PE buyouts from the most recent data of Portuguese private-to-private transactions created value and what were its determinants. For a sample of 121 buyouts completed between 2006 and 2016 we show that gains in operating performance are either comparable to or slightly underperform those observed for benchmark firms three years after the deal. Notwithstanding, for a subsample of 31 deals with exit data available gains in operating performance exceed those observed for benchmark firms until the pre-exit year.

More, the literature suggests that PE create value by relaxing financial constraints, allowing targets to take advantage of previously unexploited growth opportunities. This complements the well documented literature regarding the stylised fact that PE create value, via agency costs mitigation, trough highly leveraged capital structures.

Thus, we find some evidence that leverage, financial constraints and improvements in targets operating performance appear important in explaining operating gains. PE targets experience a very strong growth in turnover, total assets and operating results, in particular, when they were previously more likely to be financially constrained.

Key Words: Private Equity, Operating Performance, Financial Constraints JEL-Codes: G24, G34, G39

iii Resumo

Apesar do aumento consistente da atividade de Private Equity (PE) nos últimos anos, a maior parte dos estudos realizados focou-se em poucos países desenvolvidos, principalmente nos Estados Unidos (EUA), no Reino Unido e na França. Contudo, PE também estão presentes em mercados menos explorados, observando-se um crescimento da sua atividade em Portugal. Apesar da evidência empírica de melhorias pós-aquisição no desempenho operacional para a primeira onda de aquisições, particularmente nos EUA, os resultados para a segunda onda de aquisições são menos claros. Os diferentes resultados são parcialmente explicados pelas diferenças entre as ondas, em termos de dispersão geográfica, alavancagem e tipo de transação. Portanto, examinamos se as aquisições levadas a cabo por PE, usando os dados mais recentes das transações entre empresas privadas portuguesas, criaram valor e os seus respetivos determinantes. Para uma amostra de 121 aquisições concluídas entre 2006 e 2016 mostramos que os ganhos no desempenho operacional são comparáveis ou levemente abaixo dos resultados observados para empresas comparáveis três anos após a transação. Não obstante, para uma subamostra de 31 transações com dados de saída, os ganhos em termos de desempenho operacional excedem os observados para as empresas comparáveis até ao ano anterior á saída.

Mais, a literatura sugere que os PE criam valor ao mitigar as restrições financeiras, permitindo que os alvos aproveitem oportunidades de crescimento anteriormente inexploradas. Isto complementa a literatura bem documentada sobre o facto estilizado de que os PE criam valor através da mitigação de custos de agência, via estruturas de capital altamente alavancadas. Assim, encontramos alguma evidência de que a alavancagem, restrições financeiras e melhorias no desempenho operacional têm poder explicativo sobre os ganhos operacionais. As participadas dos PE apresentam um forte crescimento no volume de negócios, no total de ativos e nos resultados operacionais, em particular, quando antes eram mais propensas a apresentaram restrições financeiras.

Palavras-Chave: Private Equity, Desempenho Operacional, Restrições Financeiras JEL-Códigos: G24, G34, G39

iv Index Acknowledgements ... i Abstract ... ii Resumo ... iii Index of Tables ... v Index of Figures ... v 1. Introduction ... 1

2. Curricular Internship Overview ... 3

2.1. Inter-Risco Private Equity at a Glance ... 3

2.2. Activities Performed During the Internship ... 4

3. Literature Review ... 5

3.1. Private Equity Definition ... 5

3.2. Private Equity Waves ... 6

3.3. Private Equity Impact on Targets Operating Performance Trough Time ... 7

3.4. Sources of Value Creation ... 9

3.4.1. Agency Theory ...10

3.4.2. Growth Constraints ...11

3.4.3. Operating Improvements and Private equity Characteristics ...12

3.4.4. Sources of Value Creation Corollary ...13

4. Methodology, Sample, and Data Collection ...15

4.1. Methodology ...15

4.2. Sample and Data Collection ...19

4.3. Benchmark ...21

4.4. Sample Description ...22

4.5. Descriptive Statistics ...25

5. Impact of PE Buyouts on the Target Companies Operating Performance ...26

5.1. Growth and Investment ...26

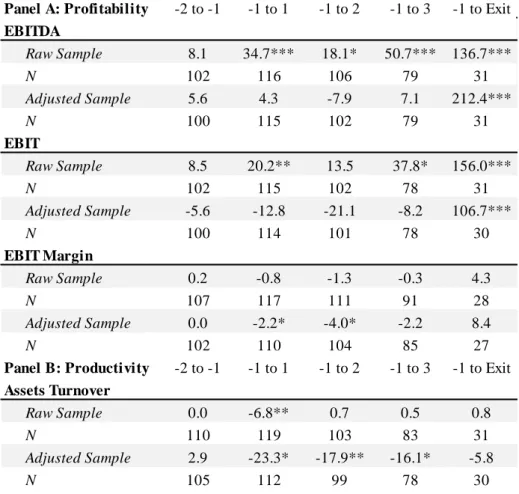

5.2. Profitability, Productivity, Efficiency and Cash Flow ...28

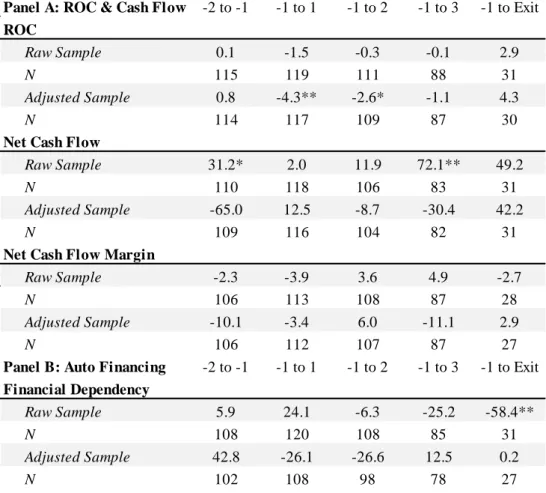

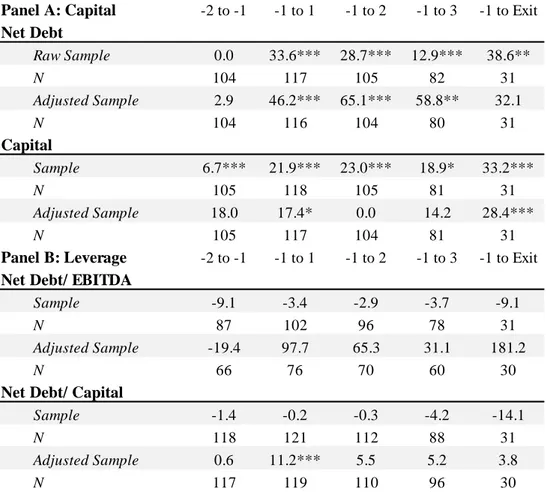

5.3. Capital and Leverage...32

5.4. Operating Performance ...34

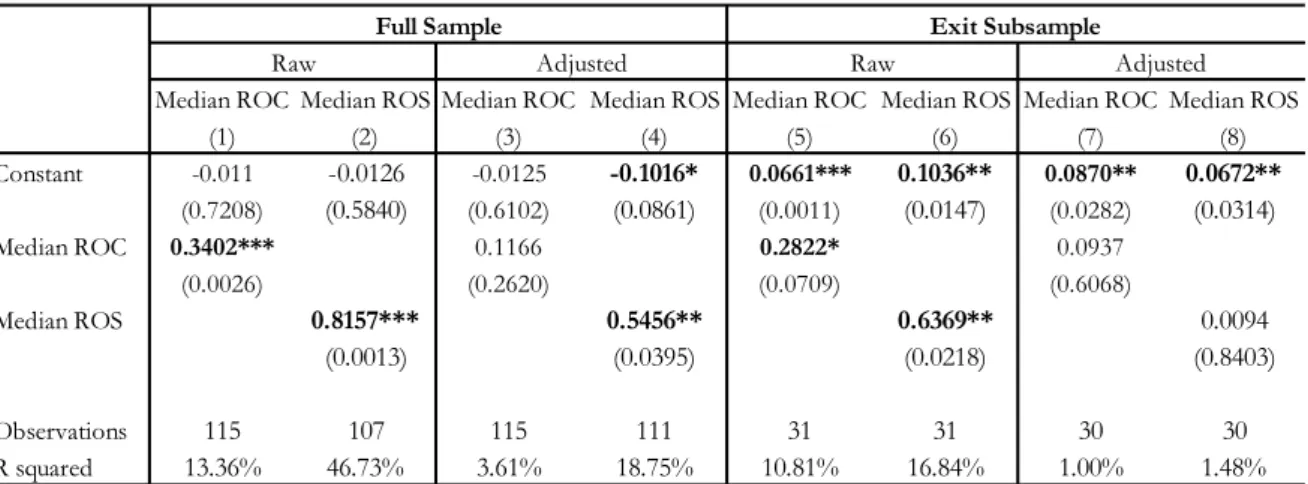

5.5. Determinants of Post-buyout Operating Performance ...37

5.6. Financial Constraints Robustness Check ...41

6. Conclusion ...43

Bibliography ...45

v Index of Tables

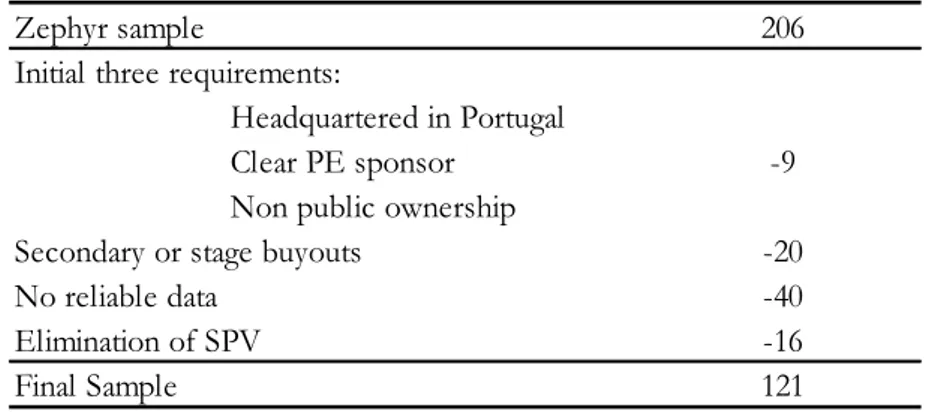

Table 1 - Data Collection Process ... 21

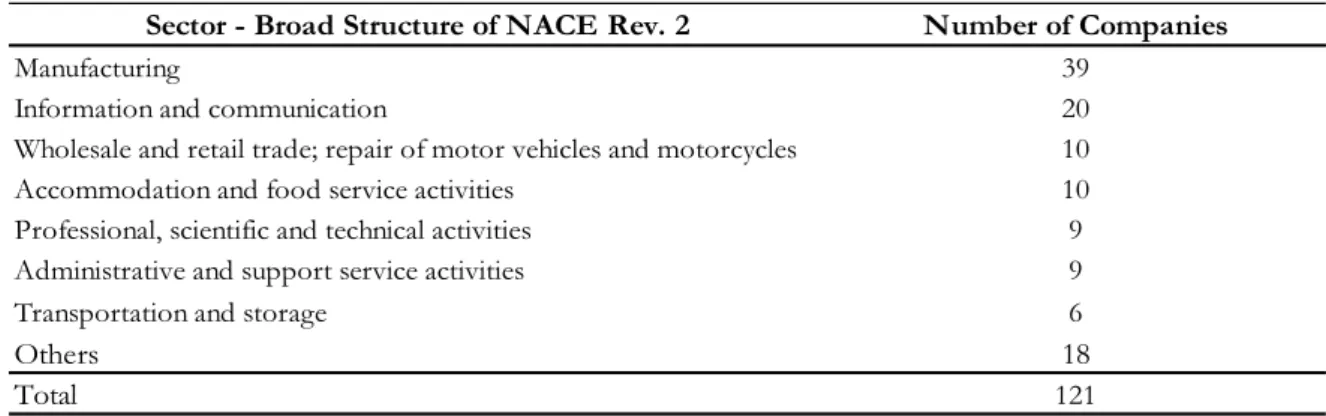

Table 2 - Sector Breakdown ... 18

Table 3 - Transaction by PE Country ... 23

Table 4 - Deal Distribution by PE Firm ... 23

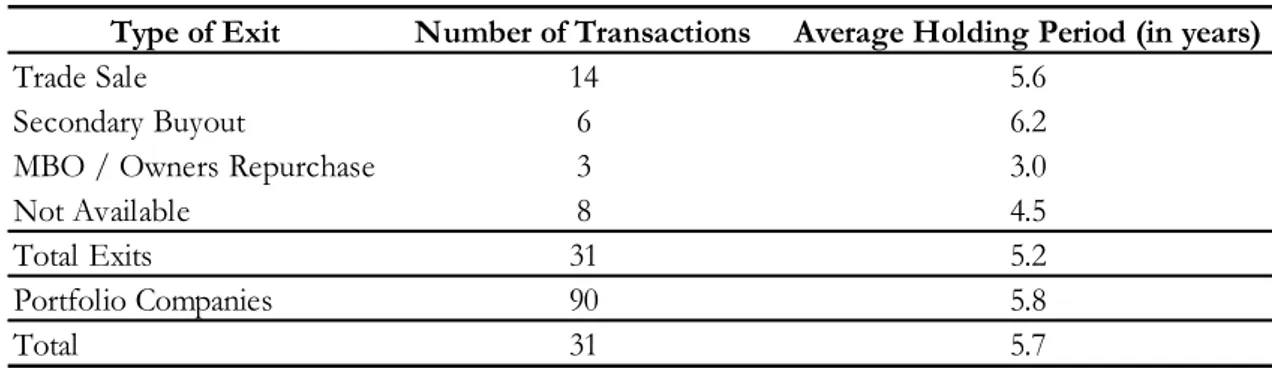

Table 5 - Exit strategies and Average Holding Period ... 20

Table 6 - Descriptive Statistics ... 21

Table 7 - Growth and Investment Change After the PE Entry ... 26

Table 8 - Operating Efficiency Change After Entry ... 30

Table 9 - ROC, Cash Flow and Financial Dependence Change After Entry ... 31

Table 10 - Leverage Change After Entry ... 33

Table 11 - Operating Performance Regressions ... 35

Table 12 - Determinants of PE Buyouts Operating Performance ... 38

Table 13 - Investment Cash Flow Sensitivity Regressions ... 42

Index of Figures Figure 1 - Inter-Risco Current Portfolio Companies ... 3

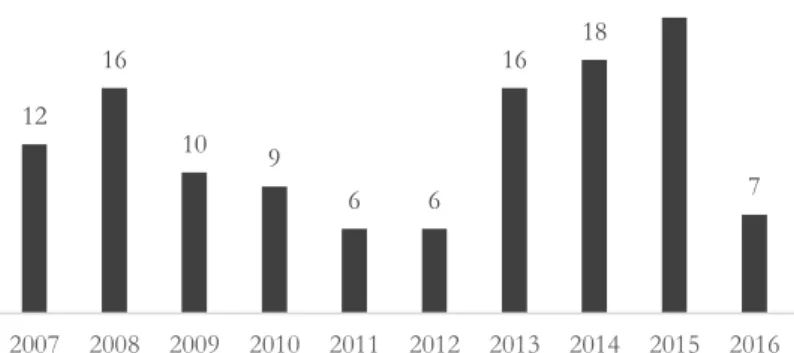

Figure 2 - PE Deals per Year ... 22

1 1. Introduction

This report was developed based on a six months curricular internship at Inter-Risco Private Equity, which took place from September 2018 to March 2019. Inter-Risco is a reference PE firm operating in the Portuguese market since 1988. Two of the key projects of the curricular internship were pipeline development and targets identifications for add-on acquisitions to be pursued by portfolio companies.

Accordingly, the purpose of this report is to extend the research on PE by studying the determinants of PE buyouts operating performance in Portugal, i.e. to understand which are the characteristics ex-ante that justify higher improvements in the targets operating performance after the entry and, therefore, higher value creation, via a multivariate analysis. Target selection is a key problematic of PE firms, hence, understanding the determinants of post-buyout operating performance is a key issue for the curricular internship host entity.

PE are playing an important role in financial markets, and they have attracted academic attention since the 80s (e.g. Jenson, 1986; Kaplan, 1989). Despite the consistent increase of PE backed transactions worldwide in recent years (McKinsey and Company, 2018), the bulk of research done have focused on few developed countries, mainly in the US (Guo, Hotchkiss, and Song, 2011; Kaplan and Strömberg, 2008), and Europe, in particular in the UK (Jelic and Wright, 2011; Wilson, Wright, Siegel, and Scholes, 2012), and in France (Boucly, Sraer, and Thesmar, 2011).

Nevertheless, PE are also present in less explored markets. In particular, a real growth of this phenomenon has been observed in Portugal, where the funds under PE management reached €4.5 Billion in 2017, totalizing 2.3% of the Portuguese GDP, up from approximately €1.2 Billion in 2008 (CMVM, 2017). This growth is particularly relevant once the Portuguese market is dominated by private Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SME), representing 56.8% of total value added in 2016 (European Commission, 2017), a segment fostered by material financial constraints all over Europe (Borbás, 2013), which limits investments and mitigates growth prospects in sales, assets and employment (Boucly et al., 2011).

In fact, the literature suggests that on average PE lessen targets financial constraints and firms present a strong growth in sales and assets (Boucly et al., 2011), with the effect on employment being more diffuse (Wilson et al., 2012). Moreover, PE backed companies benefit

2

from improvements in terms of operating profitability, cash flow generation (Guo et al., 2011), productivity (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2008), and working capital management, even when compare to non-backed PE companies (Wilson et al., 2012).

Furthermore, most value creation in PE portfolio companies is accomplished by operating improvements (Heel and Kehoe, 2005; Acharya, Gottschalg, Hahn, and Kehoe, 2013). In effect, the increased volatility and uncertainty that followed the Global Financial Crisis are expected to lead PE firms to focus more on the things that they can influence rather than relying on market sentiment (Plagborg-Møller and Morten, 2017).

Accordingly, to examine drivers of buyouts operating performance we build on the recent literature that suggests that buyout targets characteristics are important determinants of value creation (Sannajust, Arouri, and Chevalier, 2014). Additionally, despite some studies explore the impact of PE buyouts operating performance in Portugal (e.g., Almeida, 2018), the researchers limited their studies to an univariate analysis, therefore our study intends to build on this past research by applying a multivariate analysis. Moreover, despite several studies have examined the effects of PE on the operating performance of portfolio companies, little research has identified the key operating levers that PE firms influence to improve performance (Gompers, Kaplan, and Mukharlyamov, 2016). Most studies focus only on the effects of PE buyouts on operating performance, not considering what were the characteristics ex-ante associated with higher improvements in the operating performance ex-post. Thus, our research contributes to the literature in two ways: 1) by proposing a general framework to investigate determinants of performance in Portugal from 2007 to 2016; 2) developing the literature on the value drivers that PE influence in order to deploy operating performance improvements.

The remainder of this report is organised as follows. Section 2 presents Inter-Risco, the main activities performed during the internship and its connection with the research developed. Section 3 presents the literature review, defining PE, documenting the historical evolution of PE deal activity, analysing the PE impact on targets operating performance, and discussing the sources of value creation in PE buyouts. Section 4 explains the methodology, the data collection process, and presents the sample description. Section 5 reports, analysis and discusses the results achieved, and section 6 concludes the report.

3 2. Curricular Internship Overview

One of the main motivations for this research was the curricular internship performed at Inter-Risco Private Equity and its connection with two key projects developed during the six months internship, pipeline development and identification of targets for portfolio company’s add-on acquisitions. Thus, this intermediary section briefly presents the identification and description of the activities performed and their context within the institution where the internship was carried out.

2.1. Inter-Risco Private Equity at a Glance

Founded in 1988, Inter-Risco is a reference PE on the Portuguese market, headquartered in Porto, with approximately €130.0 Million of assets under management. Inter-Risco targets the fragmented SME segment, having invested over €200.0 Million in more than 100 Iberian firms. The PE firm focuses on expansion investment, through internationalization, build-up investments, and buyouts developed in fragmented, regulated or growth markets, with the aim of creating leading players in its respective industries. Inter-Risco pursues a generalist sector approach, with a preference for traditional industries with liquid M&A markets, in order to ensure a successful exit strategy and mitigate the overall investment risk.

Inter-Risco obtains majority or significant minority equity stakes within the range of €5.0 to 20.0 Million in medium-sized companies with a maximum turnover of €100.0 Million. In order to create value Inter-Risco follows a strategy of hands-on involvement in all its portfolio companies, from strategy definition to day-to-day considerations. Key areas of intervention include strategic planning and implementation, professionalization and post-deal integration,

business plan execution, networking and deal-flow opportunities, and operational upgrade.

Source: Inter-Risco.

4 2.2. Activities Performed During the Internship

The curricular internship was developed at Inter-Risco Investment Management department, with the main objective of developing thorough sector analysis on the optic of a PE firm, culminating on an investment recommendation to the Inter-Risco Board.

Consistently, one of the key projects of the curricular internship included pipeline development, where a long list of targets was elaborated based on market, industry and company specifics evaluation. Another of the key projects included targets identification for add-on acquisitions to be pursued by companies currently in Inter-Risco portfolio, after an in-depth analysis of the industry’s current dynamics.

Therefore, associated with the described activities it was concluded that a study about the determinants of PE buyouts operating performance in Portugal was an appropriate and relevant research to conduct, considering that the investment decision is a core competence and a critical factor of success in the PE industry. Hence, understanding the determinants of post-buyout operating performance at firm level is a key issue for the curricular internship host entity.

Consequently, the main objectives of this study are: 1) understand if PE backed companies present a superior operating performance than a sample of match firms; 2) identify the pre-buyout determinants of post-pre-buyout improvements in PE targets operating performance.

The following sections include a theoretical framework that duly justifies the pertinence of the performed research, through an adequate review of the literature. The identification, foundation and description of the methodologies used to provide an answer to the presented objectives, the application of the methodologies and the respective analysis of the results.

5 3. Literature Review

3.1. Private Equity Definition

In aleveraged buyout (LBO) a company is acquired by a specialized investment firm using relatively more debt than equity financing. “The LBO investment firms today refer to themselves (and are generally referred to) as private equity firms” (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2008). PE are at the same time an asset class and an alternative source of financing to companies (Santos, 2013). In a traditional LBO transaction, the PE firm acquires a dominant stake in an existing mature firm. This resumes the distinction from venture capital (VC) firms that typically invest in young or emerging companies, and most of the times do not obtain majority control (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2008). More precisely PE include investments such as LBO, management buyouts (MBO), management buy-ins (MBI), expansion and replacement capital, and turnaround investments (Mendes and Sousa, 2013).

Legally the PE firm is organized as a partnership or limited liability corporation. The PE firm raises equity capital through a PE fund, of which the majority are “closed-end” vehicles in which investors [limited partners (LP)] commit a certain amount of money to pay for investments in companies and management fees to the PE firm. The LP typically include institutional investors and high net worth individuals. The PE firm serves as the fund’s general partner (GP), being expected for the GP to provide 1% of the total capital. Traditionally, the fund has a fixed life, usually ten years, but can be extended for up to three additional years. The PE firm typically has up to five years to invest the capital in the fund into companies (if the capital is not invested, it must be returned to LP), and then has an additional five to eight years to return the capital to its investors (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2008), putting the average fund maturity between 10 and 13 years.

On top of the equity raised, the remaining portion of the capital used by PE in buyouts is provided from financial debt, typically bank debt, but can also compress other forms of debt, such as junk bonds, mezzanine debt, paid-in-kind debt, among others (Kolev, Haleblian, and McNamara, 2012). After the fund hits the dotation, GP are in position to deploy the PE funds, if the basic covenants of the fund agreement are followed, examples include deals leverage restrictions and on how much fund capital can invest in a single company (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2008), and capital calls begin as soon as good investment opportunities appear.

6

Traditionally, the PE firm and GP are compensated in three ways. First, the GP earns an annual management fee, a percentage of capital committed, and as investments are realized, a percentage of capital employed. Second, the general partner earns a share of the profits of the fund, that generally equals 20%, called carried interest. Third, some GP charge deal fees and monitoring fees to portfolio companies (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2008). PE funds are generally designed to generate capital profits from the sale of investments complementing income from dividends, fees and interest payments (Gilligan and Wright, 2014).

Jensen (1989) predicted that PE have the potential to become the dominant corporate organizational form. His rationale was based on PE portfolio companies concentrated ownership, strong incentives to PE professionals, and lean and efficient business model that minimizes overheads. This combined with active governance applied to portfolio companies, high leverage capital structures and balanced performance-based managerial compensation, provided the hedge against public companies. The following section proves that Jensen was not much fare way from the empirically evidence, almost 30 years after is prediction.

3.2. Private Equity Waves

The LBO wave of the 80s was a significant event well studied by academics and professionals, particularly in the US (Guo et al., 2011). This LBO wave was transversal across geographies, but the majority of deal volume was limited to the US market (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2008). The wave was driven by favourable economic conditions, increased deregulation, and financial innovations, like junk bonds (Kolev et al., 2012). Large increases in both the number and average size of LBOs contributed to growth, raising the share of LBOs in all M&A volume from 4% to 27%, between 1981 and 1986 (Lichtenberg and Siegel, 1990). This wave was characterized by the breakup of many major conglomerates by corporate raiders, mainly PE, using hostile takeovers (Kolev et al., 2012), hence it became known as the “Entrenchment Era”. The boom ended with the recession of the early 90s, as many of the LBO deals from later in that period defaulted, due to excessive leverage (Guo et al., 2011).

Nearly fifteen years later, the pace of LBO activity reached new record levels, hitting a new maximum in 2007 (McKinsey and Company, 2018). Low interest rates, as consequence of expansionary macroeconomic policies implemented by Central Banks, instigated PE to use LBOs to acquire firms and divest them as soon as the market pushed the value of the firm,

7

while benefiting of a favourable environment characterized by low inflation and steady real economic growth (Gilligan and Wright, 2014). Albeit, the leverage used was significantly less (Guo et al., 2011). PE did not remain confined to the US, spreading to Western Europe and UK, as opposed to the previous wave when the US concentrated the bulk of transactions (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2008). By 2007, cheap debt was no longer available and equity investors became harder to get, a consequence of the 2007/08 Financial Crisis and resultant economic recession, ending the wave perpetuation (Gaughan, 2011).

In the last eleven years, Central Banks lowered interest rates and financial markets were flooded by liquidity as a consequence of Quantitative Easing programs, putting downward pressure on the cost of capital, driving PE deal activity (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2018) and contributing to robust corporate cash balances. Indeed, the resilience of the M&A market is particularly remarkable in the face of increasing valuation multiples (Boston Consulting Group, 2018). These factors contributed to a consistent increase of PE buyouts in recent years.

3.3. Private Equity Impact on Targets Operating Performance Trough Time

A considerable part of empirical work based on LBO transactions from the 80s supports the notion that PE transactions create value, via large gains in operating performance (Guo et al., 2011). During the 80s wave, Lichtenberg and Siegel (1990) studied 12,000 US manufacturer plants and documented that LBO (particularly MBO) that occurred from 1983 to 1986 had a strong positive effect on productivity. Kaplan (1989) for a sample of 76 MBO of public companies completed between 1980 and 1986, concluded that these companies experienced increases in operating income (before depreciation), decreases in capital expenditures and increases in net cash flow. Documenting that the improvement on operating performance was followed by an increase in market value. A year after, Smith (1990) studied changes in operating performance after 58 MBO of public companies between 1977 and 1986 in the US. Operating returns increase significantly from the year before to the year after buyouts, measured by operating cash flows (before interest and taxes) per employee and per dollar of operating assets.

Despite the strong empirical evidence of ex-post LBO improvements in operating performance for the first buyout wave, there are mixed results for the second buyout wave (Ayash and Schütt, 2016). Guo et al. (2011) analysed a sample of 94 public-to-private US transactions between 1990 and 2006. They found that gains in operating performance were not

8

statistically different from those observed for benchmark firms. In a recent study, Ayash and Schütt (2016) using financial statements for 183 US public-to-private LBO, reproduced the results of previous studies, once proxies were modified to account for the LBO process, and find no robust evidence of post-buyout improvements in public-to-private LBO, regardless of the period studied. Wilson et al. (2011) studied a large sample of UK buyouts from 1995 to 2010 and found that PE backed firms achieved superior performance in the period before and during the global recession of 2008, relative to comparable firms that did not experience such transactions. Harris, Siegel and Wright (2005) studied the productivity of UK manufacturing plants subject to MBO. Such plants experienced substantial increases in productivity, the ex-post improvements were higher than those reported in the US by Lichtenberg and Siegel (1990).

While the former studies focused on public-to-private transactions, Chung (2011) analysed 1,009 private-to-private PE transactions in the UK from 1998 to 2007, concluding that the main motive for this type of deals is the elimination of inefficiency and mitigation of investment constraints. Scellato and Ughetto (2012) analysed 241 private-to-private buyouts involving European companies between 1997 and 2004. Their results indicate a positive impact of buyouts on the growth of total assets and of employment in target firms in the short medium term. An equivalent clear pattern cannot be identified for profitability, while PE backed firms present lower operating profitability with respect to the control group three years after a deal is made. Albeit, restricting the analysis to the sub-sample of buyout companies, the authors found that generalist funds negatively and significantly impact the mean ex-post operating profitability of PE-backed firms, while turnaround specialists positively impact operating profitability. Consistent with Cressy, Munari, and Malipiero (2007) that concluded that PE specialization is positively related with value creation.

Continuing with private-to-private transactions, Boucly et al., 2011 using a dataset of 839 French deals over 1994-2004 concluded that targets become more profitable, grow faster than the benchmark, issue additional debt, and increase capital expenditures, particularly those that were financial constrained ex-ante. Bergstrom, Grubb, and Jonsson (2007) studied Swedish buyout companies exited between 1998 and 2006, concluding that buyouts have a significant positive impact on the companies' operating performance. In Portugal, Almeida (2018) using a sample of 100 firms over 2007-2015 concluded that the operating performance of PE backed companies deteriorates, despite the growth of the asset base, revenues and employment. These results were consistent with Mendes and Sousa (2013) findings.

9

Nonetheless, despite regional and temporal idiosyncrasies, the overall evidence suggests a “general consensus across different methodologies, measures, and time periods regarding a key stylized fact: LBOs and especially MBOs enhance performance” even when compared to non-backed PE firms (Cumming, Siegel, and Wright, 2007). This leads to our first hypothesis: H1: Private equity investment improves the operating performance of target firms after the buyout.

3.4. Sources of Value Creation

Kaplan and Strömberg (2009) categorise three sources of value creation: financial engineering, governance engineering, and operating engineering. These levers are not mutually exclusive, but certain PE firms likely focus more in ones than others (Gompers et al., 2016). In financial engineering, PE firms provide strong equity incentives to the management teams of their investees. Cumulatively, leverage has a disciplinary role over management, reducing discretionary power of managers, and generates a tax shield, other common source of value creation pointed by the literature (e.g., Kaplan, 1989; Guo et al., 2011). In governance engineering, PE firms control the boards of their portfolio companies, being actively and accurately involved in governance and key strategic and operating decisions. In operating engineering, PE firm’s industry and operating expertise adds value to their portfolio companies (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2009; Gompers et al., 2016). These facts combined result in higher value creation, with most value creation in PE backed firms being obtained by operating improvements (Heel and Kehoe, 2005; Acharya, et al., 2013).

In this research we focus on two of the three levels of value creation, given data limitations. On the financial engineering side, we will concentrate our analysis on the agency theory, specifically in the disciplinary role of debt, and on the operating engineering side, in the value drivers that PE pull in order to deploy higher improvements in operating performance.

Researchers identify the effects of buyouts on firm’s performance based on a diversity of accounting-based measures, including sales and employment growth (Wilson et al., 2011; Scellato and Ughetto, 2012; Mendes and Sousa, 2013), operating profitability1 (Kaplan, 1989;

1 Commonly, operating profitability, scaled by sales or total assets, has been adopted as a measure of operating

10

Guo et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2011), cash flow (Smith, 1990; Scellato and Ughetto, 2012; Almeida, 2018) and productivity (Lichtenberg and Siegel, 1990; Harris et al., 2005). Generally, relatively more leveraged deals and firms with a good operating performance ex-ante are associated with better ex-post operating performance (Guo et al., 2011).

3.4.1. Agency Theory

Prior research has relied on agency theory as the theoretical base to explain ex-post performance of PE portfolio companies. The lack of a perfect alignment of interest between ownership and management originates agency costs. Agency costs are incurred by shareholders, as a result of the separation of ownership and control (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Corporate governance mechanisms can mitigate agency costs (Jensen, 1986). There are two main categories of governance mechanism, internal and external. Internal mechanisms can be split into monitoring and incentive-related (Sannajust et al., 2014). Monitoring mechanisms refer to board structures (Fama and Jensen, 1983), external shareholdings unaffiliated with management (Shivdasani, 1993) and debt (Jensen, 1986). The main external corporate governance mechanism is the market for corporate control (Jensen, 1986; Shivdasani, 1993), acting as the last resort mechanism if the internal mechanisms fail (Sannajust et al., 2014). Therefore, the problematic becomes one of explaining how PE buyouts mitigate agency costs.

The main explanation is related with cash generation and become known as the Free Cash Flow theory perpetuated by Jensen (1986). Agency costs are incurred because free cash flow is spent on projects that do not generate the required return (Jensen, 1986). These firms exhibit low growth opportunities and large free cash flows, with strong cash balances the discretionary power of managers increase, increasing the propensity of value expropriation from shareholders. Those firms may become a buyout target. Usually debt levels increase with buyouts. The disciplining role of debt prevents managers from wasting resources. Additionally, PE firms are actively and accurately involved in governance and key strategic and operating decisions. It follows that agency theory contends that buyouts result in a superior governance model (Scellato and Ughetto, 2012).

Using agency theory as theoretical foundation, several empirical studies find an improvement in the operating performance of PE targets following a buyout. Most of these studies focused the first wave of PE deals in the 80s and mainly focus on public-to-private

11

transactions, specifically in the US (e.g., Kaplan, 1989; Smith, 1990; Lichtenberg and Siegel, 1990). These studies commonly assess the performance of target companies after the buyout with respect to the industry average or simply compare the firms’ ex-ante and ex-post performance. More recent studies associated with the second wave of buyout transactions, which occurred between the 90s and 2009, put additional effort in comparing buyout firms to other relevant benchmarks, after the contribution of Barber and Lion (1995) that provided a theoretical framework for the accounting based proxies and benchmark methods, and more evidence other than that from US has appeared (e.g., Bergstrom et al., 2007; Wilson et al., 2011). Traditionally, in this type of studies the literature proxy’s agency issues via leverage ratios, cash holdings, or ownership dispersion (e.g. Kaplan and Strömberg, 2009; Guo et al., 2011; Sannajust et al., 2014). PE targets presenting pre-deal relatively low leverage ratios, high cash holdings and dispersed ownership translates into higher agency costs, under the form of relatively lower operating profitability, thus being more prone to operating improvements.

However, the agency view cannot fully explain the LBO of private firms (Wright et al. 2000) because it is less likely that private firms suffer from agency problems due to their concentrated ownership structure (Chung, 2011) and due to its family owned and managed base. Accordingly, while for the first wave the mitigation of agency conflicts is well documented, more recent studies like Guo et al. (2011), in US for public-to-private deals, or in the case of private-to-private transactions Scellato and Ughetto (2012) in European, or Chung (2011) in UK, do not find clear evidence in favour of Jensen's hypotheses.

3.4.2. Growth Constraints

A relatively recent stream of literature suggests that PE create value by relaxing financial constraints, allowing targets to take advantage of unexploited growth opportunities. This driver has special relevance in Portugal, since it is a country with many family managed businesses and where the credit and stock markets are less developed than those of the US and the UK.

Boucly et al. (2011) analysing a sample of PE French deals find solid evidence in private-to-private transactions, particular in industries with strong reliance in external finance, that PE targets become more profitable, grow much faster than the benchmark, issue additional debt, and increase capital expenditures. Engel and Stiebale (2013) analyse a sample of firms in the UK

12

and France. In both countries, they find that portfolio firms are characterized by higher investment levels and fewer financial constraints after buyouts. In fact, in the UK, PE backed buyouts outperform non-PE backed firms in terms of both indicators. Bertoni, Feerer, and Martí (2013) argue that thanks to PE and VC ability in overcoming information asymmetries, they will entail a reduction in the financial constraints which tampered the growth of portfolio companies. The authors predict, a greater dependency of investments to cash flow for PE-backed firms, driven by the renewed interest for growth of their management combined with higher leverage, confirming the hypothesis on a large panel of small Spanish private firms.

In fact, while the Free Cash Flow theory of Jensen (1986) implies an overinvestment in the pre-buyout phase, the asymmetric information hypothesis and elimination of growth constraints (Bertoni et al., 2013) predicts an underinvestment in the pre-buyout phase. Indeed, financial constraints ex-ante are associated with higher post-buyout operating performance. Bertoni et al. (2013) findings, gains in operating performance supported by higher investment levels, indicate that targeting firms which are financial constrained matters, since the authors find the most pronounced and statistically significant effects for SME, also Engel and Stiebale (2013) achieve the same conclusion for UK and French SME, while Boucly et al. (2011) find that the impact on growth is also more pronounced among family owned French SME and industries with higher financial dependence.

Growth constraints are proxied by ex-ante sales or assets growth (Boucly et al., 2011; Engel and Stiebale, 2013), while financial constraints are proxied via financial dependence ratios [e.g. (CAPEX - Gross cash flow)/CAPEX (Rajan and Sinagales, 1998)]. Other studies proxy financial constraints via Investment Cash Flow (ICF) sensitivity (Bertoni et al., 2013).

3.4.3. Operating Improvements and Private equity Characteristics

Most value creation in PE backed firms is obtained by operating outperformance (Heel and Kehoe, 2005). PE investors expect to add value via greater focus on increasing growth than on reducing costs (Gompers et al., 2016). Albeit, both revenue enhancement (e.g. Gompers et al., 2016), via clients and markets diversification, and cost control (Chung, 2011), economies of scale and/or scope and focus on efficiency gains, are common strategies. Consistent with this stream of literature, recent studies found reliable results regarding the positive and statistically significant relation among PE specialization and improvements in buyouts operating

13

performance. The rationale is based on the fact that stage or industry specialized investors face fewer information asymmetries and uncertainty due to better knowledge of the firms within that specific stage of development or industry (Ughetto, 2010).

Cressy et al. (2007) tested if investment specialisation by industry or stage provides the PE firm with a competitive advantage (advantages-to-specialization hypotheses). Using data from 122 UK buyouts from 1995 to 2002 and a matched sample of non-PE backed UK they found that over the first three post-buyout years: (i) operating profitability of PE-backed companies is greater than the benchmark, consistently with the Free Cash Flow theory; (ii) industry specialization of PE firms adds extra improvements to operating performance, consistently with the industry-specialization hypothesis; (iii) stage (buyout) specialization does not impact profitability but may improve growth. More recent studies, like Scellato and Ughetto (2012), analysed a sample of 241 private-to-private buyouts involving European companies between 1997 and 2004, the authors found that generalist funds negatively and significantly impact the mean ex-post operating profitability of PE-backed firms, while turnaround specialists are positively associated with operating profitability. The bulk of this studies use binary variables to group PE into specialists and generalists’ firms, via qualitative assessment of PE portfolio firms. Nevertheless, PE firms differ widely in terms of age and size of funds under management, and not only in stage and industry focus (Cressy et al. 2007), thus all these variables should be considered. Accordingly, Acharya et al. (2012), studied 395 deals closed from 1991 to 2007 in Western Europe by 37 large, mature PE, concluding that the bulk of value creation arises from improvements in operating performance, leverage and exposure to the specific sector. They also found that ownership by large, mature PE firms has a positive impact on the operating performance of investees, when compared to the sector. However, because PE cannot control its experience or size, and these variables do not relate directly with the purpose of this study we did not consider them in our analysis.

3.4.4. Sources of Value Creation Corollary

Given these general evidences, suggesting that PE firms develop different strategies to create value, and the fact that the increased volatility and uncertainty that followed the Global Financial Crisis are expected to lead PE firms to focus more on the things they can influence

14

rather than relying on market sentiment (Plagborg-Møller and Morten, 2017), like operating performance improvements, we advance the following hypothesis:

H2: Target firms present certain ex-ante characteristics that justify higher operating improvements ex-post. In particular, firms with low growth ex-ante (both in terms of sales and assets), high agency conflicts (e.g. proxied by low leverage ratios), and firms that had underperform the industry in the recent past (benefiting from PE experience either because of its track record or industry/ stage – specialization) are those more prone to ex-post operating improvements.

15 4. Methodology, Sample, and Data Collection

In the previous section we concluded that, despite the strong empirical evidence of post-buyout improvements in operating performance for the first post-buyout wave, there are mixed results for the second wave (Ayash and Schütt, 2016). The different results found in the two waves are partially explained by the differences among them: i) while the bulk of deals in the first wave remained confined to the US, the second wave spread across the UK and continental Europe (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2009); ii) the debt load on an average deal was significantly less in the second buyout wave than in the first wave (Guo et al., 2011); iii) the majority of research in the first wave was focused on public-to-private transactions, while in the second wave there were a lot more studies focused on private-to-private transactions.

In Portugal no consistent evidence was found regarding improvements in PE backed companies after the buyout when compared to the appropriate benchmark (Mendes and Sousa, 2013; Almeida, 2018), which goes against our first hypothesis.

However, given standard sources of value creation pointed in the literature, and based on the general evidence discussed in the previous sections we theorize that firms that before the buyout present a certain type of characteristics are those more prone to operating improvement in the post-buyout phase. Therefore, this section defines the sample and explains the methodology used.

4.1. Methodology

In this study a set of variables are used to assess the evolution of a company before and after the buyout. Book value of total assets (turnover) are used as proxy for size (growth). Capital expenditures (CAPEX2) translates the investment activity by the company. EBITDA3 and

EBIT4 are used as proxies to operating cash flow generated by the companies, before and after

maintenance investment, respectively. Net cash flow is analysed in order to proxy the cash

2 CAPEX defined as Fixed Assets

t - Fixed Assetst-1 + Depreciations and Amortizationst. Fixed assets defined as

the sum of tangible assets, intangible assets, investment properties, financial investments, and goodwill.

3 Earnings before interest, tax, depreciations and amortizations. 4 Earnings Before Interest and Tax.

16

generation of a firm after its investment activity, being defined as EBITDA after CAPEX. Return on capital (ROC) is used as a measure of economic performance at company level.By using this last indicator, we can separate the variation of the ROC into operating profitability expansion (contraction), through EBIT margin, or productivity improvements (decreases), via assets turnover. Therefore, profitability and productivity measures are calculated by deflating the EBIT by the end-of period turnover and turnover by the end-of-period capital. Capital is defined as the sum of equity and net debt. These ratios aim to measure the ability of the company to improve or maintain its operating efficiency and the efficiency in the use of its assets. These indicators have been extensively used5 in past studies (for example Kaplan, 1989; Guo et al.

2011) and partially adapted to control for acquisitions and divestures after the buyout. All variables are presented before interest and taxes, therefore controlling for effects resulting from capital structure and tax brackets. All the ratios are winsorised between 0.05 and 0.95 percentiles, and the results presented as the median values similar to other studies (e.g. Guo et al., 2011) in order to control for outliers.

To answer our first research question, we follow Healy et al. (1992), that employed a simple linear regression to estimate improvements in post-buyout performance. The model consists in an OLS regression (i=1, . . .n) where n is sample size:

Median 𝑅𝑂𝐶𝑖𝑎𝑑𝑗𝑒𝑥−𝑝𝑜𝑠𝑡 = α + 𝛽𝑖 Median 𝑅𝑂𝐶𝑖𝑎𝑑𝑗𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒+ 𝑒𝑖

Median 𝑅𝑂𝐶𝑖𝑎𝑑𝑗𝑒𝑥−𝑝𝑜𝑠𝑡 is computed as the median yearly ROC of each target firm in the years [t=+1, +2, +3] following the buyout date less the median yearly ROC of each control firm in the same period. Median 𝑅𝑂𝐶𝑖𝑎𝑑𝑗𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒 is the median yearly ROC of each target firm in the years [t=-3, -2, -1] less the median yearly ROC of each control company in the same period. An additional subsample is analysed, encompassing all the years from the buyout to the exit. The

5 Generally, the literature uses return on assets (ROA), defined as EBITDA over year-end or year-beginning total

assets (e.g. Kaplan, 1989). Nonetheless, other authors, in more recent studies use alternative measures, such as EBITDA over year-end equity plus debt minus trade payables (e.g. Boucly et al., 2011). We decided to use EBIT in the numerator, similar to Sannajust et al. (2015), since it is a better proxy for cash flow than EBITDA, for a detailed discussion please see Stumpp, Marshella, Rowan, McCreary, and Coppola (2000).

17

coefficients (𝛽𝑖) can be interpreted as the relation between pre- and post-buyout performance,

while the intercept α is an estimate of the mean amount of post-buyout performance left unexplained by exogeneous effects, like positive industry or economic momentum, or business cycle phase and must be, by definition, attributed to the PE skill.

To develop the multivariate analysis, that intends to answer to our second research question, we followed the methodology Guo et al. (2011). We regress one independent variable against a set of independent variables. The methodology consists in a differential model based on a cross-section6 OLS regression:

∆𝑅𝑂𝐶𝑖𝑎𝑑𝑗𝑒𝑥−𝑝𝑜𝑠𝑡 = α + 𝛽1 𝑇𝐴𝐺𝑖𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒+ 𝛽2 𝐶𝑇𝑖𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒+ 𝛽3 𝐹𝐷𝑖𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒+𝛽4

𝐿𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒𝑖 + 𝛽5 𝑅𝑂𝐶𝑎𝑑𝑗𝑖𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒+𝛽

6 𝑃𝐹𝐺𝑖𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒+𝛽8 𝑃𝐷𝐺𝑖𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒+ 𝑒𝑖

∆𝑅𝑂𝐶𝑖𝑎𝑑𝑗𝑒𝑥−𝑝𝑜𝑠𝑡 is the ROC of each target firm i, in the year t after the buyout (t=+3) less the ROC of each target firm in the year before the buyout (t= -1) adjusted for the change in

ROC of each control company over the same period.

𝑇𝐴𝐺𝑖𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒, 𝐶𝑇𝑖𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒, 𝐹𝐷𝑖𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒, 𝐿𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒𝑖 , 𝑅𝑂𝐶

𝑎𝑑𝑗𝑖𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒, 𝑃𝐹𝐺𝑖𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒, and

𝑃𝐷𝐺𝑖𝑒𝑥−𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑒 are the independent variables total assets growth, CAPEX to turnover, financial dependence, net debt to EBITDA, adjusted ROC, profitability growth and productivity growth, respectively, for each target company 𝑖, in the year before the buyout (t= -1), explained below. This allow us to conclude about the ex-ante variables that are related with higher improvements in a firm operating performance after the buyout, in the spirit of Guo et al. (2011).

For dependent variable we use one measures of economic performance at company level, ROC. Following Guo et al. (2011), we adjust the ROC, being defined as the differential ROC from the firm subjected to the buyout and the ROC of a matched firm that did not undergo a buyout, in order to eliminate systematic or industry specific factors.

6 Despite the original data originate a balanced panel, multiple observations for multiple subjects across different

years, because the regression involves two different time periods the data was reorganized as cross-sectional, with the control for year fixed effects being made via year dummies, following the methodology of Guo et al. (2011) widely use in this type of studies.

18

For independent variables, given the purpose of our study, we use turnover (assets) growth and CAPEX over turnover to proxy for growth and investments constraints, based on the literature that suggests that financial constrained targets become more profitable and grow faster than the benchmark (Boucly et al., 2011; Engel and Stiebale, 2013). A measure of financial dependence is used, to directly proxy financial constraints, in the spirit of Rajan and Zingales (1998), for each firm, we calculate the difference between CAPEX and EBITDA, normalized by CAPEX. This ratio measures the fraction of investment that is financed externally, with higher values indicating financial constraints, since the firms as a lower auto financing ability being more dependent on external financing, which because of asymmetric information is more expensive and not always available.

Additionally, based on the empirical evidence that firms with higher ex-ante agency conflicts are those more prone to improvements in operating performance ex-post (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2009; Sannajust et al., 2014), we proxied agency conflicts, as the leverage ratio of net debt over EBITDA, similarly to Cressy et al. (2007) and Boucly et al. (2011). This ratio allows us not only to assess the absolute level of debt, but also the ability of a firm to generate operating cash flow to face its debt service.

Lastly, to build on the literature that suggests that most PE investors expect to add value to their portfolio companies, via optimizing strategic and operating decisions, as a consequence of GP extensive experience (Acharya et al., 2012), we control for ex-ante performance by inserting in the equation the ex-ante level of adjusted ROC, following other authors such as Guo et al. (2011) and Sannajust et al. (2014). Profitability (EBIT margin) and productivity (asset turnover) growth are used to understand the trend of each business regarding margins and efficiency in the use of its assets.

Following previous studies (Cressy et al., 2007; Sannajust et al., 2014), we considered a time window extending from one year before to three years after a deal was made. Basically, we have a three-year period after the transaction (year +1 to year +3) compared to the last fiscal year before the transaction (year -1).Additionally, for deals with a known outcome in terms of exit, we extend our analysis to the last year before the exit, similar to Guo et al. (2011).

Complementary, we used the difference-in-difference approach to support our multivariate analysis, by measuring the median changes of the absolute variables and the ratios used in a three-year period after the transaction (year +1 to year +3) and until the pre-exit year, in relation

19

to the last fiscal year before the transaction (year -1). For the pre-transaction period, an analogous analysis is made but with reference to 2 years before the buyout (year -2). Generally, in this type of studies, the fiscal year of the transaction (year 0) is not considered since it is difficult to separate the pre and post-transaction performance within the year.

Accordingly, to assess the median change in the relative variables we use the following formula 𝑉𝑖𝑡+𝑗− 𝑉𝑖𝑡−1 to analyse the post-transaction period, and 𝑉𝑖𝑡−1− 𝑉

𝑖𝑡−2 to analyse the

pre-buyout period, which give the percentage change of each ratio. To evaluate the median change of the absolute variables we use the following formula 𝑉𝑖

𝑡+𝑗 − 𝑉𝑖𝑡−1

𝑉𝑖𝑡−1 , for the post-buyout

period, and 𝑉𝑖𝑡−1− 𝑉𝑖𝑡−2

𝑉𝑖𝑡−2 for the pre-buyout period which provide the percentual change of each

absolute variable. Although, in the absolute variables we have two problems every time that a variable can take positive and negative values: i) if a change of signal occurs; and ii) if an absolute value is negative and becomes less negative. Therefore, a common solution for these problems is to use the so-called absolute method, hence in our univariate analysis the denominator is always the absolute number. In the abovementioned formulas, 𝑉 represents the relative or absolute variable in analysis, for each company 𝑖, 𝑡 the fiscal year of the transaction and 𝑗 the fiscal year under analysis.

Additionally, analogous to the multivariate analysis, we adjust the results to the control sample. Thus, the adjusted sample is obtained by subtracting from the changes in relative and absolute variables of sample companies (raw sample) the control sample changes in the same variables and ratios for the same period.

4.2. Sample and Data Collection

We analyse a sample of Portuguese firms that underwent buyouts from 2007 to 2016. Data on buyouts are derived from two different commercial databases: Sabi2 and Zephyr7, both

commercialized by Bureau Van Djick. The latter provides information about the M&A deals,

20

including the portfolio company name, acquisition date and the buyers/investors. Sabi was used to collect the historical financials relative to the PE backed companies.

Following Cressy et al. (2007) deal screening strategy, to a transaction be included in the sample three cumulative requirements need to be fulfilled: i) the target must be headquartered in Portugal; ii) there must be a clearly identifiable PE sponsor(s); iii) the sponsor(s) must not be directly or indirectly managed/owned by the government or other public entities.

The first requirement is necessary since the aim of this research is to examine the operating performance of Portuguese targets. The nationality of the PE firm is irrelevant considering the purpose of this study, thus both Portuguese and foreign PE firms are included in the sample.

The second requirement is related with the fact that for a PE sponsor to be considered valid, the PE firm should focus on acquisitions of mature companies. Therefore, we include investments such as LBO, MBO, MBI, expansion and replacement capital and turnaround investments, which excludes most VC investments.

The third requirement is needed since public entities may pursue other purposes than wealth maximizing objectives. These entities may have a broader set of public policy goals, including not only value-creation, but also innovation, competition (Brander, Egan, and Hellmann, 2008), territory development, or employment growth (Cumming and Macintosh, 2006).

Lastly, in the case of secondary or stage buyouts only the first transaction, i.e. when the portfolio company became PE backed for the first time, was included in the data, given the idiosyncratic characteristics and motivations for PE sponsors to undertake this exit strategy extensively discussed in a report of Saints Capital Services (2010).

From the initial sample of 197 deals, 20 transactions were excluded since those transactions were secondary or stage buyouts. This resulted in a reduction from 197 to 177 companies. Via Sabi database we looked at each firm which had received PE sponsorship and the outcome was 137 companies from the previous list provided by Zephyr database, since data was not available or was not reliable8 for 40 PE backed companies. Financial firms are not comparable to other

non-financial firms, thus fall out of this study scope, and regarding “Head Offices” or “Holding” activities it is commonly accepted that these companies are difficult to analyse on a

8 For instance, the financial statements were not available for certain sample years, the firms were in liquidation,

21

non-case study basis, therefore another 16 companies were retrieved from the initial sample, with the final sample encompassing 121 firms. Table 1 summarizes the data collection.

Lastly, in a first regarding the Portuguese PE market research, an additional hand collected subsample was created in order to identify all sample firms that already have been exited by PE sponsors. From this analysis a subsample of 31 exited firms emerged.

This table reports the data collection process, from the initial 206 transactions identified in Zephyr to the final 121 companies.

4.3. Benchmark

The assessment of the impact of buyouts on the performance of PE-backed firms requires the identification of a control sample. PE and target companies do not meet randomly, we need to account for the ex-ante selection process to make unbiased estimates (Boucly et al., 2011).

To identify an appropriate control sample Barber and Lion (1995) methodology was used. Therefore, the sample of matched firms was controlled for the industry, size, and past performance. Accordingly, to respect the first criteria the comparable company has the same first three code digits of the NACE Rev. 2 than the company that experienced the PE buyout, similarly to Kaplan (1989), Guo et al. (2011), and Wilson et al. (2011). Regarding the second criteria, size, following an adapted version of Guo et al. (2011) we use a book value of total assets between 80%-120% of the sample firm’s book value of total assets. Considering the third criteria, past performance, we follow once again Guo et al. (2011) that stipulated a level of operating performance (in our case proxied by ROC) between 80%-120% or within ±0.01 of

Table 1 - Data Collection Process

Table 2 - Data Collection Process

Zephyr sample 206

Initial three requirements:

Headquartered in Portugal

Clear PE sponsor -9

Non public ownership

Secondary or stage buyouts -20

No reliable data -40

Elimination of SPV -16

22

the level of the sample firm’s performance in year - 19. On the case of multiple benchmarks, the

matched firm that has the lower absolute deviation of the last criteria was chosen. A sample of 121 matched firms was composed, which controls for the industry, size, and past performance, using Sabi database.

4.4. Sample Description

The final sample encompasses 121 PE transactions occurred in Portugal from 2007 to 2016. In Figure 2 it is possible to conclude that our sample is dominated by deals from early start of the financial crisis to the peak of sovereign debt crisis, 52% of the transactions occurred in the period 2007-13, whilst 38% of deals occurred in the economic turmoil aftermath. Following the international trend, Portuguese PE deals present a cyclical nature, with the number of deals peaking in the year prior to the financial crisis, tampering during the crisis, and redeeming afterwards.

This figure reports the distribution of PE transactions by year during the analysed period.

In terms of sectors, our sample encompasses multiple different 4-digit NACE codes, however in order to give a broader view of the different industries we cluster them in the Broad Structure of NACE Rev. 2, as presented in Table 2. Accordingly, 32% of our sample comes from Manufacturing, 17% belongs to Information and Telecommunications, and 17% respects to Wholesale and Retail (9%) and to the Hospitality sector (9%). Thus, despite traditional sectors dominate our sample, technology related deals are rising in importance. This is aligned with the

9 Only one lag was considered, since the marginal effect of extra lags is negligible, see Barber and Lion (1995) for

standard arguments. 12 16 10 9 6 6 16 18 21 7 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

23

PE Firms Number of Transactions

Explorer Investments - S.C.R. S.A. 23

Espirito Santo Capital S.C.R S.A. 12

ECS S.C.R., S.A. 12

Portugal Capital Ventures - S.C.R. S.A. 11

Others 63

Total 121

strong industrial base of the Portuguese economy, the strong development of Information Technology related companies, and the robust tourism growth observed in Portugal.

This table presents the sample sectors breakdown, clustered in the Broad Structure of NACE Rev. 2.

Concerning the PE firm nationality, Portuguese PE firms, defined as those headquartered in Portugal, account for the bulk of deal activity, representing 88% of the sample transactions as observable in Table 3.

This table reports the nationality of PE firms involved on the sample transactions.

Regarding deals concentration by acquiror, as seen in Table 4, no PE firm accounts for more than 20% of the sample transactions, which is particular important given the relatively small number of active PE in the Portuguese market. The most active PE firm was Explorer Investments - S.C.R. S.A., with 19% of all transactions, followed by Espírito Santo Capital S.C.R S.A. and ECS S.C.R., S.A., each with a 10% share of the total 121 deals, which is concordant with the moderate concentration verified in the Portuguese PE industry (CMVM, 2016).

This table reports the breakdown of the sample transactions by PE firm. Table 2 - Sector Breakdown

Table 3 - Transaction by PE CountryTable 4 - Sector Breakdown

Country Number of Transactions

Portugal 107

Spain 8

United States 3

Others 3

Total 121

Table 3 - Transaction by PE Country

Table 5 - Deal Distribution by PE FirmTable 6 - Transaction by PE Country

Table 4 - Deal Distribution by PE Firm

Table 7 - PE Exits per YearTable 8 - Deal Distribution by PE Firm

Sector - Broad Structure of NACE Rev. 2 Number of Companies

Manufacturing 39

Information and communication 20

Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles 10

Accommodation and food service activities 10

Professional, scientific and technical activities 9 Administrative and support service activities 9

Transportation and storage 6

Others 18

24

Relatively to the subsample of 31 exited firms, the most active year in terms of exits was 2017, as observable in Figure 3, representing 42% of all identified exits, reflecting a tendency of exit postponement to after the economic turmoil and valuations recovery.

This figure reports the exits, by exit year, already completed from the initial sample of 121 PE backed firms.

The average holding period of the full sample10 (121 companies) reaches 5.7 years,

varying from 3.0 years when the PE backed company is sold to the management or to the initial owners to 6.2 years in secondary buyout exits, as observable in Table 5. The average holding period of portfolio firms is 5.8 years, very close to the full sample holding period, since only 26% of the buyouts were already divested.

Regarding the exit route, the preferred strategy was trade sale, followed by secondary buyouts, 45% and 19% of all exits, respectively. As expected, the holding period in trade sales in significantly less than the holding period in sales to another PE firm.

This table details the exit deals by exit strategy and the average holding period by exit route. Trade sale is defined as a sale to a strategic investor, secondary buyout is understood as the sale to another PE firm, MBO is a traditional management buyout, and owners repurchase is defined as a sale to the (previous) majority shareholder.

10 For firms that were not yet divested the holding period is the period from the entry year to the present year,

2019.

Table 5 - Exit strategies and Average Holding Period

Table 9 - Descriptive StatisticsTable 10 - Exit strategies and Average Holding Period Type of Exit Number of Transactions Average Holding Period (in years)

Trade Sale 14 5.6

Secondary Buyout 6 6.2

MBO / Owners Repurchase 3 3.0

Not Available 8 4.5 Total Exits 31 5.2 Portfolio Companies 90 5.8 Total 31 5.7 1 1 3 1 2 3 4 13 3 2009 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

25 4.5. Descriptive Statistics

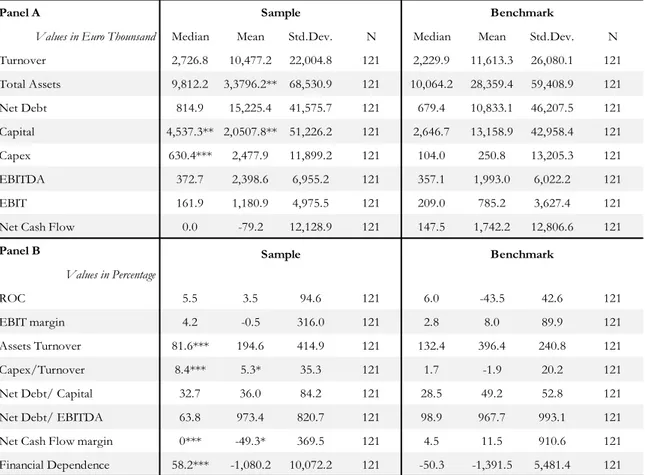

As shown in Table 6, the PE target company has the same median size than the comparable firm, in terms of total assets or turnover. Buyout targets present a statistically significantly higher median CAPEX than the benchmark, both in absolute terms and in percentage of turnover. The median capital of PE targets is higher than the match sample, while the asset turnover is statistically significantly lower than the matched firms. Regarding financial dependence, PE targets appear to be more dependent on external capital than the benchmarks. The match sample is not statistically different from the initial sample for the key variable, ROC, indicating that we do have a representative sample. The statistically significant difference in terms of the average in absolute measures is a result of the discrepancy in size of PE backed companies and considering our match criteria (please see section 4.3), for large companies’ small percentage variations originate large absolute changes, influencing average values.

This table reports key variables for the pre transaction year (-1) for the initial sample and the matched sample. A T-test and Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test were used in order to test whether average values and median values of the sample companies, respectively, are significantly different from the match companies. We use ***, **, and * to denote significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level (two-sided), respectively.

Table 6 - Descriptive Statistics

Table 11 - Growth and Investment Change After the PE EntryTable 12 - Descriptive Statistics

Panel A

Values in Euro Thounsand Median Mean Std.Dev. N Median Mean Std.Dev. N

Turnover 2,726.8 10,477.2 22,004.8 121 2,229.9 11,613.3 26,080.1 121 Total Assets 9,812.2 3,3796.2** 68,530.9 121 10,064.2 28,359.4 59,408.9 121 Net Debt 814.9 15,225.4 41,575.7 121 679.4 10,833.1 46,207.5 121 Capital 4,537.3** 2,0507.8** 51,226.2 121 2,646.7 13,158.9 42,958.4 121 Capex 630.4*** 2,477.9 11,899.2 121 104.0 250.8 13,205.3 121 EBITDA 372.7 2,398.6 6,955.2 121 357.1 1,993.0 6,022.2 121 EBIT 161.9 1,180.9 4,975.5 121 209.0 785.2 3,627.4 121

Net Cash Flow 0.0 -79.2 12,128.9 121 147.5 1,742.2 12,806.6 121 Panel B Values in Percentage ROC 5.5 3.5 94.6 121 6.0 -43.5 42.6 121 EBIT margin 4.2 -0.5 316.0 121 2.8 8.0 89.9 121 Assets Turnover 81.6*** 194.6 414.9 121 132.4 396.4 240.8 121 Capex/Turnover 8.4*** 5.3* 35.3 121 1.7 -1.9 20.2 121

Net Debt/ Capital 32.7 36.0 84.2 121 28.5 49.2 52.8 121

Net Debt/ EBITDA 63.8 973.4 820.7 121 98.9 967.7 993.1 121

Net Cash Flow margin 0*** -49.3* 369.5 121 4.5 11.5 910.6 121 Financial Dependence 58.2*** -1,080.2 10,072.2 121 -50.3 -1,391.5 5,481.4 121

Sample Benchmark

26 5. Impact of PE Buyouts on the Target Companies Operating Performance

5.1. Growth and Investment

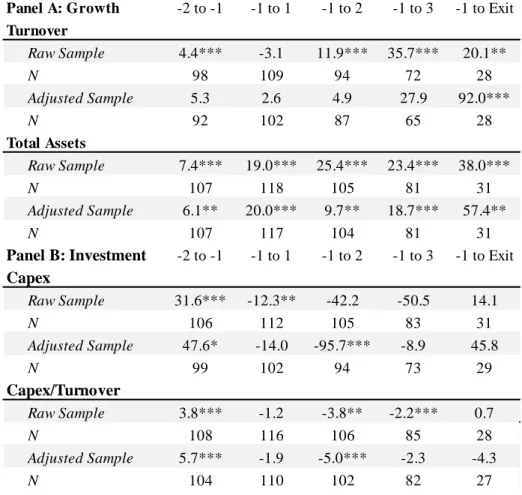

As shown is Table 7 - Panel A, the median PE backed firm in our sample presents an increasing turnover trend in the year preceding the buyout (statistically significant at 1% level). After a small contraction immediately after the buyout, in the second and third post-buyout years, PE backed firms’ median turnover rebounds and grows significantly. In fact, until the pre-exit year PE backed firms increase its median turnover in 20%, or 92% when adjusted for the match firms, both statistically significant at 1% level.

This table reports the median percentage changes of growth (Panel A) and investment (Panel B) variables used in this study for both the sample companies and adjusted to the match sample. A Wilcoxon Sign Rank Test was performed to test whether the median percentage value is significantly different from zero. The adjusted median change is given by the median of sample firms change subtracted by the comparable firms change. The table presents the change of the first, second, and third year after the transaction and last year before the exit, in relation to the year before the transaction. We use ***, **, and * to denote significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level (two-sided), respectively.

Table 7 - Growth and Investment Change After the PE Entry

Table 13 - Operating Efficiency Change After EntryTable 14 - Growth and Investment Change After the PE Entry

Panel A: Growth -2 to -1 -1 to 1 -1 to 2 -1 to 3 -1 to Exit

Turnover Raw Sample 4.4*** -3.1 11.9*** 35.7*** 20.1** N 98 109 94 72 28 Adjusted Sample 5.3 2.6 4.9 27.9 92.0*** N 92 102 87 65 28 Total Assets Raw Sample 7.4*** 19.0*** 25.4*** 23.4*** 38.0*** N 107 118 105 81 31 Adjusted Sample 6.1** 20.0*** 9.7** 18.7*** 57.4** N 107 117 104 81 31

Panel B: Investment -2 to -1 -1 to 1 -1 to 2 -1 to 3 -1 to Exit

Capex Raw Sample 31.6*** -12.3** -42.2 -50.5 14.1 N 106 112 105 83 31 Adjusted Sample 47.6* -14.0 -95.7*** -8.9 45.8 N 99 102 94 73 29 Capex/Turnover Raw Sample 3.8*** -1.2 -3.8** -2.2*** 0.7 N 108 116 106 85 28 Adjusted Sample 5.7*** -1.9 -5.0*** -2.3 -4.3 N 104 110 102 82 27