ESCOLA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO DE EMPRESAS DE SÃO PAULO

YONG JU SHIM

MANUFACTURING EMERGING ECONOMY FIRMS IN EXPORT MARKETS

SÃO PAULO 2016

MANUFACTURING EMERGING ECONOMY FIRMS IN EXPORT MARKETS

Tese apresentada à Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getúlio Vargas, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Administração de Empresas.

Campo do Conhecimento: Estratégia Empresarial

Orientador:: Prof. Dr. Paulo Roberto Arvate

SÃO PAULO 2016

Shim, Yong Ju.

Manufacturing emerging economy firms in export markets / Yong Ju Shim. - 2016.

51 f.

Orientador: Paulo Roberto Arvate

Tese (doutorado) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo.

1. Relações econômicas internacionais. 2. Globalização. 3. Subsídios governamentais (comércio exterior). 4. Administração de produção. 5. Exportação. I. Arvate, Paulo Roberto. II. Tese (doutorado) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. III. Título.

MANUFACTURING EMERGING ECONOMY FIRMS IN EXPORT MARKETS

Tese apresentada à Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getúlio Vargas, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Administração de Empresas.

Campo do Conhecimento: Estratégia Empresarial

Data da aprovação: 30/11/2016

BANCA EXAMINADORA

Prof. Dr. Paulo Roberto Arvate (Orientador) Fundação Getúlio Vargas (FGV)

Prof. Dr. Wlamir Gonçalves Xavier Eastern New Mexico University

Prof. Dr. Daniel Rottig Florida Gulf Coast University

Prof. Dr. Rodrigo Bandeira de Mello Merrimack College

Profa. Dra. Erica Piros Kovacs Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am thankful for the recommendations from the anonymous reviewers and panels of the Academy on International Business 2015/2016 Annual Meetings, Academy of Management 2015 Annual Meeting and National Graduate Association and Research in Administration (EnANPAD, Brazil) 2016 Annual Meeting, where this paper was named the second best in the Strategy Management Division. The original title of the paper was, “How Do Manufacturing Firms in Emerging Economies Become Exporters?”

This paper provides a new perspective on how manufacturing emerging economy firms (EEFs) achieve superior export performance. Unlike manufacturing developed economy firms that lack endowment problems, manufacturing EEFs only reach external markets by adding external resources (government support via subsidies) to their internal resources (R&D capabilities) to influence their internal environment (international patent production and export strategy development). I investigate 140 firms from four countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China) between 2008 and 2012 with data from an online survey. I establish relationships between the variables to guide the empirical development with structural equation modeling.

Keywords: Internationalization Theory, Emerging Economies, Government Support, R&D Capability, Export Performance.

Este artigo fornece uma nova perspectiva sobre como as empresas de manufaturas de economias emergentes (EEFs) conseguem alcançar desempenho superior nas exportações. Diferente das empresas de economias desenvolvidas que não tem problemas com dotação, as EEFs só chegam aos mercados externos adicionando recursos externos (apoio governamental através de subsídios), os seus recursos internos (capacidade de P&D) são para influenciar seu ambiente interno (produção de patentes internacionais e desenvolvimento de estratégias de exportação). Investigo 140 empresas de quatro países (Brasil, Rússia, Índia e China), entre os anos de 2008 e 2012, com dados obtidos por meio de um questionário online. Estabeleço relações entre as variáveis para orientar o desenvolvimento empírico com modelagem de equações estruturais.

Palavras-chave: Teoria da Internacionalização, Economias Emergentes, Apoio Governamental, Capacidade de P&D, Desempenho de Exportação.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 - Variable Description ... 21

Table 2 - Descriptive analysis ... 23

Table 3 - Correlation coefficient ... 24

CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ... 10 2 THEORY ... 11 2.1 R&D Capability ... 12 2.2 Government Support ... 15 3 METHODOLOGY ... 19

3.1 Data and sample ... 19

3.2 Measurement ... 25 3.3 Model Testing ... 25 4 RESULTS ... 26 4.1 Main Results ... 26 4.2 Alternative Models... 27 4.3 Bootstrap Results ... 28 5 DISCUSSION ... 28 6 CONCLUSION ... 30 REFERENCE ... 32 ANNEXS ... 44

1 INTRODUCTION

Firms are increasingly engaging in international business (ANDERSSON; GABRIELSSON; WICTOR, 2004; CASILLAS; ACEDO, 2013; CAVUSGIL; KNIGHT, 2015), and scholars’ interest in their internationalization has grown accordingly (WELCH; PAAVILAINEN-MÄNTYMÄKI, 2014). Internationalization is defined as “the process in which firms increase their involvements in international operations” (WELCH; LUOSTARINEN, 1988) and “the process of adapting firms’ operations (strategy, structure, resource) to international environments”, according to Calof and Beamish (1995).

Despite the lack of a clear agreement on the advantages and disadvantages of internationalization (HASSEL et al., 2003), it is apparent that internationalization is an inevitable trend (ZAIN; NG, 2006). If a firm does not internationalize, another foreign firm may do so to compete in the local market, or a local competitor may seize the opportunity instead. Thus, firms can no longer afford to avoid internationalization.

There are four major theories that focus on firm internationalization: process (Uppsala) theory (JOHANSON; VAHLNE, 1990; JOHANSON; VAHLNE, 1977), network theory (JOHANSON; MATTSSON, 2015), international entrepreneurship theory (OVIATT; MCDOUGALL, 1994) and the eclectic paradigm (DUNNING, 1979). Each approach presents a unique way of understanding the internationalization process and its motivating factors (AXINN; MATTHYSSENS, 2002).

There is no consensus, however, on the applicability of such theories in emerging economy firms (EEF), since they were designed to explain the behavior of developed economy firms (DEF) (CHILD; RODRIGUES, 2005, KUNDU; KATZ, 2003; PENG; WANG; JIANG, 2008, RAMAMURTI, 2012, x XU; MEYER, 2013, YOUNG et al., 2014). The lack of applicability of such theories in emerging economies is also based on the precarious conditions under which EEF operate, as well as their internal limitations (AULAKH; ROTATE; TEEGEN, 2000, XU; MEYER, 2013, YAMAKAWA; PENG; DEEDS, 2008, YOUNG et al., 2014). Those conditions include inefficient capital markets, limited intellectual rights protection, an unskilled workforce, inadequate infrastructure and a low level of R&D capability, just to name a few. In this article, I suggest a model based on two

complementary mechanisms that explain manufacturing EEF’s superior export performance. In this sense, EEF’s internal limitations and precarious conditions can be offset to achieve superior export performance.

I developed a new model for how manufacturing EEF achieve superior export performance, arguing that internal resources (R&D capability via budget) are a limiting factor for EEF reaching the external market through their internal drivers (technical innovation through the production of international patents and a willingness to export ) without external resources (government support via subsidies).

This paper contributes to the literature on internationalization theory first by showing that, in emerging economies, government support may trigger and enhance the internationalization of EEF via exports by offsetting some restrictions, including limited R&D capability. Since the majority of literature on export performance relies on a firm’s own capabilities of developing competitive products (AABY; SLATER, 1989, KATSIKEAS; LEONIDOU; MORGAN, 2000, SOUSA; MARTÍNEZ-LÓPEZ; COELHO, 2008), my model provides an alternate explanation for the superior export performance of manufacturing EEF. This paper also contributes to the literature by identifying two drivers (technological innovation and willingness to export) that mediate government support and R&D capability on export performance. Especially in the case of a willingness to export, this study highlights the pivotal role of strategic decisions triggered by willingness to export rather than the standard, natural flow of starting and expanding exports.

The following section soutline the model development, hypotheses, empirical strategy and results of the analysis. The paper concludes with a discussion of the findings and direction for future research.

2 THEORY

I developed a conceptual model to explain the mechanism of a firm’s export performance in emerging economies. Since a combination of causes often provides better explanatory power than a causal model (VAN BOUWEL; WEBER, 2002), I tried to identify more than one cause affecting the export performance in an emerging economy firm,

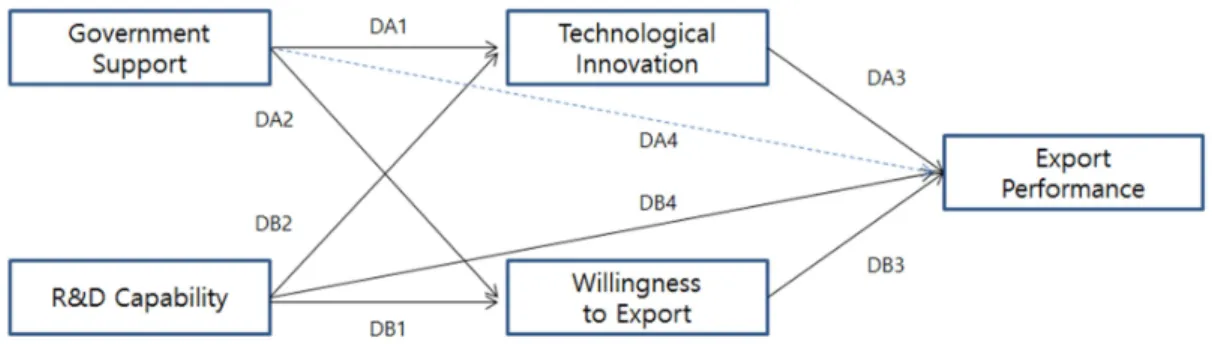

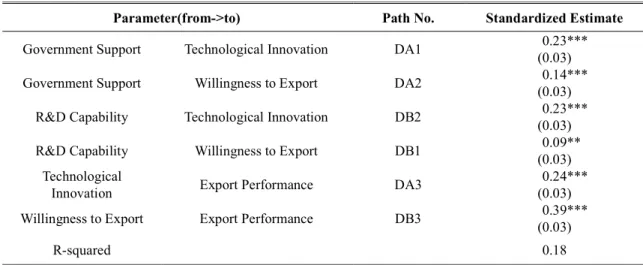

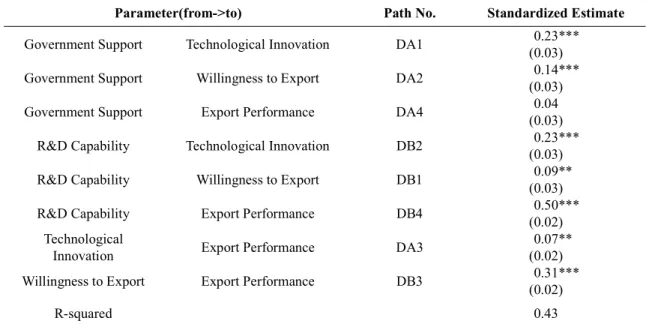

identifying R&D capability and government support as principal causes from the literature. I also identified two commitments (technological innovation and willingness to export) that mediate this process (DUNNING, 1979). I tried to test various sub-models to select the most optimal model. In the empirical section, I will discuss the detailed process for reaching the optimal model. Figure 1 shows the relationship between variables in the main model that passed the empirical test.

Figure 1 - Empirical model for path analysis

Source: Elaborated by the author

A detailed exposition of the hypotheses that constitutes the model follows.

2.1 R&D Capability

Hypothesis DB1: R&D capability increases a firm’s willingness to export.

Some studies have attempted to categorize firms into subgroups based on their willingness to export. Pavord and Bogart (1975) identified four such groups: no activity, passive activity, minor activity and aggressive activity. Czinkota and Johnston (1981) also divided firms into six subgroups according to their willingness to export: unwilling firms, uninterested firms, interested firms, experimenting exporters, semi-experienced small exporters and experienced larger exporters. According to such studies, the decision to export may not be automatic, as argued by process theory. To be an exporting firm, its management must make a strategic decision (a product of its willingness to export), all other conditions

being equal (GANOTAKIS; LOVE, 2012).

International entrepreneurship theory (e.g., AXINN et al., 1995, KUNDU; KATZ, 2003; COOMBS; SADRIEH; ANNAVARJULA, 2009) and other related studies on exports (e.g., JAFFE; PASTERNAK, 1994, MORGAN; KATSIKEAS, 1997) have attempted to reveal the factors that increase a firm’s willingness to export. In this work, the role of R&D stands out in particular, given the trend among firms to increase their willingness to export as a natural and logical product of an increase in certain resources, such as R&D. Smith, Madsen and Dilling-Hansen (2002) argued that investments in R&D positively influence a firm’s willingness to enter export markets, pointing out that R&D investment requires a larger market to compensate for its spending, and exporting is only way to recoup the investment in R&D. In other words, reaching a certain level of competitiveness requires a significant amount of resources; devoting those resources only in the domestic market is neither a rational nor economic strategy for firm. Thus, firms that invest in R&D are more willing to export than those that do not. Moreover, R&D can lead a firm to the technological forefront of the industry and produces a comparative advantage in both developing and developed countries. A firm that recognizes its competiveness in foreign markets naturally increases its willingness to export, as it no longer has to fear competitors. In a similar context, R&D enhances a firm’s understanding of technology (BUCKLEY; CARTER, 2004) and helps it recognize competitive gaps in the global technological landscape (MILLER; FERN; CARDINAL, 2007). R&D also increases a firm’s willingness to export by reducing fear and risk perception about entering foreign markets. Additionally, Atuahene-Gima (1995) has argued that the R&D process should entail international orientation; more frequent and intensive exposure to an international environment also reduces the fear of foreign markets and increases a firm’s willingness to export. Based on these arguments, I propose DB1.

Hypothesis DB2: R&D capability increases technological innovation.

R&D capability and technological innovation has been discussed thoroughly in the literature (e.g., NELSON, 1991; BERCHICCI, 2013, HALL; LOTTI; MAIRESSE, 2013). Hall, Lotti, and Mairesse (2013) demonstrated that low R&D investment is the main cause of underperformance of innovation in Europe, compared to a US dataset. Mudambi and Swift

(2014) argue that consistent R&D investment facilitates innovation; increasing R&D spending is linked with an increased likelihood of a highly cited patent. Love and Roper (1999) identify R&D capability as a key determinant of technological innovation, which leads to superior performance in both domestic and international markets. In light of these studies, I propose hypothesis DB2.

Hypothesis DB3: Willingness to export increases export performance.

While existing scholarship indicates many factors affecting export performance (e.g., ZOU; STAN, 1998; SOUSA; MARTÍNEZ-LÓPEZ; COELHO, 2008; CHEPTEA; FONTAGNÉ; ZIGNAGO, 2014; CHEN; SOUSA; HE, 2016), the so-called “willingness to export” is one of the most crucial and strategic aspects. Global competitiveness may be a necessary condition for exports and further growth, but it is not a sufficient condition. A willingness to export is the first step for non-exporting firms and helps to fortify and enhance existing export intensity despite various obstacles (MORGAN; KATSIKEAS, 1997). Internationalization always comes with internal obstacles (insufficient resources) and external ones (risk of no-payment and excessive competition). A lack of infrastructural facilities and (non) tariff barriers are additional barriers (LEONIDOU, 2004). Under such circumstance, non-exporters may abandon their desire to involve themselves in the export market. A novice exporter may feel scared and withdraw from the international market. Even a very experienced exporter could be opposed to further expansion in the face of significant costs and risks related to the export market (LEONIDOU; KATSIKEAS, 1996). In the same context, Ganotakis and Love (2012) have emphasized that, “In the case of the exporting decision, attitudes and perceptions of the risks and costs associated with exporting that are among the main determinants behind a strategic decision to become an exporter”. Morgan and Katsikeas (1997) also argued that, “Firms exhibiting a strong intention to export will be those most likely to proceed successfully to export initiation and development”. This proposition seems natural and consistent with the work of Dosoglu-Guner (1999) on the causal relationship between a firm’s willingness to export and its performance. Tesar and Tarleton (1982) discussed firm export performance and argued that firms with a greater willingness to export show better export performance through an empirical comparison

among small and medium American firms. I propose this hypothesis in light of such arguments.

Hypothesis DB4: R&D capability increases export performance

In line with a resource-based view (RBV), the literature broadly argues that R&D capability is associated with firm performance as well as export performance (e.g., DHANARAJ; BEAMISH, 2003; YI; WANG; KAFOUROS, 2013). In addition to the RBV approach, Ito and Pucik (1993) proved that there is a causal relationship between a firm’s R&D expenditures and various performance measures. Empirically, such a direct relationship has been established in a number of studies. Gourlay, Seaton and Suppakitjarak (2005) used firm-level data from UK service firms to show that R&D directly increase export performance. Dhanaraj and Beamish (2003) also demonstrated the positive influence of R&D on a firm’s internationalization through analysis of Canadian and US firm-level data. Such positive relationships between R&D and export intensity have even been empirically proven in a supply-dominated industry through small- and medium-firm data from Italy (STERLACCHINI, 1999). Thus, I propose this hypothesis based on above-mentioned arguments and empirical evidence proving the role of R&D capabilities on export performance.

I have explained, in the context of export processes and performance, the relationship between R&D capability, export performance, technological innovation and a firm’s willingness to export (JOHANSON; VAHLNE, 1977; JOHANSON; VAHLNE, 1990). I have also proposed related hypotheses. Notably, this theoretical framework is valid for any firm that seeks to internationalize via exports independent from the developmental stage of the country, since R&D capability is pivotal for export performance.

2.2 Government Support

The mechanisms related to R&D capability described in the previous section do not completely explain the recent export performance of EEF, as it is apparent that EEF’s R&D capability is generally more limited than that of DEF (AULAKH; ROTATE; TEEGEN,

2000, YAMAKAWA; PENG; DEEDS, 2008; RAMAMURTI, 2009, RAMAMURTI, 2012, XIAOBAO; WEI; YUZHEN, 2013). Considering firm size, age and other internal firm characteristics, EEF have relatively limited R&D capabilities for innovation (HALLAK;SIVADASAN, 2009), which is a key driver of export performance for DEF. Additionally, EEF face another external problem. Since developing economies tend to have limited intellectual property protection and regulation, EEF may reduce investments in technological innovation, which lowers their chance of achieving international competitiveness (FLYER; SHAVER, 2003, HALL; LERNER, 2010; CHARI; DAVID, 2012; LIPUMA; NEWBERT; DOH, 2013). In a similar context, considering the low success rate of R&D activities, EEF with smaller resources and fewer experiences may be less likely to engage in R&D compared to DEF (FILATOTCHEV et al., 2007, KLETTE; MØEN; GRILICHES, 2000; SCHILLING, 2002).

Considering these limits of EEF, I identified government support as another driver for enhancing export performance in an emerging economy setting. Grosse and Behrman (1992) illustrate this role of government in international business.

Historically, emerging economies suffer more frequently and seriously from external shocks than developed economies due to their backward market structure and fragile financial system (ARELLANO, 2008; CALDERÓN; FUENTES, 2010; CETORELLI; GOLDBERG, 2011). If the governments of countries with emerging economies do not actively intervene, economic players will suffer too much from external turbulence (SKOUFIAS, 2003; AFONSO; FURCERI, 2010). Thus, governmental intervention in such economies is natural and even crucial for the survival of market players. In some cases, the governments of emerging economies aggressively subsidize initiatives for technological development (WU; CHEN, 2014) and export, which ultimately benefits the whole economy.

A government’s basic objective is to maximize the welfare of individuals in society, while firms look to maximize economic profit. At first glance, government and firms seem to have different ends. However, the distinct targets of each can be harmonized if the government realizes that trade surpluses are crucial for economic development and the welfare of individuals and that firms are the only market players that can bring a trade surplus directly to the economy. In this context, the government is incentivized to use its resources to

help firms; such subsidies may in turn bring reciprocal benefits (GROSSE; BEHRMAN, 1992).

A subsidy is a political instrument generally used by governments to pursue their political objectives1. In emerging economies, governments may use subsidies to alleviate institutional disadvantages that hinder local firms’ competitiveness in both domestic and international markets. As Hujer and Radić (2005) have noted, emerging economies generate limited innovation without external subsidies or incentives, and those incentives may substitute for internal R&D capability. Thus, I identify government support as another driver that may boost the export performance of EEF2. From my perspective, the literature on internationalization has not yet fully appreciated the role of government support3, which is

my major contribution to the field.

Through subsidies, firms become more competitive by reducing their costs in the export market. The effect of subsidies will be same as the cost required to generate or borrow new technologies. When firms receive such government support, they may even become as competitive as DEF. The subsidy stimulates the internal capabilities and interest of firms to export (production of international patents and development of an export strategy).

Hypothesis DA1: Government support increases technological innovation.

Some scholars (e.g., WALLSTEN, 2000) argue that government R&D subsidies can crowd out privately funded R&D investments and decrease innovative output. For

1 In addition to such arguments, in emerging economies, the lack of relevant stakeholders acting as

intermediaries (see: KHANNA, T.; PALEPU, K. Winning in emerging markets: A road map for strategy and execution: Harvard Business Press, 2013) leads the government to function as a key agent for providing incentives. Such incentives can also help firm performance.

2 Artificial devaluation of local currency is also a kind of subsidy provided by the government to EEF

and is equally important to a firm’s export performance. Such devaluation of local currency enhances the terms of trade and increases exports. In a similar context, a double exchange rate system is also used. In this system, firms buy imported parts and components at a more competitive price and still enjoy the devaluation of local currency for better terms of trade. However, we focus only on the effects of direct subsidies due to the limits on observing the function of such exchange regimes in a firm (see: GROSSE, R.; BEHRMAN, J. N. Theory in international business. Transnational Corporations, v. 1, n. 1, p. 93-126, 1992).

3 The literature on firm internationalization has already shown the government’s pivotal role in

attracting FDI (DUNNING, 1979); however, the case of government support in the form of a subsidy is limited.

example, according to Goolsbee (1998), increases in funding for public R&D significantly raise the wages of scientists and engineers. Scientists and engineers are the major beneficiaries of government R&D support; by increasing the cost of salaries for private laboratories, government R&D crowds out private R&D.

In his empirical research, however, Levy (1990) argues that government R&D has effectively replaced private R&D investment in only two countries and complements it in five others. Feldman and Kelley (2006) have also shown that public R&D input increases R&D input from other sources comparing to firms that receive non-governmental funding. Almus and Czarnitzki (2003) have used data from Eastern Germany to demonstrate empirically that publically funded firms increase innovation activity compared to those that do not receive government funds. Furthermore, recent meta-analysis of this issue could not identify any crowding-out effect (GARCÍA-QUEVEDO, 2004). Thus, I would like to suggest that, as long as corruption and misuse of funds are controlled, government support for a firm’s R&D is crucial for EEF, which generally suffer from a lack R&D funding. This serves the same function for technological innovation as a firm’s capability of investing in its R&D.

Hypothesis DA2: Government support increases a firm’s willingness to export.

A number of recent studies on the effect of government export subsidies investigate the role of the recipient firm in the export market (e.g., FREIXANET, 2012; CADOT et al., 2015; LEONIDOU; SAMIEE; GELDRES, 2015). Recent literatures shows that both general purpose and R&D subsidies can reduce the costs and risk related to export activity, increasing firms’ willingness to export by removing market barriers (GÖRG; HENRY; STROBL, 2008). Girma, Görg, and Wagner (2009) also used German firm-level data to prove a causal relationship between subsidies and an increase in exports. A similar study used Chinese firm-level data to prove empirically that production subsidies stimulate export activity (GIRMA et al., 2006).

Hypothesis DA3: Technological innovation increases export performance.

The literature has repeatedly addressed the positive relationship between technological innovation and firm performance (e.g., WANG; WANG, 2012; ATALAY;

ANAFARTA; SARVAN, 2013; HUNG; CHOU, 2013). I suggest that technological innovation has a similar influence on export performance, as it is also part of a firm’s performance and can be achieved through competitiveness.

Arbix, Salerno, and De Negri (2004) have argued that internationalized firms with a focus on technological innovation tend to obtain greater returns and further expand into export markets, which leads to a superior export performance. Guan and Ma (2003) use Chinese firm data to suggest that export growth is positively related to the total improvement of innovation and that productivity growth also increases export performance. Kumar and Siddharthan (1994) used Indian firm-level data to show that technology gained by innovation is crucial for a firm’s export behavior. In line with such studies, I propose that technological innovation is positively associated with export output.

Hypothesis DA4: Government support increases export performance.

From my perspective, the direct impact of government subsidies on a recipient firm’s export performance has not yet been clearly proven, though the literature has already discussed extensively the effect of direct support on a firm’s export performance (e.g., BADINGER; URL, 2013; CADOT et al., 2015, LEONIDOU; SAMIEE; GELDRES, 2015). However, Luo et al. (2016) recently used Chinese firm data to show the direct relationship between general subsidies and export performance. I propose the hypothesis above to check the existence of such direct path.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Data and sample

I tested the model with five-year panel data acquired through a survey submitted to emerging market manufacturing firms in Brazil, China, India and Russia. The questionnaire sought to obtain relevant firm-level variables (see Table 1) that represent each factor in the model as well as some control variables. The questionnaire was pretested twice:

in September 2014, a group of 20 undergraduate students answered the survey and provided feedback to improve the questionnaire. In addition, in October 2014, a group of 28 manufacturing firms from India also received the revised version of the survey for the same purpose.

Table 1 - Variable Description

Variable Definition Question Style Type Range Coding

R&D Capability R&D budget /

total budget ratio Please put annual 'R&D budget / total budget' ratio for last 5 years. yearly discrete 0,1,2,…10

0%=0, 1~10%=1, 11~20%=2,…91~100%=10 Governmental

Support

Subsidy / total budget' ratio for

year

If your company has received financial support from government, please put 'subsidy / total budget' ratio for

each year. yearly discrete 0,1,2,…10 11~20%=2,…91~100%=10 0%=0, 1~10%=1, Technological Innovation Number of international invention patent

How many international patents (invention only) do you have for last five years?

yearly continuous unlimited - Willingness to

Export Attitude toward export How about your company's strategic attitude toward export? fixed discrete 0,1,2,3

Very Negative=0, Negative=1, Positive=2 Very

Positive=3 Export

Performance

Annual ratio of export sales to

total sales Please put 'export sales / total sales' ratio for last 5 years

yearly discrete 0,1,2,..10 11~20%=2,…91~100%=10 0%=0, 1~10%=1, Firm Age Foundation year

When your company has been founded? yearly continuous unlimited

-

Firm Size Number of employees How many employees does your firm have for each

year? fixed continuous unlimited -

Corruption corruption in Level of host country

Gained from secondary data

(transparency.org) yearly discrete 0,1,2,…10 -

Public Ownership Existence of government

share Does your company have government share? yearly discrete 0,1 No=0, Yes=1 Exchange Rate Annual

Exchange Rate

Gained from secondary data

(worldbank.org) yearly continuous unlimited -

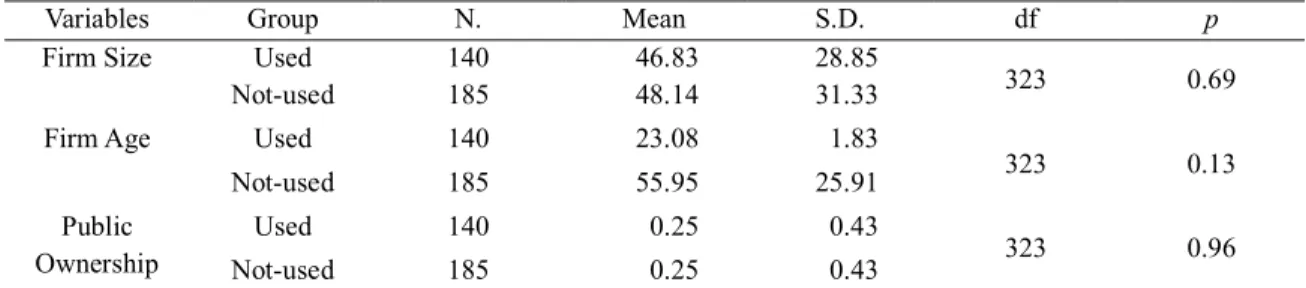

In October 2014, I sent out the questionnaire to 7,842 firms in four major emerging economies: Brazil, Russia, India and China. I obtained contact information for the firms through the EMIS database (www.emis.com). The questionnaire was originally prepared in English and then translated to Portuguese, Chinese and Russian. After pretesting and adjusting the three translated versions, I then back-translated the questionnaire to English and made further adjustments. The translations of the Chinese and Portuguese questionnaires were conducted by native speakers, both scholars with a PhD, under the supervision of the author. Two experienced linguists translated the Russian version. The questionnaire was administered online using a web-based survey platform (Survey Monkey) and addressed the period 2008-2012. I initially collected questionnaires from 420 respondents. However, after removing in valid responses, I was ultimately left with 140 responses: 12 Brazilian, 40 Russian, 55 Indian and 33 Chinese firms, a response rate of 1.7% after rejecting 280 incomplete questionnaires or disqualified respondents (non-high level managers). This ultimately yielded 700 observations (140 firms for 5 years). Tables 2 and 3 provide a descriptive analysis and Pearson’s correlation matrix of all variables. The t-test for checking the potential sample selection bias has also been performed.

The results from Table 2 show that firms from Russia and India are very different from other firms in the sample of observable characteristics. Most variables from Russian firms are below average for the sample (see, for instance, R&D Capability, Governmental Support, Technological Innovation, Willingness to Export, Export Performance and Firm Size). On the other hand, Indian firms are above average (see, for instance, R&D Capability, Willingness to Export, Export Performance, Firm Age and Firm Size). Firms from Brazil and China are closer to the average. Notably, Brazilian firms have a higher level of Technological Innovation (31.51 compared to 8.26 on average for the sample).

Table 2 - Descriptive analysis

Full Sample Brazil Russia India China

Variable Obs. Mean Obs. Mean Obs. Mean Obs. Mean Obs. Mean

R&D Capability 700 (2.51) 3.60 60 5.56*** (2.42) 200 2.75*** (2.44) 275 3.88* (2.60) 165 3.46 (1.95) Governmental Support 700 7.08 (12.85) 60 5.01 (8.17) 200 4.74** (9.79) 275 7.64 (13.76) 165 9.76** (15.21) Technological Innovation 700 (33.39) 8.26 60 31.51*** (94.47) 200 0.95*** (4.95) 275 8.69 (20.02) 165 7.96 (24.08) Willingness to Export 700 (0.79) 1.95 60 1.83 (0.80) 200 1.32*** (0.60) 275 2.21*** (0.68) 165 2.33*** (0.68) Export Performance 700 (2.72) 3.55 60 4.13* (2.99) 200 1.90*** (2.35) 275 4.62*** (2.56) 165 3.54 (2.31) Firm Age 700 (21.08) 24.08 60 22.58 (16.57) 200 (22.47) 25.10 275 29.4*** (24.86) 165 14.54*** (10.07) Firm Size 700 (11,037.23) 2.607.65 60 (2,743.15) 1.530.00 200 (2,843.94) 1,423.22* 275 (16.740.11) 3.909.76** 165 2,265.03 (5,780.38) Corruption 20 (0.58) 3.16 5 (0.27) 3.8 5 2.32 (0.26) 5 2.32 (0.26) 5 3.64 (0.13) Public Ownership 20 (0.43) 0.25 5 0.25 (0.43) 5 0.27 (0.44) 5 0.27 (0.44) 5 0.24 (0.42) Exchange Rate 20 (0.14) 0.45 5 0.75 (0.08) 5 0.54 (0.05) 5 0.54 (0.05) 5 0.50 (0.04) Source: Elaborated by the author

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. For each country, the t-statistic is the difference between the country average and the average from all 4 countries in the sample (only for firm-level variables).The number of observations for firm-level data is 700, since we have five periods of yearly data for 140 firms.

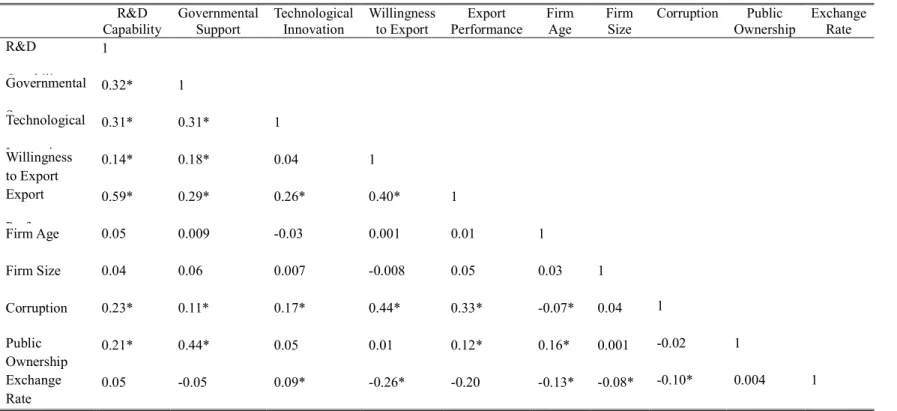

Table 3 - Correlation coefficient R&D Capability Governmental Support Technological Innovation Willingness to Export Export Performance Firm Age Firm Size Corruption Public Ownership Exchange Rate R&D Capability 1 Governmental Support 0.32* 1 Technological Innovation 0.31* 0.31* 1 Willingness to Export 0.14* 0.18* 0.04 1 Export Performance 0.59* 0.29* 0.26* 0.40* 1 Firm Age 0.05 0.009 -0.03 0.001 0.01 1 Firm Size 0.04 0.06 0.007 -0.008 0.05 0.03 1 Corruption 0.23* 0.11* 0.17* 0.44* 0.33* -0.07* 0.04 1 Public Ownership 0.21* 0.44* 0.05 0.01 0.12* 0.16* 0.001 -0.02 1 Exchange Rate 0.05 -0.05 0.09* -0.26* -0.20 -0.13* -0.08* -0.10* 0.004 1 Source: Elaborated by the author

3.2 Measurement

Previous studies have used subsidy intensity as a measure of subsidy size, calculated as a percentage of the funding level to the total R&D budget (LACH, 2002; GÖRG; HENRY; STROBL, 2008). In this study, I did not limit the funding only to R&D subsidies but included any government funding, as outlined in Table 1, to check the effect of overall government support on a firm’s activity and behavior. Table 1 provides a detailed description of the measurement method of all variables used in this paper. In this research, I used R&D intensity as a proxy for R&D capability (KOTABE; SRINIVASAN; AULAKH, 2002).

Technological innovation can be measured in several ways. The most widely used measures are the number of patents (HAGEDOORN; CLOODT, 2003), the number of new products or patents introduced to the market (KLEINKNECHT; VAN MONTFORT; BROUWER, 2002) and multi-variable indicators (LANJOUW; SCHANKERMAN, 2004). Given the simplicity and ease of acquiring the data, the number of patents is the most widely used measure in the field (ACS; ANSELIN; VARGA, 2002; HAGEDOORN; CLOODT, 2003; POPP, 2010; JOHNSTONE; HAŠČIČ). Despite some critics questioning its validity (BASBERG, 1987), I used it in my study as well.

Willingness to export was measured on a 4-point Likert scale, with participants asked to evaluate how the firm views the export market (1=strongly negative; 4=very positive).

Export performance was measured by an export intensity ratio (COOPER; KLEINSCHMIDT, 1985; AABY; SLATER, 1989; MAJOCCHI; BACCHIOCCHI; MAYRHOFER, 2005). Finally, I assessed firm size by the number of current employees (KUMAR; SIDDHARTHAN, 1994) and firm age based on the number of years since the creation of the firm (BECCHETTI; ROSSI, 2000). Both age and size were included as controls because these firm characteristics are considered important factors that influence activity and behavior (ALMUS; NERLINGER, 1999; HENDRICKS; SINGHAL, 2001). Furthermore, some external variables (i.e., corruption level, public ownership and exchange rate) were also used to test the robustness of the model.

3.3 Model Testing

(SEM) approach. SEM allowed me to estimate various equations simultaneously as my theoretical model requires. Other methodologies have constraints for such estimations (WESTON; GORE, 2006). Since my model encompasses two independent variables and variables that act as mediators, SEM was the most appropriate empirical choice to test such a multifaceted relationship (CHENG, 2001; BAGOZZI; YI, 2012). I examined the paths with a maximum likelihood estimator.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Main Results

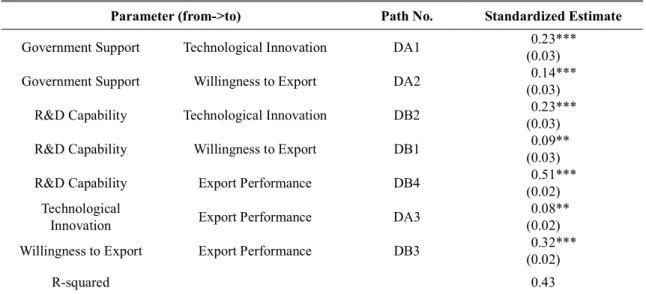

Table 4 and Table A2-A4 show the path analysis results of various sub-models. To obtain the empirically best fitting model, I tested several sub-settings, including the original model (Table A4), and discovered that one of the sub-models (hereafter the ‘ultimate model’) with only one direct path between R&D capability and export performance (Table 4) shows the best empirical results4. Thus, I mainly address the ultimate model rather than the original model. The code in the column “path number” as well as hypothesis name (e.g., DA1, DA2) corresponds to those paths in Figure 1.

4 I brought one of the submodels into the ultimate model due to path DA4. As seen in Table A4, for

the original model with both direct paths (DA4 and DB4), DA4 did not yield statistical significance despite proper causal directions. GOF is also questionable since it is just fitted. Excluding both direct pathes also resulted in a non-acceptable GOF, as seen in Table A2, and the model with only DA4 also yielded an unacceptable GOF. Given the empirical resuts of all submodels, among the 8 hypotheses based on the original model I proposed, H8 is not supported empirically, so I decided to modify my original model to have only one direct path between R&D capability and export performance. Unlike direct paths, mediated paths show strong statistical significance in any subsetting.

Table 4 - Main results (ultimate model)

Parameter (from->to) Path No. Standardized Estimate Government Support Technological Innovation DA1 (0.03) 0.23*** Government Support Willingness to Export DA2 (0.03) 0.14*** R&D Capability Technological Innovation DB2 (0.03) 0.23***

R&D Capability Willingness to Export DB1 0.09**

(0.03)

R&D Capability Export Performance DB4 0.51***

(0.02) Technological

Innovation Export Performance DA3

0.08** (0.02) Willingness to Export Export Performance DB3 (0.02) 0.32***

R-squared 0.43

Source: Elaborated by the author

Note:χ (2) = 3.11, =0.21, RMSEA=0.02, CFI=0.99, TLI=0.99, SRMR=0.01. ** p< 0.05; *** p< 0.01, standard errors in parenthesis.

As we can see from Table 4, my empirical results are consistent with most of my hypotheses. Path No. DB1 (R&D Capability => Willingness to Export) and DB3 (Willingness to Export => Export Performance) are all positive and statistically significant (0.23, p<0.01 and 0.32, p<0.01). Path No. DB2 (R&D Capability => Technological Innovation) and DA3 (Technological Innovation => Export Performance) are also all positive and statistically significant at 1 and 5% (0.23, p<0.01 and 0.08, p<0.05). DB4 also shows a positive sign with proper statistical significance (0.51, p<0.01). Path analysis results show that Hypothesis DB1, DB2, DB3, DB4 and DA3 are also supported empirically.

The relationship between Government Support and Technological Innovation (DA1) and Government Support and Willingness to Export (DA2) are all positive at 1% of statistical significance (0.23, p<0.01 and 0.14, p<0.01), and DA3 and DB3 are the same as R&D capability cases since they share common paths, thus confirming the hypotheses. The model fit also shows an acceptable level (χ (2) = 3.11, =0.21, RMSEA=0.02, CFI=0.99, TLI=0.99, SRMR=0.10).

4.2 Alternative Models

(Tables A2 and A3) as well as my original model (shown in Table A4) to enhance the robustness of my empirical procedures. However, neither the alternative models nor the original model showed a better fit than the ultimate model.

I also tested the ultimate model with two additional groups of control variables (firm-specific control variables: firm size and age; external control variables: corruption, public ownership and exchange rate) for selected variables as shown in Table A5-A7. The results of the alternative models with control variables are worse in terms of model fit than the ultimate model, even though some paths are statistically significant and show expected causal directions. In other words, no model with control variables shows better results than the ultimate model, which only confirms the robustness of the ultimate model.

4.3 Bootstrap Results

Given the lower number of observations, some discomfort with the standard errors and confidence intervals produced directly by SEM is understandable. Thus, I completed the estimation of Table 4 (ultimate model) again with bootstrap methodology. The replication number was 200, and the process yielded similar results to the base model with robust standard errors (Table A8).

5 DISCUSSION

My model is based on the notion that internal and external perspectives are both supplementary in explaining the internationalization of EEFi. The empirical results seem to support such a composite framework.

Eclectic theory (as an instance of ownership advantage) and the resource-based view (as a key capability) have already addressed the positive effect of R&D capability on export performance. Hypotheses DB1, DB2, DB3, DB4 and DA3 are in line with this argument and are empirically supported through firm-level survey data from four major emerging economies.

Indeed, Madhok and Keyhani (2012) have argued that EEF embrace unique features that distinguish them from DEF, such as their historical heritage and institutional aspects. Xu and Meyer (2013) contend that an emerging market is distinct in terms of inefficient markets,

active government involvement and high uncertainty. In line with such an argument, and considering the current situation of EEF, if we look at EEF more closely, we may doubt the absolute role of R&D capability in its internalization via export, which suggests that we should look for other causes that can fortify and even substitute the role of a firm’s own R&D capability.

Ramamurti (2012) showed that EEF are characterized by technological backwardness from an internal analysis perspective. Thite, Wilkinson, and Shah (2012) argued that EEF are comparatively smaller, less experienced and less resourceful than DEFs. Indeed, such analysis on the differences between EEF and DEF can be summarized by the former’s limited availability of resources and inferior support for attaining international competitiveness. The eclectic model already demonstrated the importance of ownership advantage but did not seriously consider EEF’s inability to achieve such advantage. As most of a firm’s internalization model is based on DEF rather than EEF, such relative ignorance of EEF would be natural. However, the rise of EEF raises a new question regarding firms that cannot achieve such competitiveness on their own.

By importing the well-developed discussion of the role of government (e.g., ROTTIG; ROTTIG, 2016; IYER, 2016) into the theory of internationalization, I was able to solve the problem of a firm’s inability to use its internal capability to build international competitiveness. While this argument lends validity to Hypothesis DA1, DA2, DA3, DA4andDB3, only Hypothesis DA4 is not supported empirically.

The identification of two moderators, technological innovation and willingness to export, is crucial. Technological innovation as a product and moderator of R&D capability is very apparent. However, it is worth noting that it can also be achieved through government support, which reduces the costs and risks associated with innovation and directly relieves the burden of production cost. Government support is not only limited to financial subsidy but also can be any type of technical support and even the free use of government R&D results. Such support can enable a firm to achieve the necessary level of technological innovation to become internationally competitive.

Another important factor is the willingness to export. Firm internationalization theories generally see the process of internationalization via export as a natural development and an autonomous decision of the firm’s management. Consequently, outside of international entrepreneurship theory, a firm’s willingness to export was not investigated thoroughly.

However, considering the significant competition and lack of experience in an export market, it does not follow that an EEF would automatically internationalize. Consequently, I include that the willingness to export is a product of two causes and a mediator for the whole export process, which provides greater logic to the model. It is also largely in line with international entrepreneurship theory. Notably, my model did not consider other possible drivers for the willingness to export, such as the characteristics and experience of the entrepreneurial founding team, as Ganotakis and Love (2012) attest.

During the empirical analysis, one hypothesis (Hypothesis DA4) was not proven empirically, and the sub-model without the direct path between government support and export performance became the ultimate model. However, this does not affect the validity of the entire model. Such process can be understood as an inevitable and rather essential part of research.

In addition to theory formation, in terms of empirical analysis, I tried to fulfill the recommendations of Cuervo-Cazurra et al. (2016) to maximize the trustworthiness of my findings. The matter of control variables and theory boundary met this guideline. The only concern is my use of the control group for comparison, though the necessity of such an approach was minimized by the existing literature that already revealed the gap between EEF and DEF. Furthermore, I do not claim that DEF have no need for government support, but that it is more crucial for EEF’s success in the export market, given the existing gaps.

6 CONCLUSION

Exports have the important function of helping developing economies catch up with others (DOMINGUEZ; SEQUEIRA, 1993). The extant literature provides sound knowledge about EEF’s export behavior and the determinants of export performance. Nevertheless, several critics have noted our insufficient knowledge on the behavior of firms from emerging economies (AULAKH; ROTATE; TEEGEN, 2000; YIU; LAU; BRUTON, 2007; KHANNA; PALEPU, 2013). The increasing importance of EEF in the world economy sparked the research in this paper, which sought to expand the knowledge on this subject by explaining the logic behind the recent success of EEF in export markets.

EEF are believed to be less competitive in global markets than DEF (GAUR; KUMAR; SINGH, 2014; SINGH, 2009; TITUS; SAMUEL; AJAO, 2013). Technological

innovation is an extremely important factor for a firm’s international competitiveness, though there are also barriers, risks and costs associated with export activity. I proposed that, despite sufficient technological innovation, a firm will continue to focus on domestic operations if its management is overly concerned with the negative aspects of exporting. In such a context, this study contributes to internationalization theory by highlighting the strategic role of a firm’s willingness to export.

I proposed my model based on these arguments and included two fundamental causes to explain the export performance of EEF. While I derived this model with EEF in mind, I can speculate on its application in developed economies. The two causes are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary, since DEF with sufficient internal R&D capability can internationalize without a serious dependency on government support and vice versa.

This study has some limitations. First, my survey response rate was not very high, even though I corrected it through bootstrapping. Second, BRIC countries do not represent all emerging economies, although there is sufficient government intervention variability to test my hypotheses. Third, my model did not address the differences on the effect of coordinated and liberal economies’ institutions on national comparative advantages (WITT; JACKSON, 2016). Fourth, my model did not consider the event of intermittent exporting (BERNINI; DU; LOVE, 2016), which was not addressed in the survey although it is likely to be observed in my sample. Lastly, the study is limited to only manufacturing firms, which prevents me from making any predictions about service-oriented industries, as their export performance indicators and export mechanisms differ significantly. I believe that further analysis could address these limitations.

Despite these limitations, the results of this study should be of interest to entrepreneurs from emerging economies who are willing to expand into international markets. Policymakers may also use these results to develop programs to encourage economic growth through export expansion.

REFERENCE

AABY, N.-E.; SLATER, S. F. Management influences on export performance: a review of the empirical literature 1978-1988. International Marketing Review, v. 6, n. 4, p. 7-26, 1989.

ACS, Z. J.; ANSELIN, L.; VARGA, A. Patents and innovation counts as measures of regional production of new knowledge. Research Policy, v. 31, n. 7, p. 1069-85, 2002.

AFONSO, A.; FURCERI, D. Government size, composition, volatility and economic growth. European Journal of Political Economy, v. 26, n. 4, p. 517-32, 2010.

ALMUS, M.; CZARNITZKI, D. The effects of public R&D subsidies on firms' innovation activities: the case of Eastern Germany. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, v. 21, n. 2, p. 226-36, 2003.

ALMUS, M.; NERLINGER, E. A. Growth of new technology-based firms: which factors matter? Small Business Economics, v. 13, n. 2, p. 141-54, 1999.

ANDERSSON, S.; GABRIELSSON, J.; WICTOR, I. International activities in small firms: examining factors influencing the internationalization and export growth of small firms. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l'Administration, v. 21, n. 1, p. 22-34, 2004.

ARBIX, G.; SALERNO, M. S.; DE NEGRI, J. A. Innovation through internationalization is good for Brazilian exports. Brasília: Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA), 2004. Available in:

<http://sociologia.fflch.usp.br/sites/sociologia.fflch.usp.br/files/Glauco_innovation.pdf>.

ARELLANO, C. Default risk and income fluctuations in emerging economies. The American Economic Review, v. 98, n. 3, p. 690-712, 2008.

ATALAY, M.; ANAFARTA, N.; SARVAN, F. The relationship between innovation and firm performance: An empirical evidence from Turkish automotive supplier industry. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, v. 75, p. 226-35, 2013.

ATUAHENE-GIMA, K. The influence of new product factors on export propensity and

1995.

AULAKH; P. S.; ROTATE; M.; TEEGEN, H. Export strategies and performance of firms from emerging economies: Evidence from Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. Academy of Management Journal, v. 43, n. 3, p. 342-61, 2000.

AXINN, C. N.; MATTHYSSENS, P. Limits of internationalization theories in an unlimited world. International Marketing Review, v. 19, n. 5, p. 436-49, 2002.

AXINN, C. N.; SAVITT, R.; SINKULA, J. M.; THACH, S. V. Export intention, beliefs, and behaviors in smaller industrial firms. Journal of Business Research, v. 32, n. 1, p. 49-55, 1995.

BADINGER, H.; URL, T. Export Credit Guarantees and Export Performance: Evidence from Austrian Firm‐level Data. The World Economy, v. 36, n. 9, p. 1115-30, 2013.

BAGOZZI, R. P.; YI, Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, v. 40, n. 1, p. 8-34, 2012.

BASBERG, B. L. Patents and the measurement of technological change: a survey of the literature. Research Policy, v. 16, n. 2, p. 131-41, 1987.

BECCHETTI, L.; ROSSI, S. P. The positive effect of industrial district on the export

performance of Italian firms. Review of Industrial Organization, v. 16, n. 1, p. 53-68, 2000.

BERCHICCI, L. Towards an open R&D system: Internal R&D investment, external

knowledge acquisition and innovative performance. Research Policy, v. 42, n. 1, p. 117-27, 2013.

BERNINI, M.; DU, J.; LOVE, J. H. Explaining Intermittent Exporting: Exit and Conditional Re-Entry in Export Markets. Journal of International Business Studies, v. 47, n. 9, p. 1058-76, 2016.

BUCKLEY, P. J.; CARTER, M. J. A formal analysis of knowledge combination in

multinational enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies, v. 35, n. 5, p. 371-84, 2004.

CADOT, O.; FERNANDES, A. M.; GOURDON, J.; MATTOO, A. Are the benefits of export support durable? Evidence from Tunisia. Journal of International Economics, v. 97, n. 2, p. 310-24, 2015.

CALDERÓN, C.; FUENTES, R. Characterizing the business cycles of emerging economies, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series: World Bank, 2010.

CALOF, J. L..; BEAMISH, P. W. Adapting to foreign markets: Explaining internationalization. International Business Review, v. 4, n. 2, p. 115-31, 1995.

CASILLAS, J. C.; ACEDO, F. J. Speed in the internationalization process of the firm. International Journal of Management Reviews, v. 15, n. 1, p. 15-29, 2013.

CAVUSGIL, S. T.; KNIGHT, G. The born global firm: An entrepreneurial and capabilities perspective on early and rapid internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies, v. 46, n. 1, p. 3-16, 2015.

CETORELLI, N.; GOLDBERG, L. S. Global banks and international shock transmission: Evidence from the crisis. IMF Economic Review, v. 59, n. 1, p. 41-76, 2011.

CHARI, M. D.; DAVID, P. Sustaining superior performance in an emerging economy: An empirical test in the Indian context. Strategic Management Journal, v. 33, n. 2, p. 217-29, 2012.

CHEN, J.; SOUSA, C. M.; HE, X. The determinants of export performance: a review of the literature 2006-2014. International Marketing Review, v. 33, n. 5, p. 626-70, 2016.

CHENG, E. W. SEM being more effective than multiple regression in parsimonious model testing for management development research. Journal of Management Development, v. 20, n. 7, p. 650-67, 2001.

CHEPTEA, A.; FONTAGNÉ, L.; ZIGNAGO, S. European export performance. Review of World Economics, v. 150, n. 1, p. 25-58, 2014.

CHILD, J.; RODRIGUES, S. B. The internationalization of Chinese firms: A case for

theoretical extension?. Management and Organization Review, v. 1, n. 3, p. 381-410, 2005. COOMBS, J. E.; SADRIEH, F.; ANNAVARJULA, M. Two decades of international

entrepreneurship research: what have we learned-where do we go from here? International Journal of Entrepreneurship, v. 13, p. 23, 2009.

COOPER, R. G.; KLEINSCHMIDT, E. J. The impact of export strategy on export sales performance. Journal of International Business Studies, v. 16, n. 1, p. 37-55, 1985.

CUERVO-CAZURRA, A.; ANDERSSON, U.; BRANNEN, M. Y.; NIELSEN, B. B.;

REUBER, A. R. From the Editors: Can I trust your findings? Ruling out alternative

explanations in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, v. 47, n. 8, p. 881-97, 2016.

CZINKOTA, M. R.; JOHNSTON, W. J. Segmenting US firms for export development. Journal of Business Research, v. 9, n. 4, p. 353-65, 1981.

DHANARAJ, C.; BEAMISH, P. W. A resource‐based approach to the study of export performance. Journal of small business management, v. 41, n. 3, p. 242-61, 2003.

DOMINGUEZ, L. V.; SEQUEIRA, C. G. Determinants of LDC exporters' performance: A cross-national study. Journal of International Business Studies, v. 24, n. 1, p. 19-40, 1993.

DOSOGLU-GUNER, B. An exploratory study of the export intention of firms: The relevance of organizational culture. Journal of Global Marketing, v. 12, n. 4, p. 45-63, 1999.

DUNNING, J. H. Explaining changing patterns of international production: in defence of the eclectic theory. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, v. 41, n. 4, p. 269-95, 1979.

FELDMAN, M. P.; KELLEY, M. R. The ex ante assessment of knowledge spillovers:

Government R&D policy, economic incentives and private firm behavior. Research Policy, v. 35, n. 10, p. 1509-21, 2006.

FILATOTCHEV, I.; STRANGE, R.; PIESSE, J.; LIEN, Y.-C. FDI by firms from newly

industrialised economies in emerging markets: corporate governance, entry mode and location. Journal of International Business Studies, v. 38, n. 4, p. 556-72, 2007.

FLYER, F.; SHAVER, J. M. Location choices under agglomeration externalities and strategic interaction. Advances in Strategic Management, v. 20, p. 193-214, 2003.

performance and competitiveness. International Business Review, v. 21, n. 6, p. 1065-86, 2012.

GÖRG, H.; HENRY, M.; STROBL, E. Grant support and exporting activity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, v. 90, n. 1, p. 168-74, 2008.

GANOTAKIS, P.; LOVE, J. H. Export propensity, export intensity and firm performance: The role of the entrepreneurial founding team. Journal of International Business Studies, v. 43, n. 8, p. 693-718, 2012.

GARCÍA‐QUEVEDO, J. Do public subsidies complement business R&D? A meta‐analysis of the econometric evidence. Kyklos, v. 57, n. 1, p. 87-102, 2004.

GAUR, A. S.; KUMAR, V.; SINGH, D. Institutions, resources, and internationalization of emerging economy firms. Journal of World Business, v. 49, n. 1, p. 12-20, 2014.

GIRMA, S.; GÖRG, H.; WAGNER, J. Subsidies and exports in Germany. first evidence from enterprise panel data. Applied Economics Quarterly, v. 55, n. 3, p. 179-95, 2009.

GIRMA, S.; GONG, Y.; GORG, H.; YU, Z. Can production subsidies foster export activity? Evidence from Chinese firm level data. Evidence from Chinese Firm Level Data, 2006.

GOOLSBEE, A. Does government R&D policy mainly benefit scientists and engineers? American Economic Review, v. 88, n. 2, p. 298-302, 1998.

GOURLAY, A.; SEATON, J.; SUPPAKITJARAK, J. The determinants of export behaviour in UK service firms. The Service Industries Journal, v. 25, n. 7, p. 879-89, 2005.

GROSSE, R.; BEHRMAN, J. N. Theory in international business. Transnational Corporations, v. 1, n. 1, p. 93-126, 1992.

GUAN, J.; MA, N. Innovative capability and export performance of Chinese firms. Technovation, v. 23, n. 9, p. 737-47, 2003.

HAGEDOORN, J.; CLOODT, M. Measuring innovative performance: is there an advantage in using multiple indicators? Research Policy, v. 32, n. 8, p. 1365-79, 2003.

HALL, B. H.; LERNER, J. The financing of R&D and innovation. Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, v. 1, p. 609-39, 2010.

HALL, B. H.; LOTTI, F.; MAIRESSE, J. Evidence on the impact of R&D and ICT

investments on innovation and productivity in Italian firms. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, v. 22, n. 3, p. 300-28, 2013.

HALLAK, J. C.; SIVADASAN, J. Firms' exporting behavior under quality constraints: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2009.

HASSEL, A.; HÖPNER, M.; KURDELBUSCH, A.; REHDER, B.; ZUGEHÖR, R. Two dimensions of the internationalization of firms. Journal of Management Studies, v. 40, n. 3, p. 705-23, 2003.

HENDRICKS, K. B.; SINGHAL, V. R. Firm characteristics, total quality management, and financial performance. Journal of Operations Management, v. 19, n. 3, p. 269-85, 2001.

HOSKISSON, R. E.; EDEN, L.; LAU, C. M.; WRIGHT, M. Strategy in emerging economies. Academy of Management Journal, v. 43, n. 3, p. 249-67, 2000.

HUJER, R. & RADIĆ, D. Evaluating the impacts of subsidies on innovation activities in Germany. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, v. 52, n. 4, p. 565-86, 2005.

HUNG, K.-P.; CHOU, C. The impact of open innovation on firm performance: The

moderating effects of internal R&D and environmental turbulence. Technovation, v. 33, n. 10, p. 368-80, 2013.

ITO, K.; PUCIK, V. R&D spending, domestic competition, and export performance of Japanese manufacturing firms. Strategic Management Journal, v. 14, n. 1, p. 61-75, 1993.

IYER, L. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance in Emerging Markets. World Scientific, 2016.

JAFFE, E. D.; PASTERNAK, H. An attitudinal model to determine the export intention of non-exporting, small manufacturers. International Marketing Review, v. 11, n. 3, p. 17-32, 1994.

JOHANSON, J.; MATTSSON, L.-G. Internationalisation in industrial systems—a network approach. Knowledge, Networks and Power, p. 111-32, 2015.

JOHANSON, J.; VAHLNE, J.-E. The internationalization process of the firm—a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of

International Business Studies, v. 8, n. 1, p. 23-32, 1977.

JOHANSON, J. & VAHLNE, J.-E. The mechanism of internationalisation. International Marketing Review, v. 7, n. 4, p. 11-24, 1990.

JOHNSTONE, N.; HAŠČIČ, I.; POPP, D. Renewable energy policies and technological innovation: evidence based on patent counts. Environmental and Resource Economics, v. 45, n. 1, p. 133-55, 2010.

KATSIKEAS, C. S.; LEONIDOU, L. C.; MORGAN, N. A. Firm-level export performance assessment: review, evaluation, and development. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, v. 28, n. 4, p. 493-511, 2000.

KHANNA, T.; PALEPU, K. Winning in emerging markets: A road map for strategy and execution: Harvard Business Press, 2013.

KLEINKNECHT, A.; VAN MONTFORT, K.; BROUWER, E. The non-trivial choice between innovation indicators. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, v. 11, n. 2, p. 109-21, 2002.

KLETTE, T. J.; MØEN, J.; GRILICHES, Z. Do subsidies to commercial R&D reduce market failures? Microeconometric evaluation studies. Research Policy, v. 29, n. 4, p. 471-95, 2000. KOTABE, M.; SRINIVASAN, S. S.; AULAKH, P. S. Multinationality and firm performance: The moderating role of R&D and marketing capabilities. Journal of International Business Studies, v. 33, n. 1, p. 79-97, 2002.

KUMAR, N.; SIDDHARTHAN, N. Technology, firm size and export behaviour in developing countries: the case of Indian enterprises. The Journal of Development Studies, v. 31, n. 2, p. 289-309, 1994.

KUNDU, S. K.; KATZ, J. A. Born-international SMEs: BI-level impacts of resources and intentions. Small Business Economics, v. 20, n. 1, p. 25-47, 2003.

LACH, S. Do R&D subsidies stimulate or displace private R&D? Evidence from Israel. The Journal of Industrial Economics, v. 50, n. 4, p. 369-90, 2002.

LANJOUW, J. O.; SCHANKERMAN, M. Patent quality and research productivity: Measuring innovation with multiple indicators. The Economic Journal, v. 114, n. 495, p. 441-65, 2004.

LEONIDOU, L.; SAMIEE, S.; GELDRES, V. V. Using national export promotion programs to assist smaller firms' international entrepreneurial initiatives. Handbook of Research on International Entrepreneurship Strategy: Improving SME Performance Globally, Elgar Publishing, 2015.

LEONIDOU, L. C. An analysis of the barriers hindering small business export development. Journal of Small Business Management, v. 42, n. 3, p. 279-302, 2004.

LEONIDOU, L. C.; KATSIKEAS, C. S. The export development process: an integrative review of empirical models. Journal of International Business Studies, v. 27, n. 3, p. 517-51, 1996.

LEVY, D. M. Estimating the impact of government R&D. Economics Letters, v. 32, n. 2, p. 169-73, 1990.

LIPUMA, J. A.; NEWBERT, S. L.; DOH, J. P. The effect of institutional quality on firm export performance in emerging economies: a contingency model of firm age and size. Small Business Economics, v. 40, n. 4, p. 817-41, 2013.

LOVE, J. H.; ROPER, S. The determinants of innovation: R & D, technology transfer and networking effects. Review of Industrial Organization, v. 15, n. 1, p. 43-64, 1999.

LUO, L.; YANG, Y.; LUO, Y.; LIU, C. Export, subsidy and innovation: China’s state-owned enterprises versus privately-owned enterprises. Economic and Political Studies, v. 4, n. 2, p. 137-55, 2016.

MADHOK, A.; KEYHANI, M. Acquisitions as entrepreneurship: asymmetries, opportunities, and the internationalization of multinationals from emerging economies. Global Strategy Journal, v. 2, n. 1, p. 26-40, 2012.

MAJOCCHI, A.; BACCHIOCCHI, E.; MAYRHOFER, U. Firm size, business experience and export intensity in SMEs: A longitudinal approach to complex relationships. International Business Review, v. 14, n. 6, p. 719-38, 2005.

MILLER, D. J.; FERN, M. J.; CARDINAL, L. B. The use of knowledge for technological innovation within diversified firms. Academy of Management Journal, v. 50, n. 2, p. 307-25, 2007.

MORGAN, R. E.; KATSIKEAS, C. S. Export stimuli: Export intention compared with export activity. International Business Review, v. 6, n. 5, p. 477-99, 1997.

MUDAMBI, R.; SWIFT, T. Knowing when to leap: Transitioning between exploitative and explorative R&D. Strategic Management Journal, v. 35, n. 1, p. 126-45, 2014.

NELSON, R. R. Why do firms differ, and how does it matter? Strategic Management Journal, v. 12, n. S2, p. 61-74, 1991.

OVIATT, B. M.; MCDOUGALL, P. P. Toward a theory of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, v. 25, n. 1, p. 45-64, 1994.

PAVORD, W. C.; BOGART, R. G. The dynamics of the decision to export. Akron Business and Economic Review, v. 6, n. 1, p. 6-11, 1975.

PENG, M. W.; WANG, D. Y.; JIANG, Y. An institution-based view of international business strategy: A focus on emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, v. 39, n. 5, p. 920-36, 2008.

POPP, D. Lessons from patents: using patents to measure technological change in environmental models. Ecological Economics, v. 54, n. 2, p. 209-26, 2005.

RAMAMURTI, R. What have we learned about emerging market MNEs?. Emerging multinationals in emerging markets. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

RAMAMURTI, R. What is really different about emerging market multinationals? Global Strategy Journal, v. 2, n. 1, p. 41-47, 2012.

ROTTIG, D.; ROTTIG, D. Institutions and emerging markets: Effects and implications for multinational corporations. International Journal of Emerging Markets, v. 11, n. 1, p. 2-17,

2016.

SCHILLING, M. A. Technology success and failure in winner-take-all markets: The impact of learning orientation, timing, and network externalities. Academy of Management Journal, v. 45, n. 2, p. 387-98, 2002.

SINGH, D. A. Export performance of emerging market firms. International Business Review, v. 18, n. 4, p. 321-30, 2009.

SKOUFIAS, E. Economic crises and natural disasters: Coping strategies and policy implications. World Development, v. 31, n. 7, p. 1087-102, 2003.

SMITH, V.; MADSEN, E. S.; DILLING-HANSEN, M. Do R&D investments affect export performance?: Centre for Industrial Economics, Institute of Economics, University of Copenhagen, 2002.

SOUSA, C. M.; MARTÍNEZ‐LÓPEZ, F. J.; COELHO, F. The determinants of export

performance: A review of the research in the literature between 1998 and 2005. International Journal of Management Reviews, v. 10, n. 4, p. 343-74, 2008.

STERLACCHINI, A. Do innovative activities matter to small firms in non-R&D-intensive industries? An application to export performance. Research Policy, v. 28, n. 8, p. 819-32, 1999

TESAR, G.; TARLETON, J. S. Comparison of Wisconsin and Virginia small-and medium-sized exporters: aggressive and passive exporters. Export management: An international context, p. 85-112, 1982.

THITE, M.; WILKINSON, A.; SHAH, D. Internationalization and HRM strategies across subsidiaries in multinational corporations from emerging economies—A conceptual framework. Journal of World Business, v. 47, n. 2, p. 251-58, 2012.

TITUS, O. A.; SAMUEL, O.; AJAO, O. A Comparative Analysis of Export Promotion Strategies In Selected African Countries (South Africa, Nigeria and Egypt). International Journal of Management Sciences, v. 1, n. 6, p. 204-11, 2013.