REVISTA BRASILEIRA DE GESTÃO DE NEGÓCIOS ISSN 1806-4892 REVIEw Of BuSINESS MANAGEMENT

© FECAP

RBGN

Received on July 09, 2015. Approved on December 09, 2015

1.Maider Aldaz PhD in Economy University of the Basque Country

(Spain)

[maider.aldaz@ehu.eus]

2. Igor Alvarez PhD in Economy University of the Basque Country

(Spain)

[igor.alvarez@ehu.eus]

3.José Antonio Calvo PhD in Economy University of the Basque Country

(Spain)

[jacs.calvo@ehu.eus]

Review of Business Management

DOI:10.7819/rbgn.v17i58.2687

Non-financial reports, anti-corruption

performance and corporate reputation

Maider Aldaz Igor Alvarez José Antonio Calvo

Financial Economy I, University of the Basque Country, Spain

Responsible editor: Guilherme de Farias Shiraishi, Dr. Evaluation process: Double Blind Review

ABstRACt

Objective – his paper analyzes whether the anti-corruption reporting practices of the companies are a relection of adequate anti-corruption systems put in place by companies, or whether the disclosure is merely a tool for companies to improve their reputation and thus maintain their legitimacy.

Design/methodology/approach – We apply the PLS method to the collected data in a content analysis of the sustainability reports of 31 companies within the Ibex 35 in December 2008.

heoretical foundation – In the analysis, we use both the legitimacy theory and the stakeholder theory, because we consider them as complementary theories and consistent with our approach.

Findings – he results show that regarding the corruption issue there is a negative relationship between disclosure and performance, that is, companies with poor performance disclose more. On the other hand, the results relect the existence of a positive relationship between disclosure and reputation, i.e. report information to interested parties enhances the perception of stakeholders about the company. his inding could be justiied by the above two theories.However, we can’t conclude that companies with good performance disclose information to key stakeholders in order to strengthen relations, as stated by the stakeholder theory.

Practical implications – this study provides evidence of how companies use non-inancial reporting-speciically anti-corruption data- to improve corporate reputation. It is also noted that reporting practices not necessarily have to be in accordance with the actual anti-corruption practices of irms.

1 IntRODuCtIOn

Companies in order to survive and be competitive (Porter & Kramer, 2006) should increasingly be committed with their stakeholders. This situation, among others, supposes the need of more and better information to their stakeholders regarding the company performance both in the economic sphere and also in the social and environmental spheres. A consequence of this higher need is the exponential increase of sustainability reports published by KPMG companies (2013), that is, the traditional inancial accountancy has to be supplemented with the social and environmental accountability.

In the past fe w years, academic investigations within the sphere of the corporate social responsibility (CSR) have considerably increased. In this ield of study, the instrumental aspect has been the most studied. Lee (2008) observes a clear change in the evolution of CSR literature, although in the beginning (60’s and 70’s) most of the works had an ethical orientation, subsequently there was a substantial change, and most of the works could be grouped under the instrumental orientation, which supposes a relevant change from the macro level to the organizational level (Carroll & Shabana, 2010). One of the possible reasons for that is stated by Schaltegger and Synnestvedt (2002), who understand that the companies will only undertake to carry out processes that allow improving their social and environmental behavior if they see a clear positive relation with their inancial behavior.

From the instrumental point of view, most of the works addresses the existing relation between financial performance and social performance, with a diversity of opposed results (Brammer & Millington, 2008; Hahn & Figge, 2011; Lockett & Visser, 2006; Orlitzky, Schmidt & Rynes, 2003; Ortas, Gallego-Alvarez & Álvarez, 2014; Wu, 2006).

Another major group of academic works address the hypothetical relation betwee the social performance of the company and the social

Non-financial reports, anti-corruption performance and corporate reputation

herefore, our work has the main goal of getting to know the relation between anti-corruption disclosure and performance, also studying the role played by reputation in this relation.

On one side, we will analyze what is the existing relation between what the companies say they do in the field of anti-corruption management, and what they actually do. We consider this a signiicant contribution to the literature that has mainly studied this relation in the environmental ield, and not so much in the social ield.

On the other side, we also intend to contribute with our analysis and results to the few works in literature that study the existing relation between disclosure and reputation (Brown, Guidry & Patten, 2010; Cho, Guidry, Hageman & Patten, 2012; Toms, 2002). We will analyze the existing relation between what the companies disclose and what the users of such disclosures perceive.

he work is structured as follows: After the analysis of the background of the area in the second section, we propose our hypothesis to compare. In a third section, we present the investigation method used, to proceed to the fourth section where we analyze the obtained results. To inalize, in the last section we will present the conclusions and suggest future lines of investigation.

2 BACKgROunD AnD DevelOPMent OF the hyPOthesIs

here are no single theory that allows explaining the causes and consequences of the social disclosure performed by organizations (Gray, Kouhy & Lavers, 1995a, 1995b). Nonetheless, it can be said that the social theories were mostly imposed to the investigation in social and environmental accountability (Burrell & Morgan, 1979; Cho, 2009; Trotman & Bradley, 1981).

Social theories are those having a system perspective of the organization and of the society

(Gray, Owen & Adams, 1996), which implies that the organization is inluenced, and in its turn it also inluences the society in which it performs its activity (Deegan, 2002; Hines, 1989). Among such theories, the literature presents as predominant the theory of the political economy, of the legitimacy, and of the stakeholders. he last two – proposed subsequently to the irst one mentioned – take as base for their theorization the postulates of the political economy theory (Elijido-Ten, Kloot, & Clarkson, 2010). he perspective underlying all of them is that the society, the politics, and the economy cannot be analyzed independently, and thus the political, social, and institutional structure where the economic activity is performed should be considered to analyze economic aspects (Deegan, 2002; Miller, 1994). hey also recognize the efects of the accounting reports on the distribution of income, power, and wealth (Cooper & Sherer, 1984; Tinker, 1984).

Of all of them, the theory of legitimacy (Lindblom, 1994) – above all in its strategic aspect (Deegan, 2007) – has been the most used to analyze the interaction between an organization and its physical and social environment (Owen, 2008), as well as to analyze the social disclosures of the companies (Garriga & Melé, 2004; Gray, Kouhy & Lavers, 1995a, 1995b; Lukka, 2010). In many occasions, it has been seen as a variant of the stakeholders theory, which adds conlict and disagreement to the analysis of reality; and, therefore, it is regarded as appropriate to explain more specific information about the social practice of companies (Gay et al., as mentioned in O’Donovan 2002). To this efect, it focuses on the existing rules of the society (Gray, Dey, Owen, Evans, & Zadek, 1997), and therefore seems to be more appropriate to analyze the complex relation between company and society.

2012Cho & Patten, 2007; Deegan, 2002; Husillos, 2007; Patten, 1991, 1992; Tilling & Tilt, 2010). In turn, it points out that the disclosure of social and environmental aspects does not have to suppose a responsible activity on the part of companies concerning such aspects (Ashforth & Gibbs, 1990; Deegan, 2002; Dowling & Prefer, 1975; Patten, 1991; Schuman, 1995). To the contrary, it is stated that the disclosure can help to reinforce the legitimacy of companies with worse performance (Bebbington, Larrinaga & Moneva, 2008), or that the disclosure is used by companies to counteract the negative efect of the poor performance on the corporate reputation (Cho et al., 2012).

In turn, based on the theory of stakeholders, we could say that companies that properly manage their relations with the stakeholders will have the necessary support for their continuity (Clarkson, 1995), and that those having a good management of social and environmental aspects will be those having a better performance in the ield, and possibly a better reputation. Good management is understood as the integration of the already mentioned aspects in the mission of the company, as well as the measurement and disclosure of the results obtained regarding such aspects (Moneva, Rivera-Lirio, & Muñoz-Torres, 2007).

When we observe recent studies that analyze the relation between disclosure and performance – focused on the environmental area – (Cho et al., 2012; Cho & Patten, 2007; Hughes et al., 2001; Patten, 2002), they show evidences that such relation is negative. We have not found works that based on social aspects analyze such relation, which would be the case of the anti-corruption practices. However, we observe that social and environmental aspects are encompassed within the same area in the literature, and that the rhetoric of companies about their social responsibility, either in the environmental or in the social sphere – regarding aspects such corruption ight – is being used to legitimate and consolidate their power (Banerjee, 2008; Nyberg & Wright, 2013).

In any case, we observe that the disclosure will be the consequence of the performance,

and based on previous evidences that point out the existence of a negative relation between environmental disclosure and performance, and considering that the corporate behavior in terms of anti-corruption should follow an agenda similar to that used in the environmental area, we propose our irst hypothesis:

h1: here is a negative relation between the level of disclosure of anti-corruption practices and the anti-corruption performance.

he main goal of companies is to generate value, trust and legitimacy (Aldaz, Calvo & Álvarez, 2012), and because of that they will try to coordinate the interests of all their stakeholders (Evan & Freeman, 1993), and thus avoid possible risks that prevent them from attaining such objectives. Companies can invest in social responsibility projects and processes to reduce possible risks to which they are exposed (Toms, 2002), and use disclosure as a relex of their actual activities.

Non-financial reports, anti-corruption performance and corporate reputation

is that the image ofered by the company to its stakeholders is adjusted to the provisions of its article of association in all moments, and thus preventing damages to the corporate reputation which could result in the loss of the corporate value.

Part of the literature confirms that organizations provide social and environmental information to keep the legitimacy in the society where they operate (Deegan & Blomquist, 2006; Islam & Deegan, 2010; O›Donovan, 2002), or as part of the process performed to manage the supported reputation risk (Bebbington et al., 2008); that the communication established with the stakeholder groups is a key-part to attain the objective of reaching the status of “reputable” (Villafañe, 2004); and that the disclosure of social and environmental information can improve the corporate reputation (Brown et al., 2010; Toms, 2002). One of the tools used by companies to perform such communication and to create the desired images in the minds of their stakeholders are the disclosures done in the sustainability reports they voluntarily publish. In such reports, they comprise all range of values, topics, and processes that companies should face to minimize any damage that can result from their activities, and to deinitely create economic, social, and environmental value (Chin, Tsao & Chi, 2007). his practice has been analyzed in the literature, particularly the work of Blanck, Castelo-Branco, Cho, and Sopt (2013) shows how the company Siemens – which has suffered a huge loss of reputation due to the corruption scandal in which it was involved – managed to improve its reputation through the communication with its stakeholders until becoming a leader company in regard to its anti-corruption practices (Sidhu, 2009).

All of that lead us to propose our second hypothesis:

h2: here is a positive relation between the disclosure of information regarding anti-corruption practices and the social responsibility reputation of companies.

The corporate reputation is the sum of several stakeholders perceptions about the entity. It is a multidimensional construct, which allows the same company having several reputations: one reputation for quality, another for product innovation, another for environmental management, etc., and all these dimensions together create a global reputation of the organization.

Since the conceptual deinition provided by Fombrun (1996), it is pointed out that at least in a normative sense the corporate reputation should be based on an underlying performance. That is, when a company has a good social responsibility reputation, it should necessarily have a good performance concerning the activities the company performs in the social responsibility sphere. here are evidences that this relation is at least attained between the inancial performance and the corporate reputation (Brammer & Pavelin, 2006; Brown & Perry, 1994; Brown et al., 2010).

There are several works that globally analyze the construct of reputation: conceptually deining it (Fombrun, 1996; Fombrun & Riel, 1997), observing how it is created (Cramer & Ruei, 1994; Fombrun & Shanley, 1990; Rao, 1994), and proposing the way to measure it, (Helm, 2005; Ponzi, Fombrun & Gardberg, 2011). Others focus on a single dimension of the construct: environmental reputation (Cho et al., 2012; Toms 2002), good quality reputation (Dana & Fong, 2011); product reputation (Rao, 1994).

In turn, we have found works that analyze the power of reputation to create value (Fombrun, 1996; Sven & Hildebrendt, 2014), relating it to the corporate strategy (Weigelt & Camerer, 1988), or to the management of business risks (Bebbington et al., 2008; Eccles et al., 2007; Fombrun et al., 2000; Fombrun, Nielsen & Trad 2007; Unerman 2008), and uniting it to the social disclosure practices of companies (Brown-Liburd, Cohen & Zamora, 2012; Nikolaeva & Bicho, 2011).

responsibility, analyzing the efect of the social responsibility practices on the reputation.

he works that study the relation between CSR activities and the global reputation (Brammer & Pavelin, 2006; Choi & Wang, 2009; Dowling, 2004; King & Mcdonnell, 2012) conclude that a proper social performance positively inluences a good corporate reputation. However, the work of Cho et al. (2012) focused on the analysis of a concrete area of the global construct: the environmental reputation, and that analyzes 92 American companies belonging to the most “sensitive” industries from the environmental viewpoint, provides evidences that the relation between environmental performance and environmental reputation is negative.

We have not found many works speciically focusing on the concept of social responsibility reputation or social performance reputation (Ziglydopoulos, 2001, 2003). One of these works (Zyglidopoulos, 2001) studies the efect that a stand-alone fact or “accident” can have on the social responsibility reputation. It deines accidents as undesirable or unfortunate events that independently and unexpectedly occur in the life

of a company, and cause damages to any number or type of their private stakeholders, damaging the reputation of the company. A clear example of the efect an “accident”/incident of corruption can have on the social responsibility reputation is given by the Siemens case. This company sufered a drop in the reputation indexes when the public was informed that it has paid bribes abroad violating the FCPA anti-corruption law of the United States (Blanck, Castelo-Branco, Cho &Sopt,2013).

From the perspective of the strategic management, those companies managing their economic resources to have the profile of a company committed to the interests of the society will obtain a series of competitive advantages. For instance, companies more transparent regarding their environmental performance will have a better communication with their stakeholders, and can make their stakeholders see a way of acting responsibly in the environmental area, and thus improving their image by creating the so-called “green goodwill” (Ortas et al., 2014), which ultimately indicates a good reputation about its environmental management.

“

”

clear example of the effect an “

”

called “

”

H1

H3 H2

DISCLOSURE

REPUTATION

PERFORMANCE

Non-financial reports, anti-corruption performance and corporate reputation

herefore, we expect that a negative anti-corruption performance supposes a low social responsibility reputation, and in turn a better anti-corruption performance provides a better social responsibility reputation, which lead us to propose the third of our hypothesis:

h3: here is a positive relation between the anti-corruption performance of companies and their social responsibility reputation

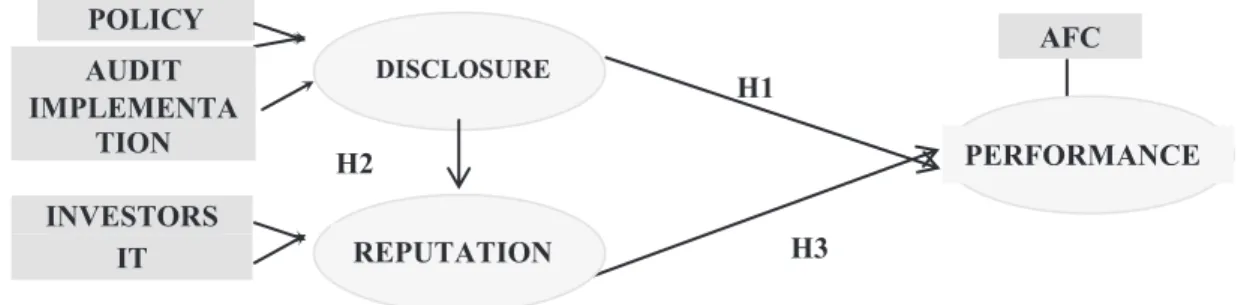

Taking into consideration the analysis in the previous lines, and observing that the existing relation between the three studied variables is complex, we propose the theoretical model presented in Figure 1.

3 MethOD OF InvestIgAtIOn

3.1 he sample

When we selected the sample, we irst had in mind our interest in analyzing companies with a sociocultural context the most similar as possible, since previous works have indicated that the relation between performance and management of social and environmental aspects (Ortas, Álvarez & Garayar, 2015), and the corporate transparency (Prado-Lorenzo, García-Sánchez y Blázquez-Zaballos, 2013) are inluenced by institutional, social and cultural diferences of the business environments. herefore we have decided to analyze companies of a single country, in our case we have analyzed Spanish companies. Secondly, and considering that the disclosure of anti-corruption aspects was a key-variable of the analysis, it was indispensable to have a group of companies that had a certain tradition of informing the social and environmental aspects. he exposure to the public scrutiny of companies listed in the stock exchange market make them feel obliged to provide non-inancial information, in addition to the traditional inancial information. In turn, these are companies which information

is more accessible compared to those that are not listed.

On the other hand, since we want to identify information regarding anti-corruption practices implemented in the companies, it seems interesting to us to analyze the period immediately after the period of economic prosperity experienced in the country and the beginning of the current crisis scenario. We believe this was a time when bad practices were abundant, and thus companies started to consider the anti-corruption area an aspect to be managed.

Because of all that, we have decided to select companies belonging to the Ibex 35 on December 31, 2008. Due to the lack of data on companies composing the sample, and in beneit of a higher comparability of data, we have decided to focus on 31 companies composing the IBEX 35.

3.2 Path analysis

T h i s t e c h n i q u e P L S - S E M (PartialLeastSquared- StructuralEquationModel) is used to analyze causal relations between two or more variables, and is based on a linear equations system, it is a sub-set of structural equations models (SEM). We have decided for this technique because:

b) in our model, the latent variable is measured through formative and non-reflective indicators. The PLS-SEM provides a higher lexibility when formative indicators are involved (Hair, Sarstedt, Ringle & Mena, 2012);

c) of the three types of models that can be proposed – focused, unfocused or balanced, the PLS-SEM would be appropriate for the case of focused or balanced models (Hair et al., 2012). We can say that ours is the last case, for having a balanced number of endogenous and exogenous latent variables;

d) on the other hand, the application of the PLS-SEM is more consistent with our study goal, since this is an exploratory investigation that allows us to develop the theory. And we are not in the way of proving a complex and well established theory, since in this case we should use the traditional method of structural equations. We do not intend to create a complete theoretical model that lead us to observe all the components of the anti-corruption performance concept, but rather to study to which extent this performance is inluenced by the disclosure of companies in this ield, or by the social responsibility reputation of such companies.

3.3 Application to our study

Using the computer application called Smartpls we propose our theoretical model. Through a path analysis, we compared the proposed hypotheses relating the three endogenous variables considered in our study: the disclosure of information about corruption (Disclosure), the anti-corruption performance of companies (Performance), and the social responsibility reputation of the companies (Reputation).

We show through which indicators we will measure the three latent variables of our model as follows.

3.3.1 Measurement of the disclosure

hrough the analysis of the contents of the Ibex 35 companies sustainability reports on December 31, 2008, we observed what the information they publish regarding the anti-corruption practices they have in place is. his analysis leads us to identify 25 items that are related to the topic of corruption.

Subsequently, with the aim of identifying general aspects comprised by the information disclosed by the companies, we performed an Analysis of Multiple Correspondences. By means of this method, we managed to summarize all the information in three general aspects.

We intend to classify the selected companies as for their disclosure level, and thus we take as reference the contributions each of the companies provides to the construction of each of the general aspects. he information on such contributions is the indicator that indicates whether the company informs more or less than the average in each of the three axles.

herefore, in the case of the disclosure we have three indicators or three measurements that contribute to the creation of the latent variable, one indicator per each of the axles: (i) Policy or program against corruption; (ii) Audit and control of corruption; and (iii) Implementation of the anti-corruption policy.

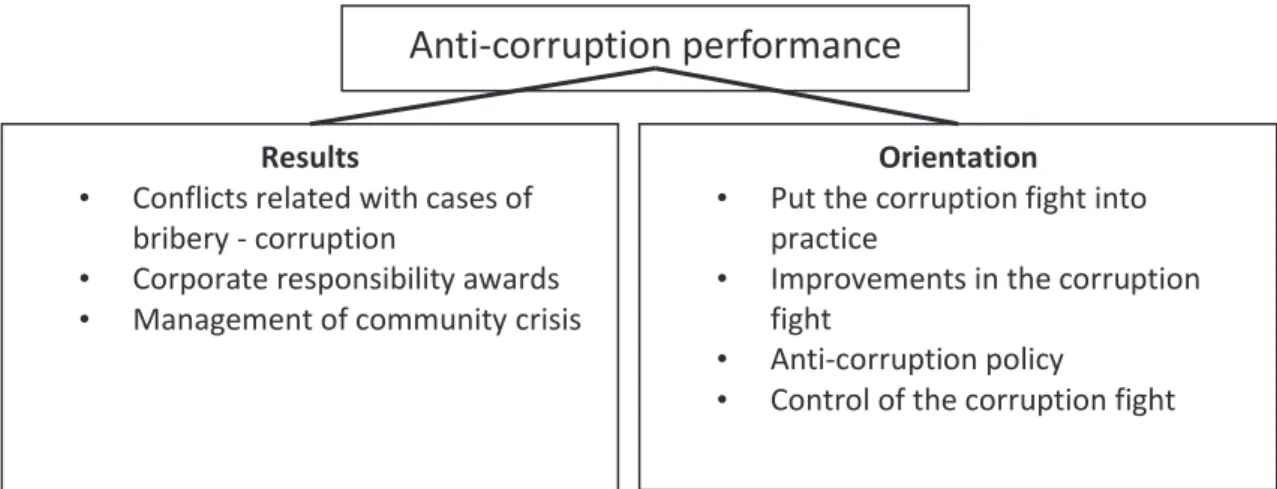

3.3.2 Performance measurement

Using the information provided by the

homson Reuters Datastream (ASSET 4) database, we have built our own indicator. It is a database that provides several classiications regarding the environmental, social, and corporate governance sphere among companies. he anti-corruption practices are situated within the social sphere of the business activity, and thus we use information of the social pillar of the database, which we understood is related to the way companies manage anti-corruption.

Non-financial reports, anti-corruption performance and corporate reputation

On one side, the “result” dimension measures the actual accomplishments of companies in the corruption ield, that is, the efectiveness of the anti-corruption practices in place. On the other side, the “orientation” dimension provides a prospective measurement of the future success of the company. It is noteworthy that in order to measure the current accomplishments of the

companies in terms of anti-corruption a single indicator that has a negative efect in the anti-corruption performance is used (conlicts related to bribery-corruption cases), while the other indicators have a clear positive efect.

Figure 2 shows the indicators that are comprised by the two dimensions through which we built the anti-corruption performance.

“

t”

“

”

we built the anti-corruption performance.

Figure 2.

Composition of the Anti-Corruption Performance variable

Orientation

• Put the corruption fight into practice

• Improvements in the corruption fight

• Anti-corruption policy

• Control of the corruption fight Results

• Conflicts related with cases of bribery - corruption

• Corporate responsibility awards • Management of community crisis

Anti-corruption performance

FIguRe 2 – Composition of the Anti-Corruption Performance variable

Actually, the irst of the indicators that compose the result dimension, the conflicts related to bribery-corruption cases, is measured by the total number of controversies published in the communication media in relation to the corporate ethics, speciically in relation to political contributions or contributions to bribery and corruption.

We also take into consideration as the second indicator if the company has received any corporate responsibility award, for its activities, and for its social, ethical, community, or environmental performance.

At last, we analyze if the company has in place a system of community crisis management, or plans of recuperation or minimization of the efects of reputational disasters.

Regarding the indicators that compose the orientation dimension, the put into practice of the corruption ight, it is measured observing whether:

a) there has been a public commitment of the administrators or members of the board regarding aspects related to bribery and corruption;

b) the company describes in its code of conduct that it makes eforts to comply with the elements regarding bribes and corruption;

c) the company has educated its employees in corruption and bribery prevention; d) it has proper internal communication

tools (whistle blowing system, suggestions box, telephone line, bulletin, webpage, etc.) to improve the elements regarding bribes and corruption;

e) it has and comply with regulations regarding the protection of whistle blowers;

To evaluate the capacity of the corruption ight improvement, we observe if the company sets goals it intends to attain in regard to bribery and corruption aspects.

As for the valuation of the anti-corruption policy, we analyze if the company has in place a reputation policy in face of the community that considers the diverse elements that inluence its global reputation and its license to operate, among which the anti-corruption management is included.

At last, the control of the corruption ight is evaluated by studying if the company controls or watches over its reputation or its relations with the community.

We will obtain the value of the “Anti-corruption performance” of each company through the weighted sum of the scores of the “result” and “orientation” dimensions.

As the information about corruption disclosure is based on the analysis of the 2008 sustainability reports, we consider as being the most proper to take the same year as reference to measure the anti-corruption performance.

hus, in the case of the latent variable “performance”, we observe that it only has one indicator. I.e., this is a construct measured through a single indicator. Some investigators argue that if the sphere of a construct is one-dimensional, the better approach is through a single measurement element, and this argument has been empirically supported in the works of Bergkvist and Rossiter (2007).

In our case, we can say that we are before a one-dimensional construct, since we have previously accomplished the task of building an indicator to measure the anti-corruption performance of companies. When a construct is one-dimensional, as in our case, it is no longer a latent variable, becoming a variable of measurement.

3.3.3 Reputation measurement

We have used two indicators. On one side, the investments that the Norway Government

Pension Fund (in Norwegian, Statenspensjonsfond – Utland, SPU) makes in the companies of the study (we have used this indicator to measure the reputation of companies before investors, who take into consideration aspects such as corruption ight, instead of only considering the inancial data).

On the other hand, we have used a dichotomic indicator (binary variable) that takes the value 1 if a non-investor stakeholder (IT president – Spain) includes the company in the group that positively stands out in aspects of transparency, CSR in general, and corruption-ight in particular, and 0 on the other way round. In this case, the latent variable reputation has two measurement or indicators.

Ultimately, in our theoretical model we have included three endogenous variables or constructs (two latent and one of measurement) that, because of their nature, cannot be empirically observed, and other observable variables (indicators or measurements) that can be deined through a measurement, and are used to capture the contents of the constructs.

In every theoretical model we should consider the existing link between the constructs and their indicators. Two types of links are usually distinguished; on one side, the one pointing out that the indicators are the relex of the non-observed theoretical construct to which they are linked, in such a way that the construct is replaced by what is observed. On the other side, the link that determines that indicators cause or replace the construct. In the irst case, we would be talking about relexive indictors (efects), and in the second, about formative indicators (causes).

Non-financial reports, anti-corruption performance and corporate reputation

a) he direction of the causality between the construct and its indicators. If changes in the indicators suppose changes in the constructs, the indicators would be formative, and if otherwise the changes in the construct are those determining changes in the indicators, we would be talking about relexive indicators. In our case, the changes in the indicators are those to cause the construct value to vary; b) If the indicators are conceptually

interchangeable. If they are not, they are formative indicators, and reflexive indicators in the contrary case. In the analysis we propose the indicators used are non-interchangeable;

c) The covariance of the indicators. The formative indicators do not require a great variance among each other, however the

relexive indicators do. Our indicators do not have a great covariance among each other, since analyzing the correlation coeicient of the indicators belonging to each of our constructs we observe that none of them exceeds the value of 0.6; d) he similarity of the nomological networks

of the indicators. he relexive indicators should have the same background and consequences, in the case of the formative indicators, this is not an indispensable requirement. he indicators we use also do not comply with the requirement of having the same background and consequences;

e) Considering these four criteria, we have decided to build our model using formative indicators. he inal model is the one shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Theoretical model of the Disclosure

–

Reputation

–

Performance relation.

H3

AFC

H1

H2

INVESTORS IT

DISCLOSURE

REPUTATION

PERFORMANCE POLICY

AUDIT IMPLEMENTA

TION

FIguRe 3 – heoretical model of the Disclosure – Reputation – Performance relation.

4 Results

Of the ive indicators used, only two have signiicant relations with the construct they form: the reputation measurement using the perspective of the inverters, and the disclosure measurement through the implementation factor.

he remaining indicators seem not to have signiicance in the formation of our latent variables. hey seem to indicate that, in regard to the improvement of the exterior model quality, it

would be probably interesting to supplement our model with other indicators.

Since our objective is to analyze the existing relation among the three latent variables selected through the data we have, we regard the model as good since it has at least one signiicant indicator in each latent variable.

tABle 1 – Signiicance of the indicators regarding the constructs

Indicator/construct relation t-student levels of probability*

Control -> disclosure 0.541 Not signiicant

Implementation -> disclosure 1.605 P<.1

Anti-corruption policy -> disclosure 0.901 Not signiicant Investors -> reputation 1.659 P<.05

IT -> reputation 0.756 Not signiicant

Note. * Levels of probability for a unilateral (or one-tail) test

We now value the path coeicients, the coeicients of the structural model trajectory. he igure shows the value of coeicients, as well as the percentage of the variance of the endogenous variables explained through our model.

he path coeicients determine both the sign of the relation between variables, as well as to

which extent the changes in the variable of origin suppose changes in the variable of destination. It also indicates to which extent the predictive variables contribute to the variance explained in the dependent variables, thus evaluating the level of signiicance of the relations between constructs.

0.896

AFC -0.101

0.781

INVESTORS

TI

DISCLOSURE

REPUTATION

PERFORMANCE POLICY

AUDIT IMPLEMEN

TATION

FIguRe 4 – Path coeicients.

Analyzing the values of the path coeicients in our study, we observe that there is a positive relation between disclosure and reputation, and that such relation seems to be very solid.

A score exceeding one point in the corruption disclosure by a company implies a better score in 0.781 points regarding the social responsibility reputation of such company.

We observe that our result is consistent with those obtained in previous studies that have analyzed the relation between social and environmental disclosure and the reputation of companies (Brown et al. 2010; Cho et al. 2012; Toms, 2002). herefore, we can say that the existing relation between the two mentioned

variables is positive. his would support the two theories we use in our study, when companies disclose social and environmental information they have a positive efect in their reputation, regardless if they do that to counteract a bad performance or to publicize an appropriate performance.

1333 Rev. bus. manag., São Paulo, Vol. 17, No. 58, pp. 1321-1340, Oct./Dec. 2015

Non-financial reports, anti-corruption performance and corporate reputation

(2007), Hughes et al. (2001), and Patten (2002), which analyze the similar relations between environmental information disclosure and the environmental performance of companies. his lead as to state that the legitimacy theory better explains the relation between both variables, than the stakeholders theory. hus, although we cannot rule out that there are companies that use the corruption disclosure to inform to their stakeholders a good performance in the area, there are more companies using sustainability reports to counteract the consequences of a bad performance.

At last, as for the relation between reputation and performance, it seems to exist an average positive relation. he t-student analysis showed in Figure 5 ratiies that the relation is

signiicant, with probability levels of p< .01. he path coeicient is positive, and as relected in Figure 4 there seems to exist a solid relation, besides being also positive. his path coeicient indicates that the companies which reputation is higher in one point, will also have a better performance in 0.417 points. This result is not coincident with the indings of Cho et al. (2012), which indicate a signiicant and negative relation between reputation and environmental performance. In our case the relation seems to be positive.

To perform the significance analysis, we should set the t-student values of the path coeicients, as well as the percentage of variance of the endogenous variables explained through our model. Figure 5 shows these data.

Figure 5.

T-student values and percentages of the explained variance.

When applying the “

” –

–

t=0.417

AFC

t=0.234

t= 2,950

INVESTORS

TI

DISCLOSURE

DESEMPEÑO POLICY

AUDIT

IMPLEMENTATION

R2=61%

R2=11.8%

REPUTATION

FIguRe 5 – T-student values and percentages of the explained variance.

Starting with the variance analysis, we observe that our model has the capacity to explain 61% of the reputation variance, and 11.8% of the performance variance.

herefore we observe that, for the two endogenous variables, our model achieves the minimum acceptable value of the explained variance; however, while the performance variable stays in values close to the minimum, the reputation variable reaches a value between moderate to substantial.

When applying the “bootstrap” – procedure used in the Path Analysis to provide an estimation of the shape, extension, and bias of the sample distribution of a given statistics – the initial sample is taken, and a great predetermined

number of new samples is randomly created, making a replacement in the original sample for that. It is said that this predetermined number of repetitions or new random samples should be the highest as possible to ensure the stability (Hair, Ringle & Sarstedt, 2011).

In our case, we have done a repetition using 1,000 new random samples (Hesterberg, Monaghan, Moore, Clipson & Epstein, 2005). We have not reached a higher igure because the computer application does not allow us, since it points out the need of using a higher number of indicators to solve the problem.

improve our model, 2) because when introducing more variables we would need a higher number of observations, and actually we don’t have the possibility to access more observations.

It is noteworthy that, to ensure that our results were correct, we have repeated many times the bootstraping re-sampling with diferent number of repetitions, attaining a maximum of 1,000 repetitions, and in all of them the significance or non-significance of the path coeicient are coincident.

Figure 5 shows the values of the path coefficients t-students after doing the “bootstrapping re-sampling” with 1,000 repetitions. It is clear that the only signiicant relation among the three variables is that appearing between disclosure and reputation, which the student-t attains a value of 2.95 (it is signiicant with a probability level of p<.01 for a bilateral or two-tail test), however the other relations proposed, using our study data, are far from being signiicant.

5 COnClusIOns

he results obtained and analyzed in the previous section do not allow us to irmly state that we know the sign of the relation existing between disclosure and performance. However, this work provides evidence about the capacity companies have to afect the corporate reputation by using non-inancial reports, with no need that the contents of such reports are in accordance with the actual practices of the companies.

he results relect that in the topic of corruption there is a negative relation between disclosure and performance, that is, that the companies with worse performance disclose more information. On the other hand, they reflect the existence of a positive relation between divulgation and reputation, i.e. ofering information to the stakeholders improves their perception about the company, aspect that could be justiied by the theories previously mentioned. However, they do not allow us to conclude that

those companies with a good performance disclose information to their main stakeholders with the aim of strengthening relations, as stated by the stakeholders theory.

6 l I M I tAt I O n s A n D l I n e s O F InvestIgAtIOn OPeneD

he main limitation of our work is the size of the sample used in the study, which might have afected the levels of signiicance obtained, and this is one of the main reasons leading us to suggest in future works the application of the theoretical model to a broader sample. We also consider opportune to deeply study particular cases that allow us to know in depth the dynamics created around such relations between disclosure, reputation, and performance, as well as to introduce to the study the quality variable of the information published by companies, not being only limited to the quantity of the disclosed information (Brown et al. 2010; Clarkson, Richardson & Vasvari, 2008). Therefore, we observe the need to deepen the analysis to get to know whether reputation is a relex of the actual performance, or if not, if the companies use such disclosure to mitigate the negative efect of the bad performance on the corporate reputation.

ReFeRenCes

Adams, C. A., Hills, W-Y., & Roberts, C. B. (1998). Corporate social reporting practices in Western Europe: legitimating corporate behaviour? British AccountingReview, 30(1), 1-21.

Aerts, W., & Cormier, D. (2009). Media legitimacy and corporate environmental communications.

Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34(1), 1-27.

Non-financial reports, anti-corruption performance and corporate reputation

Archel, P., Husillos, J., Larrinaga, C., & Spence, C. (2009). Social disclosure, legitimacy theory and the role of the state. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 22(8), 1284-1307.

Ashforth, B. E., & Gibbs, B. W. (1990). he double edge of organizational legitimation.

Organization Science, 1(2), 177-194.

Ashforth, B. E., Gioia, B. A., Robinson S. L., & Trevino L. K. (2008). Re-viewing organizational corruption. Academy of Management Review,

33(3), 670-684.

Banerjee, S. B. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: he good, the bad and the ugly.

Critical sociology, 34(1), 51-79.

Barclay, D., Higgins, C., & homson, R. (1995). he partial least squares (PLD) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technology studies, 2(2), 285-309.

Bebbington, J., Larrinaga, C., & Moneva, J. M. (2008). Corporate social reporting and reputation

risk management. Accounting, Auditing and

Accountability Journal, 21(3), 337-361.

Belkaoui, A., & Karpik, P. G. (1989). Determinants of corporate decision to disclose social information. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 2(1), 36-51.

Bergkvist, L., & Rossiter, J. R. (2007). The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(2) 175-184.

Blanck, R., Castelo-Branco, M., Cho, C, & Sopt, J. (2013). In search of disclosure efects of the Siemens AG’s corruption scandal [Workingpapers

nº15]. OBEGEF-Observatório de Economia e

Gestao de Fraude, Porto, Portugal.

Bollen, K., & Lenox, R. (1991). Conventional wisdom on measurement: A structural equation perspective. Psycological Bulletin, 110(2), 305-314.

Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2008). Does it pay to be different? An analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 29(12), 1325-1343.

Brammer, S. J., & Pavelin S. (2006). Corporate reputation and social performance: The importance of it. Journal of Management Studies, 43(3), 435-455.

Brown, B., & Perry, S. (1994). Removing the inancial performance halo from Fortune’s “most

admired” companies. Academy of Management

Journal, 37(5), 1347-1359.

Brown, N., & Deegan, C. (1999). he public disclosure of environmental performance information: A dual test of media agenda setting theory and legitimacy theory .Accounting and Business Research, 29(1), 21-41.

Brown, D. L., Guidry, R. P., & Patten, D. M. (2010). Sustainability reporting and perceptions of corporate reputation: an analysis using fortune most admired scores. En M. Freedman, & B. Jaggi (Eds.), Sustainability, environmental performance and disclorures (Vol. 4, Series Advances in Environmental Accounting and Management, pp. 83-104). Bingley: Emerald.

Brown-Liburd, H. L., Cohen, J.R., & Zamora, V. L. (2012). The effects of corporate social responsibility investment, assurance, and perceived fairness on investors’ judgments [Working paper Series]. Recuperado de http://papers.ssrn.com/ sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1985839

Burrell, G., & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological paradigms and organisational analysis. Heinemann: Ashgate.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. he Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497- 505.

Carroll, A. B., & Shabana, K. M. (2010). he business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice.

International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(1), 85-105.

Chin, C.-L., Tsao, S.-M., & Chi, H.-Y. (2007). Non-audit services and bias and accuracy of voluntary earnings forecasts reviewed by

incumbent CPAs. Corporate Governance: An

International Review,15(4), 661-676.

Cho, C. H. (2009). Legitimation strategies used in response to environmental disaster: A French case study of Total SA’s Erika and AZF incidents.

European Accounting Review, 18(1), 33-62.

Cho, C. H., Guidry, R. P., Hageman, A. M., & Patten, D. M. (2012). Do actions speak louder than words? An empirical investigation of corporate environmental reputation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 37(1), 14-25.

Cho, C. H., & Patten, D. M. (2007). he role of environmental disclosures as tools of legitimacy: A research note. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(7-8), 639-647.

Choi, J., & Wang, H., (2009). Stakeholder relations and persistence of corporate inancial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 30(8), 895-907.

Clarkson, M. E. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review,

20(1), 92-117.

Clarkson, P. M., Li, Y., Richardson G. D., & Vasvari, F. P. (2008). Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis.

Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4-5), 303-327.

Cooper, D. J., & Sherer, M. J. (1984). he value of corporate accounting reports: Arguments for a political economy of accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 9(3-4), 207-232.

Cramer, S., & Ruefi, T. (1994). Corporate reputation dynamics: Reputation inertia, reputation risk, and reputation prospect.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Management Meetings, Dallas.

Dana, J-D., & Fong, Y-F. (2011). Product quality, reputation, and market structure. International Economic Review, 52(4), 1059-1076.

Deegan, C. (2002). The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures: A theoretical foundation. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 15(3), 282-311.

Deegan, C. (2007). Organizational legitimacy as a motive for sustainability. En J. Unerman, B. O’Dwyer, & J. Bebbington (Eds.), Sustainability Accounting and Accountability (pp. 127-149). London: Routledge.

Deegan, C., & Blomquist, C. (2006). Stakeholder inluence on corporate reporting: An explanation of the interaction between WWF-Australia and the Australian minerals industry. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(4-5), 343-372.

Dowling, G. (2004). Corporate reputations:

Should you compete on yours? California

Management Review, 43(3), 19-36.

Dowling, J., & Pfefer, J. (1975). Organizational legitimacy: Social values and organizational behaviour. Pacific Sociological Review, 18(1), 122-136.

Eccles, R., Newquist, S., & Schatz, R. (2007). Reputation and Its Risks. Harvard Business Review, 87(2), 104-114.

Non-financial reports, anti-corruption performance and corporate reputation

Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 23(8), 1032-1059.

Evan, W. M., & Freeman, R. E. (1993). A stakeholder theory of modern corporation: Katian capitalism. En T. Donaldson, & P. H. Werhane (Eds.), Ethical issues in business. Englewood Clifs

(pp. 166-171). New Jersey: Prenticice-Hall.

Freedman, M., & Wasley, C. (1990). The association between environmental performance and environmental disclosure in annual reports and 10Ks. En M. Neimark (Ed.), Advances in Public Interest Accounting (Vol. 3, pp. 183–193). Bingley: Emerald.

Fombrun, C. J. (1996). Reputation: Realizing value from the corporate image. Boston: Harvard Business School Press

Fombrun, C. J., Gardberg, N. A., & Barnett, M. L. (2000). Opportunity platforms and safety nets: corporate citizenship and reputational risk.

Business and Society Review, 105(1), 85-106.

Fombrun, C. J., Nielsen, K. U., & Trad, N. G. (2007). The two faces of reputation risk: Anticipating the downside losses while exploiting upside gains. Organicom,4(7), 71-83.

Fombrun, C. J., & Riel, C. van. (1997). he reputational landscape. Corporate Reputation Review, 1(1-2), 5-13.

Fombrun, C. J., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a Name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal,33(2), 233-258.

Fry, F., & Hock, R-J. (1976). Who claims corporate responsibility? he biggest and the worst. Business and Society Review, 18, 62-65.

Garriga, E., & Melé, D. (2004). Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory.

Journal of Business Ethics, (53), 51-71.

Gray, R., Kouhy, R., & Lavers, S. (1995a). Corporate social and environmental reporting:

a review of the literature and longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 8(2), 47-77.

Gray, R., Kouhy, R., & Lavers, S. (1995b). Constructing a research database of social and environmental reporting by UK companies.

Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 8(2), 78-101.

Gray, R., Owen, D., & Adams, C. (1996).

Accounting and accountability: Changes and challenges in corporate social and environmental reporting. Prentice Hall, Londres.

Gray, R., Dey, C., Owen, D., Evans, R., & Zadek, S. (1997). Struggling with the praxis of social accounting. Stakeholders, accountability, audits and procedures. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal,10(3), 325-364.

Hahn, T., & Figge, F. (2011). Beyond the bounded instrumentality in current corporate sustainability research: Toward an inclusive notion of proitability. Journal of Business Ethics,104(3), 325-345.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. he Journal of Marketing heory and Practice,19(2), 139-152.

Hair J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414-433.

Helm, S. (2005). Designing a formative measure for corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 8(2), 95-109.

Hess, D, & Ford, D. L. (2008). Corporate corruption and reform undertakings: A new approach to an old problem. Cornell International Law Journal, 41(2), 307-346.

Hines, R. (1989). he sociopolitical paradigm in financial accounting research. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal,2(1), 52-76.

Hughes, S. B., Anderson, A., & Golden, S. (2001). Corporate environmental disclosures: Are they useful in determining environmental performance? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy,3(20), 217-240.

Husillos, F. J. (2007). Una aproximación desde la teoría de la legitimidad a la información medioambiental revelada por las empresas

españolas cotizadas. Revista Española de

Financiación y Contabilidad, 36(133), 97-121.

Ingram, R., & Frazier, K. (1980). Environmental performance and corporate disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research,18(2), 614-622.

Islam, M-A, & Deegan, C. (2010). Media pressures and corporate disclosure of social responsibility performance information: A study of two global clothing sports retail companies.

Accounting and Business Research,40(2), 131-148.

King, B., & Mcdonnell, M-H. (2012). Good irms, good targets: he relationship between corporate social responsibility, reputation, and activist targeting [Working paper Series]. Recuperado de http://ssrn.com/abstract=2079227

KPMG (2013). he KPMG survey of corporate

responsibility reporting 2013. Recuperado de www. kpmg.com

Lee, M-D. (2008). A review of the theories of corporate social responsibility: Its evolutionary path and the road ahead. International Journal of Management Reviews,10(1), 53-73.

Lindblom, C. K. (1994). he implications of organizational legitimacy for corporate social performance and disclosure. Proceedings of the Critical Perspectives on Accounting Conference,

New York.

Lockett, J. & Visser, W. (2006). Corporate social responsibility in management research: Focus,

nature, salience and sources of inluence. Journal of Management Studies,43(1), 115-136.

Lukka, K. (2010). The roles and effects of paradigms in accounting research. Management Accounting Research,21(2), 110-115.

Mackenzie, S. B., Podsakof, P. M., & Jarvis, C. B. (2005). he problem of measurement model misspeciication in behavioral and organizational research and some recommended solutions.

Journal of Applied Psichology,90(4), 710–730.

Miller, P. (1994). Accounting as a social and institutional practice: An introduction. En P. Miller, & A. G. Hopwood (Eds.), Accounting as a Social and Institutional Practice (pp. 1-39). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moneva, J. M, Rivera-Lirio, J. M., & Muñoz-Torres, M. J. (2007). he corporate stakeholder commitment and social and inancial performance.

Industrial Management & Data Systems, 107(1), 84-102.

Nikolaeva, R., & Bicho, M. (2011). he role of institutional and reputational factors in the voluntary adoption of corporate social responsibility reporting standards. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,39(1), 136-157.

Nyberg, D. & Wright, C. (2013). Corporate corruption of the environment: Sustainability as a process of compromise. he British Journal of Sociology. 64(3), 405-424.

O’Donovan, G. (2002). Environmental disclosures in the annual report extending the applicability and predictive power of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 15(3), 344-371.

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., & Rynes, S. L. (2003). Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organization Studies,24(3), 403-441.

Non-financial reports, anti-corruption performance and corporate reputation

performance efects on companies that adopt the United Nations Global Compact. Sustainability,

7(2), 1932-1956. Recuperado de http://www. mdpi.com/2071-1050/7/2/1932. doi: 10.3390/ su7021932

Ortas, E., Gallego-Alvarez, I, & Álvarez, I. (2014). Financial factors inluencing the quality of corporate social responsibility and environmental management disclosure: A quantile regression approach. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 22(6), 362-380. doi:10.1002/csr.1351

Owen, D. (2008). Chronicles of wasted time? A personal relection on the current state of, and future prospects for, social and environmental accounting research. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal,21(2), 240-267.

Patten, D. M. (1991). Exposure, legitimacy, and social disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy,10(4), 297-308.

Pa t t e n , D . M . ( 1 9 9 2 ) . In t r a - i n d u s t r y environmental disclosures in response to the Alaska oil spill: A note of legitimacy theory.

Accounting, Organizations and society, 15(5), 471-475.

Patten, D. M. (2002). The relation between environmental performance and environmental

disclosure: A research note. Accounting,

Organizations and Society, 27(8), 763-773.

Peltzman, S. (1981). he efects of FCT advertising regulation. Journal of Law and Economics,24(3), 403-448.

Ponzi, L. J., Fombrun, C. J., & Gardberg, N. A. (2011). RepTrakTM pulse: Conceptualizing and

validating a short-form measure of corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 14(1), 15-35.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). Strategy and Society: the link between competitive advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility.

Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78-92.

Prado-Lorenzo, J. M., García-Sánchez I. M., & Blázquez-Zaballos, A. (2013). El impacto delsistema cultural en la transparencia corporativa.

Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 22(3), 143-154.

Rao, H. (1994). The social construction of reputation: certiication contests, legitimation, and the survival of organizations in the american automobile industry: 1895-1912. Strategic Management Journal,15(Suppl.), 29-44.

Rockness, J. (1985). An assessment of the relationship between U.S. corporate environmental performance and disclosure. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting,12(3), 339-354.

Schaltegger, S., & Synnestvedt, T. (2002). The link between “Green” and economic success. Environmental management as the crucial trigger between environmental and economic performance. Journal of Environmental Management,65(2), 339-346.

Sidhu, K. (2009). Anti-corruption compliance standards in the aftermath of the Siemens scandal.

German Law Journal, 10(8), 1343-1354.

Schuman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academic of Management Review,20(3), 571-610.

Suviri Carrasco, J. I. (2010). Conceptualización y comparación de distintos modelos de evaluación de la reputación corporativa. Cuadernos de Gestión del Conocimiento Empresarial, 22, 1-9.

Sven, T., & Hildebrendt, L. (2014). Linking corporate reputation and shareholder value using the publication of reputation rankings. Journal of Business Research,67(5), 1007-1017.

Tinker, A. (1984). heories of the state and the state of accounting: Economic reductionism and political voluntarism in accounting regulation theory. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 3(1), 55-74.

Toms, J. S. (2002). Firm resources, quality signals and the determinants of corporate environmental reputation: Some UK evidence. British Accounting Review, 34(3), 257-282.

Trotman, K. T., & Bradley, G. W. (1981). Associations between social responsibility disclosure and characteristics of companies.

Accounting, Organizations and Society, 6(4), 355-362.

Unerman, J. (2008). Strategic reputation risk management and corporate social responsibility reporting. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal,21(3), 362-364.

Villafañe, J. (2004). La buena reputación. Claves del valor intangible de las empresas. Madrid: Ediciones Pirámide.

Weigelt, K., & Camerer, C. (1988). Reputation and corporate strategy: A review of recent theory and applications. Strategic Management Journal, 9(5), 443-454.

Wiseman, J. W. (1982). An evaluation of environmental disclosures made in corporate annual reports. Accounting, Organizations and Society,7(1), 53–63.

Wu, M. L. (2006). Corporate social performance, corporate inancial performance, and irm size: A meta-analysis. he Journal of American Academy of Business, 8(1), 163-171.

Ziglydopoulos, S. C. (2001). The impact of accidents on firm’s reputation for social performance. Business and Society,40(2), 416-441.

Ziglydopoulos, S. C. (2003). The issue life-cicle: Implications for reputation for social performance and organizational legitimacy.