REVISTA

PAULISTA

DE

PEDIATRIA

www.rpped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Effect

of

interaction

with

clowns

on

vital

signs

and

non-verbal

communication

of

hospitalized

children

Pauline

Lima

Alcântara

a,

Ariane

Zonho

Wogel

a,

Maria

Isabela

Lobo

Rossi

a,

Isabela

Rodrigues

Neves

a,

Ana

Llonch

Sabates

b,

Ana

Cláudia

Puggina

a,b,∗aFaculdadedeMedicinadeJundiaí(FMJ),Jundiaí,SP,Brazil bUniversidadeGuarulhos(UnG),Guarulhos,SP,Brazil

Received16July2015;accepted2February2016 Availableonline5July2016

KEYWORDS

Non-verbal communication; Laughtertherapy; Vitalsigns

Abstract

Objective: Comparethenon-verbalcommunicationofchildrenbeforeandduringinteraction withclownsandcomparetheirvitalsignsbeforeandafterthisinteraction.

Methods: Uncontrolled,intervention,cross-sectional,quantitativestudywithchildren admit-tedtoapublicuniversityhospital.Theinterventionwasperformedbymedicalstudentsdressed asclownsandincludedmagictricks,juggling,singingwiththechildren,makingsoapbubbles andcomedicperformances.Theinterventiontimewas20min.Vitalsignswereassessedintwo measurementswithanintervalof1minimmediatelybefore andafter theinteraction. Non-verbalcommunicationwasobserved beforeandduringtheinteractionusingtheNon-Verbal CommunicationTemplateChart,atoolinwhichnon-verbalbehaviorsareassessedaseffective orineffectiveintheinteractions.

Results: Thesampleconsistedof41childrenwithameanageof7.6±2.7years;mostwere aged7---11years(n=23;56%)andweremales(n=26;63.4%).Therewasastatisticallysignificant differenceinsystolicanddiastolicbloodpressure,painandnon-verbalbehaviorofchildren withtheintervention.Systolicanddiastolicbloodpressureincreasedandpainscalesshowed decreasedscores.

Conclusions: Theplayfulinteractionwithclownscanbeatherapeuticresourcetominimizethe effectsofthestressingenvironmentduringtheintervention,improvethechildren’semotional stateandreducetheperceptionofpain.

©2016SociedadedePediatriadeS˜aoPaulo.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBYlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:apuggina@prof.ung.br(A.C.Puggina).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rppede.2016.02.011

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Comunicac¸ãonão verbal;

Terapiadoriso; Sinaisvitais

Efeitodainterac¸ãocompalhac¸osnossinaisvitaisenacomunicac¸ãonãoverbal decrianc¸ashospitalizadas

Resumo

Objetivo: Compararacomunicac¸ãonãoverbaldascrianc¸asanteseduranteainterac¸ãocom palhac¸osecompararossinaisvitaisanteseapósessainterac¸ão.

Métodos: Estudointervenc¸ão não controlado,transversal, quantitativo, comcrianc¸as inter-nadas em um hospitalpúblicouniversitário. A intervenc¸ão foifeitapor alunosde medicina vestidoscomopalhac¸oseincluiutruquesdemágica,malabarismo,cantocomascrianc¸as, bol-hasdesabãoeencenac¸õescômicas.Otempodeintervenc¸ãofoide20minutos.Ossinaisvitais foramavaliadosemduasmensurac¸õescomumintervalodeumminutoimediatamenteantese apósainterac¸ão.Acomunicac¸ãonãoverbalfoiobservadaanteseduranteainterac¸ãopormeio doQuadrodeModelosNãoVerbaisdeComunicac¸ão,instrumentoemqueoscomportamentos nãoverbaissãoavaliadosemefetivosouineficazesnasinterac¸ões.

Resultados: Aamostrafoide41crianc¸ascommédiade7,6±2,7anos,amaioriatinhaentre 7---11anos(n=23;56%)eeradosexomasculino(n=26;63,4%).Houvediferenc¸aestatisticamente significativanapressãoarterialsistólicaediastólica,nadorenoscomportamentosnãoverbais dascrianc¸ascomaintervenc¸ão.Aspressõesarteriaissistólicasediastólicasaumentarameas escalasdedormostraramdiminuic¸ãonasuapontuac¸ão.

Conclusões: Ainterac¸ãolúdicacompalhac¸ospodeserumrecursoterapêuticoparaminimizaros efeitosdoambienteestressorduranteaintervenc¸ão,melhoraroestadoemocionaldascrianc¸as ediminuirapercepc¸ãodedor.

©2016SociedadedePediatriadeS˜aoPaulo. PublicadoporElsevier EditoraLtda.Este ´eum artigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

Thejoytherapy,alsocalledlaughtertherapyorhumor ther-apy,isaknowntherapeuticmethodsincethe1960s.Itwas firstintroduced bythe AmericanphysicianHunter Adams, also called ‘‘Patch Adams’’, who since his medical stu-dentdaysalreadyusedthemethodinhospitalsandschools. Joyis likeawavethat propagatesthroughallthenerves, organs,andglandsofthewholebody.Nothingisindifferent tolaughter.Smilingand laughingarea universallanguage of communication that is expressed without words in the individual’sface.1

The smile has great power and knowing how to smile issomethingimportant.Laughterisauniquelyhuman fea-ture.Itisavitalresistancemechanismandprovidesrelease of repressed feelings for coping with stress, suffering, or pain.2Ithastheabilitytoreducetheharmfuleffectscaused

by stress in the body, because when a person laughs the parasympatheticsystem, throughtheenkephalins, actson the immune system, increases the concentration of anti-bodies,andrelievesthepaintriggeredbythesympathetic system.3

Whenlaughing,theserumlevelsofcortisoldecreaseand thebrainreleasesendorphins----substancesthatrelievepain andensurethefeelingof well-being.The heavybreathing increasestheamountofaircapturedbythelungsand facil-itatescarbondioxideoutput.Powerfulanalgesic,butalsoa producerofeuphoriaandsenseofpeace.2,4Thus,the

trans-missionofpainfulstimuliisinhibitedandthereisa‘‘residual effect’’.4

Smiling alsohassocialbenefits; itpropagatesfromone individualtoanother,improves thebondbetweenpeople, andclarifiesinterpersonalcommunication.Communication,

asclearandobjectiveasitmaybe,willalwayscontain sub-jectivitybecause itinvolves human relationships,andthe perceptionandinterpretationofverbalandnon-verbal mes-sageshappenthroughthesenseorgans:sight,touch,taste, smell,andhearing.5

Laughter is anon-verbal communicationof well-being, butthereareothersignsthatcanbeseenbyahealth pro-fessional.Noticingnotonlywhatthepatientsaysverbally, butalsothenon-verbalcues,isessentialtounderstandhim completely, not only his pathology. The non-verbal body languagehasmanymessagesforgoodobservers6by

comple-menting,substituting,orcontradictingtheverbalspeech.It isthusuptotheprofessionaltonoticethesignsandinterpret them.7

Professionals shouldseektounderstandthe childrenin theholisticsense,meettheirneeds,abilities,anddesires; itisevidentthatwhentheprofessional---patientrelationship occursefficiently, the care provided will be asbeneficial aspossible. Inevitably,therelationships thatoccurwithin thehospitalenvironmentwilldirectlyinfluencethechild’s treatment.8Playisoneoftheneedsofhospitalizedchildren

thatneedstobemet,becausethephysical,emotional, cog-nitive,andsocialdevelopmentofchildrendoesnotcease, evenwhentheyareill.9

Moreover, play gives professionals a different experi-ence withthe children, not just dealing with disabilities andlimitations.Theclowns’performancecanalsoprovide socializationandinteractionamongchildren,whichallows thecreationofnewsocialnetwork; itacts asan enabling conditiontogetoutofthesocialisolationthatsometimes hospitalizationprovides.This fact mayalso beassociated withtherecoverycondition.8Playingalsochangesthe

reality.Thus, afree and disinterestrecreationhas thera-peuticeffect.10

Inhospitalsettings,inwhichtheadmissionprocessis usu-allyanexhaustingexperience,childrenmayassociateitwith fear,grieforsenseofpunishment.Amongthemanywaysto reduce stress, improvebond, and understand the individ-ualinitsentirety,aplayfulinteractioncanbeaneffective strategyin thiscontext.A ludicbehavior provides benefi-cialeffects, such asimproving the clinical condition and reducingtheanxietyandstressofthedifficulttimeof hos-pitalstay.11 Inthissense,theludicbehavioremergesasan

importantresourcetohelpchildrencopewiththerealityof hospitalization.

Theaboveconsiderationsshowthatamongthewaysto minimizetheharmfuleffectsofhospitalizationisthe play-fulactivity,astrategythathelpsthechildtoexpresstheir feelings.Thisstudywasdoneinordertobetterunderstand the effects of playful interaction of clowns in non-verbal communicationandthephysiologicalparametersof hospi-talizedchildren.

Method

This is an uncontrolled, cross-sectional, interventional study,investigatingquantitativevariables, withvitalsigns andnon-verbalcommunicationasdependentvariables.

ThestudywasperformedinthePediatricunitofapublic universityhospitalwith24beds.Inclusioncriteriawere:(1) childrenaged2---11years;(2)admittedtothePediatricunit; (3)hemodynamicallystable;(4)awakeandwillingto partic-ipate.Childrenwithintellectualandvisualimpairmentsthat preventthemfromidentifyingthedesignoffacespainscale orinteractwiththeclownswereexcluded.

Thestudydevelopmentmettherequirementsofthe Res-olution466/2012,inforce inthecountry,ontheethicsof researchinvolvinghumansubjects,andwasapprovedbythe InstitutionalReviewBoardoftheFaculdadedeMedicinade Jundiaí,OpinionNo840.408.

DatawerecollectedfromNovember2014toMarch2015 andbeganwiththeapproachofaninvestigatordressedin ordinaryclothes: whitecoat, stethoscope, and clipboard. InformedConsentwasexplainedtotheguardiansand Con-sentTermtothechildrenover6-yearold.Childrenweretold howthemeasurement ofvitalsigns wouldbemade, with approaches according totheir developmental characteris-tics;theusedequipment(stethoscope,sphygmomanometer, thermometer,and faces painscale) were shown tothem, andacarefulapproachwasinitiatedwiththechildren. Sub-sequently,aquestionnaireofcharacterizationwasapplied, whichcontainedfivequestionsaboutthechild(age, num-berofsiblings,sex,ifattendingschool,andifthechilddoes somephysicalactivity),andvitalsignswereassessed (tem-perature,pulse,respiratoryrate,bloodpressure,andpain) in twotime points with an interval of one minute. After that,theinvestigatorthankedthechildandsaidshewould bein the room tomake notes. A previous observation of non-verbalcommunicationwascarriedoutatthistime.

The interventionwascarriedoutthroughplayful inter-action of students, members of the ‘‘League of Joy’’ of the Medical School of Jundiaí. Ludic activity is regarded asallplayfulactivitiesoranyactivityintendedtoproduce

pleasureduringitspractice;thatis,havingfun.12The

inter-vention included the work of volunteers fromthe League ofJoy andaimedtominimizethestressofhospitalization throughmagic tricks,juggling,singingwithchildren, soap bubbles,andcomedicperformances.Theinterventiontime lasted20min.

The non-verbal language during the intervention was recordedbytheinvestigatorwhocontrolledthetime. Sub-sequently,thesameinvestigatorassessedagainthefivevital signsofchildrenintwomeasurementswith1mininterval. Afterthemeasurement,the investigatorthankedthe par-ent accompanying the child, and the child himself, and departed.

Specifically,bodytemperature,bloodpressure, respira-tory and heart rate, pain, and non-verbal language were assessed. Respiratory rate was assessed by abdominal or chest observation and heart rate was measured by pal-pation at the radial artery and auscultation. For blood pressuremeasurement,anautomaticdigitalbloodpressure device Microlife Table Blue 3BTO-BP (Microlife®, Widnau,

Switzerland)andthesamebrandcuffssuitableforarm cir-cumferenceoftheparticipantswereused.Thisequipment isvalidatedandcertifiedbytheBritishSocietyof Hyperten-sion(BHS)andtheKidneyandHypertensionHospitalofthe FederalUniversityofSãoPaulo.Temperaturewasrecorded withadigitalchildren’sthermometerintheaxilla,G-Tech withflexibletip---Urso(Accumed-Glicomed®,RiodeJaneiro,

Brazil).

Forpainassessment,consideredthefifthvitalsign,13the

facespainscalethatusescharacterscreatedbyMauríciode Sousa,Cebolinha(chives)andMonica,expressingdifferent emotionalfacesineachpaingraduation.Thisscalewas cho-senbecauseitiswidelyusedinpainseverityassessmentin theBrazilianPediatricpopulation.Thescalerangesfrom0to 4,with0=nopain;1=mildpain;2=moderatepain;3=severe pain;4=excruciatingpain.14Thereweretwomeasurements

beforeand twomeasurementsafterthe intervention.For analysis,however,anaveragewasobtainedbeforeandafter foreachvitalsign.

Non-verbalcommunicationwasanalyzedusingaTableof NonverbalModels,whichconsistsofaguidelineforassessing non-verbal communication in different contexts; it is not a scale and does not have score.7 This instrument

anddown(tosayyes)andthebodyposturewasfocusedon theclownsinteractingwithhim/her.Ineffectivenon-verbal signalswereobservedwhenthechild’sposturewasstiffand tense,challengingorabsentlook,thefurnitureorobjects usedasabarrierbetweenpeople,thechild’sfacewas fac-ingtheotherside,oppositetotheclownsorexpressionless, when thechild is apathetic, sleepyor restlessduring the interaction, shook his/herhead sideways (to say no) and theposturewaslateralorbackturnedtotheclowns.7

Inmanystudiesassessingnon-verbalcommunication,itis commonthattwoobserversdotheassessmentandcompare opinions,preciselybecausethenon-verbaldecodingmaybe subjective.However,itisknownthatthemoretheindividual feelsobserved,morethisbehaviorismodulatedandbiased. Therefore,theoption wasforasingleobserverevaluation forthefollowingreasons:letthechildrenmorecomfortable tointeractwiththeclowns,causenoembarrassment,and enablethetherapeuticbenefitofthisstudy.

Quantitative data were entered into a database using Excel 2010 for later statistical analysis with the SPSS----Statistical Package for Social Science, version 23 (IBM®,Chicago,USA).Descriptive(absolutefrequency,

rela-tive,meanandstandarddeviation)andinferentialanalysis were performed. Kolmogorov---Smirnov test was used for datanormalityandparametricornon-parametrictestswere usedaccordingtodistribution.Formeancomparisonsbefore andafter vitalsigns,Wilcoxon and Student’sttests were used. McNemar test wasused to compare the change or retention of effective or ineffective non-verbalbehaviors assessedbeforeandduringtheintervention.Thistest com-paresthedifferences betweentwosamples andidentifies changesintheobservationofavariable.Thesamplesizewas basedonthenumberofchildreninstudiesofludicbehavior identifiedintheliterature.

Results

The total sample consisted of 41 children, mean age of 7.6±2.7 years,most agedbetween 7 and11 years(n=23; 56%),male(n=26;63.4%),oneortwosiblings(n=28;68.3%), attendingschool(n=38;92.7%),dophysicalactivity(n=32; 78%)(Table1).

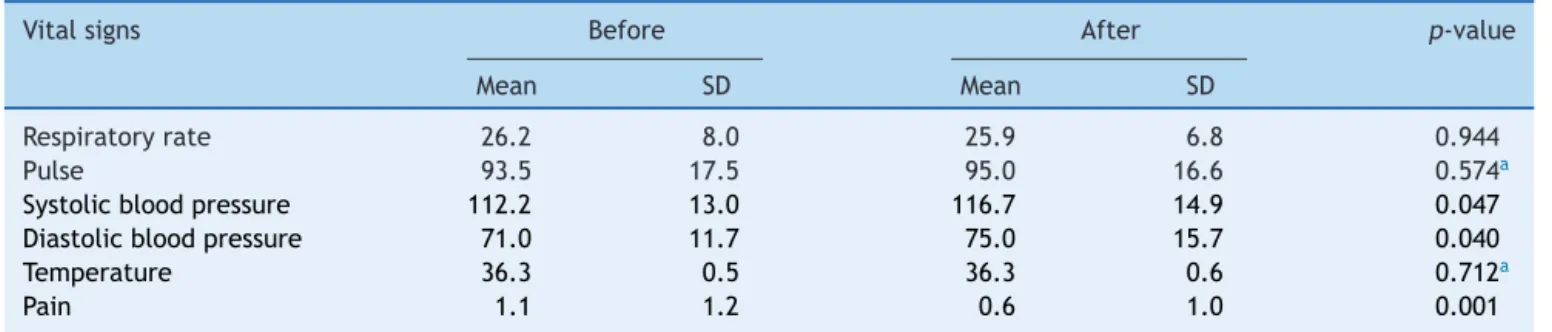

There were significant changes between the means beforeandafterinterventionwhencomparingsystolicand diastolicbloodpressuresandpain.Aftertheplayful inter-action, therewereincrease insystolicanddiastolicblood

Table1 Characteristicsofchildren.Jundiaí,2014---2015.

Variable n %

Age

3---6years 18 43.9

7---11years 23 56.1

Sex

Female 15 36.6

Male 26 63.4

Numberofsiblings

0 5 12.2

1 15 36.6

2 13 31.7

≥3 8 19.5

Attendingschool

Yes 38 92.7

No 3 7.3

Physicalactivity

Yes 32 78.0

No 3 7.3

pressuresanddecreasedpain(Table2).Onaverage,systolic bloodpressureincreasedfrom112×71to75×117andpain from1.1to0.6,apparentlynotclinicallysignificant. How-ever,itindicatesphysiologicalandbeneficialchangeswith theplayfulinteractionofchildrenwithclowns.Thatis,this resultshows thattherewasa relationship between blood pressure,pain,andplayfulactivity,asthechildrenshowed apositiveemotionalresponseevidencedbyan increasein energylevel, smilingfacialexpression, andactive partici-pationingameswiththeclowns(Tables3and4).

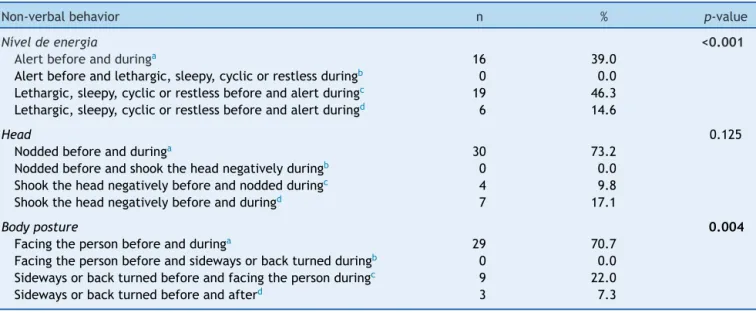

Therewerestatisticallysignificantchangesinthe com-parison of non-verbal behaviors before and during the interventionregarding posture, eye contact,use of furni-tureorobjectsintheinteraction,facialexpression,energy level,andbodyposture;thatis,insixofthesevenbehaviors observed(Tables3and4).

The non-verbal behavior changes were all ineffective toeffectivebehaviorsduringtheintervention;thatis,the previousrigidposturebecamerelaxed andattentive (n=9, 22.0%).Theabsentandchallengingeyecontactbecame reg-ular and average (n=10; 24.4%). An absent or fixed gaze is uncomfortable and can be invasive in relationships; a

Table2 Meancomparisonbeforeandaftervitalsignsassessment.Jundiaí2014---2015.

Vitalsigns Before After p-value

Mean SD Mean SD

Respiratoryrate 26.2 8.0 25.9 6.8 0.944

Pulse 93.5 17.5 95.0 16.6 0.574a

Systolicbloodpressure 112.2 13.0 116.7 14.9 0.047

Diastolicbloodpressure 71.0 11.7 75.0 15.7 0.040

Temperature 36.3 0.5 36.3 0.6 0.712a

Pain 1.1 1.2 0.6 1.0 0.001

Wilcoxontest.

Table3 Comparisonofchangeorpermanenceofeffectiveorineffectivenon-verbalbehaviorsassessedbeforeandduringthe intervention.Jundiaí2014---2015.

Non-verbalbehavior n % p-value

Posture 0.004

Relaxedbutattentivebeforeandduringa 28 68.3

Relaxedbutattentivebeforeandrigidduringb 0 0.0

Rigidbeforeandrelaxedbutattentiveduringc 9 22.0

Rigidbeforeandduringd 4 9.8

Eyecontact 0.002

Regular,averagebeforeandduringa 27 65.9

Regular,averageandabsentbefore,challengingduringb 0 0.0

Absent,challengingbeforeandregular,averageduringc 10 24.4

Absent,challengingbeforeandduringd 4 9.8

Furniture 0.016

Usedtointeractbeforeandduringa 32 78.0

Usedtointeractbeforeandusedasabarrierduringb 0 0.0

Usedasabarrierbeforeandusedtointeractduringc 7 17.1

Usedasabarrierbeforeandduringd 2 4.9

Facialexpression <0.001

Smiley,showsfeelingsbeforeandduringa 24 58.5

Smiley,showsfeelingsbeforeandturnshisfacetotheothersideorexpressionlessduringb 0 0.0 Faceturnedtotheothersideorexpressionlessbeforeandsmiley,showsfeelingsduringc 14 34.1

Faceturnedtotheothersideorexpressionlessbeforeandduringd 3 7.3

McNemartest.Assessedsituations:

aEffectiveremainseffective. b Effectivebecomesineffective. c Ineffectivebecomeseffective. d Ineffectiveremainsineffective.

Insituationsaanddbehaviorsdonotchangewiththeintervention.Insituationsbandcbehaviorsarechangedwiththeintervention.

Table4 Comparisonofchangeorpermanenceofeffectiveorineffectivenon-verbalbehaviorsassessedbeforeandduringthe intervention.Jundiaí2014---2015.

Non-verbalbehavior n % p-value

Níveldeenergia <0.001

Alertbeforeandduringa 16 39.0

Alertbeforeandlethargic,sleepy,cyclicorrestlessduringb 0 0.0

Lethargic,sleepy,cyclicorrestlessbeforeandalertduringc 19 46.3

Lethargic,sleepy,cyclicorrestlessbeforeandalertduringd 6 14.6

Head 0.125

Noddedbeforeandduringa 30 73.2

Noddedbeforeandshooktheheadnegativelyduringb 0 0.0

Shooktheheadnegativelybeforeandnoddedduringc 4 9.8

Shooktheheadnegativelybeforeandduringd 7 17.1

Bodyposture 0.004

Facingthepersonbeforeandduringa 29 70.7

Facingthepersonbeforeandsidewaysorbackturnedduringb 0 0.0

Sidewaysorbackturnedbeforeandfacingthepersonduringc 9 22.0

Sidewaysorbackturnedbeforeandafterd 3 7.3

McNemartest.Assessedsituations:

aEffectiveremainseffective. b Effectivebecomesineffective. c Ineffectivebecomeseffective. d Ineffectiveremainsineffective.

frequentlook(regular)andwithproperintensity(average) iscomfortableandfacilitatesinteractionwithothers. Fur-nitureandobjectspreviouslyusedasabarrier(e.g.,sheet overtheheador coveringmuchofthebody)wereusedto interact or were removed (n=7; 17.1%). The child’s face, turnedpredominantlytoasideoftheroomor expression-less,changedtoasmilingfaceinthepresenceofclownsand showedfeelings(n=14;34.1%).Theenergylevel,previously lethargic, sleepy, cyclic or restless, became alert (n=19; 46.3%).Finally,thechild’sbodyposture,initiallyobserved onsidewaysorbackturned,facedtheclowns,showed open-ness and acceptance in interpersonal relationships (n=9; 22.0%)(Tables3and4).

Thenon-verbalbehavioralchangesfoundwiththe inter-vention show the effectiveness of playful activities with clownsasa therapeuticresource.Ingeneral,thechildren weremorerelaxed,open,andsmiley.Theinterventionwas abletomodifytheinitialcontext.

Discussion

In this study, the investigators sought to make a close contact, humanized, and individual withchildren, as the visitsweremadeinsidetheroomwheretheywerestaying andthegamesfloweddifferentlyineachvisit.The impor-tanceofthisformofplayfulinteractionhasbeenshownina studyconductedinAustralia,inwhichvideoconferencewas heldtopromoteinteractionbetweenclownsfromRoyal Chil-dren’sHospitalwithchildrenhospitalizedorathome.The experiencehasshownthatinteractionbetweenclownsand institutionalizedchildrenviavideoconferenceistechnically feasible andpractical. However,it would benecessary to makeindividualgamesforeachchild,somethingthatwould beeasierpersonally.Inthisscenario,theonlineinteraction wasmorelimited,butitisnolongeranoption.15

Literature studies16,17 report convergent results with

thosefoundbyus.Theplayfulinteractionofchildrenwith clowns,asshowninthisstudy,wasaneffectivestrategyof redirecting the energyof children to positive and benefi-cialfeelings.Thenon-verbalbehavioralchangesduringthe intervention showed that children become more relaxed, attentive, and smiley. A study wasperformed in Portugal with70children,aged5---12years,dividedintotwogroups for preoperative outpatientmonitoring.In onegroup, the childrenweremonitoredintheroombytheirparents and twoclowns;intheothergroup,theyweremonitoredonly by theirparents. The ChildSurgeryWorries Questionnaire wasusedtodescribethepatients’distress.Children moni-toredbyclownswerelessworriedwithhospitalizationand medicalprocedures,lessconcernedwiththediseaseitself, andfelthappierandcalmercomparedtotheothergroup.16

In another case---controlstudy, 60 children, aged6---10 years,whowerescheduledfor surgery,wererecruited.Of these, 30 would receive a visit from two clowns before surgery (case group)and 30 wouldnot receive it (control group). Anxiety wasmeasured using thefollowing scales: State Trait Inventory Anxiety for Children, Community-Campus Partnerships for Health, and Faces Pain Scale, after the performance of clowns and up to seven days aftersurgery.Bothgroupsshowedincreasedanxiety,butin

the group of children undergoing clown intervention, the increasedanxietywaslessimportant.17

Similarresultstothepresentstudyregardingblood pres-surewerefoundinastudyperformedinJapan.Seventeen apparentlyhealthyadults,aged23---42years,watcheda 30-mincomedy(experimental)andadocumentary(control)on differentdays.Heartrateandbloodpressureincreased sig-nificantlywhilethe subjectswatchedcomedy,therewere nosuchchangesduringthedocumentary.18Laughterandjoy

causeexcitementandwell-being.

The relationship between humor and painwas studied with80participants,aged18---44years.Inthisinvestigation, thecoldstimulationwasmadewithwatermaintainedat1◦C

byan immersionchiller and circulation byan underwater mixer.Ontopofthewatertherewasanarmrestingplace onwhichtheparticipantheldtheleftarm.Participantswere dividedintofourgroupsof20.Group1watchedahumorous film,Group 2 watched a repulsivefilm, Group 3 watched aneutral film, and Group 4 had nofilm towatch. State-TraitAnxietyInventory,HumorQuestionnaire,measurement itemsforself-efficacyfor paincontrol,visualanalog scale foranxiety,andapost-experimentquestionnairewereused. Paintolerancesignificantlyincreasedwithhumor.19

Inadditiontothe behavioralandphysiological effects, thebenefitsofinteractingwithclownsarenotrestrictedto patients;familyandprofessionalsseemtoalsobenefit.20---22

Literaturestudiesconfirmthisfinding,andthisperception wasalso corroborated in the current study, although not documented,asboththeteamandhealthprofessionals ver-balize their praise for the research initiative and to the students members of the League of Joy. Interaction with clownsinterferesin awholecontext inwhich thechild is placed.Anexampleofthiswasfoundinastudyperformed inGermany,inwhichoneoftheobjectiveswastoevaluate theperformance ofclowns bythe parents ofhospitalized children andby the hospital staff.The study included 37 parentsand43staff,andasatisfactionscaleand monitor-ingat theactingfieldwereapplied.Boththeparentsand thestaffreportedthattheyandpatientsbenefitfromthe intervention.20

An ethnographicstudy was performed toassess princi-ples,values,andmethodologyoftheAssociac¸ãoOperac¸ão Nariz Vermelho (Red Nose Operation Association) during visits to hospitalized children. The results show a strong relationshipofempathyandcomplicitybetweentheClown Doctorsandthechildren,aswellasastrongsenseof belong-ing,onthepartofartists,tothehospitalcommunity,visible in the relationship established with professionals and in deliveringa qualitycare thatprovideswell-beingandjoy. Thissenseofsharingandcreatingtiesextendsalsotothe children’srelatives,whoactaschannelsofcommunication betweentherelationshipClownDoctorandthechild.21

anddemystification of health professionals. However,the reporteddisadvantageswerepanicorfearofclownbysome children,littlereceptivityduetosuffering,andresistance tothepresenceofclownsbyadolescentsduetothe child-ishnessinvolved.22

Finally, the survey of this intervention disadvantages22

bringstodiscussiontherecognitionoflimitationsregarding theplayfulinteractionwithclowns,suchasthefearofclown arisingmainlyfromfantasies,whichmakesitessentialthat professionalsinvolvedinplayfulactivitieswithclownsshow sensitivity,commonsense,andrespectforchildrenandtheir negativereactions(crying, screaming,refusaltoplaywith clown)inordertobereallybeneficialandtherapeutic.

Despite its limitations, such as observational bias (a singleobserverassessedthebehaviorandappliedthe non-verbal behavior scale), option for the application of a non-validated instrument,and measurement bias (lack of vital signs continuous measurement), the study has out-comesindicating that theplayful interactionwith clowns canbeatherapeuticresourcetominimizetheeffectsofthe stressorenvironmentduringtheintervention,improvethe emotionalstatusofchildren,andreducepainperception.

Funding

ScientificInitiationstudyfundedbytheConselhoNacional deDesenvolvimentoCientíficoeTecnológico(CNPq).Process No152551/2014-0.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.LambertE.Terapiadoriso:acurapelaalegria.SãoPaulo: Edi-toraPensamento;1999.

2.MunizI.Aneurociênciaeasemoc¸õesdoatodeaprender:quem nãosabesorrir,danc¸arebrincarnãodeveensinar.Itabuna:Via Litterarum;2012.

3.JaimesJ,ClaroA,PereaS,JaimesE.Larisa,uncomplemento esencialenlarecuperacióndelpaciente.MedUIS.2011;24:1---6.

4.ValeNB.Analgesiaadjuvanteealternativa.RevBrasAnestesiol. 2006;56:30---55.

5.SchellesS.Aimportânciadalinguagemnãoverbalnasrelac¸ões delideranc¸anasorganizac¸ões.RevEsfera.2008:1---8.Available

from: http://www.fsma.edu.br/esfera/Artigos/ArtigoSuraia. pdf[cited03.06.15].

6.SenaAG[Master’sthesis]DoutoresdaAlegriaeprofissionaisde saúde:opalhac¸odehospitalnapercepc¸ãodequemcuida.Belo Horizonte(MG):UFMG;2011.

7.Silva MJ. Comunicac¸ão tem remédio: a comunicac¸ão nas relac¸õesinterpessoaisem saúde. 8th ed.São Paulo: Loyola; 2012.

8.OliveiraRR,OliveiraIC.Osdoutoresdaalegrianaunidadede internac¸ãopediátrica:experiênciasdaequipedeenfermagem. EscAnnaNeryRevEnferm.2008;12:230---6.

9.HokenberryMJ,WilsonD.Wong:fundamentosdeenfermagem pediátrica.8thed.RiodeJaneiro:Elsevier;2011.

10.MottaAB,EnumoSF.Brincarnohospital:estratégiade enfrenta-mentodahospitalizac¸ãoinfantil.PsicolEstud.2004;9:19---28.

11.Melo AJ. A terapêutica artística promovendo saúde na instituic¸ãohospitalar.RevInterdiscipEstudosIbéricose Ibero-Americanos.2007;1:142---67.

12.RezendeJA[Master’sthesis]Asatividadeslúdicasselecionadas, aplicadasacrianc¸acomdeficiênciaauditiva,comomedida ter-apêuticaparaocontroledaansiedade.SãoPaulo:ISET;2010.

13.BoossJ,DrakeA,KernsRD,RyanB,WasseL.Painasthe5th vitalsigntoolkit.Illinois:JointCommissiononAccreditationof HealthcareOrganizations;2000. Availablefrom:http://www. va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/docs/PainAsthe5thVitalSign Toolkit.pdf[cited18.01.16].

14.ClaroMT[Master’sthesis]Escaladefacesparaavaliac¸ãodador emcrianc¸as:etapapreliminar.RibeirãoPreto(SP):USP;1993.

15.ArmfieldNR,BradfordN,WhiteMM,SpitzerP,SmithAC.Humor sansfrontieres:thefeasibilityofprovidingclowncareata dis-tance.TelemedJEHealth.2011;17:316---8.

16.FernandesSC,ArriagaP.Theeffectsofclowninterventionon worriesandemotionalresponsesinchildrenundergoingsurgery. JHealthPsychol.2010;15:405---15.

17.Cantó MA, Quiles JM, Vallejo OG, Pruneda RR, Morote JS, Pi˜neraMJ,etal.Evaluationoftheeffectofhospitalclown’s performance aboutanxiety in childrensubjected to surgical intervention.CirPediatr.2008;21:195---8.

18.SugawaraJ,TarumiT,TanakaH.Effectofmirthfullaughteron vascularfunction.AmJCardiol.2010;106:856---9.

19.TepperI,SchwarzwaldJ.Humorasa cognitivetechniquefor increasingpaintolerance.Pain.1995;63:207---12.

20.Barkmann C, Siem AK, Wessolowski N, Schulte-Markwort M. Clowningasasupportivemeasureinpaediatrics-asurveyof clowns,parentsandnursingstaff.BMCPediatr.2013;10:166.

21.SantosAI [Master’s thesis] De narizvermelho no hospital: a actividadelúdicadosdoutorespalhac¸oscomcrianc¸as hospital-izadas.Braga(PT):Uminho;2011.