The Cost of Public-Private Partnerships for the Public

Partner: The Road Sector in Portugal

Mafalda de Sousa Trincão (152211008)

Supervisors: Joaquim Sarmento, Pedro Raposo and Ricardo Reis

Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of MSc in Economics, at the Universidade Católica Portuguesa, March 2014.

I The Cost of Public-Private Partnerships for the Public Partner: The Road Sector in Portugal

Mafalda de Sousa Trincão Abstract

Nowadays, the high costs that the Portuguese State is bearing with Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) are often in the headlines of the Portuguese newspapers. In this context, the purpose of this dissertation is to analyse the predicted costs with PPPs projects for the public partner in the road sector. Since, over the last years, the National State Budgets has presented different predictions regarding the cost that the State will bear during 2014-2031.

Therefore, I had as objective to assess if there are reasons that explain those differences. To accomplish this objective, I investigated each project and each State Budget.Through this data analysis, I verified that during the period that was studied (from the State Budget of 2005 to 2014), new projects with expected costs for the public partner were launched, and there were renegotiations of the contracts. Thus, these are some of the reasons for the differences observed. Then, I identified factors that affect the predicted costs through econometric analysis. The model has as dependent variable the Present Value of the predicted costs for each project in each State Budget, and I concluded that they are affected by the changes on the model of payment, by the economic context and by the fact that Portugal was in the last years under a Financial Assistance Programme. Moreover, with this dissertation, I identified some challenges for the public partner with the PPP model. One of the main aspects that has to be improved is the transparency. The State Budgets should disclose more information and mainly explain significant deviations from the previous ones.

Resumo

Nos dias de hoje, os elevados custos suportados pelo Estado com Parcerias Público-Privadas (PPPs) são muitas vezes manchetes dos jornais portugueses. Neste contexto, o objetivo desta dissertação é analisar os custos previstos com PPPs do sector rodoviário para o parceiro público. Uma vez que, ao longo dos últimos anos, os Orçamentos de Estado apresentaram diferentes previsões em relação aos custos que o Estado terá que suportar durante 2014-2031.

Assim sendo, pretendi encontrar explicações para essas diferenças. De forma a concretizar esse objetivo, analisei cada projecto e cada Orçamento de Estado (OE). Com esta análise de dados, verifiquei que durante o período analisado (do OE de 2005 ao de 2014), novos projectos com custos esperados para o parceiro público foram lançados, e que houve renegociações de contractos. Assim, estas são algumas das razões para as diferenças observadas. Depois identifiquei fatores que afetam os custos previstos via análise econométrica. O modelo tem como variável dependente o Valor Actualizado dos custos previstos para cada projecto em cada OE, e concluí que são afectados pelas mudanças do modelo de pagamento, pelo contexto económico e pelo facto de Portugal ter estado nos últimos anos ao abrigo de um Programa de Assistência Financeira. Com esta dissertação identifiquei alguns desafios para o parceiro público com o modelo de PPP. Um dos principais aspectos a melhorar é a transparência. Os Orçamentos de Estado devem divulgar mais informação e, principalmente, explicar os desvios mais significativos relativamente a estimativas anteriores.

II

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments ... IV Acronyms ... V 1. Introduction ... 1 2. Literature Review ... 32.1. Overall overview of concepts ... 3

2.2. Challenges regarding PPPs ... 6

2.2.1. The Role of the State ... 6

2.2.2. Risk ... 7

2.2.3. Transparency ... 8

2.2.4. Accountability, Affordability and Budgeting ... 9

2.2.5. Renegotiations and FRAs ... 13

2.3. PPPs in Portugal ... 14

2.3.1. Financing of projects and Costs for the State ... 15

2.3.2. Road Sector ... 15

3. Methodology and Data Collection ... 18

3.1. Data Collection ... 18

3.2. Econometric Analysis ... 20

3.2.1. Independent variables ... 20

4. Analysis of Results ... 27

4.1. Analysis of each project individually... 27

4.2 Analysis of each State Budget ... 34

4.3 Analysis of the econometric model ... 36

5. Conclusion ... 41 References ... 43 Appendixes ... 47 1. TIP vs PPP ... 47 2. Risks ... 48 3. Contingent liabilities ... 49

III

4. The process of renegotiation in Portugal ... 50

5. Summary of the History of PPPs ... 50

6. Concession ... 51

7. Estradas de Portugal, S.A... 51

8. Costs for the State with PPPs in the railway and health sectors ... 52

8.1. Railway Sector ... 52

8.2. Health Sector ... 52

9. Contract of Costa de Prata after renegotiation ... 53

10. Contract of Transmontana... 53

13. Launch date of projects ... 54

IV

Acknowledgments

First of all, I would like to thank to my supervisors for the valuable guidance. To Professors Joaquim Sarmento and Ricardo Reis, I thank all the motivation and their enthusiasm towards the theme of my dissertation. It was in fact a source of energy and incentive to complete this project. To Professor Pedro Raposo, I would like to thank for his precious support with the econometric model and all his availability to teach me. In addition to them, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor Teresa Lloyd-Braga for all the support during my Masters programme.

Moreover, I thank Professors Leonor Modesto, Ricardo Reis and Teresa Lloyd-Braga for the opportunity of doing an internship in the OECD. This was an unforgettable experience that exceeded all my expectations. There, I was able to I learn a lot about the reality of Public-Private Partnerships around the world. In this context, I would like to emphasize that the welcoming environment in the GOV-BUD division and the sympathy of the members of the OECD’s Portuguese Delegation contributed greatly to my integration. A special thanks to Mr. Ian Hawkesworth for being always available to guide me on every issue.

I would also like to thank to Dr. António Palma Ramalho and Dr. Joaquim Pais Jorge for the data they have provided me with, without it the main objective of this dissertation would not be accomplished.

To all my colleagues and friends at Bank of Portugal, with whom I discussed about the topic of my thesis, I thank the useful insights that allowed me to improve my work. To Madalena Jacinto, I thank the long hours that we worked together that made this phase less difficult. I also want to thank Rafael Barbosa and Sofia Saldanha for their comments on this dissertation. Finally, and most importantly, I would like to thank my family. To my father I thank for being always an example of excellence, to my mother for her unconditional support, to Marta for being more than a sister and to the rest of my family for all the caring and love. Also, a special thanks to André for his patience and help during all these last months.

V

Acronyms

CASNS- Centro de Atendimento do Serviço Nacional de Saúde CMFRS- Centro de Medicina Física e Reabilitação do Sul CPI - Consumer Price Index

DBFOT – Design-Build-Finance-Operate-Transfer DGO- Direção-Geral do Orçamento

DGTF- Direcção-Geral do Tesouro e Finanças DSCR- Debt-Service Coverage Ratio

ECB- European Central Bank EP- Estradas de Portugal, S.A. EU- European Union

E&Y- Ernst & Young

FRAs- Financial Re-equilibrium Agreements GDP- Gross Domestic Product

InIR- Instituto de Infra-Estruturas Rodoviárias I.P IRR- Internal rate of return

M€- Million Euros

MST- Metro Sul do Tejo (the subway of the south of the river Tagus) NAO- National Audit Office (Tribunal de Contas- TdC)

NHS- National Health System

NMGFSR- Novo Modelo de Gestão e Financiamento do Sector Rodoviário NPV- Net Present Value

OECD- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development O&M- Operation & Maintenance

PPP- Public-Private Partnership PSC- Public Sector Comparator PV- Present Value

SB- State Budget

SCUT- Sem Cobrança aos Utilizadores (roads with shadow tolls) TIP- Traditionalinfrastructure procurement

UK- United Kingdom

USA- United States of America

UTAP- Unidade Técnica de Acompanhamento de Projetos VAT- Value Added Tax

1

1. Introduction

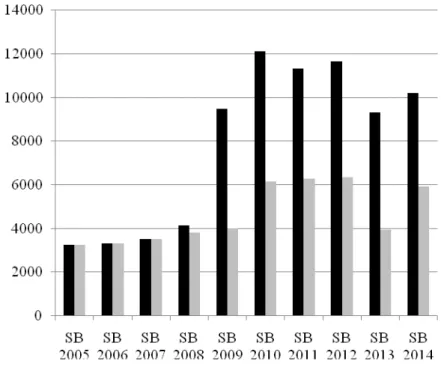

Over the last years, in Portugal, there has been a considerable debate in the media and at a political level regarding Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs). The costs supported by the State1 are considered too high and unaffordable. Therefore, it is important to understand if they were expected in the State Budgets (SBs). By observing the predicted costs presented in different State Budgets for the same period of time and for the road sector, I verified that those predictions vary from one SB to another. For example, the figure 1 presents the predicted costs for the State with PPPs in the road sector from 2014 to 2031 in two different State Budgets, the SB 2006 and 2009. Thus, if I am analysing the costs for the same period of time, I would expect that those lines overlap, in other words, the predictions should be equal. In fact, the evolution of the costs is similar, but the values are higher in the SB 2009.

Figure 1: Predicted costs during 2014-2031

X-axis: Years

Y-axis: Predicted costs for the State (M€)

2 Other approach in observing these differences is by summing the discounted predicted costs per SB, and in this way I obtained the PV of the predicted costs for each SB, as observable in the graph below:

X-axis: SBs

Y-axis: PV of predicted costs for the State (M€)

Observing this graph I could also verify the differences from one SB to another. For example, comparing the present value (PV) of the predicted costs presented in the SB of 2006 and of 2009, there is a difference of 6 170 M€2. Why are they different?

In this context the main objective of this dissertation is to find the explanations behind the predictions presented in the Portuguese State Budgets regarding the cost that the State will bear during 2014-2031. Thus, I will aim at answering the questions: How can one explain different predictions regarding how much the State will spend during the same period of time? Which factors can affect the predictions?

One of the explanations may be related to the launch of new projects. If there is a new project, this may increase costs. Other reason would be renegotiations. There are examples of PPPs that were renegotiated, and this had a significant impact on the financial responsibilities of the State. Moreover, the economic and political situation during the preparation of each SB may also affect the predictions. These possible reasons are further on analysed in this dissertation.

In order to answer the main question of this dissertation, I will firstly analyse each PPP in the road sector (24 projects) and each State Budgets (10 SBs, from the SB 2005 to 2014). This way, I will be able to recognize the main events regarding PPPs in the road sector. Then, I will compute an econometric model based on panel data, on which I will identify the variables that affect the predictions. Since State Budgets only present the total predicted costs for the road sector, this analysis will be based on data on costs per project, provided by Estradas de Portugal.

2 The PV of the predicted costs in the State Budget of 2009 is 9 487 M€, and of 2006 is 3 317 M€. (In the section Methodology and

Data Collection it is explained how these values were computed).

3

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overall overview of concepts

PPPs refer to a model applied by governments to finance public investment. Actually, there is not a single definition for this type of model. As defined by the OECD, they are “an agreement between the government and one or more private partners (which may include the operators and the financers) according to which the private partners deliver the service in such manner that the service delivery objectives of the government are aligned with the profit objectives of the private partners and where the effectiveness of the alignment depends on a sufficient transfer of risk to the private partners” (OECD, 2008). Since Portugal is the case study of this dissertation, the definition of PPP by the Portuguese Law is the following: “a contract by which private entities undertake, for a long period, the responsibility of ensuring the development of an activity aimed at satisfying a collective need. The financing, the investment and the operation of the project are responsibilities, in whole or in part, of the private partner” (Decree-Law n. 86/ 2003 of 26th of April3). Summarizing, all definitions of PPPs refer to them as a public-private relationship, based on a contract and on risk sharing in a more complex way than traditional infrastructure public procurement (TIP)4.

Actually, a PPP is a model of delivering public services that is being increasingly used in several countries in order to face current main challenges. For instance, in developing countries, needs regarding infrastructure and services have not been satisfied, and this has compromised the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. On the other hand, developed countries have to face the growing demand for more infrastructures, the need to improve public services and the need to upgrade public infrastructure due to the ageing of assets (OECD, 2007). So, what is the solution? Governments could invest heavily in infrastructure and service delivery. However, there are budget constraints to bear in mind which cannot be ignored. To recap the first lesson in economics, there are limited resources and unlimited needs: all governments must still find the financial means to supply public infrastructure. Furthermore, some countries deal with fiscal pressures concerning the reduction of public debt and fiscal deficits (OECD, 2007

3 A few remarks on this Decree-Law:

Translated by the author from the original Portuguese version:

“Contracto ou a união de contractos, por via dos quais entidades privadas, designadas por parceiros privados, se obrigam, de forma duradoura, perante um parceiro público, a assegurar o desenvolvimento de uma actividade tendente à satisfação de uma necessidade colectiva, e em que o financiamento e a responsabilidade pelo investimento e pela exploração incumbem, no todo ou em parte, ao parceiro privado”

This Decree-Law was the first legal regulation regarding PPPs in Portugal, and established the characteristics and rules concerning the launch of PPPs. It is worth to mention that the majority of the contracts were signed before the publication of it. Therefore, the PPP’s boom in Portugal was without a specific legal framework (Moreno, 2010).

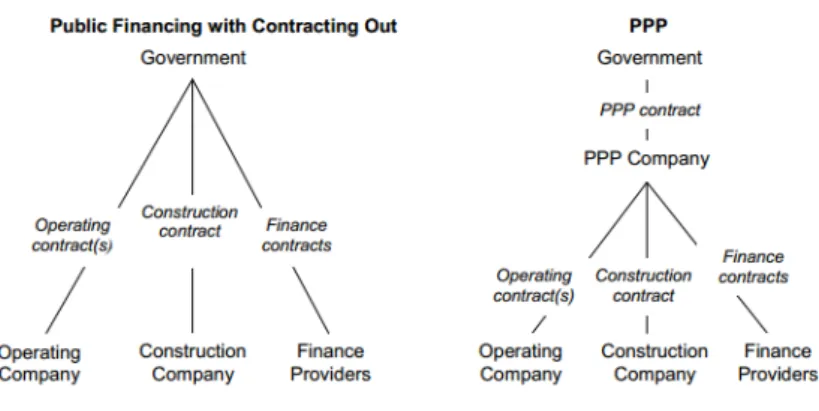

4 Traditional Infrastructure Procurement: governments pay to private companies for the construction of certain infrastructures. In

the end of the construction’s period, the asset belongs to the government, and it is responsible for its operation (OECD, 2013). In Appendix 1, the differences between the contracting and financing structure of a TIP and a PPP concession, are presented. PPPs: “arrangements where the private sector supplies infrastructures assets and infrastructure-based services that traditionally have been provided by the government” (Corbacho, Funke et Schwartz, 2008).

4 and 2008; Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009). PPPs, as an alternative to TIP, have proven5 to be a good choice when governments deal with a strict financial constraint and the service delivery role6. In these situations, the financing from the private sector, sometimes, seems the cheapest or even the only way to finance a project. In extreme situations, governments only have two options: apply the PPP model or “no infrastructure” (OECD, 2007). In fact, “when national budgets are on bread-and-water diets, PPPs are like a parcel of cheese and sausage under the floorboards”7. Some governments only apply the PPP model when they have neither revenues nor the credit to finance investments in public goods and services8. On one hand, this is a reason for the increasing use of PPPs. But, on the other hand, it is one of the biggest problems. Summarily, the reason for applying PPPs should not be the demand for financial miracle solutions or financial engineering to launch projects. Contrarily, it should be a feasible solution among other alternatives, and should only be applied when its advantages for the public sector are proven by a cost-benefit analysis (Cardoso, 2011; Arroja, 2012).

Apart from that, there are other reasons for using PPPs, which provide potential9 benefits for the economy. For instance, the share of know-how and resources between the private and public sector, which may lead to a more effective, efficient10, flexible and faster way of maximizing collective satisfaction. The differences between these two types of partners may lead to a healthy marriage (Dochia et Parker, 2009; Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009; Cardoso, 2011; OPPP, 2011). Actually, the benefits obtained from the technical and specialized capacities in construction and management of services of private partners comes as one of the main potential advantages. These benefits encompass the improvement of supplied goods and services and/or the possibility of creating savings of public resources, which provides greater fiscal margin11 (Grimsey et Lewis, 2004; OECD, 2007 and 2008; Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009; Cardoso, 2011). In addition to this, in comparison to a TIP, a PPP may provide more incentives for the private sector to deliver a better job. With the TIP model, the private sector is involved only in the construction, and afterwards, the public sector is solely responsible for the maintenance.

5 At least, according to some members of governments, and at idealistic terms. However, as it will be explained in this dissertation,

this model of financing was not always a good idea. In some cases, they have proven not to be a good idea, or, a good idea that was not well implemented.

6 According to the information in the SB 2006, the Portuguese Government was interested in increasing the number of projects with

high levels of investment using the PPP model, in order to deal with the public financial situation at the time (SB, 2006). 7 Source: OECD Observer No 278 (2010)

8 Public good: there are some goods and services that do not create profits, so they will never be offered by the private sector. In

fact, the objective of this sector is the maximization of profits. However, these good and services create positive externalities for the economy as a whole. These are two reasons why they have to be offered by the State (Arroja, 2012; Sarmento, 2013).

9 Some assumptions must be verified for a PPP to prove its real advantages (Cardoso, 2011). 10 A few remarks on Effectiveness and Efficiency:

Effectiveness: the intended quantity is delivered (OECD, 2008). Efficiency: It is delivered at least cost (OECD, 2008).

“The involvement of private operators has its main advantage over publicly run projects when there is a potential to take advantage of the private operators’ operational and administrative efficiencies (such as the technical expertise and the managerial competences of commercial operators), increased competition and enhanced services to end-consumers” (OECD, 2007). For example, efficiency can be improved because of the ability of the private partner to impose user charges, which may be not easy for the government. Moreover, the private partner may easier align the price with costs. In this way, inefficient demands are reduced (Schwartz, Corbacho et Funke, 2008 and Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko 2009).

11 “The purpose of this collaboration is to bring added value to infrastructure through innovation, enabling the government to deliver

5 Therefore, the private sector partner may purposely fail to perform in accordance with the desirable quality and without delays, because this may imply more profits. By not delivering a good job, the infrastructure may need an improvement in the future, which can lead to an additional contract with the same private entity. The other possible situation is if the State decides to cut in maintenance costs. In fact, this is usually the case in periods of austerity. Therefore, the operation of the infrastructure is not improved. Contrarily, with a PPP, the private sector starts receiving payments only when the operational stage starts, so it is not interested in delays during the construction period. Additionally, it would want to avoid high lifecycle costs (future O&M cost), which justifies a focus on higher quality12. In conclusion, to pursuit this objective, the private partner “boosts both the coverage and efficiency of infrastructure services” (OECD, 2007) and it may invest in cost-saving technology. Thus, it may have incentives to incur in higher costs initially, in order to reduce future costs13 (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009; Burger et Hawkesworth, 2011; Cardoso, 2011). Other advantage of the PPP model is that it reduces the domain of the governmental action. In other words, with these projects, the State is not responsible for all the proceedings, such as planning, financing, construction, management and maintenance. Thus, the risks associated with all these stages are not fully borne by the State. In other words, there is risk sharing. Summarily, the main advantages for the public partner would be the risk sharing, the possible high value for money, if the private partner has more skills, and consequently, if it can face the additional financing costs of private interest rates (Schwartz, Corbacho et Funke, 2008; Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009; Cardoso, 2011). For the private partner, an advantage of the PPP model is the opportunity of new businesses. It is the possibility of working in areas that previously were only of the governments’ responsibility; and, at the same time, obtaining high remunerations (Schwartz, Corbacho et Funke, 2008; Moreno, 2010).

However, aligning public and private interests is not always possible, since sometimes there are goal conflicts. It is easier to deal with this, if the infrastructure leads to more productivity for the private partner. Contrarily, “the more a service takes on the character of a public good, the less private incentives will be congruent with public interest, leading to greater public disappointment with the results” (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009). Generally, their different interests lead to uncertain relations, “characterized as bargaining relationships in which both partners have independent sources of leverage over the other”, which therefore, may affect the

12 Examples: “PPPs, in fact, have shown some early gains in construction timeliness and costs. The United Kingdom National Audit

Office reports that PPPs are delivered on time and on budget more often than traditional arrangements. Traditional infrastructure is on time and on budget 30% of the time, while PPP projects are on time and on budget over 75% of the time (Hodge and Greve, 2007, p. 549). Michael Pollitt also concluded that PPPs deliver on time and on budget a higher percentage of the time. While public agencies could do this too, they needed PPPs to stimulate and innovate (Pollitt, 2005). Beyond this, some studies have shown that PPPs were less costly in the United Kingdom for prisons and roads. The National Audit Office predicted that a sample of projects studied in the 1990s experienced cost savings of 10%, attributable to risk transfers from public to private firms (Hodge and Greve, 2007)” (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009).

13 This only happens if the NPV of the future savings is higher or equal than the NPV of the additional initial costs (Burger et

6 achievement of public goals (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009). In fact, PPPs, unfortunately, are not regarded as a bed of roses. Most of the problems that arise are related with the costs with PPPs for the State: they may encumber more SBs. In fact, there are different problematic situations in different countries. That is why some international institutions have already published recommendations14 regarding transparency, affordability, accountability, risk sharing, etc. of PPP’s projects. These are core areas to which some of those problems are related to. In section 2.2, the problems related to these areas, which directly or indirectly affect the costs for the State, are deeply analysed.

2.2. Challenges regarding PPPs

2.2.1. The Role of the State

As aforementioned, a PPP has an inherent complex relation, which involves two distinct entities in a contract during a long period. These entities have different objectives and interests, and historically, they are not compatible (for example, maximization of profits vs social interest) (Bult-Spiering et Dewulf, 2006; OECD, 2008; Cardoso, 2011; OPPP, 2011). Therefore, cooperation is crucial. In this context, the word partnership does not mean that the involved parties share the same objectives. It means that, although their objectives are different, they are able to align them in order to achieve the objectives of both partners (OECD, 2008).In addition to this, the State cannot forget its responsibilities. Although some work is transferred to the private partner, the Government is still responsible for the performance of the project (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009).

In order to deal with the problem of goal conflict and accomplish with its main responsibility of acting in favour of the public interest, the public partner should have “a competent, equitable and diligent attention to contracts, regulation and legal frameworks” (OECD, 2007). In fact, regarding competence, there are examples of situations that prove that the public partner is not prepared to deal with PPPs (OECD, 2007). In Portugal, for instance, it is mentioned that the State has a deficit of capacity to monitor, supervise, control and follow the contract of PPPs’ projects (Tribunal de Contas, 2003; Assembleia da República, 2013). Therefore, the Government needs to develop and/ or improve its skills to be able to deal/negotiate with the private partner, who is considered to have better competencies (OECD, 2007)15. That is why the National Audit Office (NAO) in 2013 emphasized the need to have specialized personnel and sufficient number of people to monitor a pari passu all projects in all its aspects (cited by

14 One example is the book “Recommendation of the Council on Principles for Public Governance of Public-Private Partnerships”

(OECD, 2012)

15 Although, “a PPP is a better option if the government does not itself possess the requisite skills to construct and operate the

project”, when it chooses the PPP model, “it will nevertheless need skilled staff to monitor the private partner and to manage its own responsibilities and risk” (Burger et Hawkesworth, 2011). Therefore, “authorities need to build the necessary competencies to act as an equal partner to the private sector participants” (OECD, 2007). As Sarmento said, it is important to improve the capacities of the public sector to negotiate, since he thinks that they are really weak (Diário Económico, 2012).

7 Assembleia da República, 2013). The costs associated with the development of competencies should be included in the design of the project (OECD, 2007).

2.2.2. Risk

Risk is “any factor, event or influence that threatens the successful completion of a project in terms of time, cost or quality” (European Commission, 2003). In the TIP model, risks are fully allocated to the public sector. Whereas, one of the characteristics of the PPP model is that some risks can be transferred to the private sector. When a certain event occurs, the entity, to whom the risk related to that event was allocated, has to bear the cost. In other words, if a certain risk is allocated to the public partner, it has a higher responsibility over that risk. On one hand, the public partner would want to transfer risks to the private partner, since its responsibility is reduced. On the other hand, the private partner charges a price for dealing with risks, and the price increases with the exposure to more risk. In addition to this, the price is also linked to the risk-aversion profile of the private partner. The higher the risk aversion of the private partner, or the lower its capability to deal with the risk, the higher the cost will be (Cardoso, 2011). Actually, risk has a direct impact on the financial cost of a PPP (European Commission. 2003). Therefore, the allocation of risks should be balanced. Actually, a good allocation may contribute to a better Value for Money (VfM), since the private partner has higher ability to deal with certain risks (European Commission, 2003; OECD, 2008; Cardoso, 2011). VfM is the difference between the costs for the State using TIP and using PPP, via the calculus of the Public Sector Comparator (PSC). Thus, it is linked to savings for the public partner that can be achieved by applying the PPP model (Cardoso, 2011). However, VfM does not only include quantitative, but also, qualitative aspects, such as, the government’s judgment regarding what the best combination of quality, features and price is. Summarily, it refers to the highest quality at the best price (OECD, 2008 and 2013). Therefore, it is an important element in verifying if a certain project should be financed by a PPP or not.

However, as aforementioned, transferring a risk from the public to the private partner has a price premium, thus, it affects the cost for the public partner. In this context, it is important to allocate risk in a cost effective way. In conclusion, the best balance is to allocate each risk to the partner who has better capacity, more knowledge and experience to deal with it. For example, risks that concern operational efficiency usually should be assigned to the private partner, and risks related to the pursuing of non-commercial objectives should be allocated to the public partner16 (European Commission, 2003; Bult-Spiering et Dewulf, 2006; OECD, 2007).

Moreover, risk-allocation is linked to renegotiations of PPP contracts and Financial Re-equilibrium Agreements (FRAs) (characteristics of these contracts that are explained in a further

16 “The objectives of risk transfer include:to reduce long term cost of a project by allocating risk to the party best able to manage it

in the most cost effective manner; to provide incentives to the contractor to deliver projects on time, to required standard and within the budget; to improve the quality of service and increase revenue through more efficient operations; and to provide a more consistent and predictable profile of expenditure” (European Commission, 2003).

8 section). The way that a risk is evaluated and therefore allocated has an impact regarding if there will be or not renegotiations (Cardoso, 2011). In fact, risk sharing is an important topic for this dissertation, since if the allocation is done correctly, it may reduce potential FRAs, and therefore avoid some extra costs for the State. Actually, when the public partner is selecting the best project during the tendering process, it should not choose based only on the financial costs. In fact, there are projects called optimistic/aggressive proposals. Initially, a project can present a lower cost, and thus win the tendering process. However, if risks are not well allocated, this can lead to FRAs, which consequently, will make the project more expensive for the public partner (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009; Cardoso, 2011). This was one of the NAO’s critics, since in Portugal, the main criteria to evaluate proposals is based on assessing the NPVs of State’s costs. As a consequence, some private entities present projects with lower costs, simply in order to make it to the next stage. It is argued that this is an example of lack of equality, competition17 and transparency (Tribunal de Contas, 2003; Assembleia da República, 2013).

Moreover, the risk-allocation in Portugal is considered to be inefficient, due to a weak identification and allocation of risks. In fact, this was the cause of the failure of some PPP contracts. This weakness had as a consequence several FRAs that increased the costs of the State (Tribunal de Contas, 2008). Curiously, the public partner guaranteed some exotic risks, such as compensations to the private partner if the corporate tax increases (Arroja, 2012). Furthermore, as already mentioned, the private partner may have more ability to face more risks. This may be due to the fact that, in a PPP contract, the private partner is usually comprised of more than one entity and each of them usually has different capacities and knowledge regarding different fields. This may contribute for the success of the PPP. However, this capacity of the private partner can have a negative impact. The private partner can use its knowledge and information to gain a privileged position (if the public sector does not protect itself), and act in a way that can be prejudicial for the public partner during the negotiation process. This reinforces the idea put forward in the previous section regarding the role of the State (Cardoso, 2011).

In Appendix 2, there is a list of risks and their explanations.

2.2.3. Transparency

As defined by the OECD, transparency is the “openness about policy intentions, formulation and implementation – is a key element of good governance”. This is correlated with better

17 It is important to have enough competition in order to have an effective risk-allocation. The OECD distinguishes two different

processes of competition:

Competition in the bidding process: This “improves the bargaining position of the government and prevents opportunistic (monopolistic) behaviour on the part of the private bidders. Thus, it helps a government to attain better VfM” (OECD, 2008). Therefore, if the number of competitors is limited, the PPP model should not be applied, since it can compromise the achievement of the best VfM (Burger et Hawkesworth, 2011).

Competition in the provision of the service: This is after the contract signing. It “ensures that the private partner delivers the agreed VfM because competition prevents moral hazard and limits the capacity of the private partner to force the government to renegotiate the terms of the contract. In the absence of competition, the government may, in effect, continue to carry the risk, even when has been transferred according to the PPP contract.” (OECD, 2008).

9 outcomes, economically and socially (OECD, 2002). In Portugal, there are some examples that illustrate that this aspect must be improved. For example, the NAO, the entity responsible for evaluating projects and that can decide on their impracticability, realized that some contracts were not fully disclosed. In 2009, the NAO refused to sign the prior approval regarding five projects, and one of the reasons was the financial conditions for the State. After the NAO received a new version of those contracts, which presented lower costs for the State, they were approved. Nevertheless, in May 2012, the NAO said that the planned contingent liabilities were not presented. In reality, the NPV of the costs in the new version of the contracts plus the cost with contingent liabilities is equal to the NPV of the cost in the initial version of the contracts. Thus, the financial responsibility for the State remained the same (Arroja, 2012; Ernst & Young, 2012; Assembleia da República, 2013). This situation is common in other countries too. Governments make agreements with private partners that have potentially high, yet hidden, costs (Schwartz, Corbacho et Funke, 2008). This is a problem that arises with contingent liabilities associated with the PPP model. This is a potential liability, which is only converted as an actual liability if a certain event occurs (OECD, 2002; PPIAF, 2012) (See more information about contingent liabilities in Appendix 3). Specifically, in this dissertation, it is relevant to write about budget transparency, if in the State Budget (“the single most important policy document of governments” (OECD, 2002)) all information regarding fiscal issues (all direct costs and contingent liabilities) is fully and systematically disclosed (OECD, 2002).

2.2.4. Accountability, Affordability and Budgeting

The accounting methodology regarding PPPs has, in recent years, been a theme of regular discussion both at a national and international level. “PPPs are not only challenging managerially but also give rise to problems of budget control and accountability. Budget formulation and accounting processes play critical roles in determining the impact that PPPs will in fact have on fiscal policy, resource allocation and public management” (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009).

There are different accounting methodologies, but some can create more incentives to apply the PPP model when a State wants to invest in public procurement. Actually, in some countries, the accounting has been one of the main reasons for choosing a PPP instead of a TIP, which has been creating false incentives. Usually, when choosing to invest through a PPP, the investment can be off budget. The assets and the debt incurred to buy the assets do not appear in the State’s books, only in the books of the involved private entities. In the TIP case, they are registered on the State’s books. In the TIP model, the government records expenditures (and debt, if it borrows) during the construction phase. In the PPP model, expenditures are usually only registered after the construction is complete and are spread out over several years. Thus, in the fiscal year when the asset is purchased, the expenditures of the public partner using the first

10 model are higher than when the second model is applied18. Therefore, a PPP may create the false impression that it is always a cheaper and more affordable model19. Governments can undertake a new project and do not report an increase on their expenditures. Initially, in the investment stage, undertaking a PPP project usually does not affect the deficit and the public debt. In this situation, governments are pushing expenditures to the future20. This can seem at a first glance more tempting for governments that pretend to invest, and even more, in countries that face deficit or debt problems (OECD, 2008; Schwartz, Corbacho et Funke, 2008; Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009; Burger et Hawkesworth, 2011; Funke, Irwin et Rial, 2013; Sarmento, 2013).

In this context, it is relevant to understand the concept of affordability. In fact, it is not linked to the off-balance sheet nature. It is only related to the intertemporal budget constraint of the government. This concept means that the expenditure of the government can be accommodated within the aforementioned constraint21. Thus, this is related to the concept of sustainability. Choosing between a TIP and a PPP should not depend on the accounting methodology, but on the affordability and VfM22. To conclude, using the PPP model may lead to greater affordability, only if it increases the VfM, and consequently, if the project fits the intertemporal budget constraint23. In fact, the question of affordability is not due to the off the books characteristic. However, the analysis of whether a project is affordable or not is sometimes neglected because of this characteristic of PPPs (OECD, 2008 and 2012; Funke, Irwin et Rial, 2013). Furthermore, it should be taken into account that, even if the country is investing in an effective project with VfM, this may crowd out other potential spending (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009).

At this stage, it is possible to identify two challenges regarding PPP. Firstly, policy-makers cannot think, fallaciously, that if a project is off budget it is more affordable. Secondly, to assess affordability, they have to budget for a longer-time horizon. Actually, this does not always happen, governments usually only budget for the upcoming year. However, this is not always an easy task. In fact, usually there is uncertainty regarding costs and contingencies. Costs are

18 See more information regarding expenditures and revenues in each model in the Appendix 1.

19 It is a false impression, because the future payment commitments from the government to the private partner may be forgotten. 20 In the short run, a PPP always reduces the government capital expenditure. However, analysing the present value, this may not be

a cheaper option. This depends on the interest expenditure (“the interest rate paid by the private sector usually exceeds that of the public sector”) and on the efficiency (OECD, 2008). “In the absence of efficiency gains, PPPs and publicly financed projects have a similar long-run effect on public finances” (Funke, Irwin et Rial, 2013). Moreover, transferring mandatory costs to the future, it reduces the capacity of governments to “use spending cuts or shifts as instruments of countercyclical economic policy” (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009).

21 “The future revenue stream of the government equals or exceeds the present value of the sum of expected future interest payments

and the present value of the government’s expected non-interest expenditure” (OECD, 2008).

22They are the two “benchmarks for PPP viability” (OECD, 2008).

23 “If the use of a PPP instead of public financing does not change the net present value of the government’s cash flows, the PPP

does not make investment more affordable. If the government cannot afford to finance the project using traditional public finance, it probably cannot afford to undertake it as a PPP. Conversely, if the government can afford to undertake the project as a PPP, it can probably also afford to finance it traditionally” (Funke, Irwin et Rial, 2013).

11 uncertain and difficult to predict, even direct fiscal commitments24, because they are long term and sometimes depend on variables for which predictions change over time (example: demand and exchange rate25). Moreover, there are other commitments, like contingent liabilities, which are difficult to quantify. This increases the difficulty concerning the assessment of affordability (OECD, 2008; Duarte, 2011; PPIAF, 2012). However, there are some recommendations that governments should follow to eliminate false incentives. They should provide more information regarding the future burden with PPPs. This information should include not only existing contracts but also planned contracts. Then, these predictions should be integrated in long-term fiscal projections. In fact, the budgeting can be reformulated to reduce the bias. For instance, the treatment of PPPs on budgets can be equal to the treatment of publicly financed projects, requiring the same type of approval and planning. Other example is the two-stage budgeting process. Firstly, all projects must be approved, assuming that they are publicly financed, and only thereafter, the method of financing is decided (Funke, Irwin et Rial, 2013).

The question of affordability is a constraint regarding public investment. In addition to this, some countries face other constraint: fiscal rules26.This may also create incentives in favour of PPPs. Governments may only be able to pursue the objective of investing on a certain project by using a PPP27. As previously said, this is decided based on the off the books PPPs’ characteristic, instead of assessing if the project represents better VfM.

Moreover, as initially mentioned, different accounting methodologies applied in national budgets regarding PPPs may have different impacts on the bias in their favour. In the majority of countries cash accounting is applied, while in others accrual accounting or a mix of the two28. These methods record expenditures and revenues differently. The cash-based method records them when cash is exchanged (when it is received or paid out). Contrarily, the accrual-based method records when they are incurred, when there is a decision, independently of the moment of payment. In the first method, a government would have less incentive for capital spending, because it would have to record it up front (during the design and construction phases). In the accrual regime, it is paid over time. Thus, this “can smooth out capital funding and overcome the spikes associated with cash-based budgets” (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009). Countries with cash-based regimes that wish to intensify public infrastructures have few options to do so, such as, raise taxes, levy user fees, cut spending in other areas, etc. However, these are painful options. Therefore, a PPP seems to be the way to achieve their objective and, at the same time,

24 Direct commitments: upfront payments and ongoing payments (example: shadow tolls and availability payments) (PPIAF, 2012).

See more information in Appendix 3.

25 When payments are made in a foreign currency.

26 “Budgetary limits imposed either legally or as political commitments” (OECD, 2008). For example, Portugal is under the Stability

Growth Pact, which requires countries not to have deficits above 3% of GDP (OECD, 2008).

27 Actually, “fiscal pressures were a prime consideration for using PPPs in some of the eight countries studied. Budget officials in

Hungary, for instance, said that bringing the deficit under the 3% target has been critical since its entry into the EU in 2003. When compared to traditional government capital investment, PPPs are a strategy to undertake capital projects with minimal impact on the deficit” (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009).

28 “Accruals and cash are often portrayed as opposing end-points on a spectrum of possible bases for accounting and budgeting”

12 to overcome the spiking problem, since it does not encumber budgets in the short-run. This also explains the increased preference for this model (OECD, 2008; Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009). Adding to the aforementioned information that governments should disclose, they should also apply the accrual method. This is “more challenging, but potentially more influential” in reducing the bias in favour of PPPs. In addition to this, the most important indicators of the debt and deficit, such as indicators that are applied to set fiscal rules, should change (Funke, Irwin et Rial, 2013)29.

Portugal has been improving the way to deal with PPPs (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009). The National Budget has appended a memo with predicted net costs for each sector in a long-run perspective. This is considered an excellent example of transparency (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009; Moreno, 2010; OECD, 2013). However, there are still some flaws. Firstly, they usually include neither costs regarding projects to be launched nor additional burdens related to potential FRAs. Secondly, in the SBs there is no information about the accounting methodology. Thirdly, the costs with each specific project are not known. These were some of the ingredients that led to sustainability problems; it is a burden that both the present and future generations have to pay with painful sacrifices (Moreno, 2010). Moreover, the main problem was that the State wanted to invest in infrastructures without30 initially using its own31 money to face the high prices of this type of investments. Thus, the State took advantage of the accounting system (Moreno, 2010; Arroja, 2012). PPPs were the way to invest even in periods with strict budget constraints and external fiscal rules. They were associated to a budgetary relief regarding the initial investment (Schwartz, Corbacho et Funke, 2008; Arroja, 2012). This problem is linked to the lack of fiscal clarity related to PPPs. If there are no rules to address and manage the fiscal consequences of PPPs, they “can be used to bypass budget or borrowing limits” (PPIAF, 2012). In Portugal, this example of financial engineering apparently brought benefits to some economic agents. The State managed to provide goods and services without increasing the public debt. Therefore, governments increased their probability of winning the following elections. On the other hand, private partners made good businesses, with almost no risks and high profitability. Moreover, it was also fruitful for the banks that financed these projects. However, these contracts did not bring many advantages for the tax payers, actually, the costs are mainly covered by taxes that are launched annually in the SB (Moreno, 2010; Arroja, 2012).

In this context, and as conclusion, the OECD recommends that these projects “should not be used as a vehicle for escaping budgetary discipline by hiving financial commitments off public sector balance sheets” (OECD, 2007). All projects should be included in the State Budget,

29 This “requires ensuring that these treat investment in PPPs as public investment that creates both public assets and public

liabilities” (Funke, Irwin et Rial, 2013).

30 Or with low commitments

13 except if all risks are transferred to the private partner. Actually, “guarantees (implicit or explicit) need to be accounted for and should be subject to a similar degree of scrutiny during public budget processes as other spending”, in order for the public sector not to forget their potentially high fiscal implications (OECD, 2007).

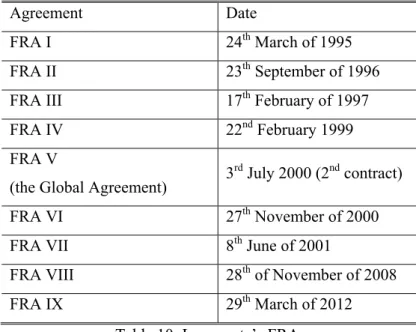

2.2.5. Renegotiations and FRAs

A renegotiation is the consequence of a process between the two involved entities, which is related to changes in the base-case32. This occurs when initial assumptions of the contract are revised. FRAs are requested when one of the partners does not comply with the contract. It is usually written in the contracts in which scenarios they can be requested (Cardoso, 2011; Sarmento, 2013)33.

Theoretically, a renegotiation brings advantages for this type of contracts. They are long-term contracts (the average, in Portugal, is 30 years), so it is difficult to design complete contracts with all details. Contrarily, short-term contracts can be easily reviewed and modified. Therefore, renegotiations in PPP contracts may become occasionally inevitable (OECD, 2007; Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009; Cardoso, 2011)34. Circumstances change during the contractual period, so the contract should accommodate these alterations. In fact, “no contract is flexible enough to cover every eventuality” (OECD, 2007). Moreover, an excessively detailed contract may encourage partners to “look for loopholes” instead of making this relation work. Therefore, there should be a balance between flexibility and strictness. A certain degree of strictness is a source of confidence for all entities involved in the project. This balance is related to risk-allocation, since with rigid contracts, more risks are allocated to the public partner. And, with flexible contracts, more risks are allocated to the private partner, but the price premium may be higher (OECD, 2007; Schwartz, Corbacho et Funke, 2008; Burger et Hawkesworth, 2011).

According to the OECD, the best option is to “include contractual stipulations specifying under what circumstances revisions to the original agreement shall be considered. Permanent and active review panels, dispute committees and arbitrational instances should be established as part of the contractual structure and operated to strengthen the parties’ relationships” (OECD, 2007).

In Portugal, each contract specifies when a FRA may be requested. Some examples of those specifications are: when there is an unilateral imposition by the public partner, in other words when it changes what was initially defined, and this implies an increase in costs or a decrease in revenues for the private partner. Other examples are when there is a case of force majeure or a modification in a specific law (Cardoso, 2011). A FRA is usually established by using as

32 The base-case is the principal instrument of reference for the partners, which has all the economic-financial assumptions and

projections (Cardoso, 2011).

33 The Appendix 4 presents the process of renegotiation in Portugal.

34 “Principle 18: Occasional renegotiations are inevitable in long-term partnerships, but they should be conducted in good faith, in a

14 reference the base-case, and it has the objective of achieving the minimum values of some financial ratios35. To accomplish this objective, the public partner, for example, may have to pay a direct compensation, and/or change the deadline of the contract and/or change its financial obligations (Cardoso, 2011). On the other hand, the public partner may want to renegotiate a contract, for example, to deal with changes in technology or fiscal constraints. However, sometimes this cannot happen, because the private partner has to approve it (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009).

As aforementioned, there are potential advantages regarding renegotiations of PPP contracts. However, there are some examples of problematic situations. In Portugal, some projects were renegotiated several times, and in most cases, this significantly increased the costs for the State36. Another example lies on the conclusions of Chilean officials, in which payments ended up being 35% higher than what was initially decided due to renegotiations. Therefore, they became an extra problem linked to PPP contracts for the public partner, bringing only partial benefits, in other words, only benefiting private partners (Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009; Cardoso, 2011; Arroja, 2012). This is the result of some of the aforementioned challenges, such as asymmetry of information, better negotiation skills of private partners and optimistic proposals during the tendering process (Tribunal de Contas, 2008; Posner, Ryu et Tkachenko, 2009; Cardoso, 2011).

According to Ernst & Young, the burden of the State should consider not only the costs regarding regular activity, but also the processes of FRAs that are contractually defined, and which could be the reason for a cost increase and a source of uncertainty (Ernst & Young, 2012).

2.3. PPPs in Portugal

In this dissertation, the case study is the situation in Portugal. Before analysing the predicted costs for the Portuguese State, an overview of the PPP projects is presented.

Since the 90´s, several countries have been increasingly applying the PPP model (OECD, 2008; Burger et Hawkesworth, 2011)37. Portugal is not an exception and since 1992 it has been developing projects by PPPs. The first project was the Vasco da Gama bridge. Since then, Portugal has become one of the leaders in Europe (Moreno, 2010)38. Nowadays, there are PPPs in several sectors, such as road, railway, health and security39.The road sector is the one with

35 Source: Decree-Law n. 141/2006, Article 14th- C

Examples: Internal rate of return to shareholders (IRR) and Debt-Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR) (Cardoso, 2011).

36 According to Abrantes de Sousa (2011), there were very good contracts at the beginning, but, over the years, they have become

unrecognizable (cited by Arroja 2012). Moreover, according to Moreno, since 1992 in Portugal, it is not easy to identify a contract that was not renegotiated, and consequently, without higher costs for the public partner (Moreno, 2010).

37 See the History of PPPs in Appendix 5.

38 “With a ratio of between 1.2% and 1.3% of GDP, Portugal has the highest PPP-to-GDP ratio in Europe (nearly double the United

Kingdom ratio of between 0.6% and 0.7%)” (OECD, 2008).

39 These are the areas that the respective costs for the State are presented in SBs. Others public concessions, such as of the

15 more projects and with a higher burden for the State. It represents 80% of future costs (Bult-Spiering et Dewulf, 2006; Arroja, 2012). This is the reason why it is analysed the road sector in this dissertation. Furthermore, the most used type of PPP is the concession contract (see more information in Appendix 6), in which the private partner is responsible for the conception, the financing, the construction, the maintenance, and the operation of infrastructures. In the following section, the financial linkages between the two partners are presented. In order to understand some of what will be said, it is worthwhile to mention that, in Portugal, it is also considered a PPP when the equivalent to a private partner is a public company, a cooperative, or a non-profit private institution. One example is Estradas de Portugal, S.A. (EP). Although the EP’s concessions are not directly held by the State, the SBs include the costs supported by the concession EP. (See more information about the EP in Appendix 7).

2.3.1. Financing of projects and Costs for the State

This type of model is characterized by the way of financing. Private partners are responsible for part or total financing of projects. They have to mobilize the necessary financial resources in order to invest and operate the assets of the partnership, so there is a bigger financial effort by the private partner during the construction stage. The financing typically has two components, one is equity and another is debt capital. It may use bank financing and/or take advantage of EU funds40. This is usually compensated by payments along the contract’s period from the public to the private partner. In several projects, the payments during the lifespan of the projects are contractually defined (OECD, 2008; DGTF, 2009; Cardoso, 2011; Ernst & Young, 2012). However, the cost and the revenue for each partner can be different, depending on each contract. The private partner, typically, has two sources of revenue to overcome the cost of the investment on the infrastructure: the aforementioned payments/subsidies from the public sector (if these are the main source, it is called government-funded PPP) and fees paid by the users, like tolls in the road sector (if these are the main source, it is called user-funded PPP). Generally, from the public to the private partner, there are two types of fiscal commitments: direct liabilities and contingent liabilities (OECD, 2008; PPIAF, 2012; Funke, Irwin et Rial, 2013).

In this dissertation, the focus is on expenditures of the State with PPPs in the road sector. In this way, in the following section, there is a description of the normal costs for the Portuguese State with this sector. In Appendix 8, there is information regarding other sectors.

2.3.2. Road Sector

The type of concessions varies according to two factors, namely Ownership and Payments (Cardoso, 2011). Regarding this last factor, in Portugal, there are the two aforementioned

40 In fact, “privately financed projects are mainly carried through in the roads sector because of EU subsidies and credits with low

16 scenarios: payments from the public sector and from users to the private partner. About the ownership of the assets, usually, after the contract’s period, the public partner is the owner of the asset. Therefore, the residual value risk is allocated to the public partner (OECD, 2008). The type of contracts in this sector is generally Design-Build-Finance-Operate-Transfer (DBFOT) (Cardoso, 2011). Globally, nowadays, twenty-three contracts are included in the SB. Concerning the payments from the public sector, there are mainly payments for availability, for traffic service and for the service of tolls’ collection. Thus, the contracts can be divided into three different groups, according to the delivered service and payments to private partners (Ernst & Young, 2012; DGTF, 2012):

1) Traditional concession with real tolls:

These are concessions of the State, and the real tolls are for the concessionaires. In other words, the private partner receives payments directly from the users (the tolls), which is their main source of revenue, and does not receive ongoing payments from the State. Therefore, these concessions, usually, have neither regular costs nor regular revenues for the public partner. There are five examples of this, which are Brisa, Oeste, Lusoponte, Douro Litoral and Litoral Centro.

2) Concessions with model of availability:

In this type of model, the EP retains the tolls, and in exchange it has to pay the concessionaries for the availability. This is a fixed payment that is paid on a regular basis, independently of the demand, but that can be reduced in case of unavailability (e.g. accidents and construction). This means that this payment only changes if the quality of the infrastructure is not what was defined in the contract41.

In this case, the demand risk is allocated to the public side (the revenues of the EP depend on the traffic). However, there are some advantages. An example of these is the protection of the public interest, since it gives financial incentives to concessionaires to deliver the service and have the infrastructure within negotiated standards. Other example is that the cost for the public partner is not uncertain; in fact, they “will never exceed the maximum availability payment” (Dochia et Parker, 2009; Ernst & Young, 2012).

41 A few remarks on the model of availability:

Definition of availability in the Portuguese Law:

“a disponibilidade das vias consiste na aferição da qualidade do serviço prestado aos utentes e a aferição dos níveis de

sinistralidade e dos níveis de externalidades por elas geradas” Source: Decree-Law n. 110/ 2009 18th of May.

It can be divided into two categories (Ernst & Young, 2012):

“Pure availability”- the infrastructure or part of it has to be available for the purpose that was built, without any obstruction.

“Constructive availability”- in addition to the availability of the infrastructure, it is required a certain level of security, quality and performance.

17 Some examples are Grande Lisboa, Norte42 and the seven ex-SCUTs: Grande Porto, Norte Litoral, Costa de Prata, Beira Litoral e Alta, Interior Norte, Beira Interior and Algarve.

Previously, SCUTs were concessions with shadow tolls, in which the revenues of the private partner, called rents, were totally paid by the State (Cardoso, 2011). The direct payments from the State to private partners were a function of the traffic level. In this case, the user-payer system was substituted by the tax-payer system. In other words, it was the State who paid the tolls instead of the user of the roads (Bult-Spiering et Dewulf, 2006; Moreno, 2010; Ernst & Young, 2012; Estradas de Portugal, 2012). (See in the Appendix 9 the contract of Costa de Prata after the renegotiation)

3) With model of availability payments and payments for the service:

The EP receives tolls as revenues, and is has to do two kinds of payments to the private partner. It pays for the availability (this is the fixed counterpart for the availability of the infrastructure) and for the service, which is related to the traffic. So, these contracts have a fixed and a variable part (according to the traffic level). There are eight examples: the Túnel do Marão and the sub concessions Pinhal Interior, Litoral Oeste, Douro Interior, Baixo Tejo, Baixo Alentejo, Transmontana and Algarve Litoral (DGTF, 2012; Ernst & Young, 2012; Estradas de Portugal, 2012). (See in the Appendix 10 the contract of Transmontana)

18

3.

Methodology and Data Collection

3.1. Data Collection

The aim of this dissertation is to analyse the predictions presented in ten different State Budgets regarding how much the State will spend with PPP in the road sector during the period 2014-2031. In fact, different State Budgets present different predictions for the same period. These differences are also identified by Moreno (2010). He mentioned that in SB 2009, the NPV of the predicted net costs for the road sector was around 12 000 M€, whereas, in 2010, it was around 5 000 M€. Without explanation there is this huge difference, which he called a blackout (Moreno, 2010).Therefore, my objective is to understand the reason for those differences. As a note, this analysis focuses only in gross costs. The gross costs for the State in this sector include contracted remunerations, investment’s compensations and accepted Financial Re-equilibrium Agreements (FRAs) (UTAP, 2013).

Since the State Budget only presents the total predicted costs for the road sector, the Estradas de Portugal provided me the costs per project in order to be able to do this analysis. Thus, the data base is the predicted gross costs per project (24 PPP projects in the road sector) for the period 2014-2031 presented in ten different State Budgets (from SB 200543 to SB 2014).

For each project and for each SB I computed the Present Value (PV) of the predicted costs, corresponding to the sum of cash flows of the period 2014-2031. Thus, the difference of PVs will not be explained by the number of years. Nevertheless, I had to be cautious since the values were not immediately comparable. In some SBs, the values included the VAT, and some present the values at current prices and others at constant prices.

Therefore, firstly, in the SBs that included the VAT, I divided the values by the VAT, in order to have all predicted costs without VAT. The following rates were used (for SBs where the rate was not given, but it is said that the VAT is included, I applied the VAT of the end of the correspondent year):

43 First SB that presents costs with PPPs.

19

SB VAT Source/ Information

2005 19% Given by EP

2006 21% Given by EP

2007 21% Given by EP

2008 21% Direcção-Geral dos Impostos, 2011

2009 20% Given by EP

2010 - Prices without VAT

2011 - Prices without VAT

2012 23% PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2012

2013 23% PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2013

2014 23% SB 2014

Table 1: VAT

Secondly, I computed the PV, but I had to take into account that some SBs presented the costs at current prices and others at constant prices. Therefore, for SB at constant prices I discounted the values at the rate of 4%, and for SBs at current prices I discounted at 6,08%. The rate 6,08% is the official discount rate of the State. It is composed by a real discount rate that is fixed in 4% and by a discount rate of the annual inflation, which was administratively fixed by the Despacho nº 13208/2003 in 2% (Ernst & Young, 2012). In this way, I obtained the PV for each SB with base-year the year of the corresponding SB. For example, I obtained for the SB 2006 the PV of the predicted costs with base-year 2006, whereas for the SB 2014, the PV with base-year 2014. Therefore, then, I converted all for the same base-year (2005). In order to do this, I used the real Consumer Price Index (CPI) (Source: INE, 2014). Since there is not the real CPI for 2014, I applied the predicted CPI growth rate presented in the SB 2014.

Thirdly, I built the graphs presented in the Appendix 12 and the following graph:

X-axis: SBs

Y-axis: PV of predicted costs for the State (M€)

20 Analysing all the graphs, I could identify the differences from one SB to another. After this identification, I analysed possible explanations for those differences. To assess this, I analysed each PPP in the road sector (24 projects) and each State Budget (10 SBs, from the SB 2005 to 2014). In this way I recognized the main events regarding PPPs in the road sector. Then, I computed an econometric model based on panel data, which is described immediately.

3.2. Econometric Analysis

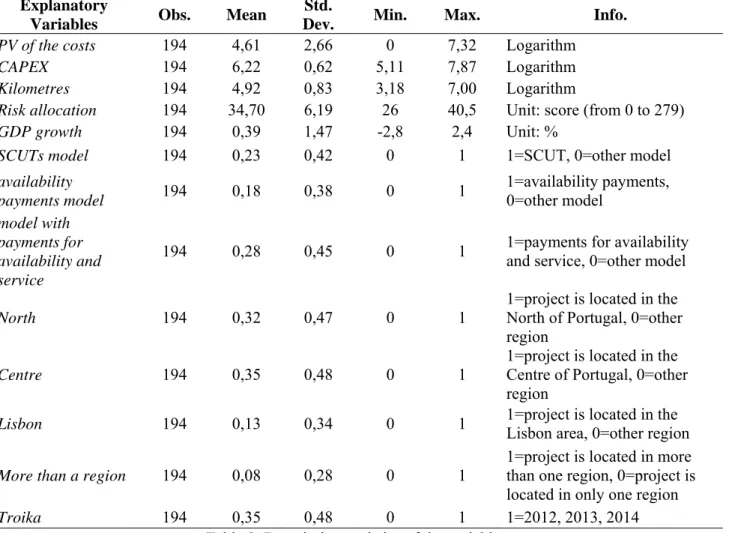

The analysis is based on a panel data model. The database consists of information on the several PPP projects since 2005 until 2014, retrieved from the annual SBs. The model has as dependent variable the logarithm of the PV of the predicted costs with regards to each project in each SB. The main objective of this analysis is to identify the factors that affect the predicted costs.

3.2.1. Independent variables

Characteristics of concessions: CAPEX and Kilometres

Since I have panel data and I aim to understand the differences of the predictions over SBs, I have to take into account that projects are different. Hence, I include in the model these control variables, which may explain the differences from one project to another.

Actually, large scale projects, which can be translated as projects with higher CAPEX and more kilometres, represent projects that may have a higher burden for the State. CAPEX refers to the initial investment, which is one of the responsibilities of the private partners. These variables would explain why some projects have low costs and others have high costs. For instance, the concession Beiras Litoral e Alta, over the SBs, has PVs of the predicted costs around 902 M€. This contrasts with a smaller scale project as the concession Algarve, which presents values around 395 M€. The source of information was Cardoso (2011).

Characteristics of concessions: Risk allocation

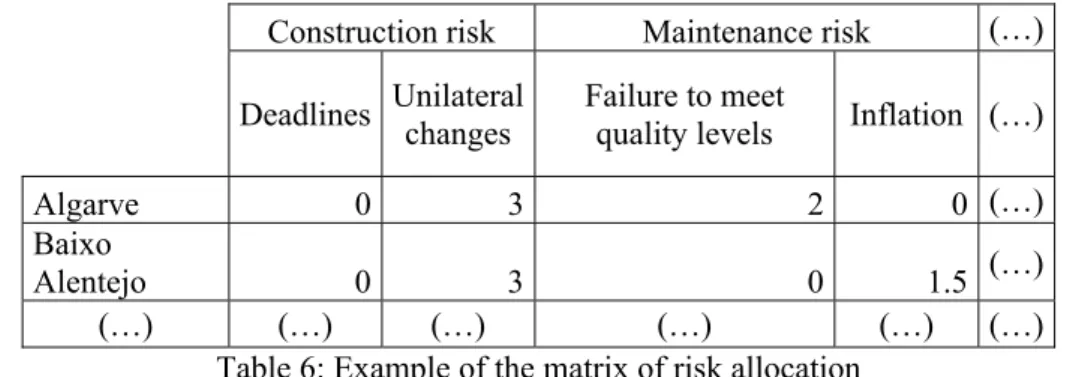

As explained earlier, in the Literature Review, risk allocation is an important feature of a PPP project and it can affect the cost for the State. In fact, costs related to FRAs are the outcome of the systems of risk sharing foreseen in the contracts (Assembleia da República, 2013). This variable is based on the matrix of risks for each project presented in the report of the Direcção Geral do Tesouro e das Finanças (DGTF, 2012). This report identifies several risks for each project. Regarding each risk, the report identifies if for a specific project that risk is shared, is allocated on the public or on the private partner. For example:

21 Construction risk Maintenance risk (…)

Deadlines Unilateral changes

Failure to meet

quality levels Inflation (…)

Algarve private public Public private (…)

Baixo

Alentejo private public Private shared (…)

(…) (…) (…) (…) (…) (…)

Table 2: Example of the matrix of risk allocation

I defined some criteria in order to create a variable that represents the information provided in this report. For each project, if a certain risk is allocated to the public sector, I attributed the number one. If the risk is shared, I attributed 0,5, otherwise it is zero.

Construction risk Maintenance risk (…)

Deadlines Unilateral changes Failure to meet quality levels Inflation (…)

Algarve 0 1 1 0 (…)

Baixo

Alentejo 0 1 0 0.5 (…)

(…) (…) (…) (…) (…) (…)

Table 3: Example of the matrix of risk allocation

In addition to this, I took into account the level of the risk, in other words, the probability of a certain risk to occur and its impact. In fact, for each risk, the report says if the probability of occurrence is high, medium or low, and it says if the risk would have a strong, medium or reduced impact. For each category I attributed a score:

Probability: Score

High 3 Medium 2 Low 1 Table 4: Probability of Risk Occurrence

Table 5: Impact of the Risk

Impact: Score Strong 3 Medium 2 Reduced 1