www.elsevier.pt/ge

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Compliance

with

ESPGHAN

position

on

complementary

feeding

in

a

multicultural

European

community.

Does

ethnicity

matter?

Sara

Nóbrega

a,∗,

Mariana

Andrade

b,

Bruno

Heleno

c,

Marta

Alves

d,

Ana

Papoila

d,

Leonor

Sassetti

a,

Daniel

Virella

a,daDepartmentofPediatrics,HospitaldeDonaEstefânia,CentroHospitalardeLisboaCentral,EPE,Lisboa,Portugal bDepartmentofPediatrics,HospitaldasCaldasdaRainha,CentroHospitalardoOesteNorte,CaldasdaRainha,Portugal cFamilyMedicineDepartment,FaculdadedeCiênciasMédicasdaUniversidadeNovaLisboa,Lisboa,Portugal

dEpidemiologyandStatisticsOfficeoftheResearchUnit,CentroHospitalardeLisboaCentral,Lisboa,Portugal

Received13June2014;accepted13August2014 Availableonline19November2014

KEYWORDS Infantfeeding; Weaning; Inadequacies; Culture; EuropeanSocietyof Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatologyand Nutrition Abstract

Introduction:In2008,ESPGHANpublishedapositionpaperoncomplementaryfeedingproviding recommendationstohealthcareprofessionals.Culturalandsocio-economicfactorsmightaffect thecompliancetotheseorientations.

Aim: Toestimate theprevalenceofinadequacies duringcomplementaryfeeding(ESPGHAN, 2008)anditsassociationwithdifferentethnicbackgrounds.

Methods:Cross-sectional surveyofaconveniencesample ofcaretakersofchildrenupto24 months ofageinasingle communityhealth centreinGreaterLisbon, throughavolunteer, self-appliedquestionnaire.

Results:Fromasampleofchildrenwithwideculturaldiversity,161validquestionnaireswere obtained(medianchild’sage9months,medianmother’sage32years).Theprevalencerateof atleastonecomplementaryfeedinginadequacywas46%(95%CI:38.45---53.66).Thecommonest inadequacieswere:avoidinglumpysolid foodsafter10monthsofage(66.7%), avoidanceor delayedintroductionoffoodsbeyond12months(35.4%),introductionofglutenbeyond7months (15.9%)orsaltbefore12months(6.7%).Foreachincreaseof1monthintheageofthechild, theoddsofinadequaciesraised36.7%(OR=1.37;95%CI:1.20---1.56;p<0.001).Theoddsfor inadequaciesinchildrenofAfricanorBrazilianoffspringwasthreetimeshigherthatof Por-tugueseancestry(OR=3.31;95%CI:0.87---12.61;p=0.079).Theinfluenceofgrandparentswas relatedtoanincreaseintheoddsofinadequacies(OR=3.69;95%CI:0.96---14.18;p=0.058).

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:sara.anobrega@chlc.min-saude.pt(S.Nóbrega).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpge.2014.08.004

Conclusion:Inadequaciesduringcomplementaryfeedingarefrequentandmaybeinfluenced bytheculturalbackground.

©2014SociedadePortuguesadeGastrenterologia.PublishedbyElsevierEspaña,S.L.U.Allrights reserved.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Alimentac¸ãoinfantil; Diversificac¸ão alimentar; Inadequac¸ões; Cultura; SociedadeEuropeia de Gastrenterologia-Hepatologiae Nutric¸ãoPediátrica

Adequac¸ãodadiversificac¸ãoalimentaràsrecomendac¸õesdaESPGHANnuma comunidadeeuropeiamulticultural.Aetniatemimportância?

Resumo

Introduc¸ão:Em2008aESPGHANpublicourecomendac¸õessobrediversificac¸ãoalimentarpara osprofissionais desaúde. Fatores socioeconómicoseculturais podem,no entanto,afetaro cumprimentodestasorientac¸ões.

Objectivos:Pretendemosestimaraprevalênciadeinadequac¸õesàsorientac¸õespublicadase exploraraassociac¸ãoentreinadequac¸õeseasdiferentesinfluênciasculturais.

Métodos: Estudo transversal, baseado num questionário voluntário de autopreenchimento, fornecidoaumaamostradeconveniência depaisdecrianc¸asatéaos2anosdeidade,que frequentavaumCentrodeSaúdedaGrandeLisboa.

Resultados: Obtivemos161questionáriosválidosdeumaamostradecrianc¸ascomampla diver-sidadecultural (idademediana das crianc¸as 9meses, idade mediana dasmães 32 anos). A taxa de prevalência de pelo menos uma inadequac¸ão foi de 46% (IC95%: 38,45-53,66).As inadequac¸õesmaisfrequentesforam:evicc¸ãodealimentosgrumososoumenostrituradosapós os10mesesdeidade(66,7%),evicc¸ãoouatrasonaintroduc¸ãodealimentosapósos12meses (35,4%),introduc¸ãodeglútenapósos7meses(15,9%)ouintroduc¸ãodesalantesdos12meses (6,7%).Por cadaaumentodeummêsnaidadedacrianc¸aoriscodeinadequac¸ãoaumentou 36,7% (OR=1,37;IC95%: 1,20-1,56;p<0,001). Paraalém disso, o riscode inadequac¸ão para descendentesdefamíliasafricanasoubrasileirasfoi3vezessuperioraodosdescendentesde portugueses(OR=3,31;IC95%:0,87-12,61;p=0,079).Ainfluênciadosavósaumentouoriscode inadequac¸ões(OR=3,69;IC95%:0,96-14,18;p=0,058).

Conclusões:Nesteestudofoiencontradaumaelevadaprevalênciadeinadequac¸õesdurantea diversificac¸ãoalimentareestefactopoderáserinfluenciadoporcaracterísticasculturais. ©2014SociedadePortuguesadeGastrenterologia.PublicadoporElsevierEspaña,S.L.U.Todos osdireitosreservados.

1.

Introduction

Complementary feeding (CF) is defined as the introduc-tion of solid foods and liquids other than breast milk, infantformulaor follow-onformulaintoaninfant’s diet.1 Timely introduction of appropriate complementary foods is essential for adequate nutritional supply and devel-opment of children.1,2 In 2008, the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) published a position paper on CF providing recommendations for health care providers.1 However, different cultural and socio-economic factors (e.g., low-income of the family, mother’s age and education) can interferewiththe compliancetosomeof the health-care provider’s recommendations.2---4 Fear of food allergy may alsoinfluence parents and caregivers during the weaning process.5

The primary aimof this exploratory study wasto esti-matetheprevalence ofinadequacies duringCF,according totheESPGHANposition.1Itwasfurtheraimedtoidentify inadequacies in families withdifferent cultural or ethnic backgrounds.Wetested thehypotheses thatinadequacies

are frequent and that caretakers withself-reported non-Portuguese cultural background have more inadequacies accordingtotheESPGHANrecommendations.

2.

Materials

and

methods

2.1. Studydesign

Across-sectionalexploratorysurveyonaconvenience sam-ple of caretakers of children up to 24 months of age, attendingwell-childvisits, wasconductedatasingle pub-licHealthPrimaryCareCentreinGreaterLisbon,Portugal, betweenSeptemberandDecember2010.

2.2. Localcontext

The Primary Care Centre where the study was under-taken served a multicultural community, with 7% being immigrantpeople.Childrenwereattendedbyfamily physi-cians andpaediatric specialist nurses. Most of the family physicians received paediatric formation, includingabout

the weaning process, as part of a continuous education programme or during their residency. Because there was a paediatrician until 2008 in this Centre, older family physicians may have been less aware of more recent recommendations.

2.3. Datacollection

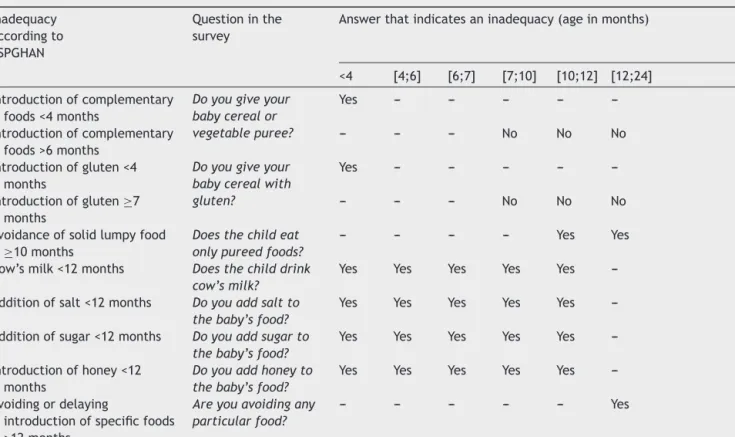

A self-applied questionnaire to collect information about current feeding practices, based in the complementary feedingmilestones,wasdesigned(Annex1).This informa-tion,togetherwiththeageofthechild,wasusedtoassess the presence of inadequacies (main endpoint) (Table 1). Inadequacies were defined as unconformities in relation to publishedESPGHAN recommendations.1 Information on self-reported cultural background, assumed as a possible explanatoryvariable,wasalsocollected.Furthermore,we inquiredaboutpotentialconfounderssuchassocial charac-teristics(mother’sage,yearsofschool,workingstatusand self-reported economic difficultiesin buying food),family features(maincaretaker,numberofsiblings),placewhere thechildspentmostofthedayandplacewherefoodwas prepared(at nursery, home or by the nanny).Face valid-ityofthequestionnaire wasagreed byanexpert panelof paediatriciansandfamilyphysicians;thequestionnairewas testedon-sitewithasmallconveniencesampleofparents. The study wasapproved by the involved institutions, fol-lowing current procedures. An oral informed consentwas obtainedfromeachparticipant.

The parents or caretakers of children attending the well-childclinic were invited to fill in the questionnaire, whichwasavailablein thewaiting roomofthePaediatric Health Department. A single questionnaire was applied, regardlessofthechild’sageorself-reportedcultural back-ground.Questionnairesweremostlyself-reported,although caretakers whocould not read Portuguese properlycould asktohave itreadandfilledinbyoneofthe researchers (SN, MAn), who were paediatric residents, temporarily working in this setting. To reduce social-acceptability bias,anonymityofthequestionnaireswaspursuedandno personalidentificationdatawasasked.Questionnaireswere availableinthewaitingroomand,afterfilledin,theywere returnedinto a sealed box in the same room. To reduce recall bias,we have only enquired about current feeding practices,notaboutpastones.Additionally,questionswere formulatedtoavoidinducingresponses(e.g.,‘‘Doyoufeed him/hercerealsorsoup?’’or‘‘Doyouaddsugartohis/her food?’’).Thehealthprofessionalsinvolvedinprovidingcare wereunawareofthecaretaker’sparticipationinthestudy. Datafrom self-reported cultural background and possible confounders were extracted directly from the question-naires. However, each of the 10 individual inadequacies wasdefinedconsideringboththeanswergivenandtheage ofthechildatthetimeofthesurvey.Forinstance, ‘‘late complementary feeding’’ was defined as children aged over 6 monthsreported asnot having introduced CF yet. Similarly, ‘‘early introduction of cow’s milk’’wasdefined aschildrenyoungerthan12monthsalreadydrinkingcow’s milk.Sinceasinglechildcouldhavemultipleinadequacies,

Table1 Summaryofexpectedinadequaciesincomplementaryfeeding,accordingtothe2008ESPGHANrecommendations(1).

Inadequacy accordingto ESPGHAN

Questioninthe survey

Answerthatindicatesaninadequacy(ageinmonths)

<4 [4;6] [6;7] [7;10] [10;12] [12;24] Introductionofcomplementary

foods<4months

Doyougiveyour babycerealor vegetablepuree? Yes --- --- --- --- ---Introductionofcomplementary foods>6months --- --- --- No No No Introductionofgluten<4 months

Doyougiveyour babycerealwith gluten?

Yes --- --- --- --- ---Introductionofgluten≥7

months

--- --- --- No No No Avoidanceofsolidlumpyfood

≥10months

Doesthechildeat onlypureedfoods?

--- --- --- --- Yes Yes Cow’smilk<12months Doesthechilddrink

cow’smilk?

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes ---Additionofsalt<12months Doyouaddsaltto

thebaby’sfood?

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes ---Additionofsugar<12months Doyouaddsugarto

thebaby’sfood?

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes ---Introductionofhoney<12

months

Doyouaddhoneyto thebaby’sfood?

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes ---Avoidingordelaying

introductionofspecificfoods >12months

Areyouavoidingany particularfood?

the number of children with at least one of the possible inadequacies for each age group was calculated. Finally, self-reported cultural background was reclassified into categories (Portuguese/Brazilian/African/other). Miss-ing data on outcomes were managed by excluding the cases.

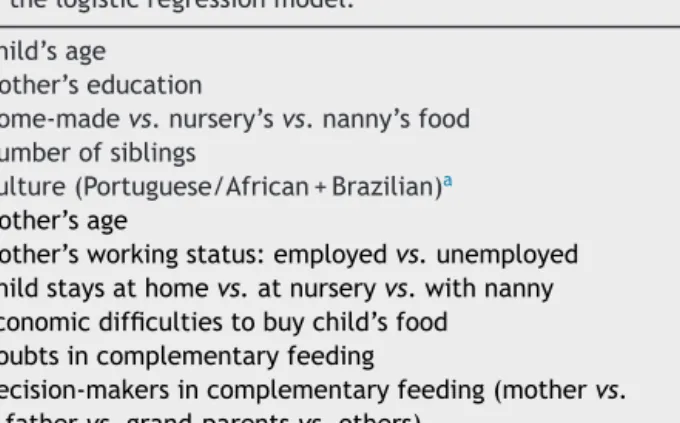

2.4. Statisticalanalysis

Beingan exploratory study, nocalculation of sample size wasmade.Prevalencerateswerecalculatedwith95% confi-denceinterval(95%CI).Continuousvariablesaredescribed withmeanandstandarddeviationormedianandcentiles,as appropriate.Categoricalandbinaryvariablesaredescribed usingproportions.Alogisticregression modelwasusedto test the association between self-reported cultural back-ground andthe presence of at least oneinadequacy. The variablesconsideredinthemodelarelistedinTable2.The finalvariablesinthemodelwereincludedthroughbackward selection,adoptingasignificancelevelofp<0.1.Statistical analysiswasperformedusingSPSS®16.0(SPSSInc.,Chicago, IL)andOpenEpisoftware.6

3.

Results

Completequestionnairesfrom161childrenwerecollected (female53.5%),withmedianage9months(4months21st centile(14children);6months39thcentile(43children); 10 months 55th centile (68 children); 12 months 60th centile (77 children)). The questionnaire was answered bythemother(79.4%),father (19.3%)or other caretakers (1.2%).Themothershadamedianageof32years(P25=27;

P75=36;min=15; max=50 years),had onaverage 1 child and77%ofthemwereemployed.

The cultural background of the sample was diverse: Portuguese 65% (102/161 cases), African 15.5% (24/161), Brazilian 7.7% (12/161), Slavic 3.2% (5/161), Roma 2.6% (4/161),Chinese2.6%(4/161),Indian1.3%(2/161)andother 1.3%(2/161).

Besides the mother, other decision-makers in CF were thefather(60.7%),grandparents(27.7%)andothers(11.6%). Economicdifficultiestobuythechild’sfoodwerestatedby

Table2 Variablesrelatedtofeedingpatternsintroduced inthelogisticregressionmodel.

Child’sage Mother’seducation

Home-madevs.nursery’svs.nanny’sfood Numberofsiblings

Culture(Portuguese/African+Brazilian)a Mother’sage

Mother’sworkingstatus:employedvs.unemployed Childstaysathomevs.atnurseryvs.withnanny Economicdifficultiestobuychild’sfood

Doubtsincomplementaryfeeding

Decision-makersincomplementaryfeeding(mothervs. fathervs.grand-parentsvs.others)

aSelf-reportedculturalbackground.

13%oftherepliers.Theglobal prevalenceofinadequacies was46%(95%CI:38.45---53.66).Thecommonestinadequacy wasavoidanceoflumpysolidfoodsafter10months(66.7%; 95%CI: 55.18---76.46) and the leastcommon was introduc-ingcow’smilkbefore12months(3.4%;95%CI:1.17---9.55). Actualfiguresandproportionsoftheinadequaciesare pre-sented in Table 3 andFig. 1. Surprisingly,some expected inadequacieswerenotreported.

The logisticregression model showeda weak evidence that children of African or Brazilian parents have more inadequacies (OR=3.31;95%CI:0.87---12.61; p=0.079)and thatBrazilianchildrenhaveahigherburdenofinadequacies (1vs.>1inadequacy)comparingwithPortugueseorAfrican descendents (p=0.073). Moreover, for each increase in 1 month in the age of the children, there was a 36.7% increase on the odds of inadequacies (OR=1.37; 95%CI: 1.20---1.56;p<0.001).Finally,aweakevidenceofincreased odds on inadequacies from the influence of grandparents on complementary feeding was found (OR=3.69; 95%CI: 0.96---14.18;p=0.058).

4.

Discussion

The results of this study emphasize the high prevalence ofinadequaciesduringthecomplexandmultifactorial pro-cess of CF. Almost half of the sample reported at least oneinadequacyduringtheweaningprocess.The most fre-quentinadequacywasthedelayinintroducinglumpysolid food. Furthermore, we observed a tendency for higher proportion of inadequacies inchildren of parent-reported African/Brazilian compared to Portuguese background, althoughwithalowlevelofevidence.

Thisstudyhasanexploratorynature.Thesettingforthe studywaschosentoincreasetheprobabilitytocollectdata froma wide rangeof familiesfrom thedifferent cultural backgroundsfoundinGreaterLisbon.Conveniencesampling limitstheconfidenceandabilitytogeneralizetheresults. Caretakersofchildrenthatattendedwell-childvisitsatthe communityhealthcentrewereinvitedtoanswerthe ques-tionnaire.Thus,childrenfromfamilieswithhigherincomes maybeunderrepresented,astraditionallytheyareassisted bypaediatriciansintheirprivateoffices.Ontheotherhand, underprivilegedchildrenareknownnottoattendwell-child visitsregularly.Infact,familiesreporteda23% unemploy-mentrate,muchhigherthanofficiallydeclaredforthissame regionattheendof2010.7Therefore,thestudymayhave sufferedfromarecruitmentbiastowardsthecentral socio-economicquintiles.

Thiscross-sectionalstudywasbasedonthefeeding prac-tices of each child at the time of the questionnaire and targetedcontemporarychildrenfrom3to24monthsofage, in an attempt toavoid recall bias. This option, however, precluded theassessment ofpriorinadequacies (e.g.,ifa childhadbeenweanedbefore4months,butthe question-nairewasfilledattheageof6months,thatinadequacywas missed).

The entirely voluntary participation may have led to a healthy volunteerbias, which cannot beaccounted for, sincedataonnon-responders werenot collected.Also,in spiteoftheeffortstomakethesurveyresultsanonymous, two of the researchers in the study (SN, MAn) were also

Table3 Prevalenceofinadequacies,accordingtothe2008ESPGHANrecommendations. Inadequacyaccording

toESPGHAN

Prevalenceofinadequaciesineachagegroup(ageinmonths) Prevalenceofeach inadequacy(%;95%CI) <4 [4;6] [6;7] [7;10] [10;12] [12;24] Introductionof complementaryfoods<4 months 1/20 --- --- --- --- --- 1/20 (5.0%;0.9---23.6%) Introductionof complementaryfoods>6 months --- --- --- 1/21 0/5 0/72 1/98 (1.0%;0.2---5.6%) Introductionofgluten<4 months 0/20 --- --- --- --- --- 0/20 (0.0%;0.0---16.1%) Introductionofgluten≥7 months --- --- --- 3/11a 2/5 9/72 14/88 (15.9%;9.7---25.0%) Avoidanceofsolidlumpy

food≥10months

--- --- --- --- 1/1a 47/71a 48/72

(66.7%;55.2---76.5%)

Cow’smilk<12months 0/20 1/27 0/16 1/21 1/4a --- 3/88

(3.4%;1.2---9.6%)

Additionofsalt<12months 0/20 0/27 1/16 3/21 2/5 --- 6/89

(6.7%;3.1---13.9%) Additionofsugar<12 months 0/20 1/27 0/16 1/21 0/5 --- 2/89 (2.2%;0.6---7.8%) Introductionofhoney<12 months 1/20 0/27 0/16 0/21 0/5 --- 1/89 (1.1%;0.2---6.1%) Avoidingordelaying introductionofspecific foods>12months --- --- --- --- --- 23/65a 23/65 (35.4%;24.9---47.5%) Anyinadequacyb 2/20 2/27 1/16 8/21 2/5 59/72 74/161 (45.9%;38.4---53.6%) a Missingvalues.

b Morethanoneinadequacyhasoccurredinsomechildren.

Complementary foods <4 months (n=20)

No complementary foods >6 months (n=98)

Gluten <4 months (n=20) Gluten ≥7 months (n=88) No solid lumpy food ≥10 months (n=72) Cow’s milk <12 months (n=88) Salt <12 months (n=89) Sugar <12 months (n=89) Honey <12 months (n=89) Avoidance of specific foods after 12 months (n=65)

0% 20% 40%

Frequency of inadequacy

60% 80% 100%

healthcareprovidersinvolvedinthehealthsurveillanceof thechildrenincludedinthestudy.Thismayhaveinduceda socialacceptabilitybias.Takentogether,itisexpectedthat these biases may reduce the reporting of inadequacies, leadingtoanunderestimationofitstrueprevalence.

Inspite oftheshorttimespanof thestudy(4months) anda scheduled interval of 3 monthsfor well-child visits inchildrenabovetheageof6monthsaccordingtothe Por-tugueseHealthSurveillanceProgram,itisimpossibletorule outthatthequestionnairemighthavebeenansweredmore thanoncebycaretakersofthesamechild(e.g.,atages4and 6months).Thiswouldleadtoaviolationoftheassumptions ofthelogisticregressionmodel.Duetotheanonymousdata collection, onecannot besure of howoftenthis multiple observations(ifany) might have happened. Nevertheless, cases were matched for child’s gender, mother’s level of education,self-reported culturalbackground and ageand only threecases were found that might matchwith each other.Hence, onemay assumethat nomajorviolation of the assumptions of the model occurred. Finally, due to timerestrictions,thenumberofchildrenrecruitedwaslow. This explains the large widthof the confidence intervals, especially for inadequacies occurring before4 months of age.

The most frequent inadequacy was the delay in intro-ducing lumpy solid food. This trend has already been reported in other studies with significantly more feed-ing problems in these children notably at the age of 7 years-old.8Onepossibleexplanationtokeepoffering homo-geneousconsistencyfoodmaybethegeneraltendency of parents to overprotect and turn their child’s meals eas-ier.Nevertheless, itis assumed that around10 monthsof age, there may be a ‘‘window of opportunity’’ to intro-ducemoresolidfood,afterwhich,feedingdifficultiesmay develop.1

Only two children had either premature (before 4 months) or delayed (after the age of 6 months) intro-duction of CF, which is less frequent than reported in previous studies conducted in Portugal.9,10 Also in Swe-den,fewchildrenreceiveearlyorlateCF.11Besides,cow’s milk had only been introduced in 3.4% of the children younger than 12 months in our study, which is substan-tially inferior to the 30% previously verified in Greater Lisbon.9

InmostPortuguesePublicPrimaryHealthCentres, includ-ing the one where the study was performed, caregivers areadvised todelay the introduction of somefoods until 24 months (e.g., soft fruits, seafood, nuts), egg white (until13months) andtomaintaina gluten-freedietuntil the 6thmonth of life. This mayhelp toexplain the high reported prevalence of these behaviours in our survey, meaning that parents are adhering to some local recom-mendations.InthePrimaryHealthCentrewherethestudy wasundertakenandbeforeits beginning,healthcare pro-fessionals used topromote delayed introduction of these foodstoprotectagainstallergyandceliacdisease. Delay-ingfood introduction is notin agreementwith the latest evidence-based practice as summarized in the ESPGHAN recommendationsandcan actuallyincrease theincidence of these diseases. It is now recommended to introduce smallamountsof gluten between4 and7 monthsof age, preferablyalong withbreastfeeding.Thisattitudeshowed

a decreaseinthe occurrenceofceliacdisease autoimmu-nityinchildrenatincreasedriskforthedisease.12 Delaying or avoiding potentially allergenic foods (such as fish or eggs) donotseem toreduce allergy, notevenin children with afamily risk of atopy, moreover, it can cause nutri-tional deficits with cognitive and immune repercussion.1 Evidence shows that regular fish consumption before 12 monthsofageappearstobeassociatedwithareducedrisk of allergic disease and sensitization tofood and inhalant allergensduringthefirst4yearsoflife.13Anotherexample, a decrease in the incidence of peanut’s allergy in Israeli children was found in those that had introduced peanuts earlier, at a regular and important quantity basis. There-fore, some authors supportearly introduction of peanuts during infancy, rather than its avoidance.14 On the con-trary,Cow’smilkshouldstillbepostponeduntil12months ofage.Prematureintroductionof cow’smilkisassociated with irondeficiency, sincecow’s milk is a poor source of ironandearlyintroductioncanleadtomicroscopicintestinal bleeding.1,15

Thissurveytookplaceina multiculturalurban area.It hasbeen suggestedthat non-nativeculturestend to com-ply worsewithlocalCFrecommendations.2,3We foundan increased trend for inadequacies in children with African or Brazilian backgrounds, with an estimated threefold increaseoftheoccurrenceofinadequaciesinthesechildren comparing with children with Portuguese ancestry. Immi-grant mothers, usually develop some ‘‘acculturation’’ to the new society but it may be incomplete. Pak-Gorstein et al. reported that foreign mothers with less American ‘‘acculturation’’(notUSAborn,norEnglishspeakersorona shortstay)practicedmoreandmoreprolonged breastfeed-ingthannativeAmericans,mainlyiforiginated fromalow socio-economiclevel.16

The ESPGHANcommittee recognizesthat the evidence supporting CFpracticesis weakandoftenfocused on sur-rogateoutcomes.1Inthiscontext,itisdifficulttoknowthe impactoftheinadequacies foundinourstudy inthe chil-dren’sfuturehealth.Itisalsolargelyunknownifthetrend formorereportedinadequaciesinchildrenofBrazilianand African backgrounds will have a negative repercussion in their health. A longitudinal study designed to assess the impact of these inadequacies on weight, height, blood pressureandneurodevelopmentwouldprovideinsightinto thisissue.

Someevidenceoftheinfluenceofgrandparentson inad-equate CF decisions was unexpected. This issue was not apre-specified hypothesis inourstudyandmust be inter-pretedwithcautionduetolowstatisticalsignificance.Inthe Portuguese society,grandparents have an important influ-encein child bearing andfeeding counselling, due tothe respectfor familytraditions andtheacknowledgement of theirexperienceonchildcare.Hence,theroleof grandpar-entsshouldbefurtherexplored.

Some information provided by the healthcare profes-sionals in this Primary Health Centre about CF was not supportedbythecurrentbestevidence.Onepossible expla-nation for this is the lack of national guidelinesfor child weaningendorsedbythePortugueseHealthAuthoritiesand the majorscientific societies.It is alsoimportant tonote that between the publication of ESPGHAN recommenda-tions (January2008) and ourdatacollection (lastquarter

of2010)30monthshadlapsed.Thispointsouttothe prob-lem of dissemination of information. Furthermore, it has been repeatedly shown that guideline development alone does notchangeclinical practice.17,18 Ourstudy highlights that paediatric residents,whohave a mandatoryrotation in Primary Care Centres, could disseminate relevant and recentpaediatricevidencetobusyprimarycarenursesand doctorswho also have tocare for non-paediatric popula-tions.

This exploratorystudysuggeststhatinadequaciesin CF practicesmaybehighlyprevalentinthepopulationserved by this Portuguese urban Primary Health Centre. Due to several biases that can underestimate the prevalence of inadequacies, these figures should be seen as the best case scenario.The inadequacies maybe morecommonin childrenpertainingtoimmigrantfamilies.Inamulticultural society, ethnic feeding practices with unproved harmful effect should not be discouraged. More attention should begiventoimmigrantcommunitiesiffurtherstudiesshow poorerclinicaloutcomesassociatedtofeedinginadequacies relatedtotheculturalbackground.

Ethical

disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects.The authors declarethat the proceduresfollowed were inaccordance withtheregulationsoftherelevantclinicalresearchethics committeeandwiththoseoftheCodeofEthicsoftheWorld MedicalAssociation(DeclarationofHelsinki).

Confidentialityofdata.Theauthorsdeclarethattheyhave followedtheprotocolsoftheirworkcentreonthe publica-tionofpatientdata.

Righttoprivacyandinformedconsent.Theauthorshave obtainedthe written informed consentof the patients or subjectsmentionedinthearticle.Thecorrespondingauthor isinpossessionofthisdocument.

Conflicts

of

interest

Annex

1.

Questionnaire

delivered

to

the

caretakers

of

children

attending

the

well-child

visits

of

the

Health

Care

Centre

Pedimos-lhe uns minutos para responder a este inquérito que será anónimo e confidencial. Serve para avaliar o nosso trabalho no Centro de Saúde.

Esclareça as suas dúvidas connosco. Quando terminar, coloque na caixa.

Quem responde a este inquérito? Mãe Pai outro cuidador da criança Idade da criança que vem à consulta meses menino menina

1 - O seu bebé bebe apenas leite materno? Sim

Não 2- Dá-lhe papa ou sopa? Sim

Não a) porque começou com esta idade?_______________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ 3 - Come papa com glúten? Sim

Não

4- Come os alimentos passados ou triturados? Sim

Não

5 - Bebe leite de vaca? Sim

Não

6 - Põe sal na comida do seu filho? Sim

Não

7 - Põe açúcar na comida do seu filho? Sim

Não

8 - Come pão ou “bolacha maria”? Sim

Não

9 - Dá mel ao seu filho? Sim

Não

10 - Evitou dar algum alimento depois de ele fazer 12 meses? Sim

Não Se sim, qual/ quais?______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________

1 - Nacionalidade da pessoa que cuida da criança a maior parte do dia:______________ 2 - A cultura da sua família é: Portuguesa Africana Brasileira

Cigana Chinesa Indiana Eslava (Ucrânia/ Russa/ Moldávia) Outra 3 - Idade da mãe:

4 - Quantos filhos tem?

5 - Anos de escolaridade da mãe?

6 - A mãe trabalha? Sim Não 7 - Onde fica o seu filho enquanto a mãe está a trabalhar?

Casa Infantário Ama Outro

8 - Quando não está em casa, onde é feita a comida do seu filho? Casa Infantário Ama Outro

9 - Tem dificuldades em comprar a alimentação do seu filho? Sim Não

10 - Onde lhe deram indicações sobre a alimentação do seu filho?(pode assinalar mais do que uma opção)

Maternidade Centro de saúde Consultório Urgência 11 - No Centro de Saúde têm-lhe falado sobre como alimentar o seu filho. Quem? Médico Enfermeiro Outro

12 - Ficou com alguma dúvida sobre essas informações? Sim Não alimentação a sobre decisões nas ajuda quem casa, em Lá - 13 do seu filho?__________________________________________________________________ família? sua da tradicional alimento algum Deu - 14 A partir de que idade?_________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ Quer deixar algum esclarecimento, opinião ou mensagem? _______________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________

Muito obrigado!

References

1.AgostoniC,Decsi T,FewtrellM,Goulet O,Kolacek S, Kolet-zkoB, et al.Complementary feeding: acommentary bythe ESPGHANCommitteeonNutrition.JPediatrGastroenterolNutr. 2008;46:99---110.

2.Garcia-AlgarO, Galvez F,Gran M,Delgado I,Boada A, Puig C,etal.Eatinghabitsinchildrenunder2yearsoldaccording toethnicorigininaBarcelonaurbanarea.AnPediatr(Barc). 2009;70:265---70.

3.KannanS,CarruthBR,SkinnerJ.Culturalinfluencesoninfant feedingbeliefsofmothers.JAmDietAssoc.1999;99:88---90.

4.Wright AL, Holberg C, Taussig LM. Infant-feeding prac-tices among middle-class Anglos and Hispanics. Pediatrics. 1988;82:496---503.

5.vanOdijkJ,HulthenL,AhlstedtS,BorresMP.Introductionof foodduringtheinfant’sfirstyear:a studywithemphasis on

introductionofglutenandofegg,fishandpeanutinallergy-risk families.ActaPaediatr.2004;93:464---70.

6.DeanAG,SullivanKM,SoeMM.OpenEpi:OpenSource Epidemi-ologicStatisticsforPublicHealth,Versão.www.OpenEpi.com, accessedat13.04.06.

7.Estatística INd. AnuáriosEstatísticos Regionais --- Informac¸ão estatísticaàescalaregionalemunicipal;28November2011, 2010.

8.CoulthardH,HarrisG,EmmettP.Delayedintroductionoflumpy foods to children during the complementary feeding period affectschild’sfoodacceptanceandfeedingat7yearsofage. MaternChildNutr.2009;5:75---85.

9.VirellaD,LynceFJN.Padrãoalimentarnoprimeiroanodevida noConcelhodeCascais.ActaPediatrPort.1999;30:5.

10.LevyAiresA,SousaDAC.Inquéritosobrealeitamentomaterno noDistritodeSetúbal-1993.ActaPediatrPort.1995;4:7.

11.MikkelsenA,Rinne-LjungqvistL,BorresMP,vanOdijkJ.Do par-entsfollowbreastfeedingandweaningrecommendationsgiven bypediatricnurses?Astudywithemphasisonintroductionof cow’smilkproteininallergyriskfamilies.JPediatrHealthCare. 2007;21:238---44.

12.NorrisJM,BarrigaK,HoffenbergEJ, TakiI,MiaoD,HaasJE, etal.Riskofceliacdiseaseautoimmunityandtimingofgluten introductioninthedietofinfantsatincreasedriskofdisease. JAMA.2005;293:2343---51.

13.KullI,BergstromA,LiljaG,PershagenG,WickmanM.Fish con-sumptionduringthefirstyearoflifeanddevelopmentofallergic diseasesduringchildhood.Allergy.2006;61:1009---15.

14.DuToitG, KatzY,SasieniP,MesherD,Maleki SJ,FisherHR, et al. Earlyconsumption ofpeanuts in infancyis associated

withalowprevalenceofpeanutallergy.JAllergyClinImmunol. 2008;122:984---91.

15.SadowitzPD,OskiFA.Ironstatusandinfantfeedingpractices inanurbanambulatorycenter.Pediatrics.1983;72:33---6.

16.Pak-GorsteinS,HaqA,GrahamEA.Culturalinfluencesoninfant feedingpractices.PediatrRev.2009;30:e11---21.

17.CabanaMD,RandCS,PoweNR,WuAW,WilsonMH,AbboudPA, etal.Whydon’tphysiciansfollowclinicalpracticeguidelines? Aframeworkforimprovement.JAMA.1999;282:1458---65.

18.GrimshawJM,ThomasRE,MacLennanG,FraserC,RamsayCR, ValeL,etal.Effectivenessandefficiencyofguideline dissem-inationandimplementationstrategies.HealthTechnolAssess. 2004;8(iii---iv):1---72.