h ttp : / / w w w . b j m i c r o b i o l . c o m . b r /

Environmental

Microbiology

Changes

in

the

microbial

community

during

bioremediation

of

gasoline-contaminated

soil

Aline

Jaime

Leal

a,

Edmo

Montes

Rodrigues

b,∗,

Patrícia

Lopes

Leal

b,

Aline

Daniela

Lopes

Júlio

b,

Rita

de

Cássia

Rocha

Fernandes

b,

Arnaldo

Chaer

Borges

b,

Marcos

Rogério

Tótola

b,∗aInstitutoFederalSul-rio-grandense,Bagé,RioGrandedoSul,Brazil

bUniversidadeFederaldeVic¸osa,DepartamentodeMicrobiologia,LaboratóriodeBiotecnologiaAmbientaleBiodiversidade,Vic¸osa,

MinasGerais,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received26April2016 Accepted5October2016

Availableonline19December2016

AssociateEditor:LucySeldin

Keywords: Bioremediation Gasolinedegradation Soilcontamination Microbialinoculants Inoculantstorage

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Weaimed toverify thechanges inthe microbialcommunityduring bioremediationof gasoline-contaminatedsoil.Microbialinoculantswereproducedfromsuccessiveadditions ofgasolinetomunicipalsolidwastecompost(MSWC)previouslyfertilizedwith nitrogen-phosphorous.ToobtainInoculantA,fertilizedMSWCwasamendedwithgasolineevery3 daysduring18days.InoculantBreceivedthesameapplication,butatevery6days. Inocu-lantCincludedMSWCfertilizedwithN–P,butnogasoline.Theinoculantswereappliedto gasoline-contaminatedsoilat10,30,or50g/kg.Mineralizationofgasolinehydrocarbonsin soilwasevaluatedbyrespirometricanalysis.Theviabilityoftheinoculantswasevaluated after103daysofstorageunderrefrigerationorroomtemperature.Therelativeproportions ofmicrobialgroupsintheinoculantsandsoilwereevaluatedbyFAME.Thedoseof50g/kg ofinoculantsAandBledtothelargestCO2emissionfromsoil.CO2emissionsintreatments withinoculantCwereinverselyproportionaltothedoseofinoculant.Heterotrophic bacte-rialcountsweregreaterinsoiltreatedwithinoculantsAandB.Theapplicationofinoculants decreasedtheproportionofactinobacteriaandincreasedofGram-negativebacteria.Decline inthedensityofheterotrophicbacteriaininoculantsoccurredafterstorage.Thisreduction wasbiggerininoculantsstoredatroomtemperature.Theapplicationofstoredinoculants ingasoline-contaminatedsoilresultedinaCO2emissiontwicebiggerthanthatobserved inuninoculatedsoil.WeconcludedthatMSWCisaneffectivematerialfortheproduction ofmicrobialinoculantsforthebioremediationofgasoline-contaminatedsoil.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradeMicrobiologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisis anopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

∗ Corresponding authors at: Laboratóriode Biotecnologia e Biodiversidade paraoMeio Ambiente,Departamento de Microbiologia,

UniversidadeFederaldeVic¸osa,Av.P.H.Rolfss/n,Centro,Vic¸osa,MinasGerais,Brazil. E-mails:edmomontes@yahoo.com.br(E.M.Rodrigues),totolaufv@gmail.com(M.R.Tótola).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjm.2016.10.018

Introduction

Accidental spillsofgasolineand other petroleum products inthefueldistributionterminals,mainlyduringtruck clean-ing and distribution in pations, are a common cause of soilandwatersystemscontaminationinBrazil.1BTEX

com-pounds(benzene,toluene,ethylbenzene,andxylenes)present ingasolineare highlytoxicand harmfultohumanhealth; amongthese,benzeneisaknowncarcinogenicsubstance.2–4

Thepresence of ethanol in gasoline can increase the sol-ubility of BTEX dissolved in the groundwater and thereby hindering its naturalbiodegradation byincreasingthe per-sistenceofthesecompoundsintheenvironment.5,6Ethanol

can be biodegraded preferably than BTEX, which leads to consumptionofoxygenthatwouldberequiredforthe degra-dationofhydrocarbons.Furthermore,ethanolmaybetoxic orinhibitorytodegradingmicroorganismsofmonoaromatic hydrocarbons.5 CorseuilandFernandes7indicatedthat

con-tamination ofwater table caused by Brazilian commercial gasolinemaybegreaterthanthatbyconventionalgasolines from other countries. This issue stems from the ability of ethanoltoincreasethesolubilityofpetroleumhydrocarbons inwater.Theresultsoftheseexperimentsshowedthat,inthe aqueousphase,fractionsof10–30%ofethanolcanincrease theconcentrationofbenzene,toluene,andxylene(BTX).This effectof co-solvency responsible forthe higher concentra-tionofhydrophobicorganiccompounds inwaterisgreater to xylenes, which are less soluble compounds among all BTXcompoundsandwhenethanolisadded,itssolubilityis enhanced.Thus,it isalsolikelythathigherconcentrations ofethanol in wateraquifers facilitategreater solubility of polycyclicaromatichydrocarbons(PAH),whichareextremely hydrophobicandharmfultothehumanhealth.

Bioremediation has been applied for the recovery of environments contaminated with oil and oil products. Biotechnological processes applied in bioremediation are promisingbecausetheyofferbettercostbenefitthan physico-chemicaltechniques,whicharemoreexpensive,difficultto implement, and require continuous monitoring to achieve desirable results.8–10 Bioremediation techniques have great

developmentalpotentialsinBrazil,astheclimaticconditions ofthiscountryarefavorableforthebiodegradationof contam-inants.

Bioremediationincludesmineralizationortransformation ofcontaminantsintolesstoxicformsbydifferentgroupsof microorganisms.11–13Thisprocess,whichtendstooccur

nat-urally,canbeacceleratedintwoways:(i)bybiostimulation, which is based on stimulation of the catabolic activity of indigenousmicroorganismsbytheadditionoflimiting nutri-entminerals,supplyingoxygenorotherelectronacceptors, andbymaintainingsuitableconditionsoftemperature,pH, andmoistureand(ii)bybioaugmentation,whichisbasedon the inoculation of a population or consortium ofeffective microorganismsfor the degradationofcontaminants.9,14–16

Thesimplestformofbioremediationisnaturalattenuation, whichincludesonlymonitoringofthe naturaldegradation ofthecontaminantinthecontaminatedenvironment with-out any intervention. The comparison between the three bioremediationstrategiesforsoilcontaminatedwithdiesel

demonstratedthattheresultsweresite-specific,varyingwith thesoiltype.17Inthisstudy,wedemonstratedtheefficiencyof

applyingmicrobialinoculantsenrichedfrommunicipalsolid wastecompost(MSWC)forthebioremediationofsoil contam-inated withgasoline.Respirometrictestswere employedto evaluatethemineralizationofgasolineininoculantsandin soilreceivinggasolinecontamination.Changesinthe micro-bialcommunitywereassessedbyanalysisoftheinoculants afterstoragefor103days.

Material

and

methods

Soilcontaminationandcharacterization

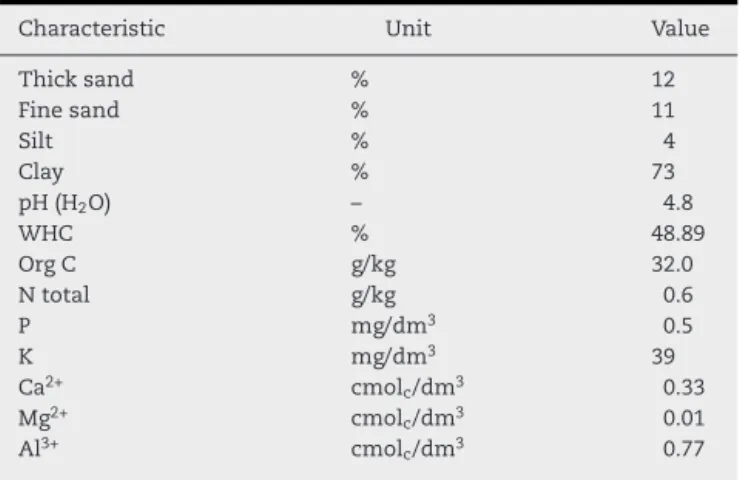

Theexperimentalsoilwas siftedthrough 5-mm meshand identified tobeextremely clayey byphysicaland chemical analyses (Table1). Afteradjusting the moisturecontent of the soilto60% ofthe WHC andthe C:N:P ratioto100:10:1 (assumingCaddedasgasoline),thesoilwascontaminated artificiallywith20mL/kgofgasolinecontainingapproximately 22%ethanol.

Inoculantsdevelopment

TheinoculantswereproducedbyenrichmentofMSWCwith gasoline(50mL/kg).InoculantAreceivedgasolineapplication every3daysforupto18days.Thegasolineapplicationinterval forinoculantBwas6days.TheC:N:Pratioofthecompost wasadjustedto100:10:2,consideringtheamountofcarbon addedintheformofgasolineinthefirstapplication.During inoculantsenrichment,themoisturecontentofthesoilwas maintainedat40–60%oftheWHC.TheInoculantCconsisted ofMSWCfertilizedwithNandPsources,butnogasoline.All treatmentsoilswerestoredunderthesameconditions.

Oildecompositionactivityinthecontaminatedsoilasa functionofinoculantdose

Test treatments were constructed using gasoline contami-natedsoil(20mL/kg)andinoculantsA,BorCthatwereadded

Table1–Physical–chemicalcharacteristicsofsoil.

Characteristic Unit Value

Thicksand % 12

Finesand % 11

Silt % 4

Clay % 73

pH(H2O) – 4.8

WHC % 48.89

OrgC g/kg 32.0

Ntotal g/kg 0.6

P mg/dm3 0.5

K mg/dm3 39

Ca2+ cmol

c/dm3 0.33

Mg2+ cmol

c/dm3 0.01

Al3+ cmol

c/dm3 0.77

Table2–Treatmentssubmittedtorespirometricassay fordeterminingtheappropriateconcentrationof inoculantsforaddingtogasoline-contaminatedsoil.

Treatment Inoculum

concentrations

InoculantA 10,30,or50g/kg

InoculantB 10,30,or50g/kg

InoculantC 10,30,or50g/kg

Soil 0

SterilizedMSWC+Soil(SC+S) 50g/kg SterilizedMSWC+SterilizedSoil(SC+SS) 50g/kg

intheproportionsof10,30,or50g/kgofdrysoilmass.Inthe treatmentsthatused10and 30g/kgofinoculantsA, Band C,sterilenon-contaminatedMSWCwasusedtoensurethe presenceofthesameamountofcompounds(50g/kg)inall treatments.MSWC wassterilizedwithadoseof25Mrad ␥

radiationbya60Cosource.

Threecontroltreatmentswere performed.Control treat-ment 1was constructedusing onlygasolinecontaminated soil.Controltreatment2wasconstructedusinggasoline con-taminatedsoilplussterileMSWC(50g/kg).SterileMSWCwas obtainedusingadoseof25Mrad␥radiationbya60Cosource.

InControltreatment3,thesterilesoilwasaddedwithsterile MSWC(50g/kg).

Threereplicatesforeachtreatmentwereperformed, total-ing36plots.Eachplotconsistedofarespirometric750mLflask connectedto arespirometer equippedwitha CO2 infrared

detectorwithintermittentairflow(SableSystem,NE,USA). Therespirometricanalysiswasperformedfor266hat22–30◦C

(Table2).

Effectoftemperatureontheconservationofmicrobial inoculants

Theinoculantswerestoredattheroomtemperatureorunder refrigeration(6–8◦C).After103daysofstorage,theinoculants

wereappliedto60gofgasoline-contaminatedsoil(20mL/kg) atadoseof30g/kg.Thesoilwassubjectedtorespirometric analysisunderthesameconditionsasdescribedpreviouslyfor 685hat21–32◦C.Aftertherespirometricanalyses,thesoilwas

enumeratedforculturablebacterialpopulationsandmicrobial communityanalysisbyester-linkedfatty acid methylester (EL-FAME).

Enumerationofcultivablebacterialpopulations

Thecultivableheterotrophicbacteriawerecountedbyplating serial dilutions (in sodium pyrophosphate 1g/L on nutri-entagar–HIMEDIA®).Toinhibitfungalgrowth,100mg/Lof cycloheximidewas added tothe medium.Theplates were incubatedat30◦Cuntildevelopmentofcolonies.

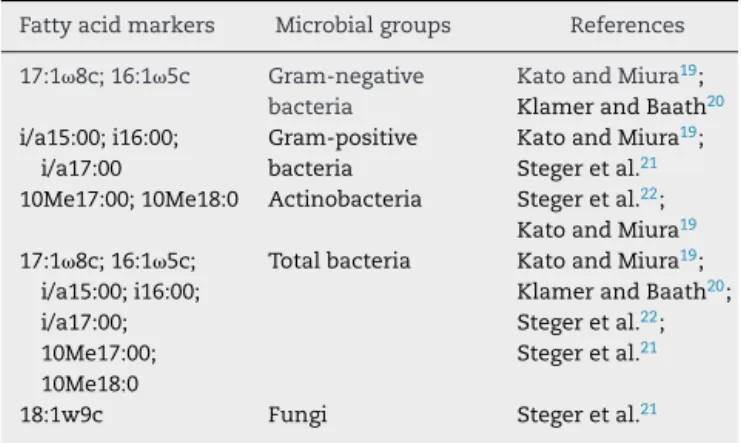

Microbialdiversitybyester-linkedfattyacidmethylester analysis

Beforeextraction andanalysis ofEL-FAMEs todescribethe microbial communities of the inoculants, we developed a methodtoeliminatetheinterferenceofhydrocarbonsinthe

Table3–Fattyacidsmarkersusedfordeterminingthe microbialgroupspresentininoculantsandsoil.

Fattyacidmarkers Microbialgroups References

17:18c;16:15c Gram-negative bacteria

KatoandMiura19;

KlamerandBaath20

i/a15:00;i16:00; i/a17:00

Gram-positive bacteria

KatoandMiura19;

Stegeretal.21

10Me17:00;10Me18:0 Actinobacteria Stegeretal.22;

KatoandMiura19

17:18c;16:15c;

i/a15:00;i16:00; i/a17:00; 10Me17:00; 10Me18:0

Totalbacteria KatoandMiura19;

KlamerandBaath20;

Stegeretal.22;

Stegeretal.21

18:1w9c Fungi Stegeretal.21

samples. For this purpose, to each sample, 3mL ofsterile distilledwaterand1mLofhexanewereadded.After homog-enization,thesampleswerecentrifugedat544×gfor15min.

Immediatelyafterwhich,thenon-polarphasecontainingthe hydrocarbons was removed,followed by removalof water. Waterwasonlyusedtoseparatethecompostfromhexane. Theentireprocesswasrepeatedthreetimes.

EL-FAMEswere extractedaccordingtothemethodgiven byShutterandDick18withsomemodifications.Areduction

of2/3ofthevolumeofreagentsandsampleswasperformed. Inthelaststepofthismethod,thesolventcontainingFAMEs was evaporatedunder vacuumuntilcomplete dryness and theresiduewasresuspendedin1/3rdoftheoriginalvolume. TheextractswerethenanalyzedintheAgilentTechnologies 7890gaschromatograph.Theidentificationofthefattyacids wasperformedbySherlockMicrobialIdentificationSystem® (MIDI, Newark,DE, USA),usingthe referencelibrariesITSA 1.0®,IR2A1®,orRTSBA6®.Fattyacidsmarkersofmicrobial groupsareshowninTable3.

Results

Theinoculantdoseeffectonhydrocarbonbiodegradation

ingasoline-contaminatedsoil,populationsofcultivable

bacteria,andsoilmicrobialcommunity

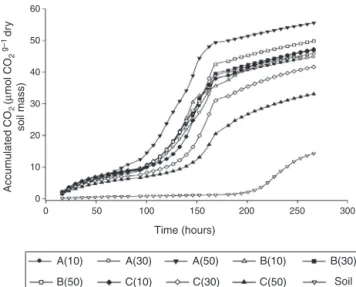

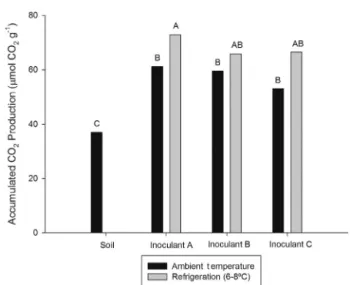

Intherespirometrictests,asignificantinteractionwasnoted betweentheconcentrationandtypeofinoculantsaddedto gasoline-contaminatedsoil.TheadditionofinoculantsAand B showed greater CO2 evolution at the application of the largestdoseof50g/kg.ForinoculantC,inverseresponsewas observed,thatis,thehigherthedose,lowerwastheCO2 emis-sion(Fig.1).

50

40

30

20

10 60

0

Accum

ulated CO

2

(

µ

mol CO

2

g–1

dr

y

soil mass)

0

A(10) A(30)

C(10)

A(50) B(10)

B(50) C(30) C(50)

B(30)

Soil

50 100 150

Time (hours)

200 250 300

Fig.1–CO2emissionbygasoline-contaminatedsoil (20mL/kg).Inthesoil-treatment(Soil),inoculantswerenot added.Inothertreatments,theinoculantsA(A),B(B),orC (C)wereadded.Thepresenteddatareferstothetreatments with50g/kgofinoculants.InoculantsAandBreceived nutrientspluswaterandgasolineindistincttimesforthe enrichmentofhydrocarbonoclasticpopulationsInoculantC referstoMSWCwithnogasolineadded.

C.Analyzingthecurvesloperevealedthatthemaximum emis-sionratesdidnotdifferbetweeninoculantsAandB.However, theacceleratedphaseofCO2emissionbeganalittleearlier inthetreatmentwithinoculantA.Theresultofthese differ-enceswasgreaterforoverallCO2emissionsinthetreatment withinoculantA.Fordoses10and30g/L,nodifferencewas notedbetweentheinoculantsontheCO2emissions (exclud-ingtheinoculantCappliedattherateof30g/L,whichresulted inCO2emissionlowerthanthatwithinoculantsAandB).

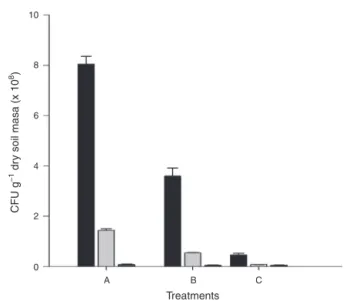

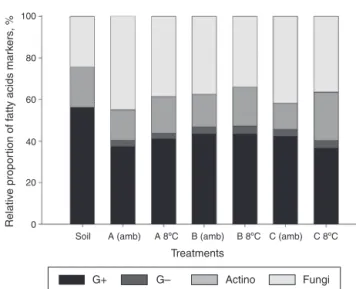

The addition of inoculants A and B to gasoline-contaminatedsoilshowedgreatercountsofcultivablebacteria (Fig.2).Intheuninoculatedtreatment,bacterialcountcould notbeperformedowingtotheprevalenceoffungiintheplate despitetheadditionofcycloheximidetotheculturemedium. The fatty acid profiling of gasoline-contaminated soil revealedthatinthetreatmentwithnoinoculants(Soil) pre-dominated fatty acid markersof Gram-positive bacteria in relationshiptothenumberoffungiandactinobacteria mark-ers.MarkersofGram-negativebacteriawerenotdetectedin thistreatment(Fig.3).TheMSWCaddictioninthesoilresulted onthereductionoffattyacidmarkersofthesoilfor actinobac-teriaandenhancementinthe numbersoffungiforallthe treatments,withgrowthofGram-negativebacteriamarkers insomeoftreatments(Fig.3).Thelatterbacterialgroupwere detectedinalltreatmentgroupsinoculatedwithinoculantC andonlyataparticulardoseofinoculantsA(10g/kg)andB (50g/kg),withlowrelativeproportionascomparedwiththe markersofothergroups(Fig.3).Ininoculatedsoils,therelative proportionofmarkersforfungiandGram-positivebacterial fattyacidswasalwaysmoreabundant.

Regardingtheprofileoftotalfattyacidsinsoil,the arrange-ment oftreatments byPCA was influenced bythe type of

3.5

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

CFU g

–1 dr

y soil mass (x 10

8)

0.5

0.0

A(10) A(30) A(50) B(10) B(30)

Treatments

B(50) C(10) C(30) C(50)

Fig.2–Heterotrophicbacterialcountafterapplicationof inoculantstogasoline-contaminatedsoilatconcentrations 10,30,or50g/kg.Thenumbersinparenthesisindicatethe doseofinoculants(g/kg).InoculantA(A);inoculantB(B); inoculantC(C).InoculantsAandBreceivednutrientsplus waterandgasolineindistincttimesfortheenrichmentof hydrocarbonoclasticpopulations.InoculantCrefersto MSWCwithnogasolineadded.

inoculantaddedtothesoil(Fig.4).IngroupI,thesamplesof uninoculatedtreatment(soil)weregrouped,whichpresented anextremelydifferentprofilefromthoseoftreatmentgroups receiving the inoculants. The group II included treatment groupscontainingsterileMSWC(SC+SS)andthenon-sterile soil inoculated with sterileMSWC (SC+S). The treatments withInoculantC(applicationofcompoundwithoutgasoline)

100

80

Relativ

e propor

tion of f

atty acids mar

k

ers

, %

60

40

20

0

Soil A(10) A(30) A(50) B(10) B(30)

Treatments

B(50) C(10) C(30) C(50)

G+ G– Actino Fungi

Fig.3–Theproportionofrelativemarkersoffattyacidsfor themicrobialgroupsingasoline-contaminatedsoilafter applicationofinoculants.Gram-positive(G+),

Gram-negative(G−),actinobacteria(actino),andfungi.The

4

2 S

I

IV

III

II

C

C

SC+SS

SC+S C

B A A A

B

B

0

PC2 (20.79%)

–2

–4

–10 –5

PC1 (63.85%)

0

Fig.4–Principalcomponentsanalysisofthefattyacid profilesofgasoline-contaminatedsoilinresponsetothe applicationofinoculants.SC+S:non-sterilesoilinoculated withsterilecompound;SC+SS:sterilizedsoilplus

sterilizedcompost;S:soil;C:soilinoculatedwith

unenrichedcompound;A:soilinoculatedwithinoculantA; B:soilinoculatedwithinoculantB.GroupI:soilsamples withoutinoculants;GroupII:soilsampleswithsterile compound;GroupIII:soilsampleswithunenriched compound;GroupIV:soilsampleswithinoculantsAandB.

werepooledingroupIII,whilethetreatmentswiththe addi-tionofinoculantsAandBweregroupedingroupIV.

Viabilityoftheinoculantsandmicrobialdiversityafter storage

Storageresultedinasignificantreductioninthe densityof heterotrophicbacteriaintheinoculants(Fig.5).Thecooling temperaturewasfoundtobethemostsuitablefor maintain-ingtheviabilityofthebacterialpopulationoftheinoculants. Higher counts of bacteria were obtained for inoculant A, exceptduringstorage atroom temperature, acondition in whichnodifferenceintheresultswasnotedamongthethree inoculants(Fig. 5). Thehighercountsforinoculants Aand BascomparedtothatofinoculantC(whichdidnotreceive gasolineapplication)indicatethattheapplicationofthisfuel favoredthegrowthofhydrocarbonoclasticpopulations.

Afterstorage,areductionwasnotedintherelative propor-tionoffattyacidsmarkerfromGram-positivebacteria,while thatofmarkersforfungiandactinobacteriawereincreased (Fig.6).TherelativeproportionofmarkersforGram-negative bacteriaremainedconstantforinoculantA,butthoseof inoc-ulantsBandCdecreased.

Thestorageatboththetemperaturesresultinginchanges onthetotalfattyacidsprofilesofinoculants(Fig.7).PCA anal-ysisrevealedthatthefattyacidprofilesofthesamplesafter storageatroomtemperatureorundercoolingwasmostly sim-ilartoeachotherthanwiththesamplesbeforestorage(Fig.7). Somediscrepancieswerenoticedintheprofilesoffattyacids ofthesamesamplestoredatdifferenttemperatures(Fig.7), demonstratingtheeffectofthisvariableonthecomposition ofthemicrobialcommunityofinoculants.

10

8

6

4

CFU g

–1 dr

y soil masa (x 10

8)

2

0

A B

Treatments

C

Fig.5–Heterotrophicbacterialcountoftheinoculantsafter 103daysofstorageatdifferenttemperatures.Theblackbar correspondstoheterotrophicbacterialcountbeforestorage ofinoculants.Thelightergraybarafterstorageunder refrigeration(6–8◦C)anddarkgraybarafterstorageatroom

temperature.InoculantA(A);B(B);andC(C).InoculantsA andBreceivednutrientspluswaterandgasolineindistinct timesfortheenrichmentofhydrocarbonoclastic

populations.InoculantCreferstoMSWCwithnogasoline added.

100

80

60

40

20

Relativ

e propor

tion of f

a

tty

acids mar

k

ers

, %

A A amb B B amb C C amb

Treatments

B 8ºC

A 8ºC C 8ºC

G+ G– Actino Fungi

Fig.6–Therelativeproportionoffattyacidsmarkersfor microbialinoculantsgroupsbeforeandafterstoragefor103 daysattheroomtemperature(amb)andunderrefrigeration (6–8◦C).Gram-positive(G+),Gram-negative(G

−),

actinobacteria(actino),andfungi.InoculantA(A);B(B);and C(C).InoculantCreferstoMSWCreceivingnutrientsand wateraswellasinoculantsAandB,butnogasoline applicationfortheenrichmentofhydrocarbonoclastic populations.

2

A 8ºC A bs

B bs

C bs C amb

A amb

B amb B 8ºC

C 8ºC 1

0

–1

PC2 (22.89%)

–2

–4 –2 0 2

PC1 (58.37%)

4 6

Fig.7–Principalcomponentanalysis(PCA)ofthefattyacid profilesofgasolineinoculantsbefore(bs)andafterstorage atroomtemperature(amb)andunderrefrigeration(8◦C).A,

B,andC:samplescollectedimmediatelyafterthe

incubationperiodMSWCwithdifferentdosesofgasoline. InoculantA(A);B(B);andC(C).InoculantsAandBreceived nutrientspluswaterandgasolineindistincttimesforthe enrichmentofhydrocarbonoclasticpopulations.Inoculant CreferstoMSWCwithnogasolineadded.

temperature. The inoculants A and B, which received fuel applicationeven beforestorageshowed asmaller range of totalfatty acidsthan inoculantC withoutfueladdition(35 fatty acids for both inoculants). This observation can be attributedmainly tothe reductioninthe number ofchain fatty acids between 10 and 16 carbons, probably because ofthe effect ofadding gasoline to MSWC. Thiseffect can be attributed to the toxicity of light hydrocarbons as the enrichment of a smaller number of populations. In both thecases,the finalresultwas areductioninthe microbial diversity.Underrefrigerationcondition,thereduceddiversity oftotalfattyacidswaslesserthanthatatroomtemperature. Themaineffectsofstorage,regardlessofthetemperature usedontotalfattyacids,weredecreasednumberandamount ofchainfattyacids(10–16carbons)andincreasedabundance ofchainfattyacids(17–20carbons)(datanotshown).

Thestorageeffectofinoculantsintheirefficiencyto stimulatebiodegradationofgasoline,impactoncultivable bacterialpopulations,andsoilmicrobialdiversity

Thestoragetemperatureeffectofinoculantsontheemission ofCO2fromsoilcontaminatedwithgasoline

The respirometric assays with gasoline-contaminated soil inoculated with 30g/kg of inoculants revealed interaction betweenthetypeofinoculantaddedtothesoilandthe stor-agetemperature.MaximumCO2 emissionwasobtainedfor treatmentswithinoculantsstoredunderrefrigeration(Fig.8). However,evenwhenstoredattheroomtemperature,the inoc-ulantsstimulatedCO2emissionfromthecontaminatedsoilas comparedtouninoculatedone.

Fig.8–ThetotalCO2production(molCO2g−1)from gasoline-contaminatedsoilafterapplicationofthe inoculantsstoredatdifferenttemperatures.Thetreatment meansfollowedbythesameletterdonotdifferat5% probabilitybyTukey’stest.InoculantA(A);B(B);andC(C). InoculantsAandBreceivednutrientspluswaterand gasolineindistincttimesfortheenrichmentof hydrocarbonoclasticpopulations.InoculantCrefersto MSWCwithnogasolineadded.

Storagetemperatureeffectonthebacterialcount

Thetreatmentswithinoculants showedthat thecultivable bacterialcountwassignificantlyhigherthanthatof uninoc-ulated soil (Fig. 9), regardless of the storage temperature. The bacterial countin the soil with inoculant A storedat roomtemperaturewasgreaterthanthatofsoiltreatedwith thesameinoculantstoredunderrefrigeration.Theopposite was observed with the treatmentsreceiving applicationof

Fig.9–Thecountofheterotrophicbacteriain

gasoline-contaminatedsoilafterapplicationofinoculants storedatroomtemperature(amb)andrefrigeration(8◦C).

100

80

60

40

20

0

Soil A (amb) B (amb)

Treatments

Relativ

e propor

tion of f

a

tty acids mar

k

ers

, %

C (amb)

A 8ºC B 8ºC C 8ºC

G+ G– Actino Fungi

Fig.10–Theproportionoffattyacidmarkersonthe microbialgroupsofgasoline-contaminatedsoilafter applicationofinoculantsstoredatroomtemperature(amb) andunderrefrigeration(8◦C).Gram-positive(G+),

Gram-negative(G−),actinobacteria(actino),andfungi.

InoculantA(A);B(B);andC(C).InoculantsAandBreceived nutrientspluswaterandgasolineindistincttimesforthe enrichmentofhydrocarbonoclasticpopulations.Inoculant CreferstoMSWCwithnogasolineadded.

inoculantC.NoeffectofinoculantBunderstoragecondition wasnoticedonthecountofcultivableheterotrophicbacteria inthesoilafterthebiodegradationexperiment.

Theeffectofstoragetemperatureonthestructureof microbialcommunityingasoline-contaminatedsoil

Inthetreatmentgroupwithnoinoculation(Soil), predomi-natedmarkersoffattyacidsofGram-positivebacteriawere found (Fig. 10). No Gram-negative bacteria markers were detectedinthis treatment, but this group was detectedin alltreatmentswithinoculation.Inthesetreatments, a pre-dominanceofmarkersofGram-positive bacteriaand fungi wereobserved.Therelativeproportionoffattyacidmarkers foractinobacteriawashigherintreatmentswiththe appli-cationofinoculantsstoredunderrefrigeration,concurrently withthedecreaseinfungalmarkers.Therelativeproportion ofGram-negativebacteriaremained the sameaccording to storagetemperature.

AccordingtothePCAanalysisforthetotalfattyacidsinsoil, the corresponding treatment ofuninoculated soil revealed the most distinctive fatty acid profile, showing the effect of inoculation of soil on the profile of fatty acids on the same(Fig.11).Thesamplescorrespondingtotheinoculated treatmentsformedarelativelyhomogeneousgroup,withthe exceptionofthetreatmentreceivingapplicationofinoculant Cstoredatroomtemperature.

Discussion

In this work, we demonstrated that the addition of MSWC,enrichedor notwithmicrobial hydrocarbonoclastic

2

0 Soil

C. 8ºC

A. 8ºC

C. amb B. 8ºC

B. amb A. amb

–2

–4

–10 –5

PC2 (19.14%)

PC1 (51.30%)

0

Fig.11–Principalcomponentanalysis(PCA)ofthesoil fattyacidprofilesafterapplicationofinoculantsstoredat roomtemperature(amb)andunderrefrigeration(8◦C).Soil

referstouninoculatedcontrol.InoculantA(A);B(B);andC (C).InoculantsAandBreceivednutrientspluswaterand gasolineindistincttimesfortheenrichmentof

hydrocarbonoclasticpopulations.InoculantCrefersto MSWCwithnogasolineadded.

populations, promoted the biodegradationof hydrocarbons fromgasoline-contaminatedsoils.Chenetal.10showedthat,

amongthetechniquesforsoildecontaminationbypetroleum hydrocarbons,theuseofMSWCwasefficientand inexpen-sive,asitincreasesthecontentoforganicmatteraswellas thefertilityofthesoil,causinganincreaseinthedensityand diversityofmicroorganismsinthecompound.

degradation)reducedtheCO2emissionintensityatthesame time.Thisobservationwasconfirmedbythecorresponding treatment,inwhichalagphasethatlasteduntilalatertime wasnotedwiththedeclineinCO2emissionsbytheinoculated samples.TheexponentialgrowthphaseofCO2emissionwas extremelyshort.Attheendoftheincubationperiod,theshape ofCO2emissioncurvesapproachingoftheinoculated treat-ments.Thisobservationprovesthatthehydrocarbonexhaust inthistreatmentintermsofbiodegradation(CO2emissions) wasextremelylow (comparedtothat inothertreatments). Therefore, substrate limitation inthis treatment may have beencausedbythefrequentinjectionofairinthemicrocosm. Thehighercountofcultivablebacteriainsoilappliedwith theinoculantsAandBascomparedtoinoculantC demon-stratedthattheprocedureofaddingfueltotheMSWCfavored theenrichmentofhydrocarbonoclasticbacterialpopulations adaptedtothe toxiceffect ofthis fuel.Theincreaseofthe fungalmarkersaftertheinoculationincontaminatedsoil indi-catedthatthisgroupcanberelatedwiththebiodegradation ofhydrocarbons.Thisobservation wasconsistent withthe experimentsofSannietal.,23whorevealedthatpriorexposure

ofmicrobialcommunitiesinducesaphysiological selection andadaptationofmicrobialpopulationscapableof catabo-lizingit.Fungalwasthegroupwithmajorincreaseafterthe inoculation(InoculantsA,BandC)(Fig.3),therefore,we sug-gestthatthegreaterhydrocarbonoclasticabilitiesinsoilmay beprovidedbyfungalpopulations.

TheextendedlagphaseobservedintheproductionofCO2 on the uninoculatedtreatment may indicate a toxiceffect of gasoline on the native soil organisms24,25 or even at a

lowinitialdensity.IntheBraziliancommercialgasoline,both monoaromatic hydrocarbonsbenzene,toluene,xylene, and ethanol (BTEX) contribute to the toxicity of the fuel. Due to the lipophilic property of BTX, they accumulate in the cellplasmamembrane,causingunspecificpermeabilization thereof.26–30Thus,thesecompoundsinterferewiththe

mem-braneintegrityaswellastheirfunctionasabarriermatrixfor enzymesandasanenergytransducer.27,28

Theenumerationofheterotrophicbacteriathroughplate cultureafterstoragewithand without refrigeration(Fig. 5) confirmedthatcellstorageatlowtemperaturescanbe con-sideredinroutinepracticeformaintainingcellviabilityover a long period of time. However, in soils receiving inocu-lant A after storage, a heterotrophic bacterial density of approximately30%greaterwasnotedinthetreatmentwith inoculantsstoredatroom temperatureincomparisonwith inoculantstoredunderrefrigeration(Fig.9).Giventhese pop-ulationdata,themaximumCO2emissionwasnotedinthe treatmentwiththehighestdensityofcultivableheterotrophic bacteria.However,thisrelationshipwasnotconfirmed,and the greater evolution ofCO2 was observed for treatments whentheinoculantswerestoredunderrefrigeration.These data reveal that bacterial populations of uncultivable, cul-tivablecellpopulations,viablebutnotcultivable(VBNC),and others(e.g., fungiandArchaea)were betterinthe degrada-tionofhydrocarbonsfromgasolinestudiedinthemicrocosm system.Theresultsemphasizedtheadvantageofusing micro-bialinoculantsasMSWCbecauseitmaycontainuncultivable microbial populations important for the biodegradation of contaminant complexes, as exemplified bythe mixture of

hydrocarbonsdetectedingasoline.Specificallyfor hydrocar-bons, no work relatedtoVBNCstate cellactivity has been reported for the degradation of these compounds. In this state cell,bacterial cells are aliveand capableof perform-ingmetabolicactivity,albeitunabletogrowinculturemedia employedroutinely forgrowth.31,32 However,some authors

have reported that bacterial cells in the VBNC state can degradepolychlorinatedbiphenyls33–35aswellassome

hydro-carbons,whicharehighlyrecalcitrantcompounds.36Thus,it

can beinferred thatcells inthis state canalsoparticipate inthecatabolismofhydrocarbonsincontaminated environ-ment.Zhangetal.37 showedthat,inoil-contaminatedsoils,

the physiologically active microbial community was larger thanthecultivablebacterialcommunity.Theabilitytogrowin aculturemediaisnotnecessarilydirectlyrelatedtothe abun-danceofaparticularmicroorganisminthesoil.Stefanietal.38

analyzedoil-contaminatedsoilbydependentand indepen-dentcultivationmethodsandfoundthatsometaxa,although beingpresentingreatabundanceinthesoil,cannotbe culti-vatedevenwhendifferentculturemediaisused.

Thechangesinthefattyacidprofileoftheinoculatedsoil indicate thatthemicroorganismspresent intheinoculants couldthriveinthegasoline-contaminatedsoil(Figs.3and10). Theeffectsofinoculationinthesoilweretheappearanceof fatty acidmarkerGram-negativebacteria(16:15c)insome treatments, reduced actinobacteria markers,and increased fungi markers. The increased relative proportion of fungi markersseemstoberelatedtotheprevalenceofthisgroup inMSWC(Fig.6)aswellasitshydrocarbonoclasticand adap-tative abilities in different storage temperatures. Although actinobacteriaareextremelyversatileandefficientin degrad-ingawiderangeofhydrocarbons,37,39 inoculationmayhave

reducedsomepopulationsofthisgroup,possiblyasaresult ofcompetitionfromothermicrobialpopulationsoriginating frominoculants.

Thestoragetemperatureoftheinoculantsinfluencestheir efficiency in stimulating hydrocarbon degradation in soil. Comparingthesametreatmentswiththeapplicationof inoc-ulantstogasoline-contaminatedsoilbeforeandafterstorage revealedareductioninthedegradationrateandtotal degra-dationofthefuelinthetreatmentsappliedwiththestored inoculants.Thisobservationmayberelatedtothereductionof cultivablebacterialpopulationintheinoculantsafterstorage (Fig.6).

Changesintherelativeproportionofthefattyacid mark-ersafterinoculationofsoilwithinoculantsstoredfor103days included the appearance of Gram-negative bacteria mark-ers,reductioninthe countsofGram-positivemarkers, and increased fungal markers (Fig. 10). This effect was simi-lartothatobservedwhennewlyproducedinoculantswere applied to soil, (Fig. 3) except when no significant reduc-tion in the count of Gram-positive bacteria was noted (in various treatments,the effectwasthe opposite,that is,an increasednumberofGram-positivemarkerswererecorded). TheabsenceofGram-negativebacterialmarkersin gasoline-contaminatedsoilanduninoculatedsoilwerenoted,although a wide range of representatives ofthis group possess the ability tocatabolize hydrocarbons,40,41 suggesting that this

attributedtothesoilandMSWCstorageconditionsusedthat weredryatroomtemperatureforafewweekspriortothis study.Theosmotic stress subjected tothe soiland MSWC favoredthereduction/disappearanceofGram-negative bacte-ria,whileGram-positive,actinobacteria,andfungiwerefound tobemoreresistanttothisstress.42,43 Inaddition,

gasoline-contaminatedsoilandthetoxiceffectsoflighthydrocarbons inthisfueloverthemicrobialcellsmayhaveledtothe extinc-tionofthefewmembersofsomepopulationofGram-negative bacteriainthesoil.

Conclusions

MSWCisasuitablesubstrateforthedevelopmentofmicrobial inoculantsforthebioremediationofgasoline-contaminated soils. Theefficiency of microbial inoculants for the degra-dation ofhydrocarbons from gasoline is influenced bythe inoculantdoseappliedtothesoil.Atdoses>10g/kg, inocu-lantsenrichedwithfrequentadditionsofgasolineweremore efficientthanonlyMSWCenrichedwithmineralnutrients(N, P)indegradation.Thestoragetemperatureinfluencedthe effi-ciency ofinoculantson hydrocarbon biodegradation inthe gasolineconstituentsofsoil,ofwhichrefrigeratedstoragewas foundtobemoreefficientthanstorageunderroom tempera-ture.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgment

ThisworkwassupportedbyNationalCouncilforScientificand Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desen-volvimentoCientíficoeTecnológico–CNPq).

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1. VieiraPA,VieiraRB,deFranc¸aFP,CardosoVL.Biodegradation ofeffluentcontaminatedwithdieselfuelandgasoline.J HazardMater.2007;140:52–59.

2. MeloJuniorHR,CostiACZ.Avaliac¸ãodacontaminac¸ãodas

águassubterrâneasporhidrocarbonetosprovenientesdepostode

abastecimentodecombustívelnaVilaTupi,PortoVelho(RO);2004,

19p.Availableat:http://www.cprm.gov.br/publique/ media/avalicontami.pdf[accessedSeptember2009]. 3. LiuFF,PengC,NgJC.BTEXinvitroexposuretoolusing

humanlungcells:tripsandgains.Chemosphere. 2015;128:321–326.

4. TohonHG,FayomiB,ValckeM,CoppietersY,BoulandC. BTEXairconcentrationsandself-reportedcommonhealth problemsingasolinesellersfromCotonou,Benin.IntJ EnvironHealthRes.2015;25:149–161.

5. CorseuilHX,AlvarezJR,AiresPJJ.Implicationsofthe presenceofethanolonintrinsicbioremediationofBTEX plumesinBrazil.HazardWasteHazard.1996;13:213–221.

6. CorseuilHX,MartinsMDM.Contaminac¸ãodeÁguas SubterrâneasporDerramamentosdeGasolina:OProblemaé Grave?EngenhariaSanitáriaeAmbiental.vol.2,No.2;1997.

7. CorseuilHX,FernandesM.Co-SolvencyEffectinAquifers ContaminatedWithEthanol-AmendedGasoline.Florianópolis,

SC,Brasil:Dep.EngenhariaSanitáriaeAmbiental, UniversidadeFederaldeSantaCatarina;1999.

8.LiG,HuangW,LernerDN,ZhangX.Enrichmentofdegrading microbesandbioremediationofpetrochemical

contaminantsinpollutedoil.WaterRes.2000;34:3845–3853.

9.BaptistaSJ,CammarotaMC,FreireDDC.ProductionofCO2in

crudeoilbioremediationinclaysoil.BrazArchBiolTechnol. 2005;48:249–255.

10.ChenM,XuP,ZengG,YangC,HuangD,ZhangJ. Bioremediationofsoilscontaminateswithpolycyclic aromatichydrocarbons,petroleum,pesticides, chlorophenolsandheavymetalsbycomposting:

applications,microbes,microbesandfutureresearchneeds.

BiotechnolAdv.2015;33:745–755.

11.VidaliM.Bioremediation.Anoverview.PureApplChem. 2001;73:1163–1172.

12.ElFantroussiS,AgathosSN.Isbioaugmentationafeasible strategyforpollutantremovalandsiteremediation?Curr OpinMicrobiol.2005;8:268–275.

13.Al-SalehE,AkbarA.OccurrenceofPseudomonasaeruginosain Kuwaitsoil.Chemosphere.2015;120:100–107.

14.GogoiBK,DuttaNN,GoswamiP,MohanTRK.Acasestudyof bioremediationofpetroleum-hydrocarboncontaminated soilatacrudeoilspillsite.AdvEnvironRes.2003;7:767–782.

15.MarianoAP,KataokaAPAG,AngelisDF,BonottoDM. Laboratorystudyonthebioremediationofdieseloil contaminatedsoilfromapetrolstation.BrazJMicrobiol. 2007;38:346–353.

16.AndreolliM,LampisS,BrignoliP,ValliniG.Bioaugmentation andbiostimulationasstrategiesforthebioremediationofa burnedwoodlandsoilcontaminatedbytoxichydrocarbons: acomparativestudy.JEnvironManage.2015;153:

121–131.

17.BentoFM,CamargoFAO,OkekeB,Frankenberger-JúniorWT. Bioremediationofsoilcontaminatedbydieseloil.BrazJ Microbiol.2003;34:65–68.

18.ShutterME,DickRP.Comparisonoffattyacidmethylester (FAME)methodsforcharacterizingmicrobialcommunities.

SoilSciSocAmJ.2000;64:1659–1668.

19.KatoK,MiuraN.Effectofmaturedcompostasabulkingand inoculatingagentonthemicrobialcommunityandmaturity ofcattlemanurecompost.BioresourTechnol.

2008;99:3372–3380.

20.KlamerM,BaathE.Microbialcommunitydynamicsduring compostingofstrawmaterialstudiedusingphospholipid fattyacidanalysis.FEMSMicrobiolEcol.1998;27:9–20.

21.StegerK,EklindY,OlssonJ,SundhI.Microbialcommunity growthandutilizationofcarbonconstituentsduring thermophiliccompostingatdifferentoxygenlevels.Microb Ecol.2005;50:163–171.

22.StegerK,JarvisA,VasaraT,RomantschukM,SundhI.Effects ofdifferingtemperaturemanagementondevelopmentof Actinobacteriapopulationsduringcomposting.ResMicrobiol. 2007;158:617–624.

23.SanniGO,CoulonF,McGenityTJ.Dynamicsanddistribution ofbacterialandarchaealcommunitiesinoil-contaminated temperatecoastalmudflatmesocosms.EnvironSciPollutRes. 2015;22:15230–15247.

24.HollenderJ,AlthoffK,MundtM,DottW.Assessingthe microbialactivityofsoilsamples,itsnutrientlimitationand toxiceffectsofcontaminantsusingasimplerespirationtest.

Chemosphere.2003;53:269–275.

25.LabudV,GarciaC,HernandezT.Effectofhydrocarbon pollutiononthemicrobialpropertiesofasandyandaclay soil.Chemosphere.2007;66:1863–1871.

26.IskenS,BontJAM.Activeeffluxoftolueneina

solvent-resistantbacterium.JBacteriol.1996;178:6056–6058.

27.IskenS,BontJAM.Bacteriatoleranttoorganicsolvents.

28.RamosJL,DuqueE,GallegosMT,etal.Mechanismsof solventtoleranceinGram-negativebacteria.AnnuRev Microbiol.2002;56:743–768.

29.DuldhardtI,NijenhuisI,SchauerF,HeipieperHJ. AnaerobicallygrownThaueraaromatica,Desulfococcus multivorans,Geobactersulfurreducensaremoresensitive towardsorganicsolventsthanaerobicbacteria.ApplMicrobiol Biotechnol.2007;77:705–771.

30.UdaondoZ,MolinaL,DanielsC,etal.Metabolicpotentialof theorganic-solventtolerantPseudomonasputidaDOT-T1E deducedfromitsannotatedgenome.MicrobBiotechnol. 2013;6:598–611.

31.OliverJD.Theviablebunonculturablestateinbacteria.J Microbiol.2005;43:93–100.

32.SerpaggiV,RemizeF,RecorbetG,Gaudot-DumasE, Sequeira-LeGrandA,AlexandreH.Characterizationofthe viablebutnonculturable(VBNC)stateinthewinespoilage yeastBrettanomyces.FoodMicrobiol.2012;30:438–447.

33.SuX,DingL,ShenC.Potentialofviablebutnon-culturable bacteriainpolychlorinatedbiphenylsdegradation–areview.

ActaMicrobiolSinica.2013;53:908–914.

34.SuX,ZhangQ,HuJ,HashmiMZ,DingL,ShenC.Enhanced degradationofbiphenylfromPCB-contaminatedsediments: theimpactofextracellularorganicmatterfromMicrococcus luteus.ApplMicrobiolBiotechnol.2014;99:1989–2000.

35.SuXM,LiuYD,HasmiMZ,DingLX,ShenCF. Culture-dependentandculture-independent characterizationofpotentiallyfunctional

biphenyl-degradingbacterialcommunityinresponseto extracellularorganicmatterfromMicrococcusluteus.Microb Biotechnol.2015;8:569–578.

36.TanabeS.PBDEs,anemerginggroupofpersistentpollutants.

MarPollutBull.2004;49:369–370.

37.ZhangDC,MortelmaierC,MargesinR.Characterizationof thebacterialarchaealdiversityin

hydrocarbon-contaminatedsoil.SciTotalEnviron. 2012;421–422:184–196.

38.StefaniFOP,BellTH,MarchardC,etal.Culture-dependent and-independentmethodscapturedifferentmicrobial communityfractionsinhydrocarbon-contaminatedsoils. PLoSONE.2015,http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/

journal.pone.0128272.

39.IsaacP,MartínezFL,BourguignonN,SánchezLA,FerreroMA. ImprovedPAHsremovalperformancebyadefinedbacterial consortiumofindigenousPseudomonasandactinobacteria fromPatagonia,Argentina.IntBiodeterBiodegr.

2015;101:23–31.

40.CébronA,NoriniMP,BeguiristainT,LeyvalC.Real-timePCR quantificationofPAH-ringhydroxylatingdioxygenase (PAH-RHD␣)genesfromGrampositiveandGramnegative

bacteriainsoilandsedimentsamples.JMicrobiolMethods. 2008;73:148–159.

41.SawulskiP,BootsB,ClipsonN,DoyleE.Differential

degradationofpolycyclicaromatichydrocarbonmixturesby indigenousmicrobialassemblagesinsoil.LettApplMicrobiol. 2015;61:199–207.

42.SchimelJP,BalserTC,WallensteinM.Microbialstress responsephysiologyanditsimplicationsforecosystem function.Ecology.2007;88:1386–1394.

43.ManzoniS,SchimelJP,PorporatoA.Physicalvs.physiological controlsonwater-stressresponseinsoilmicrobial