Q U A N T I T A T I V E

Clinical validation of the nursing diagnosis of dysfunctional family

processes related to alcoholism

Suzana de Oliveira Mangueira & Marcos Ven

ıcios de Oliveira Lopes

Accepted for publication 1 April 2016

Correspondence to M.V.O. Lopes: e-mail: marcos@ufc.br

Suzana de Oliveira Mangueira PhD RN Adjunct Professor

Federal University of Pernambuco, Vitoria de Santo Ant~ao, Pernambuco, Brazil

Marcos Venıcios de Oliveira Lopes PhD RN Associate Professor

Nursing Department, Federal University of Ceara, Fortaleza, Brazil

M A N G U E I R A S . O . & L O P E S M . V . O . ( 2 0 1 6 ) Clinical validation of the nursing diagnosis of dysfunctional family processes related to alcoholism. Journal of Advanced Nursing72(10), 2401–2412.doi: 10.1111/jan.12999

Abstract

Aims. To evaluate the clinical validity indicators for the nursing diagnosis of dysfunctional family processes related to alcohol abuse.

Background. Alcoholism is a chronic disease that negatively affects family relationships. Studies on the nursing diagnosis of dysfunctional family processes are scarce in the literature. This diagnosis is currently composed of 115 defining characteristics, hindering their use in practice and highlighting the need for clinical validation.

Design. This was a diagnostic accuracy study.

Methods. A sample of 110 alcoholics admitted to a reference centre for alcohol treatment was assessed during the second half of 2013 for the presence or absence of the defining characteristics of the diagnosis. Operational definitions were created for each defining characteristic based on concept analysis and experts evaluated the content of these definitions. Diagnostic accuracy measures were calculated from latent class models with random effects.

Results/findings. All 89 clinical indicators were found in the sample and a set of 24 clinical indicators was identified as clinically valid for a diagnostic screening for family dysfunction from the report of alcoholics. Main clinical indicators with high specificity included sexual abuse, disturbance in academic performance in children and manipulation. The main indicators that showed high sensitivity values were distress, loss, anxiety, low self-esteem, confusion, embarrassment, insecurity, anger, loneliness, deterioration in family relationships and disturbance in family dynamics.

Conclusion. Eighteen clinical indicators showed a high capacity for diagnostic screening for alcoholics (high sensitivity) and six indicators can be used for confirmatory diagnosis (high specificity).

Introduction

Data from the World Health Organization show that in 2012, approximately 33 million deaths, or 59% of all

global deaths, were attributable to alcohol consumption (World Health Organization 2014). Despite growing attention to the development of interventions to combat the increasing rate of substance use, it is still unclear how families have faced the consequences on the dynam-ics and family functioning as a result of living or caring for a family member abusing substances (Sakiyama et al.

2015).

The lack of consistent data on substance abuse and its impact on a family remains a barrier to the development of intervention strategies (Copello et al.2010). A study in the UK showed that a systemic intervention with families with

alcohol-related problems facilitated a positive change in drinking behaviour and family relationships when com-pared with an individual approach (Flynn 2010).

Alcoholism increases the risk of illness and injury and caregiver burden and affects the family financially and emotionally. Given this reality, family members may use coercive strategies to force the alcoholic to stop drinking, generating an increase in stress and aggravating the con-text of alcohol abuse; thus, the consequences of alco-holism extend to other family members leading to dysfunctional family relationships. In this context, profes-sional interventions should include the alcoholic and their family, aimed at improving family relationships, reducing stress and decreasing the alcoholic addiction (Scherer et al.

2012).

The identification in previous studies of family dysfunc-tion related to alcoholism and the clinical importance of early diagnosis justified the inclusion of the diagnosis of a Dysfunctional family process in the NANDA International, Inc. (NANDA-I) taxonomy (Bartek et al. 1999, Mohr 2000, Kim & Rose 2014). Although this diagnosis was included in the NANDA-I taxonomy in the 1990s, their study in clinical settings remains incipient. In addition, the clinical assessment of the alcoholic is the first stage of clini-cal judgment to establish this diagnosis and this task can best be accomplished if, when evaluating the patient, the nurse uses questions directed to family relationships (Wright & Leahey 2013). Clinical indicators identified in this assessment should provide the basis for diagnostic screening and highlight the need for deeper diagnostic investigation with other family members.

Background

Determination of clinical indicators accurately representing a specific phenomenon allows for making a quick and effi-cient decision, reducing costs and maximizing health out-comes. Because of these possibilities, research on the clinical validation of nursing diagnoses included in the NANDA-I taxonomy have focused on diagnostic accuracy measures of clinical indicators (Lopeset al.2012). Unfortu-nately, much of the developed studies address a restricted set of nursing diagnoses, so that many diagnoses have not been subjected to consistent clinical validation procedures to assess the adequacy of its clinical indicators.

The diagnosis of Dysfunctional family processes (00063) was included in the NANDA-I taxonomy in 1994 and revised in 2008. This diagnosis is currently ranked in the level of evidence 21, indicating that it still needs to be

clin-ically validated. This diagnosis is defined as a chronic

Why is this research needed?

● The evaluation of alcoholic patients is the starting point for diagnostic screening of a dysfunctional family.

● The diagnosis of Dysfunctional family process has a long structure hindering its implementation in practice.

● Clinical validation of a nursing diagnosis identifies essen-tial elements for use in professional practice and delimits the competence field of nursing.

What are the key findings?

● The prevalence of dysfunctional family process has a high prevalence when using clinical indicators validated from interviews with alcoholics.

● Clinical indicators related to feelings of alcoholics have a higher sensitivity for the identification of family dysfunc-tion.

● Confirmatory clinical indicators were associated with behaviour and role performance of alcoholics.

How should the findings be used to influence policy/ practice/research/education?

● Validated clinical indicators can be used for the clinical judgment, screening and decision-making for a deeper investigation of potential dysfunctional families.

● A clinical evaluation of the dysfunctional family dynamics from the alcoholic’s perspective allows one to adopt edu-cational and therapeutic strategies that generate beha-vioural changes that focus on the patient.

disorganization of psychosocial, spiritual and physiological functions of the family, which leads to conflict, denial of problems, resistance to change, ineffective problem-solving and self-perpetuating crises. It is inserted in the domain ‘Role Relationships’, class ‘Family Relationships’ and cur-rently has eight possible aetiological factors (related factors) and 115 clinical indicators (defining characteristics), dis-tributed among behavioural (54), roles and relationships (22) and feelings (39) (Herdman & Kamitsuru 2015).

The studies of Lindman et al. (1994) and Bartek et al.

(1999) motivated the current structure of the diagnosis with a high number of defining characteristics, but research on this diagnosis has remained scarce ever since. These studies used the Fehring’s diagnostic validation model, which tends to present weighted averages that overestimate the validity of each characteristic (Lopes et al. 2015). Thus, the accu-racy of each clinical indicator of this diagnosis remains inconclusive.

Among its aetiological factors, substance abuse, espe-cially alcohol abuse, has often been associated with family dysfunction in previous studies (Keenan et al. 1998, Tsai

et al. 2010). Alcohol abuse is a global problem that stands out because it affects all members of the family, which is characterized by physical and emotional conflicts that deteriorate relationships and lead to negative out-comes such as loss of child custody, unemployment, mari-tal separation, physical and psychological abuse, depression, car or household accidents and crimes (Sh€afer 2011).

Although there is some consensus among researchers on the issue of family dysfunction caused by alcoholism, the current structure of this diagnosis described in the NANDA-I taxonomy includes an excessive number of clini-cal indicators, hampering its use by clinicians, as clinicians can be unaware of the importance of each indicator to characterize the diagnosis and its ability to serve as a diag-nostic screen or confirmation.

Researchers have advocated the need to improve the preparation of nurses for developing the skills to meet the challenges raised by substance abuse in practice scenarios (Nkowane & Saxena 2004, Kennedyet al.2013). Although family dysfunction influenced by alcohol abuse represents a diagnosis focused on the family group, the diagnostic evalu-ation usually starts with the alcoholic. The clinical indica-tors described in the NANDA-I taxonomy for this diagnosis refer to the clinical signs that can be obtained in clinical interview, even if they are based on the standpoint of the alcoholic. This information can provide essential diagnostic clues to the early identification of families that need moni-toring and immediate interventions to prevent more serious

abuse and outcomes and allows for identification of warn-ing signs of violent, destructive and self-destructive beha-viours.

The study

Aim

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical validity of the defining characteristics of the nursing diagnosis of dysfunctional family processes related to alcohol abuse.

Design

A diagnostic accuracy study of clinical indicators of dys-functional family processes was developed in a mental health institution located in the state of Pernambuco (north-eastern Brazil) that follows patients with alcoholic dependence syndrome who are part of a free therapeutic intervention programme. Most of the participants in this programme are men who are low income and whose ages range from 19-65 years. The hospital stay lasts an average of thirty days and can be extended up to ninety days. After being discharged from the hospital, the patient is referred to an outpatient clinic for continued treatment. In north-eastern Brazil, the consumption of alcoholic beverages is high, especially among young adults with low income sta-tus. Cachacßa is the main beverage consumed. It is a distilled beverage with high alcohol content (38-56%) that is sold at a low price.

Sample

The study included all registered patients who had a medi-cal diagnosis of alcohol dependence syndrome over the age of 18 years, were clinically stable in medical records and were hospitalized in the institution during the second half of 2013. The final sample consisted of 110 alcoholics picked up by consecutive sampling. Patients were excluded if they had disorientation, altered level of consciousness or were alcoholised at the time of data collection.

Data collection

analysis with subsequent content validation by evaluators with expertise on the subject.

The concept analysis was developed based on the model of Walker and Avant (2011) and the search for references was conducted following six steps of the integrative review:

1)Identification of the theme based on three questions: What is the definition of ‘dysfunctional family processes’ in the literature? What characteristics define a dysfunc-tional family? How can these characteristics be mea-sured?

2)Establishment of criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies/samples as well as a literature search. The search was performed in three databases (Scopus, Medline and CINAHL) using the controlled descriptor ‘alcoholism’ and the uncontrolled descriptor ‘dysfunctional family’ with the Boolean operator AND. Articles should be pub-lished in Portuguese, English, or Spanish and be available electronically. Editorials and letters to the editor were excluded. Initially, 184 articles (Scopus = 95, PubMed = 74, CINAHL = 15) were identified, of which 33 were repeat articles, 10 were letters to the editor or editorials, 12 written in a language other than English, Portuguese or Spanish, 87 did not respond to research questions and 29 were not available electronically. Thus, 12 articles were initially used in the study.

3)Definition of information to be extracted from the selected studies and categorization of the studies. A form was used to collect data regarding the title, authors, country, year of publication, objectives, level of evidence, area, subject, setting, theme and data regarding the three research questions. The level of evidence was rated based on the guide published by Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt (2010), which describes seven levels of evidence. In this review, most of the articles were published by American authors (7273%), published between the years 2000–

2005 (4546%) and the level of evidence was rated as IV

(8182%).

4)Data analysis. At this stage, we identified two clinical indicators that were not listed among the defining char-acteristics of the NANDA-I (physical abuse in 9 articles and sexual abuse in 3 articles). Physical abuse, which was defined in articles as the use of physical force by alcoholics that causes harm (hitting, beating) to a family member, was a feature that was present in dysfunctional families. Sexual abuse was defined as the forced partici-pation in fondling or sexual acts of a family member by the alcoholic. This analysis also has eliminated 26 defin-ing characteristics because they have similar meandefin-ings or did not fit the study population (adult alcoholics). Thus,

of the 115 defining characteristics contained in the NANDA-I, the remaining 89 along with two other clini-cal indicators composed a list of 91 variables for which conceptual and operational definitions were built from articles and textbooks.

5) Interpretation of the results. The main results included the identification of clinical indicators of a ‘dysfunctional family’ where alcohol abuse was the cause. Conceptual and operational definitions were built and interpreted from scientific articles in the areas of nursing, psychology and medicine, and textbooks on clinical nursing, semiol-ogy, psychiatric nursing, psycholsemiol-ogy, psychiatry and technical dictionaries of health.

6) Synthesis of knowledge. This step includes a description of the elements included in the concept analysis model. After the previous stage, the clinical indicators were sub-mitted to a group of 23 evaluators with experience in nurs-ing diagnosis and/or care to patients with alcoholic dependence syndrome. These evaluators were initially iden-tified by the online curriculum available in lattes platform (national base of curriculum used primarily for fomentation of research and education in Brazil), followed by snowball sampling. The curriculum of the evaluators was examined to verify their professional experience (clinical and/or teach-ing experience), publications and participation in studies or research groups on the subject. The evaluators analysed the importance of each indicator for the characterization of a dysfunctional family process, and the adequacy of opera-tional definitions for establishing the diagnosis. These defi-nitions were based on information that could be obtained directly from the patient. Binomial tests were applied to check whether the proportion of evaluators who considered the indicator to be relevant and its definition as proper was equal to or above 85%. At this stage, two clinical indica-tors were excluded due to low relevance by evaluaindica-tors, leaving 89 indicators that have been submitted for clinical validation.

A total of 162 patients was admitted to the centre during the period of clinical validation. Of these, 52 were excluded due to a factor described in the exclusion criteria. There were no refusals or dropouts among patients who fulfilled the study criteria; thus, we obtained a survey response rate of 100%.

Ethical considerations

the institutional review board (no. 10151112700005208).

Confidentiality of medical information and patients’ identi-ties was guaranteed.

Data analysis

Data were consolidated into a spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel and analysed with the support of statistical package R version 320 (R Core Team, 2014) using the

ran-domLCA packages (Beath 2015) and PoLCA (Linzer & Lewis 2011). The descriptive analysis included the calcula-tion of absolute frequencies, percentages, measures of cen-tral tendency and dispersion. The Lilliefors test was used to verify adherence to the normal distribution of quantitative variables. Confidence intervals were calculated for propor-tions based on chi-square asymptotic distribupropor-tions along with Yates correction when applicable.

Sensitivity and specificity with the respective 95% confi-dence intervals (using parametric bootstrapping) for each clinical indicator were calculated based on latent class anal-ysis (LCA) with random effects (Quet al.1996). This tech-nique is used to calculate the diagnostic accuracy measures of clinical indicators when there is no perfect gold standard, based on the assumption that a non-observed or latent vari-able (nursing diagnosis) determines the associations among the observable variables (clinical indicators). A model based on random effects was chosen because of the conditional dependence assumption among clinical indicators of the diagnosis under review. The likelihood ratio test (G2) was used to verify the goodness of fit of the models.

Values of sensitivity and specificity≤05 denote low

diag-nostic accuracy of a clinical indicator. An initial model of latent class with all of the indicators was initially set and denominated as ‘model null’. From this model, clinical indi-cators were sequentially excluded if their 95% confidence intervals included the value of 05 or were below this value.

After these exclusions, all of the clinical indicators that simultaneously showed sensitivity and specificity values lower than 06 were excluded and a new latent class model

was constructed and evaluated for quality of their adjust-ment. Then, the proceedings were similar with indicators with diagnostic accuracy measures less than 065 (i.e.

decre-ment factor of 005 relative to the first group). This strategy

was used until values lower than 085 when the decrement

factor was reduced to 001 through the final model

pre-sented goodness of fit (not significant G2test).

Latent class analysis requires relatively large samples to obtain convergence of the models, especially if there are numerous indicators included (Swanson et al. 2012). Because of this limitation, we decided to adjust four latent

class models using the previously described strategy: a model adjusted from all clinical indicators and three other models based on subgroups of clinical indicators described in the NANDA-I taxonomy for diagnosis of Dysfunctional family processes (Behavioural, Roles and relationships and Feelings). We adopted the significance level of 5% for all analyses.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

The majority of the sample was male, had a mean age of 4398 years (SD 1078), with up to 8 years of schooling,

were catholic and had a monthly family income of less than U.S.$ 40000. On average, patients were admitted for

1005 days (SD 973), had approximately three previous

hospitalizations (mean 275 SD 388), with a mean time

from the first admission of 313 years (SD477) and 627%

had a family history of alcoholism. Out of the total, 645%

reported absenteeism from work because of drinking and 461% had comorbidities such as diabetes, high blood

pres-sure, liver disease, heart disease or neurological problems. Most drank an alcoholic beverage on a daily basis and approximately 20% consumed other substances such as 70% alcohol (sold in pharmacies), ethanol (car fuel), or perfumes or cleaners containing alcohol in their composi-tion (Table 1).

Diagnostic accuracy of clinical indicators

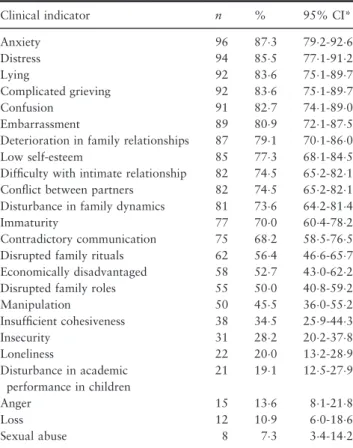

A total of 24 indicators had clinical validity according to diagnostic accuracy measures obtained from the four set models based on latent class analysis. Most of these indica-tors were observed in more than half of the sample (16) and among the eight with a lower frequency, four stood out by presenting a higher sensitivity than specificity (Inse-curity, Loneliness, Anger and Loss) (Table 2).

The latent class model that initially included all clinical indicators only provided a good fit with the inclusion of eight clinical indicators (P=0542). The report of having

suffered sexual abuse had a higher specificity value (09404;

95% CI 0750-1000), while the others showed greater

sen-sitivity. The area under the ROC curve of these indicators ranged from 05019 (sexual abuse)-08181

(Embarrass-ment). The prevalence of diagnosis was estimated at 8427% when considering these eight indicators as a basis

for a diagnostic inference process (Table 3).

Disturbance in academic performance in children and Manipulation), while other indicators showed high values of sensitivity. Because of the identification of an increased number of indicators with greater specificity, the estimated prevalence of nursing diagnosis was lower than that obtained with the adjusted model from all indicators (6344%). Another highlight is the inclusion of six different

clinical indicators from those identified in the first model. Only seven clinical indicators of the Roles and relation-ships subset showed a good fit in the latent class model. Of these indicators, Disrupted family roles, Economically dis-advantaged and Disrupted family rituals showed high val-ues for sensitivity and specificity (confidence interval above 05). Insufficient cohesiveness showed significant values only

for specificity, while the other showed only significant val-ues for sensitivity. The smaller number of clinical indicators included in the model, together with the fact that half of them have higher values for specificity, may explain the lower estimated prevalence of diagnosis (6103%)

compared with previous models.

In the latent class model subset of Feelings, seven clinical indicators showed high values for sensitivity (above 089).

Only the indicator of Low self-esteem showed significant specificity. This subset has led to an estimated prevalence of dysfunctional family processes of 687%, the highest among

the three subsets of clinical indicators but less than the esti-mate produced by the latent class model adjusted from the full set of indicators.

Discussion

Behavioural clinical indicators

In this study, sexual abuse showed higher specificity for the diagnosis of dysfunctional family processes. Although the

Table 1 Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

Variables n % 95% CI*

1. Gender (Male) 104 945 880-977

2. Marital status

Single 42 382 292-479

Married 29 264 186-358

Divorced 37 336 251-433

Widower 2 18 31-70

3. Occupational status

Unemployed 31 282 202-378

Employed 67 609 511-699

Retired 12 109 60-186

4. Consumption frequency of alcoholic beverages

All days 80 727 632-805

Between 4-6 days/week 7 64 28-131

Three or more days/week 23 209 139-299 5. Type of beverage consumed

Sugar cane brandy 90 818 731-883

Other distilled beverage 16 145 88-228

Beer 4 36 11-95

6. Use of other substances with alcoholic beverages

21 191 125-279

7. Work absenteeism 71 645 548-732

8. Comorbidities 51 464 369-561

9. History of alcoholism 69 627 529-716

Mean SD Median IQR Pvalue†

10. Age 4398 1078 4400 13 0029

11. Length of stay 1005 973 700 13 <0001 12. Time to drink

alcoholic beverages

2704 1057 2850 16 0184

13. Number of admissions

275 388 200 2 <0001

14. Time since first admission

313 477 100 5 <0001

*Confidence interval based on chi-square asymptotic distribution with Yates correction when applicable.

†Lilliefors’test.

Table 2 Clinical indicators included in the latent class analysis models.

Clinical indicator n % 95% CI*

Anxiety 96 873 792-926

Distress 94 855 771-912

Lying 92 836 751-897

Complicated grieving 92 836 751-897

Confusion 91 827 741-890

Embarrassment 89 809 721-875

Deterioration in family relationships 87 791 701-860

Low self-esteem 85 773 681-845

Difficulty with intimate relationship 82 745 652-821 Conflict between partners 82 745 652-821 Disturbance in family dynamics 81 736 642-814

Immaturity 77 700 604-782

Contradictory communication 75 682 585-765 Disrupted family rituals 62 564 466-657 Economically disadvantaged 58 527 430-622

Disrupted family roles 55 500 408-592

Manipulation 50 455 360-552

Insufficient cohesiveness 38 345 259-443

Insecurity 31 282 202-378

Loneliness 22 200 132-289

Disturbance in academic performance in children

21 191 125-279

Anger 15 136 81-218

Loss 12 109 60-186

Sexual abuse 8 73 34-142

occurrence of sexual abuse is under-reported, studies show that this behaviour is linked to alcohol consumption. A study developed with a community sample of New Zealand women identified an increased risk of abuse perpetrated by a family member when there was an alcoholic father and a higher risk of abuse perpetrated by an external member to the family when there was an alcoholic mother (Fleming

et al. 1997). Similarly, another New Zealand study found an increased risk of childhood sexual abuse among those with parents who reported alcoholism/alcohol problems (P<005) (Fergusson et al.1996). In addition, the beating

of wives, incestuous acts and child abuse have been linked

with alcohol consumption by the perpetrator (Silva & Padilha 2013).

Another indicator of high specificity was manipulative behaviour. Authors report that alcoholics recognize the increase in their manipulative behaviour when in abstinence and that this results in the loss of confidence by many peo-ple who live with them (Chaves et al. 2011). The final behavioural indicator of high specificity refers to the report of compromising the ability of children to achieve the stan-dards set by school (disturbance in academic performance in children). This result is consistent with previous studies that show that children of alcoholics are at increased risk

Table 3 Sensitivity (Se) and Specificity (Sp) of clinical indicators for Dysfunctional family processes estimated by latent class analysis.

Se 95% CI Sp 95% CI*

Model from all indicators

Sexual abuse 00733 00223-01327 09304 07500-10000

Lying 08801 07998-09461 03980 01163-06881

Distress 09387 08785-09973 05963 03130-09999

Anxiety 09631 09127-10000 06114 03107-10000

Confusion 09198 08535-09834 06684 03753-10000

Embarrassment 09092 08351-09762 07271 04518-10000

Loss 09185 08621-09736 02571 00000-05395

Anger 09186 08512-09746 04308 01692-07547

G2=9089; d.f.=93;P=0542 Prevalence: 8427% (95% CI 7581-9026%)

Model from behavioural indicators

Sexual abuse 00396 00000-01043 08698 07109-09782

Contradictory communication 07961 06699-09309 05165 03242-07658

Difficulty with intimate relationship 08584 07526-09666 04506 02618-06891

Disturbance in academic performance in children 02487 01364-03770 09094 07729-10000

Immaturity 09250 07966-10000 06903 04568-10000

Manipulation 06394 04937-08282 08662 06953-10000

Lying 09244 08345-10000 03164 01621-05299

Complicated grieving 09195 08233-10000 03079 01394-05322

G2=114

82; d.f.=93;P=0062 Prevalence: 6344% (95% CI 5367-7226%) Model from role and relationship indicators

Deterioration in family relationships 09327 08476-10000 04312 02656-06161

Disturbance in family dynamics 10000 09282-10000 06766 04565-09575

Insufficient cohesiveness 04069 02821-05366 07508 05848-09000

Disrupted family roles 06470 05159-07694 07303 05788-08974

Conflict between partners 07947 06832-09102 03317 01761-05010

Economically disadvantaged 07159 05862-08527 07682 06090-09394

Disrupted family rituals 07693 06290-09099 07585 06090-09425

G2=104

58; d.f.=95;P=0235 Prevalence: 6103% (95% CI 5123-7004%) Model from feeling indicators

Anxiety 09840 09398-10000 03714 02165-05583

Low self-esteem 09858 09304-10000 06949 05132-09129

Confusion 09701 09170-10000 04862 03162-06922

Embarrassment 09368 08717-09909 04711 03011-06735

Insecurity 08951 08007-09696 06701 04974-08566

Anger 09582 09045-10000 03438 01925-05210

Loneliness 09063 08273-09732 04332 02618-06299

G2=82

78; d.f.=95;P=0810 Prevalence: 6870% (95% CI 5906-7702%)

for school problems, conduct disorders and internal emo-tional conflicts, whose most extreme consequences include destructive patterns of social behaviour, non-compliance with rules and ethical values of distortions (McCrady 2012, Kurzeja 2014).

Lying was the third most frequent clinical indicator in alcoholics. Authors argue that alcoholism generates a series of destructive discharges because of a relationship perme-ated by lies and uncertainty, which may lead to family destabilization (Silva et al.2011). This indicator should be seen as a warning sign to generate family conflict, including the denial of the use of alcohol. In addition to the previous indicator, four others showed high sensitivity to the dys-functionality of family processes and included Contradic-tory communication, Difficulty with intimate relationships, Immaturity and Complicated grieving.

Previous research has shown a link between alcoholism and negative family communication as less positive affirma-tions, lower expression of feelings and coercion and punish-ment of communication attempts by children on issues that generate conflict (Rangarajan & Kelly 2006 Walitzer et al.

2013). In addition, communication problems generate fragi-lity of affective bonds due to constant bickering and loss of respect from family and society, culminating with the diffi-culty to establish intimate relationships (Kochet al. 2011). These conflicts can also be enhanced by the immature beha-viour frequently identified among alcoholics (Milivojevic

et al.2012).

The high sensitivity of Complicated grieving is a finding supported by a previous study that found that grief had greater emotional damage in alcoholics (Esper et al.2013). In contrast, another study found the grief to not be a clini-cal indicator but a predisposing factor for the use of alco-hol, given that alcoholics understood its consumption as a source of pleasure, disinhibition, relaxation and relief from feelings of anger, fear or sadness (Marques & M^angia 2013).

Roles and relationships clinical indicators

The indicator Disrupted family roles was one of three clini-cal indicators with higher diagnostic efficiency among indi-cators of the Roles and relationships group. The literature emphasizes that among the damage caused by alcoholism, the dependent ceases to fulfil their role in the home and that his wife assumes the post of householder, accumulating other roles such as housewife, mother and wife, with the overload of tasks, stress and wear on family relationships (Alchieriet al.2013). In addition, the inversion of roles can also affect the children in a functional (e.g. the child takes

care of the siblings, performs household chores, saves money) or emotional ways (when the child acts like a friend of the parents, acts as a mediator of marital conflicts, sup-ports the siblings, protects the mother from aggression) (Pasternak & Scheir 2012).

Disruption of roles may extend to the workplace, causing difficulties related to funding or administration of financial resources for the family, which are insufficient to meet demand (Economically disadvantaged). This clinical indica-tor is directly related to behavioural changes feeding back to problems in the family (Carvalho & Menandro 2012). Alcoholics spend their material resources without control to satisfy their addiction, causing a frequent drunken state cul-minating in absenteeism at work and subsequent unemploy-ment (Silva et al. 2011). The high diagnostic efficiency of this indicator is consistent with the results of a study car-ried out to evaluate the financial burden related to alco-holism supported by caregivers and family members. The results showed that after the start of alcoholism treatment, there was a significant reduction in spending on family and time spent by the caregiver, and an increase in their quality of life (Salizeet al.2012).

Another clinical indicator with high diagnostic efficiency was Disrupted family rituals. The authors note that the loss of celebrations and routines generates negative conse-quences for the children because they tend to perpetuate behaviours experienced within the family (Silva et al.

2014). Furthermore, the indicator Lack of cohesion was characterized as a confirmatory indicator (high specificity) of the studied diagnosis. This indicator is related to the quality of communication and relationships observed in alcoholics’ families. A previous study has shown that alco-holics and their families realize the lack of cohesion as one of the main problems they face (Noy 2014).

Among indicators that show a high sensitivity to family dysfunction, the Deterioration in family relationships and the Disturbance in family dynamics refer to alcoholic atti-tudes that imply the loss of mutual respect in the domestic and social sphere (Silva et al. 2011). In this context, the indicator Conflict between partners seems to become evi-dent. Divorce and separation rates are about four times higher in couples where one partner has alcohol-related problems compared with the general population and physi-cal violence is common in approximately two-thirds of these couples (McCrady 2012). In addition, marital satisfac-tion and self-esteem are lower among couples with an alco-holic husband when compared with couples with two healthy members, exhibiting less consistency in the assess-ment of feelings and the emotional state of spouses (Dethier

Feeling clinical indicators

Six of the eight indicators that composed the latent class model based on all of the indicators are classified as feel-ings. This dominance may be related to the validation strat-egy based on an alcoholic vision of a family diagnosis. In this context, feelings of anxiety, confusion, embarrassment and anger were shown to be suitable for the identification of a dysfunctional family process in the analysis that came from the set of all clinical indicators, such as the analysis that includes only the set of indicators related to feelings.

The proportion of patients identified in this study who reported anxiety was higher than that found in the Esper

et al.(2013) study where only 167% of alcoholic females

were classified as anxious. Moreover, previous studies con-firmed the association between anxiety and alcoholism, and the tendency of the early developing anxiety to create a vicious cycle (Cludiuset al.2013, Paceket al.2013).

Although classified as a clinical indicator related to feel-ings, confusion is described as a major cognitive impair-ment that affects the ability to solve problems and make decisions (Rigoni et al. 2013). The embarrassment is another feeling that leads the individual to social isolation and between family members, there is a fear that the depen-dent may cause vexatious scenes and thereby embarrasses the family in social activities (Kochet al.2011, Silvaet al.

2011). In addition, even if identified at a low frequency, the expression of fury or loss of control by alcoholics (Anger) has been related to the relief of suffering allowing discus-sion of this experience with the family (Silvaet al.2011).

Distress and Loss showed high sensitivity only in the glo-bal latent class model. This result is similar to that found in previous studies that identified the presence of feelings of distress, fear and hopelessness among family members of alcoholics (Kochet al.2011, Silvaet al.2011). Three other indicators show high diagnostic accuracy measures only in the model including indicators classified as feelings: Low self-esteem, Insecurity and Loneliness. Low self-esteem showed higher frequency than that described by Esperet al.

(2013), who found a report of feeling worthlessness in 83% of alcoholic women. The authors of that study used

data records of women with disorders related to alcohol, while in this study, men were the majority of the study sample. On the other hand, the authors claim that the alco-holic’s view of himself reveals just negative feelings, such as losses, vulnerabilities, failure and frustration, representing aspects directly associated with low self-esteem (Vargas & Soares 2013).

Although reported by alcoholics, Insecurity and Loneli-ness are also feelings experienced by the family. Silvaet al.

(2011) found that women married to alcoholics feel anx-ious, insecure and unmotivated regarding the behaviour of their spouse. Finally, the alcohol seems to lead to family separation and in this context, the feeling of loneliness ulti-mately stimulated the search for alcohol as a means of escaping from reality, creating a sort of vicious cycle (Sen-geret al.2011).

Limitations

The sample size used in this study is lower than recom-mended for a latent class analysis. The use of this technique for such a large number of indicators led to the need for construction of four latent class models to find a larger number of clinical indicators that adequately represented the dysfunctional family processes among alcoholics. The fact that the study was conducted in one centre in Brazil is another limitation to consider. However, the clinical and demographic characteristics identified in our sample were similar to alcoholics in other developing countries. Further-more, the clinical indicators validated in our study are fre-quently described as important signs of dysfunctional families by researchers of developed countries. In addition, the fact that the study was conducted only with alcoholics who were predominantly male, admitted to a hospital insti-tution and had no confirmatory family data should be taken into consideration when attempting to extrapolate the results, suggesting the development of studies with larger samples and other scenarios to compare the findings with those presented here.

Conclusion

included anxiety, low self-esteem, confusion, embarrass-ment, insecurity, anger and loneliness.

The most validated indicators showed high values of sen-sitivity, which demonstrates their utility for screening. In this group we highlight the indicators related to feelings including distress, loss, anxiety, low self-esteem, confusion, embarrassment, insecurity, anger and loneliness. In addi-tion, two other indicators associated with roles and family relationships (deterioration in family relationships and dis-turbance in family dynamics) reported by alcoholics showed high sensitivity. Clinicians may initially seek to identify these feelings and changes of roles among alcoholics early on and then identify confirmatory indicators (high speci-ficity) to establish the diagnosis of dysfunctional family roles. In this case, the study highlighted three clinical indi-cators with specificity values above 80%, all of which were classified as behavioural indicators (sexual abuse, distur-bance in academic performance in children and manipula-tion). It is noteworthy that confirmatory indicators are related to a sharp deterioration of family dynamics, includ-ing the reportinclud-ing of abuse and manipulation. Thus, the identification of these behaviours must be succeeded by immediate intervention.

Funding

This research was funding by Coordenacß~ao de Aperfeicß oa-mento de Pessoal de Nıvel Superior–CAPES/Brazil.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest has been declared by the author(s).

Author contributions

All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria [recommended by the ICMJE (http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/)]:

•

substantial contributions to conception and design, acqui-sition of data or analysis and interpretation of data;•

drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.References

Alchieri C.C., Arboit E.L., Hildebrandt L.M., Ubessi L.D., Leite M.T. & Piovesan S.M.S. (2013) Percepcß~oes de alcoolistas residentes no meio rural sobre o alcoolismo: suas causas e consequ^encias.Revista de enfermagem9(9), 14–29.

Bartek J.K., Lindeman M. & Hawks J.H. (1999) Clinical validation of characteristics of the alcoholic family. Nursing Diagnosis10(4), 158–168.

Beath K. (2015) RandomLCA: Random Effects Latent Class Analysis. R package version 1.0-2. Retrieved from http:// CRAN.R-project.org/package=randomLCA on 18 November 2015.

Carvalho M.F.A.A. & Menandro P.R.M. (2012) Expectativas manifestadas por esposas de alcoolistas em tratamento no centro de atencß~ao psicossocial alcool e drogas. Brazilian Journal in Health Promotion25(4), 492–500.

Chaves T.V., Sanchez M.Z., Ribeiro L.A. & Nappo S.A. (2011) Crack cocaine craving: behaviors and coping strategies among current and former users. Revista Saude P ublica 45(6), 1168– 1175.

Cludius B., Stevens S., Bantin T., Gerlach A.L. & Hermann C. (2013) The motive to drink due to social anxiety and its relation to hazardous alcohol use.Psychology of Addictive Behaviors27(3), 806–813.

Copello A., Templeton L. & Powell J. (2010) The impact of addiction on the family: estimates of prevalence and costs.

Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy17(S1), 63–74. Dethier M., Counerotte C. & Blairy S. (2011) Marital satisfaction

in couples with an alcoholic husband.Journal of Family Violence 26, 151–162.

Esper L.H., Corradi-Webster C.M., Carvalho A.M.P. & Furtado E.F. (2013) Women in outpatient treatment for alcohol abuse: sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.Revista Gaucha de Enfermagem 34(2), 93–101. doi:10.1590/S1983-14472013000 200012.

Fergusson D., Lynskey M.T. & Horwood L.J. (1996) Childhood Sexual Abuse and Psychiatric Disorder in Young Adulthood: I. Prevalence of sexual abuse and factors associated with sexual abuse.Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry35(10), 1355–1364.

Fleming J., Mullen P. & Bammer G. (1997) A study of potential risk factors for sexual abuse in childhood. Child Abuse and Neglect21(1), 49–58.

Flynn B. (2010) Using systemic reflective practice to treat couples and families with alcohol problems. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing17, 583–593.

Herdman T.H. & Kamitsuru S., eds (2015)NANDA International Nursing Diagnoses: Definitions & Classification 2015–2017. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford.

Keenan C.K., El-Hadad A. & Balian S.A. (1998) Factors associated with domestic violence in low-income lebanese families.Image: the Journal of Nursing Scholarship30(4), 357– 362.

Kennedy A.J., Mellor D., McCabe M.P., Ricciardelli L.A., Brumby S.A., Head A. & Mercer-Grant C. (2013) Training and experience of nurses in responding to alcohol misuse in rural communities.Public Health Nursing30(4), 332–342.

Kim H. & Rose K.M. (2014) Concept analysis of family homeostasis.Journal of Advanced Nursing70(11), 2450–2468. Koch R.F., Manfio D.P., Hildebrandt L.M. & Leite M.T.

Kurzeja A. (2014) An alcoholic family and its harmful effect on children.Current Problems of Psychiatry15(1), 41–45.

Lindman M., Hawks J.H. & Bartek J.K. (1994) The alcoholic family: a nursing diagnosis validation study. Nursing Diagnosis 5(2), 65–72.

Linzer D.A. & Lewis J.B. (2011) poLCA: an R Package for polytomous variable latent class analysis. Journal of Statistical Software42(10), 1–29.

Lopes M.V.O., Silva V.M. & Araujo T.L. (2012) Methods for establishing the accuracy of clinical indicators in predicting nursing diagnoses. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge 23(3), 134–139.

Lopes MVO, Silva VM, Araujo TL & Silva Filho JV (2015) Statistical characteristics of the weighted inter-rater reliability index for clinically validating nursing diagnoses. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge 26(4), 150–155. doi: 10.1111/ 2047-3095.12047.

Marques A.L.M. & M^angia E.F. (2013) Itinerarios terap^euticos de sujeitos com problematicas decorrentes do uso prejudicial de

alcool.Interface (Botucatu)17(45), 433–444.

McCrady B.S. (2012) Treating alcohol problems with couple therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology: in Session68(5), 514– 525.

Melnyk B.M. & Fineout-Overholt E. (2010) Evidence-based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

Milivojevic D., Milovanovic S.D., Jovanovic M., Svrakic D.M., Svrakic N.M., Svrakic S.M. & Cloninger C.R. (2012) Temperament and character modify risk of drug addiction and influence choice of drugs. The American Journal on Addictions 21(5), 462–467.

Mohr W.K. (2000) Partnering with families. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services38(1), 15–22. Nkowane A.M. & Saxena S. (2004) Opportunities for an improved

role for nurses in psychoactive substance use: review of the literature.International Journal of Nursing Practice10(3), 102–110. Noy M.R. (2014) Perception of family functioning is different in patients and families. Revista del Hospital Psiquiatrico de la Habana11(Suppl.). Retrieved from http://www.revistahph.sld.cu/ sup%20esp%202014/funcionamiento%20familiar.html on 20 November 2015.

Pacek R.L., Storr C.L., Mojtabai R., Green K.M., La Flair L.N., Alvanzo A.A., Cullen B.A. & Crum R.M. (2013) Comorbid alcohol dependence and anxiety disorders: a national survey.

Journal of Dual Diagnosis9(4), 271–280.

Pasternak A. & Scheir K. (2012) The role reversal in the families of Adult Children of Alcoholics. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy3, 51–57.

Qu Y., Tan M. & Kutner M.H. (1996) Random effects models in latent class analysis for evaluating accuracy of diagnostic tests.

Biometrics52, 797–810.

R Core Team (2014) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

Rangarajan S. & Kelly L. (2006) Family communication patterns, family environment and the impact of parental alcoholism on

offspring self-esteem. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships23(4), 655–671.

Rigoni M.S., Susin N., Trentini C.M. & Oliveira M.S. (2013) Alcoolismo e avaliacß~ao de funcß~oes executivas: uma revis~ao sistematica.Psico44(1), 122–129.

Sakiyama H.M.T., Padin M.F.R., Canfield M., Laranjeira R. & Mitsuhiro S.S. (2015) Family members affected by a relative’s substance misuse looking for social support: who are they?Drug and Alcohol Dependence147, 276–279.

Salize H.J., Jacke C., Kief S., Franz M. & Mann K. (2012) Treating alcoholism reduces financial burden on care-givers and increases quality-adjusted life years.Addiction108, 62–70. Scherer M., Worthington E.L. Jr, Hook J.N., Campana K.L., West

S.L. & Gartner A.L. (2012) Forgiveness and cohesion in familial perceptions of alcohol misuse. Journal of Counseling and Development90, 160–168.

Senger A.E.V., Ely L.S., Gandolfi T., Schneider R.H., Gomes I. & De Carli G.A. (2011) Alcoolismo e tabagismo em idosos: relacß~ao com ingest~ao alimentar e aspectos socioecon^omicos. Revista Brasileira de Geriatria e Gerontologia14(4), 713–719.

Sh€afer G. (2011) Family functioning in families with alcohol and other drug addiction.Social Policy Journal of New Zealand37, 1–17.

Silva S.E.D. & Padilha M.I. (2013) Alcoholism in adolescents’ life histories: an analysis in the light of social representations.Texto and Contexto Enfermagem22(3), 576–584.

Silva S.E.D., Padilha M.I.C.S., Borenstein M.S. & Spricigo J.S. (2011) Alcoolismo e a producß~ao cientıfica da enfermagem brasileira: uma analise de 10 anos. Revista Eletronica de^ Enfermagem13(2), 276–284.

Silva S.E.D., Padilha M.I. & Araujo J.S.A. (2014) Interaction of the teen with the alcoholic relative and its influence for alcoholic addiction. Revista de Enfermagem UFPE online8(1), 59–68.

Swanson S.A., Lindenberg K., Bauer S. & Crosby R.D. (2012) A Monte Carlo investigation of factors influencing latent class analysis: an application to eating disorder research.International Journal of Eating Disorders45(5), 677–684.

Tsai Y.F., Tsai M.C., Lin Y.P., Weng C.E., Chen C.Y. & Chen M.C. (2010) Facilitators and barriers to intervening for problem alcohol use. Journal of Advanced Nursing 66(7), 1459–1468. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05299.x.

Vargas D. & Soares J. (2013) Publicacß~oes de enfermeiros sobre

alcool e alcoolismo em anais do Congresso Brasileiro de Enfermagem.Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem.66(13), 313–320. Walitzer K., Dermen K., Shyhalla K. & Kubiak A. (2013) Couple communication among problem drinking males and their spouses: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Family Therapy35, 229–251.

Walker L. & Avant K. (2011)Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing, 5th edn. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. World Health Organization (2014) Global Status Report on

Alcohol and HealthWHO, Geneve.

TheJournal of Advanced Nursing (JAN)is an international, peer-reviewed, scientific journal.JANcontributes to the advancement of evidence-based nursing, midwifery and health care by disseminating high quality research and scholarship of contemporary relevance and with potential to advance knowledge for practice, education, management or policy.JANpublishes research reviews, original research reports and methodological and theoretical papers.

For further information, please visitJANon the Wiley Online Library website: www.wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/jan

Reasons to publish your work inJAN:

• High-impact forum:the world’s most cited nursing journal, with an Impact Factor of 1917–ranked 8/114 in the 2015 ISI Jour-nal Citation Reports©(Nursing (Social Science)).

• Most read nursing journal in the world:over 3 million articles downloaded online per year and accessible in over 10,000 libraries worldwide (including over 3,500 in developing countries with free or low cost access).

• Fast and easy online submission:online submission at http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jan.

• Positive publishing experience:rapid double-blind peer review with constructive feedback.

•Rapid online publication in five weeks:average time from final manuscript arriving in production to online publication.