Gustavo Santarém Silva

UMinho|20

15

outubro de 2015

Pharmaceutical R

egulation and Pseudo-generics

Universidade do Minho Escola de Economia e Gestão

Pharmaceutical Regulation and

Pseudo-generics

Gusta

vo Santar

Dissertação de Mestrado

Mestrado em Economia Industrial e da Empresa

Trabalho efectuado sob a orientação do Professor Doutor Odd Rune Straume

Gustavo Santarém Silva

Universidade do Minho Escola de Economia e Gestão

Pharmaceutical Regulation and

Pseudo-generics

DECLARAÇÃO

Nome: Gustavo Santarém Silva

Endereço electrónico: gustavosantaremsilva@gmail.com Telefone: 916044399 Número do Bilhete de Identidade: 14052001

Título dissertação: Regulation Polcies and Pseudo-generics Orientador(es): Professor Dr. Odd Rune Straume Ano de conclusão: 2015

Designação do Mestrado: Economia Industrial e da Empresa

É AUTORIZADA A REPRODUÇÃO INTEGRAL DESTA TESE/TRABALHO APENAS PARA EFEITOS DE INVESTIGAÇÃO, MEDIANTE DECLARAÇÃO ESCRITA DO INTERESSADO, QUE A TAL SE COMPROMETE;

Universidade do Minho, 30/10/2015

Acknowledgements

First of all, a special thanks to professor Odd Rune Straume, for all of his time, judgement and dedication to this thesis. Without him, this work would not be possible.

To all Maxima’s contributors, the open-source computer algebra system software used to develop the model and plots included in this document, for the help debugging, troubleshooting and preparing the mathematic model that provided all the results;

To all professors that lectured me in the course, in which they contributed to my professional and personal development.

Políticas de Regulação da Indústria Farmacêutica e os

Pseudo-Genéricos

Resumo:

Na indústria farmacêutica, empresas de renome têm lançado génericos dos seus próprios produtos, aumentando, dessa forma, a competição nas variedades genéricas presentes no mercado.

Algumas teorias demonstraram que esta ação estratégica pode resultar em aumentos gerais de preços, resultando em maiores gastos com produtos farma-cêuticos para as famílias. Por esse motivo, os reguladores têm procurado criar mecanismos de controlo dessas despesas sendo, os mais comuns, os preços de referência e os preços máximos. Embora diferentes em natureza, têm ambos o mesmo objetivo.

O propósito desta dissertação é analisar o nível de incentivo, considerando, em simultâneo, os preços máximos e sistemas de co-pagamento, tornando este modelo mais ajustado à realidade destes mercados. Os resultados demonstram que é possível desincentivar as empresas a lançar estes pseudo-genéricos, dentro de um intervalo de parâmetros.

A investigação está dividida em cinco secções diferentes. A primeira apre-senta as definições mais importantes e contempla um enquadramento geral da indústria farmacêutica; De seguida, constam os resultados mais importantes e convenientes para esta dissertação, obtidos na revisão de literatura do tema, acrescentando algumas extensões. As secções seguintes são dedicadas a uma análise teórica e à exposição e análise dos resultados.

Abstract

:

Brand-name pharmaceutical firms have been releasing generic versions of their own branded varieties to the market, which potentially increases competition for other existing generic varieties.

Some theories have shown that this strategy can increase all firms’ prices, including the independent generics, leading to higher pharmaceutical expenditure to all patients. Regulators have then been focused on imposing some sort of control mechanisms, and the two most common ones are reference pricing and price caps. Even though they differ in nature, their purpose is the same.

This research analyzes the incentive level of brand-name firms to release a pseudo-generic under a price cap regulation, while considering a co-payment system. This makes this model more comparable to a real-life scenario. The outcome shows that regulation can reduce the incentive level of brand-name firms to release a pseudo-generic drug to the market.

The research is divided into five different sections. The first shows some im-portant definitions and a general framework of this industry. Next comes the liter-ature review, which shows some of the most important results that can be found in the literature, and some other reasonable and important extensions - such as effects on research and development. The remaining sections are dedicated to a theoretical analysis, result exposure and conclusions from those results.

CONTENTS CONTENTS

Contents

1

Tables and Figure Index

vii2

Introduction

83

Institutional Background

104

Literature Review

145

Theoretical Analysis

235.1

Without PG

. . . 265.1.1

Restriction on Parameter Values

. . . 285.2

With PG

. . . 295.2.1

Restriction on Parameter Values

. . . 325.3

Equilibrium market structure

. . . 355.4

Reference Pricing Scheme

. . . 365.4.1

First scenario: I does not sell PG

. . . 375.4.2

Second scenario: I sells PG

. . . 385.5

The Effects of Regulation

. . . 416

Concluding Remarks

45 7Appendix

46 7.1Profit expressions

. . . 467.1.1

With a Price cap

. . . 467.1.2

With a Reference Pricing Scheme

. . . 477.2

Average prices

. . . 487.2.1

With a Price Cap Scheme

. . . 48LIST OF TABLES

1

Tables and Figure Index

List of Figures

1 Graphical representation of the consumers’ utilities. . . 33

2 Price cap thresholds . . . 36

3 Average price in order to the price cap values. . . 42

4 Incumbents profits, in order to the price cap. . . 43

5 Entrant Firm’s profits, in order to the price cap. . . 44

List of Tables

1 Numerical example: Values attributed to the variables. . . 41 2 Minimum and maximum values that the price cap can assume in equilibrium. 412

INTRODUCTION

2

Introduction

The pharmaceutical industry is a relevant topic of research because it affects a lot of parties simultaneously. For instance, the pharmaceutical expenditures of families usually represent a significant share of their budgets, while policy makers have an important role in this industry because their actions and decisions can affect firms and families at the same time.

Different policies can change the level of regulation existing in a given market, which can cause a wide variety of effects. The pharmaceutical expenditures are significant to governments, since it is common to observe a co-payment scheme between public health systems and patients. For instance, Bardey et al. (2010) mentioned that “a dramatic increase of pharmaceutical expenditures has been observed in most developed countries. During the last two decades, it grew over 17% in USA”. On the other hand, these expenditures may also represent a cost for the government, specially in those countries where we can find some sort of public health insurance systems.

Regardless of this increase in expenditures, the pharmaceutical industry is also characterized by heavy investments in research & development to increase quality and effectiveness of their drugs. Thus, they try to maximize their profits by increasing the price of their drugs. Therefore, this topic has numerous im-plications to policy makers, since they try to balance total welfare. Nonetheless, excessive is not a solution, since it may drive some companies out of the market. The main topic of this study is focused on the pseudo-generic strategy. Even though this topic has been lightly reviewed by Rodrigues et al. (2014), the focus is then to analyze the firm’s incentives to release a pseudo-generic under price

cap regulation, rather than reference pricing1. The research of these authors has

tried to analyze the possible anticompetitive effect of pseudo-generic.

The pseudo-generic drug strategy involves a brand-name firm releasing a pseudo-generic version of its main product, which will increase competition against other generic firms. The consequences of this strategy may result in higher prices,

2

INTRODUCTION

thus higher profits for all firms2. Since it is a commonly used strategy by

brand-name firms, it is important to observe their behavior when facing a price cap - a scenario that was not studied before.

Regulation has been a common methodology to restrict such unbalanced sce-narios in an attempt to level total welfare, although the results of this increase in regulation have not been explicitly proven. All models have specific impositions that may not apply to real life scenarios and that is a recurring issue in this topic. This dissertation tries to consider some assumptions that have a parallel in real life. The main addition to the literature of this dissertation is the price cap scheme. Although many other researches have focused on reference pricing, this will analyze the same problem but considering a different policy.

Price cap schemes represent the maximum price that the firm can charge within that given market. They can charge less, but never higher than the defined level.

The outcomes of this dissertation will contribute to the understanding of how the pharmaceutical markets behave when facing regulation.

3

INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUND

3

Institutional Background

Drug firms are in an oligopolistic market typified by a limited number of competi-tors, differentiated products and strong innovation strategies. Consequently, it

can be said that these firms compete in prices3.

Demand can be characterized with price insensitivity, specially when public or private insurers reimburse their drug expenditures. Insurance firms tend to

encourage over-use, higher prices and, therefore, welfare losses4.

The incumbent firm first invests in research and development to get a new drug and then releases it to the market. To avoid competition, they make sure

these drugs are under protection of a patent contract5 that will last for a period of

time. Generic drug firms usually enter in a drug market after that patent protection

period ends6, offering a lower priced drug that has the same chemical ingredients

and can be used for the same therapeutic usages. Even though these generic drugs are highly tested and submitted to a lot of tests to prove their efficiency and confirm the lack of harmul effects to the patient’s health, people perceive generic

drugs with less quality7.

IIt is important to have a deep understanding of how generics behave in this industry. There is evidence that being the first generic to enter a market can play

a crucial role8. Hollis (2002) work ran an empirical research, using Canadian

data, to prove that entering first allows significant and long lasting higher market shares. Their main justification is related to switching costs and lack of incen-tives to undercut prices. Hollis (2002) also conducted small interviews and got

3Since they supply the market with differentiated products - in Belleflame and Petz, 1st edition (2010), but many

authors have used this sort of competition to analyze the market itself: Bardey et al (2010), Brekke et al. (2006), (2007) and (2009) are great examples.

4Mentioned in López-Casasnovas and Puig-Junoy (2000).

5As heavily debated in Caves et al. (1999), although implictly assumed in many other papers as well.

6Standard assumption in regard to this generic firms’ behavior, which is also frequently used in the literature:

Ghislandi (2011), Brekke et al. (2007) and (2011), Rodrigues et al. (2014) and (2015).

7See Hollis (2004) and Rodrigues et al. (2014).

3

INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUND

interesting statements from pharmacists. Pharmacists agree they prefer to keep selling the first generic that has approached them. To start, it is troublesome to explain technical terms to people who are not familiar with it and most people feel uncomfortable changing generics constantly. Patients may agree with one generic, but they highly disapprove changing again.

One extension we can find in this research is that generic firms still have an incentive to enter a given market, even if there is another generic firm already,

depending on the ability of these firms to work through the patent contract9.

Although, one can argue that when firms face switching costs, others can per-suade consumers to switch products by offering a higher-quality product or using lower price strategies. But none of these strategies apply to this industry: By def-inition, all generics have equal efficiency. Notwithstanding, the introduction of a control mechanism, like reference pricing or price cap, can change the demand’s

willingness to pay for a certain drug10.

In most of the developed countries, pharmaceutical regulators have adopted expenditure control mechanisms. These mechanisms aim to reduce the drugs’

prices and also to increase competition between the existing firms in that market11.

Some authors have confirmed its effectiveness in the short run, even though long run effects could not be yet concluded.

The two most common mechanisms of expenditure control are Reference Pric-ing Schemes and Price Cap Schemes. Reference pricPric-ing introduces a maximum reimbursement level. This means consumers pay the difference if the drug is priced above that level. If the drug price is equal or inferior to that level, they pay only a fraction of the price. Price caps affect supply directly by introducing

a maximum price that firms can charge12. However, under a reference pricing

scheme, firms set prices freely. Authors have concluded that how these policies are defined is very important as well, since they can cause different impacts on

9Hollis, A. (2002).

10See Rodrigues et al. (2014).

11Stated in Brekke et al. (2007), Kaiser et al. (2014) and Miraldo (2009).

3

INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUND

the market13.

There are also some concerns about possible anticompetitive effects of reg-ulation, as analyzed in Zweifel et al. (1996), and Danzon et al. (1997). As shown in Brekke et al. (2007) and in Miraldo (2009), when the reference price

(furthermore as Pr) is endogenously given14, it produces a small incentive for

generic firms to lower their prices to gain higher market shares, thus creating a cost-saving scenario to consumers. On the other hand, when the reference pric-ing level is exogenously given, Brekke et al. (2007) concluded that this situation leads to higher prices for all firms, leading to an anticompetitive scenario. Also, their empirical analysis shows that exogenous RP leads to a price convergence, where the branded price is lower and the generic varities have higher prices. Fur-thermore, Miraldo (2009) shows that RP is not always beneficial. Even if prices are reduced after introducing the mechanism, quality or market coverage can be reduced, hence implying a less optimal result to consumers.

Branded firms often release their own version of a generic drug to compete

directly against other generics in that market15. One should not interpret this

pseudo-generic (furthermore asP G) as a way to create barriers to new entrants.

In fact, Kong and Sheldon (2004) have studied the possibility of usingP G as a

way to deter entry, but Rodrigues (2006) has shown their work has flaws and that

usingP G with that purpose may not be that profitable. Kong and Sheldon (2004)

stated the required capacities and conditions to effectively deter generic entry without harming their main product’s equilibrium. Rodrigues (2006), however, argued that, in reality, the strategic variable used to achieve entry deterrence is the branded quantity and not the pseudo-generic itself. Also, as shown in

Rodrigues et al. (2014), the incentives of a brand-name firm to release a P G

drug are nonexistent when the firm does not face any competition - thus the monopoly case is rarely analyzed.

As mentioned in the beginning of this section, the pharmaceutical industry

13Denmark is an exception, since they have an hybrid solution - Explained deeply in Kaiser et al. (2014).

14Thus, allowing firms to manipulate the reference pricing level -P r.

3

INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUND

is supplied with many differentiated products. The industry has many products and each one is vertically and horizontally differentiated. Vertical differentiation translates into quality differences and also contemplates the assumption that branded firms can charge higher prices without suffering the otherwise expected outcomes. The prevailing horizontal differentiation degree reflects the

transporta-tion costs occurred when purchasing drug B, P or P G. These transportation

costs can be observed on each drug’s flavor, shape or something else other than its active components. Hence, this is only applicable among generics but still

important to consider16.

4

LITERATURE REVIEW

4

Literature Review

The literature on regulation of the pharmaceutical industry is vast, although its recent extensions are more focused on reference pricing. Price caps have less theoretical reviews. Nevertheless, price cap regulation is also important. Ana-lyzing it can help us understand how the pharmaceutical markets behave when facing this type of regulation and if it reduces the incentive level to release a pseudo-generic.

As aforementioned, we are looking at an oligopolistic market, typified with different varieties of pharmaceutical drugs, vertically and horizontally differenti-ated. Often, there is an incumbent firm and an entrant one. The former offers

a branded variety and the latter offers a generic version of the branded variety17.

That means it is a chemically equivalent solution, offered at lower prices18.

Never-theless, the incumbent firm, whenever it enters a market, usually has a protection period offered by a patent contract, meaning that they face no competition for a

certain period of time19. When that period ends, the branded firm has the

possi-bility to license its own version of a generic drug20. Regardless of its options, the

entrant firm may enter that market after that same period, offering a lower priced drug.

Releasing a pseudo-generic exerts pressure in the generic market segment, which will also allow the incumbent firm to focus their branded drug on the part

of the demand that is willing to pay higher prices21. The reason we can conclude

this statement is because pseudo-generic drugs increase competition to the

in-17See Ghislandi (2011).

18See Bergman et al. (2003).

19A conclusion proposed by Hollis (2002), which also explains why generic firms always enter the market after

this period ends.

20Hollis (2002) and (2005) mentions that pseudo-generics represent a quarter of total generic sales in Canada

and Australia - Hence, it then becomes a significant value and important strategy to consider when analyzing these markets. And there is a plus: Kong and Sheldon (2004) demonstrated the strategic effect of pseudo-generics in deterring entry by the independent generic firms.

21Hollis (2005) proves empirically this effect, even though Danzon et al. (1996) showed the convergence theory,

4

LITERATURE REVIEW

dependent generic firm22. Although it seems unreasonable, the incumbent firm

has no incentive to lower the price of both drugs, since it will shift market shares

away from the pseudo-generic23.

From Rodrigues et al. (2014), we can also conclude that the presence of a pseudo-generic drug may result in higher prices for all drugs. Hollis (2005) also claims that if the pseudo-generic enters after the true generic, the total welfare is inferior than if the independent generic enters first. If so, then it is cost-saving for all parties.

However, the results of introducing a generic drug when there is only a branded drug, are quite ambiguous. As quoted in Aronsson et al. (2001), Grabowski et al. (1992) suggest that, due to the price differentials between the two drugs, the branded firm has an incentive to reduce its price or otherwise suffer a se-vere decrease in market share. Caves et al. (1991) are in line with this train of thought. Frank and Salkever (1997) found the opposite results: Branded drug prices tend to increase after generic entry, while the price of already established

generic drugs tend to decrease24. The theoretical explanation of Aronsson et al.

(2001) about these behaviors is that the higher the price of the original (branded) product, relative to the average of generic drug prices, the larger the decrease in market share will be. This effect may be more severe in some products, depend-ing on their active chemical, accorddepend-ing to Aronsson et al. (2001). Moreover, from their paper, we can note that reference pricing is likely to put a downward pres-sure on the incumbent firm (brand variety producer) to decrease prices. Another important variable to consider is the number of competitors which can create more pressure to the market.

Pharmaceutical markets are frequently associated with power exertions from firms, having higher profits while reducing consumer’s surplus and sometimes

lowering their products’ quality as well25. This situation led to the creation of

22See Ferrándiz (1999), Lopez-Casanovas (2000), Cabrales(2003).

23See Rodrigues et al. (2014).

24Note that his works contemplates more than one generic competitor.

4

LITERATURE REVIEW

different control mechanisms. The two most common methods are price caps and reference price and, even though they seem similar, their nature is relatively

different26. Under a Price Cap Scheme (PCS), the regulator sets a maximum price

that can be charged for each product. Usually, this price cap (P ) is set lower

than the incumbent firm profit-maximizing price in a non-regulated scenario27. We

can say, assuming that Pb > Pg, that the price cap will be P ≤ Pb∗N R.

On the other hand, under a Reference Pricing Scheme (RPS), the regulator will set a maximum reimbursement level that the consumers will receive back, when they buy a pharmaceutical drug. We can use this definition to show how the

price range would be, whereα is the reimbursement percentage, Pr represents

the reference pricing level andPi is the price of drugi.28:

P i = αPi if Pi ≤ Pr αPr+ (Pi − Pr) if Pi > Pr

The first main argument is about whether reference pricing and price caps have a positive effect in the market or not. In a way, it depends on the policy goal - lower prices or increase quality are just two quick examples.

Brekke et al. (2009) have concluded that there is a positive effect of price cap regulation, meaning that it lowers the brand-name firm price and it also leads to a lower price of the generic firm - thus, positive results if the objective is to reduce all prices. In this scenario, the generic firm will have more incentives to undercut prices, in order to maintain market share.

When there is a reference pricing scheme, the result will be same, although the incentives of generic firms to lower the price will be less. This means that they will both lower their prices, but the generic firm will not reduce its price as low as in

the price cap situation29. In fact, the firms’ strategic reaction is worth mentioning:

26See Brekke et al. (2009).

27OrP∗N R

b , which stands for the equilibrium price of the brand-name firm, in a non-regulated scenario.

28Many authors have came up with different definitions for reference pricing, even though it all converges towards

the same essential elements. Some examples: López-Casasnovas et al. (2000), Kanavos et al. (2003), Miraldo (2009), Brekke et al. (2009).

4

LITERATURE REVIEW

As a reaction to reference pricing regulation, the brand-name firm will lower their prices in order to compete for market share, but, the generic firm will lower its prices too. They also concluded that reference pricing leads to lower prices than price caps, unless the level of regulation is excessively strict - say, if the price cap is close to the marginal costs. In the same paper, we can find an empirical analysis that leads to the same results. Their simulations also consider different kinds of reference pricing setups, which were previously studied in Brekke et al. (2007).

There are two main different kinds of setups for reference pricing: Generic Reference Pricing (GRP) and Therapeutic Reference Pricing (TRP). Usually, GRP contemplates products with the same active chemical ingredients, while TRP clus-ters products with chemically related active ingredients that are pharmacological equivalent and have comparable therapeutic effects, meaning that they can be used for the same treatment. There may be more types of drug clustering. These

two though, are the most common30. GRP contemplates only off-patent

brand-name drugs and their generic substitutes, while the second type of cluster may included on-patent drugs.

It is important to mention that the literature concluded that GRP not only re-duces prices of drugs in the reference cluster, but also puts a downward pressure on the price of non-included but therapeutically equivalent drugs. Brekke et al. (2007) have shown that TRP has a more severe result in the market (leading to lower prices of all drugs and lower profits to the incumbent firm), increasing price competition and thus, the patent-holding firm tends to lower the price of its prod-ucts - since a generic firm will enter the market and will gain market share, mostly

from customers with higher price elasticity31. TRP also leads to the lowest

mis-match costs in regard to welfare. Without reference pricing, according to these authors, we would have mismatch costs minimized, but drug prices maximized. From these conclusions, we can observe that reference pricing is important to

30In Galizzi et al. (2011).

4

LITERATURE REVIEW

lower drug prices.

Some other authors have also discussed the anticompetitive effects of pseudo-generics, especially when we consider that those are usually released by brand

name firms in order to avoid generic competition32. Some authors believe that

pseudo-generics may be used to deter entry33. In fact, Hollis (2005), shows that

the introduction of a pseudo-generic prior to the end of the patent protection pe-riod (meaning that no true generic will be released right after the termination of the patent protection period) delays the entry of an independent generic.

However, many authors have disapproved their argument. Kong and Shel-don (2004) also mention the possibility to deter generic entrance using pseudo-generics. However Rodrigues (2006), showed that pseudo-generics are not the only type of drug capable to deter entry - entry deterrence can be accomplished with the branded variety as well.

Even though the work was proved incomplete, Kong and Sheldon (2004) initial assumptions are still viable, but under narrower conditions. For instance, Kong and Sheldon (2004) mentioned that prices are the most important variable to deter entry, but Rodrigues (2006) showed how the branded-variety quantities can lower generics’ incentives to enter a given market. He also showed that this is more optimal than using the pseudo-generic. Kong and Sheldon (2004) also showed that, for any level of generic entry costs, the incumbent firm will only find profitable to supply pseudo-generics as long as the profit margin of the branded variety is sufficiently small.

However, none of these models were able to explain the presence of both

drugs in the same market34 and, most of them, do not consider the existence of

co-payment in their market35.

In Rodrigues et al. (2014), in a model based on entry accommodation, it was

32Férrandiz (1999) has first induced such results, but Kamien and Zang (1999) are also in line with this strategy.

33Such as Kong and Sheldon (2004), Granier et al. (2010) and (2012).

34See Rodrigues et al. (2014).

4

LITERATURE REVIEW

not possible to observe the actual impact of pseudo-generic drugs. Indeed, the authors observed that these increase competition since they increase the number of low-cost alternatives. Their short numerical example shows that the introduc-tion of a pseudo-generic leads to higher prices and higher profits, for all drugs, also leading to a reduction on consumer surplus. This result is also observed when they considered the existence of a co-payment scheme - Rodrigues et al. (2015). In both of their models, prices behave as strategic complements. The branded firm has no incentive to reduce its price because it would steal market share from itself. Therefore, the pseudo-generic drug behaves as an intermediate drug. The incumbent firm can reduce the market share from the original generic drug with the pseudo-generic, although it is not as effective as with the branded variety. This is due to the horizontal differentiation. Consumers trade off a lower price for transportation costs.

Of all these conclusions about pseudo-generic competition, the main one is that, in this model with all its assumptions, pseudo-generics soften competition among generic varieties and lead to higher prices and profits for all competitors, thus decreasing consumers’ welfare.

Authors also noticed that reference pricing is more beneficial to consumers than a fixed reimbursement system, since firms can adjust their prices to a level

that consumers do not benefit of lower price strategies36. Nevertheless, under

both scenarios, the introduction of a pseudo-generic drug leads to an overall in-crease of prices.

The discussion now is about the effects of these control mechanisms and the pseudo-generics in regard to welfare. As stated before in the literature, regulators have the role to balance the quality levels of all drugs and socially efficient

loca-tions of firms37. One can observe that both can change the outcomes significantly

for all firms and it can even be counter-productive. There is a train of thought in

the literature that pseudo-generics have a anticompetitive effect38, decreasing the

36See Rodrigues et al. (2015).

37See Brekke et al. (2006).

4

LITERATURE REVIEW

social welfare39.

By the policy definition, however, one can deduce that each instrument changes different sides of the market. For example, it is clear that reference pricing aims to stimulate demand, while price caps tend to limit the most expensive drug, thus increasing the number of strategic options that competitors can take.

Hollis (2005) quoted that Kamien and Zang (1999) have shown that pseudo-generics can increase welfare, specially when it “assumes a Stackelberg lead-ership position in the generic industry” which leads to higher generic outputs. However, this assumption is relatively unrealistic because capacity constraints are not important in this industry. Nevertheless, the results obtained by Hollis (2005) shows that pseudo-generics may lead to higher profits and a less-than

optimal scenario in regard to welfare40. In Brekke et al. (2007), we can see that

TRP leads to a better scenario, under the welfare topic, in a sense that it leads to a minor total aggregate mismatch costs than the two other systems (GRP and NRP). Cabrales (2003) shows that the best option to achieve better welfare is the one that lowers the prices the most, but their final result is not realistic because it is not possible to find real-life applications.

We can also assume that if generics trigger competition when they enter a market, then it will lead to a cost-saving scenario, by the fact that both firms will

reduce their price and there is a shift in demand towards the generic drug41, also

because it is cheaper.

Another important issue arises when we consider profit reductions imposed

by regulation that is quality and innovation42. The literature agrees that

differen-tiation softens quality competition43 but, due to the nature of generic drugs, the

differentiation degree can be low among these varieties. Sometimes, firms prefer

39See Hollis (2002).

40Specially since these drugs, the pseudo-generics, will not deter entry of other generics, but will indeed lead to

higher prices.

41See Brekke et al. (2011).

42See Bardey et al. (2010).

4

LITERATURE REVIEW

to invest less in research and development to be able to respond to lower price strategies. However, as stated in Brekke et al. (2006), the opposite behavior is of-ten observed as well: firms try to locate further apart, thus reducing competition and investing more in quality.

These markets usually have heavy investments in the research and develop-ment departdevelop-ments, whereas their incentives to maintain such investdevelop-ments may become limited. The consequences are several, but the most intuitive one is the problem of less pioneer drugs, as mentioned in Bardey et al. (2010). They also suggest that the threat of generic competition increases the incentive to invest in research and development, since this can allow them to located further apart of the competing drug.

Cabrales (2003) also observes the effects of generic entry on quality, conclud-ing that market shares depend only on the indifferent consumer’s location. The indifferent consumer location depends on the ratio between the price ceiling and

quality44. If prices are more than proportionally reduced than quality, this

indiffer-ent consumer will be located closer to the cheapest variety. This argumindiffer-ent also helps us understand why many of these firms dedicate a significant amount of their budget to marketing campaigns - they try to increase the perceived quality by consumers.

Brekke et al. (2009), quoting Ellison et al. (1997), pointed out that therapeutic competition may stifle innovation away. Under a reference pricing scheme, which aggregates both branded and generic drugs, there is therapeutic competition.

The equilibrium levels of quality are also decreasing in transportation costs,

although it is increasing in the price variable45. We can also say that these

obser-vations have implications on how the policy itself is built.

Brekke et al. (2006) have shown that, for exogenous locations, the optimal equilibrium can be achieved, even though it cannot be achieved for endogenous locations. For endogenous locations, the first-best equilibrium can only be achieve at the cost of a sub-optimal level of quality.

44See Cabrales (2003).

4

LITERATURE REVIEW

There are some topics about whether insurance firms can increase competi-tion or not, in which López-Casasnovas et al. (2000) have stated that insurances tend to encourage over-use, leading to higher prices and, thus, welfare losses. In the end, insurances tend to make consumers less price sensible, making demand stronger.

5

THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

5

Theoretical Analysis

The following analysis is divided into different sections, serving different purposes. The goal is to have many different scenarios where we can observe and explain the different results, considering the same set of assumptions. The final comparison is between a price cap scheme and a reference pricing scheme.

The overall framework of the model is inspired by Rodrigues et al. (2014) model, which contemplates a free competition scenario, between a brand-name firm and an independent generic firm, without any sort of regulatory control. How-ever, this model has an addition to theirs, since there is a comparison between a regulated and a non-regulated scenario.

The ultimate goal of this investigation is to observe the incentive levels of

brand-name firms to release a pseudo-generic drug, under price cap regulation46.

And, in order to make the model as realistic as possible, we will assume an

exoge-nous co-payment rate and an exogeexoge-nous price cap restriction -α and P ,

respec-tively. For simplification purposes, this research will consider that all drugs have equivalent chemical ingredients, and thus they serve for the same therapeutic usage.

The monopoly case will not be considered. The reason being that this scenario only contributes to a very intuitive outcome: Regardless of the market structure we define, that is, either in co-payment or under a price cap scheme, the brand-name firm will always choose a price equal to the maximum price consumers are willing to pay for, or in the presence of price cap regulation, the firm will charge as much as it can.

In this model, we will have two firms competing - an Incumbent and an Entrant firm - and they choose their prices simultaneously. The incumbent firm sells a

branded variety, noted by b, while the entrant will serve a generic variety, noted

byg. The incumbent can choose to sell a generic variety as well, noted by pg

-from pseudo-generic. Capitalized forms of the varieties represent their respective quantities.

5

THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

The branded and generic varieties are chemically similar, but consumers per-ceived them differently, in regards to quality. To consumers, the branded variety offers a drug with better quality. Consumers also perceive the generic varieties dif-ferently among each other. They assume that these are horizontally differentiated meaning that, for instance, they differ in size, shape and/or taste. Nevertheless, these varieties are not vertically differentiated.

The market is composed by a mass of consumers distributed over an interval [0, 1] that reflects the space of the products’ characteristics. The generic variety is located at the left-end point, while the branded is located at every point of the Hotelling line. The pseudo-generic, if launched, is located somewhere at the mid-point.

Consider the following utility function of consumer i, who is located at point

Ci, is given by the following expression, when there is no pseudo-generic drug:

CSi =

γ − αPg − t ∗ Ci , if the consumer buys g

β − αPb , if the consumer buys b

(5.1)

Similarly, the utility function of the consumeri, when there is a pseudo-generic

drug, is given by:

CSi =

γ − αPg − t ∗ Ci , if the consumer buys g

γ − αPpg − t ∗ |Ci − 12| , if the consumer buys pg

β − αPb , if the consumer buys b

(5.2)

Buying a generic variety implies a linear transportation cost along the Hoteling

line, with slope t > 0. If Ci represents the consumer type i , Ci measures the

distance between consumer i’s location and the left end point of the interval.

To contemplate the vertical differentiation betweenb and g, we have to assume

that the consumers’ willingness to pay for the products are different. Since the most common perception is that the branded varieties have better quality than the

generic ones, we then assume thatβ > γ > 0, which represent the consumers’

5

THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

Also, the prices of these drugs are usually different. For this reason, in this model, the price of the branded variety is the most expensive, while the indepen-dent generic is the cheapest one. The pseudo-generic drug will have its price defined in the middle of these two. Thus, the Nash equilibrium in our model will

be characterised byPb > Ppg > Pg47.

In regard to the pseudo-generic drug, if this one is released to the market,

the assumption will be that it is located at 12 of the Hotelling line. This

assump-tion allows us to simplify the analysis further on. Otherwise, having exogenous

locations forpg would mean there is a numerous range of values that we could

assume to hold the equilibria in the different scenarios.

A consumer either buys one of the available drugs or none - there is no pos-sibility to buy one of each variety. Consumers choose the variety that maximizes their surplus.

One last remark is about R&D and operating costs. Even though these play a fundamental role in the success of the firms in this industry, they will not be considered from now on, since the purpose of this investigation is to study the incentive level of the incumbent firm to release a pseudo-generic drug, and not entry deterrence. Therefore, all variable costs associated are normalized to zero. However, we will assume a fixed cost, that is specific to having a drug released to the market. This implies that both firms are somewhat equally efficient.

In this market setting, we are looking for a Bertrand-Nash equilibrium48.

How-ever, in order to be fully able to compare the outcomes, we have to consider two scenarios for all setups: In the first scenario, the brand-name firm (the

incum-bent firm - furthermore asI) does not release a pseudo-generic drug and, in the

second scenario,I introduces a P G drug. Also, there will be a short comparison

between the regulated and non-regulated scenarios afterwards.

47This assumption has been taken throughout the literature and it was also considered in Rodrigues et al. (2014)

and (2015).

5.1

Without PG

5THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

5.1

Without PG

In this scenario, the incumbent firm will not produce nor release a pseudo-generic

drug to the market. Taking into consideration that Pb > Pg, and also that β >

γ > 0 to represent vertical differentiation (perceived differences in the quality of the drugs), we can define our market equilibrium with the following steps.

Consider the consumer i utility function as the one provided in EQ 5.1.

Before calculating the equilibrium prices, quantities and profits, one needs to

find the indifferent consumer. That can be done by computingγ−αPg−tCb,g =

β − αPb in order to Cb,g, where Cb,g is the location of the consumer who is

indifferent between the brand-name and the generic drugs.. Algebra shows that:

Cb,g =

α(Pb − Pg) − (β − γ)

t (5.3)

Assuming that consumers are uniformly distributed on [0,1], with total mass

equal to 1, we can define each firm’s demand function as B = 1 − Cb,g and

G = Cb,g. We can calculate them by solving the maximization problem ofΠE =

Pg∗ G − F and ΠI = Pb∗ B − F , where F stands for a fixed cost of having a

product launched in the market. Furthermore, notice that the fixed costs will not interfere in the price setting phase, even though variable costs could, but those

are considered to be zero. The main change of introducing a fixed costF will be

shown later on the analysis. Demand does not change as well.

For the generic firm, its best-response function will be implicitly given by ∂ΠE

∂Pg = 0, which leads to:

Pg(Pb) =

1

2(Pb −

β − γ

α ) (5.4)

Similarly, for the incumbent firm, the best response function will be:

Pb(Pg) =

1

2(Pg +

t + β − γ

α ) (5.5)

If we solve a system with these two functions, it will then lead the following equilibrium prices:

5

THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

5.1Without PG

Pg∗ = t − (β − γ)

3α (5.6)

Pb∗ = 2t + (β − γ)

3α (5.7)

Calculating this non-regulated equilibrium, also allows us to know the maxi-mum value that the price cap assume which, in theory, is EQ 5.7. The equilibrium quantities for a non-regulated scenario are then:

B∗ = 1 − Cb,g = 2 3 − (β − γ) 3t (5.8) G∗ = Cb,g = 1 3 − (β − γ) 3t (5.9)

However, the scope of this research is focused on price cap regulation. As

mentioned before, the price cap establishes a maximum price,P , that the firms

can charge. According to the theory, the price cap should bind for the highest price in the market, yielding the best result in regard to welfare. Therefore, the price cap will bind for the branded variety, since it is the highest price, in this market setup. Logically, we must restrict the maximum price cap level to be equal or inferior to the equilibrium branded price in a non-regulated scenario,

P ≤ Pb∗N R, due to the purpose of a price cap scheme49. If its level is higher

than the equilibrium price in the absence of regulation, the price cap would not bind in equilibrium.

Therefore, if we replacePb = P , one can observe that the equilibrium prices

will be equal to their best-response functions:

Pg∗ = 1 2(P − β − γ α ) (5.10) and Pb∗ = P (5.11) 49P∗N R

5.1

Without PG

5THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

To find the equilibrium quantities (B∗, G∗), we replace the previous price

functions in the indifferent consumer location. Solving Cb,g with the previous

functions, we get that

Cb,g =

α(P −(12(P −(β−γ)α )))−(β−γ) t

Which is equivalent to:

Cb,g =

αP − (β − γ)

2t (5.12)

Then, we find each firm’s equilibrium quantities by solving

B∗ = 1 − Cb,g = 1 − αP − (β − γ) 2t (5.13) and G∗ = Cb,g = αP − (β − γ) 2t (5.14)

The equilibrium profits can be calculated by using the previous equilibrium prices and quantities. We are not considering any variables costs at all, so each

firm’s profit function should be Πi = Pi ∗ Qi − F50.

For these results to hold, and in order to guarantee this model follows some of the initial assumptions, we must calculate the parameter range that will hold these results.

5.1.1

Restriction on Parameter Values

The price cap binds in equilibrium. As explained before, with EQ. 5.10:

P ≤ 2t + (β − γ)

3α (5.15)

5

THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

5.2With PG

The indifferent consumer is located within the interval of [0,1].

In order to ensure that all demands are satisfied in this market setup, we should impose that the indifferent consumer’s location is somewhere in between

the interval of the Hotelling line. Solving Cb,g ≥ 0 in order to P , will give us

the minimum value that the price cap can assume, to allow the existence of this indifferent consumer in this interval. This inequality leads to a result where

P > (β−γ)α .

The second inequality, Cb,g < 1, will find us the maximum value that the

price cap can assume. However, this expression is less likely to hold for higher values of the price cap. Assuming the price cap is already maxed out, we will find

that the inequality leads to 13 − (β−γ)3t < 1, which is always true, for all levels of

P , since β > γ.

No consumer has negative surplus while consuming any drug.

Another important restriction is applied in order to ensure no negative surplus for consumers, regardless of the drug type they acquire. We must assume that

β − αPb > 0. This inequality holds for al Pb ≤ P , if:

β − α

h2t + (β − γ)

3α

i

> 0 (5.16)

Solving that in order to β, it leads to β > t − γ2.

Providing all restrictions, the equilibrium given by EQ. (5.9) and (5.10) exists if:

(β − γ)

α < P <

2t + (β − γ)

3α (5.17)

This set is non-empty if β < t + γ. Thus, equilibrium existence requires

(5.17) and

t − γ

2 < β < t + γ (5.18)

5.2

With PG

pseudo-5.2

With PG

5THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

generic drug. The regulation still applies for this case, hence, there will be a price cap that binds in equilibrium for the maximum price in the market and, by

defi-nition, that is Pb. Now, consider the consumer’s i utility function shown above,

in EQ 5.2.

Following the same steps as in the previous section 5.1, we can find each firm’s demand functions by finding their respective indifferent consumers’ loca-tion. However, for this case, we will have one more indifferent consumer, that is

indifferent between the generic varieties Cg,pg. One important reminder is that

we are considering that the pseudo-generic drug is located at 12 of the segment

[0, 1].

We can findCg,pg by solvingγ − αPg− tCg,pg = γ − αPpg− t(12− Cg,pg)

in order toCg,pg, and, we do the same steps for the indifferent consumerCb,pg,

while using the adequate utility branch. However, we must look for consumers located on the right of this indifferent consumer. Therefore, the expression is

γ − αPg − t(Cg,pg − 12) = β − αPb. These calculations will lead us to the

following locations of the indifferent consumers:

Cg,pg = 14 + α(Ppg−Pg) 2t Cb,pg = 12 − (β−γ)+α(Pb−Ppg) t (5.19)

Similar to what was done before, we now have to find each firm’s best-response

function. Assuming thatB = 1 − Cb,pg;P G = Cb,pg− Cg,pg andG = Cg,pg,

as in perspective with the Hotelling line, we find their best-response functions,

by solving the maximization problem - ∂Πi

∂Pi = 0, where i = b, pg, g. Such

computation leads to:

Pg(Pb,Ppg) = Ppg 2 + t 4α Ppg(Pb,Pg) = Pg 6 + 2Pb 3 + t−4(β−γ) 12α Pb(Ppg,Pg) = Ppg+ t+2(β−γ)4α (5.20)

5

THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

5.2With PG

Pg∗ = 6α5t Ppg∗ = 6α7t Pb∗ = 12α17t + (β−γ)2α (5.21)Implicitly, the price cap maximum value cannot surpass 17t+6(β−γ)12α . Due

to the scope of this research, we have to calculate the market as if Pb = P .

However, it is important to show the equilibrium quantities for this setup as well, which are given by solving the indifferent consumer and substituting the price variables for their equilibrium expressions. That yields:

B∗ = 1 − Cb,g ≡ 1 4 + (β − γ) 2t (5.22) P G∗ = Cb,g− Cg,pg ≡ 1 3 − (β − γ) 2t (5.23) and G∗ = Cg,pg ≡ 5 12 (5.24)

Similarly to before, if the price cap binds in equilibrium, each firm’s best

re-sponse function is the same as EQ. 5.20, but with Pb = P . We find the

equi-librium price functions by solving a smaller system, which leads to the following equilibrium prices: Pg∗ = 7t−4(β−γ)+8αP22α Ppg∗ = 3t−8(β−γ)+16αP22α Pb∗ = P (5.25)

With these equilibrium prices, we can find the equilibrium quantities using the

demand formulas previous stated B = 1 − Cb,pg, P G = Cb,pg − Cg,pg and

G = Cg,pg. Those yield: B∗ = 1 − Cb,pg = 7 11 − 3 11αP − 7 11t(β − γ) (5.26)

5.2

With PG

5THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

P G∗ = Cb,pg − Cg,pg = 9 44 + 1 11αP − 6 11t(β − γ) (5.27) G∗ = Cg,pg = 7 44 + 4 11αP − 2 11t(β − γ) (5.28)Similar to the steps made in the previous section, we find the equilibrium

profits by calculatingΠ∗I = Pb∗∗ Q∗b + Ppg∗ ∗ Q∗pg− 2F for the incumbent firm,

and Π∗E = Pg∗ ∗ Q∗g − F for the entrant firm. In this scenario, do not forget

that the profits of the incumbent will incorporate both the brand drug and the pseudo-generic variety. These calculations can be found in the Appendix 7.1.

5.2.1

Restriction on Parameter Values

Even though these restrictions are very similar to before, in a sense that most of their nature is the same, there are a few important changes and modifica-tions in genre that allow the model to hold in equilibrium, while all variables and restrictions still apply.

There is an indifferent consumer location in [0;1/2], and another located in [1/2;1].

The steps are quite similar the ones done before. However, since we have one more indifferent consumer, we have to make sure their locations in equilibrium are such that allows the equilibrium to hold. What changes this part is the fact that we are considering a pseudo-generic located in between the two other drugs, hence the distinction in the intervals we have to consider. For this case, we need

to have0 < Cg,pg < 12 and 12 < Cb,pg < 1.

The first restriction, leads to the following limits of the price cap P :

4(β − γ) − 7t

8α < P <

4(β − γ) + 15t

8α (5.29)

The second restriction lead to the following limits: 14(β − γ) + 3t

6α < P <

7(β − γ + t)

5

THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

5.2With PG

Non-negative utility of drug consumption.

Now, we need to ensure that no consumer will have negative utility when

consuming any drug, which is satisfied ifβ − αP > 0. This inequality holds for

allP ≤ 17t+6(β−γ)12α , if:

β > 17

6 t − γ (5.31)

Generic varieties yield higher utilities than the branded variety.

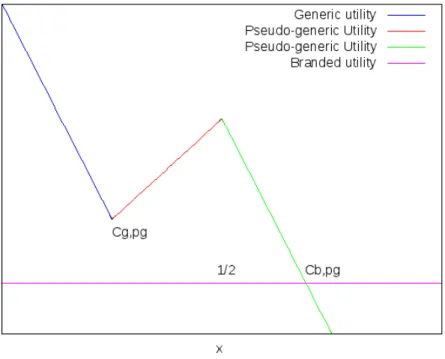

All consumers that choose a generic variety must derive a higher utility from this than from choosing the branded variety. If this assumption does not hold, then no consumer would buy the generic varieties. Figure 1 is a graphical inter-pretation of the problem and allows us to understand this concept more clearly.

Figure 1: Graphical representation of the consumers’ utilities.

Therefore, this restriction means thatγ − αPg − tCg,pg > β − αPb, which

is satisfied if51

51For price-caps lower than the limit given in (5.32), the brand-name firm can potentially reduce the price such

that the consumer located atCg,pgis just indifferent between the generic and the brand-name drug. However, it

can be shown that this strategy is not profitable if the fixed cost of the pseudo-generic drug is sufficiently high, and we will therefore exclude this as a potential equilibrium.

5.2

With PG

5THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

P > 21t + 32(β − γ)

20α (5.32)

The price cap binds in equilibrium.

The final restriction imposes a maximum value on the price cap, given by:

P < 17t + 6(β − γ)

12α (5.33)

Finally, combining all the above restrictions in one single interval, we find that: max n 4(β−γ)−7t 8α ; 14(β−γ)+3t 6α ; 21t+32(β−γ) 20α o < P < < min n 4(β−γ)+15t 8α ; 7(β−γ+t) 3α ; 17t+6(β−γ) 12α o and β > 176 t − γ.

The remaining work is to find the values that restrain the limit to two precise

intervals of values. First of all, 17t+6(β−γ)12α > 21t+32(β−γ)20α , if β < 13t + γ and

17t+6(β−γ)

12α >

14(β−γ)+3t

6α , if β <

1

2t + γ. Therefore, the maximum boundary

of the price cap is higher than all values of the lower limit if β < 13t + γ.

Furthermore, 14(β−γ)+3t6α < 21t+32(β−γ)20α , forβ < 13t + γ. Hence, we can reduce

the parameter restriction that holds this equilibrium to: 21t + 32(β − γ) 20α < P < 17t + 6(β − γ) 12α (5.34) and 17 6 t − γ < β < 1 3t + γ (5.35)

5

THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

5.3Equilibrium market structure

5.3

Equilibrium market structure

The first obvious notice is that the left interval that the price cap can assume if the incumbent firm releases a pseudo generic is higher than the maximum value that the price cap can assume, if the incumbent firm does not release a pseudo-generic drug. More formally:

21t + 32(β − γ)

20α >

2t + β − γ

3α (5.36)

This means the parameter set for which both equilibria exist, is empty. In other words, the equilibria with and without a pseudo-generic cannot co-exist.

If we endogenise the market structure, and if we, for the time being, omit from the fixed costs, we can identify the following equilibria:

1. If EQ 5.34 holds, the equilibrium is three drugs and the price cap binds in

equilibrium;

2. If 2t+β−γ3α < P < 21t+32(β−γ)20α holds, the equilibrium structure is two drugs and the price cap does not bind;

3. If EQ. 5.17 holds, there are only two drugs available, and the price cap binds

in equilibrium;

4. If 0 < P < (β−γ)α holds, the equilibrium is one only drug (the branded)

and the price cap binds in equilibrium.

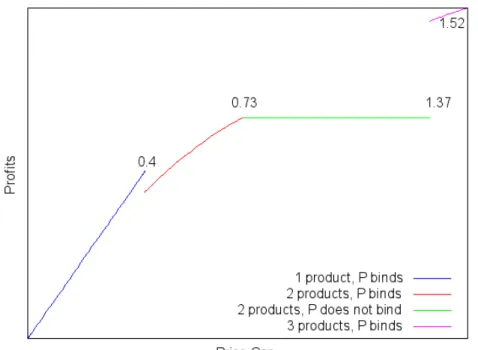

This set of restrictions will lead to a similar graphical interpretation to the one on Figure 2, where the thresholds can be found in an ascendant order. Another important aspect to highlight from the model is how the profits of the firms behave

under the many different scenarios52. A significant note is that when firms do not

face any regulation mechanism, profits (as well as prices) will be constant and there is no other variable in this model that can yield a different Nash Equilibria.

52These expressions are heavily involving. For that reason, you can find them in the Appendix 7.1, even though

5.4

Reference Pricing Scheme

5THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

Figure 2: Price cap thresholds

At this point, it is clear that price cap regulation can have two kinds of effects on competition. If applied too severely, it can have an anticompetitive effect, by reducing the incentives of independent generic firms to have their product on the market. On the other hand, assuming that the regulator wants to decrease the average price of drugs, then a certain level of the price cap is sufficient to reduce the incentives of brand-name firms to have a pseudo-generic on the market.

Since Rodrigues et al. (2014) and (2015) have analyzed the equilibria with reference pricing, there is a possibility to analyze the results obtained above with reference pricing.

5.4

Reference Pricing Scheme

Even though most of the outcomes can be retrieved from Rodrigues et al. (2015) work, where they investigated the effects of pseudo-generics, the compar-ison is if reference pricing can reduce the incentive level of brand-name firms to release a pseudo-generic as well.

It is important to recall the definition of reference pricing that we previously got from the literature. Under a reference price scheme, the effective prices are

5

THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

5.4Reference Pricing Scheme

theoretically given by:

P i = αPi if Pi ≤ Pr αPr+ (Pi − Pr) if Pi > Pr

In this model, we defined the prices as Pb > Ppg > Pg. Assuming that a

possible reference price would be binding for the cheapest drug on the market, then the consumer utility of purchasing one of those drugs is:

CSi =

γ − αPg − t ∗ Ci , if the consumer buys g

γ − αPg − (Ppg− Pg) − t ∗ |12 − Ci| , if the consumer buys pg

β − αPg + (Pb − Pg) , if the consumer buys b

(5.37)

The main change from this sub-model to the one presented in the previous sections, is that, now, the co-payment rate is not a fixed rate.

Taking in consideration the same assumptions as we did for the rest of the section 5, we can calculate the equilibria for the different scenarions.

5.4.1

First scenario: I does not sell PG

Considering EQ. 5.37, it is straightforward to show that the indifferent con-sumer between a branded and a generic variety is:

Cb,g =

Pb − Pg − (β − γ)

t (5.38)

From there, we can repeat the same line of thought that was used to calcu-late all equilibria before. Hence, the equilibrium quantities and prices, for this

scenario, are as follows53:

5.4

Reference Pricing Scheme

5THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

Pg∗ = t + (β − γ) 3 (5.39) and Pb∗ = 2t + (β − γ) 3 (5.40)Equilibrium quantities are then:

G∗ = 1 3 − 1 3t(β − γ) (5.41) and B∗ = 2 3 + 1 3t(β − γ) (5.42)

At this stage, we can notice that these results are exactly the same as in

section 5.1 ifα = 1.

Furthermore we need to find the range of values that allow the equilibrium to exist.

Restriction on Parameter Values

First of all, the indifferent consumer must be located somewhere in the Hotelling

line. More formally, 0 < Cb,g < 1. Considering that, in equilibrium, Cb,g =

1

3 −

(β−γ)

t ,Cb,g < 1 is always true and Cb,g > 0 is true if β < t + γ.

Secondly, to guarantee that all consumers have non-negative surplus, then

β ≥ αPg−(Pb−Pg) (the price of the branded), which is true if β ≥ t−γ(2−α1−α).

These restrictions are the similar to the equivalent ones obtained in Rodrigues

et al. (2014), ifα = 1, once again.

Thus, for this equilibrium to hold, then:

t − γ(2 − α

1 − α) < β < t + γ (5.43)

5.4.2

Second scenario: I sells PG

5

THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

5.4Reference Pricing Scheme

drug, our model is a special case of Rodrigues et al. (2015), since we assume

that the pseudo-generic drug is located at 12.

In order to keep the analysis simpler, we assumed a specific location for the pseudo-generic - See Section 5. To keep the analysis consistent, the same as-sumption has to be considered for this part of the calculations. Therefore, main-taining all assumptions that were considered before, we find the indifferent con-sumers locations for this scenario as follows (using the utility functions repre-sented in EQ. 5.37): Cg,pg = 14 + (Ppg−Pg) 2t Cb,pg = 12 − (β−γ)+(Pb−Ppg) t (5.44)

From there, repeating the same steps that were done repeatedly in all other scenarios, we find the respective equilibrium prices and quantities as:

Pg∗ = 13(β − γ) − 6t Ppg∗ = 56t − 23(β − γ) Pb∗ = 16(β − γ) − 56t (5.45)

And then, quantities: G∗ = (β−γ)2t − 1 4 P G∗ = 125 − 1 3t(β − γ) B∗ = 56 − (β−γ)6t (5.46)

Due to the complexity of the formulas, the profit expressions will be explored in the Appendix section, under Appendix 7.4.

The next step requires us to calculate the limits of the variables that allow this equilibrium to exist.

Restriction on Parameter Values

In this complex approach, in order to validate the equilibrium, certain conditions for these parameters must be imposed.

5.4

Reference Pricing Scheme

5THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

We need to ensure that 0 < Cg,pg < 12 and 12 < Cb,pg < 1, that no drug

provides negative surplus -β −

h

αPg+(Pb−Pg)

i

> 0 and that generic varieties provide higher utility than the branded for those consumers who purchase the

generic drug. More formally: γ − αPg − tCg,pg > β − αPb

Consider that, in equilibrium, Cg,pg = (β−γ)2t − 14 and Cb,pg = 16 − (β−γ)6t .

The first condition (0 < Cg,pg < 12) is true if 12t − y < β < 32t + γ. The second

condition (12 < Cb,pg < 1) is true if −7t − γ < β < γ + 2t. Since β and γ

cannot be negative, then the second conditions means that0 < β < γ + 2t.

No drug provides negative surplus to consumers if β − α

h (β−γ) 3 − t 6 i − h (β−γ) 6t − 5 6 − (β−γ) 3 − t 6 i

≥ 0, but this expression is less restrictive54 than the

respective one calculated for the previous scenario.

Finally,γ − αPg − tCg,pg > β − αPg − (Pb − Pg) holds if β < γ−14t.

With this last calculation, we then can narrow the range of values that the

parameterβ can assume, by combining all previous results and retrieve the

max-imum of the lowest value, and the minmax-imum of the highest value. Hence, we find that: max n 0 ; 1 2t−γ ; t−γ( 2 − α 1 − α) o < β < min n γ−1 4t ; γ+2t ; 3 2t+γ ; t+γ o (5.47)

With those limits, the set of values that hold both equilibria (with and without a pseudo-generic drug) is the following:

max nt 2 − γ; t − γ( 2 − α 1 − α) o < β < γ − t 4 (5.48)

The first conclusion we take out of the analysis so far is that, if EQ. 5.48 is satisfied, reference pricing will not force any drug out of the market. Therefore, reference pricing is less capable of reducing the brand-name firm’s incentive level to release a pseudo-generic.

54The inequality leads toβ < γ−2γα−tα−4t

7−2α . This expression is less decreasing thanβ ≥ t − γ( 2−α 1−α).

5

THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

5.5The Effects of Regulation

5.5

The Effects of Regulation

There are a few studies we can run about underlying topics to the previous analysis, which will enrich the conclusions we can take out of the model. Due to the complexity of the expressions, it is better to pursue the analysis with a numerical example, that fits under all assumptions and conclusions. It also lets us have some graphical representations which enrich the rest of the analysis.

Consider the following set of restrictions presented on table 1. Fixed Variables β 1.1 γ 1 α 0.5 t 0.5 F 0.01

Table 1: Numerical example: Values attributed to the variables.

Considering the above values, the minimum and maximum values that the price cap can assume are showed in Table 2, taking into consideration all the previous results from the model.

Minimum and Maximum values that the price cap can assume Without PG on the market

min <P < max

Formula β−γα 2t+β−γ3α

Numerical Example 0.2 0.73

With PG on the market

min <P < max

Formula 21t+32(β−γ)20α 17t+6(β−γ)12α

Numerical Example 1.37 1.52

Table 2: Minimum and maximum values that the price cap can assume in equilibrium.

The first important plot to show is how the average price of the market behaves in regard to the many levels of the price cap., representing the total pharmaceu-tical expenditures of that given market. If we use the average price expressions

5.5

The Effects of Regulation

5THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

(which you can find in the Appendix 7.2) and compare them with the price cap

threshold intervals, we find something similar to Figure 355.

Figure 3: Average price in order to the price cap values.

If we take in consideration Figure 3, the most relevant result for policy makers is that price cap regulation can cause two major effects on the market - one that is productive, another that is anticompetitive. Considering that the objective of this tool is to reduce the pharmaceutical expenditures of consumers, then any price cap value below the threshold of 1.37 (in this numerical example) can drive the pseudo-generic drug out of the market, leading to inferior average prices. However, if the regulated price is set below 0.4, the policy has an anticompetitive effect by driving the generic drug out of the market. In this case, stricter price regulation (reducing the price cap from above to below 0.4) could lead to higher average drug prices.

Even though there is no welfare analysis56, this analysis, supported by Figure

55The numerical values of the price cap thresholds in Figure 3 correspond to the thresholds reported in Section

5.3, with one exception. By assuming a positive fixed cost, F=0.01, the lowest price-cap threshold is determined by a zero-profit condition for the generic producer.

56Due to the complexity of drug definition and how people perceive them, which are not that relevant for the

regulator - See Cabrales, A. (2003), the welfare analysis can become very complex and some other authors - like Brekke et al. (2009) - have concluded that a static welfare is not enough. It needs to consider lots of information, such

5

THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

5.5The Effects of Regulation

3, allows us to observe how much people are spending on average, although we cannot say which situation is optimal to consumers.

Also, an important adjunct piece of information is how the firms’ profits be-have, in regard to the price cap - Figure 4 shows the incumbent’s profits, while Figure 5 shows the entrant’s profits. As we can see, both firms have profit func-tions that depend negatively on the price cap. This means that stricter regulation decreases the firms’ profits. However, it seems important to notice that softer

lev-els of regulation (that is, aP closer to the maximum value it can assume) provide

a higher level of profits to the entrant firm, even though many authors concluded that the pseudo-generic drug causes anticompetitive effects in the market.

Figure 4: Incumbents profits, in order to the price cap.

Fixed costs have been considered all along, even though they do not play a fundamental role in the price setting phase. In fact, they have no impact in the price definition, demand or average price. They do change the price cap

thresholds. If we considered a fixed cost of 0, the lowest price cap threshold

would be0.2. As seen in Figure 3, fixed costs will increase that threshold to 0.4.

as innovation incentives, firms’ profits and pharmaceutical expenditures. Perhaps an immediate effect of regulation may not be the best option for consumers but, in the long run, it will produce significant benefits.