ARTIGO ORIGINAL

RESUMO

Introdução: A apneia obstrutiva do sono é uma entidade clínica que condiciona aumento da morbimortalidade e estima-se que exista um elevado subdiagnóstico. Foi objetivo deste estudo avaliar o risco de apneia obstrutiva do sono não diagnosticada em indivíduos obesos.

Material e Métodos: Estudo transversal descritivo e analítico; durante um período de 11 meses foi avaliado o risco de apneia obstruti-va do sono aplicando o questionário STOP-Bang a todos os indivíduos com idade ≥ 18 anos e índice de massa corporal ≥ 30 kg/m2 que

frequentaram uma unidade de saúde familiar, sem o diagnóstico de apneia obstrutiva do sono e que aceitaram participar; considerou--se risco de apneia obstrutiva do sono não diagnosticada para score STOP-Bang ≥ 3.

Resultados: Foi avaliado o risco de apneia obstrutiva do sono não diagnosticada em 888 indivíduos (59,3% do género feminino), com idade média de 59,6 ± 14,68 anos e índice de massa corporal médio de 33,6 ± 3,43 kg/m2; o score STOP-Bang médio foi de 3,5

± 1,74, 70,9% apresentaram score ≥ 3; a frequência de todos os parâmetros do questionário STOP-Bang foi superior (p < 0,004) no grupo com score ≥ 3.

Discussão: A população estudada é uma das principais forças, pois é nas pessoas obesas que a incidência dessa doença é maior. Existem algumas limitações relacionadas com a amostra ser de uma única unidade de saúde, bem como o seguimento dos pacientes ser por doenças relacionadas com a apneia obstrutiva do sono.

Conclusão: O subdiagnóstico da apneia obstrutiva do sono nos indivíduos obesos pode ser muito elevado e uma grande parte destes pode apresentar doença moderada a grave; os médicos de Medicina Geral e Familiar podem ter um papel muito importante no rastreio e diagnóstico.

Palavras-chave: Apneia Obstrutiva do Sono/diagnóstico; Cuidados de Saúde Primários; Inquéritos e Questionários; Obesidade; Por-tugal

Undiagnosed Risk of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Obese

Individuals in a Primary Health Care Context

Risco de Apneia Obstrutiva do Sono Não Diagnosticada

em Indivíduos Obesos no Contexto dos Cuidados de Saúde

Primários

1. Unidade de Saúde Familiar Corgo. Agrupamento Centro de Saúde Douro I - Marão e Douro Norte. Administração Regional de Saúde do Norte. Vila Real. Portugal. Autor correspondente: Jaime Pimenta Ribeiro. jaime.pim.ribeiro@gmail.com

Recebido: 13 de maio de 2019 - Aceite: 26 de agosto de 2019 | Copyright © Ordem dos Médicos 2020

Jaime Pimenta RIBEIRO1, Adão ARAÚJO1, Cláudia VIEIRA1, Filipe VASCONCELOS1, Pedro Marques PINTO1, Benedita SEIXAS1, Bruno CERCA1, Isabel BORGES1

Acta Med Port 2020 Mar;33(3):161-165 ▪ https://doi.org/10.20344/amp.12319 ABSTRACT

Introduction: Obstructive sleep apnea is a clinical entity that is associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality and it is estimated that it is significantly undiagnosed. The objective of this study was to assess the risk of undiagnosed obstructive sleep apneain obese individuals.

Material and Methods: A descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study; the risk of obstructive sleep apnea’s was assessed over a period of 11 months by applying the STOP-Bang questionnaire to all individuals who attended a family health unit who were aged ≥ 18 years and had body mass index of ≥ 30 kg/m2 and who had not yet been diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea and agreed to

participate; the risk of an undiagnosed moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea was considered for any STOP-Bang score of ≥ 3. Results: The risk of undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea was assessed in 888 individuals (59.3% females) with an average age of 59.6 ± 14.68 years and a mean body mass index 33.6 ± 3.43 kg/m2; the mean STOP-Bang score was 3.5 ± 1.74, 70.9% scored ≥ 3; the

frequency of all STOP-Bang questionnaire parameters was higher (p < 0.004) within the group with score ≥ 3.

Discussion: The studied population is one of the main strengths, since it is in obese people that the incidence of this disease is higher. There are some limitations related to this sample coming from a single family health unit, as well as the patients’ follow-up being carried out throughout routine appointments for diseases that are closely related with obstructive sleep apnea.

Conclusion: The level of underdiagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea’s in obese individuals can be significantly high and a large proportion of them may have the disease at a moderate to severe stage; Family Physicians can have a very important role in screening and diagnosis.

Keywords: Obesity; Portugal; Primary Health Care; Sleep Apnea, Obstructive/diagnosis; Surveys and Questionnaires

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a clinical entity char-acterized by recurrent episodes of apnea and/or hypopnea during sleep, it occurs due to the total or partial collapse of the upper airway tract,1,2 which is associated with an in-crease in morbidity and mortality related to cardiovascular and neurovascular diseases, metabolic disorders and

neu-rocognitive functions. It may also increase the risk of occu-pational and driving accidents, as well as decrease labor’s productivity as a consequence of daytime sleepiness and impaired neurocognitive abilities.1,3-6

The main metric for diagnosing OSA is the apnea hy-popnea index (AHI). This reflects the number of significant

ARTIGO ORIGINAL events recorded per hour of sleep and is measured during some form of polysomnography. Several definitions of hy-popnea exist and can lead to different apnea–hypopnoea index scores between medical centres,2,7 although it is generally accepted that there is a breathing sleep-disorder when AHI is greater than five events per hour.4

The prevalence of this condition is high and it is thought to be highly underdiagnosed.1,8,9 A systematic review car-ried out in 2016 by Senaratna et al2 shows a prevalence in the general population of 9% to 38%. However, it is es-timated that the proportion of patients not diagnosed with OSA may be around 80%.1,9,10 In a study of 2121 individuals from Switzerland, it was concluded that if the most recent definitions for respiratory events and diagnostic techniques are commonly used, it is possible to note that almost every individual had some degree of breathing sleep-disorder.4 In Portugal, the real prevalence of OSA is still unknown.11 One of the best documented risk factors for this disease is obesity, with a high prevalence of OSA in obese individuals, as well as, a high prevalence of obesity in individuals with OSA, even though OSA may also be common in non-obese individuals.1,7,12-14

The gold standard method of OSA is polysomnography. However, it is a method with very high associated costs and limited accessibility,9,15 especially in countries with limited resources such as Portugal. As such, screening methods are being developed with the goal of adequately identify in-dividuals at higher risk of OSA.16,17 The STOP-Bang ques-tionnaire (Chung et al, 2008) is one of the latest OSA risk screening tools, is simple, objective and easy to apply, and is translated and validated for the Portuguese population, both at the level of sleep clinics and primary health care (PHC); it has demonstrated a high performance in the strati-fication of patients with suspicion and diagnosis of OSA.10,18 Given the high underdiagnosis and the epidemiological link between OSA and obesity, as well as the high preva-lence of obesity in Portugal,19 it is important to screen the risk of undiagnosed OSA in obese individuals, to be able to improve the diagnosis and treatment of this disease in this risk group, especially in the case of undiagnosed patients with moderate to severe disease.

MATERIAL AND METHODS Type of study

Cross-sectional, descriptive and analytical

Participants and study design

During an 11 month period, from February to December 2017, all individuals aged ≥ 18 years and body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2 who attended the family health unit (FHU) were invited to take part in the study. Those who were al-ready diagnosed and those who refused to participate or were unable to communicate were excluded.

In total, 983 individuals were invited, 72 (7.3%) were excluded for already having the diagnosis of OSA and 23 (2.3%) for not accepting to participate or for not being able to communicate.

The STOP-Bang questionnaire was applied to all indi-viduals who agreed to participate and data on gender, age, cervical perimeter and BMI was collected, in order to obtain all the parameters of the STOP-Bang questionnaire18 and calculate the risk score; the researchers did not interfere in the participants’ interpretation of the STOP-Bang ques-tionnaire. The risk score was calculated using the sum of the “yes” answers (8 parameters), with each answer “yes” being equal to 1 point, totaling a minimum score of 0 and maximum of 8; undiagnosed OSA was considered when the risk score was ≥ 3, moderate risk was considered when the risk scores was between 3 to 4 and high risk was consid-ered when the risk score was ≥ 5.9,10 The STOP-Bang score cutoff was set at 4, because of better accuracy in the obese population, according with Chung et al.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Northern Portugal’s Regional Health Administration. Both the original author of the questionnaire (Chung et al 2008) and the team who translated and validated the translation for the Portuguese population (Reis et al 2015) gave per-mission to use the questionnaire (Appendix 1: https://www. actamedicaportuguesa.com/revista/index.php/amp/article/ view/12319/Appendix_01.pdf).

All individuals who agreed to participate provided writ-ten informed consent. The individuals who presented a risk of undiagnosed moderate to severe OSA, were referred to their family doctor, with their consent.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive and inferential analysis was performed us-ing the SPPSS® 22.0 software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). For the characterization of the continuous variables the mean was used as a measure of central ten-dency and the standard deviation as a measure of disper-sion; the percentage / frequency and 95% confidence inter-val (95% CI) (calculated using bootstrapping) were used to characterize the categorical variables. For the comparisons between the no-risk group of undiagnosed OSA (score < 3) and the group with risk of undiagnosed moderate to se-vere OSA (score ≥ 3) different statistical tests were used: student’s t-test for means and chi-squared test for propor-tions, and the significance threshold was set at p < 0.004 (determined through the Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons).

RESULTS

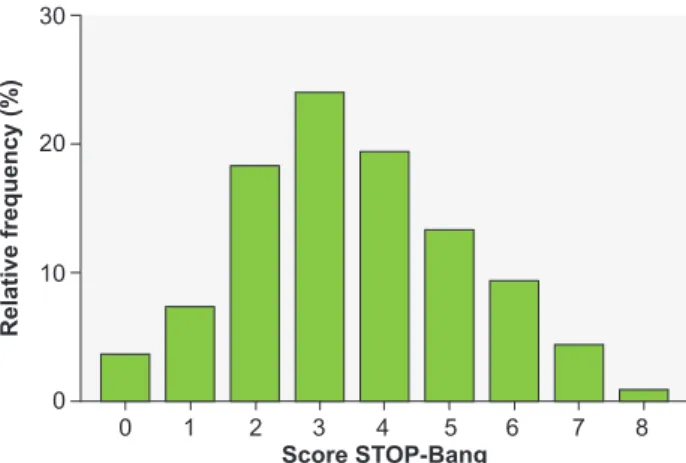

The sample was obtained from 888 individuals, of whom 59.3% were female and 40.7% were male, with an average age of 59.6 ± 14.68 years and a mean BMI of 33.6 ± 3.43 kg/m2. The mean STOP-Bang score was 3.5 ± 1.74, and the majority of the individuals had a score of 3 (23.9%), 4 (19.3%) and 2 (18.1%); the distribution of the frequency of individuals by STOP-Bang scores is detailed in Fig. 1. The proportion of individuals with a STOP-Bang score ≥ 3 (risk of undiagnosed moderate to severe OSA) was 70.9% (95% CI: 67.9% - 73.9%), 43.1% had a score of 3 to 4 (intermediate risk) and 27.8% presented score ≥ 5 (high

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

risk); within the group of individuals with STOP-Bang score ≥ 3 (risk of undiagnosed moderate to severe OSA), 60.8% presented a score of 3 to 4 (intermediate risk) and 39.2% presented a score ≥ 5 (high risk).

The proportion of individuals with a STOP-Bang score ≥ 4 was 47.1%.

Table 1 shows the frequencies of the different param-eters that make up the STOP-Bang questionnaire in rela-tion to the total group of individuals, the group of individuals with score < 3 and the group with score ≥ 3; as well as the p-value of the statistical tests used for comparison between both groups. The frequency of all parameters in the com-parison of individuals with score < 3 and ≥ 3 was higher in individuals with a STOP-Bang score ≥ 3, with a statistically significant difference.

DISCUSSION

The proportion of adult obese individuals at risk of un-diagnosed moderate to severe OSA was very high (about 70%) and a significant portion, more than a quarter of the obese adult individuals, presented a high risk,

represent-ing a group of individuals with probable undiagnosed mod-erate to severe disease and therefore untreated. All the parameters of the STOP-Bang questionnaire, including both those self-reported by individuals and those evaluated by researchers, were more frequent in the group with risk of undiagnosed moderate to severe OSA, and the minor differences were found in BMI, which may be related to the fact that all participants were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), even though the group of obese individuals at risk of undi-agnosed moderate to severe OSA (score ≥ 3) had slightly higher mean BMI and a higher proportion of obese individu-als with a BMI > 35 kg/m2, which suggests that even among obese individuals, the higher degree of obesity may contrib-ute to an increased risk of undiagnosed severity OSA. In Portugal, the real prevalence of OSA is unknown. However, a cross-sectional study on the prevalence of known and diagnosed OSA at PHC level, carried out in 2014 within the framework of the Sentinel Physicians Network, estimated a prevalence of 0.89% in the population aged 25 years or older.11 This represents a very low estimate compared to international reports about the prevalence of this disease.1-3,8 This may be a sign of underdiagnosis, as the authors themselves point out in the article, which is in agreement with the high risk of undiagnosed OSA found in this study and the underdiagnosis estimates mentioned in the scientific literature, which refer to about 80% of OSA cases.1,9,10

According to Chung et al, a STOP-Bang score cutoff of 4 gives a better balance of specificity and sensitivity com-pared with the cutoff of 3 (the specificity is lower) in the obese population.9 Even so, the proportion of individuals with a STOP – Bang Score ≥ 4 was 47.1%, showing that al-most half of individuals are at risk of undiagnosed moderate to severe OSA. However, the risk assessment tool validated for the Portuguese population and PHC only used the cutoff of 3 on the STOP-Bang score.

One of the strengths of this study is the fact that it has

Figure 1 – Distribution of individuals according to the STOP-Bang

questionnaire score Score STOP-Bang Relative frequency (%) 0 0 10 20 30 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Table 1 – Summary of the statistics of the sample studied and the comparison between groups of individuals with STOP-Bang score < 3 and ≥ 3

Total Score < 3 Score ≥ 3 (score < 3 vs score ≥ 3)p

n (%) 888 258 (29.1%) 630 (70.9%) Age (years) 59.6 ± 14.68 52.2 ± 16.68 62.6 ± 12.62 < 0.001* BMI (kg/m2) 33.6 ± 3.43 33.1 ± 2.92 33.8 ± 3.6 0.002* CP (cm) 39.2 ± 3.76 36.3 ± 2.42 40.4 ± 3.57 < 0.001* Snoring (%) 51.0% 21.7% 63.0% < 0.001** Tiredness (%) 34.5% 18.6% 41.0% < 0.001** Observed apnea (%) 23.5% 1.2% 32.7% < 0.001** High BP (%) 68.9% 37.6% 81.7% < 0.001** BMI > 35 kg/m2 (%) 25.6% 16.3% 29.4% < 0.001** Age > 50 years (%) 72.1% 44.6% 83.3% < 0.001** CP > 40 cm (%) 35.9% 2.7% 49.5% < 0.001** Male (%) 40.7% 7.4% 54.3% < 0.001** STOP-Bang score 3.52 ± 1.74 1.5 ± 0.71 4.4 ± 1.3 < 0.001*

ARTIGO ORIGINAL analyzed the risk of undiagnosed moderate to severe OSA in a group of individuals presenting one of the most well documented major risk factors for OSA such as obesity, whose prevalence in Portugal is very high, represent-ing about 22% of the Portuguese population,19 which has been increasing and following the worldwide trends.20 The achieved sample size is quite large which allows for a good robustness to the results of the study. Another strong point is the fact that it used a risk assessment tool that has been translated and validated for the Portuguese population, both in the sleep clinic and in PHC. This risk assessment

tool demonstrated a high performance in the stratification of patients with suspicion and diagnosis of OSA, with a high sensitivity and a high positive predictive value for OSA in patients with a STOP-Bang score ≥ 3, as well as a high negative predictive value for OSA in patients with a STOP-Bang score < 3, apart from allowing the categorization of the degree of risk, since this increases as the calculated score increases, in particular the risk of severe OSA.10,18,21 In terms of limitations, it should be noted that the study sample was a convenience sample and all participants were recruited in PHC which may introduce a selection bias, since these individuals may be attending PHCs units for having diseases that are closely related with OSA and which are given a lot of attention in PHC, such as hyperten-sion or diabetes mellitus, for example. This may lead to an overestimation of the risk of undiagnosed OSA in this group. Another limitation is the fact that only a single PHC unit pop-ulation has been studied, and thus it is not possible to make an extrapolation of the results to the national population of obese individuals. The STOP-Bang questionnaire itself also presents a limitation regarding its specificity level for scores ≥ 3 that is relatively low (53% according to Rebelo-Marques et al, 2018), but increases as the score calculated is high-er, with specificity above 80% for scores of score ≥ 5 and above 98% for scores ranging from 7 to 8.9,17,20

The high proportion of obese individuals at risk of un-diagnosed moderate to severe OSA may be explained by several factors. Although the real prevalence of this disease is still unknown, it is estimated that it is high, as there are well-documented risk factors such as obesity. The medical community may not be aware of its real magnitude and this factor may be related to the high level of underdiagnosis.11 An internationally published review on OSA screening and assessment in PHC published in 201522 concluded that the OSA screening model practiced in PHC is fragmented and ineffective and that many times PHC doctors find pa-tients with OSA symptoms but do not apply the screening, nor assess the risk of OSA or instead refer to secondary care, which is what may be also occurring in Portugal. Other factors may also probably contribute, such as the fact that sometimes the individual experiences of daytime sleepiness are not valued neither reported to the doctor23; the inexistent clinical guidelines about this screening; PHC doctors deal with many chronic and acute problems in their daily appoint-ments, limiting the time available for the implementation of screening; or the absence of a medical record module in the

electronic health record to carry out this assessment and registration.

The application of a systematic, uniform, efficient and user-friendly screening method to stratify the risk of undi-agnosed OSA such as the STOP-Bang questionnaire,16,21,24 in the main groups at risk for OSA, like those with obesity, hypertension or diabetes, may represent a very important improvement in the quality of patient assessment. There-fore, it would be possible to fight the insufficient response of secondary care, promoting the referral of patients with moderate to severe disease, in order to confirm the diagno-sis, as well as to begin the appropriate treatment. An impor-tant impact on reducing morbidity and mortality of diseases closely correlated with OSA1,14 and its associated costs is expected.5

The results of this study help to fill the gap of the lack of knowledge of the prevalence by estimating the risk of undiagnosed OSA in obese individuals, although only the risk of disease has been assessed, through the application of a screening tool, and the diagnosis and real prevalence have not been confirmed. However, there is a need to ex-tend this study in order to be able to reflect the national reality and to extend the study of the risk of undiagnosed OSA to other risk groups, so that the medical community, particularly PHC doctors, can become more aware of this problem. As such, it is important to carry out cost-effective-ness studies to establish standards of clinical guidelines addressed to groups at higher risk, allowing a reduction of underdiagnosis and the provision of treatment to those patients who need it. As an example, a cost-effectiveness study conducted in Japan in 2014 by Okubo et al showed good cost-effectiveness concerning the active screening of OSA in middle-aged men with diabetes or chronic kidney disease (CKD), and that led the authors to suggest the in-troduction of OSA screening in the guidelines for diabetes and CKD.25

CONCLUSION

The results of this study suggest that, even though obe-sity is recognized as one of the major risk factors for OSA, the underdiagnosis of OSA in obese individuals may be very high and that many may even present a risk of unrec-ognized moderate to severe disease. Consequently, these patients may end up not receiving treatment, with implica-tions in morbidity and mortality due to cardiovascular dis-eases closely related to OSA.

The real prevalence of OSA in Portugal is unknown, so there is a need to extend the study of the risk of undi-agnosed OSA to other at-risk groups, as well to carry out cost-effectiveness studies that may be useful for the devel-opment of clinical guidelines which allow the reduction of the underdiagnosis and providing treatment to patients with OSA.

The magnitude of this disease should be present in the minds of PHC doctors who may represent an essential pillar in the reduction of underdiagnosis, especially in the major risk groups, such as obese individuals.

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

PROTECTION OF HUMANS AND ANIMALS

All procedures performed in the study were in accord-ance with the ethical standards of the institutional and na-tional research committee (Ethics Committee of the Portu-guese Regional Health Administration of the North (ARS Norte)) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from all individual par-ticipants included in the study.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

FUNDING SOURCES

This research received no specific grant from any fund-ing agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sec-tors.

REFERENCES

1. Costa C, Santos B, Severino D, Cabanelas N, Peres M, Monteiro I, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: an important piece in the puzzle of cardiovascular risk factors. Clin Investig Arterioscler, 2015;27:256-63. 2. Senaratna C, Perret J, Lodge C, Lowe A, Campbell B, Matheson M, et

al. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;34:70-81.

3. Peppard P, Young T, Barnet J, Palta M, Hagen E, Hla K. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:1006-14.

4. Heinzer R, Vat S, Marques-Vidal P, Marti-Soler H, Andries D, Tobback N, et al. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in the general population: the HypnoLaus study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:310-18. 5. Watson N. Health care savings: the economic value of diagnostic

and therapeutic care for obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12:1075-7.

6. Olaithe M, Bucks R, Hillman D, Eastwood P. Cognitive deficits in obstructive sleep apnea: Insights from a meta-review and comparison with deficits observed in COPD, insomnia, and sleep deprivation. Sleep Med Rev. 2018; 38:39-49.

7. Jordan A, McSharry D, Malhotra A. Adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet. 2014;383:736-47.

8. Jennum P, Riha R. Epidemiology of sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome and sleep-disordered breathing. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:907-14. 9. Chung F, Abdullah H, Liao P. STOP-Bang Questionnaire: a practical

approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2016;149:631-8. 10. Rebelo-Marques A, Vicente C, Valentim B, Agostinho M, Pereira R,

Teixeira M. STOP-Bang questionnaire: the validation of a Portuguese version as a screening tool for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in primary care. Sleep Breath. 2018;22:757-65.

11. Rodrigues A, Pinto P, Nunes B, Barbara C. Obstructive sleep apnea: epidemiology and Portuguese patients profile. Rev Port Pneumol (2006). 2017;23:57-61.

12. Young T, Skatrud J, Peppard P. Risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea in adults. JAMA. 2004;291:2013-6.

13. Drager L, Lopes H, Maki-Nunes C, Trombetta I, Toschi-Dias E, Alves M, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea: a cardiometabolic risk in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:569-76.

14. Bauters F, Rietzschel E, Hertegonne K, Chirinos J. The link between

obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2016;18:1.

15. Chung F, Yang Y, Liao P. Predictive performance of the STOP-Bang score for identifying obstructive sleep apnea in obese patients. Obes Surg. 2013;23:2050-7.

16. Chiu H, Chen P, Chuang L, Chen N, Tu Y, Hsieh Y, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Berlin questionnaire, STOP-BANG, STOP, and Epworth sleepiness scale in detecting obstructive sleep apnea: a bivariate meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;36:57-70.

17. El-Sayed I. Comparison of four sleep questionnaires for screening obstructive sleep apnea. Egyptian J Chest Dis Tubercul. 2012;61:433-41.

18. Reis R, Teixeira F, Martins V, Sousa L, Batata L, Santos C, et al., Validation of a Portuguese version of the STOP-Bang questionnaire as a screening tool for obstructive sleep apnea: analysis in a sleep clinic. Rev Port Pneumol. 2015;21:61-8.

19. Oliveira A, Araujo J, Severo M, Correia D, Ramos E, Torres D. Prevalence of general and abdominal obesity in Portugal: comprehensive results from the National Food, nutrition and physical activity survey 2015-2016. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:614.

20. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. (NCD-RiscC) Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387:1377-96.

21. Nagappa M, Liao P, Wong J, Auckley D, Ramachandran S, Memtsoudis S, et al. Validation of the STOP-Bang Questionnaire as a screening tool for obstructive sleep apnea among different populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10: e0143697.

22. Miller J, Berger A. Screening and assessment for obstructive sleep apnea in primary care. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;29:41-51.

23. Bailes S, Baltzan M, Rizzo D, Fichten C, Grad R, Wolkove N, et al., Sleep disorder symptoms are common and unspoken in Canadian general practice. Fam Pract. 2009;26:294-300.

24. Ramachandran SK, Josephs LA. A meta-analysis of clinical screening tests for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:928-39. 25. Okubo R, Kondo M, Hoshi S, Yamagata K. Cost-effectiveness of

obstructive sleep apnea screening for patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease. Sleep Breath. 2015;19:1081-92.