www.jped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Relationship

between

chronological

and

bone

ages

and

pubertal

stage

of

breasts

with

bone

biomarkers

and

bone

mineral

density

in

adolescents

夽

Cristina

Maria

Teixeira

Fortes

a,

Tamara

Beres

Lederer

Goldberg

b,∗,

Cilmery

Suemi

Kurokawa

a,

Carla

Cristiani

Silva

c,

Maria

Regina

Moretto

a,

Talita

Poli

Biason

d,

Altamir

Santos

Teixeira

e,

Hélio

Rubens

de

Carvalho

Nunes

faClinicalandExperimentalPediatricsResearchCenter,DepartmentofPediatrics,BotucatuMedicalSchool,Universidade

EstadualPaulista(UNESP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

bDepartmentofPediatrics,AdolescentMedicineDiscipline,GraduatePrograminGynecology,Obstetrics,andMastology,

BotucatuMedicalSchool,UniversidadeEstadualPaulista(UNESP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

cDepartmentofPhysicalEducation,UniversidadeEstadualdoNortedoParaná(UENP),Paraná,PR,Brazil

dDepartmentofPediatrics,AdolescentMedicineDiscipline,BotucatuMedicalSchool,UniversidadeEstadualPaulista(UNESP),

SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

eTropicalDiseasesandImageDiagnosisDepartment,BotucatuMedicalSchool,UniversidadeEstadualPaulista(UNESP),SãoPaulo,

SP,Brazil

fBotucatuMedicalSchool,UniversidadeEstadualPaulista(UNESP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

Received27December2013;accepted3April2014 Availableonline14July2014

KEYWORDS

Adolescents;

Bonemineraldensity; Bonemineralization; Boneremodeling; Bonereabsorption; Osteocalcin; Osteoporosis; Growth; Bonehealth

Abstract

Objective: Tostudybonemineraldensity(BMD)inadolescentfemalesaccordingtofivegroups ofchronologicalage(CA),boneage(BA),andbreastdevelopmentstage(B),andtocorrelate theseparameterswithplasmabonebiomarkers(BB).

Methods: This was a cross-sectional study performed in 101 healthy adolescent females between10and20yearsold.Thestudyvariableswere:weight,height,bodymassindex(BMI), CA,B,BA,calciumintake,BMD,andBB.Osteocalcin(OC),bonealkalinephosphatase(BAP), andC-terminaltelopeptide(S-CTx)wereevaluatedforBB.BMDwasmeasuredusingdualenergy X-rayabsorptiometry(DXA).

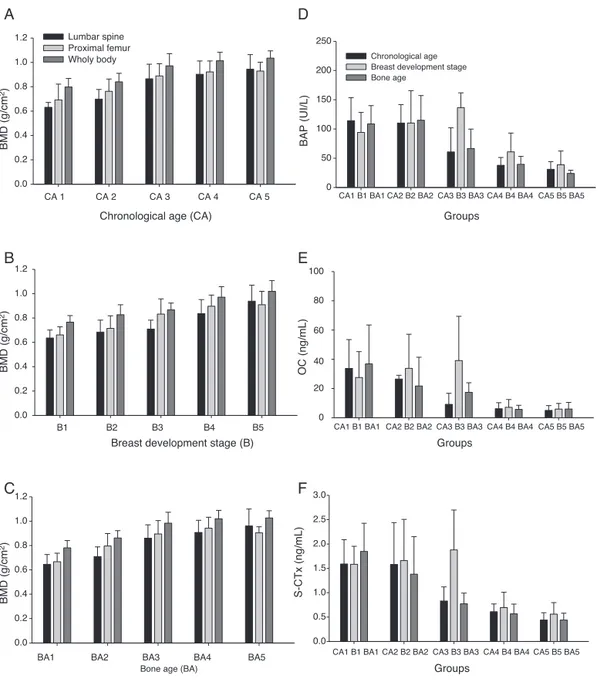

Results: BMDinlumbar spine, proximalfemur,and totalbody increasedwith age,andthe respectiveobservedaverageswere:inCA1(10yearsold),0.631,0.692,0.798g/cm2;inCA2 (11 to12 yearsold), 0.698,0.763, 0.840g/cm2; inCA3(13to 14 yearsold), 0.865,0.889,

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:FortesCM,GoldbergTB,KurokawaCS,SilvaCC,MorettoMR,BiasonTP,etal.Relationshipbetweenchronological andboneagesandpubertalstageofbreastswithbonebiomarkersandbonemineraldensityinadolescents.JPediatr(RioJ).2014;90:624---31.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:tamara@fmb.unesp.br(T.B.L.Goldberg).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2014.04.008

0.972g/cm2;inCA4(15to16yearsold),0.902,0.922,1.013g/cm2;andinCA5(17to19years old),0.944,0.929,1.35g/cm2.Theseresultsshowedsignificantdifferencesbetween13and14 yearsofage(CA3)orwhengirlsreachedtheB3stage(0.709,0.832,0.867g/cm2).Thehighest medianconcentrationsofBBwerebetween10and12yearsofagewhenadolescentswerein theB2---B3(p<0.001).MedianBBconcentrationsdecreasedinadvancedBAandB.

Conclusions: BBconcentrations werepositivelycorrelatedwiththepeakheightvelocityand negativelycorrelatedwithBMDinthestudysites.IncreasedBMDandBBconcentrationswere observedinB3.

©2014SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Adolescentes; Densidademineral óssea;

Mineralizac¸ãoóssea; Remodelac¸ãoóssea; Reabsorc¸ãoóssea; Osteocalcina; Osteoporose; Crescimento; Saúdeóssea

Relac¸ãoentreasidadescronológicaeósseaeoestágiopuberaldasmamascomos biomarcadoresósseoseadensidademineralósseaemadolescentes

Resumo

Objetivo: Avaliar a densidade mineral óssea (DMO) em adolescentes do sexo feminino de acordocom aidade cronológica (IC),idade óssea(IO) e desenvolvimentodas mamas(M)e suascorrelac¸õescombiomarcadoresderemodelac¸ãoósseaemplasma(BO).

Métodos: Estefoiumestudotransversalprospectivofeitoem101adolescentessaudáveisdo sexofemininocomidadeentre10e20anos.Asvariáveisestudadasforam:peso,altura,índice demassacorpórea(IMC),IC,IO,M,ingestãodecálcio,DMOeBO.Aosteocalcina(OC), fos-fatase alcalinaóssea (BAP)eotelopeptídeo Cterminal(S-CTx) foramosbiomarcadoresde remodelac¸ãoósseaavaliados.ADMOfoiobtidaporabsorciometriaderaios-Xdeduplaenergia (DXA).

Resultados: ADMO decolunalombar,fêmurproximalecorpototalaumentoucomaidade, easrespectivasmédiasobservadasforam:IC1=0,631,0.692,0,798g/cm2;IC2,0,698,0,763, 0,840g/cm2; IC3, 0,865, 0,889,0,972g/cm2;IC4, 0,902,0,922, 1,013g/cm2;e IC5, 0,944, 0,929,1,35g/cm2.Observou-sediferenc¸asignificativaentre13e14anos(IC3)ouquandoas meninasestavamemM3(0,709,0,832,0,867g/cm2).OsvaloresdosBOapresentaramelevac¸ão entre10e12anosequandoasadolescentesestavamemM2---M3(p<0,001).Osvaloresdas medianasdosBOdiminuíramcomoavanc¸ardaIOeM.

Conclusões: OsBOsmostraramparalelismocomopicodevelocidadedecrescimentoe demon-straramcorrelac¸ãonegativacomaDMOnosítiosavaliados.OaumentodaDMOedosBOsfoi observadoemM3.

©2014SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Todososdireitos reservados.

Introduction

The skeletonwas traditionally known as a passive organ; itsmajorfunctionwasconsideredtobethesupportofthe humanbody.However,itiscurrentlyconsideredamutable organthatparticipatesininteractionsbetween regulatory and energetic mechanismsacting in conjunction with the adiposetissue.1,2

Puberty is considered animportant timeof substantial

bonegrowth,andtherefore,sensitivetoexternalinfluences

that have strong effects, such as diet, physical exercise,

lifestyle,andmedications.3

Bonemetabolismischaracterizedbycyclesofformation

andreabsorption,andthebalancebetweenthesetwo

pro-cesseschangesthroughlife.Duringinfancyandadolescence,

boneformationpredominatesoverabsorption;inadultlife,

bothprocessesstabilize.4 Boneremodelingisalsostrongly

relatedtovariationsinbodyweight,5,6includingchangesin

muscle mass andbody fat content. Thus,the mechanical

loadimposedonthe skeletal system interferes withbone

formation.

AccordingtoHaeneyetal.,7peakbonemassrepresents

thehighestbonemassvalueormaximumquantityofbone

that an individual attains when their skeleton is totally

mineralizedor consolidated. Currently, it is not precisely

established at what age biological or chronological peak

bonemass occurs; thereis evidence thatit occursat the

endofadolescence.8

Bonemass depositionbegins during fetallife and

con-tinues during infancy and adolescence, stabilizing at the

beginningofadulthood.Understandingandevaluatingbone

mass acquisition in a population of adolescents could

be a determining factor in the prevention of

osteope-nia/osteoporosis, which are diseases considered public

healthissuesofhigheconomicimpact.9

Bonemineraldensity(BMD)isconsideredanimportant,

precise, and statically valid measurement; however, BMD

bonetissuehasundergone,representingonlyonemoment

inanevolvingcondition.Toovercomethislimitationandto

improvethesensitivityandspecificityofbonemassstatus

evaluation,theuseofbonebiomarkers(BBs)hasbeen

sug-gestedtoimprovetheunderstandingoftheboneremodeling

process.10---12

Importantserumbiomarkersofboneformationinclude:

a) osteocalcin (OC), a non-collagenous protein

abun-dantinbone,predominantlysynthesizedbydifferentiated

osteoblasts,andconsidered tobeasensitivebiomarkerof

bone synthesisactivity; and b) bone alkaline phosphatase

(BAP),anectoenzymeorspecificglycoproteinfoundonthe

surfaceof osteoblasts,withanimportantfunctioninbone

mineralization,andconsideredasahighlysensitiveand

spe-cificbone formation indicator.13 In addition, studies have

suggestedthattheC-terminaltelopeptide(S-CTx)fragment,

abone reabsorptionmarker,is agoodmarkertoevaluate

boneformationprocessesbecauseitisformedwhen

colla-gentypeIdegradationoccurs.

Bone remodeling biomarkers are important tools for

understanding the dynamics of bone metabolism and add

informationacquiredfrombonedensitometry.

Therefore,thiswasthefirststudythatevaluatedbone

mineral density (BMD) in Brazilian adolescent females

according to chronological age (CA), bone age (BA), and

breast developmentstage (B), correlating this parameter

withbonebiomarkers(BBs).

Methods

Healthywhiteadolescentfemales(non-Africanornon-Asian descendants)between10and20incompleteyearsoldwere invitedtoparticipateinthisstudy.Thevolunteerswere stu-dentsatthe LaSalleSchoolinBotucatu,SãoPaulo State, Brazil andSanta Marcelina Schoolin Botucatu.A total of 101out of 497 adolescentfemale students inthe studied agegroup,wereincluded inthestudy andparticipatedin allevaluations.

ThestudywasapprovedbytheBotucatuSchoolMedicine EthicsCommittee--- UNESP.Written informedconsentwas co-signed by each participant (101) and their parents or guardians.

Theinclusioncriteriacomprisedweighbetweenthe10th and90thpercentilesandheightbetweenthe10thand97.5th percentilesforeachagegroup,14adequatebodymassindex

(BMI)forage,15andreportofregularanddailyconsumption

ofdairyproducts.

Theexclusioncriteriawere:historyofprematurityorlow

birthweight;presenceofdiabetesmellitus;acuteorchronic

under-nourishment;congenitalor acquired bone diseases;

gastrointestinal diseases accompanied by malabsorption;

historyof nephropathywithor without chronic renal

fail-ure;endocrinopathies;early orlatepuberty;chronicdrug

consumption;cystic fibrosis; celiacdisease;drug usethat

negativelyaffected bone metabolism (suchas

anticonvul-sants and antacids with aluminum); more than 2h/week

physicalexercises,sinceexcessivephysicalexercise

inter-feres with bone mineralization; use of contraceptives 24

monthspriortodatacollection;pregnancyatanytime;and

absenceondatesassignedforthestudydatacollection.The

dietaryexclusioncriteriawere:practicesofanexclusively

vegetariandietandhigh fiberdiet;caffeineconsumption;

softdrinkconsumptionover300mL/day;andlack ofdairy

productconsumption.Theserigorousselectioncriteriawere

appliedinordertominimizeinterferencefromfactorsthat

couldaffectnormalbonemetabolismduringpuberty.

Based on the inclusion criteria, eligible adolescents

were invited to have their weight and height measured.

Thoseparticipantsfittingtheparametercriteriawere

subse-quentlyquestionedaboutsmokingandalcoholconsumption.

Selectedadolescentswereinvitedtoparticipateinthestudy

asvolunteers;afullexplanationofmethodsandprocedures

wasprovidedtoparticipantsandtheirparentsorguardians,

includinginformationabouttheoptiontowithdrawfromthe

studyatanytime.

Parentsandguardianswereinterviewedandparticipants

underwent general and specific physical examinationsfor

detection of any physical abnormality (adolescents with

chronic congenitalinfectionand majorcongenital

anoma-lies)thatcouldinterferewiththestudy expectedresults.

Secondarysexualcharacteristicswereevaluatedandresults

comparedtotheTannercriteriaforbreastdevelopment(B).

The averageage atmenarche inthegroupof participants

wassimilartothatinthe Brazilianpopulation (12.2years

old).16Skeletalmaturationwasevaluatedbythe

determina-tionofboneage(BA)accordingtotheGPmethoddescribed

by Greulich and Pyle.17 The parameters of chronological

age(CA),boneage,andpubertalstageofbreasts(B)were

dividedintofivegroups.GroupCA1wascomposedoffemales

aged10years;CA2,ages11and12years;CA3,ages13and

14 years;CA4, ages15and16 years;andCA5,ages17to

20incompleteyears.TheBAgroupsweredividedintoBA1:

bone age (BA) 10and 11years;BA2:BA 12and 13years;

BA3:BA14and15years;BA4:BA16and17years;andBA

5:BA18and19years.Dietarycharacterizationwas

subse-quentlymeasuredusinganon-consecutivethree-daydietary

record.18 Questionnaires for centesimal quantification of

food wereapplied andanalyzed usinga computersystem

developedbytheDepartmentofNutritionattheSchoolof

PublicHealthfromtheUniversidadedeSãoPaulo.19

Participants whocompleted allinitial steps underwent

bone mass evaluationusing abone densitometry unitand

by attenuationofdualenergyX-ray (DXA)usingaHologic

QDR2000-Plus(HologicInc.,Waltham,MA,USA)according

torecommendationsoftheInternational Societyfor

Clini-calDensitometry.20 BMD resultswere expressedin g/cm2.

Measurements fromthe L1---L4lumbar spinal region,total

proximalfemur(includingthefemurneck,trochanteric,and

intertrochantericregions),Wardarea,andwholebody

den-sitometry were taken. The amount of radiation to which

participants were exposed was considered safe and not

harmfultotheircurrentandfuturelife.20

Bloodcollection

Bloodsampleswerecollectedbyvenouspunctureand cen-trifuged by 15minutes at 1,500g for serum separation; serumsampleswerestoredat-70◦Cuntilanalysesof BAP

Table1 Meanandstandarddeviation(SD)ofnutritionalindicatorsandcalciumintakeaccordingtochronologicalage(CA), breastdevelopmentstage(B)andboneagegroups(BA).

Variables

Groups

Mean±SD(ntotal=101)

1 2 3 4 5

CA(years) (n=10) (n=19) (n=26) (n=27) (n=19)

Weight(kg) 35.38±7.2 42.90±7.36 49.39±7.02 52.33±5.39 53.46±7.62

Height(m) 1.39±0.07 1.50±0.08 1.59±0.05 1.60±0.05 1.61±0.04

BMI(kg/m2) 17.64

±2.27 18.92±2.59 19.26±2.10 20.39±1.77 20.44±2.32

Calcium(mg/day) 652±176 624±271 533±150 490±153 532±267

B (n=5) (n=7) (n11) (n=37) (n=41)

Weight(kg) 31.92±4.7 39.18±5.56 45.75±7.98 50.31±7.46 51.69±6.04

Height(m) 1.38±0.05 1.43±0.08 1.54±0.09 1.60±0.06 1.59±0.05

BMI(kg/m2) 16.24±1.62 19.02±2.84 18.81±2.18 19.59±2.18 20.31±1.91

BA (n=9) (n=14) (n=21) (n=31) (n=26)

Weight(kg) 33.02±4.4 45.20±5.73 48.92±6.68 53.46±5.46 49.31±12.6

Height(m) 1.38±0.05 1.52±0.06 1.59±0.05 1.60±0.05 1.52±0.37

BMI(kg/m2) 16.99

±1.57 19.26±2.58 19.24±2.17 20.78±1.73 18.88±4.62

Note:ANOVAfollowedbyStudent-NewmanKeuls. BMI,bodymassindex.

Chronologicalagegroups(yearsofage):CA1-10;CA2-11-12;CA3-13-14;CA4-15;CA5-17-19. Weight:CA1<CA4andCA5;CA2<CA4andCA5;p<0.001

Height:CA1<CA2,CA3,CA4andCA5;CA2<CA3,CA4andCA5;p<0.001 BMI:CA1<CA4andCA5;p<0.001

Calcium:p=0.407

Breastdevelopmentstagegroups(Tannercriteria)

Weight:B1<B3,B4andB5;p<0.001

Height:B1<B4andB5;B2<B4andB5;p<0.001 BMI:B1<B5;B1<B4;p<0.001

Boneagegroups(Greulich&Pyle):BA1-10-11years,BA2-12-13years,BA3-14-15years,BA4-16-17years,BA5-18-19years Weight:BA1<BA2,BA3,BA4andBA5;BA2<BA4andBA5;p<0.001

Height:BA1<BA3,BA4andBA5;BA2<BA3,BA4andBA5;p<0.001 BMI:BA1<BA4andBA5;p<0.001

S-CTxwasquantifiedbyanelectrochemiluminescenceassay using a commercial ß-Cross Laps/serum kit (Roche Diag-nosticCorporation,Indianapolis,IN,USA)andElecsys1010 (RocheDiagnosticCorporation, Indianapolis,IN, USA); the inter-assaycoefficientofvariationwas5%.

Statisticalanalysis

Descriptive statistics data were expressed as

mean±standard deviation using analysis of variance and the Student-Newman-Keuls method. Kruskal Wallis analysisofvarianceandtheDunntestwereperformedfor comparisonsbetween bone biomarkersandCA, BA, andB whentheShapiro-Wilktestshowednon-normaldistribution for thesedata. Spearmancoefficients of correlation were calculatedbetweenbonebiomarkersandBMDresultsinthe evaluatedlocationsandCA,BA,andB.Minimumstatistical differencewasconsideredat5%.Graphicalrepresentation

included mean DXA values and median bone biomarker

concentrationsinrelationtoCA,BA,andB.

Results

Weight,height,BMI,andBMD,measuredinthethree ana-lyzedsites,increasedwithage,pubertalstageofbreasts,

andboneage(Table1,andFig.1A-C).Theconcentrations

ofallboneformationandreabsorptionbiomarkers(BAP,OC,

and S-CTx) reduced with age; the highest concentrations

wereobserved inCA1andthelowestin CA5,whichisthe

latephaseofpuberty(Fig.1D-F).

Significantdifferencesinweightwereobservedbetween

agegroups(CA4andCA5differedfromgroupsCA1andCA2,

withp<0.01).

Calcium ingestion ranged from 489±153mg/day to

652±176mg/day;themean±SDforthewholesamplewas

566±210mg/day(Table1).

TheBMD(lumbarspine,proximalfemur,andtotalbody)

analysesshoweddifferencesingroups CA3,CA4,andCA5,

whichdifferedfromgroupsCA1andCA2withp<0.01inall

studysites;valuesingroupCA3wereintermediate(Fig.1

A-C).

BMD values (lumbar spine, proximal femur, and total

body)differedsignificantlybetweenB(p<0.01).GroupsB4

andB5showedthehighestmeanBMDvaluesinallsites,and

groupB3showedintermediatemeanvalue(Fig.1B).

BAP, OC, and S-CTx bone remodeling biomarkers had

significantly different concentrations at the beginning of

puberty.The median concentrationsin CA1and CA2were

significantly higher than those in CA3, CA4, and CA5

(p<0.001).MedianBAPconcentrationsinCA3werehigher

Breast development stage (B)

BMD (g/cm

2)

BMD (g/cm

2)

BMD (g/cm

2)

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2

Chronological age (CA)

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0

1.2 Lumbar spine Proximal femur Wholy body

CA 5 CA 1 CA 2 CA 3 CA 4

B5

B1 B2 B3 B4

Bone age (BA)

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2

BA5

BA1 BA2 BA3 BA4

C

OC (ng/mL)

0 20 80

60

40 100

BAP (UI/L)

0 50 100 150 200 250

Chronological age Breast development stage Bone age

CA1 B1 BA1

S-CTx (ng/mL)

0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0

F

B

A

E

D

CA2 B2 BA2 CA3 B3 BA3 CA4 B4 BA4 CA5 B5 BA5

CA1 B1 BA1 CA2 B2 BA2 CA3 B3 BA3 CA4 B4 BA4 CA5 B5 BA5

CA1 B1 BA1 CA2 B2 BA2 CA3 B3 BA3 CA4 B4 BA4 CA5 B5 BA5

Groups

Groups

Groups

Figure1 Graphicrepresentationofbonemassdensity(BMD)meansandstandarddeviationsoflumbarspine,proximalfemur,and wholebodyvaluesing/cm2accordingtoageranges(A);breastdevelopmentstage(B);andboneage(C).Bonealkalinephosphatase (BAP)(D);osteocalcin(OC)(E);andC-terminaltelopeptide(S-CTx)(F);mediansaccordingtoage-ranges,breastdevelopmentstage, andbone-agegroups.

betweenCA4andCA5medianconcentrationswasobserved. ChangesinOCconcentrations accordingtoagefolloweda similartrend tothose observed for BAP. The same trend wasobserved for S-CTx (p<0.001;Fig. 1).The highest

S-CTxmedianswereobservedinCA1andCA2,whichdiffered

fromCA5(Fig.1D-F).

Significant differences in weight and height were

observedinparticipantsinBA2andBA1.Thesedifferences

werealsoobservedintheBA3,BA4,andBA5groups,which

presentedmeansofweightandheighthigherthanthosein

BA1(Table1).

DifferencesinBMDvalueswereinitiallyobservedinthe

BA3group,whichdifferedfromtheBA1andBA2groupswith

p<0.01inallBMDvaluesandinallstudiedsites.TheBMD

meansincreasedfromthelowBAgroups towardsthehigh

BAgroups(Fig.1C).

Significant differences in bone remodeling biomarkers

wererecordedinallstudiedvariables(BAP,OC,andS-CTx)

whenpresentedaccordingtoBA;BA1andBA2medianswere

higherthanBA4andBA5medians(Fig.1D-F).

A significant positive correlation between BMD values,

for both CA and BA, wasobserved withmaturation level

(Table2);boneremodelingbiomarkers(BAP,OC,andS-CTx)

presentedasignificantnegativecorrelationwithCA,BA,and

breast development (Table 2). This finding demonstrated

that the more mature the participants were, the higher

theirBMDvalueswere.Correlationwassignificantbut

Table2 CoeficientofSpearman’scorrelationbetweenbonemineral density(BMD)measurements(g/cm2),bonebiomarker concentrations(bonealkalinephosphatase,osteocalcin,C-terminalteleopeptide),chronologicalage(CA),Breastdevelopment stage(B)andboneage(BA).

Variable Ageandbreastdevelopmentstage Bonebiomarker

CA B BA BAP OC S-CTx

BMD(g/cm2)Spine,L1-L4 0.754a 0.649a 0.760a -0.696a -0.367b -0.627a

Femur 0.605a 0.516a 0.652a -0.519a -0.334c -0.644a

Wholebody 0.766a 0.665a 0.789a -0.655a -0.425a -0.695a

BAP(IU/L) -0.822a -0.638a -0.831a - -

-OC(ng/ml) -0.552a -0.602a -0.482a - -

-S-CTx(ng/ml) -0.769a -0.653a -0.812a - -

-BAP,bonealkalinephosphatase;OC,osteocalcin;S-CTx,C-terminalteleopeptide;L1-L4,lumbarspine1and4. SignificanceofSpearman’scorrelation.

a p=0.001. b p=0.002. c p=0.005.

biomarkerconcentrations;themorematuretheparticipants were,thelowertheirbonebiomarkerconcentrationswere (Table2).

Table2 showsthedatafromthecoefficient of

correla-tionanalysisbetweenboneremodelingbiomarkersandBMD

values. These results demonstrate a negative and

signifi-cant correlation betweenBMD valuesandbone biomarker

concentrations.

Discussion

Thepresentstudyobservedsignificantnegativecorrelations between concentrations of bone remodeling biomarkers and CA, BA, breast development, and BMD values. Such evidencerevealsinverselyproportionaloutcomesin remod-elingbiomarkersandvariablesthatrepresenttimeandbone massmaturation.Thus,althoughtheBMDvaluesincreased withtheadvancementofmaturationevents,the concentra-tionsofthethreebiomarkersreducedwithageattheend ofadolescence,startingfrom15to16yearsofage(Fig.1).

Other authors have also observed the lowest bone

biomarkerconcentrations attheend ofpuberty,andhave

reportedbiomarker concentrations in 18-year-oldfemales

thataresimilartothoseinadults.13,21,22

Boot etal.8observed thatpeakbonemass,both inthe

lumbarregionandinthewholebody,occurredbetween18

and20yearsofageinagroupof360females.Silvaetal.23,24

and Moretto etal.25 showed that mean BMD values in all

evaluatedsitesincreasedwithage,skeletalmaturation,and

boneageinBrazilianadolescents.Inthesestudies,the

low-est BMDvalues wereobserved in 10-year-oldfemales and

thehighestonesinfemalesaged17yearsorover.Themost

criticalperiodsfor bonemassgrowthwerereportedtobe

between13and14yearsofage,infemalesatbreaststage

B3, and between 13 and 15 years in males at G4 stage.

These resultscorroborate the present findings,suggesting

theexistenceofawindowofopportunityforbonemassgain,

between13and14yearsofageandB3,in thecited

mat-urationperiods;thelinearregressionanalysesshowedBMD

gainsof0.0574,0.0592,and0.0654g/cm2inlumbarspine,

proximalfemur,andtotalbody,respectively,ineachyearof

growthinCA.

The literature is clear andin agreement that reaching

thehighest possiblepeakbonemassduringadolescenceis

animportantandpossiblythemainpreventivefactoragainst

occurrenceofsenileosteoporosis.26

Thefactthatbiomarkersproducesensitiveandaccurate

readingsofchangesin bonemetabolismshouldcontribute

totheirwideruseinclinicalpractice.Bloodbiomarker

mea-surementscanberepeatedmorefrequentlythanthemore

commonlyusedquantitativeradiologicalmethods,because

blood samples are comparatively easy to obtain. Despite

difficultiesintheanalysisandinterpretationof biomarker

resultsduetotheirbiologicalvariabilityinthecourseofan

individual’slife time,3 thereareadvantages in theuse of

thesemarkers.

It is therefore possible to anticipate that, when

indi-vidualspresent healthy development evolution in infancy

and puberty, free of conditions that interfere with bone

metabolism,boneformation markerswould befound

pro-portionally more active in the first two decades of life

thanreabsorption markers.Some other factorscan affect

boneremodelingbiomarkerconcentrations,suchasgenetic

factors, age, secondary sexual signs that represent

visi-bleevolution topuberty, lifestyle,nutrition,and physical

exercise.27

Tuchmanet al.22 observeda correlation between bone

biomarkersandpeakheightvelocity(PHV),demonstrating

aparallelismbetweenincreasedmarkerconcentrationsand

heightvelocity.Despitethis,Hareletal.11emphasizedthat

theBMD valuesstillcontinuedtoincreasewithincreasing

age,withamaximumincrease aroundmenarche, whichis

when girls are already decelerating height velocity. This

evolutionwas alsoobserved in thepresent data.

Sequen-tially,peakbonemasswillfinallybereachedatthemoment

when growth rate in height reduces. The final height, in

theseadolescents,wasattainedwhentheyreachedthe

B4-B5breastdevelopmentalstages.Aspreviouslystated,peak

height velocity(PHV) occurs at the same time asthe B3

breastdevelopmentalstageoralittleafterit.Thisbehavior

high-estconcentrationsinthisdevelopmentalstage,reinforcing

therelationship between theseevents andhormonal

fac-tors involved in these processes. From this perspective,

van Coeverden et al.13 and Yilmaz et al.6 evaluated the

magnitudeof therelationship betweenbone turnoverand

peakheightvelocity(PHV)analyzedbythelevelsofsome

bonemarkersandevaluatingsexsteroidlevels,insulin-like

growthfactor(IGF-1),andinsulin-likegrowthfactorbinding

protein3(IGF-BP-3).

Hence, these considerations allow for the

understand-ingofhigh levelsof correlation betweenbonebiomarkers

and bone mineral densities observed in our statistical

analysis.

Yilmaz et al.6 evaluated 91 Turkish pubescent females

and83males,11 to15 yearsold.Theirinclusioncriteria,

althoughveryprecise,werenotasrigidandrestrictiveasthe

presentstudy’s.Theauthors evaluatedBMD inthelumbar

spineandwholebody,aswellasestradiolandtestosterone

levels,andmeasuredboneformationmarkers(OCandBAP)

inbothgenders.TheirresultsofmaximumincreaseinBMD

occurringinpubertystage3corroboratethepresentresults.

TheseauthorsobservedthatmeanOCconcentrationswere

higherin females in Tanner stage 3 thanat B4 or B5and

steadilydecreasedtowardstheendofpuberty.This

behav-iorwasnotasexpressiveinBAP;however, itshowedthat

concentrations from mid-puberty were higher than those

at the end of puberty withsignificant differences in girls

(p<0.001).Furthermore,Yilmazetal.6demonstrated

signif-icantnegativecorrelationbetweenBMDandtheevaluated

bone markers,which corroboratesthe resultsobserved in

thepresentstudy.

Longitudinalstudiesperformedtoevaluateheight

veloc-itycurve andmaximum concentrations of bone formation

markers could contribute to confirm the parallelism

indi-rectlyobservedbetweenthesevariables.

Through analyses of biomarkers, the present study

demonstratesthechangesinbone remodelingoccurringin

thesecond decade oflife, revealing high marker

concen-trations in the early adolescence years and significantly

reduced concentrations in late adolescence. These

anal-yses correlate to the BMD values, which represent bone

massincorporation,andindicatean inverselyproportional

behavior showing the highest BMD values associated with

thelowestconcentrationsofformationandreabsorptionof

biomarkers.

Ideally,thepresentstudyshouldhavehadalongitudinal

designincludingahighernumberofparticipantsfromamore

comprehensivesamplinginsimilarcohorts(schools).Despite

thislimitation,thestrictinclusioncriteriafavoredan

accu-rateinterpretationofresultsforbonegainandmetabolism

duringadolescence.

Theresultsfromthepresentstudycomplementpublished

workonthesubjectandimprovetheunderstandingofbone

masschangesduringadolescence.

Funding

ThepresentestudywassupportedbyFAPESP(Fundac¸ãode Amparoà PesquisadoEstadodeSão Paulo)--- Process No: 2007/07731-0and2011/05991.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgments

ThisstudyreceivedgrantsfromFAPESP(2007/07731-0and 2011/05991)andPrope-UNESP(Pro-ReitoriadePesquisada UNESP).Theauthorsgreatlythankthepediatricians, tech-nicians of general sample collection room of the Clinical Laboratory-BotucatuGeneral Hospitalof BotucatuMedical School-UNESP,andtechniciansofthePediatricsLaboratory ResearchofthePediatricsDepartment.

References

1.Fernández-RealJM,RicartW.Osteocalcin:anewlinkbetween boneand energy metabolism.Someevolutionary clues.Curr OpinClinNutrMetabCare.2011;14:360---6.

2.Kim YS, Paik IY, Rhie YJ, Suh SH. Integrative physiology: definednovelmetabolicrolesofosteocalcin.JKoreanMedSci. 2010;25:985---91.

3.BanfiG,LombardiG,ColombiniA,LippiG.Bone metabolism-markersinsportsmedicine.SportsMed.2010;40:697---714. 4.KhanK,MckayH,KannusP,BaileyD,WarkJ,BennellK.Physical

activityandbonehealth.BrJSportsMed.2002;36:76---7C. 5.daSilvaCC,KurokawaCS,NgaHS,MorettoMR,DalmasJC,

Gold-bergTB.Bonemetabolismbiomarkers,bodyweight,andbone ageinhealthyBrazilianmaleadolescents.JPediatrEndocrMet. 2012;25:479---84.

6.YilmazD,ErsoyB,BilginE,GümüserG,OnurE,PinarED.Bone mineraldensityingirlsandboysatdifferentpubertalstages: relationwithgonadalsteroids, bone formationmarkers,and growthparameters.JBoneMinerMetab.2005;23:476---82. 7.Heaney RP, Abrams S, Dawson-Hughes B, Looker A,

Mar-cus R, Matkovic V, et al. Peak bone mass. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:985---1009.

8.BootAM,deRidderMA,vanderSluisIM,vanSlobbeI,Krenning EP,Keizer-SchramaSM.Peakbonemineraldensity,leanbody massandfractures.Bone.2010;46:336---41.

9.DennisonE,MohamedMA,CooperC. Epidemiologyofosteoporo-sis.RheumDisClinNorthAm.2006;32:617---29.

10.Saraiva GL, Lazaretti-Castro M. Marcadores bioquímicos da remodelac¸ão óssea na prática clínica. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab.2002;46:72---8.

11.HarelZ,GoldM,Cromer B,BrunerA,StagerM,BachrachL, etal.Bonemineraldensityinpostmenarchaladolescentgirls intheUnitedStates:associatedbiopsychosocialvariablesand boneturnovermarkers.JAdolescHealth.2007;40:44---53. 12.SilvaCC,GoldbergTB,NgaHS,KurokawaCS,CapelaRC,Teixeira

AS,etal.Impactofskeletalmaturation onbonemetabolism biomarkersandbonemineraldensityinhealthyBrazilianmale adolescents.JPediatr(RioJ).2011;87:450---6.

13.van Coeverden SC, Netelenbos JC, de Ridder CM, Roos JC, Popp-SnijdersC,Delemarre-vandeWaalHA.Bonemetabolism markersandbonemassinhealthpubertalboysandgirls.Clin Endocrinol.2002;57:107---16.

14.Hamill PV, DrizdTA, Johnson CL,Reed RB, RocheAF,Moore WM.Physicalgrowth:NationalCenterforHealthStatistics per-centiles.AmJClinNutr.1979;32:607---29.

15.CentersforDiseaseControlandPrevention,(CDC).Prevalence of overweight among adolescents - United States, 1988-91. MMWR,MorbMortWkly,Rep.1994;43:818---21.

SaúdedoAdolescente.Adolescênciaesaúde.SãoPaulo:Paris Editorial;1988.p.43---57.

17.GreulichWW,PyleSL.Radiographicatlasofskeleton develop-mentofthehandandwrist.PaloAlto:StanfordUniversityPress; 1959.

18.CintraIP,vonDerHeydeME,SchimitzBA,FranceschiniSC, Tad-deiJA,SigulemDM.Métodosdeinquéritosdietéticos.CadNutr. 1997;13:11---23.

19.PhiliphiST,SzarfarcSC,Lattrza AR.VirtualNutri. Versão1.0 paraWindows.SãoPaulo:UniversidadedeSãoPaulo,Faculdade deSaúdePública,DepartamentodeNutric¸ão.

20.GordonCM,BachrachLK, CarpenterTO,Crabtree N,El-Hajj FuleihanG, Kutilek S,et al.Dualenergy X-ray absorptiome-tryinterpretationand reportinginchildrenandadolescents: the 2007 ISCD Pediatric Official Positions. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11:43---58.

21.WalshJS,HenryYM,FatayerjiD,EastellR.Lumbarspinepeak bonemassandboneturnoverinmenandwomen:alongitudinal study.OsteoporosInt.2009;20:355---62.

22.Tuchman S, Thayu M, Shults J, Zemel BS, Burnham JM, LeonardMB.Interpretationofbiomarkersofbonemetabolism

inchildren:impactofgrowthvelocityandbodysizeinhealthy childrenandchronicdisease.JPediatr.2008;153:484---90. 23.Silva CC,GoldbergTB, Teixeira AS,Dalmas JC. A predictive

analysis from bone mineral density among eutrophic Brazil-ian male adolescents. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab. 2006;50: 105---13.

24.SilvaCC,GoldbergTB,TeixeiraAS,DalmasJC.Bone mineraliza-tioninBrazilianadolescents:theyearsofmaximumbonemass incorporation.ArchLatinoamNutr.2007;57:118---24.

25.MorettodeOliveriaMR,CristianedaSilvaC,KurokawaCS, Teix-eira Fortes CM, Campos Capela R, Santos Teixeira A, et al. Bonemineraldensityinhealthyfemaleadolescentsaccording toage, boneageand pubertalbreaststage.OpenOrthopJ. 2011;5:324---30.

26.Janz K. Physical activity and bone development during childhood and adolescence. Implications for prevention of osteoporosis.MinervaPediatr.2002;54:93---104.