An institution-based view of ownership in cross-border acquisitions: mimetism by Latin American firms

Texto

(2) CLÁUDIA SOFIA FRIAS PINTO. An institution-based view of ownership in cross-border acquisitions: Mimetism by Latin American firms. Dissertação apresentada à Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getulio Vargas, como requisito para obtenção do título de Doutor em Administração de Empresas. Campo de conhecimento: Estratégia. Orientadora: Prof. Dr. Maria Tereza Leme Fleury. SÃO PAULO 2017.

(3) Pinto, Cláudia Sofia Frias. An institution-based view of ownership in cross-border acquisitions: Mimetism by Latin American firms / Cláudia Sofia Frias Pinto - 2017. 118 f.. Orientador: Maria Tereza Leme Fleury Tese (doutorado) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo.. 1. Empresas multinacionais - América Latina. 2. Fusão e incorporação. 3. Empresas - Fusão e incorporação. I. Fleury, Maria Tereza Leme. II. Tese (doutorado) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. III. Título.. CDU 334.726(8).

(4) CLÁUDIA SOFIA FRIAS PINTO. An institution-based view of ownership in cross-border acquisitions: Mimetism by Latin American firms. Dissertação apresentada à Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getulio Vargas, como requisito para obtenção do título de Doutor em Administração de Empresas. Campo de conhecimento: Estratégia. Data de aprovação: 31/05/2017. Banca examinadora:. _________________________________ Prof. Dr. Maria Tereza Leme Fleury (Orientadora) FGV- EAESP. _________________________________ Prof. Dr. Jorge Manoel Teixeira Carneiro FGV- EAESP. _________________________________ Prof. Dr. Felipe Mendes Borini ESPM e USP-FEA. _________________________________ Prof. Dr. Ronaldo Couto Parente Florida International University (US) e FGV- EBAPE.

(5) To my mentor, family and friends..

(6) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is an endeavor in which we benefit from the different contributions of many professors, colleagues and friends. It is not simple to thank all those more directly and indirectly involved, since this is a path that has started many years ago in other studies at the undergraduate and graduate level. First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to my advisor, Professor Maria Tereza Fleury, for her support throughout the years of my Ph.D., for her willingness to share her expertise, and her availability and patience as I seek to learn more and improve my ability to become a high quality researcher. I also would like to thank to Professor Afonso Fleury for all the support, namely as we have developed other projects, for the guidance and learning accumulated. Many other professors at EAESP/FGV have also contributed to my learning experience and I especially thank Professor Tales Andreassi, Professor Sergio Bulgacov, Professor Rafael Alcadipani, Professor Abraham Laredo and Professor Moacir Oliveira Jr of USP. Certainly my acknowledgement extends to the members of the qualifying for their advice on how to improve the dissertation, Professor Felipe Borini and Professor Rodrigo Bandeira-deMelo. I certainly also thank my friends and colleagues in EAESP/FGV, namely Cyntia Calixto, Marina Gama, Marcus Salusse and Andréa Carvalho, for the rich discussions and the joyful coffee-breaks and talks at lunch. I thank Fernando Serra for all the support and friendship. I further thank Manuel for sharing the life and knowledge and his willingness to discuss my ideas as well as his incentive to pursue research projects. I love you! Finally, I would like to thank my parents, Manuel and Maria Otilia, and my brother Celso, for their invaluable love, support and patience. You are my world! To all, including those that I have missed here, my sincere thanks! Thank you for all your love, support and patience..

(7) RESUMO Este estudo baseia-se na Visão baseada em instituições para explicar as decisões de posse das multinacionais da América Latina em aquisições internacionais. Analisamos especificamente (1) o efeito da distância institucional na posse adquirida, (2) os comportamentos miméticos relacionados com a posse das multinacionais da América Latina quando realizam aquisições internacionais e (3) se adquirir um negócio relacionado tem impacto na força da distância institucional e do isomorfismo mimético. Investigamos quatro níveis de fontes de imitação, incluindo a experiência anterior da própria empresa, empresas domésticas e estrangeiras, e competidores da mesma indústria. Os resultados dos testes empíricos, usando uma análise de regressão logística em uma amostra de 1.334 aquisições internacionais efetuadas por multinacionais da América Latina e uma amostra transversal de 567 aquisições internacionais da indústria da manufatura, durante um período de mais de 20 anos (1995-2015), apoiam o quadro baseado em instituições, com diferentes influências nas escolhas da posse nas aquisições internacionais. Os resultados mostram evidências de que as multinacionais preferem adquirir posse total quando investem em países institucionalmente mais distantes. Mais, confirmamos que os comportamentos miméticos das multinacionais relacionados à posse em aquisições internacionais ocorrem nos quatro níveis. Finalmente, a influência da distância institucional, imitação das empresas estrangeiras e dos competidores da mesma indústria são fortalecidos pela aquisição de um negócio relacionado, enquanto que o efeito de imitar as experiências anteriores da própria empresa e das empresas domésticas é enfraquecido pela aquisição de um negócio relacionado. Contribuímos para a Visão baseada em instituições da Estratégia internacional identificando os comportamentos miméticos específicos à posse adquirida pelas empresas quando se internacionalizam. Além disso, também contribuímos para a crescente literatura sobre multinacionais da América Latina, ou multilatinas, fornecendo um melhor entendimento acerca das suas estratégias em aquisições intenacionais. Usamos uma abordagem multinível para trazer uma nova compreensão de como as multinacionais da América Latina imitam as decisões de posse em aquisições internacionais. Para o estudo da posse, e especificamente da posse em aquisições internacionais, contribuímos com uma interpretação comportamental e consideramos o isomorfismo entre multinacionais, indo além dos determinantes convencionais como custos de transação, assimetria informacional ou incerteza..

(8) Palavras-chave: Aquisições internacionais; posse; isomorfismo mimético; visão baseada em instituições; multinacionais da América Latina.

(9) ABSTRACT This study draws upon the institution-based view to explain the ownership decisions by Latin American multinationals (LAMNCs) in cross-border acquisitions (CBAs). We specifically examine (1) the effect of institutional distance on the ownership acquired, (2) the mimicking behaviors regarding ownership of MNCs from Latin American countries when undertaking CBAs and (3) if acquiring a related business impact the strength of institutional distance and mimetic isomorphism. We endeavor into investigating four levels of imitation sources, including firms own prior experience, home and foreign firms, and industry competitors. The results of the empirical tests, using a logistic regression analysis on a sample of 1,334 CBAs by LAMNCs and a cross-sectional sample of 567 CBAs from the manufacturing industry, over a 20-year period (1995-2015), support an institutional-based framework with different influences in the ownership choices in CBAs. Our findings provide evidence that MNCs prefer to acquire full ownership when investing in institutionally distant countries. Furthermore, we confirmed that the mimicking behavior of MNCs pertaining to ownership in CBAs occurs at four levels. Finally, the influence of institutional distance, mimicking of foreign fims and industry competitors are strengthened by the acquisition of a related business, albeit the effect of mimicking own firm prior experiences and home firms is weakened by the acquisition of a related business. We contribute to the institution-based view of. international. strategy. identifying. the. specific. mimetic. behaviors. of. firms’. internationalization ownership in foreign operations. Moreover, we also contribute to the burgeoning literature on LAMNCs, or multilatinas, by providing a better understanding of their strategies regarding CBAs. We use a multi level approach to bring a new understanding of how LAMNCs mimic ownership decisions in CBAs. To the study on ownership, and specifically ownership in CBAs, we contribute for a behavioral interpretation and consider isomorphism between MNCs, going beyond conventional determinants such as transaction costs, informational asymmetry or uncertainty.. Keywords: Cross-border acquisitions; ownership; mimetic isomorphism; institution-based view; Latin American multinationals.

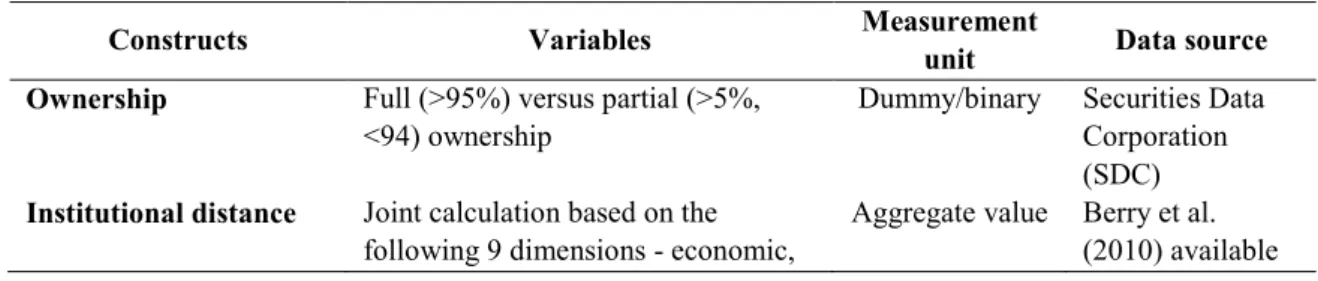

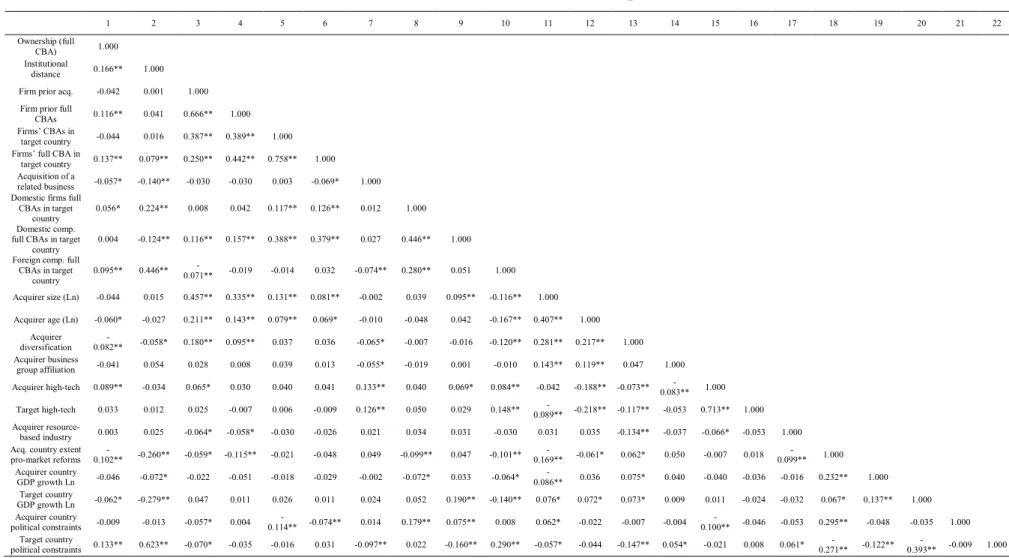

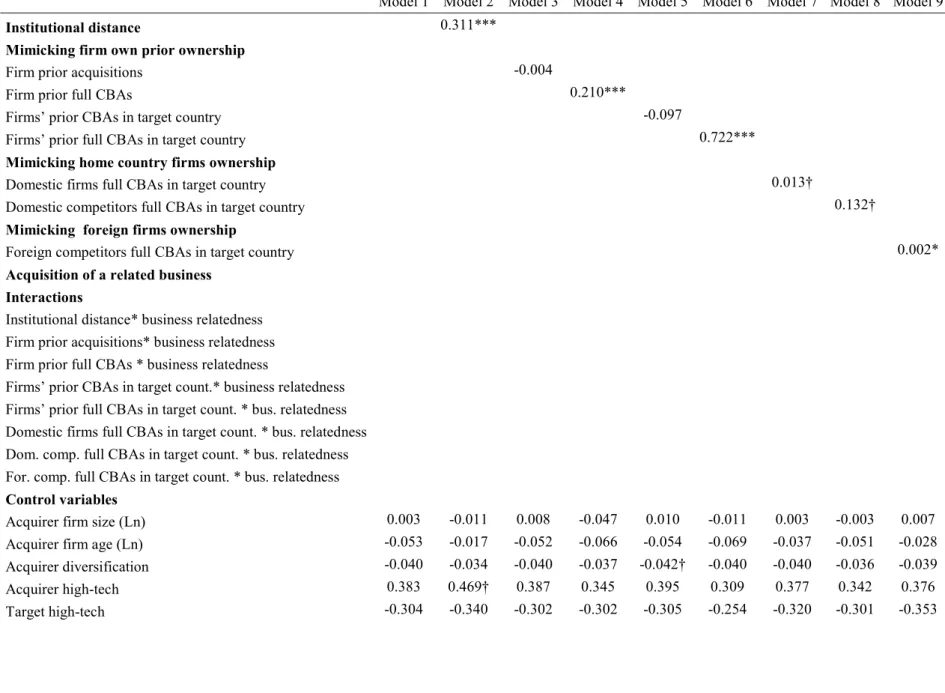

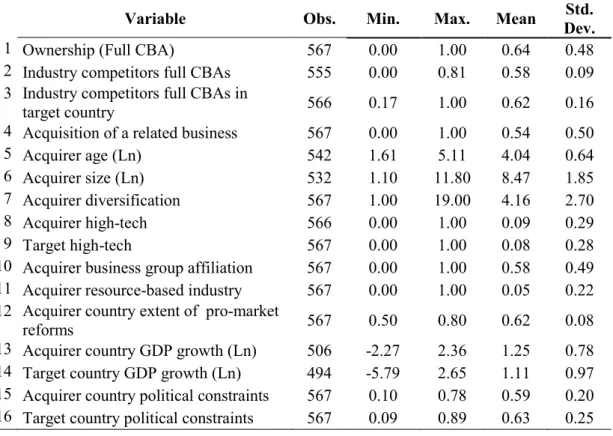

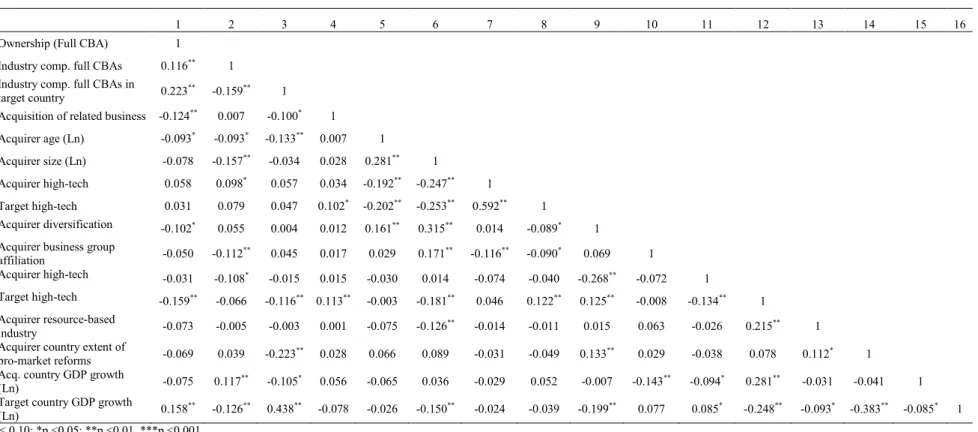

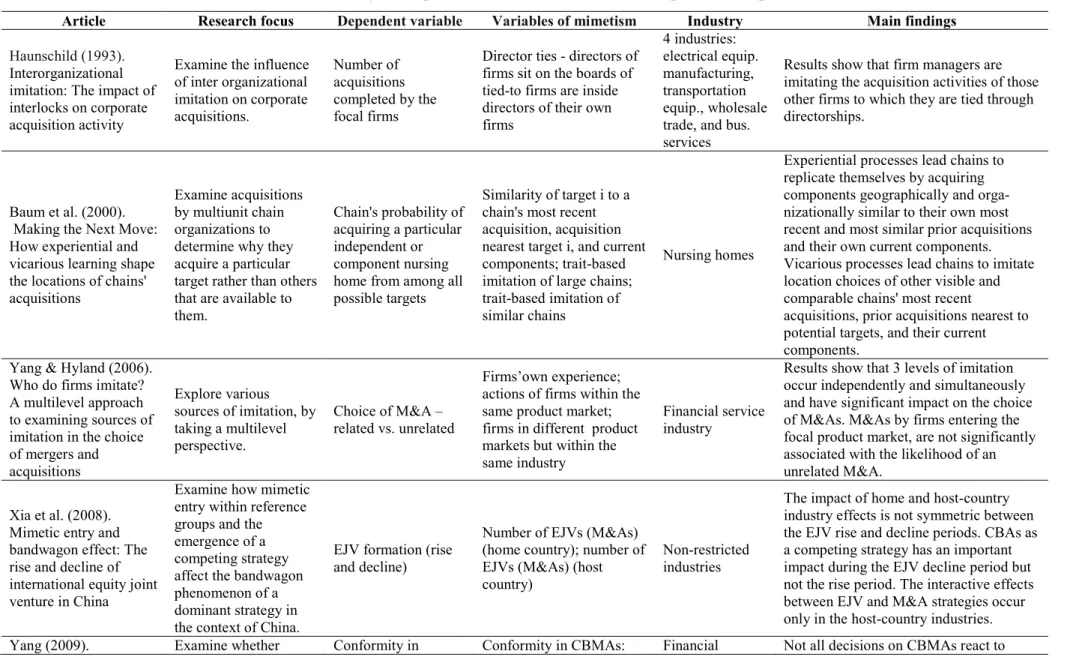

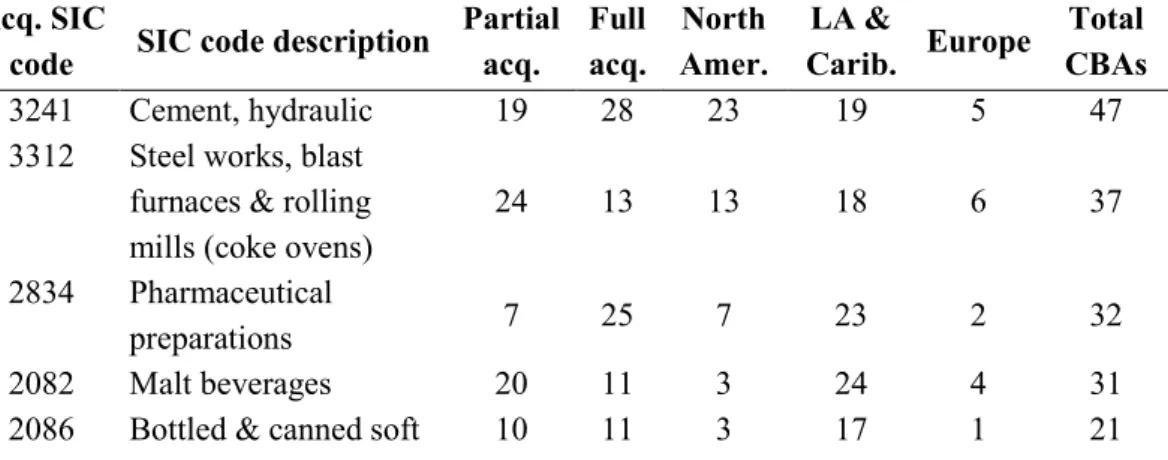

(10) LIST OF TABLES Page Table 2.1. Summary of empirical research on full vs. partial ownership in CBAs …………………………………….. Table 2.2. Summary of empirical research on mimetic isomorphism in acquisitions ................................................................... 11. 19. Table 4.1. Target countries and ownership stake ………………....... 50. Table 4.2. Regions of the target countries and ownership stakes ..... 50. Table 4.3. Manufacturing SIC codes ……………………………..... 51. Table 4.4. Ownership stake and regional distribution of the main acquirer industries ………………………………………. 52. Table 4.5. Constructs, variables and data sources …………………. 57. Table 5.1. Descriptive statistics (full sample) ……………………... 61. Table 5.2. Correlations matrix (full sample) ……………………..... 63. Table 5.3. Logistic models for ownership acquired (full sample) .... 66. Table 5.4. Descriptive statistics (manufacturing industry sample) .... 74. Table 5.5. Correlations matrix (manufacturing industry sample) .... 75. Table 5.6. Logistic models for ownership acquired in the manufacturing industry …………………………………. 77.

(11) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS …………………………………………………... RESUMO ….…………………………………………………………............... ABSTRACT ...………………………………………………………………… LIST OF TABLES ………..…………………………………………………… 1. INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………….. 1. 1.1. Structure of the dissertation ………………………………………….... 4. 2. LITERATURE REVIEW …………………………………………………... 6. 2.1. Cross-border acquisitions .…………………………………………….. 6. 2.2. Ownership decisions in CBAs .………………………………............... 9. 2.3. The Institution-Based View ………………………………………….... 13. 2.3.1. Mimetic isomorphism ………………………………………….. 15. 2.3.2. Institutional distance ………………………………………….... 22. 2.4. Business relatedness of the acquisition ………………………………... 24. 3. HYPOTHESES ……………………………………………………………... 27. 3.1. Institutional distance and ownership ………...………………………... 27. 3.2. The mimetic behavior of MNCs ………………………………………. 29. 3.2.1. Firm own prior ownership ……………………………………... 31. 3.2.2. Home country firms’ ownership ……………………………….. 32. 3.2.3. Foreign firms’ ownership …………………………………….... 33. 3.2.4. Industry competitors and ownership ………….……................... 35. 3.4 Business relatedness and ownership in CBAs ........................................ 37. 3.4.1. Acquisition of a related business and institutional distance ….... 39. 3.4.2. Acquisition of a related business and mimicking firm own prior ownership ………………………………………………... 3.4.3. Acquisition of a related business and mimicking home country firms’ ownership……………………………………………...... 3.4.4. Acquisition of a related business and mimicking foreign firms’ ownership .................................................................................... 3.4.5. Acquisition of a related business and mimicking industry competitors’ ownership ............................................................... 4. METHOD ………………………………………………………………….... 40. 41. 42. 43 46.

(12) 4.1. The context of Latin America…………………………………………... 46. 4.2 Data …………………………………………………………………….. 48. 4.3. Sample ……………………………………………………………….... 48. 4.4. Variables ………………………………………………………………. 53. 4.5. Procedures of analysis …………………………………………………. 59. 5. RESULTS …………………………………………………………………... 61. 5.1 Summary of the main findings ………………………………………... 64. 5.2 Empirical results ………………………………………………………. 65. 5.2.1 Effects of institutional distance ……………………………….... 70. 5.2.2 Effects of firm own prior ownership ………………………….... 70. 5.2.3 Effects of home country firms’ ownership ……........................... 70. 5.2.4 Effects of foreign firms’ ownership …………………………….. 71. 5.2.5 Effects of the interactions ………………..................................... 71. 5.2.6. Effects of mimicking manufacturing industry competitors’ ownership …………………………………………………….. 73. 6. DISCUSSION ………………………………………………………………. 78. 6.1. Main findings and implications ………………………………………. 79. 6.2. Contribution to theory and practice …………………………………... 82. 6.3. Limitations and future research ………………………………………. 85. 7. CONCLUSION …………………………………………………………….. 87. REFERENCES ……………………………………………………………….... 91. APPENDIX ……………………………………………………………….......... 104.

(13) INTRODUCTION This study focuses on what institutional dimensions determine a multinational’s choice of ownership in cross-border acquisitions (CBAs). Past discussion on this question focused on economic and strategic motivations (e.g. Chen & Hennart, 2004; Chen, 2008; Chari & Chang, 2009). A more recent stream of literature in international business started to focus on the social processes that underlie the choices of CBAs (e.g. Haunschild, 1993; Li et al., 2012; Yang & Hyland, 2012; Ang et al., 2016), arguing that multinationals (MNCs) also base their CBAs behavior on the actions of other firms. The question that arises now is: toward whom do firms orient their behaviors? (Yang & Hyland, 2006). Social influences such as inter-firm mimicking (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) are key determinants influencing international strategies (Yang & Hyland, 2012), such as the ownership in CBAs. The social perspective argues that MNCs facing uncertainty are likely to consider other firms as reference models and mimic their strategies (Gimeno et al., 2005), such as deciding where to acquire (location) or what ownership to acquire. However, despite of the several studies stating that mimetic isomorphism appears in the international setting (e.g. Haunschild, 1993; Yang & Hyland, 2012; Li et al., 2012), the mimetic isomorphism argument still needs more clarification (Greenwood et al., 2008; Yang & Hyland, 2012). Likewise, critical questions like whether strategic decisions of CBAs, such as ownership, are influenced by mimicking remain unanswered. CBAs strategies have received considerable research inquiry from international business researchers. International business researchers seeking to comprehend the role and influence of the many institutions that characterize countries, leading to the emergence of what Peng et al. (2009) has coined as an Institution-Based View (IBV) of International Business (IB) strategy. The IBV in IB delves into how the actions, strategies, successes and failures of MNCs are, at least in part, determined by the institutions (Peng, 2014), both in the MNCs’ home country, the host country where MNCs invest, or the manner in which home and host countries differ. Institutional frameworks impact the actions and behaviors of MNCs by constraining which actions and behaviors are acceptable and legitimate in those countries where MNCs operate and compete (Peng & Heath, 1996), thus inherently influencing MNCs’ behaviors and strategic choices (Peng & Heath, 1996). MNCs strategic choices comprise such core IB decisions such as ownership decisions in CBAs. Strategic choices, such as CBAs ownership decisions, are not merely driven by industry- or firm-level specific resources, capabilities or advantages, but rather are also a. 1.

(14) reflection of the constraints of a particular institutional framework facing MNCs (Peng et al., 2008). By taking an IBV we treat institutions as independent variables, and thus seek to focus on the dynamic interactions between institutions and MNCs, such that the strategic choices are the outcome of such interactions (Peng et al., 2009). MNCs international strategic choices can thus be viewed as the outcome of such interaction, and perhaps more specifically the manner in which MNCs decide to operate abroad is in itself a reflection of how it assesses the risk and costs, or transaction costs, of the foreign entry decisions. To some extent thus, choices regarding ownership adopted in CBAs are formulated considering the risks and hazards perceived from operating in different, and perhaps unfamiliar, institutional milieus. As MNCs endeavor in international operations, they have to deal not only with home institutional environment but also with the host country institutional environment, and how home and host differ. When choosing CBAs strategies MNCs have to deal with the institutional uncertainty and may respond adopting mimetic behaviors. That is, in dealing with institutional environment uncertainty, MNCs may model themselves following other MNCs (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) as possibly those that are perceived as more successful (Haveman, 1993). MNCs are likely to imitate other MNCs in terms of international strategy, governance structure, resources and constraints (Haveman, 1993; Brouthers et al., 2005). Even though research has noted the effects of mimicking behavior at different levels - country-level, local and global industry-level, and firm-level (Chan et al., 2006) - there is a consistent limitation in these works (Haunschild & Miner, 1997; Garcia-Pont & Nohria, 2002), pertaining the lack of consideration of the influence of the home (Delios et al., 2008) and the host environment (Xia et al., 2008; Ang et al., 2015). Ownership is an important CBA strategy for MNCs from emerging countries that face great uncertainty and suffer not only from liability of foreignness in the host country (Zaheer, 1995), but also institutional weaknesses in the home country (Khanna & Palepu, 2000; Luo & Tung, 2007). These MNCs face great uncertainty when making strategic CBAs decisions, especially when seek for high ownership stakes (Cui & Jiang, 2012). Institutional researchers argued that in order to cope with the uncertainty generated from home-host institutional environments, MNCs are tempted to mimic their own prior strategies and/or the strategies that were adopted by their counterparts (Haunschild & Miner, 1997; Henisz & Delios, 2001; Li et al., 2012). By mimicking the ownership choices, MNCs may on the one hand reduce the uncertainty of entering in an unknown foreign institutional environment, and on another hand compensate the liability of foreignness legitimating their decisions.. 2.

(15) Several scholars and studies have already noted that some CBAs decisions, such as ownership, may be a means of conformity to the home and foreign institutional environment (Yang, 2009; Yang & Hyland, 2012; Xie & Li, 2016). Indeed, at the best of our knowledge only three studies have found empirical evidence of mimicking in ownership decisions among MNCs, and where restricted to one emerging country, China (Yang, 2009; Yang & Li, 2012; Xie & Li, 2016). Although these studies have advanced our understanding of internationalization by establishing a link between internationalization through acquisitions and mimetic isomorphism, our understanding of the phenomenon still remains incomplete. In fact, researchers paid a limited attention to the use of mimetic isomorphism as an alternative explanation for ownership choices in CBAs, made by MNCs from other emerging countries. This study extends previous literature of mimetic behavior in the international setting to a specific strategy, ownership in CBAs, initiated by Latin American multinationals. Taking into account the aforementioned contingencies, we design the current study to take a fresh look at one of the important inquiries in IB/ strategy research: how do dimensions of institutional environment, such as mimetic isomorphism and institutional distance, influence the MNCs’ ownership choices in CBAs? This umbrella research question comprises related questions that warrant empirical research, namely: How do different levels of MNCs mimetic behavior influence their ownership choices in CBAs? How does institutional distance between home-host countries influence the MNCs’ ownership choices in CBAs? How does a firm strategy, such as the acquisition of a related business interact with these institutional dimensions and influence the ownership choices in CBAs? The outcome of this research is to provide a better understanding of the institutional dimensions influencing the ownership choices in CBAs. Recent IB researchers suggested that MNCs from emerging countries suffer from both home (Luo & Tung, 2007) and host country institutional constraints (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999) that may change their behaviors and foreign strategic choices. We include two critical institutional dimensions, MNCs’ mimetic behavior and institutional distance between home-host countries, which highlight the MNCs’ unique strategic concerns. Moreover, we analyze the moderating effect of a firm strategic decision, acquisition of a related business. The moderator of MNCs’ strategy identified in this study provides important evidence that MNCs’ ownership considerations in CBAs are not only influenced by institutional dimensions but also by a firm strategic decision. We test these assertions using a sample of 1,334 CBAs made by Latin American MNCs in 29 target countries, from 1995 to 2015. As expected, LAMNCs imitate their own prior ownership decisions, their home and foreign firms, and their industry competitors, thus. 3.

(16) leading them to acquire full ownership stakes. The results show that facing high institutional distances LAMNCs opt for full CBAs. In addition, acquiring a related business seems more important than mimicking own prior ownership decisions or those of their home-country firms, thus leading them to acquire partial ownership. These findings suggest that LAMNCs may choose the ownership in CBAs according to institutional factors, such as mimetic isomorphism and institutional distance, and that a firm strategic decision, such as the acquisition of related business may influence these choices. In other words, ownership choices in CBAs are endogenous. Since prior studies have not examined these institutional dimensions and firm strategy decision, we know little about the underlying mechanisms by which these endogenous variables impact LAMNCs ownership in CBAs. This study makes several contributions to the strategy and the IB literature. First, we debate how MNCs strategies are not solely determined by the institutions, and an IBV permits us understand the more complex interactions among institutions and MNCs international strategies. An important contribution is to shed light on the mimetic isomorphism literature, by showing the strength of imitation for MNCs when endeavor in CBAs. A second contribution is sought to the literature on emerging countries MNCs and their international strategies by scrutinizing the strategies pursued by LAMNCs in CBAs - and their ownership decisions -, specifically facing different institutional environments. Third, we present a perspective of how the institutional facets of home-host environments influence the ownership choices in CBAs. This complements the extant body of literature that has more recently been developed within emerging countries research. We not only theoretically explain but also empirically analyze how institutional differences between home-host impacts the ownership acquired in CBAs. We specifically contend that the institutional environment is multifaceted and there is a set of institutional dimensions that influence MNCs behavior and the ownership stake acquired in CBAs.. 1.1 Structure of the dissertation This dissertation is organized in seven chapters as follows. First, we review the core literature on Institution-based view, institutional factors and ownership decisions in crossborder acquisitions. In the third chapter, we develop an institution-based view conceptual model and present the arguments supporting 10 theory-driven hypotheses suggesting a manner to examine the impact of institutional dimensions, specifically adressing mimetic strategic responses on the ownership acquired in cross-border acquisitions. The fourth chapter comprises the method, including data collection procedures, sample and variables. In the fifth. 4.

(17) chapter we present the results using logistic regression. The sixth chapter entails a broader discussion of the results, a synthesis of the main findings and contributions, implications for theory and practice, limitations of the study and avenues for future research. Finally, the seventh chapter presents the conclusions of this study.. 5.

(18) 2. LITERATURE REVIEW In this chapter we briefly review the relevant extant literature. We review the literature on the Institution-Based View (IBV), and further delve into the construct of mimetism, or mimetic isomorphism, as firms’ strategic response to institutional uncertainty, and apply this perspective to understanding MNCs’ strategic choices regarding the ownership in crossborder acquisitions (CBAs). The IBV is thus the main conceptual foundation used in this dissertation.. 2.1. Cross-border acquisitions Cross-border acquisitions (CBAs) are widely used by firms across the world (Cartwright & Schoenberg, 2006) and the primary ownership-based mode of both domestic and foreign expansion (UNCTAD, 2015). Recent years have witnessed to consistently high volumes, and values involved, in CBAs worldwide – in 2014, reached the gross value of US$900 billion, considerably above the US$775 billion, on average, during the period 20102014 (UNCTAD, 2015). In 2014, there were 223 large deals each worth more than US$1 billion, with an average value per deal of nearly US$ 3.4 billion (UNCTAD, 2015). CBAs have become major strategic tools for MNCs’ growth (Hitt et al., 2001), attracting the attention of scholars, perhaps more especially in Finance, Strategy and International Business. CBAs are a form of governance of transactions in which the acquirer MNC expands its internal boundaries by internalizing activities that were previously executed by an acquired firm. A CBA occurs when one firm (the acquirer MNC) acquires part or the totality of the ownership of another firm (the target firm) in a foreign country. The ownership stake in a CBA varies from 1% to 100%, although it is usually assumed that the acquisition of small equity stakes on a target are likely to be speculative, short term, portfolio investments. Given their importance for firms, scholars have been trying to explain CBAs using different theories and conceptual perspectives, as well as calculating the impact of CBAs on firms’ performance. For instance, a stream of research has used the Transaction Costs Theory often seeking to explain CBAs vis a vis alternative foreign entry modes (Kale, Singh & Raman, 2009), or as vehicles to minimize costs of exploiting current firm specific advantages or of exploring new advantages (Madhok, 1997). Transaction costs theory tends to understand each foreign entry as an independent event (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977) relating more to risk and control arguments (Gatignon & Anderson, 1988). For instance, Hennart and Park (1993) argued that greenfield ventures are preferred over CBAs when subjected to lower transaction. 6.

(19) costs in the host country, because greenfield operations minimize potential integration hazards and conflicts with the workforce of the acquired firm. According to Hennart and Park (1993) and Harzing (2002) CBAs provide more opportunities for greater organizational efficiencies than the alternative foreign entry modes. Notwithstanding these contributions, and of the theory to explain CBAs, Ferreira et al. (2014) noted that there has been a decrease in the use of transaction costs theory in CBA research. Another important stream of research has been supported on the Resource-, Capabilities- and Knowledge-Based Views of the firm (Ferreira et al., 2014). In this stream of studies, CBAs are often portrayed as vehicles used by the acquirer firms to learn and augment their resources, capabilities and knowledge base, especially those that are not available in the factor market (Ferreira, 2007). This stream of research sees CBAs as beneficial for firms (Barney, 1988), and as opportunities for firms to reconfigure their businesses (Ferreira, 2007) and demonstrate the potential gains accruing from CBAs beyond only financial performance effects. Dunning’s (1988) eclectic paradigm combines insights from resource-based view, transaction costs and institutional theories (Brouthers & Hennart, 2007). The paradigm states that firms choose the most appropriate entry mode into foreign expansion, by considering three factors (OLI framework): ownership (O), location (L), and internalization (I) (Dunning, 1988). Ownership advantages are firm-specific competitive advantages (resource-based view) and must be unique – e.g., international experience. Location advantages are country-specific advantages (institutional theory) and internalization advantages (transaction costs theory) are the benefits a firm obtains by choosing high commitment entry mode (e.g., acquisition, wholly owned), rather than internationalizing through partnership agreements (Dunning, 1988). A more recent stream of research in the management/business literature dealing with CBAs is the institutional theory. Until very recently, IBV was absent from CBAs research, probably because the majority of FDI originates in developed countries that have stable and established institutions (Peng et al., 2009). However, there has been an increasingly number of studies that use an IBV to explain how home and host countries institutional environment, and how they differ, influences MNCs internationalization, particularly MNCs investing in and out emerging countries (Peng, 2012). Institutions are especially salient as determinants of CBAs undertaken between developed countries MNCs and MNCs from emerging countries, and between MNCs in different emerging countries (Hoskisson et al, 2013).. 7.

(20) That is, albeit reasonably recent, an Institution-Based View as already made substantial inroads into the understanding of CBAs as the entry mode into foreign countries. Perhaps more notably, scholars have used an IBV in exploring CBAs as an entry mode thus comparing to alternative modes of foreign entry. For instance, noting that CBAs may be the preferred entry mode in emerging countries, from the perspective of MNCs based in developed countries (Meyer et al., 2009). For example, Graham, Martey and Yawson (2008) examined UK acquirers in emerging economies. They found that firm size, market-to-book ratio, stock price performance and liquidity are positively associated with the likelihood of doing CBAs in emerging countries. Other studies explored CBAs as an entry mode chosen by MNCs from emerging markets to develop countries (Rabbiosi et al., 2012; Buckley et al., 2014) and to other emerging countries (Contractor et al., 2014). Rabbiosi et al. (2012), has shown that firms from emerging countries undertake acquisitions in developed countries in an incremental fashion, i.e. international experience and home-country characteristics are essential sources of learning. Buckley et al. (2014) developed a framework about the resource- and context-specificity of prior experience in acquisitions and demonstrated that not all types of resources and investment experience are equally beneficial to the performance of target firms. Finally, Contractor et al. (2014) used a sample that comprised acquisitions in India and China, and explained the choice of ownership based on the distances between the countries of the acquirer and target firm. MNCs engage in CBAs for a variety of motivations and strategies. Scherer and Ross (1990: 159) synthetized six main motivations for acquisitions: (a) monopolize an industry and reduce competition, (b) obtain production efficiencies reducing production costs and promoting scale economies and specialization, (c) achieve synergies through an efficient coordination of complementary resources, (d) overcome market failures in the capital market and reduce the cost of capital, (e) restructure poorly managed firms that are traversing difficulties, and (f) benefit from speculation with the effects of the merger and acquisition in the stock markets. Ferreira et al. (2014) presented other explanations for CBAs that included exploiting synergies between the firms’ value chain (Bradley et al., 1988; Seth, 1990), that may lead to greater operational efficiency and increased market power (Singh & Montgomery, 1987; Seth, 1990) and reduce competition (Bradley et al., 1988). These synergies may also seek to decrease dependency of the consumers (Chatterjee, 1986), the ability to increase prices for consumers (Hitt et al., 2001), benefit from cost reductions and economies of scale (Homburg & Bucerius, 2006) or an effective coordination of resources (Chatterjee & Lubatkin, 1990). MNCs engage in CBAs also to develop a first mover. 8.

(21) advantage (Lieberman & Montgomery, 1988) in the host country, mitigate risks (Hisey & Caves, 1985), or to overcome home institutional inefficiencies (Khanna & Palepu, 2000). The disadvantages of CBAs include, among others, possible post-acquisition hazards emerging from integration problems, such as cultural clashes and resistance of the employees, high cost paid, especially in cases of hostile takeover bids, and problems of managing resources and competencies in an unrelated diversification.. 2.2. Ownership in CBAs Although the extant IBV research has been munificent in studying CBAs as an entry mode, the motives to use CBAs to grow internationally, or the challenges imposed by differences in the institutional environments, it has been much less abundant in observing the ownership in CBAs. Nonetheless, when a MNC decides to engage in a CBA it needs to decide the ownership to acquire. The share of ownership acquired by MNCs in CBAs varies as firms may, for instance, acquire 100% of the equity of the target firms (we call these as full acquisitions), or acquire less than 100% of equity in target firms (partial acquisition) (Chen & Hennart, 2004; Chari & Chang, 2009). Examining the ownership is different from examining the entry modes. The extant literature on entry modes has often included in partial acquisitions deals such as traditional joint ventures (e.g., Hennart, 1988; Brouthers & Hennart, 2007), yet there are important differences between the two (Chari & Chang, 2009). While traditional joint ventures are a greenfield entry mode that involve the creation of a new venture, partial acquisition is not a greenfield venture (Brouthers & Hennart, 2007; Chari & Chang, 2009). Also, in partial acquisitions control is exercised through board seats in the target firm whereas in traditional joint ventures the control is negotiated in the joint venture board (Das & Teng, 2000). In addition, in partial acquisitions scaling up to full ownership or exiting the venture is easier than in traditional joint ventures, which have to negotiate with the partner firm (Inkpen & Beamish, 1997). In this study we consider two possible ownership decisions: full versus partial acquisitions (Brouthers & Hennart, 2007). A full acquisition involves buying completely the target firm – and thus the acquirer will become the only proprietor of the target. For example, the buy of 100% of Holcim Ltd (Spain) by Cemex (Mexico) in 2014, and 100% acquisition of AMCI Holding (Australia) by Cia Vale do Rio Doce (Brazil) in 2007. A partial acquisition, on the other hand, entails the acquisition of only part of the equity of the target firm. In these instances, the acquirer will maintain a partner firm. This has occurred for example with the. 9.

(22) acquisition of a 30% stake of Corporacion Centroamericana del Acero in Guatemala, in 2008, by Gerdau SA (Brazil), and the acquisition of a 12,35% stake in the Peru-based Edelnor SA by Enersis SA (Chile) in 2009 (source: SDC Platinum). Whether a firm prefers a full or a partial acquisition is relevant since this choice involve different strategic considerations (Chen, 2008; Lahiri et al., 2014) and influences such issues as the extent of control of the target, hazards in transferring assets or knowledge, the investment requirements and the risk incurred (Chari & Chang, 2009). In fact, the most adequate percentage of ownership to acquire in a CBA is often analyzed in terms of the advantages and costs involved for each level of ownership. Full ownership allows complete control of the operations, whereas in shared ownership the firm has access to complementary resources and the opportunity to share risks and investment (Anderson & Gatignon, 1986; Chari & Chang, 2009). Full ownership entails costs such as greater investments, greater commitment, higher exposure to risks and liabilities of foreignness. While partial ownership includes limited ownership and lack of complete hierarchical control over the operation, problems of post-acquisition integration, costs of partner opportunism and difficulties in the transference of tacit assets (Anderson & Gatignon, 1986; Chari & Chang, 2009). Full acquisitions are overall riskier, costly and irreversible decisions, compared to their partial counterparts. MNCs need to carefully balance the costs and benefits of the two ownership decisions and choose the most beneficial. More specifically, they need to evaluate the synergies and possible gains, but also the investment, costs, uncertainties and risks of each deal. Since the literature on the ownership choices is not novel in strategy and international business studies, we summarize in Table 2.1 some of the major studies that have focused exclusively on the choice between full and partial CBAs. These studies have used different theoretical bases, different empirical contexts and different constructs to explain firms’ choices regarding ownership.. 10.

(23) Table 2.1. Summary of empirical research on full vs. partial ownership in acquisitions Article López-Duarte & GarcíaCanal (2002). Adverse selection and the choice between joint ventures and acquisitions: Evidence from Spanish firms López-Duarte & GarcíaCanal (2004). The choice between joint ventures and acquisitions in foreign direct investments: The role of partial aquisitions and accrued experience.. Research focus. Theoretical lenses. Determinants of the choice between JVs, and full and partial acquisitions. Internalization , Transaction Cost Theory, Knowledgebased theory. The role of different types of acquisitions and MNE accrued experience on the choice between JVs and acquisitions. Chen & Hennart (2004). A hostage theory of joint ventures: why do Japanese investors choose partial over full acquisitions to enter the United States?. Why foreign investors choose partial over full acquisitions of local firms. Reuer et al. (2004). Mitigating risk in international mergers and acquisitions: The role of contingent payouts.. Relationship between ownership stake purchased and likelihood of contingent payout. Chen (2008). The motives for international acquisitions: Capability procurements, strategic considerations and the role of ownership structures.. MNE motives for acquisitions vs. greenfield investments. Constructs/variables. Industry. Main findings. Choice of entry mode; cultural distance; acquisition experience. Construction, manufacturing , services, finance and regulated industries. The choice is conditioned by transaction-cost factors (cultural distance), as well as by the previous experience and internationalization path of the foreign investors.. Not specified. Choice of entry mode; dissimilarity between home- host countries; foreign investors’ proprietary assets; experience. Construction, services, finance and regulated industries. If the country dissimilarity is high, there is a preference for JVs over FAs. On the contrary, as its degree of accumulation of distinctive competencies increases, the foreign investor will prefer FAs over JVs.. Hostage theory. Choice of partial vs. full acquisitions; acquirer R&D capabilities; acquirer marketing capabilities; acquirer industry knowledge, acquirer previous experience in the US; industry R&D intensity; Industry advertising intensity; Industry growth; Industry concentration. Manufacturing. Partial acquisitions create a hostage effect to facilitate ex ante screening of targets and ex post enforcement of contracts.. Not specified. Contingent payouts; inter-industry transaction; high-tech industry; service industry; firm acquisition experience; equity acquired; common law. Manufacturing , services and other. Entry mode choices. Ownership; Capability procurements (R&D intensity, advertising intensity, industry knowledge, host market experience), strategic considerations (industry growth. Not specified. 11. Firms lacking international and domestic acquisition experience turn to contingent payouts when purchasing targets in high-tech and service industries. Firms tend to avoid contingent payouts in host countries with problems with investor protection and legal enforceability. The motives for international acquisitions (vs greenfield investments) are specific to the decision of wholly owned subsidiaries vs JVs Japanese investors self-select their ownership decision..

(24) deviation, industry concentration ). Chari & Chang (2009). Determinants of the share of equity sought in crossborder acquisitions.. Determinants of share of ownership sought by MNEs in CBA. Multiple. Share of equity sought; Different industry local firm; R&D intensity of the local firm’s industry; cultural distance; local firm size; employment contract rigidity; country risk; level of CBA activity in the target country. Malhotra et al. (2011). Curvilinear relationship between cultural distance and equity participation: An empirical analysis of cross-border acquisitions. Relationship between national cultural distance and ownership participation. Not specified. Equity participation; cultural distance; related acquisitions. Lahiri et al. (2014). Crossborder acquisition in services: Comparing ownership choice of developed and emerging economy MNEs in India. Relationship between ownership choice and the type of service, institutional distance, and acquirer’s countryof-origin. Malhotra et al. (2016). Cross-national uncertainty and level of control in crossborder acquisitions: A comparison of Latin American and U.S. multinationals.. How cross-national uncertainty impacts the level of control LA and U.S. MNCs negotiate in CBAs. Multiple. Transaction cost economics. Choice of acquisition; type of service; institutional distance; country of origin effects. Equity ownership; Cultural distance; Institutional distance; Geographic distance. Source: Adapted from Lahiri et al. (2014).. 12. Manufacturing , services and several others. Not specified. The share of ownership sought is influenced by the cost of valuing local firm assets, difficulty in integrating local firm managers in culturally distant countries, the cost of separating desired assets from the rest of the local firm, and the cost of resource commitment under exogenous uncertainty. Cultural distance has a U shaped relationship with ownership participation. Acquiring firms take a higher ownership stake for a given cultural distance if the acquisitions are in a related industry.. Services. Services and high institutional distance increases the likelihood of full acquisition by EE acquirers. Acquirers from developed economies show preference for partial acquisition under similar circunstances.. Manufacturing , services and several others. MNCs' propensity to use shared as opposed to full ownership increases as cultural, geographic and institutional distances increase. These relationships are significantly weaker for LAMNCs than for U.S. MNCs. LAMNCs show a greater propensity for for full ownership as cross-national uncertainty increases..

(25) 2.3. The Institution-Based View The Institution-Based View (IBV) has become a major perspective in the social sciences (Scott, 1995) emerging as a leading movement in management research (Dunning & Lundan, 2008; Peng, Sun, Pinkham & Chen, 2009). The term “Institution-Based View” was coined by Peng (2002) inspired by both economic (North, 1990) and sociological (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Scott, 1995) perspectives of the institutional theory literature, which in the vision of Peng (2002) are complementary. Thus, the IBV is among the currently most frequently referenced theoretical basis in management studies and in international business/strategy research. Specifically, IBV brings together distinct lines of research that have interest in the interaction between MNCs and the institutional environments, at different levels of analysis – such as country-, industry- and firm-level (Meyer & Peng, 2005; Peng et al., 2008). Recently, Peng et al. (2009) proposed the “strategy tripod”, with the IBV as the third leg, thus recognizing the important role of institutions in strategy research in addition to the industry- and the resource-based perspectives. In International Business (IB) research the understanding that “institutions matter” is now hardly novel or controversial (Peng & Khoury, 2009). In fact, the challenge in IB research is to specify how institutions matter, under what circumstances do they matter, to what extent, and in what ways (Peng & Khoury, 2009). These questions are put forth in the context of a paramount question in IB: “What determines the international success and failure of firms around the world?” (Peng, 2004). The IBV in IB strategy suggests that the success and insuccess of firms around the world are enabled and constrained by institutions (Peng, 2004). The fact then is since firms have been increasingly investing outside their national boundaries, they started facing both significant challenges and opportunities in external environments that differ from their own domestic market environment. Furthermore, the challenges did not emerge only from the well known cultural differences or the economic dimensions usually observed by the economists such as the level of economic development, tariff and non-tariff barriers, other restrictions to trade and the flows of capital, or even the regulatory shifts imposed by local governments. This conscience raised the interest of scholars in studying the multifaceted influence of a larger array of institutions on MNCs’ decisions, strategies (Peng et al., 2008) and performance. The progresses made have led to a better understanding of the role of institutions, the different types of institutions and a core construct in an institutional perspective: firms’ struggle to obtain legitimacy in the host countries (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999). Now, we understand well that the impact of institutions in IB strategy is pervasive, because institutions are capable of shaping the behaviors of multiple actors (i.e., individuals,. 13.

(26) firms and industries) (Peng & Khoury, 2009). In turn, actors pursue their interests and make choices in a given institutional framework (Peng & Khoury, 2009). Hence, institutions are essential for the strategies and operations of firms (Meyer & Peng, 2005; Peng et al., 2008). North (1990: 3) defined institutions as the “rules of the game” and the “humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic and social interaction”. Similarly, Scott (1995: 33), defined institutions as the “regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive elements that, together with associated activities and resources, provide stability and meaning to social life”. Institutional environments are characterized by “the elaboration of rules and requirements to which individual organizations must conform in order to receive legitimacy and support” (Scott, 1995: 132). Consequently, Davis and North (1970: 6) defined the “institutional framework” as “the set of fundamental political, social, and legal ground rules that establishes the basis for production, exchange, and distribution”. North (1990) advanced a simpler classification of formal and informal institutions to which firms must adapt to survive and prosper. Moreover, institutions reduce uncertainty by determining the norms of firms’ behaviors and defining what is legitimate. That is, the institutional environments are largely exogenous to firms, usually comprising political, economic, cultural and social dimensions of national and industry institutions (Oliver, 1991), albeit more recent conceptualizations have advanced more comprehensive taxonomies of what is entailed in the institutional environments of countries. Understanding what are institutions is relevant as is relevant the understanding of the types, or sorts, of institutions that firms will encounter in a host foreign country. To obtain legitimacy, firms need to conform to the prevailing set of institutional guidelines, formal or informal and in the many dimensions of economy, demography, legal and regulatory frameworks, and so forth. Firms strategic choices are inherently influenced by the formal and informal constraints of a given institutional framework (North, 1990). That is, the institutional frameworks interact with firms and signal which choices are acceptable and supportable, helping firms to reduce uncertainty (Peng, 2002). Formal constraints comprise political rules, judicial decisions and economic contracts, while informal constraints include socially sanctioned norms of behaviors, culture and ideologies (North, 1990). North (1990) claimed that in situations where formal constraints fail, informal constraints emerge to reduce uncertainty and provide constancy to firms. Uncertainty clouds the judgment of actors that is why institutions can provide rationale that justifies compliance with a norm (Peng, 2002). A frequently used taxonomy of institutions in IB research was advanced by Scott (1995). Scott proposed three pillars – regulatory, normative and cognitive – for managers. 14.

(27) more easily monitor the environment. The regulatory pillar refers to setting, monitoring and enforcement of rules (North, 1990). The normative pillar prescribes the desirable goals and how to attain them (Scott, 1995). The cognitive pillar is related to internal representation of the environments by actors (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Scott further argued that these three pillars of the institutional environments are based on different types of motivation – coercive, mimetic and normative -, and differ in the degree of formalization (Scott, 1995), exerting dissimilar pressures on firms (Oliver, 1991). Strategy scholars have predominantly focused on the effect of the cognitive institutional pillar on firm strategy (Lieberman & Asaba, 2006), disregarding the normative and regulatory pillars. Conversely, IB scholars have been more focused in the normative and regulatory pillars (Ang, Benischke, & Doh, 2015), forgetting the cognitive pillar. An important addition to the IBV came from the work of DiMaggio and Powell (1983: 150) and the suggestion that firms respond to uncertainty and legitimate current decisions by adopting mimicking behaviors. That is, under conditions of uncertainty, such as unfamiliarity with the host country institutional environment, firms tend to imitate other firms that either seem to be successful, that also operate in the host country, the competitors, and so forth. In essence, this means that more than pursuing their own strategies, firms mimic - i.e., adopt similar behaviors, follow identical strategies or prefer a given structural arrangement - prior decisions, their own or those of other firms. DiMaggio and Powell went further to identify three mechanisms through which institutional isomorphic changes occur: (1) coercive isomorphism - stemmed from political influence and problem of legitimacy, (2) mimetic isomorphism - results from responses to uncertainty, and (3) normative isomorphism associated with professionalization. In sum, in some contexts firms tend to adopt isomorphic behaviors in an attempt to conform to the norms, rules, belief systems and “ways of doing things” in the host institutional environment. We expand further on mimetism in the following section.. 2.3.1. Mimetic isomorphism Mimetic isomorphism refers to the process of firms becoming similar to other firms through imitation (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Haveman, 1993). It is the process by which firms are pressured to model themselves after each other (Lieberman & Asaba, 2006), given the institutional constraints. The more MNCs see other MNCs taking an action and perceive this action as the reason for their success in a given institutional environment, the more likely it is the MNC to imitate the other, - regarding such decisions as governance models, location. 15.

(28) and entry mode strategies -, thus becoming similar. Or, as stated by Cyert and March (1963), firms, when faced with uncertainty, replicate prior decisions made by other firms, to replace the specialized capabilities it may lack with the collective wisdom of other firms. Mimetic isomorphism argues that, when facing uncertainty, MNCs tend to assume similar behaviors by imitating other MNCs to gain additional information and legitimacy (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Besides trying to obtain legitimacy as a way to enhance reputation, MNCs pursuit of legitimacy may be seen as local compliance as a mean of acceptance and survival (Oliver, 1991). One strategy of acceptance and survival is acquiescing with the environment, by imitating or mimicking others. Haunschild and Miner (1997) proposed three types of imitative behavior - frequencybased, trait-based, and outcome-based imitation. Frequency-based imitation refers to the propensity to firms imitate a given strategy that have been adopted by a large number of other firms. It is the purest form of mimetic isomorphism, because the firm decision is based on the sheer number of other users, determining the attractiveness of the strategy. Frequency-based imitation has been observed in organizational studies of market entry (Haveman, 1993), corporate governance (Palmer et al., 1993) and entry mode choice (Lu, 2002). Trait-based imitation refers to the practices previously used by other firms with certain traits, such as, for instance, large size. Trait-based imitation has a higher degree of technical efficiency than frequency-based imitation, because the information conveyed by the actions of similar firms, has more relevance to the decision of the focal firm (Haunschild, 1993). Is also a more selective mimetic process than frequency-based imitation, because the firm models itself after considering a subset of firms with specific characteristics. For instance, the firm may consider a subset of firms based on their success. Successful firms are more likely to be imitated, since they are highly visible and success is a trait that firms want to achieve. The inherent logic is that a decision used by a successful firm is likely to have a positive outcome if imitated (Lu, 2002). Haveman (1993) found that when a new market attracted a highly number of profitable thrift banks, the likelihood of a thrift bank enter that market increased. Haunschild and Miner (1997) observed that the use of an investment banker in acquisitions was positively related to the size and success of other firms that used a banker. Lu (2002) applied trait-based to the entry mode context and found that firms do imitate the entry mode choices of successful firms and subsidiaries. Outcome-based imitation is the third selective mimetic process. Such as in trait-based imitation, firms seek to ascertain the success (that is the outcome) of a given decision or action by other firms, to identify who to imitate. Outcome-based imitation is the type of. 16.

(29) imitation richer in technical considerations. Haunschild and Miner (1997) empirically observed that outcome-based imitation occurred in acquisitions in the U.S., where investment banker choices were driven by the size of the acquisition premiums. Lu (2002) proposed that outcome-based imitation influences entry mode choice, and concluded that firms place a lot of importance on outcome indicators, such as the “success rate” of past actions, when choosing who and what to mimic. MNCs adopt a mimetic behavior for two main reasons: to follow others that they perceive as having superior information - information-based explanation -, and to maintain competitive parity or limit rivalry - competitive rivalry-based explanation (Lieberman & Asaba, 2006). An information-based explanation links the propensity to engage in mimetic behavior to the conditions in the firm’s environment in which the action or decision is made (for example, the industrial and geographic setting). Conversely, a competitive rivalry-based explanation focuses on the conditions of the home environment of the firm as the primary influence on mimetic behavior. That is, firms imitate others to maintain their relative position or to neutralize the aggressive actions of rivals. These two explanations are complementary, insofar as information based explanation of mimetic behavior focus on the host country environment into which the firm is expanding, without considering the influence of the firms’ home environment. On the other hand, competitive rivalry-based explanation focuses on the conditions of the home country institutional environment, but not on the host country environment. There are a number of previous studies in IB already delving into mimetic behaviors in such aspects as market entry (Guillén, 2002; Delios et al., 2008), branching (Barreto & Baden-Fuller, 2006), timing (Delios et al., 2008), foreign entry location decisions (Yang & Hyland, 2012), choice of entry mode (Davis et al., 2000; Wu, 2002; Gimeno et al, 2005; Ang et al., 2015), specifically on international joint ventures (Li & Parboteeah, 2015), M&As (Yang & Hyland, 2006, 2012) or alliance formation (Garcia-Point & Nohria, 2002). These studies have advanced remarkably our understanding of how mimetism occurs. For instance, Gimeno et al. (2005) and Delios et al. (2008) have noted that not all firms are equally susceptible to mimetic forces. Guillén (2002) showed that imitation among firms from the same home country industry increases the rate of foreign expansion, although the imitation effects decrease after the first entry. Gimeno et al. (2005) argued that firms mimic the entry moves of prior firms, when both of the firms have large shares in the same domestic market. Wu (2002) contended that firms copy their own entry modes as well as those of other firms. Yang and Hyland (2012) found that not all CBAs decisions react to imitation in the same way. 17.

(30) and that mimetic isomorphism is strengthened by environmental instability but weakened by firms own experience. Finally, Garcia-Point and Nohria (2002) claimed that firms imitate the strategic behavior of firms in the same strategic niche rather than the behavior of firms in their industry. That is, the manner in which mimetism occurs, the extent of mimetism and who are the referents chosen to imitate varying across industries and across time as firms accumulate experience. The extent research has even analyzed mimetic behavior as an incentive to undertake CBAs (see Table 2.2), but, to the best of our knowledge, only three studies have examined the influence of mimetic isomorphism on the ownership choices in CBAs (Yang, 2009; Yang & Hyland, 2012; Xie & Li, 2016). Yang (2009) concluded that there was a negative relationship between time, regulation policy and ownership, and a positive relationship between industry failure experience and ownership. Yang and Hyland (2012) shown that Chinese firms with more experience in CBAs were more likely to display the lowest similarity in this decision, when they observe an increase of the completed deals by other Chinese firms and they can tell what the most popular decision is. Finally, Xie and Li (2016) investigated imitation of the ownership share sought in such acquisitions (privately- vs. state-owned). Results revealed that state-owned firms are less likely to imitate in general, and that both state and privately-owned Chinese acquirers prefer to imitate privately-owned acquirers previously invested in the same environment.. 18.

(31) Table 2.2. Summary of empirical research of mimetic isomorphism in acquisitions Article. Research focus. Haunschild (1993). Interorganizational imitation: The impact of interlocks on corporate acquisition activity. Examine the influence of inter organizational imitation on corporate acquisitions.. Baum et al. (2000). Making the Next Move: How experiential and vicarious learning shape the locations of chains' acquisitions. Examine acquisitions by multiunit chain organizations to determine why they acquire a particular target rather than others that are available to them.. Yang & Hyland (2006). Who do firms imitate? A multilevel approach to examining sources of imitation in the choice of mergers and acquisitions. Explore various sources of imitation, by taking a multilevel perspective.. Xia et al. (2008). Mimetic entry and bandwagon effect: The rise and decline of international equity joint venture in China Yang (2009).. Examine how mimetic entry within reference groups and the emergence of a competing strategy affect the bandwagon phenomenon of a dominant strategy in the context of China. Examine whether. Dependent variable Number of acquisitions completed by the focal firms. Variables of mimetism Director ties - directors of firms sit on the boards of tied-to firms are inside directors of their own firms. Industry 4 industries: electrical equip. manufacturing, transportation equip., wholesale trade, and bus. services. Chain's probability of acquiring a particular independent or component nursing home from among all possible targets. Similarity of target i to a chain's most recent acquisition, acquisition nearest target i, and current components; trait-based imitation of large chains; trait-based imitation of similar chains. Nursing homes. Choice of M&A – related vs. unrelated. Firms’own experience; actions of firms within the same product market; firms in different product markets but within the same industry. Financial service industry. Main findings Results show that firm managers are imitating the acquisition activities of those other firms to which they are tied through directorships. Experiential processes lead chains to replicate themselves by acquiring components geographically and organizationally similar to their own most recent and most similar prior acquisitions and their own current components. Vicarious processes lead chains to imitate location choices of other visible and comparable chains' most recent acquisitions, prior acquisitions nearest to potential targets, and their current components. Results show that 3 levels of imitation occur independently and simultaneously and have significant impact on the choice of M&As. M&As by firms entering the focal product market, are not significantly associated with the likelihood of an unrelated M&A.. EJV formation (rise and decline). Number of EJVs (M&As) (home country); number of EJVs (M&As) (host country). Non-restricted industries. The impact of home and host-country industry effects is not symmetric between the EJV rise and decline periods. CBAs as a competing strategy has an important impact during the EJV decline period but not the rise period. The interactive effects between EJV and M&A strategies occur only in the host-country industries.. Conformity in. Conformity in CBMAs:. Financial. Not all decisions on CBMAs react to. 19.

(32) Isomorphic or not? Examining cross-border mergers and acquisitions by Chinese firms, 1985-2006.. Moatti (2009). Learning to expand or expanding to learn? The role of imitation and experience in the choice among several expansion modes.. Yang & Hyland (2012). Similarity in crossborder mergers and acquisitions: Imitation, uncertainty and experience among Chinese firms, 19852006.. isomorphism and mimetic, coercive, and normative mechanisms apply to CBMAs initiated by Chinese firms.. Examines how firms choose between M&As and alliances vs. internal growth. Specifically, investigate the role of imitation and experience. Examine (1) whether firms from emerging countries imitate each other and become similar on multiple decisions of CBMA; and (2) what factors affect the strength of mimetic isomorphism.. CBMAs: location of the target firm; product relatedness of the acquiring and target firms; ownership structure after M&A; size of the deal. Choice between M&As and alliances vs. internal growth. Degree of similarity in CBA decisions: product relatedness; target’s location; ownership structure. Li et al. (2012). Entry mode decisions by emerging market firms investing in developed markets.. Explain the entry mode decisions (JV, acquisition, greenfield) of emerging-market firms into developed markets. Mode of entry (JV, acquisition or greenfield). Yang & Hyland (2015). Re-examining mimetic. Analyze multiple decisions in M&As. Degree of similarity in M&A: location of. location of the target firm; product relatedness of the acquiring and target firms; ownership structure after M&A; size of the deal. Number of M&As carried out by other firms in the sample; number of alliances formed by other firms in the sample; number of M&As (alliances) formed by a specific firm. Power for imitation: number of completed deals during the prior year; clarity of the most popular choice in a specific CBMA decision. Prior home JV (acquisition, greenfield) entries; prior emergingmarket JV (acquisition, greenfield) entries; Prior developed-market JV (acquisition, greenfield) entries. Degree of similarity in M&A: location of the. 20. industry, manufacturing industry, services and utility industries. forces of conformity in the same way. Overtime, the overall degree of conformity in CBMAs decreases. Factors that significantly affect the degree of conformity include the experiences of failure other firms in the industry, regulatory changes, and membership or entry into the WTO.. Global retail industry. The choice of expansion mode is highly influenced by competitor moves. The results also show that imitation mechanism differ whether we consider M&As or alliances.. Financial industry, manufacturing industry, services and utility industries. Mimetic isomorphism in CBMAs is partially supported. Specifically, the degree of similarity in the product relatedness and the location of target firms increases when the number of completed deals initiated by others increases and when firms can tell what the most popular decision choice is. Not all CBMA decisions react to the force of imitation in the same way. Mimetic isomorphism is strengthened by environmental instability but weakened by firms' own experience.. Not specified. The results support an isomorphism-based framework with different influences across reference groups by country of origin and entry mode. Authors found a dominant form of isomorphism, even after controlling for transaction costs and resource-based explanations.. Financial service industry. Support is found for the mimetic isomorphism argument. Furthermore, firm.

(33) isomorphism: Similarity in mergers and acquisitions in the financial service industry.. Ang et al. (2015). The interactions of institutions on foreign market entry mode.. Xie & Li (2016). Selective imitation of compatriot firms: Entry mode decisions of emerging market multinationals in crossborder acquisitions.. strategy to verify whether isomorphism appears in these decisions when a firm imitates others. Also determine under what conditions the link between imitation and the degree of similarity in M&As is weakened. Examine the interaction effects of institutional differences in the cognitive, normative and regulatory domains on CBA and alliance formation.. Investigate imitation in CBAs by emerging market multinationals in terms of the equity share sought in such acquisitions.. the target firm, product relatedness between the acquiring and target firms, size of the deal. Governance mode (acquisition vs. alliance). Majority- ownership CBA. target firm, product relatedness between the acquiring and target firms, size of the deal. experience and local market segmentation weaken the positive relationship between imitation and the degree of similarity in M&As.. Mimicking foreign firms; mimicking local firms. Manufacturing sector. Results found significant mimicking (cognitive domain) of local firms’ choice of ownership modes by EE firms. Also, regulatory distance (regulatory domain) moderates the mimicking of both foreign and local firms while normative distance does not have any moderating effect.. Not specified. Results show that state-owned (SO) Chinese firms are less likely to imitate in general. Both SO and privately-owned (PO) acquirers are most likely to imitate PO acquirers previously invested in the same environment. For SO acquirers, more frequent pursuit of a particular target share by earlier SO acquirers decreases the likelihood of later SO investors buying a similar share.. Prior home country majority CBAs; prior developed region majority CBAs; prior home country SOE majority CBAs; prior home country non-SOE majority CBAs.. Source: Own elaboration.. 21.

Imagem

Documentos relacionados

The survey involved all the 20 soil profiles sampled for: soil texture and volumetric mass (soil density); soil strength; soil-ma‐ tric water-retention-curve (WRC); porosity of

“O professor que constata que uma noção não foi entendida, que as suas instruções não são compreendidas ou que as atitudes e os métodos de trabalho propostos não

"Conforme lembra Getzels e Csikszentmihalyi (1975), um dos grandes obstáculos à emergência da criatividade como uma área autónoma de estudo, na primeira metade deste século, foi

Estas definições são usadas para classificar o tipo de evolução das comunidades no seu ciclo de vida, e não a cada transição entre pares de instantes de tempo sequenciais..

As informações relativas aos custos de desligamento foram analisadas começando-se pelas entrevistas de desligamento, as quais são realizadas na empresa e se baseiam em

“Na Conferência de São Francisco, quando se estruturou esta Organização, foi o Brasil um dos primeiros e mais ardentes defensores do princípio da flexibilidade da

Existem diversos estudos sobre a forma como uma arquitetura hospitalar bioclimática e com integração com a natureza, pode influenciar favoravelmente o conforto

Comparando as escalas dos subgrupos diagnósticos de Perturbação do sono verificou-se que as crianças com Insónia comportamental apresentavam cotação mais elevada