Trends in Cervical Cancer

Mortality

in the Americas

SYLVIA C. ROBLES,~

FRANKLIN

WHITE,&

ARMANDOPERUGA~

444

This arficle presents an assessment of cervical cancer mortality trends in the Americas based

on PAHO data, Trends were esfimafed for countries where data were available for at least 10

consecutive years, the number of cervical cancer deaths was considerable, and at least 75% of

the deathsfiom all causes were registered. In contrast to Canada and the United States, whose

general populations had been screened for many years and where cervical cancer mortality has declined steadily (to about 1.4 and 1.7 deaths per 100 000 women, respectively, as of 1990), most Latin American and Caribbean countries with available data have experienced fairly con-

stant levels of cervical cancer morfality (typically in the range of 5-6 deaths per 100 000

women). In addifion, several other countries (Chile, Costa Rica, and Mexico) have exhibited

higher cervical cancer mortality as well as a number of noteworthy changes in this mortality

over time.

Overall, while actual declining trends could be masked by special circumstances in some

countries, cervical cancer morfality has not declined in Latin America as it has in developed

countries. Correlations between declining mortality and the in fensity of screening in devel- oped countries suggest that a lack of screening or screening program shortcomings in Latin

America could account for this. Among other things, where large-scale cervical cancer screen-

ing efforts have been instituted in Latin America and Caribbean, these efforts have generally

been linked to family planning and prenatal care programs serving women who are typically

under 30; while the real need is for screening of older women who are at substantially higher risk.

The uterine cervix is the most common

1

cancer site for females in Latin America and the Caribbean, where approximately 52 000 new cases occur annually. Overall in the Americas, where it is estimated that nearly 68 000 new cases occur annually (I), North America exhibits the lowest morbid- ity and mortality. Elsewhere in the Ameri- cas there is considerable variation, with cancer registry morbidity data showing relatively high incidences of cervical can- cer in Brazil, Paraguay, and Peru compared to relatively low incidences in Cuba and Puerto Rico. With regard to mortality, the1 Program on Noncommunicable Diseases, Division of Disease Prevention and Control, Pan American Health Organization, Washington, D.C., U.S.A.

rates are relatively high in the English- speaking Caribbean, Chile, and Mexico and relatively low in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Argentina (2). These differences between countries may be due to both different risk factor prevalences and different cytology screening practices.

A previous study that compared cervi- cal cancer mortality in 1975 and 1985 in countries of the Americas found that mor- tality increased in 12 of 23 countries and decreased significantly only in North America (3). In the United States there was a steady decline among older women in both the incidence of invasive cervical can- cer and cervical cancer mortality, but rates tended to stabilize among women under 40 (4). Overall there is strong evidence of de- cline in the U.S. A study covering the pe-

riod 1947-1984 found cervical cancer rates to be consistently lower and declining among white women Q, while a more re- cent U.S. study documented 66% and 61% declines among American Indians and His- panics, respectively (6).

Limited cytologic screening for cervical cancer was introduced in most countries in the late 1950s and early 1960s within the context of clinical practice. Broader efforts to organize a program in the Canadian province of British Columbia, which got underway in the 195Os, produced note- worthy declines in cervical cancer incidence and mortality over a 30-year period (7). More recently, over the past two decades, several countries have attempted to orga- nize screening programs. Most of them have initiated activities through a central- ized office, usually located within the Min- istry of Health. Some degree of success has been reported, particularly in urban areas of medium- to high-income countries; but the common denominator is difficulty reaching the population at risk (8), that is, middle-aged women of low socioeconomic status.

The efficacy of cervical cytology at the individual level has been indicated by three case-control studies, which have found it to have a protective effect against invasive cervical cancer in the Latin American context (9-11). Nonetheless, true demon- stration of effectiveness would require a collective approach in the form of an orga- nized population-based program, the im- pact of which would be reflected in declin- ing incidence and mortality trends.

Measurement of mortality trends may be difficult in some countries where the qual- ity of death registration is not high. In the Americas, out of 25 countries for which mortality data are available, at least 20% of all deaths are not registered in nine; and in 15 over 10% of the registered deaths are attributed to “signs, symptoms and ill- defined conditions” (12). In general, under- registration of deaths and death certifica-

tion inaccuracies tend to be higher among people over 65 years old and among women.

In contrast to cervical cancer mortality data, long-term incidence data are not avail- able in Latin America and the Caribbean- either because cancer registries are rela- tively new or because they have not continued operating at the required level of quality. In addition, important changes in diagnostic criteria have occurred over the past 20 years, due to differences in cytologic and histopathologic classifications and the introduction of new technical procedures such as colposcopy. At least in principle, these changes have tended to have more impact upon incidence than upon mortal- ity Because of these limitations, we have chosen to describe only trends in mortality.

Since most cervical cancer occurs in de- veloping countries, and since data on mor- tality are needed for program development, monitoring, and evaluation, careful assess- ment of such data’s quality is warranted. In this article we discuss issues and other considerations involved in the use of such data as well as the general cervical cancer situation prevailing in the Region of the Americas.

METHODS

where changes in trends were observed. Rates of change in these trends were esti- mated using the least squares method, rm- der the assumption that the logarithm of the observed rate varied linearly (24). No attempt was made to model age-cohort data, as the graphic display presented suf- fices for the purpose of making intercoun- try comparisons (15).

RESULTS

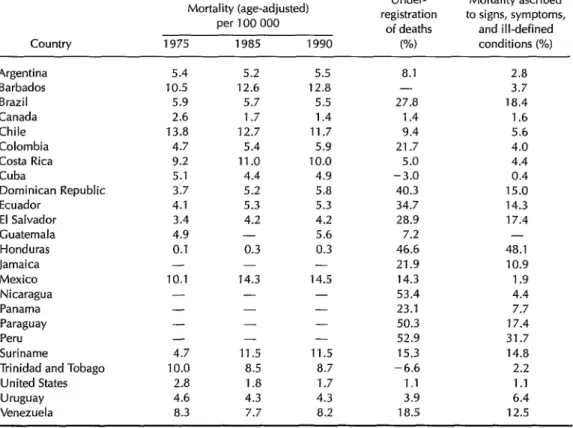

Table 1 shows data on age-adjusted cer- vical cancer mortality, underregistration of overall mortality, and the percentage of deaths attributed to “signs, symptoms, and ill-defined conditions” (International Clas-

sification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, cat-

egories 780-799) in 24 countries of the Americas. Only the United States and Canada appeared to have less than 2% underregistration, seven other countries appeared to have less than 10% under- registration, and the remaining countries had 10% or more. Belize, Guyana, Haiti, and a number of other Caribbean countries are not listed because the number of deaths was too small or because it was not possible to obtain estimates of under- registration. The proportion of deaths at- tributed to “signs, symptoms, and ill- defined conditions” was taken as an indicator of death certification accuracy; as may be seen, 13 countries reported that less

Table 1. Age-adjusted cervical cancer mortality reported for 24 countries of the Americas as of 1975, 1985, and 1990, and indices of the quality of death registration (underregistration of deaths and mortality ascribed to “signs, symptoms, and ill-defined conditions”) in those countries as of 1990 or the closest year with available data.

Country

Mortality (age-adjusted) per 100 000

1975 1985 1990

Under- Mortality ascribed registration to signs, symptoms,

of deaths and ill-defined

W) conditions (%) Argentina Barbados Brazil Canada Chile Colombia Costa Rica Cuba

Dominican Republic Ecuador El Salvador Guatemala Honduras Jamaica Mexico Nicaragua Panama Paraguay Peru Suriname

Trinidad and Tobago United States Uruguay Venezuela 5.4 10.5 5.9 2.6 13.8 4.7 9.2 5.1 3.7 4.1 3.4 4.9 0.1 - 10.1 - - - - -

4.7 11.5

10.0 8.5 2.8 1.8

4.6 4.3 8.3 7.7 5.2 12.6 5.7 1.7 12.7 5.4 11 .o 4.4 5.2 5.3 4.2 - 0.3 14.3 - - - 5.5 12.8 5.5 1.4 11.7 5.9 10.0 4.9 5.8 5.3 4.2 5.6 0.3 - 14.5 - - - - 11.5 8.7 1.7 4.3 8.2 8.1 - 27.8 1.4 9.4 21.7 5.0 -3.0 40.3 34.7 28.9 7.2 46.6 21.9 14.3 53.4 23.1 50.3 52.9 15.3 -6.6 1.1 3.9 18.5 2.8 3.7 18.4 1.6 5.6 4.0 4.4 0.4 15.0 14.3 17.4 - 48.1 10.9 1.9 4.4 7.7 17.4 31.7 14.8 2.2 1.1 6.4 12.5

than 10% of all registered deaths were in this category.

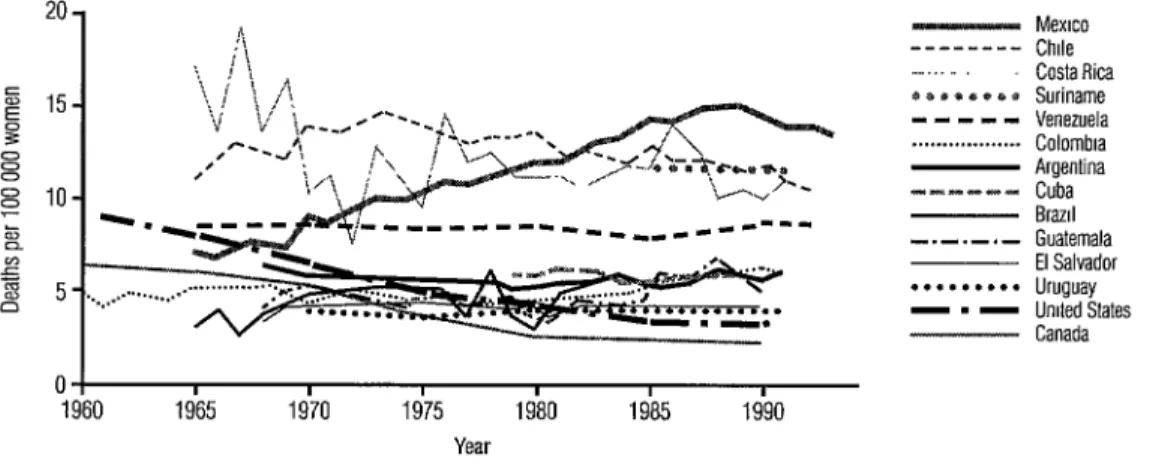

Age-adjusted cervical cancer mortality trends from 1960 to 1993 in 14 countries of the Americas are shown in Figure 1. It may be seen that while Canada exhibited mor- tality similar to that of several LatinAmeri- can countries in the 196Os, a steady decline has been evident since 1965. As a result, Canada currently enjoys the lowest rate in the Region (1.4 deaths per 100 000 women). In contrast, various Latin American and Caribbean countries with rates fairly simi- lar to Canada’s 1960 rate (Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Guatemala, Uruguay, and Venezu- ela) saw their cervical cancer mortality fluctuate at a similar level over the 33-year period without showing significant down- ward trends.

Meanwhile, there were several other Latin American countries (Chile, Costa Rica, and Mexico) that exhibited higher mortality than the rest as well as a number of noteworthy changes over time. Costa Rica showed a decline from 1965 to 1973, after which mortality tended to stabilize at around 10 deaths per 100 000. The large variations observed from year to year are most likely a result of the small number of

cases involved. On the average, Costa Rica reported nearly 118 deaths from cervical cancer annually over the period 1984-1993. In Mexico, cervical cancer mortality in- creased from 1965 onward, remaining fairly steady at around 14 deaths per 100 000 in recent years. Since 1975 Chile has reported a slightly declining trend, on the order of that seen in Canada; but cervical cancer mortality in Chile has remained much higher, in the area of 12 deaths per 100 000 women.

In order to further compare the trends in Chile and Canada, we charted these coun- tries’ age-specific mortality data for differ- ent birth cohorts (Figure 2). This allows one to view cervical cancer mortality patterns for each of six groups of women born in a given period of time. In Chile, no major age- specific differences were found between the different birth cohorts; but in Canada each of the first four cohorts exhibited consider- ably lower age-specific mortality than its predecessor, demonstrating progressively lower risks in successive cohorts as a result of cervical cancer screening.

The case of Costa Rica provides a likely example of patterns ascribable to changes in reporting accuracy. The available data

Figure 1. Annual cervical cancer mortality in selected countries of the Americas, age-adjusted to the world population, 1960-l 993. Source: PAHO/WHO.

- - - - __ _ BBBO~O1)~ m--m- . . . I-mPPP

-.-.-.- . . . -.-

Mexrco Chde Costa Rica Suriname Venezuela Colombra Argentina Cuba Brazd Guatemala El Salvador Uruguay Unded States Canada 0 I I I I I I I

Figure 2. Annual cervical cancer mortality by selected five-year birth cohorts in Canada and Chile, 1960-I 990.

25 - Birth year Canada ---1905-1909

-1915-1919 20 - ... 1925-1929 5 - 1935-i 939 ; ,5- - ---19551959 1945-1949

9

0 I I I I 1 I I I I I I

20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 4549 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 275

Age in years

Age in years

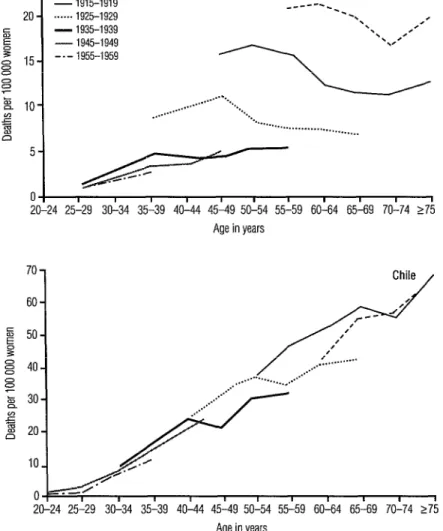

indicate that Costa Rica experienced an important decline in age-adjusted mortal- ity from all causes between 1965 and 1983 (Figure 3), after which overall mortality continued to decline but at a slower pace. Also, beginning around 1982 there was a sharp drop in mortality from “signs, symp- toms, and ill-defined conditions.” Mortal- ity from all cancers (“malignant tumors” in the figure) apparently remained essentially unchanged throughout the 1965-1991 pe- riod, as did cervical cancer mortality; but

deaths from all other uterine cancers exhib- ited a marked decline.

These patterns of cervical and other uter- ine cancer mortality could have been af- fected by better reporting and improved medical care in such a way as to mask a downward trend in cervical cancer mortal- ity. Specifically, if a malignant tumor is

widely disseminated and undifferentiated, it may be difficult to determine whether the primary tumor originated in the cervix or the endometrium, in which case the cause

Figure 3. Mortality from all causes and selected causes (including cervical cancer) among women in Costa Rica, 1965- 1991.

cm---.* /“X

4 \.+All causes

*-r, --- -8 ‘r

‘. Mahgnant tumors 100-k ..-. . . *. . . . . . ..*.*.._.. . . . . ..*...” . . . . -1.. c

. . . . -y* --* ‘& .-_.eem Ill-defined causes ‘x. ‘,/

Cllher uterine cancer,. .,...,

l! , I I I I I I I I I I I I- 196519671969197119731975197719791981 19831985198719891991

Year

of death is reported as being a malignant tumor of the uterine corpus or uterus (un- specified). As an increasing number of women receive medical attention, the can- cer may be detected earlier and is more likely to be correctly diagnosed. Under these circumstances, it is possible that deaths previously attributed to cancer of the corpus uteri or uterus (unspecified) are now being more precisely reported as due to cervical cancer.

To control for this possibility, annual mortality from all uterine cancer (Intema- tional Classification of Diseases, Ninth Re- vision, categories 179- 182) was established for six age groups, and the annual rate of change for each group was calculated for 1961-1991 (Table 2). Significant declines were found to have occurred in all age groups except the one over 74 years old, which showed annual increases averaging 6.8%. The 35-44 year age group experi- enced the largest average mortality decline, -5.8% per annum. Within this context, it should be noted that cancer of the body of the uterus is rare among women under 50; thus, the declining mortality trend among younger women in Costa Rica is likely due

to reduced cervical cancer mortality, a trend masked by improvements in health care and reporting accuracy. The fact that mor- tality from all malignant tumors did not exhibit important changes in this period may be explained partly by increased mor- tality from cancers at other sites, such as the breasts.

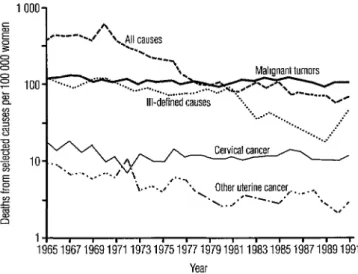

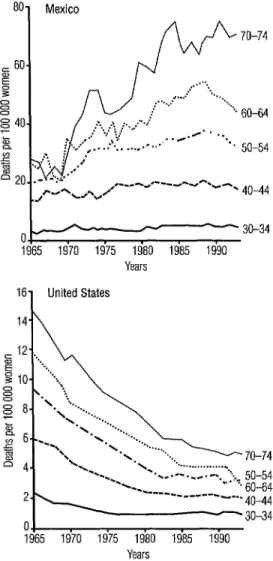

As previously noted, sharply contrast- ing cervical cancer trends have been found in Mexico and the United States. When the increasing Mexican mortality is examined by age group (Figure 4), the increase ap- pears to occur almost entirely among

Table 2. Annual average rates of change in uterine cancer mortality, by age group, in Costa Rica, 1961-l 991.

Age group Average annual (in years) rate of change (%)

Figure 4. Cervical cancer mortality in Mexico and the United States by selected five-year age groups, 1965-I 990.

801 Mexico

oj&fyL-y-- 30-34

1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 Years

16 United States

14 h

--.---_.-.. -

Ol

1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990

women who are at least 50 years old. In younger Mexican age groups (30-34 and 40-44), mortality remained virtually un- changed over a 25-year period. In contrast, the marked decline in cervical cancer that occurred in the United States was reflected in sharply reduced cervical cancer mortal- ity for all age groups except the 30-34 group (Figure 4). In each of these groups a sharp decrease was observed, and even in

the 30-34 group some gains were regis- tered, though cervical cancer mortality in this age group tended to stop declining around 1975.

Table 3 shows the average annual rate of change of cervical cancer mortality in 1960-1993 by age group, as indicated by available data from Canada, Chile, Mexico, and the United States. Marked decreasing trends for all age groups can be seen in the United States and Canada, with the declines being sharpest in the three middle-aged

groups (40-64 years). In Chile, mortality decreased significantly among women 30- 34 years old (by an average of 2.2% per year), but by less (around 1% per year) in the 40-44 and 50-54 groups, and even less in the 60- 64 group, while rising slightly (by 0.7% per year) in the oldest group. In Mexico, average cervical cancer mortality increased in all age groups, the increase being especially marked (3.5% per year) in the oldest (70-74) group.

DISCUSSION

AND

CONCLUSIONS

Cervical cancer mortality has not de- clined in Latin America as it has in devel- oped countries, particularly Canada and the United States. In Chile, declines in mor- tality did occur among younger women in 1960-1993, but these were not so large as those registered in Canada and did not per- tain to older age groups. Chile has reported low underregistration of deaths, and the proportion of deaths attributed to “signs, symptoms, and ill-defined conditions” has remained reasonably steady in recent times (4.9% in 1972, 5.6% in 1992). Therefore, it seems unlikely that more pronounced ac- tual declines have been masked by im- proved reporting and diagnosis, as appears to have been the case in Costa Rica (26).

Another factor that may be influencing cervical cancer mortality is increasing rates of hysterectomy, for which reason it has been argued that adjustments to denomi-

Table 3. Average annual percentage rates of change in cervical cancer mortality, by age group, in Canada, Chile, Mexico, and the United States, 1960-1993.

Age group (in years)

Country 30-34 40-44 50-54 60-64 70-74 Canada

Chile Mexico United States

-3.0 -4.7 -5.6 -4.6 -2.9 -2.2 -1.1 -1.0 -0.4 +0.7 +1.3 +oxs +1.9 +1.6 +3.5 -2.8 -3.7 -3.8 -4.0 -3.4

nators (indicating the number of women at risk) may be necessary (27). There are cur- rently no data directly indicating the im- portance of this factor in Latin America; but if hysterectomy rates were high enough to make a substantial difference, we should be seeing a trend toward lower cervical can- cer mortality than expected, when in fact there were no significant overall changes of this kind.

In Mexico, where cervical cancer mor- tality has been rising, the rise has been con- centrated mainly in older age groups. This is the converse of the situation in the United States, where declines occurring in all age groups have been especially marked in older groups (see Figure 4). While it is not clear whether the high rates among older women in Mexico might be an artifact of improved diagnosis, the existence of such higher rates in Mexico has been affirmed by a lo-year mortality analysis that found a significant increasing trend among women 74 years of age and older (28). This study also noted variations between states and found that 71% of the cancers involved were diagnosed at advanced stages.

Our results suggest that in some Latin American countries decreasing cervical cancer mortality trends may be disguised. There are two possible reasons for this: first, cervical cancer mortality is likely to be de- creasing among young women (under age 40) at the same tune that it is increasing among older women; and second, as al-

ready noted, declines could be masked by improvements in death registration and the accuracy of death certification. Regarding the first point, rising trends among elderly women, very clear in Mexico, were also observed in Chile and Costa Rica. These differentials between young and old may result from concentrating screening efforts on young women while failing to reach older women at higher risk. Regarding the second point, data from the Cali Cancer Registry in Colombia, the longest-standing population-based registry in Latin America

(19), suggest that the incidence of invasive cervical cancer is decreasing in the area cov- ered by this registry, although it is not cer- tam that this trend is occurring in the rest of Latin America.

Clearly, there is a need for further coun- try-by-country studies on cervical cancer incidence and mortality trends, as well as for studies clarifying the role of potential artifacts. We did not analyze trends for all countries, limiting ourselves to trends in three countries with the highest rates that exhibited noteworthy changes over time; nor did we obtain information from coun- tries where a large proportion of all deaths were unregistered. The situation in these

example, while Honduras reported the low- data tend to differ for different population est cervical cancer mortality in the Region groups, nor is there uniform provision of (see Table l), it appears that some 46.6% of health services or access to cervical cancer all deaths in the country were unregistered. screening. It is difficult to document the Moreover, an independent study on causes cervical cancer burden in the least- of mortality among Honduran women 15- developed geographic areas or subpopula- 49 years old found that 12% of all the deaths tions, partly because of poor data quality, studied could be classified as due to “can- but also because lack of accessibility to cer of the uterus” (ZO), which clearly sug- health services precludes poor women from gests a higher rate of cervical cancer mor- being diagnosed, not to mention having an tality than the one reported through routine opportunity to receive adequate treatment.

death registration. In contrast, well-off areas or subpopula-

Usually, trends are described graphically. tions can access health care services more The magnitude of change over a given unit easily and have more medical technology of time is accurately represented by display- available to them for diagnosis and treat- ing the rate of change; and while use of the ment, which in turn reduces morbidity and least squares method (to estimate the slope mortality. This situation is aggravated by of the curve and thus the rate of change) the fact that the incidence of cervical can- assumes that the logarithms of the rates are cer tends to be higher among those of low linear, this method is relatively simple and socioeconomic status. We now know that easy to understand. However, for age-period- some types of human papillomavirus may cohort models or geographic age-specific be a necessary cause, although not a suffi- comparisons, when it is unlikely that the cient one, for development of cervical car- assumption of linearity will hold, it is nec- cinema (24,25); other risk factors, such as essary to use more sophisticated methods high parity and smoking (26), may help to that permit inclusion of interaction terms trigger progression of the disease, while within the model. In the study reported dietary factors such as intake of beta- here, stratification by age made it possible carotene (27, 28) and vitamin C (29) may to examine differences between age groups, have protective effects. These risk factors which is important because cervical cancer tend to be more prevalent in population risk varies with age, and screening practices groups with low socioeconomic status, tend to focus on particular age groups, not which also are likely to have poor dietary necessarily those at highest risk. intake of vitamins.

For the purpose of program monitoring, Although not all changes in cervical can- it may be desirable to follow changing in- cer mortality can be attributed directly to cidence and mortality trends by monitor- screening, early studies in developed coun- ing tracer age groups that are especially tries demonstrated a correlation between sensitive to the effects of screening and declining mortality and screening intensity where screening should be targeted. within (30). More specifically, it has been found this context it should be noted that the tra- that declines in incidence and mortality ditional age-standardized rates can mask have tended to be greater among age changes that are of low magnitude but of groups and birth cohorts subject to screen- public health significance. ing, whereas little change has been ob- In general, Latin American countries served among women not enrolled in a tend to exhibit large within-country differ- screening program (31). Apparently as a ences in cervical cancer incidence and mor- consequence of screening in 12 European tality (12, 21-23). The completeness and countries (32), cervical cancer’s incidence accuracy of such incidence and mortality declined more between 1962-1967 and

1978-1982 in women 35-55 than it did in any other age group. These and other data suggest that the direct benefit from an or- ganized screening program can typically be observed mostly among middle-aged women who remain in the program (33,34).

Self-selection may be playing a role in this, because women at lower risk may be more apt to participate. In addition, the ef- fectiveness of screening is determined partly by the sensitivity of cytology and by the likelihood that women with a positive test will receive a complete diagnostic workup and appropriate treatment (35). All this makes it important that organized screening programs be able to reach women at risk, maintain attendance rates, and pro- vide the mechanisms needed to ensure ap- propriate followup (36). Experience in the Nordic countries has demonstrated that, in the best situations, the incidence of cervi- cal cancer following a negative Pap smear may be reduced by up to 90% (37). There will always be some women in whom the preinvasive lesions cannot be detected; for example, some women may have adeno- carcinoma of the endocervix, which is hard to detect through cervical cytology (38).

Lately in developed countries, cervical cancer incidence and mortality among women under 40 have been observed to level off or even to increase. These trends have been attributed to improved diagnos- tic precision (39), emergence of adenocar- cinema of the cervix in women under 35 years old (40,42), and lifestyle changes in the younger generation that have a bear- ing on the prevalence of risk factors, such as use of oral contraceptives (42); both of the latter could be a problem in America.

In most Latin American and Caribbean countries, efforts to introduce cervical can- cer screening and reach large numbers of women have been linked to family plan- ning and prenatal care programs. Women who seek these services are young, com- monly in their 2Os, and at lower cervical cancer risk than older women. Screening

these women is not cost-effective, partly because of the low incidence of cervical neoplasia in this age group and partly be- cause the age distribution of the female population in Latin America resembles a pyramid with a large base. Thus, there are a large number of women under 30 years old; and if screening resources are concen- trated on them, there may not be enough to screen older women at higher risk who usu- ally have less access to health services (43). As already noted, if cervical cancer screening is properly conceived and ex- ecuted, it can have a pronounced impact on cervical cancer incidence and mortality. Moreover, it can also yield other benefits. Timely treatment for cervical cancer can improve a woman’s quality of life and en- able her to remain or enroll in the work force. In addition, women who are screened are more likely to receive medical exami- nations and be subject to other clinical pre- ventive measures (44). Thus, the cervical cancer screening provided by an organized program may also provide an opportunity to increase health care access for women who are not in their prime reproductive years. If this can be achieved in Latin America and the Caribbean, reductions in disease incidence and mortality due not only to cervical cancer but also to other causes are likely to occur.

REFERENCES

Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide incidence of 18 major can- cers in 1985. Int I Cancer 1993;54:594-606.

Restrepo HE, Gonz&lez J, Roberts E, Litvak

J. Epidemiologia y control de1 cancer de1 cuello uterino en America Latina y el Car- ibe. Bol Oficina Sanit Panam 1987;102:578- 592.

Restrepo HR. Cancer epidemiology and con- trol in women in Latin America and the Caribbean. In: Pan American Health Orga- nization. Women in health and development.

4. Devesa SS,Young JL, Brinton LA, Fraumeni JF. Recent trends in cervix uteri cancer. Can- cer 1989;64:2184-2190.

5. Devesa SS, Silverman DT, Young JL, et al.

Cancer incidence and mortality trends

among whites in the United States, 1947- 1984. ] Nat1 Cancer lnst 1987;79:701-770. 6. Chao A, Becker TM, Jordan SW, Darling R,

Gilliland FD, Rey CR. Decreasing rates of

cervical cancer among American Indians and Hispanics in New Mexico (United States). Cancer Causes Control 1996;7:205-215.

7. Anderson GH. Organization and results

from the cervical cytology screening pro- gramme in British Columbia, 1955-85. Br Mea J 1988;296:975-978.

8. Restrepo H. Detection de cancer gine-

coldgico en America Latina. Washington,

DC: Programa de Promotion de la Salud,

Organization Panamericana de la Salud;

1991. (Document HPA/NCD/INF V-8m

1991).

9. Aristizabal N, Cuello C, Correa P, Collazos

T, Haenszel W. The impact of vaginal cytol- ogy on cervical cancer risk in Cali, Colom- bia. Int J Cancer 1984;34:5-9.

10. Herrero R, Brinton LA, Reeves W, et al.

Screening for cervical cancer in Latin

America. Int J Epidemiol1992;21:1050-1056.

11. Hernandez-Avila M, Lazcano-Ponce EC,

Alonso de Ruiz I’, et al. Evaluation de1

programa de detection oportuna de1 cancer de1 cuello uterino en la Ciudad de Mexico: un estudio de cases y controles. Gac Med Mex 1994;130:201-209.

12. Pan American Health Organization. Health

statistics in the Americas. Washington, DC:

PAHO; 1992. (Scientific publication 542).

13. United Nations. World population prospects. New York: UN; 1991.

14. Esteve J, Benhamou E, Raymond L. Statisti- cal methods in cancer research: volume IV, de- scriptive epidemiology. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1994. (Sci-

entific publication 128).

15. Tufte ER. The visual display of quantitative in- formation. Cheshire: Graphic Press; 1983.

16. Beral V, Hermon C, Mtioz N, Devesa SS.

Cervical cancer. In Cancer surveys: volumes 19 and 20, trends in cancer incidence and mor-

tality. London: Imperial Cancer Research

Fund; 1994.

17. Lyons JL, Gardner JW. The rising frequency

of hysterectomy: its effects on uterine can-

cer rates. Am J Epidemiol1977;105:439-443.

18. Lazcano-Ponce EC, Rascon-Pacheco RA,

Lozano-Ascencio R, Velasco-Mondragon

HE. Mortality from cervical carcinoma in

Mexico: impact of screening, 1980-1990. Acta Cytol 1996;40(3):506-512.

19. International Agency for Research on Can-

cer. Volumes III, IV, and VI: cancer incidence in five continents. Lyon: World Health Organi-

zation, IARC; 1976-1992. (WHO/IARC

publications 15,42,89, and 120).

20. Castellanos M, Ochoa JC, David V.

Mortalidad de mujeres en edad reproductiva y

mortalidad materna, 1990. Tegucigalpa:

UNAH, MSP, OPS, UNFPA, MSH; 1990. 21. Reeves WC, Brenes MM, B&on RC, Valdes

PF, Joplin CFB. Cervical cancer in the Re- public of Panama. Am J Epidemiol1984;119: 714-724.

22. Sierra R, Rosero-Bixby L, Antich D, Mtioz G. Clincer en Costa Rica: epidemiologia descriptiva. San Jose: Editorial Universidad de Costa Rica; 1995.

23. Vasallo JA. Clincer en el Uruguay no 2.

Montevideo: Registro National de Cancer;

1991.

24. Mtioz N, Bosch FX, De Sanjose S, et al. The

causal link between human papillomavirus and invasive cervical cancer: a population- based case control study in Colombia and Spain. Int J Cancer 1992;52:743-749.

25. Schiffman MH, Bauer HM, Hoover RN,

et al. Epidemiologic evidence showing that

human papillomavirus infection causes

most cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. JiVatZ

Cancer Inst 1993;85:958-964,

26. Herrero R, Brinton LA, Reeves WC. Factores de riesgo de carcinoma invasor de1 cuello uterino en America Latina. BoZ Oficina Sanit Panam 1990;1:6-26.

27. Verrault R, Chu J, Mandelson M, Shy K.

A case control study of diet and invasive cervical cancer. Int J Cancer 1989;43:1050- 1054.

28. Herrero R, Potischman N, Brinton LA, et al. A case control study of nutrient status and invasive cervical cancer: I, dietary indica- tors. Am J Epidemiol1991;134:1335-1346.

29. Slattery ML, Abbott TM, Robinson LM,

et al. Dietary vitamins A, C, and E and sele- nium as risk factors for cervical cancer. Epi- demiology 1990;1:8-15.

30. Miller AB, Lindsay J, Hill GB. Mortality from cancer of the uterus in Canada and its rela- tionship to screening for cancer of the cer- vix. Int J Cancer 1976;17:602-612.

31. Nieminen P, Kallio M, Hakama M. The ef-

fect of mass screening on incidence and

mortality of squamous and adenocaminoma of cervix uteri. Obstet GynecoZ1995;85:1017- 1021.

32. Ponten J, Adami HO, Bergstrom R, et al. Strategies for global control of cervical can- cer. Int ] Cancer 1995;60:1-26.

33. Celentano DD, Klassen AC, Wiesman CS, Rosenhem NB. Duration of relative protec- tion of screening for cervical cancer. Prevent Med 1989;18:411-422.

34. Lynge E, Poll l? Incidence of cervical cancer

following a negative smear: a cohort study

from Maribo County, Denmark. Am ]

Epidemiol1986;124:345-352.

35. Chamberlain J. Reasons that some scmen-

ing programs fail to control cervical cancer. In Hakama M, Miller AB, Day NE, eds. Screeningfor cancer of the uterine cervix. Lyon:

International Agency for Research on Can-

cer; 1986:161-164.

36. Miller AB. Cervical cancer screening

programmes: managerial guidelines. Geneva:

World Health Organization; 1992.

37. Hakama M. Screening for cervical cancer. In:

Miller AB, ed. Advances in cancer screening. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996. (Cancer treatment and research series).

38. Boon ME, Baak JPA, Kurver PJH, Overdiep

SH, Verdonk GW. Adenocarcinoma in situ

of the cervix. Cancer 1981;48:768-773.

39. Brinton LA, Reeves WC, Brenes MM, et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of invasive cervical cancer. lnt ] EpidemioZ1990;19:4-11.

40. Schwartz SM, Weiss NS. Increased incidence

of adenocarcinoma of the cervix in young

women of the United States. Am J EpidemioZ 1986;1241045-1047.

41. Peters RK, Chao A, Mack TM, Thomas D,

Bernstein L, Henderson B. Increased fre-

quency of adenocarcinoma of the uterine

cervix among young women in Los Ange- les County J Nat2 Cancer Inst 1986;76:423-

428.

42. Chilvers C, Mant D, Pike MC. Cervical ad-

enocarcinoma and use of oral contracep-

tives. Br Med J 1987;295:1446-1447.

43. Eardley A, Elking K, Spencer B, et al. Atten-

dance for cervical screening, Whose prob- lem? Sot Sci Med 1985;955:340-351. 44. Hueston WJ, Stiles MA. The Papanicolaou

smear as a sentinel screening test for health

screening in women. Arch Intern Med

1994;154:1473-1477.