DOI: 10.1590/0004-282X20150073

ARTICLE

Increased multiple sclerosis relapses related

to lower prevalence of pain

Aumento nos surtos de esclerose múltipla relacionado com menor prevalência de dor

José Vinícius Martins da Silva1, Beatriz Fátima Alves de Oliveira2, Osvaldo José Moreira do Nascimento1, João Gabriel Dib Farinhas1, Maria Graziella Cavaliere3, Henrique de Sá Rodrigues Cal1, André Palma da Cunha Matta1

While several studies have found a relationship for the development of pain related to one or more multiple scle-rosis (MS) factors such as patient’s age, duration of disease, disease course, and disability1,2,3, virtually an equal number

have not4,5. Pain clearly has a role in the disease as its

prev-alence has been reported ranging up to 74% in MS outpa-tients6. While research does implicate factors that may be

related to pain, multivariate analyses are lacking, which leaves the issue unclear as to the role of the various risk fac-tors in the development of pain6. he development of MS

pain and its severity has implications into the general

evo-lution of the disease which itself varies amongst the difer -ent clinical forms [relapsing-remitting- (RR), primary pro-gressive- (PP) and secondary propro-gressive- (SP)] as well as its

gender-speciic presentation.

his study investigates the prevalence and severity of

pain amongst multiple variables in attempt to further elu-cidate the role of pain within the evolution of MS. Our goal is to evaluate these results within the context of the recent mechanisms of MS that have addressed not only gender

1Universidade Federal Fluminense, Departamento de Neurologia e Centro de Pesquisas Clínicas em Neurologia/Neurociência, Niteroi RJ, Brazil; 2Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro RJ, Brazil;

3Universidade Federal Fluminense, Interna da Disciplina de Neurologia, Niteroi RJ, Brazil.

Correspondence: André P. C. Matta; Av. Marquês de Paraná 303; 24033-900 Niterói RJ, Brasil; E-mail: andrepcmatta@hotmail.com Conflict of interest: There is no conlict of interest to declare.

Funding: This research was partially funded by Biogen Idec, Inc. Grant number: BRA-AVX-11-10219. Received 06 January 2015; Received in inal form 27 February 2015; Accepted 20 March 2015. ABSTRACT

Objective: The study aims to investigate the presence of pain amongst multiple sclerosis (MS) patients. Method: One hundred MS patients responded to questionnaires evaluating neuropathic and nociceptive pain, depression and anxiety. Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann–Whitney U, Chi-Square and two-tailed Fisher’s exact tests and multivariate logistic regression. Results: Women had a statistically higher prevalence of pain (p = 0.037), and chances of having pain after the age of 50 reduced. Women with pain had a statistically signiicant lower number of relapses (p = 0.003), restricting analysis to those patients with more than one relapse. After the second relapse, each relapse reduced the chance of having pain by 46%. Presence of pain was independent of Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) anxiety, and depression. Conclusion: Our indings suggest a strong inverse association between relapses and pain indicating a possible protective role of focal inlammation in the control of pain.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, pain, prevalence, relapses, gender.

RESUMO

Objetivo: O estudo tem como objetivo investigar a presença de dor entre pacientes com esclerose múltipla (EM). Método: Cem pacientes com EM responderam a questionários avaliando dor neuropática e nociceptiva, depressão e ansiedade. A análise estatística foi realizada através dos testes de Mann-Whitney U, Qui-Quadrado, two tailed Fisher exact test e regressão logística multivariada. Resultados: As mulheres apresentaram estatisticamente uma maior prevalência de dor (p = 0,037), e as chances de ter dor após a idade de 50 reduziram. As mulheres com dor tinham um número com signiicância estatística reduzido de surtos (p = 0,003), restringindo a análise aos pacientes com mais de um surto. Após o segundo surto, cada surto reduziu a chance de ter dor em 46%. A presença de dor foi independente da Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) ansiedade e depressão. Conclusão: Nossos resultados sugerem uma forte associação inversa entre o surto e a dor, indicando um possível papel protetor da inlamação focal no controle da dor.

issues but also the relationship of relapses to long term disability and the progression of RR to SP, implicating two distinct disease phases related to late outcome. We hope to provide further insight into the relationship of pain to these end-points and its possible role in the natural history of the disease.

METHOD

Procedure

In this cross-sectional clinic based study we admin-istered a questionnaire to 100 consecutive MS patients.

he questionnaire included a total of 65 questions, which

included the Brazilian-portuguese validated question-naires DN47 (Neuropathic Pain in 4 questions),the LANSS8

(Leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)9 and Anxiety (BAI)9, a

pain questionnaire and disease related information. he

survey was given to each patient at the end of their physi-cian consult to complete independently, with no time

con-straints. Statistical analysis was then performed. his study

was approved by the Ethics committee of the Department of Neurology at the Antonio Pedro University Hospital – Fluminense Federal University in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study sample

One-hundred consecutive MS patients met the inclu-sion and excluinclu-sion criteria at the Antonio Pedro University Hospital in the Department of Neuro-immunology. Inclusion criteria: diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (all clinical courses) based upon the McDonald’s criteria10 age between 18 and 80

years old, medication possession rate > 80%. Exclusion crite-ria: having other known neurological conditions, cancer, re-nal disorders, psychiatric disorder and diabetes.

Pain questionnaire

he 13 questions structured questionnaire was based on

Grau-López3. his self-reported data evaluated the presence

of pain; its location including head, upper extremities, lower

extremities, back or generalized; its classiication as constant

or intermittent; its frequency (daily, more than 3 times per week, less than 3 times per week, or 1-3 times per month); presence of Lhermitte’s phenomenon; types of head pain in-cluding migraine, tensional and trigeminal neuralgia; medi-cation used for MS; medimedi-cation used for pain.

Classification of pain type

Pain was classiied as either neuropathic or nociceptive. Neuropathic pain was deined as having a score of 4 or great -er on the DN4 or great-er than 12 on the LANSS. All oth-er pain

was otherwise classiied as nociceptive.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to illustrate the study population demographic characteristics (gender and age) and the MS aspects (clinical form, Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) medication, onset of disease and relaps-es) as well as the characteristics of pain (localization, type of pain, types of headache and Lhermitte’s sign) and humor

status (depression and anxiety). he prevalence was esti

-mated by gender and total population. he Mann–Whitney

U test was used to compare continuous variables between

groups. he two-tailed Fisher’s exact test and Chi-Square was

used for categorical variable comparison. Logistic regression models were used to estimate the associations between pain and co-variables, such as gender, age (older or younger than 50 years old), EDSS, medication, clinical form, onset of dis-ease, relapses, depression and anxiety. In the bivariate

anal-ysis, the variables associated with pain to signiicance level

of 10% were included in the multivariate analysis to calcu-late adjusted estimates of Odds Ratio (OR). In multivariate

analysis, the diferences lower than 0.05 were accepted as signiicant. All statistical analyses were performed using pro

-gram support language R (he R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.r-project.org) and SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

All 100 patients met the inclusion criteria. here were

three questions that were not completed by all of the pa-tients: presence of Lhermitte’s phenomenon, 83 out of 100 re-sponded; another two individuals did not complete the BDI

(98/100) and 97/100 completed the BAI.

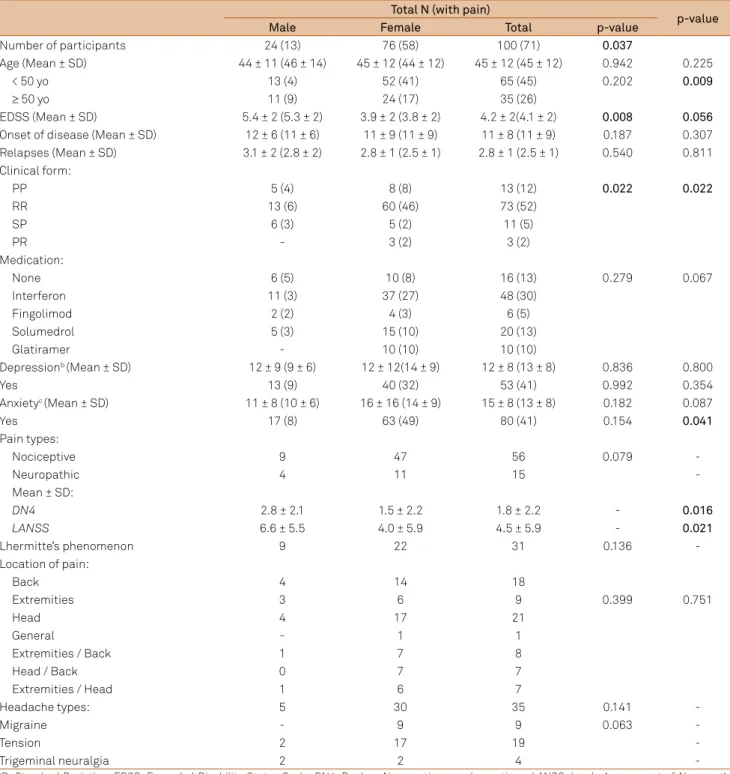

Descriptive statistics of prevalence rates are displayed in Table 1. Most notably, men showed statistically higher EDSS

than women (p = 0.008) with 5.4 and 3.9, respectively. he clinical forms of MS were statistically diferent amongst men (PP and SP) and women (RR) (p = 0.022). While women had a statistically higher prevalence of pain (p = 0.037), men had signiicantly higher scores on the DN4 (p = 0.016) and LANSS (p = 0.021), indicating greater severity in neuropathic pain

(Table 1). Neither depression nor anxiety was associated with the presence of pain.

he prevalence rates and gender distribution of the type of pain experienced by those patients with pain (n = 71) are

shown in Table 1. Within this group, men maintained their

signiicantly higher EDSS than women (p = 0.056) as in the

overall population. However, pain was found to be

indepen-dent of EDSS (Figure 1a and 1b). here was a signiicant dif -ference in the mean number of relapses and pain in females,

as seen in Figure 1 c and d (p = 0.001).

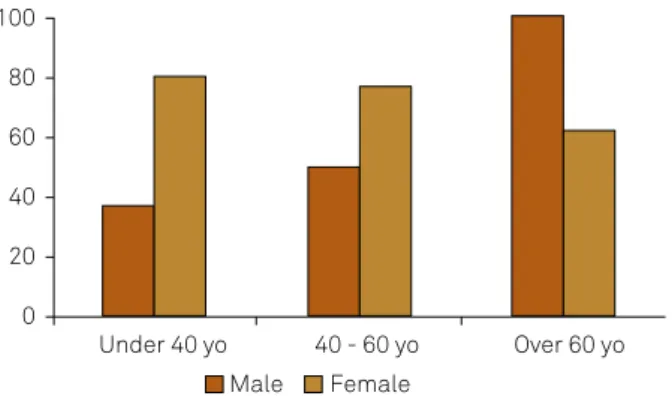

Upon comparing those patients under the age of 50 to those patients over the age of 50, we observed a

age of 50) having a higher prevalence of pain than men and older women, whereas older men (over the age of 50) had a higher prevalence of pain than women and younger men.

hese results are illustrated in Figure 2.

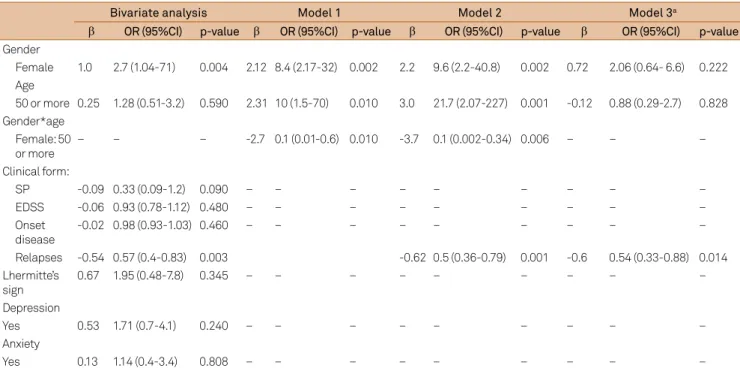

Logistical regression analysis found that females had a 2.7

greater chance of having pain than men (95%CI: 1.04-7) and older than 50 had only a minimal afect, 1.3 greater chance of having pain than not (95%CI: 1.07-3.2). Clinical forms showed no diference other than SP MS patients have a 67% lower risk of having pain than PP (95%CI: 0.09-1.2). However, the

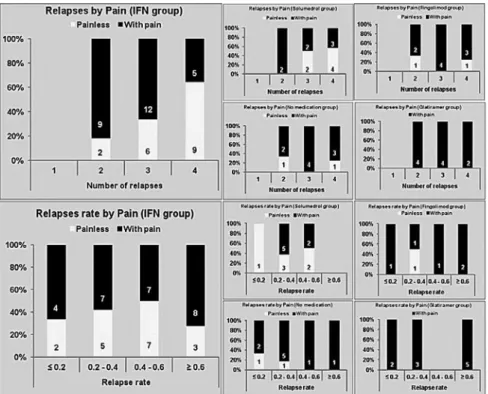

most indicative factor predicting the development of pain was a lower absolute number of relapses, instead of the an-nualized relapse rate. Excluding those with only one relapse

(13/16 having PP), each relapse after the second reduced in 46% the chance of experiencing pain [OR 0.54 (95%CI:0.33-0.88)]

adjusted for age and sex, but there was an interaction be-tween sex and age as demonstrated in Table 2 - Model 1 and 2; this was found to be independent of relapse rate as shown in Figure 3, which demonstrates the number of relapses by

pain (yes or no) and by medication/treatment type. Besides,

Table 1. Multiple sclerosis (MS) patients characteristics stratiied by gender.

Total N (with pain)

p-value

Male Female Total p-value

Number of participants 24 (13) 76 (58) 100 (71) 0.037

Age (Mean ± SD) 44 ± 11 (46 ± 14) 45 ± 12 (44 ± 12) 45 ± 12 (45 ± 12) 0.942 0.225

< 50 yo 13 (4) 52 (41) 65 (45) 0.202 0.009

≥ 50 yo 11 (9) 24 (17) 35 (26)

EDSS (Mean ± SD) 5.4 ± 2 (5.3 ± 2) 3.9 ± 2 (3.8 ± 2) 4.2 ± 2(4.1 ± 2) 0.008 0.056

Onset of disease (Mean ± SD) 12 ± 6 (11 ± 6) 11 ± 9 (11 ± 9) 11 ± 8 (11 ± 9) 0.187 0.307 Relapses (Mean ± SD) 3.1 ± 2 (2.8 ± 2) 2.8 ± 1 (2.5 ± 1) 2.8 ± 1 (2.5 ± 1) 0.540 0.811 Clinical form:

PP 5 (4) 8 (8) 13 (12) 0.022 0.022

RR 13 (6) 60 (46) 73 (52)

SP 6 (3) 5 (2) 11 (5)

PR - 3 (2) 3 (2)

Medication:

None 6 (5) 10 (8) 16 (13) 0.279 0.067

Interferon 11 (3) 37 (27) 48 (30)

Fingolimod 2 (2) 4 (3) 6 (5)

Solumedrol 5 (3) 15 (10) 20 (13)

Glatiramer - 10 (10) 10 (10)

Depressionb (Mean ± SD) 12 ± 9 (9 ± 6) 12 ± 12(14 ± 9) 12 ± 8 (13 ± 8) 0.836 0.800

Yes 13 (9) 40 (32) 53 (41) 0.992 0.354

Anxietyc (Mean ± SD) 11 ± 8 (10 ± 6) 16 ± 16 (14 ± 9) 15 ± 8 (13 ± 8) 0.182 0.087

Yes 17 (8) 63 (49) 80 (41) 0.154 0.041

Pain types:

Nociceptive 9 47 56 0.079

-Neuropathic 4 11 15

-Mean ± SD:

DN4 2.8 ± 2.1 1.5 ± 2.2 1.8 ± 2.2 - 0.016

LANSS 6.6 ± 5.5 4.0 ± 5.9 4.5 ± 5.9 - 0.021

Lhermitte’s phenomenon 9 22 31 0.136

-Location of pain:

Back 4 14 18

Extremities 3 6 9 0.399 0.751

Head 4 17 21

General - 1 1

Extremities / Back 1 7 8

Head / Back 0 7 7

Extremities / Head 1 6 7

Headache types: 5 30 35 0.141

-Migraine - 9 9 0.063

-Tension 2 17 19

-Trigeminal neuralgia 2 2 4

no statistical relationship was found between diferent medi

-cations. he complete results from the logistical analysis are

demonstrated in Table 2.

We both excluded and included those patients with one

relapse, and found that our results were statistically signii

-cant in both cases. here were 16 patients with one relapse,

13 of which were diagnosed with PP, one of which was diag-nosed with SP and two of which had RR, one of whom was 46 years old and was painless, another 24 years old who had pain. All those with one relapse were excluded, as we did not have the MRI data and, based upon only self-reported data, we felt that including the PP and the other three patients had a greater chance of skewing the data, as there is a chance of these three cases being either PP or a clinically isolated

syndrome (CIS). PP was eliminated so the data would more

clearly represent the phase 1 – relapsing phase and the im-pact on pain.

DISCUSSION

Our population displayed similar characteristics found in other studies, including the higher prevalence among women and prevalence of pain in general. Presence of pain was in-dependent of EDSS and had a negative association with re-lapses experienced. While the tendency was seen far greater in women, we believe the causes could be due to the greater

EDSS

8

6

4

2

0

Male Female

Female Male

Number of relapses

8

6

4

2

0

Male Female

EDSS

8

6

4

2

0

Number of relapses

8 D C

B A

6

4

2

0

Without pain With pain Without pain With pain

Female Male

Figure 1. (A) Difference of average Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) by gender (p-value = 0.008); (B) Difference of

average EDSS by gender in subjects with pain (p-value = 0.056) and without pain (p-value = 0.045). Difference of average EDSS by pain in subjects male (p-value = 0.814) and in female (p-value = 0.843); (C) Difference of average relapse number by gender (p-value = 0.048); (D) Difference of average relapse number by gender in subjects with pain (p-value = 0.120) and without pain (p-value = 0.780). Difference of average relapse number by pain in subjects’ male (p-value = 0.491) and in female (p-value = 0.003).

Male Female 100

80

60

40

20

0

Under 40 yo 40 - 60 yo Over 60 yo

This igure represents model 2 of logistic regression model supporting the age-related benchmarks and change of the disease and trends.

Figure 2. Differences in prevalence of “presence of pain” over

number of women in our study or a gender or srelated

ex-planation. hough it should be noted that men showed the same trends found among women when stratiied in a simi -lar representation as showed in Figure 4, we grouped togeth-er the sexes as the sample size is limited. Our exclusion of PP and the three cases with one relapse was to attempt to eliminate any element of confounding that could be caused by patients that may be misdiagnosed with RR-MS rather

than a CIS or PP. While the statistical signiicance in our ind -ing was present whether we included or excluded PP, we felt

that the inclusion of PP may too strongly inluence the results

and as such it remained excluded from our analysis. Our re-sults were unexpected, yet not completely out of the realm of reason and had strong support in recent MS literature. Nevertheless, we have done our due diligence in our statisti-cal analysis, data collection, recording and interpretation to

state with certainty our indings and have tried to account

for any confound or aspect of the disease that may have been overlooked and that would provide an alternative hypothesis. Of course, there are always factors that cannot be controlled and should be considered when relying upon self-reported data from patients, which answers may be exaggerated and present biases such as social desirability or suggestion. We have no evidence of such a bias in our study and attempted to use the DN4, LANSS, BAI and BDI to assist in this error.

he incidence of RR-MS has been close to 2-3 times

greater for women than for men, whereas the PP is a 1:1 ra-tio. While incidence of RR has been predominantly associ-ated with women, severity of the disease has been linked to men. As such, the role of this gender bias has typically

been considered in congruous with relapses occurring more in women than in men, though men being more severe. However, with recent studies on disability and disease pro-gression invalidating the long held belief that relapses were

indicative or related to disease/disability progression or se

-verity, questions as to the role of relapses in MS or this irst

relapsing phase within the natural progression of the disease have been raised.

Our results propose that relapses are related to

dimin-ished prevalence of pain, suggesting that the irst relapsing

phase of MS may be protective against pain in the underlying second phase which appears to be more age-related3,11,12,13,14.

his would imply that the increase in relapses that women

undergo in their premenstrual cycle15, postpartum period16

and assisted reproductive technology (ART) with gonadotro-pin releasing hormone agonists17 are all indicative of the

fe-male sex related hormones/genes causing increased relapses

and their surrogate lesions as a possible “protective” function by reducing pain-related brain activation in anticipation of the underlying “dormant” disease (second phase) when more

debilitating progression will occur. his would also clarify

the reason that more severe disability is found in men ear-ly on and greater prevalence of pain in the second phase of the disease, as it is exposure to female steroid hormones that increases the susceptibility for relapses12. Unfortunately, our

inding remain speculative as we have found few studies on pain in multiple sclerosis and none that have stratiied based

upon sex.

While MRI analysis and lesion load is beyond the scope of our study, MRI T2 or gadolinium enhancing lesions have

Table 2. Logistical regression analyses.

Bivariate analysis Model 1 Model 2 Model 3a

β OR (95%CI) p-value β OR (95%CI) p-value β OR (95%CI) p-value β OR (95%CI) p-value

Gender

Female 1.0 2.7 (1.04-71) 0.004 2.12 8.4 (2.17-32) 0.002 2.2 9.6 (2.2-40.8) 0.002 0.72 2.06 (0.64- 6.6) 0.222 Age

50 or more 0.25 1.28 (0.51-3.2) 0.590 2.31 10 (1.5-70) 0.010 3.0 21.7 (2.07-227) 0.001 -0.12 0.88 (0.29-2.7) 0.828 Gender*age

Female: 50 or more

– – – -2.7 0.1 (0.01-0.6) 0.010 -3.7 0.1 (0.002-0.34) 0.006 – – –

Clinical form:

SP -0.09 0.33 (0.09-1.2) 0.090 – – – – – – – – –

EDSS -0.06 0.93 (0.78-1.12) 0.480 – – – – – – – – –

Onset disease

-0.02 0.98 (0.93-1.03) 0.460 – – – – – – – – –

Relapses -0.54 0.57 (0.4-0.83) 0.003 -0.62 0.5 (0.36-0.79) 0.001 -0.6 0.54 (0.33-0.88) 0.014 Lhermitte’s

sign

0.67 1.95 (0.48-7.8) 0.345 – – – – – – – – –

Depression

Yes 0.53 1.71 (0.7-4.1) 0.240 – – – – – – – – –

Anxiety

Yes 0.13 1.14 (0.4-3.4) 0.808 – – – – – – – – –

Model 1: included the following variables: gender, age and interaction between gender and age; Model 2: included the following variables: gender, age, relapses and interaction between gender and age; Model 3: included the following variables: gender, age and relapses; a excluded the clinical form “Primary progressive”.

long been established as the surrogates of focal inlamma -tion18.Even though pain has been associated with various

pain syndromes in MS (i.e. extremity pain, back pain, etc.), there has not been an association found between pain and the site of demyelination19 though it has been associated

with depression, spinal cord involvement at the onset and the presence of spinal cord lesions3. he damage to the pain

pathways has been theorized to possibly involve glia and cy-tokines20, which has been linked to the possible mechanism

of central pain21. However, no signiicant pain relief has been

found with any of the disease modifying medications that target the immune system. Furthermore, our results are sup-ported by recent work in neuroimaging, which suggests that intrinsic brain connectivity is associated with chronic pain intensity22, implying that lesions or demyelinating

neuro-degeneration may reduce or eliminate pain sensation. his

concept directly contradicts the formerly held belief of the role of relapses and supports other work in Neurology which proposes that pain is a multimodal evaluative or distributed process in the brain22.Recent studies investigating brain

le-sions support the hypothesis that they may serve as a func-tion of the body to reduce pain-related cortical activity23, or

the sensory-discriminative processing of pain23 meanwhile

maintaining intact tactile thresholds23 thus serving as a

pro-tective measure against pain or aid in its tolerability. We postulate that with the increase of lesion load, associ-ated with a higher number of relapses, it is possible that the interpretation of painful stimuli by the brain is impaired or that the arrival of those stimuli to somatosensorial pathways

is decreased. One study24 found that, in a long-term basis,

accumulation of relapses and their consequences are less evident in patients with MS. Furthermore, with the advent

of more powerful MRI scans, the conirmation of involve -ment of the gray matter became more sensitive. Harrison et al25 conducted a study with 34 patients and demonstrated

through 7-Tesla MRI scan that thalamic lesions were pres-ent in 24 patipres-ents. It is known that such lesions are associ-ated with a higher EDSS score, cortical lesions and progres-sive forms. Regarding the thalamus as a major relay of pain, its involvement in patients with MS diminish the arrival of nociceptive inputs to cortical regions.

Studies of pain in MS patients have attempted to link the location of lesions to related pain and have found

dif-iculty in defending this theory. For example, ongoing ex -tremity pain is more common in patients with primary pro-gressive or the propro-gressive-relapsing (PR) types of MS, and lowest in the RR type26. MRI studies usually show plaques

in the cervical and thoracic spinal cord, however the

bilat-eral and relatively distal distribution is diicult to explain as

there is ample evidence that excludes peripheral nerve in-volvement5. MS-related trigeminal neuralgia (TN) has long

been attributed to a demyelinating plaque in the pons, as seen in postmortem specimens27, however this contrasts

with the frequent neuroimaging inding of a neurovascular

contact with the trigeminal root in patients with TN and MS and the existence of some patients with MS who have TN as the sole clinical manifestation and the microvascular decompression outcome of neurosurgical studies results in A representation of our population by those with and without pain stratiied by number of relapses and by medication use. There was no difference amongst the use of medication as the N was very small in most cases. As the irst line treatment in our clinic is Interferon, we have highlighted to represent better the trend that our results demonstrate. The N is represented at the base of each group.

considerable pain relief27. Lhermitte’s phenomenon, which

is thought to come from a demyelinating plaque in the dor-sal columns at the cervical level, is for many patients a tran-sient symptom, manifesting for some weeks then resolving spontaneously26. Painful tonic spasms are more MS-speciic.

hey are involuntary muscle contractions that last less than

2 minutes sometimes several times per day and usually

continue for weeks or months and then disappear. hey are

more common in PP and SP forms and are positively corre-lated with age, disease duration, and disability26, although

never found to be linked to relapses and appear to be linked to the second phase of MS.

Inasmuch as our study may provide a drastic shift in the role of relapses, it supports the recent two distinct phase model of MS11, 24, 28, gender12 and age related29

find-ings. However, it remains difficult to interpret drug tri-als, as relapses have typically been an end-point and as such creates a mind-boggling task of applying these trial results to the mechanism of action of these drugs. Even so, our results concur with several well-designed trials in SP multiple sclerosis30, which showed an unrelated impact

of treatments focusing on focal inflammation ( frequency of relapses and MRI activity) on delaying disability pro-gression. This implies that therapeutics focusing on these end-points rather than disability progression are actually working against the immune system to preserve the indi-vidual from later MS related pain developed in the second phase. By no means are we able to state that relapses hold a beneficial function, however our results indicate that

further studies need to be done to investigate the relation-ship between a possibly protective role of relapses for later developed pain. As well, while we stratified our results by medication use, this is not to imply that any relationship was found in use of medication. The fact remains that our population size is extremely limited and the use of medi-cation, pain and relapse is confounded by the specific phy-sician choice of therapeutic treatment. Treatment choic-es have a variety of considerations that are unable to be stratified or listed, as they are patient specific. We stress that our results cannot be used to draw conclusion about drug treatments used and that larger longitudinal studies would be able to offer more insight. Our findings do sup-port that the progressive phase is the core phenotype of MS, and its probability, slope, and latency should be the targets for MS treatment and investigations.

he most obvious limitation of our study is the size of our sample. While we still reached statistical signiicance, our indings should be veriied in larger longitudinal stud

-ies and stratiied per sex to verify if the same patterns exist.

On this same note, as our sample was a clinic based study, it did not have an equal number of men and women, and

re-lects the gender bias in incidence. We believe the intensity

and location of pain, though done only general in our study should be investigated in relation to the presence of MRI T2 or gadolinium enhancing lesions. Moreover, we did not per-form a regression analysis adjusted for time of disease, what we believe to be a critical limitation of study, once the greater the disease duration, the higher the relapses occurrence. Our Phase 1: Relapsing Phase 2: Progressing Disability

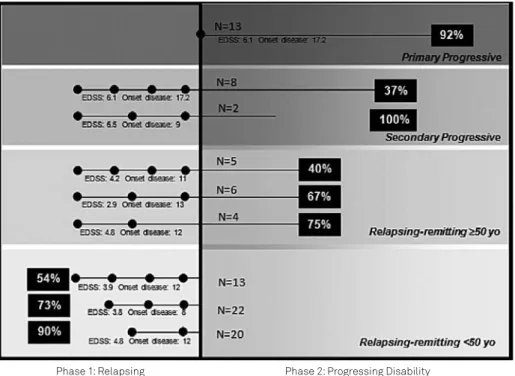

The percentage of multiple sclerosis (MS) patients with pain is represented in the black boxes per phase. This model presents that relapsing-remitting patients over the age of 50 represent individuals who are in the second stage based upon age (as is separated in the lower two boxes). The points on the line represent corresponds to number of relapses experience by these patients, with the sub group Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and average onset of disease listed below. The N of each subgroup is listed. When stratiied by gender, we found similar trends between the representations but as our population size is limited, both genders are represented in this igure.

next step will consist of analyzing the annualized relapse rate and its relationship to pain frequency.

In our sample, 64 patients were on immunomodulatory therapy. Among those, 48 were in regular use of interferons.

Taking into account the diiculty of MS patients to adhere

to treatment, we included in our study only patients with

References

1. Solaro C, Brichetto G, Amato MP, Cocco E, Colombo B, D’Aleo G et al. The prevalence of pain in multiple sclerosis: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Neurology. 2004;63(5):919-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/01.WNL.0000137047.85868.D6

2. Hadjimichael O, Kerns RD, Rizzo MA, Cutter G, Vollmer T. Persistent pain and uncomfortable sensations in persons with multiple sclerosis. Pain. 2007;127(1-2):35-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.015

3. Grau-López L, Sierra S, Martínez-Cáceres E, Ramo-Tello C. Analysis of the pain in multiple sclerosis patients. Neurologia. 2011;26(4):208-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nrl.2010.07.014

4. Kalia LV, O’Connor PW. Severity of chronic pain and its relationship to quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(3):322-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1352458505ms1168oa

5. Osterberg A, Boivie J, Thuomas KA. Central pain in multiple sclerosis: prevalence and clinical characteristics. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(5):531-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.005

6. Truini A, Barbanti P, Pozzilli C, Cruccu G. A mechanism-based classiication of pain in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2013;260(2):351-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00415-012-6579-2

7. Santos JG, Brito JO, de Andrade DC, Kaziyama VM, Ferreira KA, Souza I et al. Translation to Portuguese and validation of the Douleur Neuropathique 4 questionnaire. J Pain. 2010;11(5):484-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2009.09.014

8. Schestatsky P, Félix-Torres V, Chaves ML, Câmara-Ehlers B, Mucenic T, Caumo W et al. Brazilian Portuguese validation of the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs for patients with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2011; 12(10):1544-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01221.x

9. Cunha J. Manual da versão em português das escalas Beck. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo; 2001.

10. Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, Clanet M, Cohen JA, Filippi M et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69(2):292-302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ana.22366

11. Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A, Rice GP, Muraro PA, Daumer M et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain. 2010;133(7):1914-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq118

12. Voskuhl RR. Gender issues and multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2002;2(3):277-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11910-002-0087-1

13. Kremenchutzky M, Rice GP, Baskerville J, Wingerchuk DM, Ebers GC. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 9: observations on the progressive phase of the disease. Brain. 2006;129(3):584-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh721

14. Stankoff B, Mrejen S, Tourbah A, Fontaine B, Lyon-Caen O, Lubetzki C et al. Age at onset determines the occurrence of the progressive phase of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2007;68(10):779-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000256732.36565.4a

15. Zorgdrager A, De Keyser J. The premenstrual period and exacerbations in multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol 2002;48(4):204-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000066166

16. Paavilainen T, Kurki T, Parkkola R, Färkkilä M, Salonen O, Dastidar P et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain used to detect early post-partum activation of multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(11):1216-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01927.x

17. Michel L, Foucher Y, Vukusic S, Confavreux C, Sèze J, Brassat D et al. Increased risk of multiple sclerosis relapse after in vitro fertilisation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(8):796-802. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2012-302235

18. Frischer JM, Bramow S, Dal-Bianco A, Lucchinetti CF, Rauschka H, Schmidbauer M et al. The relation between inlammation and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis brains. Brain. 2009;132( 5):1175-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awp070

19. Borsook D. Neurological diseases and pain. Brain. 2012;135(2):320-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr271

20. Merson TD, Binder MD, Kilpatrick TJ. Role of cytokines as mediators and regulators of microglial activity in inlammatory demyelination of the CNS. Neuromolecular Med. 2010;12(2):99-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12017-010-8112-z

21. Graeber MB. Changing face of microglia. Science.

2010;330(6005):783-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1190929

22. Napadow V, LaCount L, Park K, As-Sanie S, Clauw DJ, Harris RE. Intrinsic brain connectivity in ibromyalgia is associated with chronic pain intensity. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(8):2545-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.27497

23. Starr CJ, Sawaki L, Wittenberg GF, Burdette JH, Oshiro Y, Quevedo AS et al. The contribution of the putamen to sensory aspects of pain: insights from structural connectivity and brain lesions. Brain. 2011;134(7):1987-2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr117

24. Tremlett H, Yousei M, Devonshire V, Rieckmann P, Zhao Y. Impact of multiple sclerosis relapses on progression diminishes with time. Neurology. 2009;73(20):1616-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c1e44f

25. Harrison DM, Oh J, Roy S, Wood ET, Whetstone A, Seigo MA et al. Thalamic lesions in multiple sclerosis by 7T MRI: clinical implications and relationship to cortical pathology. Mult Scler. 2015 [Forthcoming].

26. Nurmikko TJ, Gupta S, Maclver K. Multiple sclerosis-related central pain disorders. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14(3):189-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11916-010-0108-8

27. Athanasiou TC, Patel NK, Renowden SA, Coakham HB. Some patients with multiple sclerosis have neurovascular compression causing their trigeminal neuralgia and can be treated effectively with MVD: report of ive cases. Br J Neurosurg. 2005;19(6):463-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02688690500495067

28. Leray E, Yaouanq J, Le Page E, Coustans M, Laplaud D, Oger J et al. Evidence for a two-stage disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2010;133(7):1900-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq076

29. Confavreux C, Vukusic S. Age at disability milestones in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2006;129(3):595-605. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh714

30. Rice GP, Filippi M, Comi G. Cladribine and progressive MS: clinical and MRI outcomes of a multicenter controlled trial. Neurology. 2000;54(5):1145-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.54.5.1145 medication possession rate above 80%, thus avoiding a pos-sible selection bias.

In conclusion, regardless the number of limitations of