131

10

AFFECTIVE MAPS: VALIDATING A DIALOGUE BETWEEN

QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE METHODS

Resumir numero de autores para que quepan en la cabecera

Cruz Bomfim, Z.A.; Lemos Nobre B. H.; Moraes Ferreira, T. L.; Albuquerque de Araújo, L. M.; Souza Feitosa, M. Z.; Silva Martins, A. K.; Fonseca de Alencar, H.; Fernandes Farias, N.

University / Affiliation Federal University of Ceará, Brazil

AFFECTIVE MAPS: VALIDATING A DIALOGUE BETWEEN

QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE METHODS1

Zulmira Aurea Cruz Bomfim, Bruno Halyson Lemos Nobre; Thais Leite Moraes Ferreira; Lívio Marcio Albuquerque de Araujo; Maria Zelfa de Souza Feitosa; Ana Kristia da Silva Martins; Helenira Fonseca de Alencar; Nazka Fernandes Farias

Federal University of Ceará, Brazil

Abstract

Affective Maps is an environmental and social category related to the concept of place identity, cognitive maps, affectivity, and it is a representation of space related to any environment as an emotional territory. It intends to be a tool that shows affectivity and indicates the inhabitant’s Esteem for the place. Affective Maps is yielded by a questionnaire, named Affective Maps Generator Questionnaire, which is constituted by a quantitative (including a response scale and a socio-economic profile questionnaire) and qualitative (including a drawing of the environment re-searched and a inquiry) method of data collection and analysis. This study aims to present and discuss the results of a study, bringing the methodological process and explaining the dialogue between different methods (quantitative and qualitative) of data collection and analysis to inquiries about the affective-symbolic relation-ships between people and their environments. Therefore, the questionnaire was ap-plied with reference to the neighborhood of residence of 293 participants from high schools in Fortaleza, CE, Brazil. First, analysis of the validity and accuracy for the response scale of the questionnaire were made. Then the qualitative and quantita-tive parts of the questionnaire were analyzed. It was observed that the majority of the sample presented contrasting affects in relation to neighborhood of residence in which coexisted positive and negative representations about this environment. The dialogue between qualitative and quantitative analysis yielded these findings, when a way of reference and counter-reference between them was created.

Keywords: Affective map, qualitative method, dialogue, neighborhood.

Introduction

This text theoretically lies in dialogue between Environmental Psychology and Social Psychology, which has fostered the conduction of studies on the relationship between people and their physical and social environments supported by theoretical categories in a historical and cultural perspective such as Affectivity (Sawaia, 1995; Vigotski, 1998), Place Attachment (Proshansky et al 1978, 1983) and Esteem for the Place (Bomfim, 2003a, 2010), among others. These categories, in general, consider the

1 This article was produced from the results of a survey entitled “Esteem for the Place and Affective Protection indicators of young students in public schools in Fortaleza: contributions of Environmental Psychology to the understanding of socio-environmental vulnerability (2nd step)”, carried out in the

years 2012 and 2013 in the city of Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil.

historical, social and cultural character of the production of affection that emerges in the person-environment relationship.

This relationship is understood in its cognitive, affective and symbolic dimensions, in which the physical space is converted to the mean space (Corraliza, 1998), once the subject turns impersonal spaces previously provided into a place of value (Tuan, 1983) with which it is involved, maintains and cares (Bomfim, 2003b). On this interaction, individually and socially, meaning is constructed for places in what consists of the symbolism of space (Pol & Valera, 1999), giving the subject a sense of group identity and transforming spaces into a social category, whereby its inhabitants, or subjects who make use of it, will be recognized by others and by themselves

Consonant with this perspective, Lynch (2010) states that each subject forms his own picture of the environment; however, there is a certain consensus among mem-bers of the same group. This symbolic construction, both individual and collective, composes - beyond the identity of the group - the subjectivity of its members, and is directly related to the welfare of the subjects (Pol & Valera, 1999) since these require a stable reference in space, which provide them with guidance and preservation of identity before themselves and others (Pol, 1996).

According to Pol (1996), spaces, beyond their functional sense, are a summary of public and private experiences of the subject and the appropriation of these spaces allows people projection in time and ensures the stability of identity. In the process of appropriation of space, a man leaves his mark on the environment, feeling comfortable by leaving something of himself at the same time as he establishes identity character-istics (Tuan, 1983). In this regard, in the appropriation of space there is a dialectic and cyclical relationship between the action-transformation which marks the subject with the places, thus constituting himself as an active process, which evokes the feeling of belonging to the place, which is effective through its possession, whether through legal ownership or use, identification and protection of these places (Pol & Valera, 1999)

We may say then that subjects establish an emotional bond in relation to places, which can be positive or negative, pleasant or unpleasant (Giuliani, 2004).This bond may arise in the subject’s desire to be always close to this place, which is configured in attachment to the place, resulting from a positive assessment of the quality of the place to meet the needs of the subject; meaning that the place forms part of the identity of the person, or the duration of residence and permanence in the place. From this emotional attachment of individuals to specific places or spatial configurations, Proshansky et al (1978, 1983) explores the concept of Place Identity Studied by environmental psy-chology, relative to the idea that we are included in the places we have been to and the places we are.

places in which they can satisfy their lifelong biological, psychological, social and cultural needs. It is worth noting that this definition is not tight - it acknowledges the dynamics with changes in the physical environment, varying the ability to meet the needs and desires of the subjects, which derive good or bad experiences, affecting the identity of persons (Proshansky et al. 1983). Thus, the identity of place is complex and changes, differentiating and shaping based on human interactions with places and with others (Bridge et al., 2009). Thus, the concept of place identity also involves re-lational dimension with others, considering that space is also a collective construction (Proshansky et al., 1983). Likewise, for the authors, the material and structural proper-ties of place identity vary according to gender, age, social class and personality, among others, suffering transformations across the life cycle. It derives, as shown by Bridge et al (2009, p. 350), while that gives meaning and direction to places, the subject “[...] In addition to building semiotic places, recognizes himself now as individuality and otherness that is ‘reified’, sometimes as a denial of self as an object of self and self-affirmation in the process.”

Accordingly, Bomfim (2003a, 2010) brought the Esteem for the Place category to refer to the cognitive, affective and symbolic representations constructed in the routine of subjects in their social and physical environments that enhance or not the possibili-ties of action and implication of these subjects in their environments.

Thus, our study (Esteem for the Place and Affective Protection indicators of young students in public schools in Fortaleza: contributions of Environmental Psychology to the understanding of socio-environmental vulnerability - 2nd step) researched the

rela-tionship of esteem with the place in young high school students from public schools in the city of Fortaleza, Brazil, using qualitative and quantitative strategies for collecting and analyzing data.

Overall, this text aims to present and discuss the results of this study, bringing a kind of methodological process and explaining a dialogue between different methods (quantitative and qualitative) of data collection and analysis to inquiries about the affective-symbolic relationships between people and their environments..

The Esteem for the Place and the relationship between the person and the environment

the structural relationship of this object with the observer and other objects, and the practical or emotional meaning that this object has for the observer (Lynch, 2010).

Assuming that the city presents readability, which refers to the clarity with which the city can be read, decoded by its inhabitants, the author argues that the symbolic construction of the image of the city allows the subject to form a mental map, although fragmented, which allows you to orient yourself in the city. A legible city means, there-fore, that the subject can easily identify its elements and group them into global struc-tures. According to Lynch (2010), the formation of a clear image of the environment enables growth of the subjects at the same time as they take advantage of the orienta-tion that it produces.

Thus, Lynch (2010) argues that the urban environment, even broad and large, can take on a perceivable form as the subjects draw their mental maps of the city. In ad-dition to an image of the physical structure, as the author points out, in drawing the subjects express elements of their symbolic world, with regard to their interaction with the environment, i.e. the meanings that they structure for the city, the interpreta-tion that they make and their individual and collective way of representing it become public. Therefore, in researches conducted by the author, it was found that not always drawn maps correspond to the physical reality of the environment, but to widespread generalized impressions that this reality generated in subjects. In this procedure, the construction of the drawing starts from the acquisition of information about places and attributes of urban space, which are encoded, stored, recalled and decoded by the subjects through a graphical expression. The cognitive maps studied by Lynch show that the guidance and knowledge of the city are important for the feeling of security, as well as enabling the organization of space, social and cognitive experience (Lynch, 2010).

As noted by Bomfim (2003a), cognitive maps centered on a “rational” knowledge of the city, not including the affections contained in the graphic expression of the map and the symbolic constitution of space itself, for the subjects. Thus, intending an appre-hension of affection, the author proposes the Affective Maps Generator Questionnaire methodology, the result of his doctoral thesis, as a form of access to the affection of the subject in relation to the environment, although there may be intangible and outer expression to other traditional methods. Therefore, we define affective maps as an environmental and social category related to the concept of place identity, cognitive maps, affectivity, and it is a representation of space related to any environment as an emotional territory. It intends to be a tool that shows affectivity and indicates the in-habitant’s involvement with the city or an environment (Bomfim, 2003a).

are neither good nor bad, but ambiguous, which leads us to multidimensional spaces, which evokes the same ambiguity of emotions related to them (Sawaia, 1995).

Affection is understood here as a category of action-mediation and transforma-tion of the human psyche, which may be positive or negative (Bomfim, 2003a), the emotional color that fills human experience with meanings and can express itself in the form of feelings - lasting and moderate with respect to the feeling of pleasure or displeasure - and emotions - intense, brief and focused on phenomena that disrupt the normal flow of conduct (Sawaia, 2011). Thus, affection can increase or decrease the power of action in the body, leading it into action, increasing its strength to exist, or passivity, this depressing force (Spinosa, 2005), also impacting the way the subject demarcates his territory (Pol, 1996) and binds him to places (Giuliani, 2004).

For Bomfim (1999) emotions and feelings mediate the identity of the subjects, the interaction with space and others, as is the uniqueness of everyday history that it constructs, and moreover, is able to reveal how the subjects know and act on the city (Bomfim, 2003a). Sawaia (2011) understands the power of action as the regulative principle that allows the individual to act on his reality, towards his emancipation. Thus, Bomfim (1999) argues that affectivity gives an understanding of the conflict be-tween the micro and macro social, reestablishing the dialectical relationship bebe-tween them, breaking the dichotomy between internal and external, subjective and objective, thus decoupling affection, activity and consciousness about the environment perpetu-ates the alienation of subject and attenuperpetu-ates the existing relations of domination in society. On the other hand, according to Sawaia (2011), the power of suffering, the passion generated by sadness, driven by bondage and passivity, since it becomes sub-ject to another at will. We would state, based on these considerations, that spaces and places can be emancipatory or maintainers of bondage and the suffering of individu-als, and we propose affective maps as a way of consistent research about how subjects interact with the spaces, such as affecting with them, because we agree with Vygotsky (1998) that affection can only be understood within the dynamics of human life as a whole, in addition to not always being the same, but differing according to the level of development of the subject. Therefore, the Esteem for the Place (Bomfim, 2010; 2013), it is worth mentioning, concerns affective evaluations, with a positive and/or negative background, which a person feels from their environment, and it is, in turn, expressed by feelings and emotions through projected images, representations and vi-sions of a world.

The symbolism of space, built by the cultural-historical background of the subject, exerts a strong influence on attachment relationships, belonging and identifying with the place (Pol & Valera, 1999).

Thus, the environment is not then understood only as a set of material properties, concrete and tangible, but rather as an emotional territory where these things are vis-cerally connected by meanings, so it is liable to be appropriated and transformed by the subjects that compose and occupy it.

The Esteem for the Place refers to appreciation, valuation and attachment with re-gard to the place. It relies on the evaluation of the quality of housing and environmen-tal use, i.e., security, cleanliness, organization, sophistication, aesthetic, environmenenvironmen-tal preservation, legibility, signage, accessibility, etc; in the quality of social bonds of friendship and good relations, on the social image of the place in society, and mainly at the level of the individual appropriation of space that people esteem. (Bomfim et al, 2013, p. 322).

Affective Maps and the the Affective Maps Generator Questionnaire (IGMA2)

Methodologically the Esteem for the Place is diagnosed using the Affective Maps

Generator Questionnaire (IGMA), prepared by Bomfim (2003a, 2010), since this

al-lows a graphical representation, a metaphorical and artistic relationship between the individual and a particular environment.

We define the affective maps as an environmental and social category related to the concept of place identity, cognitive maps, affectivity, and it is a representation of space related to any environment as an emotional territory. It intends to be a tool that shows affectivity and indicates the inhabitant’s involvement with the city or an environment (Bomfim, 2003a).

Affective maps can be drawn by the graphic, artistic and metaphoric expression from images and representations that people have from a place. It can be taken as a guiding principle of the implementation of actions intended to seek the involvement of the population in urban and environmental issues.

The IGMA constitutes a quantitative and qualitative method of data collection and analysis, using interpretive synthesis compared with the scores from scale responses, evaluating the affective and imagistic production on environments from the relation-ship established between these and their occupants. Through people’s affection in rela-tion to the environment, they articulate feelings, evaluarela-tions and identificarela-tion of the person in respect to a particular place. This questionnaire will generate the affective maps.

What we call the qualitative part of IGMA comprises a stimulation to construct a representational drawing of a particular environment (community, neighborhood, city, etc) followed by an inquiry about the feelings, meanings and qualities related to the environment and mediated by that drawing.

The psychometric or quantitative part, in turn, constitutes a 5-point Likert type scale with assertions about the environment to be answered according to the degree of agreement with these assertions, plus a Socio-Economic Profile Questionnaire.

In summary, the complete contents of IGMA are:

• Drawing of the Environment Researched • Inquiry3

• Scale (named Esteem for the Place Scale, EEL4) • Socio-Economic Profile Questionnaire

After the data was collected from the people interviewed, the researcher constructs a framework like this and analyzes it by creating a subtext and sense of meaning for each one of the answers. This is the process of affective map construction. We call this process a “construction of meaning moved by affections” (Bomfim, 2003). Thus, the qualitative part of the questionnaire of Affective Maps is a method that seeks to reveal the affections considering the subtext and the sense of meaning (Vygotsky, 1995) pre-sented in the responses of the individuals.

Bomfim (2003a, 2010) considers, then, that there are four possible representations of the environment that are more frequent. They are Belongingness, Agreeableness, Destruction and Insecurity. These categories arising from IGMA data analyze the clas-sification of the type of place of esteem in subjects.

The Agreeableness image reveals feelings and qualifications perceived as pleasant by residents of neighborhoods, cities or communities. The Belongingness is an image in which the resident feels and describes his neighborhood or city, considering his social ties of friendship or kinship, besides presenting a deeper identification with the place. Insecurity is based on the feelings of fear, instability and inconstancy, which are opposite to Belongingness and derive directly from urban violence. The image of Destruction is the reverse of Agreeableness. Residents feel uncomfortable with the presence of destroyed, degraded and abandoned spaces.

These affective indicators from the scale compose Esteem for the Place (Bomfim, 2003), which can be more potentiating or non-potentiating. The inhabitants involved who have a potentiating Esteem for the place have higher scores on the categories of Agreeableness and Belongingness, and the ones who score less on potentiating Esteem for the place have higher scores on Insecurity and Destruction.

This is because the signs are that the feelings of fear, insecurity, frustration and anger (typical in the pictures of Insecurity and Destruction) decrease the potential of action of the individual in the city and his implication therein. Contrary to this, the feelings of belongingness and agreeableness, for example, promote a caring relation-ship and participation with the city and the inhabitant’s increasing potential of action, which correlates with the statement by Pol and Valera (1983) that when there is a

3 The survey contains questions about the meaning of the drawing, about the feelings, the word synthe-sis of the feelings, what they think about the environment researched, the creating of a metaphor of the city, and about the everyday paths and participation in association.

strong place identity, i.e. a strong identification with the city, there is also a higher level of overall citizen satisfaction. However, it is understood that both forms of es-teem coexist, especially in context of complexity of large cities, producing a transverse category of analysis which is the contrast, or an Esteem for the location that goes from potentiating to non-potentiating.

Method

Building of Esteem for the Place Scale (EEL)

Considering the lack of criteria of validity and accuracy of this scale in IGMA, the need arose to include the validation of the scale within the methodological approach of the study. To this end, a survey of studies in environmental psychology that used IGMA to raise the content of future items of the new scale was performed. In other words, EEL items were constructed from the contents collected in studies using IGMA (usually containing, besides drawings and inquiries, a scale created for each one of the studies, no criteria to establish its validity and accuracy).

Thus, after the lifting of that content, even created in preliminary scale items and adjusted, they take into account the evaluation criteria of items exposed by Pasquali (2010). The construction of the items was oriented according to the expected scale fac-tors, Agreeableness, Belongingness, Destruction and Insecurity.

The items were then reviewed for their semantic readability through a Semantic Analysis and finally subjected to an Analysis of Judges (Pasquali, 2010). The latter consists of the presentation of the items and the theoretical definitions of the factors that make up the scale to experts (judges) in the area, without, however, relating them. The duty of the judge is to link the factors and their respective items without prior knowledge, in order to demonstrate consistency of the scale theory (Pasquali, 2010). After that, we arrived at a pilot scale that was inserted into the IGMA and subsequently subjected to statistical analysis of validity and accuracy.

Application Procedures and Participants

Table 1 shows the sample characteristics of participants with frequencies and per-centages.

Table 1. Sample characteristics (N=293)

Variable n %

Sex Male 118 43,5

Female 153 56,5

Total 271 100,0

Age group (years)* 14-15 22 7,6

16-17 182 62,8

18-19 75 25,9

20 or more 11 3,8

Total 290 100,0

Familiar income

(brazilian minimum wages5)

0-1 86 37,9

1-2 67 29,5

2-3 47 20,7

3-4 10 4,4

4 or more 17 7,5

Total 227 100,0

* Mean age 17, 19 years (SD = 2.20).5

Data Analysis

First, considering the validation process of the EEL, we proceeded with the ex-ploratory factor analysis of the sample. Furthermore, the data analysis methods carried out were descriptive analyses, as of standard deviation and frequencies; parametric analyses, like Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, Principal Component Analysis and Cronbach’s alpha, the latter to assess the internal consistency of the scale.

Results

Validity and accuracy of the Esteem for the Place scale

The factorability of the data matrix was confirmed by a KMO = 0.88 and a sta-tistically significant chi-square test extracted from the Bartlett Sphericity, χ2 (1540) =

5526.53, p <0.001. These findings indicate that the data matrix was suitable for the factor analysis (Tabachnick & Fidel 2001). Hence a Principal Component Analysis showed that it was possible to verify the prevalence of two main factors with eigenval-ues exceeding 1, which responds to the Kaiser criterion, and together explains 36.75% of total variance. However, in order to better evaluate how many components should be extracted, it was decided to take into account the graphical distribution of

ues (used as a tool for the Cattell criterion). According to this criterion, it was possible to consider also two components, as seen in Figure 1. Thus, the two-factor structure of this measure seems consistent.

Figure 1. Graphic distribution of eigenvalues of the components.

Figure 1. Graphic distribution of eigenvalues of the components

Then, this factor structure obtained was tested using a rotating type of oblimin (when there is the hypothesis of correlation between the components) for extracting factors. Out of 56 items on the pilot version, 15 items showed no satisfactory saturations in any of the two factors and were therefore excluded from the scale in its final version. Was arbitrated loadings higher than |0.40| as cutoff factor values, since values above |0.30| are already considered, as a rule, as satisfactory. It is noteworthy that two items originally belonging to the dimensions of Factor I (Items 5 and 24) obtained saturations in Factor II, but with negative charges, i.e. their contents inversely measure the construct of Factor II.

The first factor had an eigenvalue of 16.05 and explained 28.6% of the total vari-ance, and an internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.84, while the second factor had an eigenvalue of 4.53 and explained 8.1% of the total variance, while its internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.88. The factors relate to each other negatively with a Correlation Coefficient (Pearson’s R) of -0.45, statistically significant at the 0.01 level. It is then essential to highlight the new setting that statistical data allowed in the scale, inasmuch as four factors were expected (Belongingness, Agreeableness, Destruction and Insecurity) and only two were proven.

Table 2. Factorial Structure of the Esteem for the Place Scale

Items IFactorsII h² α

56. I feel attached. 0,77 0,55 0,83

47. I love it. 0,76 0,60 0,83

50. It has everything to do with me. 0,75 0,60 0,83

39. It’s attractive for me. 0,75 0,57 0,83

32. I feel that I belong. 0,71 0,49 0,83

43. It makes me proud. 0,70 0,54 0,83

36. I have pleasure. 0,67 0,56 0,83

26. If I’m not in it, I want to go back. 0,66 0,45 0,83

28. I feel identified with it. 0,64 0,51 0,83

49 I have fun. 0,62 0,45 0,90

29. I admire its beauty. 0,59 0,47 0,83

09. I consider it part of my story. 0,55 0,28 0,84

54. I would defend it if necessary. 0,53 0,30 0,83

07. I wouldn’t change it for anything. 0,49 0,33 0,83

35. The things that happen to it are important for me. 0,45 0,20 0,84

01. I consider it like something mine. 0,45 0,20 0,84

23. I have opportunities. 0,41 0,21 0,84

17. I’m scared. 0,77 0,56 0,87

16. There are risks. 0,75 0,49 0,87

19. Danger is constant. 0,72 0,51 0,87

51. It’s destroyed. 0,68 0,58 0,87

52. I have the feeling that something bad may happen. 0,67 0,44 0,87

11. It looks abandon. 0,63 0,44 0,87

05. I feel relaxed. -0,63 0,47 0,90

04. I have the feeling that I am helpless. 0,61 0,41 0,87

48. I must be alert. 0,60 0,31 0,88

45. I feel insecure. 0,60 0,45 0,87

18. It’s bad. 0,60 0,57 0,87

24. I feel peaceful. -0,59 0,53 0,90

53. There is dirt. 0,58 0,31 0,87

41. I feel that I am unsafe. 0,57 0,46 0,88

21. It makes me mad. 0,57 0,55 0,87

46. It’s despicable. 0,54 0,43 0,87

20. I think it’s ugly. 0,54 0,58 0,87

03. It’s polluted. 0,53 0,29 0,88

25. With substandard structures. 0,53 0,26 0,88

30. It makes me angry. 0,50 0,44 0,87

13. It embarrasses me. 0,49 0,36 0,87

12. I don’t trust people. 0,48 0,23 0,88

33. I feel suffocated. 0,47 0,36 0,87

55. Anything can happen. 0,46 0,20 0,88

Number of itens 17 24 Eigenvalues 16,06 4,53 Total Explained Variance (%) 28,6 8,1 Cronbach´s (α) 0,84 0,88

Factor I. Potentiating Esteem of Action and involvement in the environment. Factor II. Not-Potentiating Esteem of Action and Involvement in the environment. Note 1: minimal factorial loading satisfactory |0,40|

Data analysis results of questionnaire

The results obtained from the analysis of drawings and inquiry of the sample that responded to the complete instrument were distributed in terms of frequency of emer-gence of categories of Esteem for the Place.

These results show there was a greater concentration on Non-Potentiating of Action and involvement in the environment, since the categories of Insecurity and Destruction totaled 37.7% frequency in this sample compared to Belongingness and Agreeableness (Potentiating Esteem), which amounted to 29%. However, in this analysis it is pos-sible to identify the Contrast category in cases where there is a duality in the affective representation about the environment, i.e. esteem interposed between two polarities, totaling 33%.

Figure 2. Draw and inquiry analysis results (n=69).

Figure 2. Drawing and inquiry analysis results (n=69).

The score analysis of the Esteem for the Place scale yielded results based on the means of all subjects for each of the factors. For the overall sample, it was found that the Potentiating Esteem for action and involvement in place had a mean of 3.42 (n = 246, SD = 0.67) and the Non-Potentiating of Action overall mean obtained 3.05 (n = 224, SD = 0.68), which did not allow us, from the statistical point of view, to infer that there is a significant difference between the two scores.

An Esteem for the Place coefficient (e) was then produced, calculated by simple subtraction of the individual scores from factor I (Potentiating Esteem) and factor II (Non-Potentiating Esteem) in accordance with the following formula.

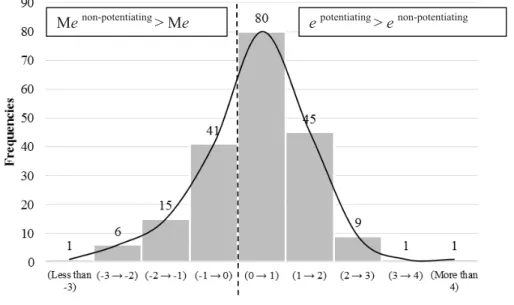

This calculation produces positive results when the scores from factor I exceed the scores from factor II and negative in the reverse situation. We then traced a diagram with coefficients grouped in accordance with Figure 3.

e potentiating

> enon-potentiating Menon-potentiating > Me

Figure 3. Distribution of Esteem for the Place coefficients by groups (n = 199).

It is easy to check that there is a concentration of Esteem for the Place coefficients (e) above 0 (zero), which could indicate that, in general, the sample demonstrated a higher potentiating esteem than non-potentiating esteem about the place. However, it is also observed that the highest concentration of coefficients is established at points very close to zero. The closer this value the smaller the differences between the means of the two types of esteem.

Discussion

The Dialogue between Qualitative and Quantitative Methods

Quantitative analysis facilitates the improvement of the generator questionnaire of affective maps towards the construction of precise and valid items, which can be used for various types of environment without the need to apply a pre-test, making the survey faster and more consistent. We confirm our hypothesis for this project that has been tested in previous research, that the categories Agreeableness and Belongingness, and Insecurity and Destruction compose the potentiating and non-potentiating Esteem for the place, respectively.

The qualitative and quantitative dialogue promotes a better understanding of the phenomenon in the research when it comes to affection, feelings and emotions. The questionnaire of affective maps can be an option for that. This dialogue between quali-tative and quantiquali-tative methods in the evaluation of affectivity with the environments helps overcome the dualities like subjectivity/objectivity, individual/collective, cogni-tion/affection and social/environmental.

When we look at the results obtained from the analysis of the scores from the EEL and the proximity of most of the Esteem for the Place coefficients (e) to zero, we can infer that for most of the sample the differences between potentiating and non-poten-tiating esteem are very small. The calculation of the coefficient shows how for almost the entire sample both types of esteem coexist in the representations of each subject, generally having esteem or another aspect more relevant to the individual. However, it is likely that for most of this sample for which the result of the difference is very small, the coexistence of the two types of esteem is more even, meaning in such cases that the two exert strong influences on the construction of emotional images about people’s environments.

For these cases, then, it is possible to speak theoretically of a contrasting image of the place. For this reason, we took into consideration the fact that it is not possible at the moment of the study to conclude with any certainty coefficient values which are sufficient and satisfactory to indicate a prevalence of estimates on the other. Thus, we consider that the range between negative and positive results that are very close to zero to reflect the possibility of including images of contrasts results in quantitative analyses.

This was due to the lack, so far, of more comprehensive studies that include the standardization of criteria for the interpretation of results and allows the more precise inference of what the results of the estimated coefficients indicate of the place in ques-tion.

Thus, the results of the scores could also be interpreted in the light of the results of the analysis of the design and investigation, showing the presence of the category contrasts quite significantly as shown in Figure 2. The contrast as transversality in the categories of Esteem for the Place was one of the main results of the research. In re-searches conducted between 2003 and 2012, the contrast category was defined just as a category of environmental assessment. It was understood at that time, that besides a theoretical category and presenting analysis mainly on the qualitative part of IGMA, the contrast refers to the coexistence of different forms of representations borne by dif-ferent environments and/or opposing forces.

and quiet, beautiful and ugly, violent and peaceful, besides bringing feelings such as love and hate, joy and sadness.

In this research, ambivalent feelings were evident with the neighborhood where they live, in terms of positive feelings involving the bond of attachment to the place, the tranquility of a neighborhood far from downtown and while lacking in infrastruc-tures for its residents, besides the insecurity, the destruction that generates feelings of anger, helplessness, and fear.

Understanding that Potentiating Esteem for the Place promotes the involvement of youth in their neighborhood, the Contrast can be an increasing potential for action, when negative feelings do not imprison, or do not lead to suffering (Sawaia, 2009). On the other hand, the potential increasing of action, even with ambivalent feelings, leads to a solution to the problem faced, as we can see in the discourse of subject 131: “I see my neighborhood as a prison by presenting contrasting feelings of joy and happiness”. However, he shows, at the same time, that the lack of opportunities can improve with the construction of leisure areas, increasing policing and improving the streets, etc.

To conclude, it could be understood that in addition to corroborating the data of the other, the dialogue between the different methods of data collection and analysis may even facilitate the interpretation of the data when a stream of reference and counter-reference is created between them. This was important to avoid possible rigidities in the forms of assessment and interpretation of the results of our instruments.

References

Bomfim, Z.A.C. (1999) A mediação emocional no desvelar da Identidade na Psicologia Comunitária. In I.R. Brandao & Z.A.C. Bomfi (Organizadores). Os Jardins

da Psicologia Comunitária (pp. 99-110). Fortaleza: Editora UFC.

Bomfim, Z.A.C. (2003a) Cidade e afetividade: estima e construção dos mapas

afetivos de Barcelona e São Paulo. São Paulo, SP: Pontifícia Universidade Católica

de São Paulo.

Bomfim, Z.A.C. (2003b). Protagonismo Social da Psicologia no Campo da Circulação Humana. In: Conselho Federal de Psicologia. II Seminário Nacional de

psicologia e políticas públicas:Políticas públicas, psicologia e protagonismo social

(pp. 86-114). João Pessoa.

Bomfim, Z.A.C. (2010) Cidade e Afetividade: Estima e Construção dos Mapas

Afetivos de Barcelona e de São Paulo (1. ed.) Fortaleza: Edições UFC.

Bomfim, Z. A. C.; Alencar, H. F. Santos, W. S.; Santos, W. S. (2013) Estima de Lugar e Indicadores Afetivos: Aportes da Psicologia Ambiental e Social para a com-preensão da vulnerabilidade social juvenil em Fortaleza. In: Colaço, V. F. R.; Cordeiro, A. C. F (Orgs.). Adolescência e Juventude: conhecer para proteger. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo.

Corraliza, J. A. (1998) Emoción y ambiente. In J.I. Aragonés & M. Amérigo:

Psicologia ambiental (pp. 59-76).Madrid: Ediciones Pirâmide.

Giuliani, M. V. (2004). O lugar do apego nas relações pessoas-ambiente. In: E. T. Tassara, E.P. Rabinovich & M.C. Guedes. Psicologia e ambiente (pp. 89-106). São Paulo: Educ.

Koller, S., Moraes, N. A., Cerqueira-Santos, E. (2009). Adolescentes e Jovens Brasileiros: Levantando Fatores de Risco e Proteção. In Libório, R., S. H. Koller (Orgs.). Adolescência e Juventude: Risco e Proteção na Realidade Brasileira. São

Paulo.

Lynch, K. (2010).A imagem da cidade. Tradução de Jefferson Luiz Camargo. 2. ed. São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes. (Coleção Mundo da Arte).

Pasquali, L. (Org.) (2010) Instrumentação Psicológica: Fundamentos e Prática. 1. ed. Porto Alegre: Editora Artmed.

Pol, E. (1996) La Apropiación del Espacio. In Iñiguez, L.; Pol, E. (orgs). Cognición,

representación y Apropriación del Espacio. Barcelona: Publicacions Universitat de

Barcelona, Monografies Psico/Sócio/Ambientais, (V. 9).

Pol, E.; Valera, S. (1999) Synbolisme de l’espace public et identitée sociale. Villes

en paralélle. Pp. 28-29

Proshansky, H. M. (1978) The city and the self-identity. Environment and Behavior, 10(2), 147-169.

Proshansky, H. M.; Fabian, A. K.; Kaminoff, R. (1983), Place-Identity: Physical world socialization of the self. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3, 57-83.

Santos, M. (1998). O espaço do cidadão (4a ed.). São Paulo: Nobel

Sawaia, B. B. (1995). O calor do lugar, segregação urbana e identidade. São Paulo

em perspectiva. v. 9, n. 2. pp. 20-24.

Sawaia, B. B. (1995). Psicologia e desigualdade social: Uma reflexão sobre liber-dade e transformação social. Psicologia & Sociedade, v. 21 n. 3, p. 364-372, 2009.

Sawaia, B. B. (1995). O sofrimento ético-político como categoria de análise da dialética exclusão/inclusão. In B.B. Sawaia (Org.). As Artimanhas da Exclusão:

aná-lise psicossocial e ética da desigualdade social. 11ed. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2011b.

p. 99-119.

Spinoza, B. (2005). Ética:demonstrada à maneira dos geômetras. São Paulo, SP: Martin Claret.

Tabachnick, B. G.; Fidell, L. S. (2001) Using Multivariate Statistics. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Tuan, Y. (1983) Espaço e lugar: A perspectiva da experiência. Tradução de Lívia de Oliveira. São Paulo: Difel, 1983, pp. 106-128.

Vygotsky, L. S.(1996) El problema del desarollo de las funciones psíquicas su-periores. In L.S. Vygotsky: Obras Escogidas: Problemas del desarrollo de la psique. Tomo III. Madrid: Visor.