Knowledge creation in small-firm network

Alsones Balestrin, Lilia Maria Vargas and Pierre Fayard

Abstract

Purpose– The purpose of this research is to aim to understand how the dynamic of knowledge creation takes place within a small-firm network (SFN).

Design/methodology/approach– The research, qualitative in nature, was developed through the case study of the Clothing Industries Association, called AGIVEST, formed by 35 small clothing industries located in southern Brazil. This article attempts to offer a more comprehensive approach towards the creation of organizational knowledge, by shifting from an endogenous process of the individual firm to a multidirectional exogenous process within networks.

Findings– The research presents evidence that the context of a cooperation network may provide an environment of collective learning, represented above all by the interaction dynamic that occurs between the firms through the creation of several types ofba(specific context in terms of time, space and relationship), which support the process of knowledge creation.

Originality/value– This approach should consider the tacit, complex, interdependent and contextual nature of knowledge, overcoming the eminently IT-oriented view defended by the Western perspective of knowledge management. It is intended that the evidence presented encourages debate and a critical attitude concerning the concepts of knowledge creation, cooperation and SFN in the academic community.

KeywordsKnowledge creation, Small enterprises, Knowledge management Paper typeResearch paper

Introduction

Within a given perspective, which in this article will be called informational society, the capacity of individuals and organizations to generate, process and transform information and knowledge into economic assets is presented as the main factor promoting productivity and competitiveness. Some authors, such as Prahalad and Hamel (1990), Nelson (1991), Kogut and Zander (1992), Grant (1996), Nonakaet al. (2002), consider that the ability to create and use knowledge is a major source of sustainable competitive advantages for firms. However, the Western management epistemology has oversimplified the nature of organizational knowledge, especially by granting privilege to the explicit and individual nature with regard to the tacit and collective nature of knowledge (Cook and Brown, 1999).

According to Schultze and Leidner (2002), this oversimplification has been represented by the normative discourse, which defends the rational nature of knowledge and considers the possibility to manage and control it. For the authors of the normative literature (Zhaoet al., 2001; Dhaliwal and Benbasat, 1996; Gregor and Benbasat, 1999; Lee and O’Keefe, 1996; Nissen, 2000), knowledge is seen as an object that can be found outside the individual and is possible to be stored, manipulated and transferred by means of information technologies (IT). These principles of the normative discourse have been widely disseminated in the literature on knowledge management.

On the other hand, the interpretative discourse has considered knowledge to be closely connected to organizational practices. The authors of the interpretative literature (George et al., 1995; Robey and Sahay, 1996; Brown, 1998; Schultze and Boland, 2000; Scott, 2000; Stenmark, 2001) prioritise the role of knowledge in the organizational transformation without considering it an objective datum or asset.

Thus, the following comparative situation may be established: whereas in the normative discourse the focus is on problem solving by means of knowledge repository, in the interpretative discourse the focus is on work processes and practices and the principle of knowledge being socially constructed, through the interaction between individuals, is defended.

Aligned to the interpretative discourse and based on studies by Polanyi (1966), Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995), they support the thesis that high value knowledge for the organization has the following dimensions: it is tacit, since it is intimately related to action, procedures, routines, ideas, values and emotions; it is dynamic, since it is created within social interaction between individuals, groups and organizations; and it is humanistic, for being essentially related to human action. According to the authors, these characteristics make knowledge something very difficult to manage.

Along this line of thought and vision of Nonaka et al. (2002), a strategic factor for organizations is the potential to create new knowledge, which is much more relevant than the attempt to manage it. For Barney (1991) and Leiet al.(1996), a major knowledge asset within a firm is the capacity to continuously create new knowledge instead of stocking it as a specific technology that the firm has at a given moment.

Considering this situation, the question that arises is how to put organizations in a position to produce and use such a resource? Nonaka et al.(2002) emphasize that the favourable conditions to the creation of knowledge within an organization go through the SECI method (Socialization – Externalization – Combination – Internalization), but the emergence of aba is essential – it is a Japanese concept that means a physical, virtual or mental space within which knowledge is generated, shared and used.

However, according to the evidence presented by Nonakaet al.(2006), it can be seen that the essence of the research on the theory of the creation of knowledge has been limited to the study of the internal aspects and in large organizations. Little attention has been given to external aspects and to cooperative relations in the creation of knowledge within small firms (SF).

The present article attempts to understand how the dynamic of knowledge creation occurs within a small firm network (SFN). Aiming to achieve the proposed objective, the article is structured in the following manner: it starts with a consideration on the perspective of knowledge creation within organizations, followed by a close examination of the conceptual aspects of inter-organizational networks; next, the central thesis of the debate will be presented: knowledge creation in the context of SFN. Afterwards, the methodology used in the research is summarized, as well as the analysis of the main results. Finally, some considerations on the implications and the conclusions of the study will be highlighted.

Theoretical references

Knowledge creation

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) called knowledge conversion the process with which organizations create knowledge. It is by means of this conversion that the tacit and explicit

knowledge is qualitatively and quantitatively expanded. There are four modes of knowledge conversion: socialization (conversion of tacit knowledge into tacit knowledge); externalization (conversion of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge); combination (conversion of explicit knowledge into explicit knowledge); and internalization (conversion of explicit knowledge into tacit knowledge).

In order to make the SECI process effectively occur, a proper context is necessary. For Suchman (1987), knowledge does not exist only in the individuals’ cognition. Therefore, to make the process of knowledge creation effectively occur, a specific context is necessary in terms of time, space and relationship between individuals. Nonakaet al.(2006) call such a contextba, which has the function of serving as a platform of knowledge creation. Since there is no knowledge creation without a place, the concept ofbaaims to unify the physical space (such as the physical space of a meeting room), the virtual space (such as the e-mail or a virtual community) and the mental space (such as shared ideas and mental models).

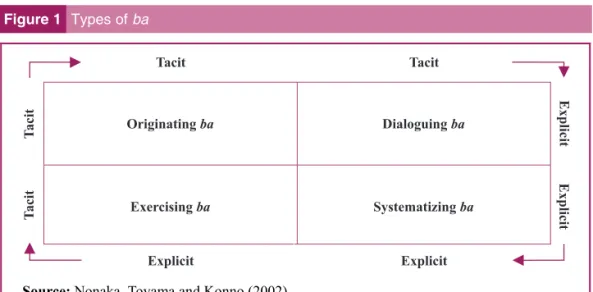

Nonakaet al.(2002) present four groups ofba: originatingba, dialoguingba, systematizing ba and exercisingba. Each one of these basupports a particular mode of knowledge conversion in the stages of the SECI process, as represented in Figure 1.

The originatingbaallows knowledge to be socialized by means of face-to-face interaction, in which the individuals share feelings, emotions, experiences and mental models. The dialoguing ba is a situation in which, by means of dialogue, individuals share their experiences and abilities, converting them into common terms and concepts. The systematizingbaoffers a context for the combination of new explicit knowledge with the one that already exists within the organization. And finally, the exercising ba allows the knowledge that was socialized, externalised and systematized to be once again interpreted and internalised by the individuals’ cognitive system as new concepts and work practices. It can be thus noted that different ba may emerge from work groups, informal circles, temporary meetings, virtual spaces and other moments in which the relationships take place in a shared time and space.

The evidence presented points to the crucial issue of how organizations can develop the potential of their processes of knowledge creation. The literature on the theory of organizational knowledge has generated answers that are mostly based on an endogenous view of the process of knowledge creation within large organizations. As Wong and Aspinwall (2004) point out, while few studies have attempted to understand the process of knowledge management within the context of SF among those of particular note are Lim and Klobas (2000), uit Beijerse (2000), Frey (2001), Sparrow (2001), McAdam and Reid (2001) and Wiklund and Shepherd (2003). These studies highlight the fact that SF present distinct characteristics form large firms and that, given this, they should be considered as something

other than a ‘‘little large businesses’’, in order that knowledge management projects might be successful.

It can be seen that studies that take into consideration the characteristics of SF in knowledge creation projects are increasingly important, as ‘‘the competitiveness of SF will increasingly depend on the quality of the knowledge they apply to their business processes and the amount which is embedded in their outputs’’ (Wong and Aspinwall, 2004, pp.47). For these authors, SF have certain advantages in comparison with large firms in relation to knowledge management projects, as, for example, the lower number of employees and the greater degree of cooperation among them, simpler processes that facilitate the implementation of new ideas, a unified culture that offers a strong base for change, simple structures, direct communication with and the proximity of higher management and operational levels. Nonetheless, Wong and Aspinwall (2004) emphasize that it is undeniable that SF experience serious restrictions, such as lack of financial, technical and human resources that may put the implementation of knowledge creation and management projects at risk.

In order to attenuate such restrictions and the lack of resources within SF in the processes of creating knowledge and learning, some recent studies (Powell, 1998; Cornoet al.1999; Michelis, 2001; Chua, 2002; Tsai, 2002; Spencer, 2003, Muthusamy and White, 2005) have demonstrated the importance of interorganizational relations in the process of the emergence of new knowledge. These authors argue that a network is more effective than a ‘‘lone’’ firm in the process knowledge creation, transfer and systematization. The results of these studies stimulate and guide this article towards achieving a better understanding how a SFN can undergo the process of knowledge creation.

Small-firm network

It is based on the awareness of the necessity for joint action and cooperation between the SF, in an effort to become efficient and competitive, that the logic of network action emerges. However, even with the acknowledged capacity of collective efficiency through network action, few authors have dedicated themselves to the study of SFN configuration. Human and Provan (1997) highlight the existence of only a few individual studies, such as that of Inzerilli (1990), who used the perspective of transaction costs to describe how trust in a social context favours the success of SF in northern Italy. Brusco and Righi (1989), as well as Lorenzoni and Ornati (1988), confirmed the importance of environmental factors for the growth of SF through networks. Saxenian (1994) described in his study the emergence of an infrastructure in the United States to support the ‘‘European style’’ of cooperative systems.

For Perrow (1992), the form of production represented by the large integrated firm, originally defended by Chandler (1977), has become a declining model in the face of contemporary needs for flexibility. Perrow (1992) adds that the problem of Chandler’s (1977) theory was to completely neglect the role given to trust and cooperation in economic models. The dimension of trust and cooperation possibly represents a key role in the success achieved by SFN, which will hardly be achieved by other forms of networks between large firms and much less by large integrated firms. This fact was stated by Sabel (1991), who points out that trust may never be intentionally created, but generated based on a proper structure or context. Given this evidence, Perrow (1992) argues that, although trust cannot be created, it can be encouraged by a deliberately created structure or context.

It is worth highlighting that within the term SFN, developed by Perrow (1992) and Human and Provan (1997), the following characteristics are stressed: a group of firms are gathered; they are located geographically close; they operate in a specific market segment; they establish horizontal and cooperative relationships between their actors; they are formed for an undetermined period of time; mutual trust relationships between firms prevail; and they are structured based on minimum contractual instruments, which assure basic rules for their coordination.

Knowledge creation in small-firm networks

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) demonstrated the creation of new knowledge based on the interaction between individuals, groups and organizations. For the authors, knowledge emerges at an individual level, and is expanded by the interaction dynamic – knowledge socialization – to an organizational level and, afterwards, to an inter-organizational level. It is then observed that the knowledge is created only by individuals; an organization or an inter-organizational network cannot create knowledge, but it can provide a space for positive and constructive relationships between the actors. The exchange of data, information, knowledge and competencies at a given project of inter-organizational network may converge to a singular context for the creation of strategic knowledge for the competitiveness of organizations.

In order to make the process of inter-organizational knowledge creation effective, it is necessary to have an environment of synergy and stimulation, in which emotions, experiences, feelings and mental images are shared beyond the organizational borders. As Tsai (2002) points out, this environment cannot be produced by the ‘‘command and control’’ model of the traditional firm, but by the organizational configurations adapted to these new challenges that are presented to the organizational management.

Thus, it can be noted that an inter-organizational network may provide the existence of an efficient interaction between people, groups and organizations, inter-organizationally widening the knowledge initially created by the individuals. This dynamic offers the complementarity of competencies by which the individuals’ knowledge, practices, values, processes, culture and differences are collectively shared in favour of a common project. For Corno et al. (1999), the networks represent the place where learning processes and knowledge consolidation take place.

The theories presented here point out that the network configuration may facilitate the emergence ofbathat is favourable to the process of knowledge creation. In order to better understand how this dynamic occurs and its potential contribution for the SFN, we attempted to find empirical evidence based on a case study performed in a SFN located in southern Brazil, which will be presented next.

Methodological procedures

The case selected for the research was the Clothing Industries Association of Rio Grande do Sul, called AGIVEST, formed by 35 small clothing industries located in southern Brazil. AGIVEST is part of the Cooperation Networks program, developed by the State Government of Rio Grande do Sul (RS). It was created in September 2001 with the aim of expanding the market, promoting technological improvements and reaching a higher competitiveness for the small-firms that are part of the program.

The choice for the AGIVEST as a study object was due to the following reasons: for being an SFN with only two years of existence and that could already present concrete results; for being an industrial SFN that aims to innovate their products to better compete in the national market, which can be demonstrated by the launching of a set of products at a national fair; for the interest expressed by the Secretary of Development and Foreign Affairs (SEDAI) of the State Government of Rio Grande do Sul in studying AGIVEST, by providing meetings between the researcher and the consultant, president and businessmen belonging to this network; and for being an industry network that works from product development to commercialisation, which is more appropriate for the theoretical constructs of the research, such as, for example, information and knowledge needed for the innovation processes in the competitive world of fashion.

The research operationalisation took place based on the systematisation between the conceptual elements, the authors and the corresponding variables. This structuring logic allowed a better adequacy between the variables to be observed and the underlying theoretical constructs, as can be seen in Table I.

The empirical evidence was collected from seven interviews made with the following actors: five interviews with AGIVEST SF managers randomly chosen, one interview with the AGIVEST consultant and one interview with the network president. Each interview lasted for approximately 60 minutes and they were all performed by the researcher. An interview script was used – which was created based on the constant research variables in Table I – with the aim to present a logical sequence of the questions to the interviewees. Besides the interviews, other evidence was collected by the researcher while attending a meeting of the AGIVEST, especially to observe the coordination dynamic and collective decision making.

The interviews were taped and then transcribed. The results of the interviews and observations made by the researcher were compared with the conceptual elements.

Table I Operationalization of research variables

Conceptual elements Authors Research variables

SFN networks Sabel, 1991; Saxenian, 1994; Oliver and Ebers, 1998; Fayard, 2004; Marcon and Moinet, 2000; Human and Provan, 1997; Perrow, 1992

Geographical proximity between firms; Number of firms involved;

Type of business (industry, commerce or service); Type of product;

Coordination instruments;

Formalization level concerning the relationships between network firms (formalvs.informal); Hierarchy level concerning the relationships between firms (hierarchyvs.cooperation);

Cooperation levelvs.competition between network firms;

Objectives underlying network formation

Knowledge creation Polanyi, 1966; Barney, 1991; Cornoet al., 1999; Michelis, 2001; Chua, 2002; Nonakaet al., 2002; Schultze and Leidner, 2002; Spencer, 2003 and Tsai, 2002

Types and amount of originatingba(social gatherings, visits to industries, other informal meetings);

Types and amount of dialoguingba(formal meetings, collective decision process making, planning meetings);

Types and amount of systematizingba(electronic communication, formal documents, database, shared management systems);

Types and amount of exercisingba(new management and production concepts and practices, other actions of knowledge application); Trust in the sharing of information and knowledge; Firms’ opportunism with regard to the existing knowledge in the network;

According to guidelines by Yin (1989) and Wacheux (1996), this procedure aims to achieve a better understanding of the phenomenon being studied, as well as of the theoretical implications of the research. The interviews were first individually analysed, and later as a whole, in an attempt to identify similar and convergent elements that could have an impact on the research conclusions.

Results and discussion

AGIVEST case

In December 2000, the State Government of Rio Grande do Sul launched the Cooperation Networks program, in an effort to promote and strengthen the cooperation between the SFN. Two years after its launch, 33 SFN were formed in several economic segments, comprehending 733 firms and a total of 5,000 employees. The program has the support of six universities, which provide 42 consultants to help the formation and management of the network. There are also other actions that strengthen and favour the development of networks, such as easy access to credit, the development of management capacitation and the fulfilment of specific network demands, such as the incentive and the participation in trade fairs.

The main characteristics of the AGIVEST are the following: it is essentially formed by small-firms with an approximate average number of six employees; the firms are geographically close to each other (within a radius of 90 km); all firms operate in the clothing segment; the network management structure consists of a president and a vice-president, with the supervision of the administration council, the ethics council and the fiscal council; the strategic network decisions are made by means of a general meeting, and the controversial issues may be solved by applying some legal instruments, such as the network statutes, code of ethics and internal regulation.

According to these characteristics and based on the guidelines proposed by Perrow (1992), Human and Provan (1997) and Marcon and Moinet (2000), the AGIVEST can be classified as a horizontal cooperation network. In contrast to other typologies of SFN, such as the outsourcing vertical networks, horizontal networks are formed by SF with the aim to work in cooperation to achieve certain strategic objectives that would hardly be achieved if the firms acted individually.

Knowledge creation within the AGIVEST network

One of the unanimous answers obtained in the research was that the most considerable gain firms obtained by means of the AGIVEST was the sharing of information and knowledge between the firms. The shared information that brought most benefits to the network was related to production processes, suppliers, inputs, technologies and markets. Such information was shared through an intense social inter-relationship, which occurs informally between the businessmen.

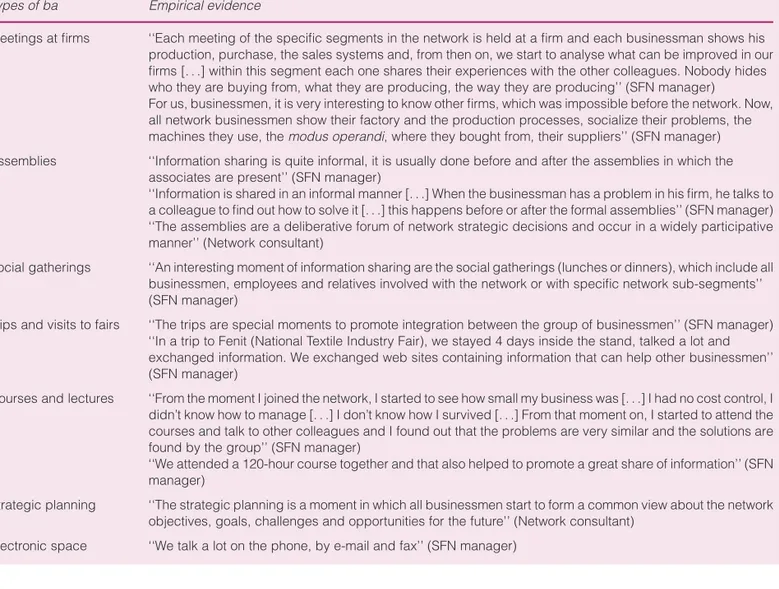

Several spaces in which information and knowledge sharing takes place in the network were identified. Following the guidelines by Nonakaet al.(2002), each type ofbaidentified works as different situations that promote an effective ‘‘platform’’ to make the process of knowledge creation easier between the network firms. The types ofbawere identified based on the data collected and are presented in Table II.

The assembly, which is held at least once a month, has become a relevantbaof network knowledge sharing. It works as a formal forum for the collective process of strategic decision making. The decisions are taken in a process of debate and thinking, so that a satisfactory choice is made. At the assembly attended by the researcher, one fact that caught the attention was that some businessmen arrived early to the place and started to talk informally to other network businessmen. At the end of the assembly, one businesswoman said the informal conversations that are held before and/or after these meetings favour the discussion of specific issues between the participants, such as solutions for problems related to production, a new supplier or representative and new raw material. This fact confirms the claim made by Tsai (2002, p. 179), in which ‘‘informal lateral relationships, in the form of social interactions, have a significant effect on knowledge sharing’’.

SFN, since they are inserted in a community environment with strong social relationships, often combine friendship and business simultaneously. One example is the social gatherings – such as lunches or dinners – which occur between businessmen, employees and relatives involved with the network. These moments are important to strengthen trust-based relationships. Moreover, they provide informal conversations on opportunities, challenges and the future of the network and its firms. It can be noted that trust – essential for the existence of cooperation – is established more by informal and face-to-face means, as argued by Rosenfeld (1997) in a critique directed to the massive use of IT in the communication process between the actors within a network.

Events such as trips, visits and exhibitions of products in fairs give the businessmen the opportunity to know other experiences and think together about the trends and challenges.

Table II Types ofbaidentified in the AGIVEST

Types of ba Empirical evidence

Meetings at firms ‘‘Each meeting of the specific segments in the network is held at a firm and each businessman shows his production, purchase, the sales systems and, from then on, we start to analyse what can be improved in our firms [. . .] within this segment each one shares their experiences with the other colleagues. Nobody hides who they are buying from, what they are producing, the way they are producing’’ (SFN manager)

For us, businessmen, it is very interesting to know other firms, which was impossible before the network. Now, all network businessmen show their factory and the production processes, socialize their problems, the machines they use, themodus operandi, where they bought from, their suppliers’’ (SFN manager)

Assemblies ‘‘Information sharing is quite informal, it is usually done before and after the assemblies in which the associates are present’’ (SFN manager)

‘‘Information is shared in an informal manner [. . .] When the businessman has a problem in his firm, he talks to a colleague to find out how to solve it [. . .] this happens before or after the formal assemblies’’ (SFN manager) ‘‘The assemblies are a deliberative forum of network strategic decisions and occur in a widely participative manner’’ (Network consultant)

Social gatherings ‘‘An interesting moment of information sharing are the social gatherings (lunches or dinners), which include all businessmen, employees and relatives involved with the network or with specific network sub-segments’’ (SFN manager)

Trips and visits to fairs ‘‘The trips are special moments to promote integration between the group of businessmen’’ (SFN manager) ‘‘In a trip to Fenit (National Textile Industry Fair), we stayed 4 days inside the stand, talked a lot and exchanged information. We exchanged web sites containing information that can help other businessmen’’ (SFN manager)

Courses and lectures ‘‘From the moment I joined the network, I started to see how small my business was [. . .] I had no cost control, I didn’t know how to manage [. . .] I don’t know how I survived [. . .] From that moment on, I started to attend the courses and talk to other colleagues and I found out that the problems are very similar and the solutions are found by the group’’ (SFN manager)

‘‘We attended a 120-hour course together and that also helped to promote a great share of information’’ (SFN manager)

Strategic planning ‘‘The strategic planning is a moment in which all businessmen start to form a common view about the network objectives, goals, challenges and opportunities for the future’’ (Network consultant)

For example, by attending an exhibition of products of the AGIVEST at the National Textile Industry Fair (Fenit), held in Sa˜o Paulo, the businessmen observed that the differentiated and sophisticated products were the ones with the highest demand. This market knowledge can become a competitive advantage when developing the marketing strategies for the network.

In order to improve the managerial development of the network businessmen, the State Government of Rio Grande do Sul provided courses of management capacitation. In these 120-hour courses, the businessmen develop management concepts and techniques. Management learning is relevant when the network works with a single brand. Thus, the standards of products and processes must be observed by all firms, in order to guarantee an acceptable quality of the products of the AGIVEST brand.

Another example ofbaobserved in the AGIVEST is the development of the network strategic planning. The planning is developed in a participative manner by all the network businessmen. Collective thinking, as in the case of the SWOT matrix (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats), provided a vision of the network future. Therefore, by involving all network members in the definition of objectives, strategies, goals and schedules, this process, besides representing an opportunity for high learning, attempts to create a commitment in the group to perform the actions based on what has been planned.

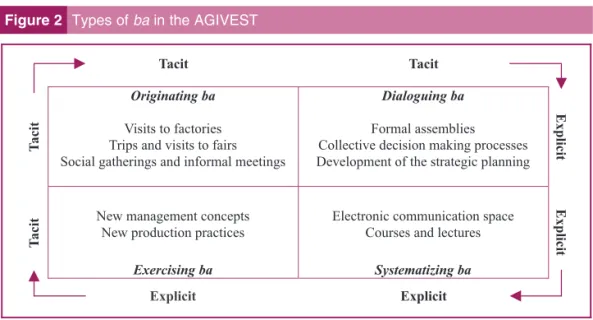

The use of electronic resources – e-mail, telephone and fax – was observed in the dynamic of network knowledge creation. The telephone and the fax are more frequently used, whereas the internet and other IT are less used. This evidence represents an issue that needs to be strengthened in the AGIVEST with regard to its dynamic of knowledge creation, according to the following analysis. In Figure 2, we propose a classification of the several types ofbaidentified in the process of knowledge creation in the AGIVEST.

The originatingbaemerges from the visits to the factories, when the businessmen directly observe the solutions and the best practices adopted by other businessmen. Moreover, during the trips, social gatherings and other informal meetings, the businessmen also share their experiences, emotions and feelings by means of informal interaction.

The dialoguingbatakes place at formal assemblies, at meetings to develop the strategic planning and at collective decision making processes. These activities allow the businessmen – through dialogue and collective thinking – to share ideas and experiences (tacit knowledge), converting them into common concepts, in the form of models, hypotheses and scenarios (explicit knowledge).

The systematizingbaoccurs, for example, during the courses and lectures, as well as by using the IT to make this process easier. However, the resources for the systematisation of knowledge are fragile and deficient, especially due to the lack of use of IT systems.

The exercisingba, which supports the last stage of the SECI process, in which knowledge is internalised and applied in terms of new organizational practices, led to good results, such as the application of new management concepts and reengineering of production processes at SFN.

By analysing the different types ofbain the AGIVEST, a context of strong interaction among businessmen can be observed. This interaction, which mainly occurs informally and face-to-face, offers a valuable basis for knowledge creation. According to authors as Nonaka and Nishiguchi (2001), most, if not all, knowledge is created through an interactive process of experimenting and dialoguing, which involves several individuals. From the point of view of other authors, such as Soo et al. (2002), for many organizations the informal communication channels have been a rich source of knowledge that cannot be found in databases or company manuals. The importance of the informal interaction is a crucial element for the creation of knowledge, especially when the knowledge is systemic, complex and tacit (Bhagatet al., 2002).

Concluding remarks

An effective process of knowledge creation, supported by the different types ofba, allows the emergence of essential knowledge assets for the creation of value and competitive differential for firms. In the AGIVEST, it was possible to find the emergence of knowledge assets that are certainly providing competitive advantages compared to the SF that work alone. According to the results of the research, the firms working as a network received new production concepts and know-how, new product designs, better understanding of the scenario of networking, patent and trademark registry, product specifications, knowledge of suppliers and representatives, knowledge of new technologies and raw materials. The intangible assets, resulting from the firm learning, are already contributing towards the improvement of production processes and the launching of new products by the firms within the AGIVEST.

According to the results of the research, we observed that the social interaction provided by the network configuration had a positive influence on the dynamic of knowledge creation within the SFN. The existence of formal and informal situations so that the businessmen can share abilities, experiences, emotions and know-how, by means of face-to-face communication, promoted an environment of intense sharing of tacit knowledge in the AGIVEST, which is an essential resource for the sustainability of competitive advantages over the long term.

As a research conclusion, we point out that the inter-relational structure of a network can develop the potential of the process of knowledge creation within SFN, reinforcing some evidence previously mentioned in the literature. For example, Richardson (1972) argues that network cooperation may favour the complementary gathering of abilities from different firms. Teeceet al.(1994) point out that the learning process is an intrinsically social and collective phenomenon. Ahuja (2000) also shows that the direct relationships between the actors within a network positively affect the result of innovation.

Nevertheless, such evidence must be confronted with other existing studies in the literature on organizational networks. Some research has demonstrated that network closure made possible by strong ties between the internal actors are less effective in the innovation processes (Granovetter, 1973; Burt, 1992; Ruef, 2002). This ‘‘perverse’’ effect is particularly caused by the redundancy of information as a consequence of the actors’ isolation from the environment external to the network. According to Walkeret al.(1997), such a problem is more related to the market transaction networks – such as, for instance, outsourcing networks – than the cooperation networks between small-firms, which are similar to the AGIVEST.

be a definitive theory, but aims to encourage debate and critique concerning the concepts of knowledge creation, cooperation and SFN development in the academic community.

References

Ahuja, G. (2000), ‘‘Collaboration networks, structural holes, and innovation: a longitudinal study’’,

Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 45 No. 3, pp. 425-55.

Barney, J.B. (1991), ‘‘Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage’’,Journal of Management, Vol. 17 No. 1, pp. 99-120.

Bhagat, R.S., Kedia, B.L., Harveston, P.D.E. and Triandis, H.C. (2002), ‘‘Cultural variations in the cross-border transfer of organizational knowledge: an integrative framework’’, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 27 No. 2, pp. 204-21.

Brown, J.S. (1998), ‘‘Internet technology in support of the concept of the communities of practice: the case of Xerox’’,Accounting, Management and Information Technologies, Vol. 8, pp. 227-36.

Brusco, S. and Righi, E. (1989), ‘‘Local government, industrial policy and social consensus: the case of Modena (Italy)’’,Economy and Society, Vol. 18, pp. 405-24.

Burt, R. (1992),Structural Holes, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Chandler, A.D. (1977),The Visible Hand, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Chua, A. (2002), ‘‘The influence of social interaction on knowledge creation’’,Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 3 No. 4, pp. 375-92.

Cook, S.D.N. and Brown, J.S. (1999), ‘‘Bridging epistemologies: the generative dance between organizational knowledge and organizational knowing’’, Organization Science, Vol. 10 No. 4, pp. 381-400.

Corno, F., Reinmoeller, P. and Nonaka, I. (1999), ‘‘Knowledge creation within industrial systems’’,Journal of Management and Governance, Vol. 3 No. 4, pp. 379-94.

Dhaliwal, J. and Benbasat, I. (1996), ‘‘The use and effects of knowledge-based system explanations: theoretical foundations and a framework for empirical evaluation’’,Information Systems Research, Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 342-62.

Fayard, P. (2004),Comprendre et appliquer Sun Tzu: La pense´e strate´gique chinoise, Dunod, Paris.

Frey, R.S. (2001), ‘‘Knowledge management, proposal development, and small businesses’’, The Journal of Management Development, Vol. 20 No. 1, pp. 38-54.

George, J.F., Iacono, S. and Kling, R. (1995), ‘‘Learning in context: extensively computerized work groups as communities of practice’’,Accounting, Management and Information Technologies, Vol. 5 No. 3, pp. 185-202.

Granovetter, M.S. (1973), ‘‘The strength of weak ties’’,American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 78 No. 6, pp. 1360-80.

Grant, R.M. (1996), ‘‘Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm’’,Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 17, pp. 109-22.

Gregor, S. and Benbasat, I. (1999), ‘‘Explanations form intelligent systems: theoretical foundations and implications for practice’’,MIS Quarterly, Vol. 23 No. 4, pp. 497-530.

Human, S.E. and Provan, K.G. (1997), ‘‘An emergent theory of structure and outcomes in small-firm strategic manufacturing network’’,Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 40 No. 2, pp. 368-403.

Inzerilli, G. (1990), ‘‘The Italian alternative: flexible organization and social management’’,International Studies of Management & Organization, Vol. 20 No. 4, pp. 6-21.

Kogut, B. and Zander, U. (1992), ‘‘Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology’’,Organisation Science, Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 383-97.

Lee, S. and O’Keefe, R.M. (1996), ‘‘An experimental investigation into the process of knowledge based systems development’’,European Journal of Information Systems, Vol. 5, pp. 233-49.

Lim, D. and Klobas, J. (2000), ‘‘Knowledge management in small enterprises’’,The Electronic Library, Vol. 18 No. 6, pp. 420-33.

Lorenzoni, G. and Ornati, O. (1988), ‘‘Constellations of firms and new ventures’’,Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 41-57.

McAdam, R. and Reid, R. (2001), ‘‘SME and large organisation perceptions of knowledge management: comparisons and contrasts’’,Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 5 No. 3, pp. 231-41.

Marcon, M. and Moinet, N. (2000),La strate´gie-re´seau, E´ditions Ze´ro Heure, Paris.

Michelis, G. (2001), ‘‘Cooperation and knowledge creation’’, in Nonaka, I. and Nishiguchi, T. (Eds),

Knowledge Emergence, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp. 124-44.

Muthusamy, S. and White, M. (2005), ‘‘Learning and knowledge transfer in strategic alliances: a social exchange view’’,Organization Studies, Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 415-41.

Nelson, R.R. (1991), ‘‘Why do firms differ, and how does it matter?’’,Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 12 No. 8, pp. 61-74.

Nissen, M.E. (2000), ‘‘An experiment to assess the performance of a redesign knowledge system’’,

Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 17, pp. 25-44.

Nonaka, I. and Nishiguchi, T. (2001),Knowledge Emergence, Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995),The Knowledge-creating Company, Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

Nonaka, I., Toyama, R. and Konno, N. (2002), ‘‘SECI, ba and leadership: a unified model of dynamic knowledge creation’’, in Little, S., Quintas, P. and Ray, T. (Eds), Managing Knowledge an Essential Reader, Sage, London, pp. 41-67.

Nonaka, I., von Krogh, G. and Voelpel, S. (2006), ‘‘Organizational knowledge creation theory: evolutionary paths and future advances’’,Organization Studies, Vol. 27 No. 8, pp. 1179-208.

Oliver, A.L. and Ebers, M. (1998), ‘‘Networking network studies: an analysis of conceptual configurations in the study of inter-organizational relationships’’,Organization Studies, Vol. 19 No. 4, pp. 549-83.

Perrow, C. (1992), ‘‘Small-firm networks’’, in Nohria, N. and Eccles, R. (Eds), Networks and Organizations: Structure, Form and Action, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA, pp. 445-70.

Polanyi, M. (1966),The Tacit Dimension, Doubleday and Co., New York, NY.

Powell, W.W. (1998), ‘‘Learning from collaboration: knowledge and networks in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries’’,California Management Review, Vol. 40 No. 3, pp. 228-40.

Prahalad, C.K. and Hamel, G. (1990), ‘‘The core competence of the corporation’’,Harvard Business Review, Vol. 68 No. 3, pp. 79-91.

Ruef, M. (2002), ‘‘Strong ties, weak ties and islands: structural and cultural predictors of organizational innovation’’,Industrial and Corporate Change., Vol. 11 No. 3, pp. 427-49.

Richardson, G.B. (1972), ‘‘The organization of industry’’,Economic Journal, Vol. 82, pp. 883-96.

Robey, D. and Sahay, S. (1996), ‘‘Transforming work through information technology: a comparative case study of GIS in County Government’’,Information Systems Research, Vol. 7 No. 4, pp. 93-110.

Rosenfeld, S.A. (1997), ‘‘Bringing business clusters into the mainstream of economic development’’,

European Planning Studies, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 3-23.

Sabel, C. (1991), ‘‘Moebius-strip organizations and open labor markets: some consequences of the reintegration of conception and execution in a volatile economy’’, in Coleman, J. and Bourdieu, P. (Eds),

Social Theory for a Changing Society, Westview Press, Boulder, CO, pp. 23-63.

Saxenian, A. (1994),Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Schultze, U. and Boland, R.J. Jr. (2000), ‘‘Knowledge management technology and the reproduction of knowledge work practices’’,Journal of Strategic Information Systems, Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 193-212.

Scott, J.E. (2000), ‘‘Facilitating organizational learning with information technology’’, Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 81-113.

Soo, C., Devinney, T. and Midgley, A. (2002), ‘‘Knowledge management: philosophy, processes and pitfalls’’,California Management Review, Vol. 44 No. 4, pp. 129-50.

Sparrow, J. (2001), ‘‘Knowledge management in small firms’’,Knowledge and Process Management, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 3-16.

Spencer, J.W. (2003), ‘‘Firms’ knowledge-sharing strategies in the global innovation system: empirical evidence from the flat panel display industry’’,Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 24 No. 3, pp. 217-33.

Stenmark, D. (2001), ‘‘Leveraging tacit organizational knowledge’’,Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 9-24.

Suchman, L. (1987),Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-machine Communication, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY.

Teece, D.J., Rumelt, R., Dosi, G. and Winter, S. (1994), ‘‘Understanding corporate coherence: theory and evidence’’,Journal Economic Behavior, Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. 1-30.

Tsai, W. (2002), ‘‘Social structure of ‘co-opetition’ within a multiunit organization: coordination, competition, and intra-organizational knowledge sharing’’, Organization Science, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 179-90.

uit Beijerse, R.P. (2000), ‘‘Knowledge management in small and medium-sized companies: knowledge management for entrepreneurs’’,Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 4 No. 2, pp. 162-79.

Wacheux, F. (1996),Me´thodes qualitatives et recherche en gestion, Economica, Paris.

Walker, G., Kogut, B. and Shan, W. (1997), ‘‘Social capital, structural holes and the formation of an industry network’’,Organization Science, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp. 109-26.

Wiklund, J. and Shepherd, D. (2003), ‘‘Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses’’,Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 24 No. 13, pp. 1307-14.

Wong, K.Y. and Aspinwall, E. (2004), ‘‘Characterizing knowledge management in the small business environment’’,Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 8 No. 3, pp. 44-61.

Yin, R.K. (1989),Case Study Research: Design and Methods, Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

Zhao, J.L., Kumar, A. and Stohr, E.A. (2001), ‘‘Workflow-centric information distribution through e-mail’’,

Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 17, pp. 45-72.

About the authors

Alsones Balestrin is a Professor and researcher at the School of Management of the University of Vale do Rio dos Sinos. Doctor in Business Administration at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. Research interests include inter-organizational networks, and knowledge creation. Alsones Balestrin is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: abalestrin@unisinos.br

Lilia Maria Vargas is a Professor and researcher at the School of Management of UFRGS. Docteur in Business Administration at the University of Pierre Mende`s France, Grenoble (France). Research interests include information and technological innovation management, cooperation networks and information technology management.

Pierre Fayard is a Professor at the Communication and New Technologies Institute of the Universite´ de Poitiers, visiting professor at the universities Pompeu Fabra (Barcelone), Salamanca (Spain), Caxias do Sul and Umesp de Sa˜o Paulo (Brazil). Docteur in Information and Comunication Sciences by the Universite´ Grenoble III – France. General director of the CenDoTeC – Brazilian-French Center of Techno-Scientific Documentation. Research interests include: organizational knowledge creation and strategy culture.