FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS

ESCOLA BRASILEIRA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO PÚBLICA E DE EMPRESAS MESTRADO EM ADMINISTRAÇÃO

NICHES OF GRASSROOTS INNOVATION IN WASTE

MANAGEMENT: THE CASE OF SUSTAINABLE

INITIATIVES IN THE FAVELAS OF RIO DE

JANEIRO

LAURA MAZZOLA

Rio de Janeiro - 2019DISSERTAÇÃO APRESENTADA À ESCOLA BRASILEIRA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO PÚBLICA E DE EMPRESAS PARA OBTENÇÃO DO TÍTULO DE MESTRE

Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP)

Ficha catalográfica elaborada pelo Sistema de Bibliotecas/FGV

Mazzola, Laura

Niches of grassroots innovation in waste management : the case of sustainable initiatives in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro / Laura Mazzola. – 2019.

65 f.

Dissertação (mestrado) - Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas, Centro de Formação Acadêmica e Pesquisa.

Orientador: José Antônio Puppim de Oliveira. Inclui bibliografia.

1. Resíduos sólidos - Eliminação. 2. Política ambiental – Rio de Janeiro (RJ). 3. Educação ambiental. I. Oliveira, José Antônio Puppim de. II. Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas. Centro de Formação Acadêmica e Pesquisa. III. Título.

CDD – 628.445

Acknowledgments

Studying and researching at EBAPE has been an amazing educational experience. I am deeply grateful to all the people that contributed to this life-changing journey.

It has been a privilege to take classes, interact, research, and be mentored by EBAPE’s faculty members. I thank them for generously sharing their expertise, insights, advise, and for their immense availability.

I thank my supervisor, Prof. Puppim, for presenting me the world of sustainability and for putting me into contact with people and realities critical for this work. I thank him for allowing me to conduct an extremely enriching and rewarding project.

I thank Michel for his invaluable contribution to this research work, and for helping me to build one step at the time my understanding of the world of waste management.

I thank the wonderful people from the M.Sc. and Ph.D. courses I had the privilege to study with. I learned a lot from all of them and they will always have a place into my heart.

I thank my families around the world. I thank my Brazilian family for their comprehension and interest in this work. I thank my parents and siblings in Italy for their loving support. I cannot wait to see them and meeting my niece.

Abstract

This dissertation aims at understanding which factors may stimulate a transition to an integrated management of municipal solid waste at the national level in Brazil and the local level in Rio de Janeiro. At the national level, it explores how the quantity of recyclable materials recovered by municipalities correlates with its formal structure, such as existing municipal policies, institutional arrangements, administrative variables, and geographical factors. In Rio de Janeiro, this research analyzes the management of solid urban waste as a socio-technical system and aims at investigating niches of innovation that may challenge the mainstream management and drive the waste system to sustainability. Both the national statistical analysis and the local qualitative study reveal, on the one hand, the critical role of environmental education, on the other, the limitation of policy instruments and formal institutions. The statistical analysis demonstrates that having by law the main municipal policy instruments does not guarantee that municipalities perform better in recycling. Moreover, the existence of local policies appeared to be less relevant than the location and size of the municipal population. The policy variables statistically more relevant for explaining the recuperation of recyclable materials turned out to be the environmental education initiatives and climate change actions. After mapping the actors playing a role in the waste governance in Rio de Janeiro, the qualitative study focused on grassroots innovations in waste management in favelas. Environmental education is at the heart of these initiatives that sprout in communities often characterized by violence and lack of public policies. By presenting some of these initiatives, their origins, challenges, survival strategies, and the potential benefits of the interaction with the public and private sectors, this investigation sheds light on the potential of these niches to affect the regime of the waste management of the city. Taken all together, the results suggest that cultivating the environmental awareness of the population and getting their collaboration and engagement in enacting sustainable waste management practices could be at least as critical as passing the appropriate piece of legislation.

Resumo

Esta dissertação tem como objetivo compreender quais fatores podem estimular a transição para uma gestão integrada de resíduos sólidos urbanos em nível nacional no Brasil e no nível local no Rio de Janeiro. No nível nacional, explora-se como a quantidade de materiais recicláveis recuperados pelos municípios se correlacionam com sua estrutura formal, como políticas municipais existentes, arranjos institucionais, variáveis administrativas e fatores geográficos. No Rio de Janeiro, descreve-se a gestão de resíduos sólidos urbanos (RSU) como um sistema sociotécnico e busca-se investigar nichos de inovação que possam desafiar a gestão convencional e conduzir o sistema de resíduos à sustentabilidade. Tanto a análise estatística nacional como o estudo qualitativo local revelam, por um lado, o papel crítico da educação ambiental, por outro, a limitação de instrumentos de políticas e instituições formais. A análise estatística demonstra que ter em lei os principais instrumentos municipais de política ambiental não garante que os municípios tenham um melhor desempenho na reciclagem. Inclusive a existência de políticas ambientais locais se demonstrou menos relevante que a localização e a população da cidade. As variáveis de políticas públicas mais relevantes estatisticamente para explicar a recuperação de material reciclável foram as iniciativas específicas em educação ambiental e mudança climática. Depois de mapear os atores que desempenham um papel na governança dos resíduos do Rio de Janeiro, o estudo qualitativo concentrou-se em inovações de base na gestão de resíduos em favelas. A educação ambiental está no centro dessas iniciativas que emergem em comunidades, que são muitas vezes vítimas de violência e de ausência do poder público. Apresentando algumas dessas iniciativas, suas origens, desafios, estratégias de sobrevivência e os potenciais benefícios da interação com os setores público e privado, esta pesquisa lança luz sobre o potencial desses nichos informais para afetar o regime de gerenciamento de resíduos da cidade. Em conjunto, esses resultados sugerem que cultivar a conscientização ambiental da população e conseguir sua colaboração e engajamento na implementação de práticas sustentáveis de gerenciamento de resíduos pode ser, no mínimo, tão crítico quanto adotar as políticas adequadas.

Contents

1. Introduction ... 5

2. Methodology ... 7

3. Socio-technical transitions... 8

3.1. The Multi-Level Perspective ... 9

3.2. Sustainability transition in waste management ... 11

3.3. Sustainability transition in developing countries ... 13

3.4. Grassroots innovation movements ... 14

4. Waste Management in Brazil... 16

4.1. Data on Waste in Brazil... 16

4.2. Legal framework ... 19

4.3. Quantitative analysis: institutional arrangements and recycling ... 21

4.3.1. Modeling the probability of recuperating any recyclable quantity ... 24

4.3.2. Modeling the quantity recovered by the cities that recuperate ... 28

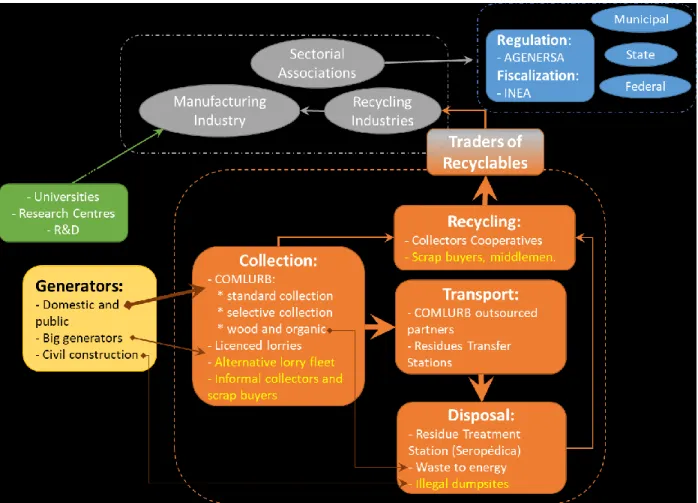

5. The Waste Management system of Rio de Janeiro... 32

5.1. Mapping the socio-technical regime ... 33

5.1.1. Formal waste management infrastructure ... 35

5.1.2. Recycling system... 37

5.1.3. Informal waste management infrastructure ... 38

5.1.4. Sectorial policy ... 39

5.2. Elements of the landscape ... 40

5.3. Niches of grassroots innovation ... 42

5.3.1. Mapping niches types ... 44

5.3.2. Origins of niches ... 47

5.3.3. Challenges and support: the role of grassroots networks ... 48

5.3.4. Integration with the public power and policies for consolidation ... 51

6. Contribution and limitations ... 55

7. Conclusion ... 57

1. Introduction

Despite implementing a sound waste system can help deliver, directly or indirectly, all 17 of the sustainable development goals, waste management has often taken a minor role in the discussions about a world transition to sustainability. Two billion people worldwide have no garbage collection, and three billions have an inadequate waste system (Wilson et al., 2015). Eight million tons of plastic enter the ocean every year, 80% of them comes from land-based sources, three-fourths of which are uncollected garbage (Jambeck et al., 2015). At the same time, uncollected or ill-managed waste presents a wide range of negative impacts on people’s health (especially children’s), the environment, and the economy. Waste constitutes a place for micro-organisms, vermins, and mosquitos to spread and breed; it causes pollution of land, water, and air; it reinforces poor economic development; it inhibits tourism; it may harm livestock and aggravate flood incidents by blocking drains. The United Nations calculates that the cost to society of not managing waste – considering the health, economic, and environmental impacts – is 5 to 10 times higher than implementing a simple waste management system (Wilson et al., 2015).

In a big part of the world, waste management top-down policies are either not in place or not working. Some national and international NGOs are attempting at filling this gap by disseminating waste management community practices in places that do not have a formal system. They defend that bottom-up solutions can mitigate, at least to some extent, the risks associated with waste, while generating jobs, and improving the morale and proud of the community (Lenkiewicz & Webster, 2017). The global plastic waste exporting by developed counties intensifies the problem of waste management in developing countries (Clapp, 2001; Walker, 2018).

The Brazilian National Policy of Solid Residues (Law 12.305/2010), considered a modern piece of environmental legislation, has been in place since 2010 (Dias & Teodosio, 2010). One of its primary goals was the shutdown of all dumpsite and inadequate landfill by 2014. Nevertheless, according to data of 2017, still, more than 40% of the waste produced does not go to the appropriate destination, with 18% of rejects abandoned in open dumps, 22.9% disposed of in landfills not endowed with a sludge treatment system. Besides, 9% of all waste generated goes uncollected (Abrelpe, 2018).

Even municipalities that dispose of their residues appropriately struggle to enact sustainable waste management practices established in the national policy, such as recycling. Data on recycling in Brazil are insufficient and often contradictory. According to Brazilian Association of Enterprises

6

of Public Cleaning and Special Residues - ABRELPE (Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Limpeza Pública e Resíduos Especiais) -, 60% of Brazilian municipalities have some recycling initiative. Based on the data of SNIS 2017, the average rate of recuperation of recyclable material is 2.1%. This rate includes the material recuperated by the municipality and the formal actors working in partnership with it. However, it does not account for quantities of materials recuperated by informal agents working on the recuperation of recyclable materials with value in the local material market (SNIS, 2019).

While the recycling by the formal public municipal system fails to meet expectations, there exists an informal parallel system that relies on the work of hundreds of thousands of autonomous street collectors feeding a value chain that eventually intersect the formal private recycling industry. Besides, there are local formal or informal community actors organizing to enact sustainable waste management practices (actions aiming at the non-generation or reduction, reuse and repurpose, and recycling of waste) without waiting for the intervention of the state, seeking profits or not (Nas and Jaffe 2004; Scheinberg et al. 2010).

This dissertation aims at understanding which factors may drive sustainable waste management at the national level in Brazil and the local level in Rio. At the Brazilian level, I focus on the formal recycling by public institutions and their municipal partners. I use the only – and not yet public – survey on municipal organs for environmental management realized in Brazil, to investigate what institutional factors and municipal arrangements could drive recuperation of recyclable material in cities. Because such database is cross-sectional, I do not have elements to infer causality. Nevertheless, our correlation analysis gives us insights into which variables are significant and how critical institutional arrangements are for the occurrence of formal recycling.

The formal recuperation rate of recyclable materials and composting in Rio de Janeiro is just a few percentage points, suggesting that the mainstream management is not sustainable and that there may be low hanging fruits to drive the waste management system toward sustainability. Therefore, I aim at studying the actors engaged in sustainable waste management, the initiatives put forward, how they originated, the challenges faced, and in which way they could be promoted. I look at how municipal public arrangements, private enterprises, informal actors, and community-based initiatives interact and play a role in the governance of waste in the city, by describing the waste management as a socio-technical system. I conclude that innovative initiatives in communities typically characterized by the absence of the state and by a scarcity of resources may

provide a road map for the implementation of solutions that are readily available on the territory but have not yet been fully harnessed.

After discussing the methodology of our work in Section 2, I introduce the socio-technical transitions, the multi-level perspective, which is the heuristic model used to describe them, and their specific features for waste management systems and the case of developing countries, in Section 3. In Section 4, I touch on the grassroots innovation movement literature. In Section 5, I discuss data on waste management and the recycling industry in Brazil, the legal framework and present a statistical analysis of the rate of recuperation of recyclable material across Brazilian municipalities as a function of geographical factors, local institutional and administrative arrangements. Section 6 maps the main actors (formal and informal) and elements of the socio-technical waste management system in Rio de Janeiro, discussing sustainable initiatives in favelas as niches of innovation, and reflect on strategies to harness the potential of these niches. In Section 7, I emphasize the contribution of this work to the literature and focus on its limitations. I conclude summing up and reflecting on the policy network paradigm in Section 8.

2. Methodology

This study employs two different methods. First, I use statistical analysis to study the rate of recuperation of recyclable materials by the municipal solid waste management system (MSWMS), and its relationship with local environmental management institutions and policies. I employ a sample of 477 municipalities derived from cross-referencing two databases. The first database is the Diagnosis of Municipal Solid Waste Management of 2016 from the National System of Information about Sanitation (SNIS 2016), the second is the National Census of the Municipal Organs for Environmental Management conducted by The National Association of Environmental Municipal Organizations, ANAMMA, which has not been made public yet. Besides a descriptive statistical analysis of the urban rate of recuperation of recyclable materials, I test the explaining power of different institutional arrangements, environmental education initiatives, and compliance with policy requirements, among the others. Because the dependent variable is a censored variable, I use a two-step model consisting of probit and truncated regression.

In sequence, I analyze different types of documents: national and local policies; reports from governmental bodies, sectorial industry associations, universities, NGOs and civil-society associations; and press releases and newspaper coverage. I describe the agents involved in the

8

MSW management, together with the ensemble of material and immaterial elements fulfilling this societal function, as a socio-technical system. I employ a multi-level perspective to distinguish between the agents that determine the overall functioning of the waste system, the relevant contextual factors that are not under the direct control of such agents, and niches of innovation of sustainable community-based practices in places where the mainstream system is often dysfunctional, such as Rio de Janeiro’s favelas.

I performed six fieldwork visits, four structured, and nine semi-structured interviews. The interviewees are agents of the formal and informal MSW management system in Rio de Janeiro, leaders of community-based initiatives, grassroots ecopreneurs, and members of nongovernmental organizations (NGO). To guide our qualitative data collection, I employed a database of community-based initiatives of the 2017 Sustainable Favela Network survey performed by the NGO Catalytic Community – a mapping of more than a hundred sustainable actions in sustainability and social resilience. I prepared a questionnaire for all structured interviews, asked and were granted permission to record, and transcribed them. I produced notes during field visits, including reports of seminars and unstructured interviews.

3. Socio-technical transitions

Socio-technical transitions, or system innovation, are changes in the way a societal function is provided (Geels, 2002, 2004, 2005a). When the change is toward a more sustainable system, they are called sustainable transitions (Geels, 2012; Geels, Sovacool, Schwanen, Sorrell, & Willett, 2017; Setzer, 2011). The starting point of the framework is that radical transformations in societal functions do not involve technological changes only, but they are structural changes in socio-technical systems. Such systems “comprise a cluster of elements, including technology, regulations, user practices and markets, cultural meanings, infrastructure, maintenance networks, and supply networks” (Elzen, Geels, & Green, 2004). The term socio-technical symbolizes the entanglement between technology, whose functioning depends on the characteristics of the users (their competencies, preferences, and values), and the users’ context, which is in turn shaped by infrastructures and regulations. System innovation brings together two bodies of literature: on the one hand, the evolutionary economics and innovation system studies, both focusing on the generation of technological innovations and the supply-side; on the other, science and technology studies, and cultural studies, which investigate the demand-side and how users tame new

technologies into their symbolic, cognitive and practical contexts. I describe the waste management system in Rio de Janeiro as a socio-technical system.

Socio-technical transitions are multi-actor processes, quite sporadic because existing socio-technical systems are dynamically stable (Geels, 2005b). Their stability results by a degree of alignment among different stakeholders - each with their resources, values, preferences, and strategies - engaging in different ways among them and with the system. While tensions and conflicts may be part of the actors’ interaction, if they become too pressing the socio-technical system may lose its stability and take one of various paths of change, as discussed by the research on path dependence and lock-in (Kemp, Schot, & Hoogma, 2007; Seto et al., 2016).

3.1. The Multi-Level Perspective

The multi-level perspective is a general analytical and heuristic framework for making sense of the dynamics of sociotechnical systems. Developed with the ambition of combining different theoretical traditions, it distinguishes three levels of a socio-technical system: the niches, the regime, and the landscape (Geels, 2002). These three levels are not to be considered as ontological, but instrumental to the description of a complex system (Geels, 2010). Each level is conceived a socio-technical configuration by itself, characterized by different size and degree of stability. For the sake of illustration, I report in Figure 1 the multi-level perspective of the socio-technical system for land-based road transportation elaborated (Geels, 2002).

Niches provide locations protected from standard market mechanisms, characterized by different selection criteria, and propitious for radical (technological) innovations to sprout. The main actors at the niche level are entrepreneurs and innovators, who are committed, have high expectations, and are willing to take risks. The protection arises not only from the commitment of the actors but also may come from public subsidies. The actors operate with little structuration of their activities in a context of uncertainty and flexibility, within small and unstable social networks. Niches are cradles of experimentation and learning processes (Campbell & Sallis, 2013; Kemp et al., 2007).

Geels defines the socio-technical regime as a “semi-coherent set of rules carried by different social groups” (Elzen et al., 2004). Different stakeholders – such as technology producers, users, policymakers, scientists – operate in the regime within a stable set of markets, products, regulations, and infrastructures. Their activities are structured and – to some extent – aligned,

10

which is what creates stability and lock-in. Different mechanisms may drive lock-in, they are cognitive, such as the technology producers do not develop outside their focus; regulative, such as rules favoring existing technologies; or normative, like sunk investments and the difficulty to adapt to new technical systems (Grin, Rotmans, & Schot, 2010). Innovation does occur, but it is incremental and cumulative. The socio-technical regime is the extensive and relatively stable network of the interacting and mutually dependent groups each evolving along their trajectory. Diverging trajectories may give rise to tensions, that may be “compensated” within the system, or that may lead to mal-adjustment, affecting the stability of the regime, and triggering windows of opportunity for change (Geels, 2004).

The landscape is an external context going beyond the direct influence of actors at the niche and the regime levels. The term landscape invokes the materiality of spatial arrangements and other aspects of society. It consists of deep structural factors that happen on different time scales: very slowly, such as changes in the climate; long-term, like economic development local or global; or rapid, as in the case of financial shocks and breakout of diseases (Geels, 2005a; Morone, Lopolito, Anguilano, Sica, & Tartiu, 2016).

Figure 1: Multi-level perspective of the socio-technical system for land-based road transportation (on the left) and social actors reproducing the system on the right (on the right) in (Geels, 2002).

Within the multi-level framework, transitions occur through the co-evolutionary interplay of processes at the niche, regime, and landscape level. There is an ample body of literature discussing how different interactions among these levels lead to transitions (Elzen et al., 2004; Grin et al., 2010). I mention that often “downward” pressure on the regime – arising, for example, from changes in the societal context, social production and consumption patterns – allies with “upwards”

pressure by rivaling socio-technical configurations incubated in niches, in this way threatening the stability of the regime and possibly inducing changes.

3.2. Sustainability transition in waste management

Many cities around the world are taking measures to modify their internal functioning in a sustainable direction (Hodson & Marvin, 2010). Participation in global city networks, building capacities, developing and sharing sustainable solutions, signal a political willingness by government and policymakers to steer the evolution of their urban societal services purposefully. Waste management systems is an urban socio-technical system crucial to the transition to sustainability, not only for public health and environment risks associated but also for its potential for mitigation and adaptation to climate change. Waste contains a relatively high fraction of carbon, which, when oxidized by micro-organisms or by thermal processes, produces carbon dioxide and methane, both highly active greenhouse gases, with the latter at least 21 times more potent than the former. Estimates say that 5% of all greenhouse gases emissions worldwide (about 1.6 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2016) come from waste (World Bank, 2018).

Given that 70% of global municipal solid waste goes to landfill, and the disposal is the process generating the most emissions, the implementation of a sustainable waste management system represents an opportunity for cutting down GHG emissions. Sustainable waste management is also an essential climate change adaptation measure especially in developing countries, where ill-managed waste increases the risks of a health emergency, spreading epidemic diseases, and environmental disasters as in the case of heavy rains inducing trash-slides, and flood provoked by waste clogging drains and affecting stream flows (Koop & van Leeuwen, 2017).

Despite the relevance of waste management for the transition to sustainability, a recent literature review shows that the socio-technical perspective has been seldom adopted to describe waste management systems (Andersson et al., 2019). Up to 2017, only seven articles in the waste management field mentioned the multi-level perspective of socio-technical transition (to put things in perspective, consider that a seminal paper on the multi-level perspective (Geels, 2002) has been cited more than 4,000 times). In this section, I review a few papers from this literature.

Uyarra and Gee (2013) discuss how Great Manchester underwent a sustainability transition in waste management urban infrastructure “from a relatively simple landfill model to a highly complex, multi-technology waste solution based on intensive recycling and composting, and

12

sustainable energy usage” (Uyarra & Gee, 2013). In the year 2000, most of Manchester waste went to landfill and the municipality recycled only 3% of its waste. The abundance of landfill space and the policies putting recycling and composting as equally desirable as energy recovery through incineration had dominated the waste management scene at the national level. The process of liberalization of the waste market accompanied by a tight regulatory framework increasing landfill disposal costs pressured local governments to find more sustainable solutions for their waste disposal. While other municipalities opted for the easier-to-implement incineration solutions, the firm opposition by Manchester population to incineration plants opened a window of opportunity for a more structural change. Manchester decided to capitalize on successful community recycling experiences, public consultation, and restructuring of the waste utility authority (Uyarra & Gee, 2013). The paper explores the technological, social, political, and institutional dimension of the transformation and focuses on the actors and processes that enabled the transition.

The study by Corvellec et al. (Corvellec, Campos, & Zapata, 2013) tackles the question of path-dependence and lock-in of waste management infrastructure in Göteborg metropolitan area. Once considered a pioneer sustainable waste management solution, waste incineration has come in the way of delivering alternative and more sustainable waste handling in Göteborg. The authors detail how the four rationales of lock-in theorized by Unruh (institutional, technical, cultural, and material) apply to the case of Göteborg and are even of relevance for other countries (Seto et al., 2016). The authors explain how acknowledging the system lock-in and understanding the lock-in rationales is the first step for terminating path-dependence and unlocking the urban infrastructure. Morone et al. investigate the main stakeholders operating in the landscape of an municipal waste management socio-technical system and the pressure types they may exert on the regime incumbents (Morone et al., 2016). The authors focus on international pressure activities and distinguish local and global actors exerting pressure across political and economic channels. In the case of waste management, the economic channel corresponds to economic benefits, subsidies, and financial cuts pushing municipalities to, for example, implement a separate waste collection system. The political channel consists of all activities undertaken by local and global institutions aiming at influencing decisions in waste management. The authors apply their theoretical framework to the case of the province of Foggia, Italy, which transitioned from a recycling rate close to zero to 60% in less than seven years.

3.3. Sustainability transition in developing countries

It is not a coincidence that all the examples of transitions in waste management presented above are from metropolitan areas in developed countries. Although the socio-technical framework has been used mainly to explain transitions in developed countries, there is a smaller but steadily growing literature producing empirical analyses of transitions, discussing the limits of the socio-technical framework and the conceptual extensions needed for its application in developing countries. A recent systematic review of 115 publications, published in the years 2005-2016, employing the multilevel perspective identify features of sustainability transitions in developing countries, differences with developed countries and put forward policy implications (Wieczorek, Raven, Berkhout, & Wieczorek, 2015). In the following, I mention a few distinctive features that are of relevance to this study.

A crucial factor to consider is dysfunctionality and lack of uniformity of socio-technical regimes. Furlong argues that socio-technical transitions occurring as a total displacement from one regime to another may not be the norm in developing countries, and instead coexistence of a diversity of modes fulfilling the same societal functions may be more common (Furlong, 2014). People in the developing world, living a constant state of disrepair, characterized by intermittent and poor-quality service, would develop alternative strategies – even clandestine – to improve the reliability of essential services. If it seems evident that the malfunctioning or absence of a system constitutes a window of opportunity for change, the habit and norms consistent with these dysfunctional systems may be stable. This observation leads to the question of how to frame a transition in absence or dysfunctionality of the socio-technical system. Wieczorek’s policy recommendation is to "consider transformative policy based on filling ‘unserved spaces’ with sustainable alternatives and providing a stable institutional framework that facilitates social entrepreneurship” (Wieczorek, 2018).

The lack of stable institutions and the high levels of uncertainty about markets and social networks are common in developing countries. Ramos-Mejia et al. (Ramos-Mejía, Franco-Garcia, & Jauregui-Becker, 2018) discuss how different institutional settings influence the development of innovation, adopting the institutional types by Wood and Gough (Wood & Gough, 2006). They distinguish three types of settings: welfare, informal security, and insecurity, characterized by different dominant modes of production, social relationships and policies, political mobilization, and source of livelihood. A key aspect pervading the informal security and insecurity settings is

14

the relevance of informal norms and markets. As Ramos-Mejía et al. say, “both formal and informal institutions in the developing world are contested and personalized at various extents, undermining the well-being of many and strengthening the privileges of a few, and therefore, reproducing patterns of social exclusion.” Markets are often informal and conjoin into formal ones. People achieve their basic societal functions through individual survival strategies. Ramos-Mejía et al. present a characterization of socio-technical systems in these institutional setting across all levels. To account for the heterogeneity of the institutional setting, instead of considering a mixture of types, they borrow the concept of “pockets” – the presence of an institutional type within a different institutional setting – from the geography of poverty literature (Alkire, Roche, & Sumner, 2013).

Transnational linkages are particularly relevant for socio-technical systems in developing countries. Wieczorek defines transnational linkages as cross-border relationships and interactions that can complement local, regional, and national capability of a socio-technical niche (Wieczorek et al., 2015). Such relationships may be technical with foreign experts or firms supplying technologies, and financial, through international donors. Hansen and Nygaard have analyzed the palm oil biomass waste-to-energy niche in Malaysia and showed that the intervention of donors, while often protects against market selection pressures, does not always promote the development of radical innovation (Hansen & Nygaard, 2013). These results connect with the discussion on the role of community and the importance of engagement of local social actor in the management of transitions (Campbell & Sallis, 2013).

The points emphasized above are of relevance for the construction of the socio-technical waste management system in Rio de Janeiro considering its dysfunctionality across various, and especially low-income, areas of the city.

3.4. Grassroots innovation movements

Grassroots innovations are a type of socio-technical niche developing bottom-up, socially just, and environmentally sustainable innovation. The solutions to social and environmental problems they pursue put at the center the indigenous points of view and needs, harness alternative forms of knowledge and ultimately aim at the inclusion of the local community. Such inclusion may occur as on outcome, namely as products or services, not provided by other markets, customized to the needs of the community; may occur as a process, by actively engaging the community in the design process of the technology; or may be structural and enable communities

to affect policy-making and institutions (Smith, Fressoli, & Thomas, 2014). Grassroots innovations differ from mainstream innovations in motivations and values, as their central objective is allowing communities to exercise control over the innovation process. By being involved, communities strengthen their sense of citizenship, belonging, and degree of social and economic self-determination.

Grassroots innovations are making significant contributions to the green economy and sustainable development (Creech et al., 2014; Sarkar & Pansera, 2017), while receiving attention by international development institutions, as the World Bank and the OECD. Grassroots movements often need support for researching and developing products and technologies, networking, building capacity, and raising finance (Creech et al., 2014), which encourage encounters with mainstream innovations institutions. However, collaborations with NGOs, R&D institutions or universities, and governments programs – despite often essential for the survival and expansion of the movements – hardly take place without challenges.

An example of grassroots innovation movements endorsed by a government is the Social Technology Network (Rede de Tecnologia Social) in Brazil. Social technology is a replicable product, technique or methodology, developed by (or in interaction with) a community and represents an effective solution to social, economic, and environmental demands. The objective of the network is to turn isolated initiatives – ideated, developed and implemented by communities and technology developers (with different degrees of involvement) – into broader public policies and applications on a large scale. (Miranda, Lopez, and Couto Soares 2011). The Award for Social Technology by the Banco do Brasil Foundation, realized since 2001 every two years, is the main instrument of identification and certification of the social technology initiatives. Only legally constituted non-profit institutions may participate in the certification process and the competition to the award. The certified initiatives became part of a database of hundreds of social technologies (Banco de Tecnologias Sociais), containing their information and guidelines for their reapplication, but only a few of them are granted access to funding and supported in scaling up.

The One Million Cisterns Programme is an example of a social technology originated by a network of about 700 grassroots actors and successively scaled up by the government. The innovation aims at tackling the problem of low rainfall in the vast semi-arid region in the Northeast of Brazil. The solution it proposes is a cement-layered cistern of 16,000 liters capacity for collection of rainwater from rooftops, built by users and self-financed with the help of a solidary

16

revolving fund. The Cisterns Programme was adopted as a national policy in 2003, delivering since more than half a million water cisterns, reaffirming the central role played by communities in the cistern construction and the innovation process. The program changed its face in 2011 when the government announced the purchase of 300,000 plastic cisterns. Such a policy change overlooked the key community-empowerment aspect in the program and altered the inclusion of the community from a process to an outcome. The de-contextualization of the policy caused loud protests by the local communities, who feared that the program might be hijacked by political patronage and forced the government to reinstitute the self-built cement cistern (Fressoli & Dias, 2014).

Entrepreneurship can be an allied and a solution for sustainable development. Grassroot entrepreneurs, like grassroots movements, develop socially inclusive innovation while aiming at putting such innovations on the market. Grassroots ecopreneurs are “moved by social and environmental concerns, coming up with simple and eco-friendly solutions in their quest to resolve everyday life problems” (Sarkar & Pansera, 2017). Grassroots movements and ecopreneurs occupy a crucial part of the niches of innovation of waste management in Rio de Janeiro.

4. Waste Management in Brazil

In this section, I introduce the problem of management of solid residues in Brazil. I discuss the limited and contradictory data on waste management and sustainable practices, the national legal framework, and present the results of a quantitative analysis I performed using the public database of the National System of Information on Sanitation, SNIS, and a database that has not yet been made public by The National Association of Environmental Municipal Organs, ANAMMA. I investigate the effect of local institutional environmental structure on municipal recuperation of recyclable material, finding that having all local policies promulgated by law does not guarantee better sustainable performance.

4.1. Data on Waste in Brazil

Data on waste management in Brazil are scarce, incomplete, and often contradictory. The 2017 Diagnosis of Municipal Solid Waste Management (Diagnóstico do Manejo de Resíduos Sólidos Urbanos) by the National System of Information about Sanitation, SNIS, surveys the administration of 3,556 municipalities, representing 146.3 million people or 83.9% of the Brazilian

population, on their management of urban solid residues (SNIS, 2019). The report reveals a quantity of domestic and public residues for the year 2017 of 50.8 million tons in the selected municipalities, which extrapolating to the rest of the country gives 60.6 million tons per year or 166 thousand tons per day. According to the same report, the material recuperated through selective collection amounts to 1.5 million tons per year for the whole country.

The Brazilian Association of Enterprises of Public Cleaning and Special Residues (ABRELPE) estimates almost 20 million tons more waste generated in Brazil in 2017 than SNIS. The Panorama 2017 by ABRELPE reveals that Brazilian people produced 78.4 million tons of urban solid residues in 2017, 91.2% of these were collected; 59.1% of the collected residue (42.3 million tons) was disposed in sanitary landfill, while the rest was disposed inappropriately in dumpsite or controlled landfill, not endowed with appropriate treatment for slurry.

According to ABRELPE, the Southeast region is responsible for the generation of 53% of collected residue and characterized by a lower rate of waste discarded inappropriately (27.6%). On average, each inhabitant of the Southeast region of Brazil generates 1.217 kg of waste per day. The average monthly cost of collection of urban solid residues and urban cleaning in 2017 is R$ 13.43 per ton (Abrelpe, 2018).

The Technical Report of the General Packaging Sector Agreement- Phase 1 (Relatório Técnico do Acordo Setorial de Embalagens em Geral- Fase 1), signed by 23 associations representing more than 3,000 firms including manufacturers of packaging and packaged products, importers, distributors and dealers of packaging and packaged products, gives a more precise picture of the material recovered and recycled (Rezende, Sakamoto, Cardoso, Codazzi, & Silveira, 2017). The report reveals that on average in Brazil in 2017 the following quantities of recyclable materials were generated and recovered: 21,153 tons of plastic per day, 8.2% of which recovered (about 630 thousand tons per year); 21,851 tons of paper and cardboard, 52.3% of which recovered (more than 4 million tons per year); 941 tons of aluminum per day, 87.2% of which recovered (about 300 thousand tons per year). By summing the quantities of plastic, paper, and aluminum above, I find that at least 5 million tons of recyclable material in 2017 were recovered. Such an estimate is more than three times as big as reported by SNIS.

The million tons of recycled material increases if I consider the data of ANAP, the National Association of Paper Dressers (Associação Nacional dos Aparistas de Papel) - estimating that 4.97 million tons of cardboard and paper were recycled corresponding to 66.6% of all paper consumed

18

in Brazil – and the data of the recycled steel and glass (ANAP, 2018). According to Abeaço, The Brazilian Association of Steel Packaging (Associação Brasileira de Embalagem de Aço) about 47% of steel cans are recycled in Brazil corresponding to 200 thousand tons1.

Data on glass is even scarcer than for previous materials: according to CEMPRE, Business Commitment to Recycling (Compromisso Empresarial para Reciclagem), 47% of glass packaging, which is about 470 thousand tons of glass was recycled in 20112. The data presented above shows

an apparent mismatch between the recycling figures estimated by the public and the private sector. One explanation for such a difference may be the invisible hand of the informal sector.

Estimates claim that, in developing countries, at least 15 million people depend on recyclable materials scavenged in waste for their livelihoods in the last decade (Medina, 2008). According to the Demographic Census of 2010, 387 thousand people have in the collection of recyclable materials their main professional activity in Brazil (IBGE, 2010). They are mostly men (68.9%) and black (66%); 25% of them are illiterate; and their average income was R$ 570,00 in 2008, above the minimum salary (Jaquetto Pereira & Lira Goes, 2016).

According to estimates of the Institute of Applied Economics Research (Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada), IPEA, the number of collectors ranges between 400 to 600 thousand. A small part of them works in cooperatives: a research of the National Movement of Collectors of Recyclable Materials (Movimento Nacional dos Catadores de Materiais Recicláveis) estimated that in 2005, cooperatives counted 25 thousand associates. More frequently, collectors are autonomous and informal, work in a context of vulnerability, without the appropriate security equipment, in insalubrious conditions and with increased risk of accidents.

Still, these workers are the backbone of the Brazilian recycling system. Some estimates that 90% of all recyclable material passes through collectors (AVINA, 2012). The mismatch in the numbers provided by the public and private sector indicates that a quantity of materials arrives at the industry through a chain that does not depend on municipality and involves informal actors going well beyond the street collectors.

1 http://abeaco.org.br/central-de-aprendizado/#reciclagem 2 http://cempre.org.br/artigo-publicacao/ficha-tecnica/id/6/vidro

4.2. Legal framework

In Brazil, the responsibility to manage the urban solid residues and urban cleaning besides sanitation services belongs to the municipalities. The preoccupation with waste collection, transport, and disposal is as old as Law 2.312 of 1954 (Brasil, 1954) that institutes the National Health Code (Código Nacional da Saúde). Law 6.938 of 1981 (Brasil, 1981) that arrange the Environmental National Policy (Política Nacional do Meio Ambiente) declares the polluting potential of solid residues and sewage. The attention to waste management becomes stronger with Rio 1992 and the elaboration of Agenda 21.

Another legal milestone is Law 9.605 of 1998 (Brasil, 1998), or the Law of Environmental Crimes, which criminalizes disposing of solid residues in a way that causes damage to human health, animal mortality or plant die out. More recently, three federal laws have set the regulatory framework for the management of waste in Brazil: Law 11.107 of 2005 (Brasil, 2005) Law of Public Consortia (Lei de Consôrcios Públicos); Law 11.445 of 2007 (Brasil, 2007) of Law of National Guidelines for Basic Sanitation (Lei de Diretrizes Nacionais para Saneamento Básico); and Law 12.305 of 2010 (Brasil, 2010) instituting National Policy of Solid Residues (Política Nacional de Resíduos Sólidos).

The Law of National Guidelines for Basic Sanitation aspires at universalizing the access to basic sanitation in Brazil. It establishes that the service of public cleaning and management of solid residues consists of: the collection, trans-shipment, and transport of solid residues composed of domestic solid waste and urban cleaning waste; and the sorting for re-utilization or recycling, the treatment, including the composting and the final disposal of such residues. It also includes sweeping, weeding and pruning of trees in public roads and public places and other possible services pertinent to urban public cleaning.

The National Policy of Solid Residues (PNRS) establishes the principles, objectives, instruments, and the guidelines relative to the integrated management of solid residues and the responsibility of the generators and the public power. The PNRS aims at the eradication of dumpsites and final destination of solid residues to sanitary landfill by 2014 (first prorogated to 2018, and recently prorogated to 2021); and the establishment of new instruments of management of solid residues, such as integrated waste management, shared responsibility, and reverse logistics. Besides, it requires the institutions of national, state, and municipal plans of integrated waste management; and it establishes the hierarchy of generation and management of solid residues as

20

non-generation, reduction, re-utilization, recycling, treatment, and disposal. The law considers dumpsites and controlled landfills as inappropriate final destinations and indicates sanitary landfill as the only appropriate final disposal of rejects. This requirement has been the main bottleneck for compliance with the law; still in 2017, 59.1% of final disposal sites are inappropriate (Abrelpe, 2018). Considerable difficulty has been the insufficient revenues of most municipalities in Brazil whose population is below 50,000 inhabitants. The Law of Public Consortia, prioritizing the relation among municipalities and only in second place the action of the state or the federation, spurs municipalities to join forces to find shared solutions for the management of their solid residues.

According to the principle of shared responsibility, the private sector and civil society are co-responsible with the public power for the management of residues. The PNRS attributes specific responsibilities to each actor. The public administration organizes the service of solid residues management and public cleaning, performs financial control of the installment, acquires data, and produces indicators of operation and environmental performance. The private sector (including producers, importers, distributors, and dealers) accounts for performing the reverse logistics of the products allocated to the internal market. The society and consumers are responsible for segregating and making available the residue for collection and exercise social control. The reverse logistics is the set of actions, procedures, and means for the collection and restitution of solid residues to the private sector so that they can be reused, in their cycle or other productive cycles, or finally disposed of in an environmentally appropriate way. The Federal Government coordinates agreements with different sectors for the implementation of reverse logistics. Agreements with the sectors of agrotoxin packaging, tires, batteries and bulbs, lubricating oil, electronics, and general packaging are in place.

The PNRS recognizes the role of collectors of recyclable materials to make available secondary raw materials and include them in reverse logistics. The Labor Minister acknowledged the profession in 2002 with the inclusion of “Collector of Recyclable Material” (Catador de Material Reciclável) in the national register. The PNRS aims at emancipating and integrating the collectors into the formal waste management system through the organization in cooperatives.

A policy in discussion aiming at the integration of the informal sector is the Payment for Environmental Urban Service for the Management of Solid Residue. Environmental urban services are the activities realized on the environment that generates a positive environmental externality,

or that minimize a negative one, in a way to correct market failures associated with the environment. The activity of collecting, sorting, and recycling performed by organized collectors represents an urban environmental service and would be granted economic support according to this law. A study by the IPEA estimated the current and potential economic and environmental benefits generated by recycling of the most common recyclable material (Instituto de Políticas Econômicas Aplicadas 2010). In addition to quantifying the difference in the cost of production from raw and recycled material, the economic benefits include the avoided cost in terms of consumption of natural resources and energy. The environmental benefits are more difficult to calculate and are associated with the avoided impact on the environment, on water consumption, biodiversity loss, and emission of greenhouse gases. One of the conclusions of the study is that the potential benefit of recycling all the recyclable material sent to landfill would amount to R$ 8 billion annually (in 2007 currency).

The sustainable waste management practice for organic material, correspondent to recycling, is composting. Composting not only reduces the number of rejects going to landfill, allowing them to extend their lifespan but also mitigates methane emissions from organic waste. Despite its apparent benefits, today, only 2% of the organic waste collected in Brazil goes to composting programs (IBGE, 2010).

4.3. Quantitative analysis: institutional arrangements and recycling

In the previous section, I reviewed the legal framework regulating the management of solid residues and sustainable practice, such as recycling, in Brazil. Here, I aim at understanding, on the one hand, how well Brazilian municipalities comply with current waste management legislation and, on the other hand, whether adherence to the local policy requirements and different institutional arrangements affect the quantity of recyclable material the municipality recuperates.

I approach these questions statistically by using the best available data on municipal recycling indicators, from the Diagnosis of Urban Solid Waste Management of 2016 by SNIS, and on local environmental and waste management practice, from the National Census of the Municipal Organs for Environmental Management by ANAMMA. Both these databases contain information provided voluntarily by local administrations. While this circumstance may create concerns on generalizability, I emphasize that these are currently the best available data.

22

• 90% has an environmental organ established by law and functioning. • 72% has a municipal council

• 81% has a partnership with one or more among public or private institutions, and civil society associations.

These results indicate that most cities have municipal organs in place to deliberate over environmental issues and enact environmental initiatives through partnerships. Nevertheless, adherence to local policy requirements is differentiated. Of the 477 municipalities in ANAMMA:

• 45% has a basic sanitation policy established by law and functioning. • 44% has enacted an integrated plan of solid residues management.

• 24% has an environmental education policy established by law and functioning. I now focus on the recuperation of recyclable material, specifically, on the percentage of recuperated recyclable material per year, calculated as the ratio of the annual quantity of recuperated recyclable material divided by the total annual quantity of domestic and public urban residue in percentage point (SNIS, 2019). The annual quantity recuperated include recyclables collected through the selective or standard collection by agents belonging to the municipality or working in partnership with it, such as private enterprises and cooperatives of collectors. However, it does not include the quantity recuperated by autonomous and unorganized collectors nor any other actors of the informal sector.

Half of the municipalities in ANAMMA’s sample do not recuperate any quantity of recyclable material whatsoever (the recuperation rate is precisely zero). The mean recuperation rate is 3.24% with a standard deviation of 6.83% (as twice as big as the mean), while the mean recuperation rate calculated from the sample of 3,670 municipalities in SNIS 2016 is 2.1%. The 10% highest recuperation rate is in the range of 10.53% - 55.29%.

The recuperation rate is a censored distribution. To investigate the relationship between different institutional arrangements, the policies in place or elaboration in the cities and a variety of educational actions and initiatives, I use a limited-dependent variable model consisting of a probit model and a truncated regression model (Greene, 2011). I introduce a dichotomic variable, dy, which takes the value 0 whenever the recuperation rate is exactly null and 1 in any other case. The probit models allow us to understand which (of about 60) independent variables significantly affect the probability of a city recuperating some quantity of recyclable material, no matter how small it is. After identifying the variables influencing whether a city recuperates or not, I consider

only the strictly positive recuperation rates and use a linear regression model to analyze which variables have a significant effect on the quantity recuperated.

The independent variables whose effect I will test in the probit and linear regression model are:

• Whether the municipality has an Environmental Organ; what type it is (whether it is a secretariat, directory, sector, foundation, autarchy); whether it is shared with other municipal organs; what kind of partnerships it has with public institutions or private and civil society partners.

• The region of municipality belongs to and its population.

• Whether the municipality has a Municipal Policy of Sanitation and Environmental Education and a Plan for the Integrated Management of Residues; whether it has a Municipal Council, its type (deliberative or consultative), and the frequency with which it meets; whether it has a Municipal Fund.

• Which type of environmental education initiatives the city conducts (among 23 types); and which action for tackling climate change (among 17 types).

• The outsourcing rate and cost of regular waste collection.

Before commenting on the results of the probit in Table 1 and the linear regression in Table 2, I should recall that the coefficients resulting from these regressions have entirely different meanings. In the linear regression, the marginal effect of the kth variable, namely how much the mean of the outcome variable changes when I change the regressor variable xk, is precisely equal

to the regression coefficient . Therefore, the interpretation that for a change in 1 unit in xk the

outcome variable changes of holds. However, in a probit model, the marginal effect does not equate to the regression coefficient. Instead, the marginal effect of xk on dy is given by the product

of with a standard normal probability function that depends on all other regression coefficients (Greene, 2011). Therefore, unlike in the linear regression, the coefficients of a probit model do not have an apparent interpretation. The only two features I consider of the coefficients of the probit regression are: i) their sign, that indicates whether the associated regressor has a positive or negative effect on the outcome variable; and ii) their level of statistical significance, represented with 1 to 3 stars in the tables.

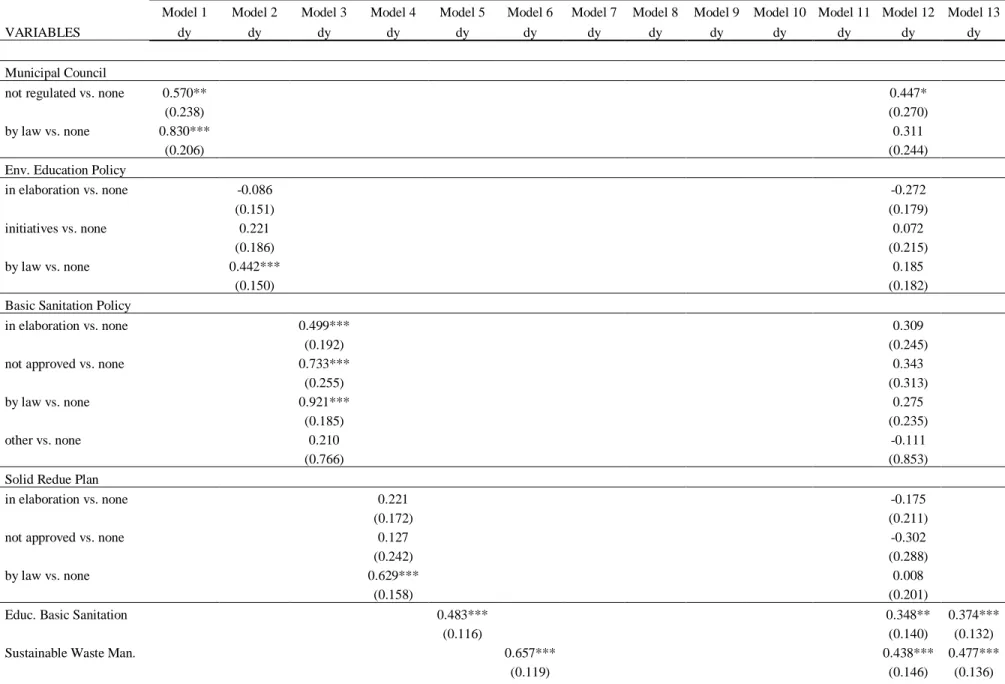

24 4.3.1. Modeling the probability of recuperating any recyclable quantity

Table 1 reports the results of the models describing the probability that a municipality recovers recyclable material or not. Each of its columns, except the first one, contains the result of a probit model of the type 2 >@U L s T5 Æ ÆT ? L 0 : 4 E ˆ T ; , describing the probability P of @UL s in terms of the cumulative function of the standard normal distribution 0 : fi; of one or more variables T , indicated in the first column of the table. I study the effect of each of all the 60 independent variables mentioned above on the recuperation rate but report in Table 1 only those that are statistically significant in a univariate probit model. I consider a coefficient as statistically significant if its p-value is below 0.05, which correspond to the values marked with two or three stars in the tables. The independent variables include both quantitative and qualitative (dichotomic or multilevel) variables.

I investigate the effect of the existence of an environmental organ in the municipality, its type (whether it is a secretariat, directory, sector, foundation, autarchy), and whether it is shared with other organs. None of these variables have a significant effect on the probability of recuperating recyclable material (for this reason, I do not report them in Table 1). The existence of a Municipal Council, even if not regulated has a significant effect (coefficients reported in Model 1 of Table 1); however, its type, whether it is deliberative or consultative, and the frequency with which it meets do not.

Notice that the regression coefficients for each ordinal independent variable are calculated against a baseline. I illustrate the meanings of the regression coefficients of Model 1. The independent variable in Model 1 is Municipal Council, whose three levels are “none,” “not regulated,” and “by law.” The first of the two coefficients reported, “not regulated vs. none,” indicates how more likely is that @UL s if the Municipal Council is not regulated than if the Municipal Council is non-existent. While the numerical value of the coefficient, 0.570**, is not of easy interpretation, its positive sign and level of significance reveal that there is a positive and statistically significant difference in the probability of recuperating recyclable material between the cities whose Municipal Councils are not regulated and the cities whose Municipal Councils is non-existent. All regression coefficients associated to ordinal variables in Table 1 have the meaning of difference in probability of @UL s between groups identified by two different values of the independent variable.

Continuing the analysis of the effect of the other variables, I find that having the Policy of Environmental Education (Model 2 in Table 1) and the municipal Plan of Integrated Management of Solid Residues (Model 4) by law has a positive and significant effect compared to not having it. For the Policy of Basic Sanitation to have a significant effect, it is enough to be just in the formulation stage compared to not having it at all (Model 3 in Table 1). The existence of the Municipal Fund does not have a significant effect. Of the 20+ initiatives of environmental education only that about Basic Sanitation has a significant effect (Model 5), and of the 30+ initiatives undertaken by the municipality for tackling climate change only Sustainable Waste Management has a significant positive effect (Model 6). The existence of partnership with NGOs, associations and other institutions of the tertiary sector (Model 7), and partnership with enterprises (Model 8) both have a significant positive effect; the same holds for the outsourcing rate of the collection (Model 9). The geographic region matters for the probability of recuperating recyclable materials: Southeast, South, and Centre-West recuperate more than North and Northeast (Model 10). The number of inhabitants matters too, having a positive and significant effect if the municipality has above 200.000 inhabitants (Model 11). The pseudo-R2 associated, accounting for the explanatory power of the fit, is 0.23.

Putting the variables significant in the univariate model together in a multivariate probit model, I find that the variables accounting for policies and institutional arrangement lose their statistical significance. The only variables that remain statistically significant are the geographical region, the number of inhabitants, and whether the municipality conducts initiatives of sustainable waste management to tackle climate change and promotes educational activities about basic sanitation (Model 12). To check that these variables have statistical power, I run a multivariate probit model (Model 13) that includes only the four variables found statistically significant in Model 12. I find that the signs, statistical significance, and size of the coefficient are maintained, while the pseudo-R2 diminishes only slightly, being 0.20. It is worth noting that most recycling industries locate in the South and Southeast region, which may explain why the probability to recover recyclables is higher in these regions.

26

Table 1. Probit models for the probability of a municipality recuperating recyclable materials or not.

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Model 6 Model 7 Model 8 Model 9 Model 10 Model 11 Model 12 Model 13 VARIABLES dy dy dy dy dy dy dy dy dy dy dy dy dy Municipal Council

not regulated vs. none 0.570** 0.447*

(0.238) (0.270)

by law vs. none 0.830*** 0.311

(0.206) (0.244)

Env. Education Policy

in elaboration vs. none -0.086 -0.272 (0.151) (0.179) initiatives vs. none 0.221 0.072 (0.186) (0.215) by law vs. none 0.442*** 0.185 (0.150) (0.182)

Basic Sanitation Policy

in elaboration vs. none 0.499*** 0.309

(0.192) (0.245)

not approved vs. none 0.733*** 0.343

(0.255) (0.313)

by law vs. none 0.921*** 0.275

(0.185) (0.235)

other vs. none 0.210 -0.111

(0.766) (0.853)

Solid Redue Plan

in elaboration vs. none 0.221 -0.175

(0.172) (0.211)

not approved vs. none 0.127 -0.302

(0.242) (0.288)

by law vs. none 0.629*** 0.008

(0.158) (0.201)

Educ. Basic Sanitation 0.483*** 0.348** 0.374***

(0.116) (0.140) (0.132)

Sustainable Waste Man. 0.657*** 0.438*** 0.477***

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Model 6 Model 7 Model 8 Model 9 Model 10 Model 11 Model 12 Model 13 VARIABLES dy dy dy dy dy dy dy dy dy dy dy dy dy NGO Partnership 0.388*** 0.095 (0.116) (0.143) Business Partnership 0.459*** 0.047 (0.125) (0.153) Outsourcing rate 0.004*** 0.002 (0.001) (0.002) Region Northeast vs. North -0.139 -0.213 -0.193 (0.263) (0.289) (0.280) Southeast vs. North 1.038*** 1.020*** 1.107*** (0.240) (0.267) (0.257) South vs. North 1.041*** 1.141*** 1.245*** (0.270) (0.308) (0.289) Centrewest vs. North 0.696** 0.879** 0.961*** (0.349) (0.381) (0.365) Inhabitants 5 to 10 k vs. < 5 k -0.152 -0.152 -0.118 (0.225) (0.248) (0.241) 10 to 20 k vs. < 5 k -0.004 0.243 0.302 (0.213) (0.240) (0.231) 20 to 50 k vs. < 5 k -0.177 -0.056 0.085 (0.203) (0.236) (0.222) 50 to 100 k vs. < 5 k 0.087 0.349 0.475* (0.235) (0.286) (0.263) 100 to 200 k vs. < 5 k 0.180 0.267 0.490 (0.279) (0.338) (0.316) > 200 k vs. < 5 k 0.940*** 0.935*** 1.146*** (0.289) (0.348) (0.312) Constant -0.706*** -0.114 -0.641*** -0.354*** -0.247*** -0.272*** -0.183** -0.147** -0.163** -0.696*** -0.023 -1.838*** -1.394*** (0.194) (0.089) (0.163) (0.132) (0.082) (0.076) (0.079) (0.070) (0.080) (0.225) (0.169) (0.412) (0.317) Observations 477 477 477 477 477 477 477 477 477 477 477 477 477 Standard errors in parentheses:

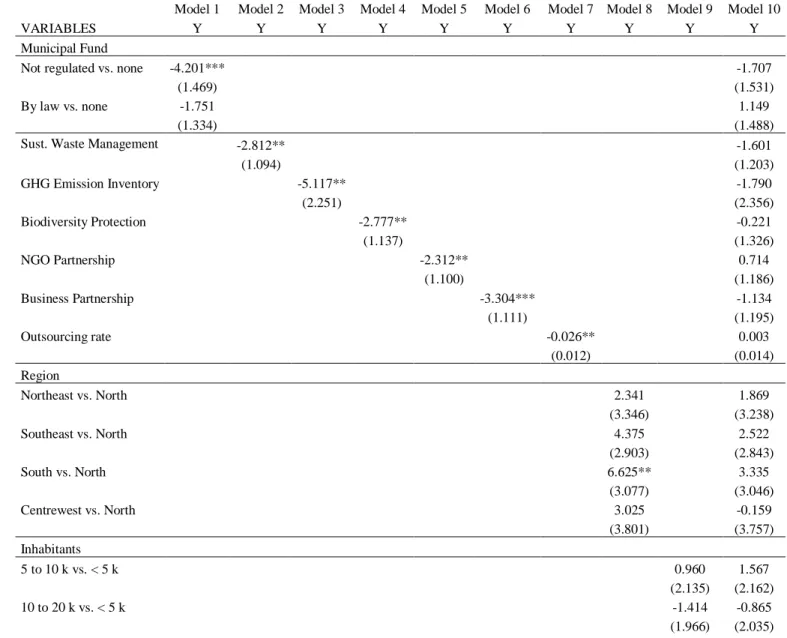

28 4.3.2. Modeling the quantity recovered by the cities that recuperate

Once I analyzed the factor affecting whether a municipality recuperates recyclable materials or not, I investigate the variables determining to what extent the municipality recuperates. In Table 2, I report the results of linear regression models, ; L 4 E ˆ T , where Y is the recuperation rate for cities that recuperate any quantity of recyclable materials (meaning that the sample is restricted to the cities characterized by dy = 1). I proceed, as in the probit case, by reporting only the univariate regression models that are significant, before considering the significant variables in a multivariate linear regression model.

The factors affecting the rate of recuperation are not the same affecting the probability to recuperate. I find that the existence of municipal environmental organs does not make a difference in Y. Neither the features of the municipal council nor the existence of policies of basic sanitation, environmental education, and the plan of residue management is significant. Because they are not significant in their respective univariate regression models, I do not include these variables in Table 2.

Unlike in the probit case, the Municipal Fund has a significant effect in the univariate regression of Model 1 in Table 2. However, its effect is somehow counterintuitive. Municipal Fund is a categorical variable with levels “none,” “not regulated,” and “by law.” The coefficient “not regulated vs. none” (“by law vs. none”) indicates the average difference in the outcome variable between two groups of cities: those whose Municipal Fund is existent but not regulated (by law) and those that do not have a Municipal Found. The interpretation of the coefficient “not regulated vs. none”, -4.201***, is that on average cities that recuperate recyclable material and that are endowed with an existent but not regulated Municipal Fund recycle on average 4.201% less than cities without a Municipal Fund, with this difference statistically significant. The interpretation of the coefficient “by law vs. none”, -1.751, is that the difference in the recuperation rate of two groups of cities that recycle, distinguished in those whose Municipal Fund is by law and those that do not have one, is a negative but not statistically significant value. At this point, I should remind that this is a univariate model and that, when incorporating other variables, such statistically significant results may disappear, as it is, in fact, the case.

No environmental educational initiatives appear to be significant in a univariate analysis. The significant initiatives for tackling climate change are sustainable waste management (Model 2 in Table 2), elaboration of the greenhouse gas emission inventory (Model 3), and protection of