CENTRO DE ARQUEOLOGIA DA UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA

5.º Congresso

do Neolítico

Peninsular

VICTOR S. GONÇALVES

MARIANA DINIZ

ANA CATARINA SOUSA

eds.

estudos &

memórias

8

5.º Congresso

do Neolítico

Peninsular

Actas

Faculdade de Letras

da Universidade de Lisboa

Casa das Histórias Paula Rego

7-9 Abril 2011

5.º Congresso

do Neolítico

Peninsular

Actas

Faculdade de Letras

da Universidade de Lisboa

Casa das Histórias Paula Rego

7-9 Abril 2011

VICTOR S. GONÇALVES

MARIANA DINIZ

estudos & memórias

Série de publicações da UNIARQ

(Centro de Arqueologia da Universidade de Lisboa) Direcção e orientação gráfica: Victor S. Gonçalves 8.

GONÇALVES, V.S.; DINIZ, M.; SOUSA, A. C., eds. (2015), 684 p.

5.º Congresso do Neolítico Peninsular. Actas. Lisboa:

UNIARQ.

Capa, concepção e fotos de Victor S. Gonçalves. Pormenor de uma placa de xisto gravada da Anta Grande da Comenda da Igreja (Montemor o Novo). MNA 2006.24.1. Museu Nacional de Arqueologia, Lisboa. Paginação e Artes finais: TVM designers

Impressão: Europress, Lisboa, 2015, 400 exemplares ISBN: 978-989-99146-1-2

Depósito Legal: 400 321/15 Copyright ©, os autores.

Toda e qualquer reprodução de texto e imagem é interdita, sem a expressa autorização do(s) autor(es), nos termos da lei vigente, nomeadamente o DL 63/85, de 14 de Março, com as alterações subsequentes. Em powerpoints de carácter científico (e não comercial) a reprodução de imagens ou texto é permitida, com a condição de a origem e autoria do texto ou imagem ser expressamente indicada no diapositivo onde é feita a reprodução.

Lisboa, 2015.

Volumes anteriores de esta série: 1.

LEISNER, G. e LEISNER, V. (1985) – Antas do Concelho

de Reguengos de Monsaraz. estudos e memórias, 1.

Lisboa: Uniarch. 2.

GONÇALVES, V. S. (1989) – Megalitismo e Metalurgia

no Alto Algarve Oriental. Uma aproximação integrada.

2 Volumes. estudos e memórias, 2. Lisboa: CAH/Uniarch/INIC.

3.

VIEGAS, C. (2011) – A ocupação romana do Algarve.

Estudo do povoamento e economia do Algarve central e oriental no período romano. estudos e memórias 3.

Lisboa: UNIARQ. 4.

QUARESMA, J. C. (2012) – Economia antiga a partir

de um centro de consumo lusitano. Terra sigillata e cerâmica africana de cozinha em Chãos Salgados (Mirobriga?). estudos e memórias 4. Lisboa: UNIARQ.

5.

ARRUDA, A. M. ed. (2013) – Fenícios e púnicos, por terra

e mar, I. Actas do VI Congresso Internacional de Estudos

Fenícios e Púnicos, estudos e memórias 5. Lisboa: UNIARQ. 6.

ARRUDA, A. M. ed. (2014) – Fenícios e púnicos, por terra

e mar, 2. Actas do VI Congresso Internacional de Estudos

Fenícios e Púnicos, estudos e memórias 6. Lisboa: UNIARQ 7.

SOUSA, E. (2014) – A ocupação pré-romana da foz do

5.º CONGRESSO DO NEOLÍTICO PENINSULAR 623

The «African Mirage» is a delusion indeed.

The distribution of the obsidian from Pantelleria

rejects a Maghreb route for the neolithization of Iberia

■

JOÃO ZILHÃO

1Introduction

The notion of a North African route for the spread of farming across the west Mediterranean and, eventually, into Iberia, has a long history. For instance, it featured prominently in Lewthwaite’s (1986) «island filter» model, where it sought to explain the putative early appearance of pottery and domesticates in Andalucian sites, namely the Cueva de la Dehesilla (Acosta and Pellicer, 1990)—as such an appearance seemed to predate the first occur‑ rence of similar material along the shores of the Gulf of Lyon, it was suggested that the phenomenon related to a dispersal from Southern Italy and Sicily via the Maghreb littoral. More recently, this hypothesis was resurrected by Manen et al. (2007) and Marchand and Manen (2010) to explain two features that they perceive in the Early Neo‑

lithic of Portugal: the predominance of segments, instead of trapeze, among geometric microliths; and the limita‑ tion of decorative patterns, which mostly feature a hori‑ zontal disposition and simple, linear motifs only, to the upper third of vessels. Here, I will argue that this notion (a) arises from erroneous readings of the archeological evidence, which is fully consistent with a coastal spread of the Neolithic package along the northern shores of west Mediterranean Europe, from Liguria to central Por‑ tugal (Zilhão, 2001), and (b) is rejected by the lack of any evidence for Mesolithic or Early Neolithic sea crossings between Sicily and Tunisia, without which the postulated link between a putative pre ‑Cardial Neolithic in the Maghreb and the pottery styles of the earliest Neolithic of Italy cannot be substantiated. The location of all sites mentioned in the text is given in Fig. 1.

A B S T R A C T The hypothesis of a North African route for the spread of farming econo‑ mies into southern and western Iberia presupposes an earlier emergence of the Neolithic in the Maghreb, where it would have emerged through cultural diffusion from Sicily. These premises are not supported by the archeological evidence. In North Africa, the ear‑ liest directly dated domesticates post ‑date by several centuries similar evidence from Valencia, Andalucía and Portugal. The finding in the nearest mainlands of obsidian from the island of Pantelleria, located about half ‑way between Tunisia and Sicily, substantiates prehistoric navigation between Europe and Africa in the central Mediterranean but not before ~5000 cal BC, when farming economies were already several centuries old in Ibe‑ ria. The material culture similarities perceived in the Early Neolithic of southern Iberia and the Maghreb may indicate a North ‑to ‑South diffusion of farming across the Strait of Gibraltar but not the reverse.

Keywords: Early Neolithic; West Mediterranean; Obsidian.

R E S U M O A hipótese segundo a qual a economia agro ‑pastoril teria chegado ao sul e ao oeste da Península Ibérica por difusão a partir do Norte de África baseia ‑se em dois pressu‑ postos: o de uma emergência do Neolítico no Magrebe em data anterior; e o da existência de uma rota de difusão cultural unindo a Sicília com a Tunísia. Estas premissas não encontram confirmação no registo arqueológico. No Norte de África, os mais antigos restos de plantas e animais domésticos directamente datados pelo radiocarbono são vários séculos mais recentes que achados semelhantes feitos em Valência, Andaluzia e Portugal. O achado em terra firme de obsidiana da ilha de Pantelleria, situada aproximadamente a meio caminho entre a Sicília e a Tunísia, documenta navegações pré ‑históricas entre a Europa e a África no Mediterrâneo Central mas não antes de ~5000 cal BC, séculos após o aparecimento de uma economia produtora na Península Ibérica. As semelhanças que eventualmente existam na cultura material do Neolítico Antigo do sul ibérico e do Magrebe podem indicar difusão atra‑ vés do Estreito de Gibraltar de norte para sul mas não no sentido inverso.

5.º CONGRESSO DO NEOLÍTICO PENINSULAR

624

THE «AFRICAN MIRAGE» IS A DELUSION INDEED. THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE OBSIDIAN FROM PANTELLERIA REJECTS A MAGHREB ROUTE FOR THE NEOLITHIZATION OF IBERIA JOÃO ZILHÃO P. 623-630

Does the SW Iberian pattern require a special explanation?

The fundamental problem with Lewthwaite’s model was that the archeological reality of the patterns it sought to explain was questionable to begin with (Zilhão, 1992, 1993). As it is now widely acknowledged, the percolation of elements of the Neolithic package, namely sheep, into hunter ‑gatherer contexts of France and eastern Iberia reflected not the «neolithization» of ancient people but that of archeological deposits (the presence, in Late Mes‑ olithic levels from cave and rockshelter sequences, of material post ‑depositionally intruded from overlying Early Neolithic occupation horizons), if not, more sim‑ ply, the misidentification of the bones of wild caprines as belonging to domesticated animals. Likewise, there is lit‑ tle question that the early dates obtained for the «Early Neolithic» of Cueva de La Dehesilla, including results as early as ~7200 cal BC, reflect the mixed, Paleolithic and Neolithic composition of the deposits, not the appear‑ ance of the Neolithic package in Andalucía hundreds of years before it is first recorded elsewhere in the west Mediterranean (and, where pottery is concerned, almost a millennium before it first appeared in the Near East).

The more recent versions of the African route are not immune to similar problems of relation between reality and model. For instance, the notion that the microliths of the initial phase of the Portuguese Early Neolithic tend to be segments instead of trapeze cannot be supported with

available evidence, as shown by the nature of the only three sealed, dated contexts that can be considered in the discussion of this issue (Carvalho, 2007): (a) horizon NA2 of Gruta do Caldeirão, a cave burial context with Cardial ceramics, which contained a single microlith, and that was a trapeze; (b) layer Eb ‑base of the Abrigo da Pena d’Água, a rockshelter settlement context with Cardial ceramics, which also contained a single complete micro‑ lith, in this case a segment (but where two items classi‑ fied as «truncated bladelets» probably correspond to bro‑ ken trapeze); and (c) Cabranosa, an open air settlement site where the lithic assemblage lacked microliths (although the first publication of the finds—Zbyszewski et al., 1981—mentions that the Cardial ceramics recov‑ ered therein were associated with a few trapeze).

Given these counts and the very small size of the lithic assemblages concerned, the relative importance of tra‑ peze and segments in the initial phase of the Portuguese Early Neolithic remains a mute point, a conclusion that does not change even if we also consider the Early Neo‑ lithic burial context of Galeria da Cisterna (Almonda). This context featured three microliths, all segments indeed, but corresponds to a palimpsest where, on typo‑ logical grounds and by comparison with French and Spanish sequences, four different moments of Early Neo‑ lithic occupation can be differentiated: Impressa, Early Cardial, Late Cardial and Epicardial (Zilhão, 2009; Chap‑ man and Zilhão, n.d.; Figs. 2 ‑3). Although commentators have linked the segments with the earlier styles, they may Fig. 1 Location of the Central Mediterranean obsidian sources (stars) and of the sites mentioned in the text (diamonds). 1. Cabranosa; 2. Vale Pincel;

3. Galeria da Cisterna (Almonda); 4. Abrigo da Pena d’Água; 5. Gruta do Caldeirão; 6. El Retamar; 7. Cueva de La Dehesilla; 8. Cueva de Nerja; 9. Mas d’Is; 10. Cova Fosca; 11. Kef Taht el Ghar; 12. Ifri Armas; 13. Sebkhet Halk el Menjel; 14. Doukanet el Koutifa; 15. Kef Hamda; 16. Ghar Dalam; 17. Grotta dell’Uzzo; 18. Villa Badesso.

5.º CONGRESSO DO NEOLÍTICO PENINSULAR 625 THE «AFRICAN MIRAGE» IS A DELUSION INDEED. THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE OBSIDIAN FROM PANTELLERIA REJECTS A MAGHREB ROUTE FOR THE NEOLITHIZATION OF IBERIA JOÃO ZILHÃO P. 623-630

in fact relate instead to the Late Cardial or the Epicardial episodes, to which belong some 90% of the 40 decorated Early Neolithic vessels represented in the collection.

On the other hand, the stylistically early pottery from the Galeria da Cisterna makes it clear that unwarranted generalization also underlies the other argument upon which the African route has been put forth—that the Late Cardial decorative styles characterized by rows of impres‑ sions limited to the upper third of the vessel (well exem‑ plified by the ceramics from horizon NA2 of Gruta do Caldeirão, dated to the 5300 ‑5100 cal BC interval) are representative of the initial phase of the Portuguese Early Neolithic in its entirety. However, Vessels I and II from Galeria da Cisterna (Fig. 2), dated to ~5400 cal BC (on the basis of their probable association with the two directly dated beads identified in Fig. 3; Zilhão, 2001), show that the Early Cardial of Portugal was no different in this regard from that of e.g. Valencia, as both vessels are extensively decorated from rim to bottom (in one case

with the edge of a Cardium shell and in the other with a comb).

The only thing special about the Portuguese Early Neo‑ lithic when seen in its European context is, therefore, the dearth of sites and the extensive lacunae that remain in our knowledge of it. No explanation other than the haz‑ ards of research history is necessary to account for this situation—an African route is no more required to under‑ stand the emergence of farming in Portugal than it would be to understand it in France or Spain. Showing that the hypothesis is unnecessary does not, however, suffice to refute it—a significant level of cultural interaction could nonetheless have existed across the Strait of Gibraltar at this time, and it could have been via such exchanges of people and/or ideas and technologies that pottery and domesticates first entered Southwestern Iberia indeed.

Assessing this possibility on its own merits begs the two key questions to which I now turn: Does farming emerge in the Maghreb earlier than on the opposite

Fig. 2 Early Neolithic ceramics from Galeria da Cisterna (Almonda): vessel IV, Ligurian Impressa (impressed groove) style; vessel I, early Cardial style;

5.º CONGRESSO DO NEOLÍTICO PENINSULAR

626

THE «AFRICAN MIRAGE» IS A DELUSION INDEED. THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE OBSIDIAN FROM PANTELLERIA REJECTS A MAGHREB ROUTE FOR THE NEOLITHIZATION OF IBERIA JOÃO ZILHÃO P. 623-630

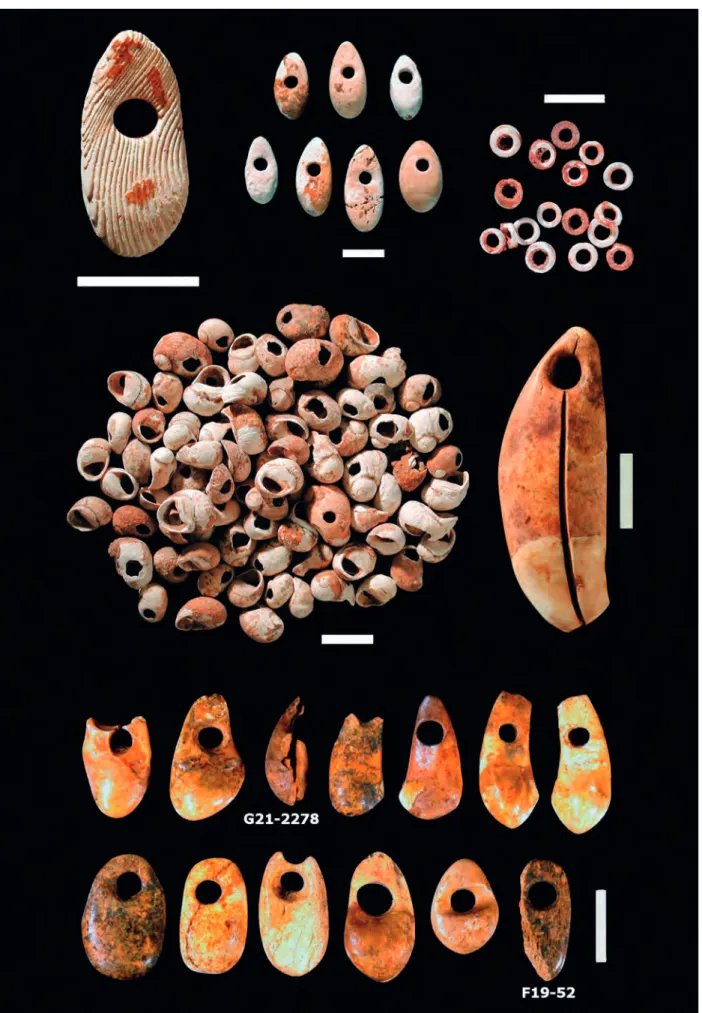

Fig. 3 Early Neolithic ornaments from the Galeria da Cisterna (Almonda). Top row, left to right: oval pendant made on cuttlefish shell (Sepia officinalis);

seven oval pendants made on Glycymeris sp. shells; discoidal limestone beads. Middle row, left to right: Theodoxus fluviatilis shell beads; pierced wolf canine. Bottom row: pierced red deer canines and bone pendants imitating their shape (the two radiocarbon ‑dated specimens are indicated by the corresponding inventory numbers). [photos ‑ J. P. Ruas (top and middle rows) and F. d’Errico (bottom row); all scale bars = 1 cm].

5.º CONGRESSO DO NEOLÍTICO PENINSULAR 627 THE «AFRICAN MIRAGE» IS A DELUSION INDEED. THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE OBSIDIAN FROM PANTELLERIA REJECTS A MAGHREB ROUTE FOR THE NEOLITHIZATION OF IBERIA JOÃO ZILHÃO P. 623-630

shores of the Mediterranean? And what is the evidence, if any, for a connection between Sicily and Tunisia whereby farming could have spread to the Rif mountains and the Tangier peninsula at such an early date?

The chronology of the Early Neolithic of the Maghreb

The dearth of stratified sequences and of reliable radi‑ ometric results makes it very difficult to reach a consen‑ sus on the nature of the North African process (cf. Lin‑ städter, 2008, for a recent review). The situation at the key site of Kef Taht el Ghar suffices to illustrate the problem. Three different varieties of domestic wheat were reported from layer G, in association with charcoal dates ranging between 9000 and 10,000 cal BC, although sheep and goats only appear in overlying level F and in association with Cardial pottery. A cereal grain from this level yielded a direct date of ~5300 cal BC that is consistent with the nature of the ceramic assemblage. Thus, the main lesson from Kef Taht el Ghar is that the Maghreb sites are not immune to the problems of post ‑depositional distur‑ bance that afflict the Mesolithic ‑Neolithic sequences from cave and rockshelter sites of Mediterranean Europe. The presence of inherited charcoal in Early Neolithic deposits is also a major problem in the Maghreb, explain‑ ing the very early results obtained for some pottery‑ ‑bearing deposits. A good example is Ifri Armas, in the Eastern Rif, where a result on bone dates its Neolithic with impressed and incised pottery to ~4900 cal BC, in line with the ages obtained for the stylistically equivalent Epicardial of west Mediterranean Europe; two results on charcoal, however, yielded much earlier ages, in the 5600 ‑6000 cal BC interval (Linstädter, 2008, Fig. 5).

Therefore, I concur with Linstädter that there is every reason to be extremely wary of interpretations of (a) the presence of ceramics in Epipaleolithic contexts of the Maghreb as documenting an early invention/adoption of the technology, or (b) the association of impressed, non‑ ‑Cardial wares with early radiometric results as docu‑ menting a pre ‑Cardial spread of the Neolithic into the region. Similar claims were made in the 1970s and 1980s for a number of contexts located on the Iberian side of the Mediterranean (e.g., Vale Pincel, in Portugal, or Cova Fosca, in Spain). All were eventually shown to be either specific manifestations of the process of «neolithization of deposits» or instances of palimpsest formation related to Early Holocene sedimentation hiatuses (Zilhão, 1993, 1998). With present evidence, therefore, we can only con‑ clude that the earliest Neolithic of the Western Maghreb is of Cardial affinities and post ‑dates by at least two and a half centuries the emergence of farming in Iberia, which dates obtained on samples of barley seed from the open air site of Mas d’Is (Valencia) and sheep bone from the cave site of Cueva de Nerja (Málaga) set at ~5550 cal BC (Bernabeu et al., 2009). In this context, if similarities

do exist in decorative style between the two sides of the straits, and if they are to be interpreted indeed as docu‑ menting the diffusion of people or ideas, then the ines‑ capable conclusion is that such a diffusion occurred from North to South rather than from South to North.

The Early Neolithic navigation of the Mediterranean

The 10 ‑15 km of the Strait of Gibraltar would have been a trivial distance for experienced seafarers, but the notion that the Iberian Neolithic spread northward from the Maghreb implies the occurrence at an earlier time of a crossing of a different order of magnitude, that from Sic‑ ily to Tunisia. The distance involved is of some 150 km, although, using the island of Pantelleria as a stepping stone, it can be made in two legs (of ~100 km, the first, and of ~70 km, the second; Fig. 1).

The settlement of Cyprus and Crete shows that early farmers of the eastern Mediterranean undertook colo‑ nizing expeditions involving deep planning and the transportation of groups of people and cargo over mari‑ time crossings in the range of those two legs (Broodbank and Strasser, 1991; Vigne and Cucchi, 2005). Moreover, in the Cyprus case, the morphological similarity with those from the Levant maintained over the subsequent millen‑ nia by the populations of domestic mice introduced alongside indicates sustained genetic flow and, there‑ fore, implies a pattern of routine boat traffic with the mainland. The navigation knowledge and equipment documented by the Aegean evidence must also have been a prerequisite for the colonization of Malta (Evans, 1977; Robb, 2001; Malone, 2003), where the decorative patterns of the impressed ceramics from the earliest Neo‑ lithic (as documented at the key cave site of Ghar Dalam) allow us to trace the island’s initial settlers to the Stenti‑ nello culture of Sicily and Calabria, implying a sea cross‑ ing of ~80 km.

Further to the west, the pattern is different. The coastal location of the earliest Neolithic settlements and the presence in sites from mainland Italy, southern France and Catalonia of island resources, namely obsidian from Lipari and Sardinia (Tykot, 1996, 1997), are consistent with colonization via sea routes. However, such large islands as the Balearics remained uninhabited during the Neolithic (Ramis et al., 2002). This is despite the distance between Ibiza and the adjacent Spanish coast being sim‑ ilar to that separating Crete from the southern tip of the Peloponnese and the sea crossing from Ibiza to Mallorca being about the same. Moreover, despite its ubiquity around the coasts of the Tyrrhenian sea and the Gulf of Lyon, no obsidian from Lipari has ever been found in the early Neolithic of Sardinia and Corsica, while the amounts recovered and the parts of the chaîne opératoire represented in the French sites indicate that the Lipari obsidian circulated by down ‑the ‑line exchange and/or

5.º CONGRESSO DO NEOLÍTICO PENINSULAR

628

THE «AFRICAN MIRAGE» IS A DELUSION INDEED. THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE OBSIDIAN FROM PANTELLERIA REJECTS A MAGHREB ROUTE FOR THE NEOLITHIZATION OF IBERIA JOÃO ZILHÃO P. 623-630

the movement of persons transporting individual tool‑ ‑kits (Tykot, 2002; Lugliè, 2009). Combined, this evidence suggests that, in the west Mediterranean, the maritime dispersal of farming and farmers was effected by cabo‑ tage, over coastal waters and involving short mainland‑ ‑island or island ‑island crossings but not targeted land‑ falls in previously reconnoitered territories located across significant expanses of open sea (Chapman and Zilhão, n.d.).

The distribution of the obsidian from Pantelleria

The evidence concerning navigation in the west Med‑ iterranean argues against the likelihood of farming to have been ferried to Tunisia from Sicily during the latter’s earliest Neolithic, and all the more so since no evidence exists for the settlement of Pantelleria before the Bronze Age. It is often assumed, however, that quarrying of this island’s obsidian must have begun much earlier, on the basis of reports that the stuff is represented in stone tool inventories from the Epipaleolithic and the Early Neo‑ lithic of Tunisia and Sicily, whence it would have spread as far from its source as the islands of Malta and Lampe‑ dusa (Vargo, 2003). If such claims could be verified, we would be forced to conclude that central Mediterranean sea crossings between Europe and Africa did occur at this time, and a littoral Maghreb route would thus remain a distinct possibility for the spread of the Neolithic into southern and western Iberia.

The data, however, are often too imprecise for an inde‑ pendent observer to be able to assess the validity of the association of the items made of Pantelleria obsidian with the contexts where they are supposed to come from and/or the dates obtained for such contexts. Where Sic‑ ily is concerned, the evidence consists entirely of mate‑ rial from the Grotta dell’Uzzo (Tykot, 1996; Malone, 2003). Well known for its early Mesolithic habitation and burial contexts, the upper reaches of this site’s stratigra‑ phy are, however, controversial. It is claimed that, after a «Transitional» Mesolithic ‑Neolithic level dated to between 7000 and 6600 cal BC and characterized by the presence of decorated pottery in an otherwise purely Mesolithic hunter ‑gatherer context, two early Neolithic occupation horizons exist, the earliest ranging from 5800 to 5600 cal BC and the youngest from 5650 to 5500 cal BC. It is further claimed that obsidian is present throughout the Neolithic levels and that 40% of the 152 items ana‑ lyzed are from Pantelleria.

The presence of Cardial pottery in the Mesolithic lev‑ els of Uzzo, however, indicates that the sequence under‑ went unrecognized post ‑depositional disturbance at the Mesolithic ‑Neolithic interface. This fact casts doubt (a) on the extent to which the recovered obsidian is associ‑ ated with the Neolithic from its beginnings or only with the youngest occupation horizons, and (b) on the relia‑

bility of the charcoal dates used to establish the chronol‑ ogy of the site’s Geometric Cardial facies (P ‑2733, 6750±70 BP, 2σ calibration interval 5767 ‑5530 cal BC; P ‑2734, 7910±70 BP, 2σ calibration interval 7042 ‑6642 cal BC). Moreover, the Early Neolithic culture ‑historical sequences of Sicily and Southern Italy follow in parallel (Malone, 2003), and the obsidian from Lipari is wide‑ spread in mainland Italy. This evidence the existence of extensive networks of raw ‑material circulation encom‑ passing both sides of the Strait of Messina. Therefore, if obsidian from Pantelleria had made its way into Sicily at the time indicated by those Uzzo dates, one would expect it to have been distributed into (and to have been found on) the mainland side too, even if in small amounts. However, that is not the case. The earliest recorded occurrence of Pantelleria obsidian in Italy is at the site of Villa Badesso, in the province of Pescara (Tykot, 1996), which belongs to the Catignano culture, dated to the 5000 ‑4500 cal BC interval.

Thus, by the time when the presence in Italy of obsid‑ ian from Pantelleria and, by implication, sea crossings to the island and, possibly, beyond it to North Africa, are securely documented, farming groups had already set‑ tled eastern and southern Iberia for more than half a mil‑ lennium, making the establishment of a route of diffu‑ sion and/or migration between Sicily and Tunisia irrelevant to explain the genesis of such groups. However, the notion that Pantelleria obsidian is present in Epipale‑ olithic sites of the eastern Maghreb (Camps, 1964) could still salvage the African hypothesis for the emergence of the Neolithic in Iberia under scenarios of independent invention or local adoption. Namely, maritime hunter‑ ‑gatherer societies from around the shores of Cape Bon possessing the advanced navigation skills proved by the capacity to acquire that obsidian could likewise have obtained domesticates and pottery from distant sources at a relatively early date, spreading them westward and, eventually, northward too, across the Strait of Gibraltar.

A recent study of the prehistoric obsidian from Tunisia (Mulazzani et al., 2010), however, shows that the archeo‑ logical reality of the putative pre ‑Neolithic quarrying of Pantelleria obsidian by people from North Africa lies on unreliable evidence, consisting for the most part of sur‑ face finds. There are only three instances where that obsidian has been found in stratified archeological con‑ texts. In two, Doukanet el Koutifa (where the context is described as Neolithic and three out four radiocarbon dates on charcoal place it in the 5300 ‑4700 cal BC inter‑ val, i.e., in the time range of the first occurrence of Pan‑ telleria obsidian in mainland Italy) and Kef Hamda (where it is associated with dates in the 7000 ‑6000 cal BC range), the finds were made in escargotières that, as cau‑ tioned by Mulazzani et al., (2010, p. 2534) had «complex post ‑depositional/reworking histories, so that their 14C

ages do not necessarily correspond to that of the obsidi‑ ans’ deposition.» The other instance is site SHM ‑1, located on the western edge of the retro ‑coastal lagoon

5.º CONGRESSO DO NEOLÍTICO PENINSULAR 629 THE «AFRICAN MIRAGE» IS A DELUSION INDEED. THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE OBSIDIAN FROM PANTELLERIA REJECTS A MAGHREB ROUTE FOR THE NEOLITHIZATION OF IBERIA JOÃO ZILHÃO P. 623-630

of Sebkhet Halk el Menjel, in the Hergla coast. Extensive testing carried out here in 2002 revealed a 1.5 m ‑deep sequence with seven occupation levels described as Epi‑ paleolithic on the basis of material culture and subsist‑ ence evidence. Eleven obsidian pieces were recovered in the three uppermost levels, dated to the 6200 ‑5500 cal BC interval, but all are very small, <2.5 cm items, mostly frag‑ ments, and associated with pottery that the authors describe as «relatively abundant» and accompanied by «other elements of material culture traditionally associ‑ ated to the Neolithic» (Mulazzani et al., 2010, p. 2530).

The SMH ‑1 stratigraphic pattern suggests that the ceramics and the obsidian form an integrated artifact package and indicate Neolithic activity in the area rather than local hunter ‑gatherers having possessed such items of material culture. Taking place on the surface of areas intensively occupied by Epipaleolithic hunter ‑gatherers at a previous time, such Neolithic activity would have left remains that, inevitably, through ordinary soil formation processes, would have penetrated subsurface and pro‑ duce an apparent stratigraphic association with the remains of the earlier Epipaleolithic occupations, a pro‑ cess well known in open air sites of Portugal (e.g., Vale Pincel) and western Andalucía (e.g., El Retamar) that are located in similar settings and also feature both Meso‑ lithic and Neolithic occupations (Zilhão, 1998, 2011). That such is the case at SMH ‑1 too is additionally shown by the finding of ceramics in the site’s four oldest layers, as acknowledged by Mulazzani et al. (2010, p. 2530). The potsherd fragments found in these deeper levels are rare and small, as one would expect in a scenario where the ceramics (and, by inference, the obsidian) are post‑ ‑depositional Neolithic intrusions in a previously accu‑ mulated Epipaleolithic sequence—as they must be, given that the pottery ‑bearing basal layers of the SMH ‑1 sequence date to ~6750 cal BC, i.e., to several centuries before the emergence of the Pottery Neolithic in the Near East itself (Maher et al., 2011).

Conclusion

The notion of a littoral Maghreb route for the spread of the Neolithic into Iberia depends on the notion that it arrived in North Africa via Sicily. However, there is no evi‑ dence that the stretch of sea in between was navigated in Epipaleolithic and Early Neolithic times: no African raw‑ ‑materials (e.g., ostrich egg ‑shell) have been found in coeval sites of Sicily and southern Italy, and no Italian raw ‑materials (e.g., Lipari obsidian) have been found in coeval sites of Tunisia. Such a connection might have been established as a result of the quarrying of obsidian from Pantelleria by groups originating from both sides of the Mediterranean and using the island as a trading post, but there is no secure evidence that Pantelleria obsidian was being quarried and distributed to neighboring terri‑ tories before 5000 cal BC. By this time, Neolithic societies

were already several centuries old in Mediterranean Spain and, but for the Cantabrian strip, farming and herding had already expanded across all of Iberia, so their emergence cannot be explained by the establish‑ ment of a Siculo ‑Tunisian route of raw ‑material exchange and cultural diffusion. On present evidence, the Neo‑ lithic is also earlier in eastern and southern Spain than in the western Maghreb. Here, moreover, Cardial ceramics lack any antecedents, while, across the Strait of Gibraltar, they are preceded by Impressa wares of Ligurian affini‑ ties. If anything, these chronological and material culture patterns indicate that, after diffusing from the Gulf of Lyon to western Andalucía and southern Portugal via cabotage along the northern shores of the Mediterra‑ nean, the Neolithic then spread from these areas into the Maghreb, rather than the other way around.

1 ICREA Research Professor at the University of Barcelona

Seminari d’Estudis i Recerques Prehistòriques;

Departament de Prehistòria, Història Antiga i Arqueologia; Facultat de Geografia i Història

C/ Montalegre 6; 08001 Barcelona; Spain joao.zilhao@ub.edu

R E F E R E N C E S

ACOSTA, P; PELLICER, M. (1990) — La cueva de la Dehesilla (Jerez

de la Fontera). Jerez: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

BERNABEU, J.; MOLINA, L.; ESQUEMBRE, M. A.; RAMÓN, J.; BORONAT, J. D. (2009) — La cerámica impresa mediterránea en el origen del Neolítico de la península Ibérica? In De Méditerranée et d’ailleurs…

Mélanges offerts à Jean Guilaine. Toulouse: Archives d’Écologie

Préhistorique. p. 83 ‑95.

BROODBANK, C.; STRASSER, T. F. (1991) — Migrant farmers and the Neolithic colonization of Crete. Antiquity. 65, p. 233 ‑245. CAMPS, G. (1964) — Notes de protohistoire nord ‑africaine, III. Industries

en obsidienne de l’Afrique du Nord. Libyca. 12, p. 292 ‑297. CARVALHO, A. F. (2007) — A neolitização do Portugal meridional.

Os exemplos do Maciço Calcário Estremenho e do Algarve ocidental.

Ph. D. dissertation, University of the Algarve.

CHAPMAN, J.; ZILHÃO, J. (n.d.) — Early Food Production in Southern Europe. In RENFREW, C.; BAHN, P., eds. — The Cambridge World

Prehistory. Cambridge: University Press (in press).

EVANS, J. D. (1977) — Island archaeology in the Mediterranean: problems and opportunities. World Archaeology. 9, p. 12 ‑25.

LEWTHWAITE, J. (1986) — From Menton to the Mondego in three steps: application of the availability model to the transition to food production in Occitania, Mediterranean Spain and Southern Portugal. Arqueologia. 13, p. 95 ‑112.

LINSTÄDTER, J. (2008) — The Epipalaeolithic ‑Neolithic ‑Transition in the Mediterranean region of Northwest Africa. Quartär. 55, p. 41 ‑62. LUGLIÈ, C. (2009) — L’obsidienne néolithique en Méditerranée

occidentale. In MONCEL, M. ‑H.; FRÖHLICH, F., eds. — L’Homme

et le précieux. Matières minérales précieuses. British Archaeological

Reports International Series 1934. p. 213 ‑224.

MAHER, L. A.; BANNING, E. B.; CHAZAN, M. (2011) — Oasis or Mirage? Assessing the Role of Abrupt Climate Change in the Prehistory of the Southern Levant. Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 21 (1), p. 1 ‑29.

MALONE, C. (2003) — The Italian Neolithic: A Synthesis of Research.

5.º CONGRESSO DO NEOLÍTICO PENINSULAR

630

THE «AFRICAN MIRAGE» IS A DELUSION INDEED. THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE OBSIDIAN FROM PANTELLERIA REJECTS A MAGHREB ROUTE FOR THE NEOLITHIZATION OF IBERIA JOÃO ZILHÃO P. 623-630

MANEN, C.; MARCHAND, G.; CARVALHO, A. F. (2007) — Le Néolithique ancien de la péninsule Ibérique: vers une nouvelle évaluation du mirage africain? In Actes du 26e Congrès Préhistorique de France, Avignon,

21 ‑25.7.2004. Paris: Société Préhistorique Française. p. 133 ‑151.

MARCHAND, G.; MANEN, C. (2010) — Mésolithique final et Néolithique ancien autour du détroit: une perspective septentrionale (Atlantique/ Méditerranée). In GIBAJA, J. F.; CARVALHO, A. F., eds. — Os últimos

caçadores ‑recolectores e as primeiras comunidades produtoras do sul da Península Ibérica e do norte de Marrocos. Promontoria Monográfica

15. Faro: Universidade do Algarve. p. 173 ‑179.

MULAZZANI, S.; LE BOURDONNEC, F. ‑X.; BELHOUCHET, L.; POUPEAU, G.; ZOUGHLAMI, J.; DUBERNET, S.; TUFANO, E.; LEFRAIS, Y.; KHEDHAIER, R. (2010) — Obsidian from the Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic eastern Maghreb. A view from the Hergla context (Tunisia).

Journal of Archaeological Science. 37, p. 2529 ‑2537.

RAMIS, D.; ALCOVER, J. A.; COLL, J.; TRIAS, M. (2002) — The Chronology of the First Settlement of the Balearic Islands. Journal of Mediterranean

Archaeology. 15 (1), p. 3 ‑24.

ROBB, J. (2001) — Island identities: ritual, travel and the creation of difference in Neolithic Malta. European Journal of Archaeology. 4 (2), p. 175 ‑202.

TYKOT, R. H. (1996) — Obsidian Procurement and Distribution in the Central and Western Mediterranean. Journal of Mediterranean

Archaeology. 9 (1), p. 39 ‑82.

TYKOT, R. H. (1997) — Characterisation of the Monte Arci (Sardinian) obsidian sources. Journal of Archaeological Science. 24, p. 467 ‑479. TYKOT, R. H. (2002) — Chemical Fingerprinting and Source Tracing of

Obsidian: The Central Mediterranean Trade in Black Gold. Accounts

of Chemical Research. 35 (8), p. 618 ‑627.

VARGO, B. A. (2003) — Characterization of obsidian sources in Pantelleria,

Italy. University of South Florida, Theses and Dissertations, Paper 1501

(http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/1501).

VIGNE, J. ‑D.; CUCCHI, T. (2005) — Premières navigations au Proche Orient: les informations indirectes de Chypre. Paléorient. 31 (1), p. 186 ‑194.

ZBYSZEWSKI, G.; FERREIRA, O. V.; LEITÃO, M.; NORTH, C. T.; NORTON, J. (1981) — Nouvelles données sur le Néolithique Ancien de la station à céramique cardiale de Sagres (Algarve). Comunicações dos Serviços

Geológicos de Portugal. 67, p. 301 ‑311.

ZILHÃO, J. (1992) — Gruta do Caldeirão. O Neolítico Antigo. Lisboa: Instituto Português do Património Arquitectónico e Arqueológico. ZILHÃO, J. (1993) — The spread of agro ‑pastoral economies across

Mediterranean Europe: A view from the Farwest. Journal

of Mediterranean Archaeology. 6 (1), p. 5 ‑63.

ZILHÃO, J. (1998) — A passagem do Mesolítico ao Neolítico na costa do Alentejo. Revista Portuguesa de Arqueologia. 1 (1), p. 27 ‑44. ZILHÃO, J. (2001) — Radiocarbon evidence for maritime pioneer

colonization at the origins of farming in west Mediterranean Europe.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 98,

p. 14180 ‑14185.

ZILHÃO, J. (2009) — The Early Neolithic artifact assemblage from the Galeria da Cisterna (Almonda karstic system, Torres Novas, Portugal). In De Méditerranée et d’ailleurs. Mélanges offerts à Jean Guilaine. Toulouse: Archives d’Écologie Préhistorique. p. 821 ‑835. ZILHÃO, J. (2011) — Time Is On My Side… In HADJIKOUMIS, A.;

ROBINSON, E.; VINER, S., eds. — The dynamics of neolithisation

in Europe: studies in honour of Andrew Sherratt. Oxford: Oxbow