AGRADECIMENTOS

À minha orientadora, Professora Doutora Maria Inês Águeda de Azevedo, pela ideia de desenvolver este trabalho, pela ajuda e disponibilidade e pela partilha de conhecimentos, enquanto mãe e pediatra que sem dúvida o enriqueceram.

Ao meu coorientador, Dr. Manuel Ferreira de Magalhães, pelo apoio na execução deste trabalho e pela ajuda na análise estatística dos dados.

À Dra. Lina Costa, especialista em Medicina Geral e Familiar, à Dra. Diana Dias e Dra. Sara Barbosa, internas da especialidade de Medicina Geral e Familiar, pela ajuda com a aplicação dos questionários na população saudável.

À Dra. Catarina Ferraz por ter sido o elo de ligação com alguns dos cuidadores entrevistados.

Ao Tiago, pela paciência que estes anos exigiram, por ter estado sempre ao meu lado, pelo tempo que o "estudo" nos roubou, por apesar da distância, nunca me ter deixado sentir sozinha... O mundo para ti... sempre!

Aos meus pais por estarem sempre presentes, pela ajuda, pelas "secas" que apanham a ler os meus trabalhos, por acreditarem, por mais uma vez terem permitido que eu sonhasse, por tanto...e tão só pelo amor incondicional e por continuarem a ser sempre o meu porto de abrigo.

À minha avó Fernanda por ter estado ao meu lado em mais uma viagem, pela ajuda com as propinas, pela "sintonização dos canais". Pelo amor.

À minha irmã por nos continuarmos a encontrar nas diferenças, até ao fim do mundo. À minha sobrinha Maia por me guiar, todos os dias, por novas descobertas, pelo amor incondicional e "visceral".

À minha família que está sempre presente, principalmente à minha tia Lé e ao meu tio Ângelo que sem saberem tanto me influenciaram na Medicina.

Aos meus amigos de sempre por fazerem parte da minha vida, por tornarem possível o facto de estarmos longe mas parecer que estivemos juntos ontem, por me desculparem as vezes que sou uma amiga desnaturada.

Aos meus professores da FMUP pelo rigor e exigência que sem dúvida me farão uma médica melhor. Aos amigos e colegas de curso, principalmente à turma 14, pela companhia nesta longa viagem e pela amizade que sem dúvida perdurará.

1 Burden of caregivers of children on long-term ventilation

Sara Beato, 1

Manuel Ferreira-Magalhães, MD 2,3,4

Inês Azevedo, MD,PhD,2,4

1 Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

2 Department of Pediatrics, Centro Hospitalar de S. João, Porto, Portugal;

3 CINTESIS – Center for Research in Health Technologies and Information Systems – Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal;

4 Department of Pediatrics – Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; Correspondence: Sara Beato; Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto - Al. Prof.

Hernâni Monteiro, 4200 - 319 Porto, PORTUGAL. E-mail:mimed09285@med.up.pt

Keywords: Home ventilation; asthma; Zarit burden interview; pediatrics.

2 Abstract

Background: Caring for a child with chronic health problems presents extra challenges for caregivers and can negatively influence their physical and psychological health. Caregivers of children under long-term home ventilation in countries with nurse support describe feeling of burden. It is important to address the impact of home ventilation in caregivers living in countries where such support does not exist. This study aimed to evaluate the burden felt by caregivers of children under long-term home ventilation, compared to caregivers of children with asthma and children without chronic diseases. We also aimed to assess the determinants of burden felt by caregivers in these groups.

Methods: 26 caregivers of children under long-term ventilation, 20 of children with asthma, and 37 of healthy children, were interviewed with the Portuguese version of the Zarit Burden Interview. Questions on socio-educational factors were included. We used multivariate logistic regression analysis to compare the Zarit Score among the three groups of study.

Results: Caregivers’ feeling of burden was higher among caregivers of the home ventilation group (Home ventilation group vs Healthy group: OR:1.25 (p<0.001); aOR: 1.36 (p<0.037); Home ventilation group vs Asthma group: OR:1.20 (p<0.001); aOR:1.24 (p<0.009)). Caregivers' burden was associated with caregivers' age (r2=0.228; p=0.014) and employment status (p=0.041), but not with the other assessed socioeconomic factors.

Conclusion: The majority of caregivers (88%) of children under long-term home ventilation felt a significant burden; in a third of cases this burden was moderate to severe.

3 INTRODUCTION

Caring is a normal part of being parent and each child requires resources to proper development. However, raising a child with chronic health problems presents extra challenges for caregivers 1.

Caring for a child with disabilities and health special needs can negatively influence the physical and psychological health of the caregiver 1,2. Burdened caregivers present more often anxiety disorders, depression and even higher morbidity and mortality 3,4.

Different pulmonary chronic diseases may be important drivers of caregiver burden 5,6. Asthma, one of the most common chronic diseases in childhood, may impair caregivers’ quality of life, mostly related with need for chronic medication and health services attending 6,7. In the other side of pulmonary chronic diseases spectrum, recent evidence pointed towards an increased risk of emotional disorders, shorter duration and worst sleep quality in caregivers of long-term home ventilated children, these results were also associated with poorer health outcomes 8,9.

In the past decades, there has been an increase of children requiring long-term home ventilation, due to the increased survival of children with respiratory failure. Home ventilation programs have been developed worldwide in order to decrease the cost and duration of hospitalizations and to promote a child-centered care within the family and the community 10,11. However, it is important to address the impact of these programs in the caregivers, specifically in countries where home nursing support is not provided by public funding.

This study aimed to evaluate the burden felt by caregivers of children on long-term home ventilation, comparing with children with asthma and children without

4 chronic disease. We also aimed to assess the determinants of burden felt by caregivers in these groups.

5 METHODS:

Study design and participants

We performed a cross-sectional study in Northern Portugal. This study was carried in two medical centers: Centro Hospitalar São João (CHSJ), a tertiary referral hospital; and Unidade de Saúde Familiar São Bento (USF-São Bento), a primary care medical center.

The caregivers of home ventilated children and of children with asthma were consecutively selected at the pediatric pulmonology outpatient clinic from CHSJ. The caregivers of healthy children were consecutively selected in primary care routine appointments at USF-São Bento.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: ‘Home Ventilation Group’ (HVG): children under long-term home ventilation with pediatric pulmonology follow-up in CHSJ. Long-term home ventilation was defined as invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation, for a period of at least 3 months on a daily basis, carried out mostly in the user’s home or other long-term care facility (not a hospital) 12

. ‘Asthma Group’ (AG): children with doctor diagnose of asthma with pediatric pulmonology follow-up in CHSJ. ‘Healthy Group’ (HG): children attending to routine appointments in USF-São Bento. Caregivers that refused to participate or did not understand the study information were excluded. Also, institutionalized children were excluded. In the healthy group, children with any chronic disease or chronic medication were excluded.

Oral and written information about the study was given to all participants, as well as an informed consent form. Confidentiality was assured. The Ethics Committee of CHSJ, Porto, Portugal, approved this study.

6 Instruments and data collection

Data collection was performed between September 2015 and March 2016 by a questionnaire to caregivers. This questionnaire was based on the Portuguese version of Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI), after authorization of MAPI Research Trust, which holds the distribution rights for the ZBI 13. The ZBI is a Likert-type questionnaire with 22-items (full-form) ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (Nearly always). The total score is given by the sum of each item score and the results range from 0 to 88 points, higher scores indicating a higher burden perception. Similar to other authors we considered that there is little or no burden when score was 0-21, mild to moderate burden for scores 21-40, moderate to severe burden for scores 41-60 and severe burden for scores 61-88 14-18.

We also included questions on socio-educational factors, such as caregivers' age, profession, level of instruction, lodging, number of children and variables related to children and their health: age, diagnosis, age at diagnosis and type of treatment needs. Family Graffar classification was calculated and categorized, the families with the lowest scores (class I and II) belong at the high level of well-being whereas the families in relative, extreme or critical poverty have higher scores (class III, IV and V) 19 .

In the AG questionnaire we also assessed level of asthma control by using the Control of Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma Test for children (CARAT Kids) 20. Caregiver and their respective children had completed the CARAT Kids questionnaire. Uncontrolled asthma was defined as CARAT Score ≥ 5.

7 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23 (SPSS IBM, New York, NY, USA). Categorical variables were described using frequencies and compared with Pearson’s chi-squared test. All the continuous variables had a non-symmetrical distribution, and were described using median. Mann-Whitney U Test was used to compare medians and Pearson correlation was used to compare two continuous variables. We used multivariate logistic regression analysis to compare the ZBI Score between the three groups of the study, adjusting for possible confounders. Results were expressed as Odds Ratio (OR) and with 95% of confidence interval (95%CI). The significance level was defined as p<0.05.

8 RESULTS

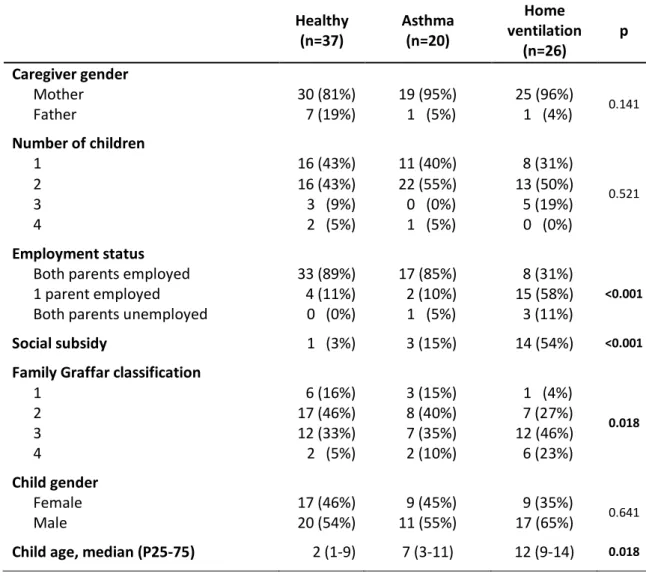

The figure 1 shows the participants’ flowchart. We completed 83 questionnaires of parents who were taking care of children under long-term home ventilation (n=26), with asthma (n=20) or healthy (n=37). The participants’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Eighty-nine percent of caregivers were mothers and the mean age of caregivers was 39 years (minimum-maximum: 20-52). In most cases both parents were employed, with the exception of the HVG where, from a total of 26 women, only 8 were still working.

The caregivers were responsible for the care of 83 children, of whom 48 were boys (58%).

In the HVG there were significantly more caregivers that reported unemployment status in at least one parent (HVG: 69%; AG: 15%; HG: 11%) and social subsidy (HVG: 54%; AG: 15%; HG: 3%). Also, family Graffar classification was significantly higher in HVG (median of 3 in HVG; 2 in AG and 2 in HG.)

The clinical characteristics of HVG are summarized in Table 2. The most common underlying condition among the patients’ sample at HVG were congenital malformations (23%), followed by inborn errors of metabolism (19%). In HVG, 70% had non-invasive ventilation and 30% invasive ventilation; 77% were under nocturnal ventilation, 15% on 24-hour ventilation, and 8% with nocturnal plus a minimum of 4 hours ventilation during the day. Daycare help in child caring was present in only 35% of the HVG and in 67% was given by a

9 relative. Taking in account 81% of the children who have an incapacity certificate, 57% had 90% or more of incapacity.

In the AG, the level of uncontrolled asthma was 55%. Caregivers’ burden

In the HVG, 88% of caregivers have feeling of burden; of these, 70% reported mild to moderate burden, and 30% reported moderate to severe burden. In the AG, 30% of caregivers reported mild to moderate feeling of burden, and 70% reported minimal or no burden. In the HG, 18% of caregivers reported mild to moderate burden, and 82% minimal or no burden.

In the HVG, the disease type, medication use, gastrostomy, physiotherapy, daycare help and incapacity certificate were not associated with differences in ZBI Score. In turn, in the HVG, caregiver burden was associated with caregivers' age (r2=0.228; p= 0.014) and employment status (p=0.041), but not with the other assessed socioeconomic factors (Table 3).

Caregivers’ feeling of burden was significantly higher in the HVG when compared with the HG (OR, 1.36, 95%CI 1.02-1.81) or the AG (OR, 1.24, 95%CI 1.05-1.45). There were no differences in ZBI Score between the HG and AG (Table 4). Also, in AG there was no association of asthma level of control and ZBI Score.

10 Discussion

Our study has demonstrated that the majority of caregivers (88%) of children under long-term home ventilation felt a significant burden; in a third of cases this burden was moderate to severe. Interestingly, the feeling of burden in this group was associated with the age of the caregiver and with the employment status. We also showed that caregivers of children in HVG had significant higher burden when compared with caregivers of children in AG or HG.

Our findings in HVG may reflect the absence of daily home nursing care in our population, imposing to the caregivers the responsibility of paying attention to the technical support, besides of caring for children that already have chronic complex disorders.

The previous studies that addressed the burden of caregivers of long-term home ventilated children were conducted in countries where care assistance from health care or home nursing services are available and funded by their governments, but direct comparison is not possible as they were mostly done on a population of children invasively ventilated, or presenting neuromuscular disease, or the information was obtained by structured interviews and not quantified 8,21-23.

In our group only 30% of the children were ventilated invasively and 77% were ventilated only during the night, so we were expecting a lower level of burden. The majority of children under long-term home ventilation (81%) had an incapacity certificate issued by the health authorities, and the level of incapacity was equal or superior to 90% in 57% of cases, reflecting severe limitations. Published evidence showed that the level of impairment may be a predictor of

11 caregiver's burden, because a child with more impairment, or a lower level of functioning, is likely to require more support from the caregiver 14.

Our results in caregivers of HVG were similar to those reported by those of children with Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophy 24 and traumatic brain injury as assessed by ZBI Score 17. In turn, we found a higher burden than in caregivers of children with mental health problems14. This may be explained by the negative outcomes that caregivers of ventilator-dependent children can genuinely experience, such as feeling of distress, frustration and social isolation 8

.

In the HVG we have found a higher burden, comparatively to caregivers of children with asthma. Our results on uncontrolled asthma were similar to those described in the Portuguese population 25. In contrast with Pedraza et al., that have found a higher burden in caregivers of children with uncontrolled asthma, when compared with children with controlled asthma, we have found no relation between burden and level of asthma control 6.

Similarly to other studies, we have found no association between burden and caregiver’s gender, socioeconomic status, number of children, gender or age of the child, duration of illness or the diagnosis 6,14,15,24. However, in contrast to other studies, we have found a positive association between level of burden and caregivers' age in our HVG.

Although most studies did not find an association between burden and employment status, we also found an association between these two variables in the HVG 6,14,15. A possible explanation may be the prevalence of a high unemployment rate in our sample. In fact, caring for a child with special needs

12 reduces the extent to which work is feasible, especially when there is no nursing daily support, resulting in lower overall income and in higher financial burden 2. This study has some limitations that should be taken in consideration. The ZBI has originally been designed to assess the feeling of burden by caregivers of elderly people; however it has already been used in pediatric populations, to evaluate the feeling of burden of parents of children with chronic diseases 6,7,14-17,24,26

. The transversal nature of this study limits the ability to draw conclusions of causational or directional nature. Our results are based on a population living in a specific region within the country, which limits its external validity in the general population. Another limitation is the difference of the median age between the groups; we can speculate that, if this had an effect on the level of burden, this should go in the opposite direction, as caring for a younger child is usually more time consuming and may have negative effects on the sleep time and quality of caregivers; however, we adjust our estimates for the age of children when comparing the ZBI Score of the three groups. The small sample size of our population is also a limitation.

In conclusion, our study showed that feeling of burden among caregivers of children under home ventilation support is high, in a country where care’s assistance from health care or home nursing services are not available. Despite the above mentioned limitations, these results are especially important not only for physicians who care for children with special needs but also for policy makers who can provide funding to reduce the burden of these families.

13 References

1. Raina P, O'Donnell M, Rosenbaum P, Brehaut J, Walter SD, Russell D, Swinton M, Zhu B, Wood E. The health and well-being of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics 2005;115(6):e626-36.

2. Brehaut JC, Kohen DE, Garner RE, Miller AR, Lach LM, Klassen AF, Rosenbaum PL. Health among caregivers of children with health problems: findings from a Canadian population-based study. Am J Public Health 2009;99(7):1254-62.

3. Schulz R, Sherwood PR. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Am J Nurs 2008;108(9 Suppl):23-7; quiz 27.

4. Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. Jama 1999;282(23):2215-9.

5. Miravitlles M, Pena-Longobardo LM, Oliva-Moreno J, Hidalgo-Vega A. Caregivers' burden in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015;10:347-56. 6. Pedraza AM, Rodriguez-Martinez CE, Acuna R. [Initial validation of a scale to measure

the burden for parents/caregivers of children with asthma and factors associated with this burden in a population of asthmatic children]. Biomedica 2013;33(3):361-9.

7. Sampson NR, Parker EA, Cheezum RR, Lewis TC, O'Toole A, Zuniga A, Patton J, Robbins TG, Keirns CC. "I wouldn't look at it as stress": conceptualizations of caregiver stress among low-income families of children with asthma. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2013;24(1):275-88.

8. Wang KW, Barnard A. Caregivers' experiences at home with a ventilator-dependent child. Qual Health Res 2008;18(4):501-8.

9. Meltzer LJ, Sanchez-Ortuno MJ, Edinger JD, Avis KT. Sleep patterns, sleep instability, and health related quality of life in parents of ventilator-assisted children. J Clin Sleep Med 2015;11(3):251-8.

10. Cancelinha C, Madureira N, Macao P, Pleno P, Silva T, Estevao MH, Felix M. Long-term ventilation in children: ten years later. Rev Port Pneumol (2006) 2015;21(1):16-21. 11. Graham RJ, Fleegler EW, Robinson WM. Chronic ventilator need in the community: a

2005 pediatric census of Massachusetts. Pediatrics 2007;119(6):e1280-7.

12. Racca F, Berta G, Sequi M, Bignamini E, Capello E, Cutrera R, Ottonello G, Ranieri VM, Salvo I, Testa R and others. Long-term home ventilation of children in Italy: a national survey. Pediatr Pulmonol 2011;46(6):566-72.

13. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 1980;20(6):649-55.

14. Dada MU, Okewole NO, Ogun OC, Bello-Mojeed MA. Factors associated with caregiver burden in a child and adolescent psychiatric facility in Lagos, Nigeria: a descriptive cross sectional study. BMC Pediatr 2011;11:110.

15. Kim KR, Lee E, Namkoong K, Lee YM, Lee JS, Kim HD. Caregiver's burden and quality of life in mitochondrial disease. Pediatr Neurol 2010;42(4):271-6.

16. de Moura MC, Wutzki HC, Voos MC, Resende MB, Reed UC, Hasue RH. Is functional dependence of Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients determinant of the quality of life and burden of their caregivers? Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2015;73(1):52-7.

17. Perrin PB, Stevens LF, Sutter M, Hubbard R, Diaz Sosa DM, Espinosa Jove IG, Arango-Lasprilla JC. Exploring the connections between traumatic brain injury caregiver mental health and family dynamics in Mexico City, Mexico. Pm r 2013;5(10):839-49.

18. Ferreira F PA, Laranjeira A, Pinto AC, Lopes A, Viana A, Rosa B, Esteves C, Pereira I, Nunes I et al. Validação da escala de Zarit: sobrecarga do cuidador em cuidados paliativos domiciliários, para população portuguesa* Validation of the Zarit’s scale (“Zarit Burden Interview”) for the Portuguese population in the field of domiciliary palliative patient care. . Cadernos de Saúde 3(2):13-19.

14 19. Graffar M. Une methode de classification sociale d'echantillons de population. Courrier

1956;VI:445-449.

20. Linhares DV, da Fonseca JA, Borrego LM, Matos A, Pereira AM, Sa-Sousa A, Gaspar A, Mendes C, Moreira C, Gomes E and others. Validation of control of allergic rhinitis and asthma test for children (CARATKids)--a prospective multicenter study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2014;25(2):173-9.

21. Dybwik K, Tollali T, Nielsen EW, Brinchmann BS. "Fighting the system": families caring for ventilator-dependent children and adults with complex health care needs at home. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:156.

22. Mah JK, Thannhauser JE, McNeil DA, Dewey D. Being the lifeline: the parent experience of caring for a child with neuromuscular disease on home mechanical ventilation. Neuromuscul Disord 2008;18(12):983-8.

23. Mah JK, Thannhauser JE, Kolski H, Dewey D. Parental stress and quality of life in children with neuromuscular disease. Pediatr Neurol 2008;39(2):102-7.

24. Kenneson A, Bobo JK. The effect of caregiving on women in families with Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy. Health Soc Care Community 2010;18(5):520-8. 25. Ferreira-Magalhaes M, Pereira AM, Sousa AS, Morais-Almeida M, Azevedo I, Azevedo

LF, Fonseca JA. Asthma control in children is associated with nasal symptoms, obesity, and health insurance: a nationwide survey. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2015.

26. Calderon C, Gomez-Lopez L, Martinez-Costa C, Borraz S, Moreno-Villares JM, Pedron-Giner C. Feeling of burden, psychological distress, and anxiety among primary caregivers of children with home enteral nutrition. J Pediatr Psychol 2011;36(2):188-95.

15 Figure 1 - Participants’ flowchart

16 Tables

Table 1 – Participants' characteristics – n (%).

Healthy (n=37) Asthma (n=20) Home ventilation (n=26) p Caregiver gender Mother 30 (81%) 19 (95%) 25 (96%) 0.141 Father 7 (19%) 1 (5%) 1 (4%) Number of children 1 16 (43%) 11 (40%) 8 (31%) 0.521 2 16 (43%) 22 (55%) 13 (50%) 3 3 (9%) 0 (0%) 5 (19%) 4 2 (5%) 1 (5%) 0 (0%) Employment status

Both parents employed 33 (89%) 17 (85%) 8 (31%)

<0.001

1 parent employed 4 (11%) 2 (10%) 15 (58%) Both parents unemployed 0 (0%) 1 (5%) 3 (11%)

Social subsidy 1 (3%) 3 (15%) 14 (54%) <0.001

Family Graffar classification

1 6 (16%) 3 (15%) 1 (4%) 0.018 2 17 (46%) 8 (40%) 7 (27%) 3 12 (33%) 7 (35%) 12 (46%) 4 2 (5%) 2 (10%) 6 (23%) Child gender Female 17 (46%) 9 (45%) 9 (35%) 0.641 Male 20 (54%) 11 (55%) 17 (65%)

17 Table 2 – Home ventilation disease characteristics - n(%).

Home ventilation (n=26) Disease Cerebral palsy 2 (8%) Neuromuscular 4 (15%) Congenital malformations 6 (23%) Inborn errors of metabolism 5 (19%)

OSA* 4 (15%) Traumatic 1 (4%) Others 4 (15%) Medication use 19 (73%) Gastrostomy 10 (39%) Physiotherapy 19 (73%) Daycare help 9 (35%) Incapacity certificate 21 (81%)

18 Table 3 – Univariate analysis for Zarit Score (ZS) in each group.

Healthy Asthma Home

ventilation Caregiver, ZS median (IQR)

Mother 15 (13) 19 (10) 29 (18)

Father 9 (3) - -

Age of caregiver, r2 0.003 0.153 0.228*

Number of children, r2 0.044 0.027 0.001

Graffar classification, r2 0.029 0.052 0.115

Employment status, ZS median (IQR)

Both parents employed 14 (12) 18 (8) 24 (6)#

One or both unemployed 6 (9) 25 (-) 34 (17) Social subsidy, ZS median (IQR)

No - 18 (8) 28 (19)

Yes - 25 (-) 32 (18)

Child gender, ZS median (IQR)

Female 13 (10) 18 (9) 38 (17)

Male 15 (14) 20 (14) 28 (13)

Age of child, r2 0.052 0.045 0.026

Mann-Whitney U Test was used for comparison of ZS by categorical factors; Spearman Test was used for comparison of ZS with continuous factors.

Bold values show statistical significant differences. *p=0.014; #p=0.041

19 Table 4 – Zarit score comparison between the three groups

Healthy (n=37) Asthma (n=20) Home ventilation (n=26) p Median 13 (9-19) 19 (13-22) 30 (24-42) <0.001 Crude OR

Healthy vs. Home ventilation 1.25 [1.12-1.41] <0.001

Healthy vs. Asthma 1.07 [0.99-1.15] 0.107

Asthma vs. Home ventilation 1.20 [1.07-1.34] 0.001 Adjusted OR*

Healthy vs. Home ventilation 1.36 [1.02-1.81] 0.037

Healthy vs. Asthma 1.04 [0.95-1.13] 0.434

Asthma vs. Home ventilation 1.24 [1.05-1.45] 0.009

i Anexo I - Manuscript Guidelines Pediatric Pulmonology

Edited by: Thomas Murphy Print ISSN: 8755-6863 Online ISSN: 1099-0496 Frequency: Monthly Current Volume: 49 / 2014

ISI Journal Citation Reports® Ranking: 2012: Pediatrics: 25 / 121; Respiratory System: 27 / 50

Impact Factor: 2.704

MANUSCRIPT GUIDELINES Original Research Articles

Original Research Articles should follow the standard structure of abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and references, and may include up to six tables and/or images when appropriate. Original Research Articles should be limited to 3,500 words (not including the abstract or references). The abstract should not exceed 250 words, and references should be limited to forty (40).

COMPONENTS OF ARTICLES/FILE PREPARATION

Please make note of the following when preparing your submission:

Main Document

All manuscript types must include a title page, abstract, text and references in the Main Document. Standard, double-spaced manuscript format, in 12 point font is requested. Number all pages consecutively.

Title page: The title should be brief (no more than 100 characters in length including spaces) and useful for indexing. All authors' names with highest academic degree, affiliation of each, but no position or rank, should be listed. For cooperative studies, the institution where research was primarily done should be indicated. In a separate paragraph, specify grants, other financial support received, and the granting institutions (grant number(s) and contact name(s) should be indicated on the title page). If support from manufacturers of products used is listed, assurances about the absence of bias by the sponsor and principal author must be given. Identify meetings, if any, at which the paper was presented. The name, complete mailing address, telephone number, fax number, and e-mail address of the person to whom correspondence and reprint requests are to be sent must be included. Keywords should also be noted on the title page. For usage as a running head, provide an abbreviated title (maximum 50 characters) on the bottom of the title page.

Summary/Abstract: In accordance with the structure of the article, with or without separate headings, outline the objectives, working hypothesis, study

ii design, patient-subject selection, methodology, results (including numerical findings) and conclusions. The Summary should not exceed the word counts outlined above. If abbreviations are used several times, spell out the words followed by the abbreviations in parentheses.

Acknowledgements: Technical assistance, advice, referral of patients, etc. may be briefly acknowledged at the end of the text under "Acknowledgements." Informed Consent: Informed consent statements, if applicable, should be included in the Methods section.

References/citations: References may be included at the end of your text, or uploaded as a separate file. Ensure your references are up to date, and include a critical selection from the world literature. References should be prepared according to CSE (Council of Science Editors) citation-sequence style. Refer to the Scientific Style and Format: The CSE Manual for Authors, Editors, and Publishers, 8th edition (University of Chicago Press). Start the listing on a new page, double-spaced throughout.

Number the references in the sequence in which they first appear in the text, listing each only once even though it may be cited repeatedly.

When citing a reference in the text, the style advocated by CSE suggests numbers appear in superscript, and appear before punctuation marks (commas or periods). In the citation-sequence system, sources are numbered by order of reference so that the first reference cited in the paper is 1, the second 2, and so on. If the numbers are not in a continuous sequence, use commas (with no spaces) between numbers. If you have more than two numbers in a continuous sequence, use the first and last number of the sequence joined by a hyphen, for example 2,4,6-10.

In the references, list the first ten authors of the cited paper. If there are more than ten authors, list the first 10 authors followed by 'et al'.

Journals' names should be shown by their abbreviated title in Index Medicus. Manuscripts in preparation or submitted for publication are not acceptable references. If a manuscript "in press" is used as a reference, a copy of it must be provided with your submission.

Sample references: Standard journal article

Landau IL, Morgan W, McCoy KS, Taussig LM. Gender related differences in airway tone in children. Pediatr Pulmonol 1993;16:31-35.

Book with authors

Voet D, Voet JG. 1990. Biochemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 1223 p. Book with editors

Coutinho A, Kazatch Kine MD, editors. Autoimmunity physiology and disease. New York. Wiley-Liss; 1994. 459 p.

iii Chapter from a book

Hausdorf G. Late effects of anthracycline therapy in childhood: evaluation and current therapy. In: Bricker JT, Green DM, D'Angio GJ, editors. Cardiac

toxicology after treatment for childhood cancer. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1993. p 73-86.

For a book reference only include the page numbers that have direct bearing on the work described.

Keywords: On the title page, supply a minimum of 3 to 5 keywords, exclusive of words in the title of the manuscript. A guide to medical subject heading terms used by PubMed is available at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/MBrowser.html

Abbreviations: Define abbreviations when they first occur in the manuscript and from there on use only the abbreviation. Whenever standardized abbreviations are available use those. Use standard symbols with subscripts and superscripts in their proper place.

Drug names: Use generic names. If identification of a brand name is required, insert it in parentheses together with the manufacturer's name and address after the first mention of the generic name.

Eponyms: Eponyms (diseases or biologic entities named for persons) should not be used when standard descriptive terminology is available. Examples include club cells (formerly known as Clara cells); and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Wegener's granulomatosis). It is permissible to use the eponym in parenthesis at the first mention of the term in cases in which the eponym is still in common use.

Formatting Specific to Original Research Articles: Divide article into: Title Page, Summary/Abstract, Introduction, Materials and Methods, Results, Discussion, and References, starting each section on a new page. All methodology and description of experimental subjects should be under Materials and Methods; results should not be included in the Introduction. Please ensure the following appears in the appropriate section of your manuscript:

a concise introductory statement outlining the specific aims of the study and providing a discussion of how each aim was fulfilled;

a succinct description of the working hypothesis;

a detailed explanation of assumptions and choices made regarding study design and methodology;

a description of the reasons for choosing the type and number of experimental subjects (patients, animals, controls) and individual measurements; if applicable, information about how and why the numbers may differ from an ideal design (e.g., the number required for achieving 90% confidence in eliminating Type II error);

specifics about statistical principles, techniques and calculations employed and, if applicable, methods for rejecting the null hypothesis; a concise comparison of the results with those of conflicting or

iv a brief summary of the limitations of the scientific methods and results;

and

a brief discussion of the implications of the findings for the field and for future studies.

Tables

Tables should not be included in the Main Document, but submitted as a separate DOC or RTF file. Number tables with Arabic numbers consecutively and in order of appearance. Type each table double-spaced on a separate page, captions typed above the tabular material. Symbols for units should be used only in column headings. Do not use internal horizontal or vertical lines; place horizontal lines between table caption and column heading, under column headings, and at the bottom of the table (above the footnotes if any). Use footnote letters (a, b, c, etc.) in consistent order in each table. All tables should be referred to in the text. Do not submit tables as photographs and do not separate legends from tables.

Images

Image files must be submitted in TIF or EPS (with preview) formats. Do not embed images in the Main Document. Number images with Arabic numbers and refer to each image in the text. The preferred form is 5 X 7 inches (12.5 X 17.5 cm). Print reproduction requires files for full color images to be in a CMYK color space.

Please note authors are encouraged to supply color images regardless of whether or not they are amenable to paying the color reproduction fees. Color images will be published online, while greyscale versions will appear in print at no charge to the author. See Author Charges below.

Journal quality reproduction requires grey scale and color files at resolutions yielding approximately 300 ppi. Bitmapped line art should be submitted at resolutions yielding 600-1200 ppi. These resolutions refer to the output size of the file; if you anticipate that your images will be enlarged or reduced, resolutions should be adjusted accordingly.

Lettering on images should be of a size and weight appropriate to the content and the clarity of printing must allow for legibility after reduction to final size. Labeling and arrows on images must be done professionally. Spelling, abbreviations, and symbols should precisely correspond to those used in the text. Indicate the stain and magnification of each photomicrograph. Photographs of recognizable subjects must be accompanied by signed consent of the subject of publication. Images previously published must be accompanied by the author's and publisher's permission.

Image legends should be brief, and included as a separate DOC file under the heading: "Image Legends." When borrowed material is used, the source of the image should be shown in parentheses after its legend, either by a reference number or in full if not listed under References.

v Anexo II - Parecer Comissão de Ética