•

" " #,FUNDAÇÁO

" "

GETULIO VARGAS

EPGE

Escola de Pós-Graduação em Economia

"Dennis Robertson and the Natural Rate of

UneD1ployD1ent Hypothesis"

~

Prof. Mauro Boianovsky (UnB)

(co-autoria com:

J

ohn R. Presley)

LOCAL

Fundação Getulio Vargas

Praia de Botafogo, 190 - 10° andar - Auditório

DATA

02/12/98 (4

afeira)

HORÁRIO

16:00h

..

DE:'íNIS ROBERTSOi'i

.-\!'iD

THE :"i.-\ Tt R.-\ L R.-\TE

OF LiNE.\lPLOYi'rlE:"iT HYPOTHESIS

J

\buro 13oi:lno\:-;ky

r

niversilbdc de Brasilia.John R Preslcy Loughborougn {' ninrsir:

:\ugust 1995

:\1so note: .-\ version of this papcr W:1S prescnted :It thc l'S

~ \ ~r. !yl;niH""" of Economics Socictv Confcrencc. {' nivcrsir:' 01' Quchcc

j\'-JI\1~ .. ..

at ;\'Iontrcal. ,\lontrcal • .JUIIC 191JS.

··i

'

..

o

·i

.I

i

Dennis Robertson and the Natural Rate of Unemployr.;ent o-fy.oothesis

Mauro 8oianovsky Universidade de Brasilia

John

R.

PresleyLoughborough University

I. introduction

One of the striking features of Oennis Rccertson's 191 S Study of Industriaí F!uctuation is the attempt to approach cyc:ical flucwations in output and emplcyment

as the outcome

ar

the rational reactions of prcducers to changes in real costs and demand conditions in market clearing economies. Throughout most of the book.Robertson uses the income-Ieisure choice - encapsuiated by the ccncept of

"elasticity of demand for income in terms of effort" - to show how sectoral real shocks

(such as sector specific technological changes and/or an increased bounty of nature)

are able to bring about changes in the supply of effort and, through that. produce

aggregate fluctuations in output (see Fellner 1952 (1992]. pp. 142-43: Danes, 1985, pp. 106-13: Presley and Sessions. 1997). It is one of the purposes of the present paper to discuss Robertson's extension of the income-Ieisure analysis to a monetarj

economy in the closing chapters of the Study. He put forward the view that a

proportional rise in the price levei élnd money-wages generates a terr:porarj increase

in aggregate output, as producers tend to mistake the '~ominal change for hígher real

wages and higher relative prices (and vice-versa for falling prices and

money-wages). Robertson made it clear that the volume of production 'Nould return to its

initiallevel as soon as the "illusion" was discovered.

This particular form of association between price and wage ievel changes ar.d

2

into the background. This has to do in part with Robertson's decision to focus in the mid 1920s on the relation between the saving-investment process and the credit mechanism, but it also reflects the increasing attention given to money wage-stickiness in the period around the publication of J.M. Keynes's General Theory. Also in Cambridge, D.G. Champernowne (1936) suggested that the main difference between Keynes and the "classics" was the inclusion by the former of the nominal wage in the labour supply function, which was explained by the temporary inability of workers to fully realize changes in the price leveI. Despite Champernowne's acknowledgement of discussion with Robertson and A.C. Pigou, the notion that the supply of labour is a positive function of perceived real wages was not important for Robertson's interpretation of "Keynesian macroeconomics" in the 1930s and after (the same applies to Pigou, for that matter). Instead, Robertson discussed critically Keynes's claim that a reduction in nominal wages will not reduce real wages unless the rate of interest falls in the processo

During the 1950s Robertson became increasingly criticai of the "Keynesian policy" of "full employment". He pointed out that the full employment policy of the British government was the main factor behind the process of "creeping inflation", which could quickly turn into an accelerating price rise. In several papers and in the third part of his Leclures on Economic Principies, Robertson maintained that if the government announced a stable price levei as an objective of economic policy and fixed the money supply accordingly, money-wages would stop rising without any significant increase in unemployment, as trade unions would take monetary policy into account when setting new wage contracts. This point of view was incorporated into the first report of the Council on Prices, Productivity and Income (the "Cohen Council", of which Robertson was a prominent member) issued in February 1958, and elicited strong criticism from the trade unions and a few economists. especially Nicholas Kaldor. A few months after the report, A.W. Phillips's article on the statistical relation between unemployment and money-wages came out in

Economica. In his reaction to Phillips's results in the following year. Robertson

reaffirmed his view that a fali in aggregate demand, if anticipated by wage-earners .

.. !~.-.'~. "~"~-:'.:~!':~.

.!e-,",:, ""-.,:

would bring about a reduction in the rate of increase of money-wages. so that no

massive increase of unemployment would be required.

Robertson's perspecti'/es in the 1 9 15 Study and in the 1950s on the neut~aiiiy

cf aniicipated price :evel changes are c!early remmiscer.t of the "natural ;2:e cf

unemployment hypotr~sis" (NRUHl formuiated by Friecman (1968) are ?heips

(1967, '1968) and further elaboraled

oy

Lucas (1972). The ;nain propositior. cf NRUH :s that inflation is neutra! for the equilibrium path of emp!c~:ment and out;:ut. 'Nhich.as Phelps (1995. p. 16) has pointed out. shouidbe imer;:::reted as a set ofaxicms

instead of a substantive model of the determination of the le'/el of employment (this

can be illustrated by the differences between lhe mcdels advanced by Friedman.

Phelps and Lucas, among others).l The present paper seIs out to discuss hov} the

NRUH was depioyed by Robertson at different stages of his extended contí:buticns

to business cycle theor;.

11. i'vlonev lIIusion and Fiuctuations

Monetary factors are not considered in the Study until chapter three of the last

part of the book. Robertson started by examining the influence of money during the

boom, which had been previously described as an increase in investment

determined by an upward "revision of the marginal utility of construction goods"

(1915, p. 157).2Increased investment is accompanied by a larger money supply and

higher prices, which induce producers to enlarge the scale of production beyond the

point decided by the original effect of, e.g., an invention on the suppiy of effort.

An increased volume of currency, whether due to an increased confidence in

the breasts of bankers, or to an increased supply of metallic gold. 'Nill tend. it

need hardly be argued, to raise the general le'/el of prices. If ail prices

(including wages) were equally affected. the resu!t would prcbacly

te

a general increase in production beyond the poim which is in fac: moreadlJaotageous: for it seems to be a natural tendency ·)f

e'ler;

man te supposethat the product which he seUs will be more raoidly and deeply affected by any

current price-movement than the products which he buys either for personal

consumption or for industrial use (p. 2i2: see also pp. 239--W).

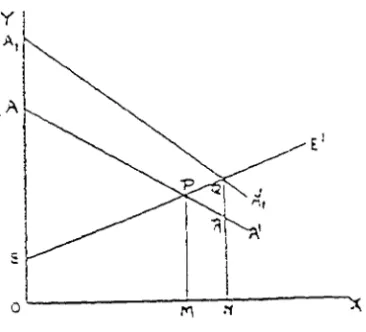

Robertson illustrated his argumert with a diagramo of lhe same :,:nd used in the firs:.

"real' part of the beok (cf. pp. 132. 202 aí,C 20-1; In the rjiagíam. reorcduced beicw as figurei, "units of -=ffort" are '71easurec 3:0í,g the aCSCissa and'units of utiiit!"

along the ordinate. EE' is t~e'CL:r'Je cf marginal disutiiit'f

or

effo;-:'. while A~' :::r.c. A :A'lare, í8spectively. the CUí,;es of "act~ai" and ., antic:pated marginal produc::'li:y

of effor.:·. pr:ces having risen in the i3tio A;,J. " AO (pp. 212-13). 8ecause cf the effect of the price levei rise on anticipated marginal producti'Jit'f. t'ie tetal volume of error:

expenced will be ON, instead 0f Ol'vl. and total utility enjoyec ..viII be AONR, which is

!ess than total utility if marginal prcductivit'j of errort hac in fac: gene up (A tONO).

but more than total utility at the original equilibrium (AOMP). The whole exercise ;s

based on the crucial assumption - whicn is only implied by Robenson in this case.

out is explicitly made in the "real" chapters of the Study - that the effort-demanc:! for

anticipated commodities is elastic, that is. the supply curve of effort (frem workers

and businessmen) is positively sloped (see Presiey. 1979, pp. 41-45: Presiey and

Sessions, 1997: Robbins, 1930). This explains why the curve AA' shifts to

A1A'lwhen :he effort price of income falls (cf. Robertson, 1915, p. 132). Under this

assumption, the (wrongly) anticipated increase of relative priees and real wages wiii

bring about a larger aggregate output.3

Robertson was at pains to emphasise that :he confusion between absoiute

and relative prices is temporar;:

So far as the gain from rising ;::rices is pureiy illusorj, t:',e fact is bound saoner

or later to be discolJered: the anticipated producti'Jity will fali till it coríesponcs

with the real productivity of effort. and the volume of production suffer

res~rictien. [Footnote: If. howe'ler. the working-class reaiisation of errar oc:::urs

after the point at which the effort-demand for anticipated commcdi,ies

becomes inelastic, it will 'ler; possibly set up a íe'lerSe movement towar:::s an

YI

A'

I

A

O'---M~~~~---X

FiGURE 1 (Robertsor;, 1915. p. 212: ~nits cf er.cí': alcr,G

oX.

cf L.:tíil~/2.icr.g 2'(\o

ti

... j I

: ... 1 B

;

1'~

~I

i ~,

, I~!

I

!

t,·... ,"7·'1

I.

•

The Clrcumstances menticned in the fcctnote were iepresented by Robertson in the

diagram reproduced as figure 2 below. In the dtagram. A~' and a:::' are. respectively,

the curves of anticipatec and ac~uai "ccmmocity prccuctiljity of ei'fort": 8S' and 00'

are. respectively, the CUf"Jes of antic:pated and actual's3tisfac~ion 2roducttvity

0r

effcrt" Asscming that the furtheí raisir.g af ~A' to..',',.'\': IC','iers 35 tc B ~5'í until it

falls beiew bb' , ,Oroduction "ha'Jing been restric:ec frem ~M' ,o::"M: '.Viii 0n ~he

reaiisation of error be exp2 -;ded to OM: ., í,;;p. 2 'ri -~ 3:;,!

After the upper turnlng paim - l.:sual!y explaincc cy ar. c'isí-f::r:x!ucticn of fixec

capital (see pp. 180-89; Goadhart and P~esley. íS9J.. pp. 233-..1\ -the cemand and supply of credit decline, bringing accut a falling pric2 levei. with anaiegous effects cr:

prcduction: "This shortage oi currency. Gombined with the in{!ux of ,he new suppíies

cf consumab!e goods. leads to a prcgressive fali in r.:oney ;:;rices ;'.5 the diljergence between the real and the anticipated productivity cf effert operated during the boem to stimulate prcduetien, se now it opeí::tes to restrain it" (p. 225: see also ;:l. 241). It shauld be noted, however, that the analysis applies now basically to the suppíy of

errart by businessmen only. as the increase in unemployment dUíing the depressien

is incerpreted by Robertson as "in'leiuntaf"j" (p. 209. n . .:1.), which he explained (apart from wage stickiness) by the fact that in those perieds the elasticity of effort-demand

for ali commodities (including instrumental goods) is higher fer businessmen than for

workers. "F ar those reasons it is plain that the scale of produc:ion which commends

itse!f to the business class may be smailer than that which corr,mends itse!f to the

working classes" (pp. 209-10: see also [1926J 1949. pp. 21-22).5 .~ithough Robertson stressed once more the "illusory" character oi the disability impased by a falling price ie'Jei. he did nat. in contrast with the upturn, rr,ake c!ear lhat the illusion wouid ce

oniy temporar!.

Robertson (1915) also applied the notion cf "monetar; misapprehension" to the firm's inlJentory problem (pp. 15ô. 210, 241. 248). He 'Nas searching for an e:<planation of v/hy during the business relJi'lal gecds '.vhich had ;:;re'lieusly oeen neld

•

While a general rise in the exchange value of ali consumable goods in terms

of each other ;·s c:eariy impossibie. it is perfectly possible that eacn group of

producers cr awners should expect a rise in the value of its own prccL:ets. and

consequently be willing to witheraw them irom store. Jvloreo'ier. :ne existenee

of a monetar;/ eeonomy affares 3 rr:echanism

::y

'Nhic~ sue;'. an eX;::2ctaticnmay be raisec! simültaneously in ;nany trades (.o. 156).

The accumulation in stOí8S of a "considerabie part of what :s actua:l,! crcduced"

during the depression 'Nas important in Robertson's 1915 framework for 'loNO reasons.

lhe first one is that it diminishes the now

cr

geeds available ;or lhe cor.süíT',ction cfwage-earners. which prevenrs the rise in the commodity-produetivity

cf

their effort tean extent that the point at which their effort-demand for income becomes :~e!astic is

not reached (p. 210). ivloreover. the accumulation of stecks of goods ,'Ias inrerpreted

by Robertson as a ma in source of savings te be used later on during :he coom (pp.

236, 248; but see his preface to the 1948 ieprint of the Study. p. xv. for a change of

opinion).

The effeets of the confusion between absolute and relative prices on

produetion can also be found in other accounts of the business cycle prcvided by

Robertson (see "v'oney, p. 139: Banking Policy and the Price LeveI. p. 39: Lectures.

pp. 411 and 415). but the mechanism is not spelled out.ô In his Banking ,ooiicy ... the

matter was discussed as part of Robertson's distinction between "appropriate"

(brought about by real factors such as inventions etc) and "inappropriate" (which are

c:aused mainly by monetary factors and result in a subsequent re'/ersal) fluctuations

of output ([1926J 1949. chap. li and IV: Fellner [1952J 1992. pp. 143-4J. Laidler.

1995. p. 156). He explained that a temporarf rise of the price levei should ::e part cf

the incentive to increased output when productivity rises in the bocr.1 out that

monetar'j and credit policy should avoid the "secondar; pnenomena

cr

trade expansion" (and the symmetric "secondary fali") caused by a further :r.erease ofprices set up by a reduetion in the demand for "hoarding" and Cf ar. enlargec

output [( 1926) 1949, chap. 'li; cf. \ 1922, 1928) 1948, pp.15ô-59, and 1963a. 4. 1 '1-12).

So f:Jr as the induce!71ents :0 a prcducer ,0 e:<pand (or contract) outp'~t 3,2

clothed in ;he form of an inc~2ased (ar diminished) stream of money demar.,.;

lhey are in many cases par-:!y iilusory: fer :;:2 rise (or :all) in price turns out :-:c,

to

ae

confined to the preGue! \~v.,lich he seils. bu! to affect alsc in ;reat2: -:1less degree the product whlc:-, he buys. r.ence. the aite:ations ac:t..!aiiy r.;ace

in the scale of output tene :a 2xceec the appropr:ate alterations ... aiso :na,

monetaf"'j poiicy ... w';1 tend

:0

be. unless :-<e~t weil in control, the most fertiie inthe generation of errer. lhe 3im or monetaf"'j polic,! shoL:ld be te repi2S3

those (fluctuations in the generai ;Jrice-ievei] whicil tend te carri :~e

alterations in output beyond ~he appropriate paim [(1926) 1949, p. 39].

Oespite the importance or'moneta!"'! misapprehensions"' for the poiicy conc!usions cf

Banking Policy ... , Robertson rerrained from discussing the matter

cr "'

errors' :ncetail. on the grounds that "' they ha'/e been so afien and so thoroughly discussecj""

(p. 38). He referred

:0

Lavington (1922) and to 3 passage from Pigou (1920. p. 3.10)about "psychological interdependence" bef:',veen businessmen, but did not menticn

any discussion of the absolute priceirelative price coníusion in the literature, apare

perhaps from a blurred reference to his own treatment in the Study. 7 ,';s a matter cf

fact. however, the paint abaut "'monetary conrusion" in the upswing had been made

by J.S. I'l/Iill in his Principies and in a few other places. Mill [(1848) 1909. p. 55C]

reacted against Thomas AttwOOG's contention that per:ods af rising prices. produced

by a nse af paper currenCf. had always been accompanied by inc,eased

employment of capital and laoour (see Unk. 1950, pp. 19-31. 1.:!9-51) "lI!!:

maintained against Attwood that.

The inducement which. according to ;V1r. Attwood, excited this unusuai arcour in ali persons engaged in ;Jroduction, must nave been the expectations cf

getting more commoc!ities generaily ". in exchange for the prccuc:s of :;;e:,

labaur, and not mereiy more ~iec2s cf par;er. This expectatian. hcwe'íer. !.,us:

have been, by the 'ler;/ ter;;-:s cr the sL:ppcsition, disappointed. since. a!1 ;:Jr'ces

8

being supposed to rise equally, no one was really berter paid for his goods

than before. Those who agree with Mr. Attwood could only succeed in winning

people on to these unwonted exertions by a prolongation of what would in fact

be a delusion.8

As Negishi (1989, pp. 172-76) has pointed out, Mill's reasoning - that it is only while

the "delusion" lasts that increasing money prices can produce an enlarged supply of

effort and, by that, increased output - is fully consistent with the natural rate of

unemployment hypothesis. Negishi suggests that producers and dealers will revise

their expectation of "normal prices" in the face of changing realized prices until the

delusion eventually vanishes (cf. Forget, 1990, pp. 630-31 for a rather different

mechanism that also uses the notion of "normal prices").

Robertson did not refer to Mill in this connection, but the possibility of Mill's

influence cannot be excluded, especially if we bear in mind the long lasting influence

of his Principies on British economics (see also Laidler, 1995, p. 166, for the

suggestion, on these grounds, that Mill could had been a source of inspiration for

Robertson's analysis of forced saving in 1926). It is worth noting, though, that Mill did

not explicitly consider the price expectations of workers.9 Both Mill's and Robertson's

formulations of the effects of "money iIIusion" on production in market-c1earing

economies are c1early reminiscent of the so-called "surprise supply function"

advanced by Lucas (1972). Like Lucas, and in contrast to Friedman (1968), there is

no asymmetry of information between workers and firms in Robertson's approach.

Needless to say, the concept of "rational expectations", and the related notion that

producers would be able to forecast the correct price levei if they knew the money

supply in advance, is not part of Robertson's (or Mill's) framework. Writing during the

gold standard period, Robertson (1915, pp. 228-29) contends that the levei of prices

is decided by largely endogenous changes in bank credit, without a pro-cyclical

partern of the influx of new gold. He suggested that the effect of new gold at the final

stages of the downturn is "purely sedative and medicinal", but pointed to a possible

connection between gold supply and the expected price levei:

.-lIlil7Iíir.-Siii·.-iiTIIi'-iIiII _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ ... .

i

i

I

~~

9

It is possible that the mere existence of large gold reserves and a low rate of

discount leads people to think that prices are about to recover, and so to be

less afraid first of buying other people's goods, secondly of consenting to

immediate actual reduction in the price of their own, which they believe will

only have to be temporary, and thirdly of making for stock (p. 229; italics in the

original).

It was only in the 1950s that Robertson would put forward the view that information

about future money supply is taken into account in new nominal contracts, especially

in the labour market, as we shall see below.

li\. Monev Wages, Keynes and Champemowne

During the 1930s and after Robertson discussed extensively and critically

Keynes's General Theory, with emphasis on the determinants of the rate of interest

and the relation between money wages and aggregate demando His previous

analysis of "money iIIusion" was not mentioned, but the role of mistaken price

expectations by wage-earners was the core of Champernowne's 1936 comparison

between Keynes and the "classics". Champernowne (1936, p. 202, n. 1 and 2)

acknowledged discussion with Robertson on the essential\y temporary character of

the wage-earners' mistake, but made no reference to Robertson's books. In any

event, differently from Robertson (1915, 1926), he implicitly assumed that only

workers are fooled by price levei changes, while firms have correct information.

Champernowne (pp. 203-4) distinguished between "basic" and "monetary"

unemployment, where the former is defined as the rate of unemployment consistent

with labour market clearing when the demand and supply of labour are influenced

only by real wages. "Monetary" unemployment (or over-employment) is due,

respectively, to the fact that workers have "overlooked a recent fali [or rise] in the

cost of living".

10

In so far as these oversights are likely to be repaired eventually, the

monetary-unemployed are likely to lower the money-wage which they

demando We may express this by saying that a period of monetary

unemployment is likely to cause falling money-wage rates, and that a period

of monetary employment is likely to cause rising money-wage rates. In so far

as we can assume that rising and falling money wages will respectively cause

rising and falling real wages, we may conelude that a period of monetary

employment contains the seeds of its own destruction in the form of a

tendency for real wages to rise, whereas a period of monetary unemployment

has in it the seeds of its own destruction, in the shape of a tendency for real

wages to fali (p. 204).

Champernowne's interpretation of the dynamics of the labour market and his

description of the essentially temporary "monetary" unemployment as "Keynesian"

are remarkably elos e to Friedman's (1968: see also 1975, p. 17, for Friedman's

interpretation of Keynes). He lacked, however, Friedman's notion that inflation would

have to accelerate in order to maintain unemployment below the natural (or "basic")

rate (cf. Champernowne, p. 216). In this framework ali markets e1ear, so that

workers supply an amount of labour decided by their perceived real wages.

Deviations frem the "basic" rate of unemployment arise from the temporary failure of

wage-earners to form accurate expectations of the future course of the price levei,

and should be seen as "voluntary" (cf. Champernowne's equations and diagrams on

pp. 211-13; see also Darity and Young, 1995, pp. 15-19). Like Friedman's, it is a

model of departures of the labour force frem its equilibrium path (cf. Phelps, 1995, p.

16).10

Robertson recognized the possibility of a "money illusion" interpretation of The General Theory. In his address on the "Frontiers of Economic Thought" to the Conference of Economic Teachers in 1947, he pointed out that

The original Keynesian theory of employment hung, I believe, on the very old

and respectable peg that there are strong frictions preventing' money-wage

II

there is sometimes room for a little inflation, as I have a note of his [Keyr.es's]

saying in a lecture 35 years ago, "to cheat Trade Unions into being

reasonable·'. [Footnote: Te which, if my notes are correct. in those :ays he

was still cautious enough to add: "Sut this is a short-signted polic/. for ~he ~iS2

cannot be kept secret fore'ler".] . .:\ respectabie flag. but not a ver! strcr:g CGe

-not nearly stíOng enough, in medern times, to cear lhe weight.:f the icea,

hung upcn in lhe first bock of The General Ti7,:Jc r:1. ,hat we can negiect as

being "voluntar(. ando lhererore outside cur main concern, any scraps of

unemployment which may persist after money- wages have begL.in

,0

foi!ewpric8 upwards. So ali that had to 90 pretty quick. and it is nct ciear to '-7,e 'ler

exactly what nas taken its place (quoted by o\tlizen and Pres!ey, 1995. p. S'+{'.

Robertson suggested next that the "money illusion" factor had been replacec ir. Keynesian theory by the contention that "changes of money-wages, whether

upwards or downwards, cannot affect employment except through the de'lious and

uncertain route of the rate of interest" (jbid.: cf. Keynes, 1936, chap. 19). This is the

theme of chapter 9 of part 3 of Robertson's Lectures, which result from his activities

as Professor of Political Economy at Cambridge from 1945-6 until 1956-7. Robertson

(1963a, p. 442) started by assuming what Pigou had called "Keynes's Day Of

Judgment", that is, a zero (or almost zero) rate of interest, nil net investment and

positive saving. If wages are "flexible without a lag", there would be no

unemployment, contrary to the "Keynesian view" that the flexibility would not prelfent

a process of growing unemployment until saving falls 3S a result of reduced income.

If money-wages are still flexible, but with a lag, some unemployment wiil emerge as a

resuit of the fali in aggregate money demand, but the situation will be c:-:arac~erized

by constant unemployment and continuous deflation, ;:ot by increasing "mass

unempioyment" .11 The progressive fali in money inco..-ne will be interrupted by the

endeavour by the community to restore the desired proportion between the real

value of the money stock and real income (that is, the Cambridge k). In the generai case, Robertson (1 :'63a, pp. 444-45) rejected Keynes's c!aim that the schedule of

margir.ll efficiency of capital is given in terms cf wage units and argued :::at faliing wages would be followed by increased profit expectations.1::

Robertson (pp. 44ê-53) applied the 5ame reasoning te the symmetric case Df excess demand for gOOGS and iabour .. ~ssuming, as before. a given merey stccx. the process of raising orices and wages 'Neuld

oe

interruptec firstly 'Jy the ar.emp ~o restore the equiiibrium vaiue of .1<, whlch wouid ce foiiowec ty t~~ negative. effe.cr cf higher wages an the marginal efficiency cf capital. The e~suing contrac::cr: cf :he demand fer iabour wculd. under the "ssumption of a wage lag. !ead ,c highe: unemplcyment, ando through that. a suspe~sion oF the wage r:sir:g prccess .. ~l this stage of the argument. Robertscn asc:-:ced the wage iag to the inabiiity 6y wage-earners to realize that prices will stop rising in the ruture.How great that shocl< and jolt [to ,-isir:g prices ar:d wages] neec ce. and ;n particUlar how !arge!y it takes the rorm cf unempioyment, woL:!d depene iargely on the wage-policy of Trade Unions: and that is when goed :eaeershic from inside, and even ear-strcking fram outside, would have a gem.:ine pare

:0

play, name!y. in inducing the Trade Unions to take their share of the medicine of stabilisation in the form of abstention frem pressure fcr wage advar.ces rather than in the form of unempieyment (p. 450).13

As '·,.;e shall see below. this was essential to Robertson's suggestions fer monetary policy during the process of "creeping inílation" in Great Britain in the i950s. He conciuded in his Lectures that "there is not much left of the simpliste Keynesian doctrine that the levei of employmem dces not depend aI ali on lhe levei of money-wage rates" (p. 452)

e:< ~ected. According to Robertsor (1963a), wage-earners would accept an immediate wage fail if they l<new the money-wage ie'/el consistent with "rl1ll employment".1" In the Study, the effects or a wage lag on empioymer,t '-'lere

distingu:shed from the impact cf prcpcr11cnai changes :;f wages and p~ices cr ~he iabour supply decision (Robertsor. 19'15, pp 213-16 ane :225-27). He conS:C2íed that the "lagging of money wages behir.e risirg prices is ilOW so general!y acr.;i,~ed

as scarcely to require detailed iilus,ration' i~ 215). Imerestingiy ercL.:gr.. the compound effect of the 'r.;oney illusion' ane tne wage ::g means that when '.vages

-:0

fali the depression becomes temporarily more intense, as prices fali unde: theimpact cf reduced consumpticn fíOm wage-earners.

It should be observed, however, tha, the finai and most acure s,age cf depression tends to occur after a considerabie ~eadjustment of wage-rates has taken place (e.g. in 1878-9,i886 and 1904): indeed the impulse given to production by the removal of the tax upon business men actuaily enhances the purely monetarl and illusory inducements to restriction (1915, pp.

226-27).15

r

1

II

!

-p

!

14

iIIustrates the argument with a diagram where utility appears on the ordinate and work on the abscissa, Iike his previous treatment in the Study. He discusses in detail the situation in which the "work-demand for income has an elasticity less than one", that is, a supply curve of work negatively sloped. For Robertson (as for Robbins, 1930, p. 129) the issue cannot be decided bya priori reasoning, but by empirical investigation only. After considering the evidence, Robertson (pp. 150-51) concludes that "in respect of both hours and intensity, the relevant stretch of the supply curve is backward rising, at any rate in the short period". The situation is complicated in longer periods by the fact that "Ieisure is apt to become boring unless you have money to spend in it. while given time the standard of wants is apt to adjust itself', which means that the labour-Ieisure choices may be reversed later.17 Robertson's notion of a "natural rate of unemployment" as part of his perception of the working of the labour market in the 1950s will be dealt with next.

IV. "Full Employment", Phillips and the Cohen Council Report

Robertson (1963a, pp. 437-38) was criticai of what he believed to be a "dramatisation" by Keynes (1936) of the contrast between "mass unemployment" on the one hand and "full employment" on the other. This "over-simplification" of the problem of economic policy objectives was rejected by him, since it is not possible "to draw a hard-and-fast line ... between what happens when there are unemployed resources and what happens when there is something more or less arbitrarily defined as 'full employment'; in the fashionable jargon of 1947, 'bottlenecks' may begin to appear at any stage in an industrial revival" ([1922] 1948, p. 205). His criticism of "full employment" as a policy goal was based on the inflationary dangers

of a margin of unemployment smaller than the "transitional unemployment" associated with the transfer of labour frem one sector of the economy to another ([1957] 1992, pp. 76- 7; see also Presley, 1979, pp. 240-41, and Danes, 1985, pp. 115-20). In the post-war period the employment problem took on a new form, namely

"

-Not how dcse an dpproximation to abscluteiy fLil employment shouid we aim at reaching, but how large a retreat frem absciuteiy rull employment - clJer-employment, as seme of us nave rcr hes~ated to :escribe lt - shcuic '.V€;

tolerate eccurring.. =·:or.omically, it is Ir eS3ef~(;8 ,he same eie ;rccier:-;3s before - namely, hc'N muc;-, siack dees :3 '-;--;Odt~í,; :,:concmy requ:re in orcer :c avoid cssifieation of its industrial struc:ure and 3 prcgressilJe uncerminirs ,:;; its standard of value? (1963a, p, 438)

The noticn of a rate ci unemploymem consistent with price :e'/el stabiiicj iS

behind Robertson's (p. 436) cnticism of the 'apcst!es of fui! empioyment". 3S represented by the '1944'\Nhite Paper" of the 6ritish gcvernment. by 8e'/eridçes IJolume Fui! Employment in a Free Society a"d by lhe United States Empioyment

.2..::

-"

moves upwards on the average in ar least a similar proportion ... 'Stability' almost

seems to ha'le been re-defined in ter;ns of :2 or-3 '~er cent annual rise" (see also lhe Cohen Council reporto pp. 29-30).

Rocertson put forward two objec:icns ~o lhat new nct:on of "stability"

,'l,ssuming that the slow pace of the uocreep is ter~3ble. a ;:;r;C8-(:se cf abeut 3 ;::er

cent a year would not discourage U":e use cf mcney fer orcinary transactions. bu!

long-term contracts would be affected. T-:e attempts to êrotecr thcse contrac~s ~rom

a rutl.!re rise in prices. however. wOl.!!d turn the steady inflation imo an acce!erating

one:

It is at this point that dOl.!bts about lhe :nerfts cf the prcgramme of slcw uncreep coalesce with doucts about its .oracticabifity. For if i:s inequaliiies can

only be softened ". by ~he excogitaticn of a 'Nhole tlattery of contracting-.:;ut

devices. it is surely to be expected that thcse sections of the popl.!laticn who

are at preseni the leaders in. and the beneficlaries of. the present

comparatively dignified inflationar/ precession will ali the time De

endeavouring to preserve and restcre their threatened !eads. Thus in practice

the rescue operations so carefl.!lly planned would probably be far frem

completely effective ,.. Sut what that means is that ~he planned orderly fali in

the value of money would be in danger of turning into a landslide, generating

not a conformable condition to "fuil employment" Jut a hectic and disorderly

muddle. which could only be checked. at the cost of rr.uch disemployment and

distress. by the re-establishment of drastic monetarj discipiine (pp. 252-53:

see also his comments in Hague.1962. p. 405)

This is reminiscent of F riedman's (1 968) weil-~r.own .. accelerationist" resutt. but :he reasoning is not quite the same, as Robertson had :n mind a hetercgeneous soc:ety

composed of groups with different abilities LO act upon their inflation expectations.

Robertson's conclusion that the "fuI! err.ployment pledge" (p 255) is untenable !ed

him to suggest long-term stabiiity of the price levei as the declared pclicy objecti'le cf

monetaf"'j paliei. He stressed that this wCl.!ld ha'Je to be accompanied not only oy a

"reasonable interpretation cf the concept cf 'fuil employment .. ·. but also 'oy ~he

81BUOTECA MARIO HENRIQUE

SIMONSEr-fUlDAçlO GETUUO VARGAS

_-l~ . I

reccgnition that "it may not ~e '.Vise to regard the attainment even of an emoloyment

objectl'Je in itself reasonably ccnceived as in ali c:rcumS:3nces :he a:)soiu~ei\/

G\/emding aim of policy" lp. 256).13

The interpretation of British inflaticn put ::::r.vâíc in the '::íeecmg Infiaticn"

artic!e beca me part :r the first report of tr.e CCLinc:! cn Phces. P:-8eucti'lity ane lncome. with Lord Cohen as Chairmê.i- 3n(~ ;-.iarold ricwilt ian acccL,;mant) anc

Dennis Robertson as members (cf. eSp. pp. =~-25 2nd 29-21 or the ;lrst repcr:. anc

Hutc"ison ['196ô] 1992, p. 131: for the circllmstances sur~cuncir.g RcceÍLson's appcintment to the Council S2e the ., editcíiai ccmmenrar{ in Rccertson. [1959j 1992). 8ecause of the goal af price stabilit,!. the crucial pari cf the report was the section on how to prevent íising money- wages withcul crovck:r.ç an in,er.·;e

increase of unemployment. Rebertson had discussed critically in an ac:cress to the

Schcol of Central Bankers in 1957 the p revailing view that a rate cf IJnemployment around 10 per cent wouid be needed to prevent wage demands frem exceeding prodllctivity growth 1::1. He maintained on that occ3sion that if tr3de unlon ieaders and

w:..ge-earners in general became convinced of the seriousness of the government's

ccm;nitment to price stability, money-wage c!aims would be substantially softenec

([1957] 1992, pp. 77-8). which was repeated in the first Cohen Council reporto ,~fter acknowledging a rise in the margin of unemployment to about 2,0 per cem

lperceived by the Council as necessary for the ":=;fficient working' cf :he economic

system), and contrasting this with the dramatic forecasts of 3 rate of1 O per cenl

mentioned 3bove, the report stated on p.

42

that no further cnemplo:/ment 'Ncuidte

n ecessa r,/.\Ne ourselves at present take a ~cre optimls:ic 'Jle'N. T11e ::ecline in the

intensity af demando working through a dec!ine in rea!ised and 8nticlp3ted

profits, must certainiy be expected to stiffen :he reslstance cf empio,/ers to

c!aims for inc~eased wage rates. It '.'ICL,;iC ce excessiv2 cpti~:s~ to hope troat

it would prevent any '-I'Iage ciaims ceing r:;ade. :ut we celie'J2 ~hat ~he dec:ine

in the intensity of demand will tend

:0

mcderate :~e inslstence '.'Iith which they\3

a successful attempt to continue the spectacular rise of wage rates in recent

years would not only involve real hardship ror large sections cf their fellow

citizens but w'Juld also ultimateiy endanger their own future employment and

standard of living (32e also Robertson's comments in Hague. 1962. ;:p. 405 and 407).

Robertson had explained in an aderess cn "The Role of Persuasion in Eccncmic

,l\ffairs" that trade unicrs woule not be con'linced simpiy by "ear-strci<ing·'. a ~hrase

ne used to describe the attempt to estabiis;, acode by means of which scmecne

cecomes "aware cf what is expected cf him and benaves accordingly" (1956. ;;.

155). He praised the roie of the "force cf c:ersuasion and convention·'. OL.:t at the same time stressed that it is "limited in supply" ano tha! a "framewor~, of monetarj

iaw and administration" should be created in order te make possib!e a .. regime cf

incentives and disincentives. which wii! prevent these prec:ous quaiities

oi

persuasiveness and persuadability from being wastefully squancered through being

se! tasks which it is outside their compass te periorm" (p. 172).

The reactions by trade unions to the Cohen Council report were quite hcstiie

(see Worswick.1962, p. 59). Howard Ellis (1958, p. 1040) expressed bewilderment

with the strong criticism advanced by the Labour Party, as the report had rejected the

theory that inflation could be ascribed directly to a wage push. The report's

conclusion that the British inflation was predominantly "demand-pull" and not

"ccst-push" were confirmed statistically a few months later by Phillips (1958), which would

soon beco me seminal. Rcbertson praised Phillips's study of the relation between

unemployment and money-wages in an address delilJered in 1959, despite seme

skepticism that Phillips's result - that

tre

rate of unemployment consistent with pricele'lel stability is about 2.5 per cent - wculd apply to such a long pericd cf time as a

century (Robertson [1959] 1992. pp. 111-12; cf. his comments in Hague. 1962, p.

45ô, that "one could not put much reliance an [Phillips's] resu!ts because it assumed

there 'Nas a fixed psychological functian re!ating the attitude cf trade unicns ~c the

.'

Had been available to the Cohen Council twelve mcnths ago. they would [not]

nave enabled it to modif,! very much 1he woras :1'1 'Nhich. in the centrai

passage of its reporto it expressed. tentatively bet ralr:y :'irm!y. its hunch in this

important matter. This was to the effect that the fir:-:: action whic:--' had been

taken to cateh hole of demand wou/c! be foune to wc~:~ :t:; way throcçh into the

wage contraet. and that whatever might be true cf cI~er ccuntries and other

times. it would

not

requira enormous realised peree::tages of unempioyn-:ent.but only a definite ehange of ôtmosphere. to taK8 a great ceai of the stream

out of the wage push (p. 112; see also Rccert::on. 1 Sê 1. p. 37).

The eommentators (see, e.g., Ellis. 1958; Dow. 1958; Feilner, 1959, pp. 2.14-46:

Samuelson, 1963. pp. 521-22; Hutchison [1968]1992. pp. ~ 37 -38) on the first Cohen

Council rep0r:t missed its central message.2o During 1957-59. the Chaneel!or cf the

Exchequer Peter Thorneycreft carried out a pcliey cf disinTlation and money-wage

claims were below their earlier pattern, with only a slight inc:-ease of unemployment.

The rate of unemployment. which was 1.4% in 1957. raisee to 2.1 and 2.2 in 1958

and 1959 respeetively, and fell again to 1.6% in 1960. Retail prices. whieh had grown

frem 100 in 1950 to 142 in 1957, reached 147 in 1958 and 1959, and went up to 149

in 1960. Nominal weekly wage rates, which had grown from 100 in 1950 to 154 in

1957. reached 159, 164 and 168 in 1958, 1959 and 1960. respectively (see

Knowles, 1962, p. 536). Robertson (1963a, p. 451; see also 1963b, p. 23) had

interpreted the experienee cf 1957 as "fairly convinc:ng evidence. first lhat there is a clear link between monetarj poliey and the money wage !e'/el, and secondly that it

doesn't requir~ either tremendous sermonising or horrifyinç !evels of unemployment

to make that link effective, but only a reasonable amount cf courage cn :he part of

politieians and a reasonable amount of enlightened se!f-ir.,erest on the part cf the

leaders of organised labour". He further ciaimed in his Marshall Lectures deli'lered in

Cambridge in Oetober 1960 (which also contains a repiy to Kaidor's charge of

inccnsisteneY)21 that the events of 1957-8 had vindicated his '/iew cf the' rationaiity"

of workers in preferring lower rates of increase

or

money-'.vages to higherunemployment, whenever they have the necessarj information about monetary

:0

policy: "In the hideous language of rr:edern strategy, the deterrent has t::ecorr.e

credible beca use it has been :Jsed. It did not lead to social catastíephe - ~here 'Nas

no good reason to fear that it would. Sut it 'Nas ur-pleasant. and even its ',varmest I~efenders would be deiiçhted if there shculd orove never to be any ne~c Tor its

iepe[ition an the 1957 scale' ( 1961. P 38'.

V Concludina ,~em3r'{s

Robertson's theoreticai writings anc ccntributions to debates an ec:::nomic

policy in his main bOOKS and in the 1 SSOs show that he grasped what 'Ncuid :atei

become i<nown as the ""aturai rate of cnemployment hypothesis" and Orle cf its mam

coroilaries, 'fiz. that demand rr:anagerr:er:t cannot aim for the unemp!oyrr:ent rate

surmised as best. c'Jen though his approach to the business cycIe is quite far rrem

the respective moneta!"j frameworks of Fr:edman (1968) and Lucas (197"2). it '.'Ias

c!ear to Robertson that price levei changes wou!d affect employment and output only

if 'hey were unanticipated. One cannot disregard the possibility of an influence on

:=riedman on this point. as th~ American economist worked alongside Rccertson in

Cambridge for part of the 1950s (see 0,lizen and Presiey, 1995, p. 640, n. 2: cf. Friedman's [1969, p. 1J acl<nowledgrr:ent of discussions with Robertscn on the

"Cptimum Quantity of ivloney"). In his memorandum to the Canadian Commission on

Banking and Finance, Robertson (19ô3b, pp. 10-11) remained faithful te ~he view

first put forward in his Sludy and elaborated in Banking Policy ". that ~he aim of

moneta!"} policy shouid be to generate a flow Df moneta!"j demand so as :c' enable

the participants in the growth prccess - enterprisers, savers and hired v'Jcr:<ers - [Q

realize their intentions with a minimum cf fíicticn and of distortion cf :he :íue

significance of the moneta!"j contracts they are making with one another'. that is.

'Nnat he used to call "monetar} equilibrium" (cf. 1963a, part 111, chap. 2). :~is averall

consistency througnout five decades - inc!uding the cnanges of perspective cn points

analysis

oi

the relation bel:ween mcney. pr:ces and output is remarkable in ~hehistory

oi

twentieth c~ntury monetarj thought.We would iike to thank Geeff Harcoun:. Peter Rcs~er. 'v\;ar~=n Young ar',d partic:r:;ar.ts

at the 1998 meetings of the Hisrcr; of Eccnemics Scc:etj. 1\10nt;eal. fei ~e'r::f:.;1

comments. Mauro Boianovs:"<y çratefully ack:lcwiedges .3 iesearcn grant F,em

C,'1P:::

(Brazilian Research Council).

1. See also Leijonhufvud (1998, pp. 184-85), 'Nho í'i':aintains "h ... ~

llldl. under :he

assumption of rational expectations but in the absence of perfect imertemporai

coordination, the Phillips space 'Nould fill up witn '/erticai Phillips curves, instead of

collapsing to a single one. Phelps (1995, p. 17) iefers to Lerner (1949) and Fe!lner

(1959) as anticipators of the "neutrality axiom·'. Actually. the idea goes at ieast as far

back as Wicksell ([1898J 1936); see Soianovsky. 1998.

2. Robertson (.o. 157) listed three important causes of such a revision: the "confidence inspired by exceptionally good c~ops in the capabilities of a given

country"; the "wearing out of an unusually large number of the instruments of

production"; and "the occurrence

oi

an invention in some important trade ar groupsof trades".

3. See also 8i99 (1990, pp. 124-25) ror a discL:ssicn of Rccerson's diagramo Si99's

interpretation, however, is marred by his suggestion that F~cbertson's analysis is akin

to Keynes's shifts in the marginal efficiency of capital and by his neglect of the

concept of elasticity of demand for income in terms af effort.

._---'

I

f

\

,

Ij

I

l-i

i

j

,

22

4. Robertson (p. 207) suggested that the influence of the high value attached to leisure in the boom is particularly strong in the coai trade, where "the marginal utility of a 'straight back and the sunlight' is peculiarly high". He ascribed the lesser elasticity of the effort-demand of the working classes (when compared to businessmen) to the "more unpleasant and monotonous character of their work and to the greater urgency of their material wants". In another book, Robertson ([1926] 1949, pp. 19-20) assumed a hypothetical economy of independent producers with effort-elasticity between that of the actual employer and that of the actual employee.

5. Cf. his description of a trade slump as "a time of excessive and unwished-for repose, when factories work half-time and clerks sit twiddling their pens, when business men go to the South of France, or to Summer Schools, or to prison, and workmen tramp the streets striving to rid themselves of the blessing of Leisure" ([1923] 1931, p. 133; see also [1926] 1949, p. 21).

6. "Of course the stimulus of rising prices is partly founded in iIIusion. The salaried official and the trade unionist have been beguiled into accepting employment for a lower real wage than they intended. Even the business leader is the victim of iIIusion: for he is spurred on not only by real gains at the expense of his debenture-holders and his doctor and even ... of his work-people, but also by imaginary gains at the expenses of his fellow business men. It is so hard at first to believe that other people will really have the effrontery or the good fortune to raise their charges as much as he has raised his own" ([1922] 1948, p. 139). "To some extent this optimism is irrational - people are slow to realise that other people's selling-prices will rise as well as their own" (1963a, p. 411). The passage from p. 139 of Money was quoted by Phelps (1969, p. 157, n. 31) to support his notion that the firm will not raise its price

7. The "surprise supply function" cannot be found in Pigou (see Collard, 1996, p. 919). Lavington (1922, chap. V) discussed the influence of changes in the price levei on "business confidence", with no mention of the confusion between absolute and relative prices. Robertson ([1926] 1949, p. 3) was criticai of basing business cycle theory on the element of "errar". He objected in the Study to "those who find the causes of fluctuations in what they cal! 'psychology of the business man' and assume without further argument that they are incalculable and unfit for systematic study", and suggested that "it seems only natural, in the absence of proof. to give [the business man] the benefit of the doubt, and assume that they are in part at least induced, however irrationally, by externai objective facts" ([1915]1948, pp. 8-9).

8. This was one of the exceptions to MiII's famous proposition that "demand for goods is not demand for labour" ([1848] 1909, p. 87). MiII assumed, according to the classical tradition inaugurated by Adam Smith ([1776J 1976, pp. 99-100), that the supply of effort is a positive function of the real wage. See also Mill's ([1833J 1967, p. 191) statement that "an unusual extension of the spirit of speculation, accompanied rather than caused by a great increase of paper credit, had praduced [in 1825] a rise of prices, which not being supposed to be connected with a depreciation of the currency, each merchant or manufacturer considered to arise from an increase of the effectual demand for his particular article ... "

9. Cf. Alfred Marshall's statement to the 1899 Committee on Indian Currency: "Employees cannot, as a rule, foresee; and they have less power to act on their knowledge" (1926, p. 284).

10. Champernowne's 1936 article was reproduced in Lekachman (1964),

accompanied by another piece by Champernowne on his 1963 assessment of The

General Theory. Champernowne's new article, entitled "Expectations and the Links

I

I

i

1

l

i

~

j

j

24

11. Kohn (1981) drew similar conclusions from his loanable funds model incorporating the Keynesian income-expenditure mechanism in a Robertsonian sequence analysis. Assuming a production period of the same length as the period during which money is spent. Kohn shows that the joint assumption of wage stickiness (in the sense of the inability of money-wages to react quickly enough to clear the labour market within a single period) and a given interest rate generates persistent deflation with constant unemployment. The source of wage stickiness is not, in Kohn's analysis, the existence of wage contracts, which are set according to the production period, but the wage-earners' resistance to adjust money-wages in order to clear the market at the end of each production period. Robertson introduced wage contracts in his analytical monetary framework in 1933, under the assumptions that money-wages are "prevented by contract or custam from varying during such short periods of time" (Robertson's "day" during which the stock of money "changes hands") and that a decline in demand for goods is met only by a "reduction of prices sufficient to market the original output" ([1933]1966, p. 49; cf. [1926]1949, p. ix). His treatment of the "wage lag" in the Study is discussed below.

12. Robertson (p. 445) acknowledged in connection with the effects of wage reductions on profits that "once we begin to talk in terms of plans and expectations anything may happen" and suggested that the dangers of "wage f1exibility promoting excessive instability" could be countered by combining wage reductions with expansionary policies like publíc works.

13. Wilson ([1980] 1992, p. 55) quoted the passage, without pointing, however, to the role of the wage-earners' information about monetary policy in preventing higher unemployment.

14. Robertson rejected Keynes's (1936, pp. 13-14) hypothesis that workers are

25

15. Robertson (pp. 248-9) sustained (against Pigou) that there was some rationality in the Trade Unions's resistance to a falling levei of money wages, as the demand for labour in the constructional industry is inelastic in the depression, which would cause a fali in the aggregate income of union members. Furthermore, the employer is for a "considerable time unable or unwilling to retaliate [to viscous money-wages] by curtailing unemployment" (see also Boianovsky, 1998, pp. 233-34).

16. See Aslanbeigui, 1992, who provides evidence that this was Pigou's notion of the aggregate labour supply function, and of Keynes's misinterpretation of Pigou on this point.

17. The supply of eftort by the businessman - another important element of Robertson's Study - practically disappeared from the analytical framework of his

Lectures. As he explained, "enterprise" is a composite factor of production combining

work of a particular kind, provision of capital and exposure of that capital to risk (1963a, p. 104). The emphasis on the supply of eftort by the businessman followed the form of business organisation dominant at the time of Marshall's PrincipIes, that

is, the ruling of the business by its owner. With the prevailing joint-stock form of

organisation, business enterprise consists above ali in the "bearing of uncertainty" (p. 265). Robertson concludes that "the supply of risk-taking by business men is Iikely to be a good deal more responsive to alterations in reward than the amount of skill or eftort which they display" (p. 266).

18. The objection to full employment as a policy goal had been advanced by Robbins (1954; see Robertson's 1955 review in the Eccncmic Jouma/, p. 107), but without any suggestion of the acceleration cf inflation stressed by Robertson.

19. Harry Johnson (1956, pp. 19-20), for instance, sustained that "experience suggests that substantial unemployment would be required to prevent wages frem

increasing at an inflationary rate"_ and that the only solution to the overload on the

-I

I

26

British economy "seems to be to stagger along under as we have been doing, meeting crises by a succession of temporary and regrettable expedients". In the same vein, David Worswick (1958, pp. 252-3) maintained in his memorandum prepared for the Cohen Council that "while trade union leaders might be deterred from wage demands if unemployment were 10 or 15 per cent ... they would hardly be deterred by a mere 2 or 3 per cent unemployed".

20 .. Fellner's interpretation is especially relevant, as he took expectations into account in his analysis of the inflationary processo According to Fellner (1959, pp. 227 and 234), in the case of "demand inflation" the reduction of aggregate demand f1attens the price trend with only a temporary reduction of employment during which price-expectations are made non-inflationary. By contrast, in the event of "cost inflation", the reduction in aggregate demand would bring about a permanent contraction of the levei of resource utilization. Fellner (p. 235) suggested that wage-push inflation would show an "acce/erating tendency". The process starts by the attempt of some groups to gain at the expense of others in real terms, which is successful to the extent that the wage-and-price increases in some sectors "catch other sectors unawares". In the subsequent phase, "one must run tast in order to stand still". This is not tar from Robertson's description of the acceleration process, but framed in terms of cost-push. Fellner sent a copy of his paper to Robertson, who criticised Fellner's definition of demand and cost inflation on fhe grounds that it mixed up "questions of the historical cause and remedial action" (Robertson, [1959] 1992, p. 109). Fellner (p. 245) was criticai of the Cohen Council's conclusion that British

i

1

! t

\

j

I

!

I;

27

I

28

References

Aslanbeigui, N. 1992. Pigou's Inconsistencies or Keynes's Misconceptions? History

of Political Economy. 24.2: 413-33.

Bigg, RJ. 1990. Cambridge and the Monetary Theory of Production: The Colfapse of

Marsha/lian Macroeconomics. London: Macmillan.

Boianovsky, M. 1998. Wicksell on Deflation in the Early 1920s. History of Polítical

Economy. 30.2: 219-75.

Champernowne, D.G. 1936. Unemployment, Basic and Monetary: the Classical and the Keynesian. Review of Economic Studies. 3 (June): 201-16.

Champernowne, D.G. 1964. Expectations and the Links Between the Economic Future and Present. In R Lekachman (ed.): Keynes' General Theory: Report of

Three Decades. New York: St Martin's Press.

Collard, D. 1996. Pigou and Modem Business Cycle Theory. Economic Joumal. 106

(July): 912-24.

Danes, A. 1985. Dennis Robertson and Keynes's General Theory. In G.C. Harcourt (ed.): Keynes and His Contemporaries. London: Macmillan.

Darity, W. and W. Young. 1995. IS-LM: An Inquest. History of Political Economy.

27.1: 1-41.

Dennison, S.R and J.R. Presley (eds) 1992. Robertson on Economic Policy.

London: Macmillan.

Dow, J.C.R 1958. The Cohen Council on Inflation. Economic Joumal. 68 (Sept): 610-27.

Ellis, H. 1958. Review of the First Cohen Report. American Economic Review. 48.5:

1039-40.

Fellner, W. 1952. The Robertsonian Evolution. American Economic Review.

42.3:

265-82. As reprinted in J.R. Presley (ed.) 1992.

•

29

First Report of the Councilon Prices. Productivity and Incomes. ·~:::a. London: Her

Majesty Stationery Office.

Forget, E. 1990. John Stuart MiII's Business Cycle. History of =-:Jitical Economy.

22.4: 629-42.

Friedman. M. [1968] 1969. The Role of Monetary Policy. As repnl.l:d in Friedman. 1969.

Friedman, M. 1969. The Optimum Quantity of Money and Olher =~says. Chicago: Aldine.

Friedman. M. 1975. Unemployment versus Inflation? An Evaluatic.- of the Phillips Curve. Institute of Economic Affairs, Occasional Paper44.

Goodhart, C.A.E. and J.R. Presley. 1994. Real Business C:.,:!e Theory: A Restatement of Robertsonian Economics? Economic Notes. 23.2: 2:-:-91.

Hague, O.C. 1962. Summary Record of the Debate. In Inflation (p~ceedings of a Conference held by the International Economic Association in AuglJs~ 1959), ed. by D.C. Hague. New Yor!<: St Martin's Press.

Hutchison T.W. [1968] 1992. Economics and Economic Policy in Britain, 1946-1966.

Aldershot: Gregg Revivals.

Kaldor. N. [1958] 1989. Monetary Policy. Economic Stability and Growth. In F. Targetti and A. Thirlwall (eds): The Essential Kaldor. London: Ouckworth.

Keynes, J.M. 1936. The General Theory of Employment. Interest and Money.

London: Macmillan.

Knowles. K. 1962. Wages and Productivity. In G.D.N. Worswick and P.H. Ady (eds), 1962.

Kohn, M. 1981. A Loanable Funds Theory of Unemployment and Monetary Disequilibrium. American Economic Review. 71.5: 859-79.

Laidler. O .. 1995. Robertson in the 1920s. European Joumal of the History of

Economic Thought. 2.1: 151-74.

t

Lavington, F. 1922. The Trade Cycle. London: P.S. King.

Leeson,

R.

1997. The Eclipse of the Goal of Zero Inflation. History of PoliticalEconomy. 29.3: 445-96.

,

f

f

j

I

I

~

I

i

30

Leijonhufvud, A. 1998. Mr Keynes and the Moderns. European Joumal of the History

of Economic Thought. 5.1: 169-188.

-Lerner,

A.

1949. The Inflationary Process - Some Theoretical Aspects. Review of Economics and Statistics. 31 (Aug): 193-200.Lucas, R. 1972. Expectations and the Neutrality of Money. Joumal of Economic Theory. 4 (April): 103-24.

Lucas, R. and L. Rapping. 1969. Real Wages, Employment and Inflation. Joumal of Political Economy. 77.5: 721-54.

Link, R. 1959. English Theories of Economic Fluctuations: 1815-1848. New York: Columbia University Press.

Marshall,

A.

1926. Official Papers. Edited by J.M. Keynes. London: Macmillan.MiII, J.S. [1833]1967. The Currency Jungle. In J.M. Robson (ed.): Collected Works of John Stuart MiI/, v. IV. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Mill, J.S. [1848] 1909. Principies of Political Economy. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

Mizen, P. and J.R. Presley. 1995. Robertson and Persistent Negative Reactions to Keynes's General Theory: Some New Evidence. History of Political Economy. 27.4: 639-51.

Moggridge, D. (ed.) 1973. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. XIII. London and Cambridge: Macmillan and Cambridge University Press.

Negishi. T. 1989. History of Economic Theory. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Phelps, E. 1967. Phillips Curves, Expectations of Inflation and Optimal Unemployment Over Time. Economica. 34.3: 254-81.

Phelps, E. 1968. Money Wage Dynamics and Labor Market Equilibrium. Joumal of Political Economy. 76 (Aug, part 2): 678-711.

Phelps, E. 1969. The Emerging Microeconomics in Employment and Inflation Theory. American Economic Review. 59.2: 147-60.

Phelps, E. 1995. The origins and further development of the natural rate of