INFLATION DYMAMICS IN

BRAZIL: AN EMPIRICAL

APPROACH

Mauricio Oreng

Prof. Marco A. Bonomo

I .

Introduction

Calvo’s model (1983) implied New Keynesian Phillips Curve (NKPC) addressed some of the unpleasant features of the New Classical version (NCPC), like the fact that only unanticipated variations in nominal spending could affect the real economic activity. Such result, if analyzed more thoroughly, would suggest that monetary policy could influence real GDP only through its immediate effects, affecting prices only in the medium / long run. This is, according to empirical evidence, highly counterfactual.

By means of an optimal price setting model, using the hypothesis of staggered prices, Calvo addressed the issue, obtaining then a so called - by Roberts (1995) - New Keynesian Phillips Curve. Thereby, one could concluded that the impact of monetary policy on real economic activity may last until many periods ahead. In addition, this model had on its favor persuasive empirical evidence, as found by Sbordone (2000), when comparing actual inflation and its prediction by Calvo’s model.

Nevertheless, according to some economists, we have some reasons one should not feel very comfortable with such model. There are supposedly two main problems with that specification of the Phillips Curve proposed by Calvo: (i) first: NKPC implies a negative relationship between inflation next period and today’s output gap, or, in particular, it predicts lower inflation following periods when real GDP is above its natural value. Second, such specification does not allow for any inflation inertia whatsoever, relying too much on agents’ forward looking behavior, in spite of the fact that many central banks around the world use models incorporating persistence in price acceleration.

methodology that would allow us to test with more precision empirical evidence for Calvo’s Phillips Curve.

On the second issue concerning the problems in NKPC specification, Christiano et al.(2001)’s VAR studies bring up some piece of evidence against the purely forward looking behavior hypothesis, suggested by Calvo’s NKPC. Examining the effects of monetary disturbances on inflation and output, Christiano found that inflation is affected by changes in monetary policy only after most of the output response (to the very same shock) has already occurred. However, as Calvo’s would preach by his model, inflation is determined solely by future expected output gaps, and thus, following a monetary shock, it should move before output. In addition those results, and unexpectedly in accordance with theory, Chistiano also found some high degree of persistence in inflation through this tests, which strengthened the will to try empirically variations on standard Calvo´ s specification, now allowing for the possibility of existence of a backward looking component in inflation dynamics. The result then was a another NKPC, mixing agent’s backward and forward looking behavior, so called the Hybrid NKPC.

Aiming at this discussion above on the NKPC’s problems, and using american data, Gali and Gertler (1999) tested models that incorporate the approach of using real marginal costs as a proxy for the (ad-hoc) output gap, and that allow for some degree of persistence in inflation as well. As one main result, for the US economy, they came up with the effectiveness of using marginal costs as a proxy to the output gap, yielding the model’s predicted negative relation between future gaps and inflation acceleration. They also found evidence of some mild degree of persistence in US economy’s inflation dynamics. In addition, Gali, Gertler and Salido (2001), performs tests of the same nature for the european economy, finding that NKPC fits the data very well (even better than in the US), what becomes another piece of evidence favoring such theory.

How would those results turn out be for the brazilian economy? Our goal, in this current work, is simply to bring answers to such question. The idea is to perform empirical tests of the same nature as in Gali and Gertler (1999), always bearing in mind the need to adjust these experiments to brazilian reality. Hopefully, one will be able to obtain interesting conclusions about the brazilian inflation path within the Real era and to compare them with those obtained for the american economy. In addition, this may, in some cases, provide further robustness to empirical evidence favoring NKPC theorists, and specially in case of Gali and Gertler´ s work.

variables and proxies used, and providing some fast information on the econometric techniques. Later on, we stress, using both theoretical and empirical arguments (specificaly applied to the brazilian economy), on the advantages of using the marginal costs approach to estimate the NKPC, sustained by Gali and Gertler. The two sections that follow are dedicated to the estimations of, respectively, the purely NKPC and the hybrid one, always focusing to apply Gali and Gertler’s test to the brazilian economy. Then we conclude.

II.

M ethodological Considerations

Given the purpose of this current work - to perform, for the brazilian economy, the same type of tests Gali and Gertler have conduced for the US economy - our will here was: trying to perform, as closely as possible in a methodological sense, the very same procedures followed by the authors. So, it could be interesting to briefly highlight, at this point, some of the issues that came up whilst we took on the task of adapting the american research to brazilian reality.

First of all, some problems involving data matters have appeared, which is quite not surprising, since there are major asymmetries in both availability and reliability of economic data when we compare Brazil and the US. It is already known to most researchers the scarcity of economic data faced in developing countries, Brazil in particular. Without a full nor broad mass of data in hands, there were times when we faced the need to adapt, to brazilian economy, concepts of economic data (variables and proxies) in the US, so as to reduce the presence of asymmetries in the tests ran for these economies, and to prevent the generation of unwanted noise or measurement errors as well. One standard result from econometrics is that the latter can potentially hurt consistency of OLS (and also GMM) estimates.

To exemplify what we mean here, in the case of labor income data (used to obtain a measure of marginal costs), the US data comprises only the industrial and retail sectors (excluding agriculture), meanwhile, for Brazil, the unique of such measure available to us included the agricultural sector. We had some problems of the same nature with regard to variables like long term interest rates and broad-inflation. However, such data asymmetries are not expected to have huge impact on the estimates, for the proxies used herein were sought so as to maximize their co-movements with the original variables1. Thus, this problem

1

shall not hamper the comparability nor the quality of the results, despite the fact that some robustness tests (e.g. run the same tests with other proxies) should be performed in later versions.

One additional issue is that, when it comes to perform the tests and to compare the results obtained for the different economies, it might not be wasteful to look at countries’ historical differences in both economic and geo-political grounds. In particular, contrarily to the US, the brazilian economy had been facing in the past severe inflationary process, until the Real Plan - implemented in June 1994 - succeeded in bringing (relatively) price stabilization to the economy. In practical terms, this implies that, using time series comprising periods earlier and after the Real adoption, we are very likely to observe the presence of structural break(s) in our parameters estimates for Brazil.

Bearing this in mind, we were left with two different alternatives: (1) to use a very broad sample period for consistency reasons (like Gali and Gertler), albeit generating somewhat distorted estimates as a result of the applicability of Lucas critique - see Lucas (1976); (2) or to reduce the sample used in the models’ tests, confining it to the Real period, loosing in terms of degree of convergence to the real parameter value (consistency), but reducing dramatically the probability of structural breaks within our dataset. We have found better to choose the second alternative.

II.A -

Observation Sampling Window

Following Gali and Gertler (1999), we chose a dataset of quarterly observations of brazilian data, covering the interval T = [1994:3, 2002:2]. One must notice that we are left with only 32 observations, roughly more than one fifth of Gali and Gertler’s dataset for the US economy, which comprises data across 37 years. Such choice of ours - to shrink the dataset - can be justified, though, for reasons already mentioned above: by reducing the sample window, we try to minimize the effects of Lucas’ critique onto the estimates herein obtained.

One might know that, in brazilian economic history, one can easily divide the timeline in (at least) two very distinct moments: one phase earlier and another one after the Real implementation in 1994. The brazilian hyperinflationary process of the past was reversed by such major change in economic policy, which was crucial to bring yearly inflation down from figures around 2480% in 1993 to 22% in 19952. And intuitively, we

as a result of generalized price indexation. This allows us to conclude that the Real implementation brought not only a huge change in inflation level, but also affected the set of driving forces behind the inflation dynamics.

One further argument is also applicable to justify the rejection of data prior to 1994:3: hyperinflationary processes are sometimes linked to trajectories associated with bubbles, which is hard to be modeled (and therefore estimated).

Therefore, we realized (rather informally, we admit) that there can be little doubt about the existence of major structural changes in any inflation models’ parameters estimated with a sample beginning before 1994, as consequence of the Real Plan. In all, aware of the arguments above, it seemed very reasonable to us to avoid the greater costs of the existence of structural breaks by the compression of the sample window, even at a (smaller) loss in terms of convergence of parameters estimates.

II.B - Database and concepts

Bearing in mind the objective of being as close as possible to the methodology proposed by Gali and Gertler, and trying to minimize possible differences in concepts of data between the US and the brazilian economy, we set up the sample vector Q (T), for T established as above:

Q(T) = [

π

(T)´ R(T)´ Z(T)´ ]´

,

where

π

(T)

is the dependent variable, that is, a broad measure of inflation for the observation period, and R(T), Z(T) are, respectively, a vector of regressors and a vector of instruments,i.e.,

R(T) = [ s(T)´ x(T)´ ]´

Z(T) = [ s(T)´ x(T)´ i*(T)´

π

w(T)´

π

c(T)´

π

G(T)´ ]´.

In Z(T), we used some lagged variables, as was the case of st and xt.

A rough characterization of the dataset can be seen below, for all t in T:

(

i

): π

t– Inflation will be represented by percent quarterly variation in FGV’s IGP-M (GeneralMarket Price Index), because of the unavailability (in such a frequency) in Brazil of a measure like US’ GDP Deflator, used by Gali and Gertler. Given that IGP-M is a linear combination of a consumer price index (IPC), a producer price index (IPA) and a real state price index (INCC), it is fairly broad measure and thus serve as a good proxy for inflation, given our purposes. In IGP-M, IPA has weight of 0.6, IPC 0.3, and naturally INCC’s share is 0.1.

(

ii

):

s

t– Marginal cost is obtained from the following expression:s

t= log[S

t] – log[S*

t]

,

where

S

t= (W

tN

t)/ (GDP

t n).

Wtis working people’s income (Rendimento Real das Pessoas Ocupadas –IBGE), Nt is labor

force (Ocupação - IBGE) and NGDPt is nominal gross domestic product (PIB Nominal –

IBGE). So, s(t) represents deviation of labor income share from its steady state value, which

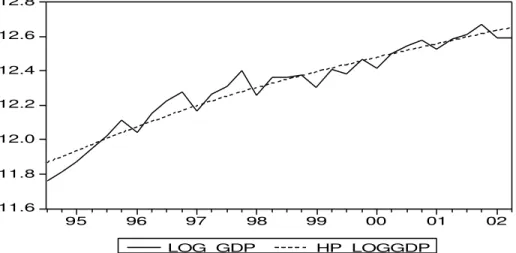

we’ll assume here, as a proxy, to be its long term average. The idea of why one comes to use such a measure in our tests will be given in Section IV. (See Figure 1)

(

iii

):

xt is the detrended output gap:x

t= y

t– y*

t,

where, yt is the log of output (i.e., the log of the nominal GDP, released by IBGE, and

deflated by FGV’s IGP-M). Meanwhile, yt* is the a long run trend for the real GDP, a proxy

for the natural output, calculated using Hodrick-Prescott’s methodology (HP-Filter). (See

Figure 2)

(

iv

):

it* is interest rates term spread. It is an instrument, which captures the evolution of theannun) and 30 days CDB rate (bank deposit rates), with the first being a proxy for long run interest rates, and the latter playing the role of short term interests.

(

v

): π

wt andπ

ct are, respectively, percent change of labor income (a variable also used tocalculate s(t)) and percent change of FIPE’s IPC index (consumer’s price index). The first plays

the role of wage inflation, whilst the latter is just a standard consumer’s inflation measure.

(

vi

): π

Gtis FGV’s IGP-DI index, another broad inflation measure, which comprises the sameimput variables as IGP-M (with the same weights), differing only in the period of observation (difference of 10 days). It is used as instrument in most of our tests.

The interested reader will find out that this sample specification is closely connected to the dataset used by Gali and Gertler, with marginal differences in interpretability, as in the case of IGP-M substituing a measure like GDP Deflator. Even the choice of the set of instruments used has respected the standards adopted in Gali and Gertler (1999).

II.C – Econometric Issues

As is commonly done across the literature, when it comes to estimate rational expectation models, we test models using the generalized method of moments (GMM), which also follows Gali and Gertler’s way. We shall estimate, for each model, both the reduced and structural forms (when possible), sometimes imposing restrictions in some parameters, in order to assess the robustness of results encountered, just like the original authors have done.

For every model estimated, we used Heteroskedastic Autoregressive Consistent (HAC) Covariance Matrix, proposed by Newey & West (1987), which guarantees more precise standard error estimates, which are robust to both heteroskedasticity and serial correlation. This allows us to be more confident on the results generated by the t-statistics, which will be rejecting (or accepting) the null that the parameter equal zero with greater precision than otherwise.

In case of models estimated by GMM (the vast majority in this work), we will perform tests on the overidentifying restrictions, the so called TJ test. Unwilling to go so much deep into econometric details, for this is not the scope here, the TJ statistic provide a test on the null hypothesis that the excessive number of moments condition (i.e. the number of instruments that exceeds the quantity of parameters estimated into the estimated equation) are indeed valid. One can prove that TJ statistic is distributed by a Chi-Square p.d.f., with

w = r - a degrees of freedom, where r is the number of instruments and a the number of

parameters to be estimated. More details on such test can be found in Hamilton (1994).

III.

The Problem of Estimating NKPC Using Output Gap

III.A – Some Theory First

One arrives at the NKPC by solving the problem of a monopolistically competitive firm (or set of identical firms), which sets its (their) prices optimally, i.e., determining them such that profits are maximized, subject to the constraint of time-dependent price adjustment. Accordingly to Calvo, from the hypothesis of constant price elasticity of demand, we obtain an aggregate price level such as follows (pt is the log of price level, which for

simplicity we name just price level):

p

t=

θ

p

t-1+ (1-

θ

) p

t*

(

1),

Letting mct represents the deviation of a firm’s real marginal costs from its steady

state, and

β

the subjective discount rate, firms maximize their expected discounted profits (by an stochastic discount factor, which adjusts for the risk), subject to time-dependent price rules, determining their prices according to the expression below, for k between zero and infinity:p

t* = (1-

θ

)

Σ

k(

βθ

)

kE

t{mc

t+k}

(

2).

It is interesting to notice that, when

θ

= 0

, we have the case of fully flexible prices, which in such case is to move accordingly to current marginal costs dynamics.Letting

π

t= p

t– p

t-1 denote the inflation rate in tt h period, the two expressions abovelead us to the following testable equation (for apropriate mct):

πt

=

λ

mc

t+

β

E

t{

π

t+1}

(3),

w here

λ

=

θ

-1(1 -

θ

) (1 -

βθ

)

.Using lead operators, we obtain, for k between zero and infinity:

πt

=

λ

Σ

kβkE

t{mc

t+k}

(4).

III.B – The econometrics of the NKPC (Traditional Approach)

In the past, researchers used the following relation to estimate expression (3):

mc

t=

κ

x

t(5),

where xt = yt – yt* , being yt the log of the product, and yt* the log of the “natural” product,

marginal cost (implicitly: quadratic cost function) yielded the following Phillips Curve, with

κ

being marginal cost elasticity with respect to output:πt

=

λκ

x

t+

β

E

t{

πt+1

}

(6).

In consonance with our purposes, and similarly as done by Gali and Gertler, we tested with brazilian data the following equation, lagging expression (6) by one period and also imposing

β

= 1

and

α

= -

λ

k.

πt

=

α

x

t-1+

πt-1

+

εt

(7).

Using OLS method, we obtained the following results for (7):

Table 1

Parameter

Estimate

Std. Error t-Statistic Prob.

α 0.152 0.067 2.260 0.0312

R-squared -0.803088 Mean dependent var 0.025894 Adjusted R-squared -0.803088 S.D. dependent var 0.018792 S.E. of regression 0.025233 Akaike info criterion -4.489572 Sum squared resid 0.019102 Schwarz criterion -4.443315 Log likelihood 70.58837 Durbin-Watson stat 2.587593

Notes: IGP-M used as the dependent variable. Exogenous variable is the log of the output gap, obtained by HP-Filter.

IGP-M lagged by one period is another regressor in (7), however the test impose its coefficient to equal to one.

OLS procedure used in estimation, with Newey & West HAC covariance matrix.

Adjusted Sample: 1994:4 – 2002:2, with 31 observations.

In the test shown above, we found a weakly significant (at 5% level, but not in a 1% sized test) and positive coefficient estimate, which comes relatively in synchrony with results obtained in the american study, where the authors yielded a significant positive value for

α

(trully, they got a equal to 0.081, rejecting the null on T-test at 1% level). The interpretation for such outcome is the same as in the original work, with this test above providing further evidence against the old fashioned way of estimating the New Keynesian Phillips Curve. In fact, such tests for both US and Brazil’s economy are more likely to support the old Phillips Curve (which uses Et-1{π

t} instead of Et{π

t+ 1} ), rather than the one formulated by Calvo.validity of the marginal cost approach to estimate parameters from the NKPC in Calvo’s fashion. We shall verify, in the sections that follow, if such results also hold true for the brazilian economy as well.

IV.

M arginal Costs Approach: The Purely Forward

Looking NKPC

IV.A – M otivating The New Specification

The poor empirical results obtained by Calvo’s NKPC, using data from both US and Brazil’s economy (the latter testified by the earlier section of this current work), when computing the output gap by some smooth technique, might not be a decisive evidence against Calvo’s model. In other words, these bad results should not lead to the rejection of its empirical validity, as some might conclude at a first glance. Gali and Gartler’s point is that such results are directly influenced by the methodology used to obtain the natural output, and the outcome of empirical tests on NKPC may be quite different conditional on the smoothing technique deployed. The authors claim that structural shocks, like change in tastes and variations in government spending may have an impact such that it offsets the forecasted negative relation between inflation acceleration today and the output gap last period. So it would be useful if we had a proxy for the output gap which did not suffer from this problem. The approach used here (for brazilian data), originally proposed in Gali and Gertler (1999), is to use marginal costs as a proxy to the output gap.

Gali and Gertler sustain that an alternative way to test the NKPC model is, instead of estimating equation (6), estimating the expression (3), replacing therefore the output gap (xt)

by the marginal costs (mct). Since the latter are not directly observable, we must use theory to

guide efforts on how to obtain such variable, so allowing us to go into estimation procedures. Section II.B of this current work shows details on how we obtained the measure of marginal costs (for the brazilian economy) which is deployed here. It is important to highlight here that the procedure used to get the marginal costs measure is meant to be as near as possible to the one proposed by the authors in this paper’s “ original (american) version” .

Y

t= A

tK

tαkN

tαn(8).

Real marginal costs can be expressed by the ratio of the real wage to the labor’s marginal product:

MC

t= (W

t/P

t)(

?

Y

t/

?

N

t)

-1(9).

Some algebraic manipulations, i.e., inserting using expression (8) and the partial derivative of Yt with respect to Nt into (9), yields the following expression below:

MC

t= S

tαn-1(10),

where

S

t= W

tN

t(P

tY

t)

-1.

From St, the share of labor income, we obtain st, which represents the percent

deviations of St from its steady state level (the latter is estimated by use of HP-Filter):

s

t= log[S

t] – log[S

t*]

(10*).

Then, st will then be used in the NKPC’s specifications that we test here, providing

our measure of marginal cost that will replace (as a proxy for) the standard measure of the output gap.

So, in the next section, we test the following version of Calvo’s NKPC:

πt

=

λ

s

t+

β

E

t{

πt+1

}

(11),

IV.B – Testing Calvo’s NKPC Using M arginal Costs

IV.B.1 – Reduced Form Estimates

As we have mentioned earlier, the estimation technique chosen to be applied to (11) is GMM, Generalized Method of Moments, very handy and widely deployed to test rational expectation models (as is the case now). One can show, by means of the iterated expectations law, that expression (11) implies the following moment condition, in the reduced form:

E

t{(

π

t-

λ

s

t-

βπt+1

)Z

t} = 0 (12).

Here, Zt denotes the set of instruments defined in section II.B, the very same one that will be

used in all tests henceforth.

Table 2

Parameter

Estimate

Std. Error t-Statistic Prob.

λ 0.167 0.081 2.061 0.0494

β 0.947 0.049 19.148 0.0000

S.E. of regression 0.027701 Sum squared resid 0.019950 Durbin-Watson stat 2.846987 J-statistic 0.145939

Notes: IGP-M used as inflation measure. Marginal cost obtained by expression (10*). Instruments list can be viewed in Section II.B.

GMM estimation procedure used, with Newey & West HAC covariance matrix estimation

Convergence achieved after 54 iterations.

Adjusted Sample: 1995:2 – 2002:1, with 28 observations.

TJ test failed to reject the null hypothesis of validity of overidentifying restrictions at 10%, 5% and 1% levels - Chi-Square pdf at 8 d.f..

For the american economy, Gali and Gertler (1999) had:

π

t= 0.023s

t+ 0.942E

t{

π

t+1}

(0.012) (0.045)

And for the european economy, Gali, Gertler and Salido (2001) found:

π

t= 0.088s

t+ 0.914E

t{

π

t+1}

Thus, what we got a positive (and significant at 5%) value for

λ

, using marginal cost replacing as a proxy to the “ actual” output gap. These results exposed in the table above are not so different to those obtained for the american economy (listed below). The great discrepancy concerns the estimates forλ

, given that output elasticity obtained for brazilian data is 7 times as high as the one gotten in the american case, and almost the double of estimates from european economy. In addition, the significance ofλ

is rather weak in brazilian case, for we fail to reject the null at 1% level, contrarily to what happens for the Europe and US economies. Nevertheless, it is also interesting to notice the similar values obtained for the betas (not only coefficient estimates, but also standard deviations), implying impatience rates relatively consistent, and not very contradictory, across the three economies tested.It could also be worthwhile to provide, at this point, some information on the TJ test. In the test of (12), we failed to reject the null hypothesis about the validity of the (r – a) overidentifying restrictions, where r is the quantity of instruments (10) and a is the number of parameters estimated (2). At 5%, the critical value of Chi-Square at 8 degrees of freedom is 15.51, greater than the value of 4.09 obtained for the TJ statistic. In fact, the same will happen to all conditions tested henceforth, so we shall not waste time in detailing further TJ results on these tests.

For symmetry ends, allowing us to compare this new approach to estimate the NKPC with the traditional one, we replaced st for xt in (12), and estimated its parameters for the

brazilian economy, yielding the following results:

Table 3

Parameter

Estimate

Std. Error t-Statistic Prob.

λ -0.543 0.076 -7.141 0.0000

β 1.088 0.110 9.929 0.0000

S.E. of regression 0.036116 Sum squared resid 0.033913 Durbin-Watson stat 1.877362 J-statistic 0.164286

Notes: IGP-M used as inflation measure. Log of the output gap used (HP-Filter). Instruments list can be viewed in Section II.B.

GMM estimation procedure used, with Newey & West HAC covariance matrix estimation

Convergence achieved after 500 iterations.

Adjusted Sample: 1995:2 – 2002:1, with 28 observations.

With regard to this particular test, results for the US economy were3:

π

t= -0.016x

t+ 0.988E

t{

π

t+1}

(0.005) (0.030)

For Europe, it was found that:

π

t= -0.003x

t+ 0.990E

t{

π

t+1}

(0.007) (0.018)

Although our test above has come up with an estimate for

λ

differing considerably from those obtained in Gali and Gertler (1999) for american data, and in Gali, Gertler and Salido (2001) for european data, in general, the evidence found here is roughly the same as in the papers cited above: results of empirical tests on NKPC have been poorer replacing marginal costs by conventional output gap measure (i.e. log-output detrended by HP-Filter). And, at the margin, results encountered for the brazilian sample have become even worse using the standard output gap, in comparison to the tests performed for the other economies.To justify this claim, we have the observation here of a negative

λ

(the same sign as in the test for US and Europe), as well as the finding ofβ

> 1, similarly as new estmates for the US economy. Using results from ours and other previous experiments, we robustly find that results on NKPC estimation, mainly those concerning the sign of parameterλ

, depend heavily on type the instrument chosen to proxy the output gap. Furthermore, the value found for the beta (yielding an estimate greater than one for both US and Brazil, see footnote 3) is very implausible, for agents should not like better the future than the present, a widely accepted economic hypothesis unobserved by a negative impatience rate implied byβ

> 1. In all, the tests with brazilian data shown here may strengthen the conclusion that the use of marginal cost approach is indeed valid to estimate the NKPC. It also reinforce empirical evidence favoring Calvo’s model.IV.B.2 – St ruct ural Form Est imat es

The tests displayed above were performed using reduced form equations. An additional exercise useful at this point is try to estimate equation (12) in the structural form, that is, to test an specification where (in particular) parameter

λ

is written as function ofθ

andβ

. In case of (12), by the use of (11), we have:

E

t{(

θπt

– (1-

θ

)(1-

θβ

)s

t–

θβπ

t+1)Z

t} = 0

(13).

So, our next step is to estimate equation (13), using exactly the same set of instruments used before, which will now allow us to obtain estimates for the structural parameter

θ

. The importance of such parameter is that, in Calvo’s model, it denotes the probability that a given price setter will leave price unchanged in the current period. With knowledge of this parameters, one is able to determine the average time that a certain price is to remain unchanged, which is given by:(1-

θ

)

Σ

kk

θ

k-1= (1-

θ

)

-1(E).

More details on that can be found in Gali and Gertler (1999b). By use of this expression above, we find an interesting empirical measure: how often, in average, agents change their prices. In a comparative basis across countries, we expect the brazilian data to show agents changing prices more frequently than in US and Europe, regions where inflation has let few “ scars” in the recent decades.

Tests performed on equation (13) gave us the following results:

Table 4

Parameter

Estimate

Std.

Error

t-Statistic Prob.

θ 0.593 0.035 16.705 0.0000

β 0.875 0.052 16.814 0.0000

λa

0.330 - -

-S.E. of regression 0.016848 Sum squared resid 0.007380 Durbin-Watson stat 2.738034 J-statistic 0.151415

Notes: IGP-M used as inflation measure. Marginal cost obtained by expression (10*). Instruments list can be viewed in Section II.B.

GMM estimation procedure used, with Newey & West HAC covariance matrix estimation

Convergence achieved after 43 iterations.

Adjusted Sample: 1995:2 – 2002:1, with 28 observations.

TJ test failed to reject the null hypothesis of validity of overidentifying restrictions at 10%, 5% and 1% levels - Chi-Square pdf at 8 d.f..

a

Implied value for λ obtained by replacing estimated θ and β in expression (11).

For the same test, results gotten with US and European: Table 5

US Economy

Results

Euro Economy Results

Parameter

Estimate

Std.

Error

Estimate

Std. Error

θ 0.829 0.013 0.904 0.011

β 0.926 0.024 0.886 0.042

λa 0.047 - 0.021 -a

Implied value for λ obtained by replacing estimated θ and β in expression (11).

In order to assess the robustness of our estimates, and also following Gali and Gertler (1999), we tested (13) imposing

β

= 1:Table 6

Parameter

Estimate

Std.

Error

t-Statistic Prob.

θ -0.353463 0.116952 -3.022291 0.0054

λa -5.182613 - -

-S.E. of regression 0.037159 Sum squared resid 0.037281 Durbin-Watson stat 1.519811 J-statistic 0.191011

Notes: IGP-M used as inflation measure. Marginal cost obtained by expression (10*). Instruments list can be viewed in Section II.B.

GMM estimation procedure used, with Newey & West HAC covariance matrix estimation

Convergence achieved after 40 iterations.

Adjusted Sample: 1995:2 – 2002:1, with 28 observations.

TJ test failed to reject the null hypothesis of validity of overidentifying restrictions at 10%, 5% and 1% levels - Chi-Square pdf at 8 d.f..

a

Implied value for λ obtained by replacing estimated θ and imposition of β = 1 in expression (11).

For the US economy4, our benchmark, results in Gali and Gertler (1999) imposing

β =

1:Table 7

US Economy Results

Parameter

Estimate

Std. Error

θ 0.829 0.016

λa

0.035

-a

Implied value for λ obtained by replacing estimated θ and β in expression (11).

Since GMM is quite sensible to the way one performs normalizations on the estimated moments conditions, similarly as done by the authors, we will test an alternative form of equation (13). This alternative equation, expressed by (14), is characterized to be obtained by trivial manipulation of (13), i.e., being just a another way to write down such formula. So, we estimate (14) using the very same procedure, in order to observe the robustness of estimation results obtained in tests on condition (13).

E

t{(

π

t–

θ

−1(1-

θ

)(1-

θβ

)s

t–

βπ

t+1)Z

t} = 0

(14).

For equation (14), we got, using brazilian data:

Table 8

Parameter

Estimate

Std.

Error

t-Statistic Prob.

θ 0.642 0.047 13.714 0.0000

β 0.902 0.049 18.302 0.0000

λa 0.235 - -

-S.E. of regression 0.027789 Sum squared resid 0.020078 Durbin-Watson stat 2.795883 J-statistic 0.150605

Notes: IGP-M used as inflation measure. Marginal cost obtained by expression (10*). Instruments list can be viewed in Section II.B.

GMM estimation procedure used, with Newey & West HAC covariance matrix estimation

Convergence achieved after 15 iterations.

Adjusted Sample: 1995:2 – 2002:1, with 28 observations.

TJ test failed to reject the null hypothesis of validity of overidentifying restrictions at 10%, 5% and 1% levels - Chi-Square pdf at 8 d.f..

a

Implied value for λ obtained by replacing estimated θ and β in expression (11).

For the same type of test, results for US and European data had been:

Table 9

US Economy

Results

Euro Economy Results

Parameter

Estimate

Std.

Error

Estimate

Std. Error

θ 0.884 0.020 0.918 0.015

β 0.941 0.018 0.914 0.040

λa 0.021 - 0.014 -a

Analogously, imposing

β

= 1:Table 10

Parameter

Estimate

Std.

Error

t-Statistic Prob.

θ 0.699 0.073 9.618 0.0000

λa 0.130 - -

-S.E. of regression 0.027523 Sum squared resid 0.020452 Durbin-Watson stat 2.878300 J-statistic 0.147589

Notes: IGP-M used as inflation measure. Marginal cost obtained by expression (10*). Instruments list can be viewed in Section II.B.

GMM estimation procedure used, with Newey & West HAC covariance matrix estimation

Convergence achieved after 35 iterations.

Adjusted Sample: 1995:2 – 2002:1, with 28 observations.

TJ test failed to reject the null hypothesis of validity of overidentifying restrictions at 10%, 5% and 1% levels - Chi-Square pdf at 8 d.f..

a

Implied value for λ obtained by replacing estimated θ and β in expression (11).

For the US economy5, our benchmark, results in Gali and Gertler (1999) were:

Table 11

US Economy

Results

Parameter

Estimate

Std.

Error

θ 0.915 0.035

λa 0.007 -a

Implied value for λ obtained by replacing estimated θ and β in expression (11).

It is worthwhile at this time to establish some comments on the results shown above. In what refers to parameter

λ

, results robustly indicate a higher estimated value for brazilian economy (comparing to those gotten from US and Europe), with our estimates ranging in general on (0.13,0.33). This is an evidence that the output-gap6 elasticity of inflation is greaterfor Brazil’s economy, implying that, in this country, inflation responds more (generally upwards, we know) to given changes in output gap, in comparison to other developed countries. This is a somewhat intuitive result, for historical reasons, since Brazil has lived periods of huge inflation, and this may institutionally have affected the way inflation (through

price setters) responds to output movements, despite the fact that we cannot rule out the possibility that maybe the difference is to high to be true.

Furthermore, after estimating the structural form equation, in both ways of normalization, the vector (

θ

,β

) of brazilian unrestricted always came with values in a veryreasonable range. The estimated values for

β

were confined in the (0.87,0.91) interval, implying some acceptable levels of agents’ impatience rate, quite in line with estimates from Europe and the US. Meanwhile, estimates forθ

stayed within (0.59,0.65), a somewhat lower level than results obtained with american and european data, but still valid. Trully, we have an explanation for such difference between brazilian and foreign estimates: as one is able to see, in Table 12, that the lower estimated values for brazilianθ

(in both normalizations) imply quite robustly that brazilian price setters, in average, tend to change prices more frequently than its american and european counterparts. As we have stated earlier this results comes acordingly to our expectations. For instance, accordingly to the estimates performed by us and the authors, and using results on equation (14), in a period when european price setters (in average) have changed their prices only once, and the americans roughly less than twice, brazilians would have changed prices more than four times. Such result is firmly backed-up by economic intuition, since we know that inflationary culture is latent in Brazil, a consequence of the long years economic agents were forced to live in a hyperinflationary environment.Table 12

must lie in the interval [0,1]. In the latter case, however, the estimate for

θ

was very robust to the restriction imposed, and the estimates lied within (0.64, 0.70), not much different from the unrestricted estimate of (13).The sticky result obtained in (13), which did not resist to the imposition of

β

= 1, contrasting with american results, proven to be more robust, is indeed something that lead us to seek explanations. One excuse we have is that is sample size asymmetries between the two studies (our and Gali and Gertler’s), with the american work having much more data available - around 37 years of quarterly observations - compared to the 32 quarterly observations within our dataset. We can speculate that this sets a toll into the robustness of our results, because of consistency reasons.Notwithstanding, in the overall, having obtained some reasonable estimates for parameters in the tests performed here, one should be quite satisfied with the results herein mentioned. They should, indeed, be considered as another good evidence for Calvo’s implied NKPC, supporting Gali and Gertler’s argument.

V.

M arginal Costs Approach: The Hybrid NKPC

V.A – M otivating The New Specification

As we pointed out earlier, some of the criticism on Calvo’s derivation of the NKPC is aimed at the purely forward looking agent’s behavior it implies. In fact, NKPC supposes unrealistically that only current and future events in the economy (more specifically, the ones affecting the output gap) will be important in inflation determination. Nevertheless, no single economist, who roughly watches empirical economic events, can feel comfortable with such an idea. It underestimates the phenomenon of persistence in inflation trajectory, which has already been documented by empirical work like Christiano et al.(2001).

In addition, most central banks around the world use inflation models incorporating such feature. In particular, the Central Bank of Brazil is no exception to such rule, with all versions of its inflation targeting model hypothesizing a variant of Phillips Curve which allows for the presence of inertia in inflation stochastic process7. With this regard, inflation

In order to test for the presence of a backward looking component in the inflation trajectory, we run some models for the Brazilian economy, still in the Gali and Gertler’s flavor. In their paper, using Calvo’s framework, they attach to the purely forward looking NKPC a backward looking inflation component, in order to capture the persistence effects in inflationary process.

V.B – Some Theory, Just for The Record

Respecting the same set of assumptions adopted in Calvo’s model, we might now suppose, additionally (in ad hoc way), that some fraction

ω

of firms use an easy rule of thumb to set their prices, based on past information. This is somewhat different from what we had before: a bunch (randomly selected) companies setting prices by solving their profit maximization problem, subject to time-dependent adjustments constraints, using all information available to foresee future economic conditions, mainly, future marginal costs. We shall now classify these firms as Forward Looking (FL), henceforth. In addition to these firms, our new economy has another class of price setters - firms that set prices depending on what they observed in the past – using history-dependent price rules. They constitute the group of Backward Looking firms (BL).In such environment, aggregate prices are determined by the following expressions:

p

t=

θ

p

t-1+ (1-

θ

)p

t*

(15),

p

t* = (1-

ω

)p

tf+

ω

p

tb(16),

where pt* is the restricted aggregate price index, for prices set in the current period, ptf and

ptb are, respectively, new prices for (FL) and (BL) firms. They obey the following rules (let k be

a time-index from period zero to infinity):

p

tf= (1-

θβ

)

Σ

k(

θβ

)

kE

t{mc

t+k}

(17),

p

tb= p

t-1* +

π t-1

(18).

One can observe that ptf is just the optimal price chosen in the purely forward looking

model. It is worth to verify that the (ad hoc) establishment of ptb has an interesting property:

for stationary inflation dynamics, the rule converges to the optimal forward looking price setting rule, as time goes by.

Closing the derivation of this variant of NKPC – called the hybrid Phillips Curve – one is able to obtain the expression below from combining equations (15) to (18):

πt

=

λ

mc

t+

γ

fE

t{

π

t+1} +

γ

bπ

t-1(19),

where

λ

= (1 -

ω

)(1 -

θ

)(1 -

θβ

)

φ

-1,

γ

f=

θβφ

-1,

γ

b=

ωφ

-1,

φ

=

θ

+

ω

[1 –

θ

(1 -

β

)]

.

V.C – Estimating the Hybrid M odel

V.C.1 – St ruct ural Form Est imat es

By the substitution in (19) of

λ

,γ

f andγ

b, as well as the replacement of mct by st8, w eget the following moments conditions, in the structural form:

E

t{(

φπt

– (1-

ω

)(1-

θ

)(1-

θβ

)s

t–

θβπt+1

)Z

t} = 0

(20),

E

t{(

π

t–

φ

-1(1-

ω

)(1-

θ

)(1-

θβ

)s

t–

φ

-1θβπ

t+1)Z

t} = 0 (21).

Unfortunately, our empirical tests on this structural form, for brazilian data, has been disappointing. For neither (20) nor (21) we could estimate the moment condition’s parameters, for we invariantly obtained singular covariance matrices, which violate necessary

boundness condition and impede us to obtain valid estimates. This also happened for other instrument sets than Zt also tested.

One hypothetical explanation is that micronumerosity is showing its ugly head here, setting a huge toll on the estimation procedures. Moreover, it is worth highlighting that when we imposed a restriction that

ω

= 1, the singular matrix problem could be solved for the set of instruments deployed throughout this work (i.e. Zt), but this would not resolve ourproblem.

In all, this is quite bad for empirical reasons, for it would be useful to have further estimates that could (luckily) strengthen our conclusions already reached over θ, β and λ,as well as it could provide (brand new) estimates for

ω

, γb and γf, parameters for which we haveno results whatsoever this far.

In the paper that inspired this current work, Gali and Gertler have only tested the structural form equations, and they never mention anything about reduced form estimation results on the hybrid curve. So, in order to observe empirical evidence on such important issue - the degree of brazilian inflation’s persistence or, if one will, the ‘backwardness’ of the inflationary dynamics in Brazil - we detach for a while from the procedures adopted in Gali and Gertler (1999). From now on, we will be encharged to perform tests on the reduced form of the hybrid NKPC.

V.C.1 – Reduced Form Est imat es

As just stated above, in this sub-section, with will to obtain estimates for important inflation dynamics’ parameters, we mean to test the reduced form of the hybrid curve. In order to do so, and likewise the procedure followed in the previous tests, we will be using the marginal costs approach. From expression (19) we get the following testable equation, substituting mct for our measure of marginal costs percent deviations from its steady-state:

πt

=

λ

s

t+

γ

fE

t{

π

t+1} +

γ

bπt-1

(22).

Through the application of the Iterated Expectations Law in (22), one obtain the next moment condition:

Using the same set of instruments as in our previous tests (Zt), the estimation results of (23)

are shown in Table 13:

Table 13

Parameter

Estimate

Std. Error t-Statistic

Prob.

λ 0.480 0.088 5.429 0.0000

γf

-0.140 0.087 -1.608 0.1203

γb

0.704 0.083 8.445 0.0000

S.E. of regression 0.029469 Sum squared resid 0.021710 Durbin-Watson stat 2.225785 J-statistic 0.158096

Notes: IGP-M used as inflation measure. Marginal cost obtained by expression (10*). Instruments list can be viewed in Section II.B.

GMM estimation procedure used, with Newey & West HAC covariance matrix estimation

Convergence achieved after 47 iterations.

Adjusted Sample: 1995:2 – 2002:1, with 28 observations.

TJ test failed to reject the null hypothesis of validity of overidentifying restrictions at 10%, 5% and 1% levels - Chi-Square pdf at 8 d.f..

In order to gain further interpretability, we compare our estimates with results obtained in Gali and Gertler (1999) for the US economy, and Gali, Gertler and Salido (2001) for the european economy. One should be cautious at this point here, for these authors have estimated only the structural form of the hybrid NKPC, which hampers somewhat the symmetry of the comparison established herein. Nevertheless, it might not completely invalidate it, so we display the “ foreign” results (for both types of normalization) in Table 14 and 15:

Table 14

US Economy Results

Normalization (20) Normalization (21)

Parameter

Estimate

Std.

Error

Estimate

Std. Error

λ 0.037 - 0.015

-γf

0.682 0.020 0.591 0.016

γb

Table 15

European Economy Results

Normalization (20) Normalization (21)

Parameter

Estimate

Std.

Error

Estimate

Std. Error

λ 0.018 - 0.006

-γf

0.877 0.045 0.689 0.044

γb

0.025 0.127 0.272 0.072

The results obtained this far for the hybrid NKPC in the brazilian economy allows us to establish the following parallel to the analogous estimates in the US and european economies. First of all, in the meantime, the

λ

are still much higher for the brazilian economy than for our benchmark economies, which comes very much in line to previous estimates for the same parameter contained in the NKPC specifications tested before (the levels are proportional too).Second, as expected for the historical reasons already mentioned, the brazilian inflationary dynamics was the one with the highest degree of persistence (or inertia, if one will). This might well be a consequence of a “ price indexation culture” present in Brazil: after many years of high inflation, price setters became used to observe past inflation and reset their prices likewise. Maybe this culture or habit has not been left aside yet by a considerable fraction of brazilian price setters, even after the Real Plan implementation (which indeed stabilized prices). In other words, our view is that the highly persistent inflation dynamics in Brazil might be result of sluggish agents’ behavior, who got used to living in a widespread price indexation environment, as was the case for the Brazilian economy in the past.

Third, one bizarre result that we found is the lack of significance in the forward looking component in brazilian inflation process. This could hint to some the possibility that brazilian inflation expectations are, even in the Real era, purely adaptative, implying a high level of irrationality from price setters in Brazil. This last result is very strong, and may force us to go into further tests in order to validate it.

Table 16

Parameter

Estimate

Std.

Error

t-Statistic

Prob.

λ 0.242 0.073 3.318 0.0029

γf

0.968 0.320 3.028 0.0058

γb

(L1) 0.685 0.175 3.914 0.0007

γb

(L2) -0.664 0.192 -3.460 0.0020

Mean dependent var 0.000000 S.D. dependent var 0.000000 S.E. of regression 0.031845 Sum squared resid 0.024339 Durbin-Watson stat 3.176994 J-statistic 0.111940

Notes: IGP-M used as inflation measure. Marginal cost obtained by expression (10*). Instruments list can be viewed in Section II.B.

GMM estimation procedure used, with Newey & West HAC covariance matrix estimation

Convergence achieved after 93 iterations.

Adjusted Sample: 1995:2 – 2002:1, with 28 observations.

TJ test failed to reject the null hypothesis of validity of overidentifying restrictions at 10%, 5% and 1% levels - Chi-Square pdf at 8 d.f..

Table 17

Parameter

Estimate

Std.

Error

t-Statistic

Prob.

λ 0.089 0.034 2.643 0.0145

γf

0.562 0.155 3.614 0.0015

γb

(L1) 0.478 0.136 3.522 0.0018

γb

(L2) -0.650 0.123 -5.290 0.0000

γb

(L3) 0.499 0.061 8.152 0.0000

Mean dependent var 0.000000 S.D. dependent var 0.000000 S.E. of regression 0.025332 Sum squared resid 0.014760 Durbin-Watson stat 3.396762 J-statistic 0.068357

Notes: IGP-M used as inflation measure. Marginal cost obtained by expression (10*). Instruments list can be viewed in Section II.B.

GMM estimation procedure used, with Newey & West HAC covariance matrix estimation

Convergence achieved after 37 iterations.

Adjusted Sample: 1995:2 – 2002:1, with 28 observations.

TJ test failed to reject the null hypothesis of validity of overidentifying restrictions at 10%, 5% and 1% levels - Chi-Square pdf at 8 d.f..

The estimates displayed in Tables 16 and 17 may show us a weird result for the brazilian economy. As we allow a greater number of inflation lags to enter into the hybrid NKPC, some phenomenon occur: (i) the elasticity of inflation with respect to the output gap (marginal cost as a proxy), denoted by the parameter

λ

, shrinks as more lags of inflation are used. In the last test, one can notice that the estimated value comes very close to those estimates for the US and Europe’s economy, though brazilian figures are still higher (possibly for the economic reasons already explained previously); (ii) the forward looking component of inflation expectations becomes significant as more inflation lags are added; (iii) the estimated value for γbinserted into the hybrid NKPC. Perhaps all issues from (i) to (iii) are a symptom of some excluded variable bias in coefficient estimates. This is even more clear in case of (iii), when it seems that γb

(L1) gives back the due credit merited by γb

(L3) on pushing the current inflation movements, when the latter is included in the specification.

Anyway, in the last estimation of (23) performed (which includes three inflation lags) the reasonable estimate for some parameters like

λ

and γf, which come not only in line withprevious brazilian estimates (in other models) but also compatible to international estimated values, may be interpreted as a strong hint that this may be the a nice specification to approximate (i.e. to fit the data on) brazilian inflation dynamics.

Another curious result, and quite robust, we might say, is the negative impact that inflation lagged by two periods has in current inflation, yielding values close to –0.65 in the two last tests. This result lacks intuitiveness. The only explanation found this far for this implied sinusoidal inflation dynamics in Brazil is the possibility that brazilian inflation (in the Real era) displays a mean-revertion property, which impedes it to diverge. However, we shall be conservative now and treat this issue more like a puzzle to be resolved, instead of being satisfied with such explanation (speculation) just given.

VI.

Conclusions

In general, the results obtained in this replication of Gali and Gertler’s experiments, for the Brazilian economy, were supportive for Calvo´ s theory when tests were performed using real marginal costs as proxy for the true output gap, as was done by the authors. This outcome comes in line with those obtained for the both US and european economy, despite some natural differences in estimated parameters. Here, in most tests, we had reasonable parameter values (i.e. estimates lying in a very acceptable range, accordingly to the theory). Considering data deficiencies in Brazil, this is something positive.

On empirical grounds, one key conclusion we could obtain with our tests is the deep and notorious inflationary culture, which is present in Brazil’s economy. Our tests verified that not only inflationary inertia is a key issue in this country, much more than in the US and Europe, but also that brazilian price setters, compared to their american and european counterpart have (in average) habit to change prices much more frequently. In Brazil, one can say that this is a quite “ inflationary” habit, given empirical resistance from price setters to lower their prices. Another evidence of an inflationary culture is the greater sensibility of brazilian inflation to the output gap, when compared to the inflation dynamics in both the US and in Europe. Such conclusion is intuitive, since, in the recent decades, Brazil has suffered from hyperinflationary maladies, contrarily to what happened for the two other regions tested.

Notwithstanding, methodologically, one should not disguise the fact that this work here still needs to be improved in terms of robustness of the results. Some of the parameters estimated, in spite of being in reasonable parameter range, are still varying undesirably. In some tests, results changed more than we wanted it to by altering the normalization of moment’s condition or imposing parameters restrictions.

References

Bogdanski, J., Tom bini, A.A., Werlang, S.R.C., 2 0 0 0 , “ I mpl e me nt i ng I nf l a t i o n Ta r g e t i ng i n Br a z i l ”, Cent ral Bank of Brazil Working Paper #1.

Bogdanski, J., Freitas, P.S., Goldfajn, I., Tom bini, A.A., 2 0 0 1 , “ I nf l a t i o n Ta r g e t i ng i n Br a z i l : Sho c ks , Ba c kwa r d- Lo o ki ng Pr i c e s a nd I MF Co ndi t i o na l i t y ”, Central Bank of Brazil Work ing Paper #24, August .

Christiano, L., Eichenbaum , M., Evans, C., 2 0 0 0 , “ Mo ne t a r y Po l i c y Sho c ks : Wha t Ha v e We Le a r ne d a nd To Wha t End? ”, Handbook of Macroeconom ics.

Clarida, R., Gali, J. and Gertler, M., 1 9 9 9 b, “ The Sc i e nc e o f Mo ne t a r y Po l i c y : a Ne w Ke y ne s i a n Pe r s pe c t i v e ”, Journal of Econom ic Lit erat ure 37 #2, 1661- 1707.

Gali, J., 1 9 9 9 , “ Te c hno l o g y , Empl o y me nt , a nd t he Bus i ne s s Cy c l e : Do Te c hno l o g y Sho c ks Ex pl a i n Ag g r e g a t e Fl uc t ua t i o ns ? ”, Am erican Econom ic Review, March, 249- 271.

Gali, J. and Gertler, M., 1 9 9 9 , “ I nf l a t i o n Dy na mi c s : A St r uc t ur a l Ec o no me t r i c Ana l y s i s ”, Journal of Monet ary Econom ics 44, 195- 222.

Gali, J. and Gertler, M., Salido, J.D.L., 2 0 0 1 , “ Eur o pe a n I nf l a t i o n Dy na mi c s ”, NBER Working Paper # 8218.

Hamilton, J.D., 1 9 9 4 , “ Ti me Se r i e s Ana l y s i s ”, Princet on Universit y Press.

Mankiw, N.G., 2 0 0 0 , “ The I ne x o r a bl e a nd My s t e r i o us Tr a de o f f Be t we e n I nf l a t i o n a nd Une mpl o y me nt ”, NBER Working Paper # 7884.

Newey, W.K., West, K.D., 1 9 8 7 , “ A Si mpl e Po s i t i v e Se mi - De f i ni t e He t e r o s ke da s t i c i t y a nd Aut o c o r r e l a t i o n Co v a r i a nc e Ma t r i x ”, Econom et rica (55), 7 0 3 - 7 0 8 .

Roberts, J.M., 1 9 9 5 , “ Ne w Ke y ne s i a n Ec o no mi c s a nd t he Phi l l i ps Cur v e ”, Journal of Money, Credit and Bank ing Vol. 27 (4), 975- 984.

Sbordone, A.M., 2 0 0 0 , “ Pr i c e s a nd Uni t La bo r Co s t s : A Ne w Te s t o f Pr i c e St i c ki ne s s ”, Inst it ut e of Int ernat ional Econom ic St udies, St ock holm , Sem inar Paper #653, April (revised).

Figure 1. M arginal Cost s and It s Long-Term Trend (HP-Filt er)

This graph shows marginal costs and its trend (by HP Filter)

Figure 2. Sm oot hing Log-Out put By Use of Hodrick Prescot t Filt er

This graph displays log output and natural log output (obtained by HP-Filter)

3.70 3.75 3.80 3.85 3.90 3.95 4.00 4.05

95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02

LOG_MGCOST HP_LOGMGCOST

11.6 11.8 12.0 12.2 12.4 12.6 12.8

95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02