❊♥s❛✐♦s ❊❝♦♥ô♠✐❝♦s

❊s❝♦❧❛ ❞❡

Pós✲●r❛❞✉❛çã♦

❡♠ ❊❝♦♥♦♠✐❛

❞❛ ❋✉♥❞❛çã♦

●❡t✉❧✐♦ ❱❛r❣❛s

◆◦ ✹✶✶ ■❙❙◆ ✵✶✵✹✲✽✾✶✵

❈❤❛s✐♥❣ P❛t❡♥ts

❋❧❛✈✐♦ ▼❛rq✉❡s ▼❡♥❡③❡s✱ ❘♦❤❛♥ P✐t❝❤❢♦r❞

❖s ❛rt✐❣♦s ♣✉❜❧✐❝❛❞♦s sã♦ ❞❡ ✐♥t❡✐r❛ r❡s♣♦♥s❛❜✐❧✐❞❛❞❡ ❞❡ s❡✉s ❛✉t♦r❡s✳ ❆s

♦♣✐♥✐õ❡s ♥❡❧❡s ❡♠✐t✐❞❛s ♥ã♦ ❡①♣r✐♠❡♠✱ ♥❡❝❡ss❛r✐❛♠❡♥t❡✱ ♦ ♣♦♥t♦ ❞❡ ✈✐st❛ ❞❛

❋✉♥❞❛çã♦ ●❡t✉❧✐♦ ❱❛r❣❛s✳

❊❙❈❖▲❆ ❉❊ PÓ❙✲●❘❆❉❯❆➬➹❖ ❊▼ ❊❈❖◆❖▼■❆ ❉✐r❡t♦r ●❡r❛❧✿ ❘❡♥❛t♦ ❋r❛❣❡❧❧✐ ❈❛r❞♦s♦

❉✐r❡t♦r ❞❡ ❊♥s✐♥♦✿ ▲✉✐s ❍❡♥r✐q✉❡ ❇❡rt♦❧✐♥♦ ❇r❛✐❞♦ ❉✐r❡t♦r ❞❡ P❡sq✉✐s❛✿ ❏♦ã♦ ❱✐❝t♦r ■ss❧❡r

❉✐r❡t♦r ❞❡ P✉❜❧✐❝❛çõ❡s ❈✐❡♥tí✜❝❛s✿ ❘✐❝❛r❞♦ ❞❡ ❖❧✐✈❡✐r❛ ❈❛✈❛❧❝❛♥t✐

▼❛rq✉❡s ▼❡♥❡③❡s✱ ❋❧❛✈✐♦

❈❤❛s✐♥❣ P❛t❡♥ts✴ ❋❧❛✈✐♦ ▼❛rq✉❡s ▼❡♥❡③❡s✱ ❘♦❤❛♥ P✐t❝❤❢♦r❞ ✕ ❘✐♦ ❞❡ ❏❛♥❡✐r♦ ✿ ❋●❱✱❊P●❊✱ ✷✵✶✵

✭❊♥s❛✐♦s ❊❝♦♥ô♠✐❝♦s❀ ✹✶✶✮

■♥❝❧✉✐ ❜✐❜❧✐♦❣r❛❢✐❛✳

Chasing Patents

¤

Flavio M. Menezes

EPGE/ FGV

and

School of Economics

Australian National University

Canberra, ACT , 0200

Aust ralia

Rohan Pitchford

RSSS and NCDS

Australian National University

Canberra, ACT , 0200

Aust ralia

March 1, 2001

A bst r act

We examine t he problem faced by a company t hat wi shes to pur-chase pat ents in t he hands of two di¤erent patent owners. Comple-ment arity of t hese pat ents in the product ion process of t he company is a prime e¢ ciency reason for t hem being owned (or licenced) by t he company. We show that t his very same complement arity can lead t o patent owners behaving strat egically in bargaining, and delaying t heir sale t o the company. When t he company is highly leveraged, such ine¢ cient delay is limit ed. Comparat ive statics result s are also obtai ned. Relevant applicat ions include assembly of pat ent s for drug t reat ment s from the human genome, and land assembly.

K ey -wor d s: pat ents, complementarit y, bargaining. J EL C lassi…cat ion: C78, O31, O34.

1

I nt r oduct ion

The lit erat ure on asset ownership (Hart and Moore (1990) and Hart ( 1995)),

predict s t hat complement ary asset s should be owned by t he same part y.

While seemingly simple, t he reason behind t his result is quit e subt le: T wo

asset s are complement ary if t he marginal product of asset -speci…c invest

-ment s by any one part y is zero if t he asset s are not used t oget her. Separat e

ownership of t hese asset s weakens each party’s out side value of t he asset , and

t his increases t he surplus t hat is ext ract ed by t he opposing part y. Ant

ici-pat ing such a problem, each party will invest less in t he speci…c project t han

is desirable. I n cont rast , if t he asset s are owned t oget her, t hen t he owner’s

out side value of t he combinat ion is high. Such an owner has great er incent ive

t o invest ex-ant e.

This result assumes t hat t here is a compet it ive market in asset s prior t o

part ies agr eeing t o do business wit h one-anot her. However, t here are many

cases in which market s for asset s can be quit e t hin. Two (or more) complet ely

separat e owners will oft en make separat e discoveries t hat would – purely

t hrough chance – generat e higher value if t hey were combined. Combining

such discoveries t akes on an import ance of it s own when market s are t hin: An

int erest ing example of t his was t he development of a virus-resist ant papaya

in Hawaii. To be able t o produce and dist ribut e t r ansgenic seeds resist ant t o

t he papaya ring spot virus, it was necessary t o obt ain t he legal right s of ot her

pat ent s t hat would be infringed. Four relevant pat ent s had t o be ident i…ed

and t heir owners cont act ed for negot iat ions. It t urned out t hat “ t he process

of obt aining agreement s from t he pat ent holders was long and arduous. Each

pat ent holder had his own agenda for licensing, ranging from having lit t le

t he most favorable deal.” 1

The problems encount ered wit h papaya are likely t o be minor when

com-pared t o t he recent ly-mapped human genome. M any DNA sequences have

already been pat ent ed. I n fact , t he U.S. Pat ent and Trademarks O¢ ce had

issued more t han 2,000 pat ent s covering gene sequences by t he end of 1999.

New applicat ions will almost cert ainly require mult ipleDNA sequenceswhose

pat ent s are held by di¤erent owners. Will t his pat ent assembly be

accom-plished e¢ cient ly or will it hinder innovat ion and t he discovery of new drugs

or t reat ment s? This quest ion is t he basis of our paper .2

We develop a model t o capt ur et he pr oblem of combining separat epat ent s

(or ot her asset s such as land) when owners can delay sale for st rat egic

ad-vant age. Our main result is t hat complement arit y – while a major reason

for asset s t o be owned t oget her – is also more likely t o lead t o cost ly delay

in pat ent purchase. Grossman and Hart (1980) analyze a similar problem;

a raider will not t akeover a corporat ion because t he ret ur ns fr om any

cor-porat e management improvement s int roduced by t he raider will be capt ured

by exist ing shareholders. The r eason for such ine¢ ciency is t he public goods

nat ure of managing a corporat ion. Grossman and Hart t hen examine several

devices t hat are meant t o avoid t his nonexcludibilit y problem. In cont rast ,

ine¢ ciency in our set t ing arises from st rat egic behavior by pat ent owners.

The land assembly pr oblem has also some common feat ures wit h t he

chasing pat ent s game we analyze; a developer want s t o assemble several

1A s cit ed in “ V irus-Resist ant Papaya in Hawaii: A Sucess St ory,” ISB News

Re-port , January 1999, available at www.plant .uoguelph.ca/ safefood/ archives/ agnet / 1999/ 1-1999/ ag-01-09-99-01.t xt .

2T he pr oblem of pat ent assembly has been recognized in many areas. Lowe (2000), for

example, suggest s t hat “ for invent ions involving mult iple pat ent s held by di¤erent par t ies, t here are high t ransact ion cost s associat ed wit h bargaining over right s, which can lead t o

blocking of commercial development ” in t he healt h care indust ry. His example is t he

parcels of land t o undert ake a project t hat delivers posit ive ext ernalit ies t o

surrounding land owners. When t he developer cannot make a credible

all-or-not hing o¤er, ine¢ ciency is likely t o occur: Exist ing owners will wait in or der

t o capt ure t he rent s result ing from t he complet ion of t he project . 3 In our

model t he source of ine¢ ciency is t he bargaining process, not t he exist ence

of posit ive ext ernalit ies from project complet ion.

While t he st andard lit erat ure on pat ent s4 focuses on t he link bet ween

R&D and pat ent s, we abst ract from t he development st age. T his capt ures

value of combining pat ent s t hat may be generat ed purely t hrough

serendip-ity – and unant icipat ed by t he separat e developers. Our goal is t o st udy t he

mechanism by which mult iple pat ent s are acquired and invest igat e it s

impli-cat ions for e¢ ciency. In our model t her e are t wo pat ent owners, and a t hir d

party who wishes t o combine t hem. Each pat ent owner can choose t o

nego-t ianego-t e sale of nego-t he panego-t ennego-t nego-t o nego-t he nego-t hird parnego-t y immedianego-t ely, or delay negonego-t ianego-t ion

in t he hope of a bet t er deal. The model is described in det ail below.

2

T he M odel

There are t hree players in t he model. A pharmaceut ical company (player 0)

want s t o buy t wo pat ent s, and realize a value v from owning t he ent ire set .

However, each of t hese pat ent s are owned by players – t wo pat ent owners –

3Grossman and Hart ar gue t hat t hese ext ernalit ies could be avoided if t he developer

could hide his int ent ions from t he lot owners. T here is however a large lit er at ure on land assembly. Recent papers eliminat e t he ext ernalit y problem eit her by assuming t hat lot owners can make …nal o¤ers above t heir reservat ion prices, as in Eckar t (1985), or by t aking a cooperat ive appr oach, as in A sami ( 1988). O’Flahert y (1994) st udies urban renewal – when a public aut hor it y has t he power t o buy t he lot s and resell t hem t o t he developer – and shows t hat it is not a good remedy for t he ext ernalit y pr oblem.

4A rrow (1962) is a classical r efer ence on analyzing invent ions t hat r educe pr oduct ion

1 and 2 respect ively. Player i = 1; 2 values it s pat ent at wi. The

pharma-ceut ical company values t he individual pat ent of i at vi; i = 1; 2. We assume

t hat t he value of t he t wo asset s t oget her exceeds t he sum of t he individual

valuat ions, i.e.

v > v1+ v2;

and t hat t he pharmaceut ical company values t he individual pat ent s at least

as much as t he owners, i.e.

vi ¸ wi:

Ideally, t he pharmaceut ical company would like t o engage each of t he

owners t oget her, make a t ake-or-leave-it o¤er wi; i = 1; 2, and realize t he

value v ¡ w1¡ w2. This may not be possible. A pat ent owner may perceive

an advant age from not going t o t he bar gaining t able when t he ot her owner

is present . In ot her words, it might be advant ageous for an owner t o delay

sale, perhaps hoping for a higher price lat er on.

To model t his possibilit y, we assume t here are t wo possible t imes at which

each par ty can go t o t hebargaining t able, ti = n (“ now” ) and ti = l (“ lat er” ),

i = 1; 2. We assume t hat t he pat ent owners i = 1; 2 simult aneously and

non-cooperat ively choose pi t he probability of going t o t he bargaining t able

now, wit h probabilit y (1 ¡ pi) of going lat er. This choice leads t o four

pos-sible event s: Bot h part ies are at t he bargaining t able now, probabilit y p1p2;

party 1 is at t he t able now, and party 2 lat er and vice-versa, probabilit ies

p1(1 ¡ p2) and p2(1 ¡ p1), and; bot h part ies are at t he bargaining t able lat er,

probability (1 ¡ p1) (1 ¡ p2).

We assume t hat once players ar e at t he t able, t hey bargain e¢ cient ly over

t he exchange of pat ent s. This allows us t o examine t he pur e quest ion of how

st rat egic avoidance of bargaining a¤ect s welfare, wit hout biasing result s by

Nash bargaining t o det ermine t he payo¤s t o each player in each event . We

assume t hat t he payo¤ t o an individual in a bargain is generically as follows:

payo¤ =

(t hreat point payo¤ ) + (bargaining share)¢[available surplus - sum(t hreat point payo¤s)].

(1)

Our int erpret at ion t hroughout of t he t hreat point payo¤ of a bargainer is

st andard: it is t he payo¤ if bargaining breaks down complet ely, wit h no

pos-sibilit y of reconciliat ion. Thus, t he overall payo¤ is t he sum of t he t hreat point

payo¤, and a share of t he gains from t rade.

We assume t hat t he pharmaceut ical company is unable t o commit t o

leave t he bargaining t able at t ime n. To do so would not be subgame perfect :

Speci…cally, suppose t hat t he company purchased a pat ent fr om one owner at

dat e n. This agreement yields a posit ive payo¤, and becomes sunk. The t ime

l agreement also yields a posit ive payo¤, and t he pharmaceut ical company

has an incent ive t o st ay at t he t able. Therefore, we only need t o focus on t he

payo¤s of t he two pat ent owners, since only t hese players are able t o make

st rat egic choices in t he model.

Let t he not at ion s (tj; tk) denot e t he payo¤ t o eit her player j 2 f 1; 2g or

k 6= j 2 f 1; 2g, when t he out come of t heir choices of pj and pk are tj 2 f n; lg

and tk 2 f n; lg respect ively. I f all t hree players ar e at t he bargaining t able

at t ime n, so t hat t1= t2= n, t hen i = 1; 2 receive

s (n; n) = wi + ®i ¢(v ¡ w1¡ w2)

in present value dollars, where ®j ¸ 0, §2

j = 0®j = 1, is t he bargaining share

of t he gains from t rade v ¡ w1¡ w2 of player j = 0; 1; 2, in a t hree player

placed on t he next best use of t he pat ent . We assume t hat dat e l payo¤s are

discount ed by t he fact or ± 2 (0; 1), so t hat t he payo¤ t o player i = 1; 2 in

present value t erms from t he t hree player bargain is

s (l; l) = ± ¢(wi + ®i ¢(v ¡ w1¡ w2)).

We can int erpret a higher ± as a longer period of delay bet ween dat es n and

l, or direct ly as a st ronger t ime preference for all players.

Det er minat ion of t he payo¤s for sit uat ions where t here is only one pat ent

holder at t he t able at any given t ime, requires some careful t hought . Suppose

pat ent holder j is at t he t able at dat e l. At t his t ime, pat ent holder k 6= j

has made a bargain wit h t he pharmaceut ical company. T herefore t he t ot al

available surplus at dat e l is v. However, t he company can t hreat en not t o

purchase j ’s pat ent , and just use t he …rst owner’s pat ent , i.e. t he company’s

t hreat point payo¤ is v1. Applying t he Nash bargaining formula (1) above,

yields a present value payo¤ t o player j of

s (l; n) = ± ¢(wj + ¯j ¢(v ¡ vk¡ wj)) ,

where ¯j 2 (0; 1) is t he bargaining share of player j vis-a-vis t he company.

Not e t hat t he company is pot ent ially advant aged because it can ext ract a

t hreat point payo¤ of vk > 0 in t his bargain, due t o t he fact t hat it now holds

pat ent k.

Now suppose j is at t he bargaining t able at dat e n, and k negot iat es at

dat e l. Consider t he agreement bet ween owner j and t he company at dat e

n. The company’s t hreat – should bargaining br eak down – is not t o deal

wit h player j , wait unt il dat e l, and receive payo¤ (1 ¡ ¯k) ¢(vk¡ wk), being

it s share 1 ¡ ¯k of t he gains from t r ade vk ¡ wk in t he deal wit h t he ot her

ant icipat e t hat e¢ cient bargaining will yield t he t ot al value v.5 This yields a payo¤ at dat e n t o player l of

s ( n; l) = wj + ¯j ¢[v ¡ wj ¡ ± ¢(1 ¡ ¯k) ¢(vk ¡ wk)].

The import ant point t o not e is t hat t he pharmaceut ical company’s fut ure

payo¤ from dealing wit h player k alone, a¤ect s t he surplus in t he bargain

at dat e n wit h player j . T hus, t he payo¤s capt ure –in a rigorous way–

int ert emporal compet it ion bet ween t he two pat ent -holders.

Now consider pat ent owner j0s choice of pj at t he beginning of t he game.

The owner ’s expect ed payo¤ is calculat ed by weight ing t he payo¤s derived

above wit h t he pr obabilit ies of each event :

¼j = pj ¢pk ¢[wj + ®j ¢(v ¡ wj ¡ wk) ] (2)

+ pj ¢(1 ¡ pk) ¢[wj + ¯j ¢(v ¡ wj ¡ ± ¢(1 ¡ ¯k) ¢(vk ¡ wk))]

+ (1 ¡ pj) ¢pk¢[± ¢( wj + ¯j ¢(v ¡ vk ¡ wj) )]

+ (1 ¡ pj) ¢(1 ¡ pk) ¢[± ¢(wj + ®j ¢( v ¡ wj ¡ wk))]

3

Solut ion and R esult s

We can derive Nash equilibria in t he model by examining t he derivat ive of

(2). Aft er some simpli…cat ion, t he derivat ive becomes:

d¼j

dpj

= pk¢X + ( 1 ¡ pk) ¢Y (3)

where

X = s (n; n) ¡ s (l; n) (4)

= (1 ¡ ±) ¢wj + (®j ¡ ±¯j) ¢(v ¡ wj ¡ wk) + ± ¢¯j ¢(vk¡ wk) ,

5T hat is, bot h players know t hat bargaining is e¢ cient , and t hat bargaining at dat e 2

and

Y = s (n; l) ¡ s (l; l) (5)

= (1 ¡ ±) ¢wj + ( ¯j ¡ ± ¢®j) ¢(v ¡ wj ¡ wk)

+ ¯j(wk ¡ ± ¢(2 ¡ ¯k) ¢(vk¡ wk))

Pr oposit ion 1 There is ine¢ cient delay in equilibr ium if X < 0 and Y > 0

in the for m of multiple equilibria ( p1; p2) 2 f (1; 0) ; (0; 1) ; (p1; p2) g with

pk = (1 ¡ ±) ¢wj + (¯j ¡ ±®j) ¢(v ¡ wj ¡ wk) + ¯j ¢(wk ¡ ± ¢(1 ¡ ¯k) ¢(vk¡ wk))

(1 + ±) ¢(¯j ¡ ®j) ¢(v ¡ wj ¡ wk) + ¯j ¢(wk ¡ ±(2 ¡ ¯k) ¢( vk¡ wk))

(6)

j 6= k = 1; 2.

Pr oof. > From equat ion (3) , we have d¼j

dpj = 0 where pk = pk =

Y Y ¡ X 2

(0; 1) as X < 0, Y > 0. On subst it ut ion, pk is given by equat ion (6). T he

best response corr espondences of t he owners are given by

pj =

8 <

:

0 for pk > pk

[0; 1] for pk = pk

1 for pk < pk

j 6= k = 1; 2.

This is because if pk > pk, d¼j

dpj = pk ¢X + (1 ¡ pk) ¢Y < 0, as X < 0; Y > 0.

Similarly, if pk < pk, d¼dpjj > 0 as X < 0; Y > 0. To calculat e equilibria,

suppose …rst t hat p2 = 0 < p2. Owner 1’s best response is p1 = 1. Owner

2’s best response t o p1 = 1 > p1 is p2 = 0. Thus, (1; 0) a Nash equilibrium,

as is (0; 1) by a symmet rical argument . Consider t he point (p1; p2). Neit her

owner increases t heir payo¤ from deviat ing, so t hat t his point is also a Nash

Equilibrium. There are no ot her Nash equilibria, since owner 2 will deviat e

from any point (p1; p2) if p16= p1.

First not e t hat delay is always ine¢ cient , because t he t ot al available

by not ing t hat owners 1 and 2 are playing an int ert emporal coordinat ion

game. T he t erm X is t he di¤erence between owner j ’s payo¤ from

bargain-ing now and bargainbargain-ing lat er, condit ional on owner k bargainbargain-ing now (i.e.

X = s (n; n) ¡ s (l; n)). Since X < 0, owner j pr efers t o be absent now when

owner k is present . The t erm Y is t he di¤erence bet ween j ’s payo¤ from

bargaining now and bargaining at t ime l when owner k bargains at t ime l

(i.e., Y = s (n; l) ¡ s (l; l)). Owner j pr efers t o bargain now in t his case. I n

summary, bot h owners would prefer t o be absent from t he t able if t he ot her

player is present ; t hey wish t o coordinat e t o be apart .

The proposit ion as it st ands does not give us su¢ cient insight int o t he

basic mot ivat ion for equilibrium delay; we need t o examine t he st ruct ure of

payo¤s more carefully:

Pr oposit ion 2 Suppose that discounted bilateral bargaining yields a larger

share of sur plus than trilateral bargaining (i.e. ±¯i > ®i, i = 1; 2). Then there

is ine¢ cient delay in t he equilibr ium outcome if patents are ( su¢ ciently)

complementar y, i.e. if either

( i) vi = wi, and ± is su¢ ciently near unity ( precisely, ± > wwii+ ®+ ¯ii( v¡ w(v¡ wii¡ w¡ wkk));

i 6= k = 1; 2); or

( ii) v is su¢ cient ly large.

Pr oof. For case (i), we have X negat ive for ± > wi+ ®i(v¡ wi¡ wk)

wi+ ¯i( v¡ wi¡ wk) and Y

posit ive if ±¯j ¡ ®j > 0. For (ii), ®j ¡ ±¯j < 0 implies from equat ion (4) t hat

X is monot onic decreasing in v, so t hat X < 0 for v su¢ cient ly large. Since

¯j ¡ ±®j > 0, we see from equat ion ( 5) t hat Y is monot onic incr easing in v,

so Y > 0 for su¢ cient ly large v. From Proposit ion (1), t here is delay in all

The int uit ion for Proposit ion 2 is as follows. For part (i), t he

pharma-ceut ical company’s value of a single pat ent is no great er t han t he value t o

t he owner (vi = wi). T hus, t he pharmaceut ical company does not gain much

of an advant age if it purchases a pat ent . This is t rue when t he company is

bargaining wit h only one owner at eit her dat e n or at dat e l. In t he former

case – a deal wit h one owner at dat e n – t he company ant icipat es t hat it does

not have much int ert emporal bargaining power from a fut ure deal. In t he

lat t er case – an agreement wit h one owner at dat e l – t he company holds a

pat ent t hat doesn’t give it much immediat e bargaining power. T he lack of a

st rong t hreat point on t he part of t he company when t here is only one owner

at t he t able, means t hat t he owner is negot iat ing over a larger net surplus.

I n addit ion, t he ant icipat ed share of t his net surplus t o an owner (when t he

ot her is absent ) is larger, even when t he owner must delay it s going t o t he

bargaining t able ( i.e. we assumed ±¯j > ®j). Consequent ly, bot h part ies

would prefer t o be at t he t able alone. From proposit ion 1, t her e is delay in

all t hree equilibria. Wit h part (ii), t here is ine¢ cient delay for analogous

reasons. The t ot al available surplus v is high, t herefore t he gains t o owners

from being alone is also high.

In bot h cases (i) and (ii), t he driving force behind delay is t he degree

of complement arity and t he fact t hat bilat eral bargaining power exceeds t

ri-lat eral bargaining power. Since v > v1 + v2, and ±¯j > ®j, each pat ent

owner has an increased incent ive t o not coor dinat e wit h t he ot her owner. I n

t his way, t he part ies can “ divide and conquer” : By negot iat ing separat ely

– at least wit h some probabilit y – t here is a sunk component t o t he dat e n

agreement . The owners seize a larger share ±¯j > ®j of a lar ge gain from

t rade. For example, if party 1 bargained at dat e n, and received share ¯1,

more of an expect ed pie t han if t hey negot iat e at t he same dat e wit h shares

®1 and ®2.

4

C om par at ive St at i cs

I n t his sect ion we examine t he changes in equilibrium behavior result ing from

changes in some of t he st ruct ural paramet ers. To do so we writ e t he …rst

-order condit ion as a funct ion of pk and of t he exogenous variables. T hat

is,

d¼j

dpj

= f (pk; £ ) ;

where £ = (±; v; vk; vj; wj; wk) is a vect or of exogenous paramet ers.

Not e t hat f (pk; £ ) is decr easing in pk under t he assumpt ions in

propo-sit ion 1, since fpk = X ¡ Y < 0. Thus, t he change in t he equilibrium value

of pk t hat result s from a change in t he paramet er µ 2 £ depends on how

f changes wit h respect t o µ. For example, if we can show t hat f (pk; £ )

increases wit h µ for all values of pk; t hen we can argue t hat t he equilibrium

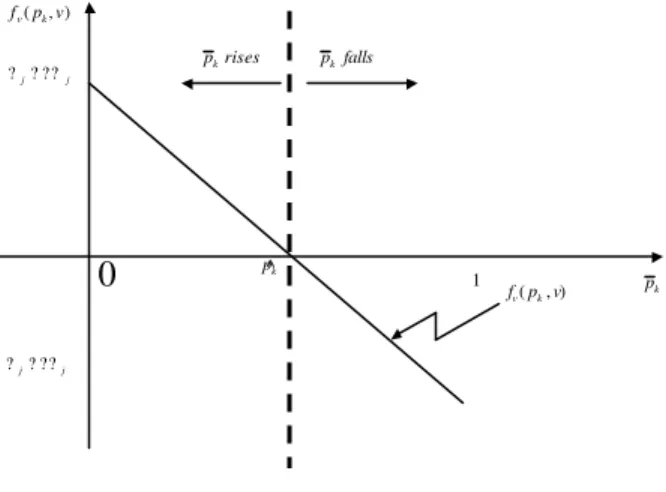

value of ¹pk increases wit h µ as well. This is depict ed in …gur e 1 wit h some

abuse of not at ion where for convenience we writ e f (pk; µ).

In …gure 1 if a rise in paramet er µ leads t o a rise in f , t hen ¹pk rises t o

¹p0k, and if it leads t o a fall in f , t hen ¹pk falls t o ¹p00k. That is, we only need t o

Figure 1: Comparative Statics

k

kp

p, ?pk,??

f

?pk,??

f ''

k

p pk pk'

As a check on int uit ion, consider t he e¤ect of an increase in ±. We would

expect t hat t his leads t o an incr ease in delay. Di¤er ent iat ing f wit h respect

t o ± yields

f± = ¡ 2wj ¡ (®j + ¯j) (v ¡ wj ¡ wk) ¡ ¯j (1 ¡ ¯k) (vk¡ wk) < 0

as expect ed: When ± rises, t hen not only does t he gain from fut ure payo¤s

rise, but t hepharmaceut ical company’st hreat point payo¤ from not t o dealing

wit h j at t ime n is improved (i.e. s (n; l) falls).

The comparat ive st at ics of v are not as direct . Di¤erent iat ing f wit h

respect t o v yields:

fv = pk( 1 + ±) (®j ¡ ¯j) + ¯j ¡ ±®j (7)

which is of ambiguous sign under t he assumpt ion t hat discount ed bilat eral

bargaining power exceeds t rilat eral bargaining power (±¯j > ®j). Figure 2

Figure 2: Comparative Statics of v

k p )

, (p v fv k

k p

) , (p v fv k j j ?? ? ? j j ?? ? ? 1 0 rises

pk pkfalls

^

When ¹pk = 0, fv = ¯j¡ ±®j > 0, and when ¹pk = 1, t hen fv = ®j¡ ±¯j < 0.

Also, fv is decreasing in pk. I t follows t hat fv is increasing below t he value

^

pk where fv = 0, and is decreasing above ^pk. Therefore, ¹pk is increasing for

¹pk < ^pk and decreasing for ¹pk > ^pk. Using t he de…nit ion of ^pk allows us t o

derive t he following proposit ion.

Pr oposit ion 3 Suppose that discounted bilateral bargaining yields a larger

share of surplus than trilateral bargaining ( i.e. ±¯i > ®i, i = 1; 2). Then

ine¢ cient delay decreases (increases) with v if

¯j ¡ ±®j

(1 + ±) (¯j ¡ ®j)

> (< )

(1 ¡ ±) ¢wj + (¯j ¡ ±®j) ¢(v ¡ wj ¡ wk) + ¯j ¢(wk¡ ± ¢(1 ¡ ¯k) ¢(vk¡ wk))

Similar comparat ive st at ics exercises can be accomplished for t he

remain-ing exogenous par amet ers in order t o obt ain speci…c condit ions under which

increases in any of t he variables f vk; vj; wj; wkg may lead t o an increase (or

decrease) in ine¢ cient delay. We omit t he det ails.

5

D iscussion and Ex t ensions

Our aim in t his paper is t o provide a simple bargaining framework t o analyze

t he problem faced by a company who want s t o buy complement ar y pat ent s

from dist inct pat ent owners. Accordingly, several ext ensions are possible and

some are discussed below.

5.1

W ealt h C onst r aint s and E¢ ciency

I n t he analysis above, it was impossible for t he company t o commit – at dat e

n – not t o negot iat e at dat e l. Being able t o commit not t o bargain is an

ext reme version of a commit ment t o be a t ough negot iat or. T he presence of

wealt h const raint s on t he company admit s t he possibility t hat it can credibly

commit t o be a t ougher negot iat or at dat e n. Weexplore t his possibility here.

Suppose t hat t he pharmaceut ical company has at most wealt h W 2 [w1+

w2; v] t o expend on t he purchase of t hepat ent s. T his is possible, for example,

if t he company is su¢ cient ly highly leveraged. Limit ed wealt h means t hat

t he company can o¤er at most W for t he two pat ent s in any agreement s wit h

t he owners. For illust r at ive purposes, suppose t hat wealt h is t he minimum,

at W = w1+ w2. Consider t he bargaining out come in each event . When bot h

owners negot iat e at dat e n, t hey can receive no more t han w1+ w2bet ween

t hem. Since we assume t hat bargaining is e¢ cient (t o focus exclusively on

t he st rat egic incent ives t o delay), t he payo¤ for each part y is s(n; n) = wi

Now suppose t hat only owner 1 is present at dat e n. The company’s

t hreat point payo¤ is t he amount it will receive from a dat e l deal wit h par ty 2.

I n t his circumst ance, 2 receives ± ¢min f w1+ w2; w2+ ¯2(v2¡ w2) g.

There-fore, in t he dat e n agreement wit h t he company, part y 1 receives

s (n; l) = min [w1+ w2; w1+ ¯1(v ¡ w1¡ ± ¢min f w1+ w2; w2+ ¯2(v2¡ w2)g)] .

Consider t he case where part y 1 bargains at dat e l – aft er player 2 reaches

agreement at dat e n. T he wealt h remaining t o t he company for bargaining

purposes is w1+ w2¡ s (l; n) · w1 (where s (l; n) is de…ned symmet rically t o

s (n; l) – wit h subscript s 1 and 2 swit ched). It follows t hat t he payo¤ t o 1 is

0. Finally, if bot h part ies bargain at dat e n, t hey receive s (n; n) = wi. This

gives t he following expect ed pro…t t o player 1:

¼1= p1¢p2¢w1

+ p1¢(1 ¡ p2) ¢s (n; l)

+ (1 ¡ p1) ¢(1 ¡ p2) ¢w1.

Di¤er ent iat ing gives

d¼1

dp1

= p2w1+ (1 ¡ p2) (s (n; l) ¡ w1) > 0.

Therefore, t here is no ine¢ cient delay in equilibrium. The wealt h const raint

serves t o commit t he company t o be a hard bargainer.

Clearly from t he reasoning in t he …rst part of t he paper, if W = v,

t here is ine¢ cient delay. By t he cont inuit y of payo¤s, t here must be some

level of wealt h such t hat ine¢ cient delay is eliminat ed. The presence of a

wealt h const raint on t he company can act as a credible commit ment t o t ough

by st rat egic bargaining behavior by owners. This holds t rue regardless of

t he degree of complement arity bet ween pat ent s in t he company’s product ion

process.

5.2

D et err ence

The analysis t ells us t hat in t he absence of t ight wealt h const raint s, t here

will be ine¢ cient delay. This suggest s an int riguing possibilit y. Suppose

t he pharmaceut ical company faces a …xed cost of ent ering bargaining. T he

delay problem, and t he fact t hat t he part ies divide and conquer, could be

su¢ cient ly severe t hat it is not wort hwhile for t he company t o pursue t he

purchase of pat ent s. This will happen whenever t he company’s expect ed

payo¤ falls below t he cost of ent ering int o t he bargaining process.

5.3

I nfor m at ion G at her ing and R enegot iat ion

Suppose now t hat each player can …nd out whet her t he ot her player is present

at t he bargaining t able at any given t ime. Wit h t his knowledge, a player can

decide whet her it wishes t o commence bargaining or wait unt il lat er t o do so.

I n part icular, not e t hat t his is only relevant at end of dat e n: Eit her player

can avoid making a period n agreement , aft er observing whet her t he ot her

is present , and wait unt il period l.

First consider t he equilibrium (p1; p2) = ( 1; 0) in t he previous model. (I n

t his equilibrium owner 1 chooses t o go t o t he bargaining t able at dat e n

when owner 2 chooses t o go t o t he t able at dat e l and vice versa.) Will

t his cont inue t o be an equilibrium when informat ion gat hering is possible?

Consider player 1’s decision when he arrives at t hebargaining t able, and …nds

t hat player 2 has made t he decision not t o show up. Will player 1 decide

occur, for t he same reason t hat (1,0) is an equilibrium in t he previous model.

By a symmet ric argument (0,1) will also cont inue t o be an equilibrium. Now

consider t he mixed st rat egy ( ¹p1; ¹p2). It is t rivial t o show t hat t here is no

incent ive t o deviat e from t his st rat egy. Suppose t hat bot h players arrive

at t he bargaining t able at dat e n. They choose t he same probabilit y of

exit ing, and bargaining at dat e l, for precisely t he same reason ( ¹p1; ¹p2) was

an equilibrium of t he previous game.

A st andard device t o eliminat e ine¢ ciencies in bargaining is t o int roduce

cost less renegot iat ion. I n t his model, t here is no incent ive for part ies t o

renegot iat e. Once t he company has purchased a pat ent , t he prior owner is

no longer st rat egically relevant .

6

C onclusion

We examine t he problem faced by a company t hat want s t o purchase t wo

complement ary pat ent s from dist inct owners. Our model capt ures t heprocess

by which t hese complement ary pat ent s areacquired and shows t hat ine¢ cient

delay can occur as a result of pat ent owners being st rat egic. While t he

ownership lit erat ure assert s t hat complement ary pat ent s should be owned

t oget her , we show t hat it is precisely t his sit uat ion t hat leads t o ine¢ cient

delay. I ndeed an increase in t he degree of complement arit y (via an increase

in v) will ult imat ely lead t o a higher probabilit y of delay. However when

t he probabilit y of delay is low, an increase in complement arit y leads t o a

reduct ion in t he chance of delay.

As well as changing t he degree of complement arity, we show t hat delay

decreases as t he discount fact or increases. Ext ensions include t he int r

oduc-t ion of wealoduc-t h consoduc-t rainoduc-t s, infor maoduc-t ion gaoduc-t hering and renegooduc-t iaoduc-t ion. I n all

delay can be eliminat ed when t he company has su¢ cient ly low wealt h.

R efer ences

[1] Arrow, K. J. (1962), “ Economic Welfar e and t he Allocat ion of Resources

for Invent ion, ” in: R.R. Nelson, ed., The Rat e and Direct ion of I ncentive

Act ivit y. Princet on: Princet on University Press.

[2] Asami, Y. (1988), “ A Game-Theor et ic Approach t o t he Division of

Prof-it s from Economic Land Development ,” Regional Science and Urban

Eco-nomics 18, pp. 233-246.

[3] Eckart , W. (1985), “ On t he Land Assembly Problem, ” Jour nal of Urban

Economics 18, pp. 364-378.

[4] Grossman, S. J. and O. D. Hart (1980), “ Takeover bids, t he free-rider

problem and t he t heory of t he cor porat ion,” Bell Journal of Economics,

pp.42-64.

[5] Hart , O. (1995), Fir ms, contracts, and …nancial str uct ure. Clarendon

Lect ures in Economics. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press,

Clarendon Pr ess.

[6] Hart , O. and J. Moore (1990), “ Property Right s and t he Nat ure of t he

Firm,” Journal of Polit ical Economy 48(6), pp. 1119-1158.

[7] K amien, M . I. ( 1992), “ Pat ent Licensing” in Handbook of Game Theory,

Vol. 1., Ed. R. Aumman and S. Hart , Elsevier, Amst erdam, Net herlands.

[8] Lowe, J. ( 2000), “ Paying for healt h care R&D: Carrot s and St icks,”

mimeo., availabe at ht t p:/ / www.cpt ech.org/ ip/ healt h/ rnd/ carrot

[9] M azzoleni, R. and R. R. Nelson (1998), “ Economic Theories about

t he Bene…ts and Cost s of Pat ent s,” Jour nal of Economic I ssues 32( 4),

pp.1031-1052.

[10] O’Flaherty, B. (1994), “ Land Assembly and Urban Renewal, ” Regional