❊♥s❛✐♦s ❊❝♦♥ô♠✐❝♦s

❊s❝♦❧❛ ❞❡

Pós✲●r❛❞✉❛çã♦

❡♠ ❊❝♦♥♦♠✐❛

❞❛ ❋✉♥❞❛çã♦

●❡t✉❧✐♦ ❱❛r❣❛s

◆◦ ✸✺✼ ■❙❙◆ ✵✶✵✹✲✽✾✶✵

✧❲❡ ❙♦❧❞ ❛ ▼✐❧❧✐♦♥ ❯♥✐ts✧ ✲ ❚❤❡ ❘♦❧❡ ♦❢ ❆❞✲

✈❡rt✐s✐♥❣ P❛st✲❙❛❧❡s

❏♦sé ▲✉✐s ▼♦r❛❣❛✲●♦♥③á❧❡③✱ P❛✉❧♦ ❑❧✐♥❣❡r ▼♦♥t❡✐r♦

❖s ❛rt✐❣♦s ♣✉❜❧✐❝❛❞♦s sã♦ ❞❡ ✐♥t❡✐r❛ r❡s♣♦♥s❛❜✐❧✐❞❛❞❡ ❞❡ s❡✉s ❛✉t♦r❡s✳ ❆s

♦♣✐♥✐õ❡s ♥❡❧❡s ❡♠✐t✐❞❛s ♥ã♦ ❡①♣r✐♠❡♠✱ ♥❡❝❡ss❛r✐❛♠❡♥t❡✱ ♦ ♣♦♥t♦ ❞❡ ✈✐st❛ ❞❛

❋✉♥❞❛çã♦ ●❡t✉❧✐♦ ❱❛r❣❛s✳

❊❙❈❖▲❆ ❉❊ PÓ❙✲●❘❆❉❯❆➬➹❖ ❊▼ ❊❈❖◆❖▼■❆ ❉✐r❡t♦r ●❡r❛❧✿ ❘❡♥❛t♦ ❋r❛❣❡❧❧✐ ❈❛r❞♦s♦

❉✐r❡t♦r ❞❡ ❊♥s✐♥♦✿ ▲✉✐s ❍❡♥r✐q✉❡ ❇❡rt♦❧✐♥♦ ❇r❛✐❞♦ ❉✐r❡t♦r ❞❡ P❡sq✉✐s❛✿ ❏♦ã♦ ❱✐❝t♦r ■ss❧❡r

❉✐r❡t♦r ❞❡ P✉❜❧✐❝❛çõ❡s ❈✐❡♥tí✜❝❛s✿ ❘✐❝❛r❞♦ ❞❡ ❖❧✐✈❡✐r❛ ❈❛✈❛❧❝❛♥t✐

▲✉✐s ▼♦r❛❣❛✲●♦♥③á❧❡③✱ ❏♦sé

✧❲❡ ❙♦❧❞ ❛ ▼✐❧❧✐♦♥ ❯♥✐ts✧ ✲ ❚❤❡ ❘♦❧❡ ♦❢ ❆❞✈❡rt✐s✐♥❣ P❛st✲❙❛❧❡s✴ ❏♦sé ▲✉✐s ▼♦r❛❣❛✲●♦♥③á❧❡③✱ P❛✉❧♦ ❑❧✐♥❣❡r ▼♦♥t❡✐r♦ ✕ ❘✐♦ ❞❡ ❏❛♥❡✐r♦ ✿ ❋●❱✱❊P●❊✱ ✷✵✶✵

✭❊♥s❛✐♦s ❊❝♦♥ô♠✐❝♦s❀ ✸✺✼✮

■♥❝❧✉✐ ❜✐❜❧✐♦❣r❛❢✐❛✳

“ We sold a million units” -The Role of

Advertising Past-Sales.

Paulo Klinger Mont eiro and José Luis Moraga-González

¤July, 1999

A bst r act

In a market where past -sales embed informat ion about consumers’ t ast es (quality), we analyze t he seller’s incent ives t o invest in a cost ly advert ising campaign t o report t hem under two informat ional assump-t ions. In assump-t he …rsassump-t scenario, a pooling equilibrium wiassump-t h pasassump-t -sales ad-vert ising is derived. Informat ion revelat ion only occurs when t he seller bene…ciat es from t he herding behaviour t hat t he advert ising campaign induces on t he part of consumers. In t he second informat ional regime, a separat ing equilibrium wit h past -sales advert ising is comput ed. In-format ion revelat ion always happens, eit her t hrough prices or t hrough cost ly advert isement s.

JEL cl assi …cat i on: D82, L15, M37

K ey wor ds: two-sided quality uncert ainty, past -sales advert ising, pooling, signalling, herding behaviour

¤We t hank Ramón Caminal, Claudio Landim, St ephen Mart in, Flavio Menezes,

1

I nt r oduct ion

In a casual glance t o a Sunday’s newspaper, one commonly …nds adver-t isemenadver-t s where sellers publicly announce adver-t heir pasadver-t -sales. For example, Alfaguara publishers recent ly insert ed an advert isement int o Spanish news-paper El País where a pict ure of Javier Marías’s novel ent it led Negra espalda del tiempo appeared t oget her wit h t he following capt ion: “ 100.000 copies sold. One hundred t housand possible reasons t o read t his novel” .1 There are

many ot her inst ances where one observe such market ing st rategies. Phar-maceut ical …rms oft en dist ribut e advert isements to report t he percent age of doct ors or dent ist s t hat use certain t reat ment s and healt h product s. Car and mot orbike companies frequent ly invest in publicity t o st ress t hat cert ain model has been the most sold during t he previous mont h or year. Advert is-ing of music records usually emphasize the number of unit s sold. Managers of t heat er plays or movies commonly produce advert isement s report ing t he proceeds obt ained, or t he number of weeks t hat t hey have been performing or on screen. TV and radio programs usually advert ise t he number (or an est imat e) of people who wat ch or listen t o t hem. Finally, amusement parks2

and t ourism managers repeat edly report t he number of t ourist s who consume t heir services.

T he exist ence of t his class of advert isements generat es a number of ques-t ions. On ques-t he parques-t of ques-t he consumers, whaques-t should ques-t hey undersques-t and afques-t er observing (or not observing) an advert isement of t his type? Is t he informa-t ion released useful for informa-the consumers informa-t o make wiser decisions? Suppose informa-t hainforma-t t he informat ion is useful ex ante, does t his necessarily mean t hat buyers will be sat is…ed ex post ? On t he part of t he supply side of the market , one should ask under which condit ions a seller has incent ives t o advert ise it s privat ely acquired past -sales informat ion. Does a seller of a moderat ely demanded product have t he same incent ives t o promulgat e it s market share t han one of a best -seller good? How do t hese incent ives vary wit h t he precision of t he exogenous informat ion consumers have?

To analyze t hese issues, we employ a linear-quadrat ic-normal3two period

model4 similar to Judd and Riordan (1994) whose main feat ures are as

fol-1See El País, December 1998.

2like EuroDisney (Paris) or Port Aventura (Tarragona, Spain) 3normality is not used in t he …rst part of t he art icle.

4as t hose models used in t he lit erat ure on Informat ion Sharing in Oligopoly (see e.g.

lows. A single long-lived seller o¤ers an experience good to two successive …nit e generat ions of consumers wit h equal t ast es. Before t he market opens, Nat ure select s t he quality of t he good and all consumers privat ely receive an imperfect ly informat ive signal about t he t rue paramet er. The seller receives no valuable informat ion. In t he …rst market opening, t he seller, under com-plet e ignorance, set s an init ial price and buyers make t heir demands basing upon t he privat e informat ion t hey possess (t heir noisy signals). First -period sales, which are privately observed by t he monopolist, t hus const it ut e an aggregat e indicat or (or a summary st at ist ic) of t he good’s quality, or equiv-alent ly, consumers’ t ast es. In t he subsequent period, t he seller set s a price as well as decides whet her or not t o init iate a costly advert ising campaign t o report it s past -sales. Finally second-generat ion consumers make t heir pur-chases basing upon all informat ion available t hey have, i.e. t heir privat e signals, t he observed price and t he seen advertisement (if it happens). We assume t hat advert ising is cost ly and reaches all consumers. Also, we assume t hat price hist ory is observable.5

T he analysis is carried out under two scenarios regarding t he informat ion available to second-generat ion buyers. In the …rst scenario, second-period consumers are complet ely uninformed about t he unknown quality paramet er. In cont rast , in t he second scenario we ext end the analysis by allowing for bet t er, but not complet ely, informed buyers.

Our result s are as follows. T he …rst informat ional scenario, i.e. t hat in which second-generat ion buyers are ent irely ignorant , is charact erized by t he fact t hat prices are incapable t o transmit t he privat e informat ion owned by t he seller. Thus, t he equilibrium exhibit s t he charact erist ics of a pooling equilibrium. T he equilibrium we derive is however more int erest ing. We re-fer t o it as a price-pooling equilibrium with past-sales advertising. It consist s of two object s: First , a partition of t he set of possible sales observat ions int o two subset s: t he advert ising subset and t he no-advert ising one. The second object is a pricing funct ion for each subset . If observed sales-dat a fall int o t he advert ising subset , it pays for t he monopolist t o invest in

ad-5T his is an import ant assumpt ion. Indeed, it frees our model from signal jamming

vert ising and quot e t he price t hat would be charged if t here was symmet ric informat ion between t he seller and t he consumers. If sales-dat a fall int o t he no-advert ising subset , it is opt imal for t he seller no t o invest in advert ising and charge t he pooling price, which is not informative at all. Of course, consumers are rat ional and in equilibrium infer t he set of sales-data t hat are not advert ised correct ly. Therefore, when t hey do not observe t he …rm invest ing in advert isement s to report past -sales informat ion, t hey form t he appropriate inferences. Here “ no news” means “ bad news” . T he advert ising set is t herefore larger t han expect ed due t o t he seller’s int ent ion t o avoid t hat consumers form inferences t hat are t oo pessimist ic. Moreover, t he lower advert ising cost s t he larger is t he advert ising set .

T he fact t hat a seller who observes low sales will not volunt arily disclose t his event implies that he would bene…t ex ante if he could credibly commit t o advert ising it s past -sales. We show, however, t hat t he seller prefers not t o commit to release sales informat ion and use t he st rat egy t hat our advert ising equilibrium prescribes.

In t he second part of t he paper, we turn t o an informat ional regime where second-generat ion buyers are bet t er informed. In part icular, consumers of t he second generat ion receive imperfect ly informat ive signals. T his informat ional scenario is charact erized by t he fact t hat prices are capable t o signal t he pri-vat e informat ion possessed by t he seller. The equilibrium we derive exhibit s similar feat ures t o t he one where prices cannot convey any informat ion. The main charact erist ic of our price-signalling equilibrium with past-sales adver-tising is t hat t he seller and t he buyers have symmet ric informat ion for any past -sales realizat ion. For promising observat ions, t he seller …nds it opt imal t o init iat e an advert ising campaign t o report t hem, and t he price is t he one t hat would be charged if t he seller and t he buyers had symmet ric informa-t ion. For unpromising sales-dainforma-t a, informa-t he seller uses a price-signalling sinforma-trainforma-t egy. Moreover, t he lower t he advert ising cost s, t he smaller is the no-advert ising set .

Our research present s several aspect s relat ed t o t he lit erat ure on “ herding behaviour” .6 Since individual signals are less accurat e t han t he summary

st at ist ic which is embedded in t he past -sales, consumers necessarily employ t he informat ion released through t he advert isement s or prices (if signalling occurs). Therefore, it may very well happen t hat consumers purchase a “ lemon” simply because …rst -generat ion consumers received good, but wrong,

signals.7 This fact , so-called “ pat h-dependence” in the herding lit erat ure, is caused by t he very fact t hat buyers do not observe t he ex-post utilit ies of previous customers, but t heir decisions, which are based on t he observed random signals. In our paper, t his e¤ect is clearly more accent uat ed when …rst -generat ion buyers are few. Clearly, t he idiosyncrasy of t he outcomes obt ained is less severe when second-generat ion buyers have corroborat ing informat ion, as in t he second informat ional scenario of our paper.8

T he remainder of t he paper is organized as follows. Next sect ion describes t he model and set s up t he problem. The result s for t he case where second-generat ion buyers are fully uninformed are present ed in Sect ion 3. We ext end t he analysis t o allow for bet t er informed consumers in Sect ion 4. Sect ion 5 concludes.

2

T he m odel

We consider a two period economy where t here is two-sided uncert ainty. A single …rm sells a good of uncert ain quality q t o two successive generat ions of consumers.9 T he quality paramet er q is a zero-mean random variable

distribut ed according t o t he density funct ion f (q): In t his work, we follow Judd and Riordan (1994) and consider the quality q as a t ast e index rat her t han as a paramet er of t echnical superiority. T his perspective allows for t he abst ract ion from t he dependency of quality and cost s. We t hus normalize unit product ion cost t o zero.

A new cohort of N cust omers ent ers t he demand side of t he market each period.10 It is assumed t hat t hey t ake t he quadrat ic ut ility funct ion

U(x; p; q) = (a + q)x ¡ x22 ¡ xp; if they buy x unit s of a product of quality q at unit ary price p: Consumers are short -lived, which implies t hat t hey buy only once and t hat t hey cannot post pone t heir purchasing decisions. When t he market opens, buyers wit hin a cohort may di¤er in t heir informat ion, but

7In t he cinema indust ry t his is very common. Even t hough people agglomerat e at t he

cinemas’ doors t o get t icket s of new …lms, occasionally t he ex-post valuat ion of t he movie is low. Here t his would be a case where realizat ion of q is low whereas realizat ions of signals are high.

8Bikhchandani et al. (1998) report t he success and failure of new product s apparent ly

due t o no object ive reason.

9T he generalizat ion of our model t o more t han two periods is immediat e.

10T he number of consumers of each generat ion could be di¤erent . T his would not a¤ect

t hey are all ident ical ex-ant e. Under perfect informat ion, t hen, t he represen-t arepresen-t ive consumer of eirepresen-t her of represen-t he generarepresen-t ions would demand x = (a + q) ¡ p:11

T he market evolves as follows. At t he beginning, before t he market opens, q is drawn by Nat ure and remains t hereaft er.12 Neit her …rm nor cust omers receive full informat ion about it . Here, seller’s uncertainty is never fully resolved and consumers’ uncert ainty is resolved ex-post , i.e. aft er consump-t ion occurs. Once Naconsump-t ure has chosen consump-t he consump-t asconsump-t e index, all …rsconsump-t -generaconsump-t ion cust omers receive a privat e signal si

1; i = 1; :::; N ; which conveys (noisy)

informat ion about q. More precisely, si

1 = q + ²i1; where q is t he realized

quality level and ²i1 is a zero mean random variable wit h density funct ion

f (²). One may t hink of t his ext ernal informat ion received by consumers t o be a result of t he nat ural e¤ort t hat t he …rm must exert t o int roduce t he good int o t he market (e.g. int roduct ory advert ising and product demonstra-t ions). T hen, under compledemonstra-t e ignorance, demonstra-t he seller sedemonstra-t s his …rsdemonstra-t -period price and …rst -generat ion consumers make t heir purchases. Once t he seller has observed …rst -period sales, he decides on his market ing st rat egy, i.e. on t he price t o be charged t o second-generat ion consumers and on whet her or not t o invest in an costly advert ising campaign t o report …rst -period sales. Finally, second-generat ion buyers may t heir purchases.

We analyze two informat ional scenarios in regard t o t he second period of market int eract ion. In Sect ion 3, we st udy an informat ional regime where second-generat ion cust omers are fully uninformed, i.e. t hey do not have any ext ernal privat e informat ion valuable. In Sect ion 4, we allow for bett er informed consumers. T here, second-generat ion buyers receive imperfect ly in-format ive signals si2 = q + ²i2; i = 1; 2; :::N : Throughout , it is assumed t hat

buyers do not pool t heir privat e informat ion, neit her wit hin nor between co-hort s. Also, we assume t hat cust omers observe t he history of prices charged, but do not observe quant it ies sold in t he past .

Before proceeding further, some import ant observat ions are necessary. The …rst observat ion gives the basis t o t he problem we analyze. Notice t hat …rst -generat ion consumers will demand t he good according t o t heir privat e informat ion. T herefore, realized …rst -period sales embed a summary

statis-11Lat er in t he paper, q will be normally dist ribut ed. T his implies t hat demand can be

negat ive when p > a+ q. As it is commonly argued in t he lit erat ure on Informat ion Sharing in Oligopoly, which usually employs linear-quadrat ic-normal models (see e.g. Vives (1984, foot not e 2)), t he probability t hat demand is negat ive can be made arbit rarily small by choosing t he variances of t he random variables appropriat ely.

tic of …rst -generat ion consumers’ t ast es, which is privat e t o t he seller, and (ex-ant e) valuable for all t he agent s in t he market place, in order t o bett er est imat e t he unknown parameter q. T he fact t hat consumers would be able t o make wiser decisions if t hey observed sales-dat a raises t he quest ion of whet her or not t he seller is int erest ed in spending resources in an advert ising campaign t o report it s sales.

T he second observat ion has t o do with our assumpt ion t hat t he hist ory of prices is observable. Since second-generat ion consumers observe …rst -period prices, t he seller cannot signal-jam buyers’ inferences about t he uncert ain paramet er q by quot ing a part icular …rst -period price. Therefore, our model is a jamming free signal one. T his implies t hat t he int ertemporal feature of t he monopolist ’s problem does not a¤ect it s …rst -period price decision. As a consequence, we can solve t he monopolist problem separat ely. Next we solve for t he seller’s …rst -period decision. Sect ions 3 and 4 are t he core of our analysis where we st udy t he seller second-period market ing st rat egy.

Let us calculat e t he …rst -period demand. First -generat ion consumer i ’s demand, condit ional upon t he privat ely observed signal and any ot her infor-mat ion available t o him, will be

xi1= a + E [q j - i1] ¡ p1;

where - i

1 denot es consumer i ’s informat ion set . Part icularly, in t he …rst

period, - i1= f si1; p1g: Not e t hat even t hough consumers also observe t he price

charged by the …rm in period 1, p1, it is not informat ive at all since t he seller

does not have any private informat ion on q at t hat st age. Therefore - i 1 =

f si1g: We can sum up consumers’ demands t o obt ain t he average aggregat e

demand

X1= a + qN ¡ p1;

where qN = N1

P N

i = 1E [q j -i

1] denot es t he average aggregat e consumers’

expect at ion about the uncert ain paramet er q: Not e t hat , since consumers’ signals are privat e t o t hem and t hey do not exchange informat ion, realized …rst -period sales, X1; are privat e informat ion t o t he seller. Consequent ly,

t he summary statistic qN is known privat ely by t he monopolist . Observe also

t hat qN is a random variable and t hat t he seller can improve it s inferences

on q by calculat ing E [q j qN]; which gives a more precise est imat or of q as

compared t o t he prior E [q]:13 Clearly, t he monopolist may want t o condit ion

it s second-period market ing st rat egy on it s observat ion of qN:

T he monopolist set s p1 t o maximize his expect ed short -run pro…ts, i.e.

t he seller maximizes E [¼1] = E [(a+ qN¡ p1)p1]: T he solut ion of t his problem

is p1 = a2: Realized sales will t hen be X1 = a=2 + qN and pro…ts ¼1 =

a(a=2 + qN)=2:

Not ice t hat all t hat is import ant about the …rst -period in our model is t he informat ion it provides and it s nat ure. Our modelling choice gives more st ruct ure and economic int uit ion t o t he ‡ow of informat ion in t he market -place. As discussed lat er in t he paper, it is also useful to answer some of t he quest ions posed in t he int roduct ory sect ion.

We solve monopolist ’s second-period problem in what follows. We use t he not ion of perfect Bayesian equilibrium. This requires consumers’ decisions t o be opt imal given t he seller’s st rat egy and t heir beliefs about q; and t he seller’s st rat egy t o be a best -reply t o consumers’ actions. Besides, all agent s’ beliefs must conform to Bayes’ rule whenever it applies.

3

T he basic case: Second-gener at ion buyer s

ar e uninfor m ed

We …rst examine t he case where second-generat ion consumers do not pos-sess any valuable ext ernal information. Consequent ly, t hey are complet ely uninformed in advance t he seller set s it s market ing st rat egy. T his is because buyers do not observe …rst -period sales. T heir prior belief is t hen E [q] = 0: This assumpt ion illust rat es a sit uat ion where buyers know t he exist ence of t he product but are complet ely uninformed about it s quality. In Sect ion 4, we ext end t he analysis t o allow for bet t er informed second-period buyers (i.e. t hey will receive ext ernal informat ive signals).

Next we …nd t he monopolist ’s opt imal prices and pro…ts in t he case t hat he does not invest in an advert ising campaign t o report it s past sales, and in t he case which he does. We assume that t he cost of t he advert ising campaign is c > 0:

dist ribut ions wit h variances ¾2

q and ¾2² respect ively. Then, …rst -period aggregat e

de-mand would equal X1 = a + ±1(q + N1

P N

i = 1²i1) ¡ p1; wit h ±1 = ¾2q=(¾2q + ¾2²): Once

sales have been realized, t he seller knows X1 and t herefore can comput e t he number

qN = (X1 ¡ a + p1)=±1 = q + N1

PN

i = 1²i1; which is an unbiased est imat or of q: In

fact , qN is a random variable normally dist ribut ed wit h cent er at zero and variance ¾4

q

( ¾2

q+ ¾2²)2(¾

2

Suppose t hat t he seller does not invest resources t o advert ise X1: Then, in

t he second period, every buyer’s set of informat ion cont ains only t he observed price, i.e. - i

2 = f p2g for all i :14 As a result , each cust omer’s demand will be

ident ical. Therefore, average aggregat e demand will be

X2= a + q2N ¡ p2; (1)

where q2N = N1

P N

i = 1E [q j p2] = E [q j p2]:

Even t hough buyers may t ry t o infer t he …rm’s past -sales X1basing upon

t he observed price p2, in what follows, we show t hat if t he inference rule is

Bayesian, t hen t he price is incapable t o t ransmit such an informat ion here. In other words, t he opt imal price is uncorrelat ed with qN because no inference

rule can be part of an equilibrium. To see t his, suppose t hat buyers made inferences according t o t he rule p2= Á(qN) : If t he monopolist charges p t hen

aggregat e demand is

X2= a + E [q j Á(qN) = p] ¡ p:

Therefore, second-period expect ed pro…ts, E [¼2j qN], do not depend on qN:

E [¼2j qN] = (a + E [q j Á(qN) = p] ¡ p)p: (2)

Hence, t he opt imal price ¹p, i.e. t he price t hat maximizes (2) does not depend on qN eit her, i.e. it is not a random variable. Therefore, in equilibrium

E [q j p2] = E [q] = 0 and ¹p = a=2:

L em m a 1 Suppose that the seller does not advertise its past-sales. Then, the unique second-period equilibrium price is pc

2= a2; which gives pro…ts ¼ c

2= a

2

4.

Even though cust omers are rat ional and sophist icat ed and t herefore, bas-ing upon t he observed price, may want t o infer t he value of X1 (and hence

t hat of qN), we have seen above t hat no inference rule can be an equilibrium.

The reason for t his is t he typical one in signalling models. If buyers inferred seller’s privat e informat ion from the price, t hen any “ type” of monopolist , by means of his pricing behavior, would have t he same incent ives to induce an incorrect belief on t he part of consumers wit h t he int ent ion t o make higher pro…ts. Consumers underst and t hese incentives t hat any “ type” of seller has,

14Not ice t hat alt hough second-period consumers also observe t he …rst -period price, t his

and t herefore ant icipat e t hat if t hey made purchases according t o an expec-t aexpec-t ions rule such as qN = ' (p2); t hey would be dissat is…ed aft er consuming

t he good almost surely. As a result , t hey should expect any quality after ob-serving any price. In equilibrium, consumers will disregard any informat ion conveyed t hrough t he price so t hat t heir post erior belief equals t heir prior, for all p2: This indeed causes t he price t o be uncorrelat ed wit h t he seller’s

past -sales.

T he pooling nat ure of this equilibrium (price does not depend on qN)

here st ems from t he fact t hat consumers do not have ext ra sources of in-format ion. In a relat ed paper, Judd and Riordan (1994) demonst rat e t hat when consumers have informat ion of t heir own, t hen signaling may occur in equilibrium. In Sect ion 4 we ext end our analysis t o allow for t his possibility.15

Suppose now that t he monopolist advert ises it s past -sales. If t his hap-pens, buyers calculat e qN and become as well informed as t he …rm. In t his

case, second-period consumers’ informat ion set is - i

2 = f qNg = I2; for all i .

Suppose t hat t he …rm charges p: T hen, consumers’ average aggregat e belief will be q2N = E [q j qN; p2= p]: Since t he price does not add any ext ra

infor-mat ion q2N = E [q j qN]: Then average demand will be X = a + E [q j qN] ¡ p

and the monopolist select s it s price p2 t o maximize expect ed second-period

pro…ts

E ¼2= (ap ¡ p2+ pE [q j qN]) ¡ c:

The opt imal price is t herefore

p = a + E [q j qN]

2 :

By subst it ut ing t his price int o t he pro…t funct ion, we obt ain ¼2= p2¡ c:

L em m a 2 Suppose that the seller advertises its past-period sales. Then the unique second-period equilibrium price is pr

2 = (a + E [q j qN])=2 and the

optimal second-period pro…t is ¼r

2= (a + E [q j qN])2=4 ¡ c:

15In t he Indust rial Organizat ion lit erat ure, however, t here are many models where prices

We can est ablish a comparison between t he pro…ts t he seller obt ains when he invest s in advert ising to report its past-sales, and t he pro…ts he makes when he does not . It is easily seen t hat ¼r

2> ¼c2 if and only if

(a + E [q j qN ])2¡ 4c ¡ a2> 0

Or

4c < 2aE [q j qN] + E2[q j qN]: (3)

Clearly, whet her or not t he seller obt ains higher second-period pro…ts by advert ising past -sales depends on t he observed X1; or, in ot her words, on

t he realizat ions of qN: One might t hen be t empt ed t o t hink t hat t he seller

will only init iat e a publicity campaign t o report X1 whenever t he inequality

in (3) holds, i.e. when ¼r

2> ¼c2: But if t his were so, t hen rat ional consumers

should t ake t his int o account , and whenever t hey did not observe advert ising, t hey should make t he appropriat e inferences. This makes t he problem very int erest ing since t he mere fact t hat t he …rm does not invest in advert ising is informat ive for t he consumers: here “ no news” means “ bad news” .

In what follows we charact erize and analyze t he exist ence of what we called pooling equilibrium with past-sales advertising. In words, it consist s of a part it ion of t he set of past -sales observat ions int o two subset s: one for which t he monopolist …nds it opt imal t o invest in an advert ising campaign t o report past -sales, and anot her where t he seller prefers t o conceal it s privat e informat ion. For each subset , the monopolist employs di¤erent pricing rules. First , we formally de…ne an advert ising policy. Then, we de…ne t he equi-librium wit h past -sales advert ising and charact erize it .

D e…nit ion 1 An advertising policy is a set A ½ R such that f ! 2 - ; qN (! ) 2 Ag 2

A .

D e…nit ion 2 An advertising equilibrium is an advertising policy A and a pricing function p (qN) = p(A)ÂA(qN) + p(Ac)ÂAc(qN) ; where ÂC denotes

the characteristic function of the set C; such that: ( a) p(A) (respectively p(Ac)) is optimal if q

N 2 A (respectively Ac).

T heor em 3 Suppose that the cumulative distribution function of qN is strictly

increasing. Then there are ¹ ; u and v such that the optimal advertising policy is A = R n (u; v), where

E [q j qN 2 [u; v]] = ¹ ;

u = ¡ a ¡ p 4c + (a + ¹ )2; and v = ¡ a + p 4c + (a + ¹ )2:

P r oof. Suppose B ½ R is an advert ising policy. As we have seen before, if t he …rm advert ises previous sales, t he opt imal price is p = a+ E [qjqN ]

2 . If t he

…rm does not advert ise and charges p, consumers infer t hat q¡ 1N (Bc) occurred

and hence t he average demand is X2 = a + E [q j qN¡ 1(B

c) ]¡ p. T herefore,

t he opt imal price if t he …rm does not advert ise is p = a+ E [qjq

¡ 1 N (B

c)]

2 . Firm’s

pro…ts are t hen

¼= Ã µ

a + E [q j qN ]

2

¶2

¡ c !

ÂB + µ

a + E [q j q¡ 1N (Bc)]

2

¶2

ÂBc: (4)

To save on not at ion, writ e x = E [q j qN ] and y = E [q j qN¡ 1(Bc) ]: T he …rm

will advert ise qN if and only if (a + x) 2

¡ 4c ¸ (a+ y)2: Equivalent ly, whenever

ja+ xj ¸ p 4c + (a + y)2. That is, for all x 2 R n(¡ a¡ p 4c + (a + y)2; ¡ a+

p

4c + (a + y)2). T herefore B is opt imal if and only if

B = R n (¡ a ¡ p 4c + (a + y)2; ¡ a + p 4c + (a + y)2)

and

y = E [q j qN 2 (¡ a ¡

p

4c + (a + y)2; ¡ a + p 4c + (a + y)2)]:

The last equat ion allows us t o det ermine y. De…ne u = ¡ a ¡ p 4c + (a + y)2

and v = ¡ a + p 4c + (a + y)2. Then, y must solve t he implicit equat ion

y = R

qN2 (u;v)q dP (! )

P (qN 2 (u; v))

: (5)

We may subst it ut e E [q j qN] for q if desired. To prove t he exist ence of such

a y consider the funct ion g : R ! R,

g(y) =

R

qN2

³

¡ a¡p4c+ (a+ y)2;¡ a+p4c+ (a+ y)2

´ q dP (! )

P ³

qN 2

³

¡ a ¡ p 4c + (a + y)2; ¡ a + p 4c + (a + y)2

The denominat or is never zero since t he dist ribut ion of qN is strict ly

increas-ing. Therefore g(¢) is a cont inuous funct ion. Since limy! 1 g(y) = ¡ 1 and

limy! ¡ 1 g(y) = 1 t here is a ¹ such t hat g (¹ ) = 0. Q.E.D.

R em ar k 1 The solution for c = 0 is delicate since the set Ac will be a

zero measure set. Then Bayes’ rule is not well de…ned when Ac occurs. I f

consumers for instance consider that E [q j qN] = ¡ a when they do not

observe past-sales advertising, then, in equilibrium, the …rm almost always advertises.

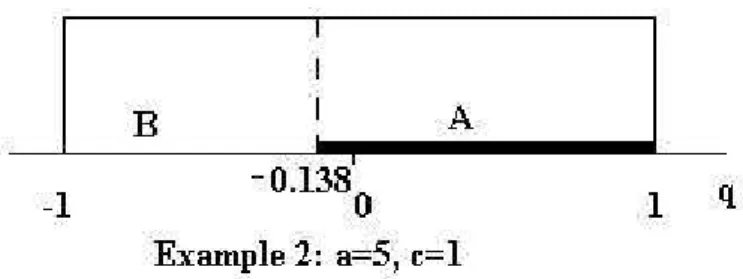

Figure 1 illust rat es Theorem 3. In equilibrium, t he seller …nds it opt imal t o invest in past -sales advert ising whenever qN lies in t he set A: If t his occurs,

t he accompanying price obviously equals t he price t hat he would charge in t he case t hat t here was symmet ric informat ion in t he market , i.e. p = (a + E [q j qN])=2. Ot herwise, t he seller gains by concealing his privat e informat ion

(subset B ): In such a case, t he accompanying price is a pooling price in t he sense t hat any “ type” of seller not invest ing in advert ising charges t he same price, i.e. p = (a + E [q j q¡ 1N (B )])=2: Not ice t hat values of qN falling at

t he left of u imply t hat demand is probably negat ive. Since E [q j qN] is a

monot onic funct ion of qN; t he monopolist init iates t he advert ising campaign

whenever he believes t hat t he good is of relat ively high quality. Not ice also t hat t he no-advert ising set is non-empty provided t hat advert ising cost is posit ive. Therefore, cost ly full revelat ion never occurs.

Figure 1: Past -sales advert ising (A) and no-advert ising (B) subset s

Figure 1: Figure 2: Advert ising (A) and no-advert ising (B) subset s.

suppose t hat …rst -generat ion consumers signals are such t hat qN = q; i.e.

t he seller is fully informed about q aft er …rst -period. From equat ion (5) we obt ain

¹ =

Rminf 1;vg

maxf ¡ 1;ugxdx

min f 1; vg ¡ max f ¡ 1; ug =

min f 1; vg2¡ max f ¡ 1; ug2 2(min f 1; vg ¡ max f ¡ 1; ug) = min f 1; vg + max f ¡ 1; ug

2 :

Consider t he following examples.

Example 1: If 4c ¸ 1 + 2a we have t hat ¹ = 0, u = ¡ a ¡ p4c + a2 ¡ 1

and v = ¡ a + p4c + a2 ¸ 1 are solut ions. Thus, in t his case advert ising

never occurs. The reason is that publicity is t oo costly here.

Example 2: Let us suppose now t hat 4c < 1 + 2a and for de…nit eness t hat a > 1: T hen u ¡ 1; v = (¡ 1 ¡ 2a + 2p (1 ¡ a)2+ 12c)=3 2 (¡ 1; 1)

and ¹ = (v ¡ 1)=2: If a = 5 and c = 1; advert ising occurs if q > ¡ 0:1389 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Figure 3: Advert ising (A) and no-advert ising (B) subset s.

do not compensat e for the advert ising cost . To t he left of ¡ 0:5 consumers beliefs bene…ciat e t he seller and consequent ly advert ising does not occur.

Observe t hat in general t he set of events for which advert ising occurs shrinks as c increases. In fact, if c is very large relat ive t o a; advert ising never occurs.

A nat ural quest ion arises now. Suppose t he seller could commit t o release it s privat e informat ion before observing it . Would he do it or rat her prefer t o decide after observing t he performance of it s good in t he market ? The following result st at es t he seller prefers our pooling equilibrium with past-sales advertising.

T heor em 4 The seller’s expected pro…t is higher when he waits to observe his …rst-period sales and makes his advertising decision contingent on this observation, as compared to the pro…ts that he obtains when he commits to deliver past-sales information at the commencement of the market interac-tion.

P r oof. We need t o compare expect ed pro…ts when t he …rm commit s t o reveal it past -sales, i.e.

¼r2= E

µ

a + E [q j qN ]

2

wit h t he expect ed pro…t obt ained by employing t he st rat egy prescribed by our pooling equilibrium wit h past -sales advert ising. If t his lat t er case, expect ed pro…t is, using (4):

¼w = E " Ã µ

a + E [q j qN]

2

¶2

¡ c !

ÂB + µ

a + E [q j Bc]

2

¶2

ÂBc

#

where B is t he opt imal advert ising set . We see from t he proof of t heorem 3 t hat

B = (

! 2 - ; µ

a + E [q j qN ]

2

¶2

¡ c ¸ µ

a + E [q j Bc]

2

¶2)

:

Thus we have t hat

¼w = E "

max ( µ

a + E [q j qN]

2

¶2

¡ c; µ

a + E [q j Bc] 2

¶2) #

¸ E µ

a + E [q j qN]

2

¶2

¡ c = ¼r2:

Q.E.D. . In our model, “ herding” on t he part of the consumers necessarily occurs. It happens as a result of t heir rat ional behaviour: buyers always want t o employ t he informat ion released because it allows t hem t o comput e bett er est imat es of q. In equilibrium, t he seller ant icipat es consumers’ behavioral rules and chooses it s market ing st rat egy accordingly. When seller observes t hat it s product is not a best -seller, he prefers t o avoid buyers’ herding and t herefore conceals past -sales informat ion. Ot herwise, he is int erest ed in help-ing herdhelp-ing t o occur and does so by init iat help-ing a publicity campaign t o report it s past -sales.

bet t er t han “ following t he crowd” . However, t heir decisions will t urn t o be wrong ex-post consumpt ion. It is well known t hat t he success or failure of new product s may very well depend on non-cont rollable market forces such as consumers ext ernal signals.16 In our pooling equilibrium wit h past -sales advert ising, t he seller exploit s t he informat ion asymmet ry in it s own int erest by let t ing consumers to herd or not .

In what follows, we ext end t he analysis t o allow for bet t er informed second-generat ion consumers. Unfort unately, we have not been able t o carry out an analysis as general as before regarding t he distribut ion funct ions of t he random variables. From now on, we assume t hat all variables are nor-mally and independent ly dist ribut ed as follows: q » N (0; ¾2

q); ²i1» N (0; ¾2²1);

²i

2 » N (0; ¾2²2): According t o t his, the private informat ion t o t he …rm aft er

…rst -period int eract ion is qN = ±1(q + N1

P N

i = 1² i

1); where ±1= ¾2

q

¾2 q+ ¾2² 1:

4

Ext ension: Second-gener at ion consumer s ar e

bet t er infor med.

The purpose of t his Sect ion is t o test t he robustness of our result s when consumers are bet t er informed. In t he preceding Sect ion, we have analyzed a sit uat ion where prices are incapable t o t ransmit any informat ion. Here, we t urn to a framework where prices can signal past -sales informat ion.

Assume t hat second-period consumers exogenously receive ext ra informa-t ion abouinforma-t informa-t he unknown qualiinforma-ty parameinforma-t er informa-t hrough informa-t he signals si

2 = q + ²i2;

i = 1; :::; N : As Judd and Riordan (1994) show, a signalling equilibrium does exist when consumers have an ext ra piece of informat ion. Signalling emerges due t o t he fact t hat buyers have corroborat ing informat ion of t heir own (here t heir privat e signals). In what follows, we charact erize such an equilibrium. We proceed following t he same st eps as above.

Suppose …rst t hat t he monopolist conceals t he value of X1. Then,

con-sumer i ’s second-period informat ion set is - i2= f si2; p2g; i = 1; :::; N : Suppose

t he …rm charges ¹p: Then second-generat ion consumer i ’s demand will be xi2= a + E [q j si2; p2= ¹p] ¡ ¹p:

16A rest aurant may be crowded cert ain day while anot her rest aurant locat ed just around

As in t he previous sect ion, consumers may t ry t o infer past -sales upon t he observed price. As it is usual in linear-normal-quadrat ic models, we focus on t he case where agent s employ linear rules for t heir decisions.17 Suppose t hat

consumers make inferences using t he linear rule p2= ®+ ¯ qN; ¯ 6= 0: Since all

variables are normally dist ribut ed, t here are u and v such t hat E [q j si

2; qN] =

usi

2+ vqN:18 In addit ion, t here is h such t hat E [si2j qN] = E [q j qN] = hqN:19

The following result will be useful in what follows. L em m a 5 It is true that uh + v = h:

P r oof. E [q j qN] = E [E [q j si2; qN] j qN] = E [us2i + vqN j qN] = uE [si2j qN]+

vqN = uE [q j qN] + vqN: Thus E [q j qN] = v=(1 ¡ u)qN = hqN: Hence

v = (1 ¡ u) h ending t he proof. Q.E.D.

Wit h t he help of t his Lemma we can comput e t he average aggregat e demand:

X2= a +

u N

N

X

i = 1

si2+ v¹p ¡ ® ¯ ¡ ¹p:

T he …rm maximizes expect ed pro…ts condit ional on it s informat ion set I2= f X1g = f qNg; t hat is

E ¼2= ¹p

µ

a + uE [q j qN] + v

¹p ¡ ® ¯ ¡ ¹p

¶ :

Therefore, t he opt imal price is

pc= a + uhqN ¡ v®=¯ 2(1 ¡ v=¯ ) :

Since t he cust omers’ inference rule must be correct in equilibrium, it must be the case t hat

® = a ¡ v®=¯

2(1 ¡ v=¯ ) and ¯ =

uh

2(1 ¡ v=¯ ): (6)

17See e.g. Judd and Riordan (1994). 18Explicit ly, u = ¾2² 1¾2q

¾2

² 1¾2q+ N ¾2q¾2² 2+ ¾2² 2¾2² 1 and v =

u ¾2 ² 2

±1¾2² 1:

19Namely, h = ¾2q

Solving t he preceding syst em of equat ions (6) we obt ain ¯ = (h + v)=2 and ® = a (h + v) =2h: So t he opt imal pricing rule is

pc2= a (h + v)

2h +

h + v 2 qN =

h + v

2h (a + hqN): (7) Equilibrium pro…ts are easily comput ed:

¼c2= uh h + v(p

c 2)

2

= u (h + v)

4h (a + hqN)

2

: (8)

The following lemma summarizes:

L em m a 6 Suppose second-generation consumers exogenously receive infor-mative signals si

2= q + ²i2; i = 1; :::; N : Suppose also that the seller does not

advertise his past-sales. Then, there exists a linear separating equilibrium where the …rm charges the price given by (7) and obtains pro…ts given by (8). Not ice t hat t he coe¢ cient of qN is posit ive, i.e. h+ v > 0: This means t hat

t he price is posit ively correlat ed t o past -sales. T he higher t he observat ion of qN (hence t he …rm’s est imat ion of q), t he higher is t he price charged

in t he separat ing equilibrium. Since consumers’ inference rule is correct in equilibrium, higher prices signal great er past -sales, and hence higher …rm’s expected quality.20

We now invest igat e t he opt imal pricing rule and pro…ts when t he …rm invest s in an advert ising campaign t o report it s past -sales. When consumers are informed about t he value of X1; t hey can comput e qN: T herefore, on

average, t hey will demand

X2= a +

u N

N

X

i = 1

si2+ vqN ¡ p2:

Expect ed pro…ts will be

E ¼= p2(a + uhqN + vqN ¡ p2) ¡ c = p2(a + hqN ¡ p2) ¡ c

20An int erest ing observat ion is t hat when ¾2

²2 approaches in…nity, i.e. when

second-period signals become less and less informat ive, t he coe¢ cient of qN converges t o zero.

since uh + v = h (see Lemma 5). T he equilibrium price maximizes t he previous expression and is t herefore21

pr2= a + hqN

2 : (9)

As before, paramet ers ® and ¯ must be such t hat ® = a=2 and ¯ = h=2: Equilibrium pro…ts are in this case

¼r2= (pr2)2= µ

a + hqN

2 ¶2

¡ c: (10)

T he following Lemma summarizes:

L em m a 7 Suppose that the seller advertises its past-period sales. Then the unique second-period equilibrium price is pr

2 = (a + hqN)=2 and the optimal

second-period pro…t is ¼r

2= (a + hqN)2=4 ¡ c:

We are now in a posit ion to study under which condit ions it pays for t he seller to init iat e an advert ising campaign t o report it s sales. Essentially, in t he case under considerat ion, t he seller possesses two alt ernat ive met hods t o reveal past -sales. One involves signalling act ivit ies. The ot her involves an advert ising campaign. Int uit ively, the seller will select t he cheapest de-vice among t he possible ones. The fact t hat in a separat ing equilibrium consumers correctly infer seller’s past -sales considerably simplify t he com-put at ion of our separating equilibrium with past-sales advertising. Indeed, if t he …rm advert ises it s past -sales, t he opt imal price is pr = (a + hq

N)=2: On

t he contrary, if sales information is not delivered, consumers suppose t hat t he pricing funct ion is pc= u(h + v)(a + hq

N)=2h: In bot h cases, consumers

are fully informed. Then, t he …rm will simply initiat e a publicity campaign t o report past -sales if and only if doing so is cheaper t han signalling t hrough price, i.e. ¼r

2¡ c ¸ ¼c2: T his inequality amount s t o

(a + hqN)2¸ 4c +

u(h + v)

h (a + hqN)

2:

Collect ing t erms and simplifying, we obt ain t hat advert ising occurs if qN does

not lie on t he set µ

¡ a h ¡ 2

r

c

h(h(1 ¡ u) ¡ uv); ¡ a h + 2

r

c

h(h(1 ¡ u) ¡ uv) ¶

: (11)

21Not ice t hat pr

2< pc2for all qN > 0: T his fact exhibit s t he usual upward price dist ort ion

T heor em 8 Suppose second-generation consumers exogenously receive in-formative signals si

2 = q + ²i2; i = 1; :::; N : Then there is a signalling

equi-librium with past-sales advertising where (a) the seller advertises X1 i¤ qN

does not fall in set 11 and charges price 9, and (b) the seller conceals the value of X1 i¤ qN lies on set 11 and charges the separating price 7.

Figure 4 illust rat es t his result . For the following paramet er values a = 20; N = 2; c = 300; ¾2q = 5; ¾2"1 = 1; and ¾

2

"2 = 1; t he t hinner line represent s

t he pro…ts obt ained when t he seller invest in an advert ising campaign t o report it s sales. The t hicker line represents t he …rm’s pro…ts when signalling occurs. It is clear t hat for high values of past -sales observat ions, it pays for t he seller t o advertise rather t han employ t he price as t he device t o t ransmit past -sales informat ion. The int uit ion is that t he necessary price distort ion t o do t he lat t er is higher t he great er is qN: Indeed, t he dist ort ion

is pc

2¡ pr2= v(a + hqN)=2h > 0; which increases wit h qN: On t he ot her hand,

if qN is low, then it pays for t he seller not t o invest in advert ising and use

t he price as a signalling device. Our separat ing equilibrium wit h past -sales advert ising gives t he highest at t ainable pro…ts t o t he seller: if past -sales observat ions fall t o t he right of t he point where t he two pro…t curves cross, advert ising occurs. Ot herwise, signalling happens.22

Again, in our signalling equilibrium wit h past -sales advert ising herding occurs. Irrespect ive of whet her advert ising happens or not , in equilibrium, consumers are always informed about t he average tast e of t heir predeces-sors, which induces rat ional herding behaviour on t he part of t he consumers. However, since here buyers have corroborat ing informat ion of t heir own, t he e¤ect s of herding are more moderat e.

5

Conclusions

We would like t o answer the quest ions posed in t he int roduct ory sect ion t o conclude t his paper. In a market where a producer sells a commodity t o di¤erent generat ions of consumers who exhibit similar t ast es, past -sales typically cont ain (noisy) information about product ’s quality. In such envi-ronment s, we have shown that a monopolist has occasionally an incent ive t o

22For complet eness, we give in t he appendix t he condit ions under which t he seller would

-200 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200

Prof.

10 20 30 40 50

qn

Figure 3: equilibrium wit h past -sales advert ising

invest in advert ising act ivit ies t o report it s privat e sales-dat a. By doing so, t he supplier allows consumers to bet t er est imat e t he quality of t he good, and hence make wiser decisions. Oft en, but not always, t he seller bene…ciat es from more clever decisions on t he part of t he consumers. The equilibrium we derive present s t his feat ure. Indeed advert ising occurs for some past-sales ob-servat ions. When t his happens, t he equilibrium price is t he one which would be charged by t he seller if t here was symmet ric informat ion in t he market . When advert ising does not occur, eit her separat ing prices or pooling prices happen, depending on whet her or not consumers have ext ernal informat ion of t heir own.

informat ion of t heir own.

6

A ppendix

For complet eness, we analyze here under which condit ions a seller would bene…t from commit t ing t o keeping privat e it s past sales informat ion (if commit -ment possibilit ies are available). We do so for bot h t he informat ional scenario of Sect ion 3 and for t he case where buyers are bet t er informed.

In the Scenario where consumers do not receive any external informat ion, P r op osit i on 9 Suppose that the seller could commit either to reveal or to conceal his past-sales. Then, the monopolist would commit to deliver its sales-data if and only if 4c < E [E2[q j qN]]:

P r oof. First , not e t hat …rst period pro…ts are ident ical since in bot h sit -uat ions t he seller is complet ely uninformed. Consequently we can abst ract from t hem. By concealing, t he seller obt ains expect ed pro…ts E [¼c2] = a

2

4: By

revealing past -sales, expect ed bene…ts are E [¼r 2] = E

³

a+ E [qjqN ]

2

´2¸

¡ c =

a2

4 +

E [E2[qjq N ]]

4 ¡ c: By est ablishing a comparison between opt imal pro…ts in

t he two cases, t he t heorem follows. Q.E.D. R em ar k 2 Note that E [E2[q j qN]] > 0: I f E [qjqN] 6= 0 this is immediate.

Suppose now that E [qjqN] = 0: Since q and ²N are independent, we have

that E [q²N] = E [q]E [²N] = 0 Thus E [q2] = E [q(q + ²N)] = E [qqN] =

E [E [qjqN] qN] = 0 a contradiction.23

To gain some int uit ion about t he condition in Proposition 9, let us look at t he case where random variables are normally dist ribut ed. The condit ion reduces t o 4c < ¾4q

¾2

q+ ¾2²=N: Therefore, it t ends t o be satis…ed when t he number

of consumers is high, and t he noise of t he informat ive signals and advert ising cost is low.

In the informat ion Scenario where consumers receive signals of Sect ion 4,

P r op osit i on 10 Suppose that the seller could commit either to reveal or conceal his sales. Then, the seller would commit to advertise its past-sales if and only if parameters satisfy

4c < a2 µ

v(1 ¡ u) h

¶

+ ±1¾2qv(1 ¡ u):

P r oof. By concealing past sales informat ion t he seller obt ains expect ed bene…ts E [¼c

2] = E

£uh

h+ v (p c 2)

2¤

= uh(h+ v)4 h

a2

h2 + E [q

2 N]

i

: By revealing, t he monopolist get s expect ed pro…ts E [¼r

2] = E

£ (pr

2) 2¤

¡ c = Eh¡a+ hqN

2

¢2i

¡ c: By comparing, E [¼c

2] and E [¼r2] and using t he fact t hat E [qN2] = ±1¾2q

h ; t he

t heorem follows. Q.E.D.

R efer ences

[1] Bagwell, K . and M. Riordan: “ High and Declining Prices Signal Product Quality” , American Economic Review 81, pp. 224-239, 1991.

[2] Banerjee, A.: “ A Simple Model of Herd Behavior” , Quarterly Journal of Economics 107, pp. 797-817, 1992.

[3] Bikhchandani, S., D. Hirshleifer and I. Welch: “ A t heory of Fads, Fash-ion, Cust om, and Cult ural Change as Informat ional Cascades” , Journal of Political Economy 100, pp. 993-1026.

[4] Berger, M.: “ Technology Updat e” , Sales and Marketing Management 149, pp. 104-106, 1997.

[5] Caminal, R. and X. Vives: “ Why Market Shares Mat t er: an Informat ion Based Theory” , Rand Journal of Economics 27, pp. 221-239, 1996. [6] Gal-Or, E.: “ Informat ion Sharing in Oligopoly” , Econometrica, 53, pp.

329-343, 1985.

[7] Gal-Or, E.: “ Information Transmission- Cournot and Bert rand Equilib-ria” , Review of Economic Studies 53, pp. 85-92, 1986.

[9] Milgrom P. and J. Robert s: “ Price and Advert ising Signals of Product Quality” , Journal of Political Economy 94-4, pp. 796-821, 1986.

[10] Nelson, P.: “ Informat ion and Consumer Behaviour” , Journal of Polit-ical Economy, 78, pp. 311-329, 1970.

[11] Nelson, P.: “ Advert ising as Informat ion” , Journal of Political Economy, 81, pp. 729-754, 1974.

[12] St edman, C.: “ Warehouses send answers in E-mail” , Computerworld 32-13, pp. 53-54, 1998.

[13] Vives, X.: “ Duopoly Informat ion Equilibrium: Cournot and Bert rand” , Journal of Economic Theory, 34, pp. 71-94, 1984.