Rev Saúde Pública 2004;38(6) www.fsp.usp.br/rsp

Cow’s milk consumption and childhood

anemia in the city of São Paulo, southern

Brazil

Renata Bertazzi Levy-Costaa e Carlos Augusto M onteirob

aNúcleo de Pesquisas Epidemiológicas em Nutrição e Saúde. Universidade de São Paulo. São Paulo,

SP, Brasil. bDepartamento de Nutrição. Faculdade de Saúde Pública. Universidade de São Paulo. São Paulo, SP, Brasil

Correspondence to:

Renata Bertazzi Levy-Costa Instituto de Saúde

Rua Sto Antônio, 590 3º andar 01314-000 São Paulo, SP, Brasil E-mail: rlevy@usp.br

Atricle based on the Master’s dissertation “Cow’s milk consumption and anemia in childhood in the Municipality of São Paulo”, presented at the Faculdade de Saúde Pública of the University of São Paulo in 2002.

Received 25 August 2003. Revised 23 December 2003. Accepted 15 April 2004. Keywords

Cow Milk. Anemia. Iron, dietary. Infant nutrition. Child health (public health).

Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the influence of the consumption of cow’s milk on the risk of anemia during childhood in the city of São Paulo.

Methods

We have studied a probabilistic sample (n=584) of underfive children living in the city of São Paulo, southeastern Brazil, between 1995 and 1996. Anemia (hemoglobin <11g/dl) was diagnosed using capillary blood obtained by fingertip puncture. The cow’s milk content and the density of heme and nonheme iron in the child’s diet were obtained using 24-hour recall questionnaires. Multiple linear and logistic regression models were used to study the association between cow’s milk content in the diet and hemoglobin concentration or risk of anemia, and included statistical control for potential confounders (age, sex, birthweight, presence of intestinal parasites, family income, and mother’s schooling).

Results

The prevalence of anemia was 45.2% and the mean contribution of milk to the total caloric content of the children’s diets was 22.0%. The association between milk consumption and risk of anemia remained significant, even after considering the dilutive effect of milk consumption on the density of iron in the diet, thus indicating a possible inhibitor effect of milk on the absorption of the iron present in the other foods ingested by the child.

Conclusions

The relative participation of cow’s milk in the child’s diet showed a significant positive association with risk of anemia in children between ages six and 60 months, regardless of the density of iron in the diet.

INTRODUCTION

Anemia, an insufficient concentration of hemo-globin in blood (<11g/dl), is one of the most frequent nutritional disorders worldwide.21 Children under age five years are second only to pregnant women in terms of anemia prevalence.14,21 According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, roughly one-half of the underfives in developing countries – China ex-cluded – suffer from anemia. It is estimated that

anemia affects 30% of preschool children in Latin America.14 A probabilistic household survey carried out in the city of São Paulo found a 46.9% preva-lence anemia in underfives.9

Rev Saúde Pública 2004;38(6) www.fsp.usp.br/rsp Consumo de leite de vaca e anemia

Levy-Costa RB & Monteiro CA

*Philippi ST, Szarfarc SC, Latterza AR. Virtual Nutri (software). Versão 1.0 for windows. São Paulo: Departamento de Nutrição da Faculdade de Saúde Pública da Universidade de São Paulo; 1996.

are widely acknowledged as the main cause for the high prevalence if this disease in childhood.13,14,20,21,23

Diets relying exceedingly on the consumption of cow’s milk may be one of the causes of the high risk of anemia observed in the first years of life, since cow’s milk is poor in iron (about 2.6 mg Fe per 1,000 kcal). Recommended daily iron consumption be-tween ages six and 60 months is 10 mg, which corre-sponds to diets with iron densities of 11.7 mg, 7.7 mg, and 5.6 mg for children aged six-11 months, 12-35 months, and 36-60 months, respectively.

In addition to being poor in iron, cow’s milk does not contain heme iron, the form which is best ab-sorbed by the body.3,13 According to experimental data, cow’s milk also has the potential to inhibit the absorption of both heme and nonheme iron present in other foods consumed by the child.4,5,17

Notwithstanding, the association between the con-sumption of cow’s milk and hemoglobin concentra-tion has been little explored in epidemiological stud-ies. A recent pioneer study using a cohort of Euro-pean children showed that the hemoglobin concen-tration reached by children at age 12 months was inversely related to the number of months during which the child consumed cow’s milk.7

The present study was designed to study the influ-ence of cow’s milk consumption on hemoglobin con-centrations and on the risk of anemia in underfives.

M ETH O D S

The data used were generated by a survey con-ducted by the Núcleo de Pesquisas Epidemiológicas em Nutrição e Saúde da Universidade de São Paulo

(Center for Epidemiological Research in Nutrition and Health, University of São Paulo – NUPENS/ USP), between September 1995 and September 1996, based on a probabilistic sample composed of 4,560 households in the city of São Paulo. This sur-vey is known as the Saúde e Nutrição das Crianças de São Paulo (Health and Nutrition in São Paulo Children) survey. 8 Sampling was stratified and in multiple stages, involving the random selection of census sectors, household clusters, and individual households. Visits to the 4,560 selected households identified 1,390 children under age five years. Of these, 110 were not included in the survey – either because they were not found after three visits or because parents did not authorize participation – resulting in a total of 1,280 children aged between

zero and 59 months. Dietary recalls investigating food consumption in the last 24 hours were admin-istered to all children aged between six and 23 months, and to one of every three children aged be-tween 24 and 59 months, totalling 598 children whose food consumption information are described in the present study. Hemoglobin dosage could not be performed on 14 children, and hence the analy-ses of the relationship between food consumption and hemoglobin concentration refer to 584 children.

Information on food consumption was provided by the parent or caretaker by a 24-hour dietary re-call.22 Blood samples were obtained by fingertip puncture, and hemoglobin was measured at the child’s home using a portable hemoglobinometer (HemoCue®)19. The information on salaries and other sources of income and on maternal schooling used in the present study were obtained by questionnaires. Information on the occurrence of intestinal para-sitic diseases was obtained from stool samples col-lected at the child’s home and analysed by sedimen-tation. The child’s birthweight was obtained from maternity files, or, alternatively, from information provided by the child’s mother.

The level of cow’s milk consumption of each child was expressed as the percentage of the child’s daily calorie intake which was due to the consumption of any type of milk (whole-milk or modified formula and natural, pasteurized, or long-life fluid milk). The transformation of the foods reported in the 24-hour recall into energy and nutrients was done using Vir-tual Nutri®software.*

As a description of the study population, we present the distribution of hemoglobin concentra-tion, anemia prevalence, and food consumption in-dicators according to sociodemographic variables. The association with sex was evaluated by Student’s

t and chi-squared tests. Associations with age (6-11, 12-23, 24-35, 36-47, and 48-60 months), per capita family income (0.0 0.5, 0.5 1.0, 1.0 2.0, ≥2.0 minimum wages) and mother’s schooling ( 0-3, 4-7, 8-10, ≥11 years) was evaluated by simple linear re-gression and chi-squared and linear trend tests.

The influence exerted by the consumption of cow’s milk on the iron density in the diet was studied by comparing the observed value with the expected con-centration if milk were excluded and substituted by the remaining food items present in the child’s diet.

!

Rev Saúde Pública 2004;38(6) www.fsp.usp.br/rsp

Consumo de leite de vaca e anemia Levy-Costa RB & Monteiro CA

on hemoglobin concentration was determined based on a multiple regression model in which hemoglobin concentration was the dependent variable and the relative consumption of cow’s milk the explanatory variable. Multiple logistic regression was used to evaluate influence over the risk of anemia, with the child’s anemia status (absent or present) as the out-come and the terciles of relative milk consumption, expressed as the percentage contribution of milk to the total calorie content of the diet, as the explana-tory variable. Child’s birthweight, age, and sex, pres-ence of intestinal parasitic disease, per capita fam-ily income, and mother’s schooling were considered as potential confounders in the association between milk consumption and hemoglobin concentration or anemia. Child’s age and sex, per capita family income, and mother’s schooling were significantly associated with hemoglobin concentration and/or risk of anemia in simple regression models (p<0.05) and were included in the multiple regression analy-sis. When measuring the specific effect of milk con-sumption on hemoglobin concentration – which would be independent of the ‘diluting effect’ of milk on the density of iron in the diet – heme- and nonheme-iron densities were added to the regres-sion models.

In all analyses, weighting factors were employed in order to allow for the extrapolation of the results ob-tained in the present study to the entire child popula-tion of the city of São Paulo between ages six and 59 months. The α=5% significance level was adopted. All analyses presented in the present study were per-formed using STATA 6.0 software.

RESU LTS

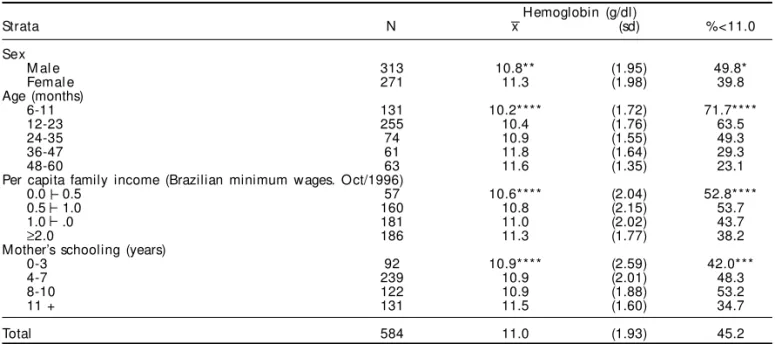

Table 1 presents the distribution of hemoglobin concentration and anemia in the child population of São Paulo according to sociodemographic variables. Anemia was present in 45.2% of children, and was significantly more prevalent among boys than among girls. Anemia prevalence varies strongly with age, peaking at some point between ages six and 12 months and declining slightly in the second year of life and more sharply in the third year. Increases in both per capita family income and mother’s school-ing were significantly associated with reductions in the prevalence of anemia. Mean hemoglobin con-centration is significantly higher in girls than in boys, and tends to increase both with age and with family income and mother’s schooling.

The sociodemographic distribution of the charac-teristics of the child’s diet relevant to the present study is presented in Table 2. The percentage participation of milk in the diet decreases significantly with age, there being no uniform pattern of variation along with family income and mother’s schooling. The indica-tors of iron density in the child’s diet increased sig-nificantly with age, per capita family income, and mother’s schooling, with the exception of nonheme iron, which did not differ significantly between the groups. There were no significant differences between sexes with respect to milk consumption or iron den-sity indicators.

The mean iron density in the milk consumed by the studied children (2.7 mg/1000 kcal) was lower than

Table 1 – Distribution of hemoglobin concentration according to sex, age, and socioeconomic indicators.

Hemoglobin (g/dl)

Strata N x (sd) %<11.0

Sex

M al e 313 10.8** (1.95) 49.8*

Femal e 271 11.3 (1.98) 39.8

Age (months)

6-11 131 10.2**** (1.72) 71.7****

12-23 255 10.4 (1.76) 63.5

24-35 74 10.9 (1.55) 49.3

36-47 61 11.8 (1.64) 29.3

48-60 63 11.6 (1.35) 23.1

Per capita family income (Brazilian minimum wages. Oct/1996)

0.0 0.5 57 10.6**** (2.04) 52.8****

0.5 1.0 160 10.8 (2.15) 53.7

1.0 .0 181 11.0 (2.02) 43.7

≥2.0 186 11.3 (1.77) 38.2

Mother’s schooling (years)

0-3 92 10.9**** (2.59) 42.0***

4-7 239 10.9 (2.01) 48.3

8-10 122 10.9 (1.88) 53.2

11 + 131 11.5 (1.60) 34.7

Total 584 11.0 (1.93) 45.2

N: Number of observations; x: mean; sd: standard deviation *p<0.05

**p<0.001

" Rev Saúde Pública 2004;38(6) www.fsp.usp.br/rsp Consumo de leite de vaca e anemia

Levy-Costa RB & Monteiro CA

the mean iron density in the children’s diets (5.40 mg/ 1000 kcal). The ‘diluting effect’ of milk on the iron density of the diet was estimated at 22%. This value was obtained by comparing the iron density observed in the diet with the estimated density in case milk were suppressed from the child’s diet (5.40 mg/1000 kcal in the first scenario vs. 6.17 mg/1000 kcal in the second).

Table 3 presents the results of linear regression be-tween cow’s milk consumption and hemoglobin con-centration. The percentage of the total daily calories ascribed to milk was significantly correlated with the children’s hemoglobin concentration . However, this correlation was not independent of the density of heme and nonheme iron in the diet. Note that the standardized regression coefficient between milk consumption and hemoglobin concentration was only

slightly altered after controlling for the indicators of iron density in the diet. The result of controlled Model C (0.0822) is quite similar to that of non-controlled Model B (0.1048). This indicates that the negative effect of milk consumption on hemoglobin concen-tration via an inhibition of iron absorption should not be disregarded.

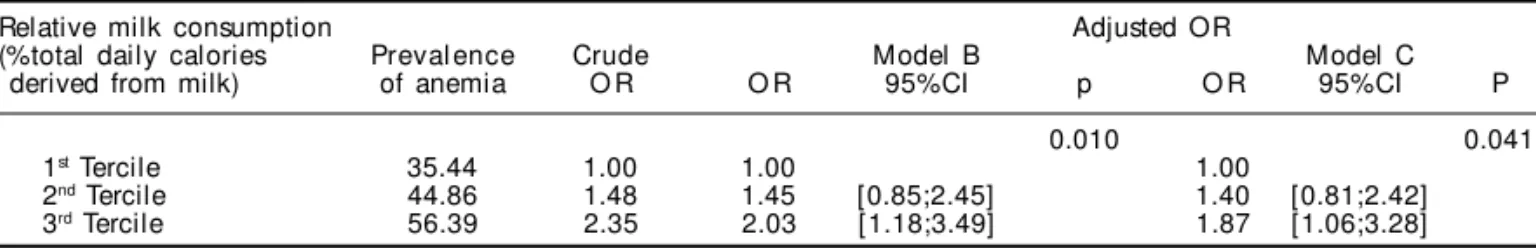

Table 4 presents the results of logistic regression models of the association between terciles of relative milk consumption and risk of anemia. Positive asso-ciations between these variables were obtained both in Model B (adjusted only for sex, age, and socioeco-nomic variables), and in Model C (adjusted also for the iron density of the diet). Model B shows that the odds ratio for anemia increased by about 50% and 100% when children with intermediate (2nd tercile)

Table 3 – Standardized regression coefficients for the association between relative milk consumption and (% of total calories

derived from milk) and hemoglobin concentration in three linear regression models.

Model Adjustment variables Regression coefficient (ß) P

A N one -0.2435 0.000

B Sex, age, mother’s schooling, and log per capita family income -0.1048 0.031 C Variables in model B plus density of heme and nonheme iron in the diet -0.0822 0.081

Table 2 – Percentage of calories derived from milk and iron density in the diet according to sex, age, and socioeconomic

indicators.

Iron density (mg/1,000 kcal)

% calories form milk Total H eme N onheme

Strata x (sd) x (sd) x (sd) x (sd)

Sex

Male (N=319) 22.0 (18.22) 5.5 (2.50) 1.1 (1.61) 4.4 (2.32) Female (N=279) 21.9 (16.2) 5.3 (2.51) 1.1 (1.50) 4.2 (2.17) Age (months)

6-11 (N=135) 31.7 (19.64)** 5.0 (2.67)* 0.6 (0.93)** 4.4 (2.44) 12-23 (N=259) 26.9 (17.22) 5.4 (2.25) 1.0 (1.13) 4.4 (2.25) 24-35 (N=78) 21.8 (15.10) 5.4 (2.03) 1.2 (1.41) 4.2 (1.59) 36-47 (N=63) 20.6 (11.51) 5.6 (2.22) 1.2 (1.19) 4.4 (2.14) 48-60 (N=63) 13.1 (10.64) 5.5 (1.82) 1.4 (1.27) 4.1 (1.59) Per capita family income (Brazilian minimum wages. Oct/1996)

0.0 0.5 (N=58) 22.1 (17.21) 5.4 (2.97)* 0.7 (1.22)* 4.7 (3.05)* 0.5 1.0 (N=160) 22.5 (18.97) 5.5 (2.40) 1.2 (1.77) 4.3 (2.15) 1.0 2.0 (N=189) 21.8 (17.60) 5.4 (2.48) 1.2 (1.79) 4.2 (1.79)

≥2.0 (N=191) 21.7 (16.03) 5.4 (2.49) 1.1 (1.11) 4.3 (2.49) Mother’s schooling (years)

0-3 (N=94) 21.0 (19.00) 5.3 (2.62)** 1.2 (1.84)* 4.1 (1.94)** 4-7 (N=245) 21.7 (18.62) 5.3 (2.50) 1.0 (1.57) 4.3 (2.35) 8-10 (N=126) 24.8 (14.93) 5.4 (2.36) 1.2 (1.68) 4.2 (2.13) 11 or + (N=133) 20.5 (15.80) 5.5 (2.42) 1.1 (1.27) 4.4 (2.31)

Total (N=598) 22.0 (17.36) 5.4 (2.45) 1.1 (1.47) 4.3 (2.20) N: number of observations; x: mean; sd: standard deviation

*p for linear trend <0.05 **p for liner trend <0.001

Table 4 – Prevalence of anemia (hemoglobin <11 g/dl) according to terciles of relative milk consumption and corresponding

crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR).

Relative milk consumption Adjusted OR

(%total daily calories Prevalence Crude Model B Model C derived from milk) of anemia O R O R 95%CI p O R 95%CI P

0.010 0.041

1st Tercile 35.44 1.00 1.00 1.00

2nd Tercile 44.86 1.48 1.45 [0.85;2.45] 1.40 [0.81;2.42]

3rd Tercile 56.39 2.35 2.03 [1.18;3.49] 1.87 [1.06;3.28]

CI: confidence interval

#

Rev Saúde Pública 2004;38(6) www.fsp.usp.br/rsp

Consumo de leite de vaca e anemia Levy-Costa RB & Monteiro CA

or high (3rd tercile) milk consumption, respectively, are compared with children with low milk consump-tion (1st tercile). Controlling for variations in the iron density of the diet has little effect on the excess risk of anemia among children with higher milk consump-tion, which reinforces the relevance of the mecha-nism of inhibition of iron absorption associated with the consumption of cow’s milk.

D ISCU SSIO N

In the present study we have shown that increases in the relative participation of cow’s milk in the child’s diet are associated significantly and independently with increased risk of anemia. This was based on a representative sample of the children living in the city of São Paulo aged between six and 59 months, and on the collection and analysis of information on the consumption of cow’s milk, hemoglobin concen-tration, and potential confounders. The association between milk consumption and risk of anemia re-mained significant even after considering the dilu-tive effect of milk consumption on the iron density of the diet, thus indicating a possible inhibitive ef-fect of milk on the absorption of the iron present in other foods in the child’s diet.

Although we acknowledged that the instruments used for measuring food consumption (recall question-naire) and hemoglobin dosage (portable hemoglobi-nometer) may leave room for measurement errors,10,22 such errors are probably not associated, therefore lead-ing to an underestimation of the magnitude of the ac-tual association between milk consumption and anemia. It is also important to note that the evaluation of the child’s food consumption took place before the measurement of hemoglobin concentration. Thus both the interviewer and the mother were unaware of child’s anemia status at the time the questionnaire was admin-istered, reducing the risk of systematic errors.

The probabilistic character and the successful im-plementation of the procedures employed for select-ing the original sample of the Saúde e Nutrição das Crianças de São Paulosurveyindicate that the re-sults of the present study may be extended to the entire child population of the city of São Paulo.

Likewise, the magnitude and distribution of anemia, and the child feeding patterns in the city of São Paulo are similar to those found in other Brazilian urban centers, which could favor a greater generalization of the results obtained in the present study. A probabilis-tic household survey conducted in the city of Salva-dor, northeastern Brazil, in 1996, found a 46.4% preva-lence of anemia among underfives, a level similar to

the 45.2% found in São Paulo.6,9 Still in the city of Salvador, where food consumption in the last 24 hours was also studied, the iron density in the diet was 5.6 mg/1,000 kcal in the six to 11 months age group and 5.8 mg/1,000 kcal in the 12 to 23 months age group. Again, these values were similar to those found in São Paulo, 5.0 mg/1,000 kcal and 5.4/1,000 kcal in these two age groups, respectively. An important participa-tion of milk in the diet was also observed in Salvador, where the participation of milk in the total calorie value was 36.7% in the six to 11 months age group and 31.9% in the 12 to 23 months group. The correspond-ing values in São Paulo were 31.7% and 26.9% in these two age groups, respectively.11

Three other probabilistic surveys conducted in the 1990’s in urban centers in the Northeast and South Regions of Brazil showed prevalences of anemia in childhood very close to the 45.2% found in the present study: 39.6% in the metropolitan area of Recife, North-east Region, in 1997,16 47.8% in Porto Alegre, South Region, in 1997 (children under age three years),18 and 54.0% in Criciúma, also in the South Region, in 1996 (children under age three years).12 The age distri-bution of the prevalence of anemia – peaking in the six to 24 month period and falling in older age groups – observed in the São Paulo study was also found in the above mentioned studies.

Theoretically, the negative influence of milk con-sumption on the hemoglobin concentration may be due to two mechanisms: dilution and inhibition. The dilution mechanism is related to the low concentra-tion of iron present in cow’s milk, whereas the inhibi-tion mechanism is related to the presence, in cow’s milk, of substances such as calcium, casein, and se-rum proteins, which are proven inhibitors of iron ab-sorption by the human organism.4,5,17 Our results con-firm the importance of both mechanisms.

Another potential mechanism for the negative influ-ence of cow’s milk on hemoglobin concentration is the appearance of micro-hemorrhages in the intestinal mucosa, which would be induced by the consumption of natural or pasteurized milk, but not by diluted for-mula. Such micro-hemorrhages have been reported in the literature, particularly among infants.1,15 However, the inclusion, in our regression models, of the type of milk ingested by the child did not indicate an associa-tion between this variable and hemoglobin concen-tration, neither in the whole underfive sample, nor among infants only (data not shown).

$ Rev Saúde Pública 2004;38(6) www.fsp.usp.br/rsp Consumo de leite de vaca e anemia

Levy-Costa RB & Monteiro CA

in national or international publications on the sub-ject.2,11,20,21 A recent WHO publication, however, rec-ommends that the ingestion of milk not coincide with the child’s major meals.23

As mentioned above, due to the low precision of the instruments used for measuring food consump-tion and hemoglobin concentraconsump-tion, the impact of milk consumption on the risk of childhood anemia is

REFEREN CES

1. Akré J, editor. Alimentação infantil: bases fisiológicas. Genebra: Organização Mundial da Saúde; 1994.

2. DeMaeyer EM. Preventing and controlling iron deficiency anaemia through primary health care: a guide for health administrators and programme managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1989.

3. Fairweather-Tait SJ. Iron deficiency in infancy; easy to prevent – or is it? Eur J Clin Nutr 1992;46:S9-S14.

4. Hallberg L, Brune M, Erlandsson M, Sandberg AS, Rossander-Hultén L. Calcium: effect of different amounts on nonheme and heme-iron absorption in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 1991;53:112-9.

5. Hallberg L, Rossander-Hulthén L, Brune M, Gleerup A. Inhibition of haem-iron absorption in man by calcium. Br J Nutrit 1992;69:533-40.

6. Instituto Nacional de Alimentação e Nutrição [INAN]. Condições de vida, saúde e nutrição da população materno-infantil da cidade de Salvador. Salvador; 1999. (INAN/MS-UFBA Relatório final).

7. Male C, Persson LÅ, Freeman V, Guerra A, Vann´t Hof MA, Haschke F. Prevalence of iron deficiency in 12-mo-old infants from 11 European areas and influence of dietary factors on iron status (Euro-Growth Study). Acta Pædiatr 2001;90:492-8.

8. Monteiro CA, Conde LW. Tendência secular do crescimento pós-natal na cidade de São Paulo (1974-1996). Rev Saúde Pública 2000;34(6 Supl):41-51.

9. Monteiro CA, Szarfarc SC, Mondini L. Tendência secular da anemia. Rev Saúde Pública 2000;34(6 Supl):62-72.

10. Morris SS, Ruel MT, Cohen RJ, Dewey KG, La Brière B, Hassan MN. Precision, accuracy and reliability of hemoglobin assessment with use of capillary blood. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69:1243-8.

11. Ministério da Saúde Brasil. Secretaria de Políticas Públicas. Projeto para o controle da anemia ferropriva em crianças menores de 2 anos nos Municípios do Projeto de Redução da Mortalidade na Infância. Brasília (DF); 1998.

12. Neuman NA, Tanaka OY, Szarfarc SC, Guimarães PRV, Victora CG. Prevalência e fatores de risco para anemia no Sul do Brasil. Rev Saúde Pública 2000;34:56-63.

13. Olivares M, Walter T, Hertrampf E, Pizarro F. Aneamia and iron deficiency disease in children. Br Med Bull 1999;55:534-43.

14. [OMNI] Opportunities for Micronutrient Interventions. Proceedings: interventions for child survival. London; May 1995. Disponível em: http://www.jsi.com/intl/ omni/ironmain.htm [set 2001]

15. Oski FA. Is bovine milk a health hazard? Pediatrics 1985;75(Suppl):182-6.

16. Osório MM, Lira PIC, Batista-Filho M, Ashworth A. Prevalence of anemia in children 6-59 months old in the state of Pernambuco, Brazil. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2001;10:101-7.

17. Rossander-Hulthén L, Hallberg L. Dietary factores influencing iron absorption – an overview. Iron Nutr Health Dis 1996;10:105-15.

18. Silva LSM, Giugliani ERJ, Rangel D, Aerts GC. Prevalência e determinantes de anemia em crianças de Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. Rev Saúde Pública 2001;35:66-73.

19. Van Schenck H, Falkensson M, Lundberg B. Evaluation of “ HemoCue” , a new device for determining hemoglobin. Clin Chem 1986;32:526-9.

20. United Nations.Administrative Committee on Coordination.Subcommittee on Nutrtion [UN/ACC/ SCN]. Controlling iron deficiency. State of the art series, nutrition policy discussion. Geneva; 1991. (UN/ACC/SCN – Report )

21. United Nations Children’s Fund [Unicef]. Preventing iron deficiency in women and children: background and consensus on key technical issues and resources for advocacy, planning and implementing national programmes. New York; 1998. (Unicef/UNU/WHO/ MI – Technical Workshop).

22. Willett W. Nature of variations in diet. In: Willett W, organizator. Nutritional epidemiology. 2nd ed. New

York: Oxford University Press; 1998. p. 33-49.

23. World Health Organization [WHO]. Iron deficiency anaemia. Assessment, prevention, and control. A guide for programm managers. Geneva; 2001. (Unicef/UNU/W HO).