Photographic Books

Emotional City Mapping through The Innocence

of Objects

MóNICA PACHECo

Cities’ representation has become increasingly limited, disregarding thousands of years of complex cartographies–between the sentimental and the documental. This chapter attempts to explore a particular photography book: a catalogue which addresses the representation of place in a rather unconventional way. The Inno-cence of Objects is part of a triangle, together with orhan Pamuk’s novel and the Museum of Innocence in Istanbul. The novel-catalogue is not a sub-product of the museum; on the contrary, it is at its origin. While the Museum of Innocence is the architecture of a sequence of scenes that build up space from the reconstruction of careful compositional structures that generate new relationships, The Innocence of Objects displays them as still-lifes, where story and history merge. Through photog-raphy, the displayed compositions—or artificial landscapes—build up a panoramic cityscape, an urban identity beyond its physical form and specific time, that encour-ages a deeper understanding of the multiple and stratified meanings of the city.

Cities have now long functioned as artistic protagonists. Their representation in architecture, the visual arts, cinema and photography, their differences, simi-larities and interactions have been widely discussed. Nevertheless, while archi-tecture is understood as an art form despite its technical and scientific aspects; and cinema conquered the title of 7th art and is assumed by some to be the total fusion of arts (and therefore art par excellence), photography is still a controver-sial field given the multiplicity of ways and purposes in which it has been used, from commercials to journalistic reports, together with the large number of people using photography in their daily lives.

However, architecture representation, as well as in cinema and photography, has often been misunderstood as an artifact aiming to be as accurate as possible in its correspondence with reality. The problem is, of course, the understanding of reality as coincident with vision, on the one hand, and on the other the idea that there is a certain degree of ‘scientificity’ in these representations, in the case of architecture due to Gaspard Monge’s orthogonal projections; and in cinema and photography, given the fact that both use an intermediary technical device (the camera). And within the artistic community, despite the fact that painters have been using technical apparatus since the Renascence, art is still seen as independent from technology.

It seems widely asserted that place plays an important role in the development of an architectural process and the approaches to it are manifold. Nevertheless, they remain, in most cases, as theoretical statements, rather than anchored in a deep knowledge. The specific conditions and multiple dimensions of place are rarely grasped, suggesting that the number of techniques that architects use to spatially represent it typically remain limited, not capturing its spatial identity and multi-sensorial aspects. Increasingly disregarding thousands of years of com-plex cartographies−between the sentimental and the documental–they remain a heritage of the Enlightenment will for turning scientific all fields of knowledge, in particular geography. Recalling Borges’s fable of those cartographers that pro-duced a Map of the Empire whose size coincided with that of the Empire itself, one can question how objectivity came across with the slow impoverishment of representation and its meaning. Earlier maps and cartographies were not meant to fix, but rather to take the user into a journey, therefore expressing a strong relation with narrative and aiming to synthetize time and space in one image

(Calvino, 2002: 54). They had an implicit order to express reality, paradoxi-cally having to shift away from it to make it more real, or to express ‘another real’. Although it seems contradictory in its terms, the eloquence becomes evi-dent of those maps such as Tabula Pentingeriana, an illustrated road system of the Roman Empire that, though covering Europe and partially Africa and Asia, represented it in a linear way, therefore achieving the intention of representing a journey. The map is drawn according to what it aims at representing, and con-sequently some elements are deprived of their (relative) importance through the distortion of scale and proportions of certain distances, positions or even con-figurations. The specific format chosen enabled the identification of the world with that of the Roman Empire, whereas in Fra Mauro’s map of 1459 Europe is significantly smaller when compared to the rest of the world, accounting for a specific moment of history. If we are to compare these two examples, it becomes obvious that cartography was not only about physical space, but rather about turning visible the invisible presences of power and so forth. And that implied inversions, distortions or other manipulations that would change the relation between the parts and the whole, enabling the emergence of a narrative. When we map, the goal is not to present; it is to explore and discover something new that our eyes cannot see yet. But to translate what we know or what we feel about a place via visual representation instead of what we see, despite the lessons from medieval painting or cubism, is still difficult to accomplish in architecture, and the attempts to represent what is known usually come in the format of bi-dimensional maps where different colors point out different uses, ages, states of conservation, etc., not adding anything to what is already known. The reason relies on an apparent incapacity to translate other fields’ information into our own language and for our own purposes. That ‘spatialization’ requires intentionality behind representation, which in turn implies the selection, organization and asso-ciation of material in a dialectic manner, enabling different discoveries, previously unknown to us. It is a way of learning. ‘The articulation becomes the knowing; the knowing comes out of the process, and it refuels a further effort at articulation. A sense of ecstatic fruitfulness, of rich discoveries, of voyaging, comes to us in the exhilarating moments of being-in-our-work-in-process’ (Turchi: 2004, 17).

orhan Pamuk’s Trilogy

The cultural project developed by the Turkish Nobel prizewinner, Orhan Pamuk, appears to come across many of these critical points, deserving therefore careful examination. It is at the intersection of ‘writing about space’ and ‘writing spa-tially’, in a visual manner, not in a dichotomous sense but rather complementarily, attempting to describe spatial experiences on the one hand, as well as to spatialize multi-sensorial experiences on the other, allowing an argument about representa-tion, and mapping in particular, as the very first act of transforming reality. This chapter attempts to explore a particular photography book, a catalogue. The Innocence of Objects is part of a trilogy, together with a novel, The Museum of Innocence, and a physical Museum with the same name in Istanbul, conceived simultaneously–and all fictional artefacts. Pamuk thought he would be able to put together a novel in the form of a catalogue with long and richly detailed notes (Pamuk, 2012: 17), an idea that is symptomatic of the urge to represent something visually and the dilemma of representation. Therefore, the museum catalogue is a heritage of the first idea behind the project. Together they question the role of representation in photography, as well as the representation’s formats of architec-ture. They are paradigmatic of research on the limits of representation, both as a generative process that reflects a particular experience of the world, and as spatial constructions of complex intertwining spheres, derived from the relation between reality and fiction, time and space, and from the way in which memory is recalled. The act of representing allows several reflections on the urban that unfold hidden questions, highlight qualities and identities, and therefore should be considered a vantage point from which to consider the nature of place. The city’s strong stand-ing in arts in general, and the literary tradition in particular, is not new. However, Pamuk takes a step further in his reliance on the city as a technical device applied to the construction of novels, and extends the convention according to which a city may indeed be responsible for producing fiction. The Museum of Innocence, having emerged from the very fabric of the city, produces the material space of the actual Museum, a geographically-specific and physical object. In fact, he is the first to bring together a novel, a museum and a museum-catalogue in a single story. The project started to be thought of in the mid-1980s and took over 20 years to accomplish, with the final opening of the Museum in 2012. In the beginning

Pamuk intended to conceive a novel in the format of a kind of encyclopaedia of concepts, which developed further into a form of novel-catalogue by the time Pamuk decided he wanted to focus on objects and tell a story through them, exploring their power to trigger memories. By the mid-1990s he started to collect from antique shops in Istanbul the objects that the protagonist fam-ily would use, envisioning exhibiting the ‘real’ objects of a fictional story in a museum and writing a novel based on them (Pamuk, 2012: 15). However, the writing started only in 2002 (fig. 1).

The Museum of Innocence

The story takes place in recent republican Istanbul, and is about a bourgeois scion, Kemal, and his passionate obsession with a poor distant relative, Füsun, a dramatic account of the obstacles that people from different social backgrounds had to face at the time if they wanted fully to live their love. It could be a Shakespearean drama, but instead it concentrates on the complexity of the human soul, and the ways in which it finds its own way to survive. The impossible relation with Füsun led Kemal to collect (sometimes steal), over years, thousands of daily life objects that

Fig. 1. The Museum of Innocence in Istanbul, view of the 2nd floor

where each chapter of the book is displayed in a box. Catalogue 7-8. Photographer: Refik Anadol.

were touched by her, that belonged to her or simply reminded him of his beloved. Those are simultaneously a chronicle of his love, a symbolic map of all places where they had been together, but also a montage of real objects of a fictional story, in different compasses of story and history. The writer becomes a cartographer. At the end of his life, and long after Füsun’s death, Kemal’s obsessive behavior took him on a journey to conceive a museum to display the objects, and portray what he recalled as happiness. As part of the collection, the museum would be in the Füsun family’s house, one of the artefacts that mapped the story, and that he managed to buy in the novel―the actual (non-fictional) museum was bought by Pamuk in 1999 in Çukurcuma, a neighborhood of the so-called European side of Istanbul. For 15 years, Kemal travelled to visit small backstreet museums and find the right concept for his own, as Pamuk himself did between 1996 and 2001. The result was twofold. On the one hand it informed the way in which the Museum of Innocence could be arranged, on the other it resulted in an underlying manifesto about muse-ums that later in the museum catalogue became more explicit. The museum rea-soning relies on the idea that museums should be small, tell people’s stories through real and ordinary objects, used and known by everybody, as they are much more revealing of the history of mankind than the objects usually displayed in museums. Paradoxically dealing with the real objects of a fictional story and with imaginary objects from the real, Pamuk was looking at objects with the rigor of a collector, trying to find the many stories behind them. The act of collecting, as Italo Cal-vino put it, is coincidental with the need to transform the flow of one’s own exis-tence into a series of objects saved from dispersal, or into a series of written lines abstracted and crystalized from the continuous flux of thought (Calvino, 2013: 31). In Collezione di sabbia (1984) he describes an exhibition in Paris of disparate collections, focusing on what he considered more disturbing: a collection of sand.

‘[her aim was] to remove from herself the distorting, aggressive sensations, the confused wind of being, and to have at last for herself the sandy substance of all things, to touch the flinty structure of existence. That is why she does not take her eyes off those sands, her gaze penetrates one of the phials, she bur-rows into it, identifies with it, extracts the myriads of pieces of information that are packed into a little pile of sand. Each bit of grey, once it has been deconstructed into its light and dark, shiny and opaque, spherical, polyhedral

and flat granules, is no longer seen as a grey or only at that point begins to let you understand the meaning of grey’ (Calvino, 2013: 35-36).

The museum reflects a particular experience of the world derived from spatial con-structions where reality and fiction, time and space, become complex intertwining spheres, allowing multiple and parallel narratives. Paradoxically dealing with the real objects of a fictional story and with imaginary real objects, the writing and the objects are intimately tied. Like all house museums, the Museum of Innocence also challenges scale, being simultaneously the gathering of the collection and a piece of the collection itself. But it takes this challenge much further. Placed in Istanbul, it houses Istanbul history as well as the couple’s story. The museum is part of the collection itself and yet, unlike most house-museums that try to leave reality as it was at a certain moment, as if suspended in time, this museum, filled with everyday objects, houses a narrative by reassembling its objects in a new order.

This highlights the mental procedure of classification that collecting implies. Objects, when detached from their original context, ordered and related with those of the same species, allow the discovery of the meaning of their subtle differences.

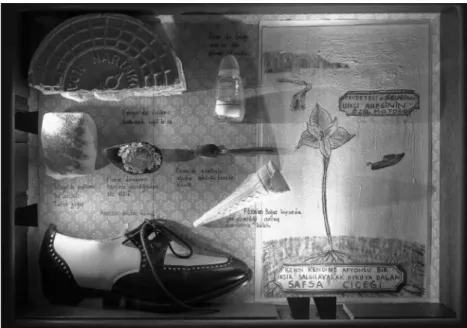

Fig. 2. Display boxes as presented in the catalogue. Catalogue 12-13. Photographer: Refik Anadol.

Likewise, Pamuk finds in the everyday, in the ordinary, in the quotidian experience a way of describing a city beyond the boundaries of public space and experienc-ing an inner world, more private, not available to the eyes and other senses. And that is perhaps one of the first architectural lessons to take from it: existing places cannot be reduced to their public sphere, the only one we can usually see. Place is simultaneously private and public, spatial and non-spatial, tangible and intangible. Memories can sometimes tell more about it than any other features, as they can affect the way people interact with space, changing it dramatically (fig. 2).

The Photographic Book-Catalogue vs

Exhibition Catalogues

Surprisingly, the novel-catalogue is not a sub-product of the museum. In fact it is at the very origin of the whole project. Therefore, being a ‘catalogue’ does not relate to the traditional idea of it, that is, a means of reproducing a subject, but rather a subject per se, which explores the artistic and narrative capacity of photography as a medium to represent reality beyond vision, paradoxically through a visual device. On the other hand, it is in the photographic book-catalogue that story and history merge and become the scenario of another protagonist, Istanbul. Through photog-raphy, the displayed compositions—or artificial landscapes—build up a panoramic cityscape which is not coincidenta; with the reality of vision but, on the contrary, convey an urban identity beyond its physical form and specific time, that encourages a deeper understanding of the multiple and stratified meanings of the city. Through photography, the city becomes four-dimensional; Kemal and Füsun are just two among many other characters and hidden stories behind the daily-life objects, the pictures, the journal fragments, the brands and their logos, the paintings and the postcards that are frozen in photographs, simultaneously representing Pamuk’s sen-timental Istanbul and constructing our own symbolic imaginary of the city.

‘Stories could also take this noble name: every day, they transverse and organize places; they select and link them together; they make sentences and itineraries out of them. They are spatial trajectories. […] narrative structures have the status of spatial syntaxes. Every story is a travel story–a spatial practice’ (de Certeau, 1984).

Peter Eisenman, when referring to timeless buildings, compares them to literature classics, saying that what makes one return to them is not the story, but the way the story is written or narrated. The narrative consists in the construction of an argument through the articulation of sequences (both in space and time) which presupposes an organization, a thread, a plug or switch. That takes us to questions of form: in architecture, as well as in literature, what changes is not the theme, but the way in which the spatial configurations are arranged taking out most of their potential. And though the History of Architecture has plenty of successful examples of the kind, it is paradoxically when it comes to represent an existing place that representation becomes critical.

By analogy, the sequence of photographs in The Innocence of Objects tells of a novel behind story and history, its process, and how process, story and history intertwine. Furthermore, each picture, and in particular the pictures of the chapter-boxes, nar-rates a story per se. But, as Peter Greenaway would argue about his own oeuvre in The Alphabet and the Eye, they make it very obvious that they depict artificial compositions and not reality. They do so in many ways, not only by photograph-ing compositions of pictures, but also by referrphotograph-ing to an almost surrealistic imagery, challenging scale, context and the original purpose of objects. And that is what distinguishes this particular photographic book from an exhibition catalogue.

The Image of Place

The urban image of a city relies on both real and imaginary constructions and reconstructions, embedded in diverse cultural manifestations such as literature, cinema, photography and the visual arts.

There are places and spaces that dwell somewhere between reality and imagination as extensions of filmic fictions, particularly in cities like New York and Venice. The classic Casablanca, the 1942 movie, for instance was, and still is, responsible for most of the western world’s image of the city despite the fact that no scenes had been shot there but on a Hollywood back lot, and the Rick’s Café Américain set based on the historic El Minzah Hotel in Tangier, suggesting or evoking a place by analogy with other places through processes of association.

Accordingly, the literary universe itself comes to the definition of places like the London of Dickens, Kafkian Prague or Joyce’s Dublin, relating specific features of these authors and their works with cities they described in a particular way. And the other way around, ‘countless poems, stories, and novels have been based on or influenced by Homer’s Odyssey, including works by writers who, like Dante, never had the opportunity to read it’ (Turchi, 2004: 20).

‘The City that Never Sleeps’, ‘The City of Light’ or ‘The Eternal City’, to men-tion just some, belong to the collective memory beyond their physical experience and the reality of vision. Thus, the experience of a place is simultaneously framed by the spaces we actually know and have experienced elsewhere, as well as by the hunting for and recollection of others’ personal experiences, that is, by looking at something through someone else’s eyes.

Going back to the concept of urban image, usually implying a certain sense of identity, the juxtaposition of spatial conditions, the dislocation of spatial sequences, the contrast of layers that could, sometimes, meet and interfere illus-trate that identity depends on the point of view from which it has been mapped. Identity is not a hermetic category. It is plural and heterogeneous; it is a subjective category of the mind (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Display boxes as presented in the catalogue. Catalogue 190-191. Photographer: Refik Anadol.

Image, Representation and Reproduction

An image is, by definition, a representation of something that could be both men-tal and tangible, evoking reality by analogy or similarity with a domain other than the one that applies. Mental images build up our imagery’s memory: a collec-tion, assembly and association of personal and collective interpretations, implying the capacity to move between personal recollections. Tangible images are, gen-erally, representations through arts, in particular the visual arts, though we can think about literature or music as images as well, but that has only become visual through a mental process.

Therefore, we could say that mental images are constructions of the real and reconstructions of tangible images, but the reverse is also true: tangible images are constructions of mental images and reconstructions of the real. In that sense, the nature of an image cannot be equivalent to the real, but rather a representation that lies somewhere between subject and object, describing, evoking or turning visible an idea or phenomenon framed by previous categories of the mind, reflect-ing a particular experience of the world conditioned by those.

In the history of a city, the configurations of thought have been repositioned repeatedly, always according to different orders of priority and other internal orga-nizations in the redistribution of knowledge components. It is in the interstitial fractures within these discontinuities that the impulse to perceive, describe and enunciate reality differently arises. That is to say that representation has a time of its own, related not only to the spatiality of reality, but also to its temporality. Tak-ing Pierre Menard’s (re)writTak-ing of Quixote, not ‘other’ Quixote but ‘the’ Quixote, Borges’ account of the relation between the meaning of writing something in a specific way and its time highlights the importance of time in the configuration and reconfiguration of something that has been reproduced. And in that sense, reproduction implies a spatiotemporal depth that neglects its implied sense of imi-tation of the real–it associates a space of represenimi-tation with a represented time. This could also apply to space, and in fact it happens all the time when contempo-rary subjects inhabit spaces that belong to the past−as they manage to stay almost untouchable. Although remaining similar, the same does not happen to the scenes that take place there. Therefore, being a ‘copy’ of themselves in another time frame completely changes their meaning.

To present, represent or reproduce? That was the first question that arose while starting to build up the museum. After thinking about putting the objects in boxes according to the chronological order in which they appeared in the book, Pamuk realized that book and museum, although related, should have existences of their own, each telling a story (Pamuk, 2012: 18). Nevertheless, it is the narrative structure that organizes the museum and the arrangement of each vitrine or box. As with each chapter, the spatial constructions derived from the careful compositional structure of elements, usually foreign to each other, tak-ing advantage of their different natures, scales, colors, textures, etc., resulted in displays that could take on new meanings. If some of them are more straight-forward in their evocation; in others the ‘spatialization’ of non-visual issues such as happiness, pain, love, etc. asked for more metaphorical arrangements; while some boxes seem to draw from the surrealist culture. And the format of those, a kind of still life, is according to the underlying argument of the novel about the importance of the everyday and the ordinary, and of the clearer statement made through Pamuk’s Museum Manifesto.

As in the book, the boxes guide the visitor through an invisible line that can be related with Aristotle’s conception of time as a connecting element between isolated moments. And it is not by chance that Aristotle’s time spiral is drawn on the ground floor of the museum: one of the arguments that comes out of the book structure is

Fig. 4. Display boxes as presented in the catalogue. Catalogue 100-101. Photographer: Refik Anadol.

the different compasses that time takes according to our own experience. As well as the text challenging the notion of time–official time versus personal time–the dis-play windows in the museum challenge scale. The importance of things is not coin-cident with real scale, but rather with a sentimental scale (fig. 4). It remembers the size of Sanzelize Boutique’s yellow bag by comparison, for instance, with Taksim Square. Forty-two days of Kemal’s life are described in the book in almost as many chapters (twenty-four) as the eight years in which he went almost daily to the Kes-kins’ family house to have dinner and watch television (thirty chapters), described in the same manner, apart from small details like Füsun’s facial expressions or little objects of the house touched by her, including cigarettes or spoons. And yet, if the first 42 days seem to be so quick, the experience of the reader reading Kemal’s fol-lowing eight years is the same as his agony that everything stays the same. On the contrary, in the museum, those chapters do the reverse. They emphasize all those apparently unimportant slight differences, but also the awareness that those eight years did not have the same speed as the calendar.

Real and Imaginary –

Simulacra and the Role of Phantasía

For the Greeks, the word phantasia originally meant the human faculty of invent-ing or evokinvent-ing images, and Aristotle described it as somethinvent-ing between the real and the unreal, responsible for the creation of intelligible forms of art, i.e. the (re) creation of another real by analogy.

When the French philosopher Montesquieu visited Venice for the first time in the 18th century, he stated that he was visually delighted but at the same time desolated in his heart and head. This was the dilemma of simulacra, a theme that became very fashionable with the desire for illusion during the 18th century. If in the Quattrocento Bruneleschi’s early demonstration of linear perspective allowed the coincidence of natural and artificial perspective, and representation as equiva-lent to the reality of vision, in the 18th century oddly-named instruments such as telescopic tubes, magnifiers, zograscopes, divination boxes or peepshows animated the debate around visual illusions, many times equaled to magic. The act of seeing was no longer understood as only a biological faculty of the eyes.

In Simulacres et Simulation (1981), Jean Baudrillard defines the term as follows: ‘simulation is no longer the simulation of a territory, of a reference, of a substance but rather the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: hyper-real, that is, since it is not imitation, or bending, or even parody, it is a substitution in the real of signs that, in practice, never have the opportunity to produce themselves’ (Baudrillard, 1991: 8).

This postmodern nihilism, that nothing is unique, led precisely to the representa-tion of reality through the image that is consumed as an alternative to the impos-sibility of the new: the new as a reinvention of the existing, as a simulacrum of a past reality that becomes the actual one, through the deliberate pastiche and collage of other objects, other places, other realities, contexts and times.

As in the novel, the writing and the objects are intimately linked though the museum is not an illustration of the book, any more than the book is an explana-tion of the museum (Pamuk, 2012: 18). Whether the center of the story is Istan-bul, the romance that takes place there, or Pamuk himself is hard to tell, empha-sizing the role of representation, and its specific formats. Instead, they construct a dialectic relation between narratives of the same story and therefore transform that sameness into something alike.

The experience of the museum becomes detached from the story. Istanbul leaves the role of stage and takes on that of protagonist through those same ephemera, bric-a-brac, and clutter that portrayed, chapter by chapter, the whole novel. In Des espaces autres, a lecture delivered at the architectural society of Tunis in 1967, Foucault describes space as capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces initially considered incompatible. While utopian places are non-existent spaces, heterotopias are material and immaterial at the same time, being related to a specific and real place and engaging relationships with other real and mental sites as well. Although interpreted in a variety of different ways, Foucault’s concept of heterotopia allows an understanding of the real as both tangible and fictional and the creation of a ‘second real’ derived from the intersection of more complex, per-sonal and subtle associations with other spaces by means of mnemonic processes of collage. This means that space itself is not experienced as a fixed image in the mirror, but rather a series of images constructed from the real and from the ways in which the subject experiences that real.

The displayed compositions—or artificial landscapes—build up a panoramic cityscape which is not coincidental with the reality of vision but, on the contrary, conveys an urban identity beyond its physical form and specific time, that encour-ages a deeper understanding of the multiple and stratified meanings of the city. The city becomes four-dimensional; Kemal and Füsun are just two among many other characters and hidden stories behind the daily life objects, the pictures, the journal fragments, the brands and their logos, the paintings and the postcards that are frozen in photographs, simultaneously representing Pamuk’s sentimental Istanbul since his childhood and during the creation of the Museum of Innocence, in dialectics with that of Kemal and Füsun, and our own imaginary of the city, different if drawn from the book, the museum, the catalogue or from its physical experience. If Pamuk’s first appearance in the novel is very brief and inconsequent, here it clearly becomes the wish of intertwining reality and fiction, but, what is more, to question representation in terms of the relatively stable roles of writer, story, object of the story and reader, the act of writing becomes the object of rep-resentation, recalling Las Meninas (1656), the famous oeuvre by Diego Velasquez, in what it can be pointed to as a thesis, a self-questioning of representation that transcends the painting. Pamuk does it in a slightly different manner: each visitor to the museum is actually responsible for building up his own narrative.

The Innocence of Objects: Still Life Photographs

The artist invents while designing and the particular technique that he uses always imposes, a certain discriminatory order (Francastel, 1963: 316), reflecting orga-nizations by analogy: ‘[…] the images that words generate in our minds are one thing; the memory of an old object used once upon a time is another. But imagi-nation and memory have a strong affinity’ (Pamuk, 2012: 18). Even by choosing the language in which we will write, and by choosing to write rather than paint or sing, we are defining and delineating the world. We describe what we see and in the way we see it. And the specific format we choose to describe something, and the special technique within the format, implies a selection of what is going to be described, an emphasis on specific aspects, etc.

Exploring the various ways of interpreting place, in this specific case Istanbul, and the new outcomes from the relationships established between them encourages us

to think of a city beyond its actual physical and tangible form and to look at real-ity as multi-layered and where personal and the seemingly insignificant acquire legitimization and autonomy.

Kant questioned knowledge as it exists, considering that it does not serve to depict reality but, on the contrary, to dictate the empirical world as it should be built. Following this argument we can say that real knowledge in architecture is its rep-resentation, primarily graphic and written—the means by which one’s perceive space—and ultimately translation into a physical form, which may be consid-ered a knowledge (re)representation. As previously outlined, the understanding of representation should be expanded and separated from its purely communicative role, entailing a reconfiguration of artistic representation that replaces the meth-ods preceding the reality of vision to the reality of knowledge, i.e. to a reality that does not exist as it is perceived but as it is conceived, assuming a more critical role. Accordingly, representation should be understood not as an autonomous feature but rather as a potential device to (re)transform reality and anticipate the future. For that, we need to recover the meaning of narrative in representations of exist-ing places.

The Museum of Innocence is the architecture of a sequence of scenes that build up space from the reconstruction of careful compositional structures that gener-ate new relationships, producing dispargener-ate personal, visual and mental images captured by the camera as still lifes.

Bibliography

Jean Baudrillard, Simulacros e simulação (Lisboa: Relógio de Água, 1991). Jorge Luis Borges, Obras completas 1923-1949 (Lisboa: Editorial Teorema, 1998). Walter Benjamin, Rigorous Study of Art: On the First Volume of the

Kunstwissen-Schaftli-che Forschungen (October 47: 84-90, Winter 1988).

Italo Calvino, Collection of Sand (London: Penguin Classics, 2013).

Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 1988).

Michel Foucault, As Palavras e as Coisas (Lisboa: Edições 70, 2006).

Michel Foucault, Other Spaces—the principles of heterotopia, in Lotus International (Milano: Elemond Periodica, 48/49, 1986), 9-17.

Pierre Francastel, Arte e técnica nos séculos XIXe XXe (Lisboa: Livros do Brasil, 1963).

Orhan Pamuk, O Museu da Inocência (Lisboa: Editorial Presença, 2008). Orhan Pamuk, The Innocence of Objects (New York: Abrams, 2012).

Alberto Pérez-Gómez, Louise Pelletier, Architectural Representation and the Perspective Hinge (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1997).

Peter Turchi, Maps of the Imagination. The Writer as Cartographer (San Antonio, TX: Trinity University Press, 2004).

Anthony Vidler, Diagrams of Diagrams: Architectural Abstraction and Modern Representa-tion, in Mark Garcia (ed.), The Diagrams of Architecture (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2011), 54-63.