Vol.50, n. 1 : pp.113-120, January 2007

ISSN 1516-8913 Printed in Brazil BRAZILIAN ARCHIVES OF

BIOLOGY AND TECHNOLOGY

A N I N T E R N A T I O N A L J O U R N A L

Genetic Transformation of

Drosophila willistoni

Using

piggyBac

Transposon and GFP

Manuela Finokiet1, Beatriz Goni2 and Élgion Lúcio Silva Loreto1,3*

1

Curso de Pós Graduação em Biodiversidade Anima; Universidade Federal de Santa Maria;97105-900;

manufinokiet@yahoo.com.br; Santa Maria - RS - Brasil. 2Sección Genética Evolutiva; Facultad de Ciências;

Universidad de la República; Iguá 4225; 11400, bgoni@fcien.edu.uy; Montevideo - Uruguay. 3Departamento de

Biologia; elgion.loreto@pesquisador.cnpq.br; Universidade Federal de Santa Maria; Santa Maria - RS - Brasil

ABSTRACT

Studies were carried out on the use of piggyBac transposable element as vector and the green fluorescent protein

(EGFP) from the jellyfish, Aquorea victoria, as a genetic marker for the transformation of Drosophila willistoni.

Preblastoderm embryos of D. willistoni white mutant were microinjected with a plasmid containing the EGFP

marker and the piggyBac ITRs, together with a helper plasmid containing the piggyBac transposase placed under

the control of the D. melanogaster hsp70 promoter. G0 adults transformants were recovered at a frequency of

approximately 67%. Expression of EGFP in larvae, pupae and adults was observed up to the third generation,

suggesting that this transposon was not stable in D. willistoni. Transformed individuals displayed high levels of

EGFP expression during larvae and adult stages in the eye, abdomen, thorax and legs, suggesting a wide

expression pattern in this species than reported to other species of Drosophilidae.

Key words: Transposable elements, insect transgenesis, germ-line transformation, fluorescent protein marker, microinjection

* Author for correspondence

INTRODUCTION

Genetic manipulations of insects and other arthropods are an important tool for the study of the molecular basis of development and the evolutionary process (Horn and Wimmer, 2000; O'Brochta and Atkinson, 1998). The use of these methodologies is also being considered as a possible solution to certain medical and agricultural problems caused by some insects, through the cautious releasing in nature of insects with desirable genetic alterations (Kidwell and Wattam, 1998; Irvin et al., 2004). A widely method employed for insect germ-line transformation utilizes transposon-based vectors in

The germ-line transformation was first demonstrated more than 20 years ago in

Drosophila melanogaster by the use of the transposable P element (Rubin and Spradling, 1982). However, studies in many different species showed that this element was non-functional outside the Drosophilidae. The P-element system is dependant on the presence of several host factors specific to this species, or to closely related species. This has restricted the P mediated transformation to a few species of subgenus

Sophophora of the genus Drosophila (Handler et al., 1993). The first transposon-mediated transformation of a non-drosophilid insect was registered 13 years later in the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata, using the minos-mediated transformation (Loukeris et al., 1995).

Alternative transposable elements as minos, mariner, Hermes and piggyBac have recently been used for transformation in more than 15 different species of insects, including some that are important for human health and agriculture (Robinson, et al., 2004). The properties of the bacterial transposon TN5 have also been tested looking for improving insect transgenesis methods (Rowan et al., 2004).

The piggyBac element was originally identified by its association with a mutation in a baculovirus passed through the Trichoplusia ni cell line culture (Fraser et al., 1983; Cary et al., 1989). This transposon is naturally found in the genomes of some lepidopteran (Cary et al., 1989). The

piggyBac element was first used to transform the medfly, C. capitata (Handler et al, 1998), and more recently it has been used for transformation of many other species (Horn and Wimmer, 2000; Handler and McColombs, 2000; Handler, 2001; Horn et al., 2002; Atkinson, 2002; Robinson et al., 2004; Irvin et al., 2004).

Other important component for the effective development of insect transformation technology is the use of genetic markers that allows recognition of the transformed individuals (O'Brochta and Atkinson, 1997). Eye color genes are quite often used as transformation markers in insects carrying eye color mutations allowing the identification of transformants by mutant-rescue selection. In these cases, the marker gene represents the wild-type allele of a gene that, when mutated, causes a recessive, visible but viable phenotype.However, the lack of suitable recipient mutant strains for most insects of medical and agricultural importance limits their application.

Initially, the search for dominant-acting selection markers that could act independently of pre-existing mutant strains focused on genes which confer chemical or drug resistance. These marker systems showed low reliability and efficiency (Handler, 2001; Horn et al., 2002).

Recently, an interesting marker system was developed based on the properties of fluorescent proteins like GFP (green fluorescent protein) and their variants (Horn et al., 2002). The GFP gene from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria (Prasher et al., 1992) is well suited, since it is easily detectable in vivo and has proved to be functional in different tissues of many heterologous systems (Tsien, 1998). It has been used in several organisms as insects, plants, fish, mice and cells of mammals, (Amsterdam et al., 1995; Plautz et al., 1996; Bagis and Keskintepe, 2001). For the expression control of GFP several promoters have been used. Constitutive promoters active in all cells provide the advantage of allowing selection of transformants at all stages since GFP fluorescence can be scored in living embryos, larvae, and adults. The promoter polyubiquitin of D. melanogaster successfully employed by Handler and Harrel (1999) allowed the generation of a transformation marker and the identification of transgenic flies in D. melanogaster. Another commonly used constitutive promoter to drive EGFP is derived from the D. melanogaster actin5C gene tested in Aedes aegypti, Anopheles stephensi and others insects (Pinkerton et. al., 2000; Catteruccia et al, 2000). For the stable germ-line transformation of lepidopteran species, the

Bombyx mori A3 cytoplasmic actin gene promoter (BmA3) was chosen to drive EGFP in the silkworm B. mori (Tamura et. al., 2000). At present, transformation markers based on constitutive promoters have only been applied to closely related species, and it is questionable if any such promoter can be functional across insect orders (Horn et al., 2002).

Other constructs already tested in D. melanogaster

and Tribolium castaneum which have wide applicability usage as promoters are derived from the rhodopsin gene (3xP3) from Drosophila

genetic circuit governs eye development of all metazoan animals, which is under the control of the transcriptional activator Pax-6/Eyeless

(Callaerts et al., 1997). This marker construction (3xP3-EGFP) expresses most strongly in the brain, eyes, and ocelli in adults, but can also be observed from several structures in pupae and larvae (Handler et al., 1998). The evolutionary conserved “master regulator” function of Pax-6 in eye development of metazoan suggests that this marker should be applicable to all eye-bearing animals (Callaerts et al., 1997; Handler, 2001; Horn et al., 2002). Furthermore, the small size (1.3 kb) of the 3xP3-EGFP marker provides an additional advantage, as it allows small transposon constructs resulting in high transformation rates (Horn et al., 2002). This transformation system has been applied to generate transgenic insects in different orders as Diptera, Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera and Coleoptera (Horn et al.,2002; Lorenzen et al., 2003; Robinson et al., 2004; Irvin et al., 2004).

Among the Drosophila species, D. willistoni

stands out for possessing a great genetic variability and ecological versatility, being one of most studied of the family Drosophilidae. The genome of this species was chosen to be completely sequenciated

(http://bugbane.bio.indiana.edu:7151/). Despite the great variability and importance in evolutionary and genetic studies, D. willistoni has not been tested in experiments of genetic transformation. This work aimed to achieve the genetic transformation of a mutant white of D. willistoni using the binary system (vector/auxiliar) introducing a gene marker that codified the protein EGFP, through the microinjection of recombinant plasmids in pre-blastoderm embryos. The pattern of expression of the protein in the larva and adult, and the stability of the transformants were analyzed along six generations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila Stocks and Rearing Conditions The D. willistoni white mutant strain EM1.00 described by Goñi et al. (2002) was used for genetic transformation. The strain were maintained in standard cornmeal medium (Klein et al., 1999) at constant temperature and humidity (20oC +/- 2oC; 60% r.h.).

Plasmids

The vector pBac [3xP3-EGFP] (Horn and Wimmer, 2000) containing the transposon

piggyBac inverted terminal sequences (ITRs) necessary for mobility as well as the marker gene EGFP were used. As helper plasmid was used pBƒ´Sac containing the piggyBac functional transposase gene which possesses a deletion in the 5 ' ITR enabling it to transpose (Handler and Harrel, 1999). The plasmids were prepared according to the PEG (polyethylene glycol) purification protocol (Fujioka et al., 2000). The solution for microinjection had a final concentration of 100 µg/ml of each plasmid in ultra-pure water.

Microinjection and Cultural Treatments

The methodology used for microinjection and post-injection treatments is described in Deprá et al. (2004). The hatching larvae were maintained separately in banana medium consisting of 20% (w/v) banana and 1.5% (w/v) agar. After pupation, they were transferred to a standard cornmeal medium.

Analysis of Transformants

The adult flies outcoming from the microinjected eggs (Go) were backcrossed to white flies and the progeny and subsequent generations (G1-G5) were

examined to identify the fluorescence expression. A diodo laser system was used for this analysis where a filter of emission of 510nm was adapted to stereomicroscopic lens. The observations were made in a dark room (Deprá et al. 2004). The stability of the transgenic lineages was analyzed by the transmission of the transgene to the next generation. During six generations, the individuals were routinely examined and the frequency of larvae and adults that manifested fluorescence was annotated.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

obtained by other authors for other species. In a review about the use of different transposons and genetic markers, Handler and Harrel (1999)

describe transformation rates, to piggyBac-GFP varying from 6 to 7%.

Figure 1 - Survival percentages in larvae, pupae and adult, and percentage of established and transformed lineages

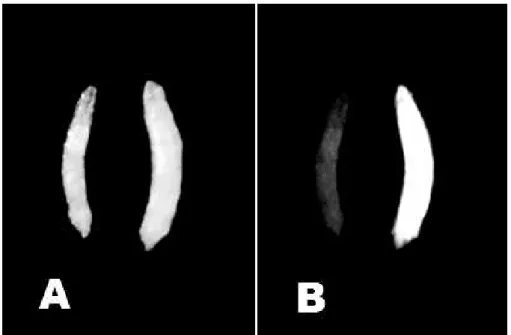

According to Horn et al. (2002), one of the obstacles for the use of fluorescent markers in insects is the auto fluorescence generated by many biological materials, as ingested foodstuff, malpighian tubules, the chitinous exoskeleton and necrotic tissue. Therefore, an appropriate emission filter was used to help distinguish the yellowish auto fluorescence of the fluorescence green resultant of the expression of EGFP in the flies. Using this method, it was possible to verify that all the transformed larvae expressed the protein GFP in the whole body, but they presented variation in the intensity among the lineages. The fluorescence of GFP easily could be differentiated of the auto fluorescence common in controls larvae (Fig.2). Although, for adults another pattern was observed, the expression was more intense in the eyes; however, it could also be observed in the abdomen, thorax and legs (Fig. 3).

The results demonstrated that the piggyBac

transposable element was an efficient gene-transfer vector system for Drosophila willistoni. Actually, it was much more efficient to D. willistoni genetic transformation, producing a higher frequency of transformants than in other dipterans so far investigated, as D. melanogaster

and Ceratitis capitata (Handler et al., 1998). The transposition rate for each transposon varied

amongst the tested species. The piggyBac

transposon could be extremely active in D. willistoni. Other fact that could be an indicative of high transposition activity of piggyBac in this species was the observation that GFP expression was maintained for only three generations what could be explained by a lost, in the isoline, caused by mobilization of the transposon carrying the EGFP gene. While piggyBac was not present in the D. willistoni genome, some intrinsic transposase source present in the D. willistoni

genome could be able to mobilize piggyBac. As illustration of this kind of cross-mobilization, was

hobo transposable element from D. melanogaster that could be mobilized by intrinsic sources in a large number of Drosophilidae species (Handler and Gomez, 1995). Other hypothesis for the missing of EGFP expression in D. willistoni in the older generations could be the inactivation of the chromosomal region containing the transgene. Garcia (2004) demonstrated that D. willistoni

Figure 2 - Pattern of 3xP3-EGFP gene expression in D. willistoni transgenic larvae. (A) Control (left) and transformed (right) larva. (B) Yellowish auto fluorescence (left) and the green fluorescence expression of EGFP (right) in the whole larvae.

A high mortality at the egg-larvae developmental stage, about 97.2% was observed, a similar rate was also described by several authors (Irvin et al., 2004). Usually, this high mortality was due to problems associated with the technique or to the specific stresses caused by manipulation. According to O'Brochta and Atkinson (2004), the preparation of embryos for injection, the insertion of needles in the eggs and the procedures post-injection were critical steps for the success in the development and maintenance of flies and it was characteristic for each species. Hanazono et al (1997) suggested that the high mortality at the beginning of the development could be associated with the possible toxicities of the GFP and its variants, when expressed in high levels.

According to Atkinson (2002), the transposable elements and the fluorescent proteins seemed to have general application in the production of transgenic insects. However, the use of appropriate promoters to command the expression of the reporter proteins, as well as the stability of the transgene, could depend, or be influenced by the species or the family of the insect to be transformed.

Horn and Wimmer (2000) and Horn et al. (2002, 2003) described the expression of the GFP under the tissue-specific artificial promoters control (3xP3) in several species of Drosophila and observed the reporters protein expression in the eyes and occelii of adult flies. However, some of the transformants of D. willistoni showed a wider expression that was previously described in other species. As suggested by Atkinson (2002) this promoter could have a diverse expression in different species as it happened in D. willistoni.

Lorenzen et al. (2003) also obtained the most obvious expression in the eyes and brain with

Tribolium castaneum. However, in several additional insertions novel EGFP expression patterns appeared, suggesting that the EGFP marker was influenced by chromosomal enhancers sequences near the sites of piggyBac integration. This was not surprising, since previous reports have shown that the 3xP3 promoter acted as an enhancer detector (Horn et al., 2002, 2003). As seen in the Figs. 2 and 3, the EGFP expression was not restricted solely to the eyes in adults. This was an interesting observation considering the modest phylogenetic distance splitting D. willistoni and D.

melanogaster, and the fact that 3xP3 promoter worked precisely in the later species.

The results of the experiment presented here demonstrated that the transformation system composed by transposon piggyBac and marker EGFP was quite efficient to mediate the transformation in D. willistoni. Meanwhile, no stable isolines were obtained suggesting a high mobilization of the piggyBac in this species. The utilization of a concentration of a plasmid smaller that the one usually employed by other researchers (Handler et al., 1998) did not impede the successful genetic transformation of D. willistoni, being the species that showed the highest transformation rate using piggyBac as a vector.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Ernest Wimmer from the Universitat Bayreuth, Germany, for providing the pBƒ´Sac and pBac [3xP3-EGFP] plasmids, to Dr. Vera Lúcia Valente for suggestions and to Mr. Fernando Luces for the English revision of the manuscript. This study was partly supported by CSIC (Uruguay), FAPERGS, CNPq, and FIPE-UFSM (Brazil).

RESUMO

Descrevemos neste trabalho a transformação genética de Drosophila willistoni empregando o elemento transponível piggyBac como vetor e o gene EGFP (green fluorescent protein ) retirado da água-viva Aquorea victoria, como marcador de transformação. Embriões de D. willistoni em estágio pré-blastoderme, mutantes para o gene

nos olhos, abdome, tórax e patas, mostrando um padrão de expressão mais amplo nesta espécie do que o registrado para outros drosofilídeos.

REFERENCES

Amsterdam, A., Lin, S. and Hopkins, N. (1995), The

Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein can be

used as a reporter in live zebrafish embryos. Dev. Biol., 171, 123-129.

Atkinson, P.W. (2002), Genetic engineering in insects of agricultural importance. Insect Biochem. Mol.

Biol.,32, 1237-1242.

Bagis, H. and Keskintepe, L. (2001), Application of green fluorescent protein as a marker for selection of transgenic embryos before implantation. Turk J. Biol., 25, 123-131.

Berghammer, A.J., Klingler, M. and Wimmer, E.A. (1999), A universal marker for transgenic insects.

Nature, 402, 370-371.

Callaerts, P., Halder, G. and Gehring, W.J. (1997), PAX-6 in development and evolution. Annu. Rev.

Neurosci., 20, 483-532.

Cary, L.C., Goebel, M., Corsaro, H.H., Wang, H.H., Rosen, E. and Fraser, M.J. (1989), Transposon mutagenesis of baculoviruses: analysis of

Trichoplusia ni transposon IFP2 insertions within the

FP-Locus of nuclear polyhedrosis viruses. Virology, 161, 8-17.

Catteruccia, F., T. Nolan, T.G., Loukeris, C., Blass, C., Savakis, F.C., Kafatos and Crisanti. A. (2000), Stable germline transformation of the malaria mosquito

Anopheles stephensi. Nature, 405, 959-962.

Deprá, M., Sepel, L.M.N. and Loreto, E.L.S. (2004), A low-cost methodology to Drosophila transformation with GFP. Genet. Mol. Biol., 27, 70-73.

Fraser, J., Smith, G.E. and Summers, M.D. (1983), Acquisition of host-cell DNA sequences by baculoviruses relationship between host DNA insertions and FP mutants of Autographa-californica

and Galleria-mellonella nuclear polyhedrosis viruses.

J. Virol.,47, 287-300.

Fujioka, M., Jaymes, J. B., Bejsovec, A. and Weir, M. (2000), Production of transgenic Drosophila.

Methods Molec. Biol., 136, 353-363.

Garcia, R.N. Variabilidade Genética e ecológica de

Drosophila willistoni (DIPTERA,

DROSOPHILIDAE): uma abordagem molecular através do isolamento e caracterização de fragmentos heterogêneos de DNA. PhD Thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil. Goñi, B., Parada, C., Rohde, C. and Valente, V.L.S.

(2002), Genetic characterization of spontaneous mutations in Drosophila willistoni. I. Exchange and non-disjunction of the X chromosome. Dros. Inf.

Serv., 85, 80-84.

Hanazono, Y., Yu, J.M., Dunbar, C.E. and Emmons, R.V. (1997), Green fluorescent protein retroviral vectors: low titer and high recombination frequency suggest a selective disadvantage. Hum. Gene Ther., 8,

1313-1319.

Handler, A.M. (2001), A current perspective on insect gene transformation. Insect Biochem Molec. Biol 31,

111-128.

Handler A.M. and Gomez SP. (1995), The hobo

transposable element has transposasedependent and -independent excision activity in drosophilid species.

Mol. Gen. Genet.,247, 399-408.

Handler, A.M. and Harrel, R.A. (1999), Germline transformation of Drosophila melanogaster with the

piggyBac transposon vector. Insect Molec. Biol., 8,

449-457.

Handler, A.M. and Harrel, R.A. (2001), Transformation of the Caribbean fruit fly with a piggyBac transposon vector marked with polyubiquitin-regulated GFP.

Insect Biochem. Molec. Biol.,31, 201-207.

Handler, A.M. and McColombs, S.D. (2000), The

piggyBac transposon mediates germline

transformation in the Oriental fruit fly and closely related elements exist in its genome. Insect Molec. Biol., 9, 605-612.

Handler, A.M., Gomez, S.P. and O’Brochta, D.A. (1993), A functional analysis of the P-element gene-transfer vector in insects. Arch. Insect Biochem.

Physiol., 22, 373-384.

Handler, A.M., McColombs, S.D., Fraser, M.J. and Saul, S.H. (1998), The lepidopteran transposon vector, piggyBac, mediates germline transformation in the Mediterranean fruitfly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.

USA,95, 7520-7525.

Horn, C. and Wimmer, E.A. (2000), A versatile vector set for animal transgenesis. Dev. Genes Evol., 210, 630-637.

Horn, C., Offen, N., Nystedt, S., Hacker, U. and Wimmer, E. (2003), piggyBac-based insertional mutagenesis and enhancer detection as a tool for functional insect genomics. Genetics, 163, 647-661.

Horn, C., Schmid, B.G.M., Pogoda, F.S. and Wimmer, E.A. (2002), Fluorescent transformation markers for insects transgenesis. Insect Biochem. Molec. Biol.,32, 1221-1235.

Irvin, N., Hoddle, M.S., O’Brochta, D.A, Carey, B. and Atkinson, P.W. (2004), Assessing fitness costs for transgenic Aedes aegypti expressing the GFP marker and transposase genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 101, 891-896.

Kidwell, M. G. and Wattam, A. R. (1998), An important step forward in the genetic manipulation of mosquito vectors of human disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA,95: 3349-3350.

Klein, C.C., Essi, L., Golombiesk, R.M. and Loreto, E.L.S. (1999), Disgenesia do híbrido em populações naturais de Drosophila melanogaster. Ciência e

Lorenzen, M. D., Berghammer, A.J., Brown, S.J., Denell, R.E., Klingler, M. and Beeman, R.W. (2003),

piggyBac-mediated germline transformation in the

beetle Tribolium castaneum. Insect Molec. Biol., 12, 433-440.

Loukeris, T.G., Livadaras, I., Arca, B., Zabalou, S. and Savakis, C. (1995), Gene transfer into the Medfly,

Ceratitis capitata, with a Drosophila hydei

transposable element. Science,270, 2002-2005. Miller, W.J. and Capy, P. (2004), Mobile Genetic

Elements. Methods in Molecular Biology, vol. 260.

Humana Press Inc., Totowa. New York.

O’Brochta, D.A. and Atkinson, P.W. (1997), Recent developments in transgenic insect technology.

Parasitology,13, 99-104.

O’Brochta, D.A. and Atkinson, P.W. (1998), Building the better bug. Sci. Am., 279, 90-95.

O’Brochta, D.A. and Atkinson, P.W. (2004),

Transformation systems insects. In: Mobile Genetic

Elements, ed. W. J. Miller and P. Capy. Methods in

Molecular Biology, vol. 260, Humana Press Inc., Totowa. New York, pp. 227-253.

Pinkerton, A.C., Michel, K., O’Brochta, D.A. and Atkinson, P.W. (2000), Green fluorescent protein as a genetic marker in Aedes aegypti. Insect Molec. Biol., 9, 1-10.

Plautz, J.D., Day, R.N., Dailey, G.M., Welsh, S.B., Hall, J.C., Halpain, S. and Kay, S.A. (1996), Green fluorescent protein and its derivatives as versatile markers for gene expression in living Drosophila

melanogaster, plant and mammalian cells. Gene, 173,

83-87.

Prasher, D.C., Eckenrode, V.K., Ward, W.W., Prendergast, F.G. and Cormier, M. J. (1992), Primary structure of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein. Gene,111, 229-233.

Robinson, A.S., Franz, G. and Atkinson, P.W. (2004), Insect transgenesis and its potential role in agriculture human health. Insect Biochem. Molec. Biol.,34, 113-120.

Rowan. K.H., Orsetti, J., Atkinson, P.W. and O’Brochta, D.A. (2004), Tn5 as an insect gene vector.

Insect Biochem. Molec. Biol.,37, 695-705.

Rubin, G.M. and Spradling, A.C. (1982), Genetic transformation of Drosophila with transposable element vectors. Science,218, 348-343.

Tamura, T., Thibert, T., Royer, C., Kanda, T., Abraham, E., Kamba, M., Komoto, N., Thomas, J.L., Mauchamp, B., Chavancy, G., Shirk, P., Fraser, M., Prudhomme, J.C. and Couble, P. (2000), Germline transformation of the silkworm Bombyx mori L. using

a piggyBac transposon-derived vector. Nature

Biotechnol., 18, 81-84.

Tsien, R.J. (1998), The green fluorescent protein. Annu.

Rev. Biochem, 67, 509-544.