Bull Pan Am He& Organ

E(3),

1981.

PROTEIN-CALORIE

MALNUTRITION

IN THREE

BRAZILIAN

STATE CAPITALS:

SdO LUfS,

RECIFE,

AND SdO PAULOlJ

Malaquias

Batista Filho, 3 Maria Anunciada Ferraz de Lucena,3 and

Heloisa de Andrade Lima Coelho3

A stuaj~ of protein-calorie malnutrition in the Brazilian state capitals of Reci- fe, Sr70 Lu$ and Srio Paul0 was conducted to compare the situation prevail-

ing in those cities and to assess dtjknt rnethoak of nutritional evaluation. The results clear& showed sign$cant di&rences in the protein-caloric mal- nutrition patterns prevailing in the three cities.

Introduction

Because they relate to an essentially ecolog-

ical problem, protein-calorie malnutrition

patterns can be quantitatively and qualita-

tively differentiated in terms of a population’s

demographic characteristics, food consump-

tion, and non-nutrition-related pathologies.

Indeed, the comparative study of malnutrition

(with regard to both its magnitude and mani-

festations) represents one of the most valid

descriptive and analytical methods of epi-

demiologic evaluation.

Obviously, however, inferences drawn

from comparative studies will only be con-

sistent when uniform, standardized method-

ologies are used, it being impossible to gmer-

alize when similar situations are evaluated

with different methods. Moreover, the pro-

visional nature of the tools for gauging nutri-

tional status has led to a multiplicity of meth-

ods being employed-making close compar-

‘Also published in Portuguese in the B&tin de la Of;- ck Sanitarih Panmerkana 90(1):48-58, 1981.

ZCollection of the Recife and SZo Luis data was sup- ported by the World Health Organization, and collection of the SZo Paul0 data was supported by the Ford Founda- tion.

3Assistant Professor, Department of Nutrition, Federal University of Pernambuco; and research fellow, National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (Brazil).

ison of results impossible and removing all op-

portunity for obtaining a geographic overview

of the nutrition problem.

These fundamental observations suggested

that it would be desirable to conduct a nutri-

tional survey in several major Brazilian cities

with the broad goal of detecting similarities

and differences in the prevailing patterns of

protein-calorie malnutrition (PCM). The

cities selected for this purpose were SBo Lufs

(in Maranhgo State), Recife (in Pernambuco

State), and SZo Paul0 (in SZo Paul0 State).

Although nutritional surveys had been con-

ducted fairly recently in the three cities

(3, II, 21), different surveys were developed

independently, and so the potential for com-

parison was limited. Specifically, in SZo Lufs

and Recife the study populations’ nutritional

status had been defined in terms of the G6mez

(15), Jelliffe (17), and Waterlow (33) classi-

fications, with the Harvard table (29) being

used as the anthropometric standard. In SZo

Paulo, on the other hand, the subjects were evaluated in terms of the G6mez (15), Ariza-

Ma&as (I), Seoane-Latham (modified by

one of ourselves) (31, and Kanawati-McLaren

(20) classifications; and the anthropometric

standard used was the Santo And& IV stan-

dard officially recommended by the Brazilian

Pediatric Society and the National Food and

Nutrition Institute (24).

Figure 1. A map of Brazil showing the location of the three

state capitals included in the study.

Nevertheless, the availability of anthro-

pometric data on children under five years of age in each of these cities presented an oppor-

tunity to develop various lines of study of

PCM in these areas through application of a

single methodology. Such work, it was felt,

would enhance the possibilities for drawing in-

ferences about the geographic distribution of

PCM in Brazil.

Background Data

SIo Luis is a city of 300,000 inhabitants in

the western part of the Brazilian Northeast.

Information based on hospital statistics sug-

gests that the prevalence of kwashiorkor is

higher there than would normally be expected

in other cities. During a visit to the Children’s

Hospital of SZo Luis, one of the authors con-

firmed that more than half the children admit-

ted had edema or a history of edema. The

rural areas near the city are inhabited largely

by families engaged in the cultivation of rice,

cassava, and corn and the extraction of ba-

bassu-palm oil. This pattern of activities pre-

sumably exerts a strong influence on both mi- gratory flows affecting the city and the food supplied to the population.

Recife, a Northeast city with 1,300,OOO in-

habitants, is in an area economically domi-

nated by sugar-based agroindustry and has at-

tained an intermediate level of industrial de-

velopment. The city thus presents a cultural

and economic picture quite different from that of SIo Luis. Data from the Inter-American

Investigation of Mortality in Childhood (31)

Batista et al. l PCM IN BRAZIL 233

nutrition associated with infections in the

mortality “model” found locally in Recife.

SZo Paul0 is now Latin America’s most

populous city and largest industrial center; it

attracts immigrants from all parts of Brazil

and even from other countries (notably Japan,

Italy, Portugal, and Spain). It therefore pos-

sesses characteristics markedly different from

those of both SZo Luis and Recife. And even

though the Inter-American Investigation of

Mortality in Childhood found a frequent as-

sociation between PCM and mortality in SHo

Paul0 (31), the United Nations Food and

Agriculture Organization (FAO) has classified

SZo Paul0 (like the rest of southern Brazil) as

an area where PCM is probably not a public

health problem (30).

Objectives

It was felt that application of uniform para-

meters, besides detecting quantitative nutri-

tional differences, would be likely to show

qualitative differences in the forms of mal-

nutrition prevailing in each of these cities.

Such qualitative differences would be attrib-

utable to variations in prevailing environ-

ment, agent, and host relationships resulting

in different levels of adaptation in each area.

And so, by identifying the “adaptational bio-

types” (22) associated with the nutritional

status of a given population, it should be

possible to arrive at a reasonably reliable

determination of the end result of the interac-

tion of these three elements.

It is also very possible that prevalences of

the various types of PCM in Brazil’s state

capitals and major cities can be fundamentally

represented as intermediate between those

found in SBo Paul0 on the one hand and SBo Luis and Recife on the other. That is, it can be assumed with reasonable assurance that the

prevalence of PCM in the major Brazilian

cities ranges between minimum values (such

as those found in SBo Paulo) and maximum values (such as those found in Recife and S?io

Luis). For few large Brazilian cities have con-

ditions significantly better than SIo Paulo’s,

while Recife and SIo Luis provide notable ex-

amples of poor urban communities. Conse-

quently, the information collected could be

used as a possible point of reference for assess-

ing the prevalence of PCM throughout the

country, or at least for constructing prelimi-

nary geographic models of PCM distribution

in densely populated urban areas.

Another objective was to study the meth-

odology for evaluating nutritional status. For

the most part, anthropometric indicators-or

at least the criteria employed to interpret

them-can still be considered experimental.

With the exception of the GBmez classification

and arm-circumference measurement (2,4,8,

l&12,13,14,16,19, and 25), these indicators

have not been extensively applied to diverse

populations using standardized techniques.

This situation is doubly inconvenient; besides

impeding comparative studies of different re-

gions, it also makes it hard to evaluate the ef-

fectiveness of the indicator used; for such an

evaluation obviously depends upon the indi-

cator’s performance (sensitivity and speci-

ficity) in a variety of diverse situations. In this vein, the project described here ex-

plored two subjects in a preliminary manner.

These were (a) correspondence between the

GBmez weight-for-age classification (1.5) and

the Ariza-Macias height-for-age classification

(I), and (b) the potential for qualitatively dis-

criminating between four nutritional states

( no malnutrition, recent malnutrition,

chronic malnutrition, and previous malnu-

trition) by means of the modified Seoane-

Latham height-for-age and weight-for-height

classification (3). These hypothetical relation-

ships satisfactorily incorporate most of the

basic clinical and epidemiologic data used to

characterize PCM morbidity. Indeed, they

were proposed with the aim of finding a bat-

tery of nutritional indicators that could be

used in epidemiologic surveillance programs.

In sum, the objectives of the project de-

scribed here were as follows:

. to make a comparative study of the prev-

Paulo, and to present the outlines of an

epidemiologic model of PCM in each of those

cities;

l to provide points of reference useful for

estimating the extent and severity of malnu-

trition in other major Brazilian cities; and

l to study indicators of nutritional status

that might be incorporated into epidemiologic

surveillance programs, or that might even be

used as tools for clinical characterization of

malnutrition.

Materials and Methods

The study included 2,929 children (1,006 in

S”ao Luis, 1,169 in Recife, and 754 in SHo

Paulo). The children in the SFio Paulo sample were chosen from 165 separate areas by select- ing two or three families in each area to be in- cluded in the study. In Recife, streets and families in 20 areas were chosen at random; and in SZo Luis, families were chosen at ran- dom from three areas denoted by the Maran-

hZo State Institute of Economic and Social

Research as being representative of that city.

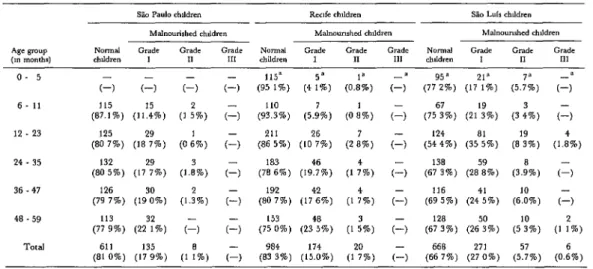

Table 1 shows the composition of the sample

by city and age group.

The nutritional status of the children was

determined by applying the G6mez (15), Ari-

za-Ma&as (l), and modified Seoane-Latham

(3) criteria. The Santo Andre IV scale (24)

was adopted as the standard for determining

anthropometric normality.

Data from some children in the present

study, especially ones in the Recife sample,

were not included in Tables 4 and 5 because these children could not be rated in terms of

the measurements listed in the Brazilian table

of anthropometric standards, and so they

could not be classified. The children involved included some of those O-5 and 12-23 months old in Recife and O-5 months old in Sgo Luis that are listed in Table 1.

Statistical analysis of the results employed a

proportionality test (percentage error dif-

ference), accepting 5 per cent as the critical

value for risk of false rejection of the negative

hypothesis. The study only considered the

Table 1. Children included in the study in SPo Paula, Recife, and SZo Lufs, by age group.

No. of children in each city 4~ BTOUP

(in months) o- 5 6 - 11 12 - 23 24 - 35 36 - 47 48 - 59 Total

Sal Paul0 Recife szo Luh

- 132 127

132 118 89

155 244 228

164 233 205

158 238 167

145 204 190

754 1,169 1,006

prevalence of malnutrition in the total sample

from each city, making no comparisons be-

tween the different age groups.

Results

Height-for-Age

In the SZo Paul0 sample, 5.4 per cent of the children were found to be shorter than -2 S.D.

on the standard table, and were therefore clas-

sified as cases of markedly short stature

(nanism) according to the criteria of Mar-

condes (23). In Recife the percentage of sub-

jects exhibiting nanism was higher (22.6 per

cent), and in Sfo Luis it was higher still (36.1 per cent). The differences between these vari-

ous figures are significant at the 5 per cent

level. As Table 2 shows, the percentage of

Recife and Sgo Luis subjects exhibiting na-

nism was notable even among infants in their first six months of life.

Weight-for-Age

Of the children surveyed in SZo Paulo, 3 1.5

per cent were malnourished according to the

G6mez classification, but only 3.6 per cent

were suffering from grade II or grade III mal-

nutrition. In Recife the respective figures

were 47.3 per cent (total) and 11.5 per cent (grades II and III), and in SIo Luis they were 71.5 per cent (total) and 25.7 per cent (grades

Batista et al. l PCM IN BRAZIL 235

Table 2. Cases of naoism (markedly abort stature) found amang study child ren in the three cities, by age group.

S-do Paul0 Recife sio his

o- 5 - - - - 111 84 1 21 15.9 112 88.2 15 11.8

6. 11 131 99.2 1 0.8 95 80.5 23 19.5 72 80 9 17 19.1

12 23 148 95 5 7 45 192 78.7 52 21 3 133 58 3 95 41 7 24 35 152 92.7 12 7.3 169 72.5 64 27.5 107 52 2 98 47 8 36 - 47 150 94.9 8 5.1 178 74.8 60 25.2 103 61 7 64 38 3 48 - 59 132 91 0 13 90 160 78 4 44 21.6 116 61 1 74 38 9 TCd 713 94.6 41 54 905 77 4 264 22.6 643 63 9 363 36 1

these data appears in Table 3. Again, the dif- ferences between the total percentage of mal-

nourished children in each city sample and

between the percentage in each sample with

grade II or III PCM were statistically signifi-

cant.

Weziht-for-Height

Applying the Ariza-Ma&as weight-for-

height criteria (‘1) as shown in Table 4, 19 per

cent of the children in the S?io Paulo sample

were found to be malnourished, 17.9 per cent

exhibiting grade I malnutrition (10 to 20 per

cent below the normal weight-for-height). The

respective figures for Recife were 16.7 and 15 per cent, and for SLo Luis were 33.3 and 27 per cent. No cases of severe (grade III) mal-

nutrition were found by applying these cri-

teria to subjects in SZo Paul0 or Recife.

Overall, by these criteria SBo Luis appeared to

differ significantly from the other two cities.

Seoane-Latham Classification

According to the Seoane-Latham classifica-

tion, as modified by one of us, the cases where height is adequate for age and weight is ade-

quate for height can be rated “normal”; the

cases where height is adequate for age but

weight is low for height can be rated “recent

malnutrition’ ’ ; the cases where height is low

for age and weight is low for height can be

rated “chronic malnutrition”; and the cases

where height is low for age but weight is ade-

quate for height can be rated “previous

malnutrition. ”

Applying this classification, there appeared

Table 3. Nutritional status of the study children as indicated by the GBmcz weight-for-age classification, by age group, showing the number and percentage (in parentheses) of children in each group within each nutritional category.

6. 11 12 - 23 24 - 35 36 47 48 59

Sll Pado rhddrcn Rcufc Lhlldren sio Luir chrldmn Malnounshed lhlkh” Maln<~“rnhed hldre” Ma,“u”nrhed <h&ire” Nwrd Grack Gradr Cradr NIlrId Grade Cradr Grade NWlll‘d Cradc Grade Grade rhddrcn I II 111 hldre” I II III lhlkk” I II 111

(1) c-1 (1) c-, (66878%) (243:%) (6 k&X) (2 ,“%) (52687%) (33”:%, (lo’:%) (3 9”%)

101

(76 5%) (,s%, (7) (1) (647:%/,) (2S384%) (4 2%) (2 ,“%) (47422%) (32’,‘%, (16’85%) (3 :%) I LO

(71 0%) (25480%) (1 g”%, (1 32%) (5b202%) (368:%) (l,::%) (2:%) (225:%) (39?%) (317:%) (7’:%) 107

(65 2%) (3d:W) (4 :%) c-, 117

(502%) (358:%) (12208%) (2 :w, (22”,‘%, (5:O;w) (22405%) (3 :%) 102

(646%) (32”,‘%, (1 93%) (O;%) (5:,%, (40g:%) (132;%) -

(-) (2Oas%, (5E%) (*4244%) (4:%0/o) (66”,%, (25”:%, (7’j%) (7 (45’:%, (41’:%) (11284%) (1 43%) (234:%) (50905%) (23”:%, (2 65%) TO&Xl 517 210

Table 4. Nutritional status of the study children as indicated by the A&a-Ma&s weight-for-height classification, by age group, ahowing the number and percentage (in parentheses) of child ren in each group within each nutritional category.

Slo Paula chlldm” Rec~fe chlldre” Sk, Luls chlldre” Malnourished chJdre” Malnounshed chddren Malnounshcd ch,,drc” Normal Grade Grade Grade Normal Grade Grade Grade Nomal Grade Grade Grade chlldm” 1 I1 III chiidrr” I II III chddrc” I II III o- 5

c-1 c-1 6- 11

12. 23 (80 7%) 125 (18279%)

(1)

(I :%)

115” (95 1%)

110 (93.3%)

(4 :;, (O.&i)

a a

(77g25%) (u2:%) (75?%) (2lYW)

(5.:;) (3 43%)

a (1, (1)

4

c-1

(1)

c-1

(1)

(1,

(1)

(0 iw, (2 s7%, (5.9%) (0 i%, (86 5%) 211 (10276%)124

(54 4%) (35s:%) (8?% ) (3.98%)

(1.84%)

24 . 35 132

(80 5%) (17279%)

(1.83%)

183(78 6%) (19?%) (1 :w, (I :,, (l,“%) (*270%)

138

(67 3%) (28589%) (1,

(1,

(1 :w,

(O.,“,,

36 .47 (79 7%) 126 (19300%) 48 .59 (77 9%) 113 (223fW)

Total 611 135

(81 0%) (17 9%)

(1.32%)

192 (80 7%)153 (75 0%)

984 (83 3%)

(17462%/.)

116 (69 5%) (244:%)

128 (67 3%) (265:%)

668 271 (66 7%) (27 0%)

(6!,“%)

(5?%) (5?%, (23458%) 174 (15.0%)to be little difference in the rates of recent sated” malnutrition (3.4 per cent in SZo

(short-duration) malnutrition in the samples, Paulo, 5.5 per cent in Recife, and 15 per cent

the rates being 11.2 per cent in Recife, 17.0 in SZo Luis) were also found.

per cent in Go Paulo, and 18.1 per cent in

Go Luis. However, as Table 5 shows, there Discussion

was a marked difference in the rates of chronic

malnutrition observed in %o Paul0 (2.0 per So Paul0

cent) and in Recife and SZo Luis (17 and 2 1

per cent, respectively). Important differences The nutritional status of the study children

between the rates of previous or “compen- in each city conforms closely to predictions of

Table 5. Nutritional statw of the study children aa indicated by the modified Seoane-Latham classification. by age group, showing the number and percentage (in parentheses) of children in each group within each nutritional category.

o- 5

6-11 114

(86 4%)

(1,

t-,

(1,

(1,

(0 l%,

a 4’ (81’89%) (3 3%)

a

(13’26%)

(I:;,

a .I

(6g8:%) (192:%,

a 4a (SIP%) (3 3%) (IO :,, (9 it%) (15386%) (*5599%) (12?%) (75649%) (5 f%, (1 :,, (65528%) (15’74%)

(38868%) (194:%) 12 - 23 122

(78 7%) 24 - 35 125

(76 2%) 36 - 47 121

(76 6%)

(16286%) (2 ,“%, (3 ,“%, (I ,“%,

(1 s”%,

(70 9%) L73d (7’89%) 4 139(59 7%) (12390%) 144

(60 5%) (,4334%) 123 (60 3%) (183:%)

767 130 (66 3%) (II 2%)

(4 :,,

(1844%)

(2046%) (la70%, 197 (17 0%)

(387:%) (Id:%, (427:%) (Id:%, (426:%, (le396%)

460 181 (45 9%) (I8 I %)

(306:%) (16364%) (264:%) (I I’:%) (25*38%) (U276%)

211 150 (21 0%) (15 0%) (3 :,,

(6l90% ) (3’,“%,

TOtal 585

(77 6%)

Batista et al. l PCM IN BRAZIL 237

Berg (9) and Jelliffe (18) stating that applica-

tion of the weight-for-age criteria will show

between one-third and two-thirds of the chil-

dren in the developing world to be malnou-

rished. Nevertheless, a WHO map of PCM’s

worldwide distribution (30) indicates the

states of southern Brazil (including Slo Paulo)

as being areas, in theory, where endemic

PCM is not a public health problem. A previ-

ous paper by one of the authors (3) based on

our Slao Paulo data arrived at conclusions

along the latter lines contradicting those of

Rosenberg (32).

In terms of our study’s findings, although

the G6mez weight-for-age criteria indicated

that nearly a third of the SEo Paul0 children had PCM, only small percentages were found to be suffering from moderate or severe mal-

nutrition (3.2 and 0.4 per cent, respectively).

Since these latter are the forms of PCM asso-

ciated with mortality and sequelae, that find-

ing indicates the problem has less epidem-

iologic significance than would otherwise be

the case. In fact, it suggests that the problem is first and foremost a social one, raising serious

questions about the population’s quality of life

but relegating the immediate public health

risks to a level of secondary importance.

In general, the marked predominance of

mild (grade I) or “recent” malnutrition cases

among those indicated by applying the Ariza-

Macias and Seoane-Latham classifications

supports this conclusion, Basically, what was

found in SZo Paulo was sporadic malnutrition

of short duration, possibly associated with in-

fectious processes that were also sporadic and

probably primary. Thus, a model emerged in

which sequelae occurred only rarely, and in

which only 5.4 per cent of the children sur-

veyed appeared to exhibit nanism according

to the Marcondes criteria (see Table 2). Con-

sidering that the frequency of nanism among

children defined as anthropometrically nor-

mal by the Santo Andre IV standard (24) is

2.5 per cent, this 5.4 per cent prevalence is

low. Overall, the 2.9 per cent difference be-

tween the two figures represents the probable

impact of PCM on the growth pattern of SZo Paul0 children under five years of age.

Before generalizing on the basis of these

conclusions, certain reservations should be

noted. First, the SBo Paulo data cannot be ex-

trapolated to cover all of southern Brazil; for

Monteiro, working in the Ribeira Valley of

SZo Paul0 State, has shown that the PCM pic-

ture is far different from that prevailing in the

city of SZo Paulo (27,28). Second, there is

evidence that malnutrition is becoming more

common among children less than 1 year of

age in the city of SZo Paulo (3,28). This trend, consistent with those reported from other ur- ban centers by various authors (5,7,16,26,34),

points to a health problem that unquestion-

ably merits serious attention.

Comparisons with Recije and So Luis

As already noted, the PCM picture found in Recife and %io Luis differed markedly from that found in SZo Paul0 in terms of both PCM

prevalence and PCM severity. The combined

cases of moderate (grade II) and severe (grade

III) PCM were three times more prevalent in

Recife and seven times more prevalent in SHo

Luis than they were in S?io Paulo-even

though the prevalence of all kinds of malnu-

trition (including grade I) was only 1.5 times

as high in Recife and 2.2 times as high in Slo Luis.

This appears to be a comparative parameter

of critical importance. That is, besides the

overall prevalence of malnutrition being

higher, the higher prevalence of grade II and

grade III PCM denotes the relatively worse

nutritional situations in Recife and SBo Luis.

This is especially true in the case of S&o Lufs,

a city where the distribution of PCM is re-

garded as representative of the PCM situation

in all of northeastern Brazil (6).

In contrast, the Ariza-Macias weight-for-

height classification did not reveal marked dif-

ferences in the patterns of malnutrition pre-

vailing in SZio Paulo, Recife, and SIo Lufs,

the modified Seoane-Latham classification

show such differences. It appears premature

to draw any hard and fast conclusions from

our experience to date, but there are strong

indications that children with deficient weight

for age in the former classification system

could not be expected to exceed 25 per cent of

any given population. In other words, major

variations in frequency would not normally be

expected. These points lead to the important

methodological conclusion that it would be in-

advisable to use the weight-for-height ratio for

purposes of epidemiologic assessment, be-

cause markedly different areas with very di-

verse nutritional situations could appear as

uniform or at least not very different.

However, when the Seoane-Latham clas-

sification is used to separate subjects without

malnutrition or with “recent” malnutrition

from subjects with “chronic” or “previous”

malnutrition, then the epidemiology of the

problem becomes clear. For example, in terms

of the “chronic” and “previous” forms of

malnutrition (i.e., the duration of marked

malnutrition capable of compromising skeletal

growth) Recife and SZo Luis are clearly

distinguished from S”ao Paulo. However, the

weights of many of the children with nanism

show satisfactorily adjusted bodily propor-

tions, which is to say an adequate weight for height, suggesting that these are at least tem-

porarily compensated forms of malnutrition.

Overall, our data indicate that nutritional

nanism arising from “chronic” or “previ-

ous” malnutrition is the most distinctive an-

thropometric feature of the PCM problem in

these two northeastern cities.

The nutritional patterns observed in Recife

and S”ao Luis also differ quantitatively and

qualitatively from each other. Application of

the G6mez and Ariza-Macias classifications

suggest significantly higher incidences of

moderate and severe malnutrition, nanism,

and “previous” malnutrition in %o Luis

than in Recife. Obviously, the PCM problem

is much more serious in SZo Luis. It should be

reiterated, however, that from a methodologic

viewpoint the Ariza-Macias classification does

not show the relevant differences in nutri-

tional status so clearly as the other two

methods.

In general, it appears likely that few large

or small Brazilian cities have a nutritional

situation significantly less favorable than that

found in SHo Luis. But conversely, few cities

would seem likely to possess nutritional situa-

tions much better than those found in SZo Paulo. And, at least so far as major cities are

concerned, it seems likely that the country’s

true urban nutritional profile, in anthropo-

metric terms, falls within the limits indicated by the patterns found in Sgo Paul0 and SBo

Luis. Overall, for purposes of further

analysis, this study demonstrates the impor-

tance of working with complementary evalua-

tion methods-because existing differences in

the nutritional status of different populations

tend to remain hidden if only one measure-

ment technique is applied.

SUMMARY

For the purpose of detecting similarities and dif- scale (24) was adopted as the standard of anthro-

ferences in prevailing patterns of protein-calorie pometric measurement.

malnutrition (PCM), a study was conducted of This procedure revealed notable differences be-

samples of children under 5 years of age in the Bra- tween PCM patterns in the southern industrial

zilian state capitals of Recife, SZo Luis, and SZo metropolis of SHo Paulo and the less developed

Paulo. A total of 2,929 children (1,006 from Szio northeastern cities of Recife and SBo Luis. For one

Luis, 1,169 from Recife, and 754 from S?to Paulo) thing, although 3 1.5 per cent of the S~O Paulo sam-

were included in the study. The G6mez (H), Mar- ple appeared malnourished in terms of weight for

condes (23), Ariza-Macias (l), and modified age (the G6mez classification), only 3.6 per cent ap-

Seoane-Latham (3) classification systems were ap- peared to be suffering from grade II or grade III

Bat&a et al. l PCM IN BRAZIL 239

terns found in Recife and SZo Lufs, where 11.5 per cent and 25.7 per cent, respectively, appeared to show grade II or grade III malnutrition. Evaluation of the samples in terms of height for age (the Mar- condes criteria) yielded similar results. Similar re- sults were also obtained with the moditied Seoane- Latham classification, in terms of relatively greater

percentages of children with “chronic” or “pre-

vious” malnutrition being found in the Recife and Slo Luis samples.

In contrast, the Ariza-Ma&as weight-for-height

classification did not reveal marked differences be-

tween patterns of malnutrition in the three cities.

Though this does not provide a basis for drawing

firm conclusions, the available evidence suggests that this classification system cannot be expected to show marked variations, and that it is not a con- venient type of classification to use for purposes of epidemiologic evaluation of nutritional status.

The study also showed marked differences be- tween the PCM patterns in Recife and S?io Luis, with the situation appearing considerably worse in Sio Luis. Overall, it appears likely that the relative- ly favorable PCM picture in SZo Paulo and the relatively unfavorable one in Slo Luis provide points of reference marking extremes between which the PCM patterns prevailing in nearly all Brazilian cities can be found.

(1) Ariza Macfas, J. MCtodo para la evaluation de1 crecimiento de hombres y mujeres desde el na- cimiento hasta 10s 20 aiios, para uso a nivel na- cional e intemacional. Arc/z Latinoam N&r (Caracas) 22(4):531-546, 1972.

(2) Amhold, R. The arm circumference as a

public health index of protein-calorie malnutrition in early childhood: 27. The QUAC Stick: A field

measure used by the Quaker service team in Ni-

geria. J Trop Pediatr 15(4):243-247, 1969.

(3) Bat&a Filho, M. Preval&ncia e estagios da

desnutri@io pro&co-calbrica em criarqas da cidade

de SHo Paulo. Thesis. School of Public Health, SPo Paulo University, SIo Paulo, 1975, 125 pp.

(4) Beghin, I. The arm circumference as a public health index of protein-calorie malnutrition of early childhood: 18. Assessment of effectiveness of a nu- trition rehabilitation centre at Fond-Parisien, Hai- ti. J Trap Pediatr 15(4):248-250, 1969.

(5) Beghin, I. Desnutricio prottico-calorica:

Considera@es sobre sua epidemiologia. Rev&a Bra-

sileira de Medicina (Rio de Janeiro) 29(6):278-283, 1973.

(6) Beghin, I. Improvement of the nutritional status of infants and children: Considerations of

Northeast Brazil programs. In Proceedings, Western

Hemisphere Nutrition Congress III (Miami Beach, 1971). Futura, New York, 1972, pp. 93-98.

(7) BChar, M. La desnutricion coma problema de

medicina social. Archives de1 Cole&o Medico de El Sal-

vador 25(2):96-103, 1972.

(8) Bennett, F. J. The arm circumference as a public health index of protein-calorie malnutrition of early childhood: 15. A rapid screening test in

emergency child feeding in Kivu, Congo. J Trop

Pediatr 15(4):238-240, 1969.

(9) Berg, A. The Nutrition Factor: Its Role in Na-

tional Development. The Brookings Institute, Wash- ington, D.C., 1973, 290 pp.

(10) Blankhart, D. M. The arm circumference as

a public health index of protein-calorie malnu-

trition of early childhood: 8. Experience in Sierra

Leone and Zambia. J Trap Pediatr 15(4):205-208,

1969.

(11) Coelho, H. A. L. Estado nutritional e con- di@es socio-econ8micas. Thesis. Universidade Fe- deral de Pernambuco, Instituto de NutricIo, 1975, 51 PP.

(12) Cook, R. The arm circumference as a public health index of protein-calorie malnutrition of early childhood: 6. The arm circumference in a field sur-

vey in Ankole, Uganda. J Trap Pediatr 15(4):198-

200, 1969.

(13) Davis, L. E. Epidemiology of famine in the Nigerian crisis: rapid evaluation of malnutrition by height and arm circumference in large populations.

Am J Clin Nutr 24(3):358-364, 1971.

(14) El Lozy, M. The arm circumference as a public health index of protein-calorie malnutrition of early childhood: 3. A modification of Wolanski’s

standards for the arm circumference. J Trap Pediatr

15(4): 193-194, 1969.

(15) Gomez, F. Desnutricion. Bol Med Hasp Infant

Mex 3(4):543-551, 1946.

(16) Gurney, J. M. The arm circumference as a public health index of protein-calorie malnutrition of early childhood: 16. Rapid assessment in a ref-

ugee camp in Nigeria. J Trop Pediatr 15(4):241-242,

1969.

(17) Jelliffe, D. B. The Assessment of the Nutritional Status of the Communiv. WHO Monograph Series,

No. 53. World Health Organization, Geneva,

1968, 291 pp.

tion programs for pre-school children. Am J Clin

Nutr 25(6):595-605, 1972.

(19) Kanawati, A. A., N. Haddad, and D. S.

McLaren. The arm circumference as a public

health index of protein-calorie malnutrition of early

childhood: 14. Preliminary results with mid-arm

and muscle mid-arm circumferences used as nu- tritional screening procedures for pre-school chil-

dren in Lebanon. J Trap Pediatr 15(4):233-237,

1969.

(20) Kanawati, A. A., and D. S. McLaren. As-

sessment of marginal malnutrition. Nature 228:573-

575, 1970.

(21) Lucena, M. A. F. Estudo antropom&trico de criancas de la 60 meses em duas cidades do Nor- deste brasileiro: Recife (PE) e SZo Luis (MA).

Thesis. Universidade Federal de Pernambuco,

Instituto de Nutriclao, Recife, 1975.

(22) Luna-Jaspe, G., H.; J. Ariza-Macias; R.

Rueda-Williamson; J. 0. Mora Parra; and F. Par- do-TCllez. Estudio sectional de crecimiento, desa- rrollo y nutrition en 12.138 niiios de Bogota, Co- lombia: II. El crecimiento de niiios de dos clases socioeconbmicas durante sus primeros seis anos de

vida. Arch Latinoam Nutr 20(2):151-165, 1970.

(23) Marcondes, E. Nanismo por detici&ncia

nutritional. Jomal de Pediatria (Rio de Janeiro) 39

(3-4):58-64, 1974.

(24) Marques, R. M., E. Berquo, J. Yunes, and E. Marcondes. Crescimento de criancas brasileiras: Peso e altura Segundo idade e sexo; influ&ncia de

fatores socio-econ6micos. Anais Nestle (Slao Paulo)

84(Suppl. 2):22, 1974.

(25) McKay, D. A. The arm circumference as a public health index of protein-calorie malnutrition of early childhood: 10. Experience with the mid- arm circumference as a nutritional indicator in field

surveys in Malaysia. J Tro,b Pediatr 15(4):213-216,

1969.

(26) Monckberg, F. Factors conditioning mal- nutrition in Latin America, with Special Reference

to Chile: Advice for a Volunteer Action. In P.

Gyorgi and 0. L. Kline. Malnutrition Is a Problem of

Ecology. Karger Basel, New York, 1970.

(27) Monteiro, C. A. Epidemiologia da desnu- tri5Z-o prot&co-calbrica em nucleos rurais do vale do Ribeira. Thesis. School of Public Health, SZo Paulo University, Sio Paulo, 1977, 84 pp.

(28) Monteiro, C. A., and M. F. Rta. A classi-

tica+ antropomCtrica coma instrument0 de inves-

tiga@o epidemiblogica da desnutri@o proteico-

calorica. Rev Saline Ptiblica (Slo Paulo) 11(3):353-

361, 1977.

(29) Nelson, W. E., V. C. Waugham III, and R. J. McKay.Textbook of Pediatrics. W. B. Saunders,

Philadelphia, 1969, pp.42-43.

(30) Organization de las Naciones Unidas para

la Agricultura y la Alimentacidn, Grupo Asesor de

Proteinas. Vidas en peligro: Las proteinas y los niiios.

Rome, 1970, 132 pp.

(31) Puffer, R. R., and C. V. Serrano. Patterns of

Mortality in Childhood: Report of the Inter-Awican In- vestigation of Mortali in Childhood. PAHO Scientific Publication 262, Pan American Health Organiza- tion, Washington, D.C., 1973, 490 pp.

(32) Rosenberg, 0. Observa$es sobre dados re- lativos ao estado de nutricZo de criancas entre 0 e 4 anos de idade, no municfpio de SIo Paulo. Thesis. School of Public Health, SSro Paul0 University, SIo Paulo, 1970.

(33) Waterlow, J. C. Note on the assessment and

classification of protein-energy malnutrition in

children. Lancet 2(7819):87-89, 1973.

(34) Waterlow, J. C., and G. A. 0. Alleyne. Ma’

nutri>Zo prot&o-calorica em crianps: evoltqdo dos conhe- cimentos nos liltimos 10 anos. Nestle, SBo Paulo, 1974,

120 pp.

(35) World Health Organization. Joint FAO/

WHO Expert Committee on Nutrition: Eighth Report.