www.jped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Child

development

in

primary

care:

a

surveillance

proposal

夽

,

夽夽

Renato

Coelho

∗,

José

Paulo

Ferreira,

Ricardo

Sukiennik,

Ricardo

Halpern

SantaCasadePortoAlegre,HospitaldaCrianc¸aSantoAntônio(HCSA),AmbulatóriodeDesenvolvimentoInfantil, PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil

Received25June2015;accepted15December2015 Availableonline26May2016

KEYWORDS Childdevelopment; Screening;

Riskfactors

Abstract

Objective: Toevaluateachilddevelopmentsurveillancetoolproposaltobeusedinprimary care,withsimultaneoususeoftheDenverIIscale.

Methods: Thiswasacross-sectionalstudyof282infantsagedupto36months,enrolledina publicdaycareinacountrysidecommunityinRioGrandedoSul/Brazil.Childdevelopmentwas assessedusingthesurveillancetoolandtheDenverIIscale.

Results: Theprevalenceofprobabledevelopmentaldelaywas53%;mostofthesecaseswerein thealertgroupand24%hadnormaldevelopment,butwithriskfactors.AttheDenverscale,the prevalenceofsuspecteddevelopmentaldelaywas32%.Whenriskfactorsandsociodemographic variableswereassessed,nosignificantdifferencewasobserved.

Conclusion: Theevaluationofthissurveillancetoolresultedinobjectiveandcomparabledata, whichwereadequateforascreeningtest.Itiseasilyapplicableasascreeningtool,eventhough itwasoriginallydesignedasasurveillancetool.Theinclusionofriskfactorstothescoringsystem isaninnovationthatallowsfortheidentificationofchildrenwithsuspecteddelayinaddition todevelopmentalmilestones,although thedefinitionofparametersandchoiceofindicators shouldbethoroughlystudied.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/ 4.0/).

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:CoelhoR,FerreiraJP,SukiennikR,HalpernR.Childdevelopmentinprimarycare:asurveillanceproposal.J Pediatr(RioJ).2016;92:505---11.

夽夽

StudyconductedatthePost-GraduatePrograminHealthSciences,UniversidadeFederaldeCiênciasdaSaúdedePortoAlegre(UFCSPA); andChildDevelopmentOutpatientClinic,HospitaldaCrianc¸aSantoAntônio(HCSA),SantaCasadePortoAlegre,RS,Brazil.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:rencoel@gmail.com(R.Coelho).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2015.12.006

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Desenvolvimento infantil;

Triagem; Fatoresderisco

Desenvolvimentoinfantilematenc¸ãoprimária:umapropostadevigilância

Resumo

Objetivo: Avaliar uma propostade um instrumento de vigilância em desenvolvimento para utilizac¸ãonaatenc¸ãoprimária,eaaplicac¸ãosimultâneadaescaladeDenverII.

Métodos: estudotransversalcomumaamostrade282crianc¸asaté36mesesdaredepública escolar,numacomunidadedoRS.Foiavaliadoodesenvolvimentoinfantilutilizandoo instru-mentodevigilânciapropostoeoDenverII.

Resultados: AprevalênciadeProvávelAtrasonoDesenvolvimentofoide53%,sendoamaioria dessesnacondic¸ãodeAlertae24%comdesenvolvimentonormal,mascomfatoresderisco.No Denveraprevalênciafoide32%comsuspeitaparaoatrasonodesenvolvimento.Osfatoresde riscoeasvariáveissócio-demográficasavaliadasnãoapresentaramdiferenc¸assignificativas.

Conclusão: Aavaliac¸ãodesteinstrumentodevigilânciatrouxedadosobjetivosecomparativos, nosmoldespreconizadosparaumtestedetriagem.Éuminstrumentodefácilaplicabilidade comotriagem,sendooriginalmentecomovigilância.Ainclusãodosfatoresderisconosistema deescoreéumainovac¸ãoquepossibilitaoaumentodaidentificac¸ãodecrianc¸ascomsuspeita deatrasoalémdosmarcosdodesenvolvimento,aindaqueadefinic¸ãodosparâmetroseescolha dosindicadoresdevasermelhorconstruída.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigo OpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4. 0/).

Introduction

Child development is a continuous and dynamic process that promotes changes in several areas: physical, social, emotional,andcognitive,in acomplexinteractionamong thesechangesandtheenvironmentwhereeachstageis con-structed,basedontheprevioussteps.1,2Developmentmust

be understood within the eco-bio-developmental model, which expands from biology and the environment to a broaderconcept,includingepigeneticsandneuroscience.1,3

Severalstudieshaveshowndifferentprevalenceratesof delay accordingto theevaluation methodand agegroup, reachingupto18%.4---8Instudiesusingonlyscreeningtests,

theprevalencewashigher,showinggreatvariation.4,9,10

The early detection of children with possible develop-mentaldelaysisoneoftheobjectivesofroutinepediatric consultations.5Itiswidelyestablishedintheliteraturethat

thecost of the evaluationand early intervention in child developmentisupto100timeslowerthanthatoftreating achildwithalatediagnosis.11

Recent studies show that investments in the first four yearsoflifehaveapositiveannualrateofreturn,whereas some late recovery programs show null and often nega-tivereturns.12---14 Surveillanceis acontinuous processthat

occursduringconsultationsandallowsfortheearly detec-tionof developmental problems,7 while screening is part

of this process and characterized by being usually dis-crete and using a standardized tool. The systematic use ofsurveillanceandscreeningiscriticalforpediatriciansto identifypotential risk factors and/or delaysand promote interventions.5,7,11,15,16

TheAmericanAcademyofPediatricsrecommends apply-ingascreeningtoolinthefirstthreeyearsoflife,evenin theabsenceofriskfactors,toincreasetheabilitytoidentify possibledelays,11,15,17 as, in theabsenceof asurveillance

process,only30%ofthechildrenwillbedetectedashaving delaysbeforetheyreachschoolage.11Recentstudieshave

shownanincreaseintheuseoftoolstoassessdevelopment, but theyare stillunfrequently usedin pediatric services, whetherpublicorprivate.7,17,18

Sometoolsareself-administeredquestionnaires,others aretobeusedbyprofessionals insearchfor developmen-tal information, andothers that assess the main areas of development.7,11,17 The limitations of screening tests are

inherent to the tool and age range. Although there are several tools, there is not a unique tool that is univer-sallyusedforallpopulations.8,19 Historically,theDenverII

DevelopmentalScreeningTesthasbeenthemostoftenused screeningtoolworldwide,especiallyinBrazil,asthereisno toolforthatpurpose.Inadditiontobeingeasyandquickto apply,thetoolvalidityhasbeenestablishedbytheaccuracy obtainedinthedifferentpercentilesinwhicheachtaskwas establishedforeachassessedage.

Aswiththeother screeningtools, theDenverII hasno hypothesis construct, such asfor instance an intelligence test,itdefinestheageatwhichachildperformsacertain task.Although ithas borderline sensitivity and specificity rates,itcontinuestobeusedincomparisonstudies.6,7,9,10

The use of a tool for child development surveillance begantobeimplementedbytheBrazilianMinistryofHealth (MOH)in2002.20 TheIntegratedManagementofChildhood

Illness(IMCI)program,developedbytheWorldHealth Orga-nization (WHO)andbytheUnitedNationsChildren’s Fund (UNICEF),servedasthebasisforuseinchilddevelopment surveillance.Subsequently,amanualwaspublishedforthis purposeandadevelopmentsurveillancetablewasadapted andhasbeenusedintheChildHealthHandbookoftheMOH21

The aim of this study wasto evaluate a newproposal for a child development surveillance model that can be appliedasascreeningtoolatcertainpointsofchild devel-opmenttogetherwiththeDenverIItest,identifyingpossible associationsbetweensociodemographicvariables(income, parentallevelofschooling,numberofsiblings)andpossible developmentaldelays.

Methods

Across-sectionalstudywascarriedoutwithaschool-based sample,havingasinclusioncriteriaallchildren aged0---36 monthsofageattendingpublicpre-schools ofthetownof Igrejinha,stateofRioGrandedoSul,Brazil.Theexclusion criteriacomprisedallchildrenenrolledthroughtheschool inclusionprogramorwithadiagnosisofanydevelopmental problems.

Consideringaconservativeprevalenceof10%for devel-opmentaldelaysandpower of80%,withanalphaerrorof 5%,itwouldbenecessarytoassess350children.Atthetime, 357childrenfrompublicschoolsmettheinclusioncriteria; therefore,allwereinvitedtoparticipate.

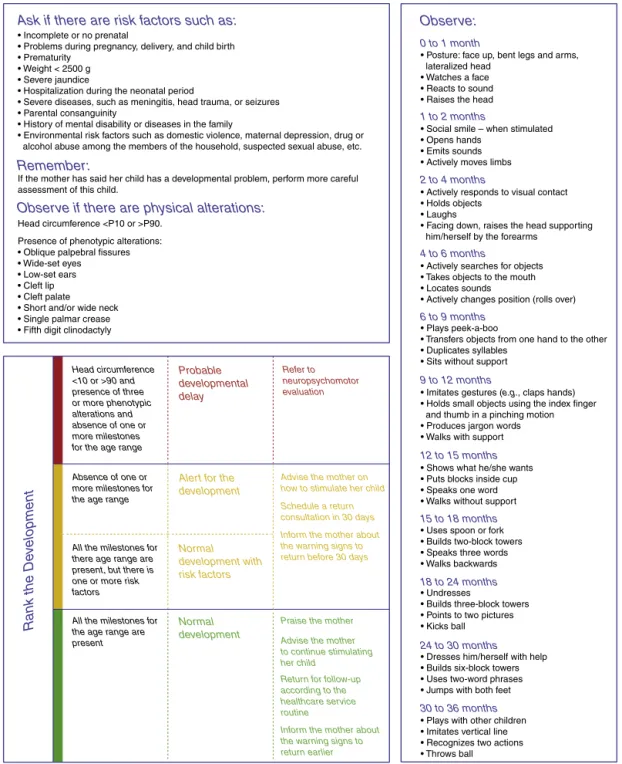

The adapted tool, here termed Surveillance Algorithm (SA),wasderivedfromthedevelopmentalsurveillancetool that has been used by the MOH in the primarycare net-work, published in theChild Health Handbook and in the manualpublishedbyFigueiras.2Theproposedmodification

wasrelatedtothedevelopmentalassessmentcriterionfor ‘‘probable delay’’, which usedthe absenceof milestones forthecurrentagerangeandnottheprevious range.The assessed milestones correspond to the skills that 90/100 childrenperformatthisagerange.Accordingtothemanual, childrenaged0---36monthsweredividedintoagesubgroups inmonths.Riskfactorsandphenotypicsignsofgenetic dis-orders were investigated, which are described in Table 1

andFig. 1,aswell ashead circumference (HC)and mile-stones corresponding to gross and fine motor skills, and personal---socialandlanguageareas.

The score of thistooluses thefollowing classification: normal development, alert (with two subgroups: normal withrisk factors, andabsence of oneor moremilestones for the age range), and probable delay in child develop-ment (which includes altered HCand phenotypic changes

andtheabsenceofoneormoremilestonesfortheagerange;

Fig.1).

Thesocio-demographicvariablesgender,age,and num-ber of siblings were analyzed using central tendency and dispersionmeasures.Parentallevelofschoolingandfamily incomewerestratifiedinto groups andshown asabsolute andrelativefrequencies.RiskfactorsandHCwereanalyzed dichotomously,whereHCwasconsideredtobealteredwhen itwas>90thand<10thpercentile,usingthecurves devel-oped by the National Center for Health Statistics of the CenterforDiseaseControl(CDC),UnitedStates,in2000.

The Denver II is a screening tool for child develop-ment that evaluates children aged 0---6 years old and includes items from the gross and fine-adaptive motor, social---personalandlanguageareas.Thepossibleoutcomes were normal (absence of failures or just one alert), sus-pecteddelay(twoormorealerts,oroneormorefailure), andnon-testable(refusaltoperformthetesting).23,24

Invitationlettersweresent totheparentsand, accord-ingtoinitial acceptance,and informedconsentform was signed.

TheSAwasappliedtoallchildren,followedbytheDenver TestII.Allpretermchildrenhadtheiragecorrecteduntilthe ageof2yearsfortheapplicationofbothtestswere, accord-ingtothe criteriaof theDenverII manual,considering as termpregnancy those of 38 weeksor more;for pregnan-ciesbelow38weeks,thecorrectionuses40weeksforthe calculation.23

Forqualitycontrolpurposes,thetoolswereappliedby differentexaminersforeachtest,whowereblindedtothe previous testing results. To minimize the learning effect, whenperformingthesametestsattwoconsecutivetimes, theorderofapplicationwasreversedinthesecondhalfof thesample.

The trainingphasewascarriedoutwiththetwotools; thisphasewasfilmedforimprovementandstandardization ofHCmeasurement(measuringtapearoundthefrontaland occipitalbone)amongthefourexaminers.Apilotstudywas performedwithchildrenofthesameageandwhowerenot partof the sample, showing at the end a90% agreement betweentheexaminers.

Bydrawinglots,5%oftheinterviewswererepeatedby the coordinator toensure the reliability of the collected data.

Table1 PercentageofdelaysintheSAaccordingtotheriskfactors.

Assessedriskfactorsa Altereddevelopmental

milestones(%)

Normaldevelopmental

milestones(%)

Total(%)

Absenceofprenatalcare 1(0.35) 2(0.7) 3(1)

Problemsduringpregnancy 12(4.2) 20(7) 32(11)

Deliveryproblems 3(1) 9(3.1) 12(4.2)

Pretermbirth 7(2.5) 10(3.5) 17(6)

Lowbirthweight 5(1.7) 5(1.7) 10(3.5)

Severeneonataljaundice 3(1) 11(3.9) 14(4.9)

Neonatalhospitalization 11(3.9) 14(4.9) 25(8.8)

Severediseases 7(2.5) 3(1) 10(3.5)

Mentaldisabilityorillnessinthefamily 12(4.2) 15(5.3) 27(9.5)

Environmentalriskfactors 18(6.3) 29(10.2) 47(16.6)

SA,surveillancealgorithm.

Child Development Surveillance Tool

Assess the child's development from 12 to 36 months of age

Ask if there are risk factors such as: Observe:

0 to 1 month

1 to 2 months

2 to 4 months

4 to 6 months

6 to 9 months

9 to 12 months

12 to 15 months

15 to 18 months

18 to 24 months

24 to 30 months

30 to 36 months

Remember:

Observe if there are physical alterations:

Rank the De

velopment

• Incomplete or no prenatal

• Problems during pregnancy, delivery, and child birth • Prematurity

• Weight < 2500 g • Severe jaundice

• Hospitalization during the neonatal period

• Severe diseases, such as meningitis, head trauma, or seizures • Parental consanguinity

• History of mental disability or diseases in the family

• Environmental risk factors such as domestic violence, maternal depression, drug or alcohol abuse among the members of the household, suspected sexual abuse, etc.

• Posture: face up, bent legs and arms, lateralized head

• Watches a face • Reacts to sound • Raises the head

• Social smile – when stimulated • Opens hands

• Emits sounds • Actively moves limbs

• Actively responds to visual contact • Holds objects

• Laughs

• Facing down, raises the head supporting him/herself by the forearms

• Actively searches for objects • Takes objects to the mouth • Locates sounds

• Actively changes position (rolls over)

• Plays peek-a-boo

• Transfers objects from one hand to the other • Duplicates syllables

• Sits without support

• Imitates gestures (e.g., claps hands) • Holds small objects using the index finger and thumb in a pinching motion • Produces jargon words • Walks with support

• Shows what he/she wants • Puts blocks inside cup • Speaks one word • Walks without support

• Uses spoon or fork • Builds two-block towers • Speaks three words • Walks backwards

• Undresses

• Builds three-block towers • Points to two pictures • Kicks ball

• Dresses him/herself with help • Builds six-block towers • Uses two-word phrases • Jumps with both feet

• Plays with other children • Imitates vertical line • Recognizes two actions • Throws ball • Oblique palpebral fissures

• Wide-set eyes • Low-set ears • Cleft lip • Cleft palate • Short and/or wide neck • Single palmar crease • Fifth digit clinodactyly

If the mother has said her child has a developmental problem, perform more careful assessment of this child.

Head circumference <P10 or >P90. Presence of phenotypic alterations:

(whenever there is no severe classification that requires referring the case to the hospital)

Head circumference <10 or >90 and presence of three or more phenotypic alterations and absence of one or more milestones for the age range

Absence of one or more milestones for the age range

All the milestones for there age range are present, but there is one or more risk factors

All the milestones for the age range are present

Probable developmental delay

Alert for the development

Advise the mother on how to stimulate her child

Schedule a return consultation in 30 days

Inform the mother about the warning signs to return before 30 days

Praise the mother Advise the mother to continue stimulating her child

Return for follow-up according to the healthcare service routine

Inform the mother about the warning signs to return earlier Normal development with risk factors Normal development Refer to neuropsychomotor evaluation

Figure1 Surveillancealgorithm.

Thedataweretypedinduplicateinthedatabaseto iden-tifypossiblediscrepanciesintheentereddata.

ThestudywasevaluatedandapprovedbytheResearch EthicsCommittee of Universidade Federal de Ciências da SaúdedePortoAlegre(OpinionNo.332.335/2013).

Atthecomparativeassessment,DenverIIwasusedasa referencetoestimatesensitivity,specificity,positive(PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV), and accuracy. The chi-squared test wasusedto verifya possible association

between sociodemographicvariables for the differencein proportions,witha5%significancelevel.

StatisticalanalyseswereperformedusingSPSS(SPSSfor Windows,Version10.0.USA).25

Results

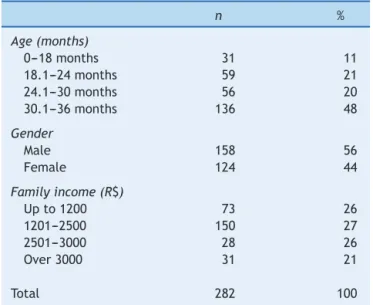

Table2 Samplecharacteristics.

n %

Age(months)

0---18months 31 11

18.1---24months 59 21

24.1---30months 56 20

30.1---36months 136 48

Gender

Male 158 56

Female 124 44

Familyincome(R$)

Upto1200 73 26

1201---2500 150 27

2501---3000 28 26

Over3000 31 21

Total 282 100

Meanage=28months.

48 cases,there wasnoresponse tothe invitation to par-ticipateinthestudy,16childrenleftthepreschoolatthat period,and 11 cases refused toreturn for retesting. The meanageofthesamplewas28months,136(48%)ofwhom wereagedbetween 30and36 months,with56%of males (Table2).

Twenty-sevenchildrenincluded inthestudy completed 36monthsofageduringthestudy.Aseparateanalysiswas performedwiththesechildren;asnostatisticallysignificant differencesregarding toolpropertieswere observed,they remainedinthestudy.

AttheSAassessment,alittleoverhalfofthesamplehad aresultindicatingprobabledelay,withmostofthoseinthe alertcondition,and68cases(24%)wereclassifiedasnormal developmentwithriskfactors(Table3).Regardingthe Den-ver test, 91cases (32%)showed suspecteddevelopmental delay.

Whenexploringthepossibilitiesofcomparisonbetween thetwotoolsregardingsensitivity,theSAshoweddifferent resultsaccordingtothethreeproposedcategories:probable delay(70%),alert(57%),andnormaldevelopmentwithrisk factors(21%;Table 3),withaspecificityof 56%,70%, and 74%,respectively.

Forprobabledelay,PPVwas42%andNPVwas79%;for alert,PPVwas47%andNPVwas77%.

Whenassessingtheriskfactors,therewerenosignificant statisticaldifferencesassociatedwithabsenceof develop-mentalmilestones(Table1).

Regarding the phenotypic alterations assessed in the SA, the frequencies found were very low or nonexistent; regardingalteredHC,almostallcaseswerehigherthanthe 90thpercentile.

Discussion

Inthissample,theprevalenceofsuspecteddelayintheSA was53%forprobabledelayand39%foralert,witha signif-icantdifferenceduetothepresence ofaltered HCinthe probabledelaygroup.

Originally,the surveillance toolusedthe milestones of thepreviousage rangeasthescorecriterionfor probable delay, while the alert score uses the current age range. Inthisstudy,theauthorschosetoperformtheassessment usingthe milestones of theexpected agerange for both, because,usingthemilestonesofthepreviousagerangeand consideringwhathasbeendiscussedaboutthecutoffpoint, thedelaywouldhavealreadybeenevident.7,18

AttheDenverIItest,theprevalencewas32%ofsuspected delay,consistent withother studies, although with varia-tionsintheprevalenceduetothescoringmethodusedand culturaldifferences.4,9,10

The presenceofphysical alterationsandrisk factorsin thescoringcriteriaofthissurveillancetoolisapeculiarityin relationtoothertoolsfoundinliterature,7,11,14,17,18butsome

ofthemshouldbereviewed,despitenotbeingsignificantin thissample.

The physicalalterationregardingHCalone, asthetool was originally proposed, already determines a probable delayintheSA;HCabovethe90thpercentilewasprevalent (93%)amongthosewithalteredHC.Thiswasprobablydue toageneticfactorofmacrocephalyandtallstaturewithout associatedcranialpathology,causinganincreasein sensitiv-ityanddecreasingthePPV.26Itmayberelatedtotheethnic

characteristicsand,additionally,itcouldbeexplainedbya sample fluctuation. Daymont26 concluded thatthe HChas

lowsensitivityandPPVforthediagnosisof macrocephaly-associatedpathologies.

Lowbirthweight,oftenassociatedwithdevelopmental delays,2,6,9,27,28 waslittleprevalentandshowedno

statisti-calassociation inthe sample. Onepossible explanationis the2500gcutoffusedin theSA, whichreducesthe speci-ficitybyaddinglatepreterminfantswithadequateweight forgestationalage(GA).9,28Achangeintheweightand

pro-portionalitycriteriaof thenewbornmight bemore useful fortheriskfactordefinition.28

Regardingprematurity,therearedifferenceswhenGAis below 32 weeks, when comparedto lateand moderately preterm infants,29 even with correction for GA. Perhaps

Table3 Testpropertiesaccordingtotheproposedcategories---%.

P S Sp PPV NPV A

Probabledelay(absentmilestones+alteredHC+phenotypicalterations) 53 70 56 42 79 60

Alert(absentmilestonesonly) 39 57 70 47 77 66

Normaldevelopmentwithriskfactors(presentmilestoneswithriskfactors) 24 --- --- --- ---

---Groupedalert(groupingriskfactors+absentmilestones) 63 78 45 40 80 55

it would be better to assess the nutritional status and weight/length proportionality at birth, which can offer more discriminative parameters regarding developmental delays.9Theuseofinformationaboutjaundiceinthe

neona-tal periodis veryvague anddifficult tointerpret, asit is basedsolelyonsubjectiveinformation.

Inrelationtomaternaldepression,itisawell-established risk factor in the literature30 and potentially modifiable,

whenan earlyinterventionisperformed.Usingastandard toolforitsdetectionisrequired,inadditiontothe informa-tiononpsychotherapyand/ordrugtreatment.15

ThesimultaneoususeoftheDenverscaleallowedforan inevitablecomparisonbetweenthetwotools,evenwiththe limitations regarding the absenceof a gold standard and theepidemiological exercisewith ascreening toolthat is alreadywellestablishedworldwideandasurveillancetool thatprovidesobjectivemeasures.Thesensitivityobtained withthetestedtoolincomparisonwithDenverIIwas70%in theprobabledelaygroupand57%inthealertgroup,whereas thespecificitywas56% and70%, respectively.Considering theseproperties,thesensitivityfortheprobabledelaygroup isacceptable.Regarding thealertgroup,theresultswere theopposite.

Onepossibleexplanationfortheseresultsmayberelated tothecriteriausedforgroupclassification,asalthoughit didnotrepresentanassociatedpathology,theHCabovethe 90thpercentilewasconsideredasariskfactor.7,18

Similarly, in the alert group, the sensitivity may be relatedtothedistributionofageranges.Thefactthatsome childrenwereattheinitialageoftherangeandthe neces-sity touse a proposed cutoffof the 90thpercentile may have caused adifferential misclassification,by classifying childrenwithtypicaldevelopmentashavingdevelopmental delay.

RegardingthePPVobtainedinSA,theresultswere42% and47%for probabledelay andalert,respectively, mean-ingthatapproximatelyhalfofthecasesofsuspecteddelay willnotbeconfirmedinsubsequentevaluations.Conversely, theNPVof79% and77%for theprobable delayandalert, respectively,makesthetoolmoreeffectivewhentheresult isnegative.

Duringtheanalysis,toexplorethepotentialsoftheSA, thesubjectsfromthealertgroupweregroupedby associ-atingriskfactors.Thus,thisnewcategoryhadissensitivity increasedtonearly80%,which isdesirable in ascreening tool(Table3).

This study had limitations regarding its sample, which hasthecharacteristicsofatowninthesouthernregionof Braziland,thus,doesnottranslatetheepidemiological pro-file of theBrazilian population. Although the entire child populationenrolledinthetown’spreschoolswasassessed, thelossesmayalsohaveaffectedtheresults.

Assessing child development is a complex task that requirescontinuedsurveillanceintheearlyyearsoflifeand knowledgeofchilddevelopmentnormality.Althoughthere areseveralscreeningtools,thereisnotauniquetoolthat canbeusedforallagegroups.Additionally,thebesttools stillhave a significant number of false positives, approx-imately 25%, and do not indicate those children situated between1 and2 standard deviations asbeingstillat risk forpossibledelays.7,8Becauseoflimitationsregardingthe

choiceofacomparisonstandard,duetothelackofatool

withBrazilian standards,itwasdecidedtousetheDenver IIscreeningtest,whichhasbeenadaptedandusedin sev-eralothernationalstudiesonchilddevelopmentandisstill widelyusedinothercountries.6,9,10,28

Obviously,themisidentificationofadevelopmentaldelay may cause a consequent increase in costs of specialized assessments andsupplementary tests,in additionto fam-ily anxiety.However,inthereverse situation,the timeof theinterventioncanbemissedandthecostswillincrease, astreatmentswillbelongerandperhapspermanent.12,13

A recent study raises this question and reinforces the need forsystematicmonitoring,assessment ofriskfactors andofparentalperceptionforsuspicionofpossible develop-mentalandbehavioralproblemsassufficienttodirectthem todiagnostictesting.8

SA is easy to learn and to apply, allowing healthcare teams andthefamilytotake anactiverolein child mon-itoring.Thepresenceofriskfactorsinthescoringsystemis aninnovationthatprovidedincreasedsensitivityofthetool, eventhoughthedefinitionofparametersandthechoiceof thebestindicatorsshouldbethoroughlystudied.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

TheauthorsthanktheinternsLaisDuarte,JulianaFritsch, FabianaAdams,andMaianeBraunfortheirdedicationand competence in the field work. Also, they would like to thankallchildren,parents,andteachersofpre-schools in Igrejinha-RS,whosincerelycooperatedwiththisresearch.

References

1.HalpernR.ManualdePediatriadoDesenvolvimentoe Compor-tamento.1sted.SãoPaulo:Manole;2015.

2.FigueirasAC,SouzaIC,RiosVG,BenguiguiY.Manualpara vig-ilânciadodesenvolvimentoinfantilnocontextodaAIDPI;2015. Available from: http://www.bvsde.paho.org/bvsacd/cd61/ vigilancia.pdf[cited25.06.15].

3.BronfenbrennerU,MorrisPA.Thebioecologicalmodelofhuman development.HandbChildPsychol.2006.

4.GlascoeFP,ByrneKE,AshfordLG,JohnsonKL,ChangB, Strick-landB.AccuracyoftheDenver-IIindevelopmentalscreening. Pediatrics.1992;89:1221---5.

5.KingTM,GlascoeFP.Developmentalsurveillanceofinfantsand young childrenin pediatric primary care. CurrOpin Pediatr. 2003;15:624---9.

6.NairMK,KrishnanR,HarikumaranNairGS,GeorgeB,Bhaskaran D,LeenaML,etal.CDCKerala3:at-riskbabyclinicserviceusing differentscreeningtools---outcomeat12monthsusing devel-opmentalassessmentscaleforIndianinfants.IndianJPediatr. 2014;81:1---5.

7.MarksKP,LaRosaAC.Understandingdevelopmental-behavioral screeningmeasures.PediatrRev.2012;33:448---57.

8.UrkinJ,Bar-DavidY,PorterB.Shouldweconsideralternatives to universal well-child behavioral-developmental screening? FrontPediatr.2015;3:21.

10.BritoCM.Desenvolvimentoneuropsicomotor:otestedeDenver na triagem dos atrasos cognitivos e neuromotores de pré-escolares.CadSaudePublica.2011;27:1403---14.

11.GlascoeFP.Screeningfordevelopmentalandbehavioral prob-lems.MentRetardDevDisabilResRev.2005;11:173---9.

12.AraújoA.Aprendizageminfantil:umaabordagemda neurociên-cia,economiaepsicologiacognitiva.RiodeJaneiro:Academia BrasileiradeCiências;2011.

13.CunhaF,HeckmanJJ.Investinginouryoungpeople.Cambridge, MA:NationalBureauofEconomicResearch;2010.

14.Young ME, Richardson LM. Early child development from measurementtoaction:apriorityforgrowthandequity. Wash-ington,DC:WorldBank;2007.

15.Marks KP, Page Glascoe F, Macias MM. Enhancing the algo-rithmfordevelopmental-behavioralsurveillanceandscreening inchildren0to5years.ClinPediatr(Phila).2011;50:853---68.

16.DworkinPH.Detectionofbehavioral,developmental,and psy-chosocialproblemsinpediatricprimarycarepractice.CurrOpin Pediatr.1993;5:531---6.

17.CouncilonChildrenWithDisabilities,SectiononDevelopmental BehavioralPediatrics,BrightFuturesSteeringCommittee, Medi-calHomeInitiativesfor Children WithSpecialNeeds Project Advisory Committee. Identifying infants and young children withdevelopmentaldisordersinthemedical home:an algo-rithmfordevelopmentalsurveillanceandscreening.Pediatrics. 2006;118:405---20.

18.ZepponeSC,VolponLC.Monitoringofchilddevelopmentheld inBrazil.RevPauliPediatr.2012;30:594---9.

19.McLean ME, Wolery M, Bailey DB. Assessing infants and preschoolerswithspecialneeds.UpperSaddleRiver,NJ:Merrill; 2004.

20.CoitinhoDC,BrandtJAC, AlbuquerqueZP.SaúdedaCrianc¸a, Acompanhamento do Crescimento e Desenvolvimento Infan-til. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2002. Available from

http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/crescimento desenvolvimento.pdf

21.Manual para utilizac¸ão da caderneta de saúde da crianc¸a/Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenc¸ão à Saúde, Departamento de Ac¸ões Programáticas Estratégicas, Área Técnica da Saúde da Crianc¸a e Aleitamento Materno. Brasília,Brasil:MinistériodaSaúde,SecretariadeAtenc¸ão à Saúde. Departamento de Ac¸ões Programáticas Estratégicas. Área Técnica da Saúde da Crianc¸a e Aleitamento Materno; 2005.p.38,p.:il(SérieA.NormaseManuaisTécnicos).

22.Organizac¸ãoMundialdaSaúde,Organizac¸ãoPanamericanade Saúde. AIDPI Atenc¸ão integrada às doenc¸as prevalentes na infância.Brasil:MinistériodaSaúde.EditoraMS,Ministérioda SaúdeSecretariadeatenc¸ãoàSaúde;2003.p.1---34.

23.FrankenburgWK.DenverIItrainingmanualkit.1970ed;2009.

24.FrankenburgWK,DoddsJ,ArcherP,ShapiroH,BresnickB.The DenverII:amajorrevisionandrestandardizationoftheDenver DevelopmentalScreeningTest.Pediatrics.1992;89:91---7.

25.NieNH,BentDH,HullCH.SPSS:statisticalpackageforthesocial sciences;1975.

26.DaymontC,ZabelM,FeudtnerC,RubinDM.Thetest charac-teristics ofhead circumference measurements for pathology associated with head enlargement: a retrospective cohort study.BMCPediatr.2012;12:9.

27.BallotDE,PottertonJ,ChirwaT,HilburnN,CooperPA. Develop-mentaloutcomeofverylowbirthweightinfantsinadeveloping country.BMCPediatr.2012;12:11.

28.Halpern R,BarrosAJ, MatijasevichA, SantosIS, Victora CG, BarrosFC.Developmentalstatusatage12monthsaccordingto birthweightandfamilyincome:acomparisonoftwoBrazilian birthcohorts.CadSaudePublica.2008;24:S444---50.

29.deMouraDR,CostaJC,SantosIS,BarrosAJD,MatijasevichA, HalpernR,etal.Riskfactorsforsuspecteddevelopmentaldelay atage2yearsinaBrazilianbirthcohort.PaediatrPerinat Epi-demiol.2010;24:211---21.