Revista

de

Administração

http://rausp.usp.br/ RevistadeAdministração52(2017)317–329

Strategy

and

business

economics

On

the

relationship

between

antitrust

and

strategy:

taking

steps

and

thinking

ahead

Sobre

a

rela¸cão

entre

o

antitruste

e

a

estratégia:

onde

estamos

e

para

onde

podemos

ir

Sobre

la

relación

entre

la

defensa

de

la

competencia

y

la

estrategia:

dónde

estamos

y

hacia

dónde

podemos

ir

Guilherme

Fowler

de

Avila

Monteiro

∗InsperInstitutodeEnsinoePesquisa,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

Received27January2016;accepted4July2016 Availableonline13May2017 ScientificEditor:PaulaSaritaBigioSchnaider

Abstract

Inthis paper,Iexaminetherolethatstrategicanalysishasplayedonantitrustanddiscussnewanalyticalvenues.Inorderto accomplishthis goal,thepaperpresentstwodirections.Initially,Iundertakeareviewofthecurrentdebatebetweenantitrustandstrategy.Iarguethatmuchof thecontemporarydiscussiononthesubjectisfoundedontraditionaleconomicapproachestostrategy,whatleadstothedisregardoftheroleof firmheterogeneityincompetitivedynamics.Inthesecondpartofthepaper,Isketchanapproachtoantitrustbasedontheresource-basedviewof strategy.Thisapproachisparticularlyusefulinexaminingtheconditionsofmarketrivalry,beingacomplement–notnecessarilyasubstitute–to thetraditionalantitrusteconomicanalysis.

©2017DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBYlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Keywords:Strategy;Antitrust;Marketpower;RBV

Resumo

Nesteartigo,éexaminadoopapelqueaanáliseestratégicatemdesempenhadonoantitrusteesãodiscutidosnovoscaminhos.Afimdealcanc¸ar esteobjetivo,otrabalhoapresentaduasdirec¸ões.Inicialmente,realiza-searevisãododebateatualsobrearelac¸ãoentreantitrusteeestratégia. Defende-sequegrandepartedadiscussãocontemporâneasobreoassuntosebaseiaemabordagenseconômicastradicionaisdeestratégia,oque levaàdesconsiderac¸ãodopapeldaheterogeneidadedafirmanadinâmicacompetitiva.Nasegundapartedoartigo,éesboc¸adaumaabordagem deantitrustefundamentadanavisãobaseadaemrecursos.Estaabordageméparticularmenteútilparaexaminarascondic¸õesderivalidadedo mercado,sendoumcomplemento–enãonecessariamenteumsubstituto–àanáliseeconômicaantitrustetradicional.

©2017DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Palavras-chave:Estratégia;Antitruste;Poderdemercado;RBV

∗Correspondenceto:RuaQuatá,300,CEP04504-2369,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil.

E-mail:gfamonteiro@gmail.com

PeerReviewundertheresponsibilityofDepartamentodeAdministrac¸ão,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸ãoeContabilidadedaUniversidadede SãoPaulo–FEA/USP.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rausp.2017.05.004

Resumen

Enesteartículoseevalúaelpapelqueelanálisisestratégicohajugadoenladefensadelacompetenciaysediscutennuevoscaminos.Paraello, sepresentandosdirecciones.Inicialmente,sellevaacabounarevisióndelactualdebatesobrelarelaciónentreladefensadelacompetenciayla estrategia.Seargumentaquegranpartedeladiscusióncontemporáneasobreeltemasebasaenlosenfoqueseconómicostradicionalesdeestrategia, loquellevaaignorarelpapeldelaheterogeneidaddelaorganizaciónenladinámicacompetitiva.Enlasegundapartedelartículo,sedescribe unenfoquedeantimonopolioqueseapoyaenlavisiónbasadaenrecursos.Esteenfoqueesparticularmenteútilparaexaminarlascondicionesde competenciadelmercado,ypuedecomplementar–ynonecesariamentereemplazar–elanálisiseconómicoantitrusttradicional.

©2017DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Esteesunart´ıculoOpenAccessbajolalicenciaCCBY(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Palabrasclave: Estrategia;Defensadelacompetencia;Poderdemercado;RBV

Introduction

Theantitrustanalysisiswidelyrecognizedasan interdisci-plinaryfieldofresearchandpractice,withinwhicheconomics andthelawestablishafruitfuldialog.Asanultimate expres-sionofthissynergy,itiscommontofindeconomicsprofessors teachingantitrustcoursesinlawschools,mainlyinEuropeand theUS.Buildingonthisinterdisciplinaryperspective,Iarguein thepresentpaperthatinadditiontoeconomicsandthelaw,the antitrustanalysiscandrawinspirationfromathirddiscipline: strategy.

Although the above claim is not fundamentally new (see

Foer,2002,2003;Hawker,2003;Oberholzer-Gee&Yao,2010), it is proposed here that much of the previous discussion on antitrust and strategy has been narrowly based on the the-oretical approach proposed by Porter (2001). The objective of this perspective paper is then twofold: (i) to undertake a reviewofthedebatebetweenantitrustandstrategyand(ii)to present a framework inspired by the resource-based view of strategy (Barney, 1991; Peteraf, 1993),which can shed light on newaspects so far disregarded by thetraditional antitrust analysis.

In general terms, the importance of this theoretical exer-cise should not be underestimated. The antitrust policy is an important component of the institutional environment in whichfirms establishtheir perpetual struggle toachieve sus-tained competitive advantages. The economic theory usually applied to antitrust analysis, in turn, is a limited analytical tool sinceitis moreconcerned withunderstandingthe struc-tureandfunctioningofspecificmarkets,castingamacroscopic lookatfirms’strategies.Forthat reason,the strategy scholar-shiphasthepotentialtohelptheadvancementof theantitrust analysis.

The present article is divided into three parts besides this introduction. Section‘Taking steps: what do we knowabout therelationshipbetweenantitrustandstrategy?’makesabroad reviewof theliterature onantitrust andstrategy, stressingits potentialitiesandweaknesses.Section‘Thinkingahead:isthere a role for strategic analysis within antitrust?’ then explores newanalyticalvenuesonthesubject,specificallypresentinga complementaryframeworkfortheantitrustanalysisofmarket rivalry.Section‘Conclusion’concludesthediscussion,posing questionsforfutureresearch.

Takingsteps:whatdoweknowabouttherelationship betweenantitrustandstrategy?

Theideaofincorporatingconceptsfromstrategy–andmore generally from management – inthe antitrustanalysis is not unprecedented.Foer(2002,2003),forexample,usuallyresorts totheimageofantitrustasathree-leggedstool,whichhasbeen restingprecariouslyon onlytwo of them.Thesetwo legsare the LawSchoolandtheDepartmentofEconomics.The third missinglegistheBusinessSchool.Theunderlyingclaimisthat theantitrustanalysisdoesnottakeintoaccount thefirmitself andtheindividualdecisionmakerswithinthefirm.More impor-tantly,theBusinessSchoolwouldbeacounterpointtowhatis understoodastheanalyticallimitationsimposedby neoclassi-caleconomics.AsnotedbyHawker(2003),intheheartofthe Chicagoapproachtoantitrustisthehypothesis(arisingfromthe neoclassicalpricetheory)thatfirmsrationallyseektomaximize theirprofit.Thefocalpointofstrategicmanagement,however, isnotthemaximizationofprofitperse,butobtainingasustained competitiveadvantage.

Theconceptofsustainedcompetitiveadvantageisassociated withtheideaofcorporatesuccessintermsofabove-normal per-formance(i.e.,economicrents)foranindefiniteperiodoftime. According toBarney(1991),afirm hasacompetitive advan-tagewhen establishingastrategyofvaluecreation thatisnot simultaneouslyimplementedbyanycompetitor.Thisadvantage is,moreover,sustainedwhenactualandpotentialcompetitors are unable toduplicatethe benefits associated withthe strat-egy. Becausethebuildingof sustainedcompetitiveadvantage isatentativeprocess,Foer(2003)arguesthatbusinessschools havetheability tohelptheantitrusttomovebeyondthe neo-classicalabstractionsoftheeconomicman–i.e.,theperfectly rationalindividualfoundintheideasespousedbytheChicago approach.1Inaddition,businessschoolshavesomething impor-tant to say about competitive dynamics, which are not fully capturedbyneoclassicalassumptions(e.g.,Oberholzer-Gee& Yao,2010;Pleatsikas&Teece,2001).

1Leary(2003)notesthat“[a]llIwillsayhere,insummary,isthatIbelieveour

Despitethispotential,Oberholzer-GeeandYao(2010)find thatthe influenceof strategic thinkingintheantitrustfieldis virtuallyzero.2Accordingtotheauthors,whilenumerous fac-torsprobablycontributetothislimitedinfluence,threeaspects deservespecialconsideration:Inanessentiallevel,antitrustlaw isprimarilyfocusedonthewelfareoftheconsumer.Although economistsnormallyanalyzetheeffectsofbusinessconductson thewelfareofconsumersandproducers,strategistsarefocused almostcompletely on the welfare of the producer. A second reasonis that strategy scholarship adopts variousapproaches andisperhaps less accurateinits predictionscompared with economics.Giventhediversityofapproachesusedbystrategy researchers,inconjunctionwiththemyriadoffactorsthatmay influencethesuccessofafirm,itiswithoutsurprisethatthefield ofstrategyhasproducedmanycompetingtheoriesaboutthe pre-cisesourcesofsuperiorperformanceofthefirm.Finally,athird possiblereasonmaybethelackofenthusiasmwithinantitrust tocarryoutaccurateassessmentsofdifferentjustificationsfor pastandexpectedbusinessconducts.

Hawker(2003)highlightstwoadditionalproblemsthatmust beaddressedbyanyonewhoseekstoapplybusiness scholar-shipinantitrustanalysis. First,oneshould selectaparticular discipline among the multitude of disciplines that comprise the business curriculum. Second, the academic management researchdoesnothaveareadershipamongbusinessmanagers aswidespreadasacademiclegalresearchhasbetweenlawyers. Consequently,academicresearchcanprovideinsightson busi-nessthinking,butevenmainstreamacademicjournals donot directlyinfluencethethinkingofbusinessmen.

Together,thereferencesdiscussedabovehighlightthe poten-tialgainsandindicatethelowpenetrationofmanagementand strategicthinkingonantitrustanalysis.Thefirst,andtothebest ofmyknowledgetheonlyattempttoformulateaframeworkfor antitrustanalysisexplicitlybasedonstrategydatesbacktothe workofMichaelPorterpresentedatasymposiumsponsoredby theAmericanBarAssociation(ABA)in2001.3Inwhatfollows, IanalyzePorter’sapproach,aswellasthecriticismmadeagainst it.

ThePorter’sapproachtoantitrust

Themainobjectiveofthe2001ABAsymposiumwasto dis-cuss the appropriate role of market concentration on merger reviewsfromtheperspectiveofantitrustlaw.4Inspiredbythis

2 Inorder to analyzetheinfluence ofstrategic management in antitrust,

Oberholzer-GeeandYao(2010)measuretheprevalenceof“strategicideas” inantitrustpoliciesandprocedures.Todoso,theauthorsconducteda com-parisonofnumbersofcitations.First,theycomparethenumberoftimesthat judicialdecisionsandlegaljournalsciterenownedresearchersintheareasof strategyandmicroeconomics.Secondly,theytabulatethecitationstothethree majorjournalsinstrategyanditseconomiccounterpart.Finally,theysearchfor referencestoconceptsthatarecentraltothestrategyandindustrialorganization. 3 TheAmericanBarAssociation’sAntitrustSectionTaskForceon

Funda-mentalTheory,Washington,D.C.,January2001.

4 TheTaskForceMissionStatementprovidedthat“[t]heTaskForceon

Fun-damentalTheorywillexaminewhethertheconcentrationthesisunderlyingthe government’spresentapproachtomergercontrolhasanycontinuingvalidity,in

question, Porter(2001)sketched anantitrustapproach whose essentialpointisthegrowthofproductivity.

Porter(2001)takesacritical attitudeinrelationtothe tra-ditionalantitrustapproach.Hearguesthatalthough thestated roleoftheantitrustpolicyistopromoteandprotectcompetition onbehalfofconsumers’welfare,thisrationaleisoftenunclear, understoodwronglyorwithaverylimitedscope,focusingtoo muchonmarketconcentrationandpricesettings.Inthe concep-tionofPorter(2001),theantitrustshouldbeconcerned,above all,withthegrowthofproductivity,sincethisisthemost impor-tantdeterminantofboththeconsumers’long-termwelfareand thestandardoflivingofacountry.

Porter (2001) notesthat productivitygrowth is associated withinnovation,whichinturnismanifestedthroughthe com-mercialization ofproducts andservicesof highervaluetothe consumeralongwiththedevelopmentofmoreefficientmodes ofproduction.Theinnovativeprocessisgreatlydependentonthe presenceofastrongcompetitioninthemarketplace.According totheauthor,thisistheprimaryjustificationfortheexistence of anantitrust policy:tosafeguardcompetition as aninducer ofinnovationsthatraisetheproductivityoftheeconomy.The maingoaloftheantitrustpolicyisthentoencourageadynamic processofimprovement(i.e.,innovationsinproduct,process, andmanagement),givenitseffectonproductivitygrowth.5In suchacase,higherpricesshouldbeanantitrustwarningsign onlyifitisnotassociatedwithanincreasingvaluedeliveredto theconsumer.6Inthissamelight,thehighprofitabilityofafirm isnotanissueofconcernwhenitreflectssuperiorproductsor benefits obtainedbymeansofoperationalefficiency (seealso

Demsetz,1973).

Regarding the implementation of antitrust policy, Porter (2001)notesthatstandardantitrustprocedure–i.e.,the exam-inationof the number of firmsin amarket, itsconcentration andprofitability–capturesonlyasmallpartofamorecomplex phenomenon,atthesametimethatit deflectsanalysis toless productivedebatesaboutwheretoplacetheboundariesofthe relevant market.Asanalternative,Porter(2001)proposes the useof thefiveforcesanalysisframework(Porter,1985).Any ofthefiveforces(internalrivalry,entry,substituteproductsand services,customersandsuppliers)canbesignificant in deter-mining competition,dependingonthespecificindustryunder

viewoftheempiricalandtheoreticalworkofthepastseveraldecades,mostof whichsuggeststhatconcentrationassuchisapoorpredictorofactualconduct adversetothecompetitiveprocess”.

5 AsnotedbyDavidson(2012),theseideasexpressedbyPorterarenotentirely

inconsistentwiththetraditionalantitrustthinking.

“[...]monopolyprofitsareanunwarrantedtransferofincomefrom con-sumers to producers, but a much more significanteconomic effect of competitionistheencouragementofinnovation.Thatinnovationisthe sourceofmaintainingandincreasingthestandardoflivingintheUnited Statesandthroughouttheworld”.

6 Itisinterestingtonotetheexistenceofalatentcontradictionbetweentheidea

examination.Equallyimportant,foranyofthefiveforces,the causesofcompetitiveintensityaremultidimensional,i.e.,itgoes beyondtheprice.

Themultidimensionalnatureofrivalryamongfirmsis impor-tant inordertounderstandthe link betweencompetition and productivity.AccordingtoPorter(2001),someformsofrivalry haveagreaterimpactonproductivity,beingmorevaluableto society.Forexample,ifcost/pricemarginsareusedasametric of socialbenefit, thenthestrategy of imitationandprice dis-countingseemsidealfromthetraditionalantitrustpointofview; however,fromtheviewpointofproductivitygrowth,thistypeof competitioncouldleadtoalessintensedynamicimprovement oftheeconomy.Bycontrast,competitionbasedon differentia-tioncangeneratealargersetofchoicesforconsumersaswell asmoreintenseinnovationinproductsandprocesses.Inother words,whenconsideringproductivitygrowthasastandardfor antitrust,oneshouldbeawareofthekindofcompetitionthatis pursuedwithinacountry.Thisbringsustoasecondanalytical step:examiningthenatureoflocalcompetition.

Porter(1990)notesthateveninlocationswherefirms com-peteinternationally,thevitalityoflocalcompetitioniscrucial totheincreasingofproductivity.Thelocalcompetitionhasthe powertocreatepositiveexternalitiesforthefirm–forexample, throughthestimulusformarketrivalryandinnovation,aswell as the increased availabilityof skilledlabor, informationand resources.Accordingly,whenthelocalrivalryiscooleddown, acountrysufferstwoeffects:notonlyfirmsintheindustryhave lessincentivetobeproductive,butalsotheentirebusiness envi-ronmentbecomeslessproductive.AccordingtoPorter(2001), the appropriate tool to examine local competition is the dia-mondmodel(Porter,1990)inwhichsixfactorsinteracttocreate favorableconditionsforinnovation.7

Fromanantitrust perspective,boththe fiveforcesanalysis and the diamond model are analytical tools used inorder to answeracentralquestion:how amerger(ifapproved)would affectproductivitygrowth?AlthoughPorter(2001)recognizes thatthedirectestimationofproductivitygrowthisadifficulttask, therelationshipbetweencompetitionandthelong-termincrease inproductivityenablesthedevelopmentofananalytical frame-workdividedintothreestages.First,theantitrustanalystshould examinethesignificanceofthemerger(orjointventure),aswell as thebasicconditionsfor productivitygrowth.Thisinvolves threesteps.(i)Identificationofthesetofrelevantmarketsand submarkets associated withthe merger, andthe geographical areainwhichonecanfindlocalexternalities.(ii)Definitionof amarketsharethresholdabovewhichmergerswillbeanalyzed morecarefully.8(iii)Identificationofthehistoricalperformance

oftheindustryandfirms,aswellasthecharacterizationofthe robustnessofrivalryintheindustry.

7 Thesixfactorsthatencompassthemodelare:(i)factorconditions(human

resources,physicalresources,knowledgeresources,capitalresourcesand infra-structure),(ii)demandconditions,(iii)relatedandsupportingindustries,(iv)firm strategy,structureandrivalry,(v)government,(vi)chanceevents(i.e.,events outsidethecontrolofafirm).

8 Portersuggestsa50%threshold.

In thesecond stage,theanalystmustundertakeacomplete competitiveassessment,usingfiveforcesanalysisandthe dia-mondmodel.Thegoalistopredicttheeffectsofthemergeron productivitygrowth.Specifically,thefiveforcesanalysisisused tomeasurethecompetitionintheindustrytakingintoaccountall marketsandsubmarketsidentifiedinthepreviousstage.Sincea numberoffactorsaffectseachforce,theanalystmustscrutinize eachparticularfactor.Thestartingpointistoidentifythebase level of eachfactorandthedirection itismoving beforeand afterthemerger(increasing,decreasing,orsteady).

Finally,inthethirdstage,ifitisfoundthatthereare signifi-cantadverseeffectsonthecompetitionintheindustryoronthe localcompetition,oneshouldexaminethedirecteffectof the mergeronproductivitygrowth.Thekeyquestionsare:Doesthe operationgeneratesignificantandverifiablebenefitstofacilitate productivitygrowth?Aresuchbenefitsperpetualorlimitedto aspecificinstantoftime?Whatistheprobabilitythatthegains areactuallyrealized?Inansweringthesequestions,theantitrust analystcanmakeadecisiononthemerger.

Porter(2001)liststheadvantagesofusingthefiveforces anal-ysisfortheexaminationofmergersandacquisitions.According to theauthor, the traditional antitrustanalysis isbuilt upona short-term,staticlook,otherconsiderationsbeingaggregatedin theanalysisas“adjustmentarguments”.Thestrategicanalysis, in turn, is based on a multidimensional concept of competi-tionandisnotfocusedsolelyonprice.Strategicanalysisalso makes theprecise definitionof theboundariesofthe relevant marketdispensable,sinceitembodiesallthemajorinfluenceson competition.9Accordingly,theindexesofmarketconcentration (e.g.,HerfindahlHirschmanIndex–HHI)losetheirprominent position intheantitrustanalysis.Thisperspectiveonantitrust found a strong supporter in Weller (2001a, 2001b). In advo-catingtheapplicationoftheapproachintheantitrustanalysis,

Weller(2001b:47)notesthat:

“TheProductivityParadigmisfundamentallynewand dif-ferent innumerous ways. Productivityreplaces efficiency, andstandardoflivingreplacesconsumerwelfare,asprimary goals;itdoesnotuseconcentrationtheory,HHIs, profitabil-ity,priceincreasesandothertoolsofcurrentantitrustanalysis todeterminethelegalissueofwhetherornotasubstantial lesseningof competitionislikely;iteliminatestheneedto determinetherelevantmarket;itusesnewempiricaltoolsthat aremeasurable,understandableandrigorouslikethe widely-usedFiveForcesanalysis,Diamondanalysisofthebusiness environment,andtheMarketShareInstabilityIndex[...]”.

Criticism

When called upon to assess Porter’s proposal, Einhorn (2001), Baker and Salop (2001), andWerden (2001)

formu-9Forthedelimitationofarelevantmarket,thetraditionalantitrustanalysis

lated strong counterarguments to the application of the five forcesanalysisandthediamondmodelinthetraditionalantitrust analysis.AccordingtoEinhorn(2001)Porter(2001)doesnot considerthefactthatmeasuresofconcentrationasindicatedin theHorizontalMergerGuidelinesrepresentonlyafirst-round screening process.Itnot onlyallows for theidentification of “safeharbors”, butalsoprovides afirstapproachtothe prob-lem,so that largeroperationsthat raisecompetition concerns maybeinvestigatedinmoredetail.Moreover,BakerandSalop (2001)notethatmoderneconomictheorydoesnotsupportthe ideathatmarketconcentrationisuselessasaguideformerger analysis.

Einhorn(2001)alsoarguesthat,contrarytothatsuggested by Porter (2001), price-based competition is generally more importantthanproductivityaspectsinasignificantnumberof industries.Inaddition,althoughthedevelopmentofnew prod-uctsisanextremelyimportantaspectofeconomicdevelopment, thisisnot something thatcan beeasily foreshadowed bythe courtsorbyexpertswithoutaconsiderabledegreeof subjectiv-ity.Accordingly,itisproposedthatPorter(2001)failstodefine theconditionsnecessaryforacomprehensiveanalysisof pro-ductivity,withappropriateempiricalmeasuresandatheoretical modelthatrelatesthefiveforcestoidentifiableparametersina givenmerger.

Athird objectofcriticism isthefactthatthe productivity-based approach disqualifies the definition of the relevant market as afundamentalaspect of antitrust analysis.Werden (2001: 68) makes the following comment with reference to

Weller(2001b):

“Mr. Weller apparently would include [ina relevant mar-ket]distantsubstitutes,complementstothem,productsproduced withsimilarinputs,inputsintotheproductionoftheproducts inquestion,andproductsproducedusingtheproductsin ques-tion as inputs. Castingthe net this broadlymay beuseful in identifyingallofthefactorsthatmaysomehowaffectpricesor outputs,butitdoesnotidentifythelocusoflikely anticompeti-tiveeffects”.

Finally, the authors criticize the suggestion – incorpo-rated into the second stage of Porter’s analysis – to define the direction in which each factor that influences the five forces is moving before and after the merger (increasing, decreasing,orsteady).Werden(2001:69),forinstance,argues that

“[T]here is no mechanism (for example, no use of eco-nomicmodels)fordeterminingwhetherachangeinintensity classification is likely to materially affect price, out-put, quality, or any other index of industry performance, nor one for trading off opposing changes in intensity classifications”.

Onamoreelementarylevel,thevariouscommentators con-siderthat Porter’s contribution tothe antitrustanalysis isper se limited to the extent that both the antitrust and the five forcesanalysisseekinspirationfromthesametheoretical frame-work,namelytheIndustrialOrganization.Porterwassuccessful in reversing the logic of the structure-conduct-performance

paradigm,10 providing tools for managers to understand the competitive landscape of an industry and thereby todevelop strategies inordertolessenthe competitive pressures.Under thisview,itisarguedthatPorter’scontributionstoantitrustmay beonlymarginal(i.e.,amendmentstothecurrentGuidelines).11 Attheendoftheday,asalreadyevidencedbyOberholzer-Gee andYao(2010),thePorter’s approachfailedtobecome a ref-erenceinantitrustandthereforetheantitrustthree-leggedstool hasnotyetfounditsmissingleg.Inwhatfollows,Ipresentsome newideasthatmayclearthewayinthesearchforacontribution from strategyfor antitrustanalysis. Aswillbe seen,the path takendiffersfromthatoriginallyproposedbyPorter(2001).

Thinkingahead:istherearoleforstrategicanalysis withinantitrust?

Although the strategic approaches inspired by Industrial Organization(notably,thefiveforcesanalysis)arewidespread inthecorporateworld,thestrategicscholarshipwitnessedthe emergenceofanewstrategicapproachinthe1980s,theso-called Resource-basedView(RBV)(e.g.,Barney,1991;Peteraf,1993;

Rumelt,1984;Wernerfelt,1984).AccordingtoFoss(2005),it was onlyafter the adventof the RBVthat strategy found its currentconfiguration:thekeyaspect ofstrategicmanagement involvescreatingandsustainingacompetitiveadvantageatthe firm level, where a sustainedcompetitive advantage is inter-pretedintermsofextraordinaryrentsobtainedinequilibrium.

Incontrasttothefiveforcesanalysis,theRBVcastsamore microscopiclookatthebusinessagents,havingasaunitof anal-ysisthefirm’sresources.FromtheperspectiveoftheRBV,firms controlasetofproductiveresourceswhichvaryfromcompany tocompany.Aresourcecanbevaluableinaparticularindustryor aparticularmomentintime,andmaynothavethesamevaluein anotherindustryorinadifferentcontext.Moreimportantly,the resourceheterogeneityamongfirmsexplainstheachievementof competitiveadvantage.Theconceptofheterogeneityiscentral becauseithelpsexplaintheexistenceofdifferencesineconomic performancebetweenfirmsthatoperatewithinthesame indus-try.Thisaspectislargelyneglectedbystrategicanalysisinspired byIndustrialOrganization.

Accordingly, Barney (1991) and Peteraf (1993) take on two assumptions when developing their strategic approaches foundedonaresource-basedview.Theassumptionsare:(i)firms withinanindustryareheterogeneouswithrespecttothestrategic

10TheStructure-Conduct-Performancemodelwasdevelopedinthe1930/40

atHarvardUniversity,becomingoneoftheinitialreferencesofIndustrial Orga-nization.Themodelisconcernedwithcausalflowsthatbuild onthebasic conditionsandmarketstructuretowardthebehaviorandperformanceoffirms. Theobjectiveistodescribetheconditionsforincreasingcompetitivenessof industries,havingservedasamajorinspirationforantitrustpolicyinitsearly days.SeegenerallySchererandRoss(1990).

11Yet,itisremarkablethatPorter’sappeal towarda moreholistic

resourcestheycontroland(ii)theresourcesdonothaveperfect mobility,whichcontributestotheperpetuationofheterogeneity for areasonableperiod of time.Considering theexistence of imperfectmobilityofresources,thecreationandsustainability ofeconomicrentsbecomespossible.Barney(1991)andPeteraf (1993),however,developdifferentapproachestotheRBV(see

Foss,2005).Barney(1991)isprimarilyfocusedonthe build-ingofsustainedcompetitiveadvantagesderivedfromRicardian rents.12 Peteraf (1993), on the otherhand, explicitly consid-ersthebuildingofsustainedcompetitiveadvantagefromboth Ricardianrentsandmonopolyrents.13Forthepurposesofthis article,theapproachadvancedbyPeteraf(1993)ismore conve-nientsincetheauthorexplicitlyconsidersthepossibilityofthe firmobtainingmonopolyrents,theobjectofantitrustanalysis.

Peteraf(1993)arguesthatresources controlledbythe firm generateasustainedcompetitiveadvantagewhenfour corner-stones arepresent: (i)resources areheterogeneous withinthe industry,sothatthefirmcangeneratesuperiorincomes (Ricar-dianormonopolyrents);(ii)theexistenceofexpostlimitson competition,sothattherentisnotdissipatedbycompetitionin theproductmarket;(iii)resourcemobilityisimperfect, allow-ingthepreservationoftheeconomicrentwithinthefirm;(iv) existenceof exantelimitsoncompetition,indicatingthatthe marketofproductivefactorsisunabletoappropriateallincome generatedbytheresources.

Inwhatfollows,Idiscusshowtheseideascanbeincorporated intotheantitrustanalysis.

Towardaresource-baseddialogwithinantitrust

Thestrategic analysis inspiredbythe resource-basedview canbeofparticularhelpintheantitrustanalysisofthe competi-tionpatterninanindustry.Specifically,theRBVcanshedlight oncompetitivepeculiaritiesthatwouldremainhiddeninamore traditionaleconomicassessment.Inordertomakemyargument moreprecise,Iroughlydividetheantitrustanalysisofmergers andacquisitionsinfoursequentialsteps:

(i) Theanalysisbeginswiththedefinitionoftherelevant mar-ketofthemerger.

(ii) Basedonthisdefinition,the analystproceeds inthe cal-culationofmarketsharesofthefirmsbeforeandafterthe merger.Thegoalistoidentifywhetherthefirmresulting

12Ricardianrentsarisebecauseofthepresenceofsuperiorproductivefactors,

whicharelimitedinsupply.

13Peteraf(1993:182)notesthat“[i]nmonopolymodels,heterogeneitymay

resultfromspatialcompetitionorproductdifferentiation.Itmayreflect unique-nessandlocalizedmonopoly.Itmaybeduetothepresenceofintra-industry mobilitybarrierswhichdifferentiategroupsoffirmsfromoneanother(Caves andPorter,1977).Itmayentailsizeadvantagesandirreversiblecommitments orotherfirstmoveradvantages.Therearenumeroussuchmodels.Whattheyall haveincommonisthesuppositionthatfirmsinfavorablepositionsface down-wardslopingdemandcurves.Thesefirmsthenmaximizeprofitsbyconsciously restrictingtheiroutputrelativetocompetitivelevels.Thesearemodelsof mar-ketpower.UnlikeRicardianmodels,manyare‘strategic’inthatfirmstakeinto accountthebehaviorandrelativepositionoftheirrivals”.

fromthemergerholdsamarketsharesufficientlyhighas tomakecredibleanypossibleabuseofmarketpower. (iii) Assumingthatthefirmresultingfromthemergerpresents

a highmarket share,the analyst issupposed toexamine the pattern ofcompetition intheindustry.Thegoalisto determinewhethertheremainingagentsinthemarketare abletocompeteeffectivelywiththefirmresultingfromthe merger.

(iv) Basedonthehypothesisthatthepatternofcompetitionin the industry isnot enoughtomitigatethe abuseof mar-ket power, one must examine the efficiencies associated withtheoperation.Thegoalofthisstepistocomparethe gainsarisingfromthemergerwiththepotentialdamageto competitionindicatedintheprevioussteps.

Initsusualtemplate,theanalysisofthepatternofindustry competition(stepiii)essentiallyinvolvesfouraspects:therole ofimports(areimportsaneffectiveremedyagainsttheexercise ofmarketpower?),theconditionsofentryofnewcompetitorsin theindustry,thewayrivalryisexpressedinthemarket,andthe existenceofconditionsforthecoordinationofdecisionsinthe industry.Specificallyregardingtheanalysisofmarketrivalry,it isexpectedthatcompetitorsbeabletoabsorbasignificantshare of themarket inresponsetotheexerciseof marketpowerby the mergedfirm.Therivalryisconsiderednoteffective when competitorsoperateatfullcapacity,the expansionofthe pro-ductioncapacityoftherivalfirmsisnoteconomicallyfeasiblein lessthantwoyears,theexpansionofproductioninvolveshigh costsor,inthecaseofdifferentiated products,consumersare characterizedbyhighbrandloyalty.

Thiswayof understandingmarket rivalryclearlyindicates theinfluenceofIndustrialOrganizationontheantitrust analy-sis.Whenaddressingaparticularcase,anantitrustanalysttries tocharacterizetherivalryintherelevantmarket.Tothisend,he orsheassumesthatfirmsareroughlyequivalent(exceptforthe presenceofdifferentiatedproducts)andexaminestheindustry as awhole. Recent(or not-so-recent)models ofdemand sys-temswithwhichmergersimulationcanbeperformedexplicitly recognize differences among firms’ products and predict the likely conduct following amerger (see, for instance,Carlton & Keating, 2015; Coate & Ulrick, 2016; Nevo, 2000). This typeofapproachhaspositiveaspects,allowing,forexample,the identificationofthecompetitivepatternofthemarket(Bertrand competition,Cournotcompetition,etc.).Yet,considerationsof individualfirmsandtheirresourcesare,inmostcases,ignored. Evenwhentheanalystseekstoincorporateinheranalysismore subtleaspectsofthefirms,shefindsherselfatalosssinceshe doesnothavesuitableanalyticaltools.Asaresult,moredetailed analyses ofthe firmsare atrisk of becomingmere anecdotal reports.

Doesthefirmhaveeconomicrent?Whatisthenatureof thisrent?

Ifafirmhasasustainedcompetitiveadvantage,thismeans that it produces somelevel of economic rent. As previously noted,firmsmayhaveRicardianrentsor monopolyrents.On theonehand,theconditionofheterogeneitybetweenfirmsmay beassociatedwiththepresenceofsuperiorproductionfactors, whicharelimitedinsupply.Thesefactorsofproductionarethe basisofRicardianrents:thefirmsthatowntheproductionfactors areabletogethigherprofitspreciselybecausethereisa short-ageinthesupplyofunderlyingvaluableresources.Ontheother hand,theheterogeneityoffirmsmayresultfromspatial compe-tition(Hotellingcompetition),productdifferentiation,barriers tomobilitywithintheindustryitself,advantagesderivedfrom size(e.g.,economiesofscale),etc.Theseresourcesarethebasis ofmonopolyrentsbecausetheyallowthe firmtodeliberately restrictitsproductionwithoutallcustomersstopping consump-tionofthegoodorservice.

It is interesting to note that according to the structure-conduct-performance paradigm, if a firm gains persistently abovenormalprofits,it isassumedthat someformof market powerexistsinthemarket.Quitethereverse,theChicagoSchool assumesthatintheabsenceofbarrierstotradesupportedbythe state,thehigherprofitabilityofthefirmindicateshigher produc-tionarrangements.TheRBVisinthemiddleground:although notdenyingthepossibilityofmonopolyprofits,theRBValso considers the possibility that above normal returns represent Ricardianrentsassociatedwithparticularresourcesheldbythe firm(Locketta&Thompson,2001).Theantitrustanalystmust thereforeunderstandtheoriginofthesuperiorperformanceof thefirm.

Doestheeconomicrentoffsetthecostincurred?

Assumingafirmhasmonopolyprofit,akeyconditionmustbe metinorderforthefirmtosustainthiscompetitiveadvantage.As amatteroflogic,beforeanyfirmestablishesasuperiorposition, theremustbelimitedcompetitionfor thatposition;otherwise themarketcompetitionwoulderodeanydifferentialincome.In otherwords,theremustbeexantelimitstocompetition.

The condition of exante limit to competition is analyzed within the RBV as acondition of imperfection inthe factor marketinsuchawaythatcompetitionbetweeneconomicagents doesnotgenerateanexcessiveriseofthecost(price)ofstrategic resources.Giventheexistenceofmarketimperfections,afirm isabletoacquirearesourceatalowerpricethanthepresent valueoftheincomestreamassociatedwiththeresourceitself. Thisconditionensuresthatthefirmwillbeabletoeffectively generateapositiveflowofincome.Incontrast,intheabsence ofmarketimperfections,firmscouldobtainonlynormalprofits.

Istheeconomicrentchallenged?

Themerefactthatacompanyearnsaneconomicrent(i.e., achievesacompetitiveadvantage)doesnotindicatethatthefirm issuccessful in sustainingthisrent. The sustainabilityof the competitiveadvantage requiresthat the condition of resource heterogeneitybepreserved.Ifheterogeneity isaphenomenon ofshortduration,theincomeisshort-livedandthefirmenjoys

temporarycompetitiveadvantage.Thus,subsequenttothefirm establishing a superior position – and thereby earning rents – theremust be forces that limit competition for those rents (Peteraf,1993).Inotherwords,therentisonlysustainedwhen thereareexpostlimitstocompetition.Theconceptofanexpost limit tocompetition isnotrestrictedtothe ideaofbarriersto entry.AsnotedbyLockettaandThompson(2001:746):“firms thathavesuperiorresourcesand/orarebetteratdeployingthose resourcesthanotherswillbeabletoearnaboveaveragereturns. However,inthepresenceofchangesindemandandinnovation, sustainedaboveaveragereturnsdonotnecessarilyindicatethe presenceofbarrierstoentry”.

AccordingtoPeteraf(1993),theRBVemphasizestwo criti-calfactorsthatdeterminethesustainabilityofincome,namely: imperfectsubstitutabilityandimperfectimitability.Ingeneral, thepresenceofsubstitutesreducestheincomeofafirmby mak-ingthedemandcurveofamonopolistoroligopolistmoreelastic. Ontheotherhand,firmscantakeadvantageofisolating mech-anismsinordertogainprotectionagainstimitationandthereby preserve their income.AccordingtoRumelt(1984),isolating mechanismsincludepropertyrightstoscarceresources, infor-mation asymmetry, switchingcosts and buyer’ssearch costs, reputation,andeconomiesofscaleassociatedwithspecialized assets.

Barney (1997)argues that the costdisadvantage of a spe-cificcompetitortoimitatearesourcemaybederivedfromthree sources,beyondthelegalprotectionprovidedbypatents.First, theacquisitionor developmentof aresourcecanbebasedon specifichistoricalconditions. In thiscase, thefirm that owns theresourceischaracterizedbyfirstmoveradvantageorpath dependence.Secondly,theimitationofaresourcecanbecostly duetothepresenceof causalambiguitybetweentheresource andthecompetitiveadvantage–thatis,managersmaynotfully understand the relationship between resource and economic profit.Thistypeofsituationoccursgenerallywhentheresources thatgeneratecompetitiveadvantagearepartofthedaily expe-rienceof acompanyandthereforeare notnoticed.Examples aretheorganizationalcultureofthefirmandthegood relation-shipwithitssuppliers.Inthethirdandlastplace,theimitation ofaresourceheldbythefirmcanbecostlywhentheresource representsasocially complexphenomenon.Inthiscase,even thoughonemayspecify thewayinwhichresourcesgenerate competitiveadvantage(absenceofcausalambiguity),the effec-tiveimitationoftheresourcemaybetoocostly.Asanexample, evenassuming thatwe canclearlyidentifythe organizational cultureasasourceofcompetitiveadvantageinaparticularfirm, thisdoesnotimplythatarivalisabletomimicsuchaculture.

entrantstendstobeubiquitous(Locketta&Thompson,2001). Althoughthisargumentdoesnotcompletelychallengethe the-oryofcontestablemarkets,itsuggeststhattheantitrustanalysis must be implementedwith care,taking into account the role playedbytheheterogeneityoftheresourcesheldbythefirms.

Istheeconomicrentappropriatedbythefirm?

Ahigherincomenotbeingchallengeddoesnotmeanthatit isautomaticallyappropriatedbythefirm.Economicprofitwill onlybesustainediftheresourcesarecharacterizedbyimperfect mobilitywhichensuresthatincomeistiedtothefirm.

Fromthestrategicpointofview,resourceimmobilityensures thatresourceholdersareunabletoappropriateallof therents generatedwithinthefirm.Ifresourcesweremobile,rivalfirms would be able to get control of the sources of competitive advantage.Atthemargin,thecompetitionbetweenfirmswould causethe resourceholdertocapturethe fulleconomicprofit.

Peteraf (1993) argues that resources are imperfectly mobile when theyare somewhat specialized tothe specificneeds of the firm (Williamson,1975) or when theyare co-specialized (Teece,1986).Otherresourcescanbeimperfectlymobile sim-plybecausethetransactioncostsassociatedwithitstransferare toohigh.

Fromtheantitrustperspective,theimportantpointtonoteis thatimperfectlymobileresourcesremainlinkedtothefirmand thereforeavailable for usein thelongterm. Returningtothe discussiononthetheoryofcontestablemarkets:ifthedominant positionofafirmintheindustrystemsfromaresourcedeveloped over time (pathdependence) and, moreover, such a resource cannotbeeasilyremovedfromthefirm(resourceimmobility), thebarrierstoentryinthe industryaremuch higherthanthe traditionalantitrustexaminationmaysuggest.

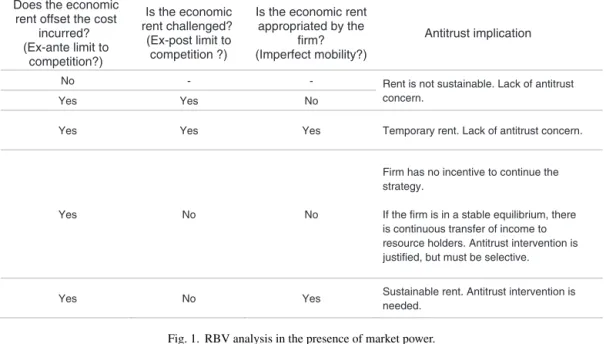

In general terms,the RBVteaches us that sustained com-petitiveadvantagerequirestheheterogeneityofthefirm,theex anteandexpostlimittocompetition,andimperfectmobilityof resources.Assoonas theseconditions aremet,theeconomic profitwillbesustained.Inantitrustterms,theimplicationsare clear:ifafirmisabletogeneratemonopolyprofitsand simulta-neouslyisabletosustainthisprofit,thenantitrustintervention becomesnecessary.Amuchmoresubtleissueemergeswhenone takesintoaccountthatnotallfirmswishingtoobtainmonopoly profitwillbesuccessful.TheRBVtellsusthatmonopolyprofit issustainedonlywhentheconditionslistedabovearemet.In theseterms,itispossibletosaythat(seealsoFig.1):

• If thecost incurredtoestablish acompetitiveadvantage is

higherthantheincomeearned,economicrationalityimplies thatthefirmdoesnotpursuethestrategyandthusthereisno antitrustconcern.Thesamegoesforthecasewhereincome ischallengedbyexpostcompetitionand,simultaneously,the firmfindsitdifficulttoappropriatetheincomegenerated.

• Whenthefirmisabletoappropriatethe income(imperfect

mobilityofresources),buttheincomeischallengedbyexpost competition,thecompetitiveadvantageistemporaryandmay beunderstoodasaninherentpartofcapitalistdynamics.

• Finally,whenresources aremobileandincomeisnot

chal-lengedbyexpostcompetition,twosituationscanhappen:(i)

thefirmmaynothavetheincentivetocontinuethestrategy, sinceitfailstoappropriatetheincome;(ii)thefirmmaybein astableequilibriumsothatthereisacontinuoustransferof incometoresourceholders.Inthiscase,antitrustintervention isjustified,butmustbeselective–itmaybenotenoughto intervenejustintheproductmarket.

Illustration

Ipresentinthissectionsomeempiricalevidence.The discus-sionoutlinedhereshouldbeseenasanillustrationandnotasa deliberatetestoftheapplicationoftheRBVlogictoantitrust. Specifically,Ireassessacaseanalyzedin2008bytheOfficeof FairTrade(OFT),theBritishantitrustauthority.Itreferstothe acquisitionoftheonlineDVDrentalbusinessofAmazon(UK) bythecompanyLovefilm.

Asexpected,theOFTtriedtodefinetherelevantmarketof the operationinitsinitialreviewof thecase.To thisend, the antitrustauthorityconductedacriticallossanalysis(Harrisand Simons,1991;Katz&Shapiro,2003),findingevidencethatthe relevantmarketisbroaderthanjusttheserviceofonlineDVD rentals.TheOFT,however,faceddifficultiesinaccurately defin-ing a boundary for the market. On the onehand, consumers can access video content invariousalternative ways. On the other hand,the OFT failed tounambiguously identify a sec-ond best option for content delivery channels for consumers to replace online DVD rental. The OFT chose,then, to ana-lyzethecompetitiveclosenessbetweenLovefilmandAmazon, and between the merged companies and alternative delivery channels.

TheOFTdrewheavilyonfieldresearchtomeasurethe diver-sionratioofconsumers(i.e.,thecross-elasticitybetweengoods), andoninternaldocumentsofthepartiestodescribetheir busi-nesspractices.Thequantitativeanalysisbasedonthefieldstudy identifiedthehypothesisthatthemergercouldcausea substan-tialreductionofcompetition,givingspaceforthepotentialabuse of dominantpositionbythemergedcompanies.Byanalyzing thedocumentssubmittedbytheparties,however,theOFT even-tuallyrefutedthehypothesisofnegativeeffectsofthemerger, once itbecameclearthat thepartiesconsistentlymonitorand respondtomovementsofothercompetitors,including compa-niesthat donotoperatedirectlyinthe marketofonlineDVD rentals.

OfparticularinterestisthefactthattheOFTwasunableto clearlyidentify aboundaryfor the relevantmarket.The OFT arguedthatthereisalargenumberofchannelsthroughwhich consumers canaccess videocontent,making itimpossibleto drawaclearboundarybetweenthem.Mybasicargumentisthat aresource-basedassessmentofthecasecanbringnewinsights to thisanalysis. Istart from the OFTown description of the channels by whichconsumers canaccess film andTV video content.Themaincharacteristicsofthesealternativechannels arepresentedinTable1.

Table1

ChannelsbywhichconsumerscanaccessfilmandTVvideocontent.

Channel OFTassessmenta Consumptioncharacteristics Companies’resource

differentials

OnlineDVDrental (ODR)

Subscriptionserviceswherebycustomerspayafixed monthlyfeewhichentitlesthemtoreceivethroughthe postDVDswhichtheyhaveselectedonlineinadvance fromawiderangeoftitles.Oncethecustomerhas watchedaDVD,he/shepoststheDVDbacktotheODR supplierinaprepaidenvelopewhereupontheODR suppliersendsthenextavailableDVDonthecustomer’s list.Customershavenotimelimitsimposedwithin whichtheymustreturntheDVDand,accordingly,no latefeesareincurred.

Homeconsumption Homedeliveryofthemovie Absenceoftimelimitto returntheDVD

Flexibilitytowatchthemovie accordingtoconsumer’sown availability

Moviesbackcatalog Logisticcapabilities Technologycapabilities (onlineuserinterface) Competenceoncustomer acquisitionandretention (brand)

Brickandmortar rental(traditional DVDrental channel)

CustomerspayasetfeeperdisktorentaDVDfora nightand/oraslightlyhigherfeeforrentingforalonger period.Individualbrickandmortarstorestraditionally donotofferabackcatalog(i.e.,DVDsthatarenot recentreleases)onthescaleofODRproviders.

Homeconsumption Flexibilitytowatchthemovie accordingtoconsumer’sown availability

Shoplocation

Competenceoncustomer acquisitionandretention (brand)

DVDretail ConsumerscanpurchaseDVDsfromanumberof alternativeretailchannels.Despiterecentprice reductionsinDVDretail,permanentpurchasesarestill substantiallymoreexpensiveonaper-unitbasisthan ODRandotherrentalsbuthavethebenefitofpermanent accesstothecontent.

Homeconsumption Homedeliveryofthemovie (onlinepurchase)

Noreturnandfulluse flexibility

Moviebackcatalog Logisticandtechnology capabilities(online purchase)

Payperview(PPV) Dedicatedtelevisionchannelsshowfilmsatscheduled intervalsthatconsumerscanpayforinadditiontothe televisionsubscriptionpackagesofwhichPPVchannels areapart.WithPPVthefilmisshownatthesametime toeveryoneorderingit.Traditionallythenumberof filmsavailableatanygiventimeissmallcomparedto ODR,andaccessisonaone-offbasisbuthasthe advantageofconvenienceinasmuchasconsumersdo notneedactivelytosearchandselecttitlesintheway requiredbyODRorbrickandmortarrental.

Homeconsumption Homedeliveryofthemovie Reductioninsearchingand selectingcosts

Technologycapabilities (onlineuserinterface) Distributioncostis minimal(usingan existingchannel).

Specialistfilm channels

Consumerscansubscribetobasicandpremiumchannel packagesfromcableoperators,satelliteproviders,and telephonecompaniesusingcableorIPTV,andother multi-channeldistributorsthroughmonthlysubscription packages.Choiceisrelativelylimitedandtitlesare usuallyavailabletoconsumerslaterthantheyare availabletobuyorrentbut,likePPV,specialistfilm channelshaveconvenienceadvantages.

Homeconsumption Homedeliveryofthemovie Reductioninsearchingand selectingcosts

Distributioncostis minimal(usingan existingchannel).

Videoondemand (VOD)

VODoperatesthroughacomputerserverandenables viewerstoaccesscontentatanytimefroma pre-determinedlistoffilmsandTVprograms.Unlike PPV,VODallowsconsumerstowatchafilm/TV programatanindividualtimeoftheirchoosing.Choice ofbackcatalogwithVODmaybesignificantly restrictedbycomparisontoODRbuttitlescanbe purchasedonaone-offbasisratherthanbysubscription only.

Homeconsumption Flexibilitytowatchthemovie accordingtoconsumer’sown availability

Technologycapabilities (onlineuserinterface)

FreetoairTV GivenfreetoairTVdoesnotrequiresubscriptionor incrementalpaymentabovethecostoftheFreeview box,thereisnoincrementalcostforviewingthecontent butchoiceisrelativelylimitedandtitlesareusually availabletoconsumerslaterthantheyareavailableto buyorrent.

Homeconsumption Lowcost

Distributioncostis minimal(usingan existingchannel).

Internetdownload Consumerscangainaccesstofilmsontheircomputers viatheinternet.Oncerented,customerstypicallyhave 24htoviewtheprograms/films.

Homeconsumption Homedeliveryofthemovie Useflexibility

Technologycapabilities (onlineuserinterface)

a OFTassessmentaspresentedon‘AnticipatedacquisitionoftheonlineDVDrentalsubscriptionbusinessofAmazonInc.byLovefilmInternationalLimited’,

Does the economic rent offset the cost

incurred? (Ex-ante limit to

competition?)

Is the economic rent challenged?

(Ex-post limit to competition ?)

Is the economic rent appropriated by the

firm? (Imperfect mobility?)

Antitrust implication

No - - Rent is not sustainable. Lack of antitrust concern.

Yes Yes No

Yes Yes Yes Temporary rent. Lack of antitrust concern.

Yes No No

Firm has no incentive to continue the strategy.

If the firm is in a stable equilibrium, there is continuous transfer of income to resource holders. Antitrust intervention is justified, but must be selective.

Yes No Yes Sustainable rent. Antitrust intervention is needed.

Fig.1.RBVanalysisinthepresenceofmarketpower.

Need for movies for home consumption

Other movie consumption needs

Specialist film channels

PPV Free to air TV Brick and

mortar rental Online DVD rental Internet download

VOD DVD retail

(online)

II IV III

I

Film studios

Big retailers (including digital) Non-competitors

Weak Capabilities in offering flexibilty Strong to consumers; content delivery

capabilities; movie back catalogue

Fig.2.Characterizationofcompetition–onlineDVDrental.

Source:DevelopedbytheauthorbasedonPeteraf&Bergen(2003).

equivalence–whosebasicfunctionistoallowtheassessment ofcommonalitiesbetweencompanies.Marketneeds correspon-denceisadichotomousindicatorthatseekstocapturewhethera particularcompanyorchannelservesornotthesameconsumer needs as the focal company/channel. Capability equivalence referstotheextenttowhichaparticularcompanyhasresource andcapabilitybundlescomparabletotheresourceand capabil-itybundleofthefocalcompany/channelintermsofitsabilityto meetsimilarconsumerneeds.Theemphasisisontheroleplayed byresources,whichmaybedissimilarinkindbutsimilarinuse orfunctionality.

Theconnectionofthetwoconceptsoccursthrougha graphi-calrepresentation(seeFig.2).TheY-axisrepresentsthemarket needscorrespondence(measuredasyesorno),andtheX-axis representsthecapabilityequivalence(measuredashighorlow). CompaniesinquadrantIarethosethatmeettheconsumerneed atcomparablelevelsof satisfaction.AccordingtoPeterafand

companymarket,norhavethe resources andcapabilities that allowthemtodosoatthispoint.

BasedonTable1,IdefinethatonlineDVDrentalcaterstothe consumerneedofhomemovies.Morespecifically,theonline DVDrentalenablesconsumerstowatchmovieswithouttheneed toleavehomeinordertogetthe contentandoffers the flexi-bilityofwatchingaccordingtotheirpersonalavailability,over anundeterminedperiodof time.Aimingtoofferservicesthat cansatisfythisconsumerneed,companiesmustpossessstrong resourcesandcapabilitiesonfilmcatalog,logisticalcapabilities (tosend moviesvia mail,control DVDreturns andship new DVDs),technologycapabilities(especiallyregardingtheonline interface withthe consumer) and must also possessa strong brandthatencouragesretentionofconsumers.

Itisworthnotingthattherequirementslistedabovedonot representasetof resources that must necessarily beretained so that a company can competewith the online DVD rental service. In the caseof downloading moviesvia the Internet, forexample,itisplausibletoassumethatthistypeofchannel representsasignificantrivalofonlineDVDrental,evenifitdoes notmakesenseforthecompanytohaveastrongcompetence inlogistics.Inthisparticularcase,thecompanymusthavethe technologicalexpertisetoenableittodelivercontent(i.e.,the film)totheconsumeras soonas apurchaseismade.Forthe purposesofIanalysistherefore,itmaybeappropriatetoconsider thatcompaniesmustpossessstrongdeliverycapability,giventhe businessmodelselected.

Onefactorthatdistinguisheschannelsisconsumer flexibil-ityinwatchingthe movieaccordingtotheirown availability. Theflexibilitycomesfromthebusinessmodelofeachtypeof channel,andisdirectlyassociatedwiththeresourcesthat sup-porteachbusinessmodel.Asstated,intheonlineDVDrental model,theconsumercankeeptheDVDforanundefinedperiod oftime(seeTable1).Thebrickandmortarstore,ontheother hand,cannotallowtheconsumertokeeptheDVDforan indef-initeperiod.Ifit doesso,consumerswouldbeunabletofind the DVDthey wantedin the store,and thiswould erode the attractivenessofthestoretoconsumers.Alternatively,thestore couldholdalargestockofcopiesofeachvideo,butthatwould incurhigherstockcostsineachstore.Asanotherexample,itis reasonabletoassumethat therearetechnicalandcommercial aspectsjustifyingthepracticeofpayperviewchannels show-ingamovieonafixedschedule,leavingtheconsumertoplanto watchthemovieatthespecifiedtime.Thesamereasoningabove appliesinthecaseofthedeliveryconvenience(greaterwhenthe consumerreceivesthemovie/contentathome)andinthecase ofavailablemovie options(moviebackcatalog).Onceagain, boththedeliverymodelandthemenuofavailablemoviesare associatedwiththeresourcesthatsupporteachbusinessmodel.

Fig.2attemptstoillustratethesecharacteristics.Onepoint tobearinmindisthe fact that theresources andcapabilities analyzedinthehorizontalaxisdonotrepresentanexhaustive listing.Infact, therewouldbelittle gainindoingso.Forthe manager/strategistaswellasfortheantitrustanalyst,thepoint of greatest relevancehere is toemphasize the resources that distinguishcompaniesofquadrantIfromcompanieslocatedin

quadrantII.14AnantitrustanalystcouldallocateinquadrantI, besidestheonlineDVDrental,thedownloadingofcontentvia Internet,VODandDVDretail(assumingpurchasesweremade online anddelivered bymailor courier).Thissetofbusiness models offers theconsumer agreater choiceset(movie back catalog),besidesgreaterflexibilityandconveniencecompared tobrickandmortarretail,PPV,broadcastTVandspecialized movie channels (quadrant II).Quadrant III presentsbusiness models that, despite not meeting the need for domestic con-sumptionofmovies,gatherresourcesthatmakeitpossibletodo so.

TheOFTreportsthatthereissufficientevidencesuggesting thatthecompanyLovefilmconsidersalltypesofvideocontent deliverychannelsasitscompetitors.Inlinewiththediscussion intheprecedingsection(seeFig.1),itmeansthatotherforms ofcontentdeliverymaybeabletoimposeex-postcompetitive pressure on the mergedcompanies, thuschallenging its eco-nomicrent.Itisinterestingtonotethatfromaresource-based perspective (Fig.2),onemayidentify threeimplicit assump-tionsunderlyingtheOFTconclusion.First,theOFTconclusion isbasedontheideathatthedownloadviatheinternet,theDVD retailandtheVODimposefiercecompetitionononlineDVD rental.Theycandosobecausetheyhavesimilarresourcesthat enablethemtofulfillthesameconsumerneed.Second,because companies in quadrant II have weak capabilities in offering flexibility toconsumers, the OFT conclusiondepends on the assumptionofhighcrosselasticityofdemandbetweenthe prod-ucts andservicesoffered bycompanieslocated inquadrant I andthoselocatedinquadrantII.Finally,theOFTconclusionis foundedontheassumptionoflowentrybarrierssothat compa-nieslocatedinquadrantIIIcanimposecompetitivepressureon thecompanieslocatedinquadrantI.

Largely,thegoalhereisnottodeterminewhethertheanalysis undertakenbytheOFTwasappropriateornot.Theobjectiveis toshowhowtheanalysisofcompanies’resourcescangenerate insightsonantitrustanalysiswhichcannotbe generatedfrom receivedapproaches.

Whatcomesnext?

AlthoughIhaveillustratedtheapplicationoftheRBVlogic toantitrust,muchofthepreviousdiscussionisbasedonastatic ideaofmanufacturingindustries.Whilethisfactisaclear lim-itationofmypaper,italsoinvitesustopushtheboundariesof thediscussioninnewdirections.Inwhatfollows,Ioutlinetwo potentialdirectionsforfutureresearch.

A first direction comes from the emergence of business ecosystemsasaneworganizationalform.Abusinessecosystem

14PeterafandBarney(2003:316)notethat“[w]hilefactors,ingeneral,may

rangefrompedestrianandpoorqualityfactors,tothosethatarerareandspecial

is a networkof organizations, whichmake possible the pro-visionof agivenproductorservicethrough bothcompetition andcooperation.AccordingtoMoore(1998,p.168),abusiness ecosystemisan“extendedsystemofmutuallysupportive orga-nizations;communitiesofcustomers,suppliers,leadproducers, andotherstakeholders, financing,tradeassociations,standard bodies, labor unions, governmental and quasigovernmental institutions, and other interested parties. These communities cometogetherinapartiallyintentional,highlyself-organizing, andevensomewhataccidentalmanner”.

Thekeyaspectisthatthe“traditionaleconomictheorydoes notfocusonbusinessecosystemsasadistinctformof organi-zationanddoesnot provideconceptualtemplates thatcanbe usedtodetect,inspect,andassessbusinessecosystem”(Moore, 2006, p. 35). However, in its heart, business ecosystems are basedoncoreresources andcapabilities,whichareexploited withthepurposeofproducingacoreproductorservice(Moore, 1996).ItmeansthattheRBVmaybringimportantcontributions tothediscussion,focusingonorganizationalandtechnological trade-offs.KapporandLee(2013),forinstance,showhow orga-nizationalformsshapenewtechnologyinvestmentsinbusiness ecosystems.AdnerandKaapor(2010)examinehowthe struc-tureoftechnologicalinterdependenceaffectsfirmperformance inbusinessecosystems.

Asecond direction intheapplication of the RBVlogicto antitrust is the analysis of the relationship between competi-tionandinnovation (e.g.,Shapiro,2012).Productivitygrowth fosteredbyinnovationisbutoneexampleof this,andmarket structuresshouldbeassessedbytheirabilitytobothdeliver con-sumersurplusandlong-runincentivestoinnovate.Thenotion ofstaticefficiencythatunderliesmuchofmydiscussioncould benefitfromthemoredynamicanalysisofantitrustandstrategy asdevelopedbyTeeceandcoauthors(e.g.,Jorde&Teece,1990; Sidak&Teece,2009).

Anotherrelatedareaofinvestigationisthecompetition pat-tern associated to multi-sided platforms (e.g., Evans, 2003) mainlyintheinternet(e.g.,Eisenmann,Parker&VanAlstyne, 2006; Varian, 1999).Although recentstudies havediscussed the contractual nature of platforms (e.g., Monteiro, Farina & Nunes,2014),itisstillnecessarytodeepentheinvestigationof theunderlyingresourcesthatsupportthisspecificorganizational form.Potentialrelevantantitrustinsightsmayderivefromsuch investigation.

Conclusion

Thepresentarticleisdividedintotwoparts.Initially,I under-takeareviewofthecurrentdebatebetweenantitrustandstrategy. Itisspecificallynotedthatmuchofthecontemporarydiscussion onthesubjectisfocusedontheproductivity-basedapproach pro-posedbyPorter(2001).Thisapproach,whilesheddinglighton importantantitrustissues,istosomedegreenotfullyinnovative, sincebothPorterandthetraditionaleconomicantitrustanalysis seekinspirationinthesamesource(IndustrialOrganization).In thesecondpartofthepaper,Iproposeanewapproachtoantitrust basedontheresource-basedviewofstrategy.Thisapproachis particularlyusefulinexaminingtheconditionsofmarketrivalry,

beingacomplement–notnecessarilyasubstitute–tothe tradi-tionalantitrusteconomicanalysis.TheapplicationoftheRBV toantitrust isappealingbecause it encouragesamore micro-analyticalviewofthephenomenonofcompetition,favoringa moredetailedstudyoftheidiosyncrasiesoffirms.

Asaresearchagenda,futurestudiesshouldseeknewareas withinantitrustinwhichtheRBVcancontribute.Researchers shouldpayparticularattentiontoRBVpotentialcontributions fortheantitrustassessmentofbusinessecosystems,thedynamic conditionsofcompetition,andmulti-sidedplatforms.Similarly, it isexpectedthat antitrustagencies beopened for thesenew approaches.Itisincreasinglyimperativethatthoseresponsible fortheenforcementoftheantitrustlawsbemoreconnectedwith thosewhoareaffectedbytheirdecisions,i.e.,entrepreneursand managers.Theantitrustapproachinspiredbytheresource-based viewofstrategyiswellsuitedtoaccomplishthistask.

Conflictsofinterest

Theauthordeclaresnoconflictsofinterest.

References

Adner,R.,&Kaapor,R.(2010).Valuecreationininnovationecosystems:How thestructureoftechnologicalinterdependenceaffectsfirmperformancein newtechnologygenerations.StrategicManagementJournal,31,306–333. Baker,J.B.,&Salop,S.C.(2001).Shouldconcentrationbedroppedfromthe mergerguidelines?UniversityofWestLosAngelesLawReview,33,3–16. Barney,J.B.(1991).FirmResourcesandSustainedCompetitiveAdvantage.

JournalofManagement.,17(1),99–120.

Barney,J.B.(1997).Gainingandsustainingcompetitiveadvantage.Upper SaddleRiver,NJ:PearsonPrenticeHall.

Baumol,W.J.,Panzar,J.C.,&Willig,R.D.(1982).Contestablemarketsand thetheoryofindustrystructure.SanDiego:HarcourtBraceJovanovich. Carlton,D.W.,&Keating,B.(2015).Antitrusttransactioncosts,andmerger

simulationwithnonlinearpricing.TheJournalofLaw&Economics,58(2), 269–289.

Caves,R.E.,&Porter,M.(1977).Fromentrybarrierstomobilitybarriers: Con-jecturaldecisionsandcontriveddeterrencetonewcompetition.Quarterly JournalofEconomics,91,241–262.

Coate,M.C.,&Ulrick,S.W.(2016).Unilateraleffectsanalysisin differenti-atedproductmarkets:Guidelinespolicy,andchange.ReviewofIndustrial Organization,48(1),45–68.

Davidson,K.M.(2012).PorterandWeller:Anantitrustoddcouple? Commen-tary,.Availableat:http://www.antitrustinstitute.org/files/467.pdf(accessed 12.12.12)

Demsetz,H.(1973).Industrystructure,marketrivalry,andpublicpolicy.Journal ofLawandEconomics,16(1),1–9.

Einhorn,M.(2001).Fiveforcesinsearchofatheory:MichaelPorteronMergers.

UniversityofWestLosAngelesLawReview,33,35–43.

Eisenmann,T.,Parker,G.,&VanAlstyne,M.(2006).Strategiesfortwo-sided markets.HarvardBusinessReview,84(10),92–101.

Evans,D.S.(2003).Theantitrusteconomicsofmulti-sidedplatformmarkets.

YaleJournalonRegulation,20,325–382.

Foer,A.A.(2002).Thethirdlegoftheantitruststool.JournalofPublicPolicy &Marketing,21(2),227–231.

Hawker,N.W.(2003).Antitrustinsightsfromstrategicmanagement.NewYork LawSchoolLawReview,47(21),67–85.

Jorde,T.M.,&Teece,D.J.(1990).Innovationandcooperation:Implications forcompetitionandantitrust.TheJournalofEconomicPerspectives,4(3), 75–96.

Kaapor,R.,&Lee,J.M.(2013).Coordinatingandcompetinginecosystems: Howorganizationalforms shapenewtechnology investments. Strategic ManagementJournal,34,274–296.

Katz,M.L.,&Shapiro,C.(2003)..pp.49–56.Criticalloss:Let’stellthewhole story(Spring2003)AntitrustMagazine.

Leary,T.B.(2003).Thedialoguebetweenstudentsofbusinessandstudentsof antitrust.NewYorkLawSchoolLawReview,47(21).

Locketta,A.,&Thompson,S.(2001).Theresource-basedviewandeconomics.

JournalofManagement,27,723–754.

Monteiro,G.F.A.,Farina,E.M.M.Q.,&Nunes,R.(2014).Thecontractual natureoftwo-sidedplatforms:Aresearchnote.EconomicAnalysisofLaw Review,5(1),153–165.

Moore,J.F.(1996).Thedeathofcompetition:Leadership&strategyintheage ofbusinessecosystems.NewYork:HarperBusiness.

Moore,J.F.(1998).Theriseofanewcorporateform.WashingtonQuarterly,

21(1),167–181.

Moore,J.F.(2006).Businessecosystemsandtheviewofthefirm.TheAntitrust Bulletin,51(1),31–75.

Nevo,A.(2000).Mergerswithdifferentiatedproducts:Thecaseofthe ready-to-eatcerealindustry.TheRANDJournalofEconomics,31(3),395–421. Oberholzer-Gee,F.,&Yao,D.A.(2010).Antitrust–Whatroleforstrategic

managementexpertise?BostonUniversityLawReview,90,1457–1477. Peteraf,M.A.(1993).Thecornerstonesofcompetitiveadvantage:A

resource-basedview.StrategicManagementJournal.,14(3),179–191.

Peteraf,M.A.,&Barney,J.B.(2003).Unravelingtheresource-basedtangle.

ManagerialandDecisionEconomics,24,309–323.

Peteraf, M. A., & Bergen, M. E. (2003). Scanning dynamic competitive landscapes:Amarket-basedandresource-basedframework.Strategic Man-agementJournal,24,1027–1041.

Pleatsikas,C.,&Teece,D.(2001).Theanalysisofmarketdefinitionandmarket powerinthecontextofrapidinnovation.InternationalJournalofIndustrial Organization,19,665–693.

Porter,M.E.(1985).Competitiveadvantage:Creatingandsustainingsuperior performance.NewYork:TheFreePress.

Porter,M.E.(1990).Thecompetitiveadvantageofnations.NewYork:Free Press.

Porter,M.E.(2001).Competitionandantitrust:Towardsaproductivity-based approachtoevaluatingmergersandjointventures.UniversityofWestLos AngelesLawReview,33,17–34.

Rumelt, R.P. (1984).Towards a strategic theoryofthe firm.InB. Lamb (Ed.),Competitivestrategicmanagement.EnglewoodCliffs,NJ:Prentice Hall.

Scherer,F.M.,&Ross,D.(1990).Industrialmarketstructureandeconomic performance.USA:HoughtonMifflinCompany.

Shapiro,C.(2012).Theratedirectionofeconomicactivityrevisited.InJ.Lerner, &S.Stern(Eds.),Competitionandinnovation:Didarrowhitthebull’seye?

(pp.361–410).Chicago:TheUniversityofChicagoPressBooks. Sidak,J.G.,&Teece,D.J.(2009).Dynamiccompetitioninantitrustlaw.Journal

ofCompetitionLaw&Economics,5(4),581–631.

Teece,D.J.(1986).Profitingfromtechnologicalinnovation:Implicationsfor integration,collaborationlicensingandpublicpolicy.ResearchPolicy,15, 285–305.

Varian,H.(1999).Marketstructureinthenetworkage.preparedfor under-standingthedigitaleconomyconference,May25–261999.Washington, DC:DepartmentofCommerce.

Weller, C. (2001a). Anevolutionof Merger-JV analysis:The productivity paradigmasapositiveantitrustpolicyforcompetitivenessandprosperity.

UniversityofWestLosAngelesLawReview,33,45–55.

Weller,C.(2001b).HarmonizingantitrustworldwidebyevolvingtoMichael Porter’s dynamic productivity growth analysis. The Antitrust Bulletin,

XLVI(4),879–917.

Werden,G.J.(2001).Mergerpolicyforthe21stcentury:CharlesDWeller’s guidelinesarenotuptothetask.UniversityofWestLosAngelesLawReview,

33,57–70.

Wernerfelt,B.(1984).Aresource-basedviewofthefirm.StrategicManagement Journal,5,171–180.

Wernerfelt,B.(1989).Fromcriticalresourcestocorporatestrategy.Journalof GeneralManagement,14,4–12.