through the provision of current guidelines for the prevention, control, and treatment of cholera.

In addition, PAHO is providing direct technical assistance to the countries; promoting the in-ser-vice training of personnel, especially laboratory

DaETsr

X'I jED

personnel; participating in the coordination of as-sistance from international agencies; and facilitat-ing the countries' procurement of supplies and equipment for laboratories and other health services.

Cholera Epidemic in Peru

Since January 23, 1991, Peru has suffered a severe cholera epidemic marked by high morbidity and wide geographical extension. The first cases were reported in Chancay, a town on the Pacific coast in the environs of Lima, and almost simul-taneously, in Chimbote, another coastal town lo-cated 400 kms north of Chancay. In both places there was an increase in the number of adults seeking medical care for acute diarrhea. Since cholera was suspected, the National Institute of Health was authorized to do the appropriate laboratory studies, resulting in the rapid isolation of the causal agent.

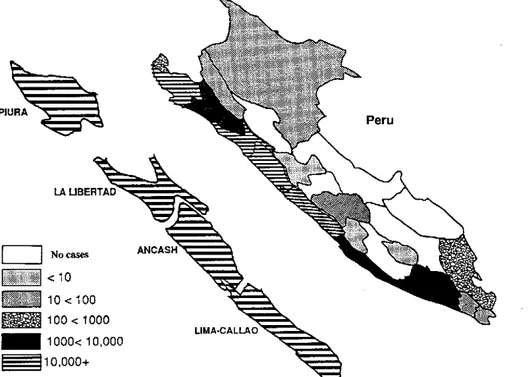

Over the next few days cases were reported in the cities of Piura and Lima, and then in other localities on the coast or near it (Figure 2). It was noteworthy that the disease appeared almost simultaneously in communities located along a 1,200 km length of coastline. The mountain and tropical forest regions also have been affected, approximately 16 and 29 days respectively after the start of the epidemic. The agent isolated from the feces of patients in the affected areas is the Vibrio cholerae, serovariant 01, biotype El Tor, serotype Inaba. It is considered quite probable that this epidemic forms part of the

seventh pandemic of cholera which began in 1961. The genetic studies that make it possible to estab-lish this relationship were carried out by the United States Centers for Disease Control.

Since it is impossible to perform bacteriological tests on all patients, the epidemiological monitor-ing requirements established by the Ministry of Health for the health services call for reporting cases of acute diarrhea. These are considered prob-able cases of cholera.

Figures 3 and 4 show the tally of reported cases, hospitalized cases and deaths due to acute diarrheal disease in the country from the start of the epidemic until March 20, 1991.

The laboratory at the Health Ministry's National Institute of Health isolated the cholera agent in the feces of patients from each of the affected localities. Once this confirmation was obtained, epidemiological monitoring was carried out to as-sess the extent of the disease in the affected area.

The distribution of cases by age group cor-roborates the diagnosis of cholera. The data on age come from a survey carried out in Chancay during the first weeks of the epidemic, in which it was noted that 81% of the patients were five years old

Figure 2. Areas affected by cholera outbreak, by Department, Peru, through 20 March 1991.

PIURA

Peru

| | No cases

<10 ... 10<100 m= 100< 1000

M 1 000< 10,000

I I 10,000+

.

ports, farming and fishing villages and fishing ports. The sea is very rich in plankton and fauna.

The mountain region, or the Andes range, lies between the coast and the tropical forest. It ac-counts for 31.8% of the national territory. The population lives between 2,000 and 3,500 meters above sea level, the altitude most favorable for economic activities. Rains are abundant and it is rich in natural resources and has areas suitable for raising livestock. Nonetheless, it is the most depressed region of the country and the most neglected by the State.

The tropical forest covers 57.5% of Peruvian territory, and is essentially the Peruvian portion of the Amazon basin. It is the least populated region of the country. Its climate is tropical, with abundant rains throughout the year. As in many mountain areas, inadequate communication links make this region largely inaccessible from the rest of the country, a situation presenting problems for nation-al integration.

Peru is experiencing rapid urban growth. In 1940, 35% of the population was urban and 65% rural and agricultural. By 1990 this ratio was reversed, with 70% urban and 30% rural. This process has taken place in a disorganized fashion and without basic services being available to serve large population centers. People have migrated to the coastal cities and especially to metropolitan Lima, which ac-counts for almost 30% of the national population.

International migratory flows have for many years been of little importance in Peru. The same is true of international tourism, affected by various factors.

Internal migration, by contrast, is intense, and has accelerated in the past 30 years due to social, politi-cal and economic factors. These include the depreciation of agricultural production, the need to seek new forms of employment, the excessive governmental centralization and the subversion that has principally affected the mountain region. The main migratory movements have taken place in the mountains and the coastal strip, resulting in the formation of

shantytowns-pueblosjóvenes-in the major cities, especially Lima. More than 50% of the inhabitants of the major urban centers now live in these shantytowns, suffering from a critical deficiency of basic services including housing, water, sanitation, health and education.

Economic Factors

For the past 30 years Peru has been gripped by a serious economic crisis, which has worsened in the last 10 years. It is manifested in a declining gross domestic product, inflation, fiscal deficit, declining exports, deterioration of the productive apparatus and an external debt of $17 billion. All this has generated a situation of structural poverty affecting

57% of the country's population, with high rates of

illiteracy, unemployment and under-employment, and a lack of housing and basic services.

Two percent of the population receives 19% of national income, while 60.3% receives only 23.8%. The remainder is distributed in intermediate strata. Approximately 60% of workers are employed in the so-called informal sector, that is, self-employed outside the control of State standards and regula-tions. Many operate as itinerant peddlers, including thousands of street vendors who sell food under unhygienic conditions and without any type of sanitary controls.

The Health Sector

The public health sector in Peru is highly central-ized, and has been very restricted in recent years with regard to the allocation of budgetary resources as a consequence of structural adjustment policies. This, together with inefficient administration and political and technical discontinuity, means that public health programs and services have increas-ingly lagged behind the needs of the population.

Excessive centralization has resulted in the un-derdevelopment of middle and local-level struc-tures, which are extremely dependent on the central level. This is a critical situation which has diminished the ability of the health sector to respond to problems.

Programs have been declining, and in practice have virtually disappeared. Primary health care has been reduced to a minimum, and is less and less available to the population. Although a process of regionalization and decentralization is underway, it is still very incipient and is not making a major

impact.

e

Aspects of the Health Situation

The risk of disease and death is very high, espe-cially among children in the poorer areas of the country. Morbidity and mortality are closely re-lated to serious deficiencies in environmental sanitation.

Among the indicators reflecting this situation, the infant mortality rate is 88 per 1,000, with a low of 61 per 1,000 in metropolitan Lima and a high of 138 per 1,000 in Huancavelica (1987). Proportional mortality of children under age 5 is 45% of total deaths.

Water Supply and Basic Sanitation

Drinking water is a very limited resource in Peru and basic sanitation is also lacking. Only 55.2% of the population has access to drinkingwater, 22.3%

in rural and 67.2% in urban areas. Sanitation ser-vices provide coverage to 41.3% of the total population, to 54.3% in urban areas and only to

16.6% in rural areas.

Water distribution networks are in poor condi-tion, resulting in problems of distribution and of contamination by short circuits and losses. Millions of people lack piped water into their homes and must purchase water from private vendors who bring it in tank trucks.

Furthermore, monitoring of drinking water quality is very poor due to the lack of economic resources, equipment, laboratory reagents and ap-propriate legal standards. Treatment of solid was-tes, food inspection, control of insects and rodents and housing hygiene are all seriously deficient, posing severe risks to public health.

Wastewater is discharged untreated into rivers and the ocean, resulting in extensive contamination from fecal matter and other elements. In Lima, wastewater is produced at an estimated rate of 16.25 m3/sec and is discharged into the Rímac

River. The situation is similar in other urban areas.

Organization of the Ministry of Health and the Health Services

With the emergence of the epidemic, the Ministry of Health organized the following committees at the central level to channel and coordinate resour-ces and implement actions:

National Executive Committee, comprised of:

Minister of Health Vice-Minister of Health

Director of the National Institute of Health Technical Director of Human Health

National Operational Committee, comprised of:

Vice-Minister of Health

Technical Director of Epidemiology Technical Director of Human Health Technical Director of Environmental Sanitation

Director of Supply and Logistics Director of Human Resources

Expert in Medical Technical Management Expert in Press and Communication Expert in Research.

This organizational model was replicated in the affected communities with local adaptations and multisectoral participation. In addition, a cholera control committee was set up in every hospital,

presided over by the Director of the Hospital, responsible for daily monitoring of the number of cases treated, number hospitalized, and deaths, and reporting this data to Epidemiological Surveillance of the Ministry of Health. In addition, the commit-tee monitors the availability of resources, the coor-dination of actions with other agencies, and communication with the public.

Teams of doctors, nurses and aides have been assembled and trained, and standards for the care and treatment of cases have been formulated and disseminated.

At the level of hospital services, areas designated Cholera Treatment Units (CTU) were set up within hospitals for those patients requiring hospitaliza-tion. In some towns it was necessary to have an entire hospital function as a CTU.

Treatment of Cholera Cases

Two protocols have been designed for the medi-cal management of cholera cases, one for use by the branch health services (health centers, positions and posts), and the other for hospitals.

Network of Renal Units

In the course of this epidemic a large number of patients have survived dehydration but have developed acute renal insufficiency (ARI) that requires hemodialysis. This complication occurs if initial therapy is delayed or if intravenous solutions are not adequately utilized. The treatment of ARI requires technological resources which are more expensive and difficult to obtain. Some of the deaths during this epidemic have resulted from limited ability to treat this complication rather than from dehydration per se. To deal with this problem, a Network of Renal Units was created to offer coordinated hemodialysis services for patients that need them.

A preliminary report from three selected Lima hospitals documents 57 cases of ARI that required hemodialysis in the period between February and March 1991 (Table 2).

Table 2. Number of cholera cases hospitalized, of acute renal insufficiency (ARI), and of cases requiring

hemodialysis. Selected hospitals of Lima, Peru, February and March 1991.

Hospital-

Hemo-Hospitals ized ARI dialysis

Edgardo Rebagliati 400 80 8

(Social Security)

Cayetano Heredia 1,511 110 33

(University)

Arzobispo Loayza 204 39 16

The network of local health services plays a very important role in controlling the epidemic. Preven-tive actions and early detection of cases are made possible by these services and their links with com-munity organizations.

It has been demonstrated that if an affected per-son begins taking oral rehydration salts soon after the first symptoms appear, the risk of serious dehydration is reduced considerably. This lessens the likelihood that the patient will require transfer to a hospital for intravenous treatment.

A network for community distribution of ORS, which was already in place for the control of infant diarrhea, is being strengthened. The service delivers envelopes of ORS and instructions for their use in cases of diarrhea.

Measures to Control the Spread of the Epidemic

These measures are assumed intersectorally, with participation of regional and local governments and popular organizations. There are two types:

IMMEDIATEMEASURES

Public health education. This is intended to

promote personal and domestic hygiene measures that reduce the risk of contracting the disease. The campaign uses all available communications media, with emphasis on the need to:

* Boil drinking water

* Avoid drinking beverages of doubtful origin (juices, soft drinks, etc.)

* Avoid eating raw food, especially raw seafood (in Peru fish and shellfish are often consumed raw as

cebiche.)

* Wash hands frequently, especially before and after using the bathroom.

* Clean the kitchen utensils, especially cutting tables, immediately after use.

Control offood sales by vendors. The measures

provide for the sanitary inspection of cooked food sold on the street. It is planned that these food sales will eventually be eliminated and replaced with formally established cafeterias. (Eating in the street, at vendors' stalls, is another very widespread practice.)

Chlormnation of water and monitoring of the

quality of water supplied to the population. Water

treatment plants are increasing the chlorination of drinking water, and the level of residual chlorine in the water supply is monitored so it does not fall below 0.5 ppm. Chlorine is being distributed for the treatment of household water reserves.

Community treatment of excreta and solid

wastes. Information on appropriate waste disposal

methods is disseminated to households which lack sewerage systems. Lime is being distributed for the sanitary treatment of excrement and refuse in septic tanks.

Sanitary treatment of patients' clothing and

excreta. Procedures have been set up for handling

bedclothes and other soiled matter from the Cholera Treatment Units. The materials are transported in plastic bags to the hospital laundry, where they are immediately washed and boiled. Bathrooms and any containers used by patients for vomiting or elimination are disinfected frequently with sodium hypochlorite (lye) or creosote.

Disposal of corpses. Corpses are transferred

im-mediately to the hospital mortuary, where they are disinfected before being turned over to family members. Families are warned to hold funeral ser-vices as early as possible and to avoid any prolonged funeral rites. In the mortuary, surfaces which have come in contact with the corpse are disinfected promptly.

Chemoprophylaxis. This is indicated only when

cases occur in confined populations (barracks, prisons, asylums) or when a new outbreak begins in a previously unaffected area.

Following the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO), cholera vaccine is not used.

Ending the practice of irrigating with

wastewater. In coordination with the Ministry of

Agriculture, measures have been taken to avoid the use of drainage water for the irrigation of cultivated

*

fields.

MEDIUMAND LONG-TERMMEASURES

In coordination with the Ministry of Housing and Construction and the municipal services respon-sible for basic sanitation, sanitary engineering projects are being designed which will greatly im-prove the sanitation infrastructure in the rural and urban areas. These projects include latrine build-ing; renovation of water supply and drainage net-works; renovation of wastewater treatment systems, especially the oxidation ponds; installa-tion of systems for chlorinating potable water, and

improvement of water treatment plants.

Economic Impact

shown in helping Peru with large donations and the provision of human resources.

The cost of lost exports has not been determined, but different sources place it between $US10 million and $US400 million. This has led to con-flicts between various sectors and the Ministry of Health, with unfavorable consequences for the con-trol efforts.

Another negative development has been the decrease in sales of fish along the entire coastline. The fish are caught by village fishermen who depend on this income to support their families. Although the Ministry of Health's recommendation was not to eat raw fish or shellfish, there has been a decrease in the consumption of seafood in general, with the consequences already mentioned.

Conclusions

- The cholera epidemic affecting Peru is of great magnitude, and is the largest of the known epidemics, at least in the last hundred years. - The mode of introduction of the V. cholerae that

triggered the epidemic is still undetermined. - The country offers highly propitious conditions

(poverty, lack of water and sanitation, extensive pollution) for the spread of cholera.

- The rapid reaction of the Ministry of Health-which alerted the population quickly, organized medical services and carried out an appropriate health education campaign, with active com-munity participation-has resulted in a very low death rate and the early recovery of thousands of patients.

- The costs of responding to the epidemic are extremely high, and there have also been nega-tive economic consequences for the production and marketing of marine products.

All of the above probably could have been avoided with timely investments in the water and sanitation infrastructure.

- The epidemic can spread to neighboring countries, making it necessary to coordinate ac-tions, exchange information and form ap-propriate technical teams in order to minimize the impact of the disease.

(Source: Horacio Lores and Julio Burbano, PAHO/Peru; Eduardo Salazar, José Luis Seminario and Augusto E.

López, Ministry of Health, Peru.)

Cholera Situation in Ecuador

* When the cholera epidemic in Peru was first reported, the authorities in Ecuador immediately embarked on active epidemiological surveillance in all the populations on the Ecuador-Peruvian border and issued a decree declaring a public health emer-gency in the Provinces of El Oro and Loja on the

eruvian border.

At the same time, steps were taken to prioritize the activities being undertaken by the National Committee on Cholera Prevention with support from the following subcommittees: Epidemiologi-cal Surveillance; Patient Care; Education; Com-munication and Logistics; Finances; Public Relations; Laboratories; Environmental Health, and Sanitary Control.

In the areas that were most at risk, an emergency plan was implemented for action to be taken in the event of a cholera epidemic in Ecuador, and an epidemiological surveillance system was put into effect in all the provincial health services throughout the country.

Audiovisual materials were prepared and widely disseminated through the voice and print media. At the same time, environmental sanitation activities were stepped up, as was the chlorination of water in urban water supply systems.

In addition, adequate quantities of oral rehydra-tion salts, intravenous solurehydra-tions (Hartman), and * antibiotics (tetracycline and erythromycin in

pediatric suspension) were distributed to hospitals and health centers serving the most vulnerable populations; beds were readied with special mat-tresses to accommodate cholera patients; and the medical and paramedical personnel in the public health universities were trained.

As a result, the health teams in the areas at greatest risk were prepared to face the imminent threat of cholera.

Presence of the First Cases of Cholera

Despite the preventive measures taken by the Ministry of Public Health, on Friday, 1 March 1991, the health authorities in El Oro Province reported to the central level that 9 patients with a clinical picture of profuse aqueous diarrhea, vomiting, and rapid dehydration had sought medi-cal care at the hospital in Machala (capital of El Oro Province).

The next day, 2 March, a team of national epidemiologists, with the active participation of PAHO/WH-O, initiated an epidemiological inves-tigation of the outbreak, with the following results:

Clinical Diagnosis