Colombian Agricultural and Livestock Institute took steps to bring industrial processing of food, notably Pacific coast fish and shellfish, under closer control.

The second confirmed case of cholera was reported on March 22. The patient, an adult man also from Tumaco, not related to the first patient, began suffering from diarrhea on March 17.

On March 26 four new cases were reported, three adults and a nine-year-old girl. Two of the patients came from Tumaco and two from the township of Salahonda, an hour by boat north of Tumaco.

A team of physicians, epidemiologists and en-vironmental health experts has been sent to strengthen control actions in Tumaco. The Minister of Health has declared a red alert along the entire Pacific coast of the country. Preparations have been made to care for 100 patients in Tumaco and a similar number in adjacent townships.

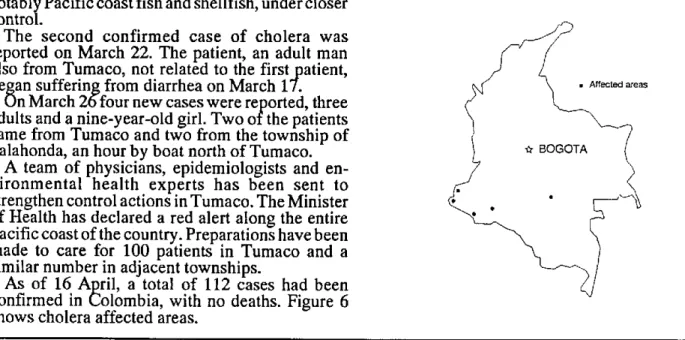

As of 16 April, a total of 112 cases had been confirmed in Colombia, with no deaths. Figure 6 shows cholera affected areas.

Figure 6. Cholera affected areas, Colombia.

.

As of the closing date for this publication, 20 April 1991, the Ministry of Health of Chile notified 15 confirmed cases of choler; 13 in the Santiago Metropolitan Region and two in the Second Region Antofagasta.

Brazil reported 5 suspected cases of cholera, of which one imported case from Peru has been confirmed in Tabatinga, Amazonas State.

Historical Background of Cholera in the Americas

As the second pandemic of cholera spread be-tween 1829 and 1850, the disease reached the coast of the Americas for the first time. Ships arriving from Europe introduced the infection in 1832, despite having been quarantined at Gross Island, near Quebec, in Canada. From there, the disease attacked the city of Quebec and spread along the St. Lawrence River basin into the interior of the country.

Cholera appeared in the United States at the same time. It was prevalent in New York and Philadel-phia until 1834, when it crossed the Rocky Moun-tains and spread west to the Pacific Coast. On the East Coast, it reached as far north as Halifax, Nova Scotia, in Canada.

During this pandemic, cholera also invaded Latin America and the Caribbean. It is possible that it appeared in Chile, Peru and Ecuador in 1832 (Haeser, according to Pollitzer), although the accuracy of this information is questioned by Hirsch (as quoted by Pollitzer).

In 1833, Mexico was stricken, in both the coastal regions and the high plateaus. The disease remained prevalent until 1850 in northern Mexico, and until 1854 in the south.

Also in 1833, cholera apparently imported from Spain ravaged the island of Cuba. From there it spread to New Orleans, Louisiana and Charleston, South Carolina in 1835.

In 1836 and 1837, an appearance of cholera on the Guiana coast of northeastern South America did not have a major impact. Guatemala and Nicaragua, however, suffered devastating epidemics, which may also have affected El Salvador and Costa Rica. The presence of cholera in Peru in 1839 has been suggested but is not confirmed.

In 1848, cholera again attacked the southern United States. New York was once more the source of infection, along with New Orleans. From there it spread to the eastern Rocky Mountains and up to Canada, which also received new sources of infec-tion arriving directly from Europe. Mexico was affected and from New Orleans, cholera spread as far as the Chagras River in Panama, which at that time was part of Colombia.

The epidemic continued spreading in 1850, reaching California. The disease was transported by ship from Panama to San Francisco, and then to Sacramento by land. In South America, it penetrated Colombia, reaching the Bogotá plains;

10

and according to not very reliable data, it reached Quito, Ecuador (Hirsch, as quoted by Pollitzer). In that year and the one which followed, cholera again violently attacked Cuba, and, apparently for the first time, Jamaica.

During the third pandemic, which took place from 1852 to 1860, the United States, Mexico and the Caribbean islands were again affected. Trinidad and Tobago and St. Thomas were infected in 1853. Between 1854 and 1855, cholera continued to be widespread throughout the United States, Mexico and the Caribbean islands (attacking the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico, Uruguay and Colombia). In that same year it invaded Venezuela, arriving in a steamboat from Trinidad that berthed at Barran-cas and was confined to nearby Isla de La Plata, in the Orinoco River. From there it spread west, with a violent outbreak in 1855 in the port of La Guaira. In less than ten days the disease reached Caracas. It disappeared from Caracas in 1856 and from the rest of the country in 1857.

Brazil was affected for the first time in 1854, although there are references to an epidemic in the Pará State in 1851, affecting Rio de Janeiro State in 1855 and Pará in 1855 and 1856. Uruguay also was infected in 1855.

In 1856 there were cholera outbreaks in Argen-tina, in Central America-including Costa Rica, El Salvador and Honduras-and in the Guianas. During this third pandemic, Nicaragua and Guatemala were reinfected in 1855 and 1857

respectively.

During the fourth pandemic from 1863 to 1875, cholera returned to several Caribbean islands between 1865 and 1870. Introduced from Marseil-les, France to Guadeloupe between 1865 and 1866, it attacked Santo Domingo in 1866, St. Thomas in 1868 and Cuba from 1867 to 1870. South America was also affected, Chile in 1866 and Paraguay from 1866 to 1871.

The disease reached the United States in 1865 or 1866, with a serious outbreak in May 1866 in New York. Some observers blamed the outbreak on reinfection by ships coming from Europe, while others believed it to be a flare-up of an existing infection. The spread of cholera in the United States was accelerated by troop movements after the Civil War and by the extension of railway lines to the interior of the country after 1849.

Railway travel was responsible for the spread of cholera to the Midwest as far as the State of Kansas. In Albuquerque, New Mexico, a single case marked the western limit of the invasion of 1866.

Ships transporting soldiers were blamed for spreading the disease to Texas, Louisiana and other southern states.

Cholera appeared in Honduras in 1866, lasting until 1871.

In 1867 there were renewed outbreaks in the principal cities that had suffered the previous year.

An infection originating in New Orleans caused cholera outbreaks in Central America, Nicaragua and British Honduras (now Belize) between 1866 and 1868. Guatemala also experienced outbreaks in 1866, and Brazil was affected again that year.

At the same time, the disease circulated among Paraguayan soldiers during the war against Brazil and Argentina. It reached Corrientes, Argentina and in 1868 infected Uruguay.

In that year, the spread of cholera into the interior provinces of Argentina resulted in the infection of Bolivia and Peru. The epidemic reached the Pacific Ocean, its first known occurrence on the west coast of South America. Chile was infected in the same year.

In 1867, Brazil was reinfected from Paraguay, with the infection spreading to the states of Rio de Janeiro and Rio Grande do Sul between 1867 and

1868.

Argentina was stricken between 1873 and 1874.

In 1873, in the United States, the city of New

Orleans and the Mississippi River basin were again affected critically.

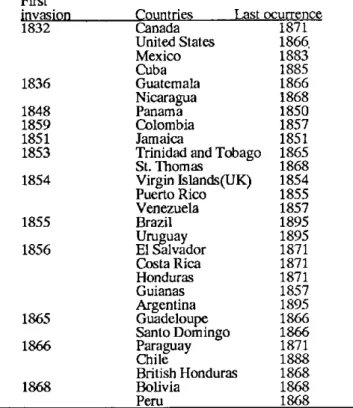

Table 1 shows the presence of cholera in the Americas from the first to the fifth pandemic.

Table 1. First invasion and last occurrence of cholera cases in countries and territories in the Americas.

First invasion

1832

1836

1848 1859 1851 1853

1854

1855

1856

1865

1866

1868

Countries Last Canada

United States Mexico Cuba Guatemala Nicaragua Panama Colombia Jamaica

Trinidad and Tobago St. Thomas

Virgin Islands(UK) Puerto Rico Venezuela Brazil Uruguay El Salvador Costa Rica Honduras Guianas Argentina Guadeloupe Santo Domingo Paraguay Chile

British Honduras Bolivia

Peru

ocurrence 1871 1866 1883 1885 1866 1868 1850 1857 1851 1865 1868 1854 1855 1857 1895 1895 1871 1871 1871 1857 1895 1866 1866 1871 1888 1868 1868 1868

The fifth pandemic (1881-1896) caused cholera to be imported into New York in 1882 in a ship from Naples, Italy and Marseilles. This had little impact, however, as the infection did not become implanted.

Mexico suffered major outbreaks from 1882 to 1883, Argentina from 1886 to 1888, Uruguay in 1886, and Chile from 1886 to 1888.

In New York the disease was again successfully controlled in 1892, despite the arrival of eight heavily infected ships. Only ten cases occurred and the infection did not spread.

The fifth pandemic did cause cholera outbreaks in Brazil from 1893 to 1895, in Argentina from 1894 to 1895, and in Uruguay in 1895.

In the sixth pandemic, from 1899 to 1923, cholera did not succeed in reaching America. The westernmost point affected was the island of Madeira, in 1910.

In the course of the seventh and current pandemic initiated in 1961, a case of unknown origin was discovered in Texas, in the United States, in 1973.

Eight sporadic cases appeared in Louisiana in 1978, and three asymptomatic infections were detected. Since then, new autochthonous cases have continued to appear, 18 in 1986, six in 1987 and seven in 1988, related to the consumption of raw oysters harvested from the Gulf of Mexico. In 1989 no new autochthonous cases were reported, and in 1990 two cases were reported in the State of Louisiana.

References:

Moll, A. Aesculapius in Latin America. New York,

Saunders, 1944.

Pollitzer, R. Cholera. Geneva, WHO, 1959.

(Source: Alvaro Llopis, Professor, Department of Sanitary Engineering, and Juan Halbrohr, Professor, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Central University

of Venezuela, Caracas.)

Epidemiological Surveillance of Cholera

Epidemiological surveillance for the early detection or follow-up of cholera cases in recently infected areas should take into account the need for information on case occurrence, laboratory confirmation, and risk factors associated with the environment-water, waste, food. Environmental factors are discussed in detail elsewhere in this issue.

Surveillance of diarrhea cases is the basis for early discovery of the fact that cholera has appeared in a non-endemic area. Both the treatment centers and health workers in the community should keep daily records. It is essential that health workers be trained to recognize the signs of a probable cholera outbreak, such as:

- Increase in the daily number of diarrhea patients, especially those with rice water stool.

- Liquid diarrhea causing serious dehydration or death in persons over the age of 10, especially in non-endemic areas.

When such changes in the normal diarrhea pattern are noted, health workers should immedi-ately report them to the referral establishment or to the designated local health official, providing the name, address, age, and sex of every patient and the date of onset of the disease. The referral establishment should make arrangements without delay for bacteriological and epidemiological in-vestigation to confirm the etiology of the outbreak. At this point it is possible to adopt appropriate control measures and to submit a report to the Pan American Health Organization, in accordance with

International Health Regulations, so that PAHO in turn can disseminate the information to the Member States of the WHO.

Unfortunately, some countries do not report cases occurring within their borders out of fear that restrictions will be imposed on travelers or on their trade. Authorities who are reluctant to report cases should be made aware that the information they provide helps with negotiations for the elimination of restrictions and promotes international collaboration.

The health authorities in newly infected areas, sometimes pressured by a hostile press and an anxious and demanding public, may take an ex-treme attitude and introduce measures that are in-effective and even counterproductive for controlling the disease, such as quarantining a family, a community, or an area where cases of the disease have been identified or imposing a cordon sanitaire and restricting the movement of persons or merchandise within or outside the infected areas. Restrictions on the movement of people, merchandise, or food in general that compromise an area's economy are not necessary. Such measures contribute to popular hysteria and per-petuate mistaken concepts about the severity, infectiousness, and spread of the disease. They also tend to discourage the subsequent reporting of cases.

Fear of the disease, and even panic, are not unusual in communities where deaths have occurred due to cholera. If the cases can be treated quickly and effectively, fears and misgivings will dissipate, and families will be more inclined to

12