T

HE

1982

EMERGENCY

UITRALO-W VOLUME SPRAY

CAMPAIGN AGAINST AEDES AEGYPTI

ADULTS IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME1

J. E. Hz&ion2

I

NTRODUC’I’ION

The Vector Control Commit- tee of Suriname’s Bureau of Public Health (Bureau voor Openbare Gezond- heidszorg, B.O.G.) decided in April

1982 to spray the capital, Paramaribo, and the border towns of Nieuw Nickerie and Albina twice each with an ultralow volume (UIV) spray of malathion to kill Aedh aegypti adults. This decision was taken because of concern about numer- ous dengue cases in Suriname over the previous six months, lack of any other way of directly attacking dense A. ae- gypi infestations, and a need to find out how effective ULV spraying alone would be in future emergencies. This report is a personal assessment of the campaign in Paramaribo that directs particular atten- tion to the spray dosage chosen, the spray cycle employed, and the ways used to gauge the results obtained.

’ This article will also be published in Spanish in the Bo- his de Za Ojicina Sanitan;? Panamericana. 1987. 2 Entomologist, Ministry of Health, Bureau of Public

Health, Paramaribo, Suriname.

T

ARGET AREA

AND POPULATION

Paramaribo and its suburbs (bounded by two roads and two water- courses, namely the Roblesweg to the North, the Saramacca Canal to the South, the Suriname River to the East, and the Fourth Rijweg to the West) have a total area of about 70 square kilometers and a population of about 130,000 peo- ple living in 40,000 residences. The ter- rain is flat and swampy. Many of the houses are raised on pillars and have ex- tensive roof gutter (eavestrough) systems because of the high rainfall (an average of 221 cm per year during the period

1931-1960). AedeJ aegypti larvae have

commonly infested the roof gutters (l),

which are difficult to reach and treat with insecticides, and have also found plenty of breeding sites at ground level such as drums, tins, discarded tires, and plant pots.

aegyptz’ premises index in June 1982 was 24.7% (2).

l2

QUIPMENT

AND INITIAL PLANS

Spraying was carried out by personnel of the Anti-Yellow Fever Cam- paign (A.G.C.) using two truck- mounted Leco ULV cold aerosol genera- tors, one of them a model HD with flowmeter control and the other a model MD with constant volume control. The insecticide used was a 95% ULV mala- thion concentrate (Southern Mill Creek Products, Miami, Florida). The mass me- dian diameter of spray droplets, sampled on siliconized slides, was 16.4 microns for the HD and 12.4 microns for the MD.

A calibration curve of the in- secticide flow rate for each sprayer was prepared by detaching the insecticide line from the spray head and measuring the emission rate at a range of flowmeter settings. The sprayers were flushed with methylated spirits after use.

The aim was to spray both sides of every street in the area twice, with a one-week interval between the two sprayings. It was estimated from maps that there were 552 km of streets in the area, so spraying both sides of every street twice would require 2,208 km of driving.

Spraying was scheduled for four hours each evening (1800-2200 hours) on five evenings per week (Mon- day through Friday). Early-morning spraying was ruled out because of rush- hour traffic and closed windows. The spray routes for each evening’s work were marked on one of the A. G. C . zone maps and given to the crews (one driver and one spray operator for each truck) in ad- vance. The crews were told to drive at 15

km per hour while spraying, which would theoretically have allowed each crew to spray 60 km each evening. This could not be done, however, because of travel between zones, breakdowns, and other problems.

According to data supplied by the Meteorological Service of the Minis- try of Public Works and Transport, aver- age night winds prevailing from 1800 to

0600 hours in Paramaribo should never

have been above the limit (4.5 meters per second) for ULV spraying, but the crews were ordered to stop spraying in the event of strong wind or rain.

Publicity for the campaign, arranged by the Public Health Bureau’s Health Information and Education Sec- tion, consisted of newspaper articles, ra- dio and television announcements, and leaflets. The latter were delivered to each household by A.G.C. personnel one or two days before the first spraying. People were asked to leave their windows open during spraying, and also to get rid of potential mosquito breeding sites on their property.

D

OSE SELECTION

Some dosages of malathion and fenitrothion used as ground ULV sprays against A. uegyptz’ by previous workers are shown in Table 1. The dosage (D) applied in ml of active ingredient per km travelled may be calculated from the formula

D = 0.6FC V

296

TABLE 1. A comparison between the insecticide dosages (of active ingredient) used in the 1982 Paramaribo campaign and those used or recommended elsewhere. Fenitrothion was used in Paramaribo (1978) and in the work described by Sgnchez et a/.(S); ma- lathion was used in all other cases.

Source of data or campaign site Echevers et al. (6) Sanchez et al. (8) Giglioli et a/. (3) Cyanamid Corporation (7) Paramaribo, 1978

Paramaribo, 1982, weeks 1-3 Paramaribo, 1982, weeks 4-6

a Assuming a swath width of 91 m (300 ft).

Active Active Vehicle Emission ingredient ingredient

speed rate applied applied (km/hr) (ml/min) (ml/km) (ml/hay 16 321 35 IO-15 F!! 342-513 37-56

16 104 370 41 16 120 428 47 15 90 342 37 15 120 456 50 15 237 901 99

where F is the insecticide flow rate in ml aegypti in buildings using a dosage of per minute, C is the concentration of in- 321 ml/ km on the street outside, which secticide in the formulation (95 % in this is equivalent to only 35 ml/ ha or one- case), and V is vehicle speed in km per sixth of the lowest dosage recommended

hour. by Chow et al. (4).

To express D in ml per hect- are, it is necessary to estimate the swath width; so in this case the formula be- comes

A test area near the center of Paramaribo was sprayed with feni- trothion at 342 ml/km for four months in 1978. The premises index was greatly reduced, but it is not certain how much this was due to the ULV spraying because larviciding was done in the area as well.

where W is the swath width in meters. Giglioli and Lesieur (3) and some other authors have assumed that the swath width is about 91 m (300 ft); but since the actual dispersion and dosage depend on wind speed and direction, it appears better to express the dosage applied in ml per km of road.

Chow et aZ. (4) have recom- mended using 220-430 ml/ha of mala- thion, and the U.S. Public Health Ser- vice (5) has suggested 220 ml/ha. On the other hand, Echevers et ad. (6) in Pan- ama reported good kills of caged A.

The malathion dosage that we chose was 456 ml/km, produced at an emission rate of 120 ml/min at a vehicle speed of 15 km / hr. This is the maximum rate for ground ULV spraying recom- mended by the leading manufacturer of malathion (7), and is equivalent to 50 ml/ha if the swath width is 91 m. At the end of week 3 the dosage was nearly dou- bled to 901 ml/km (237 ml/min at 15 km/ hr) because of the poor results of the frost ovitrap evaluation (see below).

ered on the map. The resulting dosages would be 72 ml/ ha per treatment with a linear dosage of 456 ml/km and 142 ml/ ha with a linear dosage of 901 ml/km. These latter dosages are higher because some blocks, especially in the older resi- dential areas, were less than 182 meters wide. If the swaths really were 91 meters wide, they overlapped in the middle of such blocks.

T

ESTS WITH

CAGED MOSQUITOES

BEFORE THE CAMPAIGN

In order to determine the de- sired swath width and the lowest effec- tive dosage, 15 tests were conducted from February to April 1982 using labo- ratory-reared, sugar-fed, malathion-sus- ceptible A. aegypti females l-14 (usu- ally l-8) days old. These insects were placed in cages covered with plastic mos- quito-screen that were hung at a height of 1 meter from stakes on the Bureau of Public Health grounds at various dis- tances from the road (the Rodekruis- laan). For each test the spray truck made one pass northeastwards along the road. Control cages of mosquitoes were hung on the grounds of the Centraal Laborato- rium, across the road and upwind from the Bureau of Public Health building. Half an hour after spraying, the cages were brought in and the mosquitoes were transferred to clean containers. Mortality counts were made at 12 and 24 hours after spraying.

During these tests it became apparent how strongly the dispersal of the spray depended on the wind. When the air was still, the truck left a trail of spray about 4 m above itself and 4 m to the left; this dispersed with the next gust of wind, not always in the desired direc- tion.

Some of the results are shown in Table 2. In only two of the test runs

It was found that the contam-

(11 and 12) were there high kills in the treated cages and low kills in the control cages. In six other runs (l-d, 13, and 14)

kills in both the treated and control cages were low, probably due to unfavorable winds. In the seven remaining runs (not shown in Table 2), kills in both the treated and control cages were high, be- cause of contamination of the cages and possibly because of insecticide drifting into the control area. Contamination of the cages was confirmed by keeping A. aegypti females in them in the labora- tory; 40% died within 24 hours in some cases.

ination could be removed or rendered harmless by boiling the cages for 30 min- utes in water with a little detergent.

It was not possible to draw any firm conclusions about dosage and swath width from these tests, except that a dosage of 396 ml/km appeared to be just as effective as 1,980 ml/km up to 60

m from the road, but less effective at 90 m (see the results of test runs 11 and 12).

Rx

SULTS

g

The campaign began on 4 May in Paramaribo and was completed there by 23 June, after 37 evenings’ work by the two sprayers. It had been esti- mated that there were 552 km of roads in

3

the sprayed area, so that spraying both 8 sides of each road twice should have in- E volved travelling 2,208 km. The trucks

actually drove 2,789 km, however, be- 5 cause of connecting journeys between . zones and travel from the A. G. C. yard to the evening’s work area and back

4

(Table 3). 5

TABLE 2. The resufts of spraying 95% malathion from Leco ULV cold foggers at laboratory-reared A. aegypti females in cages one meter above ground outside the Bureau of Public Heafth building in Paramaribo in 1982. The sprays were applied from 1845 to 1940 hours, when temperatures were 26-28°C relative humidity was M-95%, and wind speeds were O-4 meters per second. The swath width was assumed to be 91 meters for purposes of calculating the dosage in ml/ha. No resufts are shown for test runs 5 through 10 or for run 15 because of high mortality among the control mosquitoes.

% kill 24 hours after exposure (No. tested in brackets) Dosage (active

Truck Flow ingredient) Treated, m from road Test speed rate

run Date (km/hr) (ml/min) ml/km ml/ha Controls 15 30 60 90 .l20 Leco model HD:

1 23 February 16 92 324 36

1 i

(Zj3 co, (4:)

(5:) (490) CO, 2 23 February 16 186 666 73 CO, 3 26 February 9 210 1,260 138

i L

co, (5;) (;I.; (3; 2.2 -

(2;)

(3:!1 (3fj4 (45) (45) (0) 2.3 4.0 0.0 - 4 26 February 6 210 1,890 208 (29) (44) (25) (46) (0) Leco model MD:

11 1 April 15 104 396 44 98.0 97.8 98.1 62.5 - (5Tjg 100 (49) 100 (45) 100 (54) (48) 95.6 (0) - 12 1 April 15 521 1,980 218 i ‘! (45) (46) (45) (46) (0) 13 7 April 15 104 396 44

1 r (4:)

Co, (Z)” (3ij” (4ij8 (4fj4 14 7 April 15 179 675 74 i) $j4 (4ij” (4ij5 (4Zj2 TABLE 3. A summary of spray activiis (blocks sprayed, hours worked, kilometers driven), the amounts of insecticide applied, and the amounts of gasoline consumed by the sprayers.

Insecticide used

Spray activities Gasoline Liters per km

Blocks Hours Kms Liters Liters Liters Liters Weeks sprayed worked driven used per hour Actual Expected used per hour

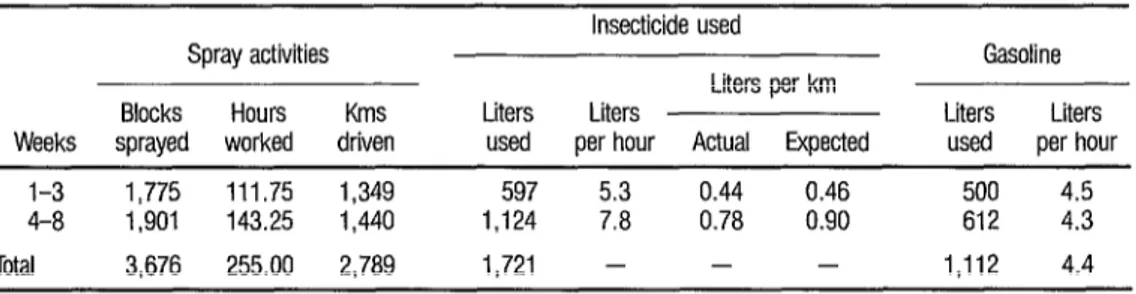

l-3 1,775 111.75 1,349 597 5.3 0.44 0.46 500 4.5 4-a 1,901 143.25 1,440 1,124 7.8 0.78 0.90 612 4.3 Total 3,676 255.00 2,789 1,721 - - - 1,112 4.4

The pickup trucks were diffL cult to maneuver in side streets, most of which were unpaved, and about two hours were lost each week because the

trucks broke down or got stuck in the mud.

The flow of insecticide was shut off while the truck passed through streets that had already been sprayed,

lower than expected, especially in weeks 4-S (237 ml/min = 14.2 l/h). This sug- gests that the flow rate calibration may have been inaccurate.

The effectiveness of the spray at a dosage of 456 ml/km was evaluated by cage tests on 19 May using sugar-fed, laboratory-reared A. uegypti females at four premises on a suburban block (South of the Verlengde Molenpad and East of the Engelslootstraat). The cages were placed inside the houses at these lo- cations, were put in the roof gutters, and were hung from 1 m stakes in the yards. The results are shown in Table 4. It rained heavily just before the test, at

1845 hours, and some mosquitoes in the

open were drowned, in both the treated and outdoor control cages-the latter on the grounds of the Centraal Laborato-

rium. There was no mortality among mosquitoes in the control cages that stayed inside the laboratory throughout the test period; but there was high mor- tality among those in the cages inside the houses on the sprayed block, which can be attributed to the spraying.

The effectiveness of the spray- ing was also evaluated twice by ovitrap tests. In the first evaluation, ovitraps were placed at 6 1 premises close to the city cen- ter (in the 1978 UIN test area), at intervals

beginning 10 days before the fust spray- ing and continuing until seven days after the second. As may be seen in ?gble 5, after both the first and second sprayings there was about a one-third reduction in

TABLE 4. Morfalii among laboratory-reared A. aegypfi females caged af four premises on a subur- ban block sprayed af 1900 hours on 19 May with malathion from a Leco HD cold fogger at a dosage of 456 ml/km.

Number Total % dead exposed killed Control mosquitoes (unsprayed):

inside the laboratory 0 33 0.0 Outdoors at the Centraal Laboratorium 6 27 22.2 Test mosquitoes (on the

sprayed block)

Indoors, ground floor, front 71 73 97.3 ,I ground floor, back ;: 29 100.0 n first floor 62 96.8 Indoors, subtotal 160 164 97.6 Outdoors in yard (1 m above ground)

10 m from road 90 91 98.6 20 m from road 59 60 98.3 30 m from mad 40 43 93.0 40 m from road 15 16 93.8 Outdoors in yard, subtotal 204 210 97.1 In roof gutters (2-3 m above ground)

TABLE 5. First ovftrap evaluation, old ULV test area, Paramaribo, May 1982. Two ovitraps were placed at each of the test premises (there being one to three premises per block covered). The malathion dosage applied was 456 ml/km.

Paddles Date Date put out taken in

Number of traps

Mean no. of Number % eggs per trap with eggs with eggs with eggs 3-4 May 6-7 May 115 37 32.2 32.5 6-7 May 10 May 110 48 43.6 31.9 First spray IO May

11 May 14 May 115 31 26.9 20.8 14 May 17 May 117 47 40.2 32.6 Second spray 17-18 May

19 May 22 May 113 32 28.3 29.3 22 May 25 May 116 46 39.7 24.7

the percentage of ovitraps with A. aegypti eggs and a similar reduction in the mean number of eggs per trap for the first three days. However, in the period from day 4 to day 7 after each spraying, the numbers of eggs deposited were found to have re- turned to prespray levels. It was because of these poor results that we decided to double the dosage to 901 ml/km from the beginning of week 4.

The second evaluation used ovitraps at 60 premises in a residential suburb to the west of the city (A.G.C. zone van Brussel, blocks 1067-1096). For the first three days after spraying there was again a reduction of about one-third in the percentage of positive ovitraps, and also in the mean number of eggs per trap (‘Exble 6), but both indices had re- turned to prespray levels by the fourth to the sixth day after spraying. A very simi- lar reduction and rapid recovery was seen after the second spraying.

TABLE 6. Second ovitrap evaluation, zone van Brussel, Paramaribo, May-June 1982. Two ovitraps were placed at each of the test premises, there being two test premises per block covered. The malathion dosage applied was 901 ml/km. b Paddles

3 Date Date Number Number % Mean no. of . eggs per trap 3 put out taken in of traps with eggs with eggs with eggs G 26 May 29 May 24 6 25.0 10.3 *+fj 29 May 31 May 24 6 25.0 14.0

u

Q 31 May 3 June 110 29 26.4 23.4 8

2 4 First June spray 3 s

June 7 June 115 19 16.5 13.6 7 June 10 June 116 25 21.6 21.2 Second spray IO June

11 June 14 June 120 13 lo.8 22.2

D

ISCUSSIONAND CONCLUSIONS

We had not expected the campaign to produce a long-term reduc- tion in the A. aegypi population, be- cause larvae and eggs were not attacked, but we had hoped to reduce the adult population for about two weeks in order to stop dengue transmission. The results of the tests with caged mosquitoes sug- gested that the spray would kill most A. aegyph females up to at least 40 meters from the street, but the ovitrap results indicated only a slight reduction in the egg-laying population, and for only three days or so after spraying. The fe- males which laid eggs during the first three days after spraying must already have been adults at the time of the spray- ing, because there was too little time for them to have emerged from their pupae, fed, and matured eggs (egg maturation alone takes two days).

Ovitraps probably give a bet- ter indication of the effects of spraying on wild mosquito populations than do kills of caged mosquitoes. That is be- cause cages force the mosquitoes to stay where they might not normally rest; and, conversely, the mesh may give some un- natural protection against the spray.

The UIY spray campaign had no apparent effect on A. aegypi larval infestation rates or on dengue incidence. Thus, the malathion ULV sprayings at dosages of 456 and 90 1 ml/ km produced only a slight reduction in the population of A. aegypti adults for not more than three days. In Trinidad (g), malathion from a truck-mounted ULV sprayer at

460 ml/km was even less effective against the A. aegypti population than in Suriname.

Evidence is also accumulating (10 and references therein) that mala-

thion ground ULV sprays at dosages of

360-420 ml/km are not adequate for

suppression of urban C&ex populations in the United States.

It should be possible to in- crease the kill by increasing the dosage or by using a more potent insecticide, but more experiments are needed to confirm this. The maximum output of the Leco sprayers used is 600 ml per minute, which is equivalent to 2,280 ml/km (or

250 ml/ha ifthe swath width is 91 m) at a vehicle speed of 15 km per hour, so the dosage could only be increased further by driving slower, thereby increasing the spraying time required.

With a vehicle speed of 15 km

per hour, it took seven and a half weeks to spray Paramaribo twice with the per- sonnel, equipment, and transportation available-a pace too slow to stop a den- gue epidemic. During the seven and a half weeks required, infected people and mosquitoes could move from a zone not yet sprayed to one already sprayed. It would be possible to finish the campaign faster with more sprayers, but these can- not be recommended until the ground ULV system has been shown fully effec- tive on a small scale, and until aerial UIY

spraying has been reconsidered. E In August 1981 I estimated l? that it would take only 2.4 flying hours 3 to spray greater Paramaribo once with a G small aircraft (Grumman Ag-Cat), as cl compared to 160 hours needed for spray- ? ing it with a truck, and that the costs of 8 aerial spraying would be only slightly

higher. The campaign with the truck- 3 mounted sprayers actually required 25 5 g spray-hours for the two applications, or

12 7.5 hours per application-faster than 5 . the time estimated but still much slower

than aerial spraying would have been. I E 2

therefore would still recommend using aircraft rather than trucks for emergency ULV spraying of Paramaribo in the fu- ture. In that event, the truck-mounted sprayers could still be useful for spraying smaller areas and for nonemergency spraying once the most efficient insecti- cide dosage and spray schedule have been determined. An even better solu- tion to the problem would be to prevent emergencies by eliminating the A. ae- gypti breeding sites.

A

CKNOWLEDGMENTSI wish to thank Mr. M. J. Hoevertsz , PAHO /WHO Technical Offi- cer in Suriname, for assistance in plan- ning the campaign; personnel of the A.G.C., under the supervision of Mr. R. Van Hetten and Mr. B. Kalicheran, for help with the field evaluations; Dr. B. F. J. Oostburg, Director of the B.O.G., for

permission to publish this report; and the late Dr. M. E. C. Giglioli, Director of the Mosquito Control and Research Unit, Cayman Islands, for comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

S

UMMARY In an attempt to stop an epi- t3 co demic of dengue , the City of Paramaribo 2 was sprayed in May and June 1982 with.

3 95 % malathion from truck-mounted ul- % tralow volume (ULV) sprayers. The entire .g city, with an area of 70 square kilometers

PI

a a and 552 kilometers of roads, was sprayed

2

twice on 37 evenings spread over seven and a half weeks by two sprayers working four hours each evening (1800-2200

hours), there being a one-week interval between the two sprayings in each zone.

During the first three weeks of the campaign a dosage of 456 ml ac- tive ingredient per km of road (5 o ml/ha if the swath width was 91 m) gave high kills of Aedes aegypti adults caged in- doors and outdoors on a sprayed block; but ovitrap results showed only modest reduction of egg-laying, and even that for only about three days after the spray application. The dosage was therefore in- creased to 901 ml/km (99 ml/ha) in weeks 4-7, but in a second test area the number of positive ovitraps was again re- duced only modestly for a short period. It thus appears that neither dosage was adequate to suppress the adult A. ae- gypi population, and also that the method of application was too slow to stop the targeted dengue epidemic.

Rx

FERENCESTinker, M. E. Aedes aegyptz’ larval habitats in Surinam. Bd Pan Am Health Organ 8:293- 301, 1974.

Knudsen, A. B. Aedes aegypti and dengue in the Caribbean. Mosquito News 43:269-275,

1983.

Gi lioli

In P ormatton on Adulticides against Aedes ae- ‘. M. E. C., and J. E Lesieur. Practical gypti-borne Epidemics. Un ublished docu- ment. Mosquito Control an a Research Unit, Cayman Islands, 1977, 15 pp.

Chow, C. Y., N. G. Gratz, R. J, Tonn, L. S. Self, and C. P Pant. The Control of Aedes aegypti-borne Epidemics. Unpublished docu- ment WHO/VBC/77.660. World Health Or- ganization, Geneva, 1977.

United States Public Health Service. Biology and Control of Aedes aegypti. Vector Topics No. 4. Centers for Disease Control; Atlanta, Georgia, 1979, 68 pp.

ground level in Panama City. B&J Pan Am Health Organ 9~232-237, 1975.

7 Cyanamid Corporation. Modem Mosqzlito ControL (thi7dedition). Princeton, New Jersey,

1979932 pp.

8 Motta Sanchez, A., R. J. TOM, L. J. Uribe, and L. B. Calheiros. A Comparison of Several Insecticides for the Control of Aedes ae in Villages in Colombia. Unpublished d ocu- y&i ment WHOIVBC176.623. World Health Or- ganization, Geneva, 1977, 33 pp.

l%lic~mye~tis

in the United

states, 19754984

9 Chadee, D. D. An evaluation of malathion in ULV spra ing against caged and natural popu- lations o Y Aedes aegypti in Trinidad, West In- dies. Cahien ORSIOM, se& Entomologie m&&cal’e et Parasitologic 23 ~71-74, 1985.

10 Leiser, L. B., J. C. Beier, and G. B. Craig. The

effkacy of malathion ULV spraying for urban Cz!ex control in South Bend, Indiana. Mos-

qm~oNew.r42:617-618, 1982.

In contrast to the 1951-1955 period just before widespread use of polio vaccines in the United States, when the number of cases per year av- eraged 15,822, an average of only 15 cases per year were recorded during 1975-1979, and this average fell further, to nine cases per year, in 1980-1984.

Overall, 118 cases were recorded in 1975-1984 and classified as efther “epidemic,” “endemic,”

“imported,” or “immune-deficient.” Of these, IO (8%) were considered “epidemic,” being linked to another case or cases caused by wild poliovirus; 12 (10%) were imported by U.S. cft- izens; 11 (9%) occurred among people wfth prf- mary immunodeffciencies; and the remaining 85 (72%) were “endemic,” in that they were not epidemiologically linked to other cases. Examining this latter group, 71 of the 85 cases (60% of the total 118) were epidemiologically associated with vaccine use, 30 occurring among vaccine recipients and 41 among con- tacts of vaccine recipients. The remaining 14 cases (12% of the totaf) were not epidemiologi- tally associated with vaccine use; however, five of these cases yielded virus isolates that were definitively characterized as vaccine-related. It should also be noted that only three of 45 cases occurring during the 1980-1984 period were caused by viruses classified as wild by strain characterization of isolates (two of these three cases were classified as “imported” and one was classified as “immune-deficient”). An- other imported case was presumed on epidemi- ologic grounds to have been caused by wild pc- liovirus. All of the other rare cases of paralytic poliomyelitis reported in the United States dur- ing this period were associated with vaccine use.

source: United States Centers for Disease Control,

Morbidity and Mortality W&/y RepoH 35(11):180-