1

Track 7: MNEs, Governments, and Non-market strategies Competitive Paper

The Impact of Government Equity Investment on Internationalization:

The Case of Brazil

Abstract

We examine the impact of government equity ownership on the degree of internationalization of emerging market firms. Our analysis of 173 Brazilian publicly traded firms from 2002 to 2011 shows that the higher the equity held by the state through the state investment bank and the pension funds of SOEs and privatized SOEs, the higher the firm’s degree of internationalization. Firms in which the government shared control with families, and with both families and foreigners, had a higher degree of internationalization. Our findings underline the importance of the institutional context in explaining the internationalization of Brazilian firms.

Keywords

Business-government interactions; State ownership; Institutions in emerging economies; Internationalization; Ownership structure; Brazil

INTRODUCTION

What is the impact of minority state ownership on a firm’s degree of internationalization? As Cuervo-Cazzura et al. (2014) note, our theoretical understanding of the impact of these new forms of state ownership on internationalization is still limited. In this paper we investigate the effect of state ownership on the share of foreign sales in total sales in a sample of Brazilian listed companies. Brazil provides an interesting context. It is one of the BRIC countries and home to many well-known Multilatinas such as Vale, Embraer, and Petrobras. It has a long history of active state intervention in the economy, carried out in the past through fully or majority-owned state-owned enterprises (SOEs) (Trebat, 1983) and today through minority stakes taken in private and listed firms by the national development bank BNDES and by pension funds of SOEs and privatized SOEs (Inoue et al., 2013). As

2

in many other emerging markets, the economic policies of Brazil abruptly shifted from import substitution industrialization (ISI) through SOEs to the building up of “international champions” through minority stakes taken in private and listed firms. Hence Brazil is an interesting context to study the impact of the new varieties of state capitalism (Musacchio et al., 2015) on the internationalization of emerging country firms.

We argue that government stakes in a firm are likely to raise its degree of internationalization if (a) the policy of the government is to encourage internationalization, and if (b) the government can use its equity stakes to influence firm strategies. This in turn depends on the extent to which firms are dependent on the state for resources. In following sections we show how government policies in emerging markets have evolved from import substitution industrialization (ISI) through fully-owned SOEs to using minority stakes in private firms to push them to become “international champions”, and hence from discouraging the international expansion of domestic firms to encouraging it. At the same time the lowering of barriers to foreign competition has pushed domestic firms to switch from domestic diversification to international expansion. Hence we hypothesize that (1) the higher the government stake in a firm, the higher its degree of internationalization; (2) minority government ownership in family-managed firms, and in those where families, foreigners, and the state share control, will result in these firms having a higher ratio of foreign sales to total sales than other types of firms. Controlling for possible endogeneity, we find support for all of our hypotheses.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

Our dependent variable is a firm’s ratio of foreign to total sales (FSTS). Foreign sales are the sum of exports and of the local sales of foreign production subsidiaries. International trade theory, internalization theory (Buckley and Casson, 1976), transaction cost theory (Hennart, 1982; Hennart & Park, 1994) and the eclectic paradigm (Dunning and Lundan, 2008) have identified the factors that determine a firm’s optimal FSTS. There are at least two factors that may make a firm deviate from this optimum. One is the institutional context in which firms operate, specifically the policies followed by their home governments. The other is firm governance. Managers react to the incentives they receive from owners, who may differ in their preference for international expansion.

In the following pages we focus on these two factors. We first show how the policies followed by emerging market countries, which until the 1990s hindered the internationalization of domestic firms, are now nudging them towards greater internationalization. Brazilian firms with government stakes have been responsive to such influence since internationalization is in their interest, and since these stakes give them access to the resources they need to internationalize.

3

Up until the 1990s, many emerging markets pursued ISI policies under which domestic markets were protected from foreign competition by high trade barriers and restrictions on the entry of foreign firms. Governments actively intervened through price setting and extensive regulations (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008). They set up wholly-owned SOEs to remedy the inability of the local private sector to undertake large-scale projects with long economic life and substantial spillovers (Gerschenkron, 1962). In this highly protected and regulated environment, it made more sense for local incumbents to diversify into other domestic industries than to target foreign markets, since domestic diversification allowed them to capitalize on their ties with the government (Schneider, 2008). This resulted in an industrial landscape dominated by SOEs and by diversified private business groups, often under the control of families. Firms were relatively inefficient and well below their internationalization potential.

The failure of these policies led to two major changes in the 1990s. First, governments dismantled price controls, lowered tariffs, and liberalized the entry of foreign firms (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008). Second, they privatized their SOEs. Most governments allocated blocks of shares to domestic consortia so as to keep the privatized SOEs out of the hands of foreigners. In most privatizations governments retained minority shares, either directly or indirectly through development banks, other government institutions, and SOEs pension funds (Meggison and Netter, 2001). These privatizations, as well as the emergency takeovers of failing firms during financial crises, have resulted in a new type of state capitalism in which governments retain full or majority shares in a few SOEs but hold minority shares in a large number of privately-owned firms (Musacchio et al., 2015).

Under the old ISI policies, governments were opposed to foreign investments by domestic firms, because they thought such investments deprived the domestic economy of employment and investments (Wells, 1971). Government policies changed when they opened their economies to foreign competition. They started to build up domestic firms into international champions through the infusion of equity and the provision of subsidized credit and government contracts (Bremmer, 2009).

The deregulation of domestic markets in emerging markets and their opening to international competition forced domestic firms to make radical changes. When domestic markets were protected, it made sense for them to expand through domestic diversification, since their incumbent status gave them advantages over domestic new firms in entering new industries. Faced with international competition, many local firms have divested unrelated businesses, acquired competing domestic firms, developed and acquired new technologies, and started to expand abroad (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008).

The major structural reforms of the late 1980s thus ushered in a period of increased convergence in emerging markets between the home state desire to boost the internationalization of domestic firms and these firms’ interest in catching up on their internationalization potential. Most emerging markets are characterized by weak formal institutions, with the state controlling access to many resources,

4

including those that support internationalization. Having the government as an equity partner facilitates access to these resources. Along with Cuervo-Cazzura et al. (2014), we therefore predict that the greater the government stake in a firm, the greater its degree of internationalization. Wholly-owned or majority-owned SOEs are most likely to internationalize because both politicians and firm managers support such strategies. But, as Cuervo-Cazurra et al. (2014) remark, governments are less able to direct the behavior of firms which are indirectly owned through state development banks, sovereign wealth funds, and state pension funds. Such firms are more likely to make internationalization decisions based on financial objectives, and less likely to deviate from these to maximize non-business goals. Majority shareholders will demand a reasonable return on investment to meet their goals—SOE pension funds, for example, need to cover current pensions—and thus will go along if the firm’s survival requires international expansion. Having a government minority stake also helps them obtain resources needed for international expansion. Hence, along with Cuervo-Cazzura et al. (2014), we expect firms with minority state ownership to be more internationalized than firms without government ownership, but less internationalized than fully-owned SOEs. In the next section we recast this hypothesis in the Brazilian context.

Government equity stakes and firm internationalization in Brazil

The origin of many Brazilian SOEs can be traced to the ISI policies followed by the Vargas government (1930-1945). The 1950s saw the establishment of a national development bank, the Brazilian National Bank of Economic Development, BNDES. BNDES plays an active role in the financing of private companies and takes equity stakes in them through its investment subsidiary BNDESPAR (Musacchio and Lazzarini, 2014). In 2013 BNDES was responsible for about 21% of the total credit to the Brazilian private sector and for almost all long-term credit (Musacchio and Lazzarini, 2014). BNDES played a major role in the privatizations undertaken under the Collor (1990-92) and Cardoso (1995-2002) governments. Through BNDESPAR, it took direct minority stakes in privatized firms and helped form consortia which bid for blocks of shares. In these consortia it allied itself with private Brazilian firms, foreign investors, and SOE pension funds (Inoue et al., 2013). Since the beginning of the new millennium, the Brazilian government has also taken equity in private firms through BNDESPAR and the pension funds of current and former SOEs to help Brazilian firms increase their domestic market share and expand internationally. In 2007, for instance, BNDES took a stake in JBS, a Brazilian meatpacking firm, to help it acquire Swift Argentina. Today BNDES owns 20.6% of JBS, which is now the world’s largest meat processor (Blankfeld, 2011). The end result of the privatizations and of investments of this type is that today the Brazilian government, through BNDESPAR, other government agencies, and the pension funds of former or present majority-owned SOEs, has minority equity stakes in a large number of Brazilian firms.

5

In the preceding section we have argued that state ownership will have a positive influence on a firm’s degree of internationalization if (a) government policies favour internationalization and if (b) the government is able to influence firm policies in that direction. This in turn depends on the extent to which the firms themselves want to internationalize and the government can offer positive and negative reinforcements to support these strategies.

Since the mid-1990s, the policy of the Brazilian government has been to build up selected Brazilian firms into international competitors (Araujo, 2013; Kroger, 2012; Rocha, 2014; Silva, 2010). Government help has taken many forms. First, as we have seen in the case of JBS, BNDES has helped Brazilian firms to internationalize by providing equity to allow them to make foreign acquisitions. BNDES has also increased its financing of Brazilian exports (Araujo, 2013) and has offered guarantees for the large foreign infrastructure projects undertaken by Brazilian companies such as Odebrecht (Finchelstein, 2012). Lastly, the Brazilian foreign office has helped Brazilian companies make foreign acquisitions and win foreign contracts (Luce, 2008).

There is considerable evidence that the Brazilian government has been able to exert influence on the strategies of the pension funds of former and current majority-owned SOEs (Costa, 2012). Musacchio and Lazzarini (2014; 37) write that “because the government has voice in the management of state-controlled SOEs and these companies have a voice in the management of their pension funds, governments in Brazil…have been able to strategically use pension funds in their favour.” Hence, to measure the level of control the Brazilian government has over firms, we add to the stakes taken by BNDESPAR those taken by SOEs and other government agencies (for example the Brazilian states) and by the pension funds of present and former SOEs.

There are two main reasons why we would expect the Brazilian government to be able to use its equity stake to persuade Brazilian firms to internationalize. First, Brazilian firms are aware that they have to internationalize if they wish to successfully compete against their international rivals. They have leveraged their domestic market power to build up their global operations (Hennart, 2012). Second, Brazilian firms are eager to comply with the government’s wishes because government support is crucial. Having the government as equity partner provides (1) access to subsidized finance--BNDES lends at 6% vs. a 40% commercial bank rate (Alfaro and White, 2015); (2) access to fundamental and applied research, as most of it is done in government research centers (Amann, 2009); (3) help with logistics, which in Brazil is often deficient (Hennart, Sheng and Pimenta, 2015); (4) government support in trade and investment negotiations; (5) protection against government policy changes. All these reasons lead Nölke (2010: 11) to write that “it becomes obvious how strongly Brazilian companies are profiting from their close collaboration with the state.” Hence we would expect that having BNDES

6

and current and ex-SOE pension funds as minority owners is a great advantage for firms that want to internationalize.

In sum, the evidence shows that the Brazilian government has engaged in a policy of helping domestic firms internationalize. Through the minority stakes held by BNDES, by the pension funds of current or ex-SOE pension funds, and by those of other government entities, it has been able to nudge Brazilian firms towards greater internationalization because it is in their own interest and because it pays for them to heed government advice in light of the wide range of advantages that come from maintaining good ties with the government. Consequently:

Hypothesis 1: The higher the total equity held by Brazilian government institutions (BNDES, SOE pension funds, and other government entities) in Brazilian firms, the greater their degree of internationalization.

In what kind of firm is government equity likely to be most effective in expanding foreign sales? A striking feature of the ownership structure of Brazilian firms is the important role played by families (Aldrighi and Neto, 2007). Family-owned firms make up almost half of our sample and these firms are overwhelmingly family-managed. Kontinen and Ojala (2010), in their survey of the family firm internationalization literature, argue that two defining characteristics of family-managed firms are their reluctance to take in outside investors (because it would dilute family ownership and grant power to outside investors) and their unwillingness to hire external specialist managers (because they want to reserve top positions to family members) (Banalieva and Eddleston, 2011). Most scholars have argued that these two characteristics make it potentially more difficult for family firms to internationalize, as foreign expansion is said to require more funds than can be raised internally and specialized skills not available within families. Consequently many scholars argue that family management tends to reduce a firm’s degree of internationalization (Graves and Thomas, 2006).

There are, however, arguments to the contrary. In family-managed firms, owners are also managers. The minimization of principal-agent conflicts should result in higher efficiency (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Family firms tend also to have a long-term perspective because families have their reputation and much of their wealth invested in the firm and typically want to safeguard it for future generations (Miller and LeBreton-Miller, 2005). This long-term perspective allows them to justify the significant investments that may be needed to develop foreign sales. While we might expect private family firms to experience financing constraints when internationalizing, family firms which are listed and in which the government has a substantial stake may in fact behave differently. Listed family firms have opened themselves to non-family investors, and hence may not suffer from the same capital shortage and may not exhibit the same conservatism than non-listed family-managed SMEs. In an environment like Brazil, family-managed firms that share control with the government can enlist the

7

support of the state for their internationalization strategies, as shown by JBS, which has plants in 24 and sells in more than 150 foreign countries (JBS, 2015). This leads us to our second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Joint control by families and by the Brazilian governments increases the degree of internationalization of Brazilian firms.

In Brazil, foreigners make up a second important group of owners (Aldrighi and Neto, 2007). In our sample they were dominant shareholders in 8.3% of all observations. Bhaumik, Driffield and Pal (2010) argue that foreigners usually have better knowledge of international opportunities and better governance practices than domestic firms, and hence that firms in which they have a stake should be more internationalized. They find that this is the case in Indian family firms. We are interested in finding out the impact of government ownership in listed firms where foreigners and government share control. In Brazil, many of these firms are in finance and public utilities, and we have excluded them from our sample. We have also excluded firms which are more than 50% owned by foreigners. In many of the firms in our sample where foreigners are the dominant shareholders, the foreign share is held by private equity and investment funds. Ownership of ALL, for example, is shared by the Brazilian government (through BNDESPAR, PREVI, the pension fund of Bank of Brazil employees, and FUNCEF, the pension fund of Caixa, a government-owned bank) and foreign private equity and investment funds that together hold more than 20% of the firm’s voting shares. It is therefore possible, but not highly likely, that in the Brazilian case government equity investment in foreign controlled firms will increase their degree of internationalization:

Hypothesis 3: Brazilian firms in which the Brazilian government shares control with foreign investors will have a higher degree of internationalization.

If we expect family firms that share control with the government to have a higher degree of internationalization than firms which do not have a significant government equity stake, then it is logical to expect that firms in which control is shared between the government, families, and foreigners should also have a higher degree of internationalization. Hence our fourth and last hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Brazilian firms in which the Brazilian government shares control with family firms and foreign investors will have a higher degree of internationalization.

DATA AND METHODS

Sample and Data

We selected all Brazilian firms listed on the São Paulo Stock Exchange (BM&FBovespa) between 2002 and 2011 that reported data on their foreign sales (zero or positive) and their ownership

8

structure. We excluded financial firms, public utilities, and firms more than 50% owned by foreigners in a specific year. We removed firms in which yearly values for return on assets and leverage were three standard deviations above and below the mean. Because of missing information on foreign sales, especially in the early years, and as a result of mergers, acquisitions, bankruptcies and delisting, we ended up with an unbalanced panel sample of 956 firm-year observations.

Financial data were collected from the Economatica® database. Information on foreign sales (both exports and local sales of foreign subsidiaries) was obtained from Bloomberg and ThomsonOne and was supplemented by consulting the annual DFP – Demonstrações Financeiras Padronizadas and

Formulários de Referência. Ownership structure was obtained from the Formulários de Referência and

the Informativos Anuais available at the Comissão de Valores Mobiliários.

Our dependent variable is a firm’s ratio of foreign sales to total net sales (FSTS). Foreign sales consist of exports and the local sales of foreign subsidiaries. According to Sullivan (1994), FSTS is the most commonly used indicator of internationalization. Oesterle et al. (2013) found that using FSTS rather than multidimensional variables of internationalization did not change their results.

Our main exploratory variable is the total government stake taken in a firm (GOVERNMENT_ %), which is the sum of the voting shares held by (1) BNDESPAR (BNDES_%); (2) the pension funds of Brazilian SOEs and former SOEs (PFUNDS_%); (3) and government agencies and government wholly-owned banks and enterprises (OTHERGOV_%). We also investigate the separate influence on foreign sales of these three types of government stakes.

We also enter a firm’s family stake (FAM_%) and foreign stake (FOR_%). FAM_% is the percentage of a firm’s voting shares owned by families and FOR_% that owned by foreign investors. Because of the pyramidal structure common in Brazil (Aldrighi & Neto, 2007), we considered both direct and indirect stakes (i.e. stakes held through other firms and funds).

We also created dummy variables to represent instances of shared stock ownership—see Table 1. Based on previous studies (Bhaumik et al., 2010), we assumed that owning more than 10% of the total voting shares gave some degree of control. Moreover, Brazilian law allows shareholders who own more than 10 percent of a firm’s voting shares to ask for a seat on the board of directors.

In almost half of the observations in our sample families are the dominant shareholders. Firms in which families share the control with foreigners make up the second largest category (12.7% of the observations in our sample), followed by firms with dispersed ownership (10.9%), firms controlled by foreigners (8.3%), and firms controlled by the government (7.3%). Firms with the highest FSTS are those in which the following shareholders are dominant: (1) BNDES and other government investors

9

(FSTS = 83.5%); (2) BNDES, other government investors, and foreign investors (FSTS = 80.4%); (3) SOE pension funds and foreign investors (FSTS = 70.4%; (4) BNDES, families, and foreign investors (FSTS = 45.2%) ; (5) BNDES and SOE pension funds (FSTS = 42.5%) ; and (6) BNDES and families (FSTS = 37.8%).

We entered the following control variables:

(1) Ownership Concentration (OC), measured by the percentage of shares with voting rights held by the largest shareholders. We took into account formal shareholder agreements, using information from the firm’s Annual Reports.

(2) Cash (CASH), measured by the ratio of cash and equivalents to the book value of total assets. (3) Firm size (SIZE), measured by the natural logarithm of the book value of total assets.

(4) Firm Age (AGE), measured by the natural logarithm of the number of months since the date of incorporation reported in the CVM registration forms.

(5) Leverage (DEBT), measured by the book value of gross debt over total assets.

(6) Return on Assets (ROA), measured by net income divided by the book value of total assets. (7) Initial degree of internationalization (FSTSFirst). To account for the possibility that the

Brazilian government chooses to invest in firms that are more internationalized, we entered the firm’s first valid FSTS observation (FSTSFirst). As another way to control for endogeneity, we also enter the previous year’s FSTS (FSTSt-1)

Estimation Approach and Econometric Models

Government agencies such as BNDES and SOE pension funds do not randomly select the firms in which they invest. Hence using OLS to assess the impact of government equity investment on internationalization may suffer from endogeneity problems because unobservable factors may affect both the likelihood of state ownership in a firm and its level of internationalization, making it difficult to establish a causal link (Inoue et al., 2013). To handle this problem we therefore follow these authors and use a panel regression with time-invariant firm-specific effects and year-fixed effects (

the firms in

our sample experience significant year-to-year changes in government ownership over our

period of analysis).

Because a firm’s level of internationalization is likely to be industry-specific (Hennart and Park, 1994), we clustered standard errors at the industry level, making sure that there were at least three firms in each industry. Because our dependent variable FSTS varies between zero and one, and because 447 out of 956 observations in our sample (46.7%) have zero values, we use a Tobit panel truncated at zero. Following Bhaumik et al. (2010), we lag our independent and control variables one year. Correlation coefficients between the variables are below levels at which multicollinearity

would be a problem.

10 RESULTS

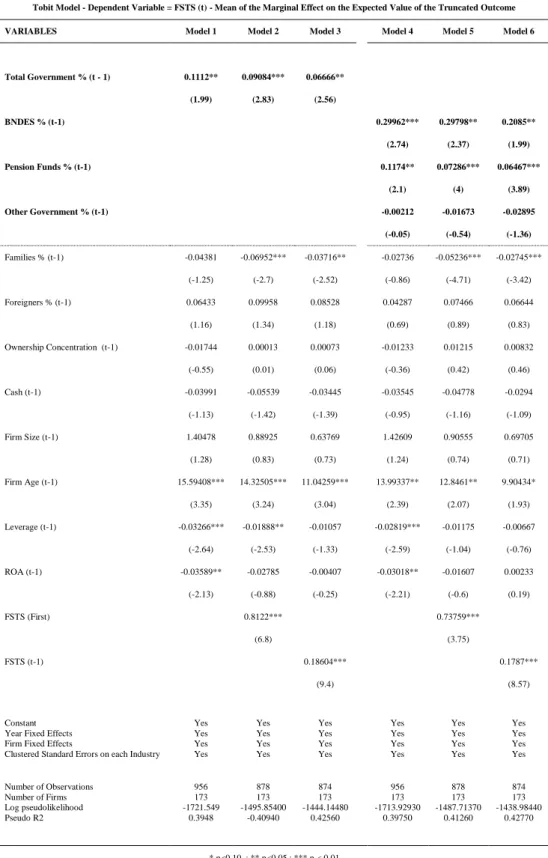

In Table 2 we evaluate the influence of government equity stakes on internationalization. The coefficients show the marginal effect of the variable on the expected value of FSTS. Looking first at the control variables, AGE is positively related to the degree of internationalization. This is consistent with the findings of Floriani and Fleury (2012) for Brazilian firms, and more generally with the Uppsala model of gradual internationalization (Johanson and Vahlne, 1977). The stake taken by families,

Families % (t-1),

tends to reduce the extent of internationalization when we control for past internationalization (in models 2, 3, 5 and 6), while that taken by foreign investors, Foreigners % (t-1) has no significant impact on a firm’s FSTS. Turning now to our hypotheses, Models 1, 2 and 3 show a positive relationship between a firm’s FSTS and the total equity stake taken by the Brazilian state through the development bank BNDES, government agencies, SOEs, and SOE pension funds, as the coefficients of Total Government % (t-1) are all positive and statistically significant. These results support H1 which states that total government equity participation has a positive influence on the degree of internationalization of Brazilian firms. They are consistent with the results of Shamsuddoha, Ali and Ndubisi (2009), Wang, Hong, Kafouros and Wright (2012), and Zutshi and Gibbons (1998) in the case of Asian firms. The coefficient of Total Government_% (t-1) is 0.066 in model 3, which means that a one percent change in the equity taken in a firm by all government entities will result in a 0.06 increase in the firm’s percentage of foreign to total sales. When we split the total Brazilian government stake into its constituents, i.e. the stake taken by BNDES, by SOE pension funds, and by other government institutions (Models 4, 5 and 6), we find that government participation through SOE pension funds and through BNDES has a positive influence on internationalization, as the coefficients of Pension Funds %(t-1) and BNDES % (t-1) are all positive and statistically significant. The stake taken by other

state-owned agencies (Other Government % (t-1)) is not statistically significant.

In Table 3 we show the impact of government minority stakes on internationalization in firms in which they are combined with those of families and foreigners. To do this we use the dummy variables described in Table 1, which have a 10% cutoff. Hence, as shown in Table 1,

GOVERNMENT_D corresponds to the case of firms where the total government stake is greater than

10% while that of families and foreigners is less than 10%. Likewise, GOVERNMENT_FAMILIES_D corresponds to the case of a firm in which the total government stake and the stake held by families are both greater than 10%, and that held by foreigners is less than 10%, while

GOVERNMENT_FOREIGNERS_D corresponds to the case where the total government stake and the

stake held by foreigners are both greater than 10% and that held by families less than 10%. The omitted group are firms in which the government, the families and foreign investors own less than 10% of the voting shares, i.e. firms with dispersed ownership. Models 4, 5 and 6 of Table 3 also shows the results with a zero cutoff. In that case, GOVERNMENT_D corresponds to the case where the total government

11

stake is greater than zero, while those of families and foreigners are zero. Likewise

GOVERNMENT_FAMILIES_D then describes the case where the total government stake and the stake

held by families are both greater than zero, and that held by foreigners is zero, while

GOVERNMENT_FOREIGNERS_D then corresponds to the case where the total government stake and

the stake held by foreigners are both greater than zero with that held by families being equal to zero. The omitted group in this case is composed of firms in which the government, the families and the foreign investors do not have any direct or indirect voting shares. The coefficients show the means of the marginal effects of the variables on the expected value of FSTS.

Model 3 of Table 3 shows that the degree of internationalization is higher for firms in which the government is the dominant shareholder, that is when it is the only party with more than 10% of the shares. The impact of government ownership is particularly strong when the government allies itself with family firms: the coefficients of the GOVERNMENT_FAMILIES_D variable are positive and statistically significant at 1% in all models. They are also larger than those for the GOVERNMENT_D dummy at both a 10% and a zero cutoff. This supports H2 in which we hypothesized that firms under the joint influence of families and the government would be strong internationalizers. The size of the effect is significant, since the coefficient of GOVERNMENT_FAMILIES_D is 4.52 in Model 3, indicating that FSTS is 4.5 percentage points higher in firms in which the government and families own each more than 10% of the voting shares (and foreign investors less than 10%) than in the omitted category. FSTS is also higher in firms where the Brazilian government, families, and foreigners each own more than 10% of the shares, as the coefficient of GOVERNMENT_ FAMILIES_FOREIGNERS_D is positive and significant in Model 3. This provides support for H4.

The coefficient of GOVERNMENT_FOREIGNERS_D is only mildly significant in Model 3, showing that firms in which the government shares control with foreigners are not significantly more internationalized than firms with dispersed ownership. Thus our results provide weak support for H3. As we mentioned, the foreign owners of most of these firms are private equity and investment firms who may prefer that the firms in which they invest focus entirely on Brazil.1 Foreign owners are also less likely to be influenced by government equity as they are less dependent on government resources. As Table 3 shows, all the preceding results are unchanged when we use a zero percent cutoff (models 4, 5 and 6).

Robustness tests

We have seen that endogeneity poses a potential problem because the Brazilian government does not choose randomly the firms in which it wants to take equity. If it chooses to invest in companies

12

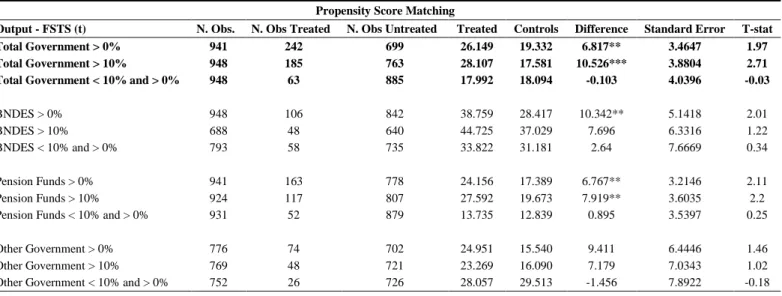

that already have a high degree of internationalization, this may lead us to erroneously conclude that it is government equity that leads to internationalization. To control for this, we use Stata’s propensity score matching program. This program creates comparable control groups of firms with characteristics similar to those in which the government has taken a stake (either through BNDES, SOE pension funds, or other government agencies). The firm-level characteristics considered are the industry to which the firm belongs, and firm size, ownership concentration, cash holdings, leverage, age and profitability. We then compare the level of internationalization in these two groups of similar firms when they differ in the level of government equity.

The results are presented in Table 4. They show that firms in which the government has an equity stake have on average a higher degree of internationalization than firms which have no government equity stake but are similar in terms of size, cash, leverage, and profitability, and belong to the same industry. This result is statistically significant at the 5% confidence level when using 0% ownership as threshold for total government stake and at the 1% confidence level using 10% as threshold for total government ownership. This suggests that any level of government ownership increases a firm’s degree of internationalization, but that the Brazilian government has a particularly strong influence on internationalization if its stake is above 10%. Table 4 also confirms our previous results that the impact of government equity on foreign sales is due to the investments of BNDES and to those of SOE pension funds. The impact of these two groups of government investors on internationalization is positive and statistically significant at the 5% confidence level while investments by other government agencies (for example by Brazilian states) have no impact on internationalization.

CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we investigated the impact of government ownership on the degree of internationalization of Brazilian listed firms. We hypothesized that the state will have a positive impact on a firm’s degree of internationalization if it favors internationalization and if through its equity stake it is able to influence firm strategies. This in turn depends on whether firm owners and managers want to internationalize and if having the state as a co-owner allows them to access critical resources useful for internationalization. We showed that all these conditions were met for most of the firms in our sample of Brazilian firms, and concluded that the larger the size of the government stake, and hence its influence, the higher the expected degree of internationalization to be. Using a panel of 173 Brazilian listed firms over the 2002-2011 period, and controlling for endogeneity, we found support for our hypothesis: the larger the total stake taken by the Brazilian government in a firm, the higher that firm’s ratio of foreign to total sales. Further investigation showed that the impact of government equity on internationalization was driven by that taken by the Brazilian government development bank, BNDES, and by those of the pension funds of SOEs and of privatized SOEs. We also found that government

13

stakes had a particularly significant impact on the internationalization of Brazilian family firms but not on those in which foreigners were the dominant shareholders.

Like any study, ours has some limitations. Because of data availability, we only considered listed firms. Our panel therefore excluded both firms which were fully owned by the government and purely private firms. The measure of internationalization which we had to use for lack of a better one, the ratio of foreign to total sales (FSTS), is also somewhat crude. It lumps together exports and foreign sales, and hence does not allow us to differentiate between firms that serve foreign customers through exports and those that serve them through foreign production facilities. Another limitation of FSTS is that it makes it impossible to differentiate between a firm that has a large volume of sales in a culturally close country and one which has the same level of foreign sales, but in a large number of culturally distant countries. We also only take into account the equity provided by BNDES, other government entities, and the pension funds of SOEs and ex-SOEs. Subsidized BNDES loans are an important component of government support for the internationalization of Brazilian firms and such loans may have had an independent effect. Lastly, this study focuses on Brazil, and further research will need to establish whether our results apply to other contexts.

In spite of these limitations, our study makes a number of interesting contributions. First, we contribute to the rather limited literature on the internationalization of Latin American firms. We show that their orientation towards foreign markets is correlated with the total level of state participation in their capital. Cuervo-Cazzura (2008) has pointed to the crucial role played by changes in home country institutional environments in the rise of Latin American MNEs, the Multilatinas. He argues that the major reforms undertaken by Latin American countries in the 1990s, the opening up of their economies to foreign competition and the privatizations of their SOEs, pushed domestic firms to internationalize. Our results support this view. They underline the importance of understanding the home-country institutional context if one wishes to make sense of the rise and development of emerging market firms. We document a radical change in the policies of emerging market governments towards internationalization. While under policies of industrialization through import substitution firms were discouraged from selling and investing abroad, governments in many emerging markets, and in Brazil in particular, have balanced out the opening of their countries to foreign competition with a policy of encouraging selected domestic firms to become global competitors. In Brazil this policy has taken the form of equity injections into private firms by BNDES and by SOE and ex-SOE pension funds. At the same time the government has used the minority stakes it has kept in the privatized SOEs to push them to internationalize. Starting in the 1990s, there has been a convergence between the policies of the Brazilian government and those of the managers and owners of the Brazilian firms striving to gain international stature so as to successfully compete with foreign rivals on the global stage. This explains why we find a positive and statistically significant relationship between the total size of the government equity stake in a firm and its share of foreign sales in total sales.

14

Our results also throw light on the new varieties of state capitalism described by Musacchio et al. (2015). They show that the Brazilian state has been able to implement its policies of internationalization through minority stakes taken in family-managed firms by its national development bank BNDES and by the pension funds of SOEs and ex-SOEs. This suggests that while privatizations have changed the modalities by which state control is exercised, they have not, at least in Brazil, changed its substance. The Brazilian state continues its developmentalist policies, albeit in a different form. Further research might investigate whether this is also the case in other countries that have undergone similar privatizations.

More generally, our research shows how a focus on emerging market MNEs may help improve extant theories of the MNE. These theories have tended to underplay the role of home country institutions, and especially of governments. This is in spite of considerable evidence that in many countries, even those espousing liberal views, the state intervenes to support national companies and to hinder foreign ones. To take a few examples, the British government in the late 1960s encouraged the merger of two British automakers to form a national champion, and when the firm nearly went bankrupt, nationalized it and subsidized it heavily. It also promoted the merger of British computer firms to form ICL, and took a minority share in the newly formed company. Both these efforts were unsuccessful, and the firms eventually ended up in foreign hands (Jones, 1996). The French government pursued similar policies in the computer field, and was similarly unsuccessful, but it was better at developing global competitors in aircraft (Airbus) and nuclear power (Areva). It would seem that rare are the cases of states keeping strictly hands-off policies when it comes to international competition, and this ought to be better reflected in our MNE theories.

Our research raises further interesting questions. While some attention has been paid to the role played by Sovereign Wealth Funds in financing international champions (e.g. Bremmer, 2009), we find little written on the role played by pension funds of SOEs and former SOEs. Our results suggest that the Brazilian state has been able to enlist the help of these pension funds to carry out its policies of stimulating the internationalization of Brazilian firms. It would be interesting to investigate whether this is particular to Brazil, or whether it is also the case in other emerging markets.

Finally, our findings also suggest a convergence between the policies of the Brazilian state and the strategies followed by firms in which the government has a stake. While we have no way to test it, we surmise that this may be due to the tight personal relationships that exist in Brazil between business leaders and the state (Nölke, 2010). Bremmer (2009) has argued that close ties between those who govern a country and those who run its enterprises tend to lead to poor economic decisions because the motivations for the decisions tend to be political rather than economic. We have documented that government equity stakes lead firms to internationalize, but we do not know whether the resulting level of internalization is optimal. The theoretical model we have sketched suggests that institutional

15

environment and firm governance may lead firms to systematically undershoot or overshoot the optimal level of internationalization. An interesting research question is whether the Brazilian government through its equity stake has led firms to overinvest abroad. In that case this would affect their overall profitability and the survival of their foreign subsidiaries. Future research might investigate whether this is the case, and whether there is a statistical relationship between a firm’s level of government equity and the performance of its international activities.

16 Table 1 – Ownership structure categories

Government is dominant shareholder

GOVERNMENT_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if GOVERNMENT_% > 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% < 10%

BNDES_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% < 10% and OTHERGOV_% < 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% < 10% PFUNDS_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% < 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% < 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% < 10% OTHGOV_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% < 10% and PFUNDS_% < 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% < 10% BNDES_PFUNDS_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% < 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% < 10% BNDES_OTHGOV_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% < 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% < 10% PFUNDS_OTHGOV_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% < 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% < 10% BNDES_PFUNDS_OTHGOV_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% < 10%

Families and Foreigners are dominant shareholders

FAMILIES_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if GOVERNMENT_% < 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% < 10% FOREIGNERS_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if GOVERNMENT_% < 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% > 10% FAMILIES_FOREIGNERS_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if GOVERNMENT_% < 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% > 10%

Government and Families are dominant shareholders

GOVERNMENT_FAMILIES_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if GOVERNMENT_% > 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% < 10%

BNDES_ FAM_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% < 10% and OTHERGOV_% < 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% < 10% PFUNDS_ FAM_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% < 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% < 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% < 10% OTHGOV_ FAM_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% < 10% and PFUNDS_% < 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% < 10% BNDES_PFUNS_FAM_ D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% < 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% < 10% BNDES_OTHGOV_FAM_ D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% < 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% < 10% PFUNDS_ OTHGOV_FAM_ D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% < 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% < 10% BNDES_PFUNS_OTHGOV_FAM_ D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% < 10%

Government and Foreigners are dominant shareholders

GOVERNMENT_FOREIGNERS_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if GOVERNMENT_% > 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% > 10%

BNDES_FOR_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% < 10% and OTHERGOV_% < 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% > 10% PFUNDS_FOR_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% < 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% < 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% > 10% OTHGOV_ FOR_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% < 10% and PFUNDS_% < 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% > 10% BNDES_PFUNS_FOR_ D (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% < 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% > 10% BNDES_OTHGOV_FOR_ D (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% < 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% > 10% PFUNDS_OTHGOV_ FOR_ D (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% < 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% > 10% BNDES_PFUNS_OTHGOV_FOR_ D (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% < 10% and FOR_% > 10%

Government, Families and Foreigners are dominant shareholders

GOVERNMENT_FAMILIES_FOREIGNERS_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if GOVERNMENT_% > 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% > 10%

BNDES_FAM_FOR_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% < 10% and OTHERGOV_% < 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% > 10% PFUNDS_FAM_FOR_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% < 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% < 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% > 10% OTHGOV_FAM_FOR_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% < 10% and PFUNDS_% < 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% > 10% BNDES_PFUNDS_FAM_FOR_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% < 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% > 10% BNDES_OTHGOV_FAM_FOR_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% < 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% > 10% PFUNDS_OTHGOV_FAM_FOR_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% < 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% > 10% BNDES_PFUNDS_OTHGOV_FAM_FOR_D_10% (t-1) = 1 if BNDES_% > 10% and PFUNDS_% > 10% and OTHERGOV_% > 10% and FAM_% > 10% and FOR_% > 10%

18

Table 2 - Impact of Government Equity Stake on Internationalization

Tobit Model - Dependent Variable = FSTS (t) - Mean of the Marginal Effect on the Expected Value of the Truncated Outcome

VARIABLES Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Model 6

Total Government % (t - 1) 0.1112** 0.09084*** 0.06666** (1.99) (2.83) (2.56) BNDES % (t-1) 0.29962*** 0.29798** 0.2085** (2.74) (2.37) (1.99) Pension Funds % (t-1) 0.1174** 0.07286*** 0.06467*** (2.1) (4) (3.89) Other Government % (t-1) -0.00212 -0.01673 -0.02895 (-0.05) (-0.54) (-1.36) Families % (t-1) -0.04381 -0.06952*** -0.03716** -0.02736 -0.05236*** -0.02745*** (-1.25) (-2.7) (-2.52) (-0.86) (-4.71) (-3.42) Foreigners % (t-1) 0.06433 0.09958 0.08528 0.04287 0.07466 0.06644 (1.16) (1.34) (1.18) (0.69) (0.89) (0.83) Ownership Concentration (t-1) -0.01744 0.00013 0.00073 -0.01233 0.01215 0.00832 (-0.55) (0.01) (0.06) (-0.36) (0.42) (0.46) Cash (t-1) -0.03991 -0.05539 -0.03445 -0.03545 -0.04778 -0.0294 (-1.13) (-1.42) (-1.39) (-0.95) (-1.16) (-1.09) Firm Size (t-1) 1.40478 0.88925 0.63769 1.42609 0.90555 0.69705 (1.28) (0.83) (0.73) (1.24) (0.74) (0.71) Firm Age (t-1) 15.59408*** 14.32505*** 11.04259*** 13.99337** 12.8461** 9.90434* (3.35) (3.24) (3.04) (2.39) (2.07) (1.93) Leverage (t-1) -0.03266*** -0.01888** -0.01057 -0.02819*** -0.01175 -0.00667 (-2.64) (-2.53) (-1.33) (-2.59) (-1.04) (-0.76) ROA (t-1) -0.03589** -0.02785 -0.00407 -0.03018** -0.01607 0.00233 (-2.13) (-0.88) (-0.25) (-2.21) (-0.6) (0.19) FSTS (First) 0.8122*** 0.73759*** (6.8) (3.75) FSTS (t-1) 0.18604*** 0.1787*** (9.4) (8.57)

Constant Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Year Fixed Effects Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Firm Fixed Effects Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Clustered Standard Errors on each Industry Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Number of Observations 956 878 874 956 878 874 Number of Firms 173 173 173 173 173 173 Log pseudolikelihood -1721.549 -1495.85400 -1444.14480 -1713.92930 -1487.71370 -1438.98440 Pseudo R2 0.3948 -0.40940 0.42560 0.39750 0.41260 0.42770

19

Table 3 - Impact of Ownership type on Internationalization

Tobit Model truncated at 0 - Dependent Variable = FSTS (t) - Mean of the Marginal Effect on the Expected Value of the Truncated Outcome

> 10% > 0%

VARIABLES Obs. Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Obs. Model 4 Model 5 Model 6

GOVERNMENT_D (t-1) 70 1.4732 2.03477 4.14117*** 57 1.31179** 2.60331*** 2.90773*** (0.86) (1.18) (2.87) (2.31) (3.14) (3.83) GOVERNMENT_FAMILIES_D (t-1) 64 3.36419*** 2.81862*** 4.51762*** 92 5.27575*** 5.93005*** 5.53048*** (3.25) (2.57) (3.35) (7.31) (5.6) (8.8) GOVERNMENT_FOREIGNERS_D (t-1) 24 1.19967 0.76894 2.95523* 19 -0.53196 -0.97698 -0.34487 (0.71) (0.44) (1.72) (-0.21) (-0.47) (-0.32) GOVERNMENT_FAMILIES_FOREIGNERS_D (t-1) 28 5.00788** 4.92482* 6.56277*** 82 4.57184** 6.28511* 6.14614** (2.24) (1.83) (2.97) (2.07) (1.93) (2.54) FAMILIES_D (t-1) 466 -0.35316 -0.5322 2.56525 365 2.09189** 3.02592*** 3.78709*** (-0.1) (-0.15) (0.83) (2.18) (2.58) (3.16) FOREIGNERS_D (t-1) 79 -1.64257* -2.8171*** -2.46809*** 76 0.32083 -0.76648 -1.86175* (-1.78) (-5) (-4.33) (0.16) (-0.47) (-1.82) FAMILIES_FOREIGNERS_D (t-1) 121 0.81391 2.20295 4.57328 191 3.30148*** 6.6766*** 6.41212*** (0.18) (0.48) (1.19) (5.19) (4.16) (3.92) Ownership Concentration (t-1) -0.0214 -0.01569 -0.00188 -0.02033 -0.01586* -0.00495 (-1.27) (-1.03) (-0.1) (-1.54) (-1.66) (-0.43) Cash (t-1) -0.04237 -0.05766 -0.03375 -0.03606 -0.05858 -0.03654 (-1.18) (-1.52) (-1.48) (-0.83) (-1.21) (-1.14) Firm Size (t-1) 1.57662 1.09426 0.72801 1.93992 1.3589 0.90831 (1.14) (0.78) (0.66) (1.56) (1.1) (0.93) Firm Age (t-1) 14.67363** 12.88133** 10.17314** 13.35125* 12.45735* 10.5105* (2.52) (2.38) (2.26) (1.91) (1.78) (1.95) Leverage (t-1) -0.02507** -0.01406 -0.00709 -0.03593*** -0.02721*** -0.01646* (-2.01) (-1.38) (-1.09) (-3.49) (-3.13) (-1.88) ROA (t-1) -0.03262 -0.02388 -0.00075 -0.04256** -0.03356 -0.00633 (-1.62) (-0.69) (-0.05) (-2.2) (-0.93) (-0.39) FSTS (First) 0.62309*** 0.48535** (3.43) (2.2) FSTS (t-1) 0.19997*** 0.19883*** (8.9) (9.93)

Constant Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Year Fixed Effects Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Firm Fixed Effects Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Clustered Standard Errors on each Industry Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Observations 956 878 874 956 878 874

Firms 173 173 173 173 173 173

Log pseudolikelihood -1728.9861 -1505.9179 -1447.2989 -1729.3877 -1504.3377 -1445.7549 Pseudo R2 0.3922 0.4054 0.4244 0.3921 0.406 0.425

20

Table 4 - Impact of government equity stake on internationalization

Propensity Score Matching

Output - FSTS (t) N. Obs. N. Obs Treated N. Obs Untreated Treated Controls Difference Standard Error T-stat

Total Government > 0% 941 242 699 26.149 19.332 6.817** 3.4647 1.97

Total Government > 10% 948 185 763 28.107 17.581 10.526*** 3.8804 2.71

Total Government < 10% and > 0% 948 63 885 17.992 18.094 -0.103 4.0396 -0.03

BNDES > 0% 948 106 842 38.759 28.417 10.342** 5.1418 2.01

BNDES > 10% 688 48 640 44.725 37.029 7.696 6.3316 1.22

BNDES < 10% and > 0% 793 58 735 33.822 31.181 2.64 7.6669 0.34

Pension Funds > 0% 941 163 778 24.156 17.389 6.767** 3.2146 2.11 Pension Funds > 10% 924 117 807 27.592 19.673 7.919** 3.6035 2.2 Pension Funds < 10% and > 0% 931 52 879 13.735 12.839 0.895 3.5397 0.25

Other Government > 0% 776 74 702 24.951 15.540 9.411 6.4446 1.46 Other Government > 10% 769 48 721 23.269 16.090 7.179 7.0343 1.02 Other Government < 10% and > 0% 752 26 726 28.057 29.513 -1.456 7.8922 -0.18

21 REFERENCES

Aldrighi, D. M., & Neto, R. M. (2007). Evidências sobre as estruturas de propriedade de capital e de voto das empresas de capital aberto no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Economia, 61(2): 129-152. Alfaro, L. and White, H. (2015). Brazil’s enigma: sustaining long term growth, Harvard Business School Case 9-713-040.

Amann, E. (2009). Technology, public policy, and the emergence of Brazilian multinationals, in L. Brainard and L. Martinez-Diaz, (Eds,), Brazil as an Economic Superpower: Understanding Brazil’s

Changing Role in the Global Economy. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Araujo, Tavares de, J. (2013). The BNDES as an instrument of long run economic policy in Brazil. Rio de Janeiro: Centro de Estudios de Integração e Desenvolvimento.

Arreola, M. (2014). The Effects of State Ownership in the Internationalization of Emerging

Multinationals. PhD thesis, Escola de Administraçao de Empresas de Sao Paulo.

Banalieva, E. & Eddleston, K. (2011). Home-region focus and performance of family firms: the role of family vs. Non-family leaders, Journal of International Business Studies 42(8): 1060-1072. Bhaumik, S. K., Driffield, N., & Pal, S. (2010). Does ownership structure of emerging market firms affect their outward FDI? The case of the Indian automotive and pharmaceutical sectors. Journal of

International Business Studies, 41(3): 437-450.

Blankfeld, K. (2011). JBS: the story behind the world’s biggest meat producer. Forbes May 9th, [ http://www.forbes.com/sites/kerenblankfeld/2011/04/21/jbs-the-story-behind-the-worlds-biggest-meat-producer]. Accessed September 10, 2015.

Bremmer, I. (2009). State capitalism comes of age. Foreign Affairs 88(3): 40-55.

Buckley, P. & Casson, M. (1976). The Future of Multinational Enterprise. London: Macmillan. Costa, Fernando Nogueira da. (2012). Capitalismo de estado neocorporativista. Texto para Discussão. Instituto de Economia da Unicamp. Campinas, nº 207. July.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2008). The multinationalization of developing countries MNEs: the case of multilatinas. Journal of International Management 14(2): 138-154.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., Inkpen, A., Musacchio, A., & Ramaswamy, K. (2014). Governments as owners: State-owned multinational companies. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(8), 919-942.

Dunning, J. H., & Lundan, S. M. (2008). Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy,

Second Edition. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Finchelstein, Diego. (2012). Politicas públicas, disponibilidad de capital e internacionalización de empresas en América Latina: los casos de Argentina, Brasil y Chile. Apuntes: Revista da Ciencias

Sociales 39(70): 103-134.

Floriani, D. E., & Fleury, M. T. (2012). O efeito do grau de internacionalização nas competências internacionais e no desempenho financeiro da PME Brasileira. Revista de Administração

22

Gerschenkron, A. (1962). Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Graves, C., & Thomas, J. (2006). Internationalization of Australian family firms: A managerial capabilities perspective, Family Business Review 19(3): 207-224.

Hennart, J.-F. (1982). A Theory of Multinational Enterprise. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hennart, J.F. (2012). Emerging Market Multinationals and the theory of the multinational enterprise.

Global Strategy Journal 2(3): 168-187.

Hennart, J.F. & Park, Y. (1994). Location, governance, and strategic determinants of Japanese manufacturing investment in the United States. Strategic Management Journal 15(6): 419-436. Hennart, J.-F., Sheng, H. & Pimenta, G. (2015). The drivers of entry and expansion modes of US-based MNEs in Brazil. International Business Review 23(3): 466-475.

Inoue, C., Lazzarini, S., & Musacchio, A. (2013). Leviathan as a minority shareholder: firm-level implications of equity purchases by the state. Academy of Management Journal, 56(6): 1775-1801. JBS. (2015). About JBS. [http://www.jbs.com.br/en/about_jbs] Accessed September, 11, 2015. Jensen, M. & Meckling, W. (1976). Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure, Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4): 305-360.

Johanson, J. & Vahlne, J-E. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm. A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International

Business Studies. 8(1): 23-32.

Jones. G. (1996). The Evolution of International Business. London: Routledge.

Kontinen, T. & Ojala, A. (2010). The internationalization of family business: a review of extant research, Journal of Family Business Strategy, 1: 97-107.

Kroger, M. (2012). Neo-mercantilist capitalism and post-2008 cleavages in economic decision-making power in Brazil, Third World Quaterly, 33(5): 887-901.

Luce, M. (2008). La expansion del subimperialismo brasileño, Patria Grande 1(9) np

[https://patriagrande.org.bo/archivos/revistanumero14diciembre2008/la_expansion.pdf], accessed September 12, 2015.

Megginson, W. & Netter, J. (2001). From state to market: A study of empirical studies of privatization. Journal of Economic Literature 39(2): 321-389.

Miller, D. & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2005). Managing for the Long Run: Lessons in Competitive

Advantage from Great Family Businesses. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Musacchio, A., & Lazzarini, G. (2014). State-owned enterprises in Brazil: History and lessons, paper prepared for the Workshop on State-Owned Enterprises in the Development Process, Paris, 4 April. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

23

Musacchio, A, Lazzarini, S., & Aguilera, R. (2015). New varieties of state capitalism: strategic and performance Implications, Academy of Management Perspectives 29 (1): 115-121.

Nölke, A. (2010). A BRIC-variety of capitalism and social inequality: the case of Brazil, Revista de

Estudos e Pesquisas sobre as Americas 4(1): 1-11.

Oesterle, M-J., Richta, H. N., & Fish, J. H. (2013). The influence of ownership structure on internationalization. International Business Review, 22(1): 187-201.

Rocha, D. (2014). Estado, empresariado e variedades de capitalismo no Brasil: política de

internacionalização de empresas privadas no governo Lula. Revista de Sociologia e Política, 22(51): 77-96.

Schneider, B. (2008). Economic liberalization and corporate governance: the resilience of business groups in Latin America, Comparative Politics 40(4): 379-397.

Shamsuddoha, A. K., Ali, M. Y., & Ndubisi, N. O. (2009). Impact of government export assistance on internationalization of SMEs from developing nations. Journal of Enterprise Information

Management, 22(4): 408-422.

Silva, D. (2010). O governo brasileiro e a internacionalização de empresas, Texto informativo America Desenvolvimento, PUC Minas Conjuntura Internacional, ano 7, no. 11, 28/08/2010.

[http://www.pucminas.br/imagedb/conjuntura/CBO_ARQ_BOLET20100920142806.pdf?PHPSESSI

D=27b16fb39ac59dff1289e6d81f13f3a3], accessed September 02, 2015.

Sullivan, D. (1994). Measuring the degree of internationalization of a firm. Journal of International

Business Studies, 25(2): 325-342.

Trebat, T. (1983). Brazil’s state-owned enterprises: A case study of the state as entrepreneur. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wang, L, Hong, J, Kafouros, M, & Wright, M. (2012). Exploring the role of government involvement in outward FDI from emerging economies, Journal of International Business Studies 43(7): 655-676. Wells, L. (1971). The multinational business enterprise: what kind of international organization?

International Organization 25(3): 447-464.

World Bank. (2015). Doing Business Report. Washington DC: World Bank [www.doingbusiness.org/data]. Accessed September 13, 2015.

Zutshi, R. K., & Gibbons, P. T. (1998). The internationalization process of Singapore government-linked companies: a contextual view. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 15(2): 219-246.