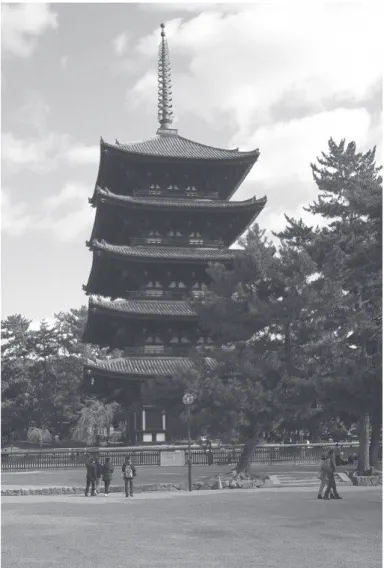

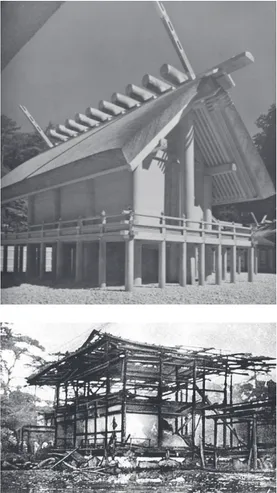

Time as formgiver in japanese architecture

Texto

Imagem

Documentos relacionados

Neste trabalho o objetivo central foi a ampliação e adequação do procedimento e programa computacional baseado no programa comercial MSC.PATRAN, para a geração automática de modelos

Ousasse apontar algumas hipóteses para a solução desse problema público a partir do exposto dos autores usados como base para fundamentação teórica, da análise dos dados

Isto é, o multilateralismo, em nível regional, só pode ser construído a partir de uma agenda dos países latino-americanos que leve em consideração os problemas (mas não as

didático e resolva as listas de exercícios (disponíveis no Classroom) referentes às obras de Carlos Drummond de Andrade, João Guimarães Rosa, Machado de Assis,

Despercebido: não visto, não notado, não observado, ignorado.. Não me passou despercebido

[r]

i) A condutividade da matriz vítrea diminui com o aumento do tempo de tratamento térmico (Fig.. 241 pequena quantidade de cristais existentes na amostra já provoca um efeito

Peça de mão de alta rotação pneumática com sistema Push Button (botão para remoção de broca), podendo apresentar passagem dupla de ar e acoplamento para engate rápido