UNIVERSITE CATHOLIQUE DE LOUVAIN LOUVAIN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT

and

NOVA SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS

The determinants of Foreign Direct Investments attraction in Portugal and Spain: a comparative analysis.

Supervisor at LSM: Dr. Marcel Gérard

Supervisor at NOVASBE: Dr. Luís Campos e Cunha

Research Master’s Thesis

Submitted by Guillaume Wenseleers (No.1842) With a view of getting the degrees

Master in Management Master in Business Engineering

2

Abstract

This paper analyzed the determinants of the net Foreign Direct Investments

inflows in Portugal and Spain; two countries chosen for their historical and

geographical closeness. The study included a large set of macroeconomic, institutional

and locational variables. The dataset is composed by yearly data points covering the

period 1984-2012. Using regressions in first differences, the paper concluded to the

significance of unit labor costs, openness to trade, political stability and socioeconomic

conditions for Portugal. As for Spain, market size and European Union GDP growth

played a significant role.

Keywords: Foreign Direct Investments; Attractiveness; Portugal; Spain.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my Thesis advisers, Professors

Luís Campos e Cunha and Marcel Gérard. I am extremely grateful to them for their

valuable guidance and support during this process. I also thank Professor Iliyan

Georgiev for the precious help that he provided me in the econometric part of this

research. Moreover, I am deeply indebted to my family, namely my parents, and friends

for the unceasing encouragement, support and advises during my entire education.

Without them, this accomplishment would not have been possible. Finally, I would like

to thank both NOVA and the LSM for the amazing opportunity they have offered me by

3

I. Introduction

With the more than five-fold increase in the inflows value between 1990 and

2012 (UNCTAD, 2013), Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) have been acknowledged as

one the drivers of the globalization process and a potential growth and development

vector (Zhan, 2006). Because of the capital, knowledge, technology, skills and

employments they bring, those investments became appealing for many governments.

Nevertheless, in order to create positive spillovers for the recipient country, various

authors have stressed out the necessity of a country strategy (Cortes et al., 2013), the

need to have reached a certain level of human capital (Borensztein et al., 1995) or to

have developed correct infrastructures (Gholami et al., 2005). Therefore, the link

between economic growth and FDI is not so obvious anymore. Despite that,

policymakers keep focusing on the attraction of FDI and set up creative measures to do

so.

As a consequence of this focus, numerous researches have been conducted.

Assunção et al. (2011) resumed in their paper three theories on the determinants of FDI

that emerged. The most fundamental is the OLI paradigm formalized by John Dunning

in 1976. According to him, the decision of a firm to undertake a FDI is the result of

three elements: the presence of an ownership advantage (O) of the firm on competitors,

the existence of a location advantage (L) in the foreign country and the advantage the

firm has to internalize its production (I) rather than using an external supplier(Dunning,

2001). The first force refers to the ownership of specialized assets by the investing

company, while the second one concerns the special conditions a firm will benefit from

in the foreign country (Assunção et al., 2011). Secondly, the authors gathered under the

4 of the location advantage: market size, market growth, openness to trade, natural

resources, etc. Finally, a third theory addressed the problem from the angle of

institutions, claiming that institutional quality may be the most influential factor on the

decision of multinationals to invest abroad.

The intensification of globalization has also modified the patterns of FDI. With

the reduction of trade barriers, distances and transportation costs, “vertical” FDI have

gained more importance compared to the “horizontal” ones. The latter, referred as

“market-seeking”, aims to allow a company to access an attractive host market. The

former, more “efficiency-seeking”, has the objective to benefit from lower production

costs, natural resources, strategic assets, etc. The distinction between the two has its

importance since the two types will not respond to the same determinants, as

demonstrated by Neary (2009).

This study aims to identify the main determinants of Foreign Direct Investments

flows in Portugal and Spain over the period 1984-2012. The analysis will investigate a

large set of determinants covering the three theories mentioned above in order to

compare the patterns of FDI in the two countries. With the aim to discover if the

distinction between market- and efficiency-seeking investments applies to these two

countries. To do so, the study will explore macroeconomic factors, institutional

variables and location-specific aspects.

The paper is structured as follows: section II will review the literature on the

subject, section III will explain the data and methodology, section IV will present the

main results and section V will conclude.

5

II. Literature review

Using quarterly and yearly data on the FDI inflows in Brazil and Mexico, de

Castro et al. (2013) showed that a large market is more attractive for foreign investors

since it represents a potential large demand and potential economies of scale. Numerous

authors acknowledged the same attraction effect (Bayraktar, 2013; Jadhav, 2012; Bellak

et al., 2008; Asiedu, 2006; Bevan et al. 2004; Bajo-Rubio et al, 1994). In its

multicountry empirical analysis, Billington (1999) showed that high GDP and growth

were significant to attract FDI. Walsh and Yu (2010), in their sectoral approach of

determinants, also concluded to the significance of growth.

A second determinant receiving attention in the literature is the openness of the

country to trade. Cortes et al (2013) pointed out, in their analysis of FDI determinants

for 113 countries, that the amount of FDI attracted is directly related to the trade

openness of a country. Khadaroo et al. (2010) and Bevan et al. (2004) came to the same

conclusion for Mauritius and Eastern Europe. Jadhav (2012) argued that the effect of

openness depended on the type of investment (as described in section I).

As well as Asiedu (2006) for Africa and Bajo-Rubio et al. (1994) for Spain,

Cortes et al. (2013) came to the conclusion that macroeconomic instability is a

discouraging factor of attraction.

A country’s budget deficit is often associated with its economic health and

stability. Its effect on the attraction of FDI remains nevertheless unclear. Bose et al.

(2011)’s study on the FDI flows in 15 European transition countries and India found

that fiscal deficits lead to reduced investments. On the contrary, Banga (2003) estimated

6 There is no consensus about the effect of labor costs in the literature, the results

depending on the type of measure used. Indeed, high labor costs could be a sign of high

productivity and consequently show a positive coefficient (Wei, 2000). That is the

reason why Bellak et al. (2008) highlighted the necessity to use real unit labor costs.

Unlike the divergent literature, they found a negative effect of high unit labor costs on

inflows of FDI. Bevan et al. (2004) and Bajo-Rubio et al. (1994) confirmed it.

Studies about the role of taxation in the location of FDI have raised mixed

evidence. In their study about the flows of FDI into emerging EU countries compared to

the flows in “older” EU countries, Göndör et al. (2012) indicated that low corporate tax

rates had not helped the emerging countries to attract more FDI flows. However,

American researchers (Desai et al., 2004) found evidence that direct such as indirect

taxes are costly and related with reduced Foreign Direct Investments.

As stressed by Ilyas et al. (2011), infrastructures have a significant impact on the

FDI in Pakistan, confirming their intuition that the infrastructures of a country are

determinant for the reduction of the business costs and for the efficiency. Khadaroo et

al. (2010), analyzing a sample of African countries, estimated a positive and significant

coefficient for the transportation and non-transportation infrastructures. Using the

number of phones per capita, Cortes et al. (2013) found the same effect on FDI.

Next to the physical capital, more skilled workers are likely to provide higher

quality outputs and integrate technology easily (Campos et al., 2002). In their study on

100 countries, Cortes et al. (2013) concluded that FDI were encouraged by a skilled

labor force. Investigating the inflows to 36 developing countries, Noorbakhsh et al.

7 Besides strict economic factors, the quality of institutions is also an important

determinant of FDI (Blonigen, 2005). Wei (2000) concluded on the important negative

impact of corruption, as it increases the cost of operating in a foreign country. He also

noticed that the inclusion of “political stability” gives a positive and significant relation

with FDI inflows. The same effect was found for governance indicators and business

climate (Bayraktar, 2013; Bénassy-Quéré et al., 2007).

III. Data and methodology

Based on the literature review, one was able to choose the variables to test. The

dataset consists in yearly data points collected for Portugal and Spain over the period

1984-2012. Please find in Appendix 1 all the necessary information about the variables.

The dependent variable will be the amount of net FDI inflows, valued at current

USD and provided by the UNCTAD database. Using the inflows seems to be

appropriate as they will be more responsive to incentives and shocks. Moreover, the net

term accounts for foreign divestments and better reflects the attractiveness of a country.

Based on the literature review, we expect a positive sign for market size,

economic growth, openness to trade, infrastructures, human capital, political stability

and socioeconomic conditions. A negative coefficient should appear for budget deficit,

inflation, corporate income tax rates and unit labor costs.

The methodology followed will be to run multiple regressions for each country

using the same explanatory variables, in order to allow a comparison of the final

conclusions. As the number of observations is limited, the general specification will use

8

The other explanatory variables will further be included, in substitution of the

non-significant ones of Equation (1).

The Breusch-Godfrey tests for autocorrelation performed on the regressions

using level variables showed a systematic autocorrelation of order 1 to 4. The

consequences of serial correlation are twofold: (i) it may make the coefficients

imprecise and (ii) the standard errors could be wrong. Therefore, it could lead to wrong

conclusions (Brooks, 2008).

The procedure to correct autocorrelation is described in Brooks (2008, p.150)

and consists merely in subtracting from the basic model a lagged version of this same

model with a coefficient ρ. This gives the following:

, with (2)

where the is the dependent variable at time t, the vector of coefficients, the

vector of independent variables, a coefficient to be estimated and the error term.

In practice, should be estimated (through the Cochrane-Orcutt procedure, for

example). However, in this study, we will fix . The model becomes then a model

in first differences:

(3)

Using first differences to deal with autocorrelation is totally acceptable,

9 series, even though they have a low power in such a small sample, seem to support this

transformation from level to first differences. Indeed, according to the results showed in

appendix 2, all the series exhibit the presence of one unit root. This raises the need to

differentiate the variables to achieve stationarity. Furthermore, working with first

differences presents the advantage to correct the smooth variation of the artificial

variables and the high multicollinearity.

To conclude this section, the starting point of the analysis will be the basic

model that follows:

The regressions will be estimated with OLS1. It must be noted that this study

will be less demanding as for the level of significance of the independent variables.

Indeed, the significance tests performed have low power in small samples, with the

consequence that some variables might appear insignificant. That is why this study will

allow a 15% significance level.

IV. Empirical results

The regressions were calculated with the Stata 13 program and the classical

linear model assumptions were tested. Jarque-Bera (adjusted for sample size),

Breusch-Pagan, VIF and Breusch-Godfrey tests were performed to verify the normality of

residuals and to detect heteroscedasticity, multicollinearity and autocorrelation. The

results show that the model does not violate the three first assumptions.

1

This methodology will not allow us to find the long-run equilibrium (Brooks, 2008). It is usually desirable to use a methodology that captures it. However, seeing the low number of observations, the probability to find an equilibrium is very low in this case.

10 Some explanation must be provided as for the autocorrelation. The

Breusch-Godfrey tests indicate that the basic model, for both Spain and Portugal, experiences

autocorrelation of at least order 1. It could be solved by including a further lag of the

variables but this process consumes a lot of degrees of freedom, what makes it

inconsistent in this case. As for the subsequent models, there is strong evidence that the

first differences corrected serial correlation at least until order 3, so that it can be

neglected. Nevertheless, in order to reduce the potential negative effects, the study will

use the Newey-West standard errors. This methodology produces standard errors

correcting for both heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation (Brooks, 2008).

1. Portugal

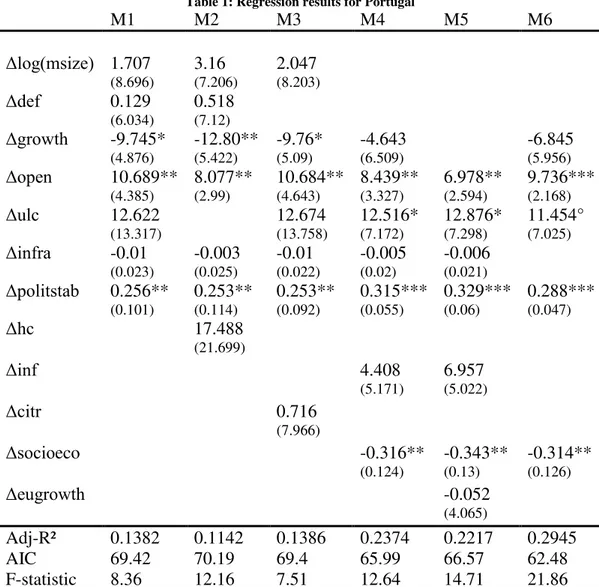

The regressions results found for Portugal are displayed in table 1. The first

empirical model used the basic specification indicated in equation (4). Only three

variables showed significance in explaining the FDI inflows, with a surprising negative

effect of growth. Note that the adjusted-R² did not have a satisfying explanatory power

and that the F-statistics indicated the model to be significant at 1%.

The second specification (M2) substituted the unit labor costs (ulc) by human

capital (hc), in order to test the potential effect of human capital on the attraction of

FDI. The test, however, was not conclusive and growth, openness to trade and political

stability remained the only significant variables. Seeing that the model quality

decreased, M1 was taken as basis for our further substitutions.

Attempting to verify the hypothesis that tax rates act as a deterrent for FDI, M3

11 Portugal, tax rates show a positive but non-significant effect and did not affect the rest

of the model.

Table 1: Regression results for Portugal

M1 M2 M3 M4 M5 M6

Δlog(msize) 1.707

(8.696) 3.16 (7.206) 2.047 (8.203) Δdef 0.129 (6.034) 0.518 (7.12) Δgrowth -9.745* (4.876) -12.80** (5.422) -9.76* (5.09) -4.643 (6.509) -6.845 (5.956) Δopen 10.689** (4.385) 8.077** (2.99) 10.684** (4.643) 8.439** (3.327) 6.978** (2.594) 9.736*** (2.168) Δulc 12.622 (13.317) 12.674 (13.758) 12.516* (7.172) 12.876* (7.298) 11.454° (7.025) Δinfra -0.01 (0.023) -0.003 (0.025) -0.01 (0.022) -0.005 (0.02) -0.006 (0.021) Δpolitstab 0.256** (0.101) 0.253** (0.114) 0.253** (0.092) 0.315*** (0.055) 0.329*** (0.06) 0.288*** (0.047) Δhc 17.488 (21.699) Δinf 4.408 (5.171) 6.957 (5.022) Δcitr 0.716 (7.966)

Δsocioeco -0.316**

(0.124) -0.343** (0.13) -0.314** (0.126) Δeugrowth -0.052 (4.065) Adj-R² AIC F-statistic 0.1382 69.42 8.36 0.1142 70.19 12.16 0.1386 69.4 7.51 0.2374 65.99 12.64 0.2217 66.57 14.71 0.2945 62.48 21.86

Standard errors in parentheses. Standard errors are robust to heteroscedasticity and potential correlation of errors. °Significant at 15%; *Significant at 10%; **Significant at 5%; ***Significant at 1%.

Seeing the non-significance of the market size, this variable was dropped and

replaced by the socioeconomic conditions. Moreover, the fourth regression took also

into account the potential impact of the macroeconomic instability (through inflation).

Socioeconomic conditions revealed a negative significant effect, meaning that a worse

situation would attract FDI inflows. The inclusion of these two variables increased the

12 A last substitution of the domestic growth by the European Union real GDP

growth did not bring anything to the general model (M5). As a consequence, a final

regression was run with the five significant variables found during the process. All

appeared significant, except the domestic GDP growth. The quality indicators of the

model remain a little bit disappointing while the overall model is significant at 1% level.

Overall, the results offer interesting interpretations. The market size exhibits the

expected positive sign but plays no role in the attraction of FDI in Portugal. It is an

indication that foreign investors are not looking to serve the Portuguese internal market

and would rather be interested in producing at lower costs for re-exportations to the

whole European market. The statistical insignificance of the domestic GDP growth

confirms this intuition.

As for the corporate income tax rates, if the foreign investments in Portugal are

“efficiency-seeking”, one could have expected a negative sign. Higher tax rates would

decrease the potential return on investment. The insignificance of the variable may be

explained by the variable choice. Statutory tax rates are theoretical and do not represent

what firms effectively pay, as stated in the literature.

Thirdly, openness to trade has an important and significant effect on the

attraction of FDI. It confirms previous studies on Portugal (Leitão et al., 2010) and

meets our expectations. The progressive liberalization of trade and foreign transactions

since the end of the dictatorship and the accession to the EEC benefitted to Portugal. A

further explanation of those results is given by Amador et al. (2007). According to the

authors, the improvement of the communication infrastructures after the mid-eighties

13 In our model, unit labor costs are significant and have a positive sign. It goes

against part of the literature but is not irrational. Several studies found the same sign

(Bénassy-Quéré et al., 2005; Boudier-Bensebaa, 2005). Unit labor costs may exhibit a

positive sign if the variable captures also skills and quality of labor. This holds for

Portugal. According to the OECD statistics, the labor productivity per unit of labor

input has almost doubled in 30 years while the real output per employee increased by

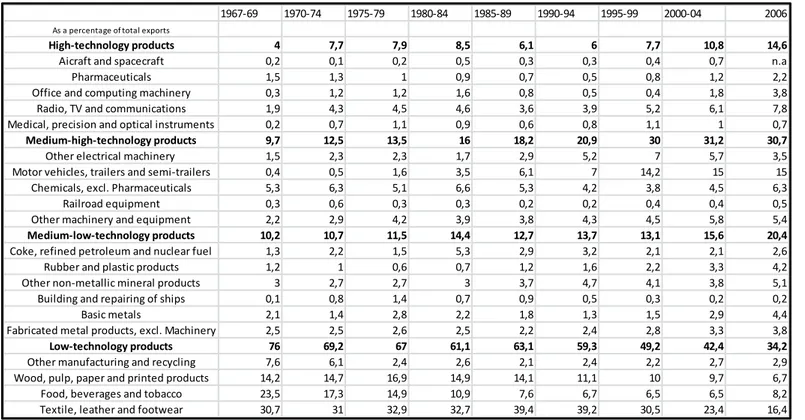

75% (see Appendix 3). Moreover, Amador et al. (2007) showed that, over the period

1967-2006, the share of medium-high and high technological exports increased

compared to the low technological ones. Therefore, one observes an increase in quantity

and quality of the Portuguese labor that supports this hypothesis. Unit labor costs in real

terms were also computed and tested in the models. As they brought no changes in the

results and since the nominal term is computed by an international organization, we

included only the results with the nominal unit labor costs.

The regressions confirmed the expected sign for political stability. It means that

foreign investors reacted positively to a more stable political and institutional

framework. This stability was strengthened by the transpartisan agreement to attract

FDI (Corado Simões et al., 2011), reducing the uncertainty for foreign investors.

The most unintuitive result is found for the socioeconomic conditions. The

negative effect indicates that a worsening of the socioeconomic conditions lead to

higher inward FDI. Although one should have expected the opposite sign, three

explanations exist. Firstly, several empirical studies concluded that a larger number of

unemployed job-seekers may attract foreign investors (Boudier-Bensebaa, 2005).

Secondly, a bad economic situation may attract investors looking for good opportunities

14 conditions may see foreign investors as a solution and set up incentives to attract them

(Head et al., 1999). As stated above, Portuguese authorities are indeed very active in

attracting FDI; they created the AICEP as sign of this commitment. Incentives are

another tool intensively used by the government. To give only one example, Oman

(2000) calculated that each job at the VW-Ford automobile plant of Setubal had been

subsidized with an amount of 265 000 USD.

The level of infrastructures development was insignificant for FDI inflows. One

may think that Portugal has reached a sufficient level of development so that the value

of additional infrastructures is very low. The same will be worth for Spain.

To summarize, the results corroborate the intuition that the FDI in Portugal were

mainly efficiency-seeking. Foreign investors were looking for stable institutions, a

proactive government behavior, ease of re-exporting goods and a better quality of labor

at a reasonable price. A hypothesis already expressed in Corado Simões et al. (2011).

2. Spain.

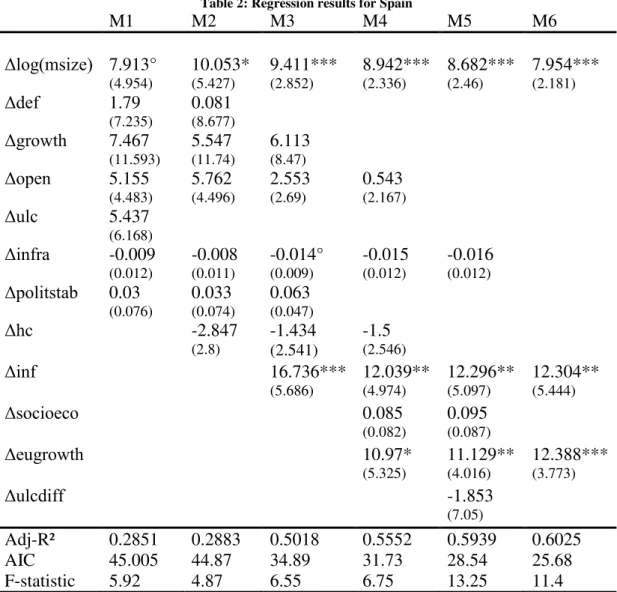

Using the same method as for Portugal, equation (4) was the first model tested.

Table 2 summarizes the results obtained for the successive regressions performed. The

adjusted-R² is low and the F-statistic concludes to a joint significance of the variables.

Nevertheless, the market size was the only variable to be statistically significant.

The second model (M2) substituted the ulc by hc, in order to test the potential

effect of human capital on the attraction of FDI. Human capital presented a negative but

not significant effect. Under this specification, the significance of the market size

improved such as the adjusted R² and the AIC value. It will be the basis for the

15

Table 2: Regression results for Spain

M1 M2 M3 M4 M5 M6

Δlog(msize) 7.913°

(4.954) 10.053* (5.427) 9.411*** (2.852) 8.942*** (2.336) 8.682*** (2.46) 7.954*** (2.181) Δdef 1.79 (7.235) 0.081 (8.677) Δgrowth 7.467 (11.593) 5.547 (11.74) 6.113 (8.47) Δopen 5.155 (4.483) 5.762 (4.496) 2.553 (2.69) 0.543 (2.167) Δulc 5.437 (6.168) Δinfra -0.009 (0.012) -0.008 (0.011) -0.014° (0.009) -0.015 (0.012) -0.016 (0.012) Δpolitstab 0.03 (0.076) 0.033 (0.074) 0.063 (0.047) Δhc -2.847 (2.8) -1.434 (2.541) -1.5 (2.546) Δinf 16.736*** (5.686) 12.039** (4.974) 12.296** (5.097) 12.304** (5.444) Δsocioeco 0.085 (0.082) 0.095 (0.087) Δeugrowth 10.97* (5.325) 11.129** (4.016) 12.388*** (3.773) Δulcdiff -1.853 (7.05) Adj-R² AIC F-statistic 0.2851 45.005 5.92 0.2883 44.87 4.87 0.5018 34.89 6.55 0.5552 31.73 6.75 0.5939 28.54 13.25 0.6025 25.68 11.4

Standard errors in parentheses. Standard errors are robust to heteroscedasticity and potential correlation of errors. °Significant at 15%; *Significant at 10%; **Significant at 5%; ***Significant at 1%.

As a third step, the deficit variable was replaced by inflation. On that way, the

regression controlled for macroeconomic instability. While the market size and the

inflation were highly positive and significant, the domestic growth and openness to

trade remained not relevant and with a positive sign. The infrastructures development

kept its negative effect and became significant at a 15% level.

In M4, political stability was removed for the socioeconomic conditions and the

domestic growth was replaced by the EU growth. The latter would help to determine if,

16 the domestic situation. The results were conclusive and the variable of EU growth

exhibited a positive significant effect, together with market size and inflation. However,

socioeconomic conditions were not relevant, such as openness and infrastructures.

The fifth model tested the possible effect of the difference in unit labor costs

between Spain and the average of the 18 countries of the Euro area. Human capital and

openness to trade were not included in the regression because of their insignificance.

The unit labor costs difference played no significant role in the attraction of FDI.

Finally, a last regression was run with the significant variables identified; the

market size, the EU growth and the inflation. The three have a positive effect on the

dependent variable and the model has a good explanatory power.

Overall, the Spanish determinants of FDI inflows show a clear difference with

Portugal. The first is the significance of the domestic market size. It appears that the

domestic GDP has a positive attraction effect on FDI. This is in agreement with most of

the studies (Bajo-Rubio et al., 1994; Rodriguez, 2008) and is the result one had

expected. Clifton et al. (2011) give different elements to corroborate this hypothesis: the

privatization of network companies and the liberalization of industries serving the local

market (electricity, gas, transports and telecoms). Furthermore, Chislett (2007)

described how FDI flew in after the accession to the EEC, attracted by the market

potential and large economies of scale. More recently, FDI have been more prominent

in the service sector (in banking and real estate services), focused on the local market.

The second significant variable is the European Union GDP growth rate, which

has a positive impact on the FDI inflows in Spain. This result seems to indicate that the

17 of its member states, namely Spain. Several studies, as reported in Blomström et al.

(1997), concluded that dynamic effects of regional integration led to higher

intraregional FDI. The result confirms this mechanism for Spain, a fortiori when the

regional bloc is growing. Moreover, as most of the investments flows come from the

EU members, it is normal that economic dynamism in these countries drove foreign

financial means into Spain. This outcome shows as well that the lights shed on Spain –

presented as the good performer in Europe – in a period where the EU was growing and

gaining importance participated to the attractiveness of the country of Cervantes.

The two countries distinguish themselves also concerning the socioeconomic

conditions. In Spain, they have a positive sign, even if they are not significant. Higher

consumer confidence and less poverty are not disadvantageous for market-seekers. As

opposed to Portugal also, the openness to trade was not significant. The openness of a

country is not fundamental when FDI are interested in the domestic market.

The human capital has a negative but insignificant impact. It is unexpected since

the index level is comparable to France, Italy and Germany. However, recent research

(Dutta et al., forthcoming) concluded to the non-linearity of the human capital impact.

According to them, after a certain threshold, the association between skills and FDI

becomes negative. The same effect might be at work in Spain.

It must be noted that corporate income tax rates were not taken into account to

avoid spurious results. The rate changed only two times on the considered period and it

fortuitously corresponded with several foreign acquisitions (ENEL acquiring Endesa

and Industrial Tobacco acquiring Altadis SA). Hence, the increase in FDI had no

18 Very surprisingly, the analysis concluded to a positive and significant influence

of inflation. As it contradicts all the preceding studies, this fact is difficult to explain.

Assuming that there might be another association “hidden” behind it, inflation has been

controlled with related variables and variables linked to economic stability. Hence,

domestic growth, nominal effective exchange rate, public debt and total tax revenues

were added to the model M3 and M6.These controls gave no satisfaction; none of them

was significant nor mitigated the effect of inflation. It indicates that macroeconomic

instability is not a concern for investors in the European institutional framework

anymore. As a consequence, this result without economic meaning may be neglected.

To summarize, it comes out from this study that the FDI flowing into Spain were

mainly conducted for market-seeking motivations. The size of the internal market

attracted investors willing to serve a huge demand and to make large economies of

scale. The positive coefficient of EU economic growth supports this hypothesis.

3. Limitations of the study

Given the aim of the study, that is to compare the specific determinants of FDI

attraction in Spain and Portugal, the sample of observations was quite limited in size.

Too few observations may decrease the robustness of the results and forced us to use

our unorthodox methodology of model selection. Having more data points would have

strengthened the analysis and its conclusions. A second weakness of this study is the use

of the statutory tax rate. The effective tax rate would have better represented the fiscal

burden of corporations. However, no data was found for the period considered. As third,

despite additional controls, no explanation was found for the positive and significant

effect of inflation on the inflows of FDI in Spain. Hence, it was neglected. Finally,

19 regulations and the countries’ perception are absent of the study. It would have been

interesting to find a way to include them.

V. Conclusion

Building upon the three main theories of Foreign Direct Investments attraction,

this study gathers together macroeconomic, institutional and locational determinants of

FDI in order to identify and compare the patterns of FDI in Portugal and Spain. This

paper explains the net FDI inflows in each country with the above mentioned variables.

After the literature review, regressions were conducted using yearly aggregated

data over the period 1984-2012. The reported F-statistics allow to conclude to the

significance of the overall models. The adjusted-R² indicate a good explanatory power

for Spain and a low power for Portugal.

The results reveal, at the Iberian level, the dichotomy theorized by previous

researches between market-seeking and efficiency-seeking investments. The model

shows evidence that higher unit labor costs, more openness to international trade, better

political stability and the effects of worse socioeconomic conditions acted as attracting

factors for FDI in Portugal. On the contrary, a larger market size and economic

dynamism at the regional level motivated foreign investments in Spain. At the exception

of the inflation, these results confirm the hypothesis of Neary (2009). Furthermore,

infrastructures, human capital and budget deficit showed statistical insignificance.

To conclude, even if globalization and regional integration are irreversible, a

country cannot simply replicate the policies of neighbors to attract FDI. Local

20

VI. References

Addison, Tony, Basudeb Guha-Khasnobis, and George Mayrotas. 2006.

“Introduction and Overview.” World Economy, 29(1): 1-8.

Amador, João, Sonia Cabral, and José R. Maria. 2007. “International trade patterns

in the last four decades: How does Portugal compare with other cohesion countries?”

Banco de Portugal Working Paper 14/2007.

Asiedu, Elizabeth. 2006. “Foreign direct investment in Africa: The role of natural

resources, market size, government policy, institutions and political instability.” The World Economy, 29(1): 63-77.

Assunção, Susana, Rosa Forte, and Aurora A.C Teixeira. 2011. “Location

Determinants of FDI: A Literature Review.” Faculdade de Economia de Porto Working Paper 433.

Bajo-Rubio, Oscar, and Simon Sosvilla-Rivero. 1994. “An econometric analysis of foreign direct investment in Spain, 1964-89.” Southern Economic Journal, 61(4): 104-120.

Banga, Rashmi. 2003. “Impact of government policies and investment agreements on

FDI inflows.” Indian Council for Research on Economic Relations Working Paper 116.

Bayraktar, Nihal. 2013. “Foreign Direct investment and Investment Climate.”

Procedia Economics and Finance, 5: 83 – 92.

Bellak, Christian, and Markus Leibrecht. 2009. “Do low corporate income tax rates

attract FDI?–Evidence from Central-and East European countries.” Applied Economics, 41(21): 2691-2703.

Bellak, Christian, Markus Leibrecht, and Aleksandra Riedl. 2008. “Labor costs and FDI flows into Central and Eastern European Countries: A survey of the literature and

empirical evidence.” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 19(1): 17-37.

Bénassy‐Quéré, Agnès, Maylis Coupet, and Thierry Mayer. 2007. “Institutional

determinants of foreign direct investment.” The World Economy, 30(5): 764-782.

Bénassy-Quéré, Agnès, Lionel Fontagné and Amina Lahrèche-Révil. 2005. “How

does FDI react to corporate taxation?”International Tax and Public Finance, 12(5): 583-603.

Bevan, Alan A. and Saul Estrin.2004. “The determinants of foreign direct investment

21

Billington, Nicholas. 1999. “The location of foreign direct investment: an empirical

analysis.” Applied economics, 31(1): 65-76.

Blomström, Magnus and Ari Kokko. 1997. “Regional Integration and Foreign Direct

Investment.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 6019.

Blonigen, Bruce A. and Jeremy Piger. 2011. “Determinants of foreign direct

investment.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 16704.

Blonigen, Bruce A. 2005. “A Review of The Empirical Literature On FDI

Determinants.” Atlantic Economic Journal, 33(4): 383-403.

Borensztein, Eduardo, José De Gregorio, and Jong-Wha Lee. 1995. “How Does Foreign Direct Investment Affect Economic Growth?” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 5057.

Bose, Suchismita, and Sudipta Jha. 2011. “Financial Crises, Fiscal Deficits and

Foreign Direct Investments. Lessons for India from Emerging Europe.” http://www.icra.in/Files/MoneyFinance/financialcrisis.pdf

Boudier‐Bensebaa, Fabienne. 2005. “Agglomeration economies and location choice:

Foreign direct investment in Hungary.”Economics of Transition, 13(4): 605-628.

Brooks, Chris. 2008. Introductory Econometrics for Finance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Campos, Nauro F., and Yuko Kinoshita. 2002. “The location determinants of foreign direct investment in transition economies.”

http://project.iss.u-tokyo.ac.jp/nakagawa/members/papers/3(9)kinoshita.final.pdf

Chislett, William. 2007. “Foreign Direct Investments in Spain.” Real Instituto Elcano

Working Paper 47/2007.

Clifton, Judith, Daniel Díaz-Fuentes, and Eduardo Ruiz. 2011. “Inward FDI in

Spain and its policy context.” Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International

Investment.

Corado Simões, V., and Cartaxo, M. 2011. “Inward FDI in Portugal and its policy

context.” Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International Investment.

Cortes, Gustavo S., and Claudio A.C Paiva. 2013. “Globalization and the Evolution

of Foreign Direct Investment Attractors: Why Mercosul lags the World.”

http://www.academia.edu/2613804/Globalization_and_the_Evolution_of_Foreign_Dire

22

de Castro, Priscila G., Elaine A. Fernandes, and Antônio C. Campos. 2013. “The

determinants of foreign direct investment in Brazil and Mexico: an empirical analysis.” Procedia Economics and Finance, 5: 231 – 240

Desai, Mihir A., Fritz C. Foley, and James R. Hines Jr. 2004. “Foreign direct

investment in a world of multiple taxes.” Journal of Public Economics, 88(12): 2727-2744.

Dunning, John H. 2001. "The eclectic (OLI) paradigm of international production: past, present and future." International journal of the economics of business, 8(2): 173-190.

Dutta, Nabamita, and Kwasi Osei-Yeboah. Forthcoming.“Foreign Direct Investment and Human Capital: The Role of Political and Civil Rights.” Journal of International Development. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=12630388

Fabry, Nathalie., and Sylvain Zeghni. 2010. “Inward FDI in seven transitional

countries of South-Eastern Europe: a quest of institution-based attractiveness.” Eastern Journal of European Studies, 1(2): 77-91.

Gholami, Roghieh, Sang-Yong T. Lee, and Almas Heshmati. 2005. “The causal

relationship between ICT and FDI.” United Nations University – WIDER Research Paper 2005/26.

Göndör, Mihaela, and Paula Nistor. 2012. “Fiscal Policy and Foreign Direct

Investment: Evidence from some Emerging EU Economies.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 58: 1256-1266.

Groh, Alexander P., and Matthias Wich.2009. “A composite measure to determine a

host country's attractiveness for foreign direct investment.” IESE Business School

Working Paper 833.

Head, Keith C., John C. Ries, and Deborah L. Swenson. 1999. “Attracting foreign

manufacturing: Investment promotion and agglomeration.”Regional Science and Urban Economics, 29(2): 197-218.

Historical Public Debt Database. 2014. IMF.

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.cfm?sk=24332.0 (accessed May 08,

2014)

International Country Risk Guide. 2014. Political Risk Services Group.

https://www.prsgroup.com/ (accessed Januray 20, 2014).

Ilyas, Muhammad, Abdul Ch. Rehman, Hassan M. Alam, and Muhammad Akram. 2011. “The impact of infrastructure on foreign direct investment: The case of

23

Jadhav, Pravin. 2012. “Determinants of foreign direct investment in BRICS

economies: Analysis of economic, institutional and political factor.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 37: 5-14.

Júlio, Paulo, Ricardo Pinheiro–Alves, and José Tavares. 2013. “Foreign direct investment and institutional reform: evidence and an application to Portugal.” Portuguese Economic Journal, 12: 215-250

Khadaroo, Jamel, and Boopen Seetanah.2010. “Transport infrastructure and foreign

direct investment.” Journal of International Development, 22(1): 103-123.

Leitão, Nuno C., and Horácio C. Faustino. 2010. “Determinants of Foreign Direct

Investment in Portugal.”Journal of Applied Business & Economics, 11(3): 19-26.

Neary, Peter J. 2009. “Foreign direct investment: The OLI framework.” In The Princeton Encyclopedia of the World Economy, Volume I, ed. Lewis Davis, Amy Glass, Ramkishen Rajan and Kenneth Reiner, 472-477. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Noorbakhsh, Farhad, Alberto Paloni, and Ali Yousse. 2001. “Human Capital and

FDI Inflows to Developing Countries: New Empirical Evidence.” World Development, 29(9): 1593-1610.

Oman, Charles. 2000. Policy Competition for Foreign Direct Investments. Paris: OECD Development Centre.

Penn World Tables. 2014. Center for International Comparisons.

https://pwt.sas.upenn.edu/ (accessed January 15, 2014).

Rodriguez, Xosé A., and Julio Pallas. 2008. “Determinants of foreign direct investment in Spain.” Applied Economics, 40: 2443-2450.

UNCTAD. 2013. World Investment Report 2013 – Global Value Chains: Investment and Trade for Development. New York: United Nations.

Walsh, James P., and Jiangyan Yu.2010. “Determinants of foreign direct investment:

A sectoral and institutional approach.” International Monetary Fund Working Paper 10/187.

Wei, Shang-Jin. 2000. "How taxing is corruption on international investors?" Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(1): 1-11.

Zhan, Jimmy. 2006. “FDI statistics. A critical review and policy implications.”

24

Appendix 1: Description of the variables

Variable Proxy Source

FDI Annual net FDI inflows, in billions of (current) USD UNCTAD Stat Market size (msize) Real GDP (2005 USD), in billions World Bank (WDI) Public deficit (def) Budget deficit (% of GDP) IMF WEO database

GDP growth (growth) Real GDP growth, in % World Bank (WDI)

Openness to trade (open) Trade-to-GDP ratio, in % (current prices) UNCTAD Stat Inflation (inf) Consumer Price Index, annual growth in % IMF WEO database Unit labor costs (ulc) Annual nominal unit labor costs, in % OECD Stat

Corporate income tax rate (citr) Combined corporate income tax rate, in % OECD Stat

Infrastructures (infra) Fixed and mobile phone subscriptions per 100 persons,

# World Bank (WDI)

Human capital (hc) Index of human capital, # Penn World Tables Political stability (politstab) Index of political stability, /12 ICRG -CountryData Socioeconomic conditions

(socioeco) Index of socioeconomic conditions, /12 ICRG -CountryData European Union GDP growth

(eugrowth) Real European Union GDP growth, in % World Bank (WDI) Unit labor costs difference

(ulcdiff)

Difference in unit labor costs between the 18 countries

of the Euro area and Spain, in % OECD Stat

Nominal effective exchange

rate (neer) Nominal Effective Exchange Rate, Index (2010=100)

Bank of International Settlements Public debt (debt) Public debt to GDP ratio, in % HPDD Total tax revenues (taxrev) Total tax revenues to GDP ratio, in % OECD Stat

Real unit labor costs (rulc) Nominal unit labor costs deflated with the Consumer

Price Index, Index (2010=100) OECD Stat

Appendix 2: Results of the Dickey-Fuller tests

Portugal Spain

Variables Lag

selection

Augmented Dickey-Fuller (time trend (t))

Critical

value Variables

Lag selection

Augmented Dickey-Fuller (time trend (t))

Critical value

log(FDI) 2 -3,0 -3,238 log(FDI) 2 -2,534 -3,238

log(msize) 2 -0,634 -3,238 log(msize) 2 -1,04 -3,238

def 2 -1,812 -3,238 def 2 -0,929 -3,238

growth 2 -3,066 -3,238 growth 2 -1,917 -3,238

open 2 -2,981 -3,238 open 2 -1,802 -3,238

inf 2 -1,858 -3,238 inf 2 -3,063 -3,238

ulc 2 0,6 -3,238 ulc 2 -1,094 -3,238

citr 2 -1,496 -3,238 citr 2 -0,956 -3,238

infra 2 -1,86 -3,238 infra 2 -1,803 -3,238

hc* 2 -3,798 -3,238 hc 2 -1,455 -3,238

politstab 2 -2,297 -3,238 politstab 2 -2,253 -3,238

socioeco 2 -1,761 -3,238 socioeco 2 -2,345 -3,238

eugrowth 2 -2,85 -3,238 eugrowth 2 -2,85 -3,238

25

Appendix 3: Data on the Portuguese labor productivity and real output

Source: OECD Stat

Source: OECD Stat

57.58237 103.0356 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 In d e x o f Lab o u r Pr o d u ctiv ity Years

Labour Productivity per unit of Labour Input

(2010=100) Portugal 16253.2 29082.82 0 5000 10000 15000 20000 25000 30000 35000 R e al Ou tp u t (e u ro s) YearsReal Output per Person Employed

(Euros, constant prices)UNIVERSITE CATHOLIQUE DE LOUVAIN LOUVAIN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT

and

NOVA SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS

The determinants of Foreign Direct Investments attraction in Portugal and Spain: a comparative analysis

-

Appendix to the Thesis

Supervisor at LSM: Dr. Marcel Gérard

Supervisor at NOVASBE: Dr. Luís Campos e Cunha

Research Master’s Thesis

Submitted by Guillaume Wenseleers (No.1842) With a view of getting the degrees

Master in Management Master in Business Engineering

2

Table of Contents

I. Literature review: complete version ... 3

1. Market size and potential ... 3

2. Openness to trade ... 3

3. Macroeconomic stability ... 4

4. Budget deficit ... 4

5. Labor costs ... 4

6. Taxation level ... 5

7. Level of infrastructures ... 5

8. Level of human capital ... 6

9. Institutional factors ... 6

II. Explanation of the variables ... 7

III. Historical description of the FDI in Portugal ... 9

IV. Origin of the FDI in Portugal ... 10

V. Historical description of the FDI in Spain ... 13

VI. Origin of the FDI in Spain ... 14

VII. Specialization of the Portuguese exports ... 17

3

I. Literature review: complete version 1. Market size and potential

At a first sight, one might consider the economic situation of a host country very

likely to affect the incoming flows of FDI. Using quarterly and yearly data on the FDI

inflows in Brazil and Mexico, de Castro et al. (2013) found a stronger positive

relationship between the host country GDP and the investments flows for Brazil than for

Mexico. This confirms that a large market is more attractive for foreigners since it

represents a potential large demand and potential economies of scale. Numerous authors

acknowledged the same attraction effect (Bayraktar, 2013; Jadhav, 2012; Bellak et al.,

2008; Asiedu, 2006; Bevan et al. 2004; Bajo-Rubio et al, 1994). In its multicountry and

multiregion empirical analysis, Billington (1999) showed that high GDP and growth

were significant to attract FDI. Walsh and Yu (2010), in their sectoral approach of

determinants, also concluded to the significance of growth. However, Billington also

cited authors stating an insignificant effect of growth (Scaperlanda and Mauer, 1969).

The same insignificance of growth was found by Bayraktar (2013) using correlations.

2. Openness to trade

A second determinant receiving attention in the literature is the openness of the

country to trade. Cortes et al (2013) pointed out, in their analysis of FDI determinants

for 113 countries, that the amount of FDI attracted is directly related to the trade

openness of a country. They even showed that this variable gained in importance in the

last years as a consequence of the globalization. Jadhav (2012) argued that the effect of

openness depended on the type of investments (as described in section I), while de

Castro et al. (2013) concluded that the opening to trade helped both Mexico and Brazil

4 countries. Khadaroo et al. (2010), investigating the attractiveness of Mauritius,

concluded that trade openness was one of the main motivators of investments. This

impression was confirmed by Bevan et al. (2004) in their study of FDI flows to

European transition economies.

3. Macroeconomic stability

Following the work of Altomonte, Cortes et al. (2013) came to the conclusion

that macroeconomic instability is a discouraging factor of attraction. Using the inflation

rate as a proxy for macroeconomic instability in 22 Sub-Saharan countries, Asiedu

(2006) found a deterring effect of the inflation on incoming investments. Bajo-Rubio et

al. (1994) discovered the same negative and significant relation as for Spain.

4. Budget deficit

A country’s budget deficit is often associated with its economic health and

stability. Indeed, one could expect from a country with continuous deficits to increase

the tax burden or to take difficult adjustment measures likely to affect the

macroeconomic environment or the profitability of the investors. Its effect on the

attraction of FDI remains nevertheless unclear. Bose et al. (2011)’s study on the FDI

flows in 15 European transition countries and India found that fiscal deficits lead to

reduced investments. On the contrary, Banga (2003) estimated the effect of FDI policies

on the incoming flows to 15 developing countries. He concluded that the budget deficit

was not significant in the attraction of aggregate FDI.

5. Labor costs

There is no consensus about the effect of labor costs in the literature, the results

depending on the type of measure used. Intuitively, one would expect a negative effect

5 consequently show a positive coefficient. This assumption was raised by Wei (2000).

That is the reason why Bellak et al. (2008) highlighted the necessity to use real unit

labor costs, defined as the total nominal labor costs over nominal output per

employment. Unlike the divergent literature, they found a negative effect of high unit

labor costs on inflows of FDI. Bevan et al. (2004) and Bajo-Rubio et al. (1994)

confirmed it.

6. Taxation level

Studies about the role of taxation in the location of FDI have raised mixed

evidence. In their study about the flows of FDI into emerging EU countries compared to

the flows in “older” EU countries, Göndör et al. (2012) indicated that low corporate tax

rates had not helped the emerging countries to attract more FDI flows. And multiple

authors pointed out that the firm leaders do not consider a favorable tax policy as the

most important factor when investing abroad (Simmons, 2003). However, American

researchers (Desai et al., 2004) found evidence that direct such as indirect taxes are

costly and related with reduced Foreign Direct Investments. Wei (2000) reported a

negative and significant effect of tax rates on the attraction of FDI. Bellak et al. (2009)

concluded that taxes are almost as relevant as labor costs but less than the market size.

7. Level of infrastructures

As stressed by Ilyas et al. (2011), infrastructures have a significant impact on the

FDI in Pakistan, confirming their intuition that the infrastructures of a country are

determinant for the reduction of the business costs and for the efficiency. Khadaroo et

al. (2010), analyzing a sample of African countries, estimated a positive and significant

coefficient for the transportation and non-transportation infrastructures. Using the

6 Although most of the studies confirm the crucial contribution of infrastructures

(Billington, 1999), Quazi (2005) did not find anything significant (according to

Khadaroo et al., 2010).

8. Level of human capital

Next to the physical capital, the level of human capital is also a matter of

concern for foreign investors. Indeed, more skilled workers are likely to provide higher

quality outputs and integrate technology easily (Campos et al., 2002). In their study on a

sample of 100 countries, Cortes et al. (2013) concluded that FDI were encouraged by a

skilled labor force. Khadaroo et al. (2010) confirmed previous results of Asiedu (2006),

stating the labor force quality as enhancing the attractiveness of a country. Investigating

the FDI flows to 36 developing countries from 1980 to 1994, Noorbakhsh et al. (2001)

found that human capital is an important determinant of the locational advantage.

9. Institutional factors

Besides strict economic factors, the quality of institutions is also an important

determinant of FDI (Blonigen, 2005). Jadhav (2012), taking corruption and enforcement

of contracts as proxies, concluded that inefficient institutions act as a deterrent to FDI in

the BRICS. Asiedu (2006) drew the same conclusion about African countries. Wei

(2000) concluded on the important negative impact of corruption, as it increases the cost

of operating in a foreign country. He also noticed that the inclusion of “political

stability” gives a positive and significant relation with FDI inflows. In his study on the

ease of doing business, Bayraktar (2013) found strong evidence that a favorable

business climate was very attractive for foreign investors. Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2007)

examined the influence of recipient country institutions by including governance

7

II. Explanation of the variables

The dataset consists in yearly data points collected for Portugal and Spain over

the period 1984-2012.

The dependent variable will be the amount of net FDI inflows, valued at current

USD and provided by the UNCTAD database. Although several studies focus on FDI

stocks, using the inflows seems to be appropriate as they will be more responsive to

incentives and shocks. Moreover, the net term accounts for foreign divestments and

better reflects the attractiveness of a country.

The macroeconomic independent variables of the model are the country’s real

GDP (for the market size), the real GDP growth rate, the budget deficit over GDP, the

sum of exports and imports over GDP (as a proxy for openness to trade flows) and the

inflation rate (proxying macroeconomic instability). The data was collected from the

World Development Indicators, the IMF World Economic Outlook database and the

UNCTAD database. Market size, GDP growth and openness to trade should have a

positive effect. Budget deficit and inflation are expected to have a negative coefficient.

The locational independent variables are the unit labor costs, the number of

mobile and fixed phone subscriptions per 100 people (a proxy for infrastructures), the

combined statutory corporate income tax rate and the level of human capital. The

combined statutory corporate income tax rate is a measure accounting for the taxes to

pay to the local and national governments. Hence, it better reflects the total fiscal

burden borne by firms. The level of human capital is an index computed in the Penn

8 population1. The data for the tax rates and unit labor costs come from the OECD

databases and the infrastructures data were found in the World Development Indicators

database. All of their coefficients should show a positive sign, except for the corporate

income tax rates and unit labor costs.

The institutional variables are the political stability and the socioeconomic

conditions of the country. The former reflects the government and legislative strengths.

The latter represents the forces present in a country that could generate social

dissatisfaction (poverty, unemployment and consumer confidence) (PRS Group, 2014).

The data are based on monthly assessments made for the International Country Risk

Guide database. The assessments allow the database provider to give a grade (out of 12)

to the country for each of the two variables considered. Because a high score represents

a low risk, the variables should affect the FDI positively.

1

9

III. Historical description of the FDI in Portugal

FDI have been a component of Portuguese economy since the 16th century –

when Portugal dominated the international trade – and under the era of the Pombal

Marquis (Barros Castro, 2000).

The dictatorship period and several dramatic policies deterred foreign investors

and cut Portugal from international capital flows until the 1960’s. The membership to

the European Free Trade Association in 1960 changed the economic evolution of

Portugal (Casqueira, 2010). From that period on until 1973, the country knew a huge

increase in FDI inflows, particularly in low-technological activities (textiles and wood

products) where Portugal had a comparative advantage (as shown in Amador et al.,

2007).

During the following decade, the Portuguese open economy suffered from the

two oil shocks, from national policies (nationalizations, new labor regulation, reduction

of economic efficiency) consecutive to the 1974 revolution and from the loss of

colonies that finally led the IMF to intervene in 1983 (Barros Castro, 2000).

Simultaneously, FDI inflows suffered from the situation.

The recovery came during the second half of the 1980’s. The perspective of the

accession to the EEC, the proactive behavior of the successive governments and lower

oil prices gave a push to the foreign investments (Barros Castro, 2000). They were

mainly looking for lowering production costs in a country that was converging to the

European average.

The decade of the 1990’s saw the growth of FDI flows to Portugal slowing down

10 (AutoEuropa being the most illustrative) but the European economy decelerated and

Eastern European and Asian countries started to compete (Corado Simões, 2011).

However, almost at the same time, the Portuguese industrial complex acknowledged a

structural shift from low-technology and labor-intensive products to higher value added

and technology-intensive products (Casqueira, 2010) that attracted another type of

investors and further diversified the economy.

In the first decade of 2000, the FDI trend observed at the end of the 1990’s

seemed to have persisted. Figures of the AICEP show that the low-tech manufacturing

industry is losing ground compared to the automotive and financial sectors, supporting

the “sophistication” change operated in the Portuguese economy.

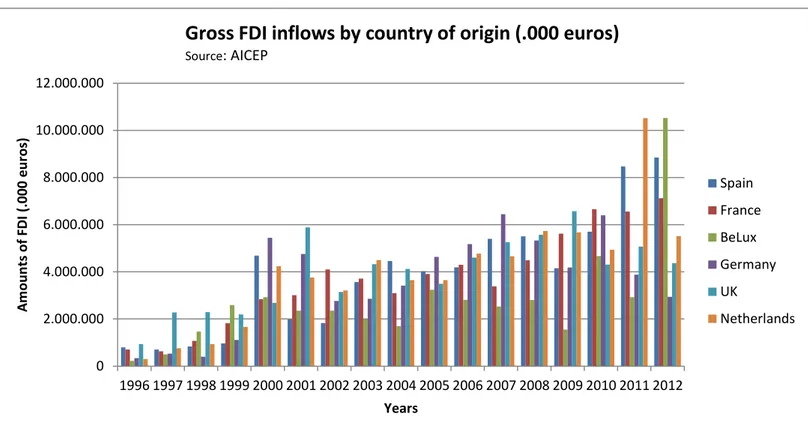

IV. Origin of the FDI in Portugal

When it comes to the geographical breakdown of the gross FDI inflows, one

notices that the large majority of the capital comes from 6 European countries. Over the

considered period, they have accounted for 65 to 87% of the gross flows. The Figures 1

and 2 display the necessary data.

The presence of UK among the main investors is not a surprise. Links between

the two countries are strong since the Middle Ages. Following several alliances against

Spain or France, the countries have a long tradition of bilateral trade that favored the

English investments in Portugal (The Anglo-Portuguese Society, 2007).

Figures 1 and 2 show that Spain represents the main gross investor. Except in

1999 and 2010, net FDI have always been positive, even during the recent crisis

11 core of Europe explains part of this relationship. The other reason, described by Barros

Castro (2000), is that Spain serves as an intermediate step for non-EU multinationals

willing to invest in Portugal. They then do it through their regular affiliate operating in

Spain or through a holding company, an ETVE (“Entidad de Tenencia de Valores

Extranjeros”).

It is almost the same mechanism applying for the Netherlands and the BeLux,

which also have special tax regimes for holding companies. These practices are behind

the volatility of their net FDI into Portugal.

At last, the decreasing role of Germany must be pointed out. Although it is a

historical investor in Portugal, Germany has been divesting during the last decade. It is

the consequence of the German firms turning their focus to Eastern Europe (the German

FDI stock more than tripled in countries like Hungary, Czech Republic and Poland

during the last decade) (Hirdina et al., 2010).

One may notice that the majority of FDI has its origins in the biggest European

economies. It exemplifies the intuition raised by Galego et al. (2004): firms operating in

large market have more possibilities to enjoy economies of scale and build up the

efficient structure/scale that will allow them to invest abroad. Firms operating in smaller

12

Figure 1: Gross FDI inflows by country of origin

Figure 2: Net FDI inflows by country of origin 0 2.000.000 4.000.000 6.000.000 8.000.000 10.000.000 12.000.000

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

A m o u n ts o f FD I (.000 e u ro s) Years

Gross FDI inflows by country of origin (.000 euros)

Source: AICEP

Spain France BeLux Germany UK Netherlands -3.000.000 -2.000.000 -1.000.000 0 1.000.000 2.000.000 3.000.000 4.000.000 5.000.000 6.000.000 7.000.000

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

A m ou n ts of FD I (.0 00 eu ros) Years

Net FDI inflows by country of origin (.000 euros)

13

V. Historical description of the FDI in Spain

The first significant FDI surge occurred in the 1850’s after the adoption of

accommodating regulation for foreign investors by Queen Isabel II. According to data

gathered by Castro et al. (2009), the main investing countries were France, the UK and

Belgium, mainly in the transportation sector. This industry as well as mining, wineries

and banking drove the majority of capital flows into Spain during the early 20th century

(Campa et al., 1994).

The above described movement slowed down in the late 1920’s. The Great

Depression strongly affected the international investments. On the top of that, the

country knew a civil war from 1936 until 1939 that brought an authoritarian regime to

power. The Franco regime built up economic barriers around the country with

trade-deterring measures, reinforced by a “post-WWII” embargo (Campa et al., 1994). Those

events reduced considerably the amounts of FDI to Spain.

The period of economic isolation came to an end in the 1950’s with Spain

joining the IMF and the OECD and the adoption of the 1959 Stabilization Plan

(Chislett, 2014). The Plan aimed at controlling inflation, stimulating growth and

“liberalizing foreign trade and encouraging foreign investment” (Meditz et al., 1988).

This policy played its role by attracting plenty of foreign investors interested in the

“virgin” significant domestic market.

Foreign investments grew sharply until 1973. Then, two oil shocks, the

uncertainty linked to the democratic process (Alguacil et al., 2001) and a world

economic crisis smoothed the upward trend. Nevertheless, the perspective of the

EU-membership and the resulting liberalization, privatizations and convergence to the EU

14 In the 1990’s, a trade reform, policy changes (in terms of exchange control and

foreign capital discrimination) and the devaluations of 1992 and 1993 (Chislett, 2014)

sustained the attractiveness of Spain despite the European economic deceleration. Most

of the investments were takeovers of Spanish firms in food, manufacturing and

chemicals (Campa et al., 1994).

The last decade saw the inflows continuously growing and the services gaining

more and more importance. According to Clifton et al. (2011), services accounted for

almost the double or the triple of the FDI in the two other sectors between 2005 and

2008. Moreover, services to local market (construction and retail industry) were

significant vectors of investment. Recently, Spain has defined six sectors particularly

attractive for FDI: the automotive sector, biotechnologies, food and agriculture, ICT and

audiovisual, aerospace and machine-tooling (Chislett, 2014).

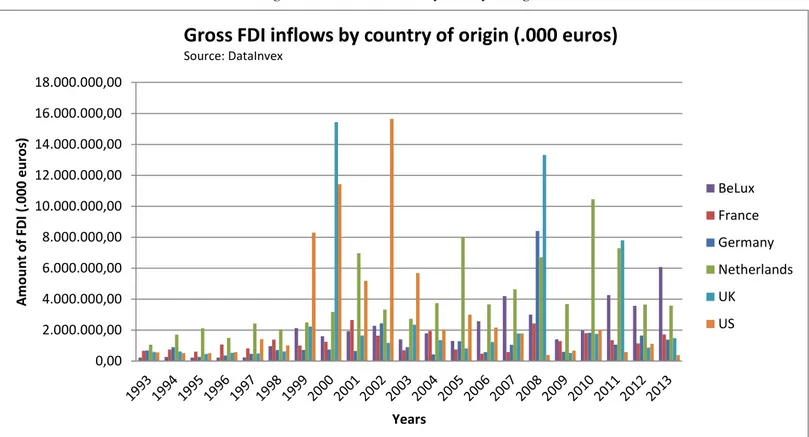

VI. Origin of the FDI in Spain

As in the case of Portugal, the overwhelming majority of the FDI comes from

Europe (almost 89% in 2009, according to Clifton et al., 2011). Over the period

1993-2013, one will consider only 5 European countries and include the US seeing the

importance of the inflows generated by this country. Figures 3 and 4 display the

necessary data.

The US represent the larger non-European investor in Spain. Three mechanisms

are involved: US firms establishing their EU headquarters in Spain, building productive

plants (in the automotive industry with Ford and GM) or using a Spanish affiliate as an