UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO CEARÁ

FACULDADE DE FARMÁCIA, ODONTOLOGIA E ENFERMAGEM PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ODONTOLOGIA

DANIELA DA SILVA BEZERRA

EFEITO DE SISTEMA ADESIVO E DE DENTIFRÍCIO FLUORETADOS NO DESENVOLVIMENTO DE CÁRIE AO REDOR DE RESTAURAÇÕES COM E SEM

FENDA MARGINAL EM ESMALTE E DENTINA: ESTUDO in situ

FORTALEZA

DANIELA DA SILVA BEZERRA

EFEITO DE SISTEMA ADESIVO E DE DENTIFRÍCIO FLUORETADOS NO DESENVOLVIMENTO DE CÁRIE AO REDOR DE RESTAURAÇÕES COM E SEM

FENDA MARGINAL EM ESMALTE E DENTINA: ESTUDO in situ

Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Odontologia da Faculdade de Farmácia, Odontologia e Enfermagem da Universidade Federal do Ceará como um dos requisitos para a obtenção do Título de Mestre em Odontologia.

Área de concentração: Clínica Odontológica

Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Lidiany Karla Azevedo Rodrigues

B469e Bezerra, Daniela da Silva

Efeito de sistema adesivo e de dentifrício fluoretados no desenvolvimento de cárie ao redor de restaurações com e sem fenda marginal em esmalte e dentina: estudo in situ / Daniela da Silva Bezerra. – Fortaleza-Ce, 2010.

55 f. : il.

Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Lidiany Karla Azevedo Rodrigues Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal do Ceará. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Odontologia; Fortaleza-Ce, 2010.

1. Cárie Dentária 2. Cimentos dentários 3. Flúor 4. Falha da Restauração Dentária I. Rodrigues, Lidiany Karla Azevedo (Orient.) II. Título.

DANIELA DA SILVA BEZERRA

EFEITO DE SISTEMA ADESIVO E DE DENTIFRÍCIO FLUORETADOS NO DESENVOLVIMENTO DE CÁRIE AO REDOR DE RESTAURAÇÕES COM E SEM

FENDA MARGINAL EM ESMALTE E DENTINA: ESTUDO in situ

Dissertação apresentada à Coordenação do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Odontologia da

Universidade Federal do Ceará como requisito parcial para obtenção do Título de Mestre em Odontologia.Área de concentração: Clínica Odontológica.

Aprovada em: ____/____/____

BANCA EXAMINADORA

___________________________________________ Profa. Dra. Lidiany Karla Azevedo Rodrigues (Orientadora)

Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC)

___________________________________________ Profo. Dr. Carlos Augusto de Oliveira Fernandes

Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC)

___________________________________________ Profa. Dra. Marinês Nobre dos Santos Uchôa

À Deus, grande e venerado pai, a quem eu entrego cegamente meus passos e minha vida.

AGRADECIMENTOS ESPECIAIS

À Profa. Dra. Lidiany Karla Azevedo Rodrigues, minha orientadora, pela sua dedicação em todos os momentos do mestrado e pelo exemplo de professora, pesquisadora e mulher. Obrigada pela paciência, firmeza de propósitos e por acreditar em mim.

À companheira de trabalho Maria Denise Rodrigues de Moraes, pela sua parceria e ajuda direta nesta pesquisa, que, mesmo nos momentos mais difíceis, manteve-se firme no propósito de pesquisadora e amiga.

À tia e madrinha Maria das Dores Dutra pela torcida, pela energia positiva e por todo o apoio durante minha vida. Obrigada pelo exemplo de vida e de ser humano que és.

Aos meus avós Adelaide Ferreira da Silva, Pedro Pereira da Silva, Francisca Pereira Dutra (in memoriam) e Valdemar Bezerra Sampaio. Obrigada por tudo!

AGRADECIMENTOS

À Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) por meio do seu Magnífico Reitor Prof. Dr. Jesualdo Pereira Farias.

À Faculdade de Farmácia, Odontologia e Enfermagem da Universidade Federal do Ceará através de sua diretora Neiva Francenely Cunha Vieira.

À coordenadora do curso de Odontologia Prof. Dra. Ma Eneide Leitão de Almeida.

Ao Coordenador e vice-coordenador dos Cursos de Pós-Graduação da Faculdade de Odontologia da UFC, Prof. Dr. Sérgio Lima Santiago e Prof Dr. José Jeová Siebra Moreira Neto, grandes incentivadores de esforços!

Aos professores do Mestrado em Odontologia pelo incentivo à minha formação.

Aos funcionários do programa de pós-graduação Germano Mahlmann Muniz Filho (in memorian) e Lúcia Ribeiro Marques Lustosa, pela constante disponibilidade.

Aos funcionários do Curso de Odontologia, sempre tão dispostos a ajudar e solucionar problemas.

Ao técnico em prótese dental do Curso de Odontologia, Antônio Carlos de Oliveira Filho, pela confecção dos dispositivos intra-orais usados nesta pesquisa.

Aos estimados voluntários que participaram com tanto empenho desta pesquisa.

Aos alunos de iniciação científica, Diego Martins de Paula, João Paulo Saraiva Wenceslau, Diego da Costa Goes, Bruna Melo e todos os outros alunos que contribuíram para o bom andamento do trabalho.

Às amigas Fátima Maria Cavalcante Borges, Juliana Marques Paiva, Mary Anne Sampaio de Mello, Rosane Pontes de Sousa, Suyanne Maria Luna Cruz e Vanara Passos Florêncio pela ajuda e pelas importantes orientações para o bom andamento desta pesquisa.

Ao aluno bolsista da Embrapa, Daniel Cordeiro da Costa; ao professor de Física Eduardo Bedê e ao aluno de doutorado em Química Paulo Naftali Cassiano, pela ajuda no preparo das amostras e aquisição de imagens de microscopia eletrônica de varredura no departamento de Física da UFC.

À professora Lívia Maria Andaló Tenuta pela orientação nos procedimentos laboratoriais realizados na Faculdade de Odontologia de Piracicaba de São Paulo, SP.

Aos colegas de classe, Alrieta Henrique Teixeira, Ana Patrícia Souza de Lima, André Mattos Brito de Souza, Françoise Parahyba Dias, Gabriela Eugênio de Sousa Furtado, George Táccio de Miranda Candeiro, Isabela Alves Pacheco, Jorgeana Abrahão Barroso, José Luciano Pimenta Couto, Maria Denise Rodrigues de Moraes, Mirela Andrade Campos, Regina Cláudia Ramos Colares, Saulo Hilton Botelho Batista e Virgínia Régia Souza da Silveira, pelos momentos felizes, pelos desabafos e pelos incentivos! Valeu, mesmo!!!

Aos familiares e amigos, pela terna compreensão pelas diversas ocasiões em que tive que ausentar-me para dedicação aos estudos.

A todos aqueles que de alguma forma contribuíram para a conclusão deste trabalho.

RESUMO

Cáries secundárias podem desenvolver-se na interface dente-restauração diante da presença de fendas marginais, mas este processo poderia ser inibido pela presença de flúor. Esta pesquisa teve como objetivo avaliar, in situ, através de um delineamento cruzado, aleatorizado, boca dividida e duplo-cego, a influência do flúor proveniente de sistema adesivo autocondicionante ou dentifrício no desenvolvimento de cárie secundária em esmalte e dentina radicular ao redor de restaurações de resina composta com ou sem fenda marginal. Durante duas fases de 14 dias, 16 voluntários utilizaram dispositivos intra-orais palatinos contendo 4 blocos de dente humano compostos por uma porção de esmalte e dentina e restaurados com resina composta FiltekTM Z-250. Os blocos foram aleatoriamente divididos em 8 grupos experimentais para cada substrato (esmalte e dentina) restaurado com um dos seguintes adesivos: All Bond SETM (não fluoretado - ANF) e One Up® Bond F Plus (fluoretado - AF), com a presença de fendas marginais (G+) ou não (G-), e com o uso de dentifrício fluoretado (DF) ou placebo (DP). Os procedimentos restauradores foram realizados seguindo as instruções dos fabricantes e a fenda foi criada com a utilização de matrizes metálicas. Cada voluntário foi instruído a gotejar sobre os blocos uma solução de sacarose a 20%, 10 vezes ao dia e a usar o dentifrício padronizado 3 vezes ao dia. Ao final de cada fase clínica, os blocos dentais foram removidos e o biofilme foi coletado para a contagem de estreptococos do grupo mutans, lactobacilos e microrganismos totais, assim como para a análise da quantidade de flúor presente. A perda mineral foi analisada pelo teste de microdureza em corte longitudinal no esmalte e na dentina. A profundidade da lesão e a presença de lesão da parede foram determinadas por microscopia de luz polarizada. Os resultados foram analisados por análise de variância (ANOVA) seguindo um delineamento fatorial 2x2x2. O flúor do adesivo não ofereceu proteção contra o desenvolvimento de cárie secundária em esmalte e dentina para nenhuma das variáveis de resposta estudadas (p > 0,05). O flúor do dentifrício mostrou leve proteção contra a desmineralização em dentina (p < 0,05). Houve uma maior presença de lesão de parede, tanto em esmalte quanto em dentina (p< 0,05), em restaurações com fenda independente da presença de flúor. No entanto, em restaurações com fenda, uma maior profundidade de lesão foi observada em dentina (p <0,05). Estes resultados sugerem que o flúor do adesivo não foi capaz de inibir a desmineralização ao redor de restaurações mesmo com a presença de flúor no dentifrício. No entanto, a presença de fenda visível afeta o desenvolvimento de cárie secundária, principalmente na dentina radicular, aumentando a progressão da lesão cariosa.

ABSTRACT

Secondary caries may be developed between tooth and restoration when marginal gaps are present, however this process could be inhibited by fluoride presence. This research had as the main objective to evaluate, in situ, through a randomized, split-mouth and double-blind, cross-over design, the influence of fluoride from self-etching adhesive systems or dentifrice on the secondary caries development on enamel and root dentine around composite resin restorations with or without marginal gaps. During two phases, of 14 days each, 16 volunteers wore intraoral palatal devices containing 4 human dental slabs composed by a portion of enamel and dentine, restored with Z-250 composite resin. The slabs were randomly divided among 8 experimental groups for each substrate (enamel and dentine) restored with one of the following adhesive: All Bond SETM (no fluoride - NFA) and One Up® Bond F Plus (fluoride - FA) with (G+) or without (G-) the presence of marginal gaps and the use of fluoride dentifrice (FD) or placebo (PD). The restoration procedures were made following the manufacturers instructions and the gap was induced with the use of metallic strips. Each volunteer was instructed to drop on the slabs a 20% sucrose solution 10x/day and use the standardized dentifrice 3x/day. By the end of each clinical phase, the dental slabs were removed and the biofilm was collected for total microorganisms, mutans streptococci and lactobacilli counting, as well as for analysis of fluoride quantity present. The mineral loss was analyzed by microhardness test in a longitudinal cut on enamel and dentine. The lesion depth and presence of the wall lesion were determined by polarized light microscopy. The results were analyzed by ANOVA, following a factorial delineation of 2x2x2. The fluoride from the adhesive did not provide any protection against secondary caries development for enamel and dentine and for none of the studied response variables (p > 0.05). The fluoride from the dentifrice showed a little protection for demineralization in dentin (p<0.05). There was more wall lesion presence, either on enamel or on dentine (p < 0.05), on restorations with gap irrespective of fluoride presence. However, on gap restorations, a bigger depth of lesion was observed only on dentine (p < 0.05). These results suggest that the fluoride from the adhesive was not able to inhibit demineralization around restorations, even in the fluoride dentifrice presence. Nevertheless, the presence of a visible gap affects the secondary caries development, mainly on root dentine, increasing the progression of caries disease.

SUMÁRIO

1 INTRODUÇÃO GERAL ... 12

2 PROPOSIÇÃO ... 15

2.1 Objetivo geral ... 15

2.2 Objetivos específicos ... 15

3 CAPÍTULO ... 16

4 CONCLUSÃO GERAL ... 39

REFERÊNCIAS ... 40

APÊNDICES ... 44

1 INTRODUÇÃO GERAL

O desenvolvimento de materiais restauradores adesivos permitiu a introdução de novos conceitos e técnicas conservativas na odontologia restauradora, possibilitando a introdução de procedimentos minimamente invasivos e reduzindo as perdas de integridade das superfícies dentárias decorrentes de preparos cavitários extensos (HARA et al., 2005).

Apesar disso, algumas intercorrências podem acontecer, como a formação de cárie secundária que é considerada a causa mais freqüente das falhas restauradoras (BURKE et al., 2001; MJÖR; TOFFENETTI, 2000), e é responsável por aproximadamente dois terços das trocas de restaurações (MJÖR, 2005). Essa patologia é caracterizada por uma lesão localizada ao longo da margem de uma restauração e é composta por duas partes: uma lesão externa e uma lesão de parede (HALS; NERNAES, 1971; KIDD, 1976; FONTANA; GONZÁLEZ-CABEZAS, 2000).

Embora haja discussões acerca da etiologia microbiana desta lesão, há fortes indícios de semelhança entre a composição bacteriana desta com a da cárie inicial (WALTER et al.,

2007), sendo o seu início e desenvolvimento similares, apenas modulado por condições específicas, tais como localização, propriedades e características das restaurações (MJÖR; TOFFENETTI, 2000; THYLSTRUP, 1998). Os defeitos marginais próximos ao esmalte e dentina, tais como a presença de fendas entre a parede cavitária e a restauração, porosidades e fraturas, podem contribuir para um maior acúmulo de biofilme dental e invasão bacteriana (BOLLEN et al., 1997), e para um aumento da desmineralização ao longo da parede cavitária restaurada (THYLSTRUP, 1998). Somando-se a isso, há o fato de que mesmo os sistemas adesivos que apresentam altos valores para a resistência de união não são capazes de evitar a ocorrência de microfendas entre o remanescente dental e a restauração (CHIGIRA et al.,

1994).

entre presença de fenda marginal e estas lesões (TOTIAM et al., 2007; OKIDA et al, 2008; CENCI et al, 2009).

Apesar disso, sendo a cárie secundária modulada pela presença de biofilme bacteriano acumulado sobre o dente, restauração ou no interior das fendas, fatores relacionados a esse biofilme seriam bastante relevantes para o desenvolvimento dessas lesões. Dentre esses, a presença de fluoreto (F) no biofilme, fornecido regularmente por dentifrício fluoretado ou liberado por material restaurador, poderia interferir no desenvolvimento das lesões, bem como na relevância da presença desses defeitos marginais (CENCI et al., 2008).

Já é bem documentado que o flúor é um agente anticárie que age através de uma variedade de mecanismos, incluindo a redução da desmineralização e aumento da remineralização, a interferência na formação da placa dental e a inibição do crescimento e metabolismo microbiano (FEJERSKOV; CLARKSON, 1996; TEN CATE; FEATHERSTONE, 1996). A liberação de flúor de materiais restauradores pode afetar a formação de cáries através de todos esses mecanismos. Dessa forma, vários materiais que liberam flúor têm sido propostos com o objetivo de auxiliar na prevenção da cárie secundária, onde podem ser enquadrados os sistemas adesivos que contém flúor em sua composição (WIEGAND et al., 2007).

A partir da evolução dos sistemas adesivos, foram lançados no mercado os sistemas autocondicionantes, os quais tem passos clínicos mais simplificados. Nesses sistemas o

primer é acidificado, sendo composto por uma mistura aquosa de monômeros acídicos funcionais, geralmente ésteres de ácido fosfórico (VAN MEERBEEK et al., 2003; PERDIGÃO et al., 2003). Os monômeros tem a propriedade de dissolver parcialmente a hidroxiapatita e incorporar a smear layer ao substrato desmineralizado, ao passo que infiltram a rede colágena com o primer e monômeros resinosos, resultando na obliteração dos túbulos dentinários (VAN MEERBEEK et al., 2003; LEINFELDER; KURDZIOLEK, 2003; PERDIGÃO et al., 2004).

por sua vez, ao se infiltrarem entre a restauração e a parede cavitária, também poderiam induzir a formação de cárie secundária, sensibilidade pulpar e até mesmo danos irreversíveis à polpa (IMAZATO et al., 1998; ÖZER et al., 2005).

Dessa forma, foram lançados no mercado os adesivos autocondicionantes com flúor em sua composição, proporcionando a esses sistemas adesivos uma possível atividade anticárie (ITOTA et al., 2002; SAVARINO et al., 2004). Os sistemas adesivos com flúor podem liberar íons para as paredes cavitárias do preparo, os quais penetram e se difundem na parede dentinária (FERRACANE et al., 1998; HAN et al., 2002). Ferracane et al (1998), encontraram evidência de íons flúor na camada híbrida, liberados pelo sistema adesivo presente na interface dente/restauração. Apesar disso, outros autores (HARA et al., 2005; PERIS et al., 2007) não encontraram significativa evidência de inibição do processo de desmineralização quando adesivos contendo flúor foram utilizados.

A influência dos materiais restauradores e dos sistemas adesivos com possível potencial anticárie na dinâmica do processo de cárie secundária tem sido estudada, principalmente, em modelos in vitro, que simulam o desafio cariogênico, com o objetivo de induzir lesões com características comparáveis às encontradas in vivo. Entretanto, faz-se necessário a realização de estudos que forneçam condições mais próximas à dinâmica do meio bucal para avaliar a influência da utilização desses sistemas no mecanismo de formação e constituição da placa bacteriana, e no processo inicial de desmineralização do esmalte e dentina, frente ao desafio cariogênico. Por isso a importância de estudos que sejam realizados na própria cavidade bucal utilizando os modelos in situ, os quais permitem as observações sem os empecilhos técnicos e éticos dos estudos in vivo (ZERO, 1995).

2 PROPOSIÇÃO

Os objetivos do presente estudo foram:

2.1 Objetivo geral

Avaliar, por meio de um estudo “in situ”, a influência da utilização de sistema adesivo autocondicionante com e sem flúor, combinado ou não com o uso de dentifrício fluoretado, no desenvolvimento de cárie em esmalte e dentina radicular humana, adjacentes à restauração de resina composta com ou sem fenda marginal.

2.2 Objetivos específicos

- Avaliar, por meio de teste de microdureza, a desmineralização em esmalte e dentina, mediante a presença ou não de flúor proveniente de sistema adesivo ou de dentifrício

- Determinar a presença e espessura de lesão de parede e a profundidade de lesão externa por meio de microscopia de luz polarizada.

- Avaliar a influência do flúor, presente no adesivo e no dentifrício, na composição microbiológica do biofilme dental formado.

3 CAPÍTULO

Esta dissertação está baseada no Artigo 46 do Regimento Interno do Programa de Pós- Graduação em Odontologia da Universidade Federal do Ceará, que regulamenta o formato alternativo para dissertações de Mestrado e permite a inserção de artigos científicos de autoria e co-autoria do candidato. Por se tratarem de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos, ou parte deles, o projeto de pesquisa deste trabalho foi submetido à apreciação do Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade Federal do Ceará, tendo sido aprovado sob protocolo nº 84/09 (anexo B). Assim sendo, esta dissertação de mestrado é composta por um capítulo que contém um artigo que será submetido para publicação no periódico “Caries Research”, e que será previamente analisado e corrigido por um corretor da língua inglesa.

Capítulo 1

In situ effect of fluoride from adhesive system and dentifrice on caries formation

around restorations with gap in enamel and dentine

In situ effect of fluoride from adhesive system and dentifrice on caries formation around

restorations with gap in enamel and dentine

Bezerra DS1, Moraes MDR1, Rodrigues LKA1

1

Faculty of Pharmacy, Dentistry and Nursing, Federal University of Ceará, Fortaleza, Ce, Brazil

Running Title – Fluoride and gap on secondary caries development

Key words – Self-etch adhesive systems, Fluoride, Gaps, Demineralization, Secondary Caries

Full address of the author to whom correspondence should be sent: Lidiany Karla Azevedo Rodrigues

Faculdade de Farmácia, Odontologia e Enfermagem Dentística Operatória Clínica

Rua Cap. Francisco Pedro, S/N -

Bairro- Rodolfo Teófilo - CEP 60430-170 Phone #558533668410

Fax #558533668232 Fortaleza-CE

Abstract

Secondary caries may be developed between tooth and restoration when marginal gap is present, however this process could be inhibited by fluoride. Thus, a randomized double-blind crossover study was performed to evaluate in situ the effect of fluoride from dental adhesive or dentifrice, either alone or in combination, on demineralization around enamel-dentine restorations in the presence of marginal gap. In 2 phases of 14 days each, 16 volunteers wore palatal devices containing dental slabs restored with composite resin associated with fluoride adhesive system (FA) or non-F adhesive system (NA). Restorations were made without gap (G–), following the recommended procedures, or with gap (G+), in the presence of metallic strips. Plaque-like biofilm (PLB) was left to accumulate on the restored slabs which were exposed to a 20% sucrose solution 10x/day. The volunteers used a placebo (PD) or an F dentifrice (FD) 3x/day, depending on the experimental phase. Mineral loss was determined by the cross-sectional microhardness while lesion depth and wall lesion presence were determined by polarized-light microscopy. Fluoride from adhesive did not provide protection against secondary caries development (p > 0.05). FD showed a little protection in dentine (p < 0.05). Differences were found on restorations with G+ in enamel and dentine, where deeper wall lesions were found, and on dentine restorations with G+, where higher demineralization was observed (p < 0.05). Thus, the FA in the presence of FD, was unable to inhibit demineralization. However, the gap presence affects secondary caries development, mainly in root dentine, increasing caries progression.

Key words: Secondary (recurrent) caries, marginal gaps, fluoride, adhesive systems, demineralization.

Introduction

Dental caries is a localized disease resulting from local bacterial activities. Thus, marginal gaps in restorations may allow biofilm accumulation and bacterial invasion causing further demineralization along the restored tooth cavity wall [Cenci et al., 2009]. Secondary (recurrent) caries occur mainly in areas of dental plaque stagnation such as the cervical margins of restorations [Özer, 1997; Mjör and Toffenetti, 2000; Mjör, 2005]. This fact was evidenced by a cross-sectional study of treatment in practice which showed that Class II was the type of restoration that was more frequently made over and over [Sunnegardh-Gronberg et al., 2009]. This way, controlling demineralization processes in cervical area is an important clinical issue.

Available data indicate that visible gaps and marginal discrepancies between tooth and restorative materials are related to secondary caries [Totiam et al., 2007; Cenci et al., 2009]. Considering that contemporary adhesives have been reported to be incapable of preventing the occurrence of microgaps [Chigira et al., 1994; Irie et al., 2004] and that the initial gap around light-activated restorative materials may get to 100 µm [Dijkman and Arends, 1992; Irie et al., 2002; Loguercio et al., 2004; Cenci et al., 2008], preventing or slowing lesion progression down around defective restorations could reduce the rate of restoration replacement.

Fluoride plays an important role on caries control since it may interfere with its physicochemical processes [ten Cate, 1999], not only reducing the caries progression rate but also allowing the arrestment of active lesions [Nyvad and Fejerskov, 1986]. Thus, the fluoride presence from regular use of dentifrice [Hara et al., 2006] or released by dental materials [Benelli et al., 1993; ten Cate and van Duinen, 1995] could inhibit, or control secondary caries by interfering the importance of marginal gap in the etiology of this kind of lesion [Cenci et al., 2008]. So, Intending to provide fluoride to a specific site at risk of secondary caries, fluoride-releasing from adhesive systems were developed [Cenci et al., 2008].

fuoride in the adhesive system, (2) fluoride in the dentifrice or (3) the presence of induced marginal gap on the response of the assessed variables.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Aspects

The study protocol was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Medical School from Federal University of Ceará (protocol #84/09). Eighteen healthy adults (10 females and 8 males), aged from 19 to 36 years old, with normal salivary flow rates, good general and oral health, able to comply with the experimental protocol, were invited to participate in this study. They were not admitted to the study if any of the following criteria were present: active caries lesions, use of fixed or removable orthodontic devices, use antibiotics during the 2 months prior to the study, insufficient address for following-up, unwillingness to return for following-up, or with residence outside the city of Fortaleza. All the 18 volunteers agreed to participate and signed an informed written consent prior to enrollment in the study. One volunteer gave up two days before the beginning of the experimental phase, because he began using antibiotics. Another volunteer did not use the palatal device like instructions. Therefore, 16 volunteers participated from the beginning to the end of the study.

Experimental design

This in situ study involved a randomized, double-blind, split-mouth, crossover design for caries induction by PLB accumulation and sucrose exposure during two phases of 14 days. The factors under evaluation as a factorial 2 x 2 x 2 design were: (1) adhesive system in 2 levels: fluoride (FA) and non-fluoride (NA); (2) gap presence: with (G+) and without gap (G-); (3) F treatment in 2 levels: placebo dentifrice (PD) and FD (1.100 µg F/g as NaF, silica-based). Therefore, the 8 experimental subsets obtained from the association of these factors were assigned to the volunteers.

consequently, fluoride adhesive system on the opposite side (split-mouth design) [Hara et al., 2003; Sousa, et al., 2009]. Thus, half of the volunteers had slabs restored with fluoride adhesive system put on the right side of the palatal appliance and the other half had it put on the left side of it. The side of placement for F releasing restored slabs was randomly allocated for each volunteer by using the coin flipping method. The head face of the coin assigned the fluoride adhesive system being placed at the right side and the tail face, the contrary choice. This way of submitting dental slabs placed in the same device for different treatments was previously tested and proved being safe to non-interference of the effect of treatments each other [Sousa et al., 2009]. Within each side of the palatal device, the positions of the specimens were randomly determined according to a computer generated randomization list [Sousa et al., 2009].

After each phase, the PLB formed on the slabs was collected for mutans streptococci (MS), lactobacilli (LB) and total microorganisms (TM) counts, and F concentration in the solids of biofilm. Integrated mineral losses in enamel and dentine adjacent to the restorations at one distance and several depths from the tooth-restoration interface were assessed from microhardness analysis. The presence and thickness of wall lesions, and depth of outer lesions were determined by polarized light microscopy.

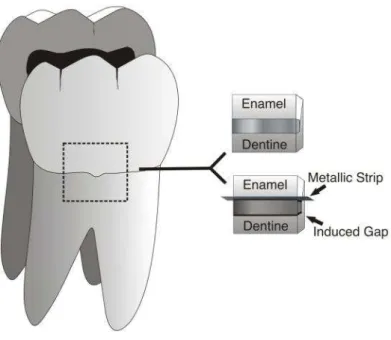

Enamel-dentine slabs and restoration of slabs

Before placement of restorations, all slabs surfaces were cleaned with rotating brushes and abrasive paste and washed with distilled water. Tooth preparations were conditioned with one of these self-etch adhesive systems, following the manufacturer’s instructions: All Bond SETM (Bisco, Shaumburg, IL, USA), non-fluoridated adhesive, and One Up® Bond F Plus (Tokuyama Dental Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), fluoridated adhesive. Then, the slabs were restored with three increments of composite resin Z-250 (3M ESPE-Dental Products, St. Paul, MN, USA) which were light-polymerized by using a LED, light-curing unit (Elipar™ FreeLight 2 LED,3M ESPE). According to the group, visible gaps were created by inserting metallic strips (TDV Dental Ltda., Pomerode, SC, Brazil) with standard width (2.0 mm) and a 50 µm thickness at the tooth/resin interface (Figure 1) after bonding procedures and prior to the restorative material placement. The gap width was checked in 10 additional slabs, under magnification of 30x by scanning electron microscopy (SEM- TESCAN Scanning Electron Microscope Model Vega/ XMU, Brno, Czech Republic) and determined to be 144.7±9.7 µm.

The slabs were then polished with aluminum oxide discs (Sof-Lex disk system 3M ESPE) for 15 seconds each one. Afterwards, all slabs were stored in 100% humidity for 24 hours and put in the palatal appliances for in situ cariogenic challenge.

Preparation of the palatal devices

For each volunteer, an acrylic custom-made palatal device was made, in which 4 cavities (6 × 6 × 3 mm³) were prepared on the left and right sides, and into each of them one slab was placed. In order to allow biofilm accumulation and protect it from mechanical disturbance, a plastic mesh was positioned on the acrylic resin leaving a 1-mm space from the slab surface [Benelli et al., 1993].

Intra-oral phase

During the lead-in and washout periods (7 days), as well as throughout each experimental phase, the volunteers brushed their teeth using the phase-designed dentifrice (NF or FD) (Fórmula & Ação Dentistry Product, São Paulo, SP, Brazil). No restrictions were made with regard to the volunteers' diet, but they were instructed to consume fluoridated water (0.7 mg F/L). They should wear the appliances all time, except during meals [Cury et al., 2000]. When removed, the devices were kept most in plastic boxes to keep the bacteria biofilm viable [Zero, 2006].

20% sucrose solution onto each mesh that was above the slab, 10x/day at predetermined times (8:00, 9:30, 11:00, 12:30,14:00, 15:30, 17:00, 18:30, 20:00, 21:30 h). Before replacing the palatal appliance in the mouth, a 5-min waiting time was standardized for sucrose diffusion into PLB. The dentifrice treatment was performed 3x/day after mealtimes, when volunteers habitually performed their oral hygiene. The appliances were extra-orally brushed, except on the slab area, and volunteers were asked to brush carefully over the covering meshes, to avoid disturbing PLB.

Microbiological Analysis

In each phase, on the 14th day, approximately 12 hours after the last application of sucrose solution and dentifrice, the volunteers stopped wearing the intraoral device. The plastic mesh was removed and the PLB formed on the specimens was collected with sterilized plastic curettes. The biofilm was weighed (± 1 mg) in pre-weighed microcentrifuge tubes, to which a 0.9% NaCl solution was added (1 mL/mg biofilm). The tubes were stirred during a 2-min period in a Disrupter Genie Cell Disruptor (Precision Solutions, Rice Lake, WI, USA) with three 0.1-mm-diameter glass beads to detach the bacterial cells. Afterwards, the suspension was serially diluted (1:10, 1:100, 1:1000, 1:10000, 1:100000 and 1:1000000) in a 0.9% NaCl solution. In order to assess the microorganism viability, samples were plated in triplicate in mitis salivarius agar containing 20% sucrose plus 0.2 bacitracin/ml, to determine MS; and Rogosa agar supplemented with 0.13 % glacial acetic acid to assess the number of colony-forming units (CFU) of LB; and blood agar plus 5% sheep blood to assess TM. The plates were incubated for 48h at 37°C in an incubator at a 10% CO2 atmosphere (CO2

Incubator Thermo electron corporation Waltham, MA United States). Representative colonies with typical morphology of MS and LB were counted by using a colony counter. The results were expressed in a CFU/mg dental biofilm (wet weight).

Cross-section Microhardness (CSMH)

120, 140 and 180 µm from the outer enamel and dentine. The integrated demineralization (ΔS) was calculated according to Sousa et al. [2009].

Polarized-light microscopy analysis

The presence and thickness of wall lesion and outer lesions were measured by using polarized-light microscopy images (DM LSP, Leica, Wetzlar GmbH, Germany) and software Motic Image Plus® (Motic, Hong Kong, China). A water-cooled diamond saw and a cutting machine were used (IsoMet Low Speed Saw, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA) to cut each slab, which was reduced by hand polishing to 100 μm ± 20 [Grossman and Matejka, 1999; Hsu et al., 1998]. The sections were embedded in deionized water and mounted in glass-slides to be analyzed in the polarized-light microscope [Hara et al., 2005]. The images taken with 10x increasing lens were transferred to the computer. The distance between the tooth surface and the lower limit of the lesion was measured in the margin of restoration, when wall lesion (WL) was present. Similarly, at distances of 30 and 100 μm from the restoration, measures of outer lesion depth (OL) were performed and used to determine the average from these distances.

Fluoride Analysis of PLB

Finished the cariogenic challenge, the PLB over the slabs were collected with sterile plastic spatula, put in sterile pre-weighed microcentrifuge tubes, identified, and dissected for a period of 24 hours. After this period the dry weight of biofilm was obtained by using a digital weighing-machine of 5 digits. The samples were treated with 100 μL of 0.5 M HCl for each 1 mg of PLB, stirred for 3 h at room temperature, centrifuged, and the collected supernatant was neutralized with 2 M NaOH (0.125 mL/10 mg biofilm wet weight) and kept frozen until analysis [Tenuta et al., 2006]. After this period, the same volume of TISSAB II (containing 20 g NaOH / L, pH 5.0) was added to the samples. Quantification of fluoride in the solution was done with an ion selective electrode connected to an ion analyzer (Orion EA-940), which was previously calibrated in a series of 8 standard solutions (from 0.025 to 32.0 ppm Fˉ), in triplicate. The readings of the samples were expressed in millivolts (mV) and transformed into μgFˉ/mV (ppm Fˉ) by linear regression of the calibration curve and calculated according to the weight of the biofilm in milligrams [Cury et al., 2000].

Data from the experiment were analyzed considering the ANOVA factorial (2x2x2) design. The volunteers were considered as statistical blocks, and type of dentifrice, type of adhesive, and gap presence as factors. The assumptions of variances equality and normal

distribution of errors were checked for each variable and, in case of assumption, violation data were transformed [Box et al., 1978]. SAS System 9.1 software (SAS Institute) was used for ANOVA. The significance level was set at 5%.

Results

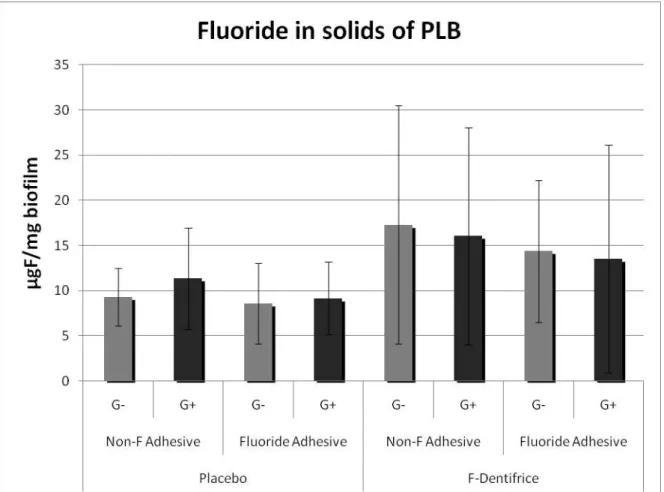

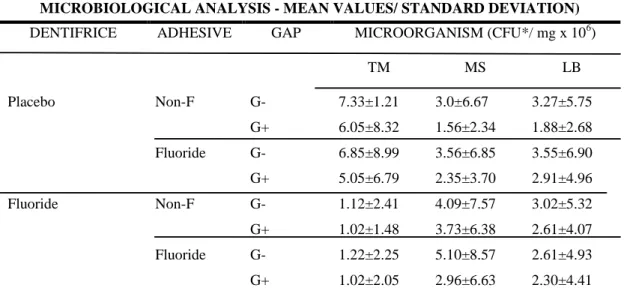

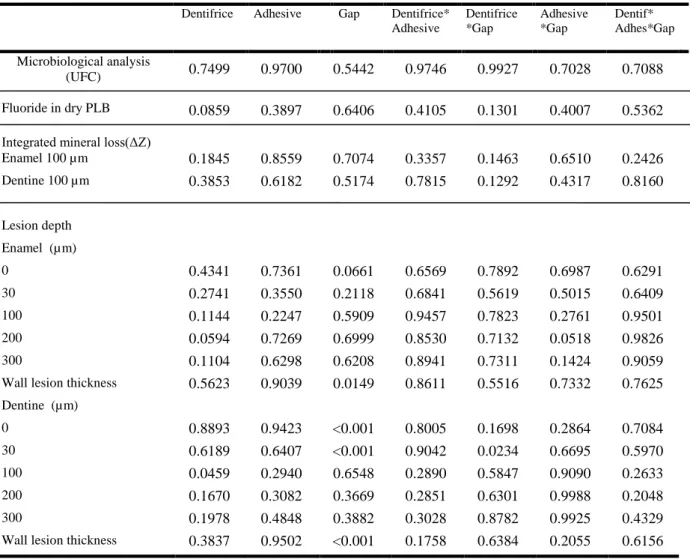

The use of fluoride in adhesive or in dentifrice did not influence on microbiology composition when demineralization was induced (p > 0.05). No statically differences were found for the microbiological analysis when the factors were studied individually (table 1) or when they were interacting each other (table 3). Regarding the presence of fluoride in the PLB, there was not statistically significant difference (p > 0.05), although, on the graphic, there was a trend of higher concentration of fluoride on the biofilm used on groups that had F-dentifrice (fig. 2).

Regarding to demineralization (lesion depth) at several distances from the margins of the restorations, ANOVA showed significant differences when the gap factor was considered, mainly in dentin (p <0.05) (table 2 and 3). In enamel, there was a thicker wall lesion when the gap was present in restorations, but, in other distances, no differences occurred. In dentin, there was a greater lesion depth at 0 and 30 µm from the restoration margin and a thicker wall lesion when gap was present on restorations (table 2). Also, there was a significant effect of dentifrice in dentin at 100 µm from the restoration and of interaction between dentifrice and gap at 30 µm (Table 3). Representative polarized-light microscopy images (fig. 3) illustrate the differences between the lesion characteristics such as presence of wall lesion in restorations with gap, and deeper lesion depth in dentine when gap was induced.

Regarding the hardness analysis (mineral loss), no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) was demonstrated at 100 µm from the restoration margin, for all studied factors.

The results revealed that the only factor that showed influence on secondary caries was the presence of gap, while the dentifrice showed only minor influence on dentin. The fluoride adhesive had no activity.

According to our results, the first null hypothesis presented was accepted in conformity to which there would not be differences on inhibitory properties of the different tested adhesives. On the other hand, the second null hypothesis that stated that there would not be differences on demineralization of used dentifrices was accepted to enamel but it was rejected for dentine, since the polarized light analysis showed a small protective effect from F-dentifrice. The last null hypothesis stated, according to which there would not be differences on demineralization around restorations with or without visible gaps, was rejected, since the polarized light analysis showed that there were a higher caries presence around restorations with gap.

The presence of gap is one of the factors related to secondary caries formation in enamel and dentine regardless the size, despite the fact that the greater the gap, the greater the wall lesion [Totiam et al., 2007]. The initial gap around light-activated restorative materials has been estimated to be ranging up to 100 µm, depending on the type of tooth cavity and C-factor [Irie et al., 2002; Loguercio et al., 2004; Cenci et al., 2008]. In the present study, the mean size of artificial gaps was 144.7 µm, which was closer to those findings in clinical situations and acceptable for secondary caries formation. According to the results of our study, in all situations of gap presence secondary caries occurred, which agreed with previous

in vitro researches [Papagiannoulis et al., 2002; Totiam et al., 2007; Cenci et al., 2009]. Nevertheless, these results are not supported by those showed by other in vivo [Rezwani-Kaminski et al., 2002] or in vitro studies [Kidd and O’Hara, 1990; Pimenta et al, 1995] that

have not demonstrated a clear relationship between marginal defects and secondary caries. One possible explanation may be due to experimental differences used in these studies. Rezwani-Kaminski et al. [2002] assessed retrospectively the caries susceptibility of posterior teeth with composite restorations after 18 and 20 years in patients regardless their caries activity which, in our opinion, may have under estimated the effects of gap presence. Besides, in the retrospective analysis of the latter authors three of four failures referred to class II cavities, which was the clinical situation mimicked in the current research. Regarding to this issue, Montag et al. [1998] documented a relationship between secondary caries and class II cavities too, showing that failures in this region present more possibilities of developing secondary caries.

common in root dentin, since the rate of mineral loss can be twice as fast from the root as it is from enamel [Featherstone, 1994].

Fluoride is known to inhibit the biosynthetic metabolism of bacteria, but these antimicrobial effects on caries prevention are often regarded as little or with no importance as compared to the direct interactions of fluoride with the hard tissue during caries development and progression [Wiegand et al., 2007]. These considerations confirm the results of this study, since microbiological analysis of PLB revealed no differences between studied groups (table 1). Besides, our results are supported by other in situ studies, which used fluoride restorative materials and dentifrice [Sousa et al., 2009].

Fluoride from adhesive systems was not able to inhibit demineralization around enamel-dentine restorations regardless the presence of gap or F-dentifrice use (table 2, 3). This result is in agreement with in vitro studies that showed no anticaries effect for this material [Itota et al., 2002; Hara et al., 2005; Peris et al., 2007]. This is not a surprising result inasmuch as F-releasing from adhesive systems is probably not high enough to inhibit demineralization. These findings further the belief that the amount of fluoride present in the dental material, as well as its concentration and release, are important aspects on the reduction of demineralization [Okida et al., 2008]. In addition, this result was highlighted by F-concentration in solids of PLB, which were not statically different in all cases, although it has a numerical trend to be more relevant only when F-dentifrice was used (fig. 2). Fluoride from dentifrice did not inhibit demineralization around enamel-dentine restorations, even in the presence or absence of marginal gaps or fluoride adhesive (table 2, 3). This is not in agreement with the in vitro study of Hara et al. [2002] or with the in situ study of Cenci et al. [2008], which showed that in the presence of fluoridated dentifrice, demineralization was inhibited immediately next to composite resin restorations. This surprising result may be attributed to the very high cariogenic challenge used in the present experiment (10 x/ day) and to the presence of marginal gaps, which may have made the substrates more susceptible to caries development. These factors can be considered limitations of the in situ caries model used in this research. This fact was supported by polarized light analysis that demonstrated a higher percentage of wall lesions and bigger lesion depth in restorations with gaps.

demonstrate this observation, probably, because on interface of restoration, even without gap, little irregularities that are inherent to interface (fig. 3) could contribute to high cariogenic challenge in dentine.

These results suggest that fluoride from adhesive system, either in the presence or absence of F-dentifrice, was unable to inhibit demineralization around restorations with or without marginal gaps. However, gap presence affects secondary caries development increasing caries progression, while dentifrice affects the demineralization in dentine, only when gap is not present, with a trend to inhibit its development.

References

Amaechi BT, Higham, SM, Edgar WM: Efficacy of sterilization methods and their effect on enamel demineralization. Caries Res 1998; 32: 441-446.

Benelli EM, Serra MC, Rodrigues AL Jr, Cury JA: In situ anticariogenic potential of glass ionomer cement. Caries Res 1993; 27: 280–284.

Box GEP, Hunter WG, Hunter JS: Statistics for experimenters, an introduction to design, data analysis, and model building. New York: John Wiley & Sons ,1978, 537p.

Cenci MS, Pereira-Cenci T, Cury JA, ten Cate JM: Relationship between gap size and dentine secondary caries formation assessed in a microcosm biofilm model. Caries Res 2009; 43:97– 102.

Cenci MS, Tenuta LM, Pereira-Cenci T, Del Bel Cury AA, ten Cate JM, Cury JA: Effect of microleakage and fluoride on enamel-dentine demineralisation around restorations. Caries Res 2008; 42: 369–379.

Cury JA, Rebelo MAB, Del Bel Cury AA, Derbyshire MTVC, Tabchoury CPM: Biochemical composition and cariogenicity of dental plaque formed in the presence of sucrose or glucose and fructose. Caries Research 2000; 34: 491–7.

Dijkman GE, Arends J: Secondary caries in situ around fluoride-releasing light-curing composites: a quantitative model investigation on four materials with a fluoride content between 0 and 26 vol%. Caries Res 1992; 26: 351–357.

Featherstone JDB: Fluoride, remineralisation and root caries. Am J Dent 1994; 7:271–274.

Grossman ES; Matejka JM: Histological Features of artificial secondary caries adjacent to amalgam restoration. J. Oral Rehabil 1999; 26: 737-744.

Hara AT, Magalhães CS, Serra MC; Rodrigues Jr AL: Cariostatic effect of fl uoride-containing restorative systems associated with dentifrices on root dentin. Journal of Dentistry 2002; 30: 205–212.

Hara AT, Queiroz CS, Paes leme AF, Serra MC, CURY JA: Caries progression and inhibition in human and bovine root dentine in situ. Caries Research 2003; 37: 339-344.

Hara AT, Queiroz CS, Freitas PM, Giannini M, Serra MC, Cury JÁ: Fluoride release and secondary caries inhibition by adhesive systems on root dentine. Eur J Oral Sci 2005; 113: 245–250.

Hara, AT, Turssi CP, Ando M, Gonzáles-Cabezas C, Zero DT, Rodrigues Jr. AL, Serra MC, Cury JA: Influence of fluoride-releasing restorative material on root dentine secondary caries

in situ. Caries Res 2006; 40: 435–439.

Hsu CYS, Donly KJ, Drake DR, Ewfel JS: Effects of aged fluoride-containing restorative materials on recurrent root caries. J Dent Res 1998; 77:418-25.

Irie M, Suzuki K, Watts DC: Immediate performance of self-etching versus system adhesives with multiple light-activated restoratives. Dent Mater 2004; 20:873-880.

Itota T, Nakabo S, Iwai Y, Konishi N, Nagamine M, Torii Y: Inhibition of artificial secondary caries by fluoride-releasing adhesives on root dentin. J Oral Rehabil 2002; 29: 523–527

Kidd EAM, O'Hara JW: The Caries Status of Occlusal Amalgam Restorations with Marginal Defects. J Dent Res 1990; 69: 1275 -1277.

Loguercio AD, Reis A, Schroeder M, Balducci I, Versluis A, Ballester RY: Polymerization shrinkage: effects of boundary conditions and filling technique of resin composite restorations. J Dent 2004; 32 459–470.

Mjör, IA, Toffenetti F. Secondary caries: a literature review with case reports. Quint Int 2000; 31:165-79

Mjör IA: Clinical diagnosis of recurrent caries. J Am Dent Assoc 2005; 136: 1426–1433.

Montag R, Hoyer I, Gaengler P: Longitudinal clinical 10 year results of posterior GIC ⁄ composite restorations. J Dent Res 1998; 77: 953.

Nyvad B, Fejerskov O: Active root surface caries converted into inactive caries as a response to oral hygiene. Scand J Dent Res 1986; 94:281-284.

Okida RC, Mandarino F, Sundfeld RH, de Alexandre RS, Sundfeld MLMM: In vitro -evaluation of secondary caries formation around restoration. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll 2008; 49: 121-128.

Özer L: The Relationship between Gap Size, Microbial Accumulation and the Structural Features of Natural Caries in Extracted Teeth with Class II Amalgam Restorations; master’s thesis, University of Copenhagen, 1997.

Peris AR, Mitsuia FHO, Lobo MM, Bedran-russoc AKB,. Marchib GM: Adhesive systems and secondary caries formation: Assessment of dentin bond strength, caries lesions depth and fluoride release. Dent Mater 2007; 23: 308–316.

Pimenta LA., Navarro MF, Consolaro A.: Secondary caries around amalgam restorations: J Prosthet Dent 1995; 74:219-222.

Rezwani-kaminski T, Kamann W, Gaengler P: Secondary caries susceptibility of teeth with long-term performing composite restorations. J Oral Rehabil 2002; 29: 1131–1138.

Sousa RP, Zanin ICJ, Lima JPM., Vasconcelos SMLC, Melo MAS, Beltrão HCP, Rodrigues LKA: In situ effects of restorative materials on dental biofilm and enamel demineralisation. J Dent 2009; 37: 44-51.

Sunnegardh-Grönberg K, Van Dijkena, JWV, Funegard U, Lindberg A, Nilsson M: Selection of dental materials and longevity of replaced restorations in Public Dental Health clinics in northern Sweden. Journal of Dentistry 2009; 37: 673 – 678.

ten Cate JM.: Current concepts on the theories of the mechanism of action of fluoride. Acta Odontol Scand 1999; 57:325–329.

ten Cate JM, van Duinen RN: Hypermineralization of dentinal lesions adjacent to glass-ionomer cement restorations. J Dent Res 1995; 74: 1266–1271.

Tenuta LMA., Del Bel Cury AA., Bortolin MC, Vogel GL., Cury JA: Ca, Pi, and F in the fluid of biofilm formed under sucrose. J Dent Res 2006; 85: 834-838.

Totiam P, González-Cabezas C, Fontana MR, Zero DT: A new in vitro model to study the relationship of gap size and secondary caries. Caries Res 2007; 41:467–473.

Fig. 2. Mean values (±SD) of fluoride analysis from the PLB according to groups. There was not statistically

significant difference among groups (p<0.05).

Fig.3. Representatives images illustrating, according to the gap presence, lesion development adjacent to the

Table 1. Microbiological analysis of PLB according to treatments (mean values with their

standard deviation for each analysis)

MICROBIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS - MEAN VALUES/ STANDARD DEVIATION)

DENTIFRICE ADHESIVE GAP MICROORGANISM (CFU*/ mg x 106)

TM MS LB

Placebo Non-F G- 7.33±1.21 3.0±6.67 3.27±5.75 G+ 6.05±8.32 1.56±2.34 1.88±2.68 Fluoride G- 6.85±8.99 3.56±6.85 3.55±6.90 G+ 5.05±6.79 2.35±3.70 2.91±4.96 Fluoride Non-F G- 1.12±2.41 4.09±7.57 3.02±5.32

Table 2. Demineralization (lesion depth - µm) in relation to distance from restoration margins

in enamel and dentine (Mean ±SD)

a) p < 0.05 for groups with G+ in dentine at 0 and 30 µm (greater lesion depth)

b) p < 0.05 for groups with F dentifrice in dentine at 30 µ m with G- (smaller lesion depth)

M AR GI N L OCAT ION DE NT IF RI CE AD HE S IVE GAP

DISTANCE FROM RESTORATION MARGIN (µm)

0 30 100 200 300

Enamel PD Non-F G- 145.375±150.639 138.157±140.530 91.921± 68.485 73.807±47.349 72.678±44.827

G+ 187.546±119.471 173.184±132.648 95.423± 60.230 104.423±97.989 90.969±73.248

F G- 128.383±131.420 90.183 ± 63.740 80.675±52.476 80.275±61.587 87.216 ±83.615

G+ 137.392 ± 98.872 124.615±103.379 66.761±41.872 67.233±45.267 68.558 ±38.740

FD Non-F G- 97.578 ± 49.280 85.128± 47.886 65.657±41.260 59.5±39.239 53.457±33.517

G+ 135.946 ± 95.762 117.030± 83.840 82.553±80.015 68.392±35.112 62.646±29.841

F G- 108.528 ± 62.298 100.885 ±43.247 77.278±46.678 62.485±29.277 62.728±24.982

G+ 163.169±128.571 101.784 ±88.701 54.846 ±41.233 55.953 ±34.069 65.430±48.664

Dentine PD Non-F G- 130.615±70.734 127.553±68.437 123.076±69.911 116.6 ±65.403 111.261±65.623

G+ 270.807±167.605a

198.776±157.253a 116.438±82.128 97.707±66.319 97.807±62.536

F G- 157.227± 80.331 153.636±83.089 142.663±75.447 133.472±72.887 129.1±71.705

G+ 239.484±150.676a

202.092±143.604a 139.969±75.376 121.053±65.066 114.507±59.549

FD Non-F G- 120.253±92.783 113.430±89.854b 108.830±86.188 105.115±79.458 107.576±87.332

G+ 339.925±288.271a

289.233±282.665a 123.191±81.746 107.658±60.346 102.675±59.039

F G- 137.678±112.930 114.978±81.366b 107.578±70.085 106.521±62.546 101,4±59.863

G+ 251.6±121.062a

Table 3. ANOVA results (p values)

Dentifrice Adhesive Gap Dentifrice* Adhesive

Dentifrice *Gap

Adhesive *Gap

Dentif* Adhes*Gap

Microbiological analysis

(UFC) 0.7499 0.9700 0.5442 0.9746 0.9927 0.7028 0.7088 Fluoride in dry PLB 0.0859 0.3897 0.6406 0.4105 0.1301 0.4007 0.5362 Integrated mineral loss(ΔZ) Enamel 100 µm 0.1845 0.8559 0.7074 0.3357 0.1463 0.6510 0.2426 Dentine 100 µm 0.3853 0.6182 0.5174 0.7815 0.1292 0.4317 0.8160

Lesion depth

Enamel (µm)

0 0.4341 0.7361 0.0661 0.6569 0.7892 0.6987 0.6291

30 0.2741 0.3550 0.2118 0.6841 0.5619 0.5015 0.6409

100 0.1144 0.2247 0.5909 0.9457 0.7823 0.2761 0.9501 200 0.0594 0.7269 0.6999 0.8530 0.7132 0.0518 0.9826 300 0.1104 0.6298 0.6208 0.8941 0.7311 0.1424 0.9059 Wall lesion thickness 0.5623 0.9039 0.0149 0.8611 0.5516 0.7332 0.7625 Dentine (µm)

4 CONCLUSÃO GERAL

Pode-se concluir que os sistemas adesivos autocondicionantes fluoretados foram incapazes de inibir a desmineralização ao redor de restaurações de resina composta, com ou sem a presença de fendas marginais, com ou sem a presença de dentifrício fluoretado.

O adesivo e o dentifrício fluoretados também foram incapazes de inibir o crescimento bacteriano no biofilme formado sobre os blocos. Da mesma forma, nenhum deles foi relevante para o aumento da quantidade de íon flúor no biofilme formado.

Nas condições de alto desafio cariogênico usadas no presente estudo, a presença de flúor no dentifrício apresentou leve tendência de inibição do desenvolvimento de lesões de cárie ao redor de restaurações sem fendas marginais em dentina.

REFERÊNCIAS

AMAECHI, B. T.; HIGHAM, S. M.; EDGAR, W. M. Efficacy of sterilization methods and their effect on enamel demineralization. Caries Res., v. 32, p. 441–446, 1998.

BOLLEN, C. M. L.; LAMBRECHTS, P.; QUIRYNEN, M. Comparison of surface roughness of oral hard materials to the threshold surface roughness for bacterial plaque retention: a review of the literature. Dent. Mater., v. 13, p. 258–269, 1997.

BURKE, F.J.; WILSON, N.H.; CHEUNG, S. W.; MJÖR, I. A. Influence of patient factors on age of restorations at failure and reasons for their placement and replacement. Journal of

Dentistry,v. 29, n. 5, p. 317-324, 2001.

CENCI, M. S.; TENUTA, L. M.; PEREIRA-CENCI, T.; DEL BEL CURY, A. A.; TEN CATE, J. M.; CURY, J. A. Effect of microleakage and fluoride on enamel-dentine demineralization around restorations. Caries Res., v. 42, p. 369–379, 2008.

CHIGIRA, H.; YUKITANI, W.; HASEGAWA, T.; MANABE, A.; ITOH, K.; HAYAKAWA, T.; DEBARI, K.; WAKUMOTO, S.; HISAMITSU, H. Self-etch dentin primers containing Phenyl-P. J. Dent. Res., v. 73, p. 1088-1095, 1994.

DE MUNCK, J.; VAN MEERBECK, B.; YOSHIDA, Y.; INQUE, S.; VARGAS, M.; SUZUKI, K.; LAMBRECHTS, P.; VANHERLE, G. Four year water degradation of total-etch adhesives bonded to dentine. J. Dent. Res., v.82, p. 136-140, 2003.

DÉRAND, T.; BIRKHED, D.; EDWARDSSON, S. Secondary caries related to various marginal gaps around amalgam restorations in vitro. Swed Dent. J., v. 15, p. 133-138, 1991.

FEJERSKOV, O; CLARKSON, B.H. Dynamics of caries lesion formation. In: FEJERSKOV, O.; EKSTRAND, J.; BURT, B. A. Fluoride in dentistry. Copenhagen: Munksgaard, p.187– 213, 1996.

FERRACANE, J. L.; MITCHEM, J. C.; ADEY, J. D. Fluoride penetration into the hybrid layer from a dentin adhesive. Am. J. Dent., v.11, n.1, p.23-28, feb. 1998.

GOLDBERG, J.; TANZER, J.; MUNSTER, E.; AMARA, J.; THAL, F.; BIRKHED, D. Cross-sectional clinical evaluation of recurrent enamel caries, restoration marginal integrity, and oral hygiene status. J. Am. Dent.,v. 102, p. 635–641, 1981.

GROSSMAN, E. S.; MATEJKA, J. M. Histological Features of artificial secondary caries adjacent to amalgam restoration. J. Oral Rehabil.,v. 26, p. 737-744, 1999.

HALS, E.; NERNAES, A. Histopathology of in vitro caries developing around silver amalgam fillings. Caries Res.,v.5, p. 58-77, 1971.

HAN, L.; CRUZ, E.; OKAMOTO, A.; IWAKU, M. A comparative study of fluoride-releasing adhesive resin materials. Dent. Mater.,v. 21, p. 9–19, 2002.

HARA, A. T.; QUEIROZ, C. S.; FREITAS, P. M.; GIANNINI, M.; SERRA, M. C.; CURY, J. A. Fluoride release and secondary caries inhibition by adhesive systems on root dentine.

Eur. J. Oral Sci., v.113, p. 245–250, 2005.

HARA, A. T.; TURSSI C. P.; ANDO M.; GONZÁLEZ-CABEZAS C.; ZERO, D. T., RODRIGUES JR. A. L.; SERRA M. C.; CURY J. A. Influence of fluoride-releasing restorative material on root dentine secondary caries in situ. Caries Res., v.40, p. 435–439, 2006.

HODGES, D. J.; MANGUM, F. I.; WARD, M. T. Relationship between gap width and recurrent caries beneath occlusal margins of amalgam restorations. Community Dent. Oral

Epidemiol.,v.23, p. 200–204, 1995.

IMAZATO, S.; IMAI, T; EBISU, S. Antibacterial activity proprietary self-etch primers. Am.

J. Dent., v. 11, p. 106-108, 1998.

ITOTA, T.; NAKABO, S.; IWAI, Y.; KONISHI, N.; NAGAMINE, M.; TORII, Y. Inhibition of artificial secondary caries by fluoride-releasing adhesives on root dentin. J. Oral Rehabil., v. 29, p. 523–527, 2002.

KIDD, E. A. M. Microleakage in relation to amalgam and composite restorations: a laboratory study. Br. Dent. J.,v. 141, p.305-310, 1976.

LEINFELDER, K. F.; KURDZIOLEK, S. M. Self-etching bonding agents. Compendium,v. 24, n. 6, p. 447-456, 2003.

MJÖR, I. A.; TOFFENETTI, F. Secondary caries: a literature review with case reports. Quintessence Int.,v.31, n. 3, p. 165-169, 2000.

MJÖR, I. A. Clinical diagnosis of recurrent caries. J. Am. Dent. Assoc.,v.136, p.1426-1433, 2005.

OKIDA, R. C.; MANDARINO, F.; SUNDFELD, R. H.; DE ALEXANDRE R. S.; SUNDFELD, M. L. M. M. In vitro-evaluation of secondary caries formation around restoration. Bull Tokyo Dent. Coll.,v. 49, p. 121-128, 2008.

ÖZER, F.; ÜNLÜ, N.; KARAKAYA, S.; ERGANI, O.; HADIMLI, H. Antibacterial activities of MDPB and fluoride dentin bonding agents. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Dent.,v.13, p. 139-142, 2005.

PERDIGÃO, J.; ANAUATE-NETTO, C.; LEWGOY, H. R.; DUTRA-CORREA M.; CASTILHOS N.; AMORE R. Influence of acid etching and enamel beveling on the 6-month clinical performance of a self-etch dentin adhesive. Compendium, v. 25, v. 1, p. 33-44, 2004.

PERDIGÃO, J.; GERALDELI, S.; HODGES, J. S. Total-etch versus self-etch adhesive: effect on postoperative sensitivity. Journal of the American Dental Association,v. 134, n. 12, p. 1621-1629, 2003.

PERIS, A. R.; MITSUIA, F. H. O; LOBO, M. M., BEDRAN-RUSSOC, A. K. B., MARCHIB, G. M. Adhesive systems and secondary caries formation: Assessment of dentin bond strength, caries lesions depth and fluoride release. Dent. Mater., v. 23, p. 308–316, 2007.

PIMENTA, L. A.; NAVARRO, M. F.; CONSOLARO, A. Secondary caries around amalgam restorations. J. Prosthet. Dent.,v. 74, p. 219-222, 1995.

REZWANI-KAMINSKI, T.; KAMANN, W.; GAENGLER, P. Secondary caries susceptibility of teeth with long-term performing composite restorations. J. Oral Rehabil.,v. 29, p. 1131-1138, 2002.

TEN CATE, J. M.; VAN DUINEN, R. N. Hypermineralization of dentinal lesions adjacent to glass-ionomer cement restorations. J Dent Res.,v.74, p. 1266–1271, 1995.

TEN CATE, J. M.; FEATHERSTONE, J. D. M. Physicochemical aspects of fluoride–enamel interactions. In: FEJERSKOV, O.; EKSTRAND, J.; BURT, B. A. Fluoride in dentistry. Copenhagen: Munksgaard, p. 252–72, 1996.

TEN CATE J. M. Current concepts on the theories of the mechanism of action of fluoride.

Acta Odontol Scand, v. 57, p. 325–329, 1999.

THYLSTRUP, A. How should we manage initial and secondary caries? Quintessence Int.,v. 29, p. 594–598, 1998.

TOTIAM, P.; GONZÁLEZ-CABEZAS, C.; FONTANA, M. R.; ZERO, D. T. A new in vitro model to study the relationship of gap size and secondary caries. Caries Res., v. 41, p. 467– 473, 2007.

VAN MEERBEEK, B.; DE MUNCK, J.; YOSHIDA, Y.; INOUE, S.; VARGAS, M.; VIJAY, P.; VAN LANDUYT, K.; LAMBRECHTS, P.; VANHERLE, G. Adhesion to enamel and dentin: current status and future challenges. Op. Dent., v. 283, p. 215-235, 2003.

WALTER, R.; DUARTE, W. R.; PEREIRA, P. N. R.; HEYMANN, H. O.; SWIFT, J. R. E. J.; ARNOLD, R. R. In vitro inhibition of bacterial growth using different dental adhesive systems. Op. Dent.,v. 32, n.4, p. 388-393, 2007.

WIEGAND, A.; BUCHALLA, W.; ATTIN, T. Review on fluoride-releasing restorative materials - fluoride release and uptake characteristics, antibacterial activity and influence on caries formation. Dent. Mater.,v. 23, p. 343-362, 2007.

ZERO D. T. In situ caries models. Discussion. Adv Dent Res.,v. 9(3), p. 214-234, nov. 1995.

ZERO D. T. Dentifrices, mouthwashes, and remineralization/caries arrestment strategies.

APÊNDICE C – Análise de dentifrício

Triplicata Pesar 3x

( +/- 90 a 110 mg)

FT Suspensão 0,25 ml suspensão

+ 0,25 HCl 2M

0,50 ml NaOH M +

Centrifugar 10 minutos a 3.000 rpm 1,0 ml TISAB II

*

Ler

ppt Sobrenadante

(desprezar)

FI FST

0,25 ml sob 0,25 ml sob

+ +

1,0 ml TISAB II 0,25 ml HCl 2M

+ 0,50 ml NaOH M

+ 0,50 ml NaOH M

0,25 ml HCl 2M * +

1,0 ml TISAB II *

Ler Imediatamente Ler

*

o pH deve estar entre 5,0 e 5,5FT= FST + Fins

FST= MFP + FI MFP= FST - FI

Fins = FT - FST

%Fins = FSP x 100

FT

Análise de Dentifrício

Pesar em tubo de centrífuga suspender bem vigorosamente em 10 ml de H2O D D

dosagem em duplicata

1h; 45ºC

1h; 45ºC

duplicata

FT = Flúor total; FI= Flúor iônico; FST= Flúor solúvel total FT = FST + F ins

FST = MFP +FI

MFP = FST – FI

F ins = FT – FST

% F ins = FSP/FT x 100

Centrifugar por 10 min a 3000 rpm

M

APÊNDICE D – Método de extração para análises bioquímicas do Biofilme Dental

100 µL de HCl 0,5 M / 1 mg de placa* (se o peso < 1 mg = 100 µL) Homogeneizar (vortex)

3 h agitação no homogeinizador TA ( a cada 1h agitar no vórtex) Centrifugação 3 min. 10.000g TA

ppt 1 sob 1

Armazenar para posterior descarte Transferir para outro ependorf Congelar até o momento de dosar

dosar

FLÚOR (após neutralizar com Tisab com NaOH)

Método de Extração para Análises Bioquímicas do Biofilme Dental

APÊNDICE F – Informações e consentimento pós-informação para participação em

pesquisa – aos voluntários que utilizaram os dispositivos intra-orais palatinos

Você está sendo convidado para participar de uma pesquisa. Porém você não deve participar contra a sua vontade.

Leia atentamente as informações abaixo e faça qualquer pergunta que desejar para os devidos esclarecimentos.

Título da Pesquisa - “EFEITO DE SISTEMAS ADESIVOS

AUTOCONDICIONANTES COM E SEM FLÚOR NO DESENVOLVIMENTO DE CÁRIE SECUNDÁRIA EM ESMALTE E DENTINA: ESTUDO in situ”

Objetivo da Pesquisa - Avaliar o efeito da utilização de sistemas adesivos

autocondicionantes com e sem flúor no desenvolvimento de cárie secundária em esmalte e dentina adjacentes a restaurações com fenda marginal.

Justificativa - A cárie dental ainda está entre as doenças mais relevantes em

termos de saúde pública, principalmente nos países em desenvolvimento. Grupos de crianças continuam apresentando alta atividade da doença. Em termos mundiais, cerca de 20 a 25% das crianças e adolescentes apresenta 60 a 80% do total de cárie da população. Tal fato enfatiza a necessidade de se aperfeiçoar métodos preventivos e investigativos já existentes, com a introdução de técnicas inovadoras que possam agir como coadjuvantes na prevenção e controle da cárie dental neste segmento da população.

Entretanto, devido a razões éticas e às vantagens de um melhor controle experimental das variáveis, além de maior custo efetividade, parece desejável a utilização de modelos in situ para testar instrumentos e técnicas antes da realização de extensos e dispendiosos estudos clínicos.

Você utilizará durante duas etapas, cada uma com duração de 14 dias, um dispositivo intra-oral palatino, contendo 4 blocos de dente humano hígido.

Em um período anterior ao início da primeira fase do experimento (7 dias), você deverá fazer uso do dentifrício fluoretado pré-determinado, a fim de padronizar as concentrações de flúor na saliva. Após esta fase, você deverá passar a utilizar o outro dentifrício (não-fluoretado) por mais sete dias, para que, então, você possa iniciar a segunda fase de experimento.

a) Na fase clínica: Todos os blocos dentais contidos no dispositivo deverão ser gotejados com a solução de sacarose a 20%, dez vezes ao dia respeitando o horário pré-determinado pelo pesquisador (8:00, 9:30, 11:00, 12:30, 14:00, 15:30, 17:00, 18:30, 20:00 e 21:30 h). Após 5 minutos do gotejamento (uma gota sobre cada bloco dental), o dispositivo deverá ser recolocado na boca sem ser lavado.

b) Utilizar o dispositivo intra-oral palatino diariamente, inclusive para dormir;

c) Remover o dispositivo intra-oral durante as refeições ou ingestão de qualquer bebida ácida, porém conservando-o no estojo fornecido e em ambiente úmido (gaze umedecida) com o objetivo de manter as bactérias da placa viáveis;

d) Fazer uso do dentifrício padronizado para cada fase três vezes ao dia durante a escovação. Durante a escovação, o dispositivo deverá ser removido e os voluntários deverão limpar seus aparelhos cuidadosamente para evitar a remoção do biofilme dental formado sobre os blocos. O tempo de escovação do dispositivo e dos dentes não deve exceder a 3 minutos e a região da tela deve ser escovada delicadamente para evitar remoção ou perturbação da placa bacteriana. Desses 3 minutos, 2 serão usados para a higienização bucal e o outro restante para e escovação do dispositivo. Serão realizadas 3 escovações por dia, perfazendo um total de 42 escovações. Uma vez que o desafio cariogênico é conferido pelo gotejamento da solução de sacarose não é necessária a restrição de refeições dos voluntários durante o estudo.

e) Fazer uso de água fluoretada de abastecimento de Fortaleza (0,7 ppm F).

Desconfortos e Riscos