ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

International

Journal

of

Biological

Macromolecules

jo u r n al hom e p ag e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / i j b i o m a c

First

isolation

and

antinociceptive

activity

of

a

lipid

transfer

protein

from

noni

(

Morinda

citrifolia

)

seeds

Dyély

C.O.

Campos

a,

Andrea

S.

Costa

a,

Amanda

D.R.

Lima

a,

Fredy

D.A.

Silva

a,

Marina

D.P.

Lobo

a,

Ana

Cristina

O.

Monteiro-Moreira

b,

Renato

A.

Moreira

b,

Luzia

K.A.M.

Leal

c,

Diogo

Miron

c,

Ilka

M.

Vasconcelos

a,

Hermógenes

D.

Oliveira

a,∗aDepartmentofBiochemistryandMolecularBiology,FederalUniversityofCeará,CampusdoPiciProf.PriscoBezerra,60440-900Fortaleza,CE,Brazil bNUBEX—NúcleodeBiologiaExperimental,CentrodeCiênciasdaSaúde,UniversidadedeFortaleza—UNIFOR,60811-905Fortaleza,CE,Brazil cDepartmentofClinicalandToxicologicalAnalysis,FacultyofPharmacy,FederalUniversityofCeará,Fortaleza,CE,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received4November2015

Receivedinrevisedform7January2016 Accepted8January2016

Availableonline16January2016

Keywords: MorindacitrifoliaL. Rubiaceae Noni

Proteinisolation Antinociceptiveactivity Lipidtransferprotein

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Inthisstudyanovelheat-stablelipid transferprotein, designatedMcLTP1,waspurifiedfromnoni (Morindacitrifolia L.) seeds,usingfour purificationstepswhichresulted inahigh-purified protein yield (72mg McLTP1 from100g of noni seeds).McLTP1 exhibited molecularmassesof 9.450and 9.466kDa,determinedbyelectrosprayionisationmassspectrometry.TheN-terminalsequenceofMcLTP1 (AVPCGQVSSALSPCMSYLTGGGDDPEARCCAGV),asanalysedbyNCBI-BLASTdatabase,revealedahigh degreeofidentitywithotherreportedplantlipidtransferproteins.Inaddition,thisproteinprovedto beresistanttopepsin,trypsinandchymotrypsindigestion.McLTP1givenintraperitoneally(1,2,4and 8mg/kg)andorally(8mg/kg)causedaninhibitionofthewrithingresponseinducedbyaceticacidin mice.Thisproteindisplayedthermostability,retaining100%ofitsantinociceptiveactivityafter30min incubationat80◦C.PretreatmentofmicewithMcLTP1(8mg/kg,i.p.andp.o.)alsodecreasedneurogenic andinflammatoryphasesofnociceptionintheformalintest.Naloxone(2mg/kg,i.p.)antagonisedthe antinociceptiveeffectofMcLTP1suggestingthattheopioidmechanismsmediatetheanalgesicproperties ofthisprotein.

©2016ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved.

1. Introduction

MorindacitrifoliaL.(Rubiaceae),aplantspeciesoriginatingfrom

Tropical Asia, has beenused for millennia as a sourceof food

and fabricdyes, as well asto treat disorders suchas diabetes,

rheumatoidarthritis, highblood pressure,inflammationandfor

painmanagement[1–3].Inadditiontoitsusein folkmedicine,

thereisalsoalotofevidenceofbiologicalactivityinvariousinvitro

andinvivoassaysystems[4–8].

Asaresultofvariousphytochemicalinvestigations,morethan

200secondarymetaboliteshavebeenidentifiedfromnonifruits,

roots, seeds and leaves, including anthraquinones, flavonoids,

polysaccharides, glycosides, iridoids, lignans and triterpenoids,

withthemostrepresentativebeingscopoletin,rutin,ursolicacid,

-sitosterol,asperulosideanddamnacanthal.Someofthese

com-∗Correspondingauthor.Fax:+558533669139. E-mailaddress:hermogenes@ufc.br(H.D.Oliveira).

poundshavebeensuggestedtobethesourcesofnoni’sbiological

andinvitroactivity[9–12].

Althoughnonibark,stems,leavesandfruitshave beenused

traditionallyformanydiseases,thereisalimitedamountof

infor-mationontherapeuticpropertiesof noniseeds.Air-dried seeds

constitute2.5%ofthefruit’stotalweight,howeverduringthe

pro-ductionofnonifruitpureetheyarediscarded[13].Inaddition,West

etal.[14]demonstratedthatnoniseedextractdidnotdisplayany

signoftoxicityinasubacute(28day)oraltoxicitytestin

Sprague-Dawleyrats,anddidnotexhibitgenotoxicpotentialinaprimary

DNAdamagetestinEscherichiacoliPQ37.Thus,noniseedscanbe

usedtoisolatecompoundswiththerapeuticpropertiesanda

high-addedvalue,leadingtogreatereconomicbenefitsforproducers

andanincreaseinthediversityofcompoundsderivedfromthis

species.

In contrast to their therapeutic actions, there are reports

of toxicity resulting from the consumption of noni

prod-ucts [15–18]. Secondary metabolites, such as anthraquinones,

have been suggested as the causative agents of toxicity.

1-Hydroxyanthraquinone,acomponentofnoniroots,wasshownto

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.01.029

becarcinogenicinmaleratsandproducedadenomas,

adenocarci-nomasandbenignstomachtumoursinasmallnumberofanimals

[19].

Inthisstudywereport,forthefirsttime,theisolationand

char-acterisationofathermostablelipidtransferprotein(McLTP1)from

noniseedsthatexhibitspotentantinociceptiveactivitywhenorally

administeredtomice.McLTP1isthefirstbioactiveproteinisolated

fromthenonispeciesinrelationtothetherapeuticpropertiesof

theplant.

Plantnon-specificLTPs(nsLTPs)formaproteinfamilyofsmall

cationicpeptides ubiquitously distributed throughout theplant

kingdom[20,21].Theybelongtotheantimicrobialpeptidesgroup,

whichhasbeenincreasinglyconsideredasa sourceofpotential

therapeuticagents,exhibitingpotentialapplicationsasanalgesics,

immunomodulatorsorinthetreatmentofneurologicaldisorders

[22–25].Todate,thisisthefirstreportofalipidtransferprotein

demonstratingantinociceptiveactivityinmice.

2. Materialsandmethods

2.1. Chemicals

SephadexG-50, Superose12HR 10/30and molecularweight

markers(LMW-SDSmarkerkit)werepurchasedfromGE

Health-careLifeSciences.AgilentEclipseXBD-C18columnwaspurchased

from Agilent Technologies. Reagents and solvents for

pro-tein sequencing, acetic acid, trichloroacetic acid, indomethacin,

naloxonehydrochloride,morphinesolution(1mg/mL),diazepam

solution (1mg/mL) and formaldehyde were purchased from

Sigma–AldrichCo.,St.Louis,MO. Otherchemicalsusedwereof

analyticalgradeandobtainedfromlocalsuppliers.

2.2. Noniseeds

Noni(M.citrifoliaL.var. citrifolia)seedswerecollectedfrom

plantscultivatedattheAntonioAlbertoFarm,Ceará(3◦16′40′′S,

39◦16′08′′W) and supplied by Embrapa Agroindústria Tropical

(Embrapa—CNPAT),Ceará,Brazil.Asamplespecimen(no.44.566)

hasbeendepositedinthePriscoBezerraHerbariumoftheFederal

UniversityofCearáforfuturereference.Theseedswereground

usingakitchenblenderandtheresultingflourthoroughlydefatted

withpetroleumether(1:10,w/v)andstoredat−20◦Cuntilused.

2.3. PurificationofMcLTP1

Proteinswereextractedfromthedefattednoniseedflour(15g)

using0.050MTris–HCl/0.25MNaCl,pH8.5(1:10w/v)at4◦C.The

suspensionwasstirredfor3handthenfilteredthrough

cheese-cloth.Theresiduewasre-extractedundertheaboveconditionsfor

2handthenfiltered.Thefiltrateswerecombined,centrifugedat

10,000×g,4◦C for30minandtheclearsupernatantdesignated

ascrudeextract(CE).TheCEwassubjectedtoacidtreatmentby

theadditionoftrichloroaceticacid(TCA)toa2.5%(w/v)final

con-centration.After30minonice,the2.5%TCAsolublefractionwas

clarifiedbycentrifugationat10,000×gfor30minat4◦Candthe

supernatantdialysed(cut offMW3000) against distilled water

at4◦Candlyophilised.Thelyophilisedproteinfractionwas

dis-solved(4mg)in0.050MTris–HCl/0.15MNaCl,pH8.5andapplied

onaSephadexG-50(1.5×40cm)columnpreviouslyequilibrated

withthe same buffer. Fractions (2mL) from the protein peaks

weremonitoredat280nmandcollectedataconstantflowrateof

30mL/h.Twoproteinpeakswererecoveredusingtheequilibrium

buffer. The fractions showing antinociceptive activity (McLTP1)

wereselected,concentratedandsubjectedtoanalytical

reversed-phasehigh-performanceliquidchromatography(RP-HPLC).

2.3.1. RP-HPLC

Pooledfractionsof proteinobtainedfromgelfiltrationwere

subjectedtoreversed-phasehigh-performanceliquid

chromatog-raphy using a C18 column (Agilent Eclipse XBD-C18 column

(250×4.6mm,5m)).Proteinsweredissolvedinultrapurewater

toobtainasolutionof0.5mg/mLandwerethenfilteredthrough

a 0.22mmembrane beforebeinginjectedinto theHPLC

(vol-umeinjected:20Loffilteredproteinsample).Thecolumnwas

equilibratedwith0.02%aqueousaceticacidandtheproteinswere

elutedataflowrateof1mL/minunderisocraticmode.Elutionwas

monitoredat216nmusingadiodearraydetector(AllianceHPLC

System,Waters,Corp.,Milford,MA).Thepeakelutingat7.9min

wasvacuum-dried,dissolvedinultrapurewater andappliedon

SDS-PAGE.

2.4. Proteinquantification

Proteinconcentrations were determinedby thedye-binding

methodofBradford[26],withbovineserumalbumin(BSA)asthe

standard.

2.5. Molecularmassdetermination

ThemolecularmassofMcLTP1wasdeterminedbydenaturating

SDS-PAGEon12.5%gelsundernon-reducingconditions,

follow-ingstandardprocedures[27].Proteinbandswerevisualisedwith

CoomassieBrilliantBlueR-250(Sigma–AldrichCo.,St.Louis,MO)

foratleast2handdestained(40%methanol,50%water,10%glacial

aceticacid)for30min.

ThenativemolecularmassofMcLTP1(1mg)wasdetermined

bygelfiltrationonaSuperose12HRcolumncoupledtoanFPLC

System(GEHealthcare)and equilibratedwith0.050MTris–HCl

buffer/0.25MNaCl, pH8.5.Chromatography wascarriedout at

aconstantflow rateof0.3mL/minand1mLfractionswere

col-lected. The column was previously calibrated with proteins of

known molecular masses (BSA, 66kDa; egg albumin, 45kDa;

chymotrypsinogen,25kDa;ribonuclease,13.7kDa,andaprotinin,

6.5kDa).

Mass spectrometry of McLTP1 (0.2mg/mL dissolved in

water/acetonitrile 1:1,v/v) was carried outon a Synapt HDMS

Acquity UPLCinstrument (Waters,Manchester, UK)by

electro-sprayionisationinpositiveionmode(ESI+)andaNanoLockSpray

source.The intact massspectra wereeffectively acquiredfrom

m/z1000to4000,whichallowedtoobtainmultiplychargedmass

ions.Themassspectrometerwasoperatedinthe“V”modewith

aresolvingpowerofatleast10,000m/z.Thedatacollectionwas

performedusingMassLynx4.1software(WatersCo.,Milford,MA,

USA)andchargedistributionspectrawerethendeconvolutedby

theMaximumEntropyTechnique(Max-Ent).

2.6. N-terminalaminoacidsequenceanalysis

The N-terminal amino acid sequence was analysed on a

Shimadzu PPSQ-23A Automated Protein Sequencer, performing

EdmandegradationofMcLTP1blottedonpolyvinylidenefluoride

membraneafterSDS-PAGE.Thesequenceobtainedwassubmitted

toautomaticalignmentusingtheNCBI-BLASTsearchsystem[28].

Theproteinsequencedatareportedinthispaperwillappearinthe

UniProtKnowledgebaseundertheaccessionnumberC0HJH5.

2.7. Invitrodigestionassay

Invitrodigestibility of McLTP1 wasdeterminedaccordingto

themethodofSathe[29],withmodifications.McLTP1(1mg/mL)

wassuspended in 200L of0.1MHCl, pH1.8, forpepsin (E.C.

0.1MTris–HCl,pH8.1fortrypsin(E.C.3.4.21.4;10,100BAEEU/mg

protein,frombovinepancreas)andkeptfor10minat37◦C.Next,

40Lofenzyme(1mg/mL)wasaddedtostarttheproteindigestion

andthereactionmixturewasincubatedinashakingwaterbathat

37◦Cfor4h.Aliquotsof25Lweretakenat0and4hand25L

of0.5MTris–HClbuffer,pH6.8,containing0.1%SDS,added.The

digestswereimmediatelyheatedinboilingwater(98◦C)for5min

andanalysedbySDS-PAGE[27].

Sequentialdigestionexperimentsusingpepsin,trypsinand

chy-motrypsin(E.C.3.4.21.1;40U/mgprotein,frombovinepancreas)

werecarriedoutusingMcLTP1 (1mg/mL)dissolvedin0.1MHCl,

pH1.8andincubatedinawaterbathat37◦Cfor5min.Analiquot

ofpepsin(enzyme:protein1:10,w/w)wasaddedandthemixture

incubatedat37◦Cfor4h.Thedigestionwasimmediatelystopped

byheatingthemixtureinaboilingwater(98◦C)bathfor5min.

Next,thepepsin-digested mixturewasmixed withtrypsinand

chymotrypsin(enzyme:protein1:10,w/w)in0.1MTris–HCl,pH

8.1,forfurtherdigestionfor5h.Thereactionwasstoppedandthe

sampleanalysedbySDS-PAGEasdescribedabove.BSA(2mg/mL)

wasusedasacontrolforthedigestionreaction.Allassayswere

performedintriplicate.

2.8. Animals

Experimentalprocedureswereconductedusinggroupsof2–3

montholdSwissmalemice(25–30g)obtainedfromBiotério

Cen-tralofFederalUniversityofCeará.Theanimalswerehousedunder

standard environmentalconditions (24±1◦C, humidity45–65%

and12hlight/darkcycle)andreceivedfoodandwateradlibitum.

Groupsof6–8micewereusedineachexperimentandhabituated

tothelaboratoryconditionsforatleast2hbeforetesting.Care,

han-dlingandexperimentalprocedureswereperformedinaccordance

withtheethicalstandardsestablishedbytheNationalGuidelines

fortheUseofExperimentalAnimalsofBrazilandbytheDirective

2010/63/EUoftheEuropeanParliamentandoftheCouncilofthe

EuropeanUnion.Theexperimentalprotocolswereapprovedbythe

CommitteefortheEthicalUseofAnimalsoftheFederalUniversity

ofCeará(CEUA-UFCno.37/13).

2.9. AntinociceptiveactivityofMcLTP1

2.9.1. Aceticacid-inducedwrithingmethod

Thistestwasperformedusingamodifiedversionofthemethod

described byKosteret al.[30].Animalsweretreated

intraperi-toneally(i.p.)withnoniseedcrudeextract(10,30or90mg/kg),2.5%

TCAsolublefraction(8mg/kg),McLTP1(1,2,4or8mg/kg),vehicle

(NaCl0.15M)orindomethacin(positivecontrol;10mg/kg)30min

beforetheinjectionofa1.0%aceticacidsolution(0.1mL/10gbody

weight,i.p.).Thenumber ofabdominal writhes(pelvicrotation

followed byfull extensionof both hind legs)wascumulatively

countedovera periodof20min,soon aftertheaceticacidwas

administered.ToevaluatewhetherMcLTP1displaysoral

antinoci-ceptive activity, it was given orally (8mg/kg body weight) to

animals30or60minpriortoanaceticacidinjection.The

antinoci-ceptiveeffectwasexpressedasapercentageoftheinhibitionof

abdominalwrithing.

2.9.1.1. Thermalstability determination. Toestablishthethermal

stabilityoftheprotein,McLTP1(1mg/mL)dissolvedinNaCl0.15M

wasincubatedinawaterbathat80◦Cfor30min.Aftercooling

thetreatedMcLTP1onicefor10min,miceweretreatedwiththis

protein(8mg/kg(i.p.)),30minbeforeaceticacidsolutioninjection,

andtheantinociceptiveactivitymeasuredasdescribedinSection

2.9.1.

2.9.2. Formalin-inducedpainassay

Themethodusedwassimilartothatpreviouslydescribedwith

somemodifications[31].Thirtyminutesaftertheadministrationof

McLTP1(8mg/kgp.o.ori.p.),NaCl0.15M(vehicle;negativecontrol;

p.o.ori.p.)ormorphine5mg/kgi.p.(positiveopioidcontrol),20L

of2.5%formalin(formaldehyde36.5%solution)inasalinesolution

wasinjectedintothesubplantaroftherighthindpawsofthemice.

Animalswereplacedindividuallyinatransparentcageandthetime

(inseconds)spentlickingandbitingtheinjectedpawwastakenas

anindicatorofthepainresponse.Thepainresponsewasmeasured

for5min(firstphase)and20–25min(secondphase)afterthe

for-malininjection,representingbothneurogenicandinflammatory

painresponsesrespectively.

2.9.2.1. Involvementofopioidreceptors. Toidentifywhether

opi-oidreceptorsareinvolvedintheantinociceptiveactionofMcLTP1

(8mg/kg;p.o.ori.p.),groupsofmicewerepretreatedwitha

non-selectiveopioidreceptor antagonist,naloxone(2mg/kg),30min

beforeadministrationofMcLTP1ormorphine(5mg/kg)andtested

usingtheformalintest.

2.10. EffectofMcLTP1onlocomotoractivity

TheeffectoftheMcLTP1(8mg/kg)onspontaneouslocomotor

activityandexploratorybehaviourwasassessedusingthe

open-field test, using the methodset out by Martin et al. [32]. The

apparatus(45cmwidth×45cmlength×15cmheight)consisted

ofawoodenfieldinwhichthefloorwasdividedinto36equalareas.

MiceweretreatedwithMcLTP1 orally60minbeforethe

exper-imentor withthevehicle(NaCl 0.15M) or diazepam(2mg/kg)

intraperitoneally30minbeforethe experiment. Thenumber of

areascrossedwithallpawsandthenumberofrearingresponses

werethenrecordedduringa5minperiod.

2.11. Statisticalanalysis

Intheresultsthemean±SEMarepresented.Statisticalanalysis

wasperformedusingone-wayanalysisofvariance(ANOVA)

fol-lowedbyTukey’sposthoctests,usingGraphpadPrism6.0software

(SanDiego,CA,USA).Differencesbetweengroupswereconsidered

significantatalevelofp<0.05.

3. Resultsanddiscussion

3.1. PurificationandcharacterisationofMcLTP1

M. citrifolia L. has become popular in recent years, as it is

believedtobeabletohelppreventlifestyle-relateddiseases[33].

Nevertheless,scientific evidence forthesebenefitsis limited to

studiesdemonstratingbiologicalactivitiesofsecondary

metabo-litesfromdifferentnoniparts,whilestudiesreportingtheisolation

andcharacterisationofbioactiveproteinsfromthisspecieshave

beenlacking.

Whenadministeredintraperitoneallytomiceat dosesof10,

30 and 90mg/kg, noni seedcrude extract significantly reduced

(p<0.05)thenoxiousstimulusinducedbyaceticacid,ina

dose-dependent manner, by 23.2–41.8% compared with the control

group(Table1).Theantinociceptiveactivityofthenoniseedextract

atalldosestestedwasnotalteredafterdialysis(cutoffMW3000),

suggestingthattheeffectobservedwasrelatedtoaproteic

compo-nent.Therefore,weembarkeduponaguidedfractionationofthe

noniseedextract,seekingthisantinociceptiveagentusinganacetic

acid-inducedwrithingtestinmice.

The antinociceptive activity was also detected in the 2.5%

TCA soluble fraction after administration at a doseof 8mg/kg

Table1

SummaryofpurificationprocedureofMcLTP1fromnoniseedsguidedbyanaceticacid-inducedwrithingtestinmice.

Purificationstep Protein(mg) Yielda(%) Doseb(mg/kg) %inhibitionc Specificbiologicalactivityd Purificationindexe Crude

extract

189.04

±3.23

100 10 23.25±0.03 – –

30 37.20±0.02* – –

90 41.86±0.19* 0.46 1

2.5%TCAsolublefraction 12.80±0.95 6.77 8 81.39±0.08** 10.17 22.10

SephadexG-50column(McLTP1) 11.58±0.87 6.12 8 96.13±0.08** 12.01 26.10

aYield=(totalproteinfromthefraction/totalproteinfromthecrudeextract)

×100%.

b Micewerepretreatedintraperitoneally30minbeforeanaceticacidinjection.

c Inhibitionofaceticacid-inducedabdominalconstrictioninmice.Theresultsshowthemean

±SD(n=8).

d Specificbiologicalactivityiscalculatedbydividing“%ofmaximuminhibitoryactivity/dose(mg/kg)”ofeachstepofpurification.

ePurificationindexiscalculatedastheratiobetweenthespecificbiologicalactivityobtainedateachpurificationstepandthatofthecrudeextracttakenas1.0. * p<0.05.

** p<0.01comparedtocontrolgrouppretreatedwithNaCl0.15Mi.p.(ANOVAfollowedbyTukey’stest).

Fig.1. PurificationofMcLTP1.(A)Separationprofileof2.5%TCAsolublefractionfromnoniseedextractonaSephadexG-50column.(B)RP-HPLCchromatography.Pooled

fractionsobtainedfromgelfiltrationwereappliedtoaC18reverse-phasecolumnandruninaWatersCorp.apparatus.Elutionofproteinswasmonitoredbymeasurement oftheabsorbanceat280(A)and216nm(B).InsertCoomassie-stainedSDS-PAGE(12.5%)containing(left–right)molecularweightmarkers(lane1;14.4–97kDa),proteins extractedfromnoniseeds(lane2)and(lane3)McLTP1.

toaSephadexG-50column.AsdepictedinFig.1A,twoprotein

peakswererecoveredusingtheequilibriumbuffer.Afterbeing

col-lected,concentratedanddialysedthetopmostpartofpeak2,which

exhibitedantinociceptiveactivityinmice,thisproteinfractionwas

submittedtoanalyticalRP-HPLCusingaC18column,resultingin

onewelldefinedpeakelutedat7.9minunderisocraticconditions

(Fig.1B).Thepurifiedproteinwasshownasasinglebandon

SDS-PAGE,withanapparentmolecularmassof15.13kDaandayieldof

Fig.2.ESI-MSanalysisofnativeMcLTP1.

Nativemolecularmassoftheisolatedproteinwasalsoassessed

bygelfiltrationchromatography.Thepurifiedproteinwas

chro-matographedona Superose 12HR, showinga single peak with

a molecular mass of 10.09kDa (data not presented), which is

in agreementwiththemolecularmasses obtainedbyESI mass

spectrometryundernativeconditions,whichshowedtwopeaks

correspondingtoMWof9450.30and9466.20(Fig.2).

Thefirst33aminoacidsoftheN-terminalsequenceofthe

puri-fiedproteinshowedsignificantsimilaritiestoknownlipidtransfer

proteins(LTPs)isolatedfromvariousplants,includingfourofthe

eightcysteineresiduesconservedinotherLTPs(Table2).LTPsare

small,water-soluble,basicproteins,classifiedintotwo

subfami-liesaccordingtotheirmolecularmasses:LTP1s(9kDa)andLTP2s

(7kDa)[34].ThemolecularmassdeterminedbytheESI-MSofthe

proteinisolatedinthisstudyallowedittobeclassifiedasamember

oftheLTP1subfamily(designatedasMcLTP1).

SincethediscoveryofplantLTPsinthe1970s,anincreasing

numberoflipidtransferproteinshavebeenisolated,particularly

fromseeds[35–37].However,untilnowtherehasbeenno

infor-mationregarding theirpresence inM.citrifolia L.seeds. Zottich

etal.[38]reportedtheisolationofaLTP1fromCoffeacanephora

(Cc-LTP1—Rubiaceae)seeds,with␣-amylaseinhibitorand

antimi-crobialproperties.McLTP1,whichwasalsoisolatedfromaplant

speciesbelongingtoRubiaceaefamily,showed57%identitywith

Cc-LTP1.

The presence of two peaks withm/z values of 9450.30 and

9466.20 suggests the existence of isoforms of McLTP1. Other

authors have reported that LTPs are found in severalisoforms

indistinct planttissues andorgans coded bya multigene

fam-ily, as demonstrated by Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa

[20,34,39,40].

AlthoughthemolecularmassofMcLTP1,determinedbyESI-MS,

isconsistentwiththoseobservedforotherLTP1s,themolecular

masscalculatedusingSDS-PAGEundernon-reducingconditions

wasestimatedtobe15.13kDa.AccordingtoGorjanovicetal.[41]

LTPscanformdimersinplanttissuesandalsoundernon-reducing

Fig.3.SDS-PAGE(12.5%)profileoftheinvitrodigestibilityofMcLTP1bypepsin

(laneP),trypsin(laneT)andaftersequentialdigestionwiththecitedenzymesand chymotrypsin(laneS).BSA(lanes1and2,left–right)wasusedasacontrol.Lane 3representsMcLTP1(20g).ProteinbandswerestainedwithCoomassieBrilliant

BlueR-250.

SDS-PAGE,asdemonstratedfortheLTP1isolatedfromHordeum

vulgarewhichshowedanapparentmolecularmassof16kDawhen

calculatedusingSDS-PAGE.

Duetotheircompactstructures,whicharestabilisedbyfour

disulfidebridges,LTPstendtobeextremelystableandresistantto

thermaldenaturationanddigestionbyproteases[42–45].Inthis

study,McLTP1wassubjectedtoasimulatedgastricandintestinal

Table2

AlignmentoftheN-terminalaminoacidsequenceofMcLTP1withothernsLTPsfromplants.ProteinsequenceswerealignedwiththeBLASTalgorithm.Conservedcystein

residuesthatformdissulfidebridgesinnsLTPsarehighlightedingray.

NsLTPsource Plantfamily Residueno. Sequence Residueno. %identity SequenceID

Morindacitrifolia Rubiaceae 1 AVPCGQVSSALSPCMSYLTGGGDDPEARCCAGV 33 100 C0HJH5

Triticumaestivum Poaceae 26 AVSCGQVSSALSPCISYARGNGANPSAACCSGV 58 70 ABF14722.1

Aegilopstauschii Poaceae 26 AISCGQVSSALSPCISYARGNGANPTAACCSGV 58 67 EMT04675.1

Vitisvinifera Vitaceae 25 AVTCGQVETSLAPCMPYLTGGG-NPAAPCCNGV 56 67 XP002282792.1

Vignaradiata Fabaceae 25 AITCGQVASSLAPCISYLQKGG-VPSASCCSGV 56 61 CAQ86909.1

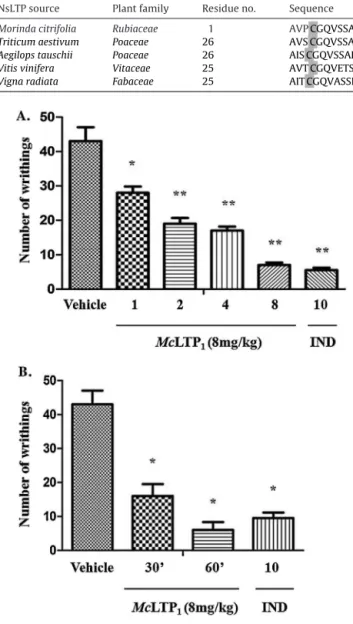

Fig.4. (A)EffectsofMcLTP1onaceticacid-inducedwrithingresponseinmice.

Vehi-cle(NaCl0.15M),McLTP1(1,2,4and8mg/kg),indomethacin(IND,10mg/kg)were

administeredi.p.30minbeforeanaceticacidinjection.(B)Antinociceptiveactivity ofMcLTP1(8mg/kg)afteroraladministrationinmice.Animalswerepretreated30

or60minbeforeanaceticacidinjection.Vehicle(NaCl0.15M)andindomethacin (IND,10mg/kg)wereorallyadministered30minbeforeanaceticacidinjection. Theresultsshowthemean±SD(n=8).Differencesbetweenthegroupswere deter-minedbyanANOVAfollowedbyTukey’stest,*p<0.05,**p<0.01whencompared tothecontrolgroup.

ofMcLTP1individuallydigestedwithpepsinandtrypsinandafter

sequentialdigestionwiththeaboveenzymesandchymotrypsin.

ThebandofMcLTP1 wasstableduringincubationwithpepsinor

trypsinfor4handwasalsodetectedevenafter9hofsequential

digestion.

3.2. AntinociceptiveactivityofMcLTP1

Whenadministeredtomiceintraperitoneally30minpriorto

acetic acid injection, McLTP1 (1, 2, 4, or 8mg/kg) significantly

reducedthenumberofabdominalconstrictionsobserved(p<0.05).

ThewrithingresponseinhibitionofMcLTP1wasdose-dependent

andatadoseof8mg/kgwascomparabletothatofindomethacin

10mg/kgi.p.(96.1%and98.3%inhibition ofabdominal

constric-tionreflexrespectively, Fig.4A).The antinociceptive activityof

Fig.5. EvaluationofthermalstabilityofthepurifiedMcLTP1usinganaceticacid

inducedwrithingresponseinmice.TheantinociceptiveeffectofMcLTP1(8mg/kg; i.p.)wasmeasuredafter0and30minpre-incubationat80◦C.Vehicle(NaCl0.15M)

andindomethacin(IND,10mg/kg)wereadministeredi.p.30minbeforeanacid aceticacidinjection.Theresultsshowthemean±SD(n=8).Differencesbetween thegroupsweredeterminedbyanANOVAfollowedbyTukey’stest,*p<0.05when comparedtothecontrolgroup.

McLTP1 was also observed after oral administration (p.o.)at a

doseof8mg/kg30(62.8%inhibition)or60min(86%inhibition)

priortotheaceticacidadministration.Theeffectobservedwhen

theprotein wasadministered60minprior toacetic acid

injec-tionwasnotsignificantlydifferentfromtheresponseobservedto

indomethacin10mg/kgp.o.(88%inhibition)(Fig.4B).Likeother

LTPs,suchasLJAMP2isolatedfromLeonurusjaponicusHoutt[46].

McLTP1displayedthermostability,retaining100%ofits

antinoci-ceptiveactivityafter1hincubationat80◦C(Fig.5).

Basedontheirinvitroactivities,numerousstudiesoverthelast

decadeshavelinkedplantLTPswitha myriadofbiological

pro-cesses,includingformationofthecuticlelayer[47],plantresponses

toabioticandbioticstresses[48–50]andasmodulatorsofplant

growthanddevelopment[51,52].However,thisisthefirstreport

ofalipidtransferproteinactingasamodulatorofthenociceptive

response.

Theacetic acid-inducedwrithingresponse isa sensitivetest

used for screening analgesic activity, regardless of the central

orperipheralcauses.Aceticacidisanirritantwhich causesthe

synthesis and release of pro-inflammatory mediators such as

prostaglandins(PGEandPGF2␣)andsympatheticnervoussystem

mediators that provoke pain nerve endings [53–55].

Intraperi-tonealororaltreatmentwithMcLTP1causedsignificantreduction

in the abdominal constriction produced by acetic acid,

indi-cating peripheral antinociception. Taissin-Moindrot et al. [56]

demonstratedthatplantLTPsareabletoaccommodatenotonly

phosholipids or fatty acids, but also a variety of hydrophobic

molecules,suchasPGB2,withoutmajorstructuralmodifications.

Thus, itcouldbeassumed that this proteininterfered withthe

blockade ortherelease of peripherallyacting endogenous

sub-stances,suchasprostaglandins,responsibleforpainfulsensations.

InordertofurtherclarifytheantinociceptiveeffectofMcLTP1,

Fig.6.Timespentonpawlickingafteroralorintraperitonealpretreatmentwith McLTP1(8mg/kg)onbothfirst(A)(0–5min)andsecond(B)(15–30min)phasesof theformalininducednociception.Dataareshownasthemean±SD(n=8). Differ-encesbetweenthegroupsweredeterminedbyanANOVAfollowedbyTukey’stest, *p<0.05vs.controlanimals.

(8mg/kg)administeredorallyorintraperitoneallycauseda

signifi-cant(p<0.05)inhibitoryeffectonbothphasesofformalininduced

pain,comparedtothecontrolcondition,withameanof51.1%(i.p.)

and32.7%(v.o.)intheearlyphaseand77.9%(i.p.)and65.1%(v.o.)

inthelatephase.Thepositivecontroldrug,morphine(5mg/kg),

significantlyattenuatedthepainresponsesofthetwophases.

Table3

EffectofMcLTP1onthetotalnumberofcrossedlinesandnumberofrearingsduring

5minofexposuretotheopen-fieldtest.Eachvaluerepresentsthemean±SEM

obtainedfrom8mice.StatisticaldifferencesweredeterminedbyANOVAfollowed byTukey’stest.

Groupa Dose(mg/kg) Crossedlines/5min Numberofrearings

Vehicle – 48.3±1.05 12.8±1.02

McLTP1 8mg/kg 39.2±2.32 12.3±1.56

Diazepam 2mg/kg 10.4±0.08** 2.01±0.04**

aMiceweretreatedwithMcLTP

1orally60minbeforetheexperiment.Vehicle

(NaCl0.15M)anddiazepam(2mg/kg)wereadministeredintraperitoneally30min beforetheexperiment.

**p<0.01(comparedwithsalinegroup).

Thefirstphaseoftheformalintest(0–5min)ischaracterised

by neurogenic pain caused by a direct stimulation of

nocicep-tors. Substance P and bradykinin are thoughtto participate in

thisphase[31].Thesecondphase(15–30min)ischaracterisedby

inflammatorypain,aprocessinwhichseveralinflammatory

medi-atorsarebelievedtobeinvolved,includinghistamine,serotonin,

prostaglandinsandbradykinin[31,57].Ingeneral,centrallyacting

drugsinhibitbothphasesequally,whileperipherallyactingdrugs

inhibitmainlythesecondphase[58].AsshowninFig.6,McLTP1

suppressedpainduringbothphases,indicatingthatthisprotein

hascentralandperipheralanalgesicproperties.

Pretreatment of animals with naloxone (2mg/kg), a

non-selective opioid receptor antagonist, partially reversed the

antinociceptiveactivityofMcLTP1,administeredorallyor

intraperi-toneally, suggestingthe involvementof theopioid routein the

observed activity. Opiates are generally believed to produce

antinociception exclusively via central mechanisms, but some

studiesindicatethat theymayalsoproduceantihyperalgesiain

peripheralsites.Thelater effectsaremediatedbyopioid

recep-torsonperipheralterminalsofsensoryneurons[59]and inthe

gastrointestinaltract[60].Thus,itispossiblethatMcLTP1bindsto

thesegastrointestinalsiteswhenadministeredorally,producing

theantinociceptiveeffect.Similarresultswerefoundforalectin

purifiedfromCanavaliabrasiliensisseeds[61].

Amajor concernin theevaluationof theanalgesicactionof

compoundsis whetherpharmacologicaltreatmentcausesother

behaviouralalterations,suchasimpairmentofmotorcoordination

or sedation, which might be misinterpretedas analgesic

activ-ity.Abehaviouralassessmentwascarriedouttodetermineifthe

antinociceptiveeffectsofMcLTP1werecausedbyanydisturbances

onthecentralnervoussystem.Locomotoractivitywasnotaffected

byMcLTP1,suggestingthattheantinociceptiveresponseobserved

washighlyselective(Table3).

4. Conclusion

In this study we purified, characterised and evaluated the

antinociceptive effect of McLTP1, a lipid transfer protein. It is

describedfor thefirst timeasapain modulator,amplifyingthe

rangeofbiologicalactivitiesdisplayedbythisgroupofmolecules

and alsoprovidingevidence ofitspotentialas asourceof new

painreliefdrugs.McLTP1demonstratedperipheralantinociceptive

activitythatwascomplementedbyitscentraleffect,dependenton

opioidergicinvolvement.Thisisalsothefirstreportoftheisolation

ofaproteinfromthenonispeciesassociatedwiththetherapeutic

propertiesoftheplant.

Conflictofinterest

Theauthorshavedeclaredthatthereisnoconflictofinterest,

includingfinancial,personaloranyotherrelationshipswithother

Acknowledgements

ThisworkwassupportedbyConselhoNacionalde

Desenvolvi-mentoCientíficoeTecnológico(CNPq)andFundac¸ãoCearensede

ApoioaoDesenvolvimentoCientíficoeTecnológico(FUNCAP).

References

[1]Y.Chan-Blanco,F.Vaillant,A.M.Perez,M.Reynes,J.M.Brillouet,P.Brat,The nonifruit(MorindacitrifoliaL.):areviewofagriculturalresearch:nutritional andtherapeuticproperties,J.FoodCompos.Anal.19(2006)645–654.

[2]A.R.Dixon,H.McMillen,N.L.Etkin,Fermentthis:thetransformationofNonia traditionalpolynesianmedicine(Morindacitrifolia,Rubiaceae),Econ.Bot.53 (1999)51–68.

[3]D.P.Sreekeesoon,M.F.Mahomoodally,Ethnopharmacologicalanalysisof medicinalplantsandanimalsusedinthetreatmentandmanagementofpain inMauritius,J.Ethnopharmacol.157(2014)181–200.

[4]R.AbouAssi,Y.Darwis,I.M.Abdulbaqi,A.A.Khan,L.Vuanghao,M.H.Laghari,

Morindacitrifolia(Noni):acomprehensivereviewonitsindustrialuses, pharmacologicalactivities,andclinicaltrials,Arab.J.Chem.(2015)(available online24.06.15).

[5]E.Dussossoy,P.Brat,E.Bony,F.Boudard,P.Poucheret,C.Mertz,J.Giaimis,A. Michel,Characterization:anti-oxidativeandanti-inflammatoryeffectsof CostaRicannonijuice(MorindacitrifoliaL.),J.Ethnopharmacol.133(2011) 108–115.

[6]S.Mahattanadul,W.Ridtitid,S.Nima,N.Phdoongsombut,P.Ratanasuwon,S. Kasiwong,EffectsofMorindacitrifoliaaqueousfruitextractanditsbiomarker scopoletinonrefluxesophagitisandgastriculcerinrats,J.Ethnopharmacol. 134(2011)243–250.

[7]S.Nima,S.Kasiwong,W.Ridtitid,N.Thaenmanee,S.Mahattanadul, GastrokineticactivityofMorindacitrifoliaaqueousfruitextractandits possiblemechanismofactioninhumanandratmodels,J.Ethnopharmacol. 142(2012)354–361.

[8]B.S.Siddiqui,F.A.Sattar,S.Begum,A.Dar,M.Nadeem,A.H.Gilani,S.R. Mandukhail,A.Ahmad,S.Tauseef,Anoteonanti-leishmanial,spasmolytic andspasmogenicantioxidantandantimicrobialactivitiesoffruits,leavesand

stemofMorindacitrifoliaLinn—animportantmedicinalandfoodsupplement

plant,Med.Aromat.Plants.3(2014),2167–0412.

[9]A.D.Pawlus,B.N.Su,W.J.Keller,A.D.Kinghorn,Ananthraquinonewithpotent quinonereductase-inducingactivityandotherconstituentsofthefruitsof

Morindacitrifolia(noni),J.Nat.Prod.68(2005)1720–1722.

[10]O.Potterat,M.Hamburger,Morindacitrifolia(Noni)fruit—phytochemistry pharmacologysafety,PlantaMed.73(2007)191–199.

[11]M.Wang,B.J.West,C.J.Jensen,D.Nowicki,C.Su,A.Palu,G.Anderson,Morinda citrifolia(Noni):aliteraturereviewandrecentadvancesinnoniresearch,Acta Pharmacol.Sin.23(2002)1127–1141.

[12]X.L.Yang,M.Y.Jiang,K.L.Hsieh,J.K.Liu,Chemicalconstituentsfromtheseeds ofMorindacitrifolia,Chin.J.Nat.Med.7(2009)119–122.

[13]S.Nelson,Noniseedhandlingandseedlingproduction.Fruitsandnuts-10. CooperativeExtensionService,CTAHR,UniversityofHawai’iatM¨anoa. [Internetdocument]<http://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/noni/downloads/FN10. pdf>,2005(accessed13.03.15).

[14]B.J.West,C.J.Jensen,A.K.Palu,S.Deng,Toxicityandantioxidanttestsof

Morindacitrifolia(noni)seedextract,Adv.J.FoodSci.Technol.3(2011) 303–307.

[15]M.E.Carr,J.Klotz,M.Bergeron,Coumadinresistanceandthevitamin supplementNoni,Am.J.Hematol.77(2004)103.

[16]N.F.Q.Marques,A.P.B.M.Marques,A.L.Iwano,M.Golin,R.R.De-Carvalho,F.J.R. Paumgartten,P.R.Dalsenter,DelayedossificationinWistarratsinducedby

MorindacitrifoliaL.exposureduringpregnancy,J.Ethnopharmacol.128 (2010)85–91.

[17]G.Millonig,S.Stadlmann,W.Vogel,Herbalhepatotoxicity:acutehepatitis causedbyanonipreparation(Morindacitrifolia),Eur.J.Gastroenterol. Hepatol.17(2005)445–447.

[18]V.Stadlbauer,P.Fickert,C.Lackner,J.Schmerlaib,P.Krisper,M.Trauner,R.E. Stauber,Hepatotoxicityofnonijuice:reportoftwocases,WorldJ. Gastroenterol.11(2005)4758–4760.

[19]H.Mori,N.Yoshimi,H.Iwata,Y.Mori,A.Hara,T.Tanaka,K.Kawai, Carcinogenicityofnaturallyoccurring1-hydroxyanthraquinoneinrats: inductionoflargebowel,liverandstomachneoplasms,Carcinogenesis11 (1990)799–802.

[20]A.deOliveiraCarvalho,V.M.Gomes,Roleofplantlipidtransferproteinsin plantcellphysiology—aconcisereview,Peptides28(2007)1144–1153.

[21]M.Morales,M.Á.López-Matas,R.Moya,J.Carnés,Cross-reactivityamong non-specificlipid-transferproteinsfromfoodandpollenallergenicsources, FoodChem.165(2014)397–402.

[22]A.Alba,C.Lopez-Abarrategui,A.J.Otero-Gonzalez,Hostdefensepeptides:an alternativeasantiinfectiveandimmunomodulatorytherapeutics, Biopolymers98(2012)251–267.

[23]E.S.Candido,M.H.S.Cardoso,D.A.Sousa,J.C.Viana,N.G.Oliveira-Júnior,V. Miranda,O.L.Franco,Theuseofversatileplantantimicrobialpeptidesin agribusinessandhumanhealth,Peptides55(2014)65–78.

[24]C.I.Schroeder,K.J.Nielsen,D.A.Adams,M.Loughnan,L.Thomas,P.F.Alewood, R.J.Lewis,D.J.Craik,EffectsofLys2toAla2substitutionsonthestructureand potencyofomega-conotoxinsMVIIAandCVID,Pept.Sci.98(2012)345–356.

[25]E.F.Schwartz,C.B.F.Mourão,K.G.Moreira,T.S.Camargos,M.R.Mortari, Arthropodvenoms:avastarsenalofinsecticidalneuropeptides,Biopolymers 98(2012)385–405.

[26]M.M.Bradford,Arapidandsensitivemethodforthequantitationof microgramquantitiesofproteinutilizingtheprincipleofprotein-dyebinding, Anal.Biochem.72(1976)248–254.

[27]U.K.Laemmli,Cleavageofstructuralproteinsduringtheassemblyofthe bacteriophageT4,Nature227(1970)680–685.

[28]S.F.Altschul,W.Gish,W.Miller,E.W.Myers,D.J.Lipman,Basiclocal alignmentsearchtool,J.Mol.Biol.215(1990)403–410.

[29]S.K.Sathe,Solubilization,electrophoreticcharacterizationandinvitro digestibilityofalmond(Prunusamygdalus)proteins,J.FoodBiochem.16 (1992)249–264.

[30]R.Koster,M.Anderson,J.DeBeer,Aceticacidforanalgesicscreening,Fed. Proc.18(1959)412–417.

[31]S.Hunskaar,K.Hole,Theformalintestinmice:dissociationbetween inflammatoryandnon-inflammatorypain,Pain30(1987)103–114.

[32]J.R.Martin,K.Baettig,J.Bircher,Mazepatrolling:open-fieldbehaviorand runwayactivityfollowingexperimentalportacavalanastomosisinrats, Physiol.Behav.25(1980)713–719.

[33]L.Lv,H.Chen,C.T.Ho,S.Sang,ChemicalcomponentsoftherootsofNoni (Morindacitrifolia)andtheircytotoxiceffects,Fitoterapia82(2011) 704–708.

[34]J.C.Kader,Lipid-transferproteinsinplants,Annu.Rev.PlantPhysiol.Plant Mol.Biol.47(1996)627–654.

[35]S.Tsuboi,T.Osafune,R.Tsugeki,M.Nishimura,M.Yamada,Nonspecificlipid transferproteinincastorbeancotyledoncells:subcellularlocalizationanda possibleroleinlipidmetabolism,J.Biochem.111(1992)500–508.

[36]A.Carvalho,C.E.Teodoro,M.Cunha,A.L.Okorokova-Fac¸anha,L.A.Okorokov, K.V.S.Fernandes,V.M.Gomes,Intracellularlocalizationofalipidtransfer proteininVignaunguiculataseeds,Physiol.Plant.122(2004)328–336.

[37]M.S.Diz,A.O.Carvalho,S.F.F.Ribeiro,M.Cunha,L.Beltramini,R.Rodrigues, V.V.Nascimento,O.L.T.Machado,V.M.Gomes,Characterisation: immunolocalisationandantifungalactivityofalipidtransferproteinfrom chilipepper(Capsicumannuum)seedswithnovel␣-amylaseinhibitory properties,Physiol.Plant.142(2011)233–246.

[38]U.Zottich,M.DaCunha,A.O.Carvalho,G.B.Dias,N.C.M.Silva,I.S.Santos,V.V. Nacimento,E.C.Miguel,O.L.T.Machado,V.M.Gomes,Purification: biochemicalcharacterizationandantifungalactivityofanewlipidtransfer protein(LTP)fromCoffeacanephoraseedswith␣-amylaseinhibitor properties,Biochim.Biophys.Acta1810(2011)375–383.

[39]V.Arondel,C.Vergnolle,C.Cantrel,J.C.Kader,Lipidtransferproteinsare encodedbyasmallmultigenefamilyinArabidopsisthaliana,PlantSci.157 (2000)1–12.

[40]F.Vignols,G.Lung,S.Pammi,D.Tremousaygue,F.Grellet,J.C.Kader,P. Puigdomenech,M.Delseny,Characterizationofaricegenecodingforalipid transferprotein,Gene142(1994)265–270.

[41]S.Gorjanovic,E.Spillner,M.V.Beljanski,R.Gorjanovic,M.Pavlovic,G. Gojgic-Cvijanovic,Maltingbarleygrainnon-specificlipid-transferprotein (ns-LTP):importanceforgrainprotection,J.Inst.Brew.111(2005)99–104.

[42]R.Asero,G.Mistrello,D.Roncarolo,S.DeVries,M.Gautier,C.Ciurana,E. Verbeek,T.Mohammadi,V.Knul-Brettlova,J.H.Akkerdaas,I.Bulder,R.C. Aalberse,R.vanRee,Lipidtransferprotein:apan-allergeninplant-derived foodsthatishighlyresistanttopepsindigestion,Int.Arch.AllergyImmunol. 122(2001)20–32.

[43]K.Lindorff-Larsen,J.R.Winther,Surprisinglyhighstabilityofbarleylipid transferproteinLTP1,towardsdenaturant,heatandproteases,FEBSLett.488 (2001)145–148.

[44]E.Pastorello,C.Pompei,V.Pravettoni,L.Farioli,A.Calamari,J.Scibilia,A.M. Robino,A.Conti,S.Iametti,D.Fortunato,S.Bonomi,C.Ortolani,Lipid-transfer proteinisthemajormaizeallergenmaintainingIgE-bindingactivityafter cookingat100◦C,asdemonstratedinanaphylacticpatientsandpatientswith

positivedouble-blind.Placebo-controlledfoodchallengeresults,J.Allergy Clin.Immunol.112(2003)775–783.

[45]S.Scheurer,I.Lauer,K.Foetisch,M.S.Moncin,M.Retzek,C.Hartz,E.Enrique,J. Lidholm,A.Cistero-Bahima,S.Vieths,StrongallergenicityofPruav3,thelipid transferproteinfromcherry,isrelatedtohighstabilityagainstthermal processinganddigestion,J.AllergyClin.Immunol.114(2004)900–907.

[46]X.Yang,J.Li,X.Li,R.She,Y.Pei,Isolationandcharacterizationofanovel thermostablenon-specificlipidtransferprotein-likeantimicrobialprotein frommotherwort(LeonurusjaponicusHoutt)seeds,Peptides27(2006) 3122–3128.

[47]P.Sterk,H.Booij,G.A.Scheleekens,A.VanKammen,S.C.DeVries,Cell-specific expressionofthecarrotEP2lipidtransferproteingene,PlantCell3(1991) 907–921.

[48]S.Torres-Schumann,J.A.Godoy,J.A.Pintor-Toro,Aprobablelipidtransfer proteingeneisinducedbyNaClinstemsoftomatoplants,PlantMol.Biol.18 (1992)749–757.

[49]F.García-Olmedo,A.Molina,A.Segura,M.Moreno,Thedefensiveroleof nonspecificlipid-transferproteinsinplants,TrendsMicrobiol.3(1995) 72–74.

differentdevelopmentalpatternsofexpression,PlantPhysiol.116(1998) 1461–1468.

[51]A.White,M.A.Dunn,K.Brown,M.A.Hughes,Comparativeanalysisof genomicsequenceandexpressionofalipidtransferproteingenefamilyin winterbarley,J.Exp.Bot.45(1994)1885–1892.

[52]R.Ghosh,V.A.Bankaitis,Phosphatidylinositoltransferproteins:negotiating theregulatoryinterfacebetweenlipidmetabolismandlipidsignalingin diversecellularprocesses,Biofactors37(2011)290–308.

[53]I.D.G.Duarte,M.Nakamura,S.H.Ferreira,Participationofthesympathetic systeminaceticacid-inducedwrithinginmice,Braz.J.Med.Biol.Res.21 (1987)341–343.

[54]V.Martinez,S.V.Coutinho,S.Thakur,J.S.Mogil,Y.Taché,E.A.Mayer, Differentialeffectsofchemicalandmechanicalcolonicirritationon behavioralpainresponsetointraperitonealaceticinmice,Pain81(1999) 179–186.

[55]Y.Ikeda,A.Ueno,H.Naraba,S.Oh-Ishi,InvolvementofvanilloidreceptorVR1 andprostanoidsintheaceticacid-inducedwrithingresponseofmice,LifeSci. 69(2001)2911–2919.

[56]S.Taissin-Moindrot,A.Caille,J.P.Douliez,D.Marion,F.Vovelle,Thewide bindingpropertiesofawheatnonspecificlipidtransferprotein,Eur.J. Biochem.267(2000)1117–1124.

[57]M.Shibata,T.Ohkubo,H.Takahashi,R.Inoki,Modifiedformalintest: characteristicbiphasicpainresponse,Pain38(1989)347–352.

[58]A.Tjolsen,K.Hole,Animalmodelsofanalgesia,in:M.J.Besson,A.Deckeson (Eds.),ThePharmacologyofPain,Springer-Verlag,Berlin,Germany,1997,pp. 1–20.

[59]A.Barber,R.Gottschilich,Opioidagonistsandantagonists:anevaluationof theirperipheralactionsininflammation,Med.Res.Rev.12(1992)525–562.

[60]O.Pol,J.R.Palacio,M.M.Puig,Theexpressionofdelta-andkappa-opioid receptorisenhancedduringintestinalinflammationinmice,J.Pharmacol. Exp.Ther.306(2003)455–462.