FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS

ESCOLA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO DE EMPRESAS DE SÃO PAULO

ARNALDO MAUERBERG JUNIOR

CABINET COMPOSITION AND ASSESSMENT OF A MULTIPARTY

PRESIDENTIAL SYSTEM

ARNALDO MAUERBERG JUNIOR

CABINET COMPOSITION AND ASSESSMENT OF A MULTIPARTY

PRESIDENTIAL SYSTEM

PhD dissertation presented to the Sao Paulo School of Business Administration of the Getulio Vargas Foundation as a requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Administration and Government.

Tese de Doutorado apresentada para a Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getulio Vargas como requisito para obtenção do título de Doutor em Administração Pública e Governo.

Linha de Pesquisa:

Política e Economia do Setor Público

Supervisor: Professor Ciro Biderman Co-Supervisor: Professor Carlos Pereira

International Host Professor: Ben Ross Schneider

Mauerberg, Arnaldo Jr.

Cabinet Composition and Assessment of a Multiparty Presidential System / Arnaldo Mauerberg Junior - 2016.

152 f.

Orientadores: Ciro Biderman, Carlos Pereira

Tese (CDAPG) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo.

1. Presidencialismo. 2. Partidos políticos. 3. Brasil - Ministérios e departamentos. 4. Governos de coalizão. 5. Governo comparado. I. Biderman, Ciro. II. Pereira, Carlos. III. Tese (CDAPG) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. IV. Título.

ARNALDO MAUERBERG JUNIOR

CABINET COMPOSITION AND ASSESSMENT OF A MULTIPARTY

PRESIDENTIAL SYSTEM

PhD dissertation presented to the Sao Paulo School of Business Administration of the Getulio Vargas Foundation as a requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Administration and Government.

Tese de Doutorado apresentada para a Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getulio Vargas como requisito para obtenção do título de Doutor em Administração Pública e Governo.

Linha de Pesquisa:

Política e Economia do Setor Público

Data da defesa: 22 de fevereiro de 2016

Banca Examinadora:

___________________________________________

Professor Ciro Biderman (Supervisor), FGV-EAESP

___________________________________________

Professor Carlos Pereira (Co-Supervisor), FGV-EBAPE

___________________________________________

Professor Marcus André Melo, UFPE-DCP

___________________________________________

Professor Octavio Amorim Neto, FGV-EBAPE

___________________________________________

Professor Cláudio Gonçalves Couto, FGV-EAESP

___________________________________________

Praise God, from Whom all blessings flow; Praise Him, all creatures here below; Praise Him above, ye heavenly host; Praise Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

Amen.

A Deus, supremo benfeitor, A Deus o Filho, a Deus o Pai,

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Firstly, I would like to thank Almighty God, the Father, the Son Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit for this magnificent life achievement. Without His endless blessings and support I would have never gone so far.

I also thank my beloved family: My father Arnaldo Mauerberg, my mother Edna Bertin Mauerberg, my sister Andreia Mauerberg, and my girlfriend Heloisa Morisue for their support, love, and patience, and for the trust they showed in my work.

I thank my advisors in Brazil, Professors Ciro Biderman and Carlos Pereira, for their guidance and instruction that enabled me to fulfill this work. Thanks are also due to Professor Ben Ross Schneider, my host professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for accepting and receiving me in such a kind way in 2014 when I had the honor of being a Guest PhD Candidate at the Political Science Department of MIT.

I also thank the members of my dissertation committee, Professors Marcus André Melo, Octávio Amorim Neto, Cláudio Couto, and Fernando Abrúcio, as well as all the other professors I was able to learn from.

I am also grateful to my friends Caio Costa, Celso Costa, Clauri Gonçalves, Juarez Gonçalves, Julia Guerreiro, and Renato Lima for all the discussions we had and the help they gave.

In addition, I am grateful to Rosabelli Coelho-Keyssar, Tereza Conselmo, Marta Andrade, Maria DiMauro, Diane Gallagher, and all the others on the staff of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the Getulio Vargas Foundation, the MIT-Brazil Center, and the Center for Politics and Public Economics.

AGRADECIMENTOS

Primeiramente agradeço ao Todo Poderoso Deus Pai, Filho e Espírito Santo por esta maravilhosa realização pessoal e profissional. Sem Suas bençãos sem fim eu certamente não chegaria tão longe.

Também agradeço a minha família: meu pai Arnaldo Mauerberg, minha mãe Edna Bertin Mauerberg, minha irmã Andreia Mauerberg e minha namorada Heloisa Morisue pelo suporte, amor e paciência e por tanto acreditarem em meu trabalho.

Agradeço aos meus orientadores brasileiros, Professores Ciro Biderman e Carlos Pereira pelo aconselhamento e instrução que tanto ajudaram na confecção desta pesquisa. Agradeço também ao Professor Ben Ross Schneider que me recebeu no Departamento de Ciência Política do Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) durante o ano de 2014 quando tive a honra de lá atuar como Estudante de Doutorado Convidado.

Agradeço também a todos os membros da banca de defesa desta tese, Professores Marcus André Melo, Octávio Amorim Neto, Cláudio Couto e Fernando Abrúcio pelas excelentes sugestões, assim como a todos os outros professores de quem pude aprender ao longo destes quatro anos de doutorado.

Agradeço aos meus amigos Caio costa, Celso Costa, Clauri Gonçalves, Juarez Gonçalvez, Julia Guerreiro e Renato Lima por todas as conversas e ajuda que me deram.

Adicionalmente agradeço a Rosabelli Coelho-Keyssar, Tereza Conselmo, Marta Andrade, Maria DiMauro, Diane Gallagher, e a todos os demais funcionários do Massachusetts Institute of Technology, da Fundação Getulio Vargas, do MIT-Brazil Center e do Centro de Política e Economia do Setor Público pela ajuda a mim oferecida.

ABSTRACT

This doctoral dissertation provides a detailed analysis of the Brazilian cabinet according to the concepts of a multiparty presidential system. Appointing politicians as ministers is one of the most important coalition-building tools and has been widely used by minority presidents. This dissertation will therefore analyze the high-level Brazilian national bureaucracy between 1995 and 2014. It argues that the ministries – or departments – are not equal, and that allied parties therefore take into account the different characteristics of a ministry when demanding positions as a patronage strategy or for use as other kinds of political assets. After reviewing the literature on the theme, followed by a comparative analysis of the Brazilian, Chilean, Mexican, and Guatemalan cabinets, all the Brazilian ministries will be weighed and ranked on a scale that is able to measure their political importance and attractiveness. This rank takes into account

variables such as the budgetary power, the ability to spend money according the ministers’ will, the ability to hire new employees, the ministries’ influence over other governmental agents such

as companies, agencies, and so on, the ministers’ tenure in office. Finally, a proxy is provided that seeks to identify the normative power a department may hold. All of these characteristics

will then be taken into account in considering the representatives’ opinion, thus helping to

ascertain whether the cabinet appointment has been coalescent among the several parties that

belong to the president’s coalition.

RESUMO

Esta tese de doutorado busca analisar os ministérios brasileiros de maneira detalhada e dentro do escopo do presidencialismo multipartidário. A concessão de cargos de ministros para partidos da base aliada é uma – senão a mais - importante ferramenta utilizada por presidentes minoritários para construir sua colizão de governo. Sendo assim, pretendemos analisar a burocracia do primeiro escalão do poder executivo federal no Brasil entre os anos de 1995 e 2014. Supomos que os ministérios não são iguais entre si, e que os partidos da base aliada levam em conta diferentes características que estes ministérios possuem na hora de realizar suas demandas por patronagem ou por demais tipos de ativos políticos que possam receber. Após uma revisão de literatura sobre o tema e uma análise comparada do gabinete brasileiro com os do Chile, do México e da Guatemala, os ministérios serão classificados em um ranking de importância política que levará em conta sua capacidade orçamentária, sua capacidade de gasto discricionário, seu quadro de funcionários, e, dentro deste último a habilidade que certo ministro têm para indicar afilhados políticos seus para posições dentro do governo, o poder de influência que este ministério possui sobre outros órgãos do governo como agências e empresas estatais, a duração total de tempo que um titular permanece em uma dada pasta e, por fim, o poder de normatizar certos setores econômicos. As características serão ponderadas levando-se em consideração a opinião de deputados federais chaves no processo político nacional e uma vez criado, o ranking nos auxiliará a avaliar se a distribuição de pastas têm sido proporcional para os diversos partidos integrantes da base aliada do governo.

FIGURES

Chart 1 – Average values for Brazil and Chile. 39

Chart 2 – Average values for Mexico and Guatemala. 44

Chart 3 Elite - What are the three most politically important ministries in Brazil? 87 Chart 4 Elite - What are the three least politically important ministries in Brazil? 89 Chart 5 Elite - Sort according to your preferences the characteristics that a ministry

in a presidential system has, with one being the most important, two the second most important, and so on until number six

represents the least important: 90

Chart 6 Elite - The total budget of a ministry is: 91

Chart 7 Elite - The share of unrestricted expenses of a ministry is: 91

Chart 8 Elite - A ministry's influence over other agencies and public companies is: 92

Chart 9 Elite - The total number of civil servants in a ministry is: 92

Chart 10 Elite - The share of civil servants hired directly by the minister as

cargo de confiança in a ministry is: 93

Chart 11 Elite - The normative power and its capacity to influence other economic

fields of activities for a ministry is: 93

Chart 12 Elite - The length of a minister’s tenure as chair of some ministry is: 94 Chart 13 Elite - The chance to be the link between his fellow party members

and the executive for a minister is: 94

Chart 14 Elite - Who should be mainly responsible for the executive coalition

building in multiparty presidential systems like Brazil? 140

Chart 15 Elite – Who is currently mainly responsible for the executive

coalition building in Brazil? 140

Chart 16 Elite - The current layout of the cabinet in Brazil regarding the

distribution of cabinet seats to allied parties is proportional. 141 Chart 17 Elite - The Brazilian president who best knew how to build and manage

his or her coalition was: 141

Chart 18 Elite - An ordinary congressman in a multiparty presidential system such as that of Brazil judges it is easier to influence public policy processes by being a member of the executive

Chart 19 Elite - A minister in a multiparty presidential system such as that of Brazil has more power to influence society than a

congressman, with the exception of the House Speaker. 143

Chart 20 Experts - Who should be mainly responsible for the executive

coalition building in multiparty presidential systems like Brazil? 144 Chart 21 Experts - Who is currently mainly responsible for the executive

coalition building in Brazil? 145

Chart 22 Experts - The current layout of the cabinet in Brazil regarding

the distribution of cabinet seats to allied parties is proportional. 145 Chart 23 Experts - The Brazilian president who best knew how to build

and manage his or her coalition was: 146

Chart 24 Experts - An ordinary congressman in a multiparty presidential system such as that of Brazil judges it is easier to influence

public policy processes by being a member of the executive body than by

being a member of the legislative body. 146

Chart 25 Experts - A minister in a multiparty presidential system such as that of Brazil has more power to influence society than a

congressman, with the exception of the House Speaker. 147

Chart 26 Experts - What are the three most politically important ministries in Brazil? 147 Chart 27 Experts - What are the three least politically important ministries in Brazil? 148 Chart 28 Experts - Sort according to your preferences the characteristics.

that a ministry in a presidential system has, with one being the most important, two the second most important, and so on until

number six represents the least important: 148

Chart 29 Experts - The total budget of a ministry is: 149

Chart 30 Experts - The share of unrestricted expenses of a ministry is: 149

Chart 31 Experts - A ministry's influence over other agencies and public companies is: 150

Chart 32 Experts - The total number of civil servants in a ministry is: 150

Chart 33 Experts - The share of civil servants hired directly by the minister as cargo de

confiança in a ministry is: 151

Chart 34 Experts - The normative power and its capacity to influence other

Chart 35 Experts - The length of a minister’s tenure as chair of some ministry is: 152 Chart 36 Experts - The chance to be the link between his fellow party members

TABLES

Table 1 – Basic features of selected countries. 37

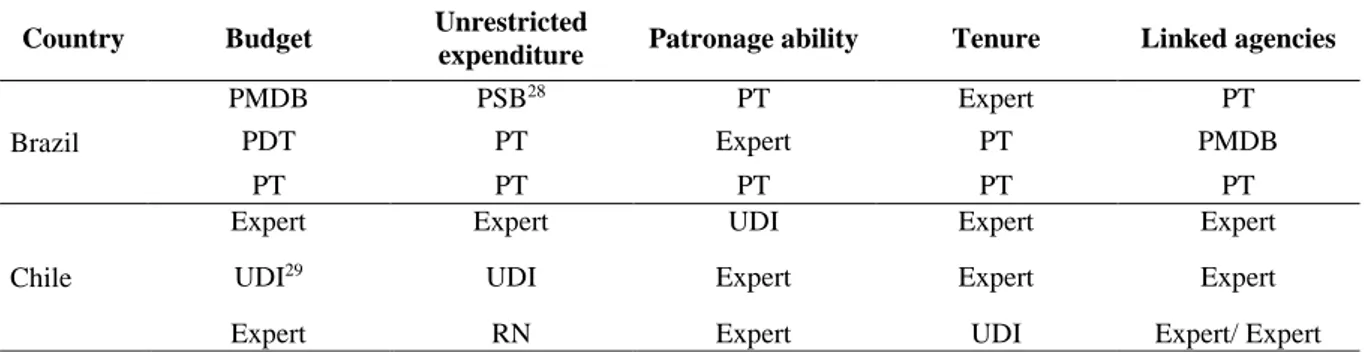

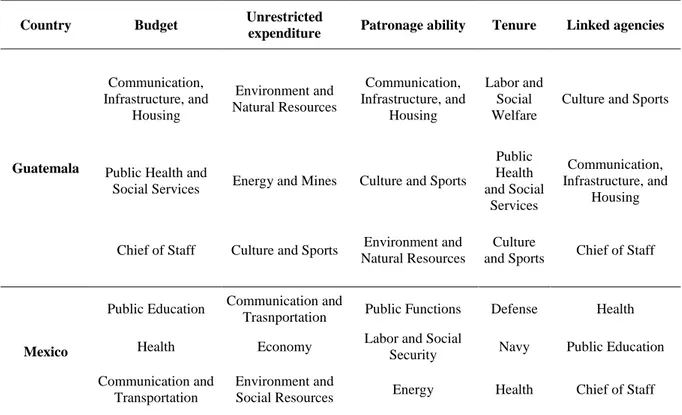

Table 2 – Ranking of departments according to the variables – Brazil and Chile. 41 Table 3 – Party affiliation of the heads of the top three ministries. 42 Table 4 - Ranking of departments according to the variables – Mexico and Guatemala. 46

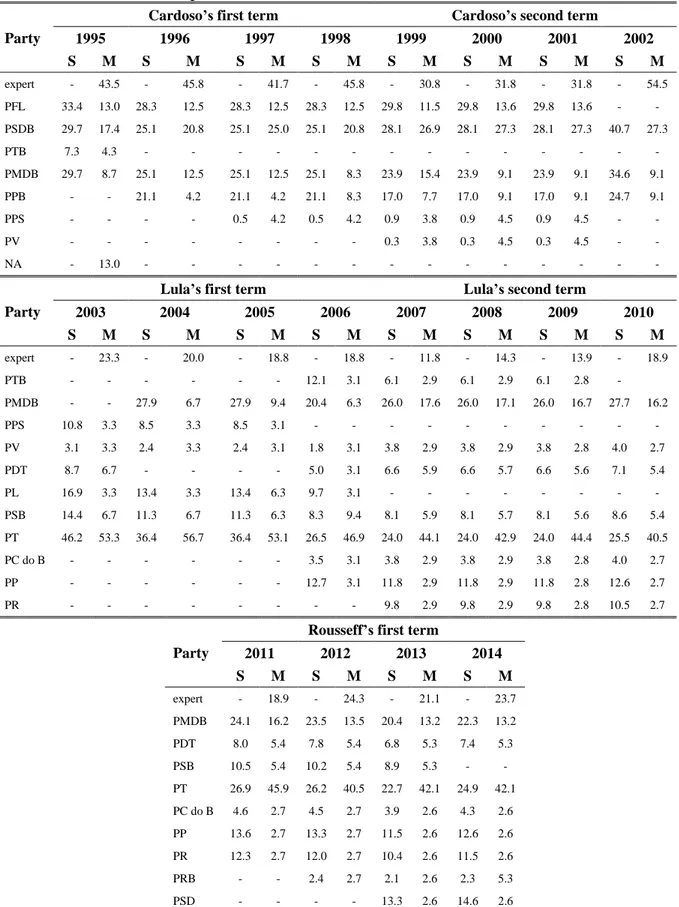

Table 5 – Cabinet composition year-by-year. 48

Table 6 - Cabinet party share – 1995 – 2014. 50

Table 7 – Cabinet inauguration, termination, and length. 51

Table 8 – Share of cabinet positions and House seats – 1995-2014. 53

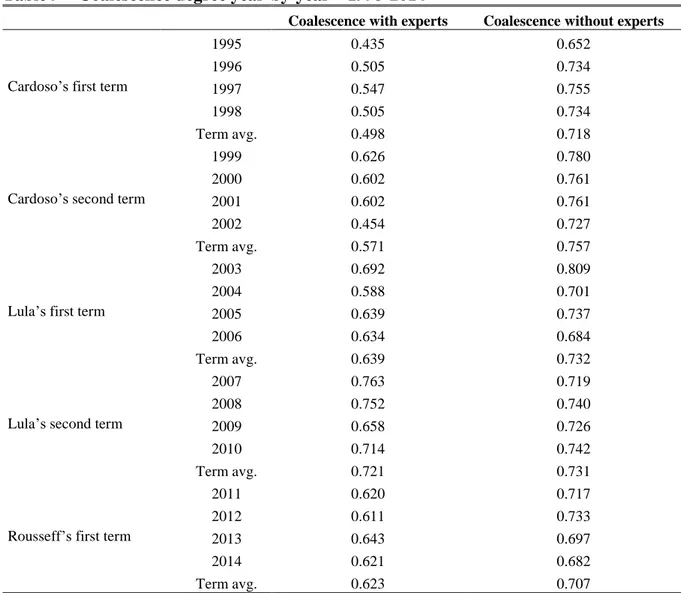

Table 9 – Coalescence degree year-by-year – 1995-2014. 54

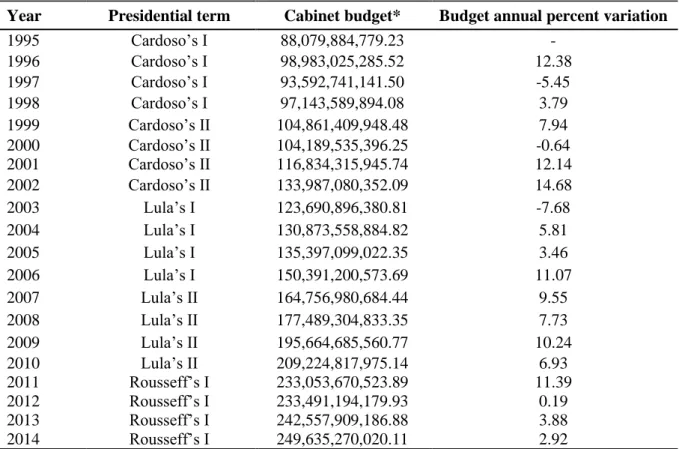

Table 10 – Annual evolution of budget size. 59

Table 11 –Departments’ rank according budget size. 61

Table 12 –Departments’ rank according unrestricted expenses. 64

Table 13 – Rank of ministries according to network capacity. 68

Table 14 – Annual cabinet evolution of number of civil servants. 71

Table 15 –Departments’ rank in terms of number of civil servants. 73

Table 16 - Ministries’ rank of patronage. 76

Table 17 – Departments holding normative power. 80

Table 18 – Rank of average tenure in months – 1995 – 2014. 83

Table 19 – Weighed departments – 1995 – 2014. 99

Table 20 –Correlation between representatives’ ranking and dissertation ranking. 104 Table 21 – Weighted and unweighted parties’ share of cabinet positions – 1995 – 2014. 106

Table 22 – Weighed and unweighted coalescence – 1996 – 2014. 109

Table 23 - Table 23 - List of Brazilian departments – 1995 – 2014. 123

ACRONYMS

DAS - Senior management and advice

IBGE - Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics IFE – Mexican Federal Electoral Institute

INE - Mexican National Electoral Institute INEGI - Chilean National Institute of Statistics MC – Member of Congress

MP – Medidas provisórias or provisional decree PAN - National Action Party

PC do B – Communist Party of Brazil PDT – Democratic Labor Party

PFL – Liberal Front Party PL – Liberal Party

PMDB – Brazilian Democratic Movement Party PP – Progressive Party

PPB – Brazilian Progressive Party PPS – Socialist Popular Party PR – Party of the Republic PRB – Brazilian Republican Party

PRD - Democratic Party of the Revolution PRI - Institutional Revolutionary Party PSB – Brazilian Socialist Party

PSD – Social Democratic Party

PSDB – Brazilian Social Democratic Party PT –Labors’ Party

PTB – Brazilian Labor Party PV – Green Party

RN - National Renewal Party

EQUATIONS

Equation 1 52

Equation 2 56

Equation 3 56

Equation 4 84

Equation 5 96

Equation 6 97

Equation 7 97

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION 16

1 REVIEWING THE LITERATURE ABOUT MULTIPARTY

PRESIDENTIAL SYSTEMS 18

1.1 Negative conclusions about multiparty presidential systems 19

1.2 Cabinet appointment as a tool of coalition building 22

1.3 Pork barreling and coalition fine tuning 25

1.4 Institutions and the executive-legislative game 27

1.5 Party leadership and its place in bargain 30

1.6 Federalism in a multiparty presidential system 32

2 A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF BRAZILIAN, CHILEAN, MEXICAN,

AND GUATEMALAN CABINETS 35

2.1 Multiparty Cabinets and Congresses: Brazil and Chile 37

2.2 One-party Cabinets and fragmented Congresses: Guatemala and Mexico 42

3 RANKING MINISTRIES AND CHECKING FOR COALESCENCE 47

3.1 Descriptive analysis and the evolution of the Brazilian Cabinet 47

3.2 Variables that influence political attractiveness 57

3.2.1 Budgetary capacity 57

3.2.2 Networking capacity 66

3.2.3 Patronage capacity 70

3.2.4 Regulation capacity 78

3.2.5 Time capacity 82

3.3 The elite survey 84

3.4 Score of political attractiveness 95

CONCLUSION 111

REFERENCES 113

APPENDIX A - List of Brazilian departments – 1995 - 2014 123

APPENDIX B – List of Brazilian ministers 1995 - 2014 125

APPENDIX C – Elite survey questions in Portuguese 133

APPENDIX D – Elite survey general questions 140

INTRODUCTION

Cabinet management is widely known to be one of the most common and powerful tools for minority presidents who are seeking reasonable levels of governability, and its practice has been seen in many Latin American presidencies since the early 1990s.

This dissertation is primarily concerned with this issue and seeks a better understanding of how

it applies for Brazil. Brazilian presidents have relied on this strategy since Cardoso’s first tenure

that was inaugurated on January 1st, 1995, which is when this research begins. Much has been said about the way in which Brazilian presidents build and manage their coalitions, and especially about how Cardoso achieved a more proportional distribution of cabinet seats among allied parties in comparison to Lula and Rousseff. In this, he succeeded in making day-by-day political negotiations easier, especially if compared with Mrs. Rousseff tenure

One concern, however, is that the features of federal bureaucracy have sometimes not been taken into account when the distribution of Cabinet positions has been studied. Usually the instrument analyzed was the number of seats held by each coalitional party inside the cabinet,

together with its percentage of House seats within the whole coalition. This dissertation’s

contribution to this literature is the assumption that that the ministries (or federal departments) are not equal. Because of such differences, the level of proportionality between the House seats and cabinet positions of a coalitional party may differ from the level proposed by the standard coalescence degree.

The main objectives of this PhD dissertation are threefold: i) To carry out a thoroughgoing analysis of the Brazilian federal bureaucracy structure in order to discover the main differences among all the ministries from 1995 until 2014, ii) to establish a rank of political importance for

all Brazilian federal departments, discovering which are the “best” ones and which are the “worst” ones, and, iii) considering the rank results to refine the coalescence degree checking if the proportionality among legislative and Cabinet shares for coalitional parties changes or not.

consider the system’s success and stability. They are mainly based on cabinet management,

pork barrel resources distribution, and the presence of a stable institutional framework. Of all these branches, the most important one for this dissertation is the one that deals with cabinet management.

Chapter Two presents a comparative analysis that comprises the cabinets of Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Guatemala. This is conducted in order to identify and present some of the differences in cabinet composition in multiparty presidencies (the former two) and one-party presidencies (the latter two).

Chapter Three moves the primary objective of this research project, namely, the analysis of the Brazilian case. This chapter seeks to answer the following questions: What are the most important ministries in Brazil? And, what is the real distribution of political assets inside the Brazilian cabinet? It first presents the annual evolution of the cabinet and then the coalescence degree measured by the difference between the House seats a coalitional party has and the number of cabinet positions it is granted by the president. By refining this measure, a score is created that enables one to properly assess the weight each ministry has within the cabinet, as well as how this affects the proportionality regarding House seats and cabinet share.

In order to build this rank of ministries’ political attractiveness, information was acquired concerning the variables that are considered important for any politician who is given the option of picking a department. These include budgetary resources, normative resources, network resources, time resources, and patronage resources. An elite survey was then conducted with House stalwarts in order to discover the scale of importance of those variables to them. Their opinion, together with a statistically balanced approach, made it possible to finally give a weight to each ministry in each year. These weights enabled a final calculation of the proportionality degree, enabling one to check whether the consideration of all these variables affects the

perceived adequate proportionality of Cardoso’s administration and the lack of adequate

1 REVIEWING THE LITERATURE ABOUT MULTIPARTY PRESIDENTIAL

SYSTEMS

Since the late 1980s, many authors have published studies about Brazil and its political system. The 1988 Constitution created a presidential system with a highly fractionalized Congress. In this scenario, it is mandatory for the president to create a Congress coalition that can help him with his agenda. This dissertation deals mainly with cabinet issues under the domain of a multiparty presidential system. However, it is important to review the literature that deals with

all the features of such a system in order to discover the cabinet’s importance for the topic and

also to provide the reader with a full guide to studies on the subject. The relevance of the theme means that its full bibliography is huge, which makes it impossible to analyze all of the papers concerned with multiparty presidential systems. It was therefore decided to select almost all of the works of the main authors who have worked in this area. In addition, some important papers were analyzed for the specific contribution of authors who do not primarily work with this theme.

Some papers sought to indicate the general characteristics of the system. Among these, Mainwaring (1990) can be noted for his comparison of the old institutionalism in Latin American politics with the fresh contributions of presidentialism and democratic stability. His work proposes a research agenda that focuses on the period when the executive power became stronger and affected political parties in Latin America.

The aim of this chapter is to provide a synthesis of this literature, presenting a different approach from that observed in the previously-cited articles.1 The chapter starts by analyzing the studies that were part of a first wave of publication. These emphasized the features of the system that

would have prevented it’s endurance over an extended period of time. Because the predictions

of these studies were not observed, other papers began to be published in order to explain how a system with such characteristics was surviving with a reasonable level of stability. In order to discuss this, the chapter is divided into the following sections: Section 1.1 will show studies that made negative predictions concerning the future of the system, while Section 1.2 will present the main features of coalition building in presidential systems. This will be followed by an analysis of the tools used to keep the coalition working, which will in turn be followed by a discussion of the importance of institutional design, rather than the role played by the party leadership in executive-legislative relations in Brazil. Finally, the influence of federalism on Brazilian coalitional presidentialism will be considered.2

1.1 Negative conclusions about multiparty presidential systems

Much has been said since 1988 about the institutional design created by the new Constitution. This includes discussion of the existence of a presidential system with plurality elections, a legislative branch elected according to open list proportional representation, federalism, the ease with which new political parties can be created, an executive that is totally independent from the legislature, and a presidential fixed term. If one follows a timeline, one can see a first wave of studies that focused on the debate of presidential systems versus parliamentary ones. Based on a supranational view, it was argued that all the above-mentioned factors would lead to the failure of the brand new Brazilian democracy. These forecasts were at their worst when researches defended the superiority of parliamentary systems over presidential systems. In the discussion below, the main studies that lead to such conclusions are presented.

Some years before the creation of the 1988 Constitution, Linz (1973) had presented arguments against presidential systems. For him, in contrast to parliamentary systems, in presidential systems the winner of the election takes all, or the party that wins the executive elections receives all the benefits of the job and does not have to share these benefits with any other party.

1This dissertation’s focus is not far from that of Power (2010a), except it presents more branches of research on

the theme.

Moreover, the impact of the president’s personality (being elected only by the citizens) would

make him less dependent on the help of partisan leadership. In a situation in which a party held the presidency without holding the majority of seats in Congress, the system would inevitably face some problems. Linz (1990) has presented additional arguments in favor of parliamentary systems, arguing that presidential systems contain a paradox. They create at a person with huge political power – the president – but also institutions that are responsible for removing these

powers from him, such as auditing courts. Another problem in Linz’s view is internal conflict

experienced by the president. He sees the president both acting as a politician within a party and being the executive chief of a nation as mutually exclusive options. In addition, a fixed term is an impediment to quick solutions in times of crisis, such as a case of corruption involving the president, for it is more difficult to implement impeachment processes for a president than to dissolve a parliamentary cabinet.

The first text that focuses only on a specifically Brazilian case came from Abranches. His 1988 work compared the Brazilian situation historically with consolidated democracies around the world and concluded that the main difference between Brazil and the other countries studied was related to their systems of government. At that time, there was no other consolidated example of a system with proportional representation, multiple political parties and presidentialism. This meant that Brazil was one of the few countries that organized its executive power with coalitions. In such a scenario, the president must choose whether to be a hostage to the many commitments that come with a large coalition, or whether to keep fine-tuning his own

party in a small coalition. The main problem of this kind of system in Abranche’s view lies in the fact that the stability of the whole system is fully dependent on a government’s current

performance.

Papers from late 1980s and early 1990s claim that the congressmen of center-right wing parties tend towards regional voting, that the deputies of left wing parties are more compliant with their leadership, and that the catch-all parties have undisciplined delegations. These assertions were based on the incentives to selfish behavior in the Brazilian electoral system, such as open-list proportional representation, the incumbent with guaranteed rights being able to run for re-election,3 the possibility of a larger number of candidates than contested seats, and the

possibility for a Member of Congress (MC) to change from one party to another without adverse consequences (there were 197 such changes from 1987 to 1990, and 262 cases from 1991 to 1995).4 All these incentives created weaknesses in the party system, leading to the growth of the catch-all parties and resulting in subsequent legislative disciplinary problems (Mainwaring, 1991 & 1997; Mainwaring & Pérez-Liñán, 1997).

In their historical analysis of many democracies, Stepan and Skach (1993) argue that the correlation between democratic consolidation and type of regime is stronger in parliamentary systems than in presidentialism. The most susceptible point of presidential systems lies in the fact that the executive cannot be removed even when it is without legislative support, while in parliamentary systems it can be. In the case of a crisis involving these powers, the democratic systems of presidential systems would be. In contrast to Abranches (1988), and without exploring their hypothesis in further depth, Stepan and Skach (1993) reckoned hypothesis that presidential systems do not create incentives for coalition formation.

Open list proportional representation is once more claimed to cause the weakness of political parties and of the legislative power. Assuming that the president and party leaders are weak,5 the legislative control and the subsequent stability of the system are dependent on considerable factors. These include, among others, the profile of the voting deputies (those with greater dominance tend to give greater support to the executive); the political experience of the president when building his Cabinet (which José Sarney had and Fernando Collor did not have); and the electoral strength of certain politicians who can judge themselves self-sufficient and are not party dependent. A consideration of these factors from this perspective does not leave one optimistic about the political system (Ames 2002a & 2002b).

According to Negretto (2006), the lion’s share of analyzed presidential systems were composed by minority governments. Governmental crisis (not regime crisis) tends to occur in countries in which a party, which does not hold the presidency, controls the median legislator and also has veto power. The executive-legislative battle can be expected to become fiercer when a president with simple majority in Congress is succeeded by a coalition government, and reaches its peak when a minority government gets into office.

4 Opportunity extinguished by the Supreme Electoral Court in 2007.

A less negative finding is the presumption of more accountability and identifiability created by a proportional legislature and a plural executive. Presidents with no absolute power can also be seen as beneficial for the system. However, representatives will have little incentive to follow party directives and will rather seek to further their personal reputation with the electorate if there is minimal control of list access by the party leadership, there is a nominal vote rather than a party vote, and if there is a high proportion of candidates in relation to the district magnitude. All of these factors can be found in Brazil, which means that seeking personal reputation weakens the bargaining process between the legislative parties and the executive (Shugart & Carey, 1992; Carey & Shugart, 1995; Shugart & Mainwaring, 1997).

Shugart and Maiwaring (1997) discuss both the positive and negative features of the system. On the positive side, they point to the great power granted to the constituency, the freedom of Congress in legislative matters, and the mandate stability instead of Cabinet instability. On the negative side, they point to the fixed terms that tend to create minority governments, which, without the option of legislative dissolution, are unable to deal with crisis. In addition, there is the possibility of a rookie being elected simply because of his smooth talk and/or good looks.

As has been seen, many authors expected that some features would lead to the failure of the presidential system. However, this has not been observed over the course of time in Brazil. The following section will consider why the above theories appear to be incorrect.

1.2 Cabinet appointment as a tool of coalition building

is inaugurated, when there is a change in party composition, or when more than 50 percent of the ministers are switched (Amorim Neto 1994).

Research into cabinet building in Europe (Amorim Neto & Strom, 2006; Amorim Neto & Samuels, 2010) indicates that the proportion of independent ministers inside a cabinet is a positive function of electoral volatility, semi-presidential systems, minority governments, and the legislative powers of the president.6 It is also negatively related to Congress fragmentation. Figueiredo et al. (2010) claim that in many countries in Latin America, including Brazil, 67 percent of presidents without an electoral majority have built government coalitions7 by means of cabinet offers. Arretche and Rodden (2004) argued that their high transaction costs would make legislative coalitions impossible. Therefore, government coalitions are preferred in which the ministers act as bridges between the Federal Executive and the House of Representatives, thus decreasing theses transactional costs. For Raile et al. (2011), cabinet is a means of coalition building, while resources for pork barrel are considered coalitional term fine-tuning in order for the executive to get its agenda approved. They also claim that the bigger the share of a presidential party inside the House, and the bigger the president’s popularity, the smaller the number of departments shared with other parties. Finally, presidents choose cabinet appointments when they find their other available tools too costly, and forming a cabinet can also help them to implement their policy agenda. The stability of such a cabinet will then be

negatively related to the president’s power, to minority governments, and to a low presidential

approval score (Martinez-Gallardo, 2011a & 2011b).

Concerning Brazil, analysis comparing the 1946-1964 period with the post-1985 years concluded that different factors are responsible for different kinds of cabinets. Party indiscipline and legislative fragmentation tend to create coalitional cabinets (those based on party criteria), while a president with strong legislative powers creates cooption cabinets (ministers with party ties but who do not act as party agents within the cabinet). In both periods, the greater the job offering, the greater the legislative discipline. It can also be seen that a high number of representatives and senators were appointed as minister, with the largest number coming from

6These are considered valuable results, but Shin (2013) assumes that cabinets should be treated differently in a

parliamentary systems compared to a presidential one.

7 Coalition governments are dependent on the supply of executive positions in order for allied parties to receive

the South and Southeast regions8 (Amorim Neto, 1994; Amorim Neto & Santos, 2001; Amorim Neto et al., 2003; Figueiredo, 2007).

Since the cabinet has been built, one can analyze the cabinet according to various criteria. One criteria is related to proportionality, i.e., the ratio between departments offered to a particular party and its share within the coalition, which is called coalescence degree.9 This measure allows one to observe whether a party with few seats is receiving more departments than it is supposed to, or whether a party with many seats is receiving fewer departments than it should. Coalescence and legislative submission can be empirically shown to have a positive relationship. However, a negative correlation can also be shown by the number of decrees10 issued by the president. Moreover, it is supposed that weak executive-legislative relations are a by-product of a low degree of coalescence that is stimulated by a higher number of decrees issued by the executive (Amorim Neto, 2000 & 2002; Amorim Neto & Tafner, 2002; Amorim Neto et al., 2003).

However, this measure raises the question of whether all departments are equal, particularly when their budgets are considered. Departments are clearly different, and some are more valuable to one kind of party, while others are preferred by other kinds of parties. Their differences relate to their normative power, budgetary capacity, their share of unrestricted expenditure of the budget, patronage efficiency, and the time accumulated by a particular party as head of a department. These variables mean that each party may pay particular attention to a particular department, and prefer one to another. Figueiredo (2007) says that, in addition to other characteristics, the cooption strategy must be taken into account. An initial study that included some sources of differences in departments was carried out by Meneguello (1998) when she classified them as belonging to the economic, political or social fields. In that study, which compared the presidencies of José Sarney, Fernando Collor de Mello, Itamar Franco, and Fernando Henrique Cardoso, only Fernando Collor de Mello had a nonpartisan cabinet. The main objective of this research is to create an index that is able to consider all these

8 In other countries, such as Belgium, the main criteria for the distribution of ministries is geographical.

9 = − ∑𝑛 |𝑆 − 𝑀 |

= , where: 𝑀 is the percentage of departments received by party i when the cabinet was appointed and 𝑆 is the percentage of seats held by party i in the total number of seats in the House controlled by the allied parties.

10 In Portuguese they are called medidas provisórias (MP) and must be countersigned by the Congress at some

characteristics and re-calculate the levels of proportionality among House seats and cabinet positions for a coalitional party.

Finally, the cabinet is a powerful weapon for restricting public spending. Amorim Neto and Borsani (2004) found that cabinet stability creates an increase in public spending and a decrease in government savings in order to pay public loans. They also discovered that right wing cabinets are more fiscally responsible.

After this explanation of the characteristics cabinets as a governability tool, the next section will explore the literature that analyzed how the executive undertakes coalition fine-tuning during the term.

1.3 Pork barreling and coalition fine tuning

Another resource that the president has that was also not considered among the negative considerations of multiparty presidential systems, is the money in the federal budget that is given to MCs for pork barreling. A considerable number of studies on this topic provide research that focused primarily on econometric analysis, and showed the process of budget amendment from its proposition until its execution as a vital component of executive-legislative relations. In such a process, representatives can amend the annual budget that the president sends to Congress in order to gain its approval for the following year. This effectively means that MCs can request some of the money of the annual budget for pork barreling. The executive can authorize the amount requested, or it can refuse to do so. Moreover, if it is authorized, it does not necessarily need to free it up. In addition, the president can authorize the money expecting the support from House members in return in time0, releasing or not the amount of authorized money in time1. This means that he has bargaining power over this process between

time0 and time1; first by authorizing the money, and second by effectively giving it to the representatives for pork barreling.

because the biggest part of it is targeted at collective and institutional use.11 Despite this last claim this dissertation nevertheless seeks to present ideas about the topic as a control mechanism over allied parties who are also able to influence House electoral outcomes.

Budget amendments can be interpreted as a political instrument capable of influencing deputies’ electoral ambitions. When Ames (1995a) tried to explain the spatial patterns of the 1990 Brazilian House election, he found that in 1989 and 1990 candidates had sought safe strongholds in vulnerable cities, thus solving in some ways their electoral weaknesses by offering pork. Mayoral candidates who had previous experience in their early years as representatives allocated more pork resources to the city in which they later ran for mayor. Moreover, those who sought a higher-level job (such as senator or governor) but who had also been representatives in their early years, allocated more money for their states compared to deputies who did not run for those jobs. However, incumbents seeking re-election seem to have had a similar performance in implementing their budget amendments than those who were running for higher jobs (Samuels, 2002; Leoni et al., 2003). Both national and local characteristics influenced the likelihood of winning seats for the House in 1998, but pork had a more positive effect on the results than purely legislative activities such as the proposition of bills and so on. Even when MCs performed national activities, they were driven by the ambition of more resources for pork (Pereira & Rennó, 2002 and 2003; Pereira & Mueller, 2003).

The studies discussed in what follows consider pork as a coalition maintenance instrument. The previous paragraphs provided evidence that this is a highly valued good for Congressional representatives. Given this, the president uses it as a currency in dealing with his Congress coalition. He also uses the approval or execution of budget amendments to gain ad hoc support from outside of his coalition representatives (i.e. from those who belong to opposition parties).

An analysis to determine representatives’ support for both Congress’ bills and for executive ones indicates that dominant-concentrated elected deputies give more support to presidential bills than to their own. The same trend can also be observed among congressmen with large amounts of money received from budget amendments (Ames, 1995b; Pereira & Mueller, 2002).

11A question that arises and is not presented by the authors deals with the transmission mechanism of these

Pereira and Mueller (2004) have pointed out that money for pork is a very low-cost coalition maintenance tool. They have also argued that budget amendments provide a link between individual electoral incentives and the centralized internal rules of Congress. The number of individual budget amendments executed in 1998 was a direct consequence of the same instrument having also a positive relationship with, and support of, the executive in 1997. Individual and collective amendments cannot be considered as substitute goods as the former have a positive relation with the approval of executive bills in the House, while the latter have an inverse relationship with the success of executive propositions on the floor (Alston & Mueller, 2005; Pereira & Orellana, 2009).

Refining the thought about the mechanisms used by the executive in order to gain support, Raile et al. (2011), as already cited, have argued that jobs in the federal bureaucracy are used in order to build the coalition, while budget amendments are used as a maintenance tool that also serves to aggregate some representatives from opposition parties in a few cases. This last feature was observed in the 2003 Pension Reform, when members of the government coalition who already had jobs in departments observed the execution of many amendments proposed by colleagues belonging to opposition parties. Nevertheless, observations from 1997 to 2005 indicate that the larger the government coalition, the less the amendments freed up money to outside or opposition parties. The approval and execution of amendments to the opposition are obviously not the rule, but they can sometimes be used as a powerful tool.

1.4 Institutions and the executive-legislative game

This section is intended to show the main contributions of an institutionalist approach. This perspective allows many characteristics to emerge, including studies that view institutions as a kind of government, those that focus on electoral issues, those that prioritize the legislative powers of the president, and others.12 In almost all cases, these institutional executive powers and strengths were not considered in the first wave of studies on the theme.

12 The focus relies on formal institutions, but one cannot neglect the role played by informal institutions. This

The first studies to be considered are those on constitutionalism, especially those dealing with the organization and functioning of republican powers. According to Melo (1998), national constitutions reduce transactional costs when they stipulate the role played by each party in electoral and governmental processes. When politicians tie their own hands for future actions, this could be interpreted as them making a forecast in order to avoid their own future irrational behavior. In a documented analysis, Cheibub et al. (2011) argued that the number of Latin American constitutions that allow for parliamentary dissolution is very small. This also grants

more power (proposition and urgency request for their bills) to the lion’s share of executives in

this region than is awarded to executives in other geographical regions. However, this strength does not occur at the expense of congressional power in all cases and the authors stated that Latin American legislatures have greater power to keep tabs on their executives in comparison to other continents.

The 1988 Brazilian Constitution gave the president huge legislative powers, such as partial veto power, decree power, urgency requests in his bills and the right to develop the annual budget. Nevertheless, strong presidents have not been considered dangerous to presidential democracies (Cheibub & Limongi, 2010). In contrast to this view, another perspective argues that there is an inverse relation between policy stability and the legislative powers of the president. In this case, Brazil is an exception because of the possibility that its judiciary has to constrain the president. Other institutions, such as the media and Congress, are able to check the executive are more frequently seen in countries with higher governance scores. In addition, there are also independent institutions that have arisen that act as a counterweight to the superpowers of the executive. These include public prosecutors (Ministério Público), courts of accounts, etc. They are all referred to by the literature as checks and balances institutions.13 (Melo 2009, Melo et al. 2009, Pereira et al. 2011).

Concerning government or regime institutions (both parliamentary and presidential), Przeworski et al. (1996), using data from 135 nations from 1950 to 1990, concluded that parliamentary systems tend to last longer. In their review of the literature on the topic, Cheibub and Limongi (2002) found that cooperation incentives are greater in parliamentary systems, but that the probability of coalition formation is equal in both systems when any party has more

13 Another interesting point is that partisan fragmentation is seen as beneficial, while increasing transaction costs

than one third of the seats in the legislative. Cheibub et al. (2004) also showed that parliamentary systems have more coalitions than presidential ones, but that coalitions are far unusual in the latter.

With regard to electoral rules, their permissiveness and the heterogeneity of the Brazilian population have been leading to high rates of party fragmentation. Multiparty systems have a statistically significant relationship to the rise of minority parties. Notwithstanding this

fragmentation couldn’t avoid political stability among the five biggest Brazilian political parties (the Workers’ Party – PT; the Brazilian Social Democrat Party – PSDB; the Liberal Front Party

– PFL,14 the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party – PMDB, and the Progressive Party – PP) (Amorim Neto and Cox 1997, Cheibub 2002, Santos 2008). For Colomer (2005), the best electoral rules are proportional representation for legislative elections and two round pluralism for executive positions. This would keep parties closer to the median voter, unified governments would not exist and the president would be elected with broad support that included the median voter.

Two of the president’s legislative powers must be highlighted. The first is his power of partial

and full veto against Congressional bills and the second is his agenda power. Santos (1997), comparing the period of 1946-1964 to the post-1988 years, found that some presidential powers have been reduced. In the first period only two thirds of the Congress was needed to pull down a presidential veto, while today only an absolute majority is needed.

A documentary analysis shows that Colombia, Chile, Argentina, Peru, and Equator have presidents who are able to initiate legislation. One can interpret the provisional decrees (or

Medida Provisória, the 62nd article of 1988 Brazilian Constitution) as a delegation of powers from the legislative to the executive. The extent to which MCs benefit from such a delegation

will vary according their capacities to control the executive’s activities. In the 1980s, one of the aims of the National Constituent Assembly was to make the legislature more agile therefore the provisional decree had sought to implement modernization and administrative action (Figueiredo & Limongi, 1997). This hypothesis was tested by Pereira et al. (2005a) who

assessed to what extent delegation theory15 and unilateral action16 were observed in Brazil from 1988 to 1998. They showed that there was not a unique situation; unilateral action fits well in the whole period, but delegation theory was only observed during Cardoso’s first tenure, thanks to the Real Plan.17

According Figueiredo and Limongi’s (1995), after 1988 the Brazilian federal executive

proposed 88 percent of all the federal laws in the country. Presidents who are supported by coalitions can be expected to rule less drastically, and to propose constitutional amendments and complementary laws rather than using provisional decrees, which would a large part of Congressional responsibility for the approval of legislation (Amorim Neto et al., 2003). The constant reissuing of provisional decrees can fit into a situation in which every new reissue creates new bargaining scenarios between Congressional representatives and the executive.

Armijo et al. (2006) called this theory a “recurrent bargain”, and argued that neither the propensity to political chaos, nor governance created by sacrificing representatives, mayors, and governors in favor of the executive, can be applied to Brazil. Instead, they saw all the governments from Sarney the first tenure of Lula as based on this cooperative system in which a strong president gains support through the participation of other political agents.

Finally, Pereira et al. (2005b) raised this question within the context of the Brazilian federal government. Their study appears to indicate that a larger or smaller number of provisional decrees does not affect presidential approval.

1.5 Party leadership and its place in bargain

Party leadership plays an important role in executive-legislative relations. The greatest amount of research uses an econometric approach to dealing with the problems posed. During a voting procedure on the floor in Brazil, a party leader can give the following instructions to his delegation: Vote positively, contrary or put the party in obstruction (taking away his delegation denying the minimum number of representatives required to vote the bill); decontrol the delegation, allowing it to vote as it wants or; not take any position (the last two situations are

15 Increasing the number of provisional decrees in situations of high presidential popularity.

16 Increasing the number of provisional decrees during periods of low indexes of presidential approval and less

support of Congress for his bills.

17 An economic stabilization plan carried out by Cardoso while Finance Minister during the Franco Presidency.

rare). Between 1988 and 1998 party delegations were seen as very disciplined, following their leaders and enabling easy forecasts about their future behavior on roll calls. However, this view of discipline delegates overlooks the first wave of theories that had expected the Brazilian system to collapse at any time. The key point here is that the party leader acts as a link between the congressmen and the executive, which is why such levels of discipline can be observed (Limongi & Figueiredo, 1995; Figueiredo & Limongi, 1999).

With regard to this link position, the Brazilian system gives wide powers to the political parties within Congress. The role played by the leadership is important. While there is no difference between representatives regarding voting rights and other common matters, differences do exist regarding the distribution of pork resources18 and nominations for important positions inside the House. The leadership is in charge of these distributions, so it is to be expected that a rational MC will follow his leader, thus making possible his future demands. At the same time, it is not common for a leader to act as an autocrat with his delegation because he is elected by his party colleagues who may rebel and elect a new leader. We can therefore expect cooperation between the delegation and the leadership (Limongi & Figueiredo, 1998).

A representative’s bargaining power against the federal executive is very little when he acts

alone, which is one of the reasons why we do not observe isolated negotiations between a

president’s emissaries and individual deputies. In order to get what they want, Congressional

representatives need to cluster in a political party with clear representatives who conduct the bargaining process with the executive on their behalf. This role is played by the party leader. Therefore, the assumption of a president who is very independent of the legislative and of a

blind opposition that is able to undermine a government’s desires does not make sense. The executive needs to have its agenda approved and not all parties will be able to compete in future elections as an opposition. This makes it more enticing for them to join the government coalition rather than to disconnect from it (Limongi & Figueiredo, 1998, 2002; Figueiredo & Limongi 2000; Pereira & Mueller, 2003).

One can therefore see that a healthy delegation-leadership relationship would be useless if the leadership-executive relationship did not follow the same pattern. Given the emergence of a new fact, one can argue that an analysis of the interactions the present party-leadership and the

President Rousseff’s negotiators may be interesting. According to a famous Brazilian

newspaper, Folha de São Paulo (2013), President Rousseff’s coalition is the least disciplined since 1989, and coalition members are protesting that they do not receive any attention from

the executive. Another problem arises when one looks at the president’s team in charge of the

political relations with Congress, who have often been judged as unskilled for the job. The studies covered in this review were based on analysis of presidents with good political skills (Sarney, Cardoso, and Lula). Other presidents, such as Collor and Franco, did not have the same level of political ability, but neither of them experienced such a low level of party discipline

during their terms. What can be the cause of this phenomenon? Is it due to Rousseff’s

centralizing and authoritarian style, her low profile and the awkward political team charged with bargaining with Congress, or is it due to the overall fall of the political popularity indexes in Brazil?

The committee of leaders (called colégio de líderes) usually acts on the executive’s behalf when the latter asks for urgency in some bill. This is allowed by the 64th article of the Brazilian

Constitution, which seeks to avoid the interference by minority groups seeking to overthrow

some presidential proposition. Usually the executive’s agenda is more easily approved than that of the legislative (Figueiredo & Limongi, 1995).

Another important feature of leadership, according Figueiredo et al. (1999), is related to their ability to appoint and remove colleagues from committees at any point. Pereira and Mueller (2000) discussed this question and concluded that, thanks to the urgency request, the Brazilian committee system is totally dominated by the executive. If it were not for the urgency request

committees would be able to gain access to and reveal House members’ preferences, thus decreasing the uncertainty that might arise during floor voting procedures. However, urgency requests are made because of the high waiting cost created by the assessment of the bill in all Congressional bodies.

1.6 Federalism in a multiparty presidential system

The second stream argues the opposite, namely, that issues of individual states are more important to the representatives than the partisan and federal ones.

The first stream has sought to assess the power exercised by state governors over national party cohesion, questioning what party leaders do as governors compete against each other. In this

case, the delegations would tend to take the party leaders’ side. Carey and Reinhardt (2003) argued that the governors’ actions were not statistically significant to party cohesion in the Brazilian House of Representatives between 1986 and 1991. Arretche and Rodden (2004) also sought evidence of state power on the federal level and concluded that the fact of a governing party belonging to the federal party coalition is not significant for voluntary financial transfers from the national executive, but that over-representation and a higher turnout tends to favor the states. Cheibub et al. (2009) also claim that belonging to a state in which the governor is opposed to the national executive does not influence the likelihood of a congressman voting in accordance with the recommendations of the national government. The outcome remains the same when controlling for exclusive voting interests of states, when members of the governing coalition keep following the direction of the national government and their leaders.

By contrast, the other wave of studies analyzing the same question has reached conclusions standing up for governors and states strength and for the weakness of national party leaders. These conclusions are influenced by: i) The state power of partisan leadership that defines whose name will be on the party list in the next election and whose will not, and also determines the destination of campaign money among the candidates; ii) the electoral power created by a governor being personally side by side with some House candidate in a neighborhood or town during the campaign; iii) the office resources held by a governor;19 iv) the ambition of some politician to gain a higher position in the state bureaucracy in future; and v) the weakness of party leaders.20 According to this view, candidates don’t have campaign funds, the power to advertise on television, nor the power to appoint their friends to positions within the federal bureaucracy. Studies have shown that a House candidate can gain more electoral profit by attaching his image to that of the governor candidate than to that of the presidential candidate. Statistics have also shown that candidates for state offices (senator, governor and

19 An example of the control over office resources by governors can be seen in Melo et al. (2010) where the authors

performed a detailed study about how a governor determines the degree of autonomy of state regulatory agencies based on their expectations of keeping their power.

governor) who had been representatives in the past had amended the budget in favor of their home states. Moreover, an analysis found that all of the MCs affiliated to PSDB, PMDB, Brazilian Progressive Party21– PPB, and Democratic Labor Party – PDT had a greater tendency to follow the state governor rather than the party leader22 (Samuels, 2000, 2002; Desposato,

2004). In the same way Abrúcio (1998) argues for the governors’ strength over and against

others primarily because the House elections used to obey a state logic rather than a national one, and also because MCs are encouraged to perform according to selfish behavior rather than partisan behavior.

Finally, the unusual power that the 1988 Constitution gave to all Brazilian municipalities must be emphasized. Since then, they have formed an independent federal unity, just like the states. Many contracts have been signed directly between the federal executive and the local level executives. One example is the public health system, in which a mayor decides whether his city will join a program or not. If so, he must inform the federal executive of this, without any interference of the state governor. One may assume that the strengthening of the mayors may

have occurred due to the decay of the governors’ power. However, no studies were found that

investigated this together with the relations between the executive and legislative powers at the national level.

This chapter has provided evidence that there are many branches of study regarding multiparty presidential systems, and that many papers and books have been published about Brazil. One important characteristic that has been noted is that almost all of them considered only one variable while analyzing these interactions. It is important to note that a new approach to the theme has begun to emerge, as can be seen in Pereira and Melo (2012) and Chaisty et al. (2014), whose work proposes an analysis that deals with more than one variable or characteristic at the same time. These authors see the stability of a government as derived from the legislative powers of the president, the existence of trading currencies for bargaining (such as money for pork and patronage resources), and from strong institutions of checks and balances (an active judiciary, a legislative watchdog, an independent media, courts of account, etc.). All of these

are to be considered simultaneously, and forma kind of a “tool box” that is available to the

president.

21 Current Progressive Party.

22 Even with such a claim, we note that the coefficients used to determine this level of state and local cohesion of

2 A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF BRAZILIAN, CHILEAN, MEXICAN, AND

GUATEMALAN CABINETS

As can be seen in the previous chapter, much has been said about the kind of political systems chosen by Latin American countries during their last wave of democratization. The choice for a presidential systems is evident and the importance of cabinet building and management has been clarified. This chapter undertakes a comparative analysis of four Latin American cabinets: the Brazilian, the Chilean, the Mexican, and the Guatemalan.

Chasquetti (2001) argues that in many cases in Latin America,23 the creation of government

coalitions are mandatory and that one way of gaining political support is through cabinet management (Cox & Morgenstern, 2001). That is why, according Figueiredo et al. (2012), between 1979 and 2011 three percent of Latin American cabinets were supermajority unitary cabinets, seven percent were majority unitary cabinets, eight percent were majority coalitions, 17 percent were minority unitary ones, 30 percent were minority coalitions, and 36 percent were supermajority coalitions. Foweraker (1998) states that in countries where the executive power was able to create a majority coalition within Congress (such as Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay) higher levels of governability were observed than in those countries where it could not do so (such as Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela). Altman and Castiglioni (2008) declare that the more inclusive a cabinet is in Latin America, the greater the chances are of structural change being carried out. Finally, the proportion of ministers with some kind of party

affiliation in Latin America can be seen as influenced by the size of the president’s party, his

decree powers, and his term limit (Amorim Neto, 2006).

The question therefore arises of whether coalitional parties are indifferent among all the ministries (or departments) within the cabinet? And the deeper question is whether the parties are even interested in holding cabinet positions, or whether they prefer to receive political assets other than cabinet positions? Countries with fragmented congresses and minority presidents do not always have multiparty cabinets. In such cases, one can assume that the president chooses another governability tool other than cabinet management. Alternatively, in the case of a fragmented Congress or one-party cabinet, it may not be advantageous for allied parties be part of the cabinet as the departments are not politically attractive enough.

Assuming that parties are interested in resources in order to keep their power and influence, and to gain a good share of votes in upcoming elections, cabinets with features that can help them to achieve these goals will be more attractive to them than cabinets without such features. These are cabinets with higher levels of budgetary capacity, unrestricted expenses, the ability to hire civil servants and retain influence over those already hired, the number of companies, agencies, and others directly linked to the minister; and the tenure as the chairman of some ministry would all increase the power and the future electoral outcomes of a party holding the control of a department, making more interesting to hold a position inside the cabinet, finally leading it to be a multiparty instead of a one-party kind.

The intention of this chapter is to present a broad descriptive analysis of four examples of Latin American countries during 2011. This is done in order to introduce the reader to the subject and to the propositions that are made here, which will be analyzed more deeply in the following chapter when only the Brazilian case for the past 20 years will be considered.

These countries were chosen because they all had minority presidents and fragmented Congresses, but two (Brazil and Chile) had multiparty cabinets, while the other two (Guatemala and Mexico) had one-party cabinets.24 If one supposes that the first two rely on cabinet management as a governability tool, one will be able to show whether their cabinets differ at some level from the latter two, which should make them more interesting to allied parties compared to the ones from Guatemala and Mexico. Some of the basic features of these four countries can be seen in the following table:

24Another important variable that led to the choice of these four countries is that of data availability for all of