Abstract

Objective: To analyze trends in childhood leukemia mortality in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, between 1980 and 2006.

Method: Gender-stratiied leukemia mortality data for children aged < 15 years from 1980 to 2006 were retrieved from the Brazilian Mortality Information System for the state of Rio de Janeiro. Data were stratiied by place of death (city of Rio de Janeiro proper, the state capital; Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region, excluding the capital; and rest of the state). Leukemia deaths were deined according to death certiicate ICD-9 and ICD-10 coding (for deaths occurring in 1980-1995 and 1996-2006, respectively). Leukemia mortality rates were calculated by age and calendar year and age-adjusted to a standard world population. Polynomial linear regression with a 5% signiicance level was used to evaluate mortality trends in the study regions.

Results: The three studied regions revealed similar trends, with a continuous downward pattern; the most substantial decline was detected in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro (city proper). In all studied areas, leukemia mortality was highest among males.

Conclusions: A downward trend in childhood leukemia mortality was detected throughout the state of Rio de Janeiro. The most pronounced reduction occurred in the state capital.

J Pediatr (Rio J). 2010;86(5):405-410: Leukemia, child, mortality, Brazil.

ORiginAl ARtiCle

Copyright © 2010 by Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria405 introduction

The leukemias are a heterogeneous group of hematological malignancies characterized by clonal

proliferation of immature hematopoietic cells with aberrant differentiation.1 They are the most common malignant

neoplasms of childhood, and account for approximately 33% of all malignancies in children and adolescents under the age of 14 years worldwide.2

The incidence of childhood leukemia has been on the rise in several developed nations, such as the United States,3 England,4 and various European countries.5 This

increase is partially explained by improvements in cancer registry systems and greater population-wide access to the healthcare system, which allows early diagnosis of malignancies. Reduced incidence rates have been reported in

trends in childhood leukemia mortality

over a 25-year period

Arnaldo Cézar Couto,1 Jeniffer Dantas Ferreira,1 Rosalina Jorge Koifman,2 gina torres Rego Monteiro,2 Maria do Socorro Pombo-de-Oliveira,3 Sérgio Koifman4

1. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Saúde Pública e Meio Ambiente, Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública Sérgio Arouca (ENSP), Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

2. Doutorado, Departamento de Epidemiologia, ENSP, Fiocruz, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. 3. Pós-doutorado, Centro de Pesquisas, Instituto Nacional do Câncer, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. 4. Pós-doutorado, Departamento de Epidemiologia ENSP, Fiocruz, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

Study conducted atEscola Nacional de Saúde Publica Sérgio Arouca (ENSP), Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

No conflicts of interest declared concerning the publication of this article.

Suggested citation: Couto AC, Ferreira JD, Koifman RJ, Monteiro GT, Pombo-de-Oliveira MS, Koifman S. Trends in childhood leukemia mortality over a 25-year period.J Pediatr (Rio J). 2010;86(5):405-410.

developing countries,6 although leukemia rates in the city of

São Paulo are similar to those found in developed countries.7 In Goiânia, Goiás, childhood mortality rates declined between

1978 and 1996, signiicantly so for children aged 5 years or younger, as did leukemia mortality in patients under the age of 15 from 1979 to 1995.8

In developed countries, leukemia mortality rates in

children under the age of 15 have declined signiicantly since

the 1970s.9 This decrease is likely due to earlier diagnosis, standardization of treatment protocols, and subsequent improvement in the survival of children with leukemia.10

The demographic and epidemiologic transition observed

over the past 20 years in several countries, as well as the

magnitude of the incidence and prevalence of childhood

leukemia, have attracted the interest of various researchers

and been the subject of extensive epidemiological studies.

In Brazil, however, childhood cancer statistics have not been analyzed in much depth in the literature, even

though data are available, such as those collected in the

Mortality Information System (Sistema de Informação sobre Mortalidade, SIM) maintained by the Brazilian Ministry of Health (Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde – DATASUS, 1998)11.

The present study sought to analyze mortality trends

in childhood leukemia in the state of Rio de Janeiro from 1980 to 2006.

Methods

This was a descriptive, time-series study based on

mortality data for boys and girls under the age of 15 living

in the state of Rio de Janeiro between the years 1980 and 2006.

Data on childhood leukemia deaths were obtained directly

from SIM, a public-domain, free and open-access Uniied Health System database organized and maintained by the

Brazilian Ministry of (DATASUS/MS).11,12 Mortality data were

analyzed for the following geographic areas in the state

of Rio de Janeiro: city of Rio de Janeiro proper (the state

capital); Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region (excepting the

state capital); and remainder of the state of Rio de Janeiro

(total in-state deaths after exclusion of those recorded in the Metropolitan Region).

Leukemia deaths were deined as those with a proximate cause containing ICD-9 codes 202.4, 203.1, or 204-208 (for the 1980-1995 period) or ICD-10 codes C90.1 and C91-C95 (for the 1996-2006) period.

The period of analysis ranged from 1980 to 2006 and was subdivided into nine three-year periods. This strategy was adopted in an attempt to reduce the inluence of random annual luctuations in data.

First, childhood leukemia mortality rates were calculated

for each region. Rates were age-standardized to the world

population proposed by Segi13 and modiied by Doll14 with

respect to the age range of interest (< 15 years). Scatter plots of mortality rates per calendar year were generated

to provide a visual representation of rate distribution over time.

For model construction, age-standardized childhood

leukemia mortality rates were analyzed as the dependent

variable (y), and years of death (stratiied into three-year periods), as an independent variable (x). Trend analysis was performed using linear regression, initially with a simple linear regression model (Y = β0 + β1X), followed by

second- (Y = β0+ β1X + β2X2) and third-degree (Y = β 0 +

β1X + β2X2 + β

3X3) polynomial models.

In order to avoid autocorrelation between points in the time series, the time variable was centered at the midpoint

of the series, as suggested by Kleinbaum et al.15

Choice of the best model was based on signiicance level

(p-value) and on residual analysis. Models were considered

statistically signiicant when p < 0.05.

Models were constructed for overall mortality in children

and adolescents under the age of 15, for mortality in males under the age of 15, and for mortality in females in the same age range.

Data analysis was carried out using the Microsoft Excel 2003 and SPSS version 15.0 software packages.

Results

Data on a total of 1,910 children were available for the

entire study period (1980 to 2006), with 848 leukemia deaths

in the city of Rio de Janeiro proper, 606 in the Metropolitan

Region (excepting Rio de Janeiro proper), and 456 for the Rio de Janeiro countryside (total in-state deaths, except for those recorded in the Metropolitan Region).

Trend analyses for the three geographic areas showed similar patterns of a constant, downward trend (Figure 1).

Comparison of trends by geographic area showed that the

city of Rio de Janeiro proper had the most marked decline

in mortality rates (-1.79 per three-year period), the highest coeficient of determination (R2 = 82.1), and the highest

statistical signiicance (p < 0.001) (Table 1).

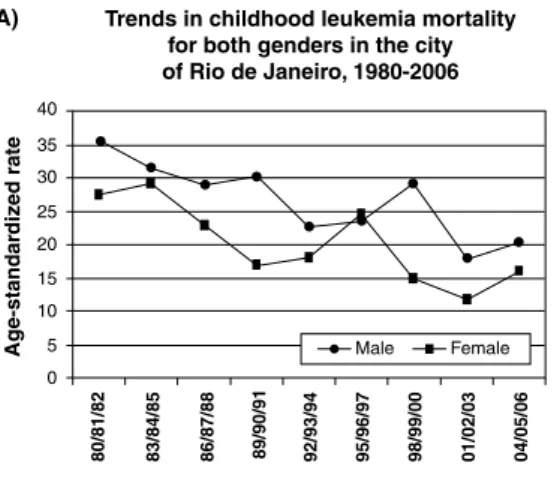

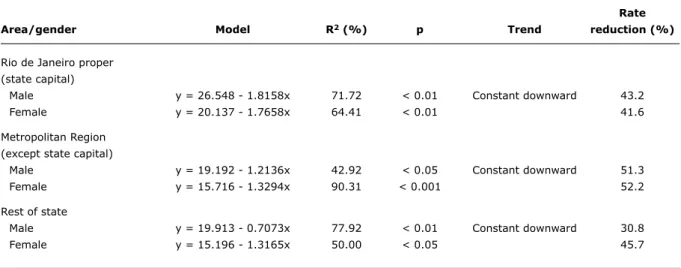

Analysis of mortality trends by gender showed a greater

incidence in males as compared to females in all studied

areas (Figure 2).

Fluctuations notwithstanding, mortality rates declined in both genders and in all three geographic areas throughout the series. In both genders, this decrease in mortality was greatest in the city of Rio de Janeiro proper (Table 2).

Discussion

Figure 1 - Childhood leukemia mortality trends in the state of Rio de Janeiro. A) City of Rio de Janeiro; B) Metropolitan Region (except for the city proper); C) rest of state

Figure 2 – Trends in childhood leukemia mortality by gender in the state of Rio de Janeiro. A) City of Rio de Janeiro; B) Metropolitan Region (except for the city proper); C) rest of state

results reported in the literature. In economically developed

regions, such as North America, Western Europe, Japan, and Oceania, a reduction in leukemia mortality rates in excess of 55% over the past three decades has been reported.10

In Brazil, a single study conducted in the city of Goiânia,

Rate

Area Model R2 (%) p trend reduction (%)

Capital (city proper) y = 23.378 - 1.7901x 82.15 < 0.001 Constant downward 42.5

Metropolitan Region

(except capital) y = 17.475 - 1.271x 72.46 < 0.01 Constant downward 34.8

Rest of state y = 17.536 - 1.0398x 66.52 < 0.01 Constant downward 47.4

Rate

Area/gender Model R2 (%) p trend reduction (%)

Rio de Janeiro proper (state capital)

Male y = 26.548 - 1.8158x 71.72 < 0.01 Constant downward 43.2

Female y = 20.137 - 1.7658x 64.41 < 0.01 41.6

Metropolitan Region (except state capital)

Male y = 19.192 - 1.2136x 42.92 < 0.05 Constant downward 51.3

Female y = 15.716 - 1.3294x 90.31 < 0.001 52.2

Rest of state

Male y = 19.913 - 0.7073x 77.92 < 0.01 Constant downward 30.8

Female y = 15.196 - 1.3165x 50.00 < 0.05 45.7

table 2 - Age-adjusted childhood leukemia mortality trends by gender in the state of Rio de Janeiro, 1980-2006

p = significance level; R2 = coefficient of determination.

table 1 - Age-adjusted childhood leukemia mortality rates by region in the state of Rio de Janeiro, 1980–2006

p = significance level; R2 = coefficient of determination.

protocols and the use of chemotherapeutic agents and combination regimens, which have substantially improved

survival of pediatric cancer patients, particularly those with

hematological malignancies.10,16

Advances in treatment and improvements in diagnosis of leukemia have been increasing survival of affected children. In Recife (state of Pernambuco), overall ive-year survival rates for childhood leukemia have risen from 32% (1980-1989) to 63% (1997-2002)17. Furthermore, treatment discontinuation and disease relapse rates on the order of

16 and 14%, respectively, were reported in the 1980s; between 1997 and 2002, these rates were 0.5 and 3.3%

respectively.

A case series of all patients admitted to the São Paulo Cancer Hospital for treatment (including previously treated

patients admitted for recurrent disease) also reported

improvement in ive-year survival, which reached 55% between 1995 and 1999, up from 13% two decades before (1975–1979).18

In addition to increased survival, reductions in childhood cancer mortality rates have also been reported in various

locations – evidence of improvement in diagnosis and

treatment services for pediatric cancer patients. In the United States, childhood leukemia mortality rates fell

roughly 50% between 1975 and 1995, for a statistically signiicant decrease of 3.4% per year, in both genders and across several age ranges.16 Considering the length of survival in pediatric leukemia patients in Brazil, mortality rates similar to those reported in developed nations may be found.19 This achievement may be ascribed to modern

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation – depending on

the type of neoplasm. These advances in treatment and

the use of speciic protocols have made cure rates of 75%

possible in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).20

A large study conducted in 17 European countries (European cancer registry-based study on survival and care of cancer patients – EUROCARE) to assess the impact of novel diagnostic and treatment methods introduced between 1983 and 1995 found that leukemias and lymphomas had the longest survival of all childhood cancers. EUROCARE concluded in favor of the eficacy of advances in childhood

cancer treatment in the studied countries, as results indicated that, due to new treatment models, the prevalence of adults with a history of childhood cancer is likely to increase.21

Viana et al.22 noted that experience in the treatment of

a complex illness such as leukemia, coupled with adoption of a uniied treatment protocol such as the Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (BFM) regimen, increases the possibility of prolonged

remission in children with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, an assessment of the BFM protocol conducted in

Brazil reported overall ive-year survival rates of 50.8%,

lower than those found in USA and European studies.23

In several locations, the incidence of ALL is reportedly

higher among male children than among girls.3,5,24 In

Brazil, studies conducted in the city of São Paulo have also shown higher mortality rates in boys as compared to girls.7 The present study detected a similar pattern in mortality:

through most of the series, childhood leukemia mortality rates were higher in male patients.

This study sought to characterize leukemia mortality trends in children and adolescents under the age of 15 in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Originally, data were to be analyzed at the municipal level; however, given the absence

of leukemia deaths in many municipalities, the choice was

made to group cases into eight predeined state health regions (Metropolitana, Serrana, Médio Paraíba, Norte, Baixada Litorânea, Noroeste, Centro-Sul, and Baía de Ilha

Grande) for which data were available in the DATASUS system.11 However, uneven population distribution across

these existing health regions made reliable analysis impossible. We therefore chose to divide the state into three broad regions for analysis: the city of Rio de Janeiro

proper (the state capital), the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan

Region (excepting the city of Rio de Janeiro), and the rest

of the state.

Comparison between regions showed that childhood

leukemia mortality rates declined most markedly in the

city of Rio de Janeiro proper. Mortality declined 42.5% in the capital (from 31.55 per 1,000,000 in children under the age of 15 between 1980 and 1982 to 18.14 per 1,000,000 between 2004 and 2006), 34.8% in the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region (from 22.11 to 14.41 per 1,000,000 respectively), and 47.4% in the remainder of the state (from

20.91 to 10.98 per 1,000,000 respectively).

Between 2001 and 2003, leukemia mortality rates in

children under the age of 15 in the city of Rio de Janeiro

(11.6 and 17.8 deaths per 1,000,000 in males and females

respectively) were higher than those recorded in the USA (7.0 and 8.6 per 1,000,000 respectively) and Western

Europe (6.3 and 9.9 per 1,000,000 respectively), whereas rates reported in Eastern Europe for the same period (13.8 and 17.6 per 1,000,000 respectively) were similar to those found in Brazil.25

In short, the childhood leukemia mortality trends found by the present study in the state of Rio de Janeiro are

likely due to improved access to healthcare allowing early diagnosis, which in turn translates to reduced mortality

rates. Overall, the data presented herein are consistent

with the current knowledge, as access to health services and early diagnosis are of the utmost importance in the prognosis of leukemia.

Although mortality rates are not directly representative

of health care accessibility with respect to cancer treatment, analysis of childhood cancer mortality rates may serve as

an indicator of the eficacy of cancer intervention strategies in the studied age range.10

One possible limitation of this study concerns quality of

information, ranging from the quality of information collection

and entry processes to the availability of data retrieved from the Mortality Information System. Furthermore, information is usually entered into the dataset by clerical staff and

non-medical professionals, and the system is thus subject to error, misinformation, and even missing data. In the state of Rio de Janeiro, however, a highly qualiied agency has

standardized mortality information for several years; the

percentage of overall deaths attributed to poorly deined causes has thus been low (3.75% of childhood deaths as

2007)11 since the 1980s.26-28

Conclusions

We detected a downward trend in childhood leukemia

mortality in the state of Rio de Janeiro, most prominently in the state capital. This mortality pattern is consistent with that described in the international literature, and may be

due to improved population access to diagnostic services and earlier diagnosis and treatment of hematological malignancies.

References

1. Hodgson S, Foulkes W, Eng C, Maher E. A practical guide to human cancer genetics. 3rd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

3. Linabery AM, Ross JA. Trends in childhood cancer incidence in the

U.S. (1992-2004). Cancer. 2008;112:416-32.

4. Shah A, Coleman MP. Increasing incidence of childhood leukaemia: a controversy re-examined. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1009-12. 5. Coebergh JW, Reedijk AM, de Vries E, Martos C, Jakab Z,

Steliarova-Foucher E, et al. Leukaemia incidence and survival in children

and adolescents in Europe during 1978-1997: report from the Automated Childhood Cancer Information System project. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:2019-36.

6. Ribeiro KB, Lopes LF, de Camargo B. Trends in childhood leukemia mortality in Brazil and correlation with social inequalities. Cancer. 2007;110:1823-31.

7. Mirra AP, Latorre MR, Veneziano DB. Incidência, mortalidade e sobrevida do câncer da infância no Município de São Paulo. São Paulo: Registro de Câncer de São Paulo; 2004.

8. Braga PE. Câncer na Infância: tendências e análise de sobrevida em Goiânia (1989-1996). Dissertação de Mestrado. São Paulo: Faculdade de Saúde Pública, USP; 2000.

9. La Vecchia C, Levi F, Lucchini F, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Negri E.

Trends in childhood cancer mortality as indicators of the quality of medical care in the developed world. Cancer. 1998;83:2223-7. 10. Linet MS, Ries LA, Smith MA, Tarone RE, Devesa SS. Cancer

surveillance series: recent trends in childhood cancer incidence and mortality in the United States. J Nati Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1051-8.

11. Ministério da Saúde, Brasil. Informações de Saúde. [website]

http://www.datasus.gov.br. Acesso: 15/06/2009.

12. Pedra F, Tambellini AT, Pereira Bde B, da Costa AC, de Castro HA.

Mesothelioma mortality in Brazil, 1980-2003. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2008;14:170-5.

13. Segi M. Cancer mortality for selected sites in 24 countries (1950-57). Department of Public Health, Tohoku University of Medicine, Sendai, Japan. 1960.

14. Doll R. Comparison between Registries and Age-Standardized Rates. In: Waterhouse JA, Muir CS, Correa P, Powell J, editors. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Vol III. Lyon: IARC; 1976. pp. 453-59.

15. Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Muller KE. Aplied regression analysis and other multivariable methods. 2nd ed. Belmont: Duxbury Press; 1988.

16. Ries LA, Smith MA, Gurney JG, Linet M, Tamra T, Young JL, et al. Cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975-1995. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 1999.

17. Howard SC, Pedrosa M, Lins M, Pedrosa A, Pui CH, Ribeiro RC, et al. Establishment of a pediatric oncology program and outcomes

of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a resource-poor area. JAMA. 2004;291:2471-5.

18. De Camargo B. Sobrevida e mortalidade da criança e adolescente com câncer: 25 anos de experiência em uma instituição brasileira [Tese]. São Paulo: Faculdade de medicina da Universidade de São Paulo; 2003.

19. Rodrigues KE, de Camargo B. Diagnóstico precoce do câncer

infantil: responsabilidade de todos. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2003; 49:29-34.

20. Margolin JF, Steuber CP, Poplack DG. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Willians e Wilkins; 2002. pp. 489-527.

21. Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Stiller C, Kaatsch P, Berrino F, Terenziani M; EUROCARE Working Group. Childhood cancer survival trends in Europe: A EUROCARE Working Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3742-51.

22. Viana MB, Cunha KC, Ramos G, Murao M. Leucemia mielóide aguda na criança: experiência de 15 anos em uma única instituição. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2003;79:489-96.

23. Laks D, Longhi F, Wagner MB, Garcia PC. Avaliação da sobrevida de

crianças com leucemia linfocítica aguda tratadas com o protocolo

Berlim-Frankfurt-Munique. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2003;79:149-58. 24. Swaminathan R, Rama R, Shanta V. Childhood cancers in

Chennai, India, 1990-2001: incidence and survival. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2607-11.

25. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). CANCERMondial. Globocan 2002. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. 26. Monteiro GT, Koifman RJ, Koifman S. Coniabilidade e validade dos

atestados de óbito por neoplasias. I. Coniabilidade da codiicação para o conjunto das neoplasias no Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Cad Saude Publica. 1997;13 Suppl 1:39-52.

27. Monteiro GT, Koifman RJ, Koifman S. Coniabilidade e validade dos atestados de óbitos por neoplasias. II. Validação do câncer de estômago como causa básica dos atestados de óbito no Município do Rio de janeiro. Cad Saude Publica. 1997;13 Suppl 1:53-65. 28. Queiroz RC, Mattos IE, Monteiro GT, Koifman S. Coniabilidade e

validade das declarações de óbito por câncer de boca no Município

do Rio de Janeiro. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19:1645-53.

Correspondence: Arnaldo Cézar Couto

Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública Sérgio Arouca Rua Leopoldo Bulhões, 1480, Sala 821 - Manguinhos CEP 21041-210 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - Brazil