FUNDAÇÃOGETULIO VARGAS

ESCOLA BRASILEIRA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO PÚBLICA E DE EMPRESAS MESTRADO EXECUTIVO EM GESTÃO EMPRESARIAL

Foreign Direct Investment and Security:

Simplifying the complexities

Dissertação apresentada à Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas para obtenção do grau de Mestre

TODD FORSMAN Rio de Janeiro - 2016

TODD FORSMAN

FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT AND SECURITY Simplifying the complexities

Masters thesis presented to Corporate International Master’s program, Escola Brasileira de

Administração Pública, Fundação Getulio Vargas, as a requirement for obtaining the title of Master in Business Management.

ADVISOR: RICARDO SARMENTO COSTA

Rio de Janeiro 2016

Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela Biblioteca Mario Henrique Simonsen/FGV

Forsman, Todd Patrick

Foreign direct investment and security: simplifying the complexities / Todd Forsman. – 2016.

57 f.

Dissertação (mestrado) - Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas, Centro de Formação Acadêmica e Pesquisa.

Orientador: Ricardo Sarmento Costa. Inclui bibliografia.

1. Administração financeira. 2. Empresas - Finanças. 3. Investimentos estrangeiros. I. Costa, Ricardo Sarmento. II. Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas. Centro de Formação Acadêmica e Pesquisa. III. Título. CDD – 658.15

Acknowledgments

This thesis is the result of a massive amount of support from a variety of important people in my life. I would like to take the opportunity to name a few and to say thank you here.

To my wife and children, thank you for tolerating my impatience and crassness as I endeavored to complete this undertaking during an already extremely stressful time in our lives. I could not have done it without your love and support and will be forever grateful to you all for putting up with me and loving me unconditionally.

To my thesis advisor, Ricardo, thank you for your patience, understanding, and flexibility throughout this process. I learned an immense amount about the topic at hand in this thesis, but even more from your mentorship and approach to studying, learning, and outlining my thoughts for others.

To the professors and staff of Fundação Getulio Vargas, Georgetown University, and ESADE University, I cannot thank you enough for the experience and education that you have provided me throughout this program. It was awesome.

To my fellow students of CIM 3, thank you for sharing your insights and time with me as we completed our journey. It has been my pleasure to be a part of this cohort, and I cannot wait to see what the future holds for us all.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction 1

1.1. Context 1

1.2. Objectives and justification 2

1.3. Level setting of terms 3

2. Literature Review 4

2.1. Review of literature on theories related to FDI 5

2.2. Review of literature on FDI and security 9

3. Methodology 10

3.1. Description of study 13

3.2. Discussion of variables and data used 18

3.3. Hypothesis 20

4. Discussion 21

4.1. Summary of results 22

4.2. Analysis and discussion of results 26

5. Conclusions 27

5.1. Implications of results 28

5.2. Limitations of results 29

5.3. Recommendations for further research 30

6. Bibliography

List of Illustratrations

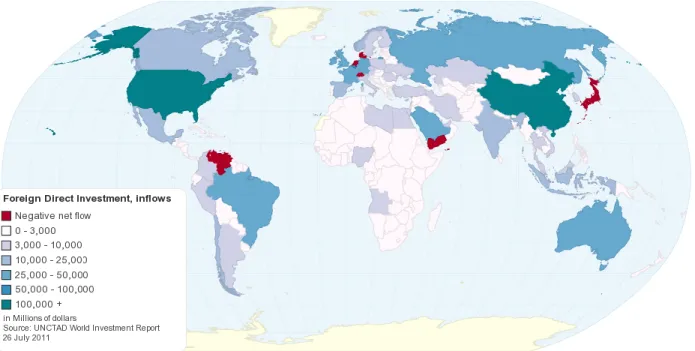

Figure 1: World map representing global FDI inflow data by country Figure 2: World map representing murder rate per capita data by country

Figure 3: Raw data shading legend for FDI Data

Figure 4: Raw data shading legend for murder rate data

List of Tables

Table 1: Regional analysis of normalized FDI versus murder rate per capita Table 2: Expected normalized correlation between FDI and murder rate per capita

Table 3: Country and regional analysis of normalized FDI and per capita murder rate data Table 4: Regional analysis of normalized FDI versus per capita murder rate data

Appendixes

Appendix A: Murder rate per capita raw and normalized data Appendix B: FDI raw and normalized data

List of Symbols, Abbreviations, and Acronyms GDP - Gross Domestic Product

FDI - Foreign Direct Investment IMF - International Monetary Fund WB - World Bank

UNCTAD - United Nations Conference on Trade and Development UNICEF - United Nations Children's Fund

WHO - World Health Organization

Abstract

The relationship between foreign direct investment and the security situation of a given country is complex and difficult to define. To further complicate matters, security is only one of many variables that drives the decision of a firm to invest in a particular country. This paper simplifies some of the complexities related to the study of this topic, especially as it relates to security, by expanding on previous research done at the country level and applying it at the regional level. It

concludes that the security situation of a given country can be approximated through the the independent variable of the annual per capita murder rate and that this rate is directly related with FDI in a given area. Business leaders can use this simple analysis as a starting point to aid in the decision in which country to invest in and why.

Keywords

Foreign Direct Investment; FDI; murder rate; security; regional analysis; Mexico; Nigeria; global level; country level; extrapolate

FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT AND SECURITY: Simplifying the complexities

“Everything is both simpler than we can imagine, and more complicated than we can conceive.”

- Goethe

1. Introduction

Students and scholars of international business management are often intrigued by the concept and study of foreign direct investment (FDI). At a base level, I believe they all ask themselves two fundamental questions at one point or another. First, why does one country choose to invest in another country? Next, what are the driving factors behind the decision on which country to invest in? The answers to these simple questions are immensely complex, but, arguably, the generally accepted logic to answer the first question as to why to invest in another country is to simply to generate more value for all stakeholders. This answer has political ramifications for businesses and governments that are outside of the scope of this paper, but the fact that it is generally understood to be logical and valid serves as a baseline for much of the discussion to come. Answers to the second question as to which country to invest in and why are far more diverse and even more complex still. Some argue geographic concerns. Others pose competitive advantage and market size based arguments based on resources available in a given country. Still other pose arguments based on incentives provided by governments to attract investment. Each argument is valuable to those desiring to understand FDI, but one factor that is often only minimally addressed is that of security and its impact on FDI.

1.1. Context

The advanced technology of today allows business leaders to operate easier than ever in the international context. Logistics and communications issues that once made business nearly impossible are now easily overcome and no longer significant barriers to expanding into emerging markets. Security concerns, on the other hand, continue to present significant

atmospheres associated with emerging markets. Further, many business leaders find themselves eager to take advantage of the technology that allows them to operate in emerging markets without fully understanding the security situation in the area. This often leads to costly security projects undertaken to mitigate risks only after profit reducing incidents force companies to do so; or, in the worst of cases, this leads to failed ventures altogether.

1.2. Objectives and justification

The purpose of this thesis is twofold. First, the analysis provided in this paper is intended to provide insights and understanding to those interested in better understanding the relationship between security and FDI by exploring the simple yet complex question: Is FDI in a given country affected by the overall security environment of said country? Next, assuming that the answer to the previous question is yes, this paper will then attempt to answer a related question: Can the murder rate of a given country serve as a simple indicator of security in a way that allows business leaders to quickly make an initial assessment regarding foreign direct investment?

The answers to the aforementioned questions are valuable to a variety of audiences including students, scholars, and business executives with an interest in international business operations. The resources that were required to complete this study are justified by the potential time and effort that can be saved by business leaders confronted with decisions related to FDI on behalf of their firms. Simplifying the enormous amount of data and analysis related to this topic in a way that provides a better foundation from which to build will allow business leaders to make more effective and timely decisions about their investments with a greater understanding of the topic at hand.

1.3. Level setting of terms

Many academic papers are written in a way that assumes all readers are on the same page when it comes to the understanding of the terms and definitions used to discuss and analyze the subject at hand. This is often an invalid assumption, even when the discussion remains between students and scholars of the topic. As such, the next chapter of this thesis is dedicated to

thoroughly defining the two most important terms used in the remainder of this paper: FDI and security. Both of these terms are often used in a general nature to discuss very complex and specific issues. Many times the biases and beliefs of one party's understanding of these terms differ greatly from the others involved in the same discussion. Spending some time to unpack the terms here will level set all readers and provide a solid baseline for discussion as we move forward.

Let us begin with defining and discussing the the term that many scholars, students, and business minded professionals would likely consider to be the simpler of the two - FDI. The term FDI is defined in a variety of forums easily available to interested parties. The Investopedia website provides perhaps the most simple and concise definition of FDI available in the body of literature:

“Foreign direct investment (FDI) is an investment made by a company or entity based in one country, into a company or entity based in another country. Foreign direct

investments differ substantially from indirect investments such as portfolio flows, wherein overseas institutions invest in equities listed on a nation's stock exchange. Entities making direct investments typically have a significant degree of influence and control over the company into which the investment is made. Open economies with skilled workforces and good growth prospects tend to attract larger amounts of foreign direct investment than closed, highly regulated economies.”

A more specific definition of FDI is provided by the International Monetary Fund (IMF): “A category of international investment that reflects the objective of a resident in one economy (the direct investor) obtaining a lasting interest in an enterprise resident in another economy (the direct investment enterprise). The lasting interest implies the existence of a long-term relationship between the direct investor and the direct investment enterprise, and a significant degree of influence by the investor on the management of the enterprise. A direct investment relationship is established when the direct investor has acquired 10 percent or more of the ordinary shares or voting power of an enterprise abroad.”

More importantly, the IMF addresses several misconceptions about FDI by further stating that FDI is not:

“ FDI does not necessarily imply control of the enterprise, as only a 10 percent ownership is required to establish a direct investment relationship. FDI does not comprise a “10 percent ownership” (or more) by a group of “unrelated” investors domiciled in the same foreign country, FDI involves only one investor or a “related group” of investors. FDI is not based on the nationality or citizenship of the direct investor, FDI is based on

residency. Borrowings from unrelated parties abroad that are guaranteed by direct investors are not FDI.”

This very inclusive definition provided by the IMF should not be ignored in the discussion, but for the purposes of this thesis, FDI can be thought of and visualized in a much more simplistic manner to aid one’s understanding of the topic. FDI is essentially brick and mortar investments by a firm with origins in a given country in a foreign country. Firm X literally invests in country Y by building a portion of the business in country Y rather than in its country of origin.

As a final note regarding FDI, it is important to understand the the study of FDI is

generally focused on inflows and outflows of investments. Some studies are concerned primarily with inflows into a given country. Others are concerned solely with the outflow of investment from a given country. Finally, some studies are concerned with the difference between the inflows and outflows of a given country. Each of these areas should be considered separately when studying this topic. This thesis is primarily concerned with the inflow of FDI into a particular country and how this inflow is affected by the security situation of said country.

Armed with this understanding of FDI, let us now move into a discussion of the term security as it relates to this thesis. Security is a much larger and often more ambiguously defined term than FDI in many ways. Security means different things to different people in different contexts. The term can conjure thoughts about assault, murders, robberies, corruption, crime, risk, terrorism, war, violence, lack of trust, financial risks, political risks, piracy, theft, rape, embezzlement, appropriation, nationalization among many, many, many others. There are no quantitative statistics that can be used to describe security in its entirety, and there are no simple analogies that can be used to say this area is secure and this area isn’t secure. It is most

definitely a loaded term that requires unpacking and discussion before moving forward in this analysis.

Merriam-Webster dictionary defines the term security as “the state of being protected or safe from harm”. This definition is very broad and vague when one attempts to analyze it, especially in the context of international business and FDI. It sparks a myriad of questions from the outset: What threats exist to a business? Are there more threats when operating in a foreign country? Can a business be protected or safe from harm? These questions are difficult and complex in and of themselves, but the logic behind security is somewhat simple to understand.

Business leaders will logically desire to operate in areas where there are less risks or less potential for losses or damages to the firm’s assets including their personnel, physical

infrastructure, financial resources, physical and intellectual property, and the reputation and brand of the firm. Firms will thus seek to minimize risks and maximize their rewards. In terms of FDI, this means that it is in the best interest of the firm to develop foreign investments in safer, more secure places in this context. This paper is concerned with the overall security environment of a given country and how that environment impacts the decisions of the leadership of a firm to invest in said country.

2. Literature Review

Foreign Direct Investment is the subject of a wide variety of academic research and study. Much of this research is dedicated to better understanding first why a firm would decide to directly invest in another country; and second, once the decision to invest abroad has been made, what drives the decision to directly invest in a particular country over another country. Upon initial foray into the study of this topic, it is very difficult to completely separate these two unique areas of study conceptually. The problem is exacerbated due to the level of

interconnectedness and the ease of operating globally made possible through the implementation of modern tools such as the internet and near accident free commercial aviation that we now take for granted. It is important to remember that these tools did not always exist which made

international business operations even more difficult and challenging than they are today making the study of the question as to why would a firm undertake such challenges to being with all the more interesting originally. The vein of study focused on why a firm decides to invest abroad in the first place serves as the foundation from which the remainder of the concepts discussed in this paper are built upon, and thus merits discussion and inclusion here before moving forward.

2.1. Review of literature on theories related to FDI

According to Jones and Wren (2006), the body of literature addressing the topic of why a firm decides to initiate foreign direct investments abroad began in the 1960s with a foundational thesis by Hymer focused on the international operations of firms that was later published in 1976. Hymer proposed that at a foundational level, firms move to invest directly in foreign countries because they desire to increase profits and believe this is possible through mergers or

acquisitions of foreign firms operating in the same space or because the firm has advantages over other firms operating in the foreign country. In short, Hymer proposed that firms move towards foreign direct investment because they feel that they have identified market imperfections that will allow their firm to be more profitable than if it were to remain confined within the borders of its original country. Vernon (1966) expanded on Hymer’s thoughts and introduced the product life cycle theory as it relates to location. His paper explored the decision to locate production abroad and concluded that the decision making process was far more complicated than a standard labor/cost analysis. Next, Caves (1971) explored horizontal and vertical considerations involved in the decision to invest abroad moving the discussion in line with the study of industrial

organization theory. Buckley and Casson (1976) moved the discussion in yet another direction by proposing what has is now known as internalisation theory through their study of why large firms internalize business operations outside of production such as marketing, training, research and development, and involvement with financial markets and how these functions can be addressed through investments abroad. Finally, the foundation of the more modern body of literature focused on the study of foreign direct investment was outlined in the eclectic paradigm outlined in Dunning (1977). Dunning proposes that a firm will directly invest in a foreign country only if the firm, first, possesses an owner specific asset which gives it an advantage over other firms; second, if the firm internalizes these assets rather than contracts them out; and third, that some sort of advantage exists for setting up shop in a foreign country rather than relying on exports from said country alone. Dunning’s work attempts to collate the ideas of Hymer, Vernon, Caves, Buckley and Casson into one overarching theory and sets the stage for the analysis and study to move into the direction it has taken today.

More modern study and research of foreign direct investment has moved away from understanding why a firm decides to invest abroad to the more specific study of what variables influence the decision on where exactly a firm should invest and why. Demirhan and Masca (2008) provide an excellent summary of existing research focused on the relationship between variables including market size, market openness, labor costs and productivity, infrastructure, growth, tax, and political risk with FDI. Faeth (2009) consolidates the analysis and conclusions of several notable authors in a comprehensive review of 9 theoretical models of the determinants of FDI including a brief discussion of protection and risk factors that can contribute to FDI related decisions. Bénassy‐ Quéré, Coupet, and Mayer (2007) provide insights on the impact of

institutions on FDI and conclude that the presence and strength of information, banking sector and legal institutions are directly related to FDI independently related to the size of the GDP of a given country. Akinlo (2004) concludes that labor force and human capital are important

determinants of FDI in Nigeria. Bekana (2016) concludes that GDP per capita, GDP growth rate, real interest rates, inflation rate, gross capital formation, adult literacy rate, labor force growth rate, telephone lines per 1,000 people and official exchange rate are the most important determinants of FDI. The list of independent variables that have on effect on FDI is long and varies greatly from author to author and work to work. What is perhaps most important in reviewing the work of the aforementioned authors is that the determinants of FDI in a particular country or region are extremely complicated as outlined in the introduction to this thesis. Theories abound as do explanations and insights provided by detailed analysis of very specific variables in very specific situations. However, it is very important to highlight, once again, that security concerns are often only addressed on the periphery and fall into the shadows of other perceived determinants of more importance.

2.2. Review of literature on FDI and security

The literature specifically dedicated to the implications of and affect of security concerns in relation to FDI is an exciting and relatively new addition to the overall discussion at hand. In general terms, this literature is focused on several security related topics as they relate to FDI: crime, violent crime, corruption, internal and external conflicts such as war and terrorism, and political risk and instability.

Crime and the related, but slightly different, topic of violent crime are the subject of several notable academic works that are foundational to this paper and merit mention here. Danielle, et al. (2008, 2010) provides excellent insights as to how crime can affect FDI by studying Italy and the role of organized crime in the country. These studies conclude that organized crime specifically results in local market conditions that are perceived as highly unfavorable for FDI. Similarly, Blanco, Dadzie, and Dony (2014) conclude that crime affects investments in Latin America. In a 2006 study by Pshisva and Suarez (2006) focused on the impact of crime in Colombia, targeted corporate kidnappings and their effect on FDI are examined. The study concludes that corporate kidnappings have a direct and profoundly

negative effect on FDI in a given region, but general crimes such as homicides, guerrilla attacks, and general kidnappings have no significant effect on FDI. Camacho and Rodriguez (2013) similarly study Colombia and conclude that violent crime actually lead to complete firm exits of a country. Rojas (2009) concludes that FDI is correlated to violent crime, GDP and minimum wages in a study of murder rate and FDI throughout Mexico. Ashby and Ramos (2013) use an analysis of murder rate data and sector specific FDI data in Mexico to conclude that organized crime has a negative impact on FDI in the financial services, commerce, and agriculture. Interestingly, they conclude that organized crime does not have an impact on the oil and mining sectors or manufacturing sectors. Enders and Sandler (1996) suggest that terrorism is yet another risk factor that could affect FDI. They conclude that terrorism in Spain and Greece led to a persistent and significant negative influence on FDI stocks and flows. Li (2003, 2006, 2008, 2009) are studies that focus on political violence, interstate military conflict, and democratic institutions and their impact on FDI. Al-Sadig (2009) highlights the negative effects of corruption on FDI. Finally, Oriakhi and Osemwengie (2012) conclude that security issues in Nigeria are a major factor preventing the growth of FDI in the country.

As you can see from this brief review of existing the existing literature on this topic, conclusions and methods as to how to best investigate the relationship between security and FDI are varied. Some conclude that security concerns are very important in FDI related decisions; whereas others conclude that security concerns have insignificant impacts on FDI. In general terms, however, it should be noted that the fact that security concerns as they relate to FDI are the subject of this wide variety of academic research and study points to the fact that many people believe that there is a relationship at some level that is, if nothing else, worthy of the time required to study the topic. Further, it should be noted that the vast majority of studies dedicated to this topic find some correlation between FDI and security, thus partially answering the first question driving this research.

3. Methodology

Moving forward, the next portion of this paper is dedicated to describing the details of how this study was planned and executed. It begins with the following brief discussion of the conceptual framework applied to the methodology selected for this study.

Business executives are extremely busy people tasked with making difficult decisions in timely scenarios on a regular basis. The decision as to which country to invest in and why is no different than any other business decision confronted by the firm. Executives should make the best use of their time understanding and analyzing all available information in order to make the best decision possible for all stakeholders of the firm. However, significant care should be taken to prevent delving too far into the weeds in a way that leads to indecision.

In keeping with this idea, the exploratory, descriptive research and analysis provided in the remainder of this paper is based on easily available data that is represented in a visual format instantly available to decision makers. This is in contrast to some of the more traditional

statistical and data based methodologies that currently dominate the literature related to this topic. The decision to forego more traditional analysis is by design and meant to simplify the complex in a way that promotes actual use of the findings of this paper by real world business executives.

3.1. Discussion of variables and data used

FDI is the obvious dependent variable of interest in this study. Security is the more ambiguous, independent variable. As previously discussed, it is very difficult to approximate the overall security environment of a given country with one variable. Understanding this and the complexities at hand, this study uses the murder rate per capita to represent the overall security environment of a particular country. Various other variables such as literacy, kidnapping rate, crime rate, the global peace index and the failed state index were considered as representative of the overall security situation in a given country. Ultimately, it was decided that the per capita murder rate was the best choice for the given goal of this study in simplifying security related effects on FDI because this type of data is available, regularly updated, and has been previously used in several noteworthy studies such as Rojas (2009) and Oriakhi and Osemwengie (2012) that provide the foundation for this thesis.

The raw data sets used for both FDI and murder rate per capita were accessed and downloaded from chartsbin.com. Data for FDI was provided by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Murder rate per capita was provided from a variety of sources to include the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Survey of Crime

Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), and various national level organizations. This data was compiled by chartsbin.com and rendered into visual form on the website. Complete raw data sets are available in Appendixes A and B of this thesis. A more detailed discussion of how this data was used in the study appears in the discussion section of this paper.

3.2. Hypothesis

Several of the existing studies analyzed during the research phase of this thesis concluded that the murder rate per capita is directly related to the level of FDI in a particular country. Of particular note, Rojas (2009) and Oriakhi and Osemwengie (2012) found this relationship to be valid in Mexico and Nigeria respectively. Rojas used state by state data from Mexico to

demonstrate that states within Mexico that have higher murder rates have lower FDI. Similarly, Oriakhi and Osemwengie (2012) arrived at a similar conclusion by studying the security

situation as it relates to FDI in Nigeria. In general, the hypothesis in both studies can be summarized by stating that the per capita murder rate of a given geographic area is directly related to the expected level of FDI in that same area. If this hypothesis and the conclusions reached by Rojas and Oriakhi and Osemwengie are valid, it should be possible to apply the model outside of Mexico and Nigeria and at a regional level. At any given point in time, countries with high per capita murder rates should have low FDI, and countries with low per capita murder rates should have higher FDI. This logic serves as the foundation of the remaining analysis and discussion of this thesis which is designed prove or disprove the notion that the simple statistic of murder rate per capita can be used to summarize the security situation in a given country in order to facilitate the decision making process for business leaders tasked with such undertakings.

In order to test the aforementioned hypothesis and extrapolate the conclusions reached by Rojas (2009) and Oriakhi and Osemwengie (2012) to a regional level in a simple and time efficient manner, it was decided that a visual representation of available data should serve as the foundation of the analysis. Visual representations of data provide enormous amounts of

information instantly which in turn rapidly facilitates the decision making process. This is in line with the overall objective of this thesis as outlined in the introduction. The bedrock of the

analysis and discussion presented in the remainder of this thesis is presented in Figures 1 and 2 below. Figure 1 below is a visual representation of global FDI inflow data collected by

UNCTAD from 2011 as presented on chartsbin.com. Figure 2 is a visual representation of global murder rates per capita collected from a variety of sources representing the most recent data available also as presented by chartsbin.com. Of note, both figures appear here in static form, but are available at chartsbin.com in a fully inteactive format that further facilitates a rapid analysis. In the remainder of this section, these Figures and the underlying data use to develop them will be analysed in order to validate the simple model proposed by Rojas (2009) and Oriakhi and Osemwengie (2012).

Figure 2. World map representing global murder rate per capita data by country

To begin the process, a general visual analysis comparing FDI to per capita murder rate using Figures 1 and 2 seems to validate the hypothesis at a regional level. Areas represented by shadings schemes representative of high per capita murder rates are the same areas representative of shading schemes representative of lower FDI and vice versa. For example, Central America is shaded in deep red on Figure 2 indicating a high per capita murder rate. It is shaded in white indicating a low level of FDI in figure 1. Similarly, Africa in general presents significant red shading in Figure 2 that correlates to white shading in Figure 1. This simple conclusion is very important and valid; however, it was decided that a more detailed, yet still simple, analysis of the data would be required to fully validate the hypothesis.

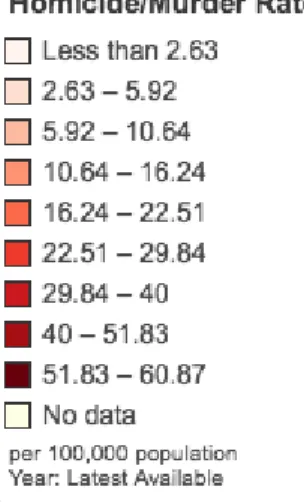

Moving forward, both the FDI and per capita murder rate raw data sets were normalized in order to simplify the available information and provide a functional method to analyze it. The normalization process for both the FDI and per capita murder rate raw data was completed by assiging a value between 1 and 7 based on the initial ranges provided in the legends of the visual representations originally provided by chartsbin.com and redisplayed in Figures 1 and 2. The data ranges represented in the original legends are available in Figures 3 and 4 below in order to ease the reader's understanding of this process.

Figure 3. Raw data shading legend for FDI Data

Figure 4. Raw data shading legend for murder rate data

Of note, FDI data was originally presented in 7 categories, whereas murder rate data was originally presented in 9 categories making a direct comparison challenging. Under the

assumption that a very high or a very low murder rate would have similar effects on FDI, the top and bottom ends of the original murder rate spectrum were combined in order to create 7 values to ease the comparison process between the two variables. Since the variables are inversely correlated according to the hypothesis being tested, a value of 1 for murder rate was anticipated to correlate with a value of 7 for FDI and vice versa. Expected correlation between the

normalized values for both data sets are displayed in the table below:

Table 2. Expected normalized correlation between FDI and Murder Rate

Foreign Direct Investment Murder Rate

Raw Value Normalized Value Raw Value Normalized Value

Negative Net flow 1 51.83 - 60.87 7

Negative Net flow 1 40 -51.83 7

0-3,000 2 29.84 -40 6 3000 -10,000 3 22.51 - 29.84 5 10,000-25,000 4 16.24-22.51 4 25,000-50,000 5 10.64-16.24 3 50,000-100,000 6 5.92-10.64 2 100,000+ 7 2.63-5.92 1 100,000+ 7 Less than 2.63 1

Moving forward, the raw data for both FDI and per capita murder rate was normalized and compiled for further analysis. This process was completed for every country in which there was available data. Results were compiled in table format and are available in Appendix A and B of this paper.

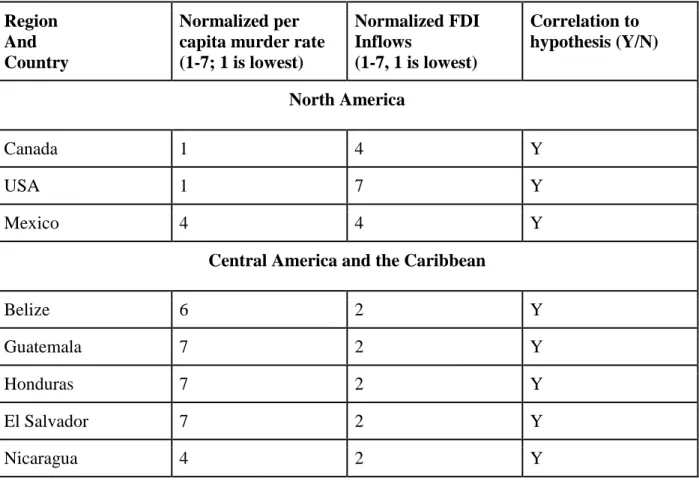

Next, it was decided that a country by country analysis of the relationship between FDI and the per capita murder rate for data available in the Americas and Africa would be conducted

in order further examine the hypothesis. The Americas and Africa were chosen specifically for this portion of the analysis because the conclusions by Rojas (2009) and Oriakhi and

Osemwengie (2012) originated in a country specific analysis of a country that is a part of these regions. Normalized FDI and per capita murder rate data was compiled for all countries in which there was available data for these regions. Further, this data was processed using the expected correlation information provided in Table 3 in order to validate the relationship between the variables. In order to account for abnormalities associated with the normalization process and with the raw data available, it was determined that countries presenting a correlation between FDI and per capita murder rate within 2 values of the expected value as presented in table 3 would be considered to have demonstrated a correlation to the hypothesis. This result was recorded as either a Y for Yes or a N for No by country. The results of this process are shown in Table 3 below. Of note, countries that did not conform to the expected hypothesis are

highlighted in the table.

Table 3. Country and regional analysis of normalized FDI and per capita murder rate data

Region And Country

Normalized per capita murder rate (1-7; 1 is lowest) Normalized FDI Inflows (1-7, 1 is lowest) Correlation to hypothesis (Y/N) North America Canada 1 4 Y USA 1 7 Y Mexico 4 4 Y

Central America and the Caribbean

Belize 6 2 Y

Guatemala 7 2 Y

Honduras 7 2 Y

El Salvador 7 2 Y

Panama 4 2 Y Cuba 2 2 N Dominican Republic 4 2 Y Haiti 4 2 Y Jamaica 7 2 Y South America Venezuela 7 1 Y Colombia 7 3 Y Ecuador 4 2 Y Peru 1 3 N Bolivia 3 3 Y Chile 2 4 Y Argentina 1 3 N Uruguay 1 2 N Paraguay 3 2 N Brazil 4 5 Y Suriname 4 2 Y Guyana 5 2 Y Africa Egypt 1 3 N Libya 1 3 N Nigeria 1 3 N Angola 6 3 Y Morocco 1 2 N Algeria 1 2 N

Tunisia 1 2 N Mauritania 4 2 Y Mali 5 2 Y Niger 5 2 Y Chad 5 2 Y Sudan 5 2 Y Eritrea 4 2 Y Ethiopia 4 2 Y Somalia 1 2 N Kenya 1 2 N Uganda 2 2 N Democratic Republic of Congo 6 2 Y Central African Republic 6 2 Y Cameroon 1 2 N Benin 3 2 N Burkina Faso 1 2 N Cote d’Ivoire 1 2 N Liberia 4 2 Y Sierra Leone 1 2 N Guinea 1 2 N Guinea-Bissau 4 2 Y Senegal 3 2 N Togo 3 2 N Gabon 5 2 Y

Republic of Congo 4 2 Y Tanzania 5 2 Y Mozambique 4 2 Y Zambia 5 2 Y Zimbabwe 6 2 Y Botswana 3 2 N Namibia 4 2 Y South Africa 6 2 Y Madagascar 3 2 N 4.1. Summary of Results

The normalization and analysis process was conducted for 64 countries that were further broken down into four distinct regions. As a final step to the analysis and in an effort to

consolidate results at a regional level, country level data was averaged and compiled into region level data. The results of this process serve as summary for the entire analysis and are presented in the table below:

Region Normalized Murder Rate (1-7; 1 is lowest) Normalized FDI Inflows (1-7, 1 is lowest) Correlation to hypothesis (Y/N) Specific Exceptions by country

North America 2 5 Y none

Central America 5.9 2 Y Cuba

South America 3.5 2.7 Y Perú, Argentina,

Uruguay, Paraguay

Africa 3.3 2.1 N Madagascar, Botswana,

Togo, Senegal, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Cameroon, Benin, Burkina, Uganda, Kenya, Somalia, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Egypt, Libya, Nigeria

4.2 Analysis and discussion of results

Detailed analysis of Tables 3 and 4 shows that the conclusions presented by Rojas (2009) and Oriakhi and Osemwengie (2012) that were investigated in this thesis proved true in 63% of the countries examined (40 out of 64) using the approach outlined. When evaluated at a

regional level, the conclusions proved true in 75% of regions analyzed. Specific exceptions to the expected outcomes are identified in the last column of Table 4 and will serve as the foundation of the remaining discussion in this section as the results of each region are further discussed.

In examining the results of our analysis in the North American region, it appears that there is very little to discuss. In both the US and Canada, low murder rates correspond to

medium to very high levels of FDI. Similarly in Mexico a medium murder rate corresponds to a medium level of FDI. However, this is perhaps an excellent juncture to point out that a regional analysis does not account for the intricacies of a detailed country analysis such as the one provided by Rojas (2009) in the case of Mexico specifically. Analysis of individual state level data in the case of Mexico specifically yielded an entirely new level of specificity from applying this same logic used here at the regional level.

Moving into Central America, again it appears that there is very little to discuss upon examining the table. Nearly of the countries in Central America present very high per capita

murder rates and correspondingly low FDI. This is very much an expected outcome in

evaluating our hypothesis. Of note, however, is the case of Cuba, which presents a lower murder rate, but also a low level of FDI. This is interesting and noteworthy although it is perhaps easily explained by the the state of Cuba’s relations with the United States as defined by the embargo. Also worthy of discussion here, it is important to note that the countries of Central America and the Caribbean are small in comparison to other countries in the region and across the globe. This size of the available market could be a factor that influences the outcome of our analysis in these cases.

Next in the discussion is South America. The countries of this region appear to conform very well to the hypothesis and our expected outcomes. Venezuela in particular demonstrates a high per capita murder rate and a correspondingly very low, negative in fact, level of FDI. Other exceptional cases in the region include Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay. At first glance, it is difficult to surmise exactly why these countries would present low murder rates, but also low FDI rates. Perhaps geographic distance is another factor that could be explored in these cases. Brazil is an interesting case as well. It conforms to the expected outcome using the described methodology, but barely. This is a likely indicator that, like Mexico, individual state analysis would yield an entirely different level of specificity if examined.

Finally, we move to Africa to conclude the discussion of the results of this study. It is immediately apparent that Africa is the only region that failed to demonstrate conformity to our expected outcome. This begs the question as to why this is the case. Leaving the data aside and returning to the visual representations in Figures 1 and 2, it appears that Sub-Saharan Africa generally conforms to our the expected outcome of testing the hypothesis, but North Africa deos not. North Africa displays low murder rates, but unexpectedly low levels of FDI. This could be due to a variety of reasons including the fact that much of North Africa is a desert with very few resources available for direct investment. The rest of Africa, however, appears to conform with our expected outcome. Countries with higher murder rates have lower levels of FDI.

More detailed analysis of the data yields another very interesting case to discuss in Nigeria. According to the data used in this study, Nigeria presents with a low murder rate and a low level of FDI. At first glance, this is seemingly contrary to the conclusions presented by Oriakhi and Osemwengie (2012) that serve as the foundation for this study. However, the discrepancy is easily accounted for if one recalls that Oriakhi and Osemwengie (2012) used very

detailed state level data in their analysis that included events such as kidnappings, guerrilla attacks, etc. in addition to simply the murder rate. The example serves well to demonstrate, once again, that more detailed analysis using more stringently defined variables will likely yield more detailed results. It will also very likely take exponentially more time to execute the study in order to account for this level of detail.

5. Conclusions

In closing, this thesis was designed to prove or disprove the notion that the security situation of a given country is directly related to the level of FDI in said country. Further, this study attempted to extrapolate country level conclusions based on an analysis of the per capita murder rate and the level of FDI presented by Rojas (2009) for Mexico and Oriakhi and

Osemwengie (2012) for Nigeria to a regional level in an effort to prove or disprove the efficiency of using the per capita murder rate to approximate the security situation of a given country. Quantitatively, the conclusions presented by Rojas (2009) and Oriakhi and Osemwengie (2012) and investigated in this thesis proved true in 63% of the countries examined (40 out of 64), using the approach outlined in this thesis. When evaluated at a regional level, the conclusions proved true in 75% of regions analyzed. Though not a perfect correlation, these results are far from insignificant. The demonstrate the validity of the argument that the per capita murder rate is directly linked to the expected level of FDI in a given country in a strong majority of the cases investigated.

5.1 Implications of Results

In general terms, the results of this study are not earth shattering and were in accordance the expected outcome of the study. However, they are very significant in that they clearly demonstrate that the relationship between the per capita murder rate and FDI can and should be used at least as an initial barometer test when it comes to decisions related to the location of FDI. Areas in which there is a higher per capita murder rate or in which the per capita murder rate is

altogether avoided; it merely indicates that managers responsible for business operations in these areas should go into things with their eyes wide open and spend more time and effort on plans to mitigate the potential risks. This study also demonstrates that in certain cases, a more detailed approach will be necessary to accurately reflect the security situation prior to making any FDI related decisions. The level of effort and dedication of resources required for this level of analysis can, however, be avoided if the firm decides to operate in areas that more or less conform to the hypothesis.

5.2 Limitations of Results

All studies have limitations. Most are related to source of the data used in the analysis or the way in the data was interpreted in the study. This study is no different. There are three main limitations to the results provided through the analysis presented in this paper: the use of per capita murder rate data gathered from various sources and at varied times is less than ideal; the normalization process used to prepare the data for analysis was very general and simplistic in nature which could have led to the loss of data in a way that could have skewed the results; and lastly, the analysis and subsequent conclusions were based on only one one snapshot in time which is also less than ideal. These three issues are significant on one hand, but, if one recalls that the broader purpose of this study was to simplify the complexities of this topic in a way that would yield a model for analysis that could be easily applied by business leaders tasked with making decisions related to this topic, the end goal was accomplished very effectively by using the data available.

5.3 Recommendations for further research

The relationship between security and FDI is complex in nature and can be analyzed through a variety of methods and by using a variety of data. In order to truly prove the

hypothesis examined in this thesis, a similar study conducted over a larger period of time should be completed. Specific attention should be placed on countries where the murder rate has changed over time and how that change has affected the level of FDI in that country. That said, the results of this study prove that business leaders can use the per capita murder rate in a given

country as an initial barometer test to as to the the viability of FDI into said country in order to speed up their decision making process. However, the results of this also study show that the relationship between per capita murder rate and FDI is not as strong as expected in some cases, likely due to locale specific factors not addressed in this analysis. This suggests that a more detailed analysis could be required as the decision to invest is necked down from country, to state or subregion, and to individual municipality or town. Business leaders and scholars alike should keep this in mind when investigating this topic.

Bibliography

Al-Sadig, A. (2009). The Effects of Corruption on FDI Inflows. Cato Journal,29(2), 267-294.

Akinlo, A. E. (2004). Foreign direct investment and growth in Nigeria: An empirical investigation. Journal of Policy Modeling, 26(5), 627-639.

Ashby, N. J., & Ramos, M. A. (2013). Foreign direct investment and industry response to organized crime: The Mexican case. European Journal of Political Economy, 30, 80-91.

Al-Sadiq, Ali J. (2013). Outward foreign direct investment and domestic investment: The case of developing countries (IMF Working Paper No. 13/52). International Monetary Fund.

Barry, C. M. (2013). Conflict, cooperation, and the multinational corporation: Security and

foreign direct investment in the developing world (Order No. 3596998). Available from ProQuest

Dissertations & Theses Global. (1449822543). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1449822543?accountid=11091

Bekana, D. M. (2016). Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment in Ethiopia: Time Series evidence from 1991-2013. The Journal of Developing Areas, 50(1), 141-155.

Bénassy‐ Quéré, A., Coupet, M., & Mayer, T. (2007). Institutional determinants of foreign direct investment. The World Economy, 30(5), 764-782.

Blanco, L., Dadzie, C., & Dony, C. (2014). Study on Crime and Investment in Latin America and the Caribbean. United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. (1976). Future of the multinational enterprise. Springer.

Camacho, Adriana, & Rodriguez, Catherine (2013) Firm exit and armed conflict in Colombia. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 57(1): 89-116.

Caves, R. E. (1971). International corporations: The industrial economics of foreign investment.

Economica, 38(149), 1-27.

Constantinou, Evangelos (2011) "Has Foreign Direct Investment exhibited sensitiveness to crime across countries in the period 1999-2004? And if so, is this effect non-linear?," Undergraduate Economic Review: Vol. 7: Iss. 1, Article 15. Available at:

http://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/uer/vol7/iss1/15

Daniele, V., & Marani, U. (2008). Organized crime and foreign direct investment: the Italian case.

Daniele, V. (2010). The Burden of Crime on Development and FDI in Southern Italy. The

Demirhan, E., & Masca, M. (2008). Determinants of foreign direct investment flows to developing countries: a cross-sectional analysis. Prague economic papers, 4, 356-369.

Dunning, J. H. (1977). Trade, location of economic activity and the MNE: A search for an eclectic approach. In The international allocation of economic activity (pp. 395-418). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Dupasquier, C., & Osakwe, P. N. (2006). Foreign direct investment in Africa: Performance, challenges, and responsibilities. Journal of Asian Economics,17(2), 241-260.

Enders, W., & Sandler, T. (1996). Terrorism and foreign direct investment in Spain and Greece.

Kyklos, 49(3), 331-352.

Faeth, I. (2009). Determinants of foreign direct investment–a tale of nine theoretical models.

Journal of Economic Surveys, 23(1), 165-196.

Gemayel, E. (2004). Risk instability and the pattern of foreign direct investment in the Middle East and North Africa region.

Gómez Soler, Silvia C. (2012) The Interplay between Organized Crime, Foreign Direct

Investment and Economic Growth: The Latin American Case. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana: Bogota.

Graham, E. M., & Marchick, D. (2006). US national security and foreign direct investment.

Peterson Institute Press: All Books.

Hymer, S. H. (1976). The international operations of national firms: A study of direct foreign

investment (Vol. 14, pp. 139-155). Cambridge, MA: MIT press.

Lankes, H. P., & Venables, A. J. (1996). Foreign direct investment in economic transition: the changing pattern of investments. Economics of Transition, 4(2), 331-347.

Larraín, F., Lopez-Calva, L. F., & Rodriguez-Clare, A. (2000). Intel: a case study of foreign direct investment in Central America. Center for International Development Working Paper, 58.

Lemi, A., & Asefa, S. (2003). Foreign direct investment and uncertainty: Empirical evidence from Africa. African Finance Journal, 5(1), p-36.

Li, Q., & Resnick, A. (2003). Reversal of fortunes: Democratic institutions and foreign direct investment inflows to developing countries. International organization, 57(01), 175-211.

Li, Q. (2006). Political violence and foreign direct investment. Research in global strategic

management, 12, 231-55.

Li, Q. (2008). Foreign direct investment and interstate military conflict.Journal of International

Affairs, 62(1), 53.

Li, Q. (2009). Democracy, autocracy, and expropriation of foreign direct investment.

Comparative Political Studies.

Li, S. (2005). Why a poor governance environment does not deter foreign direct investment: The case of China and its implications for investment protection. Business Horizons, 48(4), 297-302.

Lipsey, R. E. (2001). Foreign direct investment and the operations of multinational firms:

Concepts, history, and data (No. w8665). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Madrazo Rojas, Federico (2009). The effect of violent crime on FDI: The case of Mexico 1998-2006 (Master Thesis). Department of Public Policy, Georgetown Public Policy Institute.

Moran, T. H. (1998). Foreign direct investment and development: The new policy agenda for

Moran, T. H. (2004). Beyond sweatshops: Foreign direct investment and globalization in

developing countries. Brookings Institution Press.

Ok, S. T. (2004). What drives foreign direct investment into emerging markets?: evidence from Turkey. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade,40(4), 101-114.

Oriakhi, D., & Osemwengie, P. (2012). The Impact of national security on foreign direct investment in Nigeria: An empirical analysis.

Ozawa, T. (1992). Foreign direct investment and economic development.Transnational

Corporations, 1(1), 27-54.

Pshisva, R., & Suarez, G. A. (2006). Captive markets: The impact of kidnappings on corporate investment in Colombia.

Riascos, Alvaro, & Vargas, Juan Fernando (2011) Violence and growth in Colombia: A review of

the quantitative literature. Economics of Peace and Security Journal, 6(2).

Rosecrance, R., & Thompson, P. (2003). Trade, foreign investment, and security. Annual Review

of Political Science, 6(1), 377-398.

Tuman, J. P., & Emmert, C. F. (2004). The political economy of US foreign direct investment in Latin America: a reappraisal. Latin American Research Review, 39(3), 9-28.

Urata, S., & Kawai, H. (2000). The determinants of the location of foreign direct investment by Japanese small and medium-sized enterprises. Small Business Economics, 15(2), 79-103.

Vernon, R., & Wells, L. T. (1966). International trade and international investment in the product life cycle. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 81(2), 190-207.

Zarsky, L. (1999). Havens, halos and spaghetti: untangling the evidence about foreign direct investment and the environment. Foreign direct Investment and the Environment, 47-74.

Appendix A: Country level normalization data and regional calculations

Table 3. Country Analysis

Region And Country Normalized Murder Rate (1-7; 1 is lowest) Normalized FDI Inflows (1-7, 1 is lowest) Correlation to hypothesis (Y/N) North America 2 5 Y Canada 1 4 Y USA 1 7 Y Mexico 4 4 Y Central America and the Caribbean

5.9 2 Y

Belize 6 2 Y

Guatemala 7 2 Y

Honduras 7 2 Y

Nicaragua 4 2 Y Panama 4 2 Y Cuba 2 2 N Dominican Republic 4 2 Y Haiti 4 2 Y Jamaica 7 2 Y South America 3.5 2.7 Y Venezuela 7 1 Y Colombia 7 3 Y Ecuador 4 2 Y Peru 1 3 N Bolivia 3 3 Y Chile 2 4 Y Argentina 1 3 N Uruguay 1 2 N Paraguay 3 2 N Brazil 4 5 Y Suriname 4 2 Y Guyana 5 2 Y Africa 3.3 2.1 N Egypt 1 3 N Libya 1 3 N Nigeria 1 3 N Angola 6 3 Y Morocco 1 2 N Algeria 1 2 N

Tunisia 1 2 N Mauritania 4 2 Y Mali 5 2 Y Niger 5 2 Y Chad 5 2 Y Sudan 5 2 Y Eritrea 4 2 Y Ethiopia 4 2 Y Somalia 1 2 N Kenya 1 2 N Uganda 2 2 N Democratic Republic of Congo 6 2 Y Central Africa Republic 6 2 Y Cameroon 1 2 N Benin 3 2 N Burkina Faso 1 2 N Cote d’Ivoire 1 2 N Liberia 4 2 Y Sierra Leone 1 2 N Guinea 1 2 N Guniea-Bissau 4 2 Y Senegal 3 2 N Togo 3 2 N Gabon 5 2 Y

Republic of Congo 4 2 Y Tanzania 5 2 Y Mozambique 4 2 Y Zambia 5 2 Y Zimbabwe 6 2 Y Botswana 3 2 N Namibia 4 2 Y South Africa 6 2 Y Madagascar 3 2 N

Appendix B. Murder rate per capita raw and normalized data Country Rate (per 100k popula tion) Nor mali zed Valu e Year Source Afghanistan 3.44 1 2004 WHO Albania 3.29 1 2007

TransMONEE 2009 database, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre

Algeria 0.64 1 2006

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Andorra 1.3 1 2004 Interpol

Angola 38.59 6 2004 WHO

Anguilla 27.61 5 2007 National Statistical Office

Antigua and Barbuda 8.49 2 2004 Pan American Health Organization

Argentina 5.24 1 2007 Ministry of Justice

Armenia 2.53 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Australia 1.23 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Austria 0.58 1 2008

Europen Health for All database - Homicide and intentional injury

Azerbaijan 2 1 2007

TransMONEE 2009 database, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre

Bahamas 22.4 4 2004 WHO

Bahrain 0.77 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Bangladesh 2.56 1 2008 National Police

Barbados 17.42 4 2004 WHO

Belarus 5.56 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Belgium 1.83 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Belize 34.26 6 2008 National Police

Benin 13.74 3 2004 WHO

Bermuda 1.56 1 2004

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Bhutan 1.36 1 2006 National Statistical Office

Bolivia (Plurinational

State of) 10.64 3 2007 National Statistical Office

Bosnia and Herzegovina 1.8 1 2008 Ministry of Interior

Botswana 11.9 3 2006

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Brazil 21.97 4 2008 Ministry of Justice

Brunei Darussalam 0.53 1 2006

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Bulgaria 2.27 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Burkina Faso 0.49 1 2006 National Statistical Office

Burundi 37.38 6 2004 WHO

Cameroon 2.28 1 2007

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Canada 1.67 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Cape Verde 11.39 3 2007 Report of an international organization

Central African Republic 29.84 6 2004 WHO

Chad 19.18 4 2004 WHO

Chile 8.1 2 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

China 1.21 1 2007 National Statistical Office

Colombia 40.1 7 2007 National Statistical Office

Comoros 11.95 3 2004 WHO

Congo 19.9 4 2004 WHO

Costa Rica 8.28 2 2007 National Police

Cote d'Ivoire 0.37 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Croatia 1.61 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Cuba 5.5 1 2006 Pan American Health Organization

Cyprus 1 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Czech Republic 1.96 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems Democratic People's

Republic of Korea 19.25 4 2004 WHO

Democratic Republic of

the Congo 34.99 6 2004 WHO

Denmark 1.4 1 2007 Eurostat

Djibouti 3.41 1 2004 WHO

Dominica 5.92 2 2004 Pan American Health Organization

Dominican Republic 21.51 4 2007 Office of the General Prosecutor

Ecuador 18.1 4 2006

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Egypt 0.84 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

El Salvador 51.83 7 2008 Observatorio Centroamericano sobre Violencia

Equatorial Guinea 19.1 4 2004 WHO

Eritrea 16.1 3 2004 WHO

Estonia 6.26 2 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Ethiopia 20.47 4 2004 WHO

Fiji 2.8 1 2004 Interpol

Finland 2.49 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

France 1.35 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Gabon 16.24 4 2004 WHO

Gambia 14.31 3 2004 WHO

Georgia 7.57 2 2007

TransMONEE 2009 database, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre

Germany 0.8 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Ghana 1.75 1 2005 National Statistical Office

Greece 1.1 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Grenada 4.89 1 2004 WHO

Guam 0.58 1 2007 National Statistical Office

Guatemala 45.17 7 2006 Report of an international organization

Guinea 0.44 1 2007

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Guinea-Bissau 17.59 4 2004 WHO

Guyana 20.7 4 2008 National Statistical Office

Haiti 21.8 4 2004 Pan American Health Organization

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

of China 0.64 1 2004

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Hungary 1.47 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

India 2.77 1 2007 National Police

Indonesia 9.29 2 2004 WHO

Iran (Islamic Republic

of) 2.88 1 2004

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Iraq 7.31 2 2004 WHO

Ireland 1.95 1 2007 Eurostat

Israel 2.43 1 2008 National Statistical Office

Italy 1.16 1 2007 Eurostat

Jamaica 59.5 7 2008 National Police

Japan 0.45 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Jordan 1.74 1 2006

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Kazakhstan 10.56 2 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Kenya 3.65 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Kiribati 6.64 2 2004 WHO

Kuwait 1.38 1 2004 WHO

Kyrgyzstan 7.78 2 2007

TransMONEE 2009 database, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre

Lao People's Democratic

Republic 5.17 2 2004 WHO

Latvia 4.38 2 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Lebanon 0.56 1 2006

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Lesotho 36.69 6 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Liberia 17.43 4 2004 WHO

Libyan Arab Jamahiriya 2.95 1 2004 WHO

Liechtenstein 2.81 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Lithuania 8.61 2 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Luxembourg 1.46 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Madagascar 12.42 3 2004 WHO

Malawi 17.46 4 2004 WHO

Malaysia 2.31 1 2006

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Maldives 2.62 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Mali 17.56 4 2004 WHO

Malta 1.47 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Marshall Islands 1.8 1 2004 WHO

Mauritania 15.1 3 2004 WHO

Mauritius 3.75 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Mexico 11.59 3 2008 Non-Governmental Organization

Micronesia (Federated

States of) 0.92 1 2004 WHO

Mongolia 7.91 2 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Montenegro 3.7 2 2008 National Police

Morocco 0.4 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Mozambique 20 4 2004 WHO

Namibia 17.86 4 2004 Interpol

Nauru 9.91 2 2004 WHO

Nepal 2.24 1 2007 National Statistical Office

Netherlands 1 1 2007 Eurostat

New Zealand 1.25 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Nicaragua 12.97 3 2008 National Police

Niger 20.47 4 2004 WHO

Nigeria 1.29 1 2008 Non-Governmental Organization

Norway 0.64 1 2007 Eurostat

Occupied Palestinian

Territory 3.85 1 2005

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Oman 0.65 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Pakistan 6.81 2 2008 National Statistical Office

Panama 13.28 3 2007 Observatorio Centroamericano sobre Violencia

Papua New Guinea 15.1 3 2004 WHO

Paraguay 12.21 3 2007 National Statistical Office

Peru 3.21 1 2006 National Statistical Office

Philippines 6.44 2 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Poland 1.21 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Portugal 1.16 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Puerto Rico 20.35 4 2008 National Police

Qatar 1 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Republic of Korea 2.3 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Republic of Moldova 7.21 2 2008

Europen Health for All database - Homicide and intentional injury

Romania 2.47 1 2008

Europen Health for All database - Homicide and intentional injury

Russian Federation 14.18 3 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Rwanda 27.27 5 2004 WHO

Saint Kitts and Nevis 35.25 6 2008 National Police

Saint Lucia 16 3 2007 National Police

Saint Vincent and the

Grenadines 17.51 4 2004 WHO

Samoa 1.12 1 2004 WHO

Sao Tome and Principe 5.33 1 2004 WHO

Saudi Arabia 0.85 1 2007 National Statistical Office

Senegal 14.85 3 2004 WHO

Serbia 3.42 1 2008 National Statistical Office

Seychelles 8.44 2 2006

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Sierra Leone 2.63 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Singapore 0.39 1 2006

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Slovakia 1.74 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Slovenia 0.55 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Solomon Islands 1.52 1 2004 WHO

Somalia 3.25 1 2004 WHO

South Africa 36.54 6 2008 National Police

Spain 0.91 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Sri Lanka 7.42 2 2008 National Police

Sudan 27.23 5 2004 WHO

Suriname 13.66 3 2006

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Swaziland 21.1 4 2004 WHO

Sweden 0.89 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Switzerland 0.72 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Syrian Arab Republic 3 1 2007 National Statistical Office

Tajikistan 2.29 1 2007

TransMONEE 2009 database, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre

Thailand 5.9 2 2008 National Police

The former Yugoslav

Republic of Macedonia 2 1 2006

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Timor-Leste 12.52 3 2004 WHO

Togo 14.26 3 2004 WHO

Tonga 0.99 1 2004 WHO

Trinidad and Tobago 39.67 6 2008 National Police

Tunisia 1.68 1 2004 WHO

Turkey 2.94 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Turkmenistan 4.13 1 2006

TransMONEE 2009 database, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre

Uganda 8.7 2 2008 National Police

Ukraine 5.36 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

United Arab Emirates 0.92 1 2006

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

United Kingdom 1.57 1

2007 – 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems; Eurostat United Kingdom

(England and Wales) 1.19 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems United Kingdom

(Northern Ireland) 1.35 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems United Kingdom

United Republic of

Tanzania 25.8 5 2004 WHO

United States of America 5.22 1 2008

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Uruguay 5.78 1 2007 Ministry of Interior

Uzbekistan 3.24 1 2006

TransMONEE 2009 database, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre

Vanuatu 0.95 1 2004 WHO

Venezuela (Bolivarian

Republic of) 47.21 7 2008 Non-Governmental Organization

Viet Nam 1.85 1 2006

United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

Yemen 3.97 1 2008 National Statistical Office

Zambia 22.51 4 2004 WHO

Zimbabwe 34.29 6 2004 WHO

Appendix B. FDI raw and normalized data

Country FDI (2010) Normalized

Afghanistan 76 2

Albania 1,097 2

Algeria 2,291 2

Angola 9,942 3

Anguilla 25 2

Antigua and Barbuda 105 2

Argentina 6,337 3 Armenia 577 2 Aruba 161 2 Australia 32,472 5 Austria 6,613 3 Azerbaijan 563 2 Bahamas 977 2 Bahrain 156 2