Research and Politics October-December 2015: 1 –9 © The Author(s) 2015 DOI: 10.1177/2053168015612247 rap.sagepub.com

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC-BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

Introduction

Scholars and Members of Congress (MCs) alike have long assumed that money brought back to a district or state in the form of earmarked projects would garner appreciation from constituents. Several polls over a number of years have revealed that, in the aggregate, earmarks do not enjoy pop-ular support; in fact, they are deeply disdained. This raises a question: does pork behave similarly to notions of indi-vidual Member evaluation; that is, just as constituents love their Member but despise the institution of Congress, so too do constituents only cherish the projects that benefit them directly? While such a connection seems intuitive, it has never been verified empirically. This work attempts to shed light on this question by turning to experimental data to ascertain the impact of information regarding earmarks on Member support.

Voters must be able to successfully connect the actions of elected officials to specific attributable benefits, which requires “ both the knowledge and the beliefs of the voters” (Popkin, 1991: 96). Survey evidence tells us that citizens are remarkably uninformed about particularized spending.1 Nonetheless, many scholars have maintained, implicitly or explicitly, that earmarks breed appreciative constituents and safer elections (Alvarez and Saving, 1997; Bickers and Stein, 1996; Herron and Shotts, 2006; Jacobson, 2009; Stein and Bickers, 1994, 1995) That said, this conclusion is

not universally shared. For example, Sellers (1997) argues that electoral benefits from pork are conditional on Member–constituent ideological congruence, while Lee (2003) and Feldman and Jondrow (1984) contend the oppo-site: earmarked dollars do not lead to actualized electoral gains. While many researchers have relied on presupposed effects, none have attempted to directly ascertain the con-nection between pork and opinion. This work attempts to fill that gap by addressing a very basic question: given pork is disliked in the aggregate, can particularized benefits bol-ster Member support?

To be clear, this paper does not assert that earmarks influence electoral outcomes solely through direct aware-ness. To the contrary. Past studies have shown that ear-marks could also work by influencing special interest contributors (Rocca and Gordon, 2013), by scaring-off potential challengers (Bickers and Stein, 1996; Lazarus et al., 2012; Stein and Bickers, 1995), or through crediting claiming via the media as an intermediary (Grimmer et al.,

Desirable pork: do voters reward

for earmark acquisition?

Travis Braidwood

Abstract

The overwhelming majority of Congresspersons engage in the acquisition of pork projects, also known as earmarks. In the aggregate, the general public overwhelming opposes pork-barrel spending, yet scholars and Members of Congress both contend that earmarked projects make for grateful constituents. This work attempts to explain this discrepancy. Using experimental data, I show that general discussions of earmarks are not universally beneficial. Recipients are only moved when they are made aware of projects in policy arenas of individual importance. Thus, pork is a nuanced policy tool that must be wielded strategically to gain electoral reward from specific subsets of a constituency.

Keywords

Pork-Barrel, earmarks, Congress, experiment, framing, issue public

Texas A&M University— Kingsville, USA

Corresponding author:

Travis Braidwood, Texas A&M University— Kingsville, Department of History, Political Science, and Philosophy, MSC 165, 700 University Boulevard, Kingsville, TX 78363 USA.

Email: travis.braidwood@tamuk.edu

2012). That said, numerous scholars have asserted a direct connection between procured earmarks and member favorability (Arnold, 1990; Baron, 1990; Ferejohn, 1974; Jacobson, 2009; Mayhew, 1974; Shepsle and Weingast, 1981), while others have explored the possibility of pork bolstering awareness of the projects themselves (Stein and Bickers, 1994; 1995). Most recently, Grimmer et al. (2012) explored the role of press releases related to credit claiming for funding acquisition on MC support. Grimmer et al. found that when members credit claim through press releases they enjoy a boost in constituent support, but that this effect is conditioned on local media consumption. Grimmer et al. (2012) ultimately concluded that “ constitu-ents may have a limited response to large new expenditures in the district” (Grimmer et al., 2012: 717), but they do not attempt to determine the effect of framing or issue salience. Grimmer et al. (2012) are not alone; despite a recent rise in the number of articles on earmarks, no work exists estab-lishing how presentation of localized projects affects con-stituent appreciation of such efforts. This work investigates the consequences of bringing federal dollars home for those who are made aware.

The notion that individual projects could garner elec-toral support also finds a home in the economic voting lit-erature. This theory, which dates back to The American Voter (Campbell et al., 1960), has been the subject of numerous observational (e.g. Bechtel and Hainmueller, 2011; Gomez and Wilson, 2001; 2003; Grafstein, 2009; Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, 2000; Lewis-Beck, 1985; Romero and Stambough, 1996) and experimental studies (e.g. Sigelman et al., 1991; Sirin and Villalobos, 2011); in fact, Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier (2007) point out that there have been over 400 published works on the subject. In the present context is the idea that voters engage in pocketbook voting by basing their assessment of candidates on “their personal economic well being” (Gomez and Wilson, 2001: 899). For earmarks this would correspond to MC efforts to procure benefits that directly improve the economic condi-tions of those they represent. Following the public disclo-sure of earmark requests several years ago, scholars were quick to find numerous examples of these direct outlays: projects to improve roadways, direct grants to private busi-nesses, workplace training programs, etc. While the inves-tigations of pocketbook voting have sometimes met with mixed results, it is plainly apparent that pork may serve as yet another opportunity for voters to evaluate their MCs though the lens of personal economic assistance.

Issue publics

Citizens are not uniformly concerned about political issues. The notion that citizens follow certain issues with varying intensity based on individual preferences is an idea stretch-ing back to Converse’s (1964) coinstretch-ing of the term “ issue

public.” Generally speaking, politics is a secondary concern for most citizens. Given time and resource constraints, it is not surprising that most tend to direct their attention primar-ily to issues of personal importance (Krosnick, 1990).

Earmarks are not confined to a specific policy, they expand over various issue areas (Lazarus, 2009). This gives Members the opportunity to make direct appeals to a wide array of issue publics. Rocca and Gordon (2013) found in their exploration of defense earmarks, district factors (vet-erans in the district) and Member characteristics (Defense Subcommittee membership, Armed Services Subcommittee membership, and Military Constriction Subcommittee membership) were both significant predictors of defense earmark acquisition. Lazarus (2010) confirmed that this connection spans across a large array of issue areas. Consequently, investigations regarding the utility of ear-marks should not assume all projects are viewed equally in the eyes of recipients. Rather, we should expect that con-stituent preferences vary according to their issue public(s), with greater attentiveness to issues of personal concern.

Hypotheses

The congressional literature suggests that those in recipient districts or states should reward the member responsible for bringing home the bacon, yet this long-held assumption has never been directly verified. Armed with the underlying theories detailed above, it is possible to derive a series of hypotheses to test this assumption. First, if extant literature is correct, then (H1) general information about earmarked dollars being secured for local benefit will increase favora-ble evaluations of the responsifavora-ble member of Congress, ceteris paribus. Second, numerous studies have empha-sized the importance of specific issues for members of cor-responding issue publics, therefore (H2) particularized information about earmarked dollars that are personally relevant and secured for local benefit will increase evalua-tions of the responsible member of Congress, ceteris pari-bus. Finally, given that membership to an issue public means increased attentiveness and position strength, (H3) the effect of particularized information about earmarks that are personally relevant will be greater than the effect of general information about earmarks.

Experimental design

Two experiments were conducted: an initial test of the hypotheses and a robustness check.

Experiment 1

For the first experiment, subjects were recruited using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to take part in a “ political sur-vey” in exchange for compensation.2 The subject pool was limited to Florida residents to ensure a direct connection between the MC and the recipients, and to ease coding.3

Subjects were randomly divided into five groups: a Senator Bill Nelson general treatment condition; a Senator Marco Rubio general treatment condition; a Senator Nelson education treatment condition; a Senator Rubio military treatment condition; or a control condition. The general conditions featured a vignette with the following language: “ [t]axpayers for Common Sense compiles a yearly list of earmarks (also known as pork projects) obtained by MCs. According to them, [Sen. Bill Nelson (FL)/Sen. Marco Rubio (FL)] secured over [$650 million/$110 million] in projects.” The Sen. Nelson education condition pool was given the same language, as well an additional sentence: “ [a]lmost $1 million of the money he brought home to Florida directly funded programs at colleges and universi-ties.” The Sen. Rubio military condition was given the gen-eral condition language, which was followed by “[a] sizable amount of the money he brought home to Florida directly funded military defense programs and projects.” Finally, the control condition was given no text.

Following the vignettes, all subjects were asked two evaluative questions about Senators Nelson or Rubio: two 7-point questions regarding favorability and job approval, which were combined into a single measure.4 To ascertain whether an issue is personally relevant (hypothesis 3), all subjects were asked four follow-up questions: “ [a]re you currently enrolled in a college or university,” “[a]re you or a member of your immediate family a member of the armed forces,” “[h]ow important is the issue of higher education to you personally,” and “[h]ow important is the issue of national defense to you personally?” The first pair of ques-tions were measured as a simple binary yes or no; the sec-ond pair were measured on 5-point Likert scales ranging from “not at all important” to “extremely important,” which were collapsed into a binary variable indicating support.5 Not surprisingly, the college enrollment and higher educa-tion measures are highly correlated (0.861, p < 0.001), and the military affiliation and defense measures were moder-ately correlated (0.567, p < 0.001).

Experiment 1 results

The results of the first experiment are displayed in Table 1 as an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression where the

dependent variable is average of the two evaluative ques-tions mentioned above.6 The findings suggest a rejection of the first hypothesis: general information about earmarks does not appear to be enough to bolster MC support for either Senator. That said, the results do support hypotheses two and three: members of issue publics are especially receptive to positive information about earmarks, and this effect is greater in the particularized context compared to the general information context.

Beginning with Senator Nelson, those that received the education treatment and that self-identified as being cur-rently enrolled in college (column 1) saw a 1.173 (p < 0.01) point increase in support for Senator Nelson, ceteris pari-bus.7 However, for those who received the education treat-ment that were not enrolled in college or university, there was no significant change in support for the Senator. The table below also considers the education treatment’s effect on those that identified higher education as highly impor-tant (column 2). Those identifying higher education as an important issue area that were exposed to the education vignette had an even greater boost in support for the Senator: a 1.286 (p < 0.01) point gain, ceteris paribus.

Turning to Senator Rubio (columns 3 and 4), we see even stronger results. For those that were affiliated with the military and who received the military treatment, we saw a whopping 2.46 (p < 0.05) point increase in support, ceteris paribus. Unlike Nelson, however, this result was still par-tially felt for all respondents affiliated with the armed forces absent the military treatment. For those concerned with national defense in the military treatment, we saw a 2.04 (p < 0.001) point increase in support, ceteris paribus. Like the Nelson treatments, for those that did not identify national defense as an issue of major importance, this effect was not present.

Hypothesis 3 proposed that members of issue publics are more supportive of MCs that bring back pork dollars compared with those receiving general information about outlays. This hypothesis found strong support. For Sen. Nelson, the effect of the treatment for those in college is notably greater than those in the general condition (F(1,154) = 5.60, p < 0.05), as is the effect for those iden-tifying higher education spending as an important issue (F(1, 155) = 7.21, p < 0.01). Similar results were found for Sen. Rubio: for those with a military affiliation (F(1, 156) = 46.32, p < 0.001), and in the national defense spending grouping (F(1, 156) = 23.45, p < 0.001).

being enrolled in college (the second and third bar, top fig-ure), and those responding that they or an immediate family member are in the armed forces (the second and third bar, bottom figure). The three rightmost bars show the same results while differentiating between those who identified higher education (Sen. Nelson, top figure) or national defense (Sen. Rubio, bottom figure) as an important issue. We see that exposure to the general treatment did not affect assessment of Senators Nelson or Rubio in a statistically significant way. However, for those in college, those view-ing higher education as an important issue, those affiliated with the military, and those stating national defense is per-sonally important had higher levels of support following exposure to the corresponding earmark frame.

Robustness check: congressional chamber

Questions may be raised regarding the certainty and validity of the previous findings. This section tests for robustness, replicability, and applicability of the findings to members of the US House. This was achieved with an experiment con-ducted using Florida State University students; subjects

were asked to evaluate Representative Jeff Miller (R, FL-1st) over a pair of issues areas.

This robustness check explores the same issue areas as the first experiment: higher education (by assuming the college student sample are concerned with higher education spend-ing, and therefore members of that issue public), and military spending. Membership to the latter issue public was deter-mined by asking survey respondents “ [a]re you or a member of your immediate family actively serving in the military?”

The treatment vignettes resemble those from the previ-ous experiment. Subjects randomly assigned into the gen-eral frame were told that “[l]ast fiscal year US Representative Jeff Miller for Florida’s 1st District secured $21.5 million in earmarks (also known as pork projects) for his district.” Those in the particularized education frame received the same information with the addition of the following sen-tence: “[a] sizable amount of the money he brought home to Florida directly funded programs at institutions of higher learning.” Finally, those in the particularized military frame received the general treatment language with the following sentence added: “[a] sizable amount of the money he brought home to Florida directly funded military defense Table 1. The effect of pork treatments on support for Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL) and Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL), MTurk.

Senator Nelson (D-FL) Senator Rubio (R-FL)

College Students Higher Educ. Mil. Affiliation Nat’l Defense

General Treatment 0.178 0.149 −0.065 −0.145

(0.263) (0.261) (0.290) (0.297)

Education Treatment −0.034 −0.112

(0.280) (0.277)

College Enrolled 0.089

(0.346)

College × Educ. Treatment 1.089*

(0.537)

Higher Educ. Important −0.096

(0.408)

Higher Educ. × Educ. Treat. 1.466*

(0.584)

Military Treatment 0.134 −0.825

(0.424) (0.601)

Military Affiliation 1.119***

(0.294)

Mil. Treat × Mil. Affiliation 1.202*

(0.511)

National Def. Important 0.704

(0.398)

Mil. Treat x National Def. 2.152**

(0.643)

Constant 4.034*** 4.088*** 3.093*** 3.200***

(0.190) (0.190) (0.279) (0.405)

R2 0.057 0.069 0.271 0.232

N 159 160 161 161

programs and projects.” Once again, the control group was given no vignette. All respondents were then asked the same pair of evaluation questions from the first study to access views about Rep. Miller’s favorability and job

approval. These two responses were combined to form an overall evaluation measure.8

value of the projects brought home have changed to reflect the money Miller actually returned to his district.

Those in the General treatment category are, again, expected to have a more favorable opinion of the member as compared with the control group (hypothesis one), as are those in the Education treatment (college students made aware of spending for higher education), and those with military affiliation in the Military treatment (hypothesis 2). In addition, information about particularized benefits (i.e. the Military and Education treatments) for subjects belong-ing to those issue publics will have higher evaluations of the MC as compared with those in the General treatment condition (hypothesis 3).9

Results, robustness check

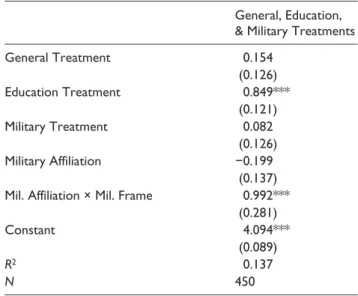

Table 2 reveals results akin to the first experiment. Again, contrary to the first hypothesis, simply telling respond-ents about earmarks did not affect support for the respon-sible member in a statistically significant way. However, when the college student respondents learned of earmarks going to institutions of higher learning, we saw a corre-sponding increase of almost a full point in support (0.85, p < 0.001), c e t e r i s p a r i b u s, confirming the second hypothesis. Like the first experiment, for those not asso-ciated with the military, the military treatment had no sta-tistically significant effect (0.082, p = 0.513); however, for subjects who received the military-pork treatment and who were associated with the military (i.e. Military Affiliation × Military Frame), there was a sizable increase in support equal to almost one point (0.885, p < 0.001), c e t e r i s p a r i b u s .10 In other words, members of the issue public were extremely appreciative of MC efforts, but those not in the issue public showed no significant change in opinion.

Finally, when taken together, the education and military frames confirm the third hypothesis: allocations to issue areas seen as personally beneficial result in larger increases in support than generalized allocations. The education frame and military frame are comparable in size, and both are notably larger and statistically different from the general frame, which an F-test confirms for the education frame (F(1, 431) = 30.51, p < 0.001), and the military frame (for those in the military) (F(1, 444) = 8.49, p < 0.01).

Figure 2 displays the results of Table 2 visually. Like the first experiment, members of an issue public made aware of MC efforts were indeed appreciative, but those without this affiliation (third bar) remained unmoved.

The robustness check confirms that making recipients aware of earmarks results in favorability gains for the responsible MC, so long as the recipient is a member of the issue public affected by the earmarks. Moreover, these results appear to hold for Republicans as well as Democrats, for House members and Senators, and over varied issue publics.

Additional robustness checks. The issue of random

assign-ment is worth a brief assign-mention. The on-line suppleassign-mental featured on the author’s website (http://bit.ly/Desirable-Pork) features numerous models that regress a number of demographic control variables on the treatment and control conditions. The results provide strong support that the sub-jects were successfully assigned to a condition randomly.

Finally, a word on party identification. The earmarks lit-erature has seen a growing body of evidence that has found that earmark allocations are not equally sought by both par-ties (Lazarus et al., 2012; Lazarus and Reilly, 2010; Levitt and Snyder, 1995; Sellers, 1997). While others have found that both parties seek earmarks to avoid being the sole tar-get of blame (Balla et al., 2002). At the individual level it is unclear whether recipients condition their appreciation on the party of the MC securing the earmarked dollars. A robustness check was conducted on all of the presented models where respondent party identification was inter-acted with the treatment conditions, however, there was no statistically significant relationship found (these results are available on-line). This may suggest the gains in support are conditioned by the issue area benefited by projects rather than the party relationship between recipient and MC. Also, it should be noted that the member’s party was not explicit in the vignettes. Further research is needed to explore this possible relationship.

Conclusion

This work explored a long held assumption surrounding federal outlays; namely, that earmarks brought home to a state or district will invariably win the favor of appreciative Table 2. The effect of pork treatments on support for Rep. Miller (R, FL-1st).

General, Education, & Military Treatments

General Treatment 0.154

(0.126)

Education Treatment 0.849***

(0.121)

Military Treatment 0.082

(0.126)

Military Affiliation −0.199

(0.137)

Mil. Affiliation × Mil. Frame 0.992***

(0.281)

Constant 4.094***

(0.089)

R2 0.137

N 450

recipients. A number of scholars have implied or directly stated that pork serves as a robust tool available to incum-bents to reduce electoral uncertainty (see Jacobson, 2009; Popkin, 1991; Sellers, 1997; Stein and Bickers, 1994, 1995: for prominent examples). This conclusion has long been asserted in spite of the overwhelming aggregate disap-proval of earmarks. These suppositions are based on tradi-tional notions of representation: voters may despise the institution as whole, but they appreciate their MC. While this makes intuitive sense, such proposals have not been subjected to empirical testing. By relying on a series of experiments, this work confirms that earmarks may aid candidates, but that such gains are conditioned on the rele-vance of the projects to the recipients.

Ultimately the experiments presented above recast con-ventional views of earmarks as a universally positive ben-efit for MCs wishing to bolster electoral security. Rather, the ability of a MC to successfully sell earmarks to their constituents, like most political issues, is heavily depend-ent on the framing of the issue and the target audience. Basic factual information describing the amount of money brought home was not enough to significantly affect a change in opinion. However, when these monies were per-sonally relevant, MCs gained significantly for their efforts.

MCs looking to win appreciation should not assume that more is always better. Skilled politicians must identify which policy arenas are of particular importance to their constituents, work to secure projects in those policy realms, and ensure prominent media coverage of those efforts to enlighten the beneficiaries.11 Scholars have recently begun to pick-up on this nuance; for example, Grimmer et al. (2012: 714-717) revealed the benefit of credit claiming pork projects. Namely, that while “ the amount of money claimed in press releases fails to sub-stantively or significantly increase […] evaluations,” that MCs with a “ propensity to credit claim also tend to receiver higher levels of support” conditional on local media consumption. Therefore, appeals to issue publics are in the MC’s best interest to reap support from pork.

effect on recipients. Future work should seek to use experi-ments and media studies to ascertain the ability of MCs to utilize pork to garner support.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Scott Clifford, Jennifer Jerit, and Cherie Maestas for their assistance in this work.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Notes

1. For example, the 2008 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) found that when respondents were asked whether they could “recall any specific projects that your members of Congress brought back to your area,” only 17% answered in the affirmative.

2. Subjects were paid US$0.25 for completing the survey. A total of 161 subjects completed the survey successfully. Demographically, the sample looks surprising diverse despite the small size. The sample was 48% male, 67% White, slightly more affiliated with Democrats (4.7 on a 7-point scale), and having an average of 3 years of college education.

3. While geographically limited to one state (Florida), there is no reason to suspect the results would not hold for any other US state.

4. The language of the questions was “[h]ow would you describe your views towards Senator [Bill Nelson/Marco Rubio],” and “[h]ow strongly do approve of disapprove of the job Senator [Bill Nelson/Marco Rubio] is doing?” The measures are strongly correlated for both Sen. Nelson (r= 0.876, p < 0.001) and Sen. Rubio ( = 0.875r , p < 0.001). Cronbach’s a confirms the unidimensional nature of the combined meas-ure: α= 0.933 for Sen. Nelson and α= 0.924 for Sen. Rubio. Disaggregated results are substantively the same, and are available in the supporting on-line material at the author’s website: http://bit.ly/DesirablePork.

5. This was achieved by recoding the “very” and “extremely important” responses as 1, and others as 0. This was also con-sidered by collapsing values 3–5 as 1, and others as 0. The results are very similar; the alternative measure is available at the author’s website: http://bit.ly/DesirablePork.

6. This and all subsequent models were also estimated via order probit (available at the author’s website: http://bit.ly/ DesirablePork); the results remain substantive unchanged. OLS estimates are provided in the main text for three rea-sons: simplicity of interpretation, it does not impose the parallel regression assumption, and as the number of ranked categories increase (here the dependent variable assumed 13 possible values), the data take on the form of a continuous variable Long, (1997).

7. These predicted changes include the interaction effect. The predicted change was calculated using Tomz et al.'s (2003) CLARIFY software.

8. Like the first study, these two questions were both meas-ured on 7-point Likert scales. These measures are cor-related (r= 0.64, p < 0.001) and Cronbach’s a again confirms the unidimensional nature of the combined meas-ure: α= 0.757. Disaggregated results are substantively the same, and are available at the author’s website: http://bit.ly/ DesirablePork.

9. There are no a priori expectations regarding the size of the effect of the Education treatment as compared to the Military treatment.

10. This number is lower than the 0.992 reported in the table because of the interaction effect between military treatment and military affiliation.

11. Casual analysis suggests that many MCs do indeed pur-sue this goal. For example, Adam Smith (WA-9th) repre-sents a Washington district with numerous environmental and farming interests. He single-handedly worked to secure US$24.1 million in earmarks for projects related to environmental quality, and features these efforts prominently on his website (http://adamsmith.house.gov/ fiscalappropriations/).

References

Alvarez M and Saving JL (1997) Deficits, democrats, and dis-tributive benefits: Congressional elections and the pork barrel in the 1980s. Political Research Quarterly 50: 809–831.

Arnold D (1990) The Logic of Congressional Action. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Balla SJ, Lawrence ED, Maltzman F and Sigelman L (2002) Partisanship, blame avoidance, and the distribution of leg-islative pork. American Journal of Political Science 46: 515–525.

Baron DP (1990) Distributive politics and the persistence of Amtrak. The Journal of Politics 52: 883–913.

Bechtel M and Hainmueller J (2011) How lasting is voter grati-tude? An analysis of the short-and long-term electoral returns to beneficial policy. American Journal of Political Science 55: 852–868.

Bickers KN and Stein RM (1996) The electoral dynamics of the federal pork barrel. American Journal of Political Science 40: 1300–1326.

Campbell A, Converse PE, Miller WE and Stokes DE (1960) The American Voter. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Converse PE (1964) The nature of belief systems in mass publics.

In: Ideology and Discontent. New York: The Free Press, pp. 206–261.

Feldman P and Jondrow J (1984) Congressional elections and local federal spending. American Journal of Political Science 28: 147–64.

Ferejohn JA (1974) Pork Barrel Politics: Rivers and Harbors Legislation, 1947–1968. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Gomez BT and Wilson JM (2001) Political sophistication and economic voting in the American electorate: A theory of heterogeneous attribution. American Journal of Political Science 45: 899–914.

Grafstein R (2009) The puzzle of weak pocketbook voting. Journal of Theoretical Politics 21: 451–482.

Grimmer J, Messing S and Westwood SJ (2012) How words and money cultivate a personal vote: The effect of legislator credit claiming on constituent credit allocation. American Political Science Review 106: 703–719.

Herron M and Shotts K (2006) Term limits and pork. Legislative Studies Quarterly 31: 383–403.

Jacobson GC (2009) The Politics of Congressional Elections, 7th edn. London: Person Education, Inc.

Krosnick JA (1990) Government policy and citizen passion: A study of issue publics in contemporary America. Political Behavior 12: 59–92.

Lazarus J (2009) Party, electoral vulnerability, and earmarks in the U.S. House of Representatives. Journal of Politics 71: 1050–1061.

Lazarus J (2010) Giving the people what they want? The distri-bution of earmarks in the U.S. House of Representatives. American Journal of Political Science 54: 338–353.

Lazarus J, Glas J and Barbieri KT (2012) Earmarks and elec-tions to the U.S. House of Representatives. Congress and the Presidency 39: 254–269.

Lazarus J and Reilly S (2010) The electoral benefits of destributive spending. Political Research Quarterly 63: 343–355.

Lee F (2003) Geographic politics in the U.S. House of repre-sentatives: Coalition building and distribution of benefits. American Journal of Political Science 47: 714–728.

Levitt S and Snyder JJ (1995) Political parties and the distribution of federal outlays. American Journal of Political Science 39: 958–680.

Lewis-Beck M and Stegmaier M (2000) Economic determinants of electoral outcomes. Annual Review of Political Science 3: 183–219.

Lewis-Beck MS (1985) Pocketbook voting in US national elec-tion studies: Fact or artifact? American Journal of Political Science 29: 348–356.

Lewis-Beck MS and Stegmaier M (2007) Economic models of voting. In: The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 518–537.

Long S (1997) Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables. London: Sage Publications.

Mayhew DR (1974) Congress: The Electoral Connection. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Popkin SL (1991) The Reasoning Voter: Communication and Persuasion in Presidential Campaigns. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Rocca MS and Gordon SB (2013) Earmarks as a means and an end: The link between earmarks and campaign contributions in the U.S. House of Representatives. The Journal of Politics 75: 241–253.

Romero DW and Stambough SJ (1996) Personal economic well-being and the individual vote for congress: A pooled analy-sis, 1980–1990. Political Research Quarterly 49: 607–616. Sellers P (1997) Fiscal consistency and federal district spending

in congressional elections. American Journal of Political Science 41: 1024–1041.

Shepsle KA and Weingast BR (1981) Political preferences for the pork barrel: A generalization. American Journal of Political Science 25: 96–111.

Sigelman L, Sigelman CK and Bullock D (1991) Reconsidering pocketbook voting: An experimental approach. Political Behavior 13: 129–149.

Sirin CV and Villalobos JD (2011) Where does the buck stop? Applying attribution theory to examine public appraisals of the president. Presidential Studies Quarterly 41: 334–357. Stein RM and Bickers KN (1994) Congressional elections and the

pork barrel. The Journal of Politics 56: 377–399.

Stein RM and Bickers KN (1995) Perpetuating the Pork Barrel: Policy Subsystems in American Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.